Abstract

This study presents an eco-friendly strategy to enhance the optical and structural properties of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) films through doping with eggplant peel dye (EPPD), a natural pigment extracted from agricultural waste via a green aqueous synthesis (~ 33% yield from 30 g of peel). EPPD was uniformly dispersed in PVA films (PVA-D1, PVA-D2, PVA-D3) using an ultrasonic-assisted solution casting technique, with chitosan (CS) added to prevent fungal growth. Comprehensive characterization (Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)) confirmed successful integration of EPPD, revealing its polyhydric alcohol content, amorphous nature, and uniform distribution within the polymer matrix. Doping with EPPD significantly reduced the optical band gap from 6.314 eV (pure PVA) to 1.8 eV (PVA-D3), introducing localized states that enhanced light absorption (peaking at 554 nm in PVA-D3), as supported by Tauc’s model (transition type: direct allowed → direct forbidden) and dielectric loss analysis. Additionally, the refractive index increased from 1.165 to 1.27, while the optical dielectric constant (ε₁) improved from 1.366 to 1.609 due to enhanced charge carrier density. XRD analysis revealed a decrease in crystallinity from 30.50% (pure PVA) to 18.11% (PVA-D3), leading to a reduction in the glass transition temperature (from 30.5 °C to 25 °C) and melting temperature (from 240 °C to 194 °C). The Urbach energy (Eu), an indicator of structural disorder, increased from 0.43 eV (pure PVA) to 0.62 eV (PVA-D3), reflecting a higher density of localized states in the amorphous matrix and broader tail states in the band structure. These tunable optoelectronic properties position EPPD-doped PVA films as promising candidates for various applications, including UV-protective textiles, smart packaging, biomedical dressings, and energy-efficient optoelectronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing global emphasis on sustainable development has intensified the demand for environmentally friendly materials in optoelectronic technologies. In this context, biodegradable polymers with tunable optical and structural properties are gaining considerable attention due to their low environmental impact and versatility in applications ranging from flexible electronics to biomedical devices. Among these, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) has emerged as a leading candidate owing to its excellent film-forming ability, biodegradability, biocompatibility, chemical stability, and mechanical flexibility, making it suitable for diverse applications in UV-shielding films, smart packaging, flexible sensors, and wound dressings1,2. However, a key limitation of pristine PVA lies in its wide optical band gap (~ 6.0 eV), which significantly restricts its light-harvesting efficiency and charge transport capability, especially in applications requiring strong absorption in the visible or near-infrared regions3,4,5.

Furthermore, its limited inherent antimicrobial activity poses challenges for its use in biomedical and food-contact materials, where microbial resistance is crucial.

To address these challenges, various doping strategies have been employed to tailor the electronic and functional properties of PVA films6. Conventional methods involve the incorporation of metal oxides (e.g., TiO₂, ZnO), quantum dots, or synthetic conductive fillers to enhance optical behavior and mechanical strength7,8,9. While effective, these approaches are often associated with significant drawbacks, including toxicity concerns for biomedical and food-contact applications, high production costs and energy-intensive synthesis, limited biodegradability, and the potential for cytotoxic effects arising from metal ion leaching10,11.

As a result, natural and renewable alternatives are increasingly being explored as eco-safe modifiers. Among them, plant-based dyes derived from agro-waste present a promising, sustainable solution. These pigments often feature π-conjugated systems that provide strong light absorption and can effectively modulate the host polymer’s band structure12,13. Despite the annual global generation of over 1.2 million tons of eggplant (Solanum melongena) particularly peels14,15, their valorization for advanced material development remains underutilized. Eggplant peel is rich in anthocyanins, notably nasunin, delphinidin-3-rutinoside, and cyanidin-3-glucoside16,17,18 which possess acylated, water-soluble structures with strong antioxidant activity, natural chromophore systems, and chemical stability19,20,21. These molecules make eggplant peel-derived dye (EPPD) a compelling candidate for eco-friendly optical doping. However, their use in tuning the band gap and structural modification in polymer matrices like PVA remains largely unexplored. In parallel, chitosan, a natural polysaccharide derived from chitin, offers excellent antibacterial activity, film-forming properties, and biocompatibility, making it suitable for enhancing the microbial resistance of bio-based films. The integration of such multifunctional bio-additives enables the development of advanced materials that meet both optical and hygienic requirements22,23.

In this work, we introduce an environmentally benign, scalable approach for tailoring the optical and structural properties of PVA films via doping with eggplant peel-derived dye (EPPD), extracted through a green aqueous process, and reinforced with chitosan as a natural antibacterial agent. The films were fabricated using an ultrasonic-assisted solution casting method, which ensured homogeneous dispersion of EPPD and minimized dye aggregation. Comprehensive characterization using FTIR, UV-Vis spectroscopy, XRD, and FESEM confirmed the successful incorporation of EPPD into the PVA matrix and revealed substantial modifications in the polymer’s physicochemical properties. The optical band gap of the doped films was significantly reduced from 6.314 eV to 1.8 eV, accompanied by enhanced light absorption, an increased refractive index, and a bathochromic shift extending into the near-infrared region. Structural analysis showed a reduction in both crystallinity and thermal transition temperatures, which are attributed to disrupted polymer chain ordering and weakened hydrogen bonding interactions between PVA chains, induced by the incorporation of EPPD. This study presents a scalable and sustainable approach for fabricating biodegradable, optically active, and antimicrobial PVA-based films by valorizing agricultural waste as a functional dopant source. The films, composed of PVA, chitosan, and anthocyanin-rich extracts, are biocompatible and non-toxic, with demonstrated potential in wound healing, drug delivery, packaging, and energy-efficient optoelectronics. Their multifunctionality supports broader efforts in green and circular material design.

Experimental section

Materials

The EPPD was obtained from eggplant peels sourced from the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. PVA (MW = 89,000–98,000) and CS of high molecular weight were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Distilled water (D.W.) was utilized as the solvent for dissolving and extracting the EPPD dye. All chemicals were used without further purification. In addition to the primary reagents, the following materials were also used in this study: analytical-grade potassium bromide (KBr) for FTIR pellet preparation, Whatman® 90 mm filter paper for Buchner filtration during dye purification, and high-purity gold used as a sputtering target to coat non-conductive samples prior to FESEM imaging.

Instrumentals

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra data was collected via a Perkin-Elmer spectrophotometer (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) in the range of 4000–400 cm⁻¹ using the KBr pellet method, with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ and 8 scans per sample. Ultraviolet-visible (UV–Vis) absorption measurements were carried out using a Cary 60 Spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, USA). X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were conducted on a Panalytical Empyrean X-ray diffractometer and carried out over a 2θ range of 10°–80° at a scanning speed of 10°/min. Thermal analysis was recorded using a Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC131 EVO, France) under an air environment, with samples heated from 20 to 600 °C at a rate of 20 °C min⁻¹. Morphological characterization was performed using Hitachi SU8010 field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) operating at 3 kV accelerating voltages and point resolution of 50 nm. Non-conductive samples were sputter-coated with gold using a Hitachi MC1000 to enhance conductivity for FESEM imaging.

Extraction of EPPD

The extraction of EPPD was carried out using a water-based, ultrasound-assisted method involving sonication, filtration, centrifugation, and rotary evaporation. This green approach is consistent with established methods for extracting anthocyanins from eggplant peel, as reported by Fu et al. (2021), who demonstrated that ultrasound-assisted extraction significantly improves yield and efficiency by accelerating cell wall disruption and facilitating dye release24. Our procedure was carried out as follows: 30 g of dried eggplant peel was ground using an electrical blender and then mixed with 1 L of D.W. The mixture was subjected to sonication twice (10 min each) to enhance solubility and facilitate dye extraction. The solution was first passed through a fine mesh filter to eliminate larger impurities and subsequently subjected to centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 10 min, performed twice, to remove residual coarse particulates. The supernatant was further purified using Buchner filtration with 90 mm filter paper to obtain a clear solution. The solvent was evaporated by rotary evaporation under reduced pressure, and the extracted dye was dried in an oven at 40 °C. From the initial 30 g of eggplant peel, approximately 10 g of EPPD was obtained (≈ 33.3% yield). The extracted EPPD was characterized and stored at room temperature for subsequent use, as illustrated in Scheme 1a.

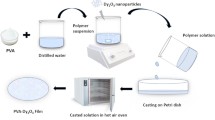

Synthesis of EPPD-doped PVA films

EPPD-doped polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) composite films were synthesized via an ultrasonic-assisted solution casting technique, adapted from established protocols for dye- and nanomaterial-doped polymer systems, as demonstrated by Mohammed et al. (2024)25. To investigate the effect of EPPD concentration on the physicochemical characteristics of the films, five distinct films were prepared, as illustrated in Scheme 1b. They include (1) 1 g pure PVA, (2) 1 g PVA + 0.2 g CS, (3) 1 g PVA + 0.2 g CS + 0.2 g EPPD, (4) 1 g PVA + 0.2 g CS + 0.4 g EPPD, and (5) 1 g PVA + 0.2 g CS + 0.6 g EPPD. Each solution was adjusted to a final volume of 70 mL with distilled water (D.W.). Ultrasonic-assisted solution casting ensured a uniform distribution of EPPD throughout the PVA matrix, reducing aggregation issues commonly observed in natural dye-doped polymer systems3,21.

