Abstract

The relationship between land use change and regional carbon storage is closely linked. Understanding how land use changes affect regional carbon storage is crucial for maintaining the carbon balance of ecosystems. This study integrated the advantages of the PLUS model, the InVEST model, and the optimal parameter-based geographic detector (OPGD) models to analyze the spatiotemporal variation in land use patterns and carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin under three scenarios in 2030, and analyze the driving forces of the spatial differentiation of carbon storage. The results show that the following: (1) From 1980 to 2020, the areas of water and construction land in the Fuhe River Basin increased by 28.08 km² and 217.65 km², respectively, while the areas of cultivated land, woodland, grassland, and unused land decreased by 115.33 km², 112.79 km², 88.79 km², and 1.36 km², respectively. (2) Between 1980 and 2020, the total carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin showed a decreasing trend, with a reduction of 20.39 × 105 t. The main drivers of this decline were the reduction in woodland area and the expansion of construction land. (3) By 2030, carbon storage is projected to continue decreasing under all three scenarios, with the ecological protection scenario showing the most pronounced mitigating effect on the reduction of carbon storage. (4) The spatial differentiation of carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin is influenced by various factors, including land use intensity, NDVI, elevation, and slope, with land use intensity having the strongest explanatory power, reaching 0.24. This study offers policymakers valuable insights for optimizing ecosystem carbon storage and provides essential guidance for achieving the “dual carbon” goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the rapid development of global industrialization and urbanization has made global warming, caused by greenhouse gas emissions, one of the most significant challenges faced worldwide1,2, with profound impacts on the ecological environment and socio-economic development3,4. To address climate warming, China has set the goals of reaching a “carbon emissions peak” by 2030 and achieving “carbon neutrality” by 20605. In the context of the “dual carbon” goals, reducing carbon emissions and enhancing the carbon sequestration capacity of terrestrial ecosystems have emerged as central challenges in current research6,7. Land use change is one of the main factors influencing changes in carbon storage of terrestrial ecosystems, primarily through the conversion of land types that alter the carbon sequestration capacity of surface vegetation and soil8,9. Therefore, quantitatively assessing the spatiotemporal evolution of regional ecosystem carbon storage and the driving forces of its spatial differentiation from the perspective of land use change, as well as predicting the spatiotemporal distribution of carbon storage under different scenarios, is crucial for achieving sustainable regional ecosystem development, enhancing carbon sequestration capacity, and achieving the “dual carbon” goals.

Methods for assessing carbon storage in terrestrial ecosystems primarily include field investigations10, remote sensing interpretations11, and simulation models12. Each of these methods has its advantages and limitations. For example, field investigations can provide relatively accurate estimates of carbon storage; however, their applicability is limited, and they struggle to reflect dynamic changes in carbon storage13. Remote sensing interpretations are suitable for large-scale carbon storage assessments; however, they often rely on data from specific ecosystems or partial carbon pools14. In contrast, data for simulation models are relatively easy to obtain, convenient to use, and can be applied to studies of carbon storage changes at various spatial scales15,16,17. Among various carbon storage assessment models, the InVEST model has been widely adopted by researchers due to its low data requirements, fast processing speed, and relatively accurate results. For example, Piyathilake et al.18 used the InVEST model to assess carbon storage in Uva Province, Sri Lanka, while Wang et al.19 applied it to quantify carbon storage changes in the terrestrial ecosystems of Jiangxi Province. The results indicated that the expansion of construction land was the primary cause of the reduction in carbon storage. However, the InVEST model is limited in its directs simulation of future land use changes and often requires integration with land use models to predict carbon storage under different scenarios.

Land use simulation is a crucial tool for studying and predicting future land use changes, and it is widely used to assess the dynamic trends in land use evolution. Typical land-use prediction models, both domestically and internationally, include CA-Markov, CLUE-S, and FLUS20,21,22. Although these models are effective at simulating future land use changes, they have limitations in identifying the underlying drivers of land use changes and patch evolution. To address this limitation, Liang et al.23 proposed the PLUS model, which was optimized and improved based on CA-Markov, FLUS, and other models. It not only accurately simulates the generation and evolution of various types of land patches across spatial and temporal scales, but also provides a deeper analysis of the underlying driving forces of land use change, thereby improving simulation accuracy and presenting a more realistic land use pattern. As a result, an increasing number of researchers have conducted in-depth studies in the field of ecology using the “PLUS-InVEST” model.

Fu et al.24 focused their study on Ningwu County, using land use data from 1990 to 2020. The PLUS and InVEST models were applied to analyze the spatiotemporal changes in land use and carbon storage. Zhang et al.25 used Suzhou City as a case study to apply the combined ”PLUS-InVEST” model and Geodetector, examining the spatiotemporal evolution of land use and carbon storage over the past two decades, as well as under various future scenarios, while identifying the drivers of spatial differentiation. Zheng et al.26 integrated the PLUS and InVEST models to predict carbon storage changes in the coastal areas of Shandong Province by 2030 under different scenarios. The results indicated that, in all three scenarios—natural trend, construction land priority, and ecological priority—carbon storage was lower than the 2020 level, with the ecological priority scenario resulting in relatively higher carbon storage. Hu et al.27 used the PLUS and InVEST models to predict carbon storage in Jiangxi Province by 2030. The results suggest that, in all three scenarios, carbon storage decreased compared to 2020, with the ecological protection scenario having the most significant inhibitory effect on carbon storage reduction. It is evident that research on carbon storage, from the perspective of land-use change, is increasingly focusing on simulating future land-use scenarios and analyzing their impact on changes in carbon storage. However, carbon storage variations are influenced not only by land use changes but also by the combined effects of natural environmental and socioeconomic factors. Therefore, it is essential to explore further the combined effects of both natural and socioeconomic factors on carbon storage to gain a more comprehensive understanding of their driving forces.

The Fuhe River is one of the five major tributaries of the Poyang Lake Basin, characterized by a high forest coverage rate and rich biodiversity. It plays a crucial role in providing multiple ecological functions and maintaining the regional ecological balance. However, over the past 40 years, due to the rapid development of China’s socio-economy and the advancement of urbanization, the land use pattern in the Fuhe River basin has undergone significant changes, resulting in changes in regional carbon storage. An in-depth analysis of the impact of land use changes on carbon sequestration can provide valuable insights for sustainable development planning in the area. Therefore, this study integrates the PLUS and InVEST models to analyze the spatiotemporal distribution of carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin from 1980 to 2020. It also predicts changes in carbon storage for 2030 under three scenarios: natural development, ecological protection, and economic development. Additionally, the study employs the optimal parameters-based geographical detector (OPGD) to identify the driving factors of the spatial differentiation in carbon storage. This research provides scientific support for land use management, the implementation of low-carbon strategies, and the assessment of ecosystem carbon storage, thereby promoting local carbon emission reductions and the sustainable development of the ecological environment.

