Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is cancer of the colon or bowel. Every year, more than 1.8 million cases of colorectal cancer are reported, with 850,000 deaths. There are several genetic causes of this disease. However, one of the main reasons is the overexpressed KRAS gene that can cause uncontrolled cell division and tumor development. The present study is focused on the identification of potential phytochemicals that can inhibit the KRAS protein from being overexpressed in CRC. For this study, phytochemicals were retrieved from the IMPPAT library, which has 17,967 phytochemical compounds. The compounds were further screened based on the ADMET criteria. The screened compounds were then docked against the KRAS protein using a molecular docking approach, and the binding energies were calculated. Indicating a considerable affinity for interacting with the KRAS protein, it was shown that compound-1 had a binding energy of -9.7 kcal/mol upon analysis. Furthermore, for docking reasons, the anticancer medication fruquintinib, which has been authorized by the FDA, was used as a reference chemical. A binding energy of -9.4 kcal/mol was observed for the reference chemical, as was mentioned before. To find out the reactivity of the selected compound, DFT analysis was performed. The protein-ligand complex was also subjected to molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. Post simulation analysis, such as RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and no of hydrogen bonds, indicated a stable protein-ligand complex.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is cancer of the colon or bowel. Every year, more than 1.8 million cases of colorectal cancer are reported, with 850,000 deaths. The death rate of colorectal cancer has been reported in previous studies, where it has been indicated that this cancer causes deaths that are the second-highest among all cancers1. The increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in the recent past has been reported, and it is estimated that the death rate may increase to 70% by the year 20352. Colon and rectal adenomas can turn into cancer due to various genetic and epigenetic changes that build up over time in the originally healthy cells of the rectum and colon.

The prevalence of CRC in the eastern and western locations has been discussed in the previous studies3. As far as the eastern countries are concerned, it has been reported that this cancer is more prevalent in the eastern regions that are economically strong, while it is less prevalent in the western regions that are economically less strong. The incidences of colorectal cancer in China show that approximately 20% patients suffering from this disease belong to the age group that is less than 30 years. In addition, it has been noted that this disease development is 12 years earlier as compared to Western countries4.

From a molecular standpoint, about 20% of CRC cases are caused by genetic changes, and first-generation relatives of CRC patients have a significant risk5. Genetic disorders that increase the risk of colorectal cancer include mutations in the familial adenomatous polyposis and Mismatch Repair Gene6. This disease shows a combination of different causes and symptoms7. Chromosomal instability is the prime molecular pathway whose dysregulation can lead to CRC8. It includes different alterations in the structure and number of chromosomes, including gains or losses of chromosome segments and alterations in the tumor suppressor gene.

Several mutations can lead to the CRC. These mutations can be either in the tumor suppressor genes, such as KRAS, p53, BRAF, and APC, or in oncogenes9. These genes regulate cell division and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) replication and are crucial in the initiation and progression pathways. These pathways can lead to cell proliferation, playing key roles in the development and progression of the disease. Although treatments like chemotherapy (FOLFIRINOX) and surgery can improve survival, they are not effective in managing advanced stages of colorectal cancer.

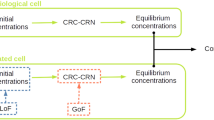

RAS genes encode proteins that help regulate cells. In 1975, researchers at the National Institutes of Health, led by Scolnick, discovered the first two RAS genes, HRAS and KRAS, while studying cancer-causing viruses10. The human versions of these genes were identified in 1982 and have been linked to many types of cancer. Among the three human RAS genes, KRAS mutations are the most closely related to cancers11. A KRAS gene mutation is present in around 40–52% of cases of colorectal cancer12. A study indicated that more than 40% of the cases having CRC have KRAS gene mutations. The KRAS gene encoding GTPase protein is a part of RAS family (GTPase) found on chromosome 1213, the protein product has molecular weight of 21 kDa, 189 amino acids, and binds GDP and GTP14 and its several mutations have been reported15. Constitutive activation of the KRAS gene, which codes for the GTPase protein, is caused by the mutations. This gene acts as a molecular switch, continuously stimulating downstream signaling pathways, including those that promote cell survival and proliferation, which ultimately leads to the proliferation of cells and the development of tumor formation16.

