Abstract

Effective financial risk management in healthcare systems requires intelligent decision-making that balances treatment quality with cost efficiency. This paper proposes a novel hybrid framework that integrates reinforcement learning (RL) with knowledge graph-augmented neural networks to optimize billing decisions while preserving diagnostic accuracy. Patient profiles are encoded using a combination of structured features, deep latent representations, and semantic embeddings derived from a domain-specific knowledge graph. These enriched state vectors are used by an RL agent trained using Deep Q-Networks (DQN) or Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) to recommend billing strategies that maximize long-term reward, reflecting both financial savings and clinical validity. Experimental results on real and synthetic healthcare datasets demonstrate that the proposed model outperforms traditional regressors, deep neural networks, and standalone RL agents across multiple evaluation metrics, including cost prediction error, diagnostic classification accuracy, cumulative reward, and average billing reduction. An ablation study confirms the complementary contributions of each architectural component. This work highlights the value of combining data-driven learning with structured medical knowledge to enable context-aware, cost-efficient decision-making in complex healthcare environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing financial burden on global healthcare systems has made cost optimization and risk-aware decision-making essential to modern medical practice. Rising treatment complexity, aging populations, and fragmented billing systems have contributed to a healthcare environment where clinical decisions must also consider economic sustainability. As data-driven technologies mature, artificial intelligence (AI) offers new tools to analyze large-scale healthcare data, detect inefficiencies, and guide resource allocation. While predictive analytics has been widely explored in diagnostics and patient monitoring, its integration into financial decision-making remains underdeveloped. One of the primary subsets of machine learning (ML), reinforcement learning (RL)1, has transformed artificial intelligence by enabling agents to interact with their surroundings and learn from them in order to perform better. Financial applications such as trade work, portfolio management, and market making can benefit from RL algorithms’ ability to learn and adapt to changing conditions. In contrast to traditional models that rely on statistical techniques and econometric methods like time series models [such as autoregressive moving average (ARMA), autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA)], factor models, and panel models, the RL framework allows agents to learn decision-making by interacting with an environment and inferring the consequences of previous actions to maximize cumulative rewards2. Lăzăroiu et al.3 reviewed the impact of deep and machine learning algorithms on COVID-19 prediction and hospital management, using a variety of clinical datasets including imaging and biomarker data and multiple systematic review tools like AMSTAR and DistillerSR for methodology quality control. While they identify a gap in aligning financial optimization methods with clinical outcomes, their research shows that machine learning improves ICU resource distribution, mortality risk forecasting, and operational productivity. After conducting a narrative analysis of 94 studies, Sepetis et al.4 proposed a sustainable healthcare model that integrates digital transformation efforts with ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) factors. They found that there is no unified framework in healthcare that combines digital metrics with ESG considerations. The main difference between them is the absence of mutual, standardized evaluation tools to assess digital performance and ESG collectively in healthcare resilience initiatives. Utilizing a Kaggle health insurance dataset enriched with engineered features such as the Age-to-Health Risk Ratio and the Health Risk Index, Srinivasagopalan5 introduced a Deep Q-Learning-based reinforcement learning approach for adjusting healthcare insurance premium pricing dynamically. Achieving 96.8% accuracy and improving both fairness and profitability, the method overcame static modeling limitations, yet the research notes a gap in real-world deployment, as dynamic RL-based systems require constant access to live healthcare and insurance data, which can be difficult in practice.

Existing cost prediction systems in healthcare are predominantly static and regression-based, failing to model the dynamic, sequential nature of clinical and financial decision-making. These models lack contextual awareness, do not incorporate structured domain knowledge, and struggle to balance competing priorities such as cost, risk, and treatment quality. Consequently, they are ill-suited for supporting adaptive, patient-specific billing and resource allocation strategies in real-world healthcare settings.

This paper addresses these limitations by proposing a hybrid AI framework that combines reinforcement learning with knowledge graph-enhanced neural networks to optimize financial risk in healthcare systems. The primary objective is to develop a model that learns cost-effective decision policies while preserving diagnostic reliability, leveraging both data-driven feature learning and semantic medical knowledge. The motivation stems from the need for adaptable, interpretable, and high-performance solutions that can bridge clinical logic and predictive intelligence.

While reinforcement learning offers adaptability for sequential decision-making and knowledge graphs provide structured semantic reasoning, these two paradigms are rarely unified in healthcare finance. Our framework introduces a theoretically grounded integration where the knowledge graph acts as a semantic regularizer that guides the reinforcement learning policy, enabling it to make contextually valid and medically plausible decisions. This contrasts with standard RL agents that rely only on numeric or tabular inputs, which often miss important clinical relationships (comorbidities, treatment dependencies). By embedding medical knowledge directly into the RL state space through relational graph convolutions, the agent can generalize better in data-sparse settings and learn more ethically aligned policies, particularly when patient safety is a competing objective. This novel combination of graph-based semantics with dynamic policy optimization directly addresses the core limitations of prior cost-prediction approaches, which are static, non-adaptive, and context-agnostic. The significance of this research lies in its dual contribution to machine learning and healthcare informatics. From a technical perspective, the model demonstrates how reinforcement learning can be extended with structured graph representations to make more context-sensitive decisions. From a healthcare viewpoint, the proposed framework provides a scalable, patient-specific mechanism for billing optimization, capable of aligning hospital objectives with patient safety and outcome fairness.

To achieve this, we model patient cases as enriched state vectors combining structured features, deep latent embeddings, and graph-derived medical knowledge. These states are used by a reinforcement learning agent—trained via either Deep Q-Learning or Proximal Policy Optimization—to recommend billing decisions that maximize long-term reward. The knowledge graph, constructed from clinical relationships among diagnoses, treatments, and test results, is encoded using a Relational Graph Convolutional Network and integrated into the policy network as a semantic prior. The framework is evaluated on multiple real and synthetic datasets to measure cost prediction accuracy, diagnostic outcome retention, and billing efficiency. Overall, the key contributions of this work are as follows:

-

We propose a novel hybrid framework that integrates reinforcement learning with structured domain knowledge through a knowledge graph, enabling cost-aware and semantically-informed decision-making in healthcare systems.

-

We design a unified state representation that combines structured features, VAE-based latent embeddings, categorical encodings, and R-GCN-derived semantic vectors, significantly improving both financial prediction accuracy and diagnostic classification performance.

