Abstract

Northern China is an ecologically fragile region, making it highly significant for studying the temporal and spatial variations of vegetation cover and their driving factors. In this study, we analyze the temporal and spatial variations of vegetation cover in northern China from 2001 to 2022 by using a kernel normalized difference vegetation index (kNDVI) dataset, and quantify the contributions of influencing factors by random forest. The results indicate that the spatial distribution of kNDVI in northern China follows a pattern of “low in the west and high in the east,” with a gradual increase from west to east. The average kNDVI value for the study area is 0.144. Vegetation cover in northern China exhibits a fluctuating upward trend, with the northern Loess Plateau showing the highest rate of increase at 0.0032 per year and Southern Xinjiang and the Hexi Corridor showing the lowest rate of increase at 0.0003 per year. The average lag period of vegetation response to precipitation across different climate regions ranges from 0.5 to 2.2 months, while the average lag period for vegetation response to temperature ranges from 0.3 to 1.5 months. The response time of vegetation to precipitation is faster than that to temperature in the western arid zone, while in the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, vegetation responds more quickly to temperature than to precipitation. In the monsoon zone, the response times to precipitation and temperature are relatively similar. Precipitation is the dominant factor driving changes in vegetation cover, with an average contribution of 67.9%, although the contribution of kNDVI driving factors varies across different regions. This study provides valuable insights for guiding the restoration and sustainable development of ecosystems in northern China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vegetation is a critical component of Earth’s terrestrial ecosystems, playing a vital role in regulating the climate, protecting biodiversity, and supporting ecological material cycling and energy exchange1,2. Its growth is influenced not only by natural factors but also by human activities3. Therefore, understanding the spatial and temporal patterns of vegetation growth and their drivers is essential.

Advances in remote sensing have led to the development of numerous vegetation indices that enable the monitoring of vegetation dynamics, including the leaf area index (LAI), gross primary productivity (GPP), solar-induced fluorescence (SIF) and the enhanced vegetation index (EVI). Among these, the most widely used is the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), which quantitatively assesses regional vegetation cover and growth4,5. NDVI operates by using information from infrared and near-infrared bands to calculate photosynthesis, typically influenced by chlorophyll presence6, providing an accurate reflection of vegetation growth status. However, NDVI has notable limitations7,8: First, the relationship between NDVI and green biomass is nonlinear, leading to saturation in areas with dense vegetation. Second, synthesized NDVI products often contain significant noise, making them less effective in handling atmospheric interference. Third, the influence of tree crown background on vegetation indices has not been fully addressed. In 2021, CampsValls et al.9 introduced a new vegetation index, the kernel normalized difference vegetation index (kNDVI). This index applies a machine learning approach, leveraging kernel methods to capture all high-order differences between near-infrared and infrared reflection bands. As a result, kNDVI effectively addresses issues such as pixel saturation and mixed pixels commonly encountered with traditional indices. Compared to GPP, which relies on model interpolation, and SIF, which is constrained by instantaneous sampling limitations, offers distinct advantages due to its foundation in broadband remote sensing data. Specifically, kNDVI achieves both high spatial and temporal resolution, making it particularly suitable for monitoring rapid vegetation dynamics, such as crop rotation cycles in northern farmlands and phenological shifts in deciduous forests10,11. Unlike EVI, kNDVI can adapt to different land surface types without requiring parameter adjustments8. Additionally, while LAI retrievals are often compromised by cloud contamination, kNDVI provides a more robust representation of functional vegetation dynamics12. A key strength of kNDVI lies in its enhanced sensitivity to low-biomass vegetation in arid and semi-arid ecosystems13, while simultaneously maintaining high responsiveness in dense vegetation canopies—effectively overcoming the saturation issues that plague traditional NDVI in high-biomass regions14. These attributes collectively establish kNDVI as a superior vegetation metric for investigating vegetation dynamics across the complex and heterogeneous ecosystems of northern China.

Over the past century, global climate change has profoundly influenced terrestrial ecosystems15,16. Extensive research has demonstrated that climatic variables including precipitation, temperature, and radiation serve as key drivers of vegetation dynamics17,18, with these influences typically exhibiting temporal lags. At the global scale, Papagiannopoulou et al.19 established that vegetation changes are predominantly influenced by antecedent precipitation accumulation. Regionally, Wu et al.20 identified substantial variations in lagged responses among different vegetation types to identical climatic factors. Within China’s diverse ecosystems, Liu et al.21 revealed that the lag time of vegetation growth to extreme temperatures and precipitation can reach 1.7–3.3 months, while Jiang et al.22 found that the lag effect (≥1 month) in the Yellow River Basin contrasts sharply with the absence of a lag effect in the Sichuan Basin. However, conventional vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI/EVI) exhibit significant limitations in arid to semi-arid transition zones, where soil background interference and sparse vegetation cover often lead to substantial biases in lag effect estimation. Furthermore, these vegetation-climate lag effects demonstrate pronounced spatiotemporal heterogeneity across different scales23.

Northern China, situated in the mid-latitudes of East Asia, comprises arid, semiarid, and subhumid areas, accounting for approximately 34%, 27%, and 16% of its total area, respectively. In the context of global climate change, the region’s fragile ecological conditions and frequent drought events render its vegetation cover particularly sensitive to climatic variations24. The application of kernel NDVI (kNDVI) in this context offers distinct advantages for quantifying vegetation-climate lag effects, providing more reliable insights into the temporal dynamics of vegetation responses across northern China’s ecologically vulnerable areas. This paper analyzes the spatial and temporal characteristics of vegetation cover in northern China from 2001 to 2022 and analyzes its future development trends. It also explores the time-lagged responses of vegetation cover to precipitation and temperature changes, as well as the contributions of multiple driving factors to these changes. The findings of this study offer valuable insights and practical recommendations for the sustainable development, ecological protection, and restoration of vegetation cover in northern China.

Study area

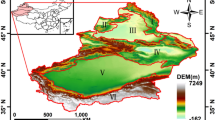

The study area encompasses northern China, defined as the region north of 35°N (Fig. 1). The eastern portion primarily consists of plains within the monsoon-affected zone, where the average annual precipitation exceeds 500 mm in most areas. The western part lies within the inland arid zone, characterized by deserts and the Gobi, with most areas receiving less than 200 mm of annual precipitation. The central region is marked by mountainous plateaus and serves as a transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, with average annual precipitation ranging between 200 and 500 mm. Precipitation and temperature exhibit significant regional variation across northern China. The station with the lowest average annual precipitation is Turpan Station in Xinjiang, recording just 15.5 mm, while the highest is Yanbian Station in Jilin, with 1038.6 mm. In terms of temperature, the coldest station is Yushu Station in Qinghai Province, with an average annual temperature of −7.4 °C, whereas Huaibei Station in Anhui Province is the warmest, at 15.8 °C. To compare the characteristics of kNDVI across different climate zones, eight representative regions within three climate zones were selected for analysis. The eight representative regions were mainly divided according to their climatic characteristics25, in which Northern Xinjiang (I), Southern Xinjiang (II), and the Hexi Corridor (III) representing the western arid zone; the northeastern slopes of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (IV), the northern Loess Plateau (V), and the western part of Northeast China (VIII) representing the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon; and the North China Plain (VI) and the eastern part of Northeast China (VII) representing the eastern monsoon zone (Table 1).

