Abstract

Despite Macadamia’s global economic importance as a nutrient-dense nut crop, the structural and evolutionary characteristics of its chloroplast genomes (plastomes) remain underexplored. Here, we present the first comprehensive plastomic analysis of 185 cultivated Macadamia accessions from a Chinese germplasm collection. These plastomes exhibited conserved quadripartite structures (159,195–159,726 bp), comprising a large single-copy (LSC, 87,651–88,107 bp), a small single-copy (SSC, 18,743–18,819 bp), and inverted repeats (IRs, 26,378–26,422 bp). All plastomes maintained 115 functional genes (81 protein-coding, 30 tRNA, 4 rRNA) and were classified into 23 unique haplotypes. We identified 573 SNPs, 577 long repeats, and five hypervariable regions (trnS–trnG-exon1, ndhD–psaC, trnH–psbA, petA–psbL, and psbC–psbZ), with nucleotide diversity (Pi) values > 0.01. Phylogenetic reconstruction based on whole plastomes resolved maternal lineages and revealed distinct clustering patterns between ancestral and modern cultivars, with first-generation hybrids demonstrating significant plastomic uniformity. Notably, three accessions (‘Bailahe1’, ‘JingG6’, ‘Jing40’) showed ambiguous phylogenetic placement, warranting further investigation. Our findings provide critical plastomic resources for cultivar authentication, evolutionary studies, and the strategic expansion of genetic diversity in Macadamia breeding programs, particularly valuable given the crop’s recent domestication history and narrow genetic base.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Macadamia (genus Macadamia, family Proteaceae), an economically significant nut crop indigenous to eastern Australia, has achieved global cultivation distribution including major production regions in China, Australia, South Africa, and Kenya1. Renowned for its nutritional composition, macadamia kernels contain elevated levels of monounsaturated fatty acids and essential micronutrients, positioning them as a functional food with demonstrated health benefits2. Expanding applications in culinary oils, cosmetics, and confectionery products have driven substantial increases in global demand. Despite its economic prominence, macadamia remains a recently domesticated species with commercial cultivation history under a century. These domestication efforts are majorly based on two of the total four recognized macadamia species from this genus: M. integrifolia, M. tetraphylla3. Initial domestication efforts in Australia and subsequent commercial development in Hawaii established foundational cultivars that continue to underpin global production4. Notably, most commercial genotypes remain separated by only 2–4 generations from wild progenitors5indicating limited genetic divergence during domestication.

China’s macadamia industry has experienced exponential growth over three decades, particularly in Yunnan Province. Early production relied heavily on Australian and Hawaiian cultivars, while parallel breeding initiatives using introduced germplasm have developed regionally adapted accessions for diverse cultivation regions and environmental conditions. Given the limited generation turnover and short cultivation history of macadamia in China, the introduced germplasm can be considered ‘raw materials’, while the locally selected germplasm represents the ‘first generation’. Cultivar and accession identification are critical for modern plant breeding programs and germplasm collection6. However, detailed parental information is largely unavailable for most ‘first generation’ samples, except for some hybrids generated through cross-breeding. The lack of improved varieties remains a major constraint for China’s macadamia industry, underscoring the importance of elucidating genetic relationships within germplasm collections to facilitate genetic improvement.

Studies of genetic relationships in plants have traditionally relied on both morphological characteristics and molecular markers. While morphological traits offer valuable phenotypic information, molecular markers provide more precise and reliable insights into genetic variation at the species level. For macadamia, extensive efforts have been made to evaluate genetic diversity and population structure using various nuclear genome-derived markers, including amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLPs)7simple sequence repeats (SSRs)8,9and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)10,11. However, studies characterizing the genetic and structural variation of chloroplast genomes in Macadamia and using it to assess the genetic diversity of domesticated macadamia varieties remain limited.

Chloroplasts, the energy-producing organelles in plant cells, possess their own genetic material. The chloroplast genome (plastome) of land plants typically forms a circular DNA molecule characterized by a conserved quadripartite structure: one large single-copy region (LSC), one small single-copy region (SSC), and two inverted repeat regions (IRs)12. Compared to nuclear genomes, plastomes exhibit several distinctive features, including smaller size (120–160 kb), predominantly maternal inheritance, and relatively lower nucleotide substitution rates13. However, chloroplast DNA demonstrates a higher mutation rate than mitochondrial DNA, another maternally inherited organellar genome14,15. Notably, noncoding regions of plastomes, particularly intergenic spacers, evolve more rapidly than coding regions16making plastome an invaluable tool for phylogenetic studies across various taxonomic levels. While plastomes structure and genes are conserved during crop domestication, the plastomes of cultivated species can still exhibit altered genetic diversity17haplotype diversity18and other features19compared to their wild relatives.

