Abstract

Strontium stannate nanorods (SrSnO3 NRs) were synthesized in the present study via a green, sustainable, and cheap method with leaf extract from Juniperus communis L. UV-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDAX) were performed to investigate the SrSnO3 NRs. The particle size distribution (PSD) of SrSnO3 NRs characterized by using dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis. The UV-visible spectra of the synthesized SrSnO3 NRs showed an absorption peak at 279 nm. SEM images confirmed that SrSnO3 NRs, which have an average size of about 29 nm, include a bunch of rod-like structure. In addition, the as-formed SrSnO3 NRs demonstrated excellent antibacterial activity against the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Escherichia coli. The synthesized SrSnO3 nanorods also exhibited a significant amount of antioxidant activity. It is also an attractive biocompatible choice for pharmacological and medical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The idiosyncratic characteristics of nanoparticles (NPs) have formed nanoscale an essential field with significant potential for different uses1. Their optical, magnetic, catalytic, and electrical characteristics are enhanced in these nanoscale materials as compared with their bulk counterparts2,3. Therefore, the advancement of effective and sustainable nanoparticles methods for synthesis has received more interest. Environmental issues and possible toxicity can be caused by the use of hazardous chemicals, high temperatures, and energy-intensive methods in conventional nanoparticle synthesis techniques. As an alternative for these issues, green synthesis has attracted a lot of interest. Renewable or sustainable synthesis, or “green synthesis,” is a method to produce nanoparticles with natural resources, biomolecules, or sustainable materials4,5,6. Reduced energy consumption, a decreased usage of toxic materials, biodegradability and the potential advantage of large-scale manufacturing are a few of its advantages over conventional processes7.

The application of biosynthesis and green synthesis methods has increased in interest recently as alternatives of producing NPs. These methods utilize alcoholic or aqueous plant extracts in addition to biological organisms such yeasts, fungus, bacteria, and marine algae. In addition to standard methods, green synthesis has several of advantages, like be cheaper, less harmful to the environment, as well as not needing toxic chemical reagents or high pressure, energy, or temperature8,9. The high surface area-to-volume ratio of NPs, which range in size from 1 to 100 nm, allows them to quickly circulate in human organs10, and absorb a significant quantity of drugs11. Clinical application of these methods to enhance drug delivery can also be performed by improving permeability and retention effects at infection sites12. With excellent magnetic, and catalytic characteristics, strontium (Sr) is a good choice for metallic nanoparticles (NPs). Sr-based NPs have attracted the interest of researchers from a wide range of areas for a variety of applications, such as storage media, sensors, memory, fluids, composites, and catalysis13,14. Biological and bacterial responses to the challenge can be induced with the addition of novel nanoparticles15,16,17. The areas of information and communication (including electrical and optoelectronic fields), food technology, energy technology, and pharmaceuticals (which includes various medications and drug delivery systems, diagnostics, and medical technology) are the fields which embrace nanotechnology at the highest rate18,19,20.

SrSnO3 nanorods has a broad bandgap, which makes it suitable for usage in light-emitting devices, solar cells, and sensors21,22,23. The rod-like structure enhances electron mobility, which is beneficial for energy storage applications. In activities involving energy conversion, such as hydrogen evolution, SrSnO3 NRs are efficient as catalysts24. Stability and efficiency are given via the perovskite structure in lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitors. In wastewater treatment, SrSnO3 NRs are useful for decomposing organic pollutants due to their excellent photocatalytic activity. The catalytic, optical, and structural properties of SrSnO3 nanorods provide an attractive option for sustainability and biological uses. Developing novel antibacterial agents will be needed due to the increasing worldwide disease of antibiotic resistance25. SrSnO3 is one of several metal oxide nanostructures that exhibit significant antibacterial activity owing to its capacity to generated reactive oxygen species (ROS), damage membranes of bacteria, and inhibit microbial metabolism. Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria are highly inhibited with SrSnO3 NRs due to their high surface area, which enhances their interaction with bacterial cells26,27,28. Most of the studies revealed that the synthesis of SrSnO3 was done by the chemical method. The activity of SrSnO3 may be enhanced by adding bio-derived elements, which may improve the photocatalytic performance29,30. Green synthesis method with plant extracts have been studied recently for the sustainable production of SrSnO3 NRs, which decreases the demand for toxic chemicals. By enhancing the performance and biocompatibility of nanomaterials, this method qualifies them for usage in wound healing, antibacterial coatings, and antioxidant therapy31.

