Abstract

In this study, we introduce an innovative reflective fiber optic sensor platform for detecting amlodipine (AML) concentrations based on surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The sensor architecture features a reflective fiber coated with a thin layer of gold to induce SPR, while a graphene oxide/chitosan (GOCH) composite, applied via spin-coating, serves as the selective sensing layer for AML. The incorporation of a nanocomposite enables the generation of resonance dips in the spectral output, each demonstrating different sensitivities to AML concentration variations. These resonance wavelength shifts allow for accurate quantification of AML by employing Langmuir and Sips adsorption isotherm models. Experimental analysis reveals a remarkable sensitivity of 2315.2 nm/µM for AML detection, alongside a strong binding affinity of 60.12 µM⁻1. The proposed sensor also demonstrates excellent stability and is well-suited for convenient packaging, highlighting its potential for remote and practical sensing applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The potential for ultra-sensitive and rapid detection of analytes at incredibly low concentrations, even down to nano and Atto Molar levels, presents numerous opportunities in various fields1,2. These applications range from early disease diagnosis like myocardial infarction, cancer, and tuberculosis to disease prognosis3,4,5,6. This advanced detection capability also allows for analyzing analytes from small serum or plasma samples and exploring alternative body fluids such as saliva, urine, and sweat as safer alternatives to traditional blood samples7,8,9,10. While lateral flow assay (LFA) technology has shown promise in point-of-care diagnostics due to its cost-effectiveness and quick results, it does have limitations like low sensitivity and the need for additional reader instruments, limiting its use to semi-quantitative analysis11,12,13. We suggest utilizing fiber optic transducers to overcome these challenges and develop highly sensitive transduction systems without complex washing and signal amplification steps14,15. Fiber-optic sensors based on SPR offer several advantages, including simpler optical coupling, compact design, cost-effectiveness compared to bulk optical setups, efficient excitation of plasmonic nanostructures, and a wide dynamic range supported by recent advancements in optoelectronics16,17,18. The initial focus of SPR biosensors in the early 1980s was on gas detection, however, there has been a significant increase in publications on using SPR biosensors for detecting chemical and biological substances19,20,21. The technology and applications of SPR biosensors have advanced remarkably, with SPR biosensing becoming the primary method for studying biomolecular interactions since the 1990s22,23,24,25.

The exceptional architecture and impressive electrical conductivity of the GO layer position it as a superior two-dimensional material for biosensor applications. This allows for precise and highly sensitive detection of a wide range of targets, including viruses, cancer cells, bacteria, Alzheimer’s biomarkers, various biological substances, and environmental agents26,27,28,29,30. CH enhances the physical strength of biosensors and incorporates amino functional groups31. The incorporation of GO into surface plasmon resonance sensors has recently led to marked enhancements in the accuracy of detecting biological compounds across different sample types32,33,34. These sensors, which utilize GO to enhance surface plasmons, have extensive applications in medicine, industry, and agriculture due to their compact size and exceptional detection capabilities35,36. Incorporating compounds with functional groups alongside GO in the design of surface plasmon resonance biosensors is a common practice. A specific type of nanocomposite based on GO is expected to detect AML [29,30,31] effectively. Our study focuses on a nanocomposite composed of CH and GO for detecting AML. CH was selected for its abundant –OH and –NH3 groups, which enhance GO’s affinity towards substances, and its ability to form films that aid in the assembly of the nanocomposite on a substrate37. By combining GO and CH, we can leverage the strengths of each component to detect AML without the need for bio-label38.

This research involved modifying the surface of a plasmonic optical fiber (POF) with a GOCH composite to create a biosensor for AML detection. The biosensor was various lengths of the detection area were tested. The surface of the composite was analyzed using FE-SEM (MIRA3 TESCAN). The biosensor was modeled using Langmuir and Sips isotherms, with the Sips model showing better convergence. It had a sensitivity of 2315 nmµM−1 and an affinity coefficient of 0.341. The sensor’s results were validated using real samples and the HPLC method. The stability of the biosensor was tested, showing only a 2.5% decrease over 20 days, which was deemed acceptable.

