Abstract

In the evaluation of myocardial infarction, cardiac MRI remains problematic in terms of sensitivity and quantitativeness. Thus, we sought to delineate pathological microstructural alterations across temporal phases subsequent to myocardial ischemia–reperfusion (IR) injury utilizing q-space imaging (QSI), an advanced diffusion imaging methodology proficient in assessing the non-Gaussian diffusion patterns of molecules. Rats were subjected to IR injury, and infarct was evaluated at 2, 7, and 30 days via histopathological staining and MRI using a 9.4‐Tesla system. QSI was performed with gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) for comparative assessment. Correlation coefficients among images were computed at each level of the left ventricular short-axis cross-section to juxtapose the infarct dimensions and morphology. Axial diffusivity of the kurtosis maps at 2, 7, and 30 days revealed substantial correlations with the hyperintense areas noted on T1WI (R2 = 0.885, 0.947, and 0.929, respectively). Furthermore, a strong correlation was noted with the transmural extent of infarction. Even in the absence of gadolinium contrast, the high-intensity regions delineated by QSI were concordant with the extent of pathological infarction (R2 = 0.977). These findings highlight the capability of QSI in identifying pathological changes at the infarct site, independent of gadolinium contrast media and irrespective of the temporal phase subsequent to the IR onset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has assumed an increasingly pivotal role in the management of myocardial infarction (MI) and associated complications, especially ischemia–reperfusion (IR) injury. The ability to precisely quantify myocardial infarct size using MRI is essential for optimizing patient management and predicting treatment outcomes. Among the various MRI techniques, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) of contrast-enhanced MRI is widely used owing to its high diagnostic accuracy1,2,3. Nevertheless, LGE utilization is fraught with challenges, including the risk of gadolinium deposition, empirical determination of gadolinium dosage, reliance on the accurate selection of inversion time, and inconsistency in defining the infarct area2,4,5,6. Moreover, while LGE reflects expansion of the extracellular matrix (ECM), this is not a phenomenon specific to MI and thus lacks disease specificity1. Hence, the exploration of contrast-independent methodologies for assessing infarcted myocardium is critical. Although T1 and T2 mapping are gaining attention as potential alternatives or complementary techniques to LGE in the assessment of MI, current evidence remains limited, even in studies conducted at major MRI centers7. Challenges remain in terms of standardizing acquisition and analysis protocols across institutions, as well as the need to improve diagnostic sensitivity and specificity in diffuse pathological settings.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) provides visualization of the degree of water molecule diffusion without the requirement of contrast media, based on the assumption of a Gaussian distribution in water molecule diffusion. Conventional DWI is useful for discerning gross proton diffusion and is widely employed to assess alterations in tissue properties in acute cerebral infarction. DWI has been applied in the cardiac field to detect water diffusion in myocardial pathologies, such as abscesses, tumors, and cardiac cysts8,9,10. However, in conditions such as IR injury—where myocardial necrosis is accompanied by inflammatory cell infiltration and complex cellular morphological changes leading to restricted diffusion—the utility of DWI may be limited11. Q-space imaging (QSI) is an imaging modality that integrates multiple magnetic resonance (MR) signals from identical planes under varied bipolar gradient field effects (b-values), thus deriving a probability density distribution devoid of Gaussian assumptions12. In this respect, QSI holds an advantage over DWI, as it does not rely on the assumption of Gaussian-distributed water diffusion. QSI has been shown to effectively capture subtle physiological changes in various tissues, including the brain, intervertebral discs, and skeletal muscles13,14,15,16. Given that IR injury induces complex structural alterations that modify the restriction of water diffusion within tissues, QSI appears to be a superior technique for characterizing such changes.

We posited that QSI could elucidate myocardial microstructural alterations across the temporal phases after myocardial IR injury. Leveraging ex vivo cardiac MRI in a rat model of IR injury, QSI was juxtaposed with conventional standard gadolinium contrast-enhanced MRI and histopathological tissue staining for comprehensive evaluation.

Results

Generation of QSI in ex vivo model of myocardial IR injury

In the ex vivo model of myocardial IR injury, a cohort of 30 rats underwent cardiac MRI experiment (Fig. 1). Among these, 24 rats were subjected to the contrast-enhanced MRI protocol, while the remaining six underwent the non-contrast-enhanced protocol. Within the group undergoing contrast MRI, 18 rats were randomly allocated to the IR surgery group, while the remaining six were assigned to the sham surgery group (Fig. 1A). Among the six rats that underwent the non-contrast MRI protocol, four underwent IR surgery and two underwent sham surgery (Fig. 1B). The hearts were excised following euthanasia, and MRI scans were performed on days 2, 7, and 30 postoperatively.

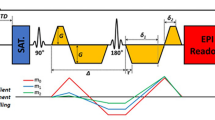

QSI data were generated by varying the b-value of the diffusion-weighted image, and Fourier transformation was used to analyze the data (Fig. 2A, Table 1). Representative images of the IR-injured and sham-operated hearts without contrast agents are shown in Fig. 2B. Among the numerous QSI parameters, the axial diffusivity of the kurtosis map demonstrated a distinct demarcation between high- and low-intensity areas compared with T1-weighted imaging (T1WI). Figure S1 illustrates each parameter of the probability displacement function (PDF) and diffusion tensor anisotropy. Kurtosis, probability at zero displacement (ZP), and full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) were used to quantify the non-Gaussian distribution of the PDF (Fig. S1A, B, and C, respectively). For each setting, anisotropy was quantified as the mean anisotropy in all directions (mean anisotropy), axial component (axial anisotropy), radial component (radial anisotropy), principal direction (L1), secondary direction (L2), third direction (L3), and fractional anisotropy (FA). The axial diffusivity of the kurtosis map showed the most visually discernible contrast between the infarcted and remote areas (Fig. S1A). Consequently, we assessed the axial diffusivity of the kurtosis map for infarct size estimation using QSI.