To prepare the PVA solution, 1 g of PVA was dissolved in 40 mL of D.W. under ultrasonic irradiation at 40 °C for 30 min, until a clear solution was obtained. Separately, three concentrations of EPPD (0.2 g, 0.4 g, and 0.6 g) were each dissolved in 30 mL of D.W. and sonicated at 40 °C for 10 min to achieve homogeneous solutions. For each film formulation, the respective dye solution (5 mL for 0.2 g, 10 mL for 0.4 g, and 15 mL for 0.6 g) was added to a mixture containing 1 g of PVA (40 mL) and 0.2 g of CS, which acted as an antibacterial agent to prevent fungal growth26. The mixtures were stirred thoroughly using a magnetic stirrer at room temperature for 10 min to ensure homogeneity. The resulting homogeneous solutions were then poured into glass Petri dishes and dried at ambient conditions for 72 h, forming uniform films.

The prepared films were labeled as follows: pure PVA (without CS or EPPD), PVA-C (PVA with CS only), and PVA-D1, PVA-D2, and PVA-D3 (PVA with CS and 0.2 g, 0.4 g, and 0.6 g of EPPD, respectively). Representative photographs of these films, illustrating variations in EPPD concentration, are presented in Scheme 1c.

Results and discussion

FT-IR analysis

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to investigate the structural characteristics and functional group interactions present in pure PVA, CS, EPPD, and the EPPD-doped PVA composite films. The spectra provide insight into hydrogen bonding, molecular interactions, and the effect of EPPD incorporation on the polymer matrix (Fig. 1(a-g)).

The FTIR spectrum of pure PVA (Fig. 1a) reveals a broad absorption band around 3290 cm⁻¹, attributed to O–H stretching vibrations associated with strong intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonding27,28. This region is sensitive to external doping and structural rearrangements. Peaks at 2936 cm⁻¹ and 2929 cm⁻¹ correspond to the asymmetric and symmetric CH₂ stretching vibrations, respectively29. An absorption band at 1666 cm⁻¹ is assigned to residual C = C or absorbed water30. The CH₂ bending vibration appears at 1431 cm⁻¹, while the peak at 1335 cm⁻¹ is attributed to OH rocking coupled with CH wagging modes31,32. A prominent spectrum at 1091 cm⁻¹ assigned to the C–O stretching vibration combined with OH bending, reflecting the amorphous sequence of PVA33,34. Additional peaks at 915 cm⁻¹ and 885 cm⁻¹ are corresponding to CH₂ rocking and C–C stretching vibrations, respectively35. A minor peak at 1715 cm⁻¹, arising from C = O stretching, indicates the presence of residual acetate groups from incomplete hydrolysis6,36,37and the peak at 1565 cm⁻¹ is assigned to the bending vibration of adsorbed water molecules35,38,39.

The FTIR spectrum of chitosan (Fig. 1b) displays a broad band at 3420 cm⁻¹, corresponding to overlapping O–H and N–H stretching vibrations40,41. Peaks at 2925 cm⁻¹ and 2877 cm⁻¹ are assigned to the C-H stretching of CH₂ groups42. A sharp band at 1660 cm⁻¹ is related to C = O stretching of amide I groups, while the peak at 1590 cm⁻¹is attributed to N–H bending of amide II and C–N stretching43. Additional bands at 1427, 1380, and 1320 cm⁻¹ are assigned to CH₂ bending modes, and the peaks at 1161 cm⁻¹ and 1080 cm⁻¹ arise from C–O–C stretching vibrations in glycosidic linkages44.

The FTIR spectrum of EPPD extract (Fig. 1c) confirms the presence of anthocyanin compounds, with spectral features consistent with nasunin, the major anthocyanin component of eggplant peel. Ghosh et al. (2022) highlighted anthocyanins as essential water-soluble pigments in plant coloration and biochemical processes45. Subsequent studies by Florio et al. (2021) and Noda et al. (2000) identified nasunin as a predominant anthocyanin in eggplant peel, characterized by strong antioxidant activity46,47. Ichiyanagi et al. (2005) further demonstrated that nasunin exists as a mixture of cis-trans isomers of delphinidin derivatives, enhancing its stability and bioavailability48. Alighadri et al. (2024) emphasized the potential of eggplant peel as a sustainable and underutilized source of nasunin49. The broad absorption peak at 3428 cm⁻¹ is associated with the O–H stretching vibrations of phenolic groups50. Distinct peaks observed at 2932 cm⁻¹ and 2853 cm⁻¹ are assigned to asymmetric and symmetric C–H stretching vibrations of methyl (CH₃) and methylene (CH₂) groups, respectively51.The absorption at 1615 cm⁻¹ corresponds to C = O stretching vibrations, indicative of tautomeric anthocyanin forms52,53,54,55. Additional absorption peaks at 1416 cm⁻¹ and 1266 cm⁻¹ are attributed to aromatic ring stretching and = C–O–C linkages56,57. Meanwhile, the peak at 1070 cm⁻¹ is assigned to C–O–C bending vibrations51. These functional groups play a central role in hydrogen bonding and are responsible for the observed changes in optical and structural behavior when doping into the polymer matrix.

Figure 1(d–g) shows the FTIR spectra of the composite films (PVA-C, PVA-D1, PVA-D2, and PVA-D3). The spectrum of PVA-C (Fig. 1d) indicates that the incorporation of chitosan, intended primarily to impart antimicrobial properties52,58induces minimal changes in the PVA matrix. A slight shift in the O–H/N–H stretching region from 3130 to 3530 cm⁻¹ to 3110–3530 cm⁻¹ suggests limited hydrogen bonding interactions between chitosan and PVA59,60. The C = O stretching band of non-hydrolyzed vinyl acetate units appears at 1707 cm⁻¹, consistent with the previous report61.

Doping with EPPD resulted in minor spectral changes being observed. In PVA-D1 (Fig. 1e), slight O–H/N–H region shifts indicated initial interactions between PVA and EPPD62. As the dye content increased (PVA-D2, Fig. 1f), the O–H/N–H stretching region shifted to 3088–3530 cm⁻¹, and the C = O stretching band broadened and shifted to 1628 cm⁻¹62,63. The N–H/O–H bending peak at 1558 cm⁻¹ disappeared due to overlap with the C = O stretching band of EPPD, reflecting molecular integration at the polymer interfacee62,63. At the highest dye loading (PVA-D3, Fig. 1g), further shifts were observed: the O–H/N–H stretching band shifted to 3043–3530 cm⁻¹, and the C = O stretching peak moved to 1625 cm⁻¹, with complete disappearance of the N–H/O–H bending band. Peaks at 1417 cm⁻¹ (C–H bending), 1308 cm⁻¹ (C–N bending), and 1085 cm⁻¹ (C–O–C stretching) became more prominent, indicating stronger interactions and increased spectral overlap at higher dye64,65. These systematic spectral changes directly correlate with dye loading and confirm that EPPD interacts robustly with the polymer chains via hydrogen bonding and dipolar interactions66,67,68,69. Thus, FT-IR analysis not only confirms successful incorporation of EPPD into the PVA matrix but also elucidates the strength and nature of intermolecular interactions responsible for the modified optoelectronic behavior70.

Scheme 2 illustrates the proposed mechanism of hydrogen bond interactions between PVA–chitosan matrices and EPPD molecules71,72. The hydroxyl (–OH) and amine (–NH₂) functional groups of PVA and chitosan serve as active sites for hydrogen bonding with the oxygen-containing moieties of EPPD, primarily derived from nasunin73. Additionally, residual acetate groups from partially hydrolyzed PVA contribute to the interaction network by forming further hydrogen bonds. This hydrogen bonding mechanism is validated by FTIR spectroscopy in analogous doped polymer systems (Aziz et al., 2025)44,(Sreeja et al., 2013)74and (Rao et al., 2023)75. Thereby enhancing the stability of EPPD within the polymer matrix76. This interaction mechanism facilitates the formation of robust EPPD-doped PVA films, leading to improved dye retention and structural stability. Moreover, strong hydrogen bonding promotes enhanced charge carrier mobility and broadens photon absorption across the UV to near-infrared regions, resulting in a significant reduction in the optical bandgap77.

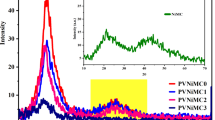

XRD analysis

The crystalline structure of the materials was examined using X-ray diffraction (XRD), and the data were processed using OriginPro 2024. Peak deconvolution was applied to quantify the areas corresponding to the crystalline (AC) and amorphous (AA) peaks, the crystallinity index (χc) was then calculated using Eq. (1)78:

where AT = AC+AA represents the total area under both crystalline and amorphous regions. The χc values for all samples, derived from the AC and AT measurements78,79are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2a shows the XRD pattern of EPPD dye, which displays a broad hump centered around 2θ = 20°, indicating a predominantly amorphous nature, agreeing with the result reported by Al-Muntaser et al. (2025)80.The low intensity and the lack of sharp, well-defined peaks further confirm the amorphous characteristics of the dye, where the atoms or molecules are arranged in a disordered manner without a repeating crystalline lattice81,82. The dye’s degree of crystallinity is 8.64, as reported, indicating that only a small fraction of the material adopts an ordered, crystalline structure. Such low crystallinity is typical of organic dyes, which often exhibit limited long-range molecular order due to their complex molecular structures and weak intermolecular interactions5,83.

