Abstract

COVID-19 can trigger new cardiovascular events, including hypertension, in the acute setting. However, few studies have reported sustained new-onset hypertension post-infection. Moreover, these studies have a small sample size, inadequate controls, and a short (< 1 year) follow-up time. This retrospective cohort study of 64,000 COVID-19 patients) from the Stony Brook Health System assessed the incidence and risk factors for new-onset hypertension after COVID-19. Contemporary COVID-negative controls were obtained and propensity-matched for age, race, sex, ethnicity, and major comorbidities before analyzing outcomes. The primary outcome was new-onset hypertension up to 3 years post-index date. About 9.93% of hospitalized patients and 4.66% of non-hospitalized patients developed new-onset hypertension after COVID-19. Hospitalized COVID-positive patients were more likely to develop hypertension compared to COVID-negative controls (Hazard Ratio [HR] = 1.57, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] [1.35–1.81]) and non-hospitalized COVID-positive controls (HR: 1.42, 95%CI [1.24–1.63]). Non-hospitalized COVID-positive patients were not more likely to develop hypertension than COVID-negative controls (HR: 1.05, 95%CI [0.98–1.13]). COVID-19 was one of the five greatest risk factors for developing hypertension. COVID-19 patients are at increased risk of developing hypertension beyond the acute phase of the disease compared to controls. Long-term follow-up, holistic workups, and vigilant blood pressure screening and/or monitoring for COVID-19 patients are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The long-term health consequences of COVID-19 have garnered significant attention as a multitude of persistent and systemic effects of the virus are uncovered, collectively referred to as post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC), or “long COVID1.” While much focus has been placed on respiratory and neurological sequelae, emerging evidence highlights the potential for COVID-19 to contribute to the development of long-term cardiovascular conditions, including hypertension. Hypertension, a leading global cause of morbidity and mortality, often develops insidiously but carries significant implications for cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure2.

Mechanistically, COVID-19 may cause hypertension by persistent systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and/or autonomic dysregulation. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection has been shown to directly impair endothelial function by down regulating angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors, promoting vasoconstriction, oxidative stress, and pro-inflammatory states. In addition, the virus may exacerbate pre-existing subclinical cardiovascular conditions, potentially unmasking hypertension in individuals with predisposing risk factors. Chronic dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), a pathway critical to blood pressure regulation, may also play a central role in the long-term sequelae of COVID-19.

The association between COVID-19 and new-onset hypertension is poorly understood, as only a handful of studies have been conducted3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Moreover, many of these studies have a small sample size, lack COVID-negative controls, do not adequately distinguish between new-onset and persistent hypertension, or do not provide an in-depth analysis of risk factors. Most studies are limited to at most a 6-month follow-up9. As such, the long-term (> 1 year) effects of SARS-CoV-2 on developing hypertension have yet to be adequately analyzed.

This study of over 1.7 million patients from January 2020 to October 2024 investigates the long-term association between COVID-19 and new-onset hypertension at 3-year follow-up to capture the sustained effects of SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, we stratified the COVID-positive patients into hospitalized and non-hospitalized cohorts to compare the impact of COVID-19 severity on the development of new-onset hypertension. We also identified the major risk factors for developing new-onset hypertension. Understanding the long-term risk of hypertension in patients with COVID-19 is essential for guiding post-COVID care, including targeted monitoring and early intervention strategies, to mitigate the cardiovascular burden associated with the pandemic.

Results

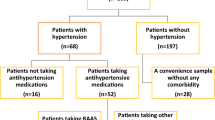

Figure 1 shows the cohort selection flowchart for this study. From January 2020 to October 2024, 64,250 patients tested positive for COVID-19, and 225,980 patients tested negative for COVID-19 and never had a positive test thereafter. There were 172,660 (76.40%) COVID-negative patients and 42,900 (66.77%) COVID-positive patients who had no past medical history of hypertension. The COVID-positive cohort was divided into 5,500 (12.94%) hospitalized patients and 37,350 (87.06%) non-hospitalized patients. Before matching, the number of patients with new-onset hypertension at 3 years follow-up was 410 (9.93%), 1,650 (4.66%), and 12,030 (6.94%) for the hospitalized COVID-positive, non-hospitalized COVID-positive, and COVID-negative cohorts, respectively.

