Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is responsible for more than 80% of cases of dementia in senior individuals globally. In the current study, the role of modulation of the FGF1/PI3K/Akt pathway in the protective effect of tozasertib was evaluated. Experimental dementia was induced in mice by injecting streptozotocin (STZ) intracerebroventricularly. Various biochemical parameters for oxidative stress & lipid peroxidation (SOD, GSH, catalase, TBARS), neuroinflammation (MPO, IL-6, IL-1 β, TNF-α, NFκB), apoptotic markers (Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3), and memory parameters (AChE activity, β1–40 levels) were assessed. The behavioral parameters evaluated included the Morris Water Maze test and the step-down passive avoidance test. Histological changes were assessed using H&E staining. ICV STZ-induced AD resulted in increased oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, neuroinflammation, apoptosis, and decreased learning and memory. The results showed that administration of tozasertib improved memory, decreased levels of oxidative stress, inflammatory parameters, and apoptotic markers, and improved histological parameters in a dose-dependent manner. Pre-administration of LY294002, a PI3K/Akt pathway inhibitor, partially reversed the protective effects of Tozasertib, suggesting possible involvement of this pathway. However, as the mechanism was inferred primarily through pharmacological antagonism, further studies including direct molecular assessments (e.g. p-Akt/t-Akt) are warranted to confirm the role of FGF1/PI3K/Akt signaling in Tozasertib’s action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), responsible for over 80% of dementia cases in older adults worldwide, leads to a progressive decline in cognitive, behavioral, and learning functions1.

The pathogenesis of AD involves amyloid-β (Aβ) accumulation, tau hyperphosphorylation, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and eventual neuronal death2,3. Despite the availability of symptomatic treatments such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (Donepezil, Rivastigmine, Galantamine) and NMDA receptor antagonists (Memantine), no current therapy effectively halts or reverses disease progression4.

Due to the complex etiology of AD, there is a need to explore the disease modifying targets. The FGF1/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway has been explored in regulation of neuronal survival, synaptic plasticity, and glucose metabolism, all of which are disrupted in AD5,6,7,8,9. It has been reported that in AD, there is dysregulation of the PI3K subunits and the phosphorylation of Akt is decreased often in association with Aβ and tau pathology12. Fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) is the upstream regulator of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and is also implicated in neuroprotection and cellular resilience, making this signaling axis a compelling target to be explored in AD10,11,13.

Tozasertib (also known as VX-680 or MK-0457) is a potent pan-Aurora kinase inhibitor originally developed for oncology, but its demonstrated ability to cross the blood–brain barrier makes it a promising candidate for central nervous system (CNS) applications. Aurora kinases, particularly Aurora A, play key roles in cell cycle regulation, and their dysregulation has been increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Aberrant activation of Aurora A has been linked to tau hyperphosphorylation and synaptic dysfunction—central features of AD pathology. Recent studies have also suggested potential crosstalk between Aurora kinase signaling and the PI3K/Akt pathway, a critical regulator of neuronal survival and plasticity14. Inhibiting Aurora kinases may therefore confer neuroprotection by both attenuating tau-related pathology and restoring intracellular signaling balance15. These properties, together with its brain penetrance and capacity to target multiple disease-relevant mechanisms, provide a strong rationale for repurposing tozasertib in the context of AD.

Given these insights, the present study was designed to evaluate the neuroprotective effect of Tozasertib in a streptozotocin (STZ)-induced mouse model of sporadic AD. We hypothesized that Tozasertib would ameliorate cognitive deficits, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation, and that these effects would be mediated via the FGF1/PI3K/Akt pathway. To test this, we also examined the impact of LY294002, a specific PI3K inhibitor, on Tozasertib’s efficacy.

Materials and methods

All the reagents employed in this study were of analytical grade. STZ (streptozotocin) (Cat no. 18883-66-4; SRL Lab.); Tozasertib (Cat No. SML2158; Sigma Aldrich); Donepezil (Cat No. 120011-70-3; TCI Chemicals); Thiobarbituric acid (Cat No. 504-17-6; Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd.); 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane (Cat No. 1001609417; Sigma Aldrich); 5,5-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (Cat No. 69-78-3; Sigma Aldrich); Reduced glutathione (Cat No. 7018-8; Molychem); NBT (nitrobluetetrazolium) (Cat No. 298-83-9; Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd.); IL1-β (Cat No. KB3063; Krishgen Biosystem); IL-6 (Cat No. KB2068; Krishgen Biosystem); TNF-α (Cat No. E0117Mo; BT Lab); NFκB (Cat No. K-02-2879; Kinesis Dx).

Streptozotocin (STZ) was dissolved in freshly prepared artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) and administered intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.) at a dose of 3 mg/kg9. Donepezil was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at a dose of 3 mg/kg, as per established protocols9. Tozasertib was solubilized in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and administered i.p. at doses of 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg55,56. LY-294,002, a PI3K inhibitor, was prepared in 10% DMSO and administered i.p. at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg54. Pilot studies confirmed tolerability of all treatments, with no observable weight loss or signs of toxicity.

Animals

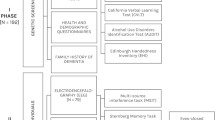

Swiss albino male mice (aged about 16 weeks old and weight 28 ± 2 g) bred in the Chitkara College of Pharmacy, Rajpura, India were employed for the study. The animals were acclimatized for at least a week before initiating the experiments. The mice were housed in polypropylene cages with sterile corn cob bedding (changed twice weekly), had free access to standard rodent chow (Ashirwad Industries, Mohali, India; composition: 22% protein, 5% fat, 4% fiber) and filtered water. The animal housing conditions were maintained at 22 ± 2 °C, 50–60% humidity, and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Environmental enrichment included PVC tunnels and nesting material. Experiments were performed in a semi-soundproof laboratory during the light phase. The animal protocol was approved by IAEC via approval number IAEC/CCP/22/01/PR-10; and experiments was conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines, with all procedures approved by the Committee for Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CCSEA), Government of India, and performed in compliance with all relevant institutional and national regulations.

Mice were randomly divided into 7 groups each consisting of 8 animals (i.e. 7*8 = 56 mice). The sample size of n = 8 mice per group was determined a priori based on our review of previously published studies utilizing the streptozotocin-induced Alzheimer’s model, which showed that this group size is sufficient to detect statistically significant differences between groups16. To confirm the adequacy of this sample size, a post-hoc power analysis was performed using G*Power 3.1 on data from our primary outcome (escape latency in the MWM test). This analysis confirmed that our study was sufficiently powered (> 80%) to detect significant differences (α = 0.05, two-tailed) between treatment groups. Two observers, blind to the treatment schedule, simultaneously observed each animal for all the behavioral assessments, and the mean value obtained by both observers was recorded as data in the study.

