Abstract

Europium (Eu) has two naturally stable isotopes (151Eu and 153Eu). The Eu anomalies produced by feldspar crystallization during magma differentiation have provided valuable geochemical information for understanding the evolutionary history of magma in the crust-mantle system. Recently, the correlation between the degree of Eu isotope fractionation (δ153Eu) and the magnitude of the Eu anomaly produced by magma differentiation has received much attention as a new research field for understanding the evolution of the Earth system1,2,3,4. Here, we report large variation of Eu isotope ratio for geochemically mafic volcanic rocks from the Korean Peninsula and Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) site 801 C, western Pacific Ocean. The Eu isotope ratio in this work was determined precisely via multicollector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry using a Sm internal standard5,6,7. We find that the δ153Eu values of hydrothermally altered alkaline mafic volcanic rocks vary from − 0.65‰ to -0.1‰, in contrast to the narrow range that characterizes the primary fresh subalkaline mafic volcanic rocks (from − 0.1‰ to 0.1‰). Our findings indicate that Eu isotope fractionation can occur through not only magmatic differentiation but also hydrothermal reactions in the Earth system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rare earth element (REE) geochemistry has provided critical constraints on the geochemical evolution of the Earth system8,9,10,11,12,13,14. In addition, europium (Eu), an REE, exists in both divalent and trivalent states under magmatic redox conditions. This geochemical property makes it possible to produce a positive or negative Eu anomaly in igneous rocks because of feldspar crystallization, oxygen fugacity and temperature variation during magma differentiation10,11,12,13,14.

Stable isotope fractionation in rocks, which is controlled primarily by differences in their masses and/or by the temperature of the environment, has provided valuable information for understanding geochemical processes in the Earth system. For example, stable isotope fractionation from multivalent elements such as Ti, V, Fe and Ce, or monovalent elements such as Zr and Zn, has been used as a potential redox proxy in magmatic systems15,16,17,18,19,20. For example, stable Zr isotopes have the potential to provide constraints on primary processes, such as magmatic differentiation, crustal evolution and deep Earth processes19,20. In addition, Millet et al.17 reported that highly fractionated igneous rocks are significantly enriched in heavy Ti isotopes relative to more primitive magmatic rocks and that such enrichment is correlated with the SiO2 content. The authors inferred that such a correlation between enrichment in heavy Ti isotopes and the SiO2 content resulted from the fractional crystallization of Ti-bearing oxides. These results indicate that evolved, felsic igneous rocks are enriched in heavier Zr and Ti isotopes compared to juvenile, mafic rocks17,18,19,20. Dauphas et al.16 proposed the possibility of Eu isotope variation in bulk rocks and individual minerals due to redox conditions in the mantles of the Earth and other planets. In particular, Lee et al.4 reported that there can be a systematic correlation between Eu isotope fractionation and specific geochemical features, such as Eu anomalies, in the Earth system. Eu has two stable isotopes: 151Eu (47.81% natural abundance) and 153Eu (52.19% natural abundance)21. Because 151Eu changes to 147Pm by α decay and has an extremely long half-life (T1/2=5 × 1018yr22), 151Eu can be considered a stable isotope in the Earth system.

Heavy metal isotope fractionation in redox reactions is temperature dependent; thus Eu may undergo isotope fractionation in the Earth system23. Although there are few data on Eu isotope fractionation in the Earth system, the possibility of Eu isotope fractionation in igneous rocks has recently been reported1,2,3,4,5,6. Specifically, Lee and Tanaka1 first reported Eu isotope fractionation in highly fractionated igneous rocks with large negative Eu anomalies. Schauble2 suggested that Eu isotope fractionation can be produced by plagioclase crystallization. Furthermore, Lee et al.4 reported a correlation between the Eu isotope ratios and Eu anomalies in igneous rocks, which might be evidence that Eu isotope fractionation is produced primarily by feldspar crystallization during magma differentiation. This finding is consistent with Schauble’s suggestion2. Furthermore, the chondrite-normalized REE patterns and Eu isotope ratios in recently reported feldspar SRMs strongly suggest that Eu isotope fractionation in igneous rocks is primarily a result of magma differentiation24. Hu et al.3 proposed that Eu isotope fractionation is likely produced by reactions with hydrothermal solutions during magma differentiation. This indicates that the specific causal mechanism of Eu isotope fractionation remains unclear and controversial. Generally, alkali volcanic rocks are SiO2-undersaturated and usually carry strong indicators related to CO225–27. Some alkali volcanic rocks contain evidence of alteration signatures such as high loss-on-ignition (LOI) concentrations28 and alteration minerals. Therefore, mafic alkali volcanic rocks that contain large quantities of carbonatite-like minerals with high LOI concentrations may be excellent materials for verifying the effects of hydrothermal activity on Eu isotope fractionation. Alkali basaltic rocks containing carbonate minerals and high LOI content were recently reported from drill cores from Ulleung Island in the Korean Peninsula25 (Fig. S1).

