Abstract

Escherichia coli represents a significant concern for food safety, water quality, medical applications, and environmental health, necessitating effective detection methods. This study presents a reduced graphene oxide-based biosensor for the sensitive and specific detection of E. coli DNA. The functionalized reduced graphene oxide was successfully synthesized using a modified Hummers’ method, followed by a hydrothermal reduction step. Structural, morphological, and chemical properties of the reduced graphene oxide were confirmed through Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and X-ray diffraction. The biosensor incorporates functionalized reduced graphene oxide linked to amino-modified probe DNA sequences specific to E. coli markers, providing stability and selective hybridization. Detection of E. coli DNA in the range of 0–476.19 fM is achieved by measuring absorbance changes at 273 nm, where an increase in absorbance indicates the presence of complementary E. coli single-stranded DNA. Performance testing with various DNA concentrations revealed a linear relationship, achieving a limit of detection of 80.28 fM and demonstrating high selectivity against non-target bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis, Enterococcus, Vibrio proteolyticus, and Staphylococcus. Optimization efforts identified the amino-E.coli BL21 probe as the only probe capable of detecting E. coli DNA. The reduced graphene oxide-based biosensor holds promise for rapid detection in pathogen monitoring, clinical diagnostics, and environmental analysis, paving the way for enhanced DNA biosensing technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Escherichia coli is a Gram-negative bacterium with significant importance in medical, environmental, and food safety sectors1. Although most E. coli strains are harmless components of the natural gut microbiota2certain pathogenic strains can cause severe illnesses such as gastroenteritis3urinary tract infections4and potentially life-threatening conditions like hemolytic uremic syndrome5,6. Timely and accurate detection of pathogenic E. coli is crucial for effective clinical management, particularly given the ongoing emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains1,7. Beyond healthcare, E. coli is widely recognized as a key indicator of fecal contamination in environmental and food systems. Its presence contaminates water sources, leading to the transmission of waterborne diseases, and poses significant food safety risks when detected in products such as raw meat and unpasteurized dairy8,9,10,11. These widespread risks highlight the need for rapid, reliable E. coli detection methods.

Traditional methods for detecting E. coli deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR)12,13enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)14and fluorescence-based assays15 often face limitations in speed, cost, and sensitivity. These shortcomings necessitate the development of innovative and efficient detection technologies, such as biosensors. Biosensors combine biological recognition elements with physical transducers to detect specific biological molecules, offering a promising solution for rapid and sensitive detection16,17,18,19. Based on the type of transducer, biosensors are classified into categories such as electrochemical and optical types16. Among optical biosensors, absorbance-based biosensors are particularly advantageous for DNA detection due to their simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and ability to detect low DNA concentrations20,21,22. These sensors measure changes in absorbance when a target molecule, such as DNA, interacts with the biosensor’s recognition element, producing an optical signal that correlates with target concentration, enabling rapid quantitative analysis23.

The performance of these biosensors can be enhanced by incorporating nanomaterials, which improve sensitivity and signal stability. Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) is a promising candidate for biosensing applications due to its unique structural and optical properties24,25,26. The high surface-area-to-volume ratio of rGO, combined with its excellent dispersibility in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer, facilitates the efficient adsorption of and interaction with biomolecules. These characteristics significantly enhance the sensitivity and specificity of detection, making rGO-based biosensors highly effective for a wide range of analytical applications27,28. Compared to graphene oxide (GO), rGO exhibits superior electronic conductivity, greater surface reactivity, and stronger optical absorption in the UV-Vis range, which are critical for improving signal sensitivity in absorbance-based biosensors29,30. Furthermore, compared to other commonly used nanomaterials, such as gold nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes, rGO offers a favorable combination of cost-effectiveness, biocompatibility, and ease of functionalization31,32,33,34. These advantages make rGO a versatile and attractive material for developing next-generation biosensors.

Numerous studies have explored biosensors for detecting E. coli DNA, using fluorescence35,36electrochemical37,38,39,40and colorimetric41,42,43 techniques. While these methods have demonstrated rapid and accurate detection, they often face significant limitations, such as reliance on expensive reagents, complex fabrication processes, and reduced sensitivity in complex real-world samples, such as environmental water or food matrices containing interfering substances. These challenges highlight the need for biosensor platforms that are both technically robust and practical for real-world use.

In this study, we address current limitations in DNA biosensing by developing a novel absorbance-based biosensor platform using functionalized rGO and a customized amino probe for the rapid, sensitive, and cost-effective detection of E. coli DNA. The rGO is synthesized using a modified Hummers’ method, followed by hydrothermal reduction to enhance conductivity and surface reactivity. The synthesized rGO is characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to confirm its morphological, structural, and chemical attributes. The biosensor’s detection performance in the femtomolar (fM) range from 0 to 476.19 fM is evaluated by monitoring UV-Vis absorbance changes at 273 nm, a wavelength sensitive to DNA hybridization events. By leveraging the unique optical and structural features of rGO, the sensor achieves high sensitivity, specificity, and cost-effectiveness for DNA detection across various sample types. Its simple design and low fabrication cost make it suitable for scalable deployment in point-of-care diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety testing, offering a practical and efficient alternative to conventional detection methods.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and probe to detect E. coli DNA

The chemicals used in this research without further purification were Graphite (C, Shanghai Zhanyun Chemical Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China), Potassium permanganate (KMnO4, 99.5%, Shanghai Zhanyun Chemical Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China), Nitric acid (HNO3, 69%, Merck, Germany), Sodium nitrate (NaNO3, 98.5%, Shanghai Zhanyun Chemical Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China), Sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95.0–97.0%, Merck, Germany), Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%, Xilong, China), Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%, Merck, Germany) and deionized water (DI). The chemicals used for these extractions include the 2% w/v CTAB (Biobasic, Canada), 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 (Biobasic, Canada), 20 mM EDTA (Biobasic, Canada) and 1.4 M Sodium chloride NaCl (Merck, Germany). The oligonucleotide probe was designed to specifically target E. coli, using the sequence amine-5′- CGGATGCGGCGTGAACGCCT − 3′. All probes listed in Table 1 were purchased from PHUSA Genomics Co., Ltd, Can Tho, Vietnam.

