Abstract

Monitoring species diversity and distribution patterns in remote ecosystems presents significant challenges due to vast geographic coverage, harsh environmental conditions, and the limited availability of traditional survey resources. Environmental DNA (eDNA) technology has been proven to be an effective method for biodiversity assessment, offering a non-invasive, cost-effective, and efficient solution. The study used eDNA metabarcoding technology to investigate fish communities in the Kashi River, a vital waterway in Xinjiang. Two-season of 37 eDNA water samples were taken from multiple sites, and 77 species were detected in April and 137 in September. Additionally, the results of spatial analysis showed that there were significant differences in fish composition among the different areas. These findings provided valuable insights into the ecological dynamics of the Kashi River of the Ili River, contributing to fish biodiversity conservation in freshwater ecosystem regions like the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Furthermore, the study underscored the potential of eDNA for long-term monitoring of freshwater ecosystems, informing conservation efforts, and managing fish resources in the Kashi River of the Ili River and similar freshwater ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an inland river in Central Asia, the Ili River originates in the Tian Shan Mountains of northwestern China and flows through Kazakhstan before eventually draining into Lake Balkhash1. The Ili River is the largest river in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and one of the three international rivers between China and the Republic of Kazakhstan. It has a total length of 1236 km and a drainage area of 151,000 square kilometers, 442 km and 56,000 square kilometers of which are located within China2. The Ili River basin topography is complicated. The River’s main stream and its three tributaries-Teksi River, Kunes River and Kashi River, flow through valleys. These tributaries have low but stable annual runoff, and the river has a steep gradient2. The unique terrain makes the Ili River Basin rich in water resources, fertile land, extensive grasslands, and dense forests, making it one of the most biodiverse regions in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region2,3. The ecosystem of the Ili River Basin contains abundant water resources and a healthy ecological environment, supporting diverse fish species3.

The Kashi River, a tributary of the Ili River, originates from the southern slopes of the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang and flows through a mountainous and ecologically diverse region. Although smaller than the main stem of the Ili River, the Kashi River plays an important ecological role in the local freshwater network, supporting aquatic biodiversity and serving as a vital water source for agriculture and livestock in surrounding communities3. In recent years, aquaculture and freshwater fisheries in southern Xinjiang have expanded steadily, and the fishery output and output value have increased year by year. Characteristic aquaculture has become a key driver of local economic development and has helped boost the income of farmers and herdsmen1. However, rivers in the region, including the Kashi River, face multiple environmental pressures, such as water extraction, habitat degradation, and climate variability, which threaten aquatic biodiversity and ecosystem stability2. Resource monitoring and sustainable management practices are essential to protect the health of rivers and the livelihoods they support4.

However, due to the Kashi River’s remote location and the complex topography of the Ili River basin, there is still a lack of relevant monitoring to grasp the overall status of its biological resources5. Fish represent a crucial ecological group within river ecosystems. Traditional methods for fish biodiversity monitoring—such as netting, electrofishing, or visual surveys—are often labor-intensive, spatially limited, and potentially harmful to aquatic habitats6. These limitations are particularly challenging in remote and rugged systems like the Kashi River, where seasonal access constraints hinder long-term ecological monitoring. In contrast, eDNA sampling can be conducted at regular intervals, offering a cost-effective means to monitor changes in species composition, abundance, and distribution throughout the year7. Despite the ecological importance of rivers in southern Xinjiang—such as the Kashi River—there have been few studies on fish biodiversity in these systems, likely due to their remoteness and limited accessibility2.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) has emerged as a powerful, non-invasive tool for assessing species diversity in freshwater ecosystems. By extracting trace DNA from water samples and applying eDNA metabarcoding, researchers can detect a wide range of fish species with high sensitivity and minimal habitat disturbance8,9,10. Metabarcoding of environmental DNA allows for the identification of species present in environmental samples, offering an effective tool for assessing fish biodiversity across different ecosystems. This approach can also aid in tracking species distribution, community structure, and ecological changes over time11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Previous studies have shown that eDNA has a high evaluation efficiency in freshwater fish community monitoring18,19,20,21,22,23. This method is particularly well-suited for challenging environments like the Kashi River Basin, where traditional surveys are limited by terrain and seasonal accessibility.

This study represents the first application of eDNA metabarcoding to assess fish diversity in the Kashi River. The main contents were as follows: (1) to survey the fish community structure in different sections of the river using eDNA, (2) to characterize spatial and seasonal patterns in species composition, and (3) to provide baseline data to support long-term monitoring and conservation strategies in this understudied region.

Methods

Sample collection

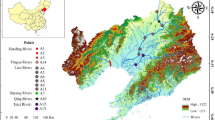

Environmental DNA (eDNA) samples were collected from Kashi River (81.81°E-84.14°E, 43.64°N-43.85’N), a tributary of the Ili River in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. A total of 21 sampling sites were established across the Kashi River basin to comprehensively assess fish community composition (Fig. 1). Sampling sites were selected to cover a range of ecological conditions, including upstream, midstream, and downstream locations, ensuring a comprehensive representation of fish diversity across the river. Sampling was conducted in two-season, April and September, to capture seasonal variations. A total of 37 samples (16 in April and 21 in September) were collected and analyzed in this seasonal snapshot monitoring. Subsequent analysis divided the survey stations into different groups based on the longitudinal gradient and flow direction of the Kashi River (Fig. 1).

eDNA sampling station along Kashi River in Xinjing Uygur Autonomous Region. In the top panel is a satellite image of the Kashi River basin, with the eDNA sampling sites represented by yellow points. At the bottom is a map of the Ili River showing the overall distribution area and range of sampling points in Xinjing Uygur Autonomous Region. The map was generated using ArcGIS 10.8 (Esri, 2020) available at https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis.