Representative q-space imaging of rat ex-vivo heart after ischemia–reperfusion. (A) Conceptual illustration of the QSI generation. First, DWI of the ex-vivo heart were obtained with 10 steps of b-values ranging from 0 to 4500 s/mm2. Then, QSI was generated through post-processing analysis, primarily by Fourier transformation. The AD of a kurtosis map is illustrated as a representative QSI image. (B) Representative images of the QSI compared with T1WI. Left: IR-injured heart; right: sham operated heart. Scale bar = 1 mm. (C) Representative histopathology (H&E stain) of the ex-vivo heart at the infarct (left) and remote area (right). The heart was harvested two days after IR. Black bars reflect the transverse diameter of the cardiomyocytes. Scale bar = 10 μm. (D) Comparison of the AD of kurtosis at the infarct and remote area of the ex-vivo heart. (E) Correlation analysis of the transverse cell diameter measured by histopathology and AD of kurtosis. AD, axial diffusivity; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; IR, ischemia reperfusion; QSI, q-space imaging; T1WI, T1-weighted imaging.

All ex vivo myocardial specimens subjected to MRI were sectioned for the evaluation of cellular microscopic morphology using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. 2C). H&E staining showed cell death and inflammatory cell infiltration in infarcted lesions compared to remote lesions. The signal intensity in the infarcted lesions was higher than that in the remote lesions when evaluated using the axial diffusivity of the kurtosis map (Fig. 2D). The short transverse diameter of the cells was compared with the kurtosis map signal intensity to assess the impact of restricted proton diffusion on the QSI signal intensity. A negative correlation was noted between the short diameter of the cells and the QSI value, which was attributable to restricted diffusion (Fig. 2E).

Time-series QSI after myocardial IR injury

The axial diffusivity of the kurtosis maps was juxtaposed with gadolinium-enhanced T1WI and histopathological findings at 2, 7, and 30 days post IR (Fig. 3A–C). To quantitatively assess the MI extent across modalities, the percentage of infarcted area relative to the total left ventricular area was computed (size analysis), along with the percentage of infarcted area relative to the total sector area of the infarcted left ventricle (shape analysis; transmural extent). Figure 4 illustrates the quantification method of the infarct size and shape after cardiac MRI (also refer to “Pathology and Imaging Comparison” in the Methods section).

Time-series comparison of histopathology and MRI of infarcted lesions with gadolinium enhancement. (A–C) Time-series comparison of histopathology (Masson’s trichrome stain; left), T1- weighted imaging(middle), and AD of the kurtosis map (right) at days 2 (A), 7 (B), and 30 (C) after cardiac ischemia–reperfusion (IR) injury. The red rectangles highlight representative images at each time point. The yellow dotted area indicates infarcted lesion of the IR-injured heart measured by each modality. Scale bar = 1 mm. (D–F) Correlation analysis of T1WI and AD of kurtosis map at days 2 (D), 7 (E), and 30 (F) after cardiac IR injury. The percentage of infarct area compared to the entire left ventricular size (i.e. infarct size; above) and the percentage of the infarct area compared to the total sectored left ventricular size (i.e. transmural extent; below) at each time point were evaluated. AD, axial diffusivity; IR, ischemia–reperfusion; Kurtosis (Gad+): axial diffusivity of kurtosis map (with gadolinium enhancement); T1WI (Gad+): T1-weighted imaging (with gadolinium enhancement).

Quantification of the infarct size and shape after cardiac MRI. (A) Quantitative size analysis of the rat heart. The infarct size was measured as the percentage of infarct area compared to the total left ventricular area. (B) Quantitative shape analysis (i.e., transmural extent) of the rat heart. Infarct shape was measured using the percentage of the infarcted area compared to the total area of the infarcted left ventricle. (C) Example case of the rat heart with the same infarct size, but different shapes. The left figure shows a thin and long subendocardial infarction, while the right figure demonstrates a thick and short, fully transmural myocardial infarction.

The high-intensity area of LGE on T1WI showed a significant correlation with the kurtosis maps at 2 days post-IR (size R2 = 0.885, shape R2 = 0.875), 7 days post-IR (size R2 = 0.947, shape R2 = 0.906), and 30 days post-IR (size R2 = 0.929, shape R2 = 0.716) (Fig. 3D–F). Bland–Altman analysis further showed a strong agreement between the T1WI and kurtosis maps at each time point (Fig. S2A,D,G).

