Abstract

Falls are common during stroke rehabilitation, leading to physical injuries and psychosocial consequences. While prior studies have explored the association between falls and life satisfaction, the effect of fall-related injury severity remains unclear. This multicenter cross-sectional study included 6,068 stroke inpatients undergoing rehabilitation. Standardized face-to-face interviews were conducted to collect data on fall experiences within the past three months, severity of fall-related injuries, life satisfaction, and other demographic and clinical characteristics. Logistic regression models were used to analyze the relationships between fall experiences, injury severity, and life satisfaction. After adjusting for confounding factors such as age, sex, and activities of daily living, patients who had experienced a fall in the past three months exhibited significantly lower life satisfaction (OR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.61–0.98, P = 0.0325). However, no significant association was observed between the severity of fall-related injuries and life satisfaction (P > 0.05). These findings highlight the need for fall prevention and psychosocial support in stroke rehabilitation to improve well-being. Future research should explore the mechanisms linking fall-related injuries and life satisfaction to refine rehabilitation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is one of the leading causes of disability globally, profoundly affecting patients’ physical, psychological, and social well-being1,2. With advancements in medical technology, the survival rate of stroke patients has notably increased. However, disability and the decline in quality of life remain major challenges in the rehabilitation process3. Life satisfaction, a core indicator of overall health and quality of life, is generally defined as an individual’s subjective perception and overall evaluation of various life domains4. Several studies have indicated that life satisfaction is generally lower in stroke patients5with the extent of this decline influenced by sociodemographic factors such as gender, age, education level, and marital status6,7. Additionally, physical impairments-such as motor dysfunction, communication difficulties, and pain-as well as psychological factors like anxiety and depression, have been found to significantly reduce life satisfaction8,9.

Among the various factors influencing life satisfaction in stroke patients, falls have emerged as a critical yet often underrecognized factor10. Falls occur at all stages of stroke rehabilitation. During inpatient rehabilitation, the fall rate among stroke patients can reach up to 48%, while in community settings, this rate increases to 73%−80%11,12. The consequences of falls include fractures, traumatic brain injuries, and other soft tissue injuries, which often result in prolonged hospitalization, hindered rehabilitation progress, and substantial impacts on functional recovery13,14. Additionally, post-fall patients may face emotional instability, social isolation, and an elevated fear of falling, all of which can further impair their quality of life12.

A cross-sectional study utilizing data from the German Aging Survey identified a significant association between falls and reduced life satisfaction15. Similarly, a nationwide longitudinal study of 1,154 stroke patients aged 45 and older in China showed a significant negative correlation between falls and life satisfaction10. However, to date, no large-scale study has systematically examined the impact of fall severity on life satisfaction. Notably, previous studies have shown that post-stroke life satisfaction is shaped by multidimensional factors, including physical health, social participation, and psychosocial adaptation16,17all of which may be influenced to varying degrees by the severity of falls. Most prior studies have adopted a binary classification (fall vs. no fall), potentially masking the dose-response relationship between fall-related injury severity and life satisfaction.

Therefore, further research into the impact of fall-related injury severity on life satisfaction could contribute to a more comprehensive evaluation of stroke patients’ rehabilitation progress and provide valuable insights for the development of personalized rehabilitation strategies. This study aims to analyze the relationship between fall severity and life satisfaction in stroke inpatients, providing both theoretical support and practical guidance for optimizing rehabilitation plans and enhancing patients’ quality of life.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted within the framework of the clinical research project “The Promotion of Application Research of Longshi Scale,” which aimed to evaluate the nationwide applicability of the Longshi Scale (LS). Employing a convenience sampling method, participant data were obtained from rehabilitation departments in 103 hospitals across 23 provinces in China between December 2018 and May 2020. The study was designed and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) by the World Medical Association. The study was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (https://www.chictr.org.cn) (ChiCTR-2000034067) and was approved by the ethics committee of the Shenzhen Second People’s Hospital (No. 20180926006). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after they were fully informed about the study procedures.