In Macadamia, plastomic data have been proven instrumental in confirming its phylogenetic position in the Proteaceae family20tracing the geographical origins of cultivated germplasm of Macadamia integrifolia4and revealing reticulate evolution in Macadamia combine with nuclear gene phylogenetic analysis21. Besides, the utility of plastome for phylogenetic analyses has been well-documented across numerous plant species, including olive22jujube23Isodon rubescens24and Japanese apricot25. Building upon these previous studies, we assembled complete plastomes of 185 macadamia individuals from a core germplasm in China, to reveal the maternal progenitor and genetic and structural variations of plastomes for these resources. Given macadamia’s few cultivation cycles and recent introduction to China, we hypothesize most of the ‘first generation’ individuals should share the same maternal donor and have uniform plastomic background. Our genetic and structural variation analyses aimed to identified unique plastomic haplotypes, and the distribution of SSRs, long repeats, and SNPs across these plastomes. These findings can provide essential resources for variety differentiation and enhance our understanding of genetic variation within existing macadamia breeding pools, offering valuable insights for future breeding and conservation efforts.

Results

Characteristics of Macadamia plastome

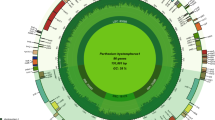

All 185 assembled plastomes of macadamia exhibit a typical quadripartite structure, with total length spanning 159,195 to 159,726 bp. Structural analysis revealed distinct regional variations: the large single-copy (LSC) region measured 87,651–88,107 bp, while the small single-copy (SSC) region ranged from 18,743 to 18,819 bp. Inverted repeat (IR) regions demonstrated a higher stability, maintaining lengths between 26,378 and 26,422 bp (Fig. 1). The total GC content across all genomes remained consistent at 38.11–38.14%, with regional differentiation: LSC regions displayed 36.54–36.61%, SSC regions 31.64–31.71%, and IR regions the highest values at 43.01–43.05% (Supplementary Table S1). The plastomes of the 185 macadamia individuals were highly conserved, each contained a complement of 115 unique genes, including 81 protein-coding genes, 30 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and four ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes (Supplementary Table S2). The rps12 gene in the 185 analyzed macadamia plastomes is distributed across the LSC and IR regions. Specifically, its 5’ exon resides in the LSC, while its 3’ exon is duplicated within the IRs. Sequence length analysis showed protein-coding regions occupied 80,793–80,829 bp, tRNA 2,729–2,877 bp, and rRNA 8,855–9,058 bp. The GC content was 38.43–38.46% in protein-coding gene, 53.17–53.33% in rRNA, and 55.25–55.27% in tRNA. All 185 complete plastomes can be classified into 23 different haplotypes (TYPE1–TYPE23), within which TYPE1 has the largest number of individuals (49), followed by TYPE9 (39). There are eight types that only consist of one individual (Supplementary Table S3).

Analyses of ssrs, long repeats, and codon usage

Comprehensive characterization of simple sequence repeats (SSRs) showed the number of SSRs ranges from 75 to 89 across 23 macadamia haplotypes (Fig. 2). Among these SSRs, mononucleotide repeats dominated the SSRs profile, ranged from 50 to 59 and accounting for 66.29–70.73% of all SSRs. Dinucleotide repeats ranged from 9 to 12, accounting for 12–13.48%, while trinucleotide repeats ranged from 4 to 6, representing 4.94–6.9% of all SSRs. Tetranucleotide repeats ranged from 9 to 10, making up 10.98–14.67% of the total SSRs. No pentanucleotide repeats were detected in any plastome, and hexanucleotide repeats were found in four plastomic haplotypes (TYPES 5, 6, 7, and 20). Regional distribution analysis showed LSC regions harbored 59–72 SSRs (74.68–80.9%), significantly exceeding SSC (11–14; 13.58–17.72%) and IR regions (4–6; 4.6–7.41%). In addition, Protein-coding regions contained 21–22 SSRs (23.6–28%) (Supplementary Table S4).