At present, the study of Eu isotope fractionation is in its initial stages, with a series of studies underway1,2,3,4,5,6,7; and variations in the Eu isotopic composition in the Earth system are not well characterized. Previous studies have shown that Eu isotope fractionation rarely occurs in igneous rocks of primitive magma origin4,6. Moreover, the effects of hydrothermal reactions on Eu isotope fractionation3 are still unclear. A series of recent successive research1,2,3,4,5,6,7 suggest that there is a need to more clearly determine whether Eu isotope fractionation occurs only through magma differentiation in the mantle-crust system or also through hydrothermal alteration and redox reactions. Furthermore, the LOI concentration can serve as a useful indicator of alteration of volcanic rocks or calcitization of mafic minerals28.

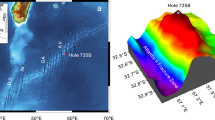

To understand and clarify cause of Eu isotope fractionation, here, we report Eu isotope data for 57 mafic volcanic rocks, which consist of subalkaline basaltic rocks to highly altered alkali basaltic rocks from the Korean Peninsula (including Ulleung Island mafic volcanic rocks), Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Site 801 C at the Pigafetta Basin of the Western Pacific Ocean including 10 geochemical reference materials (GRMs, for comparison, we included 4 andesitic GRMs). In this study, we show, based on geochemical characteristics including Eu isotope ratio, that the Eu isotope fractionation in the Earth system may have occurred through a hydrothermal reaction as well as magma differentiation.

Methods

Digestion

The sample digestion procedure was based on the approach of Lee et al.29 The HF, HNO3 and HCl used in sample decomposition were commercially available ultrapure reagents (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), except for the subboiled high-purity perchloric acid (HClO4, Merck). Approximately 100–200 mg of each sample powder was decomposed into a 2:1 mixture of 2–4 mL of concentrated HF (29 M) and 1–2 mL of concentrated HNO3 (16 M) at approximately 160 °C for more than 72 h in a 15 mL Savillex vial. After the addition of 0.1–0.2 mL of concentrated HClO4, the decomposed sample solution was heated to dryness at approximately 180 °C for more than 1 day. The samples were dried again and diluted in 10 mL of 6 M HCl as a stock solution to determine the REE concentration and Eu isotope ratio. Among the 10 mL stock solution, 0.5 mL was used to determine the REE concentrations, and the remainder was used for Eu isotope analysis.

Major and rare Earth element analysis

The major element abundances in this study were analyzed by X-ray fluorescence (XRF, SHIMADZU VF-320 A) at the Geoanalysis Center of the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (KIGAM). REE analyses also were performed via inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, NexION350, Perkin Elmer) at the KIGAM. Although the Eu anomalies of the 10 geochemical reference rocks from the USGS and GSJ have previously been characterized, we reanalyzed their REE abundances for comparison with those of the mafic volcanic rocks in this study (Supplementary Tables S1-1–S1-5). The analytical and experimental procedures for analyzing the REE concentrations (standard reagents and oxide calibration methods, ICP-MS measurement conditions, etc.) are described in Lee et al.29 Analytical uncertainties were 3 ~ 5% for major elements. The analyzed REE data from the geochemical reference sample powders agreed with the recommended values within 5 ~ 10% (Figs. S2-S6).

Eu separation

For Eu isotope ratio analysis, 9.5 mL of stock solution that remained after REE analysis was redried at 140 °C. The resulting dried cake was subsequently redissolved in 4 mL of 2 M HCl. Hydroxyisobutyric acid (HIBA) with a cation-exchange resin is very useful for separating high-purity Eu from other REEs5,7. The REE fraction for Eu purification was separated via precleaned cation exchange chromatography (Bio-Rad AG50W-X8 resin, 200–400 mesh; 0.5 cm × 17 cm column) using 40 mL of 6 M HCl after removing other matrix elements. After drying with a 6 M HCl elute, the dried REE fraction was redissolved in 50 µL of deionized water (DIW) and placed on a cation-quartz exchange column (AG50W-X8 resin, 200–400 mesh; 0.3 cm × 9.8 cm column) filled with 0.8 mL of the cation-exchange resin (Bio-Rad AG50W-X8 resin, 200–400 mesh). Eu was separated from the obtained REE fraction via the addition of 0.12 M 2-hydroxyisobutyric acid (HIBA), and the pH was adjusted to ~ 4.60. After elution, the Eu fraction was checked for remnants of neighbouring elements such as a Sm and Gd, to minimize isobaric interference7.

