Abstract

The stress state changes in shallow gassy sand strata under anthropogenic disturbances can be simplified as failure problems of gassy sand under constant shear stress drained (or undrained) stress paths. However, related research remains relatively limited. To investigate the mechanical properties of gassy sand, this study utilized a high-pressure gas dissolution saturator and employed a CO2-saturated aqueous solution degassing method to prepare high-saturation gassy sand specimens. A series of triaxial tests under constant shear stress paths were conducted under both drained and undrained conditions, focusing on the effects of relative density, saturation, and deviatoric stress levels in constant shear stress paths. The effective stress paths and instability time-response patterns of gassy sand under constant external loads with internal stress variations were obtained. Experimental results revealed that in the p′−q plane, for loose or dense gassy sand with varying saturations, the stress path entry points into an unstable state consistently lie within the potential instability zone bounded by the critical state line (CSL) and instability line (IL). In constant shear stress drained (CSD) tests, lower sand saturation corresponds to longer times to reach instability, whereas the opposite trend was observed in constant shear stress undrained (CSU) tests. These findings enhance the understanding of the mechanical behavior of gassy sand and provide theoretical support for safety assessments in engineering projects involving shallow gassy strata.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Submarine sediments containing shallow gas, referred to as gassy soils1, represent a special type of soil characterized by a metastable equilibrium system composed of soil particles, pore water, gas, temperature, and overburden pressure. Gassy soils, a subset of unsaturated soils with high saturation degrees (Sr > 85%)2,3, feature gas bubbles trapped within pore spaces without disrupting the soil skeleton. Finno et al.4 validated the applicability of Terzaghi’s effective stress principle to gassy sands through undrained triaxial shear tests on specimens with saturations of 92–100%. Previous studies have demonstrated that stress-strain behavior and pore pressure responses vary significantly with material types and compaction states5,6. Under unloading stress paths, pore pressure in gassy soils decreases slowly due to gas exsolution and expansion during total stress reduction, a phenomenon distinct from saturated or conventional unsaturated soils7.

The metastable structure of gassy soils is highly sensitive to temperature, pressure, or environmental disturbances, which may trigger gas exsolution, rapid expansion, and subsequent engineering property degradation, posing risks to infrastructure8,9,10,11,12. Human activities, such as pile foundation installation or tunnel construction, can destabilize biogenic gas in gassy sand layers, leading to abrupt pore pressure increases, sharp reductions in effective stress, and soil failure. In practice, the stress state evolution in gassy sand strata across these scenarios can be abstracted as failure problems under constant shear stress paths (drained/undrained): ① Marine slope progressive failure: Slow shear deformation in submarine gassy strata under gravitational stress (e.g., persistent shear strength degradation due to natural gas seepage). ② Energy extraction-induced subsidence: Stress redistribution in soil skeletons from pore pressure changes during oil/gas extraction (e.g., shear stiffness degradation in North Sea gassy silty sand during gas production). ③ Hydrate dissociation submarine landslides: Catastrophic conditions with sustained pore water pressure rise under near-constant shear loading during methane hydrate dissociation (e.g., slope failure mechanisms in Shenhu Area, South China Sea). ④ Pile foundation cyclic deformation accumulation: Cyclic shear stress with near-constant amplitude but reduced effective confining pressure in saturated-gassy transition zones under wave loading on offshore wind turbine foundations.

Researchers worldwide have investigated marine gassy soils, focusing on sample preparation and mechanical behavior. For in-situ sampling, Denk13 developed a double-tube pressure-preserved sampler, though its complexity and cost limit widespread adoption. Consequently, laboratory preparation methods, including physical, chemical, and biological approaches, have been explored. Physical methods include CO2 solution displacement7,14,15capsule-mixed slurry16and gas injection17. Chemical approaches involve electrolysis18 and sodium perborate decomposition19while biological methods utilize denitrification to generate nitrogen bubbles6,20 or organic matter oxidation21. Despite progress, challenges remain in ensuring sample homogeneity and reproducibility, necessitating further development of eco-friendly, scalable preparation techniques.

Mechanical responses of gassy soils under constant shear stress paths have drawn increasing attention. Minor sea-level fluctuations may destabilize submarine slopes, analogous to failures of hydrate-dissociated gassy soils under constant shear stress paths22,23. Kong et al.24 observed that dense gassy sands under constant shear stress exhibit uniform instability lines across confining pressures, resembling saturated loose sands. Saturation minimally influenced instability patterns, though failure modes diverged: drained conditions led to sudden liquefaction, while undrained conditions produced progressive shear banding. Vega-Posada et al.25 highlighted the pronounced impact of drainage on medium-dense gassy sands, noting increased compressibility and suppressed pore pressure generation compared to fully saturated sands. Amaratunga et al.26 reported gas exsolution during undrained unloading, causing rapid effective stress reduction and instability. He et al.27 found that reducing saturation from 100–88%–95% tripled the undrained shear strength of loose sands and altered strain behavior from softening to hardening. Hong et al.28 demonstrated that gas bubbles reduce the undrained strength of dense sands but inhibit liquefaction in loose sands, governed by dilatancy or contraction states. While stability analyses for saturated sands are well-established23,29,30,31criteria for gassy sands remain understudied.