To validate the congruence between the MRI findings and actual pathological changes, both T1WI and kurtosis maps were compared with the histopathological infarct areas (Fig. 3A–C, Fig. S3). Two days post IR, the myocardial wall exhibited edematous thickening, as demonstrated by H&E staining, with LGE evident at the site of ischemic injury (Fig. 2C, 3A, 5A). T1WI showed a high-intensity area consistent with the pathological findings (size R2 = 0.951, shape R2 = 0.911; Fig. S3A), as did the high-signal region of the kurtosis map (size R2 = 0.973, shape R2 = 0.851; Fig. S3A). Seven days post IR, the edematous changes subsided and myocardial tissue fibrosis was observed with Masson’s trichrome staining (Fig. 3B, 5B). Gadolinium-enhanced T1WI corresponded to the injured regions (size R2 = 0.951; shape R2 = 0.952; Fig. S3B), similar to the high-intensity region in the kurtosis map (size R2 = 0.954; shape R2 = 0.906; Fig. S3B). By day 30, fibrosis in the infarcted area manifested as a distinct blue dye in Masson’s trichrome staining and thinning of the left ventricular wall (Fig. 3C, 5C). Both gadolinium-delayed contrast T1WI and kurtosis maps demonstrated high signal intensity around this region of thinning, consistent with the fibrotic injured areas on pathology (T1WI vs. pathology: size R2 = 0.953, shape R2 = 0.821; kurtosis map vs. pathology: size R2 = 0.959, shape R2 = 0.791; Fig. S3C). Bland–Altman analysis further underscored the robust agreement between pathology and T1WI (Fig. S2B, E, H), as well as between pathology and kurtosis maps (Fig. S2C, F, I) at each time point. These findings suggest ex vivo QSI, particularly axial diffusion of kurtosis maps, is an alternative strategy for evaluating cardiac infarct size that complements gadolinium-enhanced T1WI.

Representative histopathology of the heart after ischemia–reperfusion injury. (A–C) High power images of histopathology at days 2 (A), 7 (B), and 30 (C) after cardiac IR injury. (A) Masson’s trichrome staining. (B, C) Left: hematoxylin and eosin staining; Right: Masson’s trichrome staining. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Validation of the utility of QSI in gadolinium non-contrast MRI

To ascertain the efficacy of QSI in evaluating myocardial infarction even in the absence of gadolinium contrast, we compared kurtosis maps, T1WI, and pathological findings using non-enhanced IR-injured hearts on day 2 as a representative time point (Fig. 6A). In contrast to gadolinium-enhanced MRI, non-enhanced MRI exhibited a lack of hyperintense areas on T1WI and a substantially lower correlation with lesion location (size R2 = 0.510, shape R2 = 0.004; Fig. 6B). Conversely, kurtosis maps showed a robust correlation with both size and shape with the infarct area depicted on pathology, irrespective of the gadolinium contrast (size R2 = 0.977, shape R2 = 0.919; Fig. 6B). Bland–Altman analysis further illustrated a favorable agreement between the results (Fig. S4).

Comparison of histopathology and MRI without gadolinium enhancement. (A) Comparison of histopathology (Masson’s trichrome stain; left), T1WI (middle), and AD of the kurtosis map (right) at day 2 after cardiac IR injury. The red rectangle indicates representative images. Within this highlighted row of images, the yellow dotted area indicates infarcted lesion of the IR-injured heart measured by each modality. The pink dotted area indicates a hypointensity region of T1WI. Scale bar = 1 mm. (B) Correlation analysis of the pathological infarct size (above) and shape (below) compared to those with T1WI and AD of the kurtosis map two days after cardiac IR injury. AD, axial diffusivity; IR, ischemia reperfusion; Kurtosis(Gad-), axial diffusivity of kurtosis map (without gadolinium enhancement); T1WI (Gad-), T1-weighted imaging (without gadolinium enhancement).

To assess data reproducibility, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were determined using kurtosis maps. The ICCs for the interobserver and intraobserver measurements of the kurtosis maps were 0.997 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.987–0.999) and 0.995 (95% CI: 0.980–0.999), respectively.

Discussion

QSI was sensitive in delineating MI lesions

In this study, a strong correlation was found between the regions exhibiting alterations in QSI signals following IR and those exhibiting histological changes via Masson’s trichrome staining, both in terms of area size and shape. Despite the immense potential of QSI in detecting microstructural changes with heightened sensitivity, its application to rodent hearts has been relatively limited, owing to a rapid heart rate and the technical difficulty of electrocardiogram (ECG) gating. For instance, previous studies have demonstrated efficacy of QSI in detecting hypertrophied myocardium with remarkable sensitivity using kurtosis maps ex vivo in mouse models of transverse aortic constriction17. Building on these findings, we successfully expanded the utility of QSI to IR-injured hearts while preserving high-quality lesion imaging.

Mechanism by which the QSI detects infarct lesions

Unlike DWI, which presupposes a Gaussian distribution of proton diffusion patterns, QSI can discern microscopic pathophysiological phenomena by quantifying restricted diffusion. Subsequently, any histological anomaly, including compartmentalized protons, cell size variations, the presence of cellular organelles, hemorrhage (and associated iron deposition), and inflammatory cell infiltration, can influence the signal values of the diffusion anisotropy maps18. Within the ischemic region, the degree of cellular injury is not uniform; the ischemic core exhibits more severe disruption of the cellular architecture than the peri-ischemic border zone19. While DWI can detect relatively large structural alterations, it is less sensitive to subtle microstructural changes on the order of a few micrometers and may fail to capture changes in the peri-ischemic border zone20. In contrast, QSI enables quantification of restricted diffusion, and thus allows for high-sensitivity detection of ischemic tissue, including peri-infarct regions.