Mass spectrometry

Eu isotope ratios were measured via multi collector inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (MC-ICP-MS; Neptune Plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific Ltd.) in static mode with nine Faraday cups at the KIGAM. The 147Sm(L4), 149Sm(L3), 150Sm(L2), 151Eu(L1), 152Sm(C), 153Eu(H1), 154Sm(H2), 155Gd(H3), and 157Gd(H4) isotopes were monitored simultaneously using nine Faraday cups for Sm normalization and Gd interference correction by the Gd matrix7. Data acquisition consisted of 1 block of 50 cycles with an integration time of 4.194 s, and the sample aspiration rates were 80–100 µL/min. Blanks were checked during, before, and after each sample measurement. A Sm solution for doping for Eu isotope measurements was prepared from ultrapure Sm2O3 produced by Alfa Aesar. Sample dilution for Eu isotope measurement via MC-ICP-MS was performed with 2% HNO3 which was prepared from 60% ultrapure HNO3 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and DIW (Milli-Q system, Millipore, Milford, USA). We used a diluted solution of NIST 3117a (10,000 µg/mL, Lot No. 120705) as an in-house standard solution for comparison of the Eu isotope ratios.

Correction for mass-dependent isotope fractionation

Incomplete Eu purification due to the very low abundance of Eu and the remarkable concentration difference between Gd and Eu in these rocks makes ultrahigh-purity separation of Eu fraction difficult. This incomplete Eu purification results in isobaric interference with 154Sm by 154Gd in Sm normalization during Eu isotope ratio measurements via MC-ICP-MS using Sm internal standardization5. However, Lee and Tanaka7 also showed that the Gd matrix in the purified Eu fraction can influence the Eu isotope ratio results when a Sm internal standard is used. To determine Eu isotope ratios in geological samples, these authors recommend the use of the 147Sm-149Sm isotope pair instead of 150Sm-154Sm isotope pair to remove Gd matrix effect from the 154Gd isobar. Therefore, in this study, we used the Eu isotope ratio determined by normalization via the 147Sm-149Sm isotope pair for the samples with a Gd matrix effect less than 0.1% against 154Sm. In addition, for comparison, we also added the δ153/151Eu values of the igneous rocks normalized by other Sm isotope pairs (for example, 147Sm-152Sm, 147Sm-154Sm, 149Sm-154Sm, and 150Sm-154Sm) including the δ153/151Eu values without normalization (Supplementary Tables S2-1–S2-4).

In this work, the Eu isotopic composition is reported using the conventional delta notation in per mil relative to the National Institute of Standards and Technology reference standard NIST3117a, where

Results

Mineralogical and geochemical characteristics of the mafic volcanic rocks

The samples used in this work are mafic volcanic rocks from Ulleung Island, Jeju Island and Baekdusan (Changbaishan) in Korea and ODP Site 801 C in the Pigafetta Basin of the western Pacific Ocean. The mafic volcanic rocks in this work have been well characterized in the literatures30,31,32,33. These mafic volcanic samples have lithologies belonging to alkaline mafic volcanic rocks (basanites–trachybasalt–basaltic trachyandesite) to subalkaline mafic volcanic rocks (basalt–basaltic andesites) according to a total-alkali-silica (TAS) diagram34 (Fig. 1a). The chondrite-normalized REE patterns (Supplementary Figs. S2–S5) for the mafic volcanic rocks from Jeju Island, Ulleung Island and Baekdusan including GRMs show ocean island basalt (OIB)-like intraplate volcanic activity in Northeast Asia, whereas those from ODP Site 801 C indicate OIB to normal mid-ocean ridge basalt (N-MORB) type basaltic rocks (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Most of the samples from Ulleung Island (red open rectangle in Fig. 1), Jeju Island (black solid circles in Fig. 1) and two samples (blue open rectangles in Fig. 1) from the western Pacific area belong to alkaline series volcanic rocks with relatively high total alkali contents (Na2O + K2O = 5.18–11.9 wt%), whereas most Baekdusan samples (green solid circles in Fig. 1), GRMs and a few samples from Jeju Island are classified as subalkaline series (Fig. 1a).