Materials and methods

Research framework

The research framework, as shown in Fig. 1, consists of four main steps: First, land-use data from 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020 were collected, and natural factors and socioeconomic data were integrated for data preparation. Next, the PLUS model was applied to simulate land use changes in 2020, validated against actual data, and projections for 2030 were made under three scenarios: natural development, ecological protection, and economic development. Then, using land use and carbon density data, the InVEST model was employed to assess carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin from 1980 to 2020 and predict carbon storage for the three future scenarios in 2030. Finally, the OPGD model was used to analyze the impact of natural and socioeconomic driving factors on the spatial differentiation of carbon storage.

The research framework (created by the Adobe Photoshop 2024, https://www.adobe.com/).

Overview of the study area

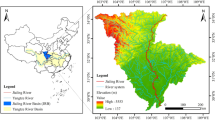

The Fuhe River Basin (115°36′-117°10′E, 26°30′-28°20′N), located in the eastern part of Jiangxi Province, is the second-largest tributary of the Poyang Lake Basin, with a total length of 349 km. The terrain of the basin slopes from south to north, extending towards Poyang Lake, and is traversed by the main river channel, which flows from south to north. The river originates from the western foothills of the Wuyi Mountains, in Guangchang County, Fuzhou City, Jiangxi Province, and the basin encompasses an area of 15,700 km2 (Fig. 2). The annual average precipitation in the basin is 1,767 mm, with an average temperature of 17.8 ℃. The region experiences a subtropical humid monsoon climate, characterized by warm and moist conditions, abundant rainfall, and sufficient sunshine. A variety of soil types are found in the basin, including red soils, paddy soils in inundation-prone areas, yellow-red soils, acidic purple soils, and yellow soils. The dominant vegetation types consist of subtropical coniferous forests and subtropical evergreen broadleaf forests.

Location map of the research region: (a) The location of Jiangxi Province within China; (b) The location of Fuhe River Basin within Jiangxi Province; (c) The digital elevation model (DEM) of Fuhe River Basin. The map originates from the China Surveying, Mapping, and Geographic Information Standard Map Service of the Map Technology Review Center, Ministry of Natural Resources, China (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.govcn/). This map was created via ArcGIS 10.8 (http://www.esri.com/).

Data sources

The land use data were sourced from the Data Center for Resources and Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, with a resolution of 30 m and an overall accuracy of exceeding 90%. The data were reclassified into six main categories: cultivated land, woodland, grassland, water, construction land, and unused land. Raster maps of land use were obtained for the years 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020. Other data sources for the PLUS simulation and driver exploration are shown in Table 1. Considering the spatial scale of the study area, various raster datasets were resampled to a uniform resolution of 30 m × 30 m to ensure consistent data accuracy across the study area.

Methods

InVEST model

The carbon storage component of the InVEST model was used to quantitatively evaluate and calculate carbon storage in the study area28. The total carbon storage of the study area was calculated using the following formula:

Where: \(\:i\) denotes the number of land use types; \(\:{C}_{i}\:\)represents the carbon storage of land use type \(\:i\); \(\:{C}_{i-above},{C}_{i-below},\:{C}_{i-soil}\:\)and \(\:{C}_{i-dead}\:\)represent the carbon storage in aboveground biomass, belowground biomass, soil, and dead organic matter for land use type \(\:i\), respectively. \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{total}}\) denotes the total carbon storage; \(\:{A}_{i}\:\)stands for the area of land use type \(\:i\); and \(\:\text{n}\) is the number of land use types, which is 6 in this study.

The carbon density coefficients are derived from adjustments based on climate information specific to the Fuhe River Basin and carbon density data from its surrounding areas. By the carbon density correction formulas proposed by Chen et al.29, Giardina and Ryan30, and Alam et al.31, which adjust the carbon density values of the study area by incorporating precipitation and temperature factors, the corrected carbon density values for the study area are provided in Table 2. Due to the difficulty in obtaining data on the carbon density of dead organic matter and its negligible proportion, it was assigned a value of 028.

Where: \(\:MAP\) represents the mean annual precipitation (mm), with values of 1652.27 mm for Jiangxi Province and 1728.63 mm for the Fuhe River Basin; \(\:MAT\) denotes the mean annual temperature for Jiangxi Province and the Fuhe River Basin, recorded as 19.02 °C for Jiangxi Province and 18.93 °C for the Fuhe River Basin; \(\:{C}_{SP}\) is the soil carbon density (kg/m2) based on mean annual precipitation, while \(\:{C}_{BP}\) and \(\:{C}_{BT}\) represent the biomass carbon density (kg/m2) based on mean annual precipitation and temperature, respectively; \(\:{K}_{BP}\), \(\:{K}_{BT}\), \(\:{K}_{B}\), and \(\:{K}_{S}\) denote the correction coefficients for biomass carbon density based on the mean annual precipitation factor, the mean annual temperature factor, the biomass carbon density correction coefficient, and the correction coefficient for soil carbon density, respectively; \(\:{C}^{{\prime\:}}\) and \(\:{C}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) represent the corresponding data for regions \(\:{C}^{{\prime\:}}\) and \(\:{C}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\), respectively.

PLUS model

The Patch-generating Land Use Simulation (PLUS) model is designed to simulate land use changes at the patch level and comprises two modules: the Land Expansion Analysis Strategy (LEAS) and the CA model based on Multiple Random Patch Seeds (CARS). The LEAS module employs a random forest classification algorithm to determine the probabilities of changes in land use types, thereby analyzing the relationship between driving factors and land use, while also calculating the partial expansion from the early to the late stages of land use. The module’s parameters were set as follows: the number of regression trees was 20, the sampling rate was 0.01, mTry was 5, and the thread was 3. The CARS module, based on a CA model with multiple random patch seeds, simulates spatial changes under complex scenarios23,32. Its parameters were as follows: the neighborhood size was 3, the thread was 3, the patch generation threshold was 0.5, the expansion coefficient was 0.1, and the percentage of seeds was 0.0001. The neighborhood weights for each land use type were calculated by determining the proportion of the expansion area of each land use type to the total land expansion, based on land expansion calculations33. These weights were as follows: 0.354 for cultivated land, 0.348 for woodland, 0.082 for grassland, 0.033 for water, 0.184 for construction land, and 0.001 for unused land.