A total of 577 long repeats were identified across all plastomes, including 329 palindromic repeats, 192 forward repeats, 38 reverse repeats, and 18 complement repeats (Fig. 3). Both palindromic and forward repeats occurred universally and were detected in all plastomes, whereas complement repeats and reverse repeats showed restricted distribution and were found in 8 and 12 plastome haplotypes, respectively. Meanwhile, the long repeats can be classified into 20 length types (Supplementary Table S5). Among these, long repeats spanning 30–39 bp were predominant, accounting for 446 (73.4%), followed by those in the 40–49 bp range with 106 (17.4%). Notably, repeats exceeding 60 bp demonstrated a higher frequency of 23 (3.8%) than the 50–59 bp category, which showed the lowest frequency (0.3%).

The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values of 81 protein-coding genes spanning 0.35–1.85, with the number of codons ranged from 26,841 to 26,853 (Supplementary Table S6). Among all amino acid, leucine was the most frequently used codon (10.31–10.32%), while cysteine was the least frequent (1.19–1.2%). A total of 29 codons with RSCU values > 1.00 exhibited codon usage bias in the protein-coding genes of each plastome. With the exception of methionine and tryptophan, all other amino acids exhibited multiple synonymous variants.

SNPs and highly divergent regions among Macadamia

The nucleotide variability values as revealed by sliding window analysis across the whole plastome ranged from 0 to 0.03922 (Fig. 4). Five peaks with values > 0.01 were identified as regions of high nucleotide variability, four of which distributed in the LSC region, while one was found in the SSC region. The most variable region was located in the LSC region, specifically the trnS–trnG-exon1 (0.03922), followed by ndhD–psaC (0.01757), trnH–psbA (0.01653), petA–psbL (0.01565), and psbC–psbZ (0.01009). In addition, we identified 573 non-redundant SNPs across all plastomes, among which 380 SNPs (66.32%) were located in the intergenic spacer regions. SNPs from coding regions included 118 nonsynonymous mutations and 75 synonymous mutations. Among the coding genes, ycf1 had the highest number of SNPs (35), followed by ndhF (15), rpoC2 (13), and matK (11). Among all SNPs, 289 were transitional mutations, and 284 were transversional mutations. The most common substitution was G to A (101), followed by C to T (96), while G to C (19) was the least frequent.

Phylogenetic analyses

The 185 macadamia accessions were divided into four clades in the phylogeny (Fig. 5), three of which obtained full supports (Bootstrap values = 100) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Clade1 consists of eight haplotypes and 70 individuals, comprising of 14 ‘raw material’ and 56 ‘first generation’ individuals. Clade2 has the fewest haplotypes and includes only two ‘raw material’ individuals. Clade3 is composed of four haplotypes, with a total of 29 individuals, including 17‘raw material’ and 12 ‘first generation’ individuals. Clade4 contains the largest number of plastome types, with nine haplotypes represented among 84 individuals, including 49 ‘raw material’ and 35 ‘first generation’ individuals. Among the 28 hybrids created by cross-breeding within the ‘first generation’ individuals, 26 individuals had plastomes identical to their female parent. For example, ‘ym20’, ‘ym04’, ‘ym05’, and ‘ym07’ are hybrids from the maternal cultivar ‘D’, and all five individuals shared the same plastome (TYPE10). Similarly, both the female parent (‘D4’) and the hybrids (‘y-4-1604’, ‘ym29’, and ‘ym24’) shared the TYPE12 of plastome. The rest two hybrids, ‘ym10’ and ‘ym11’, share the same female parent, cultivar ‘NSW-44’; however, since the plastome of ‘NSW-44’ could not be successfully assembled, these two hybrids uniquely shared the TYPE21 plastome. In addition, most raw materials introduced from Hawaiian shared the TYPE1 plastome and clustered in Clade4. TYPE6 (M. tetraphylla) and TYPE13 (M. ternifolia), represented as early diverged clades from Clade3 and Clade1, respectively. Furthermore, three individuals: ‘Bailahe1’, ‘JingG6’, and ‘Jing40’, were collected from seedling orchards and considered as ‘first generation’. However, ‘Bailahe1’ and ‘JingG6’ shared the TYPE22 plastome, while ‘Jing40’ was the only individual with the TYPE23 plastome, raising questions about their maternal origin.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of 185 macadamia accessions categorized into ‘raw material’ (RM) and ‘first generation’ (FG) groups, with type classified into 23 plastome haplotypes (TYPE1–TYPE23). Representative accessions with known identity include NC_025288.1 (M. integrifolia), ‘AM-T-95’ (M. tetraphylla), and ‘AM-TF’ (M. ternifolia).