(Fig. 2b) presents the XRD pattern of the pure PVA film, revealing two characteristic peaks at 2θ = 19.59° and 40.64°, indicative of the semi-crystalline nature of the PVA membrane (a crystallinity of ~ 20% is plausible and commonly reported in literature for films cast from aqueous solutions)4,70,84. The semi-crystallinity of PVA arises from intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonding, which may take place within an individual monomer unit or between different monomer units85.

When CS was incorporated (Fig. 2c), a slight shift in crystalline index from 30.50 to 26.15 was observed, suggesting a minor increase in amorphous character. This shift is consistent with FTIR data, which showed only subtle changes in the O–H and N–H stretching regions, confirming that chitosan interacts weakly with the PVA matrix61,86. Therefore, chitosan primarily acts as an antibacterial agent with negligible influence on the polymer’s structural organization87,88.

Figures 2(d–f) show the XRD patterns of the dye-doped films (PVA-D1, PVA-D2, and PVA-D3), resulting in a decrease in the intensity of the peaks. The reduction in intensity is indicative of a decline in the localized charge density, which is a key factor in the electronic and optical properties of the material, as demonstrated in the work of Sudhakaran et al. (2024)89. Revealing a concentration-dependent reduction in crystallinity. As EPPD content increases, the diffraction peaks broaden and decrease in intensity, indicating increased structural disorder. The corresponding crystallinity values (χc) decrease progressively from 23.1% for PVA-D1 to 21.91% for PVA-D2 and 18.11% for PVA-D3, as shown in Table 1. This phenomenon is attributed to the disruption of the polymer chain packing by the amorphous dye molecules, which interfere with the formation of ordered crystalline domains86,90,91. To further support the reduction in crystallinity, deconvolution of the XRD patterns was carried out as shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Each profile was fitted using multiple Gaussian functions to resolve overlapping components. The sharp peak centered around 2θ ≈ 19.5° was attributed to the crystalline regions of polyvinyl alcohol, reflecting ordered chain packing and intermolecular hydrogen bonding. In contrast, the broad underlying halo spanning approximately 2θ ≈ 25°–35° was assigned to the amorphous phase, corresponding to disordered regions in the polymer matrix. As dye concentration increased, the intensity and sharpness of the crystalline peak decreased while the amorphous contribution became more prominent. This trend confirms the progressive disruption of the semi-crystalline structure due to EPPD incorporation and aligns with the previously reported crystallinity index values92.

These findings demonstrate the adjustable crystallinity of doped PVA films through compositional control by simply varying the concentration of EPPD, which enables precise tuning of the film’s crystalline structure: as EPPD loading increases from 0 g (pure PVA) to 0.6 g (PVA-D3), the crystallinity index (χc) decreases from 30.5 to 18.11%. This reduction is attributed to the amorphous nature of EPPD molecules, which interfere with polymer chain packing and disrupt hydrogen-bonded crystalline domains93. Such tunability is a critical feature for tailoring mechanical and optical performance in practical applications including smart packaging, biomedical coatings, sensors, solar filters, and UV-protective materials94. Reduced crystallinity enhances UV-shielding efficiency by improving dye dispersion and promoting stronger interactions between UV light and functional groups within the amorphous regions. Moreover, disordered matrices exhibit broader absorption edges (Urbach tails) as shown in Fig. 5d, extending optical absorption deeper into the UV–visible range. This structure-property relationship is supported by Zhou et al. (2022), who demonstrated that reducing crystallinity in lignin-based PVA films significantly improved their UV-blocking performance95.

Morphological studies

FESEM was conducted to examine the surface morphology and compatibility of pure PVA and composite films96,97,98. Figure 3(a–e) presents the FESEM micrographs of the films, illustrating notable morphological differences resulting from the addition of EPPD.

The surface of the pure PVA film (Fig. 3a) appears relatively smooth and featureless, indicative of its homogeneous and amorphous nature99,100. In contrast, the PVA-C film (Fig. 3b) exhibits a slightly roughened texture due to the incorporation of chitosan101,102,103which introduces minor surface heterogeneities. Upon doping with EPPD, distinct changes in surface topography are observed. FESEM images of PVA-D1, PVA-D2, and PVA-D3 (Figs. 3(c–e)) reveal progressively increasing surface roughness and the appearance of discrete EPPD particles embedded within the polymer matrix104. White granules and granular aggregates were observed randomly distributed on the sample surfaces. The FESEM pictures of the filled polymer samples indicated an increase in porosity following the incorporation of EPPD105. At higher dye concentrations (PVA-D2 and PVA-D3), larger aggregates and more prominent particle clustering are evident, suggesting increased filler loading and possible agglomeration of EPPD within the matrix101. These morphological changes correspond with FTIR findings that confirmed the presence of hydroxyl (–OH) and carbonyl (–C = O) functional groups on the EPPD surface46,47,50. These groups are capable of forming hydrogen bonds with PVA chains, enhancing interfacial adhesion and promoting dye dispersion at lower concentrations101,106,107. However, at elevated loading levels, the likelihood of particle agglomeration increases, potentially leading to localized inhomogeneities108.

The observed increase in surface roughness with higher EPPD content indicates underlying structural modifications that can affect the films’ optical, dielectric, and mechanical performance109. Similar morphology-related trends have been reported in other biopolymer-based composite systems, disrupted polymer packing, and enhanced amorphous behavior (Hanash et al., 2025)105. These structural disruptions are in line with the reduced crystallinity observed in the XRD analysis and the bathochromic shifts in UV-Vis absorption spectra. Such modifications are consistent with the decreased crystallinity observed in XRD analysis and the bathochromic shifts in optical absorption spectra. Overall, the FESEM results confirm the successful incorporation of EPPD into the PVA matrix and highlight the influence of dye concentration on surface morphology and microstructure.

Optical properties

The optical characteristics of polymeric materials an essential role in determining their suitability for optoelectronic and photonic applications110,111. To assess the effect of EPPD dye doping on the optical behavior of PVA films, UV–Vis spectroscopy was employed. Key parameters evaluated include the absorption characteristics, absorption edge, refractive index, optical dielectric constant, and optical band gap.

Investigation of absorption characteristics

The UV–Vis absorption spectra of pure PVA, PVA-C, and EPPD-doped PVA films (PVA-D1, PVA-D2, PVA-D3) are shown in Fig. 4. Pure PVA and PVA-C display absorption bands around 189–200 nm, attributed to π–π* transitions112 and at 275–283 nm, ascribed to n–π* transitions113. The latter are likely due to residual carbonyl (C = O) groups in partially hydrolyzed polyvinyl acetate segments and from chitosan113,114. These results indicate minimal optical changes due to chitosan addition.

With increasing EPPD content, a noticeable bathochromic (red) shift occurs in the absorption edge, indicating enhanced π-conjugation and electronic interaction between the dye and the PVA matrix115. The most prominent effect is observed in the PVA-D3 film, which shows a strong absorption peak at 554 nm. This extended absorption into the visible region signifies the formation of new localized states within the band structure, likely due to aromatic and phenolic compounds present in EPPD116,117.

The bathochromic shift confirms successful electronic integration of the EPPD within the PVA matrix, enhancing light absorption across a broader spectral range. This improvement is essential for potential optoelectronic applications such as UV-blocking coatings, photodetectors, and optical data storage. Additionally, since EPPD is derived from a biodegradable, non-toxic source, the resulting films are both eco-friendly and potentially biocompatible118. However, future studies are required to assess long-term optical stability and cytotoxicity for biomedical or packaging applications.

Absorption edge

The absorption edge is a critical parameter in evaluating a material’s electronic structure and optical band behavior119. It represents the minimum photon energy necessary to promote electrons from the valence band to the conduction band and is directly associated with the optical band gap. The absorption coefficient (α) was calculated using Eq. (2), derived from the transmittance and reflectance spectra of the films120:

where t, T, and R correspond to the thickness, transmittance, and reflectance of the sample, respectively.

Figure 5a presents the variation of the absorption coefficient on photon energy for pure PVA and EPPD-doped films. Pure PVA exhibits an absorption edge at 6.128 eV, whereas the edge progressively shifts to lower energies with increasing EPPD content, reaching 1.983 eV for PVA-D3. This pronounced red shift (bathochromic shift) indicates a significant reduction in the band gap energy (Eg)121. Similar results were reported by Al-Muntaser et al. (2024)6.

The shift is attributed to the integration of EPPD molecules into the PVA matrix, introducing π-conjugated structures and localized states within the band gap122. These new electronic states facilitate transitions at lower photon energies, thereby modifying the optical absorption profile of the material121. Such behavior is characteristic of doped amorphous polymers, where enhanced disorder and molecular interaction broaden the absorption tail and reduce the effective optical gap123.

These findings confirm that EPPD doping induces meaningful changes in the electronic structure of PVA, supporting its potential use in optoelectronic and light-harvesting applications.

Refractive index and optical dielectric constant studies

The refractive index (n) is a key optical parameter that governs light propagation through materials and is particularly important for applications in photonics, waveguides, and sensors124. In polymeric systems, the refractive index reflects the polarizability and electronic structure of the material, both of which are altered by the presence of dye molecules125,126.

The refractive index of pure PVA and EPPD-doped films was calculated using the extinction coefficient (k) and reflectance (R), based on Eq. (3)127:.

The extinction coefficient was derived from the absorption coefficient ɑ and the wavelength λ, using the expression Eq. (4)128:

Additionally, reflectance (R) can be mathematically derived from absorption (A) and transmittance (T) values using the expression R = 1− (A + T). T values are typically calculated based on Beer’s law as T = 10−A, which relates the attenuation of light to the material’s absorption properties, providing a comprehensive framework for analyzing the optical properties of materials129,130,131.