-

We conduct extensive empirical validation using real and synthetic healthcare datasets, demonstrating the model’s superiority over conventional regressors, standalone deep models, and non-knowledge-guided reinforcement learning approaches across multiple evaluation metrics.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews relevant literature in cost prediction, healthcare AI, and reinforcement learning. Section 3 outlines the proposed hybrid architecture in detail, including data preprocessing, knowledge graph design, and policy learning. Section 4 presents experimental results and comparisons with baseline models. Section 5 presents the discussion of implications, limitations, and directions for future research. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

Related work

This section reviews prior work in four key areas relevant to this research: healthcare cost prediction, reinforcement learning in medical decision-making, knowledge graphs in clinical informatics, and hybrid AI architectures combining symbolic reasoning with deep learning. Recent advances in interpretable deep learning have shown promise in clinical diagnostics. As an example, DeepXplainer6 applied explainable AI to lung cancer detection, while fusion-based models have improved interpretability in breast cancer7 and cardiac disease prediction tasks8. Although these works focus on disease classification rather than policy optimization, they highlight the growing importance of transparency in healthcare AI, which aligns with our future plans to integrate explainability into reinforcement learning decisions.

Cost prediction models in healthcare have traditionally relied on statistical techniques such as linear regression, generalized linear models, and decision trees. These models typically operate on structured patient data, including demographic information, medical history, insurance details, and service utilization. While interpretable and computationally efficient, such models often lack the capacity to capture complex, non-linear relationships and interactions between features. More recent approaches have employed deep learning methods, particularly feedforward neural networks, to improve predictive performance. However, these methods still treat cost estimation as a static task and do not consider sequential dependencies or adaptive policy formulation. Zaidi et al.9 introduced HeartEnsembleNet, a hybrid ensemble approach that combines various machine learning classifiers such as SVM, Random Forest, and Gradient Boosting for predicting the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), utilizing a Kaggle dataset with 70,000 patient records encompassing 12 clinical features. Their model attained an accuracy of 92.95% and a precision rate of 93.08%, surpassing traditional methods and other ensemble strategies like stacking and voting. However, their study revealed a shortcoming in the inclusion of essential clinical indicators such as ECG readings and biomarkers, which limits the potential for deeper physiological understanding. In another study, Abdullah et al.10 created several comparative machine learning models, including SVM, Decision Trees, Logistic Regression, and Random Forest, applied to five different healthcare datasets (cancer, diabetes, diabetic retina, heart disease, and general diabetes data from electronic health records). They achieved remarkable results, especially a 97.33% accuracy for diabetes prediction using SVM and Decision Trees, while stressing the importance of incorporating precision medicine into disease forecasting. Yet, their research acknowledged ongoing issues such as privacy risks, algorithmic bias, and a lack of applicability across various healthcare settings. Lastly, Lin et al.11 employed Decision Tree and Logistic Regression models to forecast hospital revisits for patients on peritoneal dialysis, utilizing 1,373 records from a single-center electronic medical record dataset. Their models displayed moderate performance, with the Decision Tree model exceeding Logistic Regression for 14-day readmission prediction (AUC = 79.4%). A major limitation of their research was the absence of external validation and a small sample size, raising concerns regarding the applicability of their results.

Reinforcement learning (RL)12 has gained attention in healthcare for its ability to learn sequential decision policies in uncertain environments. Applications include treatment planning, resource allocation, and clinical scheduling. In these contexts, RL agents learn to maximize a reward function that typically balances clinical efficacy and operational efficiency. Despite its promise, most existing work either focuses solely on clinical outcomes or lacks integration with financial optimization objectives. Furthermore, RL models often rely on flat feature vectors, which limits their ability to incorporate structured or relational knowledge critical in medical domains. Recent developments have investigated the combination of reinforcement learning (RL) and knowledge-driven approaches to enhance healthcare systems while managing resource and data limitations. Baccour et al.13 presented an innovative framework that merges dynamic pruning with explainable AI (XAI)14 to facilitate efficient distributed inference in healthcare IoT ecosystems. Their technique utilizes Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP)15 to direct online pruning without necessitating retraining, tackling the crucial issue of limited and biased healthcare data. By conceptualizing the problem through Non-Linear Programming (NLP) and optimizing decisions using a reinforcement learning-based policy (Proximal Policy Optimization, PPO), they showcased considerable enhancements in resource efficiency and model adaptability, employing real-world healthcare imaging datasets. The authors pointed out a gap in previous research that generally presumed the availability of retraining and failed to respond to dynamic, resource-constrained healthcare settings. Yang et al.16 introduced an imbalanced classification framework that employs a dueling double deep Q-learning network (D-DDQN) specifically designed for extremely unbalanced multi-class clinical datasets. Their approach, validated using COVID-19 emergency department electronic health records (EHR) and ICU patient diagnosis data, surpassed existing techniques by creating a customized reward function prioritizing minority classes. This method addressed significant flaws in earlier reinforcement learning models that inadequately dealt with high imbalance ratios or were restricted to binary classification scenarios. By framing classification tasks as sequential decision-making processes within a Markov Decision Process (MDP) framework, they improved sensitivity for minority classes without compromising accuracy for majority classes. In another paper, Wu et al.17 thoroughly reviewed reinforcement learning applications in healthcare operations management (HOM). They outlined the function of RL in optimizing patient flow, distributing medical resources, and enhancing healthcare delivery processes, stressing the effectiveness of Approximate Dynamic Programming (ADP)18 and model-free RL techniques in overcoming the scalability issues prevalent in traditional optimization approaches. Their review emphasized existing gaps, particularly the absence of scalable, real-time RL frameworks capable of addressing uncertainty and the operational intricacies of healthcare systems. They proposed future research directions that involve a deeper integration of model-based reinforcement learning with deep neural approximators.

Knowledge graphs (KGs)19 offer a structured way to represent relationships among clinical concepts such as diseases, symptoms, medications, and diagnostic tests. By encoding domain knowledge as a graph of entities and relations, KGs enable AI models to reason about medical semantics beyond raw data. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)20, and in particular Relational Graph Convolutional Networks (R-GCNs)21, have been effective in embedding these structures into trainable neural models. Prior research has used KGs for drug discovery, patient similarity analysis, and clinical outcome prediction, but their integration into cost-aware decision-making pipelines remains largely unexplored. Recently, some papers, Gao et al.22 created HealthGenie, an interactive diet advising system that blends knowledge graphs (KGs) with large language models (LLMs), using simulated dietary scenarios. They found that utilizing visual knowledge graph interfaces made it much simpler for users to understand and think less than using conventional text suggestions from LLMs. This shows that previous methods neglected the advantages of interactive elements and clear graphics. BioLORD-2023, a biomedical semantic model, was introduced by Remy et al.23. It was trained by combining clinical knowledge graphs (SNOMED-CT, UMLS) with LLM-generated definitions applying enhanced contrastive learning, self-distillation, and multilingual distillation approaches. For tasks like biomedical entity linking and semantic textual similarity (STS) on more than 15 biomedical datasets, their results showed significant gains over earlier models. However, they also found a gap in finding a balance between domain expertise and general language skills, especially in situations with multiple languages. Rad et al.24 suggested a real-time personalized diabetes management system that combined HL7-compliant data from several patient sources using digital twins generated from personal health knowledge graphs (PHKGs). Although the authors highlighted that previous systems were unable to dynamically react to changing patient data or include patient self-acquired knowledge into decision-making, the system demonstrated features like insulin optimization, lifestyle suggestion, and glucose prediction.