The evergreen plant known as common juniper (Juniperus communis L.) is found across Europe, North America, and Asia. It has a high phytochemicalcomposition with flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenes, tannins, and essential oils, which has given rise to its traditional usage in herbal medicine32. Due to the different pharmacological properties of the bioactive chemicals present in Juniperus communis L. extract, it can be beneficial in a variety of fields, such as medicine, cosmetics, and nanotechnology33. In addition to its strong antibacterial activity against a variety of bacterial and fungal strains, the plant extract can be used to treat infections. In scavenging free radicals, reducing oxidative stress, and limiting cell damage, Juniperus communis’s antioxidant properties in polyphenols and flavonoids are advantageous. A useful resource for usage in medicine, cosmetics, nanotechnology, and sustainability, Juniperus communis L. extract demonstrates a variety of biological activities. Its role in the green synthesis of SrSnO3 NRs enhances the sustainability and functionality of nanomaterials, promoting their use in antibacterial and antioxidant properties34,35,36.

In the present work, for the first time SrSnO3 NRs were effectively synthesized by using Juniperus communis L. leaf extract, and their crystal structure, chemical composition, and dynamics of interaction with the reducing agent were all described. The morphology of the material was controlled by the green synthesis method. The as-synthesized nanorods were characterized by UV-Visible, FTIR, XRD, FESEM, and DLS analysis. The agar diffusion method was used to evaluate the antibacterial activity of SrSnO3 NRs against Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis), and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli). At 250 µg/mL, a radical scavenging rate of 68.00% was observed in the results of antioxidant activity.

Experimental section

Materials

Fresh leaves of the Juniperus communis L. plant have been collected in Yeungnam University Campus, South Korea. The following materials have been obtained from Sigma Aldrich: Strontium nitrate hexahydrate [Sr(NO3)2·6H2O], Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), Sodium stannate Na2[Sn(OH)6], and ethanol (CH3CH2OH). All collected chemicals were used as received.

Preparation of Juniperus communis L. leaf extract

To prepare the leaf extract, 10.0 g of Juniperus communis L. leaves were washed multiple times with tap water and double-distilled water. After that, 250 mL of double-distilled water was added to a 250 mL beaker with washed leaves to help in the procedure of extraction. The mixture was further heated to 100 °C for 45 min. The end product of this procedure was a dark green solution of leaf extract from Juniperus communis L. To obtain a clear solution, the extract was filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper. Clean Juniperus communis L. leaf extract served to synthesize SrSnO3 NRs.

Synthesis of SrSnO3 nanorods from Juniperus communis L. leaf extract

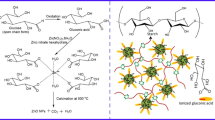

The green synthetic process of SrSnO3 NRs via a solution of Juniperus communis L. leaf extract was done by co-precipitation method given in Fig. 1. 0.84 g of Strontium nitrate hexahydrate and 1.06 g of sodium stannate were dissolved in 20 mL of water separately. After 10 min of stirring, both solutions are mixed and stirred for 10 min. Then 20 mL of Juniperus communis L. plant extract was added dropwise to the above mixture, and the whole solution was stirred until the thoroughly mixing of plant extract. A 20 mL of 0.5 M sodium hydroxide solution was added to the solution, and the suspension was stirred for 2 h. The obtained precipitate was filtered, washed with water and ethanol several times and dried at 80 °C for 12 h. The pale white powder obtained was calcined at 700 °C for 6 h. The resultant SrSnO3 powder was used for further studies.

Characterization

A UV-visible spectrophotometer (Cary 5000, Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) was employed to measure the synthesis of the characteristic peak which is associated to the SrSnO3 NRs and to confirm and characterize the synthetic SrSnO3 NRs from the extract of Juniperus communis L. in the 200–800 nm range. In the 4000–400 cm− 1 spectral region, attenuated total reflection spectra (ATR)-FTIR were obtained via Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR) (Perkin-Elmer Spectrum Two). X-ray diffraction (Rigaku, PANALYTICAL) was performed with a scan rate of 0.50 min− 1 over a scan range of 2θ = 10–80°. The surfaces and microstructure of SrSnO3 NRs have been studied by a SEM (S-4800, Hitachi, Japan). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDAX) analysis combined with SEM was employed to perform the elemental analysis. Based on photon correlation spectroscopy, the produced SrSnO3 NRs’ particle size and surface charges were examined using DLS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The average zeta potential was found after a 60-s analysis. Without dilution, the zeta potential of a nanoparticulate dispersion was calculated. The results were provided with the associated standard deviations and were gathered by averaging the results of a minimum of three distinct tests. For statistical analysis, t-tests were used in IBM Corporation’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software, version 19.0 (Armonk, NY, USA). It has been discovered that a P-value of less than 0.05 denotes statistical significance.