As shown in Fig. 5b, the refractive index increases with higher EPPD content, rising from 1.169 for pure PVA to 1.270 for PVA-D3. This enhancement is attributed to the introduction of π-conjugated systems and polar functional groups (e.g., –OH, –COOH) in EPPD, which increase the polarizability and electron density of the composite matrix. According to the Lorentz–Lorenz model, this leads to an overall rise in refractive index, consistent with the observed data132. High refractive index materials, like those developed in this study, are essential for advanced optical and optoelectronic applications, such as waveguides, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and antireflective coatings133.

Furthermore, all doped films exhibit significant refractive index dispersion across the visible to near-infrared range, in contrast to the behavior of pure PVA films. This wavelength-dependent behavior underscores their potential for tailored optical applications. A similar dispersion trend has been reported by Allwin Sudhakaran et al. (2024)128 where the refractive index decreased with increasing wavelength and stabilized over a broad spectral range. In such systems, changes in composition were found to alter the electronic structure and crystallinity, leading to an increase in refractive index—consistent with the behavior observed in the EPPD-doped PVA films in this study. The optical dielectric constant (ε₁), which corresponds to the real part of the complex dielectric function, was calculated using Eq. (5)70:

This equation demonstrates that ε₁ depends directly on the refractive index (n) and the extinction coefficient (k)70,134,135.

Figure 5c depicts the variation in ε₁ as a function of wavelength for all samples. A clear trend is observed, with ε₁ increasing from 1.366 (pure PVA) to 1.609 (PVA-D3), indicating a higher density of localized electronic states in the doped films70,136. These states are likely a result of interfacial charge-transfer interactions between the polymer chains and EPPD molecules, as supported by FTIR and XRD results showing structural reorganization and reduced crystallinity70.

The imaginary part of the dielectric function (ε₂), which accounts for absorption losses, was calculated using (ε2 = 2nk), where n denotes the refractive index and k represents the extinction coefficient44.

The combined increase in both ε₁ and ε₂ with dye loading confirms that EPPD incorporation enhances light–matter interactions, increasing both energy storage and dissipation within the films137. This behavior is favorable for optoelectronic devices requiring tunable optical constants. At longer wavelengths, the static dielectric constant (ε₀) correlates inversely with the band gap as described by the Penn model Eq. (6)137:

Here, ωp represents the plasma frequency. Since the refractive index (n) is related to the dielectric constant (ε = n²), the Penn model is effectively expressed in terms of n139.

This relation emphasizes the observed trend: as the optical band gap narrows with increasing EPPD content, the dielectric constant rises accordingly, supporting the potential of these films for electro-optical applications140.

Urbach energy analysis

To investigate the degree of disorder and structural imperfections in polymeric materials, the Urbach energy (Eu) can be evaluated using the absorption coefficient (α) as described by the following exponential relation141:

Eu reflects the width of the exponential tail of localized states within the band gap, often associated with structural disorder. It is generally considered a temperature-independent parameter or only weakly temperature-dependent. The constant α₀ represents the absorption at the interface between the optical medium and incident light142.

Eu can be determined by plotting ln(α) versus photon energy (hν), and the value of Eu is derived by calculating the reciprocal of the slope obtained by fitting the linear segment of the curve143(as shown in Fig. 5d). An inverse relationship typically exists between Urbach energy and the optical band gap144,145. The Eu values obtained for all composite samples are summarized in Table 2. Notably, as the concentration of the EPPD within the PVA matrix increases, Eu also rises. This trend indicates a gradual increase in structural disorder within the polymer composites, suggesting the formation of more pronounced energy tails and a less ordered band structure146. This supports amorphization, π-conjugation, and band gap reduction, consistent with XRD and optical data.

(a) Absorption coefficient vs. photon energy for all films, showing a red shift in the absorption edge with increasing EPPD concentration. (b) Refractive index spectra indicating an enhancement from 1.165 (Pure-PVA) to 1.270 with EPPD doping. (c) Optical dielectric constant (ε₁) increases proportionally with EPPD concentration, highlighting improved polarizability. (d) Urbach energy analysis for all films, reflecting changes in structural disorder with doping.

Band gap study

Further investigation into the UV-Visible spectral response was carried out to assess the potential application of the synthesized samples in optoelectronic and energy storage devices141.The optical band gap (Eg) of PVA and EPPD-doped PVA films was comprehensively investigated using both Tauc’s method and optical dielectric loss spectra. These transitions were analyzed using Tauc’s relation, expressed by the following Eq. (8)147.

where hν is the photon energy, α is the absorption coefficient, A is a constant, and γ is a transition type. The absorption coefficient α was calculated using the following Eq. (9)149:

Tauc plots were generated for different transition types by plotting (αhν)γ versus photon energy (hν). γ depends on the nature of the transition, where γ values of 1/2 and 3/2 correspond to allowed and forbidden direct transitions, respectively, and γ = 2 and 3 represent indirect allowed and forbidden transitions113,148. Figures 6(a-d) illustrate the fitting results, while Table 3 summarizes the extracted band gap values.

Pure PVA exhibited a band gap of approximately 6.314 eV with γ = 1/2, indicating a direct allowed transition, consistent with its semi-crystalline nature149. Similarly, PVA-C displayed a slightly reduced band gap (5.712 eV) with the same transition type, suggesting minimal influence from chitosan on the optical transition mechanism.

In contrast, EPPD-doped samples exhibited significant band gap reduction and a shift in transition type. For PVA-D1, D2, and D3, the band gaps were reduced to 3.24 eV, 2.721 eV, and 2.55 eV, respectively, with the best Tauc fit achieved using γ = 3/2, indicating direct forbidden transitions149. This transition change reflects increased structural disorder and the formation of localized states within the band gap, attributed to the incorporation of EPPD’s conjugated and polar functional groups150.

To validate these results, the imaginary part of the dielectric constant (ε₂), derived from UV-Vis spectra, was analyzed (Fig. 7). Linear regions at higher photon energies were used to estimate Eg values that were consistent with the Tauc method, confirming the reliability of the dual-approach strategy151.

The progressive narrowing of the band gap with increasing dye concentration is attributed to enhanced amorphization, as supported by XRD data152. The disrupted crystallinity suppresses momentum conservation, thereby favoring forbidden transitions153. Figure 8 compares the band gap energies of various previously reported PVA-based films doped with different materials such as Zinc oxide (ZnO)154Silver Nanoparticles (Ag)155Ferric Citrate (Fe Citrate)156Potassium Chromate (K₂CrO₄)157Rhodamine 6G (R6G)158Crystal Violet (CV)29Turmeric dye159and doped with Sodium Nitrate (NaNO₃)160. Among these, the EPPD–PVA film developed in this study shows the lowest band gap (2.55 eV direct and 1.8 eV indirect), indicating enhanced absorption in the visible region.

This demonstrates the effectiveness of EPPD, a natural dye extracted from eggplant peel waste, in significantly reducing the optical band gap of PVA. The results highlight both the optical superiority and sustainability of using EPPD compared to other dopants, including natural dyes like turmeric and synthetic dyes like R6G.

(Supplementary Figure S6) provides a schematic comparison between the direct and indirect transitions observed in the films. These findings highlight the tunability of optical properties in PVA films through natural dye doping and reinforce the value of EPPD as a sustainable modifier for optoelectronic materials.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) was performed to investigate the effect of EPPD incorporation on the thermal transitions of PVA-based films161. This technique provides insight into the glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting temperature (Tm), which reflect changes in polymer chain mobility and crystallinity162. For studying polymeric materials’ thermal characteristics, DSC is an excellent technique. The thermograms of the pure PVA and composite films revealed endothermic transitions corresponding to the glass transition and melting points. For pure PVA, a Tg of 30.5 °C was observed, followed by a distinct melting peak at 240 °C. These values are consistent with literature reports for semi-crystalline PVA materials163. It is important to note that although the Tg of fully dried, highly crystalline PVA is typically reported in the 75–85 °C range, our observed Tg agrees with studies where solution-cast PVA films retain a small amount of bound water. This bound water acts as a plasticizer, enhancing chain mobility and significantly lowering the Tg. For example, Remiš et al. (2021) reported a Tg of ~ 42 °C for PVA films with ~ 5 wt% water content, as verified through DSC and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)163. Additionally, Song et al. (2020) showed that even ~ 1.8 wt% water can reduce the Tg of PVA from ~ 67 °C to ~ 38 °C. These findings support our measured Tg of 30.5 °C and confirm that moisture plays a dominant role in modulating PVA’s thermal behavior164. A broad endothermic event between 60 °C and 170 °C, observed across all samples, is attributed to the evaporation of absorbed water165,166. As EPPD concentration increased, both Tg and Tm progressively decreased. In PVA-C, Tg dropped slightly to 41.5 °C and Tm to 233 °C, suggesting limited interaction between chitosan and PVA. However, the reductions became more significant in the EPPD-doped samples: PVA-D1 (Tg = 40 °C, Tm = 225 °C), PVA-D2 (Tg = 37 °C, Tm = 220 °C), and PVA-D3 (Tg = 25 °C, Tm = 194 °C). These results are illustrated in the DSC thermograms shown in Fig. 9 (a-e).