Hybrid AI systems that combine symbolic reasoning with neural networks aim to bridge the gap between structured knowledge and statistical learning25. These models leverage the expressiveness of deep learning while grounding decisions in human-interpretable logic or ontologies. In healthcare, such integration can enhance transparency, support regulatory compliance, and improve generalization across data sources. Despite emerging interest in this area, few models have demonstrated successful application in domains requiring both clinical reasoning and economic optimization. This paper contributes to this growing body of work by introducing a hybrid RL framework that incorporates knowledge graph embeddings into the state representation, enabling both semantic awareness and adaptive policy learning. Several innovative methods for anomaly detection and security in smart healthcare and Internet of Things systems that include deep learning, hybrid models, and privacy-preserving structures. Using multimodal healthcare data from 10,000 patients, Nagamani and Kumar26 proposed a hybrid CNN-LSTM model with federated learning for real-time healthcare anomaly detection. Their work addressed the weaknesses of previous unimodal approaches and improved scalability and privacy via Apache Kafka and differential privacy, but it also identified the need for more flexible transformer-based multimodal integration. The model achieved a 94% detection accuracy with an F1-score of 0.92. Using the Edge-IIoTset cybersecurity dataset, Ahmad and Qamar27 presented an Embedded Hybrid Deep Learning (EHID) intrusion detection system for IoT devices connected via satellite to HPC clouds. They were able to overcome the challenges of limited device resources and computational cost while improving the detection of 14 different types of attacks. However, they also identified an error in their ability to handle real-world satellite-IoT traffic more effectively in restricted environments. Using time-series data from the MIMIC-II database, Xiao et al.28 developed a hybrid model that combines ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD), a three-layer deep autoencoder, and multiple gene expression programming classifiers to predict acute hypotensive episodes (AHE) in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. The model’s prediction accuracy was 86.16%, but it highlighted the difficulty of gathering meaningful features from extremely complex physiological signals, indicating the need for further advancements in feature extraction for better real-time clinical use. Djaafari et al.29 proposed a hybrid LSTM-BDSCA model for predicting hourly solar irradiation in Algeria, achieving high accuracy (RRMSE< 2.1%). Their work focuses on time-series forecasting using deep learning and metaheuristic optimization, whereas our paper targets dynamic financial risk optimization in healthcare using reinforcement learning and knowledge graphs. Our method addresses dynamic decision-making under uncertainty rather than static prediction and integrates semantic knowledge to enhance model interpretability and policy optimization. Khaled et al.30 used Random Forest and other regressors to predict groundwater resources in India based on a 2017 dataset covering 689 districts, with Random Forest showing the best performance. Unlike their static prediction models, our approach focuses on adaptive decision-making under uncertainty in financial healthcare systems. While both studies employ machine learning, our approach uniquely combines reinforcement learning and knowledge graphs to model evolving financial risk and support strategic decision-making in critical healthcare contexts.

Methodology

This section presents the architecture, learning framework, and overall workflow of the proposed hybrid reinforcement learning and knowledge graph-based system for financial risk optimization in healthcare systems. We describe the proposed methodology, training and implementation details, and summarize the workflow as a Fig. 1.

Data preprocessing

To enable effective training of our hybrid reinforcement learning and knowledge graph framework, we applied advanced preprocessing techniques to two distinct datasets: the US Health Insurance Dataset and a synthetic Healthcare Classification Dataset. The primary goals of preprocessing were to normalize heterogeneous data types, extract semantic features, and generate structured input for reinforcement learning and graph-based modules. We detail each stage below.

Data cleaning and normalization

We began by addressing inconsistencies and missing values. As both datasets were complete, no imputation was required. All categorical variables were standardized males and females were unified. Continuous features such as age, BMI, and charges were normalized using min-max scaling:

This transformation ensures that all input features reside within the range [0, 1], facilitating convergence in gradient-based optimization.

Categorical embedding with deep learning

Categorical attributes such as region, insurance provider, admission type, and medical condition were embedded using trainable entity embeddings. Given a categorical variable \(c \in {\mathscr {C}}\) with cardinality \(|{\mathscr {C}}|\), we define its embedding as:

We used \(d = \lfloor |{\mathscr {C}}|^{0.25} \rfloor\) as a heuristic for embedding dimension. These embeddings were jointly optimized with downstream learning tasks and served as inputs to both the neural policy network and the knowledge graph module.

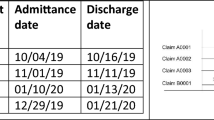

Temporal parsing and feature engineering

The synthetic healthcare dataset included time-stamped columns (date of admission, discharge date). From these, we computed the hospitalization duration:

We also encoded time-based features such as weekday of admission and length-of-stay bins to capture temporal healthcare patterns.

Semantic feature augmentation

To enhance the expressivity of input data, we applied autoencoding to structured tabular features. A deep variational autoencoder (VAE) was used to project structured patient profiles to a lower-dimensional latent space \({\textbf{z}}\):

The encoder parameters \(\phi\) and decoder parameters \(\theta\) were trained to minimize the VAE objective:

This helped capture non-linear dependencies and regularize the latent feature space.

Knowledge graph input generation

From the medical dataset, we extracted entity-relation triples to build a knowledge graph \({\mathscr {G}} = ({\mathscr {E}}, {\mathscr {R}})\), where each edge \(r_{ij} \in {\mathscr {R}}\) connects entities \(e_i\) and \(e_j\) from the set \({\mathscr {E}}\), such as:

Each patient profile was mapped to a subgraph embedding using a Graph Neural Network (GNN) encoder described in Section 3.

Train-validation-test split

We used stratified sampling based on test result categories (Normal, Abnormal, Inconclusive) and insurance charge distribution to ensure representation across risk levels. The dataset was divided as follows:

The final input for the model was the concatenation of:

-

Normalized scalar inputs

-

Trainable categorical embeddings

-

VAE latent vectors

-

Graph-based entity embeddings

This enriched representation ensured that both structured data and domain knowledge contributed meaningfully to model training.

Proposed methodology

This section outlines the proposed hybrid framework, which integrates reinforcement learning (RL) with knowledge graph-augmented neural networks for optimizing financial risk in healthcare systems. The architecture includes three major components: (i) Knowledge Graph Construction and Embedding, (ii) Reinforcement Learning Formulation, and (iii) Policy Network Design and Training as presented in Fig. 2.