Study area. The red line indicates the division of climate zones: A represents the arid zone, B the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, and C the monsoon zone. The blue lines outline typical climatic regions: I for Northern Xinjiang, II for Southern Xinjiang, III for the Hexi Corridor, IV for the northeastern slopes of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, V for the northern Loess Plateau, VI for the North China Plain, VII for the eastern part of Northeast China, and VIII for the western part of Northeast China.

Data and methods

Datasets

We utilized the MOD13A3 dataset to obtain normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) data with a spatial resolution of 1 km and a temporal resolution of 1 month. The data were obtained via the Google Earth Engine platform, and NDVI values were calculated on a pixel-by-pixel basis. This process yielded 22 annual average kNDVI images for the growing season (April–October) from 2001 to 2022, as well as 264 monthly kNDVI images for the same period. The map data used in this paper is from the Science Data Platform of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (https://www.resdc.cn). The map processing was done using the ArcGIS 10.8.

Figure 2 shows the spatial distribution of the average values of different driving factors. Among these, the precipitation, temperature, radiation, and wind speed data were sourced from the 1-km monthly precipitation dataset for China, the 1-km monthly mean temperature dataset for China, and the China Meteorological Forcing Dataset available from the National Tibetan Plateau Scientific Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn), respectively. The precipitation and temperature datasets have a spatial resolution of 1 km, while the radiation and wind speed data have a spatial resolution of 10 km. All datasets span monthly intervals from 2001 to 2022 (Fig. 2a, b, c, d). The topographic data used in this study include elevation and slope degree (Fig. 2e, f). All topographic data were derived from a digital elevation model (DEM). The DEM data used in this study were obtained from the Science Data Platform of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (https://www.resdc.cn), with a spatial resolution of 1 km. Population density data were sourced from the WorldPop dataset (https://hub.worldpop.org/) at a spatial resolution of 1 km, covering the period from 2001 to 2022 (Fig. 2g). Soil moisture data were retrieved from the GLDAS Noah Land Surface Data Assimilation System (https://ldas.gsfc.nasa.gov/gldas). Monthly soil moisture data for depths of 0–10 cm, 10–40 cm, and 40–100 cm were selected for the years 2001–2022, with a spatial resolution of 25 km (Figs. 2h, i, j). The actual evapotranspiration (AET) data utilized the monthly data from the Global Land Evaporation Amalgamation (GLEAM) dataset (https://www.gleam.eu/) from 2001 to 2022, with a spatial resolution of 10 km (Fig. 2k). The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) was calculated using the potential evapotranspiration data from the GLEAM dataset and the monthly precipitation dataset from the National Tibetan Plateau Scientific Data Center (Fig. 2l), with a time scale of 6 months. The spatial distribution of the SPEI data is basically consistent with the research results of Wang et al.26 and Zhang et al.27. However, it should be noted that there is a problem of partial data missing in the northeastern part of the study area.

Distribution of average values for different drivers (a) Average annual precipitation, (b) average annual temperature, (c) average annual radiation, (d) wind speed, (e) altitude, (f) slope degree, (g) population density, (h) 0–10 cm soil moisture, (i) 10–40 cm soil moisture, (j) 40–100 cm soil moisture, (k) average annual AET, (l) average annual SPEI.

Analysis methodology

-

(1)

kNDVI

-

The kNDVI leverages spectral information by adopting a machine learning approach, using kernel analysis to linearize NDVI. This method effectively addresses the saturation problem and the delayed response of NDVI to photosynthesis9. The formula for calculating kNDVI is as follows9:

$$kNDVI = \tanh \left( {\left( {\frac{nir - red}{{2\sigma }}} \right)^{2} } \right)$$(1) -

where nir represents the near-infrared band, and red represents the red band. The parameter σ is a length-scale factor that can be adjusted to reflect the nonlinear sensitivity of NDVI to vegetation density. A reasonable choice for σ is the average of the near-infrared and infrared bands, calculated as follows:

$$\sigma = 0.5\left( {nir + red} \right)$$(2) -

The equation for kNDVI simplifies to9:

$$kNDVI = { }\tanh \left( {NDVI^{2} } \right)$$(3)

-

-

(2)

Sen’s slope

-

Sen’s slope is used to calculate the rate of change in the temporal trend of kNDVI28. Given a time series with n observations (x1, x2, … , xn), the Sen’s slope is calculated as

$$\beta = Median\left( {\frac{{x_{j} - x_{i} }}{j - i}} \right), \forall j > i$$(4) -

where Median() is the median function, and xi and xj are values from the time series at i and j, respectively. The value of β indicates the trend in the time series: β > 0 indicates that vegetation is greening; otherwise, it is browning. Considering that there is basically no region of β = 0, a threshold of β = ± 0.0005 is used to classify the trends29: β ≥ 0.0005 indicates that vegetation is greening, β ≤ − 0.0005 indicates that vegetation is browning, and − 0.0005 < β < 0.0005 indicates no change in vegetation.

-

-

(3)

Mann–Kendall testThe Mann–Kendall (M–K) test is employed to assess the trend changes of kNDVI over a time series30,31,32. Given a time series with n observations (x1, x2, …, xn), the distributions of xi and xj differ for all i, j ≤ n and i ≠ j. The test statistic is defined as

$$S = \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^{n - 1} \mathop \sum \limits_{j = i + 1}^{n} sgn\left( {x_{j} - x_{i} } \right){ }$$(5)-

where sgn() is the sign function:

$$sgn\left( {x_{j} - x_{i} } \right) = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {1, x_{j} - x_{i} > 0} \\ {0, x_{j} - x_{i} = 0} \\ { - 1, x_{j} - x_{i} < 0} \\ \end{array} } \right.{ }$$(6) -

When n > 10, the statistic S is approximately normally distributed, and the standard normal test statistic (Z) is calculated as follows:

$$Z = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\frac{s - 1}{{\sqrt {Var\left( S \right)} }} ,} & {S > 0} \\ {0,} & {S = 0} \\ {\frac{S + 1}{{\sqrt {Var\left( S \right)} }} ,} & {S < 0} \\ \end{array} } \right.$$(7)$$Var\left( S \right) = \frac{{n\left( {n - 1} \right)\left( {2n + 5} \right) - \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{m} t_{i} \left( {t_{i} - 1} \right)\left( {2t_{i} + 5} \right)}}{18}$$(8) -

where n is the length of the time series data, m is the number of repetitive data sets in the time series data, and t is the i-th set of repetitive data values. When |Z|> Z1-α/2, the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating a significant trend in the data. Conversely, when |Z|< Z1-α/2, the null hypothesis is accepted, implying no significant trend. At the 95% confidence level, the results of the M–K test are categorized as follows: significant changes: |Z|> 1.96; insignificant changes: |Z|≤ 1.96.

-

-

(4)

Stability analysis.