This study first extracted the land use data for the Fuhe River Basin for 2000 and 2010 using the LEAS module, followed by simulating land use based on 15 driving factors. To evaluate the applicability of the PLUS model to the study area, the simulated land use data from 2020 were compared with actual data, using the Kappa coefficient and overall accuracy as validation metrics. Typically, a Kappa index value greater than 0.8 is considered statistically satisfactory32. The validation results indicate a Kappa coefficient of 0.905 and an overall accuracy of 95.30%, demonstrating satisfactory simulation accuracy. These results suggest that the PLUS model can effectively reflect the spatial variation patterns of land use in the Fuhe River Basin. Therefore, the PLUS model is suitable for simulating land use in the Fuhe River Basin and can be used to make land use predictions for 2030.

Setup of multi-scenario simulation

To comprehensively address the diverse developmental demands, this study refers to the “14th Five-Year Plan for the Ecological and Environmental Protection of Jiangxi Province” and the “Jiangxi Provincial Territorial Spatial Overall Planning (2021–2035)”, integrating these with the distribution of land types in the study area. Therefore, three scenarios are established to predict and analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of land use types and carbon storage.

The introduction of these three scenarios is as follows. Natural development scenario (NDS): Based on the evolution of land types in the Fuhe River Basin from 2010 to 2020, the land use demand of the Fuhe River Basin in 2030 under the natural development scenario is predicted using the Markov Chain of the PLUS model, without setting the probability of inter-conversion between each category. Ecological protection scenario (EPS): In line wiith the “14th Five-Year Plan for Ecological and Environmental Protection of Jiangxi Province,” this scenario prioritizes ecological principles and enhances ecological protection and restoration. The probability of converting woodland and grassland to construction land is reduced by 50%, the probability of converting cultivated land to construction land is reduced by 30%, and the probability of converting cultivated land and grassland to woodland is increased by 30%34. Economic development scenario (EDS): Based on the urban expansion objectives outlined in the “Jiangxi Provincial Territorial Spatial Overall Planning (2021–2035),” this scenario increases the probability of converting cultivated land, woodland, and grassland to construction land by 20%, while reducing the probability of converting construction land to cultivated land, woodland, grassland and water by 60%27. According to the scenario requirements, a land-use conversion cost matrix was constructed for the three scenarios in 2030 (Table 3).

Optimal parameters-based geographical detector model

Multiple factors, including topography, climate, vegetation, soil, and socio-economic conditions influence carbon storage in terrestrial ecosystems. In this study, 12 driving factors were selected: DEM (X1), slope (X2), aspect (X3), mean annual precipitation (X4), mean annual temperature (X5), NDVI (X6), NPP (X7), soil type (X8), soil erosion intensity (X9), population (X10), GDP (X11), and LUI (X12), to analyze the driving forces behind the spatial differentiation of carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin. Parameter optimization encompasses the spatial scale optimization of variables and the optimization of discretization parameters. First, five spatial scales (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 km) were constructed based on the study area and data resolution, and the optimal spatial discretization q-values for each driving factor were compared across different scales. The optimal spatial scale is determined when the 90% quantile of the q-value for all driving factors reaches its maximum value at 3 km (Fig. 3)35. Based on this, discretization parameter optimization was performed using classification methods such as equal breaks, natural breaks, quantile breaks, and geometric breaks, with the number of categories set between 4 and 10. The optimal parameter combination for analysis was selected by computing the factor detector and selecting the parameter set with the highest q-value. Finally, single-factor and interaction detectors were used to reveal the driving effects of each factor on the spatial differentiation of carbon storage36. The interaction detector can be utilized to detect the strength and type of factor interactions by contrasting the q-values with those of the factor detector (Table 4). The formula for calculating the q-value is as follows:

where \(\:{N}_{ℎ}\) and \(\:N\) represent the number of cells in zoning\(\:\:ℎ\) and the whole region, respectively, \(\:{\delta\:}_{ℎ}^{2}\) and \(\:{\delta\:}^{2}\) represent the variances of the landscape indices for zoning \(\:ℎ\) and the whole region, respectively, and\(\:\:L\) is the number of zoning. For \(\:q\:\)∈[0,1], the greater the \(\:q\) value, the stronger the impact of the factor on the regional differentiation of carbon storage, and vice versa.

Scale effects of explanatory variables based on OPGD models. (created by the WPS Office, https://www.wps.cn/).

Results

Land use change from 1980 to 2020

From 1980 to 2020, the primary land use type in the Fuhe River Basin was woodland, which accounted for more than 65% of the total study area (Fig. 4). Woodland was primarily distributed in the central, southern, and western regions of the basin, exhibiting a contiguous clustering pattern. Cultivated land was mainly concentrated in the plains of the northern and eastern regions of the basin. Grassland was predominantly distributed in the central areas and along the riparian zones of the basin, interspersed with woodland and cultivated land. Construction land was relatively dispersed but showed concentration in the northern and riparian regions of the basin. Water was distributed in a strip-like manner along the main river channel and around several lakes, flowing through the basin from south to north. From 1980 to 2020, the areas of cultivated land, woodland, grassland, and unused land decreased by 115.33 km2, 40.25 km2, 88.79 km2, and 0.93 km2, respectively. The proportion of cultivated land decreased from 27.9 to 27.16%, woodland from 65.9 to 65.63%, and grassland from 3.28 to 2.71%, while the proportion of unused land remained constant. Meanwhile, the areas of water and construction land increased by 28.08 km2 and 217.65 km2, respectively, with their corresponding proportions rising by 0.18% and 1.4%. Among all land use types, cultivated land saw the most significant decline in proportion, while construction land showed the largest increase.

Land use in the Fuhe River Basin, 1980–2020: (a) 1980; (b) 1990; (c) 2000; (d) 2010; (e) 2020 (created by ArcGIS 10.8, http://www.esri.com/).

In the past 40 years, cultivated land and woodland have been the primary sources of the rapid expansion of construction land in the Fuhe River Basin, with 127.14 km2 of cultivated land and 91.18 km2 of woodland converted into construction land (Fig. 5a). The largest conversion occurred between cultivated land and woodland, exceeding 200km2. Additionally, the transfer areas of grassland, water, and unused land are small, and the transfer patterns are not evident.

