Abstract

The increasing proliferation of residential photovoltaic (PV) systems in microgrids offers significant potential for enhancing renewable energy self-consumption and reducing dependency on external grid power. However, the inherent intermittency of solar generation and the mismatch between peak generation and household demand patterns require effective demand-side flexibility. Traditional demand response programs, often based solely on financial incentives or dynamic pricing, have demonstrated limited success in sustaining user engagement. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a novel gamification-driven demand response framework for PV-integrated microgrids, designed to simultaneously optimize operational cost, renewable energy utilization, user participation, and load-shifting comfort. By integrating behavioral adaptation modeling directly into the optimization process, the proposed framework captures the nonlinear and dynamic responses of households to gamification incentives, allowing for a more realistic and behaviorally-grounded approach to microgrid scheduling. The optimization problem is formulated as a multi-objective model and solved using the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm III (NSGA-III), which efficiently explores the trade-offs between cost minimization, PV self-consumption maximization, gamification-driven participation enhancement, and household comfort preservation. Compared to conventional demand response mechanisms, the proposed method explicitly incorporates evolving user behavior, dynamic incentive distribution, and social influence propagation, ensuring that demand-side flexibility is unlocked through both financial and psychological mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing penetration of renewable energy sources, particularly photovoltaic (PV) systems, has significantly altered the landscape of microgrid energy management. Unlike conventional centralized power generation, PV-based microgrids operate in a decentralized manner, relying heavily on weather-dependent energy production1,2. This intermittency presents fundamental challenges in balancing supply and demand, often leading to energy curtailment, inefficient utilization of renewable resources, and increased dependency on the main grid3. Energy storage systems have emerged as a partial solution to mitigate these imbalances; however, their effectiveness depends on well-structured scheduling and control strategies4,5.

A critical component of modern microgrid operation is demand-side management, which encourages consumers to modify their energy consumption patterns to align with renewable generation availability6. Traditional demand response programs, which rely on direct financial incentives or static pricing models, often fail to achieve widespread participation due to user inertia, behavioral resistance, and a lack of direct engagement7. Recent research has emphasized the role of behavioral economics and psychology in shaping energy consumption decisions, highlighting the need for innovative approaches that move beyond purely economic incentives. In this context, gamification–integrating game-like elements into non-game settings–has gained traction as a means to enhance consumer engagement. By leveraging mechanisms such as point-based rewards, leaderboard rankings, social competition, and peer influence, gamification can transform demand response into an interactive and participatory process, fostering deeper user involvement in microgrid optimization.

Despite the growing body of work on gamified demand response, existing methodologies predominantly focus on heuristic reward allocation or rule-based engagement mechanisms. These approaches lack systematic optimization frameworks that rigorously balance energy cost minimization, PV utilization maximization, and user engagement8. Additionally, most current research neglects the dynamic interplay between demand-side behavior and supply-side constraints, leading to suboptimal solutions that either fail to fully engage consumers or impose excessive disruptions on daily activities. There is a need for a holistic, multi-objective optimization framework that simultaneously considers microgrid efficiency, economic feasibility, and user participation dynamics.

This paper presents a novel gamification-incentivized demand response framework for PV-integrated microgrids, formulated as a multi-objective optimization problem. The proposed approach leverages the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm III (NSGA-III) to explore optimal trade-offs between operational cost minimization, renewable energy utilization, user participation maximization, and load-shifting comfort. By incorporating behavioral adaptation models within the optimization framework, this study captures the dynamic and nonlinear nature of consumer response to gamified incentives, ensuring realistic and practical demand response strategies. Unlike existing works that rely on predefined incentive schemes or simplified participation models, this research integrates advanced mathematical modeling techniques to rigorously quantify the effects of gamification on energy behavior, ensuring an adaptive and data-driven approach to microgrid optimization. The optimization model introduced in this paper consists of a two-part formulation. The first part defines the objective functions, which encompass minimizing microgrid operational costs, maximizing PV energy self-consumption, enhancing gamification-driven user participation, and minimizing user discomfort from load shifting. The second part incorporates a comprehensive set of constraints, including power balance equations, PV generation limits, battery charging/discharging constraints, and user flexibility boundaries. Additionally, a dynamic incentive allocation model is embedded within the optimization process, ensuring that rewards are distributed in a manner that aligns with both system-level energy objectives and individual user engagement levels.

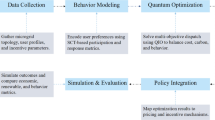

Figure 1 illustrates the system-level architecture of a photovoltaic-integrated microgrid enhanced with gamification and behavioral demand response. At its core is a central controller that coordinates the energy flows among rooftop PV systems, energy storage units, the external power grid, and residential loads. The demand response module dynamically adjusts consumption based on user behavior, which is influenced by gamification incentives such as rewards, rankings, and peer competition. These incentives promote active user engagement, enabling more flexible load shifting and improved self-consumption of renewable energy. The architecture represents an integrated cyber-physical-social energy system that optimizes both technical performance and human participation for sustainable microgrid operation.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach, extensive case studies are conducted using realistic microgrid data, incorporating stochastic PV generation profiles, time-varying electricity prices, and diverse consumer behavior patterns. The simulation results highlight the advantages of the proposed framework in achieving cost savings, increasing PV self-consumption, and enhancing user engagement compared to conventional demand response models. The results also reveal the importance of balancing incentive distribution, as excessive reliance on financial rewards can lead to diminishing marginal returns, whereas strategic integration of social and competitive elements can sustain long-term participation. The primary contributions of this research are fourfold: First, this study introduces a novel NSGA-III-based optimization framework that explicitly integrates gamification-driven demand response with PV-integrated microgrid operation, bridging the gap between behavioral economics and power system optimization.