-

In this study, the coefficient of variation (Cv) of kNDVI is calculated at the pixel scale to assess vegetation stability over the time series33. The formula for Cv is as follows:

$$C_{V} = \frac{\sigma }{\mu }$$(9) -

where σ is the standard deviation of kNDVI, and μ is the average value of kNDVI.

-

A higher Cv indicates greater volatility in kNDVI, signifying greater interannual variation. Conversely, a lower Cv reflects reduced volatility, implying more stable interannual variation. The stability of kNDVI is categorized into five classes2: low volatility (Cv < 0.05), relatively low volatility (0.05 ≤ Cv < 0.1), moderate volatility (0.1 ≤ Cv < 0.15), relatively high volatility (0.15 ≤ Cv ≤ 0.2), and high volatility (Cv > 0.2).

-

-

(5)

Time-lagged partial correlation analysis.

-

In this study, pixel-by-pixel time-lagged partial correlation analysis is used to calculate the maximum time-lagged partial correlation coefficients and corresponding lag times between kNDVI and precipitation and temperature on a monthly scale from 2001 to 2022. Previous research has indicated that the lag time for vegetation responses to conventional meteorological factors (precipitation and temperature) typically does not exceed 3 months34,35. Therefore, this study considers lag times of 0–3 months for analyzing the relationship between kNDVI and these meteorological factors. The partial correlation coefficients between kNDVI and precipitation, as well as temperature, are calculated for the current month, the previous 1 month, the previous 2 months, and the previous 3 months. These four groups of partial correlation coefficients are then compared, and the maximum pixel value for each corresponding position is synthesized to determine the maximum partial correlation coefficient. This coefficient represents the highest correlation between vegetation and the climate factors, while the corresponding lag period indicates the time lag associated with the maximum correlation. The calculation process is as follows36:

-

First, the correlation coefficients between vegetation cover and temperature and precipitation are calculated at different time lags:

$$R_{kN\_T} = \frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{m = 1}^{c*n - k} \left( {T_{m} - \overline{{T_{m} }} } \right)\left( {kN_{m + k} - \overline{{kN_{m + k} }} } \right)}}{{\sqrt {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{m = 1}^{c*n - k} \left( {T_{m} - \overline{{T_{m} }} } \right)^{2} } \mathop \sum \nolimits_{m = 1}^{c*n - k} kN_{m + k} - \overline{{kN_{m + k} }}^{2} }}$$(16)$$R_{kN\_P} = \frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{c*n - k} \left( {P_{m} - \overline{{P_{m} }} } \right)\left( {kN_{m + k} - \overline{{kN_{m + k} }} } \right)}}{{\sqrt {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{m = 1}^{c*n - k} \left( {P_{m} - \overline{{P_{m} }} } \right)^{2} } \mathop \sum \nolimits_{m = 1}^{c*n - k} kN_{m + k} - \overline{{kN_{m + k} }}^{2} }}$$(17)$$R_{T\_P} = \frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{m = 1}^{c*n - k} \left( {T_{m} - \overline{{T_{m} }} } \right)\left( {P_{m + k} - \overline{{P_{m + k} }} } \right)}}{{\sqrt {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{m = 1}^{c*n - k} \left( {T_{m} - \overline{{T_{m} }} } \right)^{2} } \mathop \sum \nolimits_{m = 1}^{c*n - k} P_{m + k} - \overline{{P_{m + k} }}^{2} }}$$(18) -

where RkN_T and RkN_P are the correlation coefficients of the monthly average kNDVI with monthly average temperature and monthly precipitation at different time lags, respectively, and RT_P is the correlation coefficient between the monthly average temperature and monthly precipitation at different time lags. m is the length of the sequence. kNm is the monthly average kNDVI sequence. Tm and Pm are the monthly average temperature and monthly average precipitation sequences, respectively. k represents the lag time, with values of 1, 2, and 3. n is the number of years in the dataset, equal to 22. \(\overline{{T_{m} }}\) and \(\overline{{P_{m} }}\) are the mean values of the temperature and precipitation sequences, respectively. \(\overline{{kN_{m + k} }}\) and \(\overline{{P_{m + k} }}\) are the mean values of kNDVI and precipitation at the m+k-th time lag, respectively.

-

The correlation coefficients for different time delays are then used to compute the partial correlation sequences for different time lags as follows:

$$R_{kNT - P} = \frac{{R_{kN\_T} - R_{kN\_P} R_{T\_P} }}{{\sqrt {\left( {1 - R_{kN\_P}^{2} } \right)\left( {1 - R_{T\_P}^{2} } \right)} }}$$(19)$$R_{kNP - T} = \frac{{R_{kN\_P} - R_{kN\_T} R_{T\_P} }}{{\sqrt {\left( {1 - R_{kN\_T}^{2} } \right)\left( {1 - R_{T\_P}^{2} } \right)} }}$$(20) -

where RkNT-P is the partial correlation coefficient between kNDVI and temperature, excluding the effect of precipitation, at different time lags. RkNP-T is the partial correlation coefficient between kNDVI and precipitation at different time lags, excluding the effect of temperature. Finally, a t-test is conducted to assess the significance of the partial correlation coefficients.

-

-

(6)

Contribution of driving factors.

-

The Random Forest (RF) model is employed to analyze the contributions of driving factors to kNDVI37. RF is a robust algorithm capable of handling various types of predictor variables without requiring prior data transformation or outlier elimination. Each regression tree in the RF model is trained on a dataset generated by randomly selecting variables38. The RF algorithm evaluates the relative importance of input variables, calculated as follows39:

$$I_{x} = \mathop \sum \limits_{k = 1}^{K} \left[ {\frac{1}{K}\left( {MSE_{k}^{{x_{perm} }} - MSE_{k} } \right)} \right]$$(21) -

where Ix is the importance of variable x. K is the number of decision trees. \(MSE_{k}^{{x_{perm} }}\) is the estimation error for the k-th decision tree after the removal of the predicted value x. \(MSE_{k}\) is the prediction error of the k-th decision tree when all predictive factors are included. The larger the Ix, the stronger the correlation of variable x with the regression. The total importance of all variables sums to 1. In this study, 70% of the data are used as the training set, and the remaining 30% as the validation set. To enhance the accuracy of the results, the training process is repeated 10 times, with the averages taken, as the training datasets are randomly sampled for each iteration.

-

Results and analysis

Spatial and temporal characteristics of vegetation cover

From the perspective of spatial distribution of vegetation cover (Fig. 3), the distribution exhibits a clear spatial pattern, characterized by lower kNDVI values in the west, higher values in the east, and a gradual increase from west to east. The average value of the whole study area is 0.144. Areas with kNDVI values below 0.04 account for 44.10% of the total area, predominantly located in the western arid zone. Regions with kNDVI values between 0.04 and 0.20 constitute 20.73% of the total area and are mainly distributed in the northern part of the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon and the northwestern part of Xinjiang. Meanwhile, areas with kNDVI values ranging from 0.20 to 0.35 represent 21.41% of the total area, primarily concentrated in the North China Plain and the central part of Northeast China. Areas with kNDVI values exceeding 0.35 account for 13.75% of the total area, primarily distributed in Northeast China, the northern part of the North China Plain, and the lower reaches of the Yellow River. Overall, the spatial distribution of kNDVI in northern China is consistent with the bioclimatic zones40. The annual average kNDVI in different climate representative zones is significantly different (Fig. 4). In the monsoon zone and the western part of Northeast China, kNDVI values are relatively high and similar, with annual averages ranging from 0.231 to 0.301. In contrast, the annual average kNDVI in the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon shows considerable variation. The annual average kNDVI on the northeastern slopes of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau ranges from 0.178 to 0.244, with a multiyear average of 0.204. In the northern Loess Plateau, the annual average kNDVI falls between 0.059 and 0.139, with a multiyear average of 0.105. The western arid zone exhibits relatively low kNDVI values, with almost all annual averages below 0.05. Among these, Southern Xinjiang records the lowest annual average kNDVI, with a multiyear average of 0.013.

