Abstract

Salt stress affects plant growth and development to a great extent in establishing biochemical imbalances and inducing oxidative damage. The effort was undertaken to assess the relative effectiveness of chitosan pre- and post-treatments in relieving salt stress in Brassica napus L., a moderately salt-sensitive oilseed crop, with respect to the expression patterns of P5CS, PIP, and APX genes along with proline and protein accumulation. One factorial experiment was performed under controlled conditions, where the plants were exposed to varying NaCl concentrations (50, 100, 150, and 200 mM), following either the pre-treatment of chitosan (50 mg/L) or post-treatment of chitosan (50 and 100 mg/L). Gene expression analysis by means of qRT-PCR showed a significant (p < 0.05) upregulation under pre-treatment of P5CS and APX, thereby enhancing osmoprotection and antioxidant defense; however, under post-treatment, the response of P5CS and APX was only moderate. Post-treatment levels of proline and total protein were markedly higher as well. Interestingly, proline content increased by approximately 743% in pre-treated plants at 200 mM of NaCl compared to the control (p < 0.05), indicating enhanced stress tolerance. Besides, the plants subjected to pre-treatment were perfectly grown at 200 mM NaCl whereas those subjected to post-treatment were unable to survive at 150 mM. These findings reveal that the salt tolerance mechanism is better gained by chitosan pre-treatment due to osmotic adjustment enhancement and antioxidative mechanism. This study presents the potential of chitosan to be developed as a strategic biostimulant in promoting crop resistance to saline conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Salt stress is among the imperiling abiotic conditions affecting agricultural productivity worldwide, especially in the case of salt-sensitive crops like Brassica napus L. (canola or rapeseed)1. The salinity hampers some essential physiological and biochemical processes such as the uptake of water, nutrient balancing, and carbon assimilation, finally leading to the reduction in growth and yield of the plant2,3,4. Osmotic stress sets in immediately after salt exposure in the initial phase, once the salinity reaches high levels, ion toxicity takes place; both of these malpractices lead to a disruption of ionic homeostasis, thereby affecting cellular functioning5,6,7,8. Plants produce osmolites like proline and glycine betaine, etc., which help them to keep osmotic balance in place9. An excessive quantity of sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻) ions interferes with enzymatic activity, nutrient uptake, and cellular hydration; hence, their ejection toward regions of lower excess occurs through selective ion transporters10,11. Additionally, salt stress triggers oxidative stress accompanied by an overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as H₂O₂, O₂⁻, and ·OH, which exacerbate cellular components unless depleted by antioxidant mechanisms12,13. Indeed, stress conditions induce the reprogramming of gene expression and the activation of defense signaling pathways14.

Chitosan, a biopolymer derived from chitin, has gained attention as a biostimulant capable of enhancing plant resilience to environmental stresses, including salinity15. Chitosan functions as a natural defense elicitor by triggering the expression of stress-responsive genes and stimulating various defense signaling pathways in plants16. Additionally, it plays a crucial role in promoting plant growth by modulating key cellular processes, including ion homeostasis and antioxidant defense mechanisms, particularly under stress conditions17. Chitosan mediates stress signaling pathways, leading to the upregulation of osmoprotectants, aquaporins, and antioxidant enzymes18. P5CS (Δ¹-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase) is one of the most crucial genes involved in the salt stress response that is important for the synthesis of proline, an osmoprotectant that stabilizes cellular structures under stress19. The other important genes include PIP (plasma membrane intrinsic protein), which controls the transportation of water through cellular membranes so as to balance the quantity of cellular water in cells under stress conditions; and APX (ascorbate peroxidase), which is a vital enzyme that scavenges for reactivity oxygen species (ROS), sustaining the activities of cells under oxidative damage due to salt stress20. Chitosan has been extensively studied for several decades for alleviating salt-related stress. However, limited research has been conducted to compare its effects on gene expression in rapeseed using different strategies of chitosan application, including pre-treatment and post-treatment. Knowledge of how various modes of chitosan application affect the expression pattern of P5CS, PIP, and APX genes may help to improve its usage for enhancing salt tolerance in rapeseeds. This study intends to explore the expression pattern of these genes under salt stress conditions with respect to the different applications of chitosan as pre-treatment or post-treatment; thus, it will assist in developing advanced management strategies for salinity in crop production.

Materials and methods

Plant material

The current study performed investigations using the German hybrid rape seed cultivar of Rohan, which was provided by the company Arman Sabz from Adina in Isfahan.

Experimental procedures: pre-treatment

A completely randomized factorial design was used with three biological replicates per treatment. Plastic pots (14 cm diameter) were filled with a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of cocopeat and perlite. Seeds were sown and after 8 days of germination, seedlings were irrigated with Hoagland solution for 15 days. Chitosan pre-treatment (50 mg/L) was applied via foliar spray for 4 consecutive days. After this, plants were subjected to NaCl salinity stress at concentrations of 0 (control), 50, 100, 150, and 200 mM for 4 days. Leaf sampling was performed at three time points: 0, 10, and 20 days after salt treatment initiation. Each condition included three biological replicates (n = 3). Gene expression analysis was carried out using qRT-PCR (Fig. 1).

Experimental procedures: post-treatment

This experiment was also conducted in a completely randomized factorial design with three replicates per treatment. Seeds were sown in plastic pots (14 cm diameter) filled with a 1:1 (v/v) cocopeat and perlite mix and irrigated three times daily with distilled water until germination. After germination, plants were irrigated daily with distilled water and weekly with Hoagland solution. At the three-leaf stage, plants were subjected to four salinity treatments (0, 50, 100, and 150 mM NaCl) and three chitosan levels (0, 5, and 10 mg/L). Chitosan was applied via foliar spray every other day for 4 weeks. NaCl was also applied consistently throughout this period. For gene expression analysis, leaf samples were collected 48 h after the final treatment. All treatments included three biological replicates (n = 3) (Fig. 1).

Timeline of experimental treatment and sampling for both pre- and post-treatment periods. Germination took place in the first 8 days, after which Hoagland nutrient irrigation was started. During the pre-treatment stage, chitosan was applied, at a concentration of 50 mg/L, for 4 days; then, the NaCl treatments (50 to 200 mM) were applied. The post-treatment design called for spraying the plants with chitosan (0, 5, and 10 mg/L concentrations) and NaCl (0, 50, 100, and 150 mM) every 2 days for a duration of 4 weeks. The gene expression study was done 48 h after the final treatment.

RNA extraction and the synthesis of cDNA

Total RNA was isolated from precipitation with lithium chloride according to previous methods2122;. First, cDNA synthesis was performed according to the manufactures protocol using the GeneALL kit (Cat. No. 601–602). A In the first step, a 0.2 mL vial containing 2.5 µL of RNA, 0.5 µL of dNTP mix, 0.5 µL of oligo dT, and 0.5 µL of random hexamer was placed in a PCR machine and incubated at 70 °C for 5 min. The vial was then removed and placed on ice for 2 min. Afterward, 0.5 µL of reverse transcriptase, 0.5 µL of 2X buffer, and 0.5 µL of RNasin were added to each vial. The reaction mixture was then subjected to PCR cycling conditions: 25 °C for 10 min, 42 °C for 50 min, and 80 °C for 10 min. The cDNA products were frozen and stored at last for further analyses at −20 °C.