There are several genetic and molecular variables that may influence the development and progression of colorectal cancer. The MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathways are two of the most important contributors to these pathways. The MAPK/ERK pathway is often mutated or overactive in colorectal cancer due to the KRAS gene encoding a GTPase protein. This pathway is involved in drug resistance, inflammation, apoptosis, metastasis, and cancer cell growth. Inhibitors targeting this pathway have shown promising anti-cancer effects. Concerning this study, Fruquintinib (brand name Fruzaqla), which is an anti-cancer drug, is being used currently for treating colorectal cancer17,18. This study was undertaken to find out the potential phytochemicals against the KRAS gene encoding GTPase protein in CRC.

Methodology

3D structure retrieval and verification

3D structure retrieval

For the structure retrieval of the KRAS gene, which is overexpressed in CRC, the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) (https://www.uniprot.org/) database was first consulted for detailed functional information. UniProt provides extensive data on proteins and their functional annotations19. The KRAS gene encoding GTPase protein consisting of 189 amino acids with a molecular weight of approximately 21.6 kDa was recovered from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) using the RCSB-PDB ID: 7SCW, which has a resolution of 1.98 Å. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) ( https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb7SCW/pdb) is a crucial resource for studying the 3D structures, aiding research and education in many fields20.

Structure verification

After structure retrieval, it was verified using tools like Verify 3D21, ERRAT22, and PROCHECK23 to evaluate the protein quality, the geometric quality of the protein structure and the protein model’s compatibility with its amino acid sequence (Scheme 1).

Ligand and protein Preparation

The receptor was prepared using Discovery Studio Visualizer (DSV)24. Protein databank (PDB) was used for the retrieval of protein, and this structure was cleaned and edited using DSV24. All the heteroatoms and water molecules attached were removed from the KRAS gene encoding the GTPase protein. The cleaned protein was prepared by using AutoDock1.5.7v tools, and the PDB format was changed to pdbqt25.

Ligand library

17,967 phytochemicals were chosen from the online source phytochemical library known as Indian Medicinal Plants, Phytochemistry and Therapeutics 2.0 (IMPPAT 2.0) (https://cb.imsc.res.in/imppat/). The phytochemicals were chosen from this library26. A total of 17,967 ligands were filtered according to the ADMET criteria given in Table 1. 95 compounds were filtered out that fulfilled the ADMET criteria26,27. From 95 ADMET properties of the top ten ligands mentioned here fulfilled all these criteria for a drug. The ADMET properties and criteria are mentioned in Table 1.

Ligand preparation

Ligand preparation was performed using Discovery Studio Visualizer24 to ensure accurate docking. Initially, the chemical structures of the ligands were imported and formatted appropriately within the software. Hydrogen and partial charges were added. The ligands were subsequently converted into the required file format for docking studies (e.g., PDBQT). Finally, the prepared ligands were validated within Discovery Studio to confirm their suitability for the docking process.

Active site determination

The active site for docking was determined using Discovery Studio24 and CASTp28. First, the 3D structure of the receptor was attained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and analyzed using Discovery Studio24. The 2D diagram in the discovery studio was used to determine the active site and the amino acid residues that were found there, and CASTp28 was the same, which confirms the active site where the ligand binds to the receptor.

Grid box preparation

A grid box was prepared after finding which ligands were going to bind with the receptor. The size and spacing of the grid points inside the box were adjusted to ensure accurate positioning and evaluation of ligands29. Finally, grid information was saved in a format (pdbqt) that our docking software can use, so we can study how ligands interact with the receptor in our research. In terms of the KRAS gene, the dimensions were 29.224 Å, 22.434 Å, and − 6.244 Å. The exhaustion thresholds were set at 8 and 0, respectively, and the box size coordinates were 24, 26, and 24 in x, y, and z.

