Abstract

This study evaluated the mechanical and anti-bacterial properties of photocurable clear aligner resin (TC-85) incorporated with zwitterionic material, 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC). Three experimental solutions were synthesized using 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC) and clear aligner resin (TC-85). A group without any experimental solution served as a control. Specimens were fabricated by adding mixture of solutions to customized mold followed by post-curing procedure. Mechanical properties of the experimental groups were evaluated by tensile strength test, three-point flexural test, stress relaxation and creep test. Biological properties were evaluated through colony forming unit assay, MTT assay, and protein adsorption test. Incorporation of MPC into clear aligner resin achieved protein repellent and anti-microbial capabilities without compromising the mechanical properties. Tensile strength and three-point flexural test along with creep, stress relaxation test did not show significant difference in the mechanical properties. Addition of 1%, 2%, or 3% MPC into clear aligner resin significantly reduced the amount of bovine serum albumin adsorbed and proteins adsorbed from brain heart infusion medium by 1/3 ~ 1/4 that of a control (p < 0.001). The mixture of clear aligner resin with 3% MPC inhibited biofilm growth, reducing CFU counts by 40% compared to that of a control. Incorporating zwitterionic material with clear aligner resin TC-85 demonstrated an anti-biofouling activity while preserving its original mechanical properties, which may be a promising strategy to overcome the limitation of current clear aligner treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clear aligner treatment gained popularity among orthodontists and patients due to their advantages in aesthetics, convenience, and improved oral hygiene compared to traditional orthodontic treatment1,2. Recently, physical properties such as static mechanical properties and dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) of a newly developed direct printing clear aligner material, TC-85 were compared with conventional vacuum thermoforming material PET-G3,4,5. It has been reported that directly 3D printed clear aligners generate more consistent and lighter force which enable optimal force application for tooth movement than conventional thermoformed materials (PET-G)6. Additionally, directly printed clear aligner allows easier integration of various design elements into application, increasing its versatility. Nevertheless, during orthodontic treatment patients with orthodontic appliances often struggle to maintain proper oral hygiene, leading some to develop early caries lesion or white spot lesions (WSLs)7.

Proteins in saliva adhere to dental restorations leading to an initial step of biofilm formation, which eventually changes the local balance of microbial community8,9,10. Early lesions in enamel are initial sites for acid penetration by lactic acid produced by bacterial biofilm. Accordingly, there is a great need to develop methods that can repel proteins which could further inhibit bacterial adherence and enhance antibacterial property1,2. Various attempts have been made to develop antibacterial acrylate resins with sufficient mechanical strength, protein-repellent and anti-microbial properties11,12,13,14,15,16.

As a newly approached preventive strategy, incorporating zwitterions have demonstrated significant potential as biocompatible antifouling material on various dental applications17,18. Zwitterionic materials contain both cationic and anionic functional groups. Due to their molecular structure with phospholipid polar group in its side chain, applying zwitterionic materials function as additives for protein adsorption and cell adhesion18,19,20,21,22,23. These hydrophilic polymers reduce protein adsorption, resulting in reduced bacterial adhesion and dental biofilm formation20.

Among zwitterionic materials, 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC) is widely studied by incorporating it with dental adhesives, orthodontic cements, and resin composites due to its protein repellent and antibacterial property17,24,25,26,27,28. Several studies on MPC showed excellent protein repellent activity and bacterial adhesion prevention.

Previous studies have highlighted the impact on mechanical properties, noting its well-known biocompatibility when incorporated with other materials17,21,29,30. Recently, a study demonstrated that mixing MPC with PMMA 3D printing dental resins provided similar antifouling effect and minimal compromise in mechanical integrity from 3 to 5 wt%18. Kwon et al. demonstrated that light curable fluoride varnish (LCFV) with MPC exhibited significant antifouling effect on protein adsorption and bacterial adhesion, while preserving its original physical properties31. These results suggest the potential for developing a new protein-repellent direct 3D printing clear aligner with antibacterial properties which can inhibit biofilm formation through mixing MPC and photocurable printing clear aligner resin.

However, thus far, there are few reports to date on the incorporation of MPC polymer with newly approved photocurable clear aligner resin TC-85.

This study is to evaluate the antibacterial properties as well as mechanical performances of TC-85, a newly introduced photocurable resin intended for use in directly 3D printed clear aligners, incorporated with MPC polymer. The incorporation of zwitterionic material, 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC) was intended to have biocompatible anti-fouling ability. For comparative evaluation, TC-85 was selected as control. The null hypotheses were that there will be no significant differences between clear aligner resin with or without MPC in terms of (i) physical and mechanical properties, and (ii) oral biofilm resistance.

Results

Mechanical properties

Tensile strength test

As summarized in Table 1, TC-85 control showed 33.80 MPa stress (strain of 1.35%), while MPC 1% showed 27.31 MPa (1.38% strain), MPC 2% showed 33.57 MPa (1.14% strain), and MPC 3% 44.20 MPa (1.35% strain) respectively. TC-85 control fractured at an elongation of approximately 17.34%, while MPC 1% (9.31%), MPC 2% (2.26%), MPC 3% (4.51%) groups fractured at even lower elongations.

According to the elastic modulus (mean ± standard deviation) results summarized in Fig. 1, control (317.06 ± 158.91 N/mm2) and MPC 1% (311.35 ± 173.13 N/mm2) group showed statistically no significance. MPC 2% (490.97 ± 96.76 N/mm2) and MPC 3% (438.61 ± 73.56 N/mm2) groups showed significantly higher results than control group (p < 0.01). MPC 2% and MPC 3% group revealed no significance among comparison. Meanwhile, MPC 2% showed the highest elastic modulus (p < 0.001) indicating a significant increase in stiffness.