Real-time PCR

In this study, the real-time PCR runs were performed using an ABI Step One Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) along with a BioFACT™ kit. This was performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction manual. Following completion of PCR amplification and establishment of the threshold line, Cycle Threshold (Ct) values from the amplification curves were exported from the Gene Rotor software to an Excel spreadsheet for analysis. Data normalization was done using the expression of the ribosomal 16 S RNA gene in the GenEx software environment. SPSS V20 was used for statistical analysis and graphical representation, as detailed in Table 123. Primers were designed by means of Gene Runner v6.5.5 × 64, a program commonly used for primer design considerations and mainly based on the sequences of the target genes. The primers were subsequently optimized for specificity and efficiency toward the following target genes: P5CS, PIP, and APX, along with a reference gene, 18 S rRNA. They were synthesized on an ABI 394 synthesizer (ABI, USA) following standard protocols for oligonucleotide synthesis in order to yield the desired quality of primers for the purpose of RT-PCR amplification with recommended purity and sequence fidelity.

Reference for primer sequences, annealing temperature, and accession numbers form the NCBI GenBank for ORF-1ab targets is provided in Table 1.

Formula1: ΔCT = CT (a target gene*) – CT (a reference gene**).

*= PIP, APX, P5CS.

**= mCtrRNA.

Preparation and activity assay of ascorbate peroxidase (APX)

Plant tissues were powdered with liquid nitrogen to a fine powder, and 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer solution (pH 7.4) containing 0.6 M KCl, 7 mM MgCl₂, 3 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 5% PVP was added to 0.25 g of tissue material. The homogenized mixture was filtered, and the resulting solution was centrifuged at 4 °C at 30,000 g for 35 min. The supernatant obtained was subsequently used for the measurement of enzyme activity for APX, following the protocols established by24,25. Enzyme activity assays were conducted using 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) with 20 mM MgCl₂ and other essential components, with absorbance measured at 535 nm as per the adaptations by26,27.

Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity was determined following the method described by28. The reaction mixture contained 2 mL of 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and 20 µL of 5 mM hydrogen peroxide, maintained in an ice bath. Subsequently, 100 µL of the enzyme extract was added, and the absorbance change at 290 nm was recorded. The reaction was initiated by adding 10 µL of 50 µM ascorbate solution. The enzyme activity was expressed as the change in absorbance per minute per milligram of protein.

Determination of total protein content

Plant sample protein total was determined by the Bradford assay29. In brief, 20 µL of the sample extracts was added to microplate wells, followed by 200 µL of Bradford reagent freshly prepared. The mixture was kept at room temperature for a color development time of 10 min. Absorbance was read at 595 ± 20 nm in an ELISA microplate reader. A standard curve was prepared from a series of dilutions of protein.

BSA (bovine serum albumin) being used as the standard protein. By applying the linear regression equation generated from the standard curve, the protein concentration in the samples was calculated (formulae 2):

Formula2: y = 0.0136x + 0.0196.

where y represents the absorbance and x corresponds to the protein concentration (µg/mL).

Determination of proline content

Proline was analyzed based on30 procedure with some alterations. Tidy powders from the plant specimens were prepared and 0.1 g powder was sampled and homogenized in 10 mL 3% sulfosalicylic acid. Homogenate was filtered through paper filter, and to the equal amount of same solution of the filterate 2 mL of filtrate was mixed with equal volumes of ninhydrin reagent and glacial acetic acid in a test tube. The resulting mixture was then incubated in a water bath at 100 °C for 1 h. The tubes were allowed to cool, and 4 mL of toluene was added using a fume hood. The tubes were shaken hard for 17–20 s so that the phase could separate. The upper organic phase containing the pink complex was decanted, and absorbance at 520 nm was read using a spectrophotometer.

Quantification of mineral components

The mineral composition of the plant materials was analyzed by31 but with minor modifications. The aerial parts of the plants are oven-dried at 70 °C for 48 h; 0.1 g of dry matter was weighed, powdered, and ashed in an electric furnace at 160 °C for 14 h. Ash was cooled and dissolved in 3–5 mL of distilled water, filtered, and placed in special plastic tubes. Concentration of mineral elements was measured using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer.

Statistical analyses

Following the acquisition of experimental data, preliminary statistical assessments were conducted to prepare the dataset for analysis of variance (ANOVA). To decipher complex multivariate relationships, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed alongside Pearson correlation analysis. Additionally, a flower plot was utilized to visually represent the degree of overlap among multiple samples relative to a core reference sample, facilitating an intuitive comparative analysis. Given the heterogeneity in measurement scales, data were standardized by transforming all variables to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, ensuring uniformity in statistical comparisons. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test to determine significant differences among treatment groups. Each treatment included three biological replicates (n = 3). Statistical analyses were executed using SPSS (Version 20), ClustVis (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/), and SRplot (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/en), with the results systematically interpreted and presented. Significance levels of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

Based on the experimental findings, it is evident that Pre-Treatment with chitosan significantly enhanced the plant’s ability to tolerate salinity stress, allowing growth even at high salt concentrations of up to 200 mM NaCl. In contrast, Post-Treatment did not support growth at 200 mM NaCl, with the plants failing to survive at this concentration, though they did manage to grow at 150 mM NaCl. This suggests that Pre-Treatment, by priming the plants before stress exposure, has a more robust impact on improving salinity tolerance. The chitosan treatment in the Pre-Treatment phase likely induced osmotic regulation and ion homeostasis mechanisms that better equipped the plants to handle higher salinity levels. Therefore, Pre-Treatment appears to be a more effective strategy for promoting growth under salt stress conditions in Brassica napus L., as compared to Post-Treatment, which has a limited effect when applied after the onset of stress.

Gene expression

Effect of Chitosan Pre-Treatment on the expression of PIP, APX, and P5CS genes in rapeseed (Brassica Napus L.) under salinity stress

Expression of selected stress-responsive genes were evaluated in Brassica napus L. by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) with respect to chitosan priming treatment in salinity conditions. The expression levels of PIP were stimulated significantly in both roots (P < 0.05) and the shoots (P < 0.01) but more in roots with treatment duration. Chitosan priming induced APX gene expression (P < 0.01), with constant high expression on day 20 after treatment in roots and shoots. P5CS gene expression was also induced significantly (P < 0.05 for shoots, P < 0.01 for roots), showing a time increase especially in shoots. From these results, we infer the chitosan priming had promoted the expression of stress-responsive genes and thus could serve as a means to improve salinity tolerance through antioxidant defense, proline biosynthesis, and water transport in rapeseed. The evidence shows that priming chitosan can effectively modulate stress-responsive gene expression for water transport, PIP; antioxidant defense, APX; and osmolyte biosynthesis, P5CS in rapeseed plants under salinity stress. The temporality of these genes would suggest a gradual and continuous transcriptional response, which indicates the potential of chitosan as a biochemical elicitor-primer to augment stress resilience in plants.