Molecular docking

AutoDock1.5.7v tools were used for docking25 the selected phytochemicals with the KRAS gene encoding GTPase protein receptors. Following the docking of 95 phytochemicals that met the ADMET requirements, the top 10 ligands with the lowest binding energy (high affinity) were chosen for further study30. Following the selection, the interaction may be visualized in the form of hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic bonds, and van der Waals forces. Subsequent analysis was performed with the help of the BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer application31. According to the fact that it has the lowest binding energy, the ligand was selected for further research.

Reference compound molecular docking

To compare it with the reference compound, Fruquintinib, which is an approved FDA drug, was used against KRAS17. It is an anticancer drug having the PubChem ID: 44,480,399. PubChem was used to retrieve the SDF structure of this compound (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Fruquintinib). The compound was then opened in the MGL tools, Gasteiger charges and polar hydrogens were added25. The compound was then saved in PDBQT format. After the preparation of the reference compound, it was docked against the KRAS receptor using the same grid box dimensions and parameters as mentioned above for the phytochemicals. The interactions between the receptor and the ligand were visualized after docking using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer31. Its binding energy was − 9.4 kcal/mol, while the IMPPAT selected ligand indicated − 9.7 kcal/mol energy, making it a potential drug against colorectal cancer (CRC).

Density functional theory

The ten ligands with the lowest binding energies were investigated for DFT analysis using Gaussian 9.0. The energy gap known as ΔE32 is the difference between the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) and the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO). The compounds were optimized using (DFT/B3LYP), with 6-31G as the basis to predict molecule structure B3LYP method33,34. Gaussian 09 was used for performing the DFT analysis, and the resulting file, .chk, was viewed using Gauss View 6.035.

Molecular dynamics simulation

To evaluate the stability of the system, a 100 ns Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation was performed36. Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) was used to monitor structural changes, root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) was used to evaluate flexibility, the radius of gyration (Rg) was used to measure compactness, and hydrogen bond formation was used to observe interaction stability. All of these metrics were analyzed in order to identify the stability of the process36.

Results

Structure retrieval

Protein structure that was retrieved from Protein Data Bank with RCSB-PDB ID: 7SCW and resolution 1.98 as given below (Fig. 1):

Structure verification

A verification of the protein’s structure was carried out with the assistance of the verify 3D, ERRAT, and PROCHECK programs. Ramachandran plot analysis under the PROCHECK program revealed that 92.9% residues were present in the permitted region, while 7.1 of % residues were present in the additionally permitted region23. The Ramachandran plot (Fig. 1S) was 92.9% and remains in additional permitted regions were 7.1% for the KRAS gene encoding GTPase protein. The quality score in the ERRAT program was 96.12 (Fig. 2S)22, while Verify 3D presented the status of the protein structure as ‘pass’ (Fig. 3S)21.

Screened ligands

Ligands were screened based on ADMET properties, which are essential in evaluating the pharmacokinetic and toxicological properties of drug candidates. From the ligand library, 95 compounds were screened, from which the top 10 with the lowest binding energy are given here with their ADMET properties and all fulfilling criteria of ADMET properties recommended ranges (Pollastri, 2010).

Active site determination

The active site for docking was determined using Discovery Studio Visualizer24 and CASTp28. The amino acids that were common in both Discovery Studio and CASTp for the KRAS gene encoding GTPase protein were GLY12, GLY13, VAL14, GLY15, LYS16, SER17, ALA18, PHE18, VAL29, PRO34, THR35, THR58, GLY16, GLN61, ASN116, LYS117, ASP119, LEU120, SER145, ALA146, and LYS147. These were the amino acids that were found to be common in both software and confirmed that the KRAS active site contains these amino acids where receptor bound.