Second, it develops an advanced mathematical modeling framework that captures the nonlinear and dynamic nature of user participation in demand-side management, ensuring realistic and adaptive incentive design.

Third, the research enhances NSGA-III’s constraint-handling capability through the incorporation of an adaptive penalty function, significantly improving the feasibility and convergence of the optimization model.

Fourth, this study conducts comprehensive numerical experiments and case studies, validating the effectiveness of the proposed approach in optimizing microgrid performance while fostering sustained user engagement.

Literature review

One of the key research areas in microgrid operation is demand response, which has been extensively studied as a mechanism to balance supply and demand, particularly in systems with high PV penetration. Early demand response programs relied on direct load control and dynamic pricing schemes, where consumers were incentivized to adjust their consumption patterns based on real-time electricity prices9. These models typically assumed rational decision-making from users, where financial incentives were sufficient to influence energy consumption behavior10. However, empirical studies have demonstrated that consumer participation in demand response is often inconsistent, with engagement levels varying based on social, psychological, and contextual factors. As a result, research has increasingly focused on behavioral demand response models that incorporate user preferences, comfort constraints, and incentive structures beyond financial compensation11. Gamification has recently emerged as a promising approach to enhance consumer participation in energy management. The concept involves applying game-like elements, such as point-based rewards, leaderboard rankings, peer competition, and social influence, to encourage users to actively participate in energy-saving behaviors12,13. Several studies have explored the potential of gamification in demand-side management, demonstrating that well-designed incentive mechanisms can significantly increase engagement levels and improve energy efficiency. However, existing works on gamification-driven demand response often rely on heuristic or empirical rule-based methods, lacking a rigorous mathematical foundation to optimize incentive structures dynamically. Furthermore, many existing models treat gamification as an independent layer added to energy management rather than integrating it directly into the microgrid optimization framework14.

In parallel, evolutionary algorithms have gained significant attention in solving multi-objective optimization problems related to power system operation. Genetic algorithms, particle swarm optimization, and differential evolution have been widely applied to optimize energy scheduling, battery management, and grid operation15. Among these, the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA) family has been particularly effective in handling conflicting objectives in power system optimization. The latest version, NSGA-III, introduces a reference point-based selection mechanism that enhances diversity in high-dimensional objective spaces16,17. While NSGA-III has been successfully applied in various engineering fields, its integration with gamification-driven demand response remains unexplored. Most existing studies utilizing NSGA-III in energy systems focus on traditional cost- and efficiency-based objectives without incorporating user behavior dynamics or incentive-driven participation models.

The interaction between renewable energy utilization and consumer participation has also been a major topic in the literature. Studies on PV-integrated microgrids emphasize the need for self-consumption strategies that minimize reliance on external grid supply. Various optimization methods have been proposed to maximize PV energy utilization, including rule-based scheduling, model predictive control, and reinforcement learning. While these approaches improve energy efficiency, they often overlook the role of human behavior in shaping electricity consumption patterns2,18,19. Behavioral studies have shown that user engagement in energy-saving activities is highly dependent on psychological factors, such as perceived benefits, competition, and social norms20. This highlights the necessity of integrating gamification-driven participation models within optimization frameworks to ensure effective and sustained engagement. Another critical aspect of microgrid optimization is constraint handling, particularly in evolutionary algorithms. Traditional constraint-handling techniques in multi-objective optimization often involve penalty functions, where infeasible solutions are penalized based on the severity of constraint violations. While effective, these methods can lead to premature convergence and suboptimal exploration of the solution space21,22. Recent advancements have introduced adaptive penalty mechanisms that dynamically adjust constraint weights based on evolutionary progress, improving convergence rates and solution feasibility. Despite these advancements, constraint-handling techniques in the context of gamification-driven demand response have not been extensively studied. Existing models typically impose static constraints on user participation, failing to account for the dynamic nature of engagement levels and behavioral adaptation over time. The integration of multi-objective optimization and behavioral demand response also poses computational challenges. Most demand response studies that incorporate user behavior rely on agent-based modeling or empirical surveys to estimate participation probabilities23. While these methods provide valuable insights, they are often computationally intensive and lack adaptability in real-time optimization frameworks. Machine learning techniques have been explored to predict user responses to different incentive schemes, enabling adaptive control strategies that adjust incentives dynamically based on real-time participation levels. However, the majority of these approaches operate independently from the optimization process, limiting their ability to influence decision-making directly. A fully integrated approach that combines data-driven behavior modeling with evolutionary optimization is still lacking in the literature.