Ascorbate peroxidase activity pre-treatment

The peroxidase activity was marked by considerable impacts of chitosan pre-treatment under salt stress condition (p < 0.01). Peroxidase activity in rapeseed plants increased significantly, reaching the highest level on day 20. Minimum activity was recorded in the control plants. Comparison between patterns of gene expression and enzyme activity showed that peroxidase gene expression increased 10 days after the last treatment. Immediately following the last treatment, peroxidase activity was also high in harvested plants. This seems to suggest that the increase in enzyme activity at this point was independent of gene expression mechanisms and probably suggests a post-transcriptional regulatory mechanism.

Ascorbate peroxidase activity post-treatment

The activity of ascorbate peroxidase was highly influenced (p < 0.05) by salt-induced stress, whereby it greatly increased the enzyme activity. There was maximum activity at the salinity of 150 mM. Chitosan application significantly influenced (p < 0.05) the value of APX activity. It had no effect at 5 mg/L and showed effects at 10 mg/L.

There was a statistically significant interaction between salt stress and chitosan. The maximum activity of the enzyme APX obtained was in plants treated with 150 mM NaCl plus 5 mg/L chitosan while the lower activity was noted in plants treated with 50 mM NaCl plus 5 mg/L chitosan. Moreover, the application of chitosan to the plant stressed with either 50 or 100 mM NaCl showed increased APX activity than the one subjected to salt stress. However, with an addition of 5 mg/L chitosan to 150 mM NaCl treatment, a higher enzyme activity was recorded as compared to salt stress alone while that with 10 mg/L reduced APX activity. From this result, it could be inferred that post-treatment with chitosan had an effect on APX activity under saline conditions, with different responses observed at different concentrations of different levels of salt. The results may suggest the likelihood of such chitosan inhibiting the oxidative stress responses in rapeseed plants under salinity stress conditions.

Pre-treatment with chitosan significantly increased peroxidase activity in rapeseed under salt stress, with the highest activity observed on day 20, independent of gene expression. Post-treatment with chitosan also enhanced ascorbate peroxidase activity, particularly at 150 mM NaCl, indicating its role in oxidative stress modulation.

Pre-treatment proline content

The analysis of variance demonstrated a statistically significant effect of chitosan Pre-Treatment on proline accumulation in canola plants at the 1% significance level (p < 0.01). In the aerial parts, proline levels remained comparable to the control on days 0 and 10 post-treatment, whereas a significant increase was observed on day 20. In contrast, root proline content exhibited a gradual increase over time, peaking on day 20. While control plants displayed higher proline levels in the aerial parts than in the roots, chitosan-treated plants exhibited a slight shift, with proline accumulation being more pronounced in the roots. Interestingly, these findings did not align with the expression pattern of the P5CS gene, which was significantly upregulated in the aerial parts compared to the roots, suggesting potential post-transcriptional or regulatory mechanisms influencing proline biosynthesis.

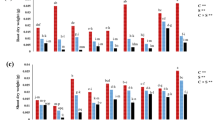

Post-treatment proline content

The results indicate that proline contents were significantly influenced by both chitosan and salt (p < 0.01). Proline tends to slightly increase as salt concentration is raised. Additionally, a significant increase in proline content was recorded as chitosan was applied to canola plants.

Effect of pre-treatment on mineral content in Brassica Napus L

The findings showed that chitosan pretreatment had highly significant effects (p < 0.01) on sodium and potassium levels in canola under salt stress. On the twentieth day post-treatment, sodium was most abundant in the roots, while the amounts in the aboveground parts were insignificant, indicating that sodium was retained in the roots as a protective mechanism. Furthermore, chitosan minimally impacted lowering Na⁺ levels in roots. In comparison, potassium levels peaked in the roots but thereafter declined gradually with time. At the level of molecular change, these changes are associated with altered expression of PIP, APX, and P5CS genes, which are important in ion transport, oxidative stress response, and phytochelatin biosynthesis, respectively. Upregulation of PIP (plasma membrane intrinsic proteins) indicates the increased regulation of water and ion transport under chitosan treatment. The increased expression of APX (ascorbate peroxidase) would also indicate improved antioxidant defense toward salt-induced oxidative damage. Induction of the P5CS (phytochelatin synthase) may also contribute to ion and metal detoxification homeostasis. This indicates that chitosan has induced both physiological changes and expression changes in genes that will improve Na⁺ and potassium (K⁺) homeostasis under salt such that it boosts the salt tolerance of canola.

Effect of post-treatment on mineral content in Brassica Napus L

The results show that Na⁺ and K⁺ concentrations in canola were significantly affected by salt, chitosan application, and their interaction. Higher salinity caused the accumulation of Na⁺ to a larger extent, being the highest at 150 mM NaCl, while K⁺ concentration reduced, indicating ionic imbalance due to salt stress. Chitosan alone suppressed Na⁺ accumulation and regulated K⁺ content, with the most efficient effect at the 10 mg/L level. Under the treatment conditions of combined salt with chitosan, chitosan limited Na⁺ uptake at intermediate salinity levels, but not at higher salinity levels, suggesting that chitosan could have a vital role in enhancing salt tolerance through regulation of Na⁺ and K⁺ homeostasis, possibly via enhanced ion selectivity and osmotic adjustment capacity.

Pre-treatment effects of salinity stress and chitosan on protein content in Brassica Napus L

The analysis of variance showed that chitosan pretreatment significantly affected the protein content of Brassica napus L. at the 1% level (p < 0.01). over time, both aerial and root tissues showed increased protein levels post-treatment. In the aerial parts, they appeared to increase more noticeably after 20 days of treatment. In roots, the increase was gradual. This indicates that chitosan appears to modulate protein accumulation under stress with separate temporal responses in various plant parts.

Post-treatment effects of salinity stress and chitosan on protein content in Brassica Napus L

This study revealed that protein content in canola plants was significantly influenced by salinity stress and the applied concentrations. There was a remarkable increase in protein levels upon salinization as compared to the control group. The effect of chitosan alone was statistically significant (p < 0.01), but its effect on protein content is limited. However, under saline stress, application of chitosan to canola plants lessened the protein increase induced by salinity. Chitosan inhibited the synthesis of stress-related proteins at all concentrations and thus can have a role in modulating protein production under salt stress. These findings highlight the complex interplay between salinity, treatment with chitosan, and protein metabolism in canola.

Comprehensive visualization of physiological and molecular responses to stress: a flower plot-based multi-parametric analysis

The flower plot was constructed to visualize the comparative analysis of different physiological and molecular parameters against a particular state or condition, with the innermost core (500) being the reference. Each petal represents one variable such as gene expression levels (PIP, APX, PCS), protein content, antioxidant enzyme activity (APX), ion concentrations (K, Na), and proline accumulation for different tissues of the plant (root, stem). The color gradient of each petal denotes relative variation, wherein red shades indicate upregulation probably in connection with stress adaptation and green shades symbolize stable or downregulated values. This visualization rather successfully shows differing metabolic adjustments under the condition of stress, implying a sophisticated regulatory network modulating tolerance in plants. With incorporation of these multiple parameter data sets within a single plot, the holistic assessment of physiological and biochemical changes, induced by stress, becomes practical, thereby rendering it a useful asset to the realms of plant stress physiology and omics (Fig. 2).

