Abstract

Feeding intolerance (FI) is a major challenge among extremely low birthweight (ELBW) preterm infants, impacting their growth, development, and overall clinical outcomes. We aimed to identify factors associated with FI in ELBW preterm infants and examine the relationship between FI and respiratory support modalities. Our retrospective review of medical records of all ELBW preterm infants between 12/2016 and 12/2021 revealed that 78 (58%) of the 133 ELBW infants (median gestational age 26.5 weeks, median birth weight 809 g) had FI. FI was more common in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and periventricular leukomalacia (n = 69 vs. n = 24 and n = 11 vs. n = 2, respectively, p < 0.001). Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) had the highest FI rate (7.8 per 100 device-days) compared with other noninvasive ventilation modes (p < 0.001). Infants with FI required longer to achieve full enteral feeding (median 18 vs. 14 days for infants without FI, p < 0.001) and had longer neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) stays (median 89.5 vs. 47 days, respectively, p < 0.001). We conclude that provision of NIPPV support was associated with higher FI rates and longer NICU stays in preterm ELBW infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The care and management of extremely low birthweight (ELBW, < 1000 g) preterm infants represent a formidable challenge in the field of neonatal medicine, necessitating a nuanced understanding of multifactorial issues that influence their well-being. Among the myriad of complications faced by these infants, feeding intolerance (FI) emerges as a critical concern, posing substantial clinical implications for their growth and development1,2. Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is a common condition among premature infants and one of the major causes of neonatal mortality3,4. The choice of ventilation support in these fragile neonates is a pivotal determinant of their respiratory outcomes and overall survival5. The coexistence of RDS and FI poses an even weightier challenge for the neonatologist6. Because of gastrointestinal (GI) immaturity, a considerable proportion of premature infants will develop clinical symptoms of FI, causing feeding difficulties. As such, the preterm ELBW infants represent a unique group with concurrent pulmonary and eating dysfunctions1,6. While a delay in the establishment of adequate enteral nutrition and prolonged need for parenteral nutrition increase the risk of infections and extended hospital stay1,6,7,8, the association between ventilatory support and the occurrence of FI has been proposed but not studied in depth1,9. We therefore aimed to investigate factors associated with FI and their relation to selected respiratory support modes in a large and detailed cohort of preterm ELBW infants. We hypothesized that non-invasive ventilation is associated with FI in extremely low birthweight preterm infants.

Methods

Patient population and study design

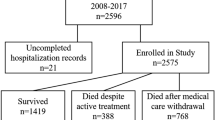

This retrospective cohort study included all preterm ELBW infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of the Tel Aviv Medical Center between December 2016 and December 2021. Infants with major malformations or genetic syndromes often receive altered feeding protocols and may have inherently different FI risk and were thus excluded from the study. Surgical patients experience variable gut anatomy and postoperative feeding regimens and were also excluded from the study to ensure a more homogeneous ELBW cohort and clearer interpretation of ventilatory support effects on FI.

The medical center’s ethics committee approved the study protocol (#0557-23-TLV) and waived written informed consent for this anonymized retrospective analysis. Te data were handled in accordance with the Principles of Good Clinical Practice. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data acquisition

Maternal and neonatal pre- and postnatal data were retrieved from medical records. The data spanned the time from delivery until the infants were discharged from the hospital or had died while hospitalized. Maternal data included demographics as well as clinical information, such as mode and indication for induced or cesarean delivery and maternal use of antenatal corticosteroids. Neonatal data included comorbidities and adverse clinical events, such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and spontaneous intestinal perforation (SIP). Length of hospitalization and weight at discharge were presented as age- and sex-specific percentiles. Mode and length of ventilation for each method were recorded and they included synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV), volume guarantee ventilation (VGV), high-frequency ventilation (HFV), non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV), nasal continuous positive airway pressure ventilation (NCPAP), and heated humidified high-flow nasal cannula (HHHFNC).

Enteral feeding

During the study period, our NICU followed local parenteral and enteral nutrition protocols that were in line with the European enteral nutrition guidelines10. Parenteral nutrition was started immediately after birth as soon as intravenous access was available and generally discontinued when enteral feeds exceeded 140–150 ml/kg/day. Early trophic feeding with minimal amounts (1–2 ml every 3 h) was started during the first postnatal day. When the infant’s mother’s milk was not available, preterm formula or donor breast milk from a bank was used, and the amount of enteral feeding was gradually increased according to tolerance. Milk fortification was started when the enteral intake reached 80 ml/kg/day. Full enteral feeding was defined by an intake of 150 ml/kg/day. The collected nutritional data included type of feed (maternal milk, donor milk, formula, combination) and time to full feed.