Elastic moduli (M/mm2, mean ± SD) of the experimental groups (n = 45). The horizontal line within each box represents the mean value of the dataset. Data points outside the whiskers, representing statistical outliers beyond the interquartile range, are shown as individual dots. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences by post-hoc Tukey’s test. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 for comparisons between control group with and without the zwitterion analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The results show a significant increase in elastic modulus in Group 2 and 3 (p < 0.001).

Three-point flexural test

The average flexural strength of each experimental groups is as follow: control group (31.26 ± 17.41) MPa, MPC 1% group (28.96 ± 20.05) MPa, MPC 2% group (22.92 ± 10.31) MPa, and MPC 3% group (46.85 ± 32.47) MPa in Fig. 2. The flexural strength showed significant differences among groups (P < 0.001). The MPC 3% group showed significance with control group (p < 0.01), MPC 1% (p < 0.001), and MPC 2% (p < 0.001). There was no significance among control, MPC 1%, and MPC 2% groups.

Flexural moduli (N/mm2, mean ± SD) of experimental groups (n = 45). The horizontal line within each box represents the mean value of the dataset. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences by post-hoc Tukey’s test. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 for comparisons between control group with and without the zwitterion analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The results showed a significantly higher value in Group 2 among all groups (p < 0.001).

The flexural modulus showed significant differences among groups (P < 0.01). MPC 1% group (3280.68 ± 2263.54 N/mm2) showed significantly higher value among all groups. The control group (1084.42 ± 881.52 N/mm2) group revealed no significance with MPC 2% (943.37 ± 1259.05 N/mm2) and MPC 3% (1765.04 ± 1462.43 N/mm2) group.

Thermo-mechanical cycle property test (stress relaxation and creep test)

Supplementary Fig. 1 shows stress relaxation curves for four experimental groups. Each graph plots stress (kPa) against time (min), presenting the relaxation behavior of a material under constant strain. Initial stress values in all groups were slightly above 1 MPa. All experimental groups showed a rapid decrease in stress within 20 min with similar patterns. Stress level stabilized eventually. As concentration of MPC increased, final stabilization stress decreased. However, the incorporation of MPC did not show significant difference in the viscoelastic properties of the material in terms of stress relaxation.

As shown in supplementary Fig. 2, the creep value for all groups did not show significant difference, while MPC 1%, 2%,3% showing slightly higher value compared to control. The addition of MPC resulted in a small increase but not significant difference in creep value, suggesting that the material deformation under sustained stress is slightly higher with MPC. All experimental groups exhibited similar creep behavior, which suggests that the inclusion of MPC does not significantly alter creep properties.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis

Figure 3 illustrates a representative FT-IR spectrum of all experimental groups. The spectrum shows the characteristic bands of OH (3380 cm−1), NH(3330 and 1528 cm−1), CH (2937,2858,1456, 1369, 924, 775 cm−1), C=O (1715 and 1695 cm−1), CN (1528 and 1307 cm−1), C(O)OC (1235,1159, and 1102 cm−1) and COC (1032 cm−1) groups, which comply with polyester-urethane polymer structure as mentioned in previous study2. Spectrum range of 1800–1550 cm−1 represented ester groups in hydrogen bonded (amide C=O, 1690 cm−1) and freely vibrating states (C=O, 1720 cm−1) with residual C=C (1640 cm−1). Aromatic groups were not detected which indicate that TC-85 is an aliphatic vinyl functionalized polyester-urethane material, possibly functionalized with methacrylate. The FTIR spectra of all experimental groups exhibited similar overall peak patterns, with no distinct MPC specific peaks clearly distinguishable from the TC-85 resin matrix. This is likely due to the relatively low MPC concentrations (1–3 wt%) and potential spectral overlap with the functional groups of the polyester-urethane backbone of the TC-85 resin. Additionally, the relative intensity ratios of the methacrylate C=C peak at 1634 cm−1 and ester C=O peak at 1720 cm−1 was evaluated. A slight decrease in the C=C peak intensity was observed with increasing MPC concentration, suggesting partial consumption of double bonds and potential chemical integration of MPC into the polymer matrix.

Biological properties

Colony-forming unit assay

Quantitative analysis of CFU counts of all experimental groups is summarized in Fig. 4. The control group (3.20 × 106 ± 2.87 × 105) showed significantly higher value compared to MPC included groups; MPC 1% (2.79 × 106 ± 6.21 × 105), MPC 2% (2.24 × 106 ± 3.67 × 105), MPC 3% (1.32 × 106 ± 1.67 × 105). As MPC concentration increased, the CFU counts gradually decreased, respectively. The results indicate less bacterial attachment on MPC 3% group than on control. Statistically, there was significant difference between groups (F-value: 12.49, p-value: 0.0022 < 0.05).

Colony-forming unit (CFU) counts derived from S. mutans cells attached to the surfaces of control and MPC group (n = 24). The horizontal line within each box represents the mean value of the dataset. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences by post-hoc Tukey’s test. The CFU counts gradually decreased as MPC concentration increased (p < 0.05).

MTT assay

The results of MTT assay in 100 µL solution are summarized in Fig. 5. One-way ANOVA revealed significant variance in 100 µL solution (p < 0.01). According to the post-hoc analysis, control group (0.36 ± 0.07) showed significantly higher absorbance at 540 nm compared to groups with MPC. The absorbance increased as MPC concentration increased (MPC 1% (0.17 ± 0.06), MPC 2% (0.18 ± 0.10), MPC 3% (0.19 ± 0.06)), however showed no significance among experimental groups.