Material and method

Preparation of GOCH

A revised two-stage synthesis strategy was employed to fabricate the GOCH nanocomposite, drawing on established protocols from existing literature. Initially, a stable dispersion of graphene oxide (GO) was prepared by dispersing 6.0 mg of GO powder into 3.0 mL of double-distilled water, followed by ultrasonication for two hours, yielding a final GO concentration of 2 mg/mL. In parallel, chitosan (CH) was processed by dissolving 0.5 g of its powder in 100 mL of 0.05 M acetic acid, with continuous vigorous stirring maintained overnight, ensuring the chitosan acquired a positive charge. Subsequently, equal volumes of the GO and CH dispersions were thoroughly mixed and again exposed to ultrasonication for an additional two hours, promoting the formation of a uniformly blended GOCH suspension. During this mixing phase, amide bonds were established between the carboxyl functionalities present on GO and the amine groups of CHs, proceeding through a classic nucleophilic addition reaction. This ensured successful covalent integration of both components within the nanocomposite matrix38.

Sensing structure

The sensor system’s structural structure is shown in Fig. 1, which also has a multimode fiber (MMF) and single-mode fiber (SMF) sensing probe. To induce SPR, an Au coating was first deposited on the SMF using an ion sputtering device (SAINTJS-1600). Then, using the dip coating technique, a GOCH nanocomposite layer was produced and applied to the sensor head. The experimental setup includes an ocean spectrometer, a Y-type fiber (Ocean Optics, BIF125-VIS–NIR), and a halogen light source (wavelength range: 380–1100 nm). Light from the source passed through one end of the Y-fiber onto the sensing probe, which reflected the light signal to the spectrometer, and then can be analyzed39,40,41. The output spectrum displayed resonance dip that varied in response to changes in AML concentration, each with distinct sensitivities. As a result, the sensor was capable of simultaneously measuring AML concentration.

Method and theory base

SPR, which normally happens at the border between a metal and a dielectric medium, is the fiber optic SPR sensor’s base. Two electromagnetic waves will resonate if they have matching wave vectors and frequencies with the same propagation direction42. At the metal-medium interface, the evanescent wave produced by complete reflection may exist through the metal layer if the metal layer is thinner than the effective depth of the evanescent wave. An explanation of the wave vector of evanescent wave in the x-direction is as follows:

where ω and θ represent the frequency and angle of the incident light, respectively, and ε0 is the fiber core dielectric constant. The surface plasmon wave oscillates in the z-direction if the metal film plane is oriented in the xy-direction39. Only p-polarized light may cause SPR in POF sensors. The intensity of the reflected light is represented by the

where Rp is the reflective ratio of the p-polarized light, \(N = \frac{D}{L\tan \theta }\)(with D being the fiber diameter and L being the sensing region length), dm represents the thickness of the metal film, rfm, and rme represent the reflection coefficients of the fiber-metal, and metal-GOCH interfaces, respectively39.

Based on the boundary conditions for radiation-free transient electromagnetic fields in SPR and Maxwell’s equations, the wave vector of a surface plasmon wave at a metal-dielectric interface can be expressed as,

where ε2 is the dielectric constant of the surrounding medium and ε1 is the dielectric constant of the metal layer. The evanescent wave vector and the real part of the surface plasmon wave vector have the same x-direction component which helps to explain how the SPR is excited. Corresponding to kx = real (ksp), SPR can occur. Only a part of the incoming light can couple when MMF’s propagated light reaches the SMF core in a basic MMF-SMF system. This part of the propagated light hits the metal layer and then causes a plasmonic resonant dip, or energy loss, in the reflected spectrum. The idea behind SPR sensors based on refractive index variation is demonstrated by the red or blue shifting of the SPR wavelength versus the refractive index rising or falling.