Table 1 shows the baseline patient demographics for the three cohorts. Hospitalized COVID-positive patients were more likely to be older (50.4 ± 23.7 vs. 35.9 ± 23.8, p < 0.001) white (63% vs. 56%, p < 0.001), male (54% vs. 45%, p < 0.001) and had a higher prevalence of CAD, CHF, CKD, diabetes, obesity, COPD, and tobacco use (all p < 0.001), but not asthma (p = 0.68), compared to COVID-negative patients.

Hospitalized COVID-positive patients were more likely to be older (50.4 ± 23.7 vs. 36.5 ± 22.4, p < 0.001) white (63% vs. 52%, p < 0.001), male (54% vs. 42%, p < 0.001) and had higher prevalence of CAD, CHF, CKD, diabetes, COPD, and tobacco use (all p < 0.001), but lower prevalence of asthma and obesity (p < 0.001), compared to non-hospitalized COVID-positive patients.

Non-hospitalized COVID-positive patients were more likely to be older (36.5 ± 22.4 vs. 35.9 ± 23.8, p < 0.001), less likely to be white (52% vs. 56%, p < 0.001), less likely to be male (42% vs. 45%, p < 0.001) and had higher prevalence of CAD, CHF, CKD, diabetes, obesity, COPD, asthma, and tobacco use (all p < 0.001) compared to COVID-negative patients.

Figure 2 shows the 3-year cumulative incidence curve for new-onset hypertension. At 3-year follow-up, hospitalized COVID-positive patients were at greater risk of developing new-onset hypertension compared to COVID-negative controls (HR = 1.57, 95%CI [1.35–1.81]). Non-hospitalized COVID-positive patients were not more likely to develop hypertension than COVID-negative controls (HR: 1.05 [0.98–1.13]). Hospitalized COVID-positive patients were also at greater risk of developing new-onset hypertension compared to non-hospitalized COVID-positive patients (HR: 1.42, 95%CI [1.24–1.63]).

For the non-hospitalized COVID-positive cohort, the results were then separated into two distinct time periods: 1-month to 1.5-years after COVID, and 1.5-years to three years afterCOVID. Non-hospitalized patients were not more likely to develop hypertension in the 1-month to 1.5-year time period (HR: 1.00, 95% CI [0.92–1.10]), but they were more likely in the 1.5-3-year time period (HR: 1.14, 95% CI [1.01–1.28]) compared to COVID-negative controls.

Table 2 shows the multivariate odds ratios for patients with new-onset hypertension at 3-yearfollow-up. COVID-19 patients were more likely to develop new-onset hypertension compared to COVID-19 negative controls (OR = 1.76 [1.62–1.92]). Confounders included male (OR = 1.22 [1.15–2.30]), older than 50 years old (OR = 2.39 [2.24–2.55]), Hispanic (OR = 1.12 [1.01–1.24]) and those with greater comorbidities (ORs ranging from 1.12 to 3.07).

Discussion

This study evaluated the risk of new-onset hypertension up to 3 years post SARS-CoV-2 infection in 1.7 million patients in the Stony Brook Medicine Healthcare System. This is the first study to report these findings at up to 3-years post-infection follow-up. The main findings were: (1) 9.93% of hospitalized patients and 4.66% of non-hospitalized patients developed new-onset hypertension after COVID-19 compared to 6.94% in COVID-19 negative controls, (2) Hospitalized COVID-positive patients were more likely to develop new-onset hypertension compared to propensity-matched COVID-negative patients (HR = 1.57) and non-hospitalized COVID-positive patients (HR: 1.42). (3) COVID-19 was one of the five greatest risk factors for developing new-onset hypertension, along with obesity, age > 50, tobacco use, and insomnia.

A few studies have investigated new-onset hypertension after COVID-19. Zhang et al. analyzed 45,398 COVID-19 patients in the Montefiore Health System in the Bronx. They reported the incidence of new-onset hypertension to be 20.6% and 10.85% in hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients, respectively, at 6-months follow-up9. Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 were 2.23 ([95% CI, 1.48–3.54]; P < 0.001) times and nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19 were 1.52 ([95% CI, 1.22–1.90]; P < 0.01) times more likely to develop new-onset hypertension than influenza counterparts with adjustment of confounders. Notably, the Montefiore cohort was predominantly Black and/or Hispanic patients and had a high prevalence of pre-existing comorbidities. Our cohort was predominantly White, comparatively younger, and had a lower prevalence of comorbidities. Despite these differences, we found similar risk factors for developing new-onset hypertension, including age, male sex, and major preexisting comorbidities.