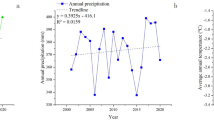

From the temporal change of vegetation cover (Fig. 5), the annual average kNDVI in northern China has generally shown a fluctuating upward trend over the past 22 years, but there are significant differences in interannual variations among different regions. The upward trend is more pronounced in the monsoon zone and the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, with an increase rate exceeding 0.0026 per year. Among the regions, the northern Loess Plateau (V) exhibits the highest upward rate of kNDVI (Fig. 5e), at 0.0032 per year, while the other regions in the monsoon and transition zones have similar rates of approximately 0.0027 per year. In contrast, the western arid zone shows a much smaller increase in the annual average kNDVI, with rates of 0.0003 per year in Southern Xinjiang (II) and the Hexi Corridor (III) and 0.0005 per year in Northern Xinjiang (I).

In addition, Sen’s trend analysis and the M–K test were employed to analyze the spatial variation characteristics of vegetation coverage during the growing season in northern China from 2001 to 2022. The vegetation change trends were classified into five categories (Table 2). By superimposing the results of each pixel, the distribution of vegetation change trends in the study area was obtained (Fig. 6). The analysis revealed that areas with improved vegetation cover accounted for 51.18% of the total area, while those with degraded vegetation cover constituted only 3.15%. The remaining areas were essentially stable, showing no significant change.

As shown in Fig. 6a, over the past 22 years, the area of vegetation improvement has been significantly larger than that of vegetation degradation in northern China, indicating an overall greening trend in vegetation cover. The kNDVI during the growing season is significantly better in the eastern part of northern China compared to the western region. The trend of kNDVI changes closely follows the northern edge of the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, with an increasing trend observed south of this boundary, while most areas north of the boundary remain stable. Significant differences in vegetation change trends are observed across different climate zones (Fig. 6b). In the western arid zone, over 70% of the areas are stable, with southern Xinjiang (II) and the Hexi Corridor (III) showing the highest stability (88.8% and 86.3%, respectively). Approximately 10% of these regions experienced significant improvement. Significant degraded areas in northern Xinjiang (I) account for 2.4%, and less than 0.5% in southern Xinjiang and Hexi Corridor. In contrast, over 60% of the eastern monsoon and transitional zones display significant vegetation improvement, particularly in the northern Loess Plateau (V) and eastern Northeast China (VII) (82.2% and 83.6%, respectively). However, the North China Plain (VI) has the highest proportion of severely degraded areas (5.5%). The proportion of slight improvement areas in eastern part of Northeast China (VII), northeast slope of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (IV) and North China Plain is higher (24.4%, 17.8%, 15.8%), and less than 10% in other areas.

Stability characteristics of the vegetation cover

The spatial distribution of the coefficient of variation (Cv) of kNDVI during the growing season from 2001 to 2022 (Fig. 7a) reveals significant spatial heterogeneity in vegetation cover fluctuations across northern China. Areas with high volatility in kNDVI variations account for 32.4% of the total area and are primarily located in most parts of the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon and the majority of the northwestern arid zone. Areas with relatively high and moderate volatility in kNDVI variations account for 33.0% of the total area and are mainly distributed in the North China Plain, the western Sanjiang Plain (south of the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon), the Qinghai Plateau, Xinjiang, and other parts of the western arid zone. Areas with low and relatively low volatility in kNDVI variations account for 34.6% of the total area. These regions are relatively concentrated, primarily in the western part of Northeast China, the Qilian Mountains, and desert areas within the northwestern arid zone. This distribution may result from the extremely high vegetation coverage in the former and the extremely low vegetation coverage in the latter. Fluctuations in kNDVI vary distinctly across different climate regions (Fig. 7b). The northern Loess Plateau (V) displays the most pronounced fluctuations, with 84.67% of its area classified as high variability and only 0.36% as low volatility. In contrast, eastern Northeast China (VII) shows the lowest volatility, where high-volatility areas account for just 8.18%, while 75.27% is moderate volatility. Northern Xinjiang (I) and the northeastern slopes of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (IV) show similar proportions of high volatility (43.37% and 47.93%, respectively), with low-volatility areas covering 1.72% and 4.93%, respectively. Similarly, Southern Xinjiang (II) and the Hexi Corridor (III) is relatively similar, with high-volatility areas at 28.35% and 25.99%, and low-volatility areas at 4.12% and 7.88%, respectively. In the North China Plain (VI) and the western part of Northeast China (VIII), high-volatility areas constituted 12.89% and 17.41%, respectively, while low-volatility areas accounts for 1.03% and 16.89%, respectively. In summary, vegetation cover fluctuation is most pronounced in the northern Loess Plateau, whereas eastern and western parts of Northeast China remain relatively stable.

Key driving factors of vegetation cover

Time-lagged partial correlation between kNDVI and climatic factors

Figure 8 illustrates the partial correlation coefficients, maximum partial correlation coefficients, and lag times of kNDVI in response to precipitation for the current month, 1 month prior, 2 months prior, and 3 months prior, from 2001 to 2022. Figure 8a, b, c and d reveal a clear lag effect in the response of kNDVI to precipitation across northern China, with notable regional differences in the duration of the lag time. The four groups of partial correlation coefficients are compared, and the maximum pixel values at corresponding positions are synthesized to determine the maximum partial correlation coefficient between kNDVI and precipitation (Fig. 8e). The results show a spatial pattern where the partial correlation coefficients are higher in the southeast and lower in the northwest. Specifically, areas with a maximum partial correlation coefficient greater than 0.6 are primarily located in the monsoon zone, most parts of the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, and near the Tianshan and Kunlun Mountains in Xinjiang, accounting for 35.24% of the total area. Areas with maximum partial correlation coefficients between 0.3 and 0.6 are primarily located in the Northeast Plain, central Inner Mongolia, central Gansu, and most parts of Qinghai, comprising 56.53% of the total area. Regions with maximum partial correlation coefficients below 0.3 are mainly found in the western arid zone, including the Tarim Basin, the Qaidam Basin, and northern Inner Mongolia, accounting for 8.23% of the total area. Areas with negative maximum partial correlation coefficients are predominantly distributed in the Qaidam Basin on the Qinghai Plateau and the northern and eastern parts of the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang, covering 1.07% of the total area.