Definitions of study variables

Birthweight was converted to age- and sex-specific percentiles using the local growth chart11. IVH was graded according to Papile’s classification12, and only grade 3–4 was recorded for study purposes. Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), which also included PDA with no hemodynamic significance, was defined by findings on echocardiography. Thrombocytopenia was defined as < 150 10e3/µl. Bloodstream infection was defined as a positive blood culture, and NEC as Bell stage II or III13. To date a universally accepted definition for FI in preterm infants is not available, thus clinical data from medical records of each patient was extracted and FI was defined only for those with repeated episodes of feeding difficulties – including repeated episodes of vomiting/spitting, abdominal distention as well as by repeated episodes of increased gastric residual volume that required reduction in feeding volume or omission of meals. Choice of respiratory modality followed unit protocols and clinician preference based on respiratory severity.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). All statistical tests were 2-tailed. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the Shapiro-Wilk test were applied to assess the normality of the continuous data. Demographic variables are reported as the median and 25th and 75th percentiles (interquartile range [IQR]), the maximum and minimum (range), or the frequency and percentage. A Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was calculated to compare the distribution of categorical variables. An independent sample t-test or an independent sample Mann–Whitney test was used to compare groups for continuous variables with a normal or skewed distribution, as appropriate. Overlap among NIPPV, NCPAP, and HHHFNC exposures was visualized with a three-circle Venn diagram (Fig. 1). For each modality, total device-days were calculated by summing individual days of use. The feeding-intolerance (FI) incidence rate per 100 device-days was computed as: FI rate=(number of FI events \total device days)×100. Pairwise comparisons of FI rates between modalities were performed using a two-sided z-test. p-values were Bonferroni-adjusted. P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Table 1 depicts baseline clinical characteristics of the infants and their mothers. A total of 133 ELBW infants (n = 63 [48%] males), whose median gestational age was 26.5 weeks [interquartile range 25.2,28.3] and whose median birth weight was 809 [682.5,917.5] grams were included in the study. The mothers’ median age at delivery was 33 years [interquartile range 30,38] and their median body mass index at delivery was 21.5 [19.4,25.7] kg/m². 79% (n = 106) of the infants were delivered by caesarean delivery, and 78 infants (58%) were diagnosed as having FI. There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics of the ELBW infants that developed FI compared to these who did not.

Factors associated with FI (Table 2)

ELBW infants with BPD were more likely to sustain FI than those without BPD (n = 69 [88%] vs. n = 24 [43%] respectively, p < 0.001). There were no significant group differences in the rate of RDS. The presence of periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) was significantly associated with FI (n = 11 [14%] vs. n = 2 [3%]). Interestingly, there were no differences in the FI rate among the ELBW infants with medical NEC, surgical NEC, or SIP (n = 21 [27%] vs. n = 11 [20%] p < 0.22, n = 7 [9%] vs. n = 6 [11%] p < 0.32, n = 3 [4%] vs. n = 3 [55%] p < 0.49, respectively). Infants without FI unexpectedly showed higher rates of pneumothorax than those with FI (n = 10 [18%] vs. n = 4 [5%] p < 0.018). Respiratory support with NIPPV or HHHFNC was associated with higher rates of FI compared to support with NCPAP in the total cohort (78% and 82% vs. 25% FI, respectively, p < 0.001) and in a subgroup analysis restricted solely to infants who developed BPD (n = 93, 89% and 89% vs. 20% FI, respectively, p < 0.05).

A Venn diagram illustrates that only 8 infants were exposed solely to NIPPV, 9 solely to NCPAP, and 2 solely to HHHFNC; 59 infants received both NIPPV and HHHFNC (without NCPAP), 6 both NIPPV and NCPAP (without HHHFNC), 11 both NCPAP and HHHFNC (without NIPPV), and 14 infants cycled through all three modalities. To adjust for duration of exposure, we calculated FI incidence per 100 device-days (Table 3). NIPPV had the highest FI rate (8.1 per 100 device-days) compared with HHHFNC (2.2) and NCPAP (2.0), despite more prolonged use of HHHFNC (p < 0.001).