Although QSI shows a high sensitivity in identifying microstructural changes, further exploration of its lesion specificity remains necessary. Predicting tissue pathology based solely on high or low signal values for each QSI parameter is challenging. Molecular diffusion dynamics are intricately governed by the intracellular and extracellular compartments, and the predominant diffusion type—free, hindered, or restricted—shapes the observed signal characteristics15. Given its reliance on detecting microstructural alterations in water diffusion, QSI may be relatively insensitive to biological processes that do not involve overt structural changes, such as early inflammation or subtle cell migration.

In skeletal muscle imaging research, a larger cell size of the tibialis anterior muscle displayed a high FWHM and low kurtosis, whereas a smaller cell size of the soleus muscle revealed a low FWHM and high kurtosis16. In our study, histopathological examination of the remote myocardium revealed relatively large cell sizes, corresponding to areas with high signal intensity in the FWHM and low signal intensity in the kurtosis map (Fig. 2C,D, 5C). Conversely, in the infarcted area, where cell sizes tended to be smaller owing to apoptosis, necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, and red blood cell leakage, the signal intensity was low in the FWHM and high in the kurtosis map (Fig. 2C–E, S1A,C).

The MRI system used in this study operates at the highest spatial resolution currently achievable using existing hardware technology. In other words, the voxel size was minimized to the practical limit. This resolution was sufficient to detect tissue damage induced by IR injury at the cellular level. However, to improve disease sensitivity further, it is necessary to detect restricted diffusion at the subcellular level, which requires even smaller voxel sizes. To achieve a higher spatial resolution (i.e., to reduce the voxel size), several approaches can be considered, including further narrowing of the field of view, the use of higher magnetic field strengths to enhance signal sensitivity, and the development of smaller, high-sensitivity radiofrequency coils. With improved QSI resolution, not only can infarct sites be detected during the acute phase of IR, but this modality may also be applied in numerous non-ischemic cardiomyopathies.

Although we attempted QSI using a clinical scanner, the image quality was insufficient for diagnostic interpretation (data not shown). For QSI to be applicable in clinical settings, several challenges must be addressed, including a prolonged acquisition time (approximately 10 min) and motion artifacts caused by both respiratory and cardiac motion. Overcoming these limitations is essential for clinical implementation of QSI. Furthermore, to facilitate clinical translation, enhancing the diagnostic capabilities through the integration of multiple imaging conditions, such as conventional DWI and T2-weighted images, should be considered.

Advantages of QSI

The primary advantage of QSI is its ability to accurately identify pathological ischemic infarct areas without the use of contrast agents. Conventional approaches involve detecting LGE on T1-weighted images to assess the MI areas. However, gadolinium enhancement carries the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) in patients with compromised kidney function, rendering it contraindicatory for such patients4. Moreover, the lack of standardized evaluation methods for LGE can led to inadequate quantification of the infarct area21. Conversely, QSI offers the potential for uniform and quantitative assessment of MI areas without relying on contrast agents.

In this study, we examined the pathophysiological process from the acute phase (day 2) to the chronic phase (day 30) of IR injury. Acute edema is caused by increased cell swelling and interstitial edema, secondary to reactive hyperemia and leakage from damaged capillaries when hydrostatic pressure is restored during reperfusion22,23. In the chronic phase, edema disappeared and fibrosis was observed, indicative of the reparative process. Throughout these dynamic phases of IR injury, QSI demonstrated a robust capability for detecting the affected region, both in the acute and chronic phases.

Although LGE reflects ECM expansion, this phenomenon is observed in various pathological conditions and thus lacks disease specificity. In contrast, QSI is capable not only of detecting ECM expansion, but also of capturing increased mobility of water molecules resulting from cell membrane damage. For example, in pathological conditions such as early-stage neural injury, QSI has been shown to detect increased water diffusivity due to the damage of cell membranes and axons24,25. These findings suggest that, in the context of IR, QSI may offer greater sensitivity than gadolinium-enhanced MRI.

In the diagnosis of various cardiomyopathies, non-contrast T1 mapping has emerged as a valuable tool, particularly in patients unable to undergo gadolinium enhancement, as shown in numerous studies26,27,28. Nonetheless, T1 mapping encounters challenges related to varying reference values across facilities, potentially compromising lesion detection sensitivity26. QSI may be superior to T1 mapping for detecting certain cardiomyopathies in which microstructural alterations are the primary pathological features, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or early stage cardiac sarcoidosis29,30,31. Even in phases where T1 mapping fails to reveal abnormalities, QSI may be capable of detecting restricted water diffusion or microstructural disorganization caused by sarcomeric abnormalities or granulomatous proliferation.

In vivo imaging with cardiac and respiratory synchronization is imperative for the clinical application of QSI. Although QSI requires prolonged signal acquisition times, shorter acquisition times are preferable in clinical settings. Thus far, successful clinical implementation of QSI has been achieved by reducing the number of b-value steps within an acceptable acquisition time (9 b-values, typically < 8 min) without compromising the characteristics of the PDF curve13,32. However, in order to introduce cardiac QSI in clinical practice, it is necessary to improve the ECG gating system. The development of stimulated echo (STE)-QSI system can facilitate more reliable ECG synchronization. Furthermore, if the extent of structural alterations detectable by QSI can be clarified for different cardiac pathologies and disease stages, it may be possible to shorten the acquisition time by narrowing the range of b-values or employing two-compartment analysis.