Discussion

In this study, we assembled and analyzed 185 complete plastomes from macadamia specimens, representing a significant advancement in our understanding of Macadamia chloroplast genomics. The sequenced plastomes exhibited length polymorphism ranging from 159,195 to 159,726 bp, with size variations primarily attributed to differences in the large single-copy (LSC) region rather than the small single-copy (SSC) or inverted repeat (IR) regions. This pattern of LSC variability aligns with observations in other plant taxa, such as Japanese apricot25highlighting the dynamic nature of this genomic region. Despite variations in plastome size, we observed remarkable conservation in gene order and content across all macadamia plastomes. The rps12 gene, a notable chloroplast gene, encodes the small ribosomal subunit S12 protein via trans-splicing26. Notably, no variations were detected in the exon location or intron content of rps12 within our study samples. This conserved structure contrasts with the variability observed in ferns27. The GC content, a crucial genomic feature associated with genome size and ecological adaptation in plants28showed minimal variation among samples, reflecting its conservation at lower taxonomic levels. The IR regions exhibited the highest GC content (43%), followed by SSC (36.5%) and LSC (31.7%) regions, a pattern consistent with other plant plastomes29,30 that may be attributed to the clustering of rRNA genes in IR regions31. Our analysis of codon usage bias, influenced by both natural selection and mutation32identified 29 high-frequency codons in Macadamia plastomes, predominantly ending with A/T. This pattern mirrors observations in other dicotyledonous plants, including Ipomoea33 and Asteraceae species34. These finding underscoring the unique evolutionary characteristics of Macadamia plastomes.

Plastome simple sequence repeats (SSRs) have become invaluable tools in genetic studies due to their high polymorphism and reproducibility, making them particularly useful for assessing genetic diversity, reconstructing phylogenies, and facilitating species identification35. Our analysis revealed 75–89 SSR motifs per plastome, predominantly located in the large single-copy (LSC) region, a distribution pattern consistent with findings in Polystachya36. Similar to previous reports37we observed a preferential accumulation of SSRs in intergenic regions rather than coding sequences. Among the five SSR types identified in macadamia plastomes (excluding pentanucleotide repeats), mononucleotide repeats emerged as the most abundant, primarily consisting of homopolymeric A/T tracts. This observation aligns with SSR distribution patterns observed in both dicotyledonous38 and monocotyledonous plants36. The identified SSRs represent valuable molecular markers for future investigations into genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships within macadamia germplasm populations. Additionally, our repeat pattern analysis detected frequent palindromic and forward repeats but revealed an absence of reverse or complementary repeats across all examined plastomes. These findings provide important insights into the structural organization and evolutionary dynamics of Macadamia plastome.

Divergent plastomic hotspots hold considerable potential for phylogenetic reconstruction39 and cultivar discrimination40. Our investigation identified five hypervariable regions (Pi > 0.01) in Macadamia plastomes: trnS–trnG-exon1, ndhD–psaC, trnH–psbA, petA–psbL, and psbC–psbZ. Notably, the trnH–psbA intergenic spacer—an established universal chloroplast marker—has been widely employed across taxonomic levels41. Both trnS–trnG-exon1 and petA–psbL, situated within the large single-copy (LSC) region, have demonstrated significant variability in other plant plastomes24. These three conserved markers, combined with the newly identified ndhD–psaC and psbC–psbZ regions, represent promising candidates for phylogenetic analyses in Macadamia.