Flower diagram comparative of physiological and molecular responses of Brassica napus L. under salinity stress, along two conditions prestreatment. The central core (500) is representing reference sample while each petal is distinct for a particular parameter, as in gene expression (P5CS, APX), protein content, antioxidant activity (APX), ion concentrations (Na, K), and proline accumulation. Colour gradient symbolizes the relative changes: red for upregulation, green for downregulation or stability; useful to show major stress related metabolic adjustments (n = 3).

The flower plot comprehensively presents the physiological and molecular responses in plants under stress, with 500 as the core value base. Each petal corresponds to a different parameter, for example, gene expression levels (P5CS, APX), protein content, antioxidant enzyme activity (APX), ion concentrations (Na, K), and proline accumulation measured in various plant tissues. The color gradient of the petals shows the relative differences—that is, red shades would indicate high upregulation, particularly in the fields of proline content (31.08 mg/g FW) and P5CS expression (16.66)—implying a very significant role of these components in osmotic and stress regulation. Green colors, on the other hand, refer to lower or stable levels of expression, such as APX gene expression (0.09) and thus show a differential antioxidant response. The combination of multiple-dimensional datasets all in one form captures the total interpretation of the underlying aspect of changes in physiology and biochemistry induced by stress in plants, thus rendering valuable data into the intricate regulatory networks governing plant resilience under adverse conditions (Fig. 3).

The flower plot represents physiological and molecular responses of stress conditions. Core (500) serves as a reference, while petals include parameters such as gene expression (P5CS, APX), protein content, antioxidant activities, ion concentrations (Na, K), and proline accumulation. A color scale from red to green indicates upregulation and downregulation, respectively, of each parameter, highlighting metabolic adjustments in the Post-Treatment phase(n = 3).

Principal component analysis (PCA) of physiological and molecular responses in the pre-treatment

The PCA biplot illustrated a comprehensive visualization of variance concerning physiological and molecular responses under pre-treatment conditions with PC1 and PC2 explaining a considerable amount of total variance. Initial observations were segregated in space, indicating that control (time 0) and salt stress conditions were totally distinguished, with salt time 10 sitting toward the positive PC1 axis signifying major salinity-induced changes (Fig. 4). Nutrient-related variables, especially potassium in roots and stems, were strongly associated with the negative PC1 axis, implying a depletion under salt stress. On the other hand, gene expression markers (P5CS, PIP, APX in root and stem) and stress-responsive metabolites (proline and protein content) were located toward the positive PC1 and PC2 axes, emphasizing their upregulation as coping responses to salinity. The co-localization of enzymatic activity (APX-Root) with gene expression parameters lends extra credence to the activation of oxidative defense and osmoprotective pathways. Thus, such findings highlight salt stress-induced transcriptional and metabolic reprogramming that comprise crucial regulatory elements in salinity tolerance mechanisms (Fig. 4).

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) biplot illustrating the distribution of active variables and observations under pre-treatment conditions. The plot represents the relationships between physiological (nutrient content, protein levels, and proline accumulation) and molecular (gene expression of P5CS, PIP, and APX) parameters in response to initial salt stress exposure. Active variables (red vectors) indicate the direction and magnitude of each parameter’s contribution to principal components, while active observations (blue points) represent different experimental conditions. The clustering pattern highlights metabolic and transcriptional differences between control and salt-treated samples, providing insights into early-stage stress responses(n = 3).

Principal component analysis (PCA) of physiological and molecular responses in the post-treatment

The PCA biplot of post-treatment conditions gives an extensive portrayal of variance in physiological and molecular responses to various treatments for PC1 and PC2, accounting for an important share of total variance. The spatial arrangement of observations shows that control, chitosan, and NaCl-treated groups are visibly separated; Chitosan 10 and Chitosan 5 + NaCl 150 show the most pronounced shifts along the PC1 axis, indicating altered metabolic and transcriptional activities due to treatment. Such nutrient related variables like Na, K are highly related to NaCl treatments which are beneficial for their important role in ionic regulation under salt stress (Fig. 5). So, upregulation of gene expression markers APX, PIP, P5CS in co-treatments of chitosan-NaCl indicates activation of antioxidative and osmoprotective responses. In addition, stress-related metabolites (proline and protein level) are also brought closer to PC2, as they are considered to play a very important role in salinity adaption. Results indicated that application of chitosan, more so with NaCl co-treatment, influences greatly the physiological and molecular responses leading to improvement in the resilience to abiotic stresses by transcriptional reprogramming and metabolic adjustment (Fig. 5).

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) biplot illustrating the distribution of active variables and observations following post-treatment conditions. The plot highlights the relationships between physiological parameters (such as proline and protein content) and molecular markers (including gene expression of APX, PIP, and P5CS) in response to various treatments. Active variables (red vectors) indicate the contribution of each parameter to the principal components (PC1 and PC2), while active observations (blue points) represent different treatment conditions. The distinct clustering of treatment groups, particularly Chitosan 10 and Chitosan 5 + NaCl 150, reflects significant treatment-induced changes in metabolic and molecular responses, providing insights into stress adaptation mechanisms (n = 3).

Correlation matrix of physiological and molecular variables under pre-treatment conditions

To visualize the relationships between physiological and molecular variables regarding stress responses, the correlation coefficient plot is viewed as a gradient gradient color circle, where dark blue circles represent strong positive correlations, while dark red circles represent strong negative correlations. Statistically significant comparisons are marked with an asterisk (*) (Fig. 6). As stated, the levels of gene expression for PIP, P5CS, and APX are significantly positively correlated, suggesting a possible co-regulated transcriptional control under the imposed treatment conditions. On the contrary, enzyme activity for APX (IU/g) has a positive correlation with gene expression for APX, indicating that the two defense mechanisms have a direct joining between transcriptional and enzymatic antioxidant defense. There also exists moderate positive correlation values for Na⁺ and K⁺, reflecting their roles to play in ionic homeostasis during stress adaptation. In addition, proline level (mg/g FW) shows a strong direct relationship with both P5CS expression and APX activity, hence upholding its dual functions in osmoprotection and antioxidant defense. Also, proline accumulation (in mg/g) has been significantly positively correlated with total protein content (in mg/g), suggesting a role in adaptive metabolic responses (Fig. 6). The collective picture of such findings is that cooperative regulation of an array of antioxidative enzyme systems, osmoprotectants, and ion transport mechanisms proves crucial for stress resilience, thereby granting a molecular insight into the diverse adaptive strategies followed under different treatment conditions (Fig. 6).

Correlation coefficient plot depicting the relationships between gene expression levels (PIP, P5CS, and APX), enzymatic activity (APX IU/g), ion content (Na, K), and metabolic markers (proline and protein) in pre-treatment conditions. The correlation strength and direction are conveyed by the size and intensity of the circle color, with large dark blue circles representing strong positive correlations and dark red ones for strong negative correlations. Statistically significant correlations are denoted by asterisks (*). The seen patterns highlight the interrelationship of antioxidative defense mechanisms, osmoprotective responses, and ion homeostasis in pre-treatment conditions(n = 3).