Synthesis of reduced graphene oxide

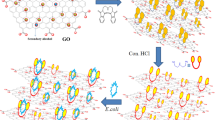

Schematic of the synthesis of rGO. This figure was created by the first author, Chau Nguyen Minh Hoang, using Microsoft PowerPoint 365 (https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/powerpoint) and Biorender (https://www.biorender.com/).

Graphene oxide was synthesized following the protocol in previous work48 and outlined in Fig. 1. In brief, 1 g of graphite was suspended in 2 ml of nitric acid (HNO3) along with 1.5 g of potassium permanganate (KMnO4). This mixture was then placed in a 250 mL Duran flask and subjected to microwave irradiation at 800 W for 60 s to produce exfoliated graphite (EG). Next, 2 g of the synthesized EG was combined with 8 g of KMnO4 and 1 g of sodium nitrate (NaNO3). This blend was gradually added to 160 ml of sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95–97%) while maintaining a temperature of 5 °C using an ice bath, followed by stirring for 30 min. After this period, the mixture was removed from the ice bath and gently heated to 45 °C, continuing to stir for 2 h. Distilled water (DI) was gradually added until the purple fumes dissipated while maintaining magnetic stirring at 95 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, 10 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%) and 3–5 mL of hydrochloric acid (HCl, 3.6%) were added to eliminate KMnO4, MnO2, and other residual metal ions, resulting in the formation of the GO solution. The GO solution was then centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 30 min and washed with DI until a neutral pH was achieved. Finally, the product was vacuum-dried at 40 °C in the oven (Memmert UN110 Laboratory Oven, Germany).

The rGO was prepared using the modified hydrothermal method from previous research49. Briefly, 0.1 g of GO was suspended in 40 mL of DI. The mixture was then transferred to an 80 ml Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave, heated to 175 οC for 10 h, and then allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. The chosen temperature of 175 οC was sufficient to enhance the efficient reduction while preserving the hydroxyl and carboxyl functionalized groups, which are essential for maintaining dispersibility in aqueous media and facilitating bioconjugation with DNA probes50. The resulting mixture was filtered through a microporous membrane (0.22 μm), yielding a yellowish solution.

Material characterization

The morphological characteristics of the synthesized material were analyzed using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, HITACHI S-4800, Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Before imaging, the samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of platinum (Pt) to enhance conductivity. Images were acquired at an accelerating voltage of 5.0 kV with a working distance of 6.2 to 6.3 mm.

The crystallographic structure was determined by XRD using a MiniFlex600 diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), operated with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at 40 kV and 15 mA. Prior to analysis, samples were dried at 100 °C for 24 h, finely ground, and subsequently scanned over a 2θ range of 5° to 80° with a step size of 0.02° at 25 °C.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy was conducted using a JASCO FT/IR-4600 type A spectrometer (JASCO, Japan) equipped with an ATR PRO ONE accessory (Serial No. B132661809) at an incident angle of 45°. Spectra were recorded from 4000 to 400 cm− 1 at a 4 cm− 1 resolution, accumulating 16 scans. Analysis was performed using a TGS detector and a cosine apodization function at a scan speed of 2 mm/s. The system operated in auto mode with zero filling enabled, and the results were processed using Spectra Manager™ Suite software. All measurements were conducted under standard operating conditions as recommended by the respective manufacturers.

DNA extraction method

The microbiology and genetics laboratory at Hanoi University of Science and Technology in Hanoi, Vietnam, provided five bacterial samples for this study, including E. coli, Bacillus subtilis, Enterococcus, Vibrio proteolyticus, and Staphylococcus. The extraction process was conducted according to the protocol described in51. Before the sterilization process, the pH of the lysis buffer was adjusted to 5.0. A volume of 1.5 mL of bacterial suspension was added to a 2.0 mL Eppendorf tube and centrifuged (Hettich MIKRO 200R, Germany) at 8,000×g for 5 min at room temperature to pellet the cells. After discarding the supernatant, the cell pellet was resuspended in 740 µL of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. Subsequently, 20 µL of 100 mg/mL Lysozyme was added to degrade the cell wall, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C using a dry bath incubator (Biologix tekcovina, USA). Following this, 40 µL of 10% SDS and 8 µL of Proteinase K (10 mg/mL) (Biobasic, Canada) were introduced to facilitate protein digestion and membrane disruption. The sample was then incubated at 56 °C for 3 h. Gradually, 100 µL of 5 M NaCl and heated CTAB/NaCl (Merck, Germany) at 65 °C were added to precipitate the DNA. After 10 min at 65 °C, the material was extracted using chloroform: isoamyl alcohol from Sigma Aldrich to separate the DNA from contaminants. Following centrifugation at 12,000×g for 10 min at room temperature, the aqueous phase containing the DNA was transferred to a fresh tube. This extraction procedure was repeated until no white protein layer remained. The DNA was then precipitated with 100% Ethanol (Merck, Germany) and stored at -20 °C for 2 h or overnight. After centrifuging for 15 min at 12,000×g at 4 °C (Hettich MIKRO 200R, Germany), the DNA pellet was washed with 50 µL of 70% Ethanol to eliminate contaminants and salts. Once dried, the pellet was resuspended in TE buffer for storage. Isolated DNA should be stored at -20 °C for future use. All DNA samples in this study exhibited OD260/280 ratios around 2.0, indicating high purity.