Study participants

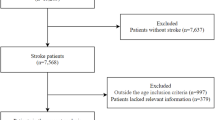

A total of 15,205 hospitalized patients were initially recruited, of whom 6,068 were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) A confirmed diagnosis of stroke according to the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) in the participating hospitals. (2) Age between 18 and 85 years. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Cognitive impairment, defined as a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≤ 24, which could hinder the completion of the questionnaire. (2) Concurrent participation in other ongoing studies.

Data collection

Data were collected via face-to-face interviews conducted by trained physicians, therapists, or nurses. The data were recorded and stored using the Quicker Recovery Line (QRL) platform, a rehabilitation evaluation and management system. In cases where potentially incorrect or unreasonable data records were identified, the data administrator verified the records with the assessor and corrected any errors based on the actual circumstances. For participants with communication impairments (e.g., aphasia), general information and fall incidents were reported by family members or caregivers with frequent or recent interactions.

Life satisfaction, as a unidimensional measure of individual quality of life, is widely utilized in large-scale national surveys in China18,19. In this study, life satisfaction was measured using a single question from the questionnaire: “How satisfied are you with your life right now?”20. Responses were rated on a 6-point Likert scale: 0 = Very dissatisfied, 1 = Dissatisfied, 2 = Slightly dissatisfied, 3 = Slightly satisfied, 4 = Satisfied, and 5 = Very satisfied. Following the approach used in the previous study10the responses were dichotomized into two categories: “<3: Not satisfied” and “≥3: Satisfied”.

Falls were defined as “an event in which a patient unintentionally and uncontrollably descends to a lower level, such as the ground”21. In this study, the occurrence of falls was assessed through a single item in the interview: “In the past 3 months, have you experienced a fall? If so, did the fall occur after your stroke? What were the consequences of the fall?” Fall consequences were classified into three categories: no injury; moderate injury (including bruises, abrasions, sprains, and minor lacerations); and severe injury (including fractures, joint dislocations, or lacerations requiring sutures)22.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Empower Stats and R software (2.0, X&Y Solutions, Inc, Boston, MA, USA). Descriptive statistics for categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. For continuous variables, means ± standard deviations (SD) were used for normally distributed data, while medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were used for skewed data. Group comparisons for continuous variables were performed using independent t-tests for normally distributed data with equal variance, and nonparametric tests, such as the Mann-Whitney U test, were applied for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for small sample sizes. Univariate analysis was conducted to identify risk factors associated with life satisfaction, while multivariate analysis (binary logistic regression) was used to explore the relationship between fall experiences, fall consequences, and life satisfaction. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients characteristics

A total of 6,068 participants were included in the analysis, with 2,214 (36.93%) female participants. Given the increasing incidence of stroke among younger adults in recent years, we included individuals aged 18 to 85 years to enhance the generalizability of our findings. Among all participants, 501 (8.3%) were aged 18–44 years, 1,542 (25.4%) were aged 45–59 years, and 4,025 (66.3%) were aged 60–85 years. The median age of participants was 66 years (interquartile range [Q1, Q3]: 55, 75). Of the participants, 4,066 (67.01%) reported being dissatisfied with their life satisfaction, while 2002 (32.99%) were satisfied. In terms of recent falls, 512 (8.44%) participants reported falling in the past three months, with a higher percentage of dissatisfied participants (9.20%) compared to satisfied participants (6.89%) (p < 0.001). Fall consequences were also examined: 93.05% of participants had no injury, 4.17% had moderate injury, and 2.79% had severe injury. A significant difference was observed between the groups (p = 0.015), with satisfied participants reporting fewer injuries compared to dissatisfied participants (Table 1).