Characteristic parameters of the sensor

To study how the GOCH sensor detects AML, we analyzed its performance based on three key parameters: full width at half maximum (FWHM [nm]) = λ0.5P2−λ0.5P1, sensitivity \(S = \frac{\Delta \lambda res}{{\Delta n}}\;[{\text{nm}}/\mu {\text{M}}]\), and data accuracy D. \(A = \frac{\Delta \lambda }{{FWHM}}\)21,43.

Results

Optimization sensing region

The interaction of light with metal is a key factor in determining the quality of SPR response. To expand the sensing region, we varied the height of the gold-coated region to 3, 8, and 15mm. Fig. 2a illustrates that as the height of the sensing area increases, the depth of the reflection diagram also increases, without any noticeable change in the wavelength of the SPR dip. The optimal scenario is achieved with a sensing region height of 15mm. Additionally, we examined the impact of a composite thin layer of gold and graphene on the SPR diagram post-coating, and compared it to the optimized Au thin film diagram in Fig. 2b, revealing a wavelength shift of approximately 6.5 nm. Previous studies have explored the surface resonance mode of the composite thin, which shifts the focus of the research to investigate the composite material’s behavior38.

Characterization of sensing surface

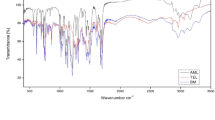

Figure 3a shows the FE-SEM micrographs of the bare plasmonic optical fiber (POF) and the GOCH-modified POF illustrated in Fig. 3b and c. Fig 3b and c illustrate the uneven structure of the heterogeneous GOCH nanocomposite distributed uniformly on the surface of the POF. CH was integrated into the layers of GO nanosheets, resulting in enlarged distances between layers and increased wrinkle width when viewed at higher magnification. This process effectively increased the surface area of the sensing medium. Additionally, the EDS spectrum in Fig. 3d demonstrates characteristic peaks of C, O, and N elements, confirming the presence of GO and CH in the modified Au layer and indicating the success of the modification process. Also, FT-IR analysis related to GOCH composite has been investigated in detail in a previous study.38

Measurement of AML

A solution of Amlodipine with a concentration of 500μM was initially prepared and then, using the formula M1V1=M2V2, at room temperature, solutions with concentrations of 250, 100 to 1nM were diluted. Subsequently, a measurement test was conducted using a designed sensor by injecting 100µL of the diluted solution. The sensor demonstrated consistent behavior within the range of 0.025-250μM after conducting multiple tests and replicating the experiment 5 times. Increasing the concentration beyond 100μM resulted in the SPR diagram departing from linearity, leading to a decrease in the slope of the wavelength changes. Non-linear Langmuir and Sips isotherm methods were employed for modeling purposes44. Plasmon resonance diagrams (Fig. 4a and b) on the sensor’s surface exhibited a red shift due to the heightened refractive index of the analyte environment with increasing concentration. This change in refractive index allows for greater light penetration in environments with higher concentrations, a phenomenon rooted in fundamental physics. Furthermore, Fig. 4c illustrates the relationship between concentration changes and wavelength shifts to provide insight into the sensor’s behavior. Additionally, Fig. 4d showcases the sensor’s sensitivity, a crucial parameter in sensor development.

The outlined parameters in Sect. “Characteristic parameters of the sensor” are presented in Table 1. Performance evaluation of the sensor by comparing its behavior with the previous research is in Table 2.

The binding affinities of SPR sensors towards AML molecules were calculated for both bare gold chip and GOCH thin film surfaces using non-linear fitting with the Langmuir isotherm model32. Refer to Fig. 5 for the results. The equation for the Langmuir isotherm model is provided below:

In this context, C represents the concentration of AML, Δλ denotes the change in resonance wavelength, and K signifies the binding affinity. The binding affinity constant for AML to the POF is calculated to be 8. 07 μM−1, whereas it is 60.12 μM−1 for GOCH/ POF. It is important to highlight that the thin film displays a large affinity constant compared to the uncoated POF, suggesting a more robust interaction with AML molecules. The Sips isotherm model was utilized to estimate the heterogeneous surface of the electrode.