From the lag time of kNDVI in response to precipitation shown in Fig. 8f, the average lag time across northern China is 1.1 months. Regions with the longest lag time exhibit a “belt-like” distribution, primarily concentrated in the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, with lag times of up to 3 months, accounting for 17.21% of the total area. Areas with a lag time of up to 2 months are mainly concentrated in the northern part of the Loess Plateau, covering 14.87% of the total area. Regions with a lag time of 1 month are more dispersed and are primarily found in the Tarim Basin, the northern slopes of the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang, the southwestern part of the Northeast Plain, and the southwestern side of the Loess Plateau, collectively accounting for 30.98% of the total area. Areas with a lag time of less than 1 month are primarily located in mountainous regions along major mountain ranges, including the Greater Khingan Mountains, Lesser Khingan Mountains, and Changbai Mountains in the northeast, as well as the Altai Mountains, Tianshan Mountains, Kunlun Mountains, and Qilian Mountains in the northwest. These regions account for 36.95% of the total area.

Figure 9 illustrates the partial correlation coefficients, maximum partial correlation coefficients, and lag times of kNDVI in response to temperature for the current month, 1 month prior, 2 months prior, and 3 months prior, from 2001 to 2022. Figure 9a, b, c and d demonstrate that the response of kNDVI to temperature in northern China exhibits a lag effect, with significant regional variations in lag time. From the maximum partial correlation coefficient between kNDVI and temperature (Fig. 9e), a clear distribution pattern is observed, with higher coefficients in the southeast and lower coefficients in the northwest. This pattern closely aligns with the spatial distribution of the correlation between kNDVI and precipitation. Areas with maximum partial correlation coefficients greater than 0.6 are primarily concentrated in the southwestern part of the Northeast Plain, accounting for 7.56% of the total area. Areas with maximum partial correlation coefficients between 0.3 and 0.6 are predominantly located in most parts of the monsoon zone and the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, accounting for 57.44% of the total area. Regions with maximum partial correlation coefficients between 0.1 and 0.3 are found in northern Gansu, western Inner Mongolia, southeastern Jilin, and western Xinjiang, covering 20.35% of the total area. Areas with maximum partial correlation coefficients between −0.1 and 0.1 are primarily distributed in the desert and Gobi regions of the northwestern arid zone, accounting for 6.72% of the total area. Areas with maximum partial correlation coefficients less than −0.1 are primarily located in the northeastern Junggar Basin, western Inner Mongolia, and parts of the southwestern Loess Plateau, accounting for 7.93% of the total area. Among these, regions with maximum partial correlation coefficients less than −0.3 constitute 2.84% of the total area and are mainly concentrated in parts of the southwestern Loess Plateau.

From the lag time between kNDVI and temperature (Fig. 9f), the average lag time in northern China is 0.9 months, with longer lag times observed in the northwest compared to the southeast. Areas with a lag time of 3 months are scattered across Xinjiang and parts of western Inner Mongolia, accounting for 12.06% of the total area. Regions with a lag time of 2 months are primarily located around the oases surrounding the Tarim Basin, parts of Northern Xinjiang, and western Inner Mongolia, covering 9.57% of the total area. Areas with a lag time of 1 month are located in the Northeast Plain, northern Inner Mongolia, the northern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, and the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang, accounting for 37.33% of the total area. Regions with a lag time of less than 1 month are primarily distributed in the monsoon zone and the southern portion of the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, covering 41.05% of the total area.

Figure 10 illustrates the partial correlation and time-lag effects of kNDVI with precipitation and temperature in typical representative regions. The correlation between kNDVI and precipitation is generally higher than that with temperature across different regions (Fig. 10a). The maximum partial correlation coefficients between kNDVI and precipitation, in descending order, are as follows: the eastern part of Northeast China, the western part of Northeast China, the North China Plain, the northern Loess Plateau, Northern Xinjiang, the northeastern slopes of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, the Hexi Corridor, and Southern Xinjiang. The maximum partial correlation coefficients between kNDVI and precipitation are all below 0.5 in Southern Xinjiang, the Hexi Corridor, and the northeastern slopes of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. The highest value is 0.64 in the eastern part of Northeast China, while the lowest is 0.38 in Southern Xinjiang. For kNDVI and temperature, the maximum partial correlation coefficients, in descending order, are as follows: the western part of Northeast China, the North China Plain, the northern Loess Plateau, the northeastern slopes of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the eastern part of Northeast China, Northern Xinjiang, the Hexi Corridor, and Southern Xinjiang. The maximum partial correlation coefficients between kNDVI and temperature are below 0.2 in Southern Xinjiang, the Hexi Corridor, and Northern Xinjiang. The highest value is 0.5 in the western part of Northeast China, while the lowest is 0.17 in Southern Xinjiang.

Regarding the lag periods in different regions (Fig. 10b), the average lag time of kNDVI in response to temperature is longer than its response to precipitation in the western arid zone. Conversely, in the monsoon zone and the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, the lag time for precipitation is longer than for temperature. The average lag time of kNDVI to precipitation across different regions ranges from 0.5 to 2.2 months, while the average lag time to temperature varies between 0.3 and 1.5 months. The average lag periods between kNDVI and precipitation across different regions, in descending order, are as follows: the northern Loess Plateau, the northeastern slopes of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, Southern Xinjiang, the Hexi Corridor, the western part of Northeast China, the North China Plain, the eastern part of Northeast China, and Northern Xinjiang. The lag times in the northern Loess Plateau and the northeastern slopes of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau are significantly longer than those in other regions, at 2.2 and 1.9 months, respectively. The lag period in Northern Xinjiang is the shortest, at 0.5 months. The average lag periods between kNDVI and temperature across different regions, in descending order, are as follows: the Hexi Corridor, Southern Xinjiang, Northern Xinjiang, the North China Plain, the eastern part of Northeast China, the northern Loess Plateau, the northeastern slopes of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, and the western part of Northeast China. The Hexi Corridor and Southern Xinjiang exhibit the longest average lag time, at 1.5 months, while the western part of Northeast China has the shortest, at 0.3 months.

In general, the response time of vegetation to precipitation in the western arid zone is faster than its response to temperature, indicating that vegetation in this region is more sensitive to precipitation. Conversely, in the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, vegetation responds more quickly to temperature than to precipitation, highlighting greater sensitivity to temperature. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in the northeastern slopes of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and the northern Loess Plateau. In the monsoon zone, the response times to precipitation and temperature are relatively similar, with an average lag time of approximately 0.7 months.

Contributions of different factors to kNDVI

The RF regression algorithm was used to quantitatively analyze the effects of various factors on kNDVI in the study area. These factors included precipitation (X1), temperature (X2), radiation (X3), altitude (X4), slope degree (X5), population density (X6), 0–10 cm soil moisture (X7), 10–40 cm soil moisture (X8), 40–100 cm soil moisture (X9), wind speed (X10), AET (X11), and SPEI (X12). First, the multiyear averages of the raster data for the driving factors were calculated. Each driving factor was gridded at resolutions of 10 × 10 km for the entire study area and 5 × 5 km for the typical areas. The multiyear average of kNDVI was also gridded to match these resolutions. Afterward, kNDVI was used as the dependent variable in the Random Forest model, while the 12 driving factors served as independent variables to assess their importance across different regions. To minimize sampling errors, the importance of each driving factor was calculated over 10 iterations, and the average of these calculations was taken as the final importance value. In this study, the average contribution of each factor was categorized into four classes: high (> 15%), medium (10–15%), low (5–10%), and very low (< 5%).