Problem formulation and methodology

The optimization framework developed in this paper integrates mathematical modeling of the microgrid’s physical and operational constraints with the behavioral dynamics induced by gamification-driven demand response. This section first establishes the comprehensive mathematical formulation, describing the objective functions and system constraints that govern the technical operation of the PV-integrated microgrid. Following the modeling component, the methodology subsection details the optimization algorithm–tailored NSGA-III–and its specific adaptations to handle the coupled physical-behavioral optimization landscape introduced by the proposed framework. The mathematical model formalizes the microgrid’s operational objectives, encompassing cost minimization, renewable self-consumption enhancement, gamification-driven participation maximization, and discomfort minimization. These objectives are linked through a series of constraints capturing power balance, PV generation limits, battery operation, peer-to-peer energy trading, and user behavior dynamics. Crucially, the behavioral participation model reflects the evolution of household engagement in response to varying incentive structures and social competition, capturing the interplay between individual flexibility, peer influence, and incentive saturation. This integrated mathematical foundation ensures that gamification incentives are not treated as a static overlay but rather as an endogenous component of the energy scheduling process itself. The second part of this section focuses on the methodological design, presenting the customized NSGA-III procedure developed to solve this multi-objective optimization problem. Specific algorithmic innovations are introduced to enhance both computational efficiency and behavioral realism, including behavior-aware population initialization, adaptive penalty functions for constraint handling, and engagement feedback mechanisms that dynamically adjust evolutionary search based on real-time changes in participation patterns. These enhancements ensure that the optimization process does not merely find technically feasible solutions but actively steers the microgrid toward socially sustainable and behaviorally plausible operating points, fully integrating technical and behavioral co-optimization within a unified framework.

Gamification utility is the heart of this optimization problem, driving user engagement, participation, and collaboration in the microgrid system. The first term incorporates individual engagement (\(\Gamma _{i,t}^{\text {part}}\)) and leaderboard-based rewards (\(\Lambda _{i,k,t}^{\text {badge}}\)), ensuring users are incentivized for sustained participation. The second term captures the peer-to-peer (P2P) trading influence through transaction volume (\(\Upsilon _{i,j,t}^{\text {trade}}\)) and cooperative missions (\(\Phi _{i,t}^{\text {coop}}\)), fostering community-wide energy management. The last term dynamically models reward allocation using a sigmoid function, balancing reward saturation (\(\chi _{i,k,t}^{\text {reward}}\)) with behavioral inertia (\(\rho _{i,t}^{\text {shift}}\)), governed by a user-specific sensitivity parameter (\(\beta _{i,t}\)). This ensures that the reward structure smoothly adapts to different user behaviors while maintaining fairness across diverse participation levels.

Minimizing operational costs ensures the microgrid remains financially sustainable while still promoting user participation. The first term accounts for grid energy costs (\(P_{i,t}^{\text {grid}}\)), where pricing (\(\pi _{t}^{\text {dyn}}\)) follows a dynamic tariff based on real-time market conditions. Peer-to-peer energy trades (\(P_{i,j,t}^{\text {trade}}\)) introduce an additional cost, weighted by competition intensity (\(\tau _{i,t}^{\text {comp}}\)), ensuring efficient energy exchange. The second term captures incentive costs, balancing gamification-driven financial outflows (\(\Upsilon _{i,t}^{\text {inc}}\)) and reward distributions (\(\zeta _{i,k,t}^{\text {reward}}\)) across different participation levels. The final term represents battery storage and maintenance costs, where (\(\varphi _{i,t}^{\text {stor}}\)) models storage degradation, and (\(\gamma _{i,t}^{\text {main}} \cdot \xi _{i,t}^{\text {life}}\)) reflects long-term maintenance expenses, ensuring microgrid assets are optimally managed.

Maximizing renewable energy utilization is crucial for both sustainability and operational efficiency. The first term penalizes PV curtailment, ensuring that generated solar energy (\(P_{i,t}^{\text {PV}}\)) is maximally used before being wasted (\(P_{i,t}^{\text {curt}}\)). The second term prioritizes local P2P trading, increasing microgrid self-sufficiency by maximizing energy exchanged among users rather than relying on the macro-grid. The final term introduces a battery utilization efficiency metric, optimizing the balance between charging and discharging cycles to ensure longer battery lifespan and reduced dependency on external power sources.

User discomfort must be minimized to ensure gamification-driven demand response remains socially acceptable. The first term models habitual adaptation difficulty, where (\(\rho _{i,t}^{\text {shift}}\)) represents total shifted load, and (\(\theta _{i,t}^{\text {habit}}\)) captures the user’s behavioral resistance. The second term

To generate new solutions, NSGA-III applies genetic operators. The crossover operator creates new candidate solutions by blending two parent solutions, ensuring genetic variation. The mutation operator introduces random perturbations, preventing the algorithm from getting stuck in local optima.

The termination criterion ensures that the algorithm stops evolving when the objective values converge, indicating that further iterations no longer yield significant improvements.

The final decision-making step selects the best trade-off solution from the Pareto-optimal front, where weights \(w_m\) reflect decision-maker preferences, ensuring an optimized microgrid control strategy.