Current research on gassy sands faces significant limitations: Some studies inappropriately apply unsaturated soil theory to conclude that strength increases with decreasing saturation—an oversimplification lacking rigor. Challenges in specimen preparation and scarcity of experimental data, particularly under constant shear stress paths (e.g., during pore-fluid pressure buildup post-subsea hydrate dissociation), impede deeper understanding. Given the complex occurrence states of gassy sand and the difficulty in obtaining undisturbed samples, this study employs an enhanced laboratory method to simulate gassy sand. The true shear behavior of gassy sand in engineering contexts was captured through drained/undrained constant shear stress path triaxial tests on reconstituted specimens with varying saturations. By systematically examining effective stress paths and instability timing characteristics, this work seeks to bridge research gaps and provide theoretical underpinnings for engineering safety assessments in shallow gas-bearing strata.

Materials and methods

Sand specimens and gassy sand Preparation

The sand specimens were collected from a gas-rich shallow layer in the Nansha–Zhuhai (Zhongshan) Metro Project (Wanqingsha–Xingzhong Section) in Guangzhou. The tested sand exhibits a specific gravity Gs=2.69, minimum void ratio emin=0.51, and maximum void ratio emax=0.88, The particle size distribution falls primarily within the range of 2 mm to 0.00974 mm, accounting for over 86.3% of the total mass. The silt fraction constitutes approximately 7.6% of the mass. The average particle diameter (d₅₀) is 0.208 mm, the coefficient of uniformity (Cu) is 18.87, and the coefficient of curvature (Cc) is 2.54 (ASTM D4254-16, 2016; ASTM D4253-16e1, 2019)32,33. The particle size distribution curve is shown in Fig. 1 (ASTM D6913/D6913M-17, 2021)34.

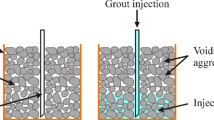

High-saturation gassy sand specimens were prepared using a CO2-saturated water exsolution method facilitated by a high-pressure gas dissolution saturation apparatus developed by the Wuhan Institute of Rock and Soil Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. This method eliminates constraints from external pressure conditions. The apparatus (Fig. 2) generates saturated CO2 solutions under high pressure, which are then injected into specimens to replace pore water. Experiments were conducted at a constant temperature of 25 °C, with CO2 as the solute and deaerated water as the solvent. The prepared solution was connected to a GDS stress-path triaxial system via multi-diameter pipelines and fittings for pore fluid replacement. The detailed specimen preparation procedure is as follows:

Step 1. Mount the sand specimen in the triaxial apparatus. Sample preparation employed the moist-tamping method. Saturate the specimen using de-aired water to ensure pore fluid homogeneity.

Step 2. Prepare a CO2-saturated aqueous solution to displace the pore water in the saturated specimen. Continuously circulate the CO2-saturated solution for 2–3 h until the cumulative replacement volume exceeds 5 times the specimen’s volume, ensuring complete pore water substitution.

Step 3. Disconnect the circulation system and close the backpressure valve. Initiate stepwise undrained unloading to induce dissolved gas exsolution. Gradually reduce the cell pressure in increments, with each step ≤ 50 kPa. During each pressure hold period, continuously monitor and document pore pressure responses.

Step 4. Characterize specimen state parameters. During the unloading/exsolution process: (a) Deploy bender elements to transmit/receive shear waves (S-waves) for real-time tracking of gas exsolution progress and fabric changes. (b) Deploy bender elements to transmit/receive compressional waves (P-waves) for complementary assessment.

Step 5. Perform measurements to verify gassy sand specimen integrity. If Vs remains consistent with its pre-exsolution consolidation value (deviation ≤ 5%), then the specimen is deemed intact. Proceed to step 6. If not, return to Step 1 to re-prepare the specimen.

Step 6. Conduct stress path tests on the verified gassy sand specimen under controlled triaxial conditions.

Figure 3 illustrates the preparation workflow, and the homogeneity of specimens produced by this method has been validated by Wang et al.35,36. During the undrained unloading process, bubble expansion and gas exsolution induce changes in specimen saturation and porosity, resulting in volumetric expansion. The prevailing saturation after each unloading step can be calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2)35,36.

Where Vi is initial total volume of specimen prior to unloading; ∆Vij is total volumetric change within current unloading step (positive for expansion); ∆Pij is change in gas absolute pressure; Pj is terminal pore water pressure upon completion of unloading step; H′ is Henry’s volumetric solubility coefficient; Si, Sj are degree of saturation (%) before/after unloading, respectively; ni is initial porosity prior to unloading. These calculation formulations adopt the following assumptions: CO2 dissolution in water complies with Henry’s law, bubble pressure equilibrates with pore water pressure, and surface tension effects are negligible.