Chloroplast DNA’s moderate mutation rate and uniparental inheritance render it particularly suitable for phylogenetic and parentage studies42. However, conventional chloroplast markers often lack sufficient resolution for distinguishing closely related cultivars43. Recent advancements in plastome sequencing have successfully enabled varietal differentiation in rice44cacao45,46and olive22. Our phylogenomic analysis of 185 Macadamia plastomes revealed 23 distinct haplotypes. Three representative species accessions (‘HAES741’ which represents M. integrifolia, ‘AM-T-95’ represents M. tetraphylla, and ‘AM-TF’ that represents M. ternifolia) formed well-supported clades, confirming plastome efficacy for interspecific relationship analysis. Nevertheless, we also found identical plastome sequences among multiple individuals within taxonomic groups (Fig. 5), which aligns with a recent study based on platomic SNPs21. This highlights the significant limitations of plastomic data in varietal differentiation, particularly for modern cultivars. For instance, similar results were observed in tomato breeding programs where plastome sequencing failed to distinguish contemporaneous varieties47. Furthermore, the sharing of identical haplotypes among multiple individuals suggests that parental lines carrying these haplotypes possess a selective advantage in breeding programs, explaining their widespread use in Macadamia breeding.

Nonetheless, our results corroborate previous reports that plastome sequences exhibit higher discriminatory power for ancestral varieties compared to modern cultivars43. Notably, raw germplasm materials representing ancestral stock displayed unique haplotypes (TYPE13–TYPE19) that were readily distinguishable in phylogenetic reconstructions (Supplementary Table S3, Fig. 5). These unique haplotypes reflect evolutionary uniqueness and likely represent genotypes that have not undergone artificial selection. Conversely, first-generation cultivars predominantly shared identical plastomes (e.g., haplotypes in Clade 4), indicating genetic homogeneity in modern breeding lines. It is also notable that three accessions (‘Bailahe1’, ‘JingG6’, and ‘Jing40’) exhibited ambiguous phylogenetic placement, warranting further investigation. The nucleotide polymorphism levels in the FG and MR populations are similar, which may be attributed to either incomplete coverage of parental materials or an extremely short domestication period (Supplementary Table S8). This comprehensive assessment provides novel insights into maternal lineages and evolutionary origins of Macadamia cultivars through combined analysis of plastome variability and conservation. Future studies by incorporating more plastomic data from the wild macadamia accessions are needed to better trace the maternal origin of each cultivar lineage.

Conclusion

Our study presents the assembly and characterization of 185 macadamia plastomes, revealing conserved genomic architecture in GC content, gene composition, and codon usage patterns. We identified polymorphic SSRs, SNPs, and five hypervariable regions with potential as molecular markers for phylogenetic and population genetic studies. Phylogenetic reconstruction using complete plastome sequences successfully delineated relationships among ancestral germplasm and characterized first-generation cultivars. These findings demonstrate substantial genetic diversity within the macadamia germplasm resources in Yunnan, China, and provides critical baseline data for understanding genotypic relationships and informing future breeding strategies.

Materials and methods

Materials

In this study, a total of 185 samples covering three macadamia species were involved, including M. integrifolia, M. tetraphylla, and M. ternifolia. Among those, 82 samples were introduced from Australia and USA defined as ‘raw material’, while the remaining 103 samples created and selected in China were defined as ‘first generation’. All the samples are maintained at the Germplasm Repository of Macadamia Nut Jinghong City, Ministry of Agriculture, Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Province, China. Detailed samples information is provided in Supplementary Table S7.

Chloroplast genome assembly, annotation, and analyses

Whole-genome sequencing data for 208 macadamia samples from our previous study (Li et al.48; NCBI SRA accession PRJNA909356) were reanalyzed. Briefly, young leaves were collected and total genomic DNA was extracted using the TaKaRa MiniBEST Plant Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Takara Bio, China). Subsequently, standard DNA libraries were constructed following procedures that included DNA fragmentation. Finally, paired-end reads of 150 bp were generated on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform (Biomarker Technologies, China). Raw data were removed if they: (1) contained sequencing adapters; (2) had > 50% of bases with quality scores < 20 (Phred-like socre); or (3) were paired-end reads containing of > 10% ´N´ bases. Following quality filtering, plastomes were assembled with GetOrganelle49 using default parameters, yielding complete circular genomes for 185 samples, which were used in the subsequent annotation and analyses. Assembly orientations were standardized against the reference genome (NC_025288.1), and potential chloroplast partition structures were identified. GetOrganelle’s assembly steps and the reference genome employed effectively control for interference from contaminating bacterial reads. To identify unique plastomic haplotypes, redundant sequences were removed through BLAST-based pairwise genome comparisons. Annotation was performed using GeSeq50 with default parameters to predict protein-coding genes, tRNAs, and rRNAs. Gene positions were verified through BLAST alignment to reference chloroplast genes, with manual curation of start/stop codons and exon-intron boundaries. Genome visualization was generated using Organellar GenomeDRAW51. Functional annotation involved BLAST searches (E-value ≤ 10e− 5) against NCBI-Nr, Swiss-Prot, COG, KEGG, and GO databases.