To ensure that all physical and behavioral constraints are respected, NSGA-III uses an adaptive penalty method where constraint violations \(g_c(\varvec{\Psi })\) are incorporated into the objective function. The penalty function scales dynamically using an adaptive weight \(\lambda _c\), increasing for infeasible solutions and relaxing for feasible ones to guide the search toward valid solutions without unnecessarily restricting exploration.

The penalty weight update equation ensures that the constraint violation penalties are dynamically adjusted during the optimization process. If a constraint \(g_c(\varvec{\Psi })\) is violated frequently, its corresponding penalty weight \(\lambda _c\) increases, forcing the algorithm to avoid infeasible solutions. The scaling factor \(\eta\) determines how aggressively the penalty changes based on the normalized constraint violation.

To prevent premature convergence and ensure efficient search, NSGA-III applies decision variable scaling, normalizing all variables between zero and one. This prevents any single variable from dominating the optimization process due to differences in magnitude.

The environmental selection mechanism ensures that only the most promising solutions survive each generation. NSGA-III selects the next population \(\mathbb {P}_{t+1}\) from the current generation \(\mathbb {P}_{t}\) and the newly generated offspring population \(\mathbb {P}_{\text {offspring}}\) while maintaining diversity and Pareto-optimality.

For cases where hybrid optimization techniques are integrated, NSGA-III can incorporate gradient-based refinement to fine-tune solutions using an adaptive step size \(\zeta _t\), guided by the gradient of an auxiliary function \(J(\varvec{\Psi })\). This approach improves local convergence speed while preserving NSGA-III’s global exploration capabilities.

The final decision-making equation selects the optimal solution \(\varvec{\Psi }^*\) from the first Pareto front \(\mathbb {F}_1\) by maximizing a weighted objective function that includes both performance and constraint penalties. The weight factors \(\omega _m\) reflect the relative importance of each objective, ensuring a practical, balanced trade-off among cost, energy efficiency, user behavior, and system resilience.

Results

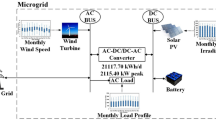

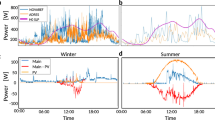

To evaluate the performance of the proposed NSGA-III-based gamification-driven demand response optimization framework, a detailed case study is conducted using a realistic PV-integrated microgrid system. The microgrid consists of 150 residential consumers, each equipped with a rooftop PV system ranging from 3 to 10 kW, depending on household size and available roof space. The total installed PV capacity in the microgrid is 1.2 MW, with an average daily solar generation of 4.8 MWh, varying seasonally based on historical weather data. Each household is also equipped with a smart meter that records energy consumption, PV generation, and battery status at a resolution of one-minute intervals. In addition, 50% of the households are equipped with battery storage units, ranging from 5 kWh to 15 kWh, with round-trip efficiency varying between 85 and 95%. The total controllable load, including shiftable appliances such as washing machines, dishwashers, and electric vehicle charging, accounts for approximately 40% of the total energy demand in the microgrid, allowing for significant flexibility in demand-side management.

To model user behavior in response to gamification incentives, real-world behavioral survey data on energy consumption habits and response to incentives are incorporated. User engagement is categorized into three groups: high participation (30%), moderate participation (50%), and low participation (20%), with participation levels dynamically evolving based on historical incentive records. The reward system includes virtual points that can be redeemed for real monetary incentives, with an average reward distribution budget of 5000 USD per month across all participants. The probability of users shifting their loads is modeled using a logistic function, where the likelihood of response increases as the incentive value rises beyond a predefined threshold of 0.05 USD per kWh. Data on electricity prices, PV output, and load profiles are obtained from real-world energy market datasets, including the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) and National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) datasets, ensuring that the case study reflects practical energy market conditions.

The simulation considers a one-year period with a five-minute time resolution, amounting to a total of 105,120 time steps. To account for uncertainties in PV generation and electricity demand, stochastic models based on Gaussian distribution with standard deviations of 15% and 10%, respectively, are incorporated. A peer-to-peer energy trading mechanism is also included, allowing prosumers to sell excess PV energy at dynamic market rates, with trading volumes constrained to a maximum of 50% of individual PV generation. The microgrid is assumed to have a maximum grid import capacity of 1.5 MW to ensure stability and prevent excessive reliance on external energy sources.

The proposed optimization framework is implemented in Python using TensorFlow and NumPy for behavioral modeling, while the NSGA-III evolutionary algorithm is executed using the DEAP (Distributed Evolutionary Algorithms in Python) library. The optimization problem is solved on a high-performance computing cluster with 64-core AMD EPYC 7742 processors, 512 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA A100 GPU for parallelized computations. The total number of initial candidate solutions is set to 500, with an evolution process spanning 1000 generations. Each generation involves crossover and mutation rates of 0.8 and 0.1, respectively, ensuring sufficient exploration of the solution space. The multi-objective optimization process is parallelized across 32 cores to accelerate convergence. The computational time for a single optimization run varies between 6 and 12 hours, depending on the complexity of the scenario. Convergence is monitored using the hypervolume indicator and generational distance metrics, ensuring that the algorithm reaches a stable Pareto-optimal front. The adaptive penalty function for constraint handling dynamically adjusts its weight parameters every 50 generations, preventing premature convergence and improving solution feasibility. To validate the robustness of the proposed model, Monte Carlo simulations with 5000 iterations are conducted, introducing variations in PV generation, electricity prices, and user engagement probabilities. The optimization results are compared against benchmark methods, including a conventional rule-based demand response strategy and a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP)-based microgrid scheduling approach. The effectiveness of the proposed method is evaluated based on key performance indicators, including total cost savings, renewable energy self-consumption, user engagement rates, and Pareto front diversity. The final results provide insights into the trade-offs between cost reduction, renewable energy integration, and gamification-driven user participation in microgrid optimization.