Experimental program

The experiments comprised two parts: ① Conventional Consolidated Undrained (CU) Triaxial Shear Tests. Designed to analyze critical state lines and basic mechanical parameters of gassy sand under varying confining pressures, compaction states, and saturation degrees (Table 1). ② Constant Shear Stress Path Triaxial Tests. Conducted under different compaction states, drainage conditions, stress ratios, and gas contents (Table 2). All specimens (50 × 100 mm) were consolidated at 200 kPa with a back pressure of 500 kPa.

Testing procedures

Conventional consolidated undrained (CU) triaxial shear tests

The drainage condition was set using the manual loading module, with confining pressure, pore pressure and shear rate adjusted according to drainage requirements. For undrained conditions: setting confining pressure to the current target value, 500 kPa is selected as the back pressure, configure axial displacement in linear loading mode with a target value of 25 mm, applying the CU shear rate at 0.05 mm/min.

Constant shear stress drained (CSD) tests

First, conduct conventional consolidated drained shear until the deviator stress reaches the specified value. Then maintain this deviator stress constant to initiate the constant shear phase. During the constant shear phase, the confining pressure (σ₃) is held constant via the pressure controller. The pore pressure (u) is increased at a rate of 3 kPa/min using the back pressure controller. The deviator stress (q) is maintained constant by the axial pressure controller. Select the advanced loading module with stable confining pressure and shear stress settings, linearly increasing back pressure. The major principal stress (σ₁) is calculated using Eq. (3).

where η’ is the effective stress ratio at target q, η’=q/p’.

Constant shear stress undrained (CSU) tests

Based on Eq. (3), calculate the σ₁ value when reaching the specified deviator stress magnitude. When the deviator stress in the consolidated undrained shear reaches the specified magnitude, maintain the axial pressure σ₁ as a constant value and initiate the constant shear phase. During the constant shear phase, keep the back pressure volume constant, simultaneously reduce both the confining pressure σ₃ and axial pressure σ₁. Select the advanced loading module and close the back pressure valve. Setting both confining pressure σ₃ and axial pressure σ₁ to linear decreasing mode with reduction rate at 3 kPa/min.

Effective stress paths in CSD tests and CU tests

Figure 4 presents effective stress paths for loose sand (Dr=29.8%) under CSD tests with constant shear stresses of 70 kPa, 120 kPa, and 180 kPa, alongside CU test results. Three saturation degrees (100%, 95.3%, and 85.4%) were evaluated.

According to the definition of the Instability Line (IL), connecting the peak points of consolidated undrained (CU) effective stress path curves of loose sand under different degrees of saturation yields the Instability Line (IL) for loose sand. The region bounded by the sand’s Instability Line (IL) and Critical State Line (CSL) (shaded area in Fig. 5) constitutes the Potential Instability Zone of the sand37,38,39,40,41,42. The effective stress path curves from these tests show a key observation: Within the high saturation range studied, the degree of saturation has little effect on the sand’s Critical State Line (CSL) slope. The CSL slope (MCSLMCSL) remains constant at 1.573. This indicates that the presence of gas bubbles affects the peak shear strength, but once the critical shear state is reached, the presence of gas has negligible impact on the q/p′ value. By comparing Fig. 4(a), (b), and (c), it is evident that even a small amount of gas significantly influences the stress ratio at which loose sand specimens reach instability. Specifically, as the degree of saturation decreases (from 100%, 95.3–85.4%), the corresponding instability stress ratios for gas-containing loose sand increase progressively to 1.066, 1.212, and 1.401, respectively. Additionally, the effective stress paths from constant shear drained (CSD) tests on loose sand reveal that the derived instability lines consistently fall within the Potential Instability Zone and are predominantly positioned near the Instability Line (IL) under loose sand conditions. Daouadji et al.22 demonstrated that saturated loose sand specimens under different confining pressures and stress ratios share identical instability lines under constant shear stress paths. This study further confirms that: For loose sand with identical density and saturation, the effective instability stress ratio remains the same across different shear stress levels. For loose sand with identical density but varying degrees of saturation, the effective instability stress ratio increases progressively as saturation decreases.

Figure 5 illustrates the effective stress paths of dense sand (Dr=89.5%) under constant shear consolidated drained (CSD) tests with shear stresses of 70 kPa, 120 kPa, and 180 kPa. The effective stress paths from conventional consolidated undrained (CU) triaxial tests are also plotted for comparison. Three saturation degrees (100%, 95.8%, and 92.2%) were analyzed to evaluate their effects on the mechanical behavior of gassy dense sand.