Outcome according to factors associated with FI (Table 4)

ELBW infants with FI needed significantly longer time to reach full enteral feeding compared to those without FI (median 18 vs. 14 days, respectively, p < 0.001), and their overall NICU stay was significantly longer as well (median 89.5 vs. 47 days, p < 0.001). However, there was no significant group difference in SBI rates (25% vs. 11%, p < 0.08). There was a trend towards lower weight at discharge for the ELBW infants that developed FI compared to those that did not (median Z score − 2.55 vs. -1.87, p < 0.074).

Discussion

The relationship between FI and respiratory support modalities has not been investigated in depth. The results of the present study provide clinical data that demonstrate an association between FI and the use of NIPPV respiratory support as well as with the presence of BPD and PVL in a cohort of ELBW infants. FI was also associated with a longer NICU length of stay and lower weight at discharge.

BPD continues to be one of the most common sequelae related to prematurity in addition to being associated with substantial morbidity and mortality14. BPD results in chronic respiratory disease that can impair an infant’s ability to coordinate breathing with sucking and swallowing during feeds15. Increased work to maintain breathing and respiratory distress are commonly seen in BPD, and it is reasonable to consider that they may impact the infant’s feeding capabilities.

Non-invasive methods of ventilation are gaining acceptance in most NICUs as a tool to decrease the prevalence of BPD and associated comorbidities16. However, premature infants that receive non-invasive breathing support might be more likely to experience respiratory instability that can affect their ability to tolerate feeding9. Few studies have investigated the relationship between FI and the various non-invasive ventilatory techniques among ELBW infants, and the results of comparisons between those methods and the possible effects on enteral nutrition have been conflicting17,18,19,20. The incidence and underlying physiology remain inconclusive. One multicenter randomized clinical trial conducted in Italy reported that NCPAP and HHHFNC had similar effects on FI, with no difference in days to full feed in preterm infants (gestational age [GA] of 25 to 29 weeks) who were stable enough to receive enteral feeds and non-invasive ventilation within the first week of life21. A larger meta-analysis that compared HHHFNC to NCPAP in preterm infants (GA < 37 weeks) found that HHHFNC was superior in terms of shorter time to full feeds, with no significant difference in length of hospitalization18. Another small study conducted in China showed HHHFNC to be superior to NCPAP by enabling shorter time to full feeds, shorter length of hospitalization, and better weight gain17. In our cohort, ELBW infants who developed feeding intolerance were more often managed with NIPPV or HHHFNC compare to NCPAP, reflecting a higher crude frequency of NIPPV or HNPCC exposure among those with FI. However, when we adjusted for total device-days and calculated FI rates per 100 device‐days, only infants on NIPPV showed a significantly elevated FI incidence; HHHFNC and NCPAP were associated with substantially lower rates and did not differ from each other. This finding indicates that the apparent association between HHHFNC and FI in unadjusted counts is largely explained by exposure time and inclusion of infants on the stable chronic phase of support, whereas NIPPV independently predicts feeding intolerance.

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) could affect FI through several mechanisms. First, the gut blood flow depends upon gastric emptying and feeding progression through the GI tract, and decreased blood flow and delayed gastric emptying are associated with FI22,23. NCPAP can keep the airway in the expended state, prevent alveolar collapse, and improve the ventilatory blood flow ratio17. Interestingly, several authors24,25 have reported a correlation between NCPAP ventilation and mesenteric blood flow, showing increased superior mesenteric artery blood flow velocity and increased gastric emptying which correlates with our results. Second, it has been shown that infants on NIV sustain marked gaseous bowel distension9,26, which may affect gastric blood flow and thereby induce FI. A number of small studies looked at the correlation between abdominal distention, FI, and NIV and reported conflicting results27,28,29. NIPPV delivers intermittent peak pressure on positive end-expiratory pressure. It is usually unsynchronized since synchronization is difficult to achieve because of leaks, high respiratory rate, low tidal volume, and irregular breathing patterns30. This can lead to increased air entry into the gastrointestinal tract (aerophagia), abdominal distension, and discomfort, which may impair the coordination of sucking, swallowing, and breathing, and thus worsen feeding tolerance. The risk of gastroesophageal reflux and delayed gastric emptying is also higher with NIPPV due to these pressure changes and increased abdominal distension21,31. In contrast, both CPAP and HHHFNC deliver more stable and continuous airway pressures, with less fluctuation and generally lower mean pressures, which may explain the lower incidence of feeding difficulties compared to NIPPV32.