Univariate results by binary logistic regression

The univariate binary logistic regression analysis revealed several significant factors associated with life satisfaction. Positive associations were observed with female, age, ischemic stroke, hyperlipidemia, higher family income, educational level, and higher self-reported health status (including fair, good, and very good health) (p < 0.05). In contrast, smoking, alcohol consumption, psychotropic substance use, and recent falls were negatively associated with life satisfaction (p < 0.05). Additionally, participants with severe injury (OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.46–0.94, p = 0.0201) resulting from falls exhibited lower odds of life satisfaction. No significant relationships were found for illness duration, hypertension, diabetes, kidney disease, heart disease, marital status, moderate injury, or residential status (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Multivariate results by binary logistic regression

The association between falls in the past 3 months and life satisfaction was evaluated using three models. In the crude model (without covariates), individuals who had fallen in the past 3 months had significantly lower odds of life satisfaction (OR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.60–0.90, p = 0.0025). In Model I, which adjusted for age and gender, the odds ratio remained significant (OR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.59–0.89, p = 0.0018). In Model II, which adjusted for all covariates presented in Table 1, the association was still significant (OR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.61–0.98, p = 0.0325) (Table 3; Fig. 2).

The results for the relationship between fall consequences and life satisfaction are shown in Table 3. In the crude model, neither moderate injury (OR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.51–1.18, p = 0.2365) nor severe injury (OR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.33–1.06, p = 0.0759) was significantly associated with life satisfaction. After adjusting for age and gender in Model I, and for all covariates in Model II, the associations remained non-significant (p > 0.05). These results suggest no significant link between the severity of fall consequences and life satisfaction (Table 3; Fig. 3).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we observed that a considerable proportion of stroke patients (67.01%) reported poor life satisfaction, highlighting the need for targeted interventions to support their psychological well-being. Our findings also indicated that a recent history (within the past 3 months) of falls was significantly associated with lower life satisfaction in stroke patients. However, among those with a history of falls, life satisfaction was not significantly correlated with the severity of fall-related injuries (none, moderate, or severe).

Stroke-related declines in life satisfaction are prevalent and clinically significant, with substantial implications for patient outcomes. Previous research by Hartman-Maeir et al.23 reported that one-year after stroke, 61% of patients expressed dissatisfied with their overall life. Similarly, Ekstrand et al.7 found that 47% of stroke patients with mild to moderate disability reported dissatisfaction with life as a whole. Consistent with these findings, our study demonstrated that 66.84% of participants with stroke reported poor life satisfaction, emphasizing the urgent need to address this issue in post-stroke care. Stroke patients often experience varying degrees of physical impairment, cognitive decline, and emotional challenges, all of which can contribute to diminished life satisfaction24. Specifically, mobility restrictions, communication difficulties, and impairments in independent living skills often lead to increased dependence on others in daily life, further diminishing life satisfaction19. Moreover, stroke survivors frequently experience psychological conditions such as depression and anxiety, which have been shown to be negatively associated with quality of life25. Given these complexities, investigating the multifaceted factors associated with life satisfaction in stroke patients and implementing targeted interventions are crucial for improving their overall well-being and clinical outcomes.

In this study, we found that hospitalized stroke patients with a history of falls exhibited significantly lower life satisfaction than those without falls. This may be closely related to both the physical injuries and psychological impact of falls. Falls can cause pain, restricted mobility, and prolonged bed rest, thereby diminishing patients’ independence26. Additionally, falls may induce anxiety and depression, further exacerbating the decline in life satisfaction. A longitudinal study conducted among middle-aged and older adults in Germany found that falls significantly decreased positive emotions in men while increasing negative emotions, ultimately diminishing their subjective well-being27.