The complex and diverse land use transfer patterns in the Fuhe River Basin over the past 40 years are illustrated in Fig. 5b, showing the main land type transfers (with transfer areas greater than 20 km2) for analytical convenience. This includes the conversion of cultivated land and woodland to construction land, reciprocal conversions between cultivated land and woodland, woodland and grassland, as well as cultivated land and water. These types of land use transfer account for 92.29% of the total. The results indicate that the conversion of cultivated land and woodland into construction land was predominantly concentrated in the low-altitude regions of the northern part of the basin. In contrast, the conversion of grassland into woodland was primarily observed in the southern areas. Other types of land conversion occurred mainly in sporadic patches, with a relatively scattered distribution.

(a) Chord diagram of land use transfer from 1980 to 2020 (created by OriginLab Origin2021, https://www.originlab.com/). (b) Spatial distribution of the main land use transfer in the Fuhe River Basin (created by ArcGIS 10.8, http://www.esri.com/).

Temporal and Spatial distribution of carbon storage

Temporal variation characteristics of carbon storage

The carbon storage levels in the Fuhe River Basin were 2416.63 × 105 t, 2412.85 × 105 t, 2416.52 × 105 t, 2409.33 × 105 t, and 2396.24 × 105 t in 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020, respectively, indicating a reduction of 20.39 × 105 t in carbon storage from 1980 to 2020. From 2010 to 2020, the most significant decline in carbon storage was observed, with a decrease of 0.54%. From 1980 to 2000, the carbon storage across different land use types, ranked in descending order, was as follows: woodland, cultivated land, grassland, water, construction land, and unused land. From 2000 to 2020, a significant increase in carbon storage on construction land was observed, resulting in its to rise to the fourth position.

Spatial variation characteristics of carbon storage

In terms of spatial distribution, carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin has shown relatively minor changes over the past 40 years. High-carbon storage areas have predominantly been located in the central, southern, and western mountainous and hilly regions of the basin, which are closely associated with the spatial distribution of woodland and grassland. In contrast, low-carbon storage areas are mainly concentrated in the northern part of the basin and urbanized areas along the river (Fig. 6).

Carbon storage distribution pattern in the Fuhe River Basin from 1980 to 2020 (created by ArcGIS 10.8, http://www.esri.com/).

As shown in Fig. 7, from 1980 to 2020, approximately 93.82% of the region’s carbon storage remained essentially unchanged, while 3.66% of the area showed a decreasing trend, primarily in regions where construction land expanded. Conversely, 2.52% of the area exhibited an increasing trend in carbon storage, primarily concentrated in areas where woodland increased, particularly in the southern part of the basin. Overall, regions with changes in carbon storage exhibited characteristics of localized clustering and scattered distribution, which aligned with the spatial trends in land-use changes.

Distribution of carbon storage changes in Fuhe River Basin during different periods, (a) 1980–1990; (b) 1990–2000; (c) 2000–2010; (d) 2010–2020; (e) 1980–2020 (created by ArcGIS 10.8, http://www.esri.com/).

Carbon storage response to land use change

From 1980 to 2020, the conversion of woodland into other land use types resulted in a reduction of carbon storage by 37.66 × 105 t, primarily due to the conversion of high carbon-sequestration woodland into lower carbon-sequestration cultivated land and construction land, resulting in carbon storage losses of 16.96 × 105 t and 13.33 × 105 t, respectively. On the other hand, the expansion of woodland resulted in an increase in carbon storage of 28.77 × 105 t, mainly driven by the conversion of cultivated land and grassland into woodland. In contrast, the expansion of construction land resulted in a decrease in carbon storage of 23.45 × 105 t, mainly due to the conversion of cultivated land and woodland into construction land (Table 5). Overall, the decline in carbon storage was mainly attributed to the reduction in woodland area and the expansion of construction land.

LUCC and carbon storage changes under different future scenarios

The land use patterns across regions, compared to 2020, have followed mainly the development trends observed between 2010 and 2020 under NDS. The areas of cultivated land and woodland decreased by 43.76 km2 and 72.54 km2, respectively. In contrast, grassland, water, and construction land have increased by 25.3 km2, 0.76 km2, and 90.36 km2, respectively (Fig. 8). This suggests that under NDS, the loss of cultivated land and woodland is more pronounced. In contrast, a significant expansion of construction land is evident. Under EPS, the area of cultivated land experienced a substantial decline of 141.08 km², while woodland showed a growth trend, increasing by 46.9 km2. Additionally, the areas of grassland, water, and construction land continued to expand, increasing by 28.42 km2, 0.88 km2, and 65 km2, respectively. Although construction land continues to expand, its rate of expansion is slower than in NDS, suggesting that ecological protection policies have partially mitigated the loss of ecological land and slowed the expansion of construction land. Under EDS, both cultivated land and woodland decreased by 44.24 km2 and 94.69 km2, respectively, while grassland, water, and construction land saw increases of 22.6 km2, 0.73 km2, and 115.72 km2, respectively. This highlights that under EDS, intensified human activity and further socio-economic development have led to the most significant increase in construction land. At the same time, woodland has been significantly reduced, posing a considerable risk to ecological security.

Land use distribution in 2030, (a) 2030NDS; (b) 2030EPS; (c) 2030EDS (created by ArcGIS 10.8, http://www.esri.com/).

The spatial distribution patterns of carbon storage are not expected to change significantly (Fig. 9). By 2030, the projected carbon storage levels under NDS, EPS, and EDS are 2383.85 × 105 t, 2394.22 × 105 t, and 2380.42 × 105 t, respectively. Under NDS, carbon storage in both cultivated land and woodland is projected to decrease, with the most significant decline observed in woodland, totaling 13.23 × 105 t. EPS predicts the highest total carbon storage among the three scenarios, mainly due to an increase of 8.53 × 105 t in woodland carbon storage, resulting in a decrease of 2.02 × 105 t in total carbon storage compared to 2020. EDS has the lowest carbon storage, primarily due to a significant reduction in woodland carbon storage by 17.26 × 105 t, which results in a decrease of 15.82 × 105 t in total carbon storage compared to 2020. Additionally, under all three scenarios, carbon storage in grassland and construction land shows an upward trend, while carbon storage in water and unused land remains essentially unchanged. Overall, carbon storage shows a clear decreasing trend under NDS and EDS, with the most significant decrease occurring under EDS. In contrast, the decrease in carbon storage is effectively controlled under EPS.

Distribution of carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin under different future scenarios (created by ArcGIS 10.8, http://www.esri.com/).

Spatial drivers of carbon storage

The results of the single-factor detection of the OPGD (Fig. 10a) indicated that LUI, NDVI, elevation, and slope were the main driving factors influencing the spatial differentiation of carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin ecosystems, all with explanatory powers exceeding 19%. Explanatory powers for NPP, GDP, and population density ranged from 10 to 12%, indicating that they are secondary drivers. The explanatory power of soil erosion intensity was the lowest, at only 2%.