Antibacterial and antifungal activity

The antibacterial and antifungal properties of synthesized SrSnO3 NRs from Juniperus communis L. extract have been investigated with the agar well diffusion method. In the present study, three bacterial strains (Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Escherichia coli), and two fungal strains (Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans) were used as pathogenic bacteria. 20 mL of Muller Hinton Agar Medium was added to petri plates with bacterial strains (growth of culture controlled according to McFarland Standard, 0.5%). In Potato Dextrose agar plates, fungi that grew over night were swabbed off. SrSnO3 NRs at different concentrations (250, 500, and 1000 µg/mL) were added to wells that were bored via a well cutter and had a diameter of within 10 mm. The plates were then incubated for 48 h at 28 °C for fungi and 24 h at 37 °C for bacteria. The antifungal activity was identified by calculating the diameter of the inhibiting zone that formed around the well. Streptomycin, clotrimazole were utilized to serve as positive controls.

Antioxidant activity by DPPH assay

The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) method was used to test the antioxidant activity of SrSnO3 NRs. The method involved mixing 250 µL of DPPH ethanolic solution with 1 mL of various concentrations of green synthesized SrSnO3 NRs (50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 µg/mL). After be slowly shaken, the solution was kept at 25 °C in a dark place for 45 min. The DPPH reduction activity was measured via calculating the absorbance of each concentration at 517 nm and comparing it to the DPPH ethanol solution (control). As a positive control for antioxidant activity, ascorbic acid was used, while ethanol solutions had been used as a blank. The percentage of DPPH disappearance in a sample was used to denote its antiradical activity. Ascorbic acid and plant extract of Juniperus communis L. were produced in a similar amount for comparison. With Equation, the DPPH radical scavenging capacity (%) has been calculated:

\(DPPH{\text{ }}Radicals{\text{ }}Scavenged{\text{ }}Capacity{\text{ }}\left( \% \right)={A_c}/{\text{ }}{A_s}/{\text{ }}{A_c} \times 100\)

Where; Ac was the absorbance of the control reaction, and As was the absorbance in the presence of test.

Results and discussion

UV-visible spectroscopy

The Juniperus communis L. plant is known to have natural compounds with antibacterial, antifungal, and insecticidal properties. Plant extracts and synthesized SrSnO3 NRs are subjected to UV-Vis analysis at wavelength from 200 to 800 nm. Figure 2a shows the UV–Vis spectrum for the SrSnO3 NRs and Juniperus communis L. plant extracts. Pure Juniperus communis L. extract showed two absorption peaks at 220 nm. These peaks might be in charge of the Sr2+ ion reduction, which interacts with these intermediates resulting in Sr–Sn–O species. Figure 2a clearly suggests that SrSnO3 NRs exhibit distinct broad absorption bands in the 200–400 nm range, with a sharp absorption start near 279 nm. It can be attributed to the electronic transition from the valence band to the conduction band, and is consistent with SrSnO3’s band gap edge absorption37. A strong absorption peak at 279 nm has been observed in the experiment, suggesting that synthetic SrSnO3 NRs exhibit excellent optical properties38.

FTIR spectroscopy

FTIR analysis was used to detect the chemical groups of SrSnO3 NRs and plant extract. To study the reduction in difference, the FTIR spectra of Juniperus communis L. leaf extract and synthesised SrSnO3 NRs were compared [Fig. 2b]. FTIR spectra of Juniperus communis L. leaf extract displays a sharp peak at 3320 cm− 1 due to phenolic OH. The peaks at 2979 cm− 1, and 2882 cm− 1 represent the stretching vibrations of C–H bonds, which may be produced by residual organic compounds or phytochemicals from the extract of Juniperus communis L. used in the green synthesis method. The bending vibrations of C–H or the symmetric stretching of carboxylate groups (–COO⁻) typically responsible for this band 1380 cm− 1, while the presence of bioactive chemicals in the plant extract could also be the cause. The presence of organic residues on the nanorod surface is further confirmed by the attribution of this peak, 1047 cm− 1, to the C–O stretching vibrations of ether or alcohol groups, while C–O–C bending vibrations cause the band at 879 cm− 1. SrSnO3 NRs’ FTIR spectra show distinct peaks at 1445 cm− 1, which are attributed to the symmetrical and asymmetrical stretching vibration of S=O, respectively. These peaks also demonstrate that the surface of the NRs and leaf extract interact. The stretching of Sn–O–Sn of SrSnO3 NRs is connected to the maximum peaks at 643 cm− 1.