Correlation matrix of physiological and molecular variables under post-treatment conditions

The result from correlation coefficient analysis illuminates a strong positive relationship in gene expression levels of PIP, P5CS, and APX, which implies a tightly regulated action in the control for water transport via flow into proline biosynthesis and then to antioxidative defense pathways (Fig. 7). The significant positive correlation found between APX enzymatic activity (IU/g) and APX gene expression indicated a transcriptional regulation on the enzymatic response under conditions of stress. This study also evaluates Ion homeostasis, where moderate positive correlation exists in Na⁺ and K⁺ concentrations; hence, they play vital roles in osmotic balance. So, the positive correlation between proline accumulation and P5CS gene expression indicates the significance of proline biosynthesis in stress adaptation. Furthermore, the strong positive correlation between proline content and protein amount indicates a functional link between osmoprotective mechanisms and metabolic adjustment due to treatment. Therefore, this shows that these treatments will trigger a whole-system response post-treatment regarding the co-ordinated regulation of antioxidant defenses, osmoregulatory metabolites, and ion transport-all increasing stress tolerance as well as helping to maintain physiological resilience (Fig. 7).

Correlation coefficient plot showing relationships amid gene expression levels (PIP, P5CS, APX), enzyme activities (APX IU/g), ion contents (Na, K), and metabolic markers (proline, protein) in post-treatment conditions. The bigger and more intense the color of the circle, the stronger the correlations in that particular direction, with dark blue indicating strong positive correlations and dark red, strong negative correlations. Statistically significant correlations are indicated by asterisks (*). The interrelations provided emphasize the regulatory network underlying stress adaptation concerning antioxidant responses, osmolyte accumulation, and ion homeostasis after a treatment.

Discussion

Plant growth and productivity are restricted by soil salinity as one of the potential environmental restrictions. This study has been designed to verify how chitosan affects the physiological parameters and expression level of three key genes (P5CS, PIP, and APX) in Brassica napus L. under salt stress. According to our data, the chitosan plays an enhancive role in salinity stress alleviation through increased drought resistance, osmoregulation, and intrinsic antioxidant defenses32,33. Aquaporins, encoded by PIP genes, play an essential role in water transport across membranes, and their regulation is a critical aspect of plant response to drought and salinity stress. The significant increase in PIP expression in chitosan-treated plants under salt stress observed in our study is consistent with the findings of Ibraheem et al.34,35, who reported increased expression of aquaporin genes in rice following chitosan treatment. Similarly, Stassinos et al.36 showed that PIP expression levels were significantly upregulated in Brassica napus L. cultivars subjected to high saline conditions, especially in salt-tolerant varieties. Increased osmotic water uptake provides for osmotic adjustment through proline accumulation under stress. The key enzyme in proline biosynthesis is encoded by the P5CS gene and P5CS gene expression is strongly induced by salinity stress37,38. Our results revealed higher P5CS expression in chitosan-primed plants subjected to salt stress, being in line with the observations of Cherif et al. (2020) in Rosmarinus officinalis39, where application of chitosan enhanced the levels of proline under stress. Similar results were reported by Saadat et al.40, who demonstrated upregulation of proline biosynthesis genes in chitosan-treated saline condition of common beans seeds. Again, research work by Ghorbanpour et al.41 proved that chitosan, in fact, acts to modulate the proline biosynthesis pathways in various plant species for osmotic balance and stress alleviation. The antioxidant defense system is one other factor that protects things in a salt stress environment. In this regard, the APX gene carries instructions for making the enzyme ascorbate peroxidase, a very important enzyme capable of neutralizing ROS by degrading hydrogen peroxide. Our results confirmed an appreciable enhancement of APX expression in chitosan-treated plants under salinity. In agreement with this result, Bigham Soostani et al.34 reported chitosan-induced APX upregulation in Brassica napus L. grown under salt stress. Additional Bringing more insight, Liptay and Zariffa42. found higher plants treated with chitosan. Similarly, Khan et al.43 observed increased activities of antioxidant enzymes, including APX, in chitosan-treated maize under salt stress. On the contrary, other researchers like Shahbazi et al.44, Zhou et al.45 and Mohammadi et al.46 reported variable responses that might be attributed to differences in plant species, nature of experimental conditions, or chitosan formulations. It is also worth noting that while our study focused primarily on PIP, P5CS, and APX, chitosan has been reported to influence the expression of other key genes involved in salt stress response, including NHX1, HKT1, and SOS1, which regulate ion transport and Na⁺/K⁺ homeostasis47, contributing to improved ionic balance and reduced sodium toxicity. Salinity stress significantly alters protein metabolism in plants, leading to either an increase or decrease in total protein content depending on species-specific responses and stress intensity. In the present study, salinity induced an increase in total protein content in Brassica napus L., consistent with ious reports on quinoa48 and tomato42, where protein accumulation was attributed to osmotic adjustment mechanisms. This adaptation likely involves stress-responsive proteins that mitigate cellular damage and contribute to metabolic adjustments under salinity stress. Conversely, studies on rice49 and Achillea fragratissima50 have reported a reduction in protein content under saline conditions, suggesting species-dependent differences in protein synthesis and degradation pathways.

In the present study, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and correlation matrix analysis were employed as the main statistical tools to explore the complex dataset. PCA was used to reduce the dimensionality of the data and identify the major sources of variation, thereby facilitating the interpretation of multiple physiological and biochemical parameters. The correlation matrix, on the other hand, provided an integrated overview of the relationships among the measured variables, revealing potential interactions and patterns relevant to stress responses. These approaches are widely applied in plant stress physiology for their effectiveness in capturing complex biological relationships. Furthermore, recent literature has demonstrated the role of chitosan in enhancing plant tolerance to abiotic stress by modulating physiological traits and metabolic pathways. For example, Tabassum et al.51 reported that chitosan improves antioxidant enzyme activities and mitigates oxidative damage under stress conditions. Similarly, Rafique et al.52 showed that chitosan influences the expression of stress-responsive genes, consistent with our findings. These studies support the relevance of our experimental design and highlight chitosan’s potential as a biostimulant for improving plant resilience under saline environments.