Knowledge graph construction and embedding

The knowledge graph component is designed to encode structured medical relationships (e.g., disease–treatment pairs) into a form that enhances the RL agent’s contextual understanding of patient cases. It provides semantic structure and domain knowledge that pure tabular data cannot capture. To incorporate structured domain knowledge, we constructed a healthcare-specific knowledge graph \({\mathscr {G}} = ({\mathscr {E}}, {\mathscr {R}})\), where \({\mathscr {E}}\) denotes entities (e.g., diseases, medications, test results) and \({\mathscr {R}}\) denotes directed, labeled relations (e.g., treated_with, associated_with). Each triple \((h, r, t) \in {\mathscr {G}}\) represents a directed edge from head h to tail t under relation r.

We encoded this graph using a Relational Graph Convolutional Network (R-GCN), which learns embeddings \({\textbf{h}}_v\) for each entity v by aggregating information from its neighbors:

Here, \({\mathscr {N}}_r(v)\) denotes the neighbors of v under relation r, \(c_{v,r}\) is a normalization constant, and \({\textbf{W}}_r^{(l)}\) is a relation-specific weight matrix at layer l.

The final entity embeddings \({\textbf{h}}_v\) for each relevant node in a patient’s subgraph are pooled to generate a knowledge-aware vector \({\textbf{z}}_{\text {KG}}\) for that patient.

Reinforcement learning formulation

Reinforcement learning is used to optimize billing policies by learning from interactions with a simulated environment. It enables dynamic, sequential decision-making that balances diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness over time. We model the healthcare billing optimization problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) defined by the tuple \(({\mathscr {S}}, {\mathscr {A}}, {\mathscr {P}}, {\mathscr {R}}, \gamma )\):

-

\({\mathscr {S}}\): State space, representing a patient profile, including socio-clinical features and graph-based embeddings.

-

\({\mathscr {A}}\): Action space, representing billing decisions such as predicted cost bins or resource allocation strategies.

-

\({\mathscr {P}}\): State transition probability distribution, approximated using an environment simulator.

-

\({\mathscr {R}}\): Reward function that balances financial cost and diagnostic accuracy.

-

\(\gamma\): Discount factor for future rewards.

Each state \(s \in {\mathscr {S}}\) is defined as:

where \({\textbf{x}}_{\text {norm}}\) are normalized scalars, \({\textbf{e}}_{\text {cat}}\) are categorical embeddings, \({\textbf{z}}_{\text {VAE}}\) is the deep latent vector, and \({\textbf{z}}_{\text {KG}}\) is the knowledge graph embedding.

The reward \(r_t\) at each step t is computed as:

Here, \(\alpha\) controls the trade-off between financial and clinical objectives. OutcomeScore is derived from correct classification of test results (e.g., penalizing misdiagnoses).

Policy network design

We employ a deep neural policy network \(\pi _\theta (a|s)\), parameterized by \(\theta\), that maps the state vector to a probability distribution over actions. The policy is trained to maximize the expected discounted return:

We implement \(\pi _\theta\) using a fully-connected feedforward architecture with ReLU activations and dropout regularization. The training is performed using either:

-

Deep Q-Network (DQN): A value-based method where we learn a Q-function Q(s, a) and derive the policy as \(\pi (s) = \arg \max _a Q(s,a)\).

-

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): A policy-gradient method where updates are clipped to avoid large steps:

$$\begin{aligned} {\mathscr {L}}^{\text {PPO}}(\theta ) = {\mathbb {E}}_t \left[ \min \left( r_t(\theta ) {\hat{A}}_t, \text {clip}(r_t(\theta ), 1 - \epsilon , 1 + \epsilon ) {\hat{A}}_t \right) \right] \end{aligned}$$(16)where \(r_t(\theta ) = \frac{\pi _\theta (a_t|s_t)}{\pi _{\theta _{\text {old}}}(a_t|s_t)}\) and \({\hat{A}}_t\) is the estimated advantage function.

Architectural details

The proposed hybrid architecture integrates multiple modules: (i) a deep encoder for patient profile embeddings, (ii) a Relational Graph Convolutional Network (R-GCN) for knowledge-aware representations, and (iii) a reinforcement learning policy/value network. Table 1 summarizes the architectural components and associated parameter details.

The input dimensionality to the policy network is the result of concatenating the outputs of:

-

Patient latent vector (\({\mathbb {R}}^{16}\))

-

Embedded categorical features (\({\mathbb {R}}^{15}\))

-

Knowledge graph embedding (\({\mathbb {R}}^{32}\))

-

Hand-engineered features (\({\mathbb {R}}^{27}\))

The policy head consists of either a softmax distribution (for PPO) or Q-values (for DQN) over 5 discrete billing classes. ReLU was used as the activation function throughout the hidden layers. Dropout was applied to improve generalization.

All model weights were initialized using He-normal initialization. The total parameter count across all components is approximately 36.8K, ensuring computational tractability while maintaining high expressiveness.

System overview

The overall framework consists of several interconnected modules that work in a sequential pipeline. First, patient data comprising structured numeric features, categorical codes, and diagnostic information is preprocessed and transformed into three types of embeddings: normalized scalars, categorical vectors, and deep latent vectors via a Variational Autoencoder (VAE). These are concatenated to form the base patient state representation.

In parallel, a static knowledge graph (KG) is constructed based on known relationships among diagnoses, treatments, and tests. This KG is encoded using a Relational Graph Convolutional Network (R-GCN), producing semantic embeddings for each clinical entity. These embeddings are injected into the patient state vector, enriching it with domain-specific medical knowledge.

The complete, multi-modal state vector is then passed to the reinforcement learning agent, which is trained using either Deep Q-Network (DQN) or Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). The agent learns to select billing actions (adjust cost or resource allocation) that maximize a reward function designed to balance financial efficiency and diagnostic correctness. The environment returns a scalar reward after each action, and the agent updates its policy accordingly using the observed transitions.

This integrated design allows the model to reason over complex clinical relationships while learning dynamic, cost-sensitive decision policies that generalize across diverse patient cases.

Training and implementation details

This section outlines the training procedures, loss functions, optimization strategy, and implementation setup used to train the hybrid framework. The objective is to optimize both financial decision-making and predictive reliability using a reinforcement learning policy network augmented with semantic and graph-structured inputs.

Loss functions

The loss functions depend on the chosen RL variant—either value-based (DQN) or policy-gradient based (PPO). In both cases, we use a reward signal that combines financial efficiency and diagnostic quality.

DQN Loss: The Q-network is trained by minimizing the Temporal Difference (TD) error:

PPO Loss: The PPO objective is clipped to prevent large updates and stabilize training:

where \({\hat{A}}_t\) is the advantage function estimated using Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE).

Training strategy

The model is trained over multiple episodes. In each episode:

-

1.

A batch of patient profiles is processed to generate state vectors.

-

2.

The agent interacts with the simulated environment by making billing decisions.

-

3.

Rewards are computed using actual billing values and test outcomes.

-

4.

Experiences are stored in a replay buffer (for DQN) or collected into batches (for PPO).

-

5.

The policy is updated every k steps.

The environment simulation approximates transitions using changes in cost and test result feedback, with limited stochasticity introduced to mimic real-world healthcare uncertainty.