XRD analysis

The diffraction peaks of the SrSnO3 NRs range from 10 to 80°, according to XRD tests. XRD patterns of SrSnO3 NRs have been obtained with a Rigaku, PANALYTICAL diffractometer and Cu-Kα radiation. Figure 2c, shows XRD patterns of SrSnO3 nanorods. These diffraction peaks are characteristic SrSnO3 rod structures, which can be attributed to the distinctive peaks of the crystal structure of SrSnO3 NRs. [2θ = 22.32° (100); 31.57° (200); 45.09° (220); 50.96° (222); 55.94° (312); 65.55° (400); 74.54° (322)]. All the diffraction peaks of SrSnO3 NRs well matched with JCPDS card No. 22–1442. According to these results, SrSnO3 nanorods were observed to crystallize, and nanorods were identified to have an average crystal size of about 29 nm.

The crystallite size was estimated using the Scherrer equation:\({\text{D = K}}\lambda {\text{ / }}\beta {\text{cos}}\theta\)

Where, D is the average crystallite size, K is the shape factor (taken as 0.9), λ is the X-ray wavelength (1.5406 Å for Cu-Kα), β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the most intense diffraction peak (in radians), and θ is the Bragg angle corresponding to that peak.

SEM analysis

As shown in Fig. 3a, b at different magnifications, the surface morphology has been described from images obtained using SEM. As can be observed, the SEM images confirmed the rod structure (morphology) of SrSnO339,40,41. The SEM images show the uniform bunch of nanorod structures with small aggregation. The SrSnO3 nanorods exhibit a rod-like morphology with diameters ranging from approximately 100 to 200 nm, as observed from the SEM images [Fig. 3a, b]. The well-crystallized particles were found to be in the nanoscale size range after calcination at 400 °C. The SrSnO3 NRs are normal rod crystals, as can be observed. EDAX analysis has been performed to evaluate the elemental composition of the as-made SrSnO3 NRs [Fig. 3c]. The analysis confirmed that the samples had no noticeable pollutants and that the main elements were carbon (C), oxygen (O), strontium (Sr), and stannate (Sn) [Fig. 3(d–g)].

Dynamic light scattering analysis

The particle size distribution for the SrSnO3 NRs synthesized with Juniperus communis L. leaf extract, as measured by the DLS method, is illustrated in Fig. 4a. The median size of the particle distribution of the synthesized SrSnO3 NRs was 29 nm, based on the size distribution data. The examination indicated a unimodal size distribution with a polydispersity index; the suspension was monodispersed with significant colloidal stability. Also, the zeta-potential of the synthesized SrSnO3 NRs was − 5.19 mV [Fig. 4b]. The result shows that, if dispersed in the medium, the surface of the produced nanorods exhibited a negative charge. Thus, the prepared NRs’ good stabilization in the suspensions was caused by the observed negative value. In addition, since the average size is a measure of hydrodynamic size, its value shows the existence of solvent molecules attached to the tumbling particle as well as the availability of nanoparticles. Hence, it is reasonable to expect that a high ZP value raises the physical stability of SrSnO3 NRs and provides a flexible strategy for biomedical applications. As a result, the synthesized SrSnO3 NRs’ zeta-potential value is almost physically stable32.

Antibacterial activity

The increase in antibiotic resistance has caused a lot of attention to the growth of novel antibacterial agents. The long-term antibacterial activity and the ability to differentiate in bacterial or mammalian cells represent two advantages of metal-based nanoparticles42,43,44. If it involves inhibiting microbial cells and reducing antibiotic resistance, these NPs have demonstrated good results. The nanoparticles of metals and metal oxides (NPs) have antibacterial activity against pathogenic microbial cells in several of methods, such the generation of ROS (reactive oxygen species), DNA damage, disruptions in nutrition, metal ion release, disintegration of cell membrane, etc. The antibacterial activity of the obtained SrSnO3 NRs was tested to check their minimum inhibition concentrations (MIC) values. Table 1 illustrates the results of the study.