From the effective stress path curves of consolidated undrained (CU) tests on dense sand in Fig. 5, it is observed that the slopes of the Critical State Lines (CSL) for dense sand under different degrees of saturation all equal 1.573. Comparing this value with the previously mentioned CSL slope of loose sand further confirms that saturation has minimal influence on the slope of the Critical State Line (CSL) for sand. By analyzing Fig. 5(a), (b), and (c), it is evident that the presence of a small amount of gas moderately affects the stress ratio at which dense sand specimens reach instability. Specifically, as the saturation decreases (from 100%, 95.8–92.2%), the corresponding instability stress ratios for gas-containing dense sand decrease progressively to 1.203, 1.199, and 1.196, showing a slight downward trend with limited variation. This pattern contrasts with that observed in gas-containing loose sand, where instability stress ratios increased with decreasing saturation. Furthermore, the effective stress paths from constant shear stress drained (CSD) tests on dense sand reveal that the derived instability lines consistently fall within the Potential Instability Zone. Under dense sand conditions, these instability lines are positioned closer to the Critical State Line (CSL) side of the zone.

By comparing the patterns reflected in Figs. 4 and 5, as shown in Fig. 6, the instability stress ratio of loose gassy sand under constant shear stress paths continuously increases with decreasing saturation, while the instability stress ratio of dense gassy sand exhibits a decreasing trend as saturation increases. For loose sand, the entrapped gas increases the compressibility of the pore fluid. During shearing, contractive behavior dominates, inducing partial drainage and suppressing the accumulation of positive excess pore water pressure. Under the same initial conditions, the decay of effective mean stress in gassy sand during undrained shearing is smaller than that in saturated sand. Consequently, higher stiffness and strength are observed. The presence of a small amount of gas improves the shear mechanical properties of loose gassy sand. For dense gassy sand, the soil skeleton exhibits dilative behavior during shearing. The gas-enhanced compressibility inhibits the development of negative pore water pressure in dilative materials. Accompanied by volumetric expansion, this results in a smaller increase in effective mean stress compared to saturated sand under identical conditions, manifesting as reduced stiffness and strength. Moreover, this adverse effect becomes more pronounced with higher gas content (i.e., lower saturation). Consequently, the effective stress ratio corresponding to the instability line exhibits a decreasing trend as saturation increases. This phenomenon in dense gassy sand has also been documented in the research findings of Hong et al.43.

Time-to-instability response analysis of gassy sand under constant shear drained (CSD) test conditions

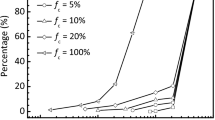

The time axes in Fig. 7 exclude the duration of shear ramping from zero to target constant shear stress, capturing solely the period of maintained constant shear stress. Figure 7(a) shows the time-to-instability response curves of loose gassy sand (Dr=29.8%) during the constant shear phase of consolidated drained (CSD) tests under varying saturation degrees. After undergoing the conventional drained shear phase, the specimens exhibited minimal axial deformation. Under constant shear stress paths, axial strain developed slowly until instability initiation (marked by red circles), after which rapid strain acceleration occurred. The results demonstrate that as saturation decreases (i.e., gas content increases), the time to instability for loose sand progressively increases. This delay is attributed to gas-induced retardation of deformation development, which slows the rate of effective stress reduction. Consequently, gassy sand requires a longer duration to reach the critical effective stress ratio triggering instability during the drained shear phase. Figure 7(b) presents the axial strain vs. time curves for dense gassy sand (Dr=89.5%) under CSD tests. The data reveal that specimen density significantly influences strain evolution: denser specimens exhibit greater resistance to instability under constant shear stress, requiring prolonged durations to reach instability. This behavior arises from the enhanced particle interlocking and stable soil skeleton in dense sand, which mitigates instability during the constant shear phase. Similar to loose gassy sand, lower saturation correlates with longer time-to-instability for dense gassy sand.

Figure 8 displays the distribution of time-to-instability for gassy sand under different constant shear stress levels. The position of instability points is closely related to the magnitude of the applied shear stress. As observed in Fig. 8, smaller constant shear stress values correspond to longer durations for specimens to reach instability. This phenomenon arises because lower shear stresses exert weaker shearing effects on the sand specimens, allowing them to maintain stability for a longer duration under continuously increasing pore pressure. Additionally, gassy dense sand exhibits slightly longer time-to-failure compared to loose sand. Under identical compaction states and constant shear stress levels, lower saturation degrees (i.e., higher gas content) further prolong the time required to reach specimen failure.

Effective stress paths in CSU test

Gas-bearing sand specimens with relative densities Dr of 29.8% and 89.5% were subjected to consolidated undrained constant shear stress (CSU) triaxial shear tests under constant shear stresses of 50 kPa, 100 kPa, and 140 kPa. The effective stress paths are shown in Figs. 9 and 10. Additionally, the Critical State Lines (CSL) and Instability Lines (IL) for gas-bearing sands at varying degrees of saturation, previously derived from CU tests, are plotted in the figures.