Figure 2 presents the distribution of rooftop photovoltaic capacities across all 150 households in the microgrid, shown as a histogram with an overlaid kernel density estimate (kde) curve to provide a smooth visual representation of the capacity distribution pattern. pv capacities in the microgrid range from 3 kw to 10 kw per household, reflecting typical variations in roof size, household income, and initial investment preferences. the x-axis represents the installed pv capacity in kilowatts, while the y-axis shows the number of households within each capacity range. the histogram reveals a clear concentration around 4.5 kw to 6 kw, indicating that most households have chosen medium-sized installations, likely balancing affordability and energy independence goals. A secondary peak appears around 8 kw, representing a distinct group of larger prosumers who have installed oversized pv systems either to maximize feed-in revenue or to achieve greater self-sufficiency. these larger systems tend to belong to households with higher energy consumption (such as those owning electric vehicles or running home-based businesses), or those who are particularly environmentally conscious. at the lower end, only a small number of households have pv capacities below 4 kw, likely reflecting either smaller properties with limited roof space or more conservative adopters who installed their systems several years ago when pv prices were higher. the smooth kde overlay helps highlight these patterns, ensuring that subtle distribution features are visible even if the raw histogram bins are coarser.

Figure 3 presents the distribution of financial incentives allocated to each household over a 12-month period, shown as a scatter plot where each point represents the incentive received by a particular household in a given month. a smooth trend line overlays the scatter points, illustrating the general evolution of average incentives over the year. individual monthly incentives range from approximately 50 usd to nearly 200 usd, reflecting the diversity of household participation levels, responsiveness to gamification prompts, and technical flexibility to shift loads. the x-axis represents the month, while the y-axis shows the incentive amount in usd. Several important patterns emerge from this visualization. first, incentives exhibit clear seasonal variation, with the average reward increasing steadily from january to july, peaking in august, and gradually declining toward december. this seasonal pattern aligns closely with pv generation potential, indicating that gamification incentives are dynamically adapted to match periods of high solar availability, when load shifting offers the greatest operational and economic value. second, the spread of individual household incentives widens considerably during summer months, with some households earning more than 180 usd per month, while others receive less than 70 usd despite the higher overall budget. this divergence reflects the emergence of super-participants—highly engaged users who fully exploit gamification rewards by aggressively shifting loads—alongside more passive households who contribute less flexibility.

Figure 4 presents a detailed scatter density visualization of the relationship between daily photovoltaic generation and household electricity demand across 150 microgrid households. the x-axis represents the average pv generation per household in kilowatts, while the y-axis reflects the corresponding average daily electricity demand of each household. the data spans a full year, capturing seasonal variations and weather-induced fluctuations in solar power output. pv generation in this microgrid ranges between 0 kw and 9.3 kw per day, depending on panel size, solar irradiance, and weather conditions. household load, in contrast, fluctuates between 0.5 kw and 3.5 kw on average, influenced by appliance usage, occupancy, and seasonal heating or cooling needs. the color density in this figure highlights clusters where most households operate, showing clear zones of typical generation-load combinations, as well as outliers indicating either very high pv production or unusually high electricity consumption. A critical insight from this figure is the significant concentration of households in the region where pv generation ranges from 3.5 kw to 5.5 kw per day, while average load falls between 1.5 kw and 2.5 kw. this indicates that under typical weather conditions, households have sufficient pv output to cover their base loads, especially during sunny days. however, during cloudy or rainy periods, pv generation drops below 2 kw per day for many households, increasing the reliance on external grid supply. the upper right corner of the density plot captures prosumers with oversized pv systems who consistently generate above 7 kw per day, allowing for substantial surplus energy export to the grid or peer-to-peer trading. this pattern is especially pronounced during summer months, when solar irradiance peaks.

Figure 5 presents a bivariate histogram visualizing the relationship between the average grid electricity imported by each household and the average pv electricity exported back to the grid. each point in this plot represents one of the 150 households in the microgrid, with the x-axis showing the daily grid import (in kilowatts) and the y-axis showing the daily pv export. the color intensity of each bin indicates the number of households falling into that particular import-export combination. household grid imports in this microgrid range between 0 and 3.0 kw per day, while pv exports vary from 0 kw to a maximum of 2.0 kw per day, reflecting the diversity in both household demand profiles and installed pv capacities. A clear concentration of households is visible in the lower-left region of the plot, where grid import is relatively low (between 0.5 and 1.5 kw per day) and pv export remains below 0.5 kw per day. this represents households with well-sized pv systems that are largely self-sufficient, producing just enough electricity to meet their demand without significant surplus. on the other hand, a smaller but distinct cluster emerges in the upper-left corner, where households export over 1.5 kw daily while importing very little from the grid. these are likely households with oversized pv systems that consistently generate surplus energy, which they export back to the grid under feed-in tariff arrangements.