MTT assay result of experimental groups in 100µL (n = 24) solution. The horizontal line within each box represents the mean value of the dataset. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences by post-hoc Tukey’s test. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 for comparisons between control group with and without the zwitterion analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Group 1 showed a significantly higher absorbance compared to Group 2,3 and 4 (p < 0.01).

Protein adsorption test

As shown in Fig. 6, significant reduction in the BSA adsorption on experimental groups was evident compared to that of the control (p < 0.001). Similar tendency was observed with protein from BHI medium, but there was no significant difference between MPC 2% and MPC 3%.

Comparison of optical density (OD) adsorbed bovine serum albumin (BSA) and protein adsorbed from the brain heart infusion (BHI) medium of samples before (control) and after applying MPC (n = 24). Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences by post-hoc Turkey’s test. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 for comparisons between TC-85 with and without zwitterion analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Discussion

There have been several efforts to incorporate antibacterial and anti-biofouling features into dental products17,18,19,21,22,23,28,29,30,31,32. The longevity of the additives introduced has often been in doubt, and the materials demonstrated insufficient mechanical durability for extended use. Until now, MPC has largely been applied to dental composites and in dentin bonding systems, mostly to prevent recurrent decay caused by leakage between tooth and resin restoratives. This study, however, is one of the few that investigates the addition of zwitterionic substances such as MPC to clear aligner polymers. Therefore, this study focused on creating a new formulation for clear aligner materials that could inhibit the formation of biofilms from human saliva, while preserving the mechanical characteristics of the original clear aligner resin.

The first null hypothesis proposed that applying MPC would not cause notable variations in the mechanical properties of the clear aligner resin. This hypothesis was partially validated. The findings indicated no significant variation in creep and stress relaxation following the addition of MPC. However, we did not observe a clear correlation between the amount of MPC added to clear aligner resin and the mechanical strength or elastic modulus. This non-linearity implies that beyond certain thresholds, additive dispersion, interfacial compatibility, and polymer integration may play a more critical role than concentration alone.

Previous study has shown that applying a large amount of zwitterion can negatively impact mechanical properties33. This may be due to the material gelation at higher zwitterion concentrations, which disrupts the graft polymerization process between the zwitterions and clear aligner resin33,34. Prior studies found that concentrations above 5 wt% caused a decline in mechanical properties, while concentrations below 3 wt% were less effective in providing protein-repellent and in biofilm resistance28,31,35,36. Zhang et al. emphasized that at MPC concentrations up to 3 wt%, the mechanical properties were similar to that of the Bis-GMA control17,29. Similarly, Lee et al. demonstrated that incorporating MPC with commercial surface pre-reacted glass ionomer filler (SPRG) at concentrations between 1.5 and 5 wt% provided adequate anti-biofouling and mechanical properties, whereas exceeding 5 wt% reduced flexural strength due to increased wettability and water solubility30. In a study that incorporated MPC with mesoporous bioactive glass nanoparticles (MBN), MPC concentration exceeding 5 wt% resulted in significant reduction in mechanical properties and protein repellent activity due to gelatinization of polymer with increase in affinity to moisture21. This again highlights that excessive hydrophilicity can destabilize polymer networks, promoting water-induced degradation or plasticization. The results of our study partially aligned with the previous study, which expected that applying MPC would result in a decline in its flexural strength and elastic modulus18. Although the overall trend matched prior observations, the degree of variation across different MPC concentrations suggests a more complex interaction between composition and mechanical outcomes. The average tensile strength and flexural strength showed a decline in its value with the addition of MPC. However, the addition of 3 wt% of MPC showed the highest tensile strength and flexural strength among all experimental groups. Also, elastic modulus showed significant difference in 2 and 3 wt% MPC compared to control, while flexural modulus showed significance only with the addition of 3 wt% of MPC. The outcomes of the current flexural test come in agreement with a previous study37. The low flexural force of TC-85, in contrast to conventional thermoformed materials, is more compatible with orthodontic tooth movement, since orthodontic forces ranging from 0.1 to 1.2 N are recommended. Moreover, due to shape memory characteristic of TC-85, the aligners can consistently exert orthodontic forces on teeth with no force decay. It is known that compared to conventional thermoforming materials, TC-85 shows significantly lower peak forces38,39,40.