The progressive decline in both Tg and Tm is attributed to the disruption of PVA’s semi-crystalline structure by EPPD105,167A recent study by Mohammed and El-Sayed (2023) on PVA/polyethylene glycol (PEG) blends demonstrated a notable reduction in the Tg, attributed to the plasticizing effect of the dopant (PEG)168. Singhal et al. (2012) demonstrated that in PVA/indium oxide nanocrystals (In₂O₃) nanocomposites, the Tm decreased systematically with higher In₂O₃ loading (e.g., from 212 °C in pure PVA to 196 °C at 5 wt% In₂O₃), linked to dopant-induced disruption of PVA chain folding and crystal perfection, which lowered overall crystallinity62. XRD data confirm a decrease in crystallinity, correlating with the reduced thermal stability. EPPD molecules, rich in polar and aromatic groups, likely interfere with inter-chain hydrogen bonding and prevent efficient packing of PVA chains169. This leads to a more disordered, amorphous microstructure, allowing greater molecular mobility and reducing the energy required for thermal transitions170.

The decline in Tg suggests enhanced chain flexibility in the doped films, likely due to the plasticizing effect of EPPD and the breakdown of crystalline domains169. The lower Tm values indicate that EPPD not only reduces the size of crystalline regions but may also promote the formation of less perfect or thermally unstable crystals171,This assertion is further supported by the observed decrease in crystallinity (XRD), increased structural disorder (Urbach energy), and morphological irregularities (FESEM), all indicating less perfect crystal formation. These findings collectively confirm that EPPD incorporation disrupts polymer chain packing, reducing thermal stability. The thermal behavior thus reflects the structural reorganization of the polymer matrix induced by dye incorporation. These observations confirm that EPPD doping is an effective strategy for tuning the thermal properties of PVA films, By controlling crystallinity and polymer chain mobility through natural additive incorporation, it is possible to tailor materials for applications that require specific thermal thresholds, such as temperature-sensitive coatings, packaging films, or biomedical substrates171.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that EPPD, an eco-friendly dye derived from agricultural waste, can significantly enhance the structural and optical performance of PVA films. EPPD doping reduced the optical band gap from 6.314 eV to 1.8 eV, expanded light absorption from UV into the near-infrared region, and introduced new electronic states as confirmed by Tauc and dielectric analyses. FTIR, XRD, and FESEM analyses revealed increased amorphous content and disrupted hydrogen bonding networks, correlating with reduced crystallinity (30.50–18.11%). Thermal analysis via DSC confirmed the structural softening effect of EPPD, with Tg decreasing from 30.5 °C to 25 °C and Tm from 240 °C to 194 °C. Additionally, the refractive index and optical dielectric constant increased with higher dye content, highlighting improved polarizability and light-matter interaction. Notably, the Urbach energy Eu increased from 0.43 eV to 0.62 eV, confirming the rise in structural disorder and the broadening of tail states in the band structure—key indicators of amorphous transformation and enhanced optoelectronic tunability. Collectively, these results position EPPD as a sustainable, multifunctional dopant for tailoring PVA films toward advanced green applications. This approach offers a scalable, sustainable pathway for engineering green materials suitable for UV-blocking films, smart packaging, photonic devices, and biomedical applications.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Koosha, M., Mirzadeh, H., Shokrgozar, M. A. & Farokhi, M. Nanoclay-reinforced electrospun chitosan/pva nanocomposite nanofibers for biomedical applications. RSC Adv. 5, 10479–10487 (2015).

Rao, J. P. & Geckeler, K. E. Polymer nanoparticles: Preparation techniques and size-control parameters. Prog Polym. Sci. 36, 887–913 (2011).

Mashayekhi, F. et al. Fused filament fabrication of polymers and continuous fiber-reinforced polymer composites: advances in structure optimization and health monitoring. Polym. (Basel). 13, 789 (2021).

Abdullah, O. G. & Saleem, S. A. Effect of copper sulfide nanoparticles on the optical and electrical behavior of Poly (vinyl alcohol) films. J. Electron. Mater. 45, 5910–5920 (2016).

Gürses, A. et al. Classification of dye and pigments. Dyes Pigm. 126, 31–45 (2016).

Al-Muntaser, A. A. et al. Exploring the influence of Sudan IV Azo dye on the structural, optical, and dispersion characteristics of PVA/Su-IV composites. Phys. Scr. 99, 105991 (2024).

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R. & Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700782 (2017).

Bhujbal, A. V., Gokhale, T. A. & Bhanage, B. M. Reductive amination of biomass-based levulinic acid into pyrrolidone by protic ionic liquid via dehydrogenation of dimethyl amine borane. Waste Biomass Valor. 13, 443–451 (2022).

Arrones, A. et al. Mutations in the SmAPRR2 transcription factor suppressing chlorophyll pigmentation in the eggplant fruit Peel are key drivers of a diversified colour palette. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 1–14 (2022).

Arrones, A. et al. Mutations in the SmAPRR2 transcription factor suppressing chlorophyll pigmentation in the eggplant fruit Peel are key drivers of a diversified colour palette. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 1025951 (2022).

Sarabandi, K., Jafari, S. M., Mahoonak, A. S. & Mohammadi, A. Application of gum Arabic and maltodextrin for encapsulation of eggplant Peel extract as a natural antioxidant and color source. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 140, 59–68 (2019).

Abdeen, Z., Mohammad, S. G. & Mahmoud, M. S. Adsorption of Mn (II) ion on Polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan dry blending from aqueous solution. Environ. Nanatechnol. Monit. Manag. 3, 1–9 (2015).

Philippi, K., Tsamandouras, N., Grigorakis, S. & Makris, D. P. Ultrasound-assisted green extraction of eggplant Peel (Solanum melongena) polyphenols using aqueous mixtures of glycerol and ethanol: optimisation and kinetics. Environ. Process. 3, 369–386 (2016).

Matica, M. A., Aachmann, F. L., Tøndervik, A., Sletta, H. & Ostafe, V. Chitosan as a wound dressing starting material: antimicrobial properties and mode of action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 5889 (2019).

Karimi, A., Kazemi, M., Samani, S. A. & Simal-Gandara, J. Bioactive compounds from by-products of eggplant: functional properties, potential applications and advances in valorization methods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 112, 518–531 (2021).

Mohamed, M. S., Zeitoun, A. A. & Abdalla, A. E. Assessment of Chemical Composition and Bioactive Compounds in the Peel, Pulp and Whole Egyptian Eggplant Flour. J. Adv. Agric. Res. (Fac. Agric. Saba Basha).

Alighadri, T., Tabibiazar, M., Mohammadi, M., Jahanban-Esfahlan, A. & Amarowicz, R. Nasunin, an amazing chemical constituent in eggplants (Solanum melongena L.): A review of its major properties and Health-Promoting effects. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 4, 16–35 (2023).

Condurache, N. N. et al. Eggplant peels as a valuable source of anthocyanins: extraction, thermal stability and biological activities. Plants 10, 577 (2021).

Charlton, N. C., Mastyugin, M., Török, B. & Török, M. Structural features of small molecule antioxidants and strategic modifications to improve potential bioactivity. Molecules 28, 1057 (2023).

Chemat, F. et al. Ultrasound assisted extraction of food and natural products. Mechanisms, techniques, combinations, protocols and applications. A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 34, 540–560 (2017).

Chew, C. L. et al. Improving sustainability of palm oil production by increasing oil extraction rate: A review. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 14, 573–586 (2021).

Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M. P. & Hultink, E. J. The circular Economy–A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 143, 757–768 (2017).

Chittella, H., Yoon, L. W., Ramarad, S. & Lai, Z. W. Rubber waste management: A review on methods, mechanism, and prospects. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 194, 109761 (2021).

Fu, X., Zhu, C., Shen, A., Fan, W. & Shan, C. Extraction of Anthocyanin from Eggplant Peel by Ultrasonic Assisted Method and Application in Cosmetics. E3S Web Conf. 267, (2021).

Mohammed, S. J., Hawaiz, F. E., Aziz, S. B. & Al-Jaf, H. S. Organic soluble nitrogen-doped carbon Dots (ONCDs) to reduce the optical band gap of PVC polymer: breakthrough in polymer composites with improved optical properties. Opt. Mater. 149, 115014 (2024).

Ong, P. J. et al. Valorization of spent coffee grounds: A sustainable resource for Bio-based phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Waste Manag. 157, 339–347 (2023).

Korbag, I. & Mohamed Saleh, S. Studies on the formation of intermolecular interactions and structural characterization of Polyvinyl alcohol/lignin film. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 73, 226–235 (2016).

Tacker, R. C., Rakovan, J., Harlov, D., Hughes, J. M. & Cichy, S. B. The OH-stretching region in infrared spectra of the apatite OH-Cl binary system. Am. Mineral. 109, 2086–2094 (2024).

Al-Muntaser, A. A. et al. Investigation of structural and optical characteristics of pva/crystal Violet dye composites for flexible smart optoelectronic applications. J. Polym. Res. 31, 1–11 (2024).

Kim, W. et al. Simple Preparation of ordered mesoporous carbons assisted by an organosilicate as a linking material. Carbon N Y. 48, 4566–4569 (2010).

Gieroba, B., Kalisz, G., Krysa, M., Khalavka, M. & Przekora, A. Application of vibrational spectroscopic techniques in the study of the natural polysaccharides and their cross-linking process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 2630 (2023).

Bakri, M. K., Bin & Jayamani, E. Comparative study of functional groups in natural fibers: Fourier transform infrared analysis (FTIR). in International Conference on Futuristic Trends in Engineering, Science, Humanities, and Technology (FTESHT-16) 167–174 (2016).