Figure 6 presents a stacked area plot illustrating how the demand response participation levels of the 150 households evolve over a period of 12 months. the x-axis represents the month, from january to december, while the y-axis shows the% of households in each of the three engagement categories: high participation, moderate participation, and low participation. the area covered by each color represents the proportion of households within each category during each month. at the start of the year, approximately 30% of households belong to the high participation group, 50% are in the moderate participation group, and the remaining 20% show low or minimal participation in demand response programs. As the year progresses, participation levels fluctuate in response to seasonal energy demand changes, weather variability affecting pv generation, and adjustments to the gamification incentive structure. during spring and summer months, especially from april to august, the proportion of high participation users increases steadily to nearly 40%, reflecting the positive response to higher pv generation and more attractive incentives for load shifting and self-consumption. during this period, the number of low participation households decreases to below 15%, indicating that well-timed and effectively communicated incentives successfully activate previously disengaged users. this seasonal shift highlights the importance of aligning demand response programs with periods of high solar generation when the value of load shifting is highest.

Figure 7 presents a boxen plot that visualizes the hourly distribution of electric vehicle charging demand across all 150 households in the microgrid. the x-axis represents the 24 h of a day, while the y-axis displays the charging load in kilowatts. each vertical boxen plot reflects the statistical distribution of ev charging load at that specific hour, with the plot width capturing the density of data points. this type of visualization is particularly well-suited for understanding the full spread of charging behavior, especially for data with potential outliers or heavy tails, which are common in residential charging patterns. the overall range of charging load spans from 0 kw up to 7 kw per household, with strong clustering at lower levels, but occasional extreme spikes in certain hours indicating high-power charging events. The figure reveals a strong time-dependent pattern in ev charging behavior. overnight charging, from 22:00 to 06:00, accounts for a substantial portion of the total charging load, with median values consistently above 2 kw during these hours. this aligns with the typical behavior of homeowners returning in the evening and plugging in their vehicles to charge overnight when electricity prices are lower. between 07:00 and 16:00, the charging load decreases sharply, with median values falling below 0.5 kw, reflecting the absence of vehicles as residents commute to work. however, there is a noticeable secondary peak beginning around 17:00 and lasting until 21:00, where both median and upper quartile values increase significantly, with several households registering loads close to 5 kw during this evening window.

Figure 8 presents a histogram overlaid with a cumulative density function (cdf) curve, illustrating how gamification incentives were utilized by the 150 households over the 12-month period. the x-axis represents the average incentive amount redeemed per household each month, measured in us dollars, while the y-axis on the left shows the number of households within each incentive range. the cdf curve, plotted against the right y-axis, represents the cumulative percentage of households that have redeemed up to a given incentive amount. the histogram bins cover incentive values from 50 to 200 usd per month, corresponding to the monthly reward pool allocated for gamification activities such as load shifting, peak shaving, and self-consumption enhancement. The histogram reveals a highly skewed distribution, with the majority of households redeeming relatively modest incentives between 60 and 110 usd per month. approximately 50% of households fall into this range, indicating that moderate participation yields steady but unspectacular rewards. the cdf curve confirms this concentration, with a steep rise in cumulative participation within this band. at the upper end, fewer than 10% of households consistently earn over 150 usd per month, reflecting either very active participation or particularly flexible load profiles that allow frequent high-value load shifting. these high-reward households, while small in number, contribute disproportionately to overall demand response effectiveness, highlighting the importance of designing attractive rewards for this highly engaged group while maintaining fairness for more typical users.

Figure 9 presents the final pareto front obtained from solving the multi-objective optimization problem using nsga-iii for the gamification-driven microgrid operation. the x-axis represents the total operational cost of the microgrid, expressed in us dollars, while the y-axis indicates the final participation rate of all households in the gamified demand response program, expressed as a percentage. each point on this pareto front represents one non-dominated solution, meaning each point reflects a specific trade-off between operational cost and household participation. the range of operational costs across the front spans from approximately 8100 usd to 12400 usd, while participation rates vary between roughly 40% at the low end and close to 85% at the upper extreme. the clear downward slope of the front confirms that higher participation can be achieved, but at the cost of increased financial incentives, requiring greater microgrid operational expenditure. What makes this figure particularly important is the clear visualization of conflicting objectives inherent to this problem. the solutions concentrated near the left side, where costs are minimized, show participation rates hovering between 40% and 55%. these represent low-incentive strategies where only the most enthusiastic and naturally engaged users participate in the demand response program. moving right along the pareto front, costs gradually rise, but participation rates improve significantly, surpassing 70% and eventually peaking at 85%. these high-cost solutions reflect aggressive incentive schemes where substantial financial rewards are distributed, successfully mobilizing even previously disengaged users into active participants. this pareto structure provides decision-makers with flexibility to select a strategy that aligns with either budget constraints or participation targets, rather than enforcing a single, rigid objective.