Induction of dementia

Dementia was developed experimentally in mice by bilateral intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of STZ [3 mg/kg in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF), pH 7.4] in two doses, on the first and third days8 using a stereotaxic apparatus (ROLEX, India) under mild anesthesia induced by intraperitoneal administration of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). The injection site was localized using the following stereotaxic coordinates from the bregma: anteroposterior (AP) − 0.8 mm, mediolateral (ML) ± 1.5 mm, and dorsoventral (DV) − 3.5 mm, based on the Paxinos and Franklin mouse brain atlas.

A volume of 5 µL was injected slowly over 5 min using a Hamilton microsyringe. The needle was left in place for an additional 2 min to prevent reflux. Following the injection, animals were monitored continuously during recovery and then daily for 72 h for any signs of discomfort, distress, or infection. No surgical incision was performed. Analgesics were not required due to the minimally invasive nature of the injection. The control group mice received bilateral i.c.v. injections (10 µl) of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF, pH 7.4; composition: 126 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.2 mM NaH₂PO₄, 1.3 mM MgCl₂, 2.4 mM CaCl₂, 25 mM NaHCO₃, and 10 mM glucose)9.

Memory evaluation

Morris water maze (MWM)

The Morris water maze (MWM) test was employed to assess the spatial memory performance in mice16,17. MWM consisted of large circular pool (150 cm in diameter, 45 cm in height, filled to a depth of 30 cm with water at 28 ± 1° C). The water was made opaque with non-toxic white coloured dye. The pool would be divided into four equal hypothetical quadrants with the help of two threads, fixed at right angle to each other on the rim of the pool. A submerged platform (10 cm2), painted white was placed in target quadrant 1 cm below surface of water so as to provide escape area. The position of the platform, extra-maze cues, observer location, and other objects in the testing room were kept constant throughout the training sessions to avoid introducing variability in spatial navigation17.

Memory acquisition trial

The mice were subjected to four training trials in a day, from Day19 to day 22 for evaluation of memory acquisition. Every time the trials were performed, the starting quadrant was changed. Quadrant Q4 served as the target quadrant for the trials performed. Escape latency time (ELT) measured on day 22 is considered as a measure of acquisition or learning7.

Memory retrieval trial

On Day 23, the mice were given 120 s to explore the maze, while the platform was removed. The time spent in search of missing platform in 3 quadrants (Q1, Q2 and Q3) and the target quadrant Q4 was noted. The time spent in target quadrant Q4 were taken as retrieval of memory7.

Step down passive-avoidance task

The step-down passive avoidance apparatus consisted of a rectangular box (50 × 50 cm) with a grid floor delivering a 1.5 mA, 50 Hz electric shock for 1 s upon descent. A shock-free wooden platform (5 × 12 cm) was centered 3 cm above the grid. Mice were acclimatized to the apparatus for 10 s before training. During training (day 22), each mouse was placed on the platform, and the step-down latency (SDL; time to descend with all paws onto the grid) was recorded. Upon stepping down, a 1.5 mA shock (36 V, 50 Hz) was delivered for 1 s. After 24 h (day 23), retention was tested by re-placing the mouse on the platform and measuring SDL (cut-off: 120 s). Increased SDL during retention indicated memory retrieval18.

Biochemical estimations

After evaluating behaviour parameters on day 23, mice were euthanized through receiving an i.p. injection of urethane (25% in a dose of 1.6 g/kg) and were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Whole brains were dissected and homogenized in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 10% w/v) using homogenizer and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min to obtain clear supernatant. The clear supernatant and pellet were then used for different biochemical estimations. Intact brain specimens were kept in Bouin’s solution for histopathological investigation9. Bouin’s fixative was selected for its superior ability to preserve cytoplasmic and nuclear details in the specific tissues examined. Pilot experiments confirmed that Bouin’s provided optimal histological clarity for our endpoints without compromising structural integrity. Fixation time was carefully controlled to minimize over-hardening9.

Estimation of oxidative stress

Oxidative stress in mice was evaluated in terms of thiobarbituric reactive acid substance (TBARS) levels (marker of lipid peroxidation)19 reduced glutathione (GSH) level20, superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity21 and catalase activity22.

Estimation of brain pro-inflammatory markers

The inflammation levels in brain were assessed in terms of various pro-inflammatory markers such as Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity23 by using an ELISA assay. The enzyme linked immunosorbent assay kits were used and assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Estimation of brain apoptotic markers

The apoptosis in brain was assessed in terms of apoptotic markers such as Bax, Bcl-2 and Caspase324 by using an ELISA assay. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Estimation of brain acetylcholinesterase activity

The brain acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity was estimated using the technique of Ellman et al.25.

Estimation of levels of β1–40

The brain tissue homogenate obtained was used to measure the levels of β1–40 by using an ELISA assay. The enzyme linked immunosorbent assay kits were used and assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Histological examination of brain tissues using HE staining

Mice brains were removed and preserved in Bouin’s solution9. The brains were then removed and kept overnight in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 degree C before being embedded in paraffin. Sections of the brains, 5 ɥm thick, were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining, and photographed using a light microscope (at magnification ×400)26. Hippocampal neuronal counts were performed by two blinded investigators using ImageJ software on three non-overlapping fields (400× magnification) from H & E-stained sections. Cells were identified by morphological criteria (pyramidal shape, visible nucleoli). Data expressed as cells/mm² ± SD.

Drugs and treatment schedule

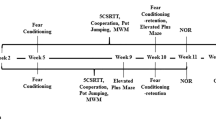

The animals were randomly divided into 7 groups (Fig. 1):

Group 1. Control animals received bilateral icv injection of ACSF on day 1 and day 3.

Group 2. ICV-STZ group received bilateral icv injection of STZ 3 mg/kg on day1 and day 3.

Groups 3,4 ICV-STZ mice were administered with Tozasertib (5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg; i.p.) respectively for 21 days (starting from 3rd day).

Group 5. ICV-STZ mice were administered with PI3K inhibitor (LY-294002, i.p.) per se for 21 days (starting from 3rd day).

Group 6. ICV-STZ mice were administered with PI3K inhibitor (LY-294002) and Tozasertib (10 mg/kg) for 21 days (starting from 3rd day).