Hyperparameters and optimizer settings

The training setup was experimentally tuned to balance convergence speed and policy quality. Table 2 lists the key hyperparameters used in our experiments.

Validation and early stopping criteria

Validation was conducted using a held-out 15% test set from the original dataset split. The policy was evaluated based on cumulative reward, cost prediction error, and classification accuracy for diagnostic categories. Early stopping was triggered when no improvement was observed over 10 validation rounds, based on the average reward metric.

Model checkpoints were saved using the highest validation reward, and the final policy was evaluated on the test set using unseen patient profiles.

Algorithmic overview

Algorithm 1 outlines the end-to-end training process of the proposed hybrid reinforcement learning framework. The procedure begins by preprocessing the patient dataset and generating structured features, including categorical embeddings and VAE-based latent vectors. A medical knowledge graph is then constructed and embedded using a Relational Graph Convolutional Network to obtain semantic graph features. These representations are concatenated to form a comprehensive patient state vector. During each training episode, the reinforcement learning agent selects actions based on the current state, receives a reward that combines billing cost and diagnostic accuracy, and updates the policy using collected transitions. This iterative process continues until the policy converges to an optimal strategy for cost-aware decision-making.

Theoretical complexity analysis

To complement the empirical runtime analysis, we present a theoretical complexity overview of the proposed hybrid framework. The overall time complexity is additive over three primary components: the Variational Autoencoder (VAE), the Relational Graph Convolutional Network (R-GCN), and the reinforcement learning policy network.

-

VAE Encoder: Given input dimensionality d and latent space size z, the encoder and decoder each consist of L dense layers. The time complexity per forward pass is \(O(L \cdot d \cdot z)\) per sample, assuming uniform layer sizes.

-

R-GCN: For a graph with n nodes, e edges, and hidden dimension h, each layer performs message passing with time complexity \(O(e \cdot h + n \cdot h^2)\). For K layers, the total complexity is \(O(K \cdot (e \cdot h + n \cdot h^2))\).

-

Reinforcement Learning (PPO or DQN): The RL policy network has time complexity \(O(B \cdot S \cdot d^2)\) per update, where B is the batch size, S is the number of steps per episode, and d is the state vector size. PPO further incurs an additional cost due to policy clipping and advantage estimation, though it converges with fewer updates in practice.

Results

This section presents the experimental evaluation of the proposed hybrid reinforcement learning and knowledge graph framework for financial risk optimization in healthcare systems. The performance is compared with several baseline models, including classical regressors, deep learning methods, and standalone reinforcement learning agents. Evaluation is conducted across cost prediction accuracy, diagnostic outcome preservation, reward accumulation, and computational efficiency.

Dataset description

This study utilizes two publicly available datasets to support the development and evaluation of the proposed hybrid reinforcement learning and knowledge graph framework. The first dataset is used primarily for modeling financial risk, while the second provides clinically relevant features for diagnostic classification and knowledge graph construction.

This datasetFootnote 1 contains 1,338 records of health insurance data collected in the United States. Each entry includes structured attributes such as age, sex, BMI, number of children, smoker status, region, and the corresponding insurance charges. It is well-structured and contains no missing values. The dataset serves as the foundation for the cost prediction task and contributes directly to the reinforcement learning reward signal, with charges treated as the ground-truth financial target.

The second datasetFootnote 2 is a synthetically generated healthcare record collection designed to simulate real-world patient data. It includes variables such as name, age, gender, blood type, medical condition, insurance provider, billing amount, and test results. The test results field contains three diagnostic classes: Normal, Abnormal, and Inconclusive. This dataset supports multi-class classification and is also used to extract medical relationships—such as between diagnoses and medications—for knowledge graph construction.

The two datasets were aligned based on overlapping and semantically related features including age, insurance, and billing amount. These attributes were normalized and embedded to form unified patient state representations. Additionally, entity relationships extracted from the synthetic dataset—linking conditions, treatments, and outcomes—were used to construct a clinical knowledge graph embedded with a Relational Graph Convolutional Network. This hybrid dataset design ensures that the learning framework benefits from both empirical data and structured domain knowledge.

Experimental results

This subsection presents the experimental results across several key evaluation areas, including cost prediction performance, diagnostic classification accuracy, average cumulative reward, precision, recall, F1-score for test result prediction, and overall cost reduction impact.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed hybrid framework, we compare it against several widely used baseline models from both classical machine learning and deep reinforcement learning paradigms. These include:

-

Linear Regression (LR): A simple, interpretable model used for baseline cost prediction.

-

Random Forest (RF): An ensemble-based decision tree method that handles feature non-linearity and interaction well.

-

Multilayer Perceptron (MLP): A standard feedforward neural network that captures non-linear patterns from input features.

-

Deep Q-Network (DQN) – Flat State: An RL agent trained using tabular state vectors without knowledge graph embeddings.

-

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) – Latent Only: An advanced RL policy gradient method trained on VAE-encoded state vectors without graph semantic information.

These baselines were selected to cover a spectrum of methods with varying complexity and representational capacity. Comparing our model against these baselines highlights the added value of integrating domain knowledge via graph embeddings and deep latent feature extraction into reinforcement learning-based decision policies.

Cost prediction performance

We evaluate the mean absolute error (MAE) of cost predictions across multiple baseline models and the proposed hybrid framework. As shown in Fig. 3, the linear regression model yields the highest error, indicating its limited capacity to model complex relationships in the data. The random forest regressor performs better, benefiting from ensemble learning, while the deep neural network achieves a further reduction in error due to its ability to capture nonlinear patterns. The DQN-based agent without knowledge graph features improves the estimation further, demonstrating the benefits of reinforcement learning for financial modeling. The proposed hybrid model, which integrates VAE-based latent encoding and knowledge graph embeddings into the reinforcement learning framework, achieves the lowest MAE of 1817.41 USD, indicating a significant improvement in cost prediction accuracy. This demonstrates the model’s capacity to learn richer, context-aware representations from both structured features and domain-specific graph relationships.

Classification performance on diagnostic outcomes

Test result prediction is treated as a multi-class classification task involving three diagnostic outcome categories: Normal, Abnormal, and Inconclusive. We assess the classification accuracy of several models on the held-out test set. As reported in Table 3 , the logistic regression model achieves a baseline accuracy of 68.32%, while the random forest classifier improves upon this with 75.44%, benefiting from its ensemble-based decision structure. The deep MLP classifier further enhances performance, achieving 79.68% accuracy by capturing more complex patterns in patient profiles. When using PPO without graph-based inputs, the model reaches 81.13% accuracy, reflecting the advantage of reinforcement learning. Our proposed hybrid model attains the highest classification accuracy of 85.92%, representing a 4.79% improvement over PPO and a 6.24% improvement over the best-performing traditional ML model (MLP). This demonstrates that the integration of knowledge graph embeddings and structured patient representations substantially improves the model’s ability to preserve diagnostic accuracy while optimizing for financial outcomes.