In a study of 168 COVID-19 patients, Akpek et al. found the incidence of new-onset hypertension to be 12% at 30-day follow-up3. Delacic et al. report an incidence of 16% in 199 COVID-19 patients at 3-month follow-up6. Vyas et al. report an incidence of 32.3% in 248 COVID-19 patients at 1-year follow-up8. In addition to small sample sizes, lack of risk factor analysis, and a relatively short follow-up period, these studies do not have COVID-negative controls nor statistical analyses for comparison. Azama et al. conducted a larger study of 5,355 COVID-19 patients and found an incidence of 17% at 1-year follow-up. This study was conducted at a cardiology clinic, which likely had higher incidence. This study also did not use COVID-negative controls for comparison. Nonetheless, they identified risk factors associated with elevated blood pressure including increased age and comorbidities, which is consistent with our study. Lastly, Cohen et al. found COVID-19 patients ≥ 65 years old to be more likely to experience hypertension compared to propensity-matched COVID-negative patients (risk difference 4.43, 2.27–6.37) at 3-month follow-up5. They did not report the percent incidence. Generally, the patients in the aforementioned studies were older and/or had a higher prevalence of comorbidities than our cohorts, which may explain the elevated incidence rate relative to our study. Differences in experimental design, patient profiles (i.e., age, race/ethnicity, and pre-existing comorbidities), comparison group, regional and temporal differences in the severity of COVID-19 cases, duration of study (observation time), and other factors could all have contributed to differences in findings. Studies of populations from more affected regions and studies of the first few months of the pandemic likely have a higher outcome incidence.

Vaccination status may be an important protective factor against new onset hypertension. The COVID-19 vaccine has been shown to decrease the risk of repeat infection, and both acute and long-COVID cardiovascular complications10,11,12,13. In this study, while individual vaccination data was not available, Suffolk County reported on May 2022 that 95% of adults received at least one vaccination dose and 87% of adults were fully vaccinated14. In contrast, an estimated 34% of people in the Bronx were vaccinated as of August 202215, which may explain, in part, the difference in incidence between the two cohorts. It should be noted that the effect of individual vaccination status is particularly difficult to assess with regards to the outcomes of this study. Vaccine status is not reliably recorded across different health care systems, and administration can vary based on age, comorbidities, and vaccine type (single vs. multiple shots).

The magnitude and the rate of cumulative incidence of new HTN in the hospitalized COVID-19 cohort were markedly higher than those of COVID-negative controls in the first-year post-infection. By contrast, the magnitude and the rate of cumulative incidence of new HTN in the nonhospitalized COVID-19 cohort were similar to the COVID-negative cohort. These observations suggest that non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients experience an initial indolent phase followed by a late onset of hypertension. Indeed, whereas a more severe course of COVID-19 may lead to a relatively immediate diagnosis of hypertension, a less severe course of COVID-19 may simply accelerate the progression of hypertension in patients who may already be at risk of developing it.

Not surprisingly, patients with age over 50, male sex, and major comorbidities (CAD, HF, CKD, DM, obesity, asthma, COPD, tobacco use) were found to be at higher risk of new-onset hypertension. Age is a well-known risk factor for developing hypertension and has also been shown to be an independent predictor of COVID-19 severity16,17. Sex differences in developing hypertension have been hypothesized to occur, in part, due to differences in the influence of sex hormones on activating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS)18. Likewise, this differential activation of the RAAS in males, coupled with the dysregulation of the RAAS by SARS-CoV-2, may explain why males have a greater predisposition for increased COVID severity19. This increased severity may lead to greater rates of hypertension in males post-COVID. Obesity was the greatest risk factor for the development of new-onset hypertension, which is unsurprising considering obesity is a known cause of hypertension20is linked to worse COVID-19 outcomes by several studies21,22,23 and is associated with every other chronic comorbidity found to be a risk factor. Despite black race having a well-known association with developing hypertension24we did not find black race to be a significant risk factor for developing hypertension, which may be due to the low proportion of black patients in our cohort. Moreover, the high socioeconomic status of the area around Stony Brook Hospital (Suffolk County has the third highest median income, $141,671, in New York State) may contribute to lower rates of hypertension in our cohort, regardless of race25,26.