Absorbance measurements of DNA using the UV-Vis method

In our experiment, all probes were diluted to 30 nM in TE buffer. DNA solutions were prepared by dissolving and diluting them in 1×TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). E. coli, V. proteolyticus, Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, and B. subtilis DNAs were pretreated by heating at 98 °C for 10 min and then placed in an ice bath for 2 min to prevent reannealing. The rGO suspension was ultrasonicated to ensure proper dispersion and prevent aggregation. Then, 1000 µL of the suspension was added to a 10 mm cuvette, with TE buffer as the solvent. Next, 100 µL of the 30 nM probe was added, and the mixture was incubated for 5 min. The concentrations of rGO before and after adding the probe were 0.129 mg/mL and 0.117 mg/mL, respectively. After gently vortexing, the mixture was incubated at room temperature for an additional 5 min to facilitate optimal probe adsorption onto the rGO surface. Finally, we introduced 100 µL of DNA into the cuvettes, yielding concentrations ranging from 83.33 to 476.19 fM. At each step, absorbance measurements were performed using a DeNovix UV–visible spectrometer (Model: DS-11 FX+). All experiments were performed in triplicate and independently repeated at least three times.

Results and discussions

Characterization of rGO materials

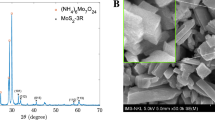

The characteristics of the prepared materials are detailed as follows: (a) The SEM image, obtained using the HITACHI-S4800, confirms the nanosheet morphology, exhibiting enhanced contrast. (b) The XRD pattern was generated using the Rigaku MiniFlex600. Furthermore, (c) the FTIR spectrum was acquired using the Jasco 4600 spectrometer (Jasco, Japan).

The material was characterized through SEM, XRD, and FTIR to assess its morphology and structural properties, as well as to analyze the chemical bonds and functional groups present. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, the SEM image reveals the material’s layered, sheet-like structures. This suggests a high surface area with numerous active sites, highlighting its potential suitability for catalytic or adsorption applications. The XRD pattern displays two prominent peaks at 26.52° and 44.54°, corresponding to the (002) and (100) crystal planes, respectively (Fig. 2b). These peaks align with the characteristic diffraction pattern of rGO as referenced in JCPDS No. 96-101-106152. The (002) peak suggests the restoration of graphene-like structures with interlayer spacing, while the (100) peak confirms in-plane structural ordering. Additionally, the FTIR spectrum reveals characteristic bands, including a broad peak around 3100–3700 cm⁻¹ attributed to O–H stretching (related to hydroxyl groups or water molecules), a peak near 1600 cm⁻¹ signifying C = O stretching (associated with carbonyl groups), a peak between 2800 and 3000 cm− 1 corresponds to the C-H stretching vibrations, and bands within the range of 1000–1300 cm⁻¹ corresponding to C–O or C–O–C stretching vibrations53 (Fig. 2c). The data indicate the presence of oxygen-containing functional groups, particularly the carboxyl group, which will be further investigated as a bridge component for this biosensor.

To confirm the successful reduction from GO to rGO, their structural and chemical properties were compared. SEM image (Supplementary Fig. S1a) shows that GO exhibits a distinctly layered and crumpled morphology, whereas rGO displays a more compact and less aggregated structure. The XRD pattern of GO reveals a sharp diffraction peak (001) at 2θ ≈ 10.46°, indicating oxidized layered structures (Supplementary Fig. S1b). In the rGO pattern, this peak vanished and was replaced by a broad (002) peak near 2θ = 26°, confirming partial restoration of the graphitic framework. These structural changes were chemically validated by FTIR spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. S1c). The FTIR spectrum of GO displays intense bands for C–O–C, O–H, C–OH, and C = O groups, while rGO exhibits significantly reduced intensities for these oxygenated functionalities, consistent with efficient reduction.

Collectively, these findings validate the successful reduction of graphene oxide into rGO, preserving its nanosheet morphology with optimized functional groups and highlighting its potential in biosensing applications.

Absorbance biosensors to detect E. coli DNA

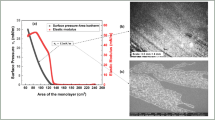

The adsorption spectra of the hybridization of rGO solution with (a) probes and E. coli DNA, 0 fM represents the rGO + amino-probe sample, (b) E. coli without probes are presented, 0 fM represents the rGO only. (c) A linear relationship exists between DNA concentration and absorbance values over the concentration range of 0-476.19 fM, measured at a wavelength of 273 nm. The error bars indicate the standard deviations from nine measurements. (d) The percentage change in the absorbance of these three different conditions upon the addition of 476.19 fM E. coli DNA and the equivalent volume of deionized (DI) water.

In this experiment, the biosensor, modified with a specific probe for E. coli DNA, was analyzed using UV-Vis spectroscopy to monitor absorbance changes indicative of DNA binding events. The reduced graphene oxide containing 1000 µL was first exposed to a specific probe amine-5′- CGGATGCGGCGTGAACGCCT − 3′ to functionalize the sensor. After sufficient time for the probe to interact with the material, various concentrations of E. coli DNA, ranging from 83.3 to 476.19 fM, were added stepwise to the solution. The absorbance spectra of the rGO were measured across wavelengths from 220 to 700 nm, with a particular focus on the absorbance at 273 nm. This specific wavelength was selected based on preliminary observations that revealed a significant absorbance response at 273 nm upon DNA binding. As the concentration of E. coli DNA increased, the result experienced a consistent rise in absorbance at 273 nm, suggesting effective DNA binding (Fig. 3a). The absorbance response at 273 nm is plotted against E. coli DNA concentration, revealing a linear relationship that demonstrates the sensor’s ability to quantitatively detect E. coli DNA (Fig. 3c). This trend is further confirmed by the percentage change in absorbance upon the addition of 476.19 fM (ΔA) analysis, where the data demonstrated a 54% increase in absorbance for the E. coli DNA-bound sensor (Fig. 3d). To evaluate the biosensor’s specificity, control experiments were performed using DI water instead of E. coli DNA. Interestingly, the addition of DI water produced an opposite trend compared to E. coli DNA, with the absorbance at 273 nm decreasing (Fig. 3d). The role of the DNA probe was further examined by omitting it from the sensing system. In the absence of the probe, a gradual decrease in absorbance intensity at 273 nm was observed (Fig. 3b). Quantitatively, the addition of DI water and the introduction of reduced graphene oxide with E. coli DNA but without the specific probe, resulted in absorbance changes of approximately − 73% and − 20%, respectively (Fig. 3d). These results confirm the biosensor’s high specificity for E. coli DNA detection.