(a) TAS classification diagram of Na2O + K2O versus SiO234, (b) LOI concentration (wt%) versus SiO2 for mafic volcanic rocks, which include geochemical reference materials (GRMs), and rocks from Ulleung Island, Baekdusan (Changbaishan) and Jeju Island from Korea and ODP Site 801 C in the Pigafetta Basin, western Pacific Ocean. Mafic volcanics, which include GRMs (yellow solid circles with black outlines) and Baekdusan samples (green solid circles with black outlines) are included in the subalkaline series, whereas most Ulleung Island mafic volcanic rocks (red open rectangles) are included in the alkaline series, except for a few samples. The other samples, including those from Jeju Island, plot in the boundary area between the alkaline and subalkaline series (red dotted line) suggested by Irvine and Baragar35. In the TAS diagram, SiO2 values are recalculated to 100% on an H2O- and CO2-free basis whereas the SiO2 values in (b) are values measured via X-ray fluorescence (XRF).

The Ulleung Island samples and 4 of the ODP Site 801 C samples have LOI concentrations greater than 4 wt%, indicating that they were affected by hydrothermal solutions (Fig. 1b).

The Ulleung Island samples with high LOI contents (> 4 wt%) have carbonate minerals that are visible in thin sections and are likely due to a high degree of hydrothermal alteration by CO2-rich fluid25,26,27,28(Fig. 2). In particular, the mafic volcanic rocks from Ulleung Island have porphyritic textures with phenocrysts of mainly large and automorphic carbonatitic minerals (15 vol%) and biotites (15 vol%, 200–1000 μm) (Fig. 2a and b). These automorphic carbonatitic phenocrysts contain small amounts of alteration minerals and consist of automorphic rectangular Mg-rich calcites (red outline line in Fig. 2c) and large particle Fe-rich calcites (Fig. 2d). Calcites with different compositions exist in these carbonatitic globules; these calcites include mainly Mg-rich and Fe-rich calcites, and the quantity of Fe-rich calcites is obviously much greater than that of Mg-rich calcites (Fig. 2c and d).

These mineralogical and geochemical characteristics of the Ulleung Island mafic volcanic rocks indicate that they are optimum samples for studying Eu isotope fractionation via reactions with hydrothermal solutions during magma differentiation due to the presence of carbonate phases, which provide evidence of the circulation of highly volatile components. In addition, although the samples from ODP Site 801 C do not exhibit any evidence of carbonate phases, high LOI concentrations (> 4.48 wt%) also indicate that they were affected by reactions with hydrothermal solutions or seawater.

(a) Energy dispersive spectroscopy X-ray image of a Ulleung Island volcanic rock (the green part represents biotite; the blue part represents carbonatitic xenocrysts), (b) energy dispersive spectroscopy X-ray image of automorphic biotite (green part) and apatite phenocryst (yellow part), (c) energy dispersive spectroscopy X-ray image of hexagonal carbonatitic xenocryst (Mg-rich ankerite is shown by red outlines), (d) energy dispersive spectroscopy X-ray image of a columnar carbonatitic xenocryst (the yellow part represents Fe-rich ankerite; the green part represents Mg-rich ankerite).

Eu anomalies and Eu isotope ratios in basaltic rocks

The chondrite-normalized REE patterns of the geochemical reference materials are shown in Fig. S2. Most GRMs have weak negative (BCR2, JB1b, JB2, JB3 JA1 and JA2) or weak positive (BHVO2, BIR1a and AGV2) Eu anomalies, regardless of the depletion of light rare earth elements (LREEs) or heavy rare earth elements (HREEs), except for JA3. JA3 shows a slightly large negative Eu anomaly ([Eu]N/[Eu]N*= 0.82).

Chondrite-normalized REE patterns for local (Korea and Western Pacific) mafic volcanic rocks are shown in Figs. S3 − S6. Most Korean mafic volcanic rocks except Western Pacific Ocean volcanic rocks are enriched in LREEs relative to HREEs, and have no Eu anomalies or weak positive Eu anomalies (see Figs. S3 − S5), which are similar to OIB. However, mafic volcanic rocks from the western Pacific ocean have two different types of REE patterns (Fig. S6); one is similar to the OIB, and the other type is to the N-MORB, which are relatively depleted LREEs and have low REE fractionations.