Figure 10 presents the incentive-efficiency trade-off curve, which illustrates the relationship between the average monthly incentive provided to each household and the resulting self-consumption rate achieved in the optimized microgrid operation. the x-axis measures the average incentive per household, ranging from 50 usd to 200 usd per month, while the y-axis captures the corresponding self-consumption rate, which spans from approximately 60–83.5%. each point represents an optimized solution derived from nsga-iii, reflecting a unique combination of economic input and operational performance. the gradual upward trend demonstrates a clear positive correlation between financial rewards and household flexibility, confirming that gamification, when properly designed, can meaningfully enhance renewable energy utilization within the microgrid. A critical observation from this curve is the diminishing return effect beyond a certain incentive threshold. when average incentives are increased from 50 usd to around 120 usd per month, the self-consumption rate rises steeply from 60% to approximately 77%, indicating that initial financial encouragement successfully triggers flexible load shifting and self-consumption behavior. however, beyond 150 usd per month, further increases in incentive size produce only marginal improvements, with self-consumption asymptotically approaching a saturation point near 83.5%. this saturation reflects the practical and physical limitations of household flexibility—regardless of incentive level, there are structural and behavioral limits to how much load shifting is feasible within daily routines and appliance constraints.

Figure 11 presents a dual-axis timeline demonstrating the dynamic relationship between household participation rates and grid import reduction across 12 months. the left y-axis measures the average participation rate among all households, which starts at approximately 40% in january and gradually rises to 75% by august. the right y-axis measures the average reduction in grid import (relative to the baseline) achieved each month, which starts at around 5% in january and climbs steadily to nearly 30% in july and august. the clear synchronization between these two curves provides direct empirical evidence that higher engagement directly translates into enhanced microgrid resilience, defined here as reduced dependency on external grid supply. The seasonal trends visible in this figure align closely with both behavioral and technical drivers. during spring and summer months, higher solar generation coincides with stronger participation incentives, encouraging more households to actively shift their loads to match pv availability. this is reflected in both the sharp rise in participation, which reaches 72% in july, and the parallel reduction in grid import, which reaches its maximum at the same time. this confirms that behavioral flexibility is not only achievable but directly contributes to the operational resilience of the microgrid, reducing the need for expensive grid imports at times when pv generation is abundant.

Conclusion

This paper presents a novel optimization framework for gamification-driven demand response in photovoltaic-integrated residential microgrids, addressing the critical need for balancing operational cost, renewable self-consumption, user participation, and residential comfort. Unlike conventional demand-side management models that rely solely on static pricing signals or basic financial incentives, this work introduces a dynamic gamification layer directly embedded within the energy scheduling process. By leveraging NSGA-III, the proposed framework simultaneously optimizes four conflicting objectives–minimizing operational cost, maximizing renewable energy utilization, enhancing user participation through gamification, and minimizing user discomfort caused by load shifting. This multi-objective formulation explicitly captures the interplay between technical and behavioral dynamics, creating an integrated optimization environment that reflects both engineering constraints and social participation patterns. Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of the proposed gamification-driven demand response framework, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the behavioral adaptation model relies on static parameterization derived from historical survey data, which may not fully capture long-term user fatigue, novelty decay, or the evolving psychological responses to gamification stimuli. Future extensions could incorporate online learning or adaptive modeling to dynamically track changes in user engagement over time. Second, while the framework considers multiple incentive mechanisms (e.g., financial, social, competitive), it does not explicitly account for demographic, cultural, or socioeconomic heterogeneity, which can significantly influence participation behavior across different regions. Third, the simulation environment assumes ideal communication infrastructure and neglects potential latency, data privacy, and cybersecurity issues that could arise in real-world deployment. Lastly, the scalability of the NSGA-III optimization process may be challenged in larger microgrids with thousands of agents, suggesting the need for further exploration of hierarchical, distributed, or surrogate-assisted evolutionary algorithms. Addressing these limitations will be essential for advancing the practical implementation and generalizability of behaviorally enhanced microgrid management strategies.

Overall, this research makes important contributions to the emerging field of socially enhanced microgrid optimization. It bridges the gap between engineering-driven energy management and behaviorally informed demand response, showing that the integration of gamification into formal optimization processes can yield substantial benefits. By combining advanced multi-objective evolutionary algorithms with behavioral modeling, the proposed approach offers a practical and flexible framework for future residential microgrids facing increasing renewable penetration and growing user-centric operational requirements. This work also opens several promising directions for future research, including the integration of real-time behavioral sensing data, more sophisticated game mechanics such as team-based competitions, and the extension to multi-energy systems where heat and transportation loads are co-optimized alongside electricity. As microgrids evolve toward more decentralized, socially active, and prosumer-driven configurations, this research lays a strong foundation for socially enhanced, behaviorally responsive, and economically efficient energy management strategies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to conflict of interest but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Doan, S., Yeh, H. & Yang, Y. Two-mode adaptive schemes for VAR control with solar power and energy storage. IEEE Syst. J. 14(1), 889–899. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2019.2920016 (2020).

Lekavičius, J. & Gružauskas, V. Data augmentation with generative adversarial network for solar panel segmentation from remote sensing images. Energies 17, 3204. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17133204 (2024).