Study limitations

Despite the significant findings of the study, certain limits should be acknowledged, including the use of ex vivo hearts excised from rats. Ex vivo heart MRI allows for superior spatial resolution and eliminates motion artifacts, but lacks physiological blood perfusion, which can significantly alter diffusion and relaxation properties33. Perfusion plays a critical role in maintaining the tissue hydration, metabolic status, and imaging contrast34. Therefore, findings from ex vivo imaging must be interpreted with caution when extrapolating to in vivo conditions. Moreover, tissue temperature decreases to room temperature upon removal from the body, in contrast to the constant body temperature maintained in living organisms35. This temperature differential also influences the diffusion profiles, with approximately 90% of the changes in diffusivity between in vivo and ex vivo conditions attributable to temperature alterations, whereas the remaining 10% stems from factors such as tissue dehydration36. LGE imaging was not performed in vivo because of the technical difficulties associated with ECG and respiratory gating. To circumvent these issues, the heart was harvested after gadolinium administration and imaged ex vivo by MRI. Although gadolinium contrast enhanced lesion visualization in T1WI, it did not significantly affect disease visualization in QSI.

Additionally, this study exclusively evaluated IR lesions. Conventionally, the post-IR myocardium is comprised of reversibly ischemic and irreversibly infarcted areas. Experimental distinction between these areas can be achieved using triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining37. However, due to the necessity of creating paraffin sections in this study, TTC staining could not be performed. Consequently, the evaluation of MI relied primarily on histopathological diagnosis. T1 mapping, T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), and LGE have shown utility in the detection of reversible ischemia and irreversible infarction38,39,40. Although there are many instances of stroke following MI/IR, no studies to date have directly compared the difference in diffusion properties between these two states in heart tissue. At the cellular level, intact plasma membranes in living cells restrict water diffusion, yielding lower apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values, whereas cells undergoing apoptosis or necrosis show increased ADC owing to membrane disintegration, which reduces barriers to molecular movement41. Therefore, restricted diffusion measured by QSI may serve as a potential marker to distinguish between these two cellular states.

In conclusion, the comparison of ex vivo cardiac MRI with gadolinium contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images and pathological sections underscores the efficacy of QSI. By employing diffusion-weighted images and a restricted diffusion model without assuming a Gaussian distribution, QSI is posited as a superior method for precisely delineating the infarct region following myocardial IR. Additionally, QSI can detect infarcted regions even in the absence of gadolinium administration. These findings emphasize the potential of QSI in assessing myocardial IR.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the Animal Experimentation Guidelines of Keio University School of Medicine and approved by the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of Keio University (approval number: 12094). All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). Male Wistar rats (12–14 weeks old; body weight 280–320 g) were used in the experiments (Sankyo Labo Service Corporation, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Animals had ad libitum access to laboratory chow and water.

Rat model of myocardial ischemia–reperfusion

Rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of dexmedetomidine hydrochloride (ZENOAQ, Fukushima, Japan), midazolam (SANDOZ, Tokyo, Japan), and butorphanol tartrate (Meiji Seika Pharma, Tokyo, Japan) (0.375 mg/kg, 2.0 mg/kg, and 2.5 mg/kg, respectively). Animals were intubated and mechanically ventilated with room air (15 mL/kg, 60 breaths/min). A Power Lab system (PowerLab System, LabChart; AD Instruments, Bella Vista, NSW, Australia) was used to continuously record ECG, heart rate, and body temperature. ECGs were recorded using needle electrodes. Body temperature was maintained within 36–37 °C using a heating pad and lamp. With the animal in the lateral position, the left third rib was partially removed to expose the heart. A 5-0 silk suture was passed around the left coronary artery, and both ends were guided through a polyethylene tube to create a snare for subsequent occlusion. The snare was used to occlude the left coronary artery and induce myocardial ischemia. The ischemia duration was set to 30 min, as previous ischemia–reperfusion injury studies have demonstrated this period provides an appropriate balance between survival rate and infarct size42,43,44. Following this time period, the snare was released to reperfuse the myocardium. After reperfusion, the chest was closed and atipamezole hydrochloride (1.8 mg/kg; ZENOAQ) was administered to antagonize the anesthetics. The rats were extubated and weaned from the ventilator after awakening.

Cardiac surgeries were conducted in 30 rodents: IR injury group (n = 24) and sham operation group (n = 6). No intraoperative deaths occurred in any of the rodents. There were three cases of sudden cardiac death between the date of cardiac surgery and the date of MRI (all three cases were in the IR injury group). MRI and pathological evaluations were performed in the remaining 27 animals (Fig. 1).

Gadolinium contrast administration and perfusion fixation of the heart

The rats were re-anesthetized intraperitoneally, re-intubated, and ventilated on the day of MRI (2–30 days after IR). A polyethylene catheter (PE50; Natsume, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted via the femoral vein, as previously reported45 Gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist; Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Wayne, NJ) was administered (0.6 mg/kg) via the catheter. The rats were placed in the right lateral supine position 10 min later, and the surgical site on the chest was reopened. The rats were euthanized by intravenous injection of dexmedetomidine hydrochloride and midazolam and systemically perfusion-fixed, followed by excision of the heart. Perfusion fixation of the myocardium was achieved by incising the right atrium and infusing a sufficient amount of PBS, followed by neutral-buffered formalin intracardially. The excised hearts were washed with PBS and immersed in a fluorinated inert liquid (Fluorinert, FC-72, 3M Japan, Japan). The container containing the excised heart was vibrated under negative pressure to prevent air bubbles from entering the cardiac cavity. MRI was performed as described below. After imaging, hearts were removed from the fluorinated inert liquid, washed with PBS, and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. The fixed hearts were embedded in paraffin and sectioned for histopathological analysis.