Figures 9 and 10 clearly show that the instability points from the CSU tests on gas-bearing sands with different densities and saturations predominantly fall within the Potential Instability Zone bounded by their corresponding CSL and IL. Although a few data points slightly exceed the boundaries of the Potential Instability Zone, this deviation is attributed to unavoidable experimental errors. It can therefore be concluded that for gas-bearing loose or dense sands with varying saturations, the effective stress paths under both constant shear drained (CSD) and consolidated undrained (CSU) test conditions enter the instability state within the Potential Instability Zone defined by their respective CSL and IL.

In Fig. 9, the effective stress path curves from CSU tests on gas-bearing loose sands at saturations of 100%, 95.3%, and 85.4% reveal that the ultimate stress ratio at instability approaches the critical state ratio of 1.573, with no pronounced influence of saturation on the ultimate stress ratio at instability. Similarly, Fig. 10 demonstrates that gas-bearing dense sands exhibit consistent ultimate stress ratios across varying saturations, averaging approximately 1.317, with no clear trend in saturation dependency.

Time-to-instability response analysis of gassy sand under constant shear undrained (CSU) test conditions

Figure 11(a) shows the axial strain versus time curves for gas-bearing loose sand during the undrained constant shear phase. The time axes in exclude the duration of shear ramping from zero to target constant shear stress. It is evident that after undergoing the conventional drained shear phase, the specimens exhibit minimal axial deformation. Moreover, under constant shear stress paths, axial strain develops gradually until the stress path reaches a specific instability point, where axial strain rapidly accelerates. Overall, lower saturation corresponds to shorter time to reach the instability point, a trend opposite to CSD test results. This phenomenon is attributed to the synchronized unloading of axial and confining pressures in CSU tests to maintain constant shear stress. The unloading process accelerates gas exsolution, delays the generation of negative pore pressure, and consequently facilitates specimen failure, thereby reducing the time to instability.

Figure 11(b) presents the axial strain versus time curves for gas-bearing dense sand during the undrained constant shear phase. Consistent with the behavior of gas-bearing loose sand, lower saturation leads to shorter time to instability. The primary distinction lies in the slightly longer time required for dense sand to reach failure compared to loose sand. This is due to the denser particle contacts and stiffer soil skeleton in dense specimens, which enhance resistance to instability under constant shear stress, prolonging the time to instability.

Figure 12 illustrates the axial strain versus time curves for gas-bearing loose sand under undrained conditions during the constant shear phase. The position of the instability point is strongly correlated with the magnitude of the constant shear stress: lower constant shear stress values result in longer times to instability. This occurs because smaller shear stresses cause less disturbance to the specimen’s skeleton structure, extending the stable phase. For specimens under identical constant shear stress, lower saturation (higher gas content) corresponds to shorter shear duration. This is explained by the accelerated gas exsolution during unloading, which promotes faster pore pressure buildup compared to saturated sand, leading to a more rapid reduction in effective confining pressure. Consequently, gas-bearing sand fails earlier than saturated sand under equivalent conditions.

Based on a comprehensive comparison of Figs. 7, 8, 11 and 12, this analysis summarizes the physical mechanisms behind the divergent effects of saturation (gas content) on stabilization time in CSD and CSU tests. The gas phase plays dual roles as an “energy dissipator” under drained conditions and a “pressure transmission medium” under undrained conditions.

In CSD tests, higher saturation shortens stabilization time. Increased gas content causes gas bubbles to occupy pore space discretely. This results in higher tortuosity of water flow paths and reduced drainage efficiency. Bubbles compress and rebound under shear but cannot escape through drainage valves (liquid-only drainage); this effect delays volumetric strain adjustment. In the effective stress equation: σ′=σ − uw + χ(ua−uw) (χ is gas contribution coefficient, σ′ is the effective stress, σ is the total stress, uw is the pore water pressure, and ua is the pore air pressure)44higher gas content intensifies χ fluctuations, requires gas-liquid pressure rebalancing, and slows overall stabilization. Loose sand exhibits enhanced contractive tendency, which prolongs drainage time45. While dense sand’s dilatancy is buffered by bubbles, this delays peak strength attainment. In Fig. 7(a), at constant shear stress (100 kPa), the saturation rises from 85.2 to 95.2%, and the stabilization time decreases from 4400 s to 3200 s, resulting in a 27% reduction.

In CSU tests, higher saturation prolongs stabilization time. Gas compressibility is much larger than that of water. Higher gas content means a more compressible phase. During shear-induced volumetric contraction, rapid bubble compression causes sharp pore water pressure rise. Effective stress collapse then accelerates strength loss. Local high pressure dissolves gas; dissolved gas expands fluid volume, further elevates pore water pressure, and causes pore pressure surge feedback. Discrete bubbles at low gas content slow gas dissolution/migration in liquid. Connected channels at high gas content become trapped under undrained confinement, preventing pressure dissipation. Gas heterogeneity concentrates compression/dissolution in shear zones, causing local pore water pressure spikes and accelerating failure. In Fig. 11(b), at constant shear stress (120 kPa), the saturation rises from 92.2 to 95.8%, and the stabilization time increases from 2800 s to 5000 s, resulting in a 78% increase.