Docking analysis

95 phytochemicals filtered through ADME criteria were docked against the KRAS receptor. IUPAC names, PubChem IDs, structures, and chemical formulae are included in Tables 2 and 3 for KRAS, respectively. These tables also provide the list of the top 10 ligands of the KRAS protein that have the lowest energy interactions (highest binding affinity). Other ligands are indicated in the additional data. It was noted that the lowest energy ranged from − 9.7 kcal/mol to -9.0 kcal/mol. 2D representation of these ligands is mentioned in Fig. 4S.

KRAS molecular docking analysis

An example of a ligand that has one of the lowest binding energies for compound 1 (2 S,3R,4 S,5 S,6R) ((6aR, 11aR)) -2-[[ Using the PubChem ID 23724664, we found the compound known as methyl-9-acetate-6a,11a-dihydro-6 H-benzofuro[3,2-c]chromen-3-yl]oxy. Hydroxymethyl or -6- With a binding energy of -9.7 kcal/mol, oxane-3,4,5-triol seemed to be the least energetic. Using the BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer, the interactions that took place in the active sites were shown. As shown in Fig. 2, the interactions that take place between the ligand and the KRAS receptor include the following: pi-alkyl ALA 18, ALA 146, pi-cation LYS 117, hydrogen bonding THR 35, GLN 61, and Van der Waals forces GLY 12, THR 58, GLY 60, GLY 14, ALA 59, LYS 16, PRO 34, ASP 33, GLU 31, ASP 30, SER 17, TYR 32, GLY 15, ASN 116, ASP 119, and LYS 47. In the pi-alkyl interaction that was seen between ALA 18, ALA 146, and LYS 117, the pi-electron of the aromatic group and the electron of any alkyl group interact respectively. Three pi-alkyl bonds are formed by ALA 18 with the aromatic rings of the ligand. These bonds had distances of 5.17 Å, 4.91 Å, and 5.05 Å, respectively. In addition, ALA 146 can form pi-alkyl connections, with diameters of 3.94 Å and 4.88 Å. On the other hand, LYS 117 has three bonds, with dimensions of 4.97 Å, 4.74 Å, and 4.11 Å. Two different bond types are displayed in LYS 117: a pi-cation bond and a pi-pi T-shaped bond. Table 1S and Table 2 S lists the bond angles and binding energies, respectively.

(i) A zoomed-in view of compound 1 that is bound to the active site of KRAS, which is located on the right side of the image. The interaction between compound-1 and KRAS is shown in two different ways: (A) a two-dimensional view of the interacting residues and bond distance, and (B) a three-dimensional perspective of the same. (Made from the Discovery studio visualizer tool (2021 edition).

KRAS Docking analysis with fruquintinib

In this study, Fruquintinib served as a reference compound. The analysis revealed that the selected ligand (CID_23724664) was binding strongly with the KRAS protein, showing binding energy of -9.7 kcal/mol as compared to the Fruquintinib that showed binding energy of -9.4 kcal/mol. The interacting residues were visualized through DSV31, which indicated that the active site residues were also involved in the interaction with the ligand (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6). As can be seen in Fig. 7, the interactions consisted of covalent bonds between ASP 33 and GLU 31, pi-alkyl PRO 34, and Van der Waals forces between ASP 33 and GLN 61a. When combined with 2.57, PRO 34 creates a pi-alkyl bond.

(i) indicates the interaction of the KRAS with the reference ligand, Fruquintinib; the right side image indicates a more closed interaction. (ii) Interaction between Fruquintinib and KRAS (A) shows a 2D interaction diagram, and type of bonding interactions (B) shows a 3D interaction diagram of interacting residues and distance. (Made from the Discovery studio visualizer tool (2021 edition).