In Eq. (2), the Sips affinity value is represented by Ks, while the AML concentration is denoted by C. The heterogeneity constant, n, varies from 0 to 1. The data in Fig. 4b shows that the Sips model (R2 = 0.964) fits better than the Langmuir model (R2 = 0.951). A heterogeneity constant of 0.341 suggests a surface phenomenon with varying properties45.

Selectivity of GOCH/POF

To assess the specificity of the GOCH/POF-based SPR biosensor toward amlodipine (AML), comparative analyses were conducted with other drugs of analogous physicochemical features, namely azithromycin, promethazine, and aspirin, each tested at a concentration of 25 μM (in 200 μL volumes). As depicted in Fig. 6a, the interaction of amlodipine with the sensor produced a wavelength shift nearly threefold greater than that resulting from the other reference compounds. Figure 6b presents the molecular structures considered during selectivity evaluation. This heightened response is attributed to the simultaneous interactions between amlodipine and the COOH and NH2 functional groups present on the surface of the GO/CH nanocomposite. Such multivalent binding, referenced in previous studies38,46 endows the sensor with pronounced selectivity for AML: the unique alignment of functional groups on AML and the nanocomposite provides multiple anchoring sites, enhancing molecular recognition. When compared with molecules of similar concentration and molarity in the SPR system, amlodipine’s higher molecular weight further intensified the sensor’s response, generating a more substantial wavelength change. This indicates both enhanced adsorption and specificity for AML detection.

Table 2 provides a comparison between the performance of this biosensor and that of other reported sensing strategies, underlining its superior detection efficacy and application potential.

From a molecular perspective, amlodipine, a calcium channel blocker, is characterized by the presence of amine functionalities and fused heterocyclic rings. These features facilitate robust interactions with the hydroxyl, carbonyl, and epoxy groups of graphene oxide. In contrast, simpler structures such as aspirin and ibuprofen—classified as NSAIDs—comprise mainly benzene rings and carboxylic acid groups, which leads to weaker, less extensive adsorption on the GO surface47. While promethazine presents aromaticity, its structure is considerably more resistant to oxidation relative to amlodipine48. The distinctive electronic and structural properties of amlodipine thus result in superior adsorption and more facile electrochemical interactions with the sensor surface, explaining its enhanced detection by the developed SPR platform as opposed to other examined pharmaceuticals.

Real sample test

The developed biosensor based on GOCH/POF was employed to quantify Amlodipine in various real-world samples, including urine and commercially available tablets. As detailed in Table 3, a comparison of these results with those obtained from the HPLC method demonstrated the biosensor’s promising potential for practical applications. To evaluate the reproducibility of the modified electrode for Amlodipine detection, five independent tests were conducted. The consistently low relative standard deviation (RSD) \({\text{RSD }}\% = \left[ {\frac{Standard Deviation}{{Mean}}*100} \right]\) values obtained confirm the reliability and precision of the biosensor, underlining its suitability for this purpose. Additionally, the average spectral response is presented in Fig. 1Sa, while all individual measurements are illustrated in Fig. 1Sb.

Stability and reproducibility

Two, ten days, and 20 days of testing at 5 and 25 μM were used to evaluate the biosensor design’s stability and repeatability. The temperature of the biosensor’s storage chamber was maintained at 4 °C. The suggested biosensor has stability and repeatability, with measured variations of less than 2.5%. Given that graphene oxide and chitosan are known to be stable at ambient temperature, this degree of stability was anticipated53. The outcomes are displayed in Fig. 7.