Surprisingly, the severity of fall-related injuries is not significantly associated with life satisfaction. This finding challenges the common assumption that more severe injuries result in a greater decline in life satisfaction. One possible explanation is that life satisfaction is a multidimensional construct influenced by various factors, including physical health, psychological state, social support, and economic conditions10,28,29. Therefore, even when experiencing severe fall-related injuries, individuals with substantial resources in other domains (e.g., social support, financial security, and emotional resilience) may not experience a marked decrease in life satisfaction. This perspective is supported by a study conducted by Boccaccio et al.30which found that, among older adults with limitations in activities of daily living (ADL), 39% of those facing ADL difficulties and 28% of those dependent on ADL still reported high life satisfaction, a finding attributed to their social and economic well-being. Conversely, even when experiencing mild fall-related injuries, individuals’ subjective perceptions and emotional responses—such as fear of falling (FoF)—can still affect their quality of life31. A systematic review found that FoF in older adults was negatively associated with quality of life, and this association was independent of actual fall events, exerting a greater influence than the falls themselves32. Similarly, studies indicate that 32–66% of stroke survivors experience FoF33,34and its impact on ADL dependency may even exceed that of the fall itself and its associated injuries35. Patients with FoF often avoid falling by reducing physical activity and social interactions. However, this self-imposed limitation not only leads to functional decline and muscle atrophy but also increases the risk of future falls, ultimately diminishing quality of life36. Notably, all stroke inpatients in this study received comprehensive rehabilitation therapy. Post-stroke rehabilitation programs typically involve various interventions, such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and other functional training, as well as psychological support (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness training) and emotional regulation strategies. These multidisciplinary treatment approaches have been shown to effectively alleviate the psychological sequelae associated with falls37,38. Thus, establishing a structured rehabilitation environment may help mitigate the negative effects of falls on patients’ life satisfaction.

This study has significant clinical implications, highlighting the necessity of multidisciplinary interventions in rehabilitation, particularly in fall prevention and psychological support. In addition to addressing physical function and social participation, healthcare providers should also consider the psychosocial impact of falls. Integrating conventional rehabilitation with psychological interventions may help mitigate the negative effects of falls on life satisfaction. Furthermore, this study did not find a significant association between fall severity and life satisfaction. Therefore, clinicians, policymakers, and researchers should exercise caution in equating severe falls with lower life satisfaction, considering psychological resilience, social support, and subjective perceptions rather than focusing solely on the severity of physical injury.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examining the association between fall severity and life satisfaction among stroke inpatients, offering valuable insights into this relationship. However, several limitations should be considered. First, fall-related information was collected through self-report, which may introduce recall bias. Second, the cross-sectional design may limit the ability to establish a causal relationship between falls, the severity of fall-related injuries, and life satisfaction. Additionally, as all participants were recruited from a rehabilitation setting, the influence of medical interventions and psychological support could have affected the observed relationship between fall severity and life satisfaction. To ensure the reliability of self-reported data, patients with cognitive impairment were excluded. However, this group is also at increased risk of falls, and their exclusion may reduce the generalizability of our findings to the wider stroke population. Furthermore, the study did not collect detailed contextual information about the falls, including their location, timing, and frequency, which may limit our understanding of how these factors influence life satisfaction after stroke. Future longitudinal studies should incorporate additional variables, such as emotional status and social support, to clarify the long-term impact of falls on life satisfaction and the potential mediating mechanisms.

Conclusion

Our study found that a history of falls was associated with lower life satisfaction in hospitalized stroke patients, but fall severity was not. We recommend that healthcare professionals place particular emphasis on fall risk screening and education for stroke patients, as this could help prevent a potential decline in life satisfaction. Additionally, broader factors should be considered when evaluating the impact of fall on patients’ well-being.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, L., Lu, H. & Yang, C. Global, regional, and National burden of stroke from 1990 to 2019: A Temporal trend analysis based on the global burden of disease study 2019. Int. J. Stroke: Official J. Int. Stroke Soc. 19, 686–694. https://doi.org/10.1177/17474930241246955 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Corticomuscular coupling alterations during elbow isometric contraction correlated with clinical scores: an fNIRS-sEMG study in stroke survivors. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabilitation Engineering: Publication IEEE Eng. Med. Biology Soc. 33, 696–704. https://doi.org/10.1109/tnsre.2025.3535928 (2025).