DFT analysis

Figure 4 illustrates the determination of the energy gap (ΔE) for each of the ten ligands that were selected after docking. This was accomplished by calculating the difference between the ELUMO and EHOMO potentials32. The change in energy between the HOMO and LUMO has been indicated in the image for CID_23724664, is 0.19685 eV provides important information regarding the reactivity of the ligand with the receptor35. This low ΔE value suggested the reactivity of the compound (CID_23724664). While a lower HOMO–LUMO energy gap (ΔE) can indicate that a molecule is more chemically reactive and potentially more likely to interact with other molecules, it’s important to note that this doesn’t directly reflect how strongly it will bind to a protein. Binding affinity is more accurately determined using methods like molecular docking scores or binding free energy calculations, which consider the overall interaction between the ligand and the protein.

Molecular dynamics simulation results

In Fig. 5, the RMSD indicated that at the start, the protein and ligand show some structural configuration; however, it stabilized over time (Fig. 5). The second half of the RMSD analysis indicates that the protein-ligand complex is stable throughout the trajectory. The overall analysis reveals the protein-ligand complex stability.

In Fig. 6, the relative molecular weight (RMSF) of the protein along the trajectory is shown to highlight the variation of the individual amino acid residues of the KRAS gene that codes for the GTPase protein. This provides insights into the structural dynamics of the protein. The analysis of the first 1000 frames shows that there was some variation seen in the KRAS gene encoding GTPase protein with high flexibility, indicated by peaks. However, these regions were not included in the active site residues. In addition, some changes were observed in the last 1000 frames. After 50 amino acid residues, two peaks were observed at amino acid no.55 and amino acid no.60. Similarly, a slight difference in RMSF value was observed at amino acid no.130. Overall, the structure remained consistent.

In Fig. 7, the Rg graph reveals that the KRAS gene encoding GTPase protein shows some little variations in the compactness of the protein. This analysis is necessary as it indicates the compactness of the protein structure. Moreover, stability and the native conformation of the protein are also supported by this analysis. The looser structure will indicate the higher values of Rg. In this analysis, we found that the protein’s structure showed compactness in its structure throughout the simulation run. The average Rg value was around 20 Å.

During the simulation, hydrogen bonds were established, and their analysis is shown in Fig. 8. This study provides a representation of the total number of hydrogen bonds that were formed during the simulation. However, the average number of hydrogen links discovered in the simulation trajectory was sixty. It was observed that the hydrogen bonds ranged from thirty to eighty. The stability of the protein and ligand combination may also be determined by the number of hydrogen bonds that are in the complex. This suggests that the protein and the ligand that we proposed have a positive interaction with one another. Based on the examination of the simulation, it was discovered that the number of hydrogen bonds that occurred during the simulation procedure averaged somewhere around 70.

Discussion

Colorectal cancer (CRC) shows global prevalence and is a major health problem across the world. Both its incidence and mortality rates are expected to rise34. Early diagnosis of CRC can often be treated effectively. Limited access to early diagnosis and treatment in developing regions underscores the need for better management strategies. Mutations in the KRAS gene encoding GTPase protein account for 30–50% of CRC cases37 that can lead to rapid cell division and cell survival. These mutations typically affect codons 12, 13, and 6138 because of this, the PI3K-AKT-mTOR and RAF-MEK-ERK pathways are activated in a form that is constitutive form. These pathways are crucial for tumor progression.

In previous studies, it was stated that Fruquintinib is an anti-cancer drug that is currently used for treating colorectal cancer17 and this study found CID_23724664 (Medicarpin 3-O-glucoside) ( https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ ) as potential candidate to replace this drug for treating colorectal cancer because of its strong binding interaction (-97.7 kcal/mol) with target protein and it can inhibit pathways that result in colorectal cancer. In order to find out how reactive the ligands were, a Density Functional Theory (DFT) study was carried out39. In past studies, low values of ΔE suggested high binding affinity and stability of the interaction between the molecule and the target protein. In this study, the ΔE was 0.19685 eV, which is low which suggests that this ligand can bind effectively with the target protein or receptor39. The library of phytochemicals was selected as these have advantages over chemical compounds with low toxicity and have the potential to target multiple proteins for the improved efficacy and results26.