Group 7. ICV-STZ mice were administered donepezil (3 mg/kg; i.p.) as standard for 21 days (starting from 3rd day).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Software, USA). Prior to analysis, all data were tested for the assumptions of parametric testing. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene’s test. The data were found to be normally distributed (p > 0.05) and showed homogeneity of variances. Given that the assumptions were met, parametric tests were applied. Parametric data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with repeated measures for Morris Water Maze data (with treatment and day as independent factors) and one-way ANOVA for all other endpoint measurements. Tukey’s post hoc test was applied for multiple comparisons in both cases. The significance threshold was established at p < 0.05 for all analyses. Behavioral time-course data were analyzed using repeated measures to account for within-subject correlations. No missing data occurred in this study. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise noted.

Results

Effect of Tozasertib on ICV STZ-induced impairment of memory using Morris water maze test

Normal and vehicle control group animals showed reduction on day 4 mean escape latency (MEL) as compared with their day 1 MEL during the training trials. Administration of Tozasertib (5 and 10 mg/kg) for 21 consecutive days caused reduction of day 4 MEL as compared with normal control group (Fig. 2). However, intracerebroventricular administration of STZ prevented the reduction of day 4 MEL as compared with day 1 MEL. Tozasertib treatment in both doses (5 and 10 mg/kg) caused significant reduction of day 4 MEL in ICV STZ treated mice. Donepezil-treated groups reflected considerably shortened day 4 MEL in the MWM test.

There is significant decrease in time spent in target quadrant in ICV STZ group as compared to normal control. Tozasertib (5 and 10 mg/kg) prevented the ICV STZ-induced decrease in time spent in target quadrant. PI3K inhibitor (LY-294002, i.p.) per se has no significant effect on STZ alteration on memory retrieval (Fig. 3). However, administration of PI3K inhibitor (LY-294002, i.p.) with Tozaseritib in ICV STZ mice abolished the effect of Tozasertib.

The effect of tozasertib on spatial memory and learning, measured by escape latency (ELT) in the MWM test. Tozasertib treatment significantly reduced the ELT, indicating improvements in memory and cognitive function. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 8) and analyzed by two way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ap < 0.0001 vs. Day 1 ELT in respective group. bp < 0.0001 vs. Day 4 ELT in vehicle control group. cp < 0.0001 vs. Day 4 ELT in STZ group, dp<0.0001 vs. Day 4 ELT of tozasertib 10 + STZ group.

Influence of tozasertib on time spent in target quadrant in Morris Water Maze. This figure presents the effect of tozasertib on spatial memory and learning, measured by time spent in the target quadrant (TSTQ) in the MWM test. Tozasertib treatment significantly increased the TSTQ, indicating improvements in memory and cognitive function. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 8) and analysed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ap<0.0001 vs. q1, q2 and q3 of vehicle control; bp<0.0001 vs. q4 of vehicle control; cp<0.0001 vs. q4 of STZ group; dp<0.0001 vs. q4 of tozasertib 10 + STZ group.

Effect of Tozasertib on ICV STZ-induced impairment of memory using step-down test

During the learning trial, the latency did not vary among the groups that indicated mice had similar responses to the testing environments and electric shocks. Retention test performed 24 h later demonstrated that intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of STZ induces a significant reduction in the avoidance latency and increase in the number of errors as well as a significant increase in the step-down percentage of mice from the platform (Fig. 4). Administration of Tozasertib and Donepezil significantly improved the Step down latency in ICV STZ in mice. Administration of PI3K inhibitor (LY294002, i.p.) in ICV STZ + Tozasertib group, resulted in decreased step down latency; however no per se effect was seen with LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor).

The effect of Tozasertib on memory retention, measured by latency time in the passive avoidance task. Tozasertib treatment significantly and dose-dependently increased the latency time, suggesting improved memory function. Values are shown as mean ± S.D (n = 6) and tested using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ****p < 0.0001, ns not significant. F (6, 35) = 435.1, P < 0.0001.

Effect of Tozasertib on acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity

In the present study, ICV STZ resulted in increase in the AChE activity in brain as compared to the control rats. On the other hand, Tozasertib (5 and 10 mg/kg) and Donepezil (3 mg/kg) prevented the increase in AChE activity in the brain, compared with ICV STZ group (Fig. 5). Administration of PI3K inhibitor (LY-294002) in ICV STZ group reversed this beneficial effect of Tozasertib; whereas, PI3K inhibitor per se administered with ICV STZ produced no difference.

The effect of Tozasertib on memory using AChE activity assessment. Tozasertib treatment significantly and dose-dependently decreased AChE activity resulting in improved memory function. Values are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 6) and analyzed using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ****p < 0.0001, ns not significant. F (6, 35) = 267.2, P < 0.0001.

Influence of Tozasertib on oxidative dysfunction

In the present study, ICV STZ treatment led to an increase in oxidative stress, evidenced by a significant rise in thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) levels, and a decrease in glutathione (GSH), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase levels, compared to the vehicle group (Fig. 6). However, the administration of Tozasertib/Donepezil attenuated the increase in brain TBARS level and decline in GSH, SOD, and catalase levels caused by STZ administration (Fig. 6). Administration of the PI3K inhibitor (LY-294002) in ICV STZ group reversed the beneficial effect of Tozasertib; whereas, the PI3K inhibitor per se administered with ICV STZ produced no significant difference.

The effect of Tozasertib on key markers of oxidative stress in animals. Tozasertib treatment significantly reduced TBARS (A), indicating reduced lipid peroxidation, and significantly increased antioxidant markers including GSH (B), SOD (C), and catalase (D), suggesting an antioxidative effect. Values are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 6) and analyzed using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. **p < 0.005, ****p < 0.0001, ns not significant. TBARS: F (6, 35) = 162.5, P < 0.0001; GSH: F (6, 35) = 78.89, P < 0.0001; SOD: F (6, 35) = 213, P < 0.0001; Catalase: F (6, 35) = 177.7, P < 0.0001.

Effect of Tozasertib on brain pro-inflammatory markers

In the present study, ICV STZ resulted in increase in inflammatory markers, evidenced by a significant rise in the TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, NF-κB and MPO activity compared to the vehicle group (Fig. 7). However, administration of Tozasertib/Donepezil counteracted the STZ-mediated increase in brain TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, NF-κB and MPO activity (Fig. 7). Administration of PI3K inhibitor (LY-294002) in ICV STZ group reversed this beneficial effect of Tozasertib; whereas, PI3K inhibitor per se administered with ICV STZ produced no significant difference.

The effect of Tozasertib on pro-inflammatory cytokines and NF-κB, markers of neuroinflammation, in mice. Tozasertib treatment significantly decreased the levels of TNF-α (A), IL-6 (B), IL-1β (C), NF-κB (D), and MPO (E) suggesting its potential to attenuate neuroinflammation.Values are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 6) and analyzed using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005, ****p < 0.0001, ns not significant. TNF- α: F (6, 35) = 192.3, P < 0.0001, IL-6: F (6, 35) = 191.3, P < 0.0001; IL-1b: F (6, 35) = 186.8, P < 0.0001; NF-κB: F (6, 35) = 133.5, P < 0.0001; MPO: F (6, 35) = 212.1, P < 0.0001.