In April, samples were collected from the upstream to the downstream sections of the Kashi River, while in September, sampling began from the downstream section and moved upstream. Although the sample codes differ in directional order between the two seasons, each code corresponds to a consistent geographic location along the river. Due to ice cover and restricted field accessibility in early spring, only 16 samples were collected in April. To improve spatial coverage and enhance the dataset, five additional sampling points were added in September, which were highlighted in red in Fig. 1. The sampling process involved traveling along the river by vehicle, collecting water samples sequentially from upstream to downstream locations. To ensure the temporal consistency and reliability of the eDNA samples, the entire sampling cycle was completed within approximately one week. This timeline minimized potential degradation of eDNA and ensured the validity of the samples for subsequent analysis24.

For eDNA water collection, 2L freshwater samples were collected from surface water using bleach sterilized sample bucket and stored in brown jars sterilized to reduce DNA degradation caused by sun exposure23,25. During the sampling process, each new station sampling process will disinfect the sampling equipment to prevent cross-contamination. Then the water samples were immediately taken to a laboratory to be filtered for DNA collection, and filtration within two hours using a TM-Giltration device equipped with a Sterivex TM-GP filter unit (pore size, 0.22 μm; EMD Millipore Corp, Billerica, MA, USA)22. Additionally, a negative filtration control with ultrapure water was filtered. Filter membranes samples were immediately frozen and stored at −20 °C prior and post-transportation until DNA extraction26.

eDNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

The eDNA extractions from the filter units were performed using the TIANamp Soil DNA Kits (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol, and stored at −20 °C prior to further analysis. Then the quantity of extracted DNA was measured using a NanoDrop NC2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), while the quality was assessed through agarose gel electrophoresis22. To ensure no cross-contamination during the eDNA extraction process and introduced from the laboratory environment, negative controls of filtration controls and extraction blanks were extracted and processed alongside all samples. After confirming the quality of DNA extraction by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis, DNA was amplified using PCR assays to largely fishes23.

PCR amplification of the conserved region of 12S rRNA region was performed using the forward primer Teleo2 F (5'-AAACTCGTGCCAGCCACC-3′) and the reverse primer Teleo2 R (5'-GGGTATCTAATCCCAGTTTG-3′)11. Three PCR replicates were performed for each sample, and the reaction solution volume for PCR amplification totaled 25 µL and comprised the following components: The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification components consisted of 5 μL 5 × Reaction Buffer, 5 μL 5 × GC Buffer, 2 μL dNTP (2.5 mM), 1 μL Forward Primer (10 μM), 1 μL Reverse Primer (10 μM), 2 μL DNA Template, 8.75 μL ddH2O, and 0.25 μL Q5 DNA Polymerase. The thermal cycling profile was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 63 °C for 45 s, extension at 72 °C for 60 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR amplicons were purified with Vazyme VAHTSTM DNA Clean Beads (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) and quantified using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA)27. After the individual quantification step, amplicons were pooled in equal amounts, and pair-end 2 × 300 bp sequencing was performed using the Illlumina MiSeq platform with MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 at Shanghai Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China)22.

Sequencing library preparation was constructed by Illumina’s TruSeq Nano DNA LT Library Prep Kit. Libraries were sequenced on 500 cycles (for paired-end sequencing of the 12S amplicons) MiSeq V2 Standard Flow Cell on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA)23,28. The libraries were dissolved to 2 nM in a gradient before being proportionally blended to the required amount of data. Before on-machine sequencing, the library was inspected by Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit on Agilent Bioanalyzer28. The NovaSeq sequencer was used for double-ended sequencing with the NovaSeq 6000 SP Reagent Kit23. Then, the original high-throughput sequencing data was screened based on sequence quality, and problematic samples were further sequenced or re-sequenced as needed22,23,28.

Bioinformatics analysis and taxonomic assignment

The original MiSeq sequencing data were performed using the FastQC program and stored in FASTQ format23. The library and samples were divided according to index and barcode information from the original sequence of quality preliminary screening, and barcode sequence was removed. The sequences were further subjected to quality control using the Vsearch (v.2.13.4) pipeline29, the detail as follow: raw sequence data were demultiplexed using the demux plugin following by primers cutting with cutadapt plugin30. Sequences were then merged, quality filtered and dereplicated using functions of fastq_mergepairs, fastq_filter and derep_fullength in Vsearch plugen. All the unique sequences were then clustered at 98% (via cluster_size) followed by chimera removing (via uchime_denovo)23. Non-singleton amplicon sequence variants (OTUs) were aligned with mafft31.

Taxonomic information for each representative OTU sequence was assigned by querying against the NCBI GenBank nucleotide database using BLASTn, with comparisons made to both the NCBI Organelle Genome Resources (nt) database and the MitoFish database23,32. Taxonomic assignments were made based on the best BLAST hit with a sequence identity ≥ 97% and alignment coverage ≥ 80% for species-level identification. After that, the specific composition of each sample at different species taxonomic level was displayed to understand the overall situation. To enhance classification accuracy, all initially matched species were further screened using FishBase (https://www.fishbase.org/) and Fish Chronicles33, and potential misassigned or contaminant taxa were manually removed. Sequence data analyses were mainly performed using QIIME2 and R software (v4.2.3)34.