The previous studies have evaluated the impact of some compounds against NFKB1 and COX-2 (prime candidates causing CRC) in 2023. The interactions of these two proteins with vitexin and aspirin were evaluated through computational analysis. The study revealed that vitexin and aspirin made the two proteins more stable when bound to them. Moreover, the study also indicated that when both (vitexin and aspirin) were combinedly present against40. The combinatorial treatment indicated that the protein was more stable and flexible throughout the trajectory. In addition, the inhibition of the KRAS protein was evident by the higher binding affinity and increased compactness of the protein structure when bound to both vitexin and aspirin. In the current study, the analysis of RMSD showed that the protein-ligand complex was more stable as compared to protein alone. In addition, the KRAS gene encoding GTPase protein was found to be less fluctuating in the last 1000 frames as compared to the initial 1000 frames of the trajectory, when individual amino acid residues were analyzed through RMSF analysis. Moreover, the Rg analysis revealed that the protein structure was compact throughout the trajectory and a lot of hydrogen bonds were formed (an average of 70) during the trajectory, all indicating the stability of our protein-ligand complex41.

Compound 23,724,664 is predicted to bind at a critical allosteric pocket overlapping with the switch I/II region of KRAS, which is essential for effector interaction. The binding may stabilize an inactive conformation, potentially preventing interaction with RAF and other downstream signaling partners. This interference could suppress MAPK/ERK pathway activation, consistent with the intended inhibitory effect. The stable interaction profile observed over the simulation time supports this proposed mechanism. It is clear from these data that the interaction between the KRAS protein and the ligand (CID_23724664) is both stable and dynamic39. It is possible that the combination of these novel KRAS-targeted ligands with other therapies and the use of improved drug delivery technologies, like as nanoparticles, might significantly enhance therapeutic results, delivering major improvements over the treatments that are now available for patients with colorectal cancer42.

Conclusion

This study highlights the KRAS gene encoding GTPase protein overexpression in colorectal cancer and evaluates CID_23724664 (Medicarpin 3-O-glucoside) as a promising alternative to the current drug, fruquintinib. In silico docking reveals CID_23724664 has a slightly lower binding energy (-9.7 kcal/mol) compared to Fruquintinib (-9.4 kcal/mol), suggesting it may offer a stronger and more stable interaction with KRAS. These findings suggest CID_23724664 could improve CRC treatment, but further experimental and clinical studies are needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety.

Limitations of the study

The lack of in vitro and in vivo validation is a key limitation, and future experimental studies are essential to confirm the compound’s biological efficacy and pharmacological relevance.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sawicki, T. et al. A Review of Colorectal Cancer in Terms of Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Development, Symptoms and Diagnosis, Cancers (Basel), (2021).

Huang, B. et al. Qingjie Fuzheng granule prevents colitis-associated colorectal cancer by inhibiting abnormal activation of NOD2/NF-κB signaling pathway mediated by gut microbiota disorder. Chin. Herb. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chmed.2025.04.001 (2025).

Tong, G. et al. Effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on biological behavior of colorectal cancer cells by regulating PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 901559 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of colorectal cancer in China. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 32, 729–741 (2020).

Wang, K. et al. Extracellular matrix stiffness regulates colorectal cancer progression via HSF4. J. Experimental Clin. Cancer Res. 44 (1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-025-03297-8 (2025).

Rebuzzi, F., Ulivi, P. & Tedaldi, G. Genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer: how many and which genes to test? Int. J. Mol. Sci., 24 (2023).

He, B. et al. A fusion model to predict the survival of colorectal cancer based on histopathological image and gene mutation. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 9677. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91420-2 (2025).