Chitosan application modulated protein accumulation, supporting its role as a bio-stimulant in enhancing stress tolerance. Pre-treatment with chitosan resulted in a significant increase in total protein content over 20 days, aligning with findings by53, who demonstrated that chitosan application in wheat increased protein levels by enhancing nitrogen assimilation and metabolic activity. This increase in protein content may be linked to the upregulation of genes involved in protein biosynthesis and stress response54, as well as the regulation of key enzymes in glycolysis and other metabolic pathways55. Additionally, the protective role of chitosan-based treatments has been reported in Vitis vinifera, where foliar application of chitosan-salicylic acid nanocomposites increased protein levels under salt stress56. The observed increase in protein content following chitosan treatment may be an adaptive response aimed at stabilizing cellular structures and maintaining metabolic homeostasis. Chitosan-induced protein accumulation could result from enhanced ribosomal activity and increased synthesis of stress-protective proteins57. Furthermore, chitosan-mediated upregulation of stress-responsive proteins in wheat58 and rice59 suggests a conserved mechanism by which chitosan enhances stress tolerance through protein metabolism. As protein synthesis plays a crucial role in cellular adaptation to abiotic stress, chitosan pre-treatment appears to be a promising approach for mitigating salinity-induced damage by sustaining protein biosynthesis and maintaining cellular function. Pre-treatment with chitosan exhibits a more pronounced effect on protein accumulation in Brassica napus L. under salinity stress compared to post-transcriptional regulation. By priming metabolic pathways before stress exposure, pre-treatment enhances protein biosynthesis, stabilizes enzymatic functions, and mitigates the detrimental effects of salinity-induced oxidative stress. In contrast, post-transcriptional mechanisms primarily modulate protein expression after stress onset, limiting their efficacy in preventing early cellular damage. These findings underscore the significance of pre-treatment strategies in reinforcing stress adaptation through the upregulation of stress-responsive proteins and the maintenance of cellular homeostasis.

Salinity stress significantly disrupts ion homeostasis in plants, primarily by increasing sodium (Na⁺) accumulation while simultaneously reducing potassium (K⁺) uptake. The results of this study indicate that exposure to 150 mM NaCl leads to a substantial increase in Na⁺ content and a corresponding decline in K⁺ levels in Brassica napus L., consistent with previous findings47,60. This imbalance is largely attributed to the antagonistic relationship between Na⁺ and K⁺, where the influx of Na⁺ through non-selective cation channels disrupts K⁺ transport, leading to impaired cellular functions61,62. The observed decline in K⁺ concentration suggests that salinity stress compromises K⁺ retention mechanisms, which are critical for enzymatic activity, osmoregulation, and photosynthetic efficiency63.

K⁺ is an essential element involved in various physiological and biochemical processes, including protein synthesis, enzyme activation, and stomatal regulation. However, under saline conditions, the high Na⁺ levels in the rhizosphere hinder K⁺ uptake by outcompeting it at the transport sites, ultimately leading to K⁺ deficiency64,65. This is in agreement with previous reports on other plant species, such as soybean66 and faba bean67, where elevated salinity resulted in a marked reduction in K⁺ content in aerial tissues. The depletion of K⁺ in salt-stressed plants has been linked to the depolarization of plasma membranes and the activation of Na⁺-permeable channels, further exacerbating ion toxicity68,69.The detrimental effects of Na⁺ accumulation on plant metabolism are further amplified by its interference with essential nutrient transport, leading to osmotic stress, oxidative damage, and metabolic dysfunction. Our findings align with earlier studies that demonstrated a decrease in K⁺/Na⁺ ratio under salt stress conditions, which is a key indicator of salt tolerance in plants70,71. The reduced K⁺ availability negatively impacts protein synthesis and ATPase activity, both of which are crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis72,73. Given the critical role of K⁺ in mitigating salt stress, strategies aimed at enhancing K⁺ uptake and retention, such as the application of K⁺ fertilizers or the development of salt-tolerant cultivars with improved K⁺ selectivity, could be effective in alleviating the adverse effects of salinity in Brassica napus L.

Based on the results, Pre-Treatment demonstrated a more substantial effect on maintaining potassium (K⁺) homeostasis and reducing sodium (Na⁺) accumulation under salinity stress. Pre-Treatment strategies, particularly with osmoprotectants or ionic regulators, enhanced the selective uptake of K⁺ while restricting Na⁺ influx, thereby mitigating ionic imbalance. In contrast, post-transcriptional regulation played a crucial role in modulating stress-responsive genes; however, its impact on immediate ion transport mechanisms was less pronounced compared to Pre-Treatment. The ability of Pre-Treatment to prime the cellular defense system before exposure to stress conditions suggests that it is a more effective strategy for sustaining ionic equilibrium and improving salt tolerance in Brassica napus L.

Conclusion

This study provides a comparative evaluation of chitosan pre-treatment and post-treatment in Brassica napus L. under salt stress, focusing on key molecular and biochemical responses. Our findings reveal that pre-treatment was more effective in enhancing stress tolerance, as evidenced by the upregulation of P5CS, PIP, and APX genes. The increased expression of P5CS in pre-treated plants correlated with higher proline accumulation, supporting osmotic adjustment and stress resilience. Similarly, elevated APX expression indicated a more robust antioxidant defense system, mitigating oxidative damage. Additionally, the enhanced expression of PIP genes in pre-treated plants suggests improved water homeostasis under saline conditions. The observed increase in total protein content further supports the role of chitosan pre-treatment in stabilizing cellular functions. Notably, pre-treated plants exhibited sustained growth even under high salinity conditions of up to 200 mM NaCl, whereas post-treated plants failed to survive at this concentration and only managed to grow at 150 mM NaCl. These findings underscore the superior efficacy of chitosan pre-treatment in enhancing salt stress tolerance in Brassica napus L., highlighting its potential application for improving crop resilience in saline environments.

Data availability

Data are provided within the manuscript information files.

References

Hariri, N., Sorkheh, K. & Nejadsadeghi, L. Aeromonas hydrophila by quorum sensing Auto-Inducers on growth amelioration, enhance salt tolerance and mechanism of encoding genes in rapeseed. Journal Plant. Growth Regulation 2025:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-025-11656-0

Das, S. et al. Phytohormonal signaling in plant resilience: advances and strategies for enhancing abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Growth Regulation 2025:1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-025-01279-6

Muhammad, M. et al. Navigating climate change: exploring the dynamics between plant–Soil microbiomes and their impact on plant growth and productivity. Glob. Change Biol. 31 (2), e70057. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.70057 (2025).

Hameed, A. et al. Effects of salinity stress on Chloroplast structure and function. Cells 10 (8), 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10082023 (2021).

Zhang, D., Zhang, Y., Sun, L., Dai, J. & Dong, H. Mitigating salinity stress and improving cotton productivity with agronomic practices. Agronomy 13 (10), 2486. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13102486 (2023).

Chaffai, R., Ganesan, M. & Cherif, A. Abiotic stress in plants: challenges and strategies for enhancing plant growth and development. In: Plant Adaptation To Abiotic Stress: from Signaling Pathways and Microbiomes To Molecular Mechanisms. Springer; : 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-0672-3_1 (2024).

Gatti, N. et al. Biochemical and biomolecular response of Arabidopsis seedlings to osmotic and salt stress: mitigation by biostimulant formulation enriched in betalain degradation products. Curr. Plant. Biology. 41, 100438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpb.2025.100438 (2025).

Dolu, H., Killi, D., Bas, S., Bilecen, D. S. & Seymen, M. Effectiveness of salt priming and plant growth-promoting bacteria in mitigating salt-induced photosynthetic damage in melon. Photosynth. Res. 163 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-024-01128-z (2025).

Singh, N. et al. Salt stress and its eco-friendly management using biostimulants in grain legumes: a review. Discover Agric. 3 (1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44279-024-00150-y (2025).

Lindberg, S. & Premkumar, A. Ion changes and signaling under salt stress in wheat and other important crops. Plants 13 (1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13010046 (2023).