Effect of Tozasertib on apoptotic markers

In the present study, ICV STZ treatment led to an increase in apoptosis, evidenced by a significant rise in the levels of Bax and Caspase-3, and a decrease in Bcl-2 levels, compared to the vehicle group (Fig. 8). However, the administration of Tozasertib and Donepezil mitigated the elevation in Bax and Caspase-3 level and decline in Bcl-2 levels associated with STZ exposure (Fig. 8). Administration of the PI3K inhibitor (LY-294002) in ICV STZ group reversed the beneficial effect of Tozasertib; whereas, the PI3K inhibitor per se administered with ICV STZ produced no significant difference.

The effect of Tozasertib on apoptotic markers. Tozasertib treatment significantly modify the levels of Bax (A), Bcl-2 (B), and Caspase3 (C), suggesting its potential to attenuate apoptosis. Values are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 6) and analyzed using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.0005, ****p < 0.0001, ns not significant. Bax: F (6, 35) = 21.81, P < 0.0001; Bcl-2: F (6, 35) = 19.69, P < 0.0001; Caspase-3: F (6, 35) = 55.89, P < 0.0001.

Effect of Tozasertib on brain tissue β1–40 levels

A marked elevation was noticed in the levels of β1–40 in ICV STZ-treated mice as compared with vehicle group (Fig. 9). However, administration of Tozasertib or Donepezil to ICV STZ treated mice attenuated the elevated levels of β1–40. Administration of PI3K inhibitor (LY-294002) in ICV STZ group reversed this beneficial effect of Tozasertib; whereas, PI3K inhibitor per se administered with ICV STZ produced no difference.

Effect of Tozasertib on β1–40 levels. Tozasertib treatment significantly decreased the levels of β1–40 suggesting its potential to attenuate dementia. Values are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 6) and analyzed using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ****p < 0.0001, ns not significant. F (6, 35) = 317.4, P < 0.0001.

Effect of Tozasertib on histopathological changes in the brain

The pathological alterations in the hippocampus were detected by hematoxylin-eosin (HE). Quantitative analysis revealed ICV STZ administration significantly reduced hippocampal neuronal cell count compared to vehicle control (Table 1). Tozasertib treatment dose-dependently improved neuronal survival as compared to ICV STZ animals. However, sections from mice administered with PI3K inhibitor along with Tozasertib and ICV STZ revealed neutrophilic infiltration, decrease in the number of pyramidal cells and deposits of amyloid plaques (Fig. 10; Table 1).

Histopathological alteration in various groups stained with H&E. Vehicle control group showed normal neuronal morphology, intact pyramidal cells and no neutrophilic infiltration. The STZ group showed reduced neuronal density and neutrophilic infiltration (indicated by arrows). The Donepezil group showed mild pyramidal cell loss. Tozasertib-treated groups showed preserved neuronal integrity of brain, suggesting a neuroprotective effect. PI3K inhibitor co-treated groups showed prominent neutrophilic inflammation and severe neuronal loss.

Discussion

Recent therapeutic reviews have reported the pivotal role of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis and its potential as a therapeutic target62,63. This pathway is integral to neuronal survival, synaptic plasticity, and the regulation of tau phosphorylation and amyloid-beta (Aβ) aggregation63. Dysregulation of PI3K/Akt signaling has been linked to increased oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and impaired autophagy in AD models64. Parallel to this, kinase-directed drug repurposing has emerged as a promising strategy in AD therapeutics. Aurora kinases, particularly Aurora A, have been implicated in tau hyperphosphorylation and synaptic dysfunction, both hallmark features of AD65. Inhibitors targeting these kinases, such as Tozasertib, originally developed for oncology, have demonstrated potential neuroprotective effects by modulating key signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt66. Tozasertib, a pan-Aurora kinase inhibitor originally developed for oncology, exhibits blood–brain barrier permeability and multi-targeted effects, including modulation of PI3K/Akt signaling—making it a candidate for repurposing in AD66.

In this current study, we evaluated the role of the FGF1/PI3K/Akt pathway in the neuroprotective effect of tozasertib (5 and 10 mg/kg i.p.) in a streptozotocin-induced Alzheimer’s mouse model. The results demonstrated improved cognitive performance, reduced oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation alongside histological improvements, suggesting that the neuroprotective and cognitive-preserving effects of ttozasertib confer neuroprotection, likely via the FGF1/PI3K/Akt signaling axis.

A typical animal model of AD has been established by administering the beta-cytotoxic drug streptozotocin intracerebroventricularly (STZ-i.c.v.). The ICV STZ-administered mice develop impairment of memory, advanced cholinergic discrepancies, hypometabolism of glucose in the brain, and oxidative stress, along with degeneration of neurons that leads to AD, which is associated with aggregated Aβ plaques, tau protein, and Aβ deposits. Hence, in this current study, the ICV STZ-induced AD rodent model was employed.

Anticholinesterase (AChE) hyperactivity, observed in AD, depletes neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh), impairing neurotransmission and cognition30,31,32. Tozasertib, in current, significantly attenuated AChE activity, which suggests the potential protective effect on cholinergic signaling. The observed memory improvements were assessed using MWM and step-down passive-avoidance tasks, which reflect the protective effect of tozasertib through decreased oxidative stress and neuroinflammation on the hippocampus33,34.

Oxidative stress, triggered by a disparity between overproduction and build-up of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells as well as tissues, contributes to lipid peroxidation, DNA damage, and neuronal dysfunction in AD, which is the result of dysfunction of synapses and leads to memory impairment35,36,37,38,39,40. Hence, in the present study, the ROS scavenger’s glutathione, superoxide dismutase, and catalase activity, as well as TBARS levels, were estimated to evaluate the antioxidant activity as well as lipid peroxidation. Tozasertib improved antioxidant status, increasing GSH, SOD, and catalase levels and reducing TBARS, aligning with PI3K/Akt-mediated Nrf2 activation reported previously63,67,68.

Inflammation is the major contributor to AD’s development and exacerbation. In the brains of individuals with AD, pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and NF-κB) and MPO, a marker of leukocyte infiltration levels, were upregulated. That resulted in the buildup of Aβ plaque aggregates as well as tau phosphorylation, causing neuronal loss41,42. Hence, we studied inflammatory parameters including TNF-α, IL-1β, NF-κβ, and IL-6, as well as MPO. Tozasertib treatment significantly reduced these pro-inflammatory markers, consistent with PI3K/Akt activation suppressing NF-κB and promoting microglial polarization69,70,71.