The development of NEC among ELBW preterm infants is a matter of considerable concern. Many of the clinical signs suggestive of NEC are identical to those of FI (e.g., abdominal distention, gastric residual volume)6,33. In contrast to other prior cohort and meta-analytic data that showed feeding intolerance to increase the susceptibility for NEC33, our study findings showed no differences in the FI rate in ELBW infants with medical NEC, surgical NEC, or SIP. Those results are compatible with the reports of others who also failed to show any direct association between the diagnosis of FI and early enteral feeds and the presence of NEC34,35,36,37. The following can be explained by the differences in inclusion criteria as we included only Bell stage II or III. Furthermore, our standardized FI definition may differ from those earlier reports as well as enteral-feeding protocols that may underlie the divergent results. Interestingly, a large meta-analysis suggested that slow advancement of enteral feeds may slightly increase FI38. This further raises the question of whether or not too many cautionary measures are being routinely taken in order to avoid this dire complication at the expense of achieving enteral feeds.

It should be borne in mind that inadequate early nutrition may contribute to the development of BPD and hinder lung repair39,40,41. Moreover, early enteral nutrition promotes the development and maturation of the GI tract and enhances micronutrient delivery and microbiome development42. In our study, infants with FI needed significantly longer time to reach full enteral feeding compared to those without FI. In addition, their overall length of NICU stay was significantly longer in association with a trend towards their being of lower weight but with no effect on the SBI rate. Indeed, delayed enteral feeding has been shown to promote inflammation which may increase the risk of inadequate linear growth39,42,43,44,45. Further prospective studies are needed in order to assess nutritional and ventilatory strategies to avoid FI as well as their effect on the risk of developing NEC.

This is one of the first studies to assess factors associated with FI in a relatively large and detailed cohort of ELBW infants. It has some limitations that bear mention, starting with its retrospective nature and the lack of a standardized definition of FI which we sought to overcome by relying upon well-established protocols for enteral nutrition. Since this was not a blinded study and the choice of respiratory support modality was based on standard departmental protocols, selection bias may have influenced our results and limits causal inference regarding the association between modality and feeding intolerance.

In conclusion, respiratory support with NIPPV was associated with higher rates of FI among ELBW infants. FI was also associated with a significantly longer stay in the NICU. Larger-sample multicenter randomized controlled clinical trials are needed in order to establish optimal clinical feeding protocols for preterm extremely ELBW infants undergoing non-invasive respiratory support.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Amendolia, B. et al. Feeding tolerance in preterm infants on noninvasive respiratory support. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 28, 300–304 (2014).

Weeks, C. L., Marino, L. V. & Johnson, M. J. A systematic review of the definitions and prevalence of feeding intolerance in preterm infants. Clin. Nutr. 40 (11), 5576–5586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2021.09.010 (2021). Epub 2021 Sep 17. PMID: 34656954.

Mehler, K. et al. Outcome of extremely low gestational age newborns after introduction of a revised protocol to assist preterm infants in their transition to extrauterine life. Acta Paediatr. Oslo Nor. 1992. 101, 1232–1239 (2012).

Jang, W. et al. Artificial Intelligence-Driven respiratory distress syndrome prediction for very low birth weight infants: Korean multicenter prospective cohort study. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e47612. https://doi.org/10.2196/47612 (2023). PMID: 37428525; PMCID: PMC10366668.3.

Sweet, D. G. et al. European consensus guidelines on the management of respiratory distress syndrome – 2019 update. Neonatology 115 (4), 432–450. https://doi.org/10.1159/000499361 (2019).

Fanaro, S. Feeding intolerance in the preterm infant. Early Hum. Dev. 89 (Suppl 2), S13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.07.013 (2013). Epub 2013 Aug 17. PMID: 23962482.

Patel, P. & Bhatia, J. Total parenteral nutrition for the very low birth weight infant. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 22, 2–7 (2017).

Chitale, R. et al. Early enteral feeding for preterm or low birth weight infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 150(Suppl 1):e2022057092E. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057092E. PMID: 35921673.

Bozzetti, V., De Angelis, C. & Tagliabue, P. E. Nutritional approach to preterm infants on noninvasive ventilation: an update. Nutrition 37, 14–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2016.12.010 (2017). Epub 2016 Dec 27. PMID: 28359356.

Embleton, N. D. et al. Enteral nutrition in preterm infants (2022): A position paper from the ESPGHAN committee on nutrition and invited experts. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 76 (2), 248–268 (2023).