Analyses of ssrs, repeat sequences and codon usage

Simple sequence repeats(SSRs)in all assembled plastomes were identified using the MISA software52with parameters set to 8, 5, 4, 3, 3, and 3 for mononucleotides, dinucleotides, trinucleotides, tetranucleotides, pentanucleotides, and hexanucleotides, respectively. REPuter software53 was used to detect four types of long repeat, including forward (F), reverse (R), complement (C), and palindromic (P), with parameters set as minimal repeat size 30 bp, Hamming distance 3, and maximum computed repeats 5000. In addition, the Cusp software54 was employed to analyze relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) to obtain codon usage patterns of Macadamia plastome.

Variant calling and annotation

MUMmer55 software was used to globally aligned sequence of each sample with the reference sequence (TYPE1) to identify variant sites between them, and perform an initial filtering to detect potential SNP sites. We extracted 100 bp sequences flanking the SNP site in the reference sequence, then used BLATv3556 software to align the extracted sequences with the assembly results to verify the SNP site. If the alignment length is less than 101 bp, it is deemed unreliable and will be discarded. If it aligns multiple times, it is considered an SNP in a repetitive region and will also be discarded. Finally, reliable SNPs are identified.

Analyses of nucleotide variability and phylogenetic analysis

DnaSP57 software was used to detect nucleotide variability of coding genes and Non-coding regions by a sliding window method, which window length was set to 300 bp, step size was set to 200 bp. We used the all 185 complete plastomes to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree. The plastomic sequences of two Proteaceae taxa, i.e., Helicia nilagirica (NC_057271.1) and Helicia shweliensis (NC_045942.1), were download as outgroup. Maximum Likelihood (ML) analyses were run using phyML software58 with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The phylogenetic tree was visualized by TVBOT59.

Data availability

The complete plastomes in the current study are openly available in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) under accession numbers: PV089718–PV089740.

References

O’Connor, K. et al. Population structure, genetic diversity and linkage disequilibrium in a macadamia breeding population using SNP and silicodart markers. Tree Genet. Genomes. 15, 24 (2019).

Hu, W., Fitzgerald, M., Topp, B., Alam, M. & O’Hare, T. J. A review of biological functions, health benefits, and possible de Novo biosynthetic pathway of palmitoleic acid in macadamia nuts. J. Funct. Foods. 62, 103520 (2019).

Hardner, C. Macadamia domestication in hawai‘i. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 63, 1411–1430 (2016).

Nock, C. J. et al. Wild origins of macadamia domestication identified through intraspecific Chloroplast genome sequencing. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 334 (2019).

Lin, J. et al. Signatures of selection in recently domesticated macadamia. Nat. Commun. 13, 242 (2022).

Korir, N. K. et al. Plant variety and cultivar identification: advances and prospects. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 33 (2), 111–125 (2013).

Steiger, D. L., Moore, P. H., Zee, F., Liu, Z. & Ming, R. Genetic relationships of macadamia cultivars and species revealed by AFLP markers. Euphytica 132, 269–277 (2003).

Nock, C. J. et al. Whole genome shotgun sequences for microsatellite discovery and application in cultivated and wild Macadamia (Proteaceae). Appl. Plant. Sci. 2, 1300089 (2014).

Ranketse, M., Hefer, C. A., Pierneef, R., Fourie, G. & Myburg, A. A. Genetic diversity and population structure analysis reveals the unique genetic composition of South African selected macadamia accessions. Tree Genet. Genomes. 18, 15 (2022).

Alam, M., Neal, J., O’Connor, K., Kilian, A. & Topp, B. Ultra-high-throughput DArTseq-based silicodart and SNP markers for genomic studies in macadamia. Plos ONE, 13(8), e0203465, (2018).

Mai, T., Alam, M., Hardner, C., Henry, R. & Topp, B. Genetic structure of wild germplasm of macadamia: species assignment, diversity and phylogeographic relationships. Plants 9, 714 (2020).

Khakhlova, O. & Bock, R. Elimination of deleterious mutations in plastid genomes by gene conversion. Plant. J. 46, 85–94 (2006).