Statistical analyses

Through statistical analysis of the feature table after the removal of singleton, R script was used to calculate the clustering results of each sample and each taxon, and the species composition of the seasonal snapshot monitoring was presented in the form of bar graphs. Furthermore, the overlapping in fish OTUs between each station site in the two-season were illustrated by the “UpSetR” package to compare the uniqueness of the communities35. To identify key species contributing to seasonal differentiation, we employed a Random Forest classification algorithm using QIIME2. The input data consisted of a species-level abundance matrix generated from eDNA OTU assignments. The model was trained to classify samples by season (April vs. September), and species importance was assessed using permutation importance. The 20 species with the highest importance scores were selected for visualization. A corresponding heatmap was generated to show the relative abundance of these species across all sampling sites.

Alpha diversity indices, such as Chao1 richness estimator, Shannon diversity index, Simpson index, Faith’s PD, Pielou’s evenness and Good’s coverage were calculated using the OTU table in QIIME2, and visualized as box plots23. OTU-level ranked abundance curves were generated to compare the richness and evenness of OTUs among samples. To investigate the diversity of community composition across different sections of the Kashi River, sampling sites were divided into four groups corresponding to the upper, upper-middle, lower-middle, and lower reaches of the river, based on their longitudinal positions. Specifically, Group A is S1-S4 stations in the upper reaches of Kashi River; Group B is S5-S9 stations in the upper and middle reaches; Group C is S10-S13 stations in the middle and lower reaches; Group D is the downstream S14-S21 station (Fig. 1).

Beta diversity analysis was performed to assess differences in fish community composition across different regions and between the two seasons. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity was used to visualize patterns in community structure36. To further examine clustering patterns, hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted on the same dissimilarity matrix. NMDS, which preserves the rank order of dissimilarities rather than absolute distances, is well-suited for complex ecological data and provides a stable ordination37. All analyses were performed using the “vegan” package in R.

Results

Sequence statistics and fish composition

In this study, a total of 4,594,782 high-quality sequences (2,457,586 in April and 2,137,196 in September) were obtained after quality filtering and removal of chimeric reads, with an average of 124,183 sequences per sample. After bioinformatics filtering analysis, 166 fish species were detected in the eDNA survey conducted in the main stream of Kashi River and distributed across 111 genera, 44 families and 21 orders in two-season. Statistical analysis of eDNA data collected from 16 sampling stations in April identified 77 fish species. In September, eDNA analysis from 21 stations revealed a significantly greater taxonomic diversity, identifying 137 fish species. The results of seasonal snapshot monitoring showed noticeable differences in fish communities, with only 48 fish species consistently detected across both seasons. The survey situation of fish in each season was listed in Supplementary Table S1. We analyzed the monitoring results of two-season separately.

77 fish species belonging to 55 genera, 23 families, and 11 orders were detected in April, among the order levels, Cypriniformes, Gobiiformes, Siluriformes had the largest amount of eDNA monitoring; Among the family levels, Cyprinidae, Nemacheilidae, Xenocyprididae, Gobiidae, Acheilognathidae had the largest amount. Among the genera levels, Triplophysa, Rhinogobius, Acheilognathus had the largest amount (Table S1).

Figure 2 illustrated the species-level taxonomic composition and relative abundance of fish detected in different samples. Species are ordered by abundance, highlighting community structure variations among stations (Fig. 2). Variations in species composition among sites reflect spatial heterogeneity, and some samples show limited species annotation due to low eDNA concentrations or detection limitations. The fish species with high relative abundance detected in the April survey were Triplophysa aliensis, Triplophysa strauchii, Pseudorasbora parva, Micropercops swinhonis, Perca fluviatilis, Oncorhynchus mykiss, Gymnodiptychus dybowskii, Rhinogobius nagoyae, Carassius gibelio, Rasbora atridorsalis. (Fig. 2).

Species-level composition of fish communities based on the April eDNA survey. The horizontal axis represents the sample names. The vertical axis represents the relative abundance (%) at the species level. The right side illustrates the species-level taxonomic composition detected by eDNA monitoring in April, represented in the bar chart with different colors.

Then 137 species belonging to 101 genera, 43 families, and 21 orders were detected in September. Among the order levels, Cypriniformes, Gobiiformes, Perciformes had the largest amount of eDNA monitoring. Among the family levels, Leuciscidae, Xenocyprididae, Cyprinidae, Gobionidae, Nemacheilidae had the largest amount. Among the genera levels, Acheilognathus, Gobio, Phoxinus had the largest amount (Table S1). The fish species with high relative abundance detected in the September survey were Phoxinus ujmonensis, Carassius gibelio, Triplophysa aliensis, Gobio acutipinnatus, Triplophysa strauchii, Hypophthalmichthys nobilis, Gymnodiptychus dybowskii, Oncorhynchus mykiss, Siniperca scherzeri, Triplophysa labiate (Fig. 3).

Species-level composition of fish communities based on the April eDNA survey. The horizontal axis represents the September samples. The vertical axis represents the relative abundance (%) at the species level. The right side illustrates the species-level taxonomic composition detected by eDNA monitoring in September, represented in the bar chart with different colors.