The results indicated that SrSnO3 NRs at various concentrations of 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL exhibited inhibition zones against bacteria, namely Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Escherichia coli. All studied organisms were shown to be resistant to the SrSnO3 NRs in Fig. 5A. Inhibition zone values are presented in Fig. 5B, and the concentration of SrTiO3 NRs used to perform the antibacterial activity influences the inhibition zone changes. The inhibition of growth has also constantly enhanced by correct diffusion of nanomaterials in the agar media. The bacteria which are shown to be most sensitive to the SrSnO3 NRs were Staphylococcus aureus (21.53 ± 0.5 mm), Enterococcus faecalis (20.22 ± 0.8 mm), and Escherichia coli (26.19 ± 0.2 mm). The surface area, size, and structure of SrTiO3 NRs all have an impact on their antibacterial efficiency. In addition, both positively and negatively charged nanoparticles can electrostatically interact with bacterial cells to enhance the creation of reactive oxygen species within the cells, which inhibits growth and induces cell death45.

Antifungal activity

Aspergillus niger, and Candida albicans were used in this study to investigate the antifungal activity of SrSnO3 NRs using a well-diffusion method. The SrSnO3 samples were produced in three different concentrations (250, 500, and 1000 µg). The results are shown in Fig. 6, and Table 2. For fungi such as A. niger and C. albicans, the inhibition zone diameter (positive control) of the antibiotic Clotrimazole (100 µg) was 30.11 ± 0.8 mm, and 27.22 ± 1.5 mm, respectively. With a zone diameter of 15.73 ± 0.9 mm, and 19.22 ± 1.2 mm respectively, A. niger exhibited zone of inhibition at 250, 500 µg concentrations. C. albicans had a zone diameter of 12.81 ± 1.8 mm, and 17.65 ± 0.7 mm at 250, 500 µg of SrSnO3 samples concentration. If 1000 µg of SrSnO3 NRs was present, the zone of inhibition for A. niger and C. albicans was 25.15 ± 2.0 mm and 23.04 ± 1.0 mm, respectively. SrSnO3 NRs have a significant antifungal effect, albeit far fewer than that of the standard drugs, according to the results. Because of their decreased size, SrSnO3 NRs can have an antifungal effect on the organisms. Since the nanorod comes into direct contact with the fungal cell membrane, it can penetrate the cell walls and inhibit fungal growth46.

Antioxidant activity

The obtained SrSnO3 NRs exhibited DPPH radical scavenging in a dose-dependent manner, ranging from 37.50 at 50 µg/mL to 68.00 at 250 µg/mL. Ascorbic acid’s IC50 was lower at 15.22 µg/mL, but the SrSnO3 NRs showed radical scavenging activity with an IC50 value of 91.20 µg/mL. Interestingly, at a concentration of 250 µg/mL, the plant extract exhibited a remarkable antioxidant activity of 39.65 µg/mL in comparison with ascorbic acid. The results of this study are presented in Fig. 7. The measured the antioxidant activity reached its maximum at 250 µg/mL and that increasing it could not provide extra advantages or can lead to challenges (such as toxicity, aggregation, or solubility issues), this concentration is suggestive of good antioxidant activity among the tested concentrations. SrSnO3 NRs’ antioxidant activities are could be helpful in areas such as materials science, food preservation, and photocatalytic activity47.

Green synthesis is growing importance as an environmentally friendly, affordable, and sustainable solution to these challenges. Green synthesis employs biological materials as stabilizing and reducing agents, such bacteria, fungi, algae, and plant extracts, to produce nanoparticles in mild conditions. With regard to the ease of usage, scalability, and the abundance of phytochemicals used in the development of nanoparticles, plant-mediated synthesis is distinctive among these. For the sustainable production of SrSnO3 NRs, plant extracts have been studied; each plant provides distinct characteristics to the resultant nanoparticles. Table 3 exhibits the biological properties, and synthesis of SrSnO3 NRs using Juniperus communis L. plant extracts.