Dollberg, G. & Dollberg, S. Fetal growth curves. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 8 (7), 518 (2006). PMID: 16889178.

Papile, L. A., Burstein, J., Burstein, R. & Koffler, H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 Gm. J. Pediatr. 92 (4), 529–534 (1978).

Bell, M. J. et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann. Surg. 187 (1), 1–7 (1978).

Shukla, V. V. & Ambalavanan, N. Recent advances in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Indian J. Pediatr. 88 (7), 690–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-021-03766-w (2021). Epub 2021 May 20. PMID: 34018135.

Rocha, G., Guimarães, H. & Pereira-da-Silva, L. The role of nutrition in the prevention and management of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: A literature review and clinical approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (12), 6245. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126245 (2021). PMID: 34207732; PMCID: PMC8296089.

Hwang, J. S. & Rehan, V. K. Recent advances in bronchopulmonary dysplasia: pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment. Lung 196 (2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-018-0084-z (2018). Epub 2018 Jan 27. PMID: 29374791; PMCID: PMC5856637.

Chen, J. et al. The comparison of HHHFNC and NCPAP in extremely Low-Birth-Weight preterm infants after extubation: A Single-Center randomized controlled trial. Front. Pediatr. 8, 250. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.00250 (2020). PMID: 32670991; PMCID: PMC7332541.

Luo, K., Huang, Y., Xiong, T. & Tang, J. High-flow nasal cannula versus continuous positive airway pressure in primary respiratory support for preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pediatr. 10, 980024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.980024 (2022). PMID: 36479290; PMCID: PMC9720183.

Seth, S., Saha, B., Saha, A. K., Mukherjee, S. & Hazra, A. Nasal HFOV versus nasal IPPV as a post-extubation respiratory support in preterm infants-a randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Pediatr. 180 (10), 3151–3160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04084-1 (2021). Epub 2021 Apr 23. PMID: 33890156; PMCID: PMC8062142.

Yuan, G., Liu, H., Wu, Z. & Chen, X. Evaluation of three non-invasive ventilation modes after extubation in the treatment of preterm infants with severe respiratory distress syndrome. J Perinatol. 42(9), 1238–1243. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-022-01461-y. Epub 2022 Aug 11. PMID: 35953535.

Cresi, F. et al. Effect of nasal continuous positive airway pressure vs heated humidified High-Flow nasal cannula on feeding intolerance in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome: the ENTARES randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 6 (7), e2323052. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.23052 (2023). PMID: 37436750; PMCID: PMC10339152.

Fang, S., Kempley, S. T. & Gamsu, H. R. Prediction of early tolerance to enteral feeding in preterm infants by measurement of superior mesenteric artery blood flow velocity. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 85 (1), F42–F45. https://doi.org/10.1136/fn.85.1.f42 (2001). PMID: 11420321; PMCID: PMC1721289.

Neu, J. & Zhang, L. Feeding intolerance in very-low-birthweight infants: what is it and what can we do about it? Acta. Paediatr. Suppl. 94(449), 93 – 9. (2005). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb02162.x. PMID: 16214773.

Havranek, T., Madramootoo, C. & Carver, J. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure affects pre- and postprandial intestinal blood flow velocity in preterm infants. J. Perinatol. 27, 704–708. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211808 (2007).

Gounaris, A. et al. Gastric emptying in very-low-birth-weight infants treated with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. J. Pediatr. 145(4), 508 – 10. (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.030. PMID: 15480376.

Cordero González, G. et al. Management of abdominal distension in the preterm infant with noninvasive ventilation: Comparison of cenit versus 2x1 technique for the utilization of feeding tube. J. Neonatal. Perinatal. Med. 13(3), 367–372. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3233/NPM-190301. PMID: 31929124.

Jaile, J. C. et al. Benign gaseous distension of the bowel in premature infants treated with nasal continuous airway pressure: a study of contributing factors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 158, 125–7.10.1002/14651858.CD001241.pub8. PMID: 34427330; PMCID: PMC8407506. (1992).

Öktem, A., Yiğit, Ş., Çelik, H. T. & Yurdakök, M. Comparison of four different non-invasive respiratory support techniques as primary respiratory support in preterm infants. Turk J Pediatr. 63(1), 23–30. (2021). https://doi.org/10.24953/turkjped.2021.01.003. PMID: 33686823.

Cummings, J. J., Polin, R. A. & Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics. Noninvasive respiratory support. Pediatrics 137(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3758 (2016).