Then, the freshwater fish statistics of the two-season were shown in Table 1. In general, the fish diversity of the Kashi River basin is very rich, with results showing a total of 153 freshwater fish species monitored over the two-season, and the fish composition of the two-season is significantly different. 73 freshwater fish were detected in April and 124 in September, among which 44 species of freshwater fish were detected in the two-season (Table 1).

“ + ” indicates species detected in the corresponding season; “✓” indicates species detected in both seasons; blank cells indicate absence. Species are listed in alphabetical order based on their scientific names.

Fish distribution in Kashi River

Figure 4 presents UpSet plots showing the overlap and distribution of fish species across sampling stations in April (a) and September (b), based on OTUs detected through eDNA analysis. As shown in the Fig. 4a, only 7.79% (6/77) of the fish species overlapped in all combinations of the April surveys as indicated by the red bars, with no significant difference fish numbers observed among sampling locations. Additionally, 14.29% (11/77) of fish species were detected at more than 50% of the stations. Station SE12 recorded the highest number of fish species, while station SE01 had the lowest. Notably, 22.08% (17/77) of the fish species identified in April were unique to that survey. The majority of unique OTUs were detected at stations SE10 and SE12, followed by SE16, SE14, SE09, SE08, and SE13 (Fig. 4a).

UpSet plots showing the overlap of fish species across stations in (a) April and (b) September. Red bars represent species shared across all stations; yellow bars indicate species unique to a single station; green bars show species detected at more than half of the stations (> 50%). The horizontal bars display the total number of species observed at each station.

In September, the OTU profiles sampling locations were highly variable, with only 1.46% (2/137) of fish species common to all sampling combinations (Fig. 4b). A larger proportion of species (6.57%, 9/137) were shared across more than 50% of stations, while 23.36% (32/137) were unique to only one station. Most unique OTUs in September were found at station UE21, followed by stations UE19, UE09, and UE02. Station UE02 recorded the highest fish species richness, while station UE06 detected the fewest species (Fig. 4b). These results highlighted differences in community composition and spatial distribution patterns.

The 20 most abundant fish species detected across the two-season were presented in Fig. 5. Species are ranked from top to bottom in descending order of significance, which from 6.00 to −0.63. A few species showed negative permutation importance values, indicating that their presence may introduce noise or have little relevance to the classification task (Fig. 5). These top-ranking species can be considered as key indicators of group differences between the two-season, highlighting their pivotal role in shaping the seasonal fish community composition of the Kashi River in the Ili River. The 20 most abundant species identified across the two surveys included Pseudorasbora parva, Micropercops swinhonis, Diptychus maculatus, Siniperca scherzeri, Triplophysa leptosoma, Elopichthys bambusa, Gymnodiptychus dybowskii, Rhinogobius nagoyaePerca fluviatilis, Triplophysa strauchii, Plecoglossus altivelis, Triplophysa aliensis, Triplophysa brevicauda, Triplophysa dorsalis, Carassius gibelio, Rasbora atridorsalis, Cyprinus acutidorsalis, Coreoperca whiteheadi, Perca schrenkii, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Fig. 5).

Fish diversity and seasonal variation

Ultimately, samples from two-season were grouped into four groups (A to B) for alpha diversity analysis, based on their longitudinal positions along the river from upstream to downstream (Fig. 1). Although the specific sample IDs within each group differed between seasons due to variations in sampling order, the groups were consistently presented in upstream-to-downstream order to ensure comparability. Figure 6 presented boxplots of alpha diversity indices (Observed species, Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson) across different sample groups. In each panel, the horizontal coordinate is the group label, and the vertical coordinate is the value of the corresponding alpha diversity index. The numbers under the diversity index label are the P-values of the Kruskal–Wallis test. Overall, no significant differences were observed among the groups in terms of species richness and diversity, indicating comparable levels of α diversity across regions.

In April, Group B exhibited notably higher Observed species and Chao1 indices compared to the other groups, suggesting a potentially higher species richness in this section. Some of the differences among groups were statistically significant (Kruskal–Wallis test, p < 0.05), indicating that spatial variation along the river may have a significant influence on fish diversity patterns (Fig. 6a). Additionally, the results showed that no significant difference in Shannon diversity was detected in September between the upstream and downstream regions (P > 0.05), suggesting that overall community evenness remained stable across stations (Fig. 6b).

The difference of fish composition among samples was demonstrated by NMDS dimensionality reduction method, and visualized by scatterplot, different colors and symbols are used to represent the groups to show the differences between samples more clearly (Fig. 7). The stress value of the NMDS analysis was below 0.2, confirming the reliability of the ordination results. The closer the distance between the samples, the smaller the difference between the fish communities in the two samples. In April, the fish composition of station SE02 and station SE14 were similar, station SE05, SE06 and SE07 were also similar. Fish composition at station SE16 was different from that at other stations (Fig. 7a).

NMDS Ordination Based on Bray–Curtis Dissimilarity of eDNA Composition (a) April survey sample. (b) September survey sample. (c) Comparison of samples in two-season. Each point in the figure represents a sample, with different colored points indicating different samples (groups). The proximity (or distance) between two points reflects the degree of similarity (or dissimilarity) in microbial community composition between the corresponding samples.

In September surveys, there was little difference in fish composition from station UE01 to station UE06, while they were different from other stations (Fig. 7b). Overall, the NMDS analysis of fish composition retrieved in different samples revealed marked spatial variation in community composition. In addition, we compared fish community composition between two-season, April and September, the results revealed clear clustering of samples by season, indicating significant differences in fish composition between the two periods (Fig. 7c).