The results of the interaction factor detection for the OPGD (Fig. 10b) indicated that the interaction between any two factors showed a two-factor enhancement or a nonlinear enhancement. The impact of interaction was greater than that of any single factor, indicating that the spatial differentiation of carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin results from the combined effects of different factors. The q-value for the interaction between NDVI and slope was the highest, with explanatory power close to 33.6%. This was followed by the interaction between LUI and slope, with explanatory powers of 32.9%. Interactions between LUI, NDVI, elevation, and slope with other factors, although primarily exhibiting a two-factor enhancement, resulted in higher explanatory power, all exceeding 20%. In addition, although the explanatory power of the mean annual precipitation was small, its interaction with other factors demonstrated a nonlinear enhancement.

Factor detection and interactive detection results. (created by OriginLab Origin2021, https://www.originlab.com/).

Discussion

Effects of land use change on carbon storage

Land use has a significant impact on ecosystem carbon storage. The interconversion of land use types caused changes in vegetation and soil carbon sinks within the ecosystem, leading to changes in total regional carbon storage37,38. For example, an increase in land use types with high carbon density improves regional carbon storage, while the opposite reduces it.

It was found that land use change in the Fuhe River Basin from 1980 to 2020 led to a decrease in carbon storage, with varying trends across different periods. From 1980 to 1990, carbon storage showed a slight decline. Due to the conflict between ecological protection and food production, some woodlands, grasslands, and water areas with favorable agricultural conditions were converted into cultivated land, resulting in the transformation of land types with higher carbon sequestration capacity into those with lower capacity, which is consistent with the research view of Zhou et al.39. From 1990 to 2000, carbon storage showed a slight increase. During this period, the local government implemented a series of ecological engineering projects, such as the long-term defense forest project and the mountain reforestation project, which significantly enhanced the protection and restoration of woodland in the basin. The expansion of woodland was the primary contributor to the increase in carbon storage during this phase, compensating for the reduction in carbon sequestration caused by the decrease in grassland area, which is consistent with the study of Liu et al.40. Zhou et al.41 demonstrated that these ecological restoration projects not only halted the decline in ecosystem carbon sequestration capacity but also enhanced it on a larger scale in watershed ecosystems.

From 2000 to 2010, with the gradual implementation of ecological engineering projects, the area of woodland in the basin increased, but carbon storage continued to decline. The primary reason is that urbanization has accelerated the growth of construction land, which is broadly consistent with the study by Jiang et al.42. Meanwhile, the construction of reservoirs in the Fuhe River Basin during this period increased the water area, which also further reduced the carbon storage to a certain extent. Yogi et al.43 also confirmed that the increase in rivers and reservoirs with extremely low carbon density contributed to the decrease in carbon storage. Additionally, the reduction in the area of cultivated land and grassland further weakened the carbon sequestration capacity of the watershed ecosystem44.

From 2010 to 2020, carbon storage in the basin continued to decline, with the rate of decline increasing, mainly due to two factors. On the one hand, with population growth, the demand for cultivated land increased, leading to the conversion of previously abandoned cultivated land and certain shrublands on low hills and gentle slopes into cultivated land through land rearrangement. Tang et al.45 demonstrated that the loss of carbon storage resulting from the expansion of cultivated land is comparable to, or even exceeds, that caused by urban expansion. On the other hand, the expansion of construction land primarily encroached upon substantial ecological areas, such as cultivated land and woodlands, resulting in a decline in carbon storage. This is consistent with Bai’s study, which suggests that population growth and urbanization expansion will lead to a rapid decline in regional carbon storage46. In general, the decline in woodland area and the expansion of construction land have been the main reasons for the reduction in carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin over the past 40 years, consistent with the research of other scholars. For example, Huang et al.47, based on a study of Jiangxi Province, demonstrated that from 2000 to 2020, the reduction of woodland area and the expansion of construction land resulted in a decrease of 288.3 × 105 t in carbon storage. Similarly, Chen et al.48 observed that from 2000 to 2020, the decline in carbon storage in Guizhou Province was primarily attributed to the reduction in woodland area and the expansion of construction land. Therefore, the expansion of cities, encroachment of cultivated land on ecological land, and an increase in water areas will lead to a decline in carbon storage. However, the implementation of ecological engineering projects can effectively mitigate this trend.

This study simulated and predicted carbon storage under three scenarios for 2030, with results showing a decline in carbon storage under all three scenarios compared to 2020. Among them, carbon storage decreased the least under the EPS scenario, which is consistent with the research of other scholars. For example, Zheng et al.26 predicted changes in carbon storage under different scenarios for 2030, using the coastal areas of Shandong Province as a case study. The results showed that under the three scenarios—natural trend, construction land priority, and ecological priority—carbon storage was lower than in 2020, with the ecological priority scenario exhibiting the least reduction. Similarly, in a study of Pingxiang City, Jiangxi Province, Hu et al.49 found that carbon storage in the natural development, ecological protection, and economic development scenarios was lower than in 2020, with the ecological protection scenario having the most significant inhibitory effect on carbon storage reduction. Therefore, ecological protection should be prioritized in future planning as a key development strategy.

Driver factors of Spatial variation of carbon storage

The results of single-factor detection indicate that among socio-economic factors, LUI has the most significant influence on the spatial differentiation of carbon storage in the Fuhe River basin, which is consistent with the study of Ma et al.50. LUI significantly affects the spatial distribution of carbon storage by altering the carbon sequestration capacities of vegetation and soil. Additionally, natural factors such as NDVI, elevation, and slope have significant effects on the spatial differentiation of carbon storage, which is consistent with the study of Lai et al.51. In the hilly and mountainous regions of the upper basin, where higher vegetation cover facilitates carbon sequestration, the plains of the middle and lower reaches are dominated by cultivated land and construction land, which have lower vegetation cover and consequently lower carbon storage. Elevation and slope influence the spatial distribution of carbon storage by affecting the distribution of vegetation types and land use patterns. For example, due to the considerable topographic relief in the upper reaches, which limits large-scale agricultural and urban development, a larger area of forests and shrubs has been preserved, resulting in relatively higher carbon storage.