Vegetation dynamics are influenced by a complex interplay of climatic, topographic, and anthropogenic factors. Figure 11 illustrates the average contributions of the driving factors to kNDVI in northern China. Across the entire study area, precipitation (X1) emerges as the most significant driving factor, with an average contribution of 67.9%. AET (X11) is classified as a medium driving factor, contributing 10.9% on average. The remaining factors are classified as very low contributors, with population density (X6), radiation (X3), and temperature (X2) averaging 4.9%, 4.3%, and 3.9%, respectively, while the contributions of the other factors are all below 1.7%.

Figure 12 illustrates the average contributions of key driving factors across different regions of northern China, revealing distinct spatial patterns in their relative importance. In the western arid zone, the primary driving factors are precipitation (X1), temperature (X2), population density (X6), and 40–100 cm soil moisture (X9). Northern Xinjiang (I) exhibits strong dependence on precipitation (26.7%) and 40–100 cm soil moisture (15.9%), while Southern Xinjiang (II) is uniquely dominated by human activity, with population density (X6) contributing 53.9%. The Hexi Corridor (III) shows a balanced influence of precipitation (45.3%), temperature (16.9%), and population density (17.4%).In the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, precipitation remains crucial but is joined by other environmental factors. On the northeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (IV), precipitation (57.2%) and temperature (17.5%) dominate, whereas the northern Loess Plateau (V) shows more balanced contributions from precipitation (31.1%), radiation (21.5%), and altitude (20.4%). In the western part of Northeast China (VIII), temperature (42.0%) and slope degree (15.1%) are the primary drivers, while AET (11.7%) and precipitation (10.5%) were secondary drivers. Within the monsoon zone, the main driving factors of kNDVI are AET and population density. The North China Plain (VI) is influenced by AET (32.4%), population density (20.1%). In contrast, eastern Northeast China (VII) shows exceptionally strong control by AET (57.0%), with secondary contributions from population density (16.7%).

Average contribution of different factors to kNDVI in each representative region (a)–(h). X1–X12 represent precipitation, temperature, radiation, altitude, slope degree, population density, 0–10 cm soil moisture, 10–40 cm soil moisture, 40–100 cm soil moisture, and wind speed, AET, SPEI, respectively. Green indicates a contribution greater than 15%, blue represents contributions between 10 and 15%, purple represents contributions between 5 and 10%, and orange indicates contributions less than 5%.

In summary, precipitation is the most widely dominant factor, especially in arid and transitional regions, although its impact drops sharply in southern Xinjiang (4.0%). Second, AET exerts substantial influence in monsoon-affected zones, especially in eastern Northeast China. Third, as measured by population density, human activities have had a significant impact on some regions, especially southern Xinjiang, the North China Plain, eastern part of Northeast China, and the Hexi Corridor. Fourth, altitude contributes meaningfully in northern Xinjiang and the northern Loess Plateau. Finally, soil moisture plays a local but important role in arid areas, while other factors (e.g., wind speed) show negligible influence.

Discussion

The kNDVI exhibits a pronounced increasing trend across northern China, particularly in the eastern regions. These findings align well with previous studies utilizing NDVI, FVC, and other vegetation indices41,42. Compared to traditional vegetation indices, the kNDVI employed in this study offers significant advantages, including reduced saturation effects, enhanced sensitivity to vegetation dynamics, and improved robustness. These characteristics make kNDVI particularly well-suited for analyzing vegetation cover patterns across diverse ecosystems in northern China. This study used kNDVI to analyze vegetation cover changes in northern China. The northern edge of the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon serves as a boundary, with most areas in the northwestern region remaining stable, while vegetation cover in the southern region shows a gradual increasing trend. The southeastern region, particularly the Yellow River Basin, exhibits a significant upward trend. This improvement is likely due to China’s heightened efforts in ecological restoration in recent years. Initiatives such as the Three-North Shelterbelt Program and the Upper and Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River Protection Forest Project have significantly contributed to vegetation improvement in these areas32,43. Vegetation cover exhibits a significant increasing trend near the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang and in the oases surrounding the Tarim Basin, with further improvement expected in the future. This phenomenon is largely attributed to Xinjiang’s unique topography, where water vapor transported via the western route is blocked by the Tianshan Mountains, causing precipitation along the mountain slopes and resulting in high vegetation coverage. In the oases around the Tarim Basin in Southern Xinjiang, vegetation is primarily sustained by snowmelt from the Kunlun Mountains. With climate warming accelerating the melting of ice and snow, vegetation cover in these areas is expected to gradually continue improving. However, a notable degradation trend is observed in the North China Plain, likely due to ecological deterioration associated with the rapid urban expansion driven by economic growth over the past 20 years44. In addition, a significant degradation trend is observed in the Ili River Valley in Xinjiang. Studies have indicated that this degradation is largely attributed to substantial anthropogenic interference and overgrazing, which have led to grassland deterioration45.

Current scholarship demonstrates significant correlation between vegetation dynamics and climatic variables. Jin et al.46 established a significant positive correlation between vegetation coverage enhancement and climatic parameters, particularly growing season temperature elevation. Xu et al.47 found that temperature is the primary climatic factor affecting vegetation cover in China’s ecological function protection areas. Notably, Liu et al.48 reached the same conclusion in their study on the Qinghai Tibet Plateau. In this study, the research area will be refined according to climate characteristics, and the main influencing factors of vegetation cover in each climate zone will be accurately analyzed. The analysis results are somewhat inconsistent with previous studies. In general, precipitation is the primary driving factor in most regions, except for Southern Xinjiang, the Northeast China, and the North China Plain, where its contribution is less pronounced. In the rest of the regions, precipitation has a maximum average contribution of up to 57.3%, whereas in Southern Xinjiang and Northeast China, its contribution is less than 10.5%. Southern Xinjiang is primarily dominated by desert landscapes, with an average annual precipitation of less than 60 mm, which is insufficient to have a significant positive impact on vegetation. Whether during the growing season characterized by drought and low rainfall or in years with relatively higher precipitation, the desert thickets in the arid zone of Southern Xinjiang are primarily influenced by groundwater, rendering the impact of precipitation minimal49,50. Conversely, the eastern part of Northeast China and the North China Plain, located in the monsoon zone, receives abundant precipitation, with an average annual total exceeding 650 mm. Insufficient or excessive precipitation may be the primary factor causing precipitation to no longer serve as a major driver of vegetation growth in certain regions. However, actual evapotranspiration contributes over 30% in the monsoon zone. This is because in areas with high vegetation coverage (e.g., forests and farmlands), the leaf area index is large and the root system is well-developed, which can absorb and transpire more water. Vegetation cover directly governs spatial variation in evapotranspiration. The better the vegetation coverage, the stronger the evapotranspiration. Previous studies have also shown that vegetation greening increases evapotranspiration, whereas browning reduces it51,52. Population density also significantly influences vegetation cover. For instance, the average contribution of population density exceeds 16.6% in Southern Xinjiang, the Hexi Corridor, the North China Plain, and the eastern part of Northeast China, reaching as high as 53.9% in Southern Xinjiang.