Hussain, S. et al. Recent progress in Understanding salinity tolerance in plants: story of Na+/K + balance and beyond. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 160, 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.01.029 (2021).

Rahman, M. M. et al. Green vanguards: Harnessing the power of plant antioxidants, signal catalysts, and genetic engineering to combat reactive oxygen species under multiple abiotic stresses. Plant Stress 2024:100547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2024.100547

Singh, D. Juggling with reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense system–A coping mechanism under salt stress. Plant. Stress. 5, 100093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2022.100093 (2022).

Abdulraheem, M. I. et al. Mechanisms of plant epigenetic regulation in response to plant stress: recent discoveries and implications. Plants 13 (2), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13020163 (2024).

Das, A., Ghosh, S. & Pramanik, N. Chitosan biopolymer nanocomposites for agriculture applications. In: Biopolymeric Nanoparticles for Agricultural Applications. Springer; : 209–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-68834-8_8 (2024).

Sree Rayanoothala, P., Dweh, T. J., Mahapatra, S. & Kayastha, S. Unveiling the protective role of Chitosan in plant defense: A comprehensive review with emphasis on abiotic stress management. Crop Design 2024:100076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropd.2024.100076

Balusamy, S. R. et al. Chitosan, Chitosan nanoparticles and modified Chitosan biomaterials, a potential tool to combat salinity stress in plants. Carbohydr. Polym. 284, 119189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119189 (2022).

Tsivileva, O. Selenium-Containing nanoformulations capable of alleviating abiotic stress in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26 (4), 1697. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26041697 (2025).

Sari, S. A., Muchlas, M., Lee, B-R., Al Mamun, M. & Kim, T-H. Sodium hydrosulfide enhances drought tolerance by alleviating oxidative stress and promoting proline accumulation in brassica Napus L. J. Korean Soc. Grassland Forage Sci. 44 (3), 204–209. https://doi.org/10.5333/KGFS.2024.44.3.204 (2024).

Bigham Soostani, S., Ranjbar, M., Memarian, A., Mohammadi, M. & Yaghini, Z. Regulation of APX, SOD, and PAL genes by chitosan under salt stress in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). BMC Plant Biol. 25(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-06815-0 (2025).

Huang, Z. et al. A modified method of total RNA isolation for Mango leaf tissues. Bioscience Methods. 14. https://doi.org/10.5376/bm.2023.14.0001 (2023).

Vennapusa, A. R., Somayanda, I. M., Doherty, C. J. & Jagadish, S. K. A universal method for high-quality RNA extraction from plant tissues rich in starch, proteins and fiber. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 16887. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73958-5 (2020).

Channuntapipat, C. et al. Identification of incompatibility genotypes in almond (Prunus dulcis Mill.) using specific primers based on the introns of the S-alleles. Plant. Breed. 122 (2), 164–168. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0523.2003.00842.x (2003).

Zhanassova, K. et al. ROS status and antioxidant enzyme activities in response to combined temperature and drought stresses in barley. Acta Physiol. Plant. 43, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-021-03281-7 (2021).

Mushtaq, Z. et al. Changes in growth, photosynthetic pigments, cell viability, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant defense system in two varieties of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) subjected to salinity stress. Phyton 91 (1), 149. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2022.016231 (2022).

Špoljarević, M. et al. The relationship of proline content and metabolism on the productivity of maize plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 6 (2), 251–257. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.6.2.14336 (2011).

Abbaspour, J. & Ehsanpour, A. A. Sequential expression of key genes in proline, Glycine betaine and Artemisinin biosynthesis of Artemisia aucheri Boiss using Salicylic acid under in vitro osmotic stress. Biologia 75 (9), 1251–1263. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11756-020-00507-w (2020).

Nakano, Y. & Asada, K. Purification of ascorbate peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts; its inactivation in ascorbate-depleted medium and reactivation by monodehydroascorbate radical. Plant Cell Physiol. 28 (1), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a077268 (1987).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72 (1–2), 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 (1976).

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. & Teare, I. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant. Soil. 39, 205–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00018060 (1973).

Reeves, R., Baker, A., Borhidi, A. & Berazain, R. Nickel hyperaccumulation in the serpentine flora of Cuba. Ann. Botany. 83 (1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1998.0786 (1999).

El-Komy, M. S. et al. Spatiotemporal variations affect DTPA-Extractable heavy metals in coastal Salt-Affected soils of arid regions. Soil. Syst. 9 (1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems9010026 (2025).

Santangeli, M., Capo, C., Beninati, S., Pietrini, F. & Forni, C. Gradual exposure to salinity improves tolerance to salt stress in rapeseed (Brassica Napus L). Water 11 (8), 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11081667 (2019).

BighamSoostani, S., Ranjbar, M., Memarian, A., Mohammadi, M. & Yaghini, Z. Investigating the effect of Chitosan on the expression of P5CS, PIP, and PAL genes in rapeseed (Brassica Napus L.) under salt stress. BMC Plant Biol. 25 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-06187-5 (2025).

Zhu, Z. H. et al. Effects of seed priming treatments on the germination and development of two rapeseed (Brassica Napus L.) varieties under the co-influence of low temperature and drought. Plos One. 16 (9), e0257236. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257236 (2021).

Hidangmayum, A., Dwivedi, P., Kumar, P. & Upadhyay, S. K. Seed priming and foliar application of Chitosan ameliorate drought stress responses in Mungbean genotypes through modulation of morpho-physiological attributes and increased antioxidative defense mechanism. J. Plant Growth Regul. 42 (10), 6137–6154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-022-10792-1 (2023).

Stassinos, P. M. et al. Enhancement of brassica Napus tolerance to high saline conditions by seed priming. Plants 10 (2), 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020403 (2021).

Abdelkader, A. F. et al. Expression of aquaporin gene (Os PIP1-3) in salt-stressed rice (Oryzasativa L.) plants pre-treated with the neurotransmitter (dopamine). Plant Omics 5(6):532–541. (2012). https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=e885ecc0a5e95b19ef919e941b61fb164caad540

Raza, A. et al. Assessment of proline function in higher plants under extreme temperatures. Plant Biol. 25 (3), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.13510 (2023).

Maghsoudi, K., Emam, Y., Niazi, A., Pessarakli, M. & Arvin, M. J. P5CS expression level and proline accumulation in the sensitive and tolerant wheat cultivars under control and drought stress conditions in the presence/absence of silicon and Salicylic acid. J. Plant Interact. 13 (1), 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/17429145.2018.1506516 (2018).

El-Esawi, M. A. et al. Salicylic acid-regulated antioxidant mechanisms and gene expression enhance Rosemary performance under saline conditions. Front. Physiol. 8, 716. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00716 (2017).

Liptay, A. & Zariffa, N. Testing the morphological aspects of polyethylene glycol-primed tomato seeds with proportional odds analysis. (1993). https://doi.org/10.5555/19940301815

Khan, R. et al. Exogenous application of Chitosan and humic acid effects on plant growth and yield of pea (Pisum sativum). Int. J. Biosci. 12 (5), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.12692/ijb/12.5.43-49 (2018).