The interactive detection results indicate that the interaction between different driving factors enhances the influence on the spatial differentiation of carbon storage, with the interaction between NDVI and slope having the strongest explanatory power, consistent with the research of other scholars. For example, Li et al.52 demonstrated in their study of the Nanming River Basin that human activity intensity, NDVI, slope, population density, and lithology are the main factors influencing the spatial differentiation of carbon storage. The interaction between NDVI and slope contributed the most to this differentiation, accounting for nearly 30% of the explanatory power. Similarly, Wang et al.53 found that the synergistic effect of NDVI and slope was the most significant in the study of the Taihang Mountains, where it substantially increased regional carbon storage. Therefore, in practical applications, the interaction between different driving factors should be fully considered when addressing the spatial differentiation of carbon storage. For instance, in the measures to improve carbon storage in the Fuhe River basin, priority should be given to enhancing vegetation cover and optimizing slope management. Planting vegetation with strong adaptability and high carbon sequestration capacity at different altitude gradients can help achieve the goal of enhancing regional carbon sink capacity.

Additionally, although the explanatory power of mean annual precipitation for the spatial differentiation of carbon storage in the watershed is relatively low, at only 3.6%, its influence should not be overlooked. This is because its interactions with other factors exhibit nonlinear enhancement, indicating that the effect of mean annual precipitation on carbon storage spatial differentiation becomes more significant when it interacts with other factors, which is consistent with the research of other scholars. For example, Duan et al.54 demonstrated that in Qianjiangyuan National Park, climate factors alone had a minimal effect on the spatial distribution of carbon storage (only 4.5%). However, their interaction with other factors had a significant impact on the spatial differentiation of carbon storage. Thus, it is evident that various factors influence the spatial differentiation of carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin through different mechanisms. The impact on carbon storage in the basin is not simply the sum of multiple factors, but instead results from the integrated influence of multiple factors. Therefore, in order to achieve the “dual carbon” strategic goals in the future, it is essential to comprehensively consider the interaction and synergistic effect of each driving factor. To this end, differentiated, diversified, and precise regulatory strategies should be adopted, selecting land use approaches that align with the natural conditions of the watershed and its socio-economic development level55, while focusing on the interactions between key factors such as NDVI and slope, as well as land use intensity and slope.

Deficiencies and prospects

(1) To improve the alignment between the model simulation results and the actual conditions of the watershed, the carbon density was revised based on existing research findings. In contrast to the method used by some scholars, who directly apply national carbon density data, the results presented here are relatively more accurate. However, due to the lack of field validation data, the carbon density values may still contain some bias. Future research should integrate on-site sampling data and long-term dynamic monitoring data to optimize model parameters, thereby better adapting to local conditions, reducing errors, and improving the precision of the assessment results.

(2) Various actors, including natural environmental and socioeconomic factors, influence land use change. In this study, only 15 driving factors were selected to predict future land use patterns, without fully considering the impact of local policies on land use, which has, to some extent, affected the accuracy of the simulation results. Future research should incorporate quantitative indicators of relevant policies into the driving factor framework, thereby enhancing the comprehensiveness and precision of land use simulations and making the findings more relevant for practical guidance.

(3) The Geographical Detector analysis employed in this study may not fully capture the spatial variation characteristics of the driving factors. To more accurately capture these spatial differences, future research will explore alternative methods, such as the Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) model, to quantify the local regression coefficients of environmental factors. This will be combined with bandwidth optimization and spatial autocorrelation tests to systematically analyze the spatial gradient effects of climate, vegetation, topography, and other factors on soil carbon storage.

Conclusions and recommendations

Conclusions

Based on five periods of land use data from 1980 to 2020, along with natural factor data and socioeconomic data, an integrated modeling approach was employed, combining PLUS, InVEST, and OPGD models to simulate carbon storage under multiple scenarios for the Fuhe River Basin in 2030. This approach is more closely aligned with regional policy planning and actual conditions. Using 40-year-long time-series data, the model systematically analyzed the characteristics and spatial heterogeneity of land use and carbon storage changes in the region, identifying the driving mechanisms of carbon storage changes due to both natural and socioeconomic factors. The key findings of the study are as follows:

(1) Woodland is the primary land use type in the Fuhe River Basin, accounting for approximately 66%. From 1980 to 2020, the areas of cultivated land, woodland, and grassland in the region decreased significantly by 115.33 km2, 112.79 km2, and 88.79 km2, respectively, while the area of construction land increased by 217.65 km2. In 2030, under both the natural development scenario and the economic development scenario, the areas of cultivated land and woodland are expected to decrease continue decreasing significantly, while the area of construction land is projected to expand continue expanding. However, under the ecological protection scenario, the area of woodland will exhibit an increasing trend;

(2) From 1980 to 2020, the total carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin showed a decreasing trend, with a reduction of 20.39 × 10⁵ t. The primary drivers of this decline were the reduction in woodland area and the expansion of construction land. High-carbon storage areas have predominantly been located in the mountainous and hilly regions in the central, southern, and western parts of the basin. In contrast, low-carbon storage areas are mainly concentrated in the northern part of the basin and urbanized areas along the river.

(3) The distribution of carbon storage in 2030 under the different scenarios is not significantly different from that in 2020, although spatial variations are evident. The projected carbon storage levels under NDS, EPS, and EDS are 2383.85 × 105 t, 2394.22 × 105 t, and 2380.42 × 105 t, respectively. Despite a decline in carbon storage under all three scenarios, the EPS shows the most pronounced mitigating effect on reducing carbon storage. Therefore, future planning should prioritize development measures focused on ecological protection.

(4) LUI, NDVI, elevation, and slope are the most significant factors influencing the spatial differentiation of carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin. The interaction between any two factors exhibited a two-factor enhancement or a nonlinear enhancement effect on carbon storage spatial differentiation, with the interaction between NDVI and slope having the most significant influence, accounting for approximately 33.6% of the explanatory power.

Recommendations

To achieve sustainable management and ecological protection of carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin, optimize land use planning, and enhance ecosystem service functions, the following policy recommendations are provided based on the analysis of land use change, carbon storage scenarios, and the driving factors.

-

(1)

Strengthen the construction and management of ecological protection zones.

The woodland areas in the Fuhe River Basin account for about 65% of the total area, with the western and southern mountainous regions being the primary high-carbon storage areas. Due to the natural conditions of these areas (such as higher altitudes and steep slopes), the level of development and cultivation remains relatively low. To effectively protect these key carbon sinks, it is recommended that ecological protection in these mountainous areas be further strengthened, the coverage of ecological protection zones be expanded, and human interference be reduced. Additionally, fine-grained management of existing protected areas should be implemented to ensure ecosystem stability and maintain long-term carbon storage.

-

(2)

Optimize agricultural land use structure.