Conclusion

In this study, we devised an innovative biosensor for the detection of amlodipine (AML) by integrating graphene oxide–chitosan hybrid (GOCH) and a plasmonic optical fiber (POF), both subjected to targeted surface modifications. We conducted an extensive review of prior studies related to the composite materials used, ensuring a well-informed approach to sensor fabrication. Characterization techniques, specifically scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), confirmed the successful surface engineering and homogeneous morphology of the composite, providing confidence in the platform’s structural integrity. The sensor’s analytical performance toward AML detection was comprehensively evaluated through adsorption studies modeled by both Langmuir and Sips isotherms. Our findings demonstrated that the Sips isotherm provided a superior fit for the adsorption data compared to the Langmuir model. Within this framework, the affinity constant was calculated at 0.341, reflecting robust target interaction. The biosensor exhibited a broad linear detection range from 0.025 to 250 μM and achieved an impressive limit of detection of 25 nM. To validate the sensor’s applicability in real-world scenarios, its performance was benchmarked against high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of both urine samples and commercial AML tablets. The results showed an excellent agreement between methods, with a relative standard deviation (RSD) consistently below 5%, confirming the sensor’s reliability and reproducibility.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon reasonable request by the corresponding Authors (Hassan Nasiri: h.nasiri@tabrizu.ac.ir, karim Abbasian : k_abbasian@tabrizu.ac.ir).

References

Lee, S., Lee, J., Cao, Y., An, C. & Kang, S. H. Nanomaterial-based single-molecule optical immunosensors for supersensitive detection. Biosensors Bioelectron. X 11, 100191 (2022).

Kalambate, P. K. et al. Nanomaterials-based electrochemical sensors and biosensors for the detection of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 143, 116403 (2021).

Xu, W. et al. Diagnosis and prognosis of myocardial infarction on a plasmonic chip. Nat. Commun. 11, 1654 (2020).

Zhu, W., Wei, Z., Han, C. & Weng, X. Nanomaterials as promising theranostic tools in nanomedicine and their applications in clinical disease diagnosis and treatment. Nanomaterials 11, 3346 (2021).

Tajbakhsh, A. et al. COVID-19 and cardiac injury: Clinical manifestations, biomarkers, mechanisms, diagnosis, treatment, and follow up. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 19, 345–357 (2021).

Nasiri, H. & Abbasian, K. Surface plasmon resonance detection of anti-cancer drug flutamide by graphitic carbon nitride/chitosan nanocomposite. Sci. Rep. 15, 2278. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86665-w (2025).

Sim, D. et al. Biomarkers and detection platforms for human health and performance monitoring: A review. Adv. Sci. 9, 2104426 (2022).

Song, M., Bai, H., Zhang, P., Zhou, X. & Ying, B. Promising applications of human-derived saliva biomarker testing in clinical diagnostics. Int. J. Oral Sci. 15, 2 (2023).

Brazaca, L. C. et al. The use of biological fluids in microfluidic paper-based analytical devices (μPADs): Recent advances, challenges and future perspectives. Biosensors Bioelectron. 15(246), 115846 (2024).

Saghatforoush, L. et al. Electro-oxidation sensing of sumatriptan in aqueous solutions and human blood serum by Zn(II)-MOF modified electrochemical delaminated pencil graphite electrode. Sci. Rep. 13, 16803. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44034-5 (2023).

Lee, S. et al. Recent advances in point-of-care testing of COVID-19. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52(24), 8500–8530 (2023).

He, W., Wang, M., Cheng, P., Liu, Y. & You, M. Recent advances of upconversion nanoparticles-based lateral flow assays for point-of-care testing. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 176, 117735 (2024).

Ghosh, A., Banerjee, A. & Srivastava, R. Surface Engineering and Functional Nanomaterials for Point-of-Care Analytical Devices 323–344 (Springer, Cham, 2023).

Yin, M.-J. et al. Recent development of fiber-optic chemical sensors and biosensors: Mechanisms, materials, micro/nano-fabrications and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 376, 348–392 (2018).

Tabassum, S. & Kumar, R. Advances in fiber-optic technology for point-of-care diagnosis and in vivo biosensing. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 1900792 (2020).

Gupta, B. D. & Kant, R. Recent advances in surface plasmon resonance based fiber optic chemical and biosensors utilizing bulk and nanostructures. Opt. Laser Technol. 101, 144–161 (2018).

Gupta, B. D., Verma, R. & Srivastava, S. K. Fiber Optic Sensors Based on Plasmonics (World Scientific, UK, 2015).