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, plays a critical role in the progression of dementia, particularly in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders where excessive neuronal loss accelerates cognitive decline43. In dementia models like ICV STZ-induced dementia, neurodegeneration is partly driven by heightened apoptotic activity, contributing to memory impairment and synaptic dysfunction44. Apoptosis is tightly regulated by a balance between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins, among which caspase-3, Bax, and Bcl-2 are key mediators. Caspase-3, a critical executioner enzyme often associated with increased neuronal apoptosis in dementia, orchestrates the dismantling of cellular components, leading to cell death and making it a reliable marker of apoptotic progression in neurodegenerative models45. Bax, a pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 protein family, promotes mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), facilitating the release of cytochrome-c, which subsequently activates caspase-346. Thus, Bax acts as an upstream regulator that signals caspase-3 activation, pushing cells towards apoptosis47. On the other hand, Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein, counters Bax’s effects by stabilizing the mitochondrial membrane, thereby preventing the release of apoptotic factors and inhibiting caspase activation. Together, the interplay between Bax and Bcl-2 dictates whether a cell undergoes apoptosis, positioning them as crucial markers for evaluating neuroprotection in dementia models48. Tozasertib reduced pro-apoptotic markers (Bax, caspase-3) and increased anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, reflecting activation of survival pathways via PI3K/Akt and FGF1 signaling. These changes suggest Tozasertib may support neuronal integrity by modulating mitochondrial apoptosis cascades.

In the present study, Tozasertib exhibited robust neuroprotective effects in the streptozotocin-induced Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mouse model. The use of LY294002, a PI3K/Akt pathway inhibitor, partially reversed these effects, suggesting a possible involvement of the FGF1/PI3K/Akt signaling axis. One of the hallmark findings was the significant attenuation of oxidative stress markers, including malondialdehyde (MDA), and restoration of antioxidant defenses such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) following Tozasertib administration. Oxidative stress is a central contributor to STZ-induced neurodegeneration, and previous studies have shown that activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway confers antioxidative effects by upregulating Nrf2-mediated transcriptional activity and reducing mitochondrial ROS production63,67,68. The protective antioxidant profile observed in our study is thus consistent with the involvement of this pathway.

Tozasertib also markedly decreased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which are typically elevated in STZ-induced neuroinflammation. Inflammation-driven neurodegeneration has been linked to PI3K/Akt-mediated modulation of NF-κB activity and microglial polarization69,70. The observed anti-inflammatory profile may be attributed to FGF1-stimulated activation of the PI3K/Akt axis, which is known to suppress pro-inflammatory transcription factors and promote neuronal survival71.

Moreover, tozasertib significantly mitigated apoptotic cell death, as evidenced by reduced Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and caspase-3 activity. The anti-apoptotic role of PI3K/Akt signaling is well-documented, particularly through the phosphorylation and inactivation of pro-apoptotic factors and enhancement of cell survival proteins72,73. FGF1 has similarly been implicated in preventing apoptosis in neurotoxic models via Akt phosphorylation74. Our data suggest that tozasertib may influence pathways associated with FGF1 signaling, potentially contributing to neuronal viability by modulating intrinsic apoptotic mechanisms.

In line with characteristic cholinergic deficits seen in AD, we noted elevated brain acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in STZ-treated animals, which was significantly normalized by Tozasertib. The PI3K/Akt pathway is known to preserve cholinergic neurons and maintain synaptic function, partly through regulation of CREB and BDNF signaling75. Therefore, the AChE-normalizing effect of Tozasertib may partly reflect an upstream modulatory action through FGF1-mediated PI3K/Akt activation.

Finally, a notable reduction in amyloid β1–40 (Aβ1–40) peptide levels was observed following Tozasertib treatment. Aβ accumulation is a primary pathological feature in AD, and its production and clearance are tightly regulated by PI3K/Akt signaling, which influences APP processing enzymes and autophagic flux76,77. The reduction of Aβ1–40 in our model further supports the hypothesis that tozasertib may have exerted its anti-amyloidogenic effects via the PI3K/Akt pathway.

The observed cognitive enhancements following Tozasertib administration are evidenced by improved performance in both the Morris Water Maze and Step-Down Passive Avoidance tests, which suggest a beneficial effect on spatial learning and memory. These effects may involve modulation of FGF1/PI3K/Akt signaling, a pathway known to influence neuroplasticity and memory function, although further direct molecular evidence is needed to substantiate this link78,79. Histological examination of hippocampal sections from Tozasertib-treated mice showed reduced neutrophilic infiltration, a higher preservation of pyramidal cells, and decreased amyloid plaque deposition compared to STZ-induced controls. These findings further underscore the therapeutic potential of Tozasertib, maybe through modulation of the FGF1/PI3K/Akt axis, in mitigating both functional and structural hallmarks of Alzheimer’s pathology80.

The PI3K/Akt pathway plays a pivotal role in promoting neuronal survival, synaptic plasticity, and resistance to oxidative stress—processes that are critically impaired in Alzheimer’s disease. Fibroblast Growth Factor 1 (FGF1) acts as an upstream regulator of this pathway, activating PI3K/Akt signaling through its receptor-mediated tyrosine kinase activity79. Given this relationship, evaluating the modulation of the FGF1/PI3K/Akt axis provides valuable insight into potential neuroprotective mechanisms. LY294002, a selective PI3K inhibitor, serves as a robust pharmacological tool to validate this pathway involvement; its ability to block downstream Akt activation enables mechanistic dissection of whether tozasertib’s neuroprotective effects are mediated via FGF1-induced PI3K/Akt signaling81,82. Therefore, combining tozasertib treatment with LY294002 co-administration offers a targeted approach to substantiate the hypothesis that tozasertib confers neuroprotection through the FGF1/PI3K/Akt pathway. Crucially, pre-administration of LY-294,002, a specific PI3K/Akt pathway inhibitor, significantly abrogated the neuroprotective effects of tozasertib across all tested parameters, underscoring the centrality of this signaling cascade in mediating its therapeutic actions.

This pharmacological blockade attenuated Tozasertib’s ability to reduce oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, cholinergic dysfunction, and Aβ accumulation, suggesting that its neuroprotective effects may be partially mediated through the FGF1/PI3K/Akt signaling axis.