MRI protocol

At 2, 7, and 30 days after IR, the excised hearts were subjected to MRI using a 9.4-Tesla system (BioSpec 94/30; Bruker BioSpin, Ettlingen, Germany) equipped with a solenoid-type receiver coil (inner diameter of 28 mm; Takashima Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The excised heart specimen was positioned such that the short-axis plane of the heart was aligned parallel to the coronal plane of the scanner, and imaging was performed in the coronal orientation. Gadolinium-enhanced T1WI using fast low-angle shot (FLASH) and QSI using pulsed gradient spin echo of the simple monopolar diffusion gradient (PGSE) type were performed. Both pulse sequences were obtained as single k-space lines per echo. First, scout axial, sagittal, and coronal images were obtained. These images were then used to adjust the axial images for analysis. MRI systems can exhibit slight frequency shifts depending on the distance from the isocenter and configuration of the gradient fields. To minimize these variations and ensure reproducible measurements, all samples were positioned at a consistent angle during imaging. The sample temperature during the scan was controlled and maintained at 24 °C, similar to our previous DWI reports14,16. The detailed protocol parameters are listed in Table 1. The differences between DWI and QSI are summarized in Table S1.

Imaging analysis

An in-house program (developed in C++; Embarcadero Technologies, Inc., Austin, TX, USA) was used for QSI analyses. The non-Gaussian PDF of water diffusion was obtained by performing a Fourier transformation of the data based on Stejskal–Tanner diffusion preparation46. Detailed new diffusion values and their calculation procedures have been described previously14,16. Briefly, the PDF [P(R, Δ)] of distance, R, at a given time (Δ) is expressed by the following equation:

where D represents diffusion coefficient.

The PDF is considered to exhibit a Gaussian distribution if the measured object includes only one element. Conversely, if an object includes several elements, the PDF is considered to demonstrate a non-Gaussian distribution, reflecting the complexity of the measured object. An important theory in QSI is that the Fourier transformation of the signal decay with respect to the b-value provides the PDF for diffusion using multiple q-values14,16 (Fig. 1A). In this case, the q-value, which represents the horizontal axis, is defined as follows:

where γ represents the gyromagnetic ratio, δ represents the gradient length, G represents the intensity of gradient field pulse.

The FWHM (μm), kurtosis (a.u.) and probability at ZP maps were obtained. The shape of the PDF can be characterized by the FWHM, kurtosis, and ZP. Kurtosis values were calculated as follows:

where N is the number of data points (i.e., the number of b-value steps used), x is the probability value (a.u.) obtained from the PDF, \(\overline{x }\) is the sample mean, and SD is the standard deviation of the x values.

For each PDF, the anisotropy of the diffusion tensor is calculated as the mean anisotropy of all directions (mean anisotropy), the axial component (axial anisotropy), the radial component (radial anisotropy), the most principal eigenvector primary (principal direction of diffusion tensor) anisotropy (L1), secondary anisotropy (L2), and tertiary anisotropy (L3), and fractional anisotropy (FA) component. FA was calculated using the following formula:

where mqsi represents the mean anisotropy value.

Histopathological analysis

MR and histopathological images were obtained from the same rat heart. Within 3 days of MRI, the harvested hearts were immersed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections with a 4-μm thickness were cut for pathological analysis. Sections were stained with H&E (nuclei stained with hematoxylin) and Masson’s trichrome. The slides were mounted and visualized using a digital camera (BZ-9000; BIOREVO; Keyence, Osaka, Japan). Imaging results were obtained using BZ-H1C software (Keyence).

Pathology and imaging comparison

In this study, the selection of infarcted and non-infarcted regions was based on a comprehensive pathological assessment using both H&E and Masson’s trichrome staining. Axial images at each level of the left ventricle were used. For both MRI and histology, continuous cross-sectional imaging and tissue sectioning were performed at 1 mm intervals from the apex to the base of the heart along planes perpendicular to the long axis. This allowed for the precise matching of each MRI short-axis slice with the corresponding histological section. Image analysis was carried out according to a previous report47. Briefly, the infarcted area was quantified by size and shape comparisons. A size comparison was performed by calculating the ratio of the area of the entire left ventricle to that of the abnormal lesion area. Shape comparison was performed by calculating the ratio of the infarcted left ventricular segment to the area of the abnormal lesion (which reflects the transluminal extent of the infarction) (Fig. 4). For shape analysis, sector selection was based on expert assessment of the infarct/non-infarct boundaries in both the MRI and histological sections. In cases where the boundary was unclear or difficult to determine, a demarcation line corresponding to the largest extent of infarction was adopted. The imaging values were measured using ImageJ 1.48v software (available at the rsbweb. nih.gov/ij/; National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

We used an axial slice of each level of the left ventricle for both histological and MRI images. Data are presented as mean ± standard error. The mean signal intensities of the infarcted and remote regions of the QSI (kurtosis map) were compared using paired t-tests. Linear correlation analysis was used to compare the relationships between the abnormal regions on pathology and MRI. Multiple image slices were analyzed for each subject, therefore, a linear mixed-model regression analysis for repeated measures was performed for each subject. Linear regression and analysis of covariance were used to assess whether the 95% CIs of the regression coefficients included the line of identity. To assess the agreement between MRI and pathological measurements, Bland–Altman analysis was performed. Statistical tests were 2-tailed, and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. SPSS statistics software version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform the statistical analyses.