The δ153Eu value of the GRMs range from − 0.1 to + 0.1‰36. In this work, the δ153Eu values of the Jeju Island (black solid symbols in Fig. 3) and Baekdusan volcanic rocks (green solid symbols in Fig. 3) range from − 0.08 to + 0.1‰, similar to that of GRMs. However, the δ153Eu values of mafic volcanic rocks from Ulleung Island (red rectangle symbols) and western Pacific Ocean (blue rectangle symbols) vary from − 0.60 to + 0.04‰, which are highly enriched in lighter Eu isotope (151Eu). In Fig. 3, it should be pointed out the relationship between the Eu isotope ratios and the Eu anomaly of the Ulleung Island mafic volcanic rocks.

Discussion

The REE patterns, and La/Sm and Sm/Yb ratios in most of the mafic volcanic rocks in this work are similar to the compositions of OIB (Supplementary Figs. S2–S6) including no or weakly positive/negative Eu anomalies, except for some samples of the N-MORB type from ODP sites. It means that Eu anomalies were derived from the uptake and removal of Eu2+ by feldspar fractionation during magma differentiation10,11,12,13,14,37,38,39. If we assume that the Eu isotope fractionation in the mafic volcanic rocks in this study was produced solely by feldspar crystallization, there should be little variation in the Eu isotope ratio (yellow area in Fig. 3, within ± 0.05‰ of the δ153Eu value) because the magnitude of the Eu anomaly for most samples is close to 1 ([Eu]N/[Eu*]N = 0.9–1.1). However, Eu isotope ratios of some mafic volcanic rocks in this work clearly show that Eu isotope fractionation may have occurred not only by feldspar crystallization but also other mechanisms. In particular, Fig. 3 enables us to suppose two possible mechanisms in Eu isotope fractionation with respect to the direction of the Eu anomaly. The variation in the δ153Eu value shown by the blue line area in Fig. 3 suggests a correlation with the magnitude of the Eu anomaly. Because Eu anomalies in igneous rocks were produced by plagioclase fractionation2a correlation between the Eu anomaly ([Eu]N/[Eu*]N) and Eu isotope fractionation (δ153Eu) can be interpreted that the Eu isotope fractionation shown in the blue line area might be produced by feldspar crystallization during magma differentiation4. Other notable characteristics are observed in Ulleung Island samples (the slightly reddish area in Fig. 3). These Ulleung Island mafic volcanic rocks are enriched in lighter Eu isotopes (151Eu), i.e., negative values of δ153Eu despite positive Eu anomalies, indicating that the Eu isotope fractionation is not product of feldspar crystallization. These Ulleung Island mafic volcanic rocks also have high LOI value (see Figs. 1b and 4a). Therefore, if the Eu isotope fractionation of the slightly reddish area in Fig. 3 is not a product by feldspar crystallization, we can infer that the lighter Eu isotope (151Eu) is enriched due to hydrothermal alteration, resulting in Eu isotope fractionation (Figs. 3 and 4a) because most samples showing large negative values of δ153Eu have high LOI concentrations, and the LOI value commonly represent the degree of hydrothermal alteration28. However, there remains a question. Some volcanic rocks with relatively high LOI contents do not show δ153Eu isotope fractionation. Hydrothermal alteration may cause Eu isotope anomalies, but not all kinds of alterations lead to Eu isotope anomalies. How can this phenomenon be explained? We observed that these volcanic samples with negative δ153Eu values all exhibited features of carbonate alteration (e.g., the presence of carbonatitic minerals and globules in Fig. 2). Thus, it is speculated that specific hydrothermal alteration processes might cause δ153Eu isotope anomalies. Among which the hydrothermal alteration of carbonate melt/fluid could be an important reason for the Eu isotope anomalies.

Comparison of europium isotopic signatures for the magnitude of Eu anomaly ([Eu]N/[Eu*]N). The blue line represents a correlation between the degree of δ153Eu and the magnitude of the Eu anomaly. The blue line was plotted including the Eu isotope ratio of rhyolite reported by Lee et al.4. The yellow band indicates the mean repeatability of Eu isotope ratio of NIST3117a Eu standard reagent within error range of ± 0.05‰ (2SD) during 2018–2024 (see Supplementary Table S3 and Fig. S7). Note the values of δ153Eu and positive Eu anomalies ([Eu]N/[Eu*]N > 1) from Ulleung Island mafic volcanic rocks. ([Eu]N/[Eu*]N = normalized values of Eu in the sample/interpolated value between the normalized value of Sm and Gd, i.e., [Eu]N. The REE concentration was normalized by the REE concentration of C-chondrite40. The147Sm-149Sm isotope pair in this work was used to perform bracketed mass bias correction (C-SSBIN) for determining and comparing Eu isotopic ratio (δ153Eu) in various kinds of geological materials7.