This study primarily focused on the FGF1/PI3K/Akt signaling axis to elucidate the neuroprotective mechanism of Tozasertib; however, potential contributions from off-target effects, including Aurora kinase inhibition, were not systematically explored. Although the findings are promising, the multi-kinase nature of Tozasertib may have influenced additional pathways beyond the scope of the current investigation. Furthermore, while Tozasertib demonstrated strong efficacy at modest doses, its previously reported cardiotoxicity, myelosuppression, and limited data on brain penetrance warrant cautious interpretation of its translational potential83. Importantly, we did not assess systemic toxicity markers (e.g., body weight changes, serum ALT/AST, or creatinine levels), which would provide a more comprehensive safety profile. Although significant effects were observed, the relatively small sample size and absence of formal power analysis, along with the 23-day treatment duration, may limit the extrapolation of findings to long-term disease progression; however, these parameters provide a valuable foundation for designing future studies with extended timelines and larger cohorts to validate and expand upon the current outcomes.

Future studies should aim to dissect the individual roles of aurora kinase inhibition versus PI3K/Akt activation in mediating neuroprotection, employing selective inhibitors or genetic approaches. Investigations into the crosstalk between aurora kinases and PI3K/Akt pathways in neuronal survival and tau regulation are also warranted. Moreover, as the mechanistic link is primarily inferred through pharmacological blockade, additional studies using direct molecular markers like p-Akt/t-Akt are needed to substantiate the role of FGF1/PI3K/Akt signaling in Tozasertib’s action. Additionally, strategies such as low-dose optimization, structural analog design for enhanced CNS selectivity, and targeted drug delivery systems hold promise for improving Tozasertib’s therapeutic index. These avenues may facilitate the safe repurposing of kinase inhibitors for chronic neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

Conclusions

Tozasertib ameliorated ICV STZinduced cognitive impairment and associated oxidative, inflammatory, cholinergic, and apoptotic alterations. The attenuation of these effects by the PI3K inhibitor LY-294,002 suggests that its neuroprotective action involves PI3K/Akt signaling downstream of FGF1. To strengthen mechanistic insights, future studies should quantify phosphorylated Akt, evaluate downstream p-GSK-3β, and assess AURKA activity. Proteomic profiling of inflammatory and apoptotic markers is also needed. Validation in transgenic AD models and chronic toxicity assessment will be essential for advancing Tozasertib toward therapeutic application.

Data availability

Data is available with corresponding author upon request.

References

Tripathi, P., Shukla, P. & Bieberich, E. Theranostic applications of nanomaterials in alzheimer’s disease: A multifunctional approach. Curr. Pharm. Des. 28 (2), 116–132. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612827666211122153946 (2022).

Jansen, W. J. et al. Prevalence estimates of amyloid abnormality across the alzheimer disease clinical spectrum. JAMA Neurol. 79 (3)), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.5216 (2022).

Ajoolabady, A., Lindholm, D., Ren, J. & Pratico, D. ER stress and UPR in alzheimer’s disease: Mechanisms, pathogenesis, treatments. Cell Death Dis. 13 (8), 706. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-05153-5 (2022).

Passeri, E. et al. Alzheimer’s disease: Treatment strategies and their limitations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (22), 13954. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232213954 (2022).

Behl, T. et al. Role of monoamine oxidase activity in alzheimer’s disease: An insight into the therapeutic potential of inhibitors. Molecules (Basel Switzerland). 26 (12), 3724. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26123724 (2021a).

Kumar, M. & Bansal, N. Implications of phosphoinositide 3-Kinase-Akt (PI3K-Akt) pathway in the pathogenesis of alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 59 (1), 354–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-021-02611-7 (2022).

Kumar, A. & Singh, N. Inhibitor of Phosphodiestearse-4 improves memory deficits, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and neuropathological alterations in mouse models of dementia of alzheimer’s type. Biomed. Pharmacotherapy. 88, 698–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.059 (2017a).

Kumar, A. & Singh, N. Calcineurin inhibitors improve memory loss and neuropathological changes in mouse model of dementia. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 153, 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2016.12.018 (2017b).

Kumar, A. & Singh, N. Pharmacological activation of PKA improves memory loss and neuropathological changes in mouse model of dementia of alzheimer’s type. BehavPharmacol 28 (2 and 3 - Special Issue), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1097/FBP.0000000000000294 (2017c).

Long, H. Z. et al. PI3K/AKT signal pathway: A target of natural products in the prevention and treatment of alzheimer’s disease and parkinson’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 648636. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.648636 (2021).

Razani, E. et al. The PI3K/Akt signaling axis in alzheimer’s disease: A valuable target to stimulate or suppress? Cell. Stress Chaperones. 26 (6), 871–887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12192-021-01231-3 (2021).

Zheng, M. & Wang, P. Role of insulin receptor substance-1 modulating PI3K/Akt insulin signaling pathway in alzheimer’s disease. 3 Biotech. 11 (4), 179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-021-02738-3 (2021).

Fang, Y., Ou, S., Wu, T., Zhou, L., Tang, H., Jiang, M. & Guo, K. Lycopene alleviates oxidative stress via the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2pathway in a cell model of Alzheimer’s disease. PeerJ, 8, e9308 (2020). https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9308.

Uniyal, A. et al. Tozasertib attenuates neuropathic pain by interfering with Aurora kinase and KIF11 mediated nociception. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 12 (11)), 1948–1960. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00043 (2021).

Yi, J. et al. Upregulation of the LncRNA MEG3 improves cognitive impairment, alleviates neuronal damage, and inhibits activation of astrocytes in hippocampus tissues in alzheimer’s disease through inactivating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 120 (10), 18053–18065. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.29108 (2019).

Mehta, V., Kumar, A., Jaggi, A. S. & Singh, N. Restoration of the attenuated neuroprotective effect of ischemic post-conditioning in diabetic mice by SGLT (Sodium dependent glucose co-transporters) inhibitor Phlorizin. Current Neurovascular Research., 17(5), 706–718. (2020). https://doi.org/10.2174/1567202617666201214112016

Rani, R., Kumar, A., Jaggi, A. S. & Singh, N. Pharmacological investigations on efficacy of Phlorizin a SGLT inhibitor in mouse model of intracerebroventricularstreptozotocin induced dementia of AD type. J. Basic ClinPhysiolPharmacol., 2020, 32(6), 1057–1064. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1515/jbcpp-2020-0330

Kameyama, T., Nabeshima, T. & Kozawa, T. Step-down-type passive avoidance- and escape-learning method. Suitability for experimental amnesia models. J. Pharmacol. Methods. 1986 (16(1)), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-5402(86)90027-6 (1986).

Okhawa, H., Ohishi, N. & Yagi, K. Assay of lipid peroxides in animal tissue by acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 95, 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3 (1979).

Boyne, A. F. & Ellman, G. L. A methodology for analysis of tissue sulfhahydral components. Anal. Biochem. 46 (2), 639–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(72)90335-1 (1972).