D’Agata, R., Bellassai, N. & Spoto, G. Exploiting the design of surface plasmon resonance interfaces for better diagnostics: A perspective review. Talanta 266, 125033 (2024).

Lundström, I. From a laboratory exercise for students to a pioneering biosensing technology. Plasmonics 9, 741–751 (2014).

Nasiri, H. & Abbasian, K. High-sensitive surface plasmon resonance sensor for melamine detection in dairy products based on graphene oxide/chitosan nanocomposite. Food Control 166, 110761 (2024).

Nasiri, H., Abbasian, K. & Baghban, H. Sensing of lactose by graphitic carbon nitride/magnetic chitosan composites with surface plasmon resonance method. Food Biosci. 61, 104718 (2024).

Nguyen, H. H., Park, J., Kang, S. & Kim, M. Surface plasmon resonance: A versatile technique for biosensor applications. Sensors 15, 10481–10510 (2015).

Capelli, D., Scognamiglio, V. & Montanari, R. Surface plasmon resonance technology: Recent advances, applications and experimental cases. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 163, 117079 (2023).

Nasiri, H., Salahandish, M., Sharifi, H. & Mohammadzadehasl, N. Dependence of extinction cross-section, absorption and surface plasmon resonance of nanoparticle surface size and concentration of Silica@Gold nanoparticles. Biomed. Mater. Devices https://doi.org/10.1007/s44174-024-00272-3 (2025).

Salahandish, M., Ghahramani Bigbaghlou, R., Nasiri, H. & Pourziad, A. Enhanced plasmonic absorption using MIM ring resonator structures for optical detector applications. Phys. Scr. 99, 085552. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/ad6497 (2024).

Peña-Bahamonde, J., Nguyen, H. N., Fanourakis, S. K. & Rodrigues, D. F. Recent advances in graphene-based biosensor technology with applications in life sciences. J. Nanobiotechnol. 16, 75 (2018).

Lee, J., Kim, J., Kim, S. & Min, D.-H. Biosensors based on graphene oxide and its biomedical application. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 105, 275–287 (2016).

Raikwar, S., Prajapati, Y. K., Srivastava, D. K. & Saini, J. P. Graphene oxide based SPR sensor for sensing of sea water concentration. Res Optics 1, 100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rio.2020.100011 (2020).

Nasiri, H., Abbasian, K. & Nilghaz, A. Nitrite detection with trapping in rGO/Fe2O3 composite based on surface plasmon resonance. Inorgan. Chem. Commun. 176, 114327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2025.114327 (2025).

Essa, E. I., Asker, M. A. & Sedeeq, F. T. Evaluating OADM network simulation and an overview based metropolitan application. J. Intell. Syst. 31, 27–39 (2021).

Negm, N. A. et al. Performance of chitosan polymer as platform during sensors fabrication and sensing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 165, 402–435 (2020).

Nasiri, H., Baghban, H., Teimuri-Mofrad, R. & Mokhtarzadeh, A. Chitosan/polyaniline/graphene oxide-ferrocene thin film and highly-sensitive surface plasmon sensor for glucose detection. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55, 948 (2023).

Raikwar, S., Srivastava, D., Saini, J. & Prajapati, Y. 2D-antimonene-based surface plasmon resonance sensor for improvement of sensitivity. Appl. Phys. A 127, 1–8 (2021).

Raikwar, S., Prajapati, Y. & Srivastava, D. (2021).

Srivastava, A. K., Dev, A. & Karmakar, S. Nanosensors and nanobiosensors in food and agriculture. Environ. Chem. Lett. 16, 161–182 (2018).

Tung, T. T. et al. Recent advances in sensing applications of graphene assemblies and their composites. Adv. Func. Mater. 27, 1702891 (2017).

Nasiri, H., Abbasian, K., Salahandish, M. & Elyasi, S. N. Sensitive surface plasmon resonance biosensor by optimized carboxylate functionalized carbon nanotubes/chitosan for amlodipine detecting. Talanta 276, 126249 (2024).