Shahbazi, E., Arzani, A. & Saeidi, G. Effects of NaCl treatments on seed germination and antioxidant activity of Canola (Brassica Napus L.) cultivars. Bangladesh J. Bot. 40 (1), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.3329/bjb.v40i1.8000 (2011).

Zhou, H. et al. Genome-wide analysis of ascorbate peroxidase and functional characterization of SpAPX249b and SpAPX285c for salt tolerance in sesuvium portulacastrum L. Plant Cell Rep. 44 (4), 83. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-5336710/v1 (2025).

Mohammadi, V. et al. Unraveling the role of autophagy and antioxidants in anther and pistil responses to heat stress in rapeseed (Brassica Napus L). Plant Cell Rep. 44 (2), 51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-025-03437-6 (2025).

James, R. A. et al. Photosynthetic capacity is related to the cellular and subcellular partitioning of Na+, K + and Cl-in salt‐affected barley and durum wheat. Plant. Cell. Environ. 29 (12), 2185–2197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01592.x (2006).

Koyro, H-W. & Eisa, S. S. Effect of salinity on composition, viability and germination of seeds of Chenopodium Quinoa willd. Plant. Soil. 302, 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-007-9457-4 (2008).

Kawasaki, S. et al. Gene expression profiles during the initial phase of salt stress in rice. Plant. Cell. 13 (4), 889–905. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.13.4.889 (2001).

Abd, E. L. & Ahmed, S. T. Effect of salinity and cutting date on growth and chemical constituents of Achillea fragratissima forssk, under Ras Sudr conditions. Res. J. Agr Biol. Sci. 5 (6), 1121–1129. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92050-0_14 (2009).

Tabassum, M. et al. Chitosan modulated antioxidant activity, inorganic ions homeostasis and endogenous melatonin to improve yield of Pisum sativum L. accessions under salt stress. Sci. Hort. 323, 112509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112509 (2024).

Rafique, M. et al. Mitigation of adverse effect of cadmium toxicity in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) through foliar application of Chitosan and spermidine. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 9062. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93672-4 (2025).

Sadak, M. S. & Talaat, I. M. Attenuation of negative effects of saline stress in wheat plant by Chitosan and calcium carbonate. Bull. Natl. Res. Centre. 45, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-021-00596-w (2021).

Landi, L. et al. Global transcriptome analysis and identification of differentially expressed genes in strawberry after preharvest application of benzothiadiazole and Chitosan. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 235. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00235 (2017).

Attia, M. S. et al. Impact of foliar application of Chitosan dissolved in different organic acids on isozymes, protein patterns and physio-biochemical characteristics of tomato grown under salinity stress. Plants 10 (2), 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020388 (2021).

Aazami, M. A., Maleki, M., Rasouli, F. & Gohari, G. Protective effects of Chitosan based Salicylic acid nanocomposite (CS-SA NCs) in grape (Vitis vinifera cv.‘Sultana’) under salinity stress. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 883. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-27618-z (2023).

Rabêlo, V. M. et al. Santos Filho prds, Souza tcd: the foliar application of a mixture of semisynthetic Chitosan derivatives induces tolerance to water deficit in maize, improving the antioxidant system and increasing photosynthesis and grain yield. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 8164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44649-7 (2019).

Farooq, T., Akram, M. N., Hameed, A., Ahmed, T. & Hameed, A. Nanopriming-mediated memory imprints reduce salt toxicity in wheat seedlings by modulating physiobiochemical attributes. BMC Plant Biol. 22 (1), 540. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93672-4 (2022).

Martínez González, L., Reyes Guerrero, Y., Falcón Rodríguez, A. & Núñez Vázquez, M. Effect of seed treatment with Chitosan on the growth of rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings cv. INCA LP-5 in saline medium. (2015). https://doi.org/10.5555/20153178959

Ashraf, M. & McNeilly, T. Salinity tolerance in brassica oilseeds. CRC. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 23 (2), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352680490433286 (2004).

Blumwald, E. Sodium transport and salt tolerance in plants. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12 (4), 431–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00112-5 (2000).

Turan, C. & Oral, M. A computer package program for morphometric identifications of fish populations: MorFISH. In: ITAFE’05-International congress on information technologies in agriculture, Food and Environment, Cukurova University, Adana, Turkey, October: 2005. 12–14. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.3338.2404

Lu, M. et al. Boron-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism, Na+/K + homeostasis and antioxidant defense mechanisms in salt-stressed soybean seedlings. J. Hazard. Mater. 138036 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.138036 (2025).

Appiah, E. A., Balla-Kovács, A., Ocwa, A., Csajbók, J. & Kutasy, E. Enhancing alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) productivity: exploring the significance of potassium nutrition. Agronomy 14 (8), 1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14081806 (2024).

Ates, E. & Tekeli, A. Salinity tolerance of Persian clover (Trifolium resupinatum var. Majus Boiss.) lines at germination and seedling stage. (2007). https://doi.org/10.5555/20073155966

Ning LiHua, N. L., Kan GuiZhen, K. G., Shao HongBo, S. H. & Yu DeYue, Y. D. Physiological and transcriptional responses to salt stress in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.) seedlings. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3005

Zeid, I. Effect of arginine and Urea on polyamines content and growth of bean under salinity stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 31, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-008-0201-3 (2009).

Song, X. et al. Physiological and molecular mechanisms of exogenous Salicylic acid in enhancing salt tolerance in tobacco seedlings by regulating antioxidant defence system and gene expression. Front. Plant Sci. 16, 1545865. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2025.1545865 (2025).

Joshi, S., Nath, J., Singh, A. K., Pareek, A. & Joshi, R. Ion transporters and their regulatory signal transduction mechanisms for salinity tolerance in plants. Physiol. Plant. 174 (3), e13702. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.13702 (2022).

Davodipour, M., Jalali, M. & RajiMR Effect of different light spectra on morpho-physiological and biochemical characteristics of marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) under salinity stress. J. Plant. Process. Function. 13 (64), 87–96. http://dx.doi.org/DOI:%2010.22034/13.64.87 (2025).

Kaya, M. G. et al. Protective effects of nebivolol against anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy: a randomized control study. Int. J. Cardiol. 167 (5), 2306–2310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.023 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. Oxidative stress-induced changes in wooden breast and mitigation strategies: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 24 (2), e70148. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.70148 (2025).

Clausen, M. J. V. & Poulsen, H. Sodium/potassium homeostasis in the cell. Metallomics Cell 2013:41–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_3

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The research project that resulted in this article was not funded or supported by any external organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sarvenaz Bigham Soostani (S.B.) and Monireh Ranjbar (M.R.) contributed equally to the conceptualization, design, and supervision of the research.Amir Memarian (A.M.), Mozhdeh Afshari (M.A.), and Mehrnoosh Mohammadi (M.M.) carried out the laboratory experiments and data collection collaboratively.S.B. conducted data analysis and drafted the initial manuscript.M.R. reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bigham Soostani, S., Ranjbar, M., Memarian, A. et al. Chitosan pre- and post-treatment modulates molecular and physiological responses to salinity in Brassica Napus L. Sci Rep 15, 28219 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13996-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13996-z