Zhu, X. et al. Noninvasive High-Frequency oscillatory ventilation vs nasal continuous positive airway pressure vs nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation as postextubation support for preterm neonates in china: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 176 (6), 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0710 (2022). PMID: 35467744; PMCID: PMC9039831.

Jain, A. et al. (May 17, 2022) noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV)-Associated expanding hiatal hernia causing pulmonary tamponade: A case report on unusual complication of NIPPV. Cureus 14(5): e25069. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.25069

Hodgson, K. A., Wilkinson, D., De Paoli, A. G. & Manley, B. J. Nasal high flow therapy for primary respiratory support in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5 (5), CD006405. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006405.pub4 (2023).

Meister, A. L., Doheny, K. K. & Travagli, R. A. Necrotizing enterocolitis: It’s not all in the gut. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 245(2), 85–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1535370219891971. Epub 2019 Dec 6. PMID: 31810384; PMCID: PMC7016421. (2020).

Alshaikh, B., Dharel, D., Yusuf, K. & Singhal, N. Early total enteral feeding in stable preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 34 (9), 1479–1486 (2021). Epub 2019 Jul 9. PMID: 31248308.

Kwok, T. C., Dorling, J. & Gale, C. Early enteral feeding in preterm infants. Semin Perinatol. 43 (7), 151159. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2019.06.007 (2019). Epub 2019 Jul 24. PMID: 31443906.

Riskin, A. et al. The impact of routine evaluation of gastric residual volumes on the time to achieve full enteral feeding in preterm infants. J. Pediatr. 189, 128–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.05.054 (2017). Epub 2017 Jun 16. PMID: 28625498.

Oddie, S. J., Young, L. & McGuire, W. Slow advancement of enteral feed volumes to prevent necrotising Enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8 (8), CD001241 (2021).

Patton, L., de la Cruz, D. & Neu, J. Gastrointestinal and feeding issues for infants < 25 weeks of gestation. Semin Perinatol. 46 (1), 151546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151546 (2022). Epub 2021 Nov 10. PMID: 34920883.

Konnikova, Y. et al. Late enteral feedings are associated with intestinal inflammation and adverse neonatal outcomes. PLoS One. 10 (7), e0132924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132924 (2015). PMID: 26172126; PMCID: PMC4501691.

Wemhöner, A., Ortner, D., Tschirch, E., Strasak, A. & Rüdiger, M. Nutrition of preterm infants in relation to bronchopulmonary dysplasia. BMC Pulm Med. 11, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-11-7 (2011). PMID: 21291563; PMCID: PMC3040142.

Lin, B. et al. Enteral feeding/total fluid intake ratio is associated with risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm infants. Front. Pediatr. 10, 899785. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.899785 (2022). PMID: 35712615; PMCID: PMC9194508.

Thoene, M. & Anderson-Berry, A. Early enteral feeding in preterm infants: A narrative review of the nutritional, metabolic, and developmental benefits. Nutrients 13 (7), 2289. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072289 (2021). PMID: 34371799; PMCID: PMC8308411.

Bonnar, K. & Fraser, D. Extrauterine Growth Restriction in Low Birth Weight Infants. Neonatal Netw. 38(1), 27–33. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1891/0730-0832.38.1.27. PMID: 30679253.

Kim, M. J. Enteral nutrition for optimal growth in preterm infants. Korean J. Pediatr. 59 (12), 466–470. https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2016.59.12.466 (2016). Epub 2016 Dec 31. PMID: 28194211; PMCID: PMC5300910.

Behnke, J. et al. Compatibility of rapid enteral feeding advances and noninvasive ventilation in preterm infants-An observational study. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 57 (5), 1117–1126. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.25868 (2022). Epub 2022 Mar 9. PMID: 35191216.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made significant contributions to the conception, design, execution, and interpretation of this study.S.S., D.M., and J.H. contributed to the study design, data collection, and analysis.R.M. was responsible for statistical analysis and data interpretation.R.L. and H.M.L. contributed to the clinical interpretation and discussion of the findings.H.M.L. supervised the study and provided critical revisions to the manuscript.All authors were involved in drafting and critically reviewing the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.The authors affirm that they have read and approved the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soffer, S., Mandel, D., Herzlich, J. et al. Associated factors and clinical outcomes of feeding intolerance in preterm extremely low birthweight infants. Sci Rep 15, 28189 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14386-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14386-1