Discussion

eDNA effectively detects fish diversity in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region

Previous studies have used eDNA to investigate fish diversity in other important freshwater river areas in China22,23,38,39. The above studies indicated that eDNA technology provided a valuable tool for conservation and management efforts in this ecologically significant yet understudied region. However, comprehensive investigations remain limited, leaving critical knowledge gaps regarding the biodiversity and conservation needs of the aquatic ecosystem40. The study is the first, to our knowledge, to report continuous multi-season monitoring of the Kashi River of the Ili River in Xinjiang, China, based on eDNA technology. Studies focusing on the ichthyofauna of the Kashi River have aimed to understand the composition, distribution, and seasonal variation of fish species in this region.

Despite the limited genetic information available for many endemic fish species in Xinjiang, we still monitored a total of 166 fish species across two-season, with 77 species detected in April and 137 species in September. A previous study conducted from 2012 to 2014 investigated fish resources in the upper, middle, and lower reaches of the Ili River in Xinjiang, China, and collected 27 fish species belonging to 6 orders, 9 families, and 23 genera2. In the present study, the dominant species detected through eDNA monitoring showed a high degree of consistency with those captured using traditional trawling methods, such as Diptychus maculatus, Gymnodiptychus dybowskii and Schizothorax eurystomus, indicating the reliability of eDNA for assessing fish community composition in this river system3.

The predominance of Cyprinidae, along with the high representation of Gobionidae and Xenocyprididae, reflected the typical fish community structure expected in temperate freshwater ecosystems such as the Ili River2. These findings were in line with the ecological characteristics of the region, where common cyprinid species are known to thrive in flowing, nutrient-rich waters2. The ability of eDNA to capture these dominant taxa further supports its reliability as a tool for assessing fish biodiversity in large river systems. Moreover, the taxonomic resolution achieved in this study underscores the potential of eDNA for long-term ecological monitoring and conservation planning in similar river ecosystems.

Remote habitats support a wide range of fish species, including numerous endemics and commercially important taxa. Research on fish diversity in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region has gained attention in recent decades due to concerns about the development of cascade hydropower plants, overfishing, habitat degradation, invasive species, and the impacts of climate change2,41. Unlike traditional survey methods, eDNA enables the detection of species without the need for direct observation or capture, which minimizes environmental impact and reduces sampling bias42,43. This method is particularly advantageous in detecting rare, elusive, or invasive species that might otherwise go unnoticed using conventional approaches14.

Moreover, eDNA analysis offers a cost-effective and time-efficient alternative to labor-intensive fieldwork, as it allows for the simultaneous detection of multiple species through metabarcoding techniques11,44. The non-invasive nature of eDNA sampling also makes it suitable for monitoring protected areas or species under conservation concern. However, challenges such as DNA degradation, false positives due to contamination, and varying detectability depending on environmental conditions highlighted the need for methodological standardization and validation across different habitats45,46,47. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen the combination of traditional and molecular measurement methods19. Overall, the integration of eDNA tools into the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region fish biodiversity assessments provides valuable insights into ecosystem health and helps inform conservation and management strategies in a rapidly changing environment.

eDNA could be applied to monitor seasonal variations in fish communities

eDNA has demonstrated significant potential for monitoring the seasonal variation of fish communities, providing a non-invasive and efficient approach to capture temporal biodiversity dynamics48. Our research revealed significant differences in fish composition between two-season. The findings align with previous studies that emphasize the importance of multi-season monitoring for capturing biodiversity patterns in freshwater ecosystems14,39. Furthermore, eDNA can provide insights into migratory behaviors and the presence of transient or cryptic species that are challenging to capture using conventional methods49.

Due to the lack of environmental data at some stations, this study was unable to analyze fish movement in conjunction with environmental factors. Nonetheless, survey results indicated similarities in fish composition among neighboring stations, such as SE05, SE06, and SE07 in April. Similarly, in September, the fish composition at stations UE1 to UE05 were comparable (Fig. 7). These observations suggested minimal differences in fish composition within similar environmental contexts. Seasonal environmental factors, such as water temperature, flow rate, and biological activity, can influence eDNA detection rates, making it a powerful tool for understanding the interplay between fish community dynamics and environmental variables50. Building on these findings, future research should further integrate eDNA technology with environmental monitoring to explore the dynamic changes in fish communities under varying ecological conditions.

Moreover, habitat complexity significantly influences fish distribution and abundance. Areas characterized by diverse structural elements, such as submerged vegetation and rocky substrates, tend to support higher fish diversity by offering essential shelter and foraging opportunities51. We observed clear differences in fish community composition between upstream and downstream sites (SE01 and SE16 in April; UE01 and UE21 in September), as indicated by NMDS ordination patterns. Understanding these relationships is vital for effective fishery management and conservation efforts, particularly in light of changing environmental conditions due to climate change52. Incorporating environmental data into fish monitoring programs can enhance our understanding of fish populations and help inform strategies for their sustainable management53.

Despite the promising potential of eDNA technology for assessing fish diversity in the Ili River, several challenges such as DNA degradation rates, sampling frequency, and methodological standardization must be addressed to enhance the accuracy and reliability of eDNA data in capturing seasonal trends. The high flow rates in rivers can result in eDNA transport over long distances, complicating the interpretation of local biodiversity14. eDNA monitoring results in this study identified some marine fish species, such as Yellowfin Seabream Acanthopagrus latus, Large Yellow Croaker Larimichthys crocea, Japanese Grenadier Anchovy Coilia nasus, and Spotted Scat Scatophagus argus. In addition, we also detected a considerable number of non-native freshwater species, such as Rasbora atridorsalis, Channa marulius, Monopterus albus, and Plecoglossus altivelis.