Among REEs, only Eu is present in the divalent state in most hydrothermal solutions at temperatures < 300℃41. It means that Eu anomalies can also arise from reducing the activity of Eu3+ relative to the other REE3+ isotopes, with records of fO210. Thus, redox changes resulting from hydrothermal reactions are likely to lead to the positive Eu anomalies. A case study of Eu anomalies in banded iron formations (BIFs) revealed that hydrothermal input was an important source of REEs to the global ocean, and that hydrothermal reactions likely generated positive Eu anomalies42,43. Because Fe3+ can easily oxidize Eu2+, the Eu2+ content should decrease with increasing Fe3+ content42.

Europium isotopic signatures of the mafic volcanic rocks. variation diagram of δ153Eu versus (a) LOI; (b) Fe2O3,;(c) TiO2 in mafic volcanic rocks. (d) diagram of Na2O + K2O versus 100 (%) × K2O/(Na2O + K2O)44 for subdivision of the alkali series into K and Na subseries. A: Na-altered rocks, B: igneous spectrum, C: K-altered rocks. The oxide contents were normalized to 100% without volatiles. The yellow area indicates no Eu isotope fractionation within the error, and slightly reddish area indicates large variation of Eu isotope ratio.

Most subalkaline mafic volcanic rocks with high Fe2O3, TiO2 and low LOI concentrations exhibit weak or almost no Eu isotope fractionation (Fig. 4a and c). In contrast, most of the alkaline mafic volcanic rocks with weak positive anomalies ([Eu]N/[Eu*]N : 1.05–1.14, Fig. 3), high LOI values (Fig. 4a) and relatively low Fe2O3 concentrations are characterized by large negative values of δ153Eu (from − 0.65‰ to −0.1‰, that is 151Eu enrichment, Fig. 4a and b). In addition, all volcanic samples in this work belong to the igneous spectrum or are classified as K-altered series and do not show geochemical features associated with Na-alteration (Fig. 4d). The effect of the variation in the K2O concentration might be stronger than that of the variation in the Na2O concentration on the Eu isotope fractionation during hydrothermal reactions (Fig. 4c and d).

In Fig. 4b, Fe2O3 contents of the Ulleung Island and some western Pacific mafic volcanic rocks with relatively large Eu isotope fractionation are lower than those of Jeju and Baekdusan mafic volcanic rocks as well as GRM. However, TiO2 contents of the Ulleung Island and some western Pacific mafic volcanic rocks are higher than those of Jeju and Baekdusan mafic volcanic rocks including GRM (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, their K2O/(Na2O + K2O) ratios are higher than those of Jeju Island and Baekdusan mafic volcanic rocks (Fig. 4d). The presence of Fe oxides and Fe-rich calcites in the Ulleung Island mafic volcanic rocks25 is good evidence of the calcitization of mafic minerals. It suggests that the decrease in total iron with increase of ferric oxide (Fe3+) and an increase of potash (K2O, Fig. 4d) might also be attributed to hydrothermal alteration of mafic volcanic rocks44. It is known that the heavier Eu isotope (153Eu) is preferentially fractionated into the Eu2+ solution phase during ion-exchange chromatography, forming part of the Eu2+/Eu3+ electron exchange system, indicating that the lighter Eu isotope (151Eu) seems to prefer an oxidized environment45. Therefore, under the presence of many Fe-rich ankerites in the Ulleung volcanic rocks (Fig. 2c and d), Figs. 4a–d suggest that hydrothermal solutions can cause Eu positive anomalies in solid rock composition and enrichment of lighter Eu isotope.

Conclusion

Considering that most mafic volcanic of Ulleung Island in this study contain carbonatitic xenocrysts (Fig. 2) and exhibit high LOI values (Fig. 1b), hydrothermal reactions is likely responsible for both the positive Eu anomalies and the significant enrichment of lighter Eu isotope (151Eu) of the Ulleung Island mafic volcanic rocks. Therefore, our results clearly demonstrate that Eu isotope fractionation can be modified not only magma differentiation but also by secondary effect such as hydrothermal alteration. Our data also suggest that further research on the differences in Eu isotope fractionation will provide important geochemical insights for understanding various kinds of geological and geochemical processes in the Earth system.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Lee, S-G. & Tanaka, T. Eu isotope fractionation in highly fractionated igneous rocks with large Eu negative anomaly. Geochem. J. 55/6, e9–e17 (2021).

Schauble, E. A. Nuclear volume isotope fractionation of europium and other lanthanide elements. Geochem. J. 57/4, 118–133 (2023).