Conclusion

Green synthesis is cost-effective and biocompatible as it utilises renewable resources and avoids harmful chemicals. The benefits of green synthesis include a reduction of the need for hazardous chemicals, adaptability for large-scale fabrication, and the capacity to produce distinct sizes. In this study, SrSnO3 nanorods were successfully synthesized via a green co-precipitation method using Juniperus communis L. leaf extract as a reducing and stabilizing agent. The synthetic method was both cost-effective, and eco-friendly to the environment. The synthesis of SrSnO3 NRs was confirmed by the UV-vis absorption peak at 279 nm. SEM images confirmed that SrSnO3 had formed a rod-like shape structure. According to SEM the measurements, the nanorod’s average size was found to be 29 nm. The structure and surface functional group of the as-synthesised SrSnO3 NRs have been revealed via the FTIR analysis. The results of the antibacterial tests indicated that SrSnO3 NRs effectively inhibited the growth of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Further, DPPH assay indicated SrSnO3 NRs has antioxidant activity with IC50 value of 91.20 µg/mL. The synthesized SrSnO3 NRs exhibited well-defined structural features along with significant antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities. These results highlight the potential of plant-mediated synthesis for eco-friendly nanomaterial production. In future research will focus on studying the SrSnO3 NRs’ photocatalytic and anticancer activities as well as enhancing the synthesis conditions for common application in the biological, and environmental fields.

Data availability

Authors will make availability of data and materials on reasonable request. The point of contact for requesting data are Raja Venkatesan (rajavenki101@gmail.com) & Seong-Cheol Kim (sckim07@ynu.ac.kr).

References

Joudeh, N. & Linke, D. Nanoparticle classification, physicochemical properties, characterization, and applications: A comprehensive review for biologists. J. Nanobiotechnol. 20, 262. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-022-01477-8 (2022).

Baig, N., Kammakakam, I., & Falath, W. Nanomaterials: A review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Mater. Adv. 2 1821–1871. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0MA00807A (2021).

Alshammari, B. H. et al. Organic and inorganic nanomaterials: Fabrication, properties and applications. RSC Adv. 13, 13735–13785. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA01421E (2023).

Ying, S. et al. Green synthesis of nanoparticles: Current developments and limitations. Environ. Technol. Innov. 26, 102336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2022.102336 (2022).

Noah, N. M. & Ndangili, P. M. Green synthesis of nanomaterials from sustainable materials for biosensors and drug delivery. Sens. Int. 3, 100166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sintl.2022.100166 (2022).

Osman, A. I. et al. Synthesis of green nanoparticles for energy, biomedical, environmental, agricultural, and food applications: A review. Environ Chem. Lett. 22, 841–887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-023-01682-3 (2024).

Islam, M. et al. Impact of bioplastics on environment from its production to end-of-life. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 188, 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2024.05.113 (2024).

Osman, A. I. et al. Synthesis of green nanoparticles for energy, biomedical, environmental, agricultural, and food applications: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 22, 841–887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-023-01682-3 (2024).

Radulescu, D. M., Surdu, V. A., Ficai, A., Ficai, D. & Grumezescu, A. Andronescu, M. E. Green synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles: A review of the principles and biomedical applications. Int J. Mol. Sci. 24, 15397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242015397 (2023).

Mitchell, M. J. et al. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 101–124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-020-0090-8 (2021).

Chenthamara, D. et al. Therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticles and routes of administration. Biomater. Res. 23, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40824-019-0166-x (2019).

Dang, Y. & Guan, J. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. Smart Mater. Med. 1, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smaim.2020.04.001 (2020).

Yoon, Y., Truong, P. L., Lee, D. & Ko, S. H. Metal-oxide nanomaterials synthesis and applications in flexible and wearable sensors. ACS Nanosci. Au. 2, 64–92. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnanoscienceau.1c00029 (2022).

Kim, K. M., Kang, S., Kwak, B. S. & Kang, M. Enhancement of hydrogen production from MeOH/H2O photo-splitting using micro-/nano-structured SrSnO3/TiO2 composite catalysts. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 14, 9198–9205. https://doi.org/10.1166/jnn.2014.10128 (2014).

Nanda, S., Patra, B. R., Patel, R., Bakos, J. & Dalai, A. K. Innovations in applications and prospects of bioplastics and biopolymers: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 20, 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-021-01334-4 (2022).

Khan, I., Saeed, K. & Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 12, 908–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.05.011 (2019).

Kader, M. A., Azmi, N. S. & Kafi, A. K. M. Recent advances in gold nanoparticles modified electrodes in electrochemical nonenzymatic sensing of chemical and biological compounds. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 153, 110767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2023.110767 (2023).

Thakur, S., Thakur, I. & Kumar, R. A review on synthesized NiO nanoparticles and their utilization for environmental remediation. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 172, 113758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.113758 (2025).