Changes in agricultural land use have a significant impact on carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin, particularly as excessive development and improper cultivation can result in a loss of carbon storage. To achieve sustainable management of carbon storage, it is recommended that a series of sustainable agricultural land-use policies be implemented to promote land reclamation and intensify agricultural development. Specific measures include strengthening agricultural ecological compensation mechanisms, encouraging farmers to adopt eco-friendly agricultural practices such as organic and ecological farming, reducing the impact of agricultural expansion on carbon storage; promoting land reclamation to restore the ecological functions of degraded land and enhance carbon storage; and facilitating the intensification of agriculture to improve land use efficiency and avoid haphazard cultivation.

-

(3)

Strengthen construction land control and spatial planning.

The expansion of construction land is one of the main factors contributing to the decline in carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin. To effectively mitigate the impact of construction land expansion on carbon storage, it is recommended that strict land-use control be implemented and spatial planning be optimized. Specific measures include: strengthening control over urban and rural construction land, particularly in the core areas of the basin and the high-carbon storage mountainous regions in the west and south, with strict limitations on unnecessary development; optimizing land use structure, reasonably planning construction land, reducing unnecessary construction, and avoiding damage to ecosystems such as forests and wetlands; improving the environmental quality of construction land, promoting green and low-carbon building development, increasing urban and rural green spaces and public areas, and encouraging eco-friendly low-carbon development models.

-

(4)

Enhance ecological restoration and carbon sink function.

To address the challenge of declining carbon storage in the Fuhe River Basin, it is recommended that a series of comprehensive ecological restoration measures be implemented to enhance carbon sink functions. The focus should be on restoring important ecosystems such as forests, wetlands, and grasslands, particularly through natural regeneration and afforestation, to increase carbon storage and biodiversity. When implementing ecological restoration projects, priority should be given to areas with high carbon storage potential, particularly in the western and southern mountainous regions of the basin, with a focus on restoring forests and other key ecosystems to enhance their carbon sink capacity. Furthermore, promoting low-carbon sustainable development models such as ecological agriculture and eco-tourism, supporting ecological restoration projects through economic means, and providing necessary financial support for restoration work through ecological compensation policies is also recommended.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article .

References

Siqin, Z. et al. Carbon dioxide emissions, urbanization level, and industrial structure: empirical evidence from North China. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 29, 34528–34545 (2022).

Lempert, R. Measuring global climate risk. Nat. Clim. Change. 11, 805–806 (2021).

Fang, J. et al. Global warming, human-induced carbon emissions, and their uncertainties. Sci. China Earth Sci. 54, 1458–1468 (2011).

Cramer, W. et al. Climate change and interconnected risks to sustainable development in the mediterranean. Nat. Clim. Change. 8, 972–980 (2018).

Mallapaty, S. How China could be carbon neutral by mid-century. Nature 586, 482–483 (2020).

Ren, S. et al. Historical impacts of grazing on carbon stocks and climate mitigation opportunities. Nat. Clim. Change. 14, 380–386 (2024).

Liang, Y. et al. Integrated assessment of land use/land-cover dynamics on carbon storage services in the loess plateau of China from 1995 to 2050. Ecol. Indic. 120, 106939 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Effects of land use and land cover change on soil organic carbon storage in the Hexi regions, Northwest China. J. Environ. Manag. 312, 114911 (2022).

Chang, X. et al. Effects of land use and cover change (LUCC) on terrestrial carbon stocks in China between 2000 and 2018. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 182, 106333 (2022).

Chave, J. et al. Tree allometry and improved Estimation of carbon stocks and balance in tropical forests. Oecologia 145, 87–99 (2005).

Wu, H. & Xu, H. Remote sensing retrieval and calibration of forest vegetation carbondensity based on Time-series data. For. Resour. Manag. 6, 43–51 (2021).

Zhao, H., Guo, B. & Wang, G. Spatial–Temporal changes and prediction of carbon storage in the Tibetan plateau based on PLUS-InVEST model. Forests 14, 1352 (2023).

Zhang, M., Liu, M., Chang, Q., Liu, H. & Zhang, J. Spatial distribution of organic carbon in topsoil of the loess tableland in Shaanxi Province during 1985–2015. J. Nat. Resour. 33, 2032–2045 (2018).

Zhang, G. Spatial distribution characteristics of carbon storage of urban forests in Shanghai based on remote sensing Estimation. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 30, 1777–1786 (2021).

Fu, Y. et al. Dynamic simulation and prediction of carbon storage based on land use/land cover change from 2000 to 2040: A case study of the Nanchang urban agglomeration. Remote Sens. 15, 4645 (2023).

Wang, Z., Zeng, J. & Chen, W. Impact of urban expansion on carbon storage under multi-scenario simulations in wuhan, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 45507–45526 (2022).

Li, Y. & Luo, H. Spatiotemporal evolution and Multi-scenario simulation of carbonstorage in karst regions of central Guizhou province: taking pudingcounty as an example. Environ. Sci. 45, 961–973 (2024).

Piyathilake, I. D. U. H., Udayakumara, E. P. N., Ranaweera, L. V. & Gunatilake, S. K. Modeling predictive assessment of carbon storage using invest model in Uva province, Sri Lanka. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8, 2213–2223 (2022).

Wang, Y., Cao, L., Wang, Y., Zhu, S. & Fang, X. Impact of land use/land cover on terrestrial carbon storage in Jiangxi. Remote Sens. Inform. 38, 96–105 (2023).

Zhu, L., Song, R., Sun, S., Li, Y. & Hu, K. Land use/land cover change and its impact on ecosystem carbon storage in coastal areas of China from 1980 to 2050. Ecol. Indic. 142, 109178 (2022).

Jiang, W., Deng, Y., Tang, Z., Lei, X. & Chen, Z. Modelling the potential impacts of urban ecosystem changes on carbon storage under different scenarios by linking the CLUE-S and the invest models. Ecol. Model. 345, 30–40 (2017).

Wang, N. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics and driving factors of county-level carbon storage in the loess plateau: A case study in Qingcheng county, China. Ecol. Indic. 144, 109460 (2022).

Liang, X. et al. Understanding the Drivers of Sustainable Land Expansion Using a patch-generating Land Use Simulation (PLUS) Model: A Case Study in Wuhan, China85101569 (Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 2021).

Fu, S., Zhen, Z., Zhou, H., Wang, B. & Qiao, Q. Spatio-Temporal evolution and prediction of carbon storage at the source of the Fen river and Sanggan river based on a PLUS-InVEST model. Front. Environ. Sci. 12, 1449576 (2024).