Hu, J. Y. et al. Equilibrium fractionation of REE isotopes in nature: insights from NRIXS and DFT + U studies of Eu and dy phonon density of States. Geochim. Comochim Acta. 348, 323–339 (2023).

Lee, S-G., Tanaka, T. & Lee, M. J. Geochemical implication of Eu isotopic ratio in anorthosite: new evidence of Eu isotope fractionation during feldspar crystallization. Geosci. J. 27/3, 271–284 (2023).

Lee, S-G. & Tanaka, T. Determination of europium isotopic ratio by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry using a Sm internal standard. Spectrochim Acta Part. B. 156, 42–50 (2019).

Nicol, L., Garcon, M., Boyet, M. & Gannon, A. High-precision measurement of europium isotopic composition of geological reference materials by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (MC-ICP-MS). J. Anal. Spectrom. 38, 1261–1274 (2023).

Lee, S-G. Optimization of separation and MC-ICP-MS methods for determining Eu isotopic ratio in Si- and Ba-rich fractionated igneous rocks and other natural materials. Spectrochim Acta Part. B. 218, 106991 (2024).

Masuda, A. Simple regularity in the variation of relative abundances of rare Earth elements. J. Earth Sci. Nagoya Univ. 5, 125–134 (1957).

Coryell, C. D., Chase, J. W. & Winchesteb, J. W. A procedure for geochemical interpretation of terrestrial rare Earth abundance patterns. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 68, 559–566 (1962).

Burnham, A. D. et al. W. The oxidation state of europium in silicate melts as a function of oxygen fugacity, composition and temperature. Chem. Geol. 411, 248–259 (2015).

Weill, D. F. & Drake, M. J. Europium anomaly in plagioclase feldspar: experimental results and semiquantitative model. Science 180, 1059–1060 (1973).

Fowler, A. D. & Doig, R. The significance of europium anomalies in the REE spectra of granites and pegmatites, Mont laurier, Quebec. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 47, 1131–1137 (1983).

Shearer, C. K. & Papike, J. J. Is plagioclase removal responsible for the negative Eu anomaly in the source regions of mare basalts? Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 53, 3331–3336 (1989).

Möller, P. & Muecke, G. K. Significance of europium anomalies in silicate melts and crystal-melt equilibria: a re-evaluation. Contr Min. Pet. 87, 242–250 (1984).

Telus, M. et al. Iron, zinc, magnesium and uranium isotopic fractionation during continental crust differentiation: the Tale from migmatites, granitoids, and pegmatites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 97, 247–265 (2012).

Dauphas, N. et al. Magma redox and structural controls on iron isotope variations in earth’s mantle and crust. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 398, 127–140 (2014).

Millet, M-A. et al. Titanium stable isotope investigation of magmatic processes on the Earth and Moon. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 449, 197–205 (2016).

Prytulak, J. et al. Stable vanadium isotopes as a redox proxy in magmatic systems. Geochem. Persp Lett. 3, 75–84 (2017).

Inglis, E. C. et al. Isotopic fractionation of zirconium during magmatic differentiation and stable isotopic composition of the silicate Earth. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 250, 311–323 (2019).

Ibañez-Mejia, M. & Tissot, F. L. H. Extreme Zr stable isotope fractionation during magmatic fractional crystallization. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax8648 (2019).

Rossman, K. J. R. & Taylor, P. D. F. Isotopic compositions of the elements. Pure Appl. Chem. 70, 217–236 (1998).

Belli, P. et al. Search for α decay of natural europium. Nucl. Phys. A. 789, 15–19 (2007).

Bigeleisen, J. Temperature dependence of the isotope chemistry of the heavy elements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93, 9393–9396 (1996).

Lee, S-G., Asahara, Y. & Kim, G. Determination of REE abundances and Eu isotope ratio in GSJ and NIST feldspar reference standards (JF-1, JF-2, SRM 70a, 70b and SRM 99a) using ICP-QMS and MC-ICP-MS. EarthArxiv https://doi.org/10.31223/X57BID (2025).

Chen, S. S. et al. Carbon flux and alkaline volcanism: evidence from carbonatite-like carbonate minerals in trachytes, Ulleung island, South Korea. Am. Min. 107, 1717–1735 (2022).

Zhang, G-L., Chen, L-H., Jackson, M. G. & Hoffmann, A. W. Evolution of carbonated melt to alkali basalt in the South China sea. Nat. Geosci. 10, 229–235 (2017).