One common explanation is taxonomic misassignment, which may occur when closely related freshwater and marine taxa share highly conserved gene regions, leading to incorrect matches during sequence alignment54,55. Anthropogenic contamination is another possible cause. Marine DNA can be introduced into freshwater systems through wastewater discharge, aquaculture runoff, or seafood processing facilities56. Additionally, the transport of eDNA across environments via water flow or atmospheric deposition has also been proposed as a potential mechanism, though this remains relatively rare and often difficult to confirm14. These findings emphasize the need for cautious interpretation of eDNA results and the importance of verifying unexpected taxa through ecological plausibility and database curation. Our study complemented the regional reference database and provided important information for future studies.

Spatial distribution of fish communities in Kashi River

Fish surveys in remote areas, have certain limitations and potential challenges, so the use of eDNA technology provides new methods and ideas for monitoring biodiversity in these areas20. We compared the results of other studies to show the composition of indigenous fish. It is noteworthy that two of the sampling sites in this study—Kashi River at Nileke (S14) and Yamaduh River section (S21)—correspond to locations (C and E, respectively) surveyed in the previous trawling-based study2. In the previous survey, only 9 species were recorded at each of these sites. In contrast, our eDNA-based monitoring detected 31 species in April and 19 species in September at the Nileke site, and 22 species in April and 37 species in September at the Yamaduh River section. These results suggest that eDNA metabarcoding can capture a substantially higher level of fish diversity compared to traditional trawling methods, especially in complex or under-sampled habitats2.

Challenges remain in using eDNA, particularly in accounting for water flow dynamics, which can influence eDNA transport and lead to false positives or negatives23. However, advancements in metabarcoding techniques and predictive modeling have enhanced the reliability of eDNA for studying spatial patterns in fish communities, offering valuable insights for managing and conserving remote ecosystems8,14,57. This method has proven effective in identifying both endemic species and invasive threats, aiding in the conservation of unique ecosystems9,15,17,58. Spatial resolution can be improved by sampling across multiple sites, allowing researchers to map species distributions and pinpoint biodiversity hotspots59.

We identified a strong spatial distribution pattern of fish eDNA within the different river basins (Figs. 4, 7). Multiple possible reasons may cause differences in the distribution of fish, such as eDNA transport14,23 and the effects of human activities60. In the lower reaches of the Kashi River, sampling sites with high levels of human activity, such as the Tuohai Power Station, exhibited a reduced diversity of fish species. This may be due to human activities, including agricultural expansion, urbanization, overfishing and water pollution, which severely disrupted fish communities and led to a significant decline in fish diversity54,58,61. This study showed eDNA technology offers significant potential for advancing freshwater fish monitoring in the Kashi River in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Despite current challenges, ongoing methodological and technological improvements, coupled with targeted research efforts, will enhance its applicability and reliability.

Conclusion

Our study successfully revealed the fish diversity and community composition of the Kashi River in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region through two-season of systematic spatial sampling based on eDNA technology. A total of 166 fish species (77 in April and 137 in September) were detected in the two-season, of which 153 were freshwater fish (73 in April and 124 in September). In summary, our study was the first to continuously monitor fish diversity in the remote watershed of the Kashi River using eDNA technology. Our case study demonstrated that eDNA technology can be an effective tool for rapidly monitoring the composition and distribution of fish diversity in the Kashi River, a tributary of the Ili River in Xinjiang, China. Moreover, our findings highlight the need for continued monitoring of fish stocks in the region, which will help assess its biodiversity conservation and restoration measures.

Data availability

All sequencing raw data were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive with Temporary Submission ID: SUB14878961. Data is available after the indicated release date via the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1188641, accessed on 1 June 2025.

Change history

22 September 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Funding information section was missing from this article and should have read 'This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Project of Xinjiang (2022B02006-2) and the Taishan Scholars Program.' The original article has been corrected.

References

Ren, M. L. et al. Fish Resources and Fishery of Ili River 1–5 (Heilongjiang: Science and Technology of Heilongjiang Press, 1998).

Cai, L. Q. et al. Species diversity and dominant fish species in different reaches of the Ili river, Xinjiang. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 41(4), 819–826. https://doi.org/10.7541/2017.102 (2017).

Cai, L. G., Niu, J. G., Li, H. & Liu, J. Study on micro-environment at the spawning fields of Gymnodiptychus dybowskii and Diptychus maculates in the Kunes River. Arid Zone Res. 30(1), 144–148 (2013).

Abrunhosa, M. et al. Water resources management for a sustainable nexus of hydrogeoethics and societal well-being. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 10(2), 97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-024-01085-4 (2024).

Isupova, M. V. The effects of the Ili River runoff and water regulation function of the delta on the changing water level of Balkhash lake depending on the delta forest coverage. Water Resour. 46(Suppl 1), S29–S42. https://doi.org/10.1134/S009780781907011X (2019).

Xiong, F. et al. Methodology for fish biodiversity monitoring with environmental DNA metabarcoding: The primers, databases and bioinformatic pipelines. Water Biol. Secur. 1(1), 100007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watbs.2022.100007 (2022).