Khan, S. et al. Synthesis, in vitro biological evaluation and in silico molecular docking studies of indole based thiadiazole derivatives as dual inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylchloinesterase. Molecules, 27(21), p.7368. (2022).

Shakeel, A. et al. Polymer based nanocomposites: A strategic tool for detection of toxic pollutants in environmental matrices. Chemosphere, 303, p.134923. (2022).

Hussain, R. et al. Synthesis of novel benzimidazole-based thiazole derivatives as multipotent inhibitors of α-amylase and α-glucosidase: in vitro evaluation along with molecular docking study. Molecules, 27(19), p.6457. (2022).

Hood, F. E., Sahraoui, Y. M., Jenkins, R. E. & Prior, I. A. Ras protein abundance correlates with Ras isoform mutation patterns in cancer. Oncogene 42, 1224–1232 (2023).

Ye, J. et al. Tissue gene mutation profiles in patients with colorectal cancer and their clinical implications. Biomed. Rep. 13, 43–48 (2020).

Riaz, T. et al. Phyto-mediated synthesis of nickel oxide (NiO) nanoparticles using leaves’ extract of Syzygium cumini for antioxidant and dyes removal studies from wastewater. Inorganic Chemistry Communications, 142, p.109656. (2022).

Kim, H. J., Lee, H. N., Jeong, M. S. & Jang, S. B. Oncogenic KRAS: Signaling and Drug Resistance, Cancers (Basel), (2021).

Bteich, F. et al. Targeting KRAS in colorectal cancer: A bench to bedside review. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 24 (2023).

Rizwan, K. et al. Phytochemistry and diverse Pharmacology of genus mimosa: A review. Biomolecules 12 (1), 83 (2022).

Stucchi, E. et al. Fruquintinib as new treatment option in metastatic colorectal cancer patients: is there an optimal sequence? Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 25, 371–382 (2024).

Roney, M., Mohd, M. F. F. & Aluwi The Importance of in-silico Studies in Drug Discovery (Intelligent Pharmacy, 2024).

Abas, M. et al. Designing novel anticancer sulfonamide based 2, 5-disubstituted-1, 3, 4-thiadiazole derivatives as potential carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. J. Mol. Struct., 1246, p.131145. (2021).

Burley, S. K. et al. RCSB protein data bank: powerful new tools for exploring 3D structures of biological macromolecules for basic and applied research and education in fundamental biology, biomedicine, biotechnology, bioengineering and energy sciences. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D437–D451 (2021).

Eisenberg, D., Luthy, R. & Bowie, J. U. VERIFY3D: assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Methods Enzymol. 277, 396–404 (1997).

Silva-Junior, E. F. et al. Dynamic simulation, Docking and DFT studies applied to a set of anti-Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in the enzyme beta-Secretase (BACE-1): an important therapeutic target in alzheimer;s disease. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 13, 266–274 (2017).

Wlodawer, A. Stereochemistry and validation of macromolecular structures. Methods Mol. Biol. 1607, 595–610 (2017).

Haque, A. et al. Interaction analysis of MRP1 with anticancer drugs used in ovarian cancer: in Silico approach. Life (Basel), 12 (2022).

Du, L. et al. Dockey: a modern integrated tool for large-scale molecular Docking and virtual screening. Brief. Bioinform., 24 (2023).

Vivek-Ananth, R. P., Mohanraj, K., Sahoo, A. K. & Samal, A. IMPPAT 2.0: an enhanced and expanded phytochemical atlas of Indian medicinal plants. ACS Omega. 8, 8827–8845 (2023).

A. Ullah, N.I. Prottoy, Y. Araf, S. Hossain, B. Sarkar, A. Saha, Molecular Docking and Pharmacological Property Analysis of Phytochemicals from Clitoria Ternateaas Potent Inhibitors of Cell Cycle Checkpoint Proteins in the Cyclin/CDK Pathway in Cancer Cells, Comput. Mol. Biosci., 09 (2019) 81–94.