Precipitation and temperature are the main driving factors for vegetation changes in northern China, but vegetation in different regions shows varying degrees of lag in response to both, with an average lag period of 0.5–2.2 months for precipitation and 0.3–1.5 months for temperature. The above results are more consistent with the research findings of He et al.53 and Yuan et al.54. In this study, it was found that vegetation in the northwestern arid zone responds more quickly to precipitation than to temperature. Conversely, in the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon and the monsoon zone, vegetation responds more slowly to precipitation than to temperature. This pattern is particularly pronounced in the northern part of the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon. The temporal effect of climate on vegetation varies depending on vegetation types and specific climatic factors55. Specifically, the same climatic factor exhibits varying time-lag effects on different vegetation types, while different climatic factors have distinct time effects on the same vegetation type. This variation may be influenced by the terrain of the vegetation distribution and the intrinsic characteristics of the vegetation itself. In northern China, precipitation generally decreases with increasing altitude, and temperature also declines. Vegetation in the northwest is predominantly composed of deserts and grasslands, where the root systems of herbaceous plants are primarily distributed in shallow soil layers56. In contrast, vegetation in the southeast is mainly forested. These significant differences in vegetation distribution contribute to varying response rates to precipitation and temperature.

This study considered only precipitation and temperature when analyzing the time-lagged partial correlation between climate factors and kNDVI. However, radiation, as the primary source of surface energy, is also a direct and critical climate factor influencing vegetation growth and development57. Future research should include a more comprehensive analysis of driving factors to provide a deeper understanding of vegetation dynamics. In the driver factor analysis, a 6-month time scale was selected for the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. A partial data deficiency was observed in the northeastern part of the study area, closely matching the extent of missing SPEI data provided in the Global SPEI database. Future research could further investigate the influence of higher-resolution drought indices and evapotranspiration data on vegetation dynamics.

Conclusions

We used the MOD13A3 dataset from 2001 to 2022 to calculate kNDVI and analyzed the spatial and temporal variation characteristics of vegetation cover, as well as the response characteristics of driving factors in northern China. The findings are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

The spatial distribution of kNDVI exhibits a pattern of low values in the west and high values in the east, with a gradual increase from west to east. During the growing season, the annual average kNDVI ranges from 0.001 to 0.706, with a mean value of 0.144 across the entire study area. Over the past 22 years, the annual average kNDVI has shown an increasing trend. Areas with significant improvement account for 41.75% of the total area, while those with slight improvement constitute 9.43%. Regions with relatively stable vegetation cover account for 45.67% of the total area, and areas with degraded vegetation cover represent only approximately 3%.

-

(2)

The time-lagged partial correlation analysis of precipitation and temperature with kNDVI reveals spatial heterogeneity in the lag periods of vegetation responses to these factors across different regions of northern China. The average lag period for precipitation ranges from 0.5 to 2.2 months, while the average lag period for temperature ranges from 0.3 to 1.5 months. Vegetation in the western arid zone responds more quickly to precipitation than to temperature. In contrast, in the transition zone influenced by the summer monsoon, vegetation responds faster to temperature than to precipitation. In the monsoon zone, the response times to precipitation and temperature are relatively similar.

-

(3)

Climate factors play a significant role in driving vegetation growth; however, vegetation conditions are influenced by multiple factors. In northern China, precipitation is the primary driver of vegetation cover changes, with an average contribution of 67.9%, followed by evapotranspiration, with an average contribution rate of 10.9%. Despite these general trends, the contributions of driving factors to kNDVI exhibit significant variation across different climatic regions.

Data availability

The data that supports the finding of this study will be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable academic request.

References

Verrall, B. & Pickering, C. M. Alpine vegetation in the context of climate change: A global review of past research and future directions. Sci. Total Environ. 748, 141344 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Changes in vegetation NDVI and its response to climate change and human activities in the Ferghana Basin from 1982 to 2015. Remote Sens. 16(7), 1296 (2024).

Zheng, K. et al. Impacts of climate change and anthropogenic activities on vegetation change: Evidence from typical areas in China. Ecol. Indic. 126, 107648 (2021).

Jamali, S., Seaquist, J., Eklundh, L. & Ardö, J. Automated mapping of vegetation trends with polynomials using NDVI imagery over the Sahel. Remote Sens. Environ. 141, 79–89 (2014).

Zhu, Y. et al. Responses of vegetation to climatic variations in the desert region of northern China. CATENA 175, 27–36 (2019).

Piao, S., Mohammat, A., Fang, J., Cai, Q. & Feng, J. NDVI-based increase in growth of temperate grasslands and its responses to climate changes in China. Glob. Environ. Change 16, 340–348 (2006).

Thenkabail, P. S., Smith, R. B. & Pauw, E. Hyperspectral vegetation indices and their relationships with agricultural crop characteristics. Remote Sens. Environ. 71, 158–182 (2000).

Huete, A. et al. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 83, 195–213 (2002).

Camps-Valls, G. et al. A unified vegetation index for quantifying the terrestrial biosphere. Sci. Adv. 7, eabc7447 (2021).

Duveiller, G. et al. A spatially downscaled sun-induced fluorescence global product for enhanced monitoring of vegetation productivity. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 12, 1101–1116 (2020).

Wen, J. et al. A framework for harmonizing multiple satellite instruments to generate a long-term global high spatial-resolution solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF). Remote Sens. Environ. 239, 111644 (2020).

Xiao, Z. et al. Use of general regression neural networks for generating the GLASS leaf area index product from time-series MODIS surface reflectance. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 52, 209–223 (2014).

Xu, M., Guo, B. & Zhang, R. A novel approach to detecting the salinization of the Yellow river delta using a kernel normalized difference vegetation index and a feature space model. Sustainability 16, 2560 (2024).

Gao, S. et al. Evaluating the saturation effect of vegetation indices in forests using 3D radiative transfer simulations and satellite observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 295, 113665 (2023).

Pascual, L. S. et al. Climate change-associated multifactorial stress combination: A present challenge for our ecosystems. J. Plant Physiol. 276, 153764 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. Water use efficiency-based assessment of risk to terrestrial ecosystems in China under global warming targets of 1.5 °C and 2.0 °C. Ecol. Indic. 143, 109349 (2022).

Gao, X. & Zhao, D. Impacts of climate change on vegetation phenology over the Great Lakes Region of Central Asia from 1982 to 2014. Sci. Total Environ. 845, 157227 (2022).

Meng, N., Wang, N., Cheng, H., Liu, X. & Niu, Z. Impacts of climate change and anthropogenic activities on the normalized difference vegetation index of desertified areas in northern China. J. Geogr. Sci. 33, 483–507 (2023).

Papagiannopoulou, C. et al. Vegetation anomalies caused by antecedent precipitation in most of the world. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 074016 (2017).

Wu, D. et al. Time-lag effects of global vegetation responses to climate change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 3520–3531 (2015).