Fowler, C. M. et al. Viability of high-frequency environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling as a fish enumeration tool. Ecol. Indic. 166, 112384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112384 (2024).

Thomsen, P. F. & Willerslev, E. Environmental DNA-An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 183, 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.019 (2015).

Dejean, T. et al. Persistence of environmental DNA in freshwater ecosystems. PLoS ONE 6(8), e23398. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023398 (2011).

Taberlet, P., Coissac, E., Hajibabaei, M. & Rieseberg, L. H. Environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. 21(8), 1789–1793. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05542.x (2012).

Taberlet, P., Bonin, A., Zinger, L. & Coissac, E. Environmental DNA: For biodiversity research and monitoring. Oxford Univ. Press https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198767220.001.0001 (2018).

Carvalho, D. C. & Leal, C. G. Steps forward in biomonitoring 2.0: eDNA Metabarcoding and community-level modelling allow the assessment of complex drivers of Neotropical fish diversity. Glob. Chang. Biol. 29(7), 1688–1690. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16596 (2023).

Bohmann, K. et al. Environmental DNA for wildlife biology and biodiversity monitoring. Trends Ecol. Evol. 29(6), 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.04.003 (2014).

Deiner, K. et al. Environmental DNA metabarcoding: Transforming how we survey animal and plant communities. Mol. Ecol. 26(21), 5872–5895. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14350 (2017).

Marques, V. et al. Use of environmental DNA in assessment of fish functional and phylogenetic diversity. Conserv. Biol. 35(6), 1944–1956. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13802 (2021).

Lu, Q., Liu, Y., Zhao, J. & Yao, M. Successive accumulation of biotic assemblages at a fine spatial scale along glacier-fed waters. IScience 27(4), 109476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.109476 (2024).

Lopes-Lima, M. et al. Rapid eDNA survey reveals a unique biodiversity hotspot: the Corubal River, West Africa. Bioscience 74(6), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biae036 (2024).

Boivin-Delisle, D. et al. Using environmental DNA for biomonitoring of freshwater fish communities: Comparison with established gillnet surveys in a boreal hydroelectric impoundment. Environ. DNA 3(1), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.135 (2021).

Czeglédi, I. et al. Congruency between two traditional and eDNA-based sampling methods in characterising taxonomic and trait-based structure of fish communities and community-environment relationships in lentic environment. Ecol. Ind. 129, 107952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107952 (2021).

Bylemans, J., Gleeson, D. M., Hardy, C. M. & Furlan, E. Toward an ecoregion scale evaluation of eDNA metabarcoding primers: A case study for the freshwater fish biodiversity of the Murray-Darling Basin (Australia). Ecol. Evol. 8(17), 8697–8712. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4387 (2018).

Laporte, M. et al. Proper environmental DNA metabarcoding data transformation reveals temporal stability of fish communities in a dendritic river system. Environ. DNA 3(5), 1007–1022. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.224 (2021).

Jia, H., Xia, M. X., Zhang, T. & Zhang, H. Rapid monitoring of aquatic organism biodiversity based on environmental DNA in a medium-sized reservoir. Fishes 9, 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes9100396 (2024).

Jia, H., Zhang, H. & Xian, W. W. Fish diversity monitored by environmental DNA in the Yangtze River mainstream. Fishes 7(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes7010001 (2022).

Buxton, A. et al. Optimising sampling and analysis protocols in environmental DNA studies. Sci. Rep. 11, 11637. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91166-7 (2021).

Strickler, K. M., Fremier, A. K. & Goldberg, C. S. Quantifying effects of UV-B, temperature, and pH on eDNA degradation in aquatic microcosms. Biol. Conserv. 183, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.038 (2015).

Majaneva, M. et al. Environmental DNA filtration techniques affect recovered biodiversity. Sci. Rep. 8, 4682. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23052-8 (2018).

Liang, Z. et al. Soil characteristics and microbial community response in rare earth mining areas in southern Jiangxi Province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 56418–56431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14337-z (2021).

Buehler, B. et al. Rapid quantification of DNA libraries for next-generation sequencing. Methods 50(4), S15–S18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.004 (2010).

Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahe, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 4, e2584. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2584 (2016).

Martin, G. D. & Coetzee, J. A. Pet stores, aquarists, and the internet trade as modes of introduction and spread of invasive macrophytes in South Africa. Water SA 37, 371–380. https://doi.org/10.4314/wsa.v37i3.68488 (2011).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30(14), 3059–3066. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkf436 (2002).

Zhang, H., Yoshizawa, S., Iwasaki, W. & Xian, W. W. Seasonal fish assemblage structure using environmental DNA in the Yangtze estuary and its adjacent waters. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 515. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00515 (2019).

Guo, Y., Zhang, R. M. & Cai, L. G. Fishes of Xinjiang (Xinjiang Science and Technology Press, 2012).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022).

Conway, J. R., Lex, A. & Gehlenborg, N. UpSetR: An R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics 33(18), 2938–2940. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btx364 (2017).

Bray, J. R. & Curtis, J. T. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 27(4), 326–349. https://doi.org/10.2307/1942268 (1957).

Ramette, A. Multivariate analyses in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 62, 142–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941 (2007).

Xin, N. et al. Environmental DNA metabarcoding reveals fish diversity, community assembly and one invasive species prevalence in a National Park of Liaohe in September. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1403700. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1403700 (2024).