Misra, H. P. & Fridovich, I. The role of superoxide anion in the autoxidation of epinephrine and a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 247 (10), 3170–3175. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(19)45228-9 (1972).

Goth, L. A simple method for determination of serum catalase activity and revision of reference range. Clin. Chim. Acta. 196 (2-3), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-8981(91)90067-m (1991).

Grisham, M. B., Benoit, J. N. & Granger, D. N. Assessment of leukocyte involvement during ischemia and reperfusion of intestine. Methods Enzymol. 186, 729–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/0076-6879(90)86172-R (1990).

Cai, C. et al. Pgam5-mediated PHB2 dephosphorylation contributes to endotoxemia-induced myocardial dysfunction by inhibiting mitophagy and the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 19 (14), 4657–4671. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.85767 (2023).

Ellman, G. L., Courtney, K. D., Valentino, A. & Featherstone, R. M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 7, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9 (1961).

Banchroft, A. S. & Turner, D. R. Theory and practice of histological techniques eigth ed. Churchil Livingstone, New York, London, San Francisco, Tokyo, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/C2015-0-00143-5

Behl, T. et al. Multifaceted role of matrix metalloproteinases in neurodegenerative diseases: Pathophysiological and therapeutic perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (3), 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031413 (2021b).

Liu, S., Butler, C. A., Ayton, S., Reynolds, E. C. & Dashper, S. G. Porphyromonas gingivalis and the pathogenesis of alzheimer’s disease. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841X.2022.2163613 (2023).

Ashe, K. H. & Zahs, K. R. Probing the biology of alzheimer’s disease in mice. Neuron 66 (5), 631–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.031 (2010).

Dai, R., Sun, Y., Su, R. & Gao, H. Anti-Alzheimer’s disease potential of traditional Chinese medicinal herbs as inhibitors of BACE1 and ache enzymes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 154, 113576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113576 (2022).

Carvajal, F. J. & Inestrosa, N. C. Interactions of ache with Aβ aggregates in alzheimer’s brain: Therapeutic relevance of IDN 5706. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 4, 19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2011.00019 (2011).

Kumar, V., Saha, A. & Roy, K. In Silico modeling for dual Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) enzymes in alzheimer’s disease. Comput. Biol. Chem. 88, 107355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2020.107355 (2020).

Jahangiri, Z., Gholamnezhad, Z. & Hosseini, M. Neuroprotective effects of exercise in rodent models of memory deficit and alzheimer’s. Metab. Brain Dis. 34, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-018-0343-y (2019).

Kim, N. et al. Transplantation of gut microbiota derived from Alzheimer’s disease mouse model impairs memory function and neurogenesis in C57BL/6 mice. Brain Behav. Immunity, 98, 357–365 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.09.002

Ionescu-Tucker, A. & Cotman, C. W. Emerging roles of oxidative stress in brain aging and alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2021 (107), 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.07.014 (2021).

Cassidy, L. et al. Oxidative stress in alzheimer’s disease: A review on emergent natural polyphenolic therapeutics. Complement. Ther. Med. 49, 102294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102294 (2020).

Virk, D., Kumar, A., Jaggi, A. S. & Singh, N. Ameliorative role of rolipram, PDE-4 inhibitor, against sodium arsenite–induced vascular dementia in rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28 (44), 63250–63262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15189-3 (2021).

Kumar, A. & Singh, N. Calcineurin Inhibition and Protein Kinase A Activation Limits Cognitive Dysfunction and Histopathological Damage in a Model of Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type. Curr. Neurovascul. Res., 15(3), 234–245 (2018). https://doi.org/10.2174/1567202615666180813125125

Neha, Kumar, A., Jaggi, A. S., Sodhi, R. K. & Singh, N. Silymarin ameliorates memory deficits and neuropathological changes in high fat diet (HFD) induced dementia of Alzheimer’s type in mouse. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol., 387(8), 777– 87. 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-014-0990-4

Mehrabadi, S. & Sadr, S. S. Assessment of probiotics mixture on memory function, inflammation markers, and oxidative stress in an alzheimer’s disease model of rats. Iran. Biomed. J. 24 (4), 220. https://doi.org/10.29252/ibj.24.4.220 (2020).

Guerrero, A., De Strooper, B. & Arancibia-Cárcamo, I. L. Cellular senescence at the crossroads of inflammation and alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 44 (9), 714–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2021.06.007 (2021).

Irwin, M. R. & Vitiello, M. V. Implications of sleep disturbance and inflammation for alzheimer’s disease dementia. Lancet Neurol. 18 (3), 296–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30450-2 (2019).

Moujalled, D., Strasser, A. & Liddell, J. R. Molecular mechanisms of cell death in neurological diseases. Cell. Death Differ. 28, 2029–2044. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-021-00814-y (2021).

Xu, H. J. et al. Shen Qi Wan ameliorates learning and memory impairment induced by STZ in AD rats through PI3K/AKT pathway. Brain Sci. 12 (6), 758. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12060758 (2022).

Roth, K. A., Caspases, Apoptosis & Disease, A. Causation, correlation, and confusion. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 60 (9), 829–838. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/60.9.829 (2001).

Ola, M. S., Nawaz, M. & Ahsan, H. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins and caspases in the regulation of apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 351, 41–58 (2011).

Shore, G. C., Papa, F. R. & Oakes, S. A. Signaling cell death from the Endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23 (2), 143–149 (2011).

Siddiqui, W. A., Ahad, A. & Ahsan, H. The mystery of BCL2 family: Bcl-2 proteins and apoptosis: An update. Arch. Toxicol. 89, 289–317 (2015).

Mittal, A. et al. A Systematic Review of updated mechanistic insights towards Alzheimer’s disease. CNS & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders) (2023). https://doi.org/10.2174/1871527321666220510144127

Arranz, A. M. & De Strooper, B. The role of astroglia in alzheimer’s disease: Pathophysiology and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 18 (4), 406–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30490-3 (2019).

Guo, T., Korman, D., Baker, S. L., Landau, S. M. & Jagust, W. J. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Longitudinal cognitive and biomarker measurements support a unidirectional pathway in alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. Biol. Psychiatry. 89 (8), 786–794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.06.029 (2021).

Abeysinghe, A. A. D. T., Deshapriya, R. D. U. S. & Udawatte, C. Alzheimer’s disease; A review of the pathophysiological basis and therapeutic interventions. Life Sci. 256, 117996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117996 (2020).

Kumar, A., Kumar, A., Jaggi, A. S. & Singh, N. Efficacy of cilostazol a selective phosphodiesterase-3 inhibitor in rat model of streptozotocin diabetes induced vascular dementia. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 135, 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2015.05.006 (2015).