The mechanical properties were expected to decrease with the addition of MPC in a previous study18. However, in this study, statistically no significance in mechanical properties was observed according to MPC concentration, and no distinct linear or consistency was evident. The lack of clear dose–response correlation in mechanical properties is presumed to result from a combination of several complex factors inherent to polymer-additive interactions. First, despite standardized mixing protocols, achieving perfectly uniform distribution of MPC within the polymer network remains challenging, particularly at higher concentrations where aggregation may occur. If the homogeneity of the mixture between MPC and resin matrix is not sufficiently achieved, agglomeration of gelation may partially occur, leading to an uneven internal structure within the specimens41,42. This potential heterogeneity in MPC distribution within the polymer network may increase the standard deviation between individual specimens and contribute to unpredictable variations in physical properties. In addition, the cationic and anionic functional groups of MPC molecules may interact with the polyurethane-based resin matrix, potentially altering the local graft density. Such chemical interactions may not increase proportionately according to concentration but may occur only above a certain threshold concentration or may vary depending on the dispersion state, preventing the mechanical property changes from following a linear pattern. Variations in the polymerization process may also be an important factor. The degree of conversion of 3D printing photopolymer resin is influenced even by minor differences in UV exposure conditions such as exposure time, wavelength, energy intensity and post-curing process43. As the MPC concentration increases, physical property changes are accompanied by increased viscosity or reduced light transmittance, potentially leading to variations in the polymerization kinetics among specimens44. As a result, the measured mechanical properties may be irregularly distributed even within the same concentration group. However, quantitative degree of conversion measurements would be required to substantiate this hypothesis and establish definitive relationships between MPC concentration, curing efficiency, and mechanical properties. Other factors, such as thickness variations, surface defects arising from specimen fabrication process, the sensitivity of measurement equipment, and the limitation in the number of specimens, may also influence as variables affecting the experimental results. Ultimately, the absence of a clear correlation in mechanical strength according to MPC concentration is presumed to be due to the combined interaction of multiple factors mentioned above. Despite this variation, the primary objective of maintaining mechanical integrity while achieving significant antibacterial properties was successfully demonstrated, which showed balance between bioactivity and structural integrity. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing zwitterionic additive concentration not only for bio-functional performance but also for maintaining material consistency. Further studies should investigate the phase behavior and dispersion dynamics of MPC within the resin matrix, particularly at higher loadings, to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the observed mechanical variability. Additionally, in situ monitoring of polymerization kinetics and network heterogeneity may provide valuable insights into how zwitterionic content influences both structural and biological outcomes in advanced dental materials.

The second null hypothesis proposed that there would be no notable difference in the resistance to oral biofilm formation between clear aligner resin with or without MPC. However, this hypothesis was rejected as clear aligner resin containing MPC significantly reduced protein adsorption (Fig. 4)45.

In this study, a significant reduction in the adsorption of BSA and proteins in BHI medium was observed (Fig. 6). Prior study has shown that the attachment and adsorption of proteins derived from saliva is a crucial first step in the interaction between oral biofilm and materials within oral cavities46. Zwitterionic materials, which possess polar side chain groups, resemble the structure of cell membrane lipid bilayers with hydrophilic heads and hydrophobic tails47. In oral environment, interaction between water and zwitterionic molecules results in an abundance of free water surrounding the zwitterions, which prevent protein adhesion from saliva48. In aqueous environments, phospholipids align themselves in a bilayer with their hydrophobic tails inward and their hydrophilic heads facing outward, allowing interaction with water. Therefore, MPC polymers with highly hydrophilic surfaces limit protein adsorption and reduce bacterial adhesion. The protein adsorption assay results support that application of MPC significantly decreases protein binding.

It can be assumed that increasing the proportion of MPC in the resin would enhance its ability to repel proteins. In fact, this study found that raising MPC concentration from 0 to 3 wt% in the resin composite significantly lowered protein adsorption (Fig. 6). The protein repellent properties of the resin with MPC suggest that it may also effectively reduce biofilm formation. Indeed, the results shown in Figs. 4 and 5 demonstrated that applying 3 wt% MPC to clear aligner resin significantly decreased bacterial adhesion and lowered CFU counts.

Previous studies have shown that polymerizing MPC with resin polymers provides a durable and stable barrier against protein attachment17,49. However, in a study conducted by Kwon31, using high concentration of MPC, such as 20 wt%, significantly increased protein adsorption. It has been noted that higher MPC concentrations improved protein repellent properties, while excessive amounts of MPC results in gelation, which disturbs polymerization, leading to significant decrease in its protein-repelling performance41,42.

In the issue of balance between mechanical and antibacterial characteristics, new protein-repellent resin must also maintain sufficient mechanical strength. The optimal concentration for effective anti-biofouling while preserving the mechanical characteristics of clear aligner resin was found to be 3 wt% of MPC31. In this study, the incorporation of up to 3 wt% MPC into clear aligner resin did not significantly weaken the resin strength. This finding coincides with the prior literature which reported that MPC concentrations ranging from 0 to 3% resulted in beneficial protein-repellent property without compromising the mechanical characteristics 17. Previous study showed that mechanical properties declined when MPC concentrations reached 4.5 and 6 wt%17. Further research should explore how water absorption carries with different MPC mass fractions and whether the reduction in mechanical strength at concentrations below 4.5 wt% is due to increased water uptake by the composite17. Despite this, the current study demonstrated that using 3 wt% MPC concentration can maximize protein repellent efficacy without substantially affecting mechanical strength. As examined in the previous study of Zhang et al.17, the strength and elastic modulus of composite resin containing 3 wt% MPC were comparable to those of composites without MPC. This suggests that effective protein-repellent properties can be achieved without comprising load-bearing capacity. Therefore, incorporation of MPC into clear aligner resin appears to be a promising approach for developing new materials that resist both protein adsorption and bacterial attachment.

This study has several limitations. Certain mechanical properties such as water absorption and compressive strength were not evaluated, making it difficult to fully verify long-term stability in the humid oral environment. In addition, the study did not include a thermocycling process, therefore it could not sufficiently reflect the changes in physical properties or antibacterial performance due to temperature and humidity variations during actual usage. Furthermore, the in vitro experiments were conducted using a single bacterial strain, in which conditions such as complex oral microbiota or salivary flow rates were not fully considered. As a result, the evaluation of antibacterial durability or long-term maintenance effects according to MPC concentrations were limited. Although the MPC only mixing approach may effectively enhance antibacterial and anti-protein adhesion properties, it does not provide direct bactericidal effects or remineralization capabilities. Therefore, future studies should comprehensively validate clinical efficacy and stability through aging tests such as thermocycling, as well as in vivo and ex vivo models. Additionally, combining MPC with remineralizing agents or antibacterial substances should be explored to enhance its functional properties.