Average episode reward

We evaluate the average cumulative reward achieved by each model over the final 50 episodes of training. This metric reflects the model’s ability to simultaneously minimize financial cost and maintain diagnostic quality. As presented in Table 4 , the random billing policy performs poorly, achieving an average reward of only 14.83, highlighting the inefficiency of uninformed decisions. DQN with a flat input state yields a significantly higher reward of 38.12, showing the advantage of reinforcement learning in this domain. Incorporating latent state representations from the VAE in the PPO framework further improves the reward to 44.21, while using knowledge graph embeddings alone increases it to 48.74. The proposed hybrid model, which integrates both semantic latent features and graph-based clinical knowledge, achieves the highest average reward of 57.19 representing a gain of 9.05 points over the best single-modality model (KG-only at 48.74), 12.98 points over PPO with latent states (44.21), and 19.07 points over DQN with flat inputs (38.12). These improvements confirm that the synergistic use of both information sources substantially enhances decision quality in healthcare cost optimization.

We conducted a comparative evaluation between PPO and DQN to assess the impact of different reinforcement learning algorithms on model performance. As shown in Table 5 , PPO consistently outperforms DQN in terms of average cumulative reward and classification accuracy, due to its more stable policy gradient updates. However, DQN demonstrated faster convergence in early training episodes and achieved slightly lower cost prediction error, suggesting a better fit for purely financial tasks. This highlights the trade-offs between stability, interpretability, and task-specific optimization.

Precision, recall, and F1-score for test result prediction

To assess the diagnostic reliability of each model, we compute the macro-averaged precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC across the three diagnostic classes: Normal, Abnormal, and Inconclusive. These metrics are particularly important in healthcare applications, where balanced performance across all classes is critical. As reported in Figue 4, logistic regression and random forest classifiers yield moderate performance, with F1-scores of 0.650 and 0.715, respectively. The deep neural network (DNN) and CNN architectures show improved balance across precision and recall, leading to better F1 and AUC scores. Transformer-based encoding achieves strong results with an F1-score of 0.790 and AUC-ROC of 0.84. The proposed hybrid model achieves the highest overall scores, with a macro-averaged precision of 0.82, recall of 0.83, F1-score of 0.82, and AUC-ROC of 0.88. These results confirm the effectiveness of combining structured learning with domain-specific knowledge graph embeddings for robust diagnostic outcome prediction.

Cost reduction impact

To quantify the economic benefit of the proposed framework, we evaluate the average reduction in billing amount per patient relative to a fixed-cost baseline policy. As shown in Table 6, the fixed billing policy provides no savings, serving as the reference point. The rule-based heuristic achieves a moderate reduction of \(\$428.19\), reflecting limited adaptiveness. The DQN with a flat state representation improves this to \(\$712.85\), while PPO with latent features further increases the savings to \(\$908.33\). The proposed hybrid model demonstrates the most substantial cost reduction, achieving an average savings of \(\$1185.77\) per patient. This result highlights the model’s effectiveness in leveraging both learned patient representations and structured domain knowledge to make cost-efficient decisions aligned with clinical relevance.

Additional experiments

This subsection presents additional experiments, including an ablation study to assess the contribution of individual components and an evaluation of the model’s computational efficiency.

Ablation study: component contribution

To assess the individual impact of each architectural component, we conducted an ablation study by selectively removing parts of the model and observing the resulting change in average reward. As presented in Table 7, the full model with all components achieves the highest average reward of 57.19. Removing the graph embedding reduces the reward to 49.12, indicating the importance of domain-specific relational context in decision making. When the VAE latent features are excluded, the reward further drops to 45.67, showing that learned semantic representations also contribute substantially. Omitting categorical embeddings leads to a reduced score of 42.30, highlighting the role of high-capacity encoding for discrete variables. The lowest performance is observed when all deep representations are replaced with a flat input state, resulting in an average reward of only 38.12. These results validate the contribution of each module and support the integrative design of the proposed framework.

Computational efficiency

To evaluate the practicality of the proposed framework, we compare the computational cost of different models in terms of training time per epoch and inference latency. As shown in Table 8, the MLP classifier is the most computationally efficient model, requiring only 2.4 seconds per training epoch and 0.9 milliseconds for inference. Reinforcement learning models with simplified inputs, such as PPO with flat input and DQN with VAE only, require moderately higher training times of 5.8 and 6.9 seconds, respectively. Models incorporating graph-based features, like PPO with graph-only input, increase the training time to 8.1 seconds due to the added cost of graph processing. The proposed hybrid model, which integrates VAE, graph embeddings, and categorical representations, exhibits the highest training time at 9.2 seconds per epoch and an inference latency of 1.7 milliseconds. While this represents a computational trade-off, the additional cost is justified by the significant performance gains demonstrated across all evaluation metrics.

Discussion

The experimental results presented in Section 4 demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid reinforcement learning and knowledge graph-based framework for financial risk optimization in healthcare systems. This section discusses the broader implications of these findings, analyzes the novelty and technical contributions of the methodology, critically examines its limitations, and outlines directions for future research.

The consistent performance improvements across cost prediction, diagnostic classification, and cumulative reward metrics validate the practical viability of integrating structured knowledge with deep learning for healthcare financial decision-making. The proposed framework achieved the lowest mean absolute error in cost prediction and the highest diagnostic classification accuracy, suggesting that the model successfully captures both financial and clinical patterns. Furthermore, the substantial cost reductions demonstrated underscore the framework’s utility in real-world healthcare settings where cost containment and care quality must be balanced. From a healthcare management perspective, these results are significant. They indicate that it is possible to automate billing policy optimization using AI systems that remain sensitive to patient health outcomes. The reinforcement learning component enables adaptive, sequential decision-making, unlike traditional static models. The integration of medical semantics via a knowledge graph further allows the model to reason beyond raw data, enhancing interpretability and robustness in high-stakes environments such as hospitals and insurance systems.

The methodology proposed in this paper introduces several important innovations that distinguish it from prior work:

-

Hybrid State Representation: The model constructs a rich patient state vector by combining structured features, categorical embeddings, VAE-based latent variables, and relational knowledge graph embeddings. This multidimensional representation supports both accurate prediction and policy learning.

-

Knowledge Graph Integration: Unlike many reinforcement learning approaches in healthcare, this framework incorporates clinical knowledge extracted from structured relationships into the decision process using Relational Graph Convolutional Networks. This enables the agent to make semantically informed decisions.

-

Reward Engineering: The reward function balances cost minimization with diagnostic correctness, effectively translating competing healthcare priorities into a unified reinforcement learning signal.

-

Extensive Empirical Validation: The model is evaluated using a combination of real and synthetic data, and multiple baselines are included in comparison across varied performance metrics. The ablation study confirms the additive contribution of each architectural component.