Langhorne, P., Bernhardt, J. & Kwakkel, G. Stroke rehabilitation. Lancet (London England). 377, 1693–1702. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60325-5 (2011).

Pavot, W. & Diener, E. The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 3, 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946 (2008).

Ekstrand, E., Lexell, J. & Brogårdh, C. Test-retest reliability of the life satisfaction questionnaire (LiSat-11) and association between items in individuals with chronic stroke. J. Rehabil. Med. 50, 713–718. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2362 (2018).

Langhammer, B. et al. Life satisfaction in persons with severe stroke - A longitudinal report from the Sunnaas international network (SIN) stroke study. Eur. Stroke J. 2, 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396987317695140 (2017).

Ekstrand, E. & Brogårdh, C. Life satisfaction after stroke and the association with upper extremity disability, sociodemographics, and participation. PM R: J. Injury Function Rehabilitation. 14, 922–930. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12712 (2022).

Choi-Kwon, S. et al. Musculoskeletal and central pain at 1 year post-stroke: associated factors and impact on quality of life. Acta Neurol. Scand. 135, 419–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12617 (2017).

Oosterveer, D. M., Mishre, R. R., van Oort, A., Bodde, K. & Aerden, L. A. Depression is an independent determinant of life satisfaction early after stroke. J. Rehabil. Med. 49, 223–227. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2199 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Life satisfaction and its influencing factors of middle-aged and elderly stroke patients in china: a National cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 12, e059663. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059663 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Exploring the association between activities of daily living ability and injurious falls in older stroke patients with different activity ranges. Sci. Rep. 14, 19731. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70413-7 (2024).

Liu, T. W. & Ng, S. S. M. Assessing the fall risks of community-dwelling stroke survivors using the Short-form physiological profile assessment (S-PPA). PloS One. 14, e0216769. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216769 (2019).

Samuelsson, C. M., Hansson, P. O. & Persson, C. U. Early prediction of falls after stroke: a 12-month follow-up of 490 patients in the fall study of Gothenburg (FallsGOT). Clin. Rehabil. 33, 773–783. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215518819701 (2019).

Chen, N. et al. Identify the alteration of balance control and risk of falling in stroke survivors during obstacle crossing based on kinematic analysis. Front. Neurol. 10, 813. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00813 (2019).

Hajek, A. & König, H. H. Falls and subjective well-being. Results of the population-based German ageing survey. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 72, 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2017.06.010 (2017).

Bergström, A. L., von Koch, L., Andersson, M., Tham, K. & Eriksson, G. Participation in everyday life and life satisfaction in persons with stroke and their caregivers 3–6 months after onset. J. Rehabil. Med. 47, 508–515. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1964 (2015).

Gurková, E., Štureková, L., Mandysová, P. & Šaňák, D. Factors affecting the quality of life after ischemic stroke in young adults: a scoping review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 21 (4). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-023-02090-5 (2023).

Zhang, K., Pei, J., Wang, S., Rokpelnis, K. & Yu, X. Life satisfaction in china, 2010–2018: trends and unique determinants. Appl. Res. Qual. Life. 17, 2311–2348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-10031-x (2022).

Li, D., Zha, F. & Wang, Y. Life satisfaction after stroke and the associated factors across age groups in china: A cross-sectional study. Curr. Psychol. 43, 30726–30735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06469-5 (2024).

Boehm, J. K., Winning, A., Segerstrom, S. & Kubzansky, L. D. Variability modifies life satisfaction’s association with mortality risk in older adults. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615581491 (2015).

Ang, G. C., Low, S. L. & How, C. H. Approach to falls among the elderly in the community. Singapore Med. J. 61, 116–121. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2020029 (2020).