Hossain, U. H., Seidl, T. & Ensinger, W. Combined in situ infrared and mass spectrometric analysis of high-energy heavy ion induced degradation of Polyvinyl polymers. Polym. Chem. 5, 1001–1012 (2014).

Nkhwa, S., Lauriaga, K. F., Kemal, E. & Deb, S. Poly (vinyl alcohol): physical approaches to designing biomaterials for biomedical applications. in Conference Papers in Science vol. 2014 403472Wiley Online Library, (2014).

Jipa, I. M. et al. Potassium sorbate release from poly(vinyl alcohol)-bacterial cellulose films. Chem. Pap. 66, 138–143 (2012).

Alsufyani, S. J. Influence of γ-irradiation on the structural and optical properties of pva/rgo films reinforced with rGO for nuclear shielding applications. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 16, 100663 (2023).

Boroujeni, F. M., Fioravanti, G. & Kander, R. Synthesis and characterization of cellulose microfibril-reinforced Polyvinyl alcohol biodegradable composites. Mater. (Basel). 17, 526 (2024).

Mohammed, M. I., Ismail, A. M., Salem, G. F. & Structural Optical and thermal properties of PVA / KI based solid polymer electrolyte. Egypt. J. Solids. 40, 79–94 (2017).

Kharazmi, A. et al. Structural, optical, opto-thermal and thermal properties of ZnS-PVA nanofluids synthesized through a radiolytic approach. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 6, 529–536 (2015).

Abd Alelah, S. M., Hussein, M. O. & Khashan, A. A. Fabrication of chitosan/cuo/grape seed extract biocomposite exhibiting synergistic antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 10, 100844 (2025).

Fan, Y. & Picchioni, F. Modification of starch: A review on the application of green solvents and controlled functionalization. Carbohydr. Polym. 241, 116350 (2020).

Ciumac, D. et al. Influence of acyl chain saturation on the Membrane-Binding activity of a short antimicrobial peptide. ACS Omega. 2, 7482–7492 (2017).

Agarwal, S. et al. Chitosan-Acrylic acid biomaterial having antimicrobial nature supports biomineralization and is suitable for bone tissue regeneration. Mater. Adv. 6, 4364–4377 (2025).

Aziz, D. M. et al. Spectroscopic study of wemple-didomenico empirical formula and Taucs model to determine the optical band gap of dye-doped polymer based on chitosan: common poppy dye as a novel approach to reduce the optical band gap of biopolymer. Spectrochim Acta Part. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 325, 125142 (2025).

Ghosh, S., Sarkar, T., Das, A. & Chakraborty, R. Natural colorants from plant pigments and their encapsulation: an emerging window for the food industry. Lwt 153, 112527 (2022).

Florio, F. E. et al. A SmelAAT acyltransferase variant causes a major difference in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) Peel anthocyanin composition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 9174 (2021).

Noda, Y., Kneyuki, T., Igarashi, K., Mori, A. & Packer, L. Antioxidant activity of nasunin, an anthocyanin in eggplant peels. Toxicology 148, 119–123 (2000).

Ichiyanagi, T. et al. Nasunin from eggplant consists of Cis – Trans isomers of Delphinidin 3-[4-(p-Coumaroyl)-l-rhamnosyl (1→ 6) glucopyranoside]-5-glucopyranoside. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 9472–9477 (2005).

Alighadri, T., Tabibiazar, M., Mohammadi, M., Jahanban-Esfahlan, A. & Amarowicz, R. Nasunin, an amazing chemical constituent in eggplants (Solanum melongena L.): A review of its major properties and Health-Promoting effects. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 4, 16–35 (2024).

Agatonovic-Kustrin, S., Morton, D. W., Yusof, A. P. & Md The Use of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to Assess Wine Quality. Mod Chem appl 1, 2 (2013). (2013).

Vasincu, A. et al. Vernonia Kotschyana roots: therapeutic potential via antioxidant activity. Molecules 19, 19114–19136 (2014).

Krejčová, A., Návesník, J., Jičínská, J. & Černohorský, T. An elemental analysis of conventionally, organically and self-grown carrots. Food Chem. 192, 242–249 (2016).

Boumediene, M. et al. Synthesis, conformational studies, vibrational spectra and thermal properties, of new 1,4-(phenylenebis(methylene) bis(methyl-imidazolium) ionic liquids. J. Mol. Struct. 1220, 128731 (2020).

Ramos, S. et al. Development and characterization of electrospun nanostructures using polyethylene oxide: potential means for incorporation of bioactive compounds. Colloids Interfaces. 4, 14 (2020).

Chang, H. et al. Characterization of natural dye extracted from wormwood and purple cabbage for dye-sensitized solar cells. Int. J. Photoenergy 159502 (2013). (2013).

Favaro, L. I. L. et al. Physicochemical characterization of a crude anthocyanin extract from the fruits of Jussara (Euterpe Edulis Martius): Potential for food and pharmaceutical applications. J. Braz Chem. Soc. 29, 2072–2088 (2018).

Ahmed, J. K. Effect of chlorophyll and anthocyanin on the secondary bonds of Poly vinyl chloride (PVC). Int. J. Mater. Sci. Appl. 4, 21 (2015).

Yilmaz Atay, H. Antibacterial activity of chitosan-based systems. in Functional chitosan: drug delivery and biomedical applications 457–489Springer, (2020).

Zasada, L., Chmielniak, D. & Gwizdalska, K. Kaczmarek-Szczepańska, B. Preparation and comprehensive characterization of chitosan-based films enhanced with ferulic acid. Eng. Biomater. 172, 8 (2024).

Xie, Y. et al. Composition analysis and anti-hypoxia activity of polysaccharide from brassica Rapa L. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 47, 528–533 (2010).

Sionkowska, A. Current research on the blends of natural and synthetic polymers as new biomaterials. Prog Polym. Sci. 36, 1254–1276 (2011).

Singhal, A. et al. Polyvinyl alcohol–In 2 O 3 nanocomposite films: synthesis, characterization and gas sensing properties. RSC Adv. 2, 7180–7189 (2012).

Chahal, R. P., Mahendia, S., Tomar, A. K. & Kumar, S. SHI irradiated pva/ag nanocomposites and possibility of UV blocking. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 52, 237–241 (2016).

Pasieczna-Patkowska, S., Cichy, M. & Flieger, J. Application of fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in characterization of green synthesized nanoparticles. Molecules 30, 684 (2025).

Ferreira, L. M. B. et al. Design of chitosan-based particle systems: A review of the physicochemical foundations for tailored properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 250, 116968 (2020).

Mandal, B., Rameshbabu, A. P., Dhara, S. & Pal, S. Nanocomposite hydrogel derived from Poly (methacrylic acid)/carboxymethyl cellulose/aunps: A potential transdermal drugs carrier. Polym. (Guildf). 120, 9–19 (2017).

Missoni, L. L., Ortiz, G. P., Ricci, M. L. M., Toranzos, V. J. & Mochán, W. L. Rough 1D photonic crystals: A transfer matrix approach. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 109, 110012 (2020).

Marangoni, V. S. et al. Template-free assembly of 2D-electrolytes into nanofibres. Mater. Today Chem. 21, 100542 (2021).

Fumoto, E. et al. Determination of carbonyl functional groups in lignin-derived fraction using infrared spectroscopy. Fuel 318, 123530 (2022).

Aziz, S. B. Modifying Poly (vinyl alcohol)(PVA) from insulator to small-bandgap Polymer: A novel approach for organic solar cells and optoelectronic devices. J. Electron. Mater. 45, 736–745 (2016).

Fleischmann, C., Lievenbrück, M. & Ritter, H. Polymers and dyes: developments and applications. Polym. (Basel). 7, 717–746 (2015).

Xing, L., Gu, J., Zhang, W., Tu, D. & Hu, C. Cellulose I and II nanocrystals produced by sulfuric acid hydrolysis of tetra Pak cellulose I. Carbohydr. Polym. 192, 184–192 (2018).

Rostra, J. G., Soler-Carracedo, K., Martín, L. L., Lahoz, F. & Yubero, F. Thermo-optic response of meh-ppv films incorporated to monolithic fabry-perot microresonators. Dye Pigment. 182, 108625 (2020).

Sreeja, S., Sreedhanya, S., Smijesh, N., Philip, R. & Muneera, C. I. Organic dye impregnated poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposite as an efficient optical limiter: structure, morphology and photophysical properties. J. Mater. Chem. C. 1, 3851–3861 (2013).

Do, K. L., Su, M., Mushtaq, A., Ahsan, T. & Zhao, F. Functionalization of silk with Chitosan and rubia cordifolia L. dye extract for enhanced antimicrobial and ultraviolet protective properties. Text. Res. J. 93, 3777–3789 (2023).

Liu, L., Gong, D., Bratasz, L., Zhu, Z. & Wang, C. Degradation markers and plasticizer loss of cellulose acetate films during ageing. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 168, 108952 (2019).

Abdullah, O. G., Aziz, S. B., Omer, K. M. & Salih, Y. M. Reducing the optical band gap of Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) based nanocomposite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 26, 5303–5309 (2015).

Park, S., Baker, J. O., Himmel, M. E., Parilla, P. A. & Johnson, D. K. Cellulose crystallinity index: measurement techniques and their impact on interpreting cellulase performance. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 3, 1–10 (2010).