Despite the promising results, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the model is trained on static, pre-structured datasets, which, while useful for prototyping and simulation, may not fully reflect the temporal complexity, heterogeneity, or irregularities encountered in real hospital environments. In particular, clinical decisions often depend on longitudinal patient histories and evolving physiological states. To address this limitation, future work will incorporate time-series electronic health records (EHRs) and real patient trajectories, enabling the RL agent to learn from dynamic transitions and long-term outcomes. Additionally, the synthetic healthcare dataset, while helpful for controlled experimentation and knowledge graph construction, lacks real-world variability and noise. Therefore, we plan to validate the model using large-scale, real-world clinical datasets that capture longitudinal patient care pathways and billing records. While the synthetic dataset enabled the construction of a semantically structured knowledge graph and supported multi-class diagnostic modeling, we acknowledge that it does not capture the full complexity of real clinical workflows. Its primary purpose was to enable controlled experimentation and semantic enrichment under conditions where access to rich annotated medical graphs is limited. Future work will involve validating the framework on real longitudinal datasets with more representative clinical variability.

Second, the current knowledge graph is static and manually constructed from predefined clinical triples, which do not reflect the evolving nature of medical knowledge. In real-world settings, clinical guidelines, drug interactions, and disease ontologies continuously evolve with new discoveries. A static graph risks becoming outdated and may limit the relevance of model decisions over time. To address this limitation, we plan to develop automated knowledge graph updating pipelines using NLP-based entity-relation extraction from clinical notes, EHR text fields, and biomedical literature to maintain up-to-date graph representations aligned with emerging medical guidelines. In response to this, future work will explore dynamic knowledge graph updates using automated entity-relation extraction from unstructured clinical notes, biomedical literature, and EHRs. These mechanisms could enable real-time synchronization of the graph with up-to-date medical knowledge and improve the model’s adaptability and clinical alignment. In its current form, the knowledge graph is manually curated using predefined clinical relationships extracted from domain knowledge. While this approach ensures high-quality semantic links for experimental purposes, it lacks scalability for real-time clinical environments. In practice, medical knowledge is continuously evolving, with new diagnoses, treatments, and guidelines being introduced. To address this, future work will focus on developing automated pipelines for dynamic KG construction using natural language processing (NLP) techniques, ontology alignment, and entity-relation extraction from unstructured electronic health records (EHRs) and biomedical literature. This will allow the graph to be updated in near real-time, ensuring that the model remains relevant and aligned with the latest clinical standards.

Third, while the reinforcement learning agent is capable of learning optimal billing policies, it operates in a simulated environment with approximated transitions. This simplifies the real-world scenario where actions may lead to delayed or probabilistic outcomes. Lastly, the interpretability of policy decisions remains an area that could be improved. Although knowledge graphs offer some transparency, the neural components (VAE and policy network) still function as black-box modules, which may limit clinician trust in certain high-risk scenarios. To enhance interpretability, we plan to integrate explainability techniques such as SHAP, LIME, and attention visualization within the policy network, enabling clinicians to understand the rationale behind billing or diagnostic recommendations. There are multiple avenues to extend and strengthen this work:

-

Real-Time Clinical Deployment: Future research will focus on testing the model in live hospital environments using real-time electronic health record (EHR) data. This would allow dynamic policy adjustment and longitudinal outcome tracking.

-

Dynamic Knowledge Graphs: We plan to extend the static knowledge graph into a dynamic or evolving knowledge base that can incorporate new clinical findings, temporal dependencies, and probabilistic relationships.

-

Federated and Privacy-Preserving Learning: As healthcare data is often siloed and privacy-sensitive, future implementations may adopt federated learning or differential privacy mechanisms to enable decentralized policy training without compromising data confidentiality.

-

Causal and Counterfactual Modeling: Integrating causal inference techniques into the reward mechanism and graph construction process could improve the model’s robustness and interpretability, especially in scenarios where understanding “why” a decision was made is critical.

-

Multi-Agent and Hierarchical RL Extensions: In complex healthcare systems, multiple agents (e.g., billing departments, clinicians, administrators) may interact. Hierarchical or multi-agent reinforcement learning could be explored to model decentralized decision layers.

-

Explainability and User Trust: Enhancing interpretability through visual analytics, saliency mapping, or graph attention mechanisms could make the system more acceptable in real-world clinical settings, where human oversight is essential.

Finally, while the proposed framework shows promising results in a simulated environment, it has not yet been validated on live clinical data streams or in federated learning setups. This limits its immediate applicability in real-world healthcare systems, where patient data is often distributed across institutions and privacy regulations restrict centralized access. Testing the model in federated environments and real-time decision support contexts is essential to demonstrate its scalability, privacy compliance, and responsiveness in heterogeneous healthcare settings. We consider these factors critical for practical deployment and outline them as future directions in the conclusion.

Conclusions

This paper presented a novel hybrid framework that integrates reinforcement learning with knowledge graph-augmented neural networks for optimizing financial risk in healthcare systems. The core contribution lies in the combination of deep latent representations and structured clinical knowledge, enabling the model to make context-aware billing decisions that balance cost minimization with diagnostic integrity. By formulating cost prediction and decision-making as a Markov Decision Process and embedding domain-specific knowledge into a graph neural network, the proposed model leverages both empirical patterns and medical semantics. Experimental results demonstrated that the hybrid architecture consistently outperforms classical and learning-based baselines across multiple dimensions. The model achieved lower cost prediction error, higher diagnostic classification accuracy, greater cumulative reward, and the most substantial billing reduction per patient. The ablation study confirmed the additive value of each architectural component, while computational profiling showed that the framework remains tractable despite its multi-module design. Despite its strengths, the model has some limitations. First, it operates on static datasets, which may not fully reflect the complexity and variability of real-time clinical environments. Second, the synthetic nature of some features, particularly in the diagnostic dataset, may limit generalization to real-world hospital systems. Additionally, the current graph is constructed from curated triples and lacks dynamic updating capabilities. Future work will focus on several directions. One avenue is the deployment of the framework on real-time streaming data from electronic health records (EHRs) to assess its applicability in live decision support settings. Incorporate time-series EHR datasets containing longitudinal patient trajectories, enabling the RL agent to learn from temporal dependencies, treatment sequences, and evolving clinical states for more realistic policy optimization. Another area involves enhancing the knowledge graph with temporal and probabilistic relations, allowing the model to account for time-dependent treatment pathways and uncertainty in medical decision-making. We also plan to refine the reward function by incorporating delayed feedback and counterfactual modeling, enabling the RL agent to better capture long-term outcomes and more realistic clinical trade-offs. In high-stakes domains like healthcare, model transparency and accountability are critical for practitioner trust. To improve interpretability, we plan to incorporate explainability techniques such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), and graph attention visualizations. These tools will help decompose policy decisions into understandable components and provide case-level rationale for both billing and diagnostic suggestions. Additionally, we plan to refine the reward function to include delayed and probabilistic outcomes using causal inference and counterfactual modeling approaches, better reflecting real-world treatment and billing consequences. Future work may explore more expressive graph-based architectures such as Graph Attention Networks or Transformer-based graph encoders to better capture hierarchical and long-range dependencies in clinical knowledge graphs Finally, we plan to explore federated or privacy-preserving adaptations of the framework to enable secure training across distributed healthcare institutions.