Discussion

Testing on gassy sand is much more complex than testing on saturated sand, because it involves gas phase, liquid phase, solid phase three phases and their interactions (capillary action, dissolution, diffusion, hysteresis effects, etc.), and the states of these phases (degree of saturation, pore air pressure, pore water pressure) will dynamically change during the testing process. Precise control and measurement of these variables itself is full of challenges. Robust research should clearly state the limitations of the data, potential sources of error, the uncertainty range of conclusions, and avoid overinterpretation.

Although the authors strived to be meticulous and rigorous during the testing process, in this study, reasonable repeated tests were adopted, and sensitivity analysis of key parameters was considered. But it must be pointed out, the tests may still have the following limitations: ① Variability of soil samples, even from the same source, there exist natural variations in soil samples regarding microstructure, particle distribution, mineral composition. Achieving the target initial degree of saturation (Sr) for sandy soil specimens is very difficult and non-uniform, possibly introducing density differences, structural disturbance, or non-uniform saturation distribution; ② High-pressure saturation container apparatus may have problems like hysteresis, fluctuations, slow response, or insufficient accuracy. Drainage valve/vent valve response speed, sealing, dead volume influence. Non-ideal boundary conditions cause hindered fluid flow inside the specimen or uneven pressure gradient. The measurement accuracy of gas phase volume change is more affected by gas compressibility, temperature changes, tubing influence. Directly and precisely measuring gas discharge volume is more difficult than water; ③ Stress/pressure changes during testing may cause dissolved gas in water to exsolve or gas to dissolve into water, changing fluid volume and saturation; this process is difficult to precisely measure and quantify.

The impact of the above errors on the research conclusions is mainly reflected in: ① Due to non-uniform internal state of the specimen (saturation, gas content, etc.), localized deformation not being captured, the test results may be unable to represent the average behavior of the entire soil mass; stress paths may cause internal shear band formation, macroscopic measurements cannot reflect this localized phenomenon. For example, it may have some influence on judging the instability time of gassy sand specimens under constant shear stress conditions; ② May mask or distort true physical processes: For example, apparent volume change caused by dissolved gas exsolution may be mistaken for soil skeleton compression; pore water pressure measurement hysteresis leads to wrong understanding of the transient response of gassy sand.

Although objectively existing error factors in the tests may have minor influence on specific numerical values, the pattern trends obtained from this paper’s tests adopted parallel test verification, the patterns have universality. Sample preparation employed the moist-tamping method in present study. Previous studies indicate significantly different outcomes may arise from alternative methods (e.g., dry pluviation, water sedimentation). Future work will explicitly address how preparation methods affect triaxial tests on gassy sands. While this study treated gas content as the primary variable, subsequent research should: ① Systematically examine gas pressures at varying gas contents, and ② Quantify relationships between pressure and saturation liquid solubility.

Conclusions

This study conducted consolidated undrained (CU) tests, constant shear drained (CSD) tests, constant shear undrained (CSU) tests on gassy sand. The effective stress paths and instability time-response patterns of gassy sand under constant external loads with internal stress variations were obtained. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

1.

The presence of gas bubbles in gassy sand affects the peak shear strength. However, once the critical shear state is reached, the gas presence has negligible influence on the q/p′ ratio. Within the high saturation range considered in this study, the slope of the critical state line (CSL) for gassy sand remains unaffected by saturation, with MCSL=1.573.

-

2.

For gassy loose or dense sand with varying saturations, the points at which the effective stress paths enter an unstable state during CSD and CSU tests under constant shear stress paths consistently fall within the potential instability zone bounded by the critical state line (CSL) and the instability line (IL).

-

3.

For loose sand with low density, the enclosed gas increases the compressibility of pore fluids, leading to contractive behavior during shearing and inducing partial drainage responses. This inhibits the accumulation of positive excess pore water pressure. Under identical initial conditions, the decay amplitude of effective mean stress in gassy sand during undrained shearing is smaller than that in saturated sand. Thus, the presence of a small amount of gas improves the shear mechanical properties of loose gassy sand. For dense gassy sand, the soil skeleton exhibits dilative effects during shearing. The enhanced compressibility due to gas suppresses the development of negative pore water pressure in dilative materials. Concurrent volumetric expansion results in a smaller increase in effective mean stress compared to saturated sand under the same conditions. Higher gas content (i.e., lower saturation) exacerbates this adverse effect, causing the effective stress ratio corresponding to the instability line to decrease with increasing saturation.

-

4.

The axial strain-time curves of dense gassy sand during undrained constant shear stages follow the same trend as those of loose gassy sand: lower saturation leads to shorter times to reach instability. The primary difference is that dense gassy sand requires slightly longer time to reach specimen failure compared to loose sand. This is attributed to tighter interparticle contacts and a stiffer soil skeleton in dense specimens, which resist instability more effectively during constant shear stress stages, thereby prolonging the time to instability.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Wheeler, S. J. A conceptual model for soils containing large gas bubbles. Géotechnique 38, 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1988.38.3.389 (1988).