A significant methodological limitation of this study is the lack of quantitative degree of conversion analysis, which is critical for evaluating polymerization efficiency at various MPC concentrations. Although it was hypothesized that higher MPC concentrations may influence light transmittance and polymerization kinetics, direct quantitative evidence through spectroscopic measurements were not provided. Future studies should incorporate comprehensive FTIR or Raman spectroscopy analysis to quantify polymerization efficiency and correlate degree of conversion values with mechanical properties to determine optimal curing parameters. Specifically, FTIR-based quantification of C = C bond reduction at 1634 cm−1 relative to a stable internal standard may allow a more precise evaluation of double bond conversion. Additionally, Raman spectroscopy with its superior spectral resolution, could serve as an alternative to detect subtle changes in polymer chemistry. Establishing standardized curing protocols and investigating the relationship between degree of conversion, water absorption, and long-term material durability will be critical in optimizing clinical applicability.

A major analytical limitation of this study is the inability to quantitatively confirm MPC incorporation through FTIR spectroscopy. This limitation stems from several factors. The low MPC concentrations (1–3 wt%) approach the detection threshold of conventional FTIR techniques. The characteristic MPC signals such as the P=O stretch (1200–1300 cm−1) and P–O stretch (1000–1100 cm−1) are likely obscured by overlapping peaks from the polyester-urethane backbone of the TC-85 resin matrix. Additionally, quaternary ammonium group vibrations (N+(CH3)3) of MPC may be masked by intense C–H and N–H stretching vibrations present in the resin matrix. To overcome these limitations, future studies should apply more sensitive analytical tools. Contact angle measurements can provide indirect evidence of MPC incorporation by detecting changes in surface hydrophilicity. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) may be employed for elemental detection of phosphorus and nitrogen from MPC. Furthermore, 31P nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy could definitively confirm the presence of phosphorylcholine groups within the polymer structure. These complementary approaches would offer more conclusive evidence and enable quantitative assessment of MPC distribution.

Another critical limitation of this study is the absence of systematic biocompatibility evaluation using relevant human oral epithelial cell models. While MPC has demonstrated excellent biocompatibility in prior dental applications17,19,31, direct cytotoxicity assessment of our specific MPC modified TC-85 formulations would significantly strengthen the clinical applicability of our findings. While this study did not directly evaluate cytocompatibility, several previous literatures consistently support the biocompatibility of MPC-containing dental materials19,31, with studies demonstrating favorable cellular response toward oral cells, supporting the potential safety of our formulation17,19. In a precious literature, the effect of MPC on human oral keratinocyte RT-7 was investigated19. MPC treatment significantly reduced the adherence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and suppressed interleukin (IL)-8 production in a concentration dependent manner. Moreover, MPC protected oral epithelial cells from chemical injuries induced by agents such as cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC). These results suggest that MPC additives exhibit not only anti-inflammatory properties but also cytoprotective effects toward oral epithelial cells, supporting its suitability for oral biomedical applications19. MPC has been used in FDA approved biomedical devices—including artificial blood vessels, contact lenses, artificial hearts and lungs—due to its well-established biocompatibility17. Based on this extensive clinical use, MPC has been recognized as a cytocompatible and non-toxic polymeric material. To build upon this foundation, future studies should perform in vitro cytotoxicity assays in accordance with ISO 10,993–5 guidelines using human oral epithelial cells and gingival fibroblasts. Complementary tests such as live/dead cell staining, long-term proliferation assays, cytokine response profiling, and cell adhesion/morphology imaging will be essential to thoroughly evaluate biological safety. Moreover, in vivo and ex vivo models should be employed to validate long-term functional performance under clinically relevant conditions.

Conclusion

This study is few to date to examine the effect of applying MPC on protein attachment and on mechanical characteristics of clear aligner materials. In this study, incorporating zwitterionic material with clear aligner resin TC-85 exhibited protein-repellent activity while preserving its mechanical properties. Utilizing a protein repellent strategy holds great potential for creating dental resins that minimize bacterial adhesion, biofilm formation, plaque accumulation and the risk of cavities during orthodontic treatment. Therefore, clear aligner resin containing MPC could be applicable as a promising protein-repellent method during orthodontic treatment due to decrease in biofilm formation and oral bacterial attachment inhibition.

Materials and methods

Formulation of experimental solutions: incorporation of zwitterionic materials into clear aligner resin

To synthesize the experimental resins, Tera Harz TC-85 (Graphy Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) clear aligner resin and zwitterionic material, 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), were used in this study. All mixing procedures were conducted at 25 °C and 45 ± 5% relative humidity to ensure consistent viscosity and to prevent premature gelation.

MPC powder was gradually incorporated into the TC-85 resin at concentrations of 1%, 2%, and 3% by weight. To minimize local concentration gradients and reduce aggregation, MPC was added in small increments (0.1 wt%) while stirring with a magnetic stirrer at 300 rpm for 15 min.

Following magnetic stirring, the mixture was subjected to ultrasonic bath treatment (40 kHz, 100W, 25 °C) for 15 min to promote uniform dispersion and break up any micro-aggregates. After sonication, the mixture was manually spatulated using a glass rod for 5 min to ensure complete mixing, followed by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 2 min to remove entrapped air bubbles.

No phase separation or aggregation was observed upon visual inspection prior to curing. The mixture remained homogeneous, and no in-homogeneity was noted in the cured samples. All samples were prepared before light polymerization. All mixing steps were performed by a single operator to minimize procedural variation, and the mixed resins were used within 30 min of preparation to prevent potential phase separation or premature gelation.