Burns, Z. et al. Classification of Injurious Fall Severity in Hospitalized Adults. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 75, e138-e144, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa004

Hartman-Maeir, A., Soroker, N., Ring, H., Avni, N. & Katz, N. Activities, participation and satisfaction one-year post stroke. Disabil. Rehabil. 29, 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280600924996 (2007).

Abualait, T. S., Alzahrani, M. A., Ibrahim, A. I., Bashir, S. & Abuoliat, Z. A. Determinants of life satisfaction among stroke survivors 1 year post stroke. Medicine 100, e25550. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000025550 (2021).

Minshall, C. et al. Exploring the impact of illness perceptions, Self-efficacy, coping strategies, and psychological distress on quality of life in a Post-stroke cohort. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. 28, 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09700-0 (2021).

Takemasa, S. et al. Factors affecting quality of life of the homebound elderly hemiparetic stroke patients. J. Phys. Therapy Sci. 26, 301–303. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.26.301 (2014).

Hajek, A. & König, H. H. The onset of falls reduces subjective Well-Being. Findings of a nationally representative longitudinal study. Front. Psychiatry. 12, 599905. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.599905 (2021).

Boosman, H., Schepers, V. P., Post, M. W. & Visser-Meily, J. M. Social activity contributes independently to life satisfaction three years post stroke. Clin. Rehabil. 25, 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215510388314 (2011).

Abruquah, L. A., Yin, X. & Ding, Y. Old age support in urban china: the role of pension schemes, Self-Support ability and intergenerational assistance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16111918 (2019).

Boccaccio, D. E., Cenzer, I. & Covinsky, K. E. Life satisfaction among older adults with impairment in activities of daily living. Age Ageing. 50, 2047–2054. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab172 (2021).

Lee, E. S. & Kim, B. The impact of fear of falling on health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults: mediating effects of depression and moderated mediation effects of physical activity. BMC Public. Health. 24, 2459. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19802-1 (2024).

Schoene, D. et al. A systematic review on the influence of fear of falling on quality of life in older people: is there a role for falls? Clin. Interv. Aging. 14, 701–719. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.S197857 (2019).

Schmid, A. A. et al. Fear of falling in people with chronic stroke. Am. J. Occup. Therapy: Official Publication Am. Occup. Therapy Association. 69, 6903350020. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.016253 (2015).

Schmid, A. A. et al. Fear of falling among people who have sustained a stroke: a 6-month longitudinal pilot study. Am. J. Occup. Therapy: Official Publication Am. Occup. Therapy Association. 65, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2011.000737 (2011).

Pereira, C. et al. Risk for physical dependence in community-dwelling older adults: the role of fear of falling, falls and fall-related injuries. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 15, e12310. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12310 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Relationship between fear of falling and fall risk among older patients with stroke: a structural equation modeling. BMC Geriatr. 23, 647. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04298-y (2023).

Liu, T. W., Ng, G. Y. F., Chung, R. C. K. & Ng, S. S. M. Decreasing fear of falling in chronic stroke survivors through cognitive behavior therapy and Task-Oriented training. Stroke 50, 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.118.022406 (2019).

Jung, Y., Lee, K., Shin, S. & Lee, W. Effects of a multifactorial fall prevention program on balance, gait, and fear of falling in post-stroke inpatients. J. Phys. Therapy Sci. 27, 1865–1868. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.27.1865 (2015).

Funding

This study was supported by Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (C2401013), and the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (grant number SZSM202111010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.H.L., J.J.L. and Y.L.W. contributed to the conception and design of the study, supervised the surveys and edited the manuscript. Q.F.Z., J.Y. and X.L. coordinated the data collection and conducted the statistical analyses. W.S.C. and M.L.C. provided methodological input. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Zhang, Q., Yan, J. et al. Association between life satisfaction and fall severity among hospitalized stroke patients. Sci Rep 15, 29594 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14246-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14246-y