Sukumaran, J., Venkatesan, R., Priya, M. & Kim, S. C. Eco-friendly synthesis of CeO2 nanoparticles using Morinda citrifolia L. leaf extracts: Evaluation of structural, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory activity. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 172, 113758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.113411 (2025).

Priya, M. et al. Green synthesis, characterization, antibacterial, and antifungal activity of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from Morinda citrifolia leaf extract. Sci. Rep. 1318838. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46002-5 (2023).

Zhang, W. F., Tang, J. & J. Ye Photoluminescence and photocatalytic properties of SrSnO3 perovskite. Chem. Phys. Lett. 418, 174–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2005.10.122 (2025).

Mohan, T. & Kuppusamy, S. R.,Michael, J. V. Tuning of structural and magnetic properties of SrSnO3 nanorods in fabrication of blocking layers for enhanced performance of dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS Omega 7, 18531–18541. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c01191 (2022).

Rahman, A. B. A., Sarjadi, M. S., Alias, A. & Ibrahim, M. A. Fabrication of Stannate perovskite structure as optoelectronics material: An overview. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1358, 012043. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1358/1/012043 (2019).

Chen, D. & Ye, J. SrSnO3 nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic properties. Chem. Mater. 19, 4585–4591. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm071321d (2007).

Teixeira, A. R. F. A. et al. SrSnO3 perovskite obtained by the modified pechini method—Insights about its photocatalytic activity. J Photochem. Photobiol A Chem. 369, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2018.10.028 (2019).

Draviana, H. T. et al. Size and charge effects of metal nanoclusters on antibacterial mechanisms. J. Nanobiotechnol. 21, 428. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02208-3 (2023).

Epand, R. M., Walker, C., Epand, R. F. & Magarvey, N. A. Molecular mechanisms of membrane targeting antibiotics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 1858, 908–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.10.018 (2016).

Aravinthkumar, K., Praveen, E. & Mary, A. J. R., Mohan C. R. Investigation on SrTiO3 nanoparticles as a photocatalyst for enhanced photocatalytic activity and photovoltaic applications. Inorg Chem. Commun. 140, 113758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109451 (2022).

Lobo, T. M., Lebullenger, R., Bouquet, V., Guilloux-Viry, M. & Santos, I. M. G., Weber, I. T. SrSnO3:N – nitridation and evaluation of photocatalytic activity. J Alloys Compd. 649, 491–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.05.203 (2016).

Barabadi, H. et al. Phytofabrication, characterization and investigation of biological properties of Punica granatum flower-derived silver nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 170, 113515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.113515 (2024).

Deng, X., Gould, M. & Ali, M. A. A review of current advancements for wound healing: Biomaterial applications and medical devices. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 110, 2542–2573. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.35086 (2022).

Gonfa, Y. H. et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of phytochemicals from medicinal plants and their nanoparticles: A review. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 6, 100152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbiot.2023.100152 (2023).

Makhuvele, R. et al. The use of plant extracts and their phytochemicals for control of toxigenic fungi and Mycotoxins. Heliyon 6, e05291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05291 (2023).

Masyita, A. et al. Terpenes and terpenoids as main bioactive compounds of essential oils, their roles in human health and potential application as natural food preservatives. Food Chem. X. 13100217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100217 (2022).

Chantelle, L. et al. Europium induced point defects in SrSnO3-based perovskites employed as antibacterial agents. J Alloys Compd. 956, 170353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.170353 (2023).

Fadilah, N. I. M. et al. Antioxidant biomaterials in cutaneous wound healing and tissue regeneration: A critical review. Antioxidants 12, 787. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12040787 (2023).

Li, K., Gao, Q., Zhao, L. & Liu, Q. Electrical and optical properties of Nb-doped SrSnO3 epitaxial films deposited by pulsed laser deposition. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 15, 164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-020-03390-1 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Exploring nanoscale perovskite materials for next-generation photodetectors: A comprehensive review and future directions. Nano-Micro Lett. 17, 28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-024-01501-6 (2025).

Ghubish, Z. et al. Photocatalytic activation of Ag-doped SrSnO3 nanorods under visible light for reduction of p-nitrophenol and methylene blue mineralization. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 33, 24322–24339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-022-09152-2 (2022).

Venkatesh, G., Geerthana, M., Prabhu, S. & Ramesh, R. K. M. Prabu, Enhanced photocatalytic activity of reduced graphene oxide/SrSnO3 nanocomposite for aqueous organic pollutant degradation. Optik. 206, 164055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2019.164055 (2020).