To validate the superior performance of rGO, its sensing capability was compared directly to that of GO-based biosensors under identical experimental conditions. The GO-based biosensors, functionalized with the same NH2-modified probe, exhibited a higher baseline absorbance (Supplementary Fig. S2a) and a distinctly different response pattern upon exposure to increasing concentrations of E. coli DNA (Supplementary Fig. S2b). As the concentration of E. coli DNA increased, the absorbance at 273 nm decreased, showing a strong negative linear correlation (R2 = 0.97; Supplementary Fig. S2c). This trend contrasts sharply with the positive correlation observed in the rGO-based sensor.

The inverse response observed with the GO-based biosensors can be attributed to abundant oxygen-containing functional groups on GO, which promote non-specific adsorption of probe and target DNA molecules. Consequently, the surface of GO facilitates extensive non-specific interactions, thereby impeding the formation of specific probe-target duplexes and leading to diminished positive signaling compared to rGO. In contrast, rGO-based biosensors exhibited robust and highly linear positive detection responses, reflecting optimized surface chemistry and reduced non-specific background interactions. These findings demonstrate the superior detection capability of rGO-based sensors due to minimized non-specific binding, significantly enhancing their sensitivity and selectivity for detecting E. coli DNA relative to GO-based counterparts.

Overall, the results demonstrated a significant positive correlation between the intensity of the 273 nm wavelength and the concentrations of E. coli DNA, underscoring the potential of establishing a model based on this relationship. Hence, we develop a robust model that enables highly sensitive and specific detection of E. coli. The biosensor was calibrated by measuring the absorbance at 273 nm across a range of known E. coli DNA concentrations, with each measurement taken in triplicate at least three times. These measurements were then fitted to a linear equation as described below:

where y represents the absorbance of the sensor measured at 273 nm, and x is the concentration of E. coli DNA in femtomolar (fM). The linearity of this relationship, reflected by a correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.962, demonstrates the model’s potential to accurately predict DNA concentrations from absorbance measurements and vice versa.

To validate the biosensor model, we performed a series of spiking experiments with known concentrations of E. coli DNA (312.50 fM, 388.89 fM, and 450.00 fM). We then compared the estimated concentrations derived from the model to the actual spiked values. The results, including the estimated concentrations and their corresponding recovery rates, are shown in Table 2. The recovery rates span from 93.58 to 105.97%, demonstrating the model’s accuracy and reliability in estimating E. coli DNA concentrations.

To further evaluate the robustness and specificity of the sensing mechanism, we compared the sensor’s performance using both full-length extracted E. coli single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and a synthetic short complementary DNA sequence (5′-AGGCGTTCACGCCGCATCCG-3′). Supplementary Figure. S3 presents the absorbance spectra of the biosensors with synthetic ssDNA, alongside the corresponding calibration curve at 273 nm across varying DNA concentrations. The calibration equation derived for the synthetic ssDNA (y = 2 × 10− 4x + 0.152; R2 = 0.998 closely matches the linear relationship obtained for extracted ssDNA (Eq. 1). The identical slope in both equations indicates that the detection mechanism relies predominantly on hybridization specificity rather than the length of the DNA strands, as evidenced by consistent sensitivity and linearity with both DNA targets. Slight differences observed in the intercept values may be attributed to matrix effects or minor variations in binding dynamics, highlighting areas for future mechanistic investigation. These results underscore the platform’s versatility in detecting both naturally occurring and synthetic DNA targets.

The limit of detection (LOD) was then calculated using the 3-sigma method to determine the sensor’s sensitivity to low concentrations of E. coli DNA54. The calculated LOD was found to be 80.28 fM, demonstrating that the biosensor can reliably identify E. coli DNA at concentrations as low as 80.28 fM. Furthermore, the performance of the biosensors was examined after one month to evaluate their stability. The results in Fig. 4 showed that the absorbance at 273 nm for biosensors exposed to various E. coli DNA concentrations remained stable, with a relative difference of 47%, representing a slight decrease compared to the original value. However, this result still demonstrates the high potential of the proposed biosensors. In the next step, stability could be further enhanced by increasing the incubation time or optimizing the immobilization process.

As discussed above, the proposed biosensors operate through the hybridization of E. coli DNA with the NH2-probe immobilized on functionalized rGO, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The nanoscale properties of rGO, including a high surface-area-to-volume ratio and excellent dispersibility, facilitate the effective presentation of carboxylic (-COOH) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups. In our protocol, the immobilization of the NH2-modified probe onto rGO is primarily governed by optimized non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic attraction, and π–π stacking, rather than actual covalent peptide bond formation, since no EDC/NHS activation was used. This approach results in a stable and reliable sensing interface.