Liu, M. et al. Time-lag and accumulation responses of vegetation growth to average and extreme precipitation and temperature events in China between 2001 and 2020. Sci. Total Environ. 945, 174084 (2024).

Jiang, W. et al. Impacts of drought and climatic factors on vegetation dynamics in the Yellow river basin and Yangtze River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 14, 930 (2022).

Kong, D., Miao, C., Wu, J., Zheng, H. & Wu, S. Time lag of vegetation growth on the Loess Plateau in response to climate factors: Estimation, distribution, and influence. Sci. Total Environ. 744, 140726 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Progress and prospect on climate warming and humidification in Northwest China (in Chinese). Ke Xue Tong Bao. 68, 1814–1828 (2023).

Liu, W. et al. Evaluation of reanalysis and LDAS soil moisture products over northern China (in Chinese). Trans. Atmos. Sci. 45, 616–629 (2022).

Wang, A., Chen, Y., Li, M., Gao, Y. & Ma, X. A review of soil moisture data in China: Definitions, sources, and applications in hydrometeorology research. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 106, 1108–1129 (2025).

Zhang, Q. et al. Discussion on major drought issues in the northern drought-prone belt in China. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 106, 678–706 (2025).

Sen, P. K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am Stat. Assoc. 63, 1379–1389 (1968).

Zhan, Y. et al. Spatial differentiation characteristics of vegetation greening rates and climate attribution in China’s arid and semi-arid regions. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 46, e02563 (2023).

Mann, H. B. Non-parametric tests against trend. Econometrica 13, 245 (1945).

Kendall, M. G. Rank correlation methods. Biometrika 44, 298 (1957).

Liu, W., Zhang, Q. & Fu, Z. Variation characteristics of precipitation and its affecting factors in Northwest China over the past 55 Years (in Chinese). Plateau Meteorol. 36, 1533–1545 (2017).

Ma, M., Wang, Q., Liu, R., Zhao, Y. & Zhang, D. Effects of climate change and human activities on vegetation coverage change in northern China considering extreme climate and time-lag and -accumulation effects. Sci. Total Environ. 860, 160527 (2023).

Chen, T., De Jeu, R. A. M., Liu, Y., Van der Werf, G. R. & Dolman, A. J. Using satellite based soil moisture to quantify the water driven variability in NDVI: A case study over mainland Australia. Remote Sens. Environ. 140, 330–338 (2014).

Ning, T., Liu, W., Lin, W. & Song, X. NDVI variation and its responses to climate change on the northern loess plateau of China from 1998 to 2012. Adv. Meteorol. 2015, 1–10 (2015).

Zhao, J. et al. Time-lagged response of vegetation dynamics to climatic and teleconnection factors. CATENA 189, 104474 (2020).

Li, H., Li, K., Zhao, X. & Zhao, J. Changes in vegetation greenness and their influencing factors in southern China. Remote Sens. 14, 3291 (2022).

Fratello, M. & Tagliaferri, R. Decision trees and random forests. Encycl. Bioinf. Comput. Biol. 1, 374–383 (2019).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Jiang, L., Liu, Y., Wu, S. & Yang, C. Analyzing ecological environment change and associated driving factors in China based on NDVI time series data. Ecol. Indic. 129, 107933 (2021).

Ma, M., Wang, Q., Liu, R., Zhao, Y. & Zhang, D. Effects of climate change and human activities on vegetation coverage change in northern China considering extreme climate and time-lag and -accumulation effects. Sci. Total Environ. 860, 160527 (2023).

Chen, M. et al. Assessing the effects of climate and human activity on vegetation change in Northern China. Environ. Res. 247, 118233 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Analysis of vegetation changes and dominant factors on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Sci Cold Arid Regions 11, 9 (2019).

Chang, J., Liu, Q., Wang, S. & Huang, C. Vegetation dynamics and their influencing factors in China from 1998 to 2019. Remote Sens. 14, 3390 (2022).

Sun, G., Li, W., Zhu, C., Cui, D. & Liu, H. Spatial-temporal characteristics of vegetation cover inIli River Valley from 2000 to 2015 (in Chinese). Arid Land Geogr. 43, 1551–1558 (2020).

Jin, J., Wang, Y., Jiang, H. & Cheng, M. Recent NDVI-based variation in growth of boreal intact forest landscapes and its correlation with climatic variables. Sustainability 8, 326 (2016).

Xu, G., Li, A., Xu, X., Yang, X. & Yang, Q. NDVI dynamics and driving climatic factors in the protected zones for ecological Functionsin China (in Chinese). Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 45, 00–00 (2021).

Liu, X., Du, G., Bi, H., Li, Z. & Zhang, X. Normal difference vegetation index simulation and driving analysis of the Tibetan Plateau based on deep learning algorithms. Forests 15, 137 (2024).

Wu, H., Bai, J., Li, J., Guli, J. & Bao, A. Study of spatio-temporal variation in fractional vegetation cover and its influencing factors in Xinjiang, China (in Chinese). Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 48, 41–55 (2024).

Zhou, H., Zhao, W. & Zhang, G. Varying water utilization of Haloxylon ammodendron plantations in a desert-oasis ecotone. Hydrol. Process. 31, 825 (2017).

Ma, Z. et al. Variation in actual evapotranspiration following changes in climate and vegetation cover during an ecological restoration period (2000–2015) in the Loess Plateau, China. Sci. Total Environ. 689, 534–545 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Recent trends in vegetation greenness in China significantly altered annual evapotranspiration and water yield. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 094010 (2016).

He, X., Liu, A., Tian, Z., Wu, L. & Zhou, G. Response of vegetation phenology to climate change on the Tibetan plateau considering time-lag and cumulative effects. Remote Sens. 16, 49 (2024).

Yuan, Y., Bao, A., Jiapaer, G., Jiang, L. & De Maeyer, P. Phenology-based seasonal terrestrial vegetation growth response to climate variability with consideration of cumulative effect and biological carryover. Sci. Total Environ. 817, 152805 (2022).

Ding, Y., Li, Z. & Peng, S. Global analysis of time-lag and -accumulation effects of climate on vegetation growth. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 92, 102179 (2020).

Zhang, X., Xing, Y., Yan, G. & Wang, Q. Response of fine roots to precipitation change: A meta-analysis. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 42, 164–172 (2018).

Jiang, H. et al. Determining the contributions of climate change and human activities to vegetation dynamics in agro-pastural transitional zone of northern China from 2000 to 2015. Sci. Total Environ. 718, 134871 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers for their positive feedback and efforts towards improving the manuscript and the China Scholarship Council (Grant 202305330017).

Funding

This work was funded by the Joint Research Project for Meteorological Capacity Improvement of China Meteorological Administrator under Grant (23NLTSZ001), Gansu Provincial Natural Science Foundation under grant (23JRRA1573), and Innovation team project of Gansu Meteorological Bureau under Grant (GXQXCXTD-2024–03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W. L. conceived the idea and designed the study. Z. X. performed the research, analyzed data and wrote the paper. H. L., S. Q., T. W. contributed with literature review and results analysis. All authors discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Z., Liu, W., Li, H. et al. Vegetation variations and driving mechanisms in northern China based on kNDVI. Sci Rep 15, 30094 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14232-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14232-4