Unmodified TC-85 clear aligner resin without any zwitterionic material was used as the control. The experimental samples were fabricated by light polymerization, removal of residual resin, and post-curing according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Consequently, the following four groups were tested:

-

(1)

Control Tera Harz TC-85 clear aligner resin (referred to as ‘control’)

-

(2)

99% clear aligner resin + 1% MPC (referred to as ‘MPC 1%’)

-

(3)

98% clear aligner resin + 2% MPC (referred to as ‘MPC 2%’)

-

(4)

97% clear aligner resin + 3% MPC (referred to as ‘MPC 3%’)

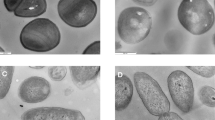

Specimen fabrication

As illustrated in Fig. 7, to evaluate the anti-bacterial properties and mechanical properties, samples in different sizes were fabricated. For the measurement of anti-bacterial test, round disc-shaped specimens in diameter of 8 mm and height of 0.5 mm were fabricated. Dumbbell shaped specimens (3.2 × 9.5 mm) were prepared for static mechanical test according to ASTM D638-5. Specimens for stress relaxation, creep, and flexural test were prepared in the form of a rectangular strip with a size of 10 × 50 mm4.

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation was performed using G-power 3.1 software (Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). Based on an effect size of f = 0.25 (equivalent to Cohen’s d = 0.5), a significance level (α) of 0.05, a statistical power (1 − β) of 0.90, and four experimental groups, a one-way ANOVA indicated that a total of 44 participants would be required. Based on this sample size calculation, a minimum of 11 specimens were allocated to each group. For mechanical testing, 45 specimens per group were allocated to ensure adequate statistical power and account for potential specimen loss during testing, providing > 95% statistical power to detect clinically meaningful differences.

Mechanical properties

Yield stress test

Fourty five specimens per group were subjected to a static tensile test at 25 °C and 55% humidity using a universal testing machine (Shimadzu Autograph AGS-X Series, 1kN load cell, Japan). The crosshead speed was set at 1 mm/min, and the specimen was elongated at a constant speed until completely fractured. The static mechanical properties of each material were evaluated by comparing strength and elastic modules.

Three-point flexural test

Fourty five specimens per group were subjected to a three-point flexural test at 25 °C and 55% humidity using a universal testing machine (Shimadzu Autograph AGS-X Series, 1 kN load cell, Japan) with a three-point bend fixture. The applied velocity of the bending load was 1 mm/min, and the distance between supports was L = 20 mm. Load–displacement plots were obtained for each test specimen. The strength (σ) was calculated from the following formula: \(\sigma = {\raise0.7ex\hbox{${3PL}$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{3PL} {2bd^{2} }}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${2bd^{2} }$}}\).

Where P is load during the test [N]; L is supporting span (mm); b is sample width (mm); d is sample thickness (mm).

Stress relaxation and creep test

According to the previous study by Lee et al.4, creep and stress relaxation of each material were evaluated by DMA (TA instrument DMA 850, USA) under the stress relaxation mode at 37 °C. Four specimens were tested for each group. Stress relaxation was estimated whether the results showed a deviation within 2%. Creep behavior was measured under 0.6 MPa stress.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis

The Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, Spectrum GX; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to analyze the chemical structure of the experimental resins. Spectra were examined in the range of 4000–650 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 using 32 scans. For FTIR spectroscopic analysis, thin film specimens with a thickness of 0.5 ± 0.05 mm were prepared using the same polymerization protocol as the mechanical testing specimens to ensure representative chemical characterization of the fully cured materials. The thickness of each specimen was verified using digital calipers with a precision of ± 0.01 mm to maintain analytical consistency. To determine the proportion of double bonds reacted through polymerization in each group, the absorbance peak areas of methacrylate carbon double bond (aliphatic carbon double bond; peak at 1634 cm−1) and internal standard (Aromatic carbon double bond; peak at 1608 cm−1) were measured.

Biological properties

Conoly-forming unit assay

The protocol for colony-forming unit assay and MTT assay was referred from a previous study by Yan et al.5 The antibacterial evaluation was conducted in accordance with ISO standardization (ISO 22,196:2007, Plastics–measurement of antibacterial activity on plastics surface)32. The specimens were cut into 5.0 cm * 5.0 cm squares and sterilized using ultraviolet irradiation for 30 min. Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans, UA159) were cultured in brain heart infusion (BHI, Sigma, US) broth for 24 h at 37 °C micro-aerobic conditions and adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 106 CFU/ml with BHI broth. Each sample was placed in sterile culture dish, and 0.4 ml of the 1 × 106 CFU/mL S. mutans solution was dripped on the sample surface. A 4.0 cm * 4.0 cm polypropylene (PP) plastic film was placed over the droplet to spread the S. mutans solution to the edge of the PP film. The culture dish was incubated at 37 °C micro-aerobic condition for 24 h. After incubation, 10 ml of soya casein digest lecithin polysorbate broth (SCDLP broth, Hopebiol, China) was added to the dish to wash off the bacteria. The SCDLP broth was then diluted by PBS, and BHI solid agar medium (BHI with 1.5 wt% agar) was used to count the S. mutans colonies. Each group included three replicates.