Deng, J. et al. eDNA metabarcoding reveals differences in fish diversity and community structure in Danjiang River. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 29460. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80907-z (2024).

Cui, W., Liu, J., Jia, J. & Wang, P. F. Terrestrial ecological restoration in China: identifying advances and gaps. Environ. Sci. Eur. 33(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-021-00563-2 (2021).

Thalinger, B., Wolf, E. & Traugott, M. Monitoring spawning migrations of potamodromous fish species via eDNA. Sci. Rep. 9, 15388. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51398-0 (2019).

Miyata, K., Inoue, Y. & Amano, Y. Comparative environmental RNA and DNA metabarcoding analysis of river algae and arthropods for ecological surveys and water quality assessment. Sci. Rep. 12, 19828. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23888-1 (2022).

Rishan, S. T., Kline, R. J. & Rahman, M. S. Applications of environmental DNA (eDNA) to detect subterranean and aquatic invasive species: a critical review on the challenges and limitations of eDNA metabarcoding. Adv. Environ. 12, 100370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envadv.2023.100370 (2023).

Tsuji, S. et al. Quantitative environmental DNA metabarcoding shows high potential as a novel approach to quantitatively assess fish community. Sci. Rep. 12, 21524. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25274-3 (2022).

Lacoursière-Roussel, A., Rosabal, M. & Bernatchez, L. Estimating fish abundance and biomass from eDNA concentrations: Variability among capture methods and environmental conditions. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 16(6), 1401–1414. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12522 (2016).

Zainal Abidin, D. H. et al. Assessing a megadiverse but poorly known community of fishes in a tropical mangrove estuary through environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding. Sci. Rep. 12, 16346. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19954-3 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Species identification and biomass assessment of Gnathanodon speciosus based on environmental DNA technology. Ecol. Indic. 160, 111821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.111821 (2023).

Hervé, A. et al. Spatio-temporal variability of eDNA signal and its implication for fish monitoring in lakes. PLoS ONE 17(8), e0272660. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272660 (2022).

Klymus, K. E., Richter, C. A., Chapman, D. C. & Paukert, C. Quantification of eDNA shedding rates from invasive bighead carp Hypophthalmichthys nobilis and silver carp Hypophthalmichthys molitrix. Biol. Invasions 183, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-0885-z (2015).

Thomsen, P. F. et al. Monitoring endangered freshwater biodiversity using environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. 21(11), 2565–2573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05418.x (2012).

Messmer, V. et al. Habitat biodiversity as a determinant of fish community structure on coral reefs. Ecology 92(12), 2285–2298 (2011).

Verhelst, P. et al. Enhancing our understanding of fish movement ecology through interdisciplinary and cross-boundary research. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 33(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-022-09741-8 (2023).

Huang, S. Q., Yoshitake, K., Watabe, S. & Asakawa, S. Environmental DNA study on aquatic ecosystem monitoring and management: Recent advances and prospects. J. Environ. Manag. 323, 116310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116310 (2022).

Li, W. Q., Jia, H. & Zhang, H. Evaluating the effectiveness of the eRNA technique in monitoring fish biodiversity - A case study in the Qingdao offshore, China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 51, e02888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2024.e02888 (2024).

Collins, R. A. et al. Non-specific amplification compromises environmental DNA metabarcoding with COI. Methods Ecol. Evol. 10, 1985–2001. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13276 (2019).

Ficetola, G. F., Taberlet, P. & Coissac, E. How to limit false positives in environmental DNA and metabarcoding?. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 16, 604–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12508 (2016).

Barnes, M. A. & Turner, C. R. The ecology of environmental DNA and implications for conservation genetics. Conserv. Genet. 17(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-015-0775-4 (2016).

Valentini, A. et al. Next-generation monitoring of aquatic biodiversity using environmental DNA metabarcoding. Mol. Ecol. 25(4), 929–942. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13428 (2016).

Sigsgaard, E. E. et al. Population-level inferences from environmental DNA-Current status and future perspectives. Evol. Appl. 13(2), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12882 (2020).

Li, F., Zhang, X., Xie, Y. & Wang, J. Sedimentary DNA reveals over 150 years of ecosystem change by human activities in Lake Chao, China. Environ. Int. 133, 105214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105214 (2019).

Talukdar, G., Sarma, A. K. & Bhattacharjya, R. K. Assessment of land use change in riverine ecosystem and utilizing it for socioeconomic benefit. Environ. Monit. Assess. 194(11), 841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-022-10495-w (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all staff and students involved in laboratory and field eDNA sampling.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Project of Xinjiang (2022B02006-2) and the Taishan Scholars Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: H.J. and H.Z.; Investigation: H.J., T.Z. and J.W.H.; Data curation: J.G.N, T.Z. and H.J.; Methodology: J.G.N., H.J. and H.Z.; Formal analysis: J.G.N. H.J., and T.Z.; Software: H.J. and T.Z.; Visualization: J.G.N. and H.J.; Validation: H.J. and T.Z.; Project administration: J.G.N. and H.Z.; Writing-original draft: J.G.N. and H.J.; Writing-review & editing: L.Y.H. and H.Z.; Funding acquisition: J.G.N. and H.Z.; Supervision: L.Y.H. and H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, J., Jia, H., Zhang, T. et al. Harnessing eDNA technology to identify fish diversity and distribution in the Kashi River, a tributary of the Ili River, Xinjiang, China. Sci Rep 15, 28187 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14079-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14079-9