Zhang, Z., Liu, J., Zhang, Q., Chen, C. & Yang, Z. Analysis of Spatial-Temporal variation and driving forces of carbon storage in Suzhou City based on the PLUS-InVEST-Geodector model. Environ. Sci. 46(5), 2963–2975 (2024).

Zheng, H. & Zheng, H. Assessment and prediction of carbon storage based on land use/land cover dynamics in the coastal area of Shandong Province. Ecol. Indic. 153, 110474 (2023).

Hu, S. et al. Temporal and Spatial evolution and prediction of ecosystem carbon storage in Jiangxi Province based on PLUS-InVEST model. Env Sci. 45, 3284–3296 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Impact of land use type on the stability and organic carbon content of soil aggregates in the Weibei dryland. Environ. Sci. 40, 3361–3368 (2019).

Chen, G. et al. Research review on total below ground carbon A location in forest ecosystems. J. Subtrop. Resour. Environ. 2, 34–42 (2007).

Giardina, C. P. & Ryan, M. G. Evidence that decomposition rates of organic carbon in mineral soil do not vary with temperature. Nature 404, 858–861 (2000).

Alam, S. A., Starr, M. & Clark, B. J. F. Tree biomass and soil organic carbon densities across the Sudanese woodland savannah: A regional carbon sequestration study. J. Arid Environ. 89, 67–76 (2013).

Li, C. et al. Multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service value for optimization of land use in the Sichuan-Yunnan ecological barrier, China. Ecol. Indic. 132, 108328 (2021).

Li, C., Gao, B., Wu, Y., Zheng, K. & Wu, Y. Dynamic simulation of landscape ecological risk in mountain towns based on PLUS model. J. Zhejiang A&F Univ. 39, 84–94 (2022).

Huang, T. & Liu, S. Evaluation of land use change and carbon storage in Fujian provincebased on PLUS-InVEST model. J. Soil Water Conserv. 38, 246–257 (2024).

Song, Y., Wang, J., Ge, Y. & Xu, C. An optimal parameters-based geographical detector model enhances geographic characteristics of explanatory variables for Spatial heterogeneity analysis: cases with different types of Spatial data. GIScience Remote Sens. 57, 593–610 (2020).

Wang, J., Xu, C. & Geodetector Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 72, 116–134 (2017).

Liu, W., Yan, Y., Wang, D. & Ma, W. Integrate carbon dynamics models for assessing the impact of land use intervention on carbon sequestration ecosystem service. Ecol. Indic. 91, 268–277 (2018).

Kong, J., Du, Y., Yang, R. & Su, Y. Prediction of land use change and Lts influence on carbon stocks in themiddle reaches of Heihe river. J. Desert Res. 39, 87–97 (2019).

Zhou, W. et al. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity and driving forces of carbon storage in the Dongting lake basin. Chin. Environ. Sci. 44 (4), 1851–1862 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Response of carbon storage to land use change and multi-scenario predictions in Zunyi. China Sci. Rep. 15, 236 (2025).

Zhou, J. et al. Impacts of ecological restoration projects on the ecosystem carbon storage of inland river basin in arid area, China. Ecol. Indic. 118, 106803 (2020).

Jiang, H. et al. Impacts of land use change on carbon storage in the Guangxi Beibu Gulf economic zone based on the PLUS-InVEST model. Sci. Rep. 15, 6468 (2025).

Yogi, F., Stanganini, F. N., Tonello, K. C. & Isa, S. S. Evaluation of the potential for carbon sink and association with land occupation. J. Water Clim. Change. 14, 401–420 (2023).

Willcock, S. et al. Towards regional, error-bounded landscape carbon storage estimates for data-deficient areas of the world. PloS One. 7, e44795 (2012).

Tang, L., Ke, X., Zhou, T., Zheng, W. & Wang, L. Impacts of cropland expansion on carbon storage: A case study in hubei, China. J. Environ. Manage. 265, 110515 (2020).

Bai, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal variation and dynamic simulation of carbon stock based on PLUS and invest models in the Li river basin, China. Sci. Rep. 15, 6060 (2025).

Huang, Y. et al. Evolution and Multi-Scenario prediction of land use and carbon storage in Jiangxi Province. Forests 14, 1933 (2023).

Chen, D. et al. Analysis of carbon stock evolution and Lts vulnerability characteristicsbased on land use change in Guizhou Province. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 43, 301–309 (2023).

Hu, S., Le, X. & Xu, Y. Estimating terrestrial Eco-System carbon stock changes caused by Multi-Scenarios land use changes based on the FLUS Model-A case study of pingxiang, Jiangxi. Res. Soil. Water Conserv. 31, 299–309 (2024).

Ma, J. et al. Spatial-temporal evolution of carbon storage and its driving factors in the Shanxi section of the yellow river basin, China. Ecol. Model. 502, 111039 (2025).

Lai, J. et al. Exploring the Spatiotemporal variation of carbon storage on Hainan Island and its driving factors: insights from invest, FLUS models, and machine learning. Ecol. Indic. 172, 113236 (2025).

Li, Y. & Geng, H. Spatiotemporal trends in ecosystem carbon stock evolution and quantitative attribution in a karst watershed in Southwest China. Ecol. Indic. 153, 110429 (2023).

Wang, C., Luo, J., Qing, F., Tang, Y. & Wang, Y. Analysis of the driving force of Spatial and Temporal differentiation of carbon storage in Taihang mountains based on invest model. Appl. Sci. 12, 10662 (2022).

Duan, B., Feng, Q., Yuan, Y. & Li, P. Ecosystem services Trade-offs and synergies in Qianjiangyuan NationaPark system pilot. Tourism Sci. 35, 11–31 (2021).

Shi, J. et al. Spatial-Temporal evolution and prediction of carbon storage in Jiuquan City ecosystem based on PLUS-InVEST model. Env Sci. 45, 300–313 (2024).

Acknowledgements

we express our gratitude to anonymous reviewers and editors for their professional comments and suggestions.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32460432); Open Research Foundation of Jiangxi Academy of Water Science and Engineering (Grant No. 2023SKLS01); the Science and Technology Program of the Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education (Grant No. GJJ210425);

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.C. and K.W.; methodology, Z.C., L.H. and C.Y.; software, Z.C.; validation, Z.C.; formal analysis, Z.C.; investigation, Z.C.; data curation, Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.C.; writing—review and editing, Z.C. and S.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Wei, K., Hu, L. et al. Spatiotemporal variation and driving forces of carbon storage in the Fuhe river basin, China. Sci Rep 15, 30224 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14518-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14518-7