MTT assay

To further assess the anti-biofilm capability of each sample, the S. mutans biofilm was co-cultured with the sample. S. mutans were cultured in a BHI medium containing 1% sucrose. Sterilized specimens were cut into 1.1 cm * 1.1 cm squares and placed into wells of a 24-well plate. Each sample surface was then inoculated with 100 μl of the S. mutans solution. The 24-well plate was incubated at 37 °C micro-aerobic conditions for 24 h. After incubation, 1 mL of 0.5 mg/ml MTT solution (Beyotime, China) was dripped to each well to incubate with the biofilm at 37 °C under micro-aerobic conditions for 1 h. The MTT solution was then replaced with 500 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma, US). The 24-well plate was shaken on a table concentrator for 30 min, after which 100 μl of the DMSO solution from each well was transferred to a 96-well plate. The absorbance at 540 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek Synergy HTX, Agilent). Each sample absorbance was averaged from three repetitions. Five replicates were prepared for each group.

Protein adsorption test

The specimens were first immersed in fresh phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. They were then submerged in a protein solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA, Difco, Sparks, MD, USA) and bovine heart infusion (BHI, Difco, Sparks, MD, USA) broth (100 µL; 2 mg/mL) in PBS. After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, the specimens were gently rinsed twice with fresh PBS. After 4 h of incubation under sterile humid conditions at 37 °C with 5% CO2, any non-adhered protein was removed by washing twice with PBS to evaluate initial protein adsorption on their surface. The amount of adsorbed protein was measured by using 400 µL micro-bicinchoninic acid (Pierce Biotechnology Inc., IL, USA), followed by incubation at 37 °C at 30 min. The quantitative analysis of the adsorbed proteins on specimen surfaces were performed using the Micro BCA™ Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, IL, USA). The optical density (OD) of each sample was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Epoch; BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 software program (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The values were submitted to a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare between experimental groups. Turkey’s HSD test was performed for multiple comparison. The level of significance was set as P < 0.05.

Data availability

All data associated with this study are presented in the paper.

References

Kesling, H. D. The philosophy of the tooth positioning appliance. Am. J. Orthod. Oral Surg. 31, 297–304 (1945).

Melkos, A. B. Advances in digital technology and orthodontics: A reference to the Invisalign method. Med. Sci. Monit. 11, 39–42 (2005).

Can, E. et al. In-house 3D-printed aligners: Effect of in vivo ageing on mechanical properties. Eur. J. Orthod. 44, 51–55 (2022).

Lee, S. Y. et al. Thermo-mechanical properties of 3D printed photocurable shape memory resin for clear aligners. Sci. Rep. 12, 6246 (2022).

Yan, J. et al. In vitro evaluation of a novel fluoride-coated clear aligner with antibacterial and enamel remineralization abilities. Clin. Oral Investig. 27, 6027–6042 (2023).

Grant, J. Forces and moments generated by 3D direct printed clear aligners of varying labial and lingual thicknesses during lingual movement of maxillary central incisor: An in vitro study. Prog. Orthod. 24(1), 23 (2023).

Ogaard, B., Rølla, G. & Arends, J. Orthodontic appliances and enamel demineralization. Part 1. Lesion development. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 94, 68–73 (1988).

Jasso-Ruiz, I. et al. Silver nanoparticles in orthodontics, a new alternative in bacterial inhibition: In vitro study. Prog. Orthod. 21, 24 (2020).

Lee, E. S., de Josselin de Jong, E. & Kim, B. I. Detection of dental plaque and its potential pathogenicity using quantitative light-induced fluorescence. J. Biophotonics. 12, e201800414 (2019).

Zeidan, N. K., Enany, N. M., Mohamed, G. G. & Marzouk, E. S. The antibacterial effect of silver, zinc-oxide and combination of silver/ zinc oxide nanoparticles coating of orthodontic brackets (an in vitro study). BMC Oral Health 22, 230 (2022).

Cheng, L. et al. Anti-biofilm dentin primer with quaternary ammonium and silver nanoparticles. J. Dent. Res. 91, 598–604 (2012).

Zhang, K. et al. Effect of quaternary ammonium and silver nanoparticle-containing adhesives on dentin bond strength and dental plaque microcosm biofilms. Dent. Mater. 28, 842–852 (2012).

Wang, Y. et al. Strong antibacterial dental resin composites containing cellulose nanocrystal/zinc oxide nanohybrids. J. Dent. 80, 23–29 (2019).

Wang, Y., Zhu, M. & Zhu, X. X. Functional fillers for dental resin composites. Acta Biomater. 122, 50–65 (2021).

Vu, T. V. et al. Water-borne ZnO/acrylic nanocoating: Fabrication, characterization, and properties. Polymers (Basel) 13, 717 (2021).

Lussi, A. & Carvalho, T. S. The future of fluorides and other protective agents in erosion prevention. Caries Res. 49(Suppl 1), 18–29 (2015).

Zhang, N. et al. A novel protein-repellent dental composite containing 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine. Int. J. Oral Sci. 7, 103–109 (2015).

Kwon, J. S. et al. Durable oral biofilm resistance of 3D-printed dental base polymers containing zwitterionic materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 417 (2021).

Yumoto, H. et al. Anti-inflammatory and protective effects of 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine polymer on oral epithelial cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 103, 555–563 (2015).

Fujiwara, N. et al. 2-Methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC)-polymer suppresses an increase of oral bacteria: A single-blind, crossover clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 23, 739–746 (2019).

Park, S. Y., Yoo, K. H., Yoon, S. Y., Son, W. S. & Kim, Y. I. Synergetic effect of 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine and mesoporous bioactive glass nanoparticles on antibacterial and anti-demineralisation properties in orthodontic bonding agents. Nanomaterials (Basel) 10, 1282 (2020).

Jiang, S. & Cao, Z. Ultralow-fouling, functionalizable, and hydrolyzable zwitterionic materials and their derivatives for biological applications. Adv. Mater. 22, 920–932 (2010).