Grozic, J. L., Robertson, P. K. & Morgenstern, N. R. The behavior of loose gassy sand. Can. Geotech. J. 36, 482–492. https://doi.org/10.1139/t99-007 (1999). .

Vanneste, M., Sultan, N., Garziglia, S., Forsberg, C. F. & L’Heureux, J. S. Seafloor instabilities and sediment deformation processes: the need for integrated, multi-disciplinary investigations. Mar. Geol. 352, 183–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2014.01.005 (2014). .

Finno, R. J., Zhang, Y. & Buscarnera, G. Experimental validation of terzaghi’s effective stress principle for gassy sand. J. Geotech. Geoenviron Eng. 143, 04017092. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001797 (2017). .

Grozic, J. L. H., Imam, S. M., Robertson, P. K. & Morgenstern, N. R. Constitutive modeling of gassy sand behaviour. Can. Geotech. J. 42, 812–829. https://doi.org/10.1139/t05-015 (2005). .

He, J., Chu, J. & Ivanov, V. Mitigation of liquefaction of saturated sand using biogas. Géotechnique 63, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.SIP13.P.004 (2013).

Sobkowicz, J. C. & Morgenstern, N. R. The undrained equilibrium behaviour of gassy sediments. Can. Geotech. J. 21, 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1139/t84-048 (1984). .

Liu, T., Yang, X. & Zhang, Y. A review of gassy sediments: mechanical property, disaster simulation and in-situ test. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 915735. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.915735 (2022). .

Sladen, J. A., D’ Hollander, R. D., Krahn, J. & Mitchell, D. E. Back analysis of the nerlerk berm liquefaction slides. Can. Geotech. J. 22, 579–588. https://doi.org/10.1139/t85-077 (1985). .

Canal, M. et al. Slope failure dynamics and impacts from seafloor and shallow sub-seafloor geophysical data: case studies from the COSTA project. Mar. Geol. 213, 9–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2004.10.001 (2004). .

Yang, S. L., Kvalstad, T., Solheim, A. & Forsberg, C. F. Parameter studies of sediments in the Storegga Slide region. Geo-Mar. Lett. 26, 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00367-006-0023-5 (2006). .

Wang, Y., Kong, L. W., Wang, Y. L., Wang, M. & Cai, K. J. Deformation analysis of shallow gas-bearing ground from controlled gas release in Hangzhou Bay of China. Int. J. Geomech. 18, 04017122. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0001029 (2018).

Denk, E. W., Dunlap, W. A., Bryant, W. R., Milberger, L. J. & Whelan, T. J. A pressurized core barrel for sampling gas-charged marine sediments. In Proceedings of 13th Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, Texas 43–52. https://doi.org/10.4043/4120-MS (1981).

Miura, S. & Toki, S. A sample preparation method and its effect on static and cyclic deformation-strength properties of sand. Soils Found. 22, 61–77. https://doi.org/10.3208/sandf1972.22.61 (1982).

Grozic, J. L. H., Robertson, P. K. & Morgenstern, N. R. Cyclic liquefaction of loose gassy sand. Can. Geotech. J. 37, 843–856. https://doi.org/10.1139/t00-008 (2000). .

Sills, G. C., Wheeler, S. J., Thomas, S. D. & Gardner, T. N. Behaviour of offshore soils containing gas bubbles. Géotechnique 41, 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1991.41.2.227 (1991).

Okamura, M. et al. In-Situ desaturation test by air injection and its evaluation through field monitoring and multiphase flow simulation. J. Geotech. Geo Environ. Eng. 137, 643–652. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000483 (2011). .

Yegian, M. K., Eseller-Bayat, E., Alshawabkeh, A. & Ali, S. Induced-partial saturation for liquefaction mitigation: experimental investigation. J. Geotech. Geo Environ. Eng. 133, 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241 (2007).

Eseller-Bayat, E., Yegian, M. K., Alshawabkeh, A. & Gokyer, S. Liquefaction response of partially saturated sands. I: experimental results. J. Geotech. Geo Environ. Eng. 139, 863–871. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000815 (2013). .

Rebata-Landa, V. & Santamarina, J. C. Mechanical effects of biogenic nitrogen gas bubbles in soils. J. Geotech. Geo Environ. Eng. 138, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000571 (2012). .

Cristancho-Torres, E. & Larrahondo, J. M. Gassy sands: volume change induced by organic matter oxidation. Géotechnique Lett. 7, 174–178. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgele.16.00143 (2017). .

Daouadji, A., AlGali, H., Darve, F. & Zeghloul, A. Instability in granular materials: experimental evidence of diffuse mode of failure for loose sands. J. Eng. Mech. 136, 575–588. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0000101 (2010). .