To ensure data reproducibility, each MR image was measured by two experts (G.I. and Y. K., with 5 and 13 years of experience, respectively) with consensus. Structures outside the left ventricle were carefully avoided. Blinded analyses were performed to assess the reproducibility of the calculations and independent triplicate analyses were performed on different days. Reproducibility was quantified using the ICC for absolute agreement. The ICC values were interpreted as follows: 0.81–1.0, substantial agreement; 0.61–0.80, moderate agreement; 0.41–0.60, fair agreement; 0.11–0.40, slight agreement; and 0.00–0.10, virtually no agreement48.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aquaro, G. D. et al. Diagnostic and prognostic role of late gadolinium enhancement in cardiomyopathies. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 25, C130–C136. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartjsupp/suad015 (2023).

Jenista, E. R. et al. Revisiting how we perform late gadolinium enhancement CMR: Insights gleaned over 25 years of clinical practice. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 25, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-023-00925-0 (2023).

Doltra, A., Amundsen, B. H., Gebker, R., Fleck, E. & Kelle, S. Emerging concepts for myocardial late gadolinium enhancement MRI. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 9, 185–190. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573403x113099990030 (2013).

Perez-Rodriguez, J., Lai, S., Ehst, B. D., Fine, D. M. & Bluemke, D. A. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Incidence, associations, and effect of risk factor assessment–report of 33 cases. Radiology 250, 371–377. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2502080498 (2009).

Flett, A. S. et al. Evaluation of techniques for the quantification of myocardial scar of differing etiology using cardiac magnetic resonance. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 4, 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.11.015 (2011).

Stirrat, J., Joncas, S. X., Salerno, M., Drangova, M. & White, J. Influence of phase correction of late gadolinium enhancement images on scar signal quantification in patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 17, 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-015-0163-8 (2015).

GhaffariJolfayi, A. et al. Machine learning-based interpretation of non-contrast feature tracking strain analysis and T1/T2 mapping for assessing myocardial viability. Sci. Rep. 15, 753. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85029-0 (2025).

Nakata, M., Yokota, N. & Kenzaka, T. Diffusion-weighted whole-body magnetic resonance imaging with background body signal suppression was useful in a patient with isolated myocardial abscess confined to the right atrial wall: A case report. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23, 341. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03366-w (2023).

Raja, A. et al. Diagnosis of pericardial cysts using diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging: A case series. J. Med. Case Rep. 5, 479. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-5-479 (2011).

Gatti, M. et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance of cardiac tumors and masses. World J. Cardiol. 13, 628–649. https://doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v13.i11.628 (2021).

Broncano, J. et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging of the chest: A primer for radiologists. Radiographics 43, e220138. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.220138 (2023).

Cohen, Y. & Assaf, Y. High b-value q-space analyzed diffusion-weighted MRS and MRI in neuronal tissues: A technical review. NMR Biomed. 15, 516–542. https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.778 (2002).

Fujiyoshi, K. et al. Application of q-space diffusion MRI for the visualization of white matter. J. Neurosci. 36, 2796–2808. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1770-15.2016 (2016).

Nakashima, D. et al. Quantitative analysis of intervertebral disc degeneration using Q-space imaging in a rat model. J. Orthop. Res. 38, 2220–2229. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.24757 (2020).

Nakashima, D. et al. Detecting mild lower-limb skeletal muscle fatigue with stimulated-echo q-space imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 20, 457–466. https://doi.org/10.2463/mrms.tn.2020-0096 (2021).

Hata, J. et al. Noninvasive technique to evaluate the muscle fiber characteristics using q-space imaging. PLoS ONE 14, e0214805. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214805 (2019).

McClymont, D. et al. Evaluation of non-Gaussian diffusion in cardiac MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 78, 1174–1186. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26466 (2017).

Dwyer, K. D. & Coulombe, K. L. K. Cardiac mechanostructure: Using mechanics and anisotropy as inspiration for developing epicardial therapies in treating myocardial infarction. Bioact. Mater. 6, 2198–2220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.12.015 (2021).

Janse, M. J. et al. The “border zone” in myocardial ischemia. An electrophysiological, metabolic, and histochemical correlation in the pig heart. Circ. Res. 44, 576–588. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.res.44.4.576 (1979).

Park, C. H. et al. Development and validation of cardiac diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of myocardial injury in small animal models. Sci. Rep. 14, 3552. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52746-5 (2024).

Zhang, L. J. et al. Quantification of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular MRI in patients with coronary artery chronic total occlusion. Clin. Radiol. 75, 643 e619-643 e626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2020.03.032 (2020).

Fernandez-Jimenez, R. et al. Pathophysiology underlying the bimodal edema phenomenon after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66, 816–828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.023 (2015).