After five minutes of incubation to ensure complete probe binding, the rGO-probe complex was introduced to a sample containing either complementary DNA (full-length extracted or short synthetic sequence matching the probe) or non-complementary DNA (mismatching the probe). Hybridization events between the DNA and the probe were monitored using UV-Vis spectroscopy at 273 nm. Although hybridization occurs exclusively at the 21-nucleotide probe region, both full-length E. coli DNA and synthetic short DNA targets triggered similar physicochemical changes at the sensor interface. In the presence of complementary DNA, specific hybridization with the immobilized probe formed double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), significantly altering local molecular properties. Single-stranded DNA exhibits exposed bases and a flexible structure, resulting in a lower local dielectric constant. Upon hybridization, complementary base pairing yields a rigid, ordered double helix that reorganizes the surrounding hydration shell and increases the dielectric constant55. The alteration in dielectric properties modifies the electronic environment around the nucleobases, particularly affecting their π–π* electronic transitions responsible for UV absorption. The dsDNA structure also enhances base stacking interactions, further modulating absorbance properties. This change influences the optical properties, particularly the absorbance at 273 nm, where DNA bases strongly absorb. Nearly identical sensor responses to both synthetic short and full-length DNA targets indicate that the absorbance signal is predominantly governed by the local hybridization event rather than the overall DNA strand length. The absorbance intensity scaled proportionally with the concentration of complementary DNA. In contrast, exposure to non-complementary DNA resulted in negligible absorbance changes, as no hybridization occurred. This differential response enables the biosensor to discriminate between matching and non-matching DNA sequences with high specificity, as discussed in the following subsection.

Selectivity of proposed biosensors based on rGO nanosheets

(a) The relationship between DNA concentrations and the absorbance of five different kinds of DNA in the range of 0-476.19 fM measured at the wavelength of 273 nm. Error bars represent the standard deviations of seven measurements. (b) The percentage change in the absorbance of five different DNA bacteria.

The selectivity of the biosensor was evaluated by comparing its response to different kinds of bacteria, including E. coli, V. proteolyticus, Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, and B. subtilis DNAs. It is noteworthy that, alongside the same gram-negative bacterial group containing E. coli, which includes V. proteolyticus and Enterococcus, we also examined gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus and B. subtilis. The absorbance spectra of the proposed biosensors in contact with four different bacterial DNA samples are presented in Supplementary Fig. S4. The absorbance changes at 273 nm for the biosensors in contact with other DNA samples and varying concentrations are shown in Fig. 6a. As shown in Fig. 6a, the absorbance at 273 nm increased consistently with increasing concentrations of E. coli DNA, indicating a positive response. In contrast, the absorbance values for the non-target bacterial DNA (V. proteolyticus, Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, and B. subtilis) remained relatively constant and significantly lower across all tested concentrations, demonstrating minimal interferences with the E. coli DNA detection signal. Moreover, the graph shows the percentage change in absorbance (ΔA) for each bacterial DNA at 273 nm wavelength. E. coli DNA demonstrated a positive response, exhibiting a 54% increase in absorbance, while the other bacterial DNAs yielded negative responses. In particular, the gram-negative bacteria such as V. proteolyticus and Enterococcus showed decreases of approximately − 19% and − 28%, respectively. Furthermore, the gram-positive bacteria displayed similar or even lower negative responses compared to the gram-negative bacteria, with Staphylococcus at about − 28% and B. subtilis at -34% (Fig. 6b). The consistent decrease in absorbance observed with non-target bacterial DNA can be attributed to the absence of specific probe-target hybridization. Other factors, such as sample dilution or weak, non-specific interactions that fail to induce significant structural or electronic changes, may also contribute. Consequently, the sensor produces a strong, concentration-dependent absorbance signal exclusively with complementary E. coli DNA, showing minimal cross-reactivity with other bacterial DNAs. These results demonstrate the biosensor’s high selectivity, underscoring its reliability for detecting E. coli even in complex samples containing diverse bacterial DNA.

Effects of probes on sensing performance of proposed biosensors based rGO nanosheets

To further evaluate the most effective sensor for E. coli DNA detection, we explored the impact of various probes on the material. This experiment involved three different types of probes with the same sequence (BL21) but differing chemical modifications: NH2 (amine), thiol, and unmodified. Our goal was to assess which combination yielded the most effective biosensor response. The absorbance spectra of biosensors with different probes are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. Their absorbance at 273 nm, which changes with the E. coli DNA concentrations, is displayed in Fig. 7. Among these, the NH2-BL21 probe, which incorporated an NH2 group modification, demonstrated the highest absorbance compared to the BL21 probes with thiol modification and without modification (Fig. 7a). In contrast, the BL21 probes with thiol and no modification exhibited a decline in absorbance at 273 nm, showing an opposite trend to that of the BL21-NH2 probe. As the concentration of E. coli DNA increased, the absorbance at 273 nm for the sensors with BL21-thiol and unmodified BL21 decreased (Fig. 7a). Therefore, the combination with BL21-NH2 displayed a clear, positive correlation between absorbance at 273 nm and E. coli DNA concentration, indicating the highest sensitivity and effectiveness in binding to E. coli DNA. Furthermore, the performance of each probe was quantitatively assessed by illustrating the percentage change in absorbance (ΔA) in Fig. 7b. The NH2-BL21 probe exhibited a 54% increase in absorbance, while the other probes displayed decreases: -17% for the unmodified BL21 and − 18% for the BL21 probe modified with thiol.