Alammar, T., Hamm, I., Grasmik, V., Wark, M. & A. -V Mudring, Microwave-assisted synthesis of perovskite SrSnO3 nanocrystals in ionic liquids for photocatalytic applications. Inorg. Chem. 56, 6920–6932. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b00279 (2017).

Sánchez-López, E. et al. Metal-based nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents: An overview. Nanomaterials. 10, 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10020292 (2020).

Godoy-Gallardo, M. et al. Antibacterial approaches in tissue engineering using metal ions and nanoparticles: From mechanisms to applications. Bioact Mater. 6, 4470–4490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.04.033 (2021).

Bedair, H. M., Hamed, M. & Mansour, F. R. New emerging materials with potential antibacterial activities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 108, 515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-024-13337-6 (2024).

Solanki, R. et al. Nanomedicines as a cutting-edge solution to combat antimicrobial resistance. RSC Adv. 14, 33568–33586. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4RA06117A (2024).

Huang, T. et al. Using inorganic nanoparticles to fight fungal infections in the antimicrobial resistant era. Acta Biomater. 158, 56–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2023.01.019 (2024).

Kumar, S., Ahlawat, R., Siddharth, Bhawna & Rani, G. Antioxidant and photo-catalytic activity of diamond-shaped iron-based metal-organic framework. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 167, 112661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112661 (2024).

Mahboub, S., Zerrouki, D. & Henni, A. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Juniperus communis leaf extract: Catalytic activity in real-outdoor conditions and electrochemical properties. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, (e5956). https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.5956 (2024).

Gad El–Rab, S. M. F., Halawani, E. M. & Alzahrani, S. S. S. Biosynthesis of silver nano–drug using Juniperus excelsa and its synergistic antibacterial activity against multidrug–resistant bacteria for wound dressing applications. 3 Biotech. 11, 255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-021-02782-z (2021).

Ibrahim, E. H., Kilany, M., Ghramh, H. A. & Khan, K. A. S. u. Islam 2019 cellular proliferation/cytotoxicity and antimicrobial potentials of green synthesized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using Juniperus procera. Saudi J. Biol. Sci 26, 1689–1694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.08.014

Bakri, M. M., El-Naggar, M. A., Helmy, E. A. & Ashoor, M. S. T. M. A. Ghany 2020 Efficacy of Juniperus procera constituents with silver nanoparticles against Aspergillus fumigatus and Fusarium chlamydosporum. BioNanoSci. 10, 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-019-00716-x

Al Masoudi, L. M., Alqurashi, A. S. & Zaid, A. A. H. Hamdi 2023 Characterization and biological studies of synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles from leaf extract of Juniperus phoenicea (L.) growing in Taif region, Saudi Arabia. Processes. 11, 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11010272

Haq, S. et al. G. Ali 2020 green synthesis and characterization of Tin dioxide nanoparticles for photocatalytic and antimicrobial studies. Mater Res. Express 7 025012. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ab6fa1

Anbu, P., Gopinath, S. C. B., Salimi, M. N. & Letchumanan, I. S. Subramaniam 2022 green synthesized strontium oxide nanoparticles by Elodea Canadensis extract and their antibacterial activity. J Nanostruct. Chem 12 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40097-021-00420-x

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the “2024 System Semiconductor Technology Development Program” funded by the Chungbuk Technopark. The authors acknowledge and appreciate the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-774), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

The study was done with a support of the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-774), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Raja Venkatesan: Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Thamaraiselvi Kanagaraj: Investigation, Data curation. Maher M. Alrashed: Data curation, Writing—review and editing. Munusamy Settu: Resources, Software. Alexandre A. Vetcher: Investigation, Writing - original draft. Seong-Cheol Kim: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

We comply with relevant guidelines and legislation regarding the sample collection in the present study. The plant leaf (Juniperus communis L.), in the present study is not endangered. The Juniperus communis L. leaves in 2025 were collected in Yeungnam University campus, Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea. Samples of plant materials in the present study do not exist.

Consent to participate

All person named as author in this manuscript have participated in the planning, design and performance of the research and in the interpretation of the result.

Consent for publication

All authors have indorsed the publication of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Venkatesan, R., Kanagaraj, T., Alrashed, M.M. et al. Green synthesis of strontium stannate nanorods using extract of Juniperus communis L.: Structural characterization and evaluation of antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activity. Sci Rep 15, 32166 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14412-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14412-2