Garcia-Dorado, D. et al. Analysis of myocardial oedema by magnetic resonance imaging early after coronary artery occlusion with or without reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Res. 27, 1462–1469. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/27.8.1462 (1993).

Farrell, J. A. et al. q-space and conventional diffusion imaging of axon and myelin damage in the rat spinal cord after axotomy. Magn. Reson. Med. 63, 1323–1335. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.22389 (2010).

Ong, H. H. et al. Indirect measurement of regional axon diameter in excised mouse spinal cord with q-space imaging: simulation and experimental studies. Neuroimage 40, 1619–1632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.017 (2008).

Yanagisawa, F. et al. Non-contrast-enhanced T(1) mapping of dilated cardiomyopathy: Comparison between native T(1) values and late gadolinium enhancement. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 18, 12–18. https://doi.org/10.2463/mrms.mp.2017-0136 (2019).

Ferreira, V. M. et al. Non-contrast T1-mapping detects acute myocardial edema with high diagnostic accuracy: A comparison to T2-weighted cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 14, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-14-42 (2012).

Karamitsos, T. D. et al. Noncontrast T1 mapping for the diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 6, 488–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.11.013 (2013).

Hoey, E. T., Elassaly, M., Ganeshan, A., Watkin, R. W. & Simpson, H. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 4, 397–406. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2014.09.04 (2014).

Blankstein, R. & Waller, A. H. Evaluation of known or suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 9, e000867. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000867 (2016).

Cheng, R. K. et al. Diagnosis and management of cardiac sarcoidosis: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 149, e1197–e1216. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001240 (2024).

Tanikawa, M. et al. q-Space myelin map imaging for longitudinal analysis of demyelination and remyelination in multiple sclerosis patients treated with fingolimod: A preliminary study. J Neurol Sci 373, 352–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2017.01.009 (2017).

Roebroeck, A., Miller, K. L. & Aggarwal, M. Ex vivo diffusion MRI of the human brain: Technical challenges and recent advances. NMR Biomed. 32, e3941. https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.3941 (2019).

Vasung, L. et al. Ex vivo fetal brain MRI: Recent advances, challenges, and future directions. Neuroimage 195, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.03.034 (2019).

Holz, M., Heil, S. R. & Sacco, A. Temperature-dependent self-diffusion coefficients of water and six selected molecular liquids for calibration in accurate 1H NMR PFG measurements. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2, 4740–4742. https://doi.org/10.1039/B005319H (2000).

Haga, Y. et al. MR imaging properties of ex vivo common marmoset brain after formaldehyde fixation. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 18, 253–259. https://doi.org/10.2463/mrms.mp.2018-0086 (2019).

Lindsey, M. L. et al. Guidelines for Experimental Models of Myocardial Ischemia and Infarction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 314, H812–H838. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00335.2017 (2018).

Liu, D. et al. CMR native T1 mapping allows differentiation of reversible versus irreversible myocardial damage in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: An OxAMI study (Oxford Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 10, e005986. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005986 (2017).

Eitel, I. & Friedrich, M. G. T2-weighted cardiovascular magnetic resonance in acute cardiac disease. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 13, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-13-13 (2011).

Shah, D. V., Kalekar, D. T., Gupta, D. A. & Lamghare, D. P. Role of late gadolinium enhancement in the assessment of myocardial viability. Cureus 14, e22844. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.22844 (2022).

Eida, S. et al. Length of intact plasma membrane determines the diffusion properties of cellular water. Sci. Rep. 6, 19051. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19051 (2016).

Katsumata, Y. et al. Endogenous prostaglandin D2 and its metabolites protect the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury by activating Nrf2. Hypertension 63, 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01639 (2014).

Endo, J. et al. Metabolic remodeling induced by mitochondrial aldehyde stress stimulates tolerance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circ Res. 105, 1118–1127. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206607 (2009).

Ichihara, G. et al. MRP1-dependent extracellular release of glutathione induces cardiomyocyte ferroptosis after ischemia-reperfusion. Circ. Res. 133, 861–876. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.123.323517 (2023).

Sugai, K. et al. A microsurgical technique for catheter insertion in the rat femoral artery. Acta Cir. Bras. 35, e202001004. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-865020200100000004 (2020).

Stejskal, E. O. & Tanner, J. E. Spin diffusion measurements: Spin echoes in the presence of a time-dependent field gradient. J. Chem. Phys. 42, 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1695690 (1965).

Kim, H. W. et al. Relationship of T2-weighted MRI myocardial hyperintensity and the ischemic area-at-risk. Circ. Res. 117, 254–265. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305771 (2015).

Shrout, P. E. Measurement reliability and agreement in psychiatry. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 7, 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/096228029800700306 (1998).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Yoshiko Miyake (Department of Cardiology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan) for the technical support. The authors also thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for the English language editing.

Funding

This research was supported by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development under Grant Number JP20lm0203004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.I., J.H. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. J.H, D.N, Y.K. conducted the experiments and performed data analysis and discussion. Y.K. provided overall leadership, supervision, and funding; designed the study; interpreted the experiments; and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final submission of manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Keio University School of Medicine (12094).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ichihara, G., Hata, J., Nakashima, D. et al. Time series analysis of ex-vivo ischemia-reperfused heart using Q-space imaging. Sci Rep 15, 29250 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14394-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14394-1