Furthermore, the prior experiment demonstrated that probes with NH2 modifications can exhibit the highest effectiveness, indicating that the NH2 group can effectively bind to the material (reduced graphene oxide). We subsequently evaluated various DNA sequences containing the same NH2 group, specifically investigating three sequences unique to E. coli: BL21, membrane, and uidA. Each of these sequences was modified to incorporate the NH2 group. As shown in Fig. 7a, the BL21-NH2 displayed the highest absorbance signal among the three sequences with NH2 modifications. In contrast, the membrane-NH2 and uidA-NH2 exhibited a downward trend in absorbance values at 273 nm (Fig. 7a). The percentage change at this wavelength indicated that BL21-NH2 reached an increase of up to 54%, while membrane-NH2 decreased by -16%, followed by -22% for uidA-NH2 (Fig. 7b). These occurrences can be effectively interpreted by recognizing that these two sequences are not complementary with the E. coli DNA, leading to the fall for detection of the E. coli DNA. This finding demonstrated that the NH2-BL21 probe- combining the BL21 sequence with an NH2 functional group- produced the most effective response for E. coli DNA detection. The sensor provided a highly sensitive and selective detection of E. coli, which might be due to the binding affinity and signal response. As a result, the NH2-BL21 probe was considered the optimal design for E. coli detection in this biosensor.

The absorbance detection method utilizing reduced graphene oxide demonstrates several advantages over previously reported techniques, as shown in Table 3. With a detection range of 0–476.19 fM and a limit of detection of ~ 80.28 fM, this method achieves a lower detection threshold than Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and capacitive DNA sensors. However, it is less sensitive than electrochemical sensors (e.g., AuNP-based, which reaches ~ 50 fM)56,57. Its rapid detection capability, achieved through direct absorbance measurement, surpasses the moderate detection times of electrochemical and capacitive sensors, aligning with the rapid analysis offered by SPR and field-effect transistor (BioFET)-based sensors58,60. Additionally, the low cost and simplicity of the rGO-based method make it highly practical and portable, a significant advantage over the high-cost SPR systems. While some techniques, such as BioFET, exhibit higher sensitivity (1 fM) and portability, the rGO-based approach provides an ideal balance of affordability, practicality, and performance for real-world applications59. Compared to previous studies, this work introduces a key innovation. While earlier GO-based biosensors primarily focused on detecting whole E. coli cells through electrochemical methods, direct detection of E. coli DNA using an absorbance-based approach has not been reported61. In contrast, our study presents the first label-free, rGO-based absorbance biosensor specifically designed for E. coli DNA detection. This approach uniquely combines material simplicity, sequence specificity, and real-time detection capability. The proposed platform offers a promising, low-cost alternative with strong potential for point-of-care DNA diagnostics.

This practical, low-cost method enables sensitive and specific detection without complex instrumentation or amplification steps. These improvements largely stem from using rGO as a sensing platform. rGO offers several advantageous properties, including a high surface area, ease of functionalization, and strong affinity for DNA, enhancing sensitivity and simplifying the detection process. The combination of rGO with a sequence-specific DNA probe creates a highly sensitive and selective platform for E. coli DNA, distinguishing it from traditional sensors that often depend on more complex and expensive techniques.

However, the long-term stability of the rGO-probe conjugate may be compromised by environmental factors such as temperature fluctuations, pH variations, and changes in ionic strength. To overcome these challenges, future research should focus on optimizing both the sensing material and probe design to enhance the biosensor’s robustness. Moreover, improving sensor performance in complex biological matrices is essential for practical, real-world applications. Potential strategies include incorporating anti-fouling layers or employing dual-probe designs to reduce non-specific interactions. Integration with microfluidic platforms or portable spectrometers could further improve the biosensor’s usability for on-site or point-of-care testing, supporting the development of compact, field-deployable DNA detection systems.

Overall, this rGO-based biosensor demonstrates strong potential for next-generation DNA detection due to its high sensitivity, low cost, and operational simplicity. Nonetheless, further research into its long-term stability, specificity in complex samples, and adaptability to diverse application environments will be essential to advance this technology toward practical, widespread use.

Conclusions

This study successfully developed a rGO-based absorbance DNA biosensor exhibiting high sensitivity and selectivity for detecting E. coli DNA. The rGO was synthesized using Hummers’ method, followed by hydrothermal reduction, and its structure and properties were confirmed by material characterization techniques. Specifically, FTIR analysis revealed the disappearance of oxygen-containing functional groups, indicating the reduction of GO, while XRD patterns showed the expected shift in diffraction peaks consistent with rGO formation. SEM imaging further verified the layered and wrinkled morphology typical of rGO structures. The synthesized rGO was then functionalized with an amino-modified DNA probe to construct the biosensing interface. The resulting biosensor demonstrated a strong correlation between E. coli DNA concentration and absorbance at 273 nm, within a 0–476.19 fM detection range. It achieved a low detection limit of 80.28 fM while exhibiting minimal cross-reactivity with non-target bacterial sequences. The biosensor shows significant potential for applications in healthcare, environmental monitoring, and food safety, where rapid and accurate E. coli detection is critical. However, further research is necessary to enhance long-term operational stability and to enable multiplexed detection of various pathogens. Overall, the results of this study underscore the effectiveness of rGO in biosensor development and highlight its relevance for real-world biosensing applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Braz, V. S., Melchior, K. & Moreira, C. G. Escherichia coli as a multifaceted pathogenic and versatile bacterium. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 548492. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.548492 (2020).

Blount, Z. D. The unexhausted potential of E. coli. elife 4, e05826 (2015).

Schuetz, A. N. in Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology. 187–192 (Elsevier).

Lee, D. S., Lee, S. J. & Choe, H. S. Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infection by Escherichia coli in the Era of Antibiotic Resistance. BioMed Res. Int. 7656752 (2018).

Cody, E. M. & Dixon, B. P. Hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr. Clin. 66, 235–246 (2019).

Baek, S. D., Chun, C. & Hong, K. S. Hemolytic uremic syndrome caused by Escherichia Fergusonii infection. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 38, 253–255 (2019).

Poirel, L. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 6. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec (2018). arba-0026-2017.

Gizaw, Z., Yalew, A. W., Bitew, B. D., Lee, J. & Bisesi, M. Fecal indicator bacteria along multiple environmental exposure pathways (water, food, and soil) and intestinal parasites among children in the rural Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Gastroenterol. 22, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02174-4 (2022).