Monkul, M. M., Yamamuro, J. A. & Lade, P. V. Failure, instability, and the second work increment in loose silty sand. Can. Geotech. J. 48, 943–955. https://doi.org/10.1139/t11-013 (2011).

Kong, L., Liu, W. Z., Yuan, Q. M. & Dong, T. Triaxial tests on gassy sandy soil under constant shear stress paths. Rock. Soil. Mech. 40, 3319–3326. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2018.1863 (2019).

Vega-Posada, C. A., Finno, R. J. & Zapata-Medina, D. G. Effect of gas on the mechanical behavior of medium dense sands. J. Geotech. Geoenviron Eng. 140, 04014063. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001163 (2015). .

Amaratunga, A. & Grozic, J. L. H. On the undrained unloading behaviour of gassy sands. Can. Geotech. J. 46, 1267–1276. https://doi.org/10.1139/T09-056 (2009). .

He, J. & Chu, J. Undrained responses of microbially desaturated sand under monotonic loading. J. Geotech. Geoenviron Eng. 140, 04014003. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001082 (2014). .

Hong, Y., Wang, L. Z., Ng, C. W. & Yang, B. Effect of initial pore pressure on undrained shear behaviour of fine-grained gassy soil. Can. Geotech. J. 54, 1592–1600. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2017-0015 (2017). .

Hill, R. A general theory of uniqueness and stability in elastic-plastic solids. J. Mech. Phys. Solid. 6, 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5096(58)90029-2 (1958). .

Chu, J., Leroueil, S. & Leong, W. K. Unstable behavior of sand and its implication for slope instability. Can. Geotech. J. 40, 873–885. https://doi.org/10.1139/t03-039 (2003).

Lade, P. V. & Pradel, D. Instability and plastic flow of soils I: experimental observations. J. Eng. Mech. 116, 2532–2550. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9399 (1990).

ASTM D4254-16. Standard Test Methods for Minimum Index Density and Unit Weight of Soils and Calculation of Relative Density (ASTM International, 2016).

ASTM D4253-16e1. Standard Test Methods for Maximum Index Density and Unit Weight of Soils Using a Vibratory Table (ASTM International, 2019).

ASTM D6913/D6913M-17. Standard Test Methods for particle-size Distribution (gradation) of Soils Using Sieve Analysis (ASTM International, 2021).

Wang, Y., Kong, L. W., Wang, M., Wang, Y. L. & Cheng, P. An improved specimen preparation method for marine shallow gas-bearing sand sediments and its validations. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. 13, 682–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2020.11.010 (2021). .

Xu, M. B. et al. Undrained shear mechanical behaviors of dense gassy sand. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge (2024).

Chen, Y. & Yang, J. Initiation of flow liquefaction in granular soil slopes: drained versus undrained conditions. Acta Geotech. 19, 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-023-01958-6 (2024).

Dong, Q. Y. et al. Drained instability in loose granular material. Int. J. Geomech. 16, 04015043. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0000524 (2015). .

Chu, J., Leong, W. K., Loke, W. L. & Wanatowski, D. Instability of loose sand under drained conditions. J. Geotech. Geoenviron Eng. 138, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000574 (2012). .

Daouadji, A., Hicher, P. Y., Jrad, M., Sukumaran, B. & Belouettar, S. Experimental and numerical investigation of diffuse instability in granular materials using a microstructural model under various loading paths. Géotechnique 63, 368–381. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.10.P.121 (2013). .

Ramos, A. M., Andrade, J. E. & Lizcano, A. Modelling diffuse instabilities in sands under drained conditions. Géotechnique 62, 471–478. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.10.P.109 (2012). .

Yang, J., Liang, L. B. & Chen, Y. Instability and liquefaction flow slide of granular soils: the role of initial shear stress. Acta Geotech. 17, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-021-01200-1 (2022).

Hong, Y., Wang, X. T., Wang, L. Z. & Gao, Z. W. A state-dependent constitutive model for coarse-grained gassy soil and its application in slope instability modelling. Comput. Geotech. 129, 103847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2020.103847 (2021). .

Liu, S. et al. A state surface model of unsaturated soil considering thermal and adsorptive effects. Comput. Geotech. 177, 106869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2024.106869 (2025).

Grozic, J. L. H. The Behavior of Loose Gassy Sand and Its Susceptibility to Liquefaction. Ph.D. thesis, (University of Alberta, 1999).

Acknowledgements

This research is financially supported by Guangzhou Metro Design & Research Institute Co. Ltd. Research Project, Grant NO. KY-2023-024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lijun Li: Formal analysis, Project administration. Zhu Yuan: Resources, Methodology. Dian Wang: Validation, Supervision. Youfu Pan: Investigation, Validation. Junshuai Zhang: formal analysis. Yong Wang: Data curation, Methodology. Zhiliang Sun: Writing - original Draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Yuan, Z., Wang, D. et al. Experimental study on mechanical response characteristics of gassy sand under constant shear stress paths. Sci Rep 15, 28412 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13897-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13897-1