Zhang, Y., Tian, L. & Lu, C. Chloroplast gene expression: recent advances and perspectives. Plant. Commun. 4, 100611 (2023).

Drouin, G., Daoud, H. & Xia, J. Relative rates of synonymous substitutions in the mitochondrial, Chloroplast and nuclear genomes of seed plants. Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 49,, 827–831 (2008).

Wolfe, K. H., Li, W. H. & Sharp, P. M. Rates of nucleotide substitution vary greatly among plant mitochondrial, chloroplast, and nuclear DNAs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 84, 9054–9058, (1987).

Downie, S. R., Katz-Downie, D. S. & Watson, M. F. A phylogeny of the flowering plant family apiaceae based on Chloroplast DNA rpl16 and rpoC1 intron sequences: towards a suprageneric classification of subfamily Apioideae. Am. J. Bot. 87, 273–292 (2000).

Muragrui, S. et al. Intraspecific variation within castor bean (Ricinus communis L.) based on Chloroplast genomes. Ind. Crop Prod. 155, 112779 (2020).

He, W. et al. The history and diversity of rice domestication as resolved from 1464 complete plastid genomes. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 781793 (2021).

Chen, Q. et al. The plastome reveals new insights into the evolutionary and domestication history of peonies in East Asia. BMC Plant. Biol. 23, 243 (2023).

Nock, C. J., Baten, A. & King, G. J. Complete Chloroplast genome of Macadamia integrifolia confirms the position of the Gondwanan early-diverging eudicot family proteaceae. BMC Genom 15, S13, (2014).

Manatunga, S. L. et al. Analysis of phylogenetic relationships in Macadamia shows evidence of extensive reticulate evolution. Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1394244 (2024).

Mariotti, R., Cultrera, N. G. M., Díez, C. M., Baldoni, L. & Rubini, A. Identification of new polymorphic regions and differentiation of cultivated olives (Olea Europaea L.) through plastome sequence comparison. BMC Plant. Biol. 10, 211 (2010).

Hu, G. et al. Haplotype analysis of Chloroplast genomes for jujube breeding. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 841767 (2022).

Lian, C. et al. Comparative analysis of Chloroplast genomes reveals phylogenetic relationships and intraspecific variation in the medicinal plant Isodon rubescens. PLoS ONE. 17, e0266546 (2022).

Huang, X. et al. The analysis of genetic structure and characteristics of the Chloroplast genome in different Japanese apricot germplasm populations. BMC Plant. Biol. 22, 354 (2022).

Hildebrand, M., Hallick, R. B., Passavant, C. W. & Bourque, D. P. Trans-splicing in chloroplasts: the rps12 loci of Nicotiana tabacum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 85, 372–376, (1988).

Liu, S. et al. Patterns and rates of plastid rps12 gene evolution inferred in a phylogenetic context using plastomic data of ferns. Sci. Rep. 10, 9394 (2020).

Šmarda, P. et al. Ecological and evolutionary significance of genomic GC content diversity in monocots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, E4096–E4102 (2014).

Xu, J., Shen, X., Liao, B., Xu, J. & Hou, D. Comparing and phylogenetic analysis Chloroplast genome of three achyranthes species. Sci. Rep. 10, 10818 (2020).

Yang, J. B., Yang, S. X., Li, H. T., Yang, J. & Li, D. Z. Comparative Chloroplast genomes of camellia species. PLoS ONE. 8, e73053 (2013).

Saldaña, C. A. et al. Unlocking the complete Chloroplast genome of a native tree species from the Amazon basin, Capirona (Calycophyllum Spruceanum, Rubiaceae), and its comparative analysis with other Ixoroideae species. Genes 13, 113 (2022).

Liu, Q. & Xue, Q. Comparative studies on codon usage pattern of chloroplasts and their host nuclear genes in four plant species. J. Genet. 84, 55–62 (2005).

Sudmoon, R. et al. The Chloroplast genome sequences of Ipomoea Alba and I. obscura (Convolvulaceae): genome comparison and phylogenetic analysis. Sci. Rep. 14, 14078 (2024).

Nie, X. et al. Comparative analysis of codon usage patterns in Chloroplast genomes of the Asteraceae family. Plant. Mol. Bio Rep. 32, 828–840 (2014).

Guo, Q. et al. Genetic diversity and population genetic structure of paeonia suffruticosa by Chloroplast DNA simple sequence repeats (cpSSRs). Hortic. Plant. J. 11, 367–376 (2025).