Khan, F. M. Escherichia coli (E. coli) as an Indicator of Fecal Contamination in Water: A Review. (2020).

McKee, A. M. & Cruz, M. A. Microbial and viral indicators of pathogens and human health risks from recreational exposure to waters impaired by fecal contamination. J. Sustainable Water Built Environ. 7, 03121001 (2021).

Yang, S. C., Lin, C. H., Aljuffali, I. A. & Fang, J. Y. Current pathogenic Escherichia coli foodborne outbreak cases and therapy development. Arch. Microbiol. 199, 811–825 (2017).

Yuan, Y., Zheng, G., Lin, M. & Mustapha, A. Detection of viable Escherichia coli in environmental water using combined Propidium monoazide staining and quantitative PCR. Water Res. 145, 398–407 (2018).

Hariri, S. Detection of Escherichia coli in food samples using culture and polymerase chain reaction methods. Cureus 14 (2022).

Guo, Q. et al. DNA-based hybridization chain reaction and biotin–streptavidin signal amplification for sensitive detection of Escherichia coli O157: H7 through ELISA. Biosens. Bioelectron. 86, 990–995 (2016).

Standley, M., Allen, J., Cervantes, L., Lilly, J. & Camps, M. in Methods in enzymology Vol. 591 159–186Elsevier, (2017).

Pham, T. N. L., Nguyen, S. H. & Tran M. T. A comprehensive review of transduction methods of lectin-based biosensors in biomedical applications. Heliyon (2024).

Nguyen, S. H., Nguyen, V. N. & Tran, M. T. Dual-channel fluorescent sensors based on chitosan-coated Mn-doped ZnS micromaterials to detect ampicillin. Sci. Rep. 14, 10066. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59772-3 (2024).

Nguyen, S. H., Vu, P. K. T. & Tran, M. T. Glucose sensors based on Chitosan capped Zns doped Mn nanomaterials. IEEE Sens. Lett. 7, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/LSENS.2023.3240240 (2023).

Naresh, V. & Lee, N. A. Review on biosensors and recent development of nanostructured Materials-Enabled biosensors. Sensors 21, 1109 (2021).

Nguyen, S. H., Nguyen, V. N. & Tran, M. T. Ampicillin detection using absorbance biosensors utilizing Mn-doped ZnS capped with Chitosan micromaterials. Heliyon 10 (2024).

Nguyen, S. H., Vu, P. K. T., Nguyen, H. M. & Tran, M. T. Optical glucose sensors based on Chitosan-Capped ZnS-Doped Mn nanomaterials. Sensors 23, 2841. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23052841 (2023).

Nguyen, S. H., Vu, P. K. T. & Tran, M. T. Absorbance biosensors-based hybrid MoS 2 nanosheets for Escherichia coli detection. Sci. Rep. 13, 10235 (2023).

Nguyen, S. H. & Tran, M. T. Enzyme-free biosensor utilizing chitosan-capped ZnS doped by Mn nanomaterials for Tetracycline hydrochloride detection. Heliyon 10, e40340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e40340 (2024).

Lu, C., Huang, P., Liu, B., Ying, Y. & Liu, J. Comparison of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide for DNA adsorption and sensing. Langmuir: ACS J. Surf. Colloids. 32 41, 10776–10783. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b03032 (2016).

Wang, Y. Q., Hsine, Z., Sauriat-Dorizon, H., Mlika, R. & Korri-Youssoufi, H. Structural and electrochemical studies of functionalization of reduced graphene oxide with alkoxyphenylporphyrin mono- and tetra- carboxylic acid: application to DNA sensors. Electrochim. Acta. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2020.136852 (2020).

Wu, X., Mu, F., Wang, Y. & Zhao, H. Graphene and Graphene-Based nanomaterials for DNA detection: A review. Molecules: J. Synth. Chem. Nat. Prod. Chem. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23082050 (2018).

Umar, M. F. & Nasar, A. Reduced graphene oxide/polypyrrole/nitrate reductase deposited glassy carbon electrode (GCE/RGO/PPy/NR): biosensor for the detection of nitrate in wastewater. Appl. Water Sci. 8, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-018-0860-1 (2018).

Popov, A. et al. Reduced graphene oxide and polyaniline nanofibers nanocomposite for the development of an amperometric glucose biosensor. Sens. (Basel Switzerland). 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/s21030948 (2021).

Munief, W. M. et al. Reduced graphene oxide biosensor platform for the detection of NT-proBNP biomarker in its clinical range. Biosens. Bioelectron. 126, 136–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2018.09.102 (2019).

Guo, Y. et al. Fabrication of Ag-Cu2O/Reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites as Surface-Enhanced Raman scattering substrates for in situ monitoring of Peroxidase-Like catalytic reaction and biosensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9 22, 19074–19081. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b02149 (2017).

Kong, F. et al. Au-Hg/rGO with enhanced peroxidase-like activity for sensitive colorimetric determination of H2O2. Analyst https://doi.org/10.1039/d0an00235f (2020).

Bhaiyya, M., Gangrade, S., Pattnaik, P. & Goel, S. Laser ablated reduced graphene oxide on paper to realize single electrode electrochemiluminescence standalone miniplatform integrated with a smartphone. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2022.3179008 (2022).

Yu, H. et al. Reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite based electrochemical biosensors for monitoring foodborne pathogenic bacteria: A review. Food Control. 127, 108117. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODCONT.2021.108117 (2021).

Kumar, R. S. et al. Fe3O4 nanorods decorated on polypyrrole/reduced graphene oxide for electrochemical detection of dopamine and photocatalytic degradation of acetaminophen. Appl. Surf. Sci. 556, 149765. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APSUSC.2021.149765 (2021).