Grewal, A. K., Singh, N. & Singh, T. G. Neuroprotective effect of Pharmacological postconditioning on cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion-induced injury in mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 71 (6), 956–970. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphp.13073 (2019).

Uniyal, A., Gadepalli, A., Modi, A. & Tiwari, V. Modulation of KIF17/NR2B crosstalk by Tozasertib attenuates inflammatory pain in rats. Inflammopharmacology 30 (2), 549–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-022-00948-6 (2022).

Yin, C., Huang, G. F., Sun, X. C., Guo, Z. & Zhang, J. H. Tozasertib attenuates neuronal apoptosis via DLK/JIP3/MA2K7/JNK pathway in early brain injury after SAH in rats. Neuropharmacology 108, 316–323 (2016).

Pan, J. et al. The role of PI3K signaling pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci., 16, 1459025. (2024).

Goyal, A., Agrawal, A., Verma, A. & Dubey, N. The PI3K-AKT pathway: A plausible therapeutic target in parkinson’s disease. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 129, 104846 (2023).

Ramasubbu, K. & Devi Rajeswari, V. Impairment of insulin signaling pathway PI3K/Akt/mTOR and insulin resistance induced ages on diabetes mellitus and neurodegenerative diseases: A perspective review. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 478 (6), 1307–1324 (2023).

Khan, H. et al. Pharmacological modulation of PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR/ERK signaling pathways in ischemic injury: A mechanistic perspective. Metab. Brain Dis. 40 (3), 1–9 (2025).

Bhatia, V., Vikram, V., Chandel, A. & Rattan, A. Interplay between PI3k/AKT signaling and caspase pathway in alzheimer disease: Mechanism and therapeutic implications. Inflammopharmacology 15, 1–8 (2025).

Yu, H. J. & Koh, S. H. The role of PI3K/AKT pathway and its therapeutic possibility in alzheimer’s disease. Hanyang Med. Rev. 37 (1), 18–24 (2017).

O’Neill, C. PI3-kinase/Akt/mTOR signaling: Impaired on/off switches in aging, cognitive decline and alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Gerontol. 48 (7), 647–653 (2013).

Heras-Sandoval, D., Avila-Muñoz, E. & Arias, C. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mTor pathway as a therapeutic target for brain aging and neurodegeneration. Pharmaceuticals 4 (8), 1070–1087 (2011).

Afghah, Z. et al. Involvement of endolysosomes and Aurora kinase A in the regulation of amyloid β protein levels in neurons. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (11), 6200 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. Tozasertib activates anti-tumor immunity through decreasing regulatory T cells in melanoma. Neoplasia 48, 100966 (2024).

Sebghatollahi, Z. et al. Signaling pathways in oxidative Stress-Induced neurodegenerative diseases: A review of phytochemical therapeutic interventions. Antioxidants 14 (4), 457 (2025).

Jiang, T., Sun, Q. & Chen, S. Oxidative stress: A major pathogenesis and potential therapeutic target of antioxidative agents in parkinson’s disease and alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 147, 1–9 (2016).

Acosta-Martinez, M. & Cabail, M. Z. The PI3K/Akt pathway in meta-inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (23), 15330 (2022).

Liu, D. et al. Effects of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway on the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in rats with cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Exp. Therap. Med. 14 (6), 5755–5760 (2017).

Gao, Y., Chu, S., Li, J., Zhang, Z. & Xia, C. Fibroblast Growth Factor 1 (FGF1) Improves Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Function in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease by Activating PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway, 109, 1500–1508 (Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2019).

Meng, Y., Wang, W., Kang, J., Wang, X. & Sun, L. Role of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway in apoptotic cell death in the cerebral cortex of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Exp. Therap. Med. 13 (5), 2417–2422 (2017).

Song, G., Ouyang, G. & Bao, S. The activation of akt/pkb signaling pathway and cell survival. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 9 (1), 59–71 (2005).

Yu, X. et al. Dorsal root ganglion macrophages contribute to both the initiation and persistence of neuropathic pain. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 264 (2018).

Tyagi, E., Agrawal, R., Nath, C. & Shukla, R. Cholinergic protection via α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and PI3K-Akt pathway in LPS-induced neuroinflammation. Neurochem. Int. 56 (1), 135–142 (2010).

Baki, L. et al. PS1 activates PI3K thus inhibiting GSK-3 activity and Tau overphosphorylation: Effects of FAD mutations. EMBO J. 23 (13), 2586–2596 (2004).

Ma, T. et al. Suppression of eIF2α kinases alleviates alzheimer’s disease-related plasticity and memory deficits. Nat. Neurosci. 20 (3), 344–355 (2017).

Tomé, D., Dias, M. S., Correia, J. & Almeida, R. D. Fibroblast growth factor signaling in axons: From development to disease. Cell. Commun. Signal. 21 (1), 290 (2023).

Okada, T. et al. FGF-2 attenuates neuronal apoptosis via FGFR3/PI3k/Akt signaling pathway after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 8203–8219 (2019).

Zhai, W. et al. The fibroblast growth factor system in cognitive disorders and dementia. Front. NeuroSci. 17, 1136266 (2023).

Gharbi, S. I. et al. Exploring the specificity of the PI3K family inhibitor LY294002. Biochem. J. 404 (1), 15–21 (2007).

Di, Y. & Chen, X. L. Inhibition of LY294002 in retinal neovascularization via down-regulation the PI3K/AKT-VEGF pathway in vivo and in vitro. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 11 (8), 1284 (2018).

Hasinoff, B. B. & Patel, D. The lack of target specificity of small molecule anticancer kinase inhibitors is correlated with their ability to damage myocytes in vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmcol. 249 (2), 132–139 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Chitkara University, Punjab for providing all the technical facilities for research work.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R142), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University,Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G.S., ; Data curation, D.K., A.K.G., A.K., and V.S.; Formal analysis, G.B., S.H.A. and A.H.A.; Investigation, D.K., A.K.G., A.K., and V.S.; Methodology, D.K., A.K.G., A.K., and V.S.; Resources, M.P. and A.A.; Validation, M.P. and A.A.; Visualization, M.P. and A.A., Writing – original draft, D.K., A.K.G., A.K., and V.S.; Writing – review & editing, T.G.S., N.N.W. Project administration, G.B., and B.A.A. Supervision, T.G.S. M.P. and A.A. all authors reviewed and approved the final copy.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval statement

The study was performed in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. The experimental protocol was approved by Committee for Control and Supervision of Experimentation on Animals (CCSEA), Government of India on animal experimentation. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaur, D., Grewal, A.K., Almasoudi, S.H. et al. Neuroprotective effect of Tozasertib in Streptozotocin-induced alzheimer’s mice model. Sci Rep 15, 28963 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13920-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13920-5