Ghanbari-Ghalehjoughi, M., Taghizad-Tavana, K. & Nojavan, S. Resilient operation of the renewable energy and battery energy storages based smart distribution grid considering physical-cyber-attacks. J. Energy Stor. 62, 106950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.106950 (2023) (2023/06/01/).

Feng, C., Shao, L., Wang, J., Zhang, Y. & Wen, F. Short-term load forecasting of distribution transformer supply zones based on federated model-agnostic meta learning. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2024.3393017 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Two stage stochastic energy scheduling for multi energy rural microgrids with irrigation systems and biomass fermentation. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2024.3483444 (2024).

Hu, Z., Su, R., Zhang, K., Wang, R. & Ma, R. Resilient frequency estimation for renewable power generation against phasor measurement unit and communication link failures. IEEE Trans. Circ. Syst. II Exp. Briefs 72(1), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2024.3496192 (2025).

Shang, Y., Li, D., Li, Y. & Li, S. Explainable spatiotemporal multi-task learning for electric vehicle charging demand prediction. Appl. Energy 384, 125460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2025.125460 (2025) (2025/04/15/).

Zhao, A. P. et al. Electric vehicle charging planning: A complex systems perspective. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 16(1), 754–772. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2024.3446859 (2025).

Zhao, P. et al. A social computing method for energy safety. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnlssr.2023.12.001 (2024).

Li, S., Gu, C., Zhao, P. & Cheng, S. Adaptive energy management for hybrid power system considering fuel economy and battery longevity. Energy Convers. Manag. 235, 114004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114004 (2021).

Hemmati, M., Bayati, N. & Ebel, T. Integrated optimal energy management of multi-microgrid network considering energy performance index: global chance-constrained programming framework. Energies 17, 4367. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17174367 (2024).

Yan, B., Yao, P., Yang, T., Zhou, B. & Yang, Q. Game-theoretical model for dynamic defense resource allocation in cyber-physical power systems under distributed denial of service attacks. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 12, 41–51 (2023).

Zhang, H., Yue, D., Dou, C. & Hancke, G. P. Two-layered hierarchical optimization strategy with distributed potential game for interconnected hybrid energy systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCYB.2022.3142035 (2022).

Oroojlooyjadid, A., Nazari, M., Snyder, L. V. & Takač, M. A deep Q-network for the beer game: Deep reinforcement learning for inventory optimization. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 24(1), 285–304 (2022).

Lee, M. Recent advances in generative adversarial networks for gene expression data: A comprehensive review. Mathematics 11, 3055. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11143055 (2023).

Singh, M. K., Choudhary, A., Gulia, S. & Verma, A. Multi-objective NSGA-II optimization framework for UAV path planning in an UAV-assisted WSN. J. Supercomput. 79(1), 832–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-022-04701-2 (2023) (2023/01/01).

Jain, S. & Dubey, K. K. Employing the Latin hypercube sampling to improve the NSGA III performance in multiple-objective optimization. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 24(8), 3319–3330 (2023).

Urishev, B. Decentralized energy systems, based on renewable energy sources. Appl. Solar Energy 55, 207–212 (2019).

Cicilio, P. et al. Resilience in an evolving electrical grid. Energies https://doi.org/10.3390/en14030694 (2021).

Yenugula, M., Sahoo, S. & Goswami, S. Cloud computing for sustainable development: An analysis of environmental, economic and social benefits. J. Fut. Sustain. 4(1), 59–66 (2024).

Preuss, N. & You, F. Consequential versus attributional life cycle optimization of poultry manure management technologies in a food-energy-water-waste nexus. J. Clean. Prod. 469, 143133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143133 (2024) (2024/09/01/).

Frieden, F., Leker, J. & von Delft, S. A multi-objective analysis of grid-connected local renewable energy systems for industrial SMEs. J. Energy Stor. 98, 113033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.113033 (2024) (2024/09/20/).

Nikoobakht, A., Aghaei, J., Shafie-khah, M. & Catalão, J. P. S. Continuous-time co-operation of integrated electricity and natural gas systems with responsive demands under wind power generation uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2020.2968152 (2020).

Funding

This work is supported by the Science and Technology Project of the China Southern Power Grid (031000QQ00220016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yao DUAN: Conceptualization, methodology design, and simulation. Yao DUAN contributed to the overall modeling framework and carried out system simulations. Chong GAO: Project supervision, theoretical development, and manuscript review. Chong GAO led the project, guided the theoretical framework, and reviewed the final manuscript. Junxiao ZHANG: Software development and data processing. Junxiao ZHANG was responsible for developing the computational tools and processing experimental data. Yaxiong WU: Literature review and validation. Yaxiong WU conducted the literature analysis and validated the model with empirical data. Shucan ZHOU: Visualization and figure preparation. Shucan ZHOU created the graphical representations of results and helped improve visual clarity. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, Y., Gao, C., Zhang, J. et al. Multi-objective optimization of gamified demand response for PV-integrated microgrids: a novel NSGA-III framework with behavioral adaptation modeling. Sci Rep 15, 34022 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13904-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13904-5