Koshy, C. M., Asirvatham, D., Majumdar, R. & Sugumar, S. In Silico structural and functional characterization of a hypothetical protein from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia SRM01. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 16, 1167–1178 (2022).

Beg, M. A. et al., Ankara Universitesi Eczacilik Fakultesi Dergisi, 5–5. (2021).

Abdul-Hammed, M. et al. Virtual screening, ADMET profiling, PASS prediction, and bioactivity studies of potential inhibitory roles of alkaloids, phytosterols, and flavonoids against COVID-19 main protease (M(pro)). Nat. Prod. Res. 36, 3110–3116 (2022).

Saah, S. A. et al. Docking and Molecular Dynamics Identify Leads against 5 Alpha Reductase 2 for Benign Prostate Hyperplasia Treatment, J. Chem., (2023) 1–20. (2023).

Delgado-Montiel, T., Soto-Rojo, R., Baldenebro-Lopez, J. & Glossman-Mitnik, D. Theoretical Study of the Effect of Different pi Bridges Including an Azomethine Group in Triphenylamine-Based Dye for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells, Molecules, 24 (2019).

Wu, X. et al. Small molecular inhibitors for KRAS-mutant cancers. Front. Immunol. 14, 1223433 (2023).

Hossain, M. S. et al. Colorectal cancer: A review of carcinogenesis, global epidemiology, current challenges, risk factors, preventive and treatment strategies. Cancers (Basel), 14 (2022).

Sangeetha, K. G., Aravindakshan, K. K. & Experimental, N. B. O. NLO and Docking analysis of a novel ligand derived from Vanillin and N(4)-methyl-N(4)-phenylthiosemicarbazide and its transition metal complexes. Results Chem., 4 (2022).

Haji-Allahverdipoor, K. et al. Insights into the effects of amino acid substitutions on the stability of reteplase structure: A molecular dynamics simulation study. Iran. J. Biotechnol. 21, e3175 (2023).

Alipourgivi, F. et al. Genetic alterations of NF-kappaB and its regulators: A rich platform to advance colorectal cancer diagnosis and treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 25 (2023).

Munoz-Maldonado, C., Zimmer, Y. & Medova, M. A comparative analysis of individual RAS mutations in cancer biology. Front. Oncol. 9, 1088 (2019).

Alghuwainem, Y. A. A. et al. Synthesis, DFT, biological and molecular Docking analysis of novel Manganese(II), Iron(III), Cobalt(II), Nickel(II), and Copper(II) chelate complexes ligated by 1-(4-Nitrophenylazo)-2-naphthol. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 23 (2022).

Chen, D. et al. The underlying regulatory mechanisms of colorectal carcinoma by combining vitexin and aspirin: based on systems biology, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, and in vitro study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1147132 (2023).

Badar, M. S., Shamsi, S., Ahmed, J. & Alam, M. A. Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Concept, Methods, and Applications, Transdisciplinarity, pp. 131–151. (2022).

Rezayi, S., S, R. N. K. & Saeedi, S. Effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence for Personalized Medicine in Neoplasms: A Systematic Review, Biomed. Res. Int., (2022) 7842566. (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Ajman University (grant agreement 2023-IRG-ENIT-1). The authors express their gratitude to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R132), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at University of Bisha for supporting this work through the Fast-Track Research Support Program. This research was supported by the International Collaborative Research Program (ICRP2023008), Internal Faculty/Staff Research Support Programs (IRSPC2024007) at Wenzhou Kean University, and Wenzhou Association for Science and Technology-Service and Technology Innovation Program (No. KJFW2024-054).

Funding

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R132), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written with the contributions of all authors. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arooj, M., Mateen, R.M., Javed, M. et al. Computational screening of phytochemicals targeting mutant KRAS in colorectal cancer. Sci Rep 15, 28754 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14229-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14229-z