Chen, Z. Z. et al. Indirect Immunofluorescence detection of E. coli O157: H7 with fluorescent silica nanoparticles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 66, 95–102 (2015).

Ananda, P. K. P., Tillekaratne, A., Hettiarachchi, C. & Lalichchandran, N. Sensitive detection of E. coli using bioconjugated fluorescent silica nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 6, 100159 (2021).

Wang, D., Chen, J. & Nugen, S. R. Electrochemical detection of Escherichia coli from aqueous samples using engineered phages. Anal. Chem. 89, 1650–1657 (2017).

Xu, M., Wang, R. & Li, Y. Electrochemical biosensors for rapid detection of Escherichia coli O157: H7. Talanta 162, 511–522 (2017).

Razmi, N., Hasanzadeh, M., Willander, M. & Nur, O. Recent progress on the electrochemical biosensing of Escherichia coli O157: H7: material and methods overview. Biosensors 10, 54 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. A sensitive electrochemical strategy via multiple amplification reactions for the detection of E. coli O157: H7. Biosens. Bioelectron. 147, 111752 (2020).

Zheng, L. et al. A microfluidic colorimetric biosensor for rapid detection of Escherichia coli O157: H7 using gold nanoparticle aggregation and smart phone imaging. Biosens. Bioelectron. 124, 143–149 (2019).

Zhu, L. et al. Colorimetric detection and typing of E. coli lipopolysaccharides based on a dual aptamer-functionalized gold nanoparticle probe. Microchim. Acta. 186, 1–6 (2019).

Suaifan, G. A., Alhogail, S. & Zourob, M. Based magnetic nanoparticle-peptide probe for rapid and quantitative colorimetric detection of Escherichia coli O157: H7. Biosens. Bioelectron. 92, 702–708 (2017).

Xu, P. et al. Whole-genome detection using multivalent DNA-coated colloids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 120, e2305995120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2305995120 (2023).

Curk, T. et al. Computational design of probes to detect bacterial genomes by multivalent binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 8719–8726. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1918274117 (2020).

Behzadi, P., Najafi, A., Behzadi, E. & Ranjbar, R. Microarray long oligo probe designing for Escherichia coli: an in-silico DNA marker extraction. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 69, 105–111. https://doi.org/10.5173/ceju.2016.654 (2016).

Garcia, A. et al. Quantification of human enteric viruses as alternative indicators of fecal pollution to evaluate wastewater treatment processes. PeerJ 10, e12957 (2022).

Lan, N. T. et al. Photochemical decoration of silver nanoparticles on graphene oxide nanosheets and their optical characterization. J. Alloys Compd. 615, 843–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.07.042 (2014).

Huang, H. H., De Silva, K. K. H., Kumara, G. R. A. & Yoshimura, M. Structural evolution of hydrothermally derived reduced graphene oxide. Sci. Rep. 8, 6849. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25194-1 (2018).

Tegou, E., Pseiropoulos, G., Filippidou, M. K. & Chatzandroulis, S. Low-temperature thermal reduction of graphene oxide films in ambient atmosphere: Infra-red spectroscopic studies and gas sensing applications. Microelectron. Eng. 159, 146–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mee.2016.03.030 (2016).

Dilworth, J. G. H. A. M. J (Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, 2016).

Xavier, J. R. & Vinodhini, S. Fabrication of reduced graphene oxide encapsulated MnO2/MnS2 nanocomposite for high performance electrochemical devices. J. Porous Mater. 30, 1897–1910 (2023).

Alam, S. N., Sharma, N. & Kumar, L. Synthesis of graphene oxide (GO) by modified hummers method and its thermal reduction to obtain reduced graphene oxide (rGO). Graphene 6, 1. https://doi.org/10.4236/graphene.2017.61001 (2017).

Uhrovčík, J. Strategy for determination of LOD and LOQ values – Some basic aspects. Talanta 119, 178–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2013.10.061 (2014).

Penkova, N. A., Sharapov, M. G. & Penkov, N. V. Hydration shells of DNA from the point of view of Terahertz Time-Domain spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11089 (2021).

Rasheed, P. A. & Sandhyarani, N. Electrochemical DNA sensors based on the use of gold nanoparticles: a review on recent developments. Microchim. Acta. 184, 981–1000 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Rapid label-free identification of mixed bacterial infections by surface plasmon resonance. J. Translational Med. 9, 1–9 (2011).

Ozkan-Ariksoysal, D. et al. DNA-wrapped multi-walled carbon nanotube modified electrochemical biosensor for the detection of Escherichia coli from real samples. Talanta 166, 27–35 (2017).

Paulose, A. K. et al. Rapid Escherichia coli cloned DNA detection in serum using an electrical double layer-gated field-effect transistor-based DNA sensor. Anal. Chem. 95, 6871–6878 (2023).

Nadzirah, S. et al. Titanium dioxide–mediated resistive nanobiosensor for E. coli O157: H7. Microchim. Acta. 187, 1–9 (2020).

Chalka, V. K., Maheshwari, K., Chhabra, M., Rangra, K. & Dhanekar, S. Graphene oxide modified screen printed electrodes based sensor for rapid detection of E. coli in potable water. Microchem. J. 207, 112041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2024.112041 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Hang Dam of Hanoi University of Science and Technology for her generosity in providing bacterial species. We also thank Mr. Hoang Mai Duy and Miss Nguyen Anh Phuong of the College of Health Science at VinUniversity, for their support in this work. This work was funded by VinUni-Illinois Smart Health Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T.T. conceptualized the method and conceived the experiments, C.N.M.H conducted the experiments, C.N.M.H, S.H.N., and M.T.T analyzed the results and prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoang, C.N.M., Nguyen, S.H. & Tran, M.T. Reduced graphene oxide-based absorbance biosensors for detecting Escherichia coli DNA. Sci Rep 15, 29548 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14189-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14189-4