Tahir, H. B., Abdullah, R. M. & Aziz, S. B. The H + ion transport study in polymer blends incorporated with ammonium nitrate: XRD, FTIR, and electrical characteristics. Results Phys. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2022.105960 (2022).

Alzahrani, E., Asnag, G. M., Yassin, A. Y. & Tailoring Structural, O., and Dielectric properties of PVC / PMMA / PS / ZnO nanocomposites for capacitive energy storage applications tailoring structural, optical, and dielectric properties of PVC / PMMA / PS / ZnO nanocomposites for capacitive. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1149/2162-8777/adb992

Holder, C. F. & Schaak, R. E. Tutorial on powder X-ray diffraction for characterizing nanoscale materials. ACS nano vol. 13 7359–7365 at (2019).

Benítez, J. J. et al. Polyhydroxyester films obtained by non-catalyzed melt-polycondensation of natural occurring fatty polyhydroxyacids. Front. Mater. 2, 59 (2015).

Yang, Z., Shi, Y. & Wang, B. Photocatalytic activity of magnetically anatase TiO2 with high crystallinity and stability for dyes degradation: insights into the dual roles of SiO2 interlayer between TiO2 and CoFe2O4. Appl. Surf. Sci. 399, 192–199 (2017).

D’souza, O. J. et al. Fabrication and study of Poly (vinyl alcohol) film functionalized with Basella Alba stem extract. J. Polym. Environ. 30, 2888–2904 (2022).

Abdullah, O. G., Aziz, S. B. & Rasheed, M. A. Structural and optical characterization of PVA: KMnO4 based solid polymer electrolyte. Results Phys. 6, 1103–1108 (2016).

Uzun, İ. Methods of determining the degree of crystallinity of polymers with X-ray diffraction: a review. J. Polym. Res. 30, 394 (2023).

Chandrasekaran, M., Kim, K. D. & Chun, S. C. Antibacterial activity of Chitosan nanoparticles: a review. Processes 8, 1173 (2020).

Ke, C. L., Deng, F. S., Chuang, C. Y. & Lin, C. H. Antimicrobial actions and applications of Chitosan. Polym. (Basel). 13, 904 (2021).

Sudhakaran, A., Sudhakaran, A. & Sivasenthil, E. Structure-property connections in dual-phase multifunctional barium titanate based nanocomposites: insights from charge density distributions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 318, 129290 (2024).

Alshoaibi, A. Dyes confinement in the nano scale and converting Poly vinyl alcohol to be optical-active Polymeric nanocomposites with high thermal stability. Polym. (Basel). 15, 2310 (2023).

Araújo, E. A. et al. Impact of cellulose properties on enzymatic degradation by bacterial GH48 enzymes: structural and mechanistic insights from processive Bacillus licheniformis Cel48B cellulase. Carbohydr. Polym. 264, 118059 (2021).

Su, Y. et al. Ferric ions modified Polyvinyl alcohol for enhanced molecular structure and mechanical performance. Mater. (Basel). 13, 1–13 (2020).

Al-Muntaser, A. A., Althobiti, R. A., Naim, A., Alzahrani, A. F., Tarabiah, A. E. & E. & Tailoring the optical properties of dye–polymer composite films based on Polyvinyl alcohol doped with phenol red toward flexible optoelectronic applications. Phys. Scr. 99, 65932 (2024).

Liang, X. et al. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based hydrogels: recent progress in fabrication, properties, and multifunctional applications. Polym. (Basel). 16, 2755 (2024).

Zhou, Q., Chen, J., Wang, C., Yang, G. & Janaswamy, S. Version of Record: (2022). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0926669022011529

Sheik, S. et al. Study on the morphological and biocompatible properties of Chitosan grafted silk fibre reinforced PVA films for tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 116, 45–53 (2018).

Aziz, S. B., Abdullah, R. M., Kadir, M. F. Z. & Ahmed, H. M. Non suitability of silver ion conducting polymer electrolytes based on Chitosan mediated by barium titanate (BaTiO3) for electrochemical device applications. Electrochim. Acta. 296, 494–507 (2019).

Aziz, S. B. Role of dielectric constant on ion transport: Reformulated Arrhenius equation. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2527013 (2016). (2016).

Halder, M. & Meikap, A. K. Influence on loading terbium Manganate on optical, thermal and electrical properties of Polyvinyl alcohol nanocomposite films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 30, 4792–4806 (2019).

Ejara, T. M., Balakrishnan, S. & Kim, J. C. Nanocomposites of pva/cellulose nanocrystals: comparative and stretch drawn properties. SPE Polym. 2, 288–296 (2021).

Luo, Y., Tan, G., Dong, G., Ren, H. & Xia, A. A novel photoelectric performance of magnetic CoFe 2 O 4 –. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 26, 6240–6244 (2015).

Choo, K., Ching, Y. C., Chuah, C. H., Julai, S. & Liou, N. S. Preparation and characterization of Polyvinyl alcohol-chitosan composite films reinforced with cellulose nanofiber. Mater. (Basel). 9, 644 (2016).

Kaur, H. et al. Fabrication and characterization of Polyvinyl alcohol-chitosan composite nanofibers for carboxylesterase immobilization to enhance the stability of the enzyme. Sci. Rep. 14, 19615 (2024).

Ren, M., Frimmel, F. H. & Abbt-Braun, G. Multi-cycle photocatalytic degradation of Bezafibrate by a cast Polyvinyl alcohol/titanium dioxide (PVA/TiO2) hybrid film. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 400, 42–48 (2015).

Hanash, F. E., Alenizi, M. A., Alzahrani, E. & Asnag, G. M. Study of optical, thermal, electrical, and impedance properties of Li 4 Ti 5 O 12 -Based PEO / SA biopolymer blend electrolytes for Lithium-Ion batteries study of optical, thermal, electrical, and impedance properties of Li 4 Ti 5 O 12 -Based PEO /. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1149/2162-8777/adb78e

Yang, G. et al. Luminescent Poly(vinyl alcohol)/Carbon Quantum Dots Composites with Tunable Water-Induced Shape Memory Behavior in Different pH and Temperature Environments. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 8, 34744–34754 (2016).

Hess, S. C. et al. Direct synthesis of carbon quantum Dots in aqueous polymer solution: one-pot reaction and Preparation of transparent UV-blocking films. J. Mater. Chem. A. 5, 5187–5194 (2017).

Kuklin, V. et al. Analysis of aluminum oxides submicron particle agglomeration in polymethyl methacrylate composites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 2515 (2023).

Golba, S. & Kubisztal, J. The influence of roughness on the properties of electroactive polypyrrole. Molecules 29, 5436 (2024).

Hossain, S. Optical properties of polymers and their applications. (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. All-organic polymeric materials with high refractive index and excellent transparency. Nat. Commun. 14, 3524 (2023).

Mikheev, Y. A. & Ershov, Y. A. Assignment of the π→ π* and n→ π* transitions to the spectral bands of Azobenzene and dimethylaminoazobenzene. Russ J. Phys. Chem. A. 92, 1499–1507 (2018).

Aziz, S. B. et al. Structural and optical characteristics of pva: C-dot composites: tuning the absorption of ultra Violet (uv) region. Nanomaterials 9, 216 (2019).

Negim, E. et al. Improving biodegradability of Polyvinyl alcohol/starch blend films for packaging applications. Int. J. Basic. Appl. Sci 3, 263 (2014).

Seo, D. et al. Bathochromic shift in absorption spectra of conjugated polymer nanoparticles with displacement along backbones. Macromol. Res. 23, 574–577 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescent response for anthrax bio-indicator: a combination of rare Earth MOF and rhodamine-derived dye. Spectrochim Acta Part. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 229, 117999 (2020).

Chalkias, D. A. et al. High-efficiency quasi-solid state dye-sensitized solar cells using a polymer blend electrolyte with polymer-in-salt conduction characteristics. Sol Energy. 222, 35–47 (2021).

Habeeb, S. A., Birtio, N. A. & Kadhim, H. J. Studying the effect of bio natural dye on optical properties of liquid Poly vinyl alcohol. J. Mater. Sci. Nanatechnol. 4 (04), 6 (2020). (2020).

Larruquert, J. I. Optical properties of thin film materials at short wavelengths. in Optical Thin Films and Coatings 291–356Elsevier, (2018).

Aziz, S. B., Abdullah, O. G., Hussein, A. M. & Ahmed, H. M. From insulating PMMA polymer to conjugated double bond behavior: green chemistry as a novel approach to fabricate small band gap polymers. Polym. (Basel). 9, 626 (2017).

Hazarika, R. & Kalita, B. Effect of oxygen vacancy defects on electronic and optical properties of MgO monolayers: first principles study. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 286, 115974 (2022).

Hareesh, K., Sanjeev, G., Pandey, A. K. & Rao, V. Characterization of UV-irradiated Lexan polycarbonate films. Iran. Polym. J. 22, 341–349 (2013).

Nofal, M. M. et al. Polymer composites with 0.98 transparencies and small optical energy band gap using a promising green methodology: structural and optical properties. Polym. (Basel). 13, 1648 (2021).

Meyzonnette, J. L., Mangin, J. & Cathelinaud, M. Refractive index of optical materials. in Springer Handbook of Glass 997–1045 (2019).

Aithal, S. & Aithal, P. S. ABCD analysis of Dye-doped polymers for photonic applications. IRA-International J. Appl. Sci. 4, 358–378 (2016).

Andam, N., Refki, S., Ishitobi, H., Inouye, Y. & Sekkat, Z. Optical characterization of ultra-thin films of azo-dye-doped polymers using ellipsometry and surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy. in Photonics vol. 8 41Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, (2021).