Nasiri, H., Abbasian, K. & Baghban, H. Highly sensitive quantification of Amlodipine in real samples using graphene oxide-chitosan surface plasmon resonance sensor. Sens. Actuators, A 368, 115152 (2024).

Zhang, Y.-N., Siyu, E., Tao, B., Wu, Q. & Han, B. Reflective SPR sensor for simultaneous measurement of nitrate concentration and temperature. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 68, 4566–4574 (2019).

Wang, X.-D. & Wolfbeis, O. S. Fiber-optic chemical sensors and biosensors (2015–2019). Anal. Chem. 92, 397–430 (2019).

Matějec, V., Kašík, I. & Bartoň, I. Fiber-optic nanosensors for chemical detection. Chemosensors 11, 521 (2023).

Zhao, Y., Deng, Z.-Q. & Wang, Q. Fiber optic SPR sensor for liquid concentration measurement. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 192, 229–233 (2014).

Qi, M., Zhang, N. M. Y., Li, K., Tjin, S. C. & Wei, L. Hybrid plasmonic fiber-optic sensors. Sensors 20, 3266 (2020).

Saadi, R., Saadi, Z., Fazaeli, R. & Fard, N. E. Monolayer and multilayer adsorption isotherm models for sorption from aqueous media. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 32, 787–799 (2015).

Kalam, S., Abu-Khamsin, S. A., Kamal, M. S. & Patil, S. Surfactant adsorption isotherms: A review. ACS Omega 6, 32342–32348 (2021).

Kadhem, A. J., Gentile, G. J. & Fidalgo de CMM.,. Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) in sensors for environmental and biomedical applications: A review. Molecules 26(20), 6233 (2021).

Minuz, P. et al. Amlodipine and haemodynamic effects of cyclo-oxygenase inhibition. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 39, 45–50 (1995).

Saha, B. K., Bonnier, A. & Chong, W. Rapid reversal of vasoplegia with methylene blue in calcium channel blocker poisoning. Afr. J. Emergency Med. 10, 284–287 (2020).

Doulache, M., Bakirhan, N. K., Saidat, B. & Ozkan, S. A. Highly sensitive and selective electrochemical sensor based on polyglycine modified glassy carbon electrode for simultaneous determination of amlodipine and ramipril from biological samples. J. Electrochem. Soc. 167, 027511 (2020).

da Silva, E. M., de Oliveira, G. C., de Siqueira, A. B., Terezo, A. J. & Castilho, M. Development of a composite electrode based on graphite and polycaprolactone for the determination of antihypertensive drugs. Microchem. J. 158, 105228 (2020).

Firouzi, M., Giahi, M., Najafi, M., Homami, S. S. & Mousavi, S. H. H. Electrochemical determination of amlodipine using a CuO–NiO nanocomposite/ionic liquid modified carbon paste electrode as an electrochemical sensor. J. Nanopart. Res. 23, 1–12 (2021).

Farvardin, N., Jahani, S., Kazemipour, M. & Foroughi, M. M. The synthesis and characterization of 3D mesoporous CeO2 hollow spheres as a modifier for the simultaneous determination of amlodipine, hydrochlorothiazide and valsartan. Anal. Methods 12, 1767–1778 (2020).

Kumar, S. & Koh, J. Physiochemical and optical properties of chitosan based graphene oxide bionanocomposite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 70, 559–564 (2014).

Funding

This research is supported by the University of Tabriz by grant no: S/1490.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fidan T. sedeeq: software, repeat experience, prediction Hassan Nasiri: Software, validation, edit and writing, experience Karim Abbasian: Supervision, Edit and writing, Funding Hadi Khodaei: software, prediction, edit and writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not included.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sedeeq, F.T., Nasiri, H., Abbasian, K. et al. Ultrasensitive detection of amlodipine using plasmonic optical fiber sensors enhanced with graphene oxide and chitosan nanocomposite. Sci Rep 15, 28662 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13980-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13980-7

This article is cited by

-

Advances on Gold Nanoparticle-based Biosensors for Detection of SARS-CoV-2

BioNanoScience (2026)