Chou, Y. N. et al. Epoxylated zwitterionic triblock copolymers grafted onto metallic surfaces for general biofouling mitigation. Langmuir 33, 9822–9835 (2017).

Ishihara, K., Fukumoto, K., Iwasaki, Y. & Nakabayashi, N. Modification of polysulfone with phospholipid polymer for improvement of the blood compatibility. Part 1. Surface characterization. Biomaterials 20, 1545–1551 (1999).

Ishihara, K., Fukumoto, K., Iwasaki, Y. & Nakabayashi, N. Modification of polysulfone with phospholipid polymer for improvement of the blood compatibility. Part 2. Protein adsorption and platelet adhesion. Biomaterials 20, 1553–1559 (1999).

Zhang, N. et al. Development of a multifunctional adhesive system for prevention of root caries and secondary caries. Dent. Mater. 31, 1119–1131 (2015).

Zhang, N. et al. Orthodontic cement with protein-repellent and antibacterial properties and the release of calcium and phosphate ions. J. Dent. 50, 51–59 (2016).

Kwon, J. S. et al. Novel anti-biofouling bioactive calcium silicate-based cement containing 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine. PLoS ONE 14, e0211007 (2019).

Zhang, N. et al. Protein-repellent and antibacterial dental composite to inhibit biofilms and caries. J. Dent. 43, 225–234 (2015).

Xie, X. et al. Novel dental adhesive with triple benefits of calcium phosphate recharge, protein-repellent and antibacterial functions. Dent. Mater. 33, 553–563 (2017).

Kwon, J. S. et al. Novel anti-biofouling light-curable fluoride varnish containing 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine to prevent enamel demineralization. Sci. Rep. 9, 1432 (2019).

Polymers-Part D-B. 2: Orthodontic base polymers. BS EN ISO. 2013:20795-2.

Takahashi, N. et al. Evaluation of the durability and antiadhesive action of 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine grafting on an acrylic resin denture base material. J. Prosthet. Dent. 112, 194–203 (2014).

Kyomoto, M. et al. Effects of mobility/immobility of surface modification by 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine polymer on the durability of polyethylene for artificial joints. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 90, 362–371 (2009).

Lee, M. J. et al. Bioactive resin-based composite with surface pre-reacted glass-ionomer filler and zwitterionic material to prevent the formation of multi-species biofilm. Dent. Mater. 35, 1331–1341 (2019).

Lee, M. J. et al. Improvement in the microbial resistance of resin-based dental sealant by sulfobetaine methacrylate incorporation. Polymers (Basel) 12, 1716 (2020).

Atta, I. et al. Physiochemical and mechanical characterisation of orthodontic 3D printed aligner material made of shape memory polymers (4D aligner material). J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 150, 106337 (2024).

Choi, J.-Y. et al. Mechanical and viscoelastic properties of a temperature-responsive photocurable resin for 3D printed orthodontic clear aligners. Sci. Rep. 15, 23530. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4106282/v1 (2024).

Bichu, Y. M. et al. Advances in orthodontic clear aligner materials. Bioact. Mater. 22, 384–403 (2023).

Sayahpour, B. et al. Effects of intraoral aging on mechanical properties of directly printed aligners vs. thermoformed aligners: an in vivo prospective investigation. Eur. J. Orthod. 46, cjad063 (2024).

Exterkate, R. A., Crielaard, W. & Ten Cate, J. M. Different response to amine fluoride by Streptococcus mutans and polymicrobial biofilms in a novel high-throughput active attachment model. Caries Res. 44, 372–379 (2010).

Shinohara, M. S. et al. Fluoride-containing adhesive: Durability on dentin bonding. Dent. Mater. 25, 1383–1391 (2009).

Scott, K., Igor, P., Anthony, N. & Rodrigo, F. Effect of different post-curing methods on the degree of conversion of 3D-printed resin for models in dentistry. Polymers 16, 549 (2024).

Nathalia, S. et al. Effects of solvent type and UV post-cure time on 3D-printed restorative polymers. Dent. Mater. 40, 451–457 (2024).

Lewis, A. L., Tolhurst, L. A. & Stratford, P. W. Analysis of a phosphorylcholine-based polymer coating on a coronary stent pre- and post-implantation. Biomaterials 23, 1697–1706 (2002).

Donlan, R. M. & Costerton, J. W. Biofilms: Survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15, 167–193 (2002).

Mashaghi, S., Jadidi, T., Koenderink, G. & Mashaghi, A. Lipid nanotechnology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 4242–4282 (2013).

Yamasaki, A. et al. Surface mobility of polymers having phosphorylcholine groups connected with various bridging units and their protein adsorption-resistance properties. Colloids Surf., B 28, 53–62 (2003).

Ishihara, K. et al. Why do phospholipid polymers reduce protein adsorption?. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 39, 323–330 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (RS-2025-00523024) and Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education(No. RS-2023-00245879).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.P and Y.-I.K.; methodology: Y.P, Y.K.,Y.K.C, and W.K.; formal analysis: Y.P, Y.K.,S.H.K., S.S.K., and W.K.; writing—original draft preparation: Y.P and Y.-I.K.; writing—review and editing: Y.P, Y.K., Y.K.C., S.H.K., S.S.K.,W.K. and Y.-I.K.; funding acquisition: W.K. and Y.-I.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paik, Y., Kim, YM., Choi, YK. et al. Enhanced anti-microbial properties of clear aligner resin containing zwitterionic material. Sci Rep 15, 28664 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14004-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14004-0