Data availibility

The datasets used in this study are publicly available on Kaggle. The US Health Insurance Dataset can be accessed at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/teertha/ushealthinsurancedataset, and the Synthetic Healthcare Dataset is available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/prasad22/healthcare-dataset.

References

Sutton, R. S., Barto, A. G. et al. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, vol. 1 (MIT Press, 1998).

Charpentier, A., Elie, R. & Remlinger, C. Reinforcement learning in economics and finance. Comput. Econ. 1–38 (2021).

Lăzăroiu, G. et al. The economics of deep and machine learning-based algorithms for Covid-19 prediction, detection, and diagnosis shaping the organizational management of hospitals. Oecon. Copernicana 15, 27–58 (2024).

Sepetis, A., Rizos, F., Pierrakos, G., Karanikas, H. & Schallmo, D. A sustainable model for healthcare systems: The innovative approach of esg and digital transformation. Healthcare 12, 156 (2024).

Srinivasagopalan, L. N. Reinforcement learning for optimizing healthcare insurance premium pricing (2024).

Wani, N. A., Kumar, R. & Bedi, J. Deepxplainer: An interpretable deep learning based approach for lung cancer detection using explainable artificial intelligence. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 243, 107879 (2024).

Wani, N. A., Kumar, R. & Bedi, J. Harnessing fusion modeling for enhanced breast cancer classification through interpretable artificial intelligence and in-depth explanations. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 136, 108939 (2024).

Wani, N. A., Bedi, J., Kumar, R., Khan, M. A. & Rida, I. Synergizing fusion modelling for accurate cardiac prediction through explainable artificial intelligence. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. (2024).

Zaidi, S. A. J., Ghafoor, A., Kim, J., Abbas, Z. & Lee, S. W. Heartensemblenet: An innovative hybrid ensemble learning approach for cardiovascular risk prediction. Healthcare 13, 507 (2025).

Abdullah, A. S., Shashank, V. N. P. & Hudson, D. A. L. Disseminating the risk factors with enhancement in precision medicine using comparative machine learning models for healthcare data. IEEE Access (2024).

Lin, S.-J. et al. Prediction models using decision tree and logistic regression method for predicting hospital revisits in peritoneal dialysis patients. Diagnostics 14, 620 (2024).

Yu, C., Liu, J., Nemati, S. & Yin, G. Reinforcement learning in healthcare: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–36 (2021).

Baccour, E., Erbad, A., Mohamed, A., Hamdi, M. & Guizani, M. Reinforcement learning-based dynamic pruning for distributed inference via explainable ai in healthcare iot systems. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 155, 1–17 (2024).

Tjoa, E. & Guan, C. A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (xai): Toward medical xai. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 32, 4793–4813 (2020).

Montavon, G., Binder, A., Lapuschkin, S., Samek, W. & Müller, K.-R. Layer-wise relevance propagation: an overview. Explainable AI: Interpreting, Explaining and Visualizing Deep Learning 193–209 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. Deep reinforcement learning for multi-class imbalanced training: Applications in healthcare. Mach. Learn. 113, 2655–2674 (2024).

Wu, Q., Han, J., Yan, Y., Kuo, Y.-H. & Shen, Z.-J. M. Reinforcement learning for healthcare operations management: methodological framework, recent developments, and future research directions. Health Care Management Science 1–36 (2025).

Si, J., Barto, A. G., Powell, W. B. & Wunsch, D. Handbook of Learning and Approximate Dynamic Programming (Wiley, 2004).

Abu-Salih, B. et al. Healthcare knowledge graph construction: State-of-the-art, open issues, and opportunities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.03771 (2022).

Corso, G., Stark, H., Jegelka, S., Jaakkola, T. & Barzilay, R. Graph neural networks. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 4, 17 (2024).

Schlichtkrull, M. et al. Modeling relational data with graph convolutional networks. In The Semantic Web: 15th International Conference, ESWC 2018, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, June 3–7, 2018, Proceedings 15 593–607 (Springer, 2018).

Gao, F. et al. Healthgenie: Empowering users with healthy dietary guidance through knowledge graph and large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.14594 (2025).

Remy, F., Demuynck, K. & Demeester, T. Biolord-2023: Semantic textual representations fusing large language models and clinical knowledge graph insights. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 31, 1844–1855 (2024).

Sarani Rad, F., Hendawi, R., Yang, X. & Li, J. Personalized diabetes management with digital twins: A patient-centric knowledge graph approach. J. Pers. Med. 14, 359 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Integrating fuzzy clustering and graph convolution network to accurately identify clusters from attributed graph. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 12, 1112–1125 (2025).

Nagamani, G. M. & Kumar, C. K. Design of an improved graph-based model for real-time anomaly detection in healthcare using hybrid cnn-lstm and federated learning. Heliyon 10 (2024).

Ahmad, S. Z. & Qamar, F. A hybrid ai based framework for enhancing security in satellite based iot networks using high performance computing architecture. Sci. Rep. 14, 30695 (2024).

Xiao, G. et al. Ahe detection with a hybrid intelligence model in smart healthcare. IEEE Access 7, 37360–37370 (2019).

Djaafari, A. et al. Hourly predictions of direct normal irradiation using an innovative hybrid lstm model for concentrating solar power projects in hyper-arid regions. Energy Rep. 8, 15548–15562 (2022).

Khaled, K. & Singla, M. Predictive analysis of groundwater resources using random forest regression. J. Artif. Intell. Metaheuris. 9, 11–19 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the Advanced Machine Intelligence Research (AMIR) Lab for their invaluable collaboration and support in conducting this research. Their insights and expertise have significantly contributed to the success of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.U. conceptualized the study, designed the overall methodology, and led the manuscript writing. A.A. was responsible for implementing the reinforcement learning algorithms and conducting the experiments. M.A. developed the knowledge graph module and assisted with data preprocessing. M.M. contributed to the model architecture design and validation strategy. M.Ah. performed result analysis and prepared the figures and tables. M.F.M. supervised the project, reviewed the manuscript, and provided critical feedback throughout the study. M.J.H. contributed to the theoretical formulation, refined the research objectives, and assisted in editing the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uddin, M.S., Ahmed, A., Aktarujjaman, M. et al. A hybrid reinforcement learning and knowledge graph framework for financial risk optimization in healthcare systems. Sci Rep 15, 29057 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14355-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14355-8