Jiang, H. et al. Comparative and phylogenetic analyses of six Kenya polystachya (Orchidaceae) species based on the complete Chloroplast genome sequences. BMC Plant. Biol. 22, 177 (2022).

Bodin, S. S., Kim, J. S. & Kim, J. H. Complete chloroplast genome of Chionographis japonica (Willd.) Maxim. (Melanthiaceae): comparative genomics and evaluation of universal primers for Liliales. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 31, 1407–1421, (2013).

Fan, Y. et al. The complete Chloroplast genome sequences of eight Fagopyrum species: insights into genome evolution and phylogenetic relationships. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 799904 (2021).

Jiang, D. et al. Complete Chloroplast genomes provide insights into evolution and phylogeny of Zingiber (Zingiberaceae). BMC Genom 24, 30, (2023).

Khan, A. L., Asaf, S., Lee, I. J., Al-Harrasi, A. & Al-Rawahi, A. First Chloroplast genomics study of Phoenix dactylifera (var. Naghal and Khanezi): A comparative analysis. PLoS ONE. 13, e0200104 (2018).

Loera-Sánchez, M., Studer, B. & Kölliker, R. DNA barcode trnH-psbA is a promising candidate for efficient identification of forage legumes and grasses. BMC Res. Notes. 13, 35 (2020).

Wu, F. H. et al. Complete Chloroplast genome of Oncidium gower Ramsey and evaluation of molecular markers for identification and breeding in oncidiinae. BMC Plant. Biol. 10, 68 (2010).

Teske, D., Peters, A., Möllers, A. & Fischer, M. Genomic profiling: the strengths and limitations of Chloroplast genome-based plant variety authentication. J. Agric. Food Chem. 9, 68, 14323–14333 (2020).

Tang, J. et al. A comparison of rice Chloroplast genomes. Plant. Physiol. 135, 412–420 (2004).

Herrmann, L., Haase, I., Blauhut, M., Barz, N. & Fischer, M. DNA-based differentiation of the Ecuadorian cocoa types CCN-51 and arriba based on sequence differences in the Chloroplast genome. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62, 12118–12127 (2014).

Kane, N. et al. Ultra-barcoding in Cacao (Theobroma spp.; Malvaceae) using whole Chloroplast genomes and nuclear ribosomal DNA. Am. J. Bot. 99, 320–329 (2012).

Kahlau, S., Aspinall, S., Gray, J. C. & Bock, R. Sequence of the tomato Chloroplast DNA and evolutionary comparison of solanaceous plastid genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 63, 194–207 (2006).

Li, Z. et al. Genetic diversity analysis of macadamia germplasm in China based on whole-genome resequencing. Tree Genet. Genomes. 20, 14 (2024).

Jin, J. J. et al. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de Novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 21, 241 (2020).

Tillich, M. et al. GeSeq - versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 45, W6-W11, (2017).

Greiner, S., Lehwark, P. & Bock, R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W59–W64 (2019).

Beier, S., Thiel, T., Münch, T., Scholz, U. & Mascher, M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 33, 2583–2585 (2017).

Kurtz, S. et al. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4633–4642 (2001).

Rice, P., Longden, I. & Bleasby, A. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trend Genet. 16, 276–277 (2000).

Kurtz, S. et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 5, R12 (2004).

Kent, W. J. BLAT-the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 12, 656–664 (2002).

Rozas, J. et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 3299–3302 (2017).

Guindon, S. et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321 (2010).

Xie, J. A. et al. Tree visualization by one table (tvBOT): a web application for visualizing, modifying and annotating phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W587–W592 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Tropical Crop Germplasm Resources Protection Project of the Ministry of Agriculture, China (18220024), Technology Talent & Platform Program of Yunnan (202405AD350061, 202205AD160080). The authors thanks Dr. Jian Liu from Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences for guiding data analyses and manuscript revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L., C.W. and L.T.; data analysis and manuscript drafting, Z.L. and C.W.; investigations and formal analysis, T.L., J.M. and Y.L.; writing – review & editing, Z.L., C.W. and L.T.; funding acquisition, L.G. and L.T. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Wu, C., Li, T. et al. Plastomic insights into the genetic variation and phylogenetic relationships of Macadamia. Sci Rep 15, 37579 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14011-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14011-1