Dasgupta, R., Hirschmann, M. M. & Stalker, K. Immiscible transition from carbonate-rich to silicate-rich melts in the 3 GPa melting interval of eclogite CO2 and genesis of silica-undersaturated ocean Island lavas. J. Petrol. 47, 647–671 (2006).

Pandarinath, K. et al. Torres-Hernández J. R. Geochemical signature of hydrothermal alteration in surface rocks of cerritos Colorados geothermal field of Mexico. Geochemistry https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemer.2024.126200 (2024).

Lee, S. G., Kim, T., Tanaka, T., Lee, S. R. & Lee, J. I. Effect on the measurement of trace element by pressure bomb and conventional teflon vial methods in the digestion technique. J. Petrol. Soc. Korea. 25, 1–13 (2016). (in Korean with English abstract).

Chen, S. S. et al. Geochemical and seismic tomography constraints of two-layer magma chambers beneath the bimodal volcanism: A case study of late cenozoic volcanic rocks from Ulleung Island and mt. Changbai (Paektu). Chem. Geol. 581, 120386 (2021).

Lee, S. R. Physical conditions for basaltic volcanism beneath the Jeju volcanic field and the geodynamic implications. Geosci. J. 28, 789–795 (2024).

Chen, S. S., Liu, J. & Lee, S-G. Mineral and geochemical characteristics for Jurassic volcanic rocks from ODP Site 801 C in the Pigafetta Basin, Western Pacific Ocean: Implications for magmatic evolution at the oldest fast-spreading ridge. J Vol Geother Res 383, 112–127 (2019).

Choi, H-O. et al. Petrogenesis and mantle source characteristics of the late cenozoic Baekdusan (Changbaishan) basalts, North China craton. Gond Res. 78, 156–127 (2020).

Le Maritre, R. W. et al. B. A Classification of Igneous Rocks and Glossary of Terms (Blackwell, 1989).

Irvine, T. N. & Baragar, W. R. A. A guide to the chemical classification of the common volcanic rocks. Can. J. Earth Sci. 8, 525–548 (1971).

Wu, H. et al. A chromatographic approach for High-Precision Eu isotope analysis. Anal. Chem. 96, 15102–15107 (2024).

Niu, Y. & O’Hara, M. J. MORB mantle hosts the missing Eu (Sr, nb, Ta and Ti) in the continental crust: new perspectives on crustal growth, crust-mantle differentiation and chemical structure of oceanic upper mantle. Lithos. 112, 1–17 (2009).

Jenner, F. E. & O’Neill, H. St. C. Analysis of 60 elements in 616 ocean floor basaltic glasses. Geochem. Geophy Geosys. 13, Q03003 (2012).

O’Neill, H. St. C. The smoothness and shapes of Chondrite-normalized rare Earth element patterns in basalts. J. Pet. 57, 1463–1508 (2016).

McDonough, W. F. & Sun, S-S. The composition of the Earth. Chem. Geol. 120, 223–253 (1995).

Wood, S. A. The aqueous geochemistry of the rare-earth elements and yttrium 2. Theoretical predictions of speciation in hydrothermal solutions to 350℃ at saturation water vapor pressure. Chem. Geol. 88, 99–125 (1990).

Danielson, A., Möller, P. & Dulski, P. The europium anomalies in banded iron formations and the thermal history of the oceanic crust. Chem. Geol. 97, 89–100 (1992).

Kato, Y. et al. Rare Earth element variations in mid-Archean banded iron formations: implications for the chemistry of ocean and continent and plate tectonics. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 62, 3475–3497 (1998).

Schwarttz, G. M. Hydrothermal alteration of igneous rocks. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 50, 181–238 (1939).

Ismail, I. M., Nomura, M. & Fujii, Y. Isotope effects of europium in ligand exchange system and electron exchange system using ion-exchange displacement chromatography. J Chromato A. 808, 185–191 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00347048) and the Principal research Fund of the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (GP2025-029, GP2025-035) to S-G.L. This work was also partly supported by grants from Yunnan Key Laboratory of Earth System Science (ESS2024004) to S.S.C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S-G.L. designed this project and performed all experimental procedures, and wrote the manuscript. S.S.C. contributed to writing and interpretation of the result, including the preparation of samples of ODP sites. T.J.L., H.K., S.R.L., S.H. C., U.S.A., Y-S.L. contributed sampling and scientific discussion.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Online content

The methods and additional supplementary materials are available in the online version of the paper; references unique to these sections appear only in the online paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, SG., Chen, S., Lee, T.J. et al. Eu isotope fractionation and hydrothermal alteration. Sci Rep 15, 28746 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14613-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14613-9