Savenije, T. J., Ferguson, A. J., Kopidakis, N. & Rumbles, G. Revealing the dynamics of charge carriers in polymer: fullerene blends using photoinduced time-resolved microwave conductivity. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 24085–24103 (2013).

Sudhakaran, A. & Sudhakaran, A. Comprehensive analysis of optical, dielectric, and electrical properties in Al – and Cu – Doped barium Hexaferrite / Cobalt – Zinc ferrite hybrid nanocomposites. J. Electron. Mater. 53, 4622–4644 (2024).

Appenzeller, I. Introduction To Astronomical Spectroscopyvol. 9 (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Fox, M. Optical Properties of Solidsvol. 3 (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Kafle, B. P. Chemical Analysis and Material Characterization by Spectrophotometry (Elsevier, 2019).

Urs, T. G. et al. Determination of force constant and refractive index of a semiconducting polymer composite using uv/visible spectroscopy: a new approach. Indian J. Phys. 91, 53–56 (2017).

Pötzsch, R., Stahl, B. C., Komber, H., Hawker, C. J. & Voit, B. I. High refractive index polyvinylsulfide materials prepared by selective radical mono-addition thiol-yne chemistry. Polym. Chem. 5, 2911–2921 (2014).

Aziz, S. B., Rasheed, M. A., Hussein, A. M. & Ahmed, H. M. Fabrication of polymer blend composites based on [PVA-PVP](1 – x):(Ag2S) x (0.01 ≤ x ≤ 0.03) with small optical band gaps: structural and optical properties. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 71, 197–203 (2017).

Saini, I. et al. Tailoring of electrical, optical and structural properties of PVA by addition of ag nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 139, 802–810 (2013).

Salim, E., Magdy, A., EL-Farrash, A. H. & El-Shaer, A. Optimizing optical, dielectric, and electrical properties of Polyvinyl alcohol/polyvinyl pyrrolidone/poly(3,4-ethylene dioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate/NiO-based polymeric nanocomposites for optoelectronic applications. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–12 (2025).

You, L. et al. Energy storage performance of polymer-based dielectric composites with two-dimensional fillers. Nanomaterials 13, 2842 (2023).

Biskri, Z. E., Rached, H., Bouchear, M., Rached, D. & Aida, M. S. A comparative study of structural stability and mechanical and optical properties of fluorapatite (Ca 5 (PO 4) 3 F) and lithium disilicate (Li 2 Si 2 O 5) components forming dental glass–ceramics: first principles study. J. Electron. Mater. 45, 5082–5095 (2016).

Tan, C. Z. Dependence of the refractive index on density, temperature, and the wavelength of the incident light. Eur. Phys. J. B. 94, 139 (2021).

Hassanien, A. S. & Sharma, I. Dielectric properties, optoelectrical parameters and electronic polarizability of thermally evaporated a-Pb-Se-Ge thin films. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 622, 413330 (2021).

Yassin, A. Y., Abdelrazek, E. M., Abdelghany, A. M. & Abdallah, E. M. Incorporated au/se nanoparticles into HPMC/CMC blend for enhancing structural, optical and morphological properties: hybrid nanocomposites for optoelectronic applications. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 154, 115721 (2024).

Mohammed, H. A., Mohammed, P. A. & Aziz, S. B. Physical characteristics of polymer composites based on PVA doped with Mn2 + metal complexes synthesized by green approach: insights to linear and optoelectronic optical properties. Oxf. Open. Mater. Sci. 5, itaf003 (2025).

Sudhakaran, A., Sudhakaran, A. & E, S. Multifunctionality of AlBaFe12O19 /CoZnFe2O4 hybrid nanocomposite: promising structural, elastic, morphological, compositional, optical, and magnetic properties. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 174, 111134 (2023).

Sudhakaran, A., Sudhakaran, A. & Sivasenthil, E. Electron density effect of hybrid ferrites on structural, spectroscopic, optical, and magnetic properties in (BaTiO3) (1-x) + (ZnFe2O4) x nanoceramics. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 34, 1–19 (2023).

Riungu, G. G., Mugo, S. W., Ngaruiya, J. M., John, G. M. & Mugambi, N. Optical band energy, Urbach energy and associated band Tails of nano crystalline TiO2 films at different annealing rates. Am. J. Nanosci. 7, 28–34 (2021).

Sudhakaran, A. & Sudhakaran, A. Multifunctionality of AlBaFe12O19/CoZnFe2O4 hybrid nanocomposite: promising structural, elastic, morphological, compositional, optical, and magnetic properties. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 174, 111134 (2023).

Mamand, D. M. et al. Enhanced optical properties of Chitosan polymer doped with orange Peel dye investigated via UV–Vis and FTIR analysis. Sci. Rep. 15, 3232 (2025).

Mamand, D. M. et al. Optical band gap modulation in functionalized Chitosan biopolymer hybrids using absorption and derivative spectrum fitting methods: A spectroscopic analysis. Sci. Rep. 15, 3162 (2025).

Brza, M. A. et al. Tea from the drinking to the synthesis of metal complexes and fabrication of PVA based polymer composites with controlled optical band gap. Sci. Rep. 10, 18108 (2020).

Adachi, S. Optical Constants of Crystalline and Amorphous Semiconductors: Numerical Data and Graphical Information (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

George, P. & Chowdhury, P. Complex dielectric transformation of UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra for estimating optical band-gap energies and materials classification. Analyst 144, 3005–3012 (2019).

Agusti, G., Jordan, O., Andersen, G., Doelker, É. & Chevalier, Y. Radiopaque iodinated ethers of Poly (vinyl iodobenzyl ether) s: synthesis and evaluation for endovascular embolization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 132, 41791 (2015).

Kato, M. et al. Separation of 100 nm-sized nanoparticles using a poly-Lys-modified monolith column. RSC Adv. 15, 3147–3153 (2025).

Abdul Jabbar, G. A. H., Saeed, A. A. & AL-Kadhemy, M. F. H. Impact of ZnO nanoparticle on the structural and optical properties of Poly(vinyl alcohol) Film. Al-Mustansiriyah J. Sci. 33, 153–161 (2022).

Nimrodh Ananth, A., Umapathy, S., Sophia, J., Mathavan, T. & Mangalaraj, D. On the optical and thermal properties of in situ/ex situ reduced ag np’s/pva composites and its role as a simple SPR-based protein sensor. Appl. Nanosci. 1, 87–96 (2011).

Al-Taa’y, W. A. Optical properties of Poly (vinyl alcohol) PVA films doped with Fe citrate. J. Al-Nahrain Univ. Sci. 17, 95–102 (2017).

Kavasoglu, N. & Bayhan, M. Air moisture sensing properties of ZnCr 2 O 4 – K 2 CrO 4. Turkish J. Phys. 29, 249–255 (2005).

Tahir, K. J., Obeed, H. H. & Shiltagh, N. M. Study optical properties of R6G dye doped in polymer PVA. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1234, 012048 (2019).

Swapan, Bhuniaa & Manik, N. B. Pallab Kumar Dasband Effect of dye concentration on the band gap of PVA turmeric composite film. J. Indian Chem. Soc., 97, 2937–2942 (2020).

Gnana Kiran, M., Krishna Jyothi, N., Samatha, K., Rao, M. P. & Prasad, V. B. V. N. Studies on optical properties of Pva based complex polymer electrolyte. Rasayan J. Chem. 14, 760–767 (2021).

Hasanah, M. et al. Sustainable photocatalyst fabrication from Silau River-derived SiO2: PVA/TiO2/SiO2 for water purification. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 11, 101059 (2025).

Saxena, P., Shukla, P. & Gaur, M. S. Thermal analysis of polymer blends and double layer by DSC. Polym. Polym. Compos. 29, S11–S18 (2021).

Remiš, T. et al. Study on structure, thermal behavior, and viscoelastic properties of nanodiamond-reinforced Poly (vinyl alcohol) nanocomposites. Polym. (Basel). 13, 1426 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Water governs the mechanical properties of poly(vinyl alcohol). Polymer (Guildf) 213, 123330 (2021).

Tsioptsias, C. On the specific heat and mass loss of thermochemical transition. Chem. Thermodyn. Therm. Anal. 8, 100082 (2022).

Tsioptsias, C., Fardis, D., Ntampou, X., Tsivintzelis, I. & Panayiotou, C. Thermal behavior of Poly (vinyl alcohol) in the form of physically crosslinked film. Polym. (Basel). 15, 1843 (2023).

Anandalli, M. H. et al. AIP Publishing,. Mechanical and thermal studies of brilliant green dye doped poly (vinyl alcohol) polymer composite. in AIP conference proceedings vol. 2115 (2019).

Mohammed, M. I. & El-Sayed, F. PEG’s impact as a plasticizer on the PVA polymer’s structural, thermal, mechanical, optical, and dielectric characteristics. Opt. Quantum Electron. 55, 1–22 (2023).

Hiremani, V. D. et al. Dominant nature of 7-hydroxy 4-methyl coumarin dye on thermal, fluorescence and antimicrobial properties of PVA/OMS blend films. J. Polym. Res. 28, 353 (2021).

Delpouve, N., Delbreilh, L., Stoclet, G., Saiter, A. & Dargent, E. Structural dependence of the molecular mobility in the amorphous fractions of polylactide. Macromolecules 47, 5186–5197 (2014).