COVID-19 status was the fifth-greatest risk factor for new-onset hypertension, greater than even well-established risk factors such as CKD, and diabetes27,28. This may be because very few patients in our study population had these pre-existing comorbidities, thereby leading to underestimation of their association with developing hypertension. Indeed, the absence of comorbidities in younger and healthier patients may make COVID-19 a greater risk factor for new-onset hypertension in this population.

Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic may also play an important role in the development of new-onset hypertension. Prior studies show increased levels of anxiety, mood, substance abuse, and sleep disorders among patients with COVID-19 compared to contemporary controls29. These conditions have been associated with an increase in the subsequent diagnosis of new-onset hypertension30. Likewise, we found anxiety, depression, insomnia, and substance use disorders to be independent risk factors for developing hypertension. Moreover, certain antidepressant and antipsychotic medications are linked to an increased risk of hypertension. Dedicated studies analyzing the relationship between COVID-19, psychiatric conditions, psychiatric medications, and new-onset hypertension are necessary.

In addition to the effects of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, the social and economic stress imparted by the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown may also contribute to the development of hypertension. The increase in hypertension diagnoses and mean systolic/diastolic blood pressures31,32 after the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be explained entirely by those infected by SARS-CoV-233. Instead, the increase in mental health and financial stress, weight gain, decrease in physical activity, and limited access to healthcare34,35,36,37,38 likely also play a significant role in the development of hypertension.

Multiple COVID-19 infections may be another important risk factor for developing new onset hypertension. A large national study using data from the US Department of Veteran Affairs found increased risk of death, rehospitalization, and multi-organ system sequalae in patients with reinfection from COVID-19 compared to those without reinfection at 6-month follow-up39. Notably, patients with reinfection were more likely to suffer from cardiovascular disorders (HR = 3.02, 95% CI = 2.80–3.26) at follow-up. Moreover, other studies have shown an increased risk of developing long-COVID in patients with multiple COVID-19 infections compared to single-infection patients40,41. As such, it reasons to believe that those with multiple COVID-19 infections will likely have a greater degree of cardiovascular and multiorgan system insult, thereby increasing the risk of developing hypertension.

Our cohorts are predominantly White, relatively young, with few comorbidities, and a high median income, which may reduce the generalizability of our results. However, despite our homogenous cohorts, the risk factors identified in this study, with the exception of race, are largely consistent with studies conducted in more diverse and lower income populations9. Moreover, despite our study showing a significant increase in the incidence of new onset hypertension after COVID-19, this is still likely an underestimation especially in more diverse and lower income populations9. Indeed, the burden that new onset hypertension may impose on the healthcare system is likely even greater than our study predicts, particularly in underserved populations where patients may have more risk factors and/or reduced access to adequate healthcare.

The exact mechanism by which COVID-19 may cause new-onset hypertension is not known, though several mechanisms have been proposed. One mechanism is via disruption of the RAAS system by the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to the ACE2 receptor, thus, preventing the conversion of angiotensin II (vasoconstrictor) to angiotensin [1–7] (vasodilator). This imbalance results in excess angiotensin II and leads to sustained vasoconstriction and increased blood pressure. Another mechanism is the “cytokine storm” whereby COVID-19 triggers a systemic inflammatory response resulting in irreversible damage to the vascular endothelium by cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-ɑ. This permanent damage to the blood vessels impairs their ability to relax, resulting in hypertension. Lastly, it is possible that during the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection, sympathetic activation, typical of a viral illness, may persist beyond the acute phase of infection, or may even have some degree of delayed-onset. Despite the resolution of COVID-19 symptoms, sympathetic tone may remain persistently elevated, resulting in new-onset hypertension in the post-acute setting. Regardless of its exact mechanism, we found COVID-19 to be an independent risk factor for developing new-onset hypertension, even after matching for other major comorbidities.

Diagnosing post-COVID hypertension may pose a unique challenge to healthcare providers. The onset of hypertension can occur well beyond the acute COVID period and in relatively young and healthy patients, making it difficult to determine an etiology. We urge healthcare providers not to dismiss new-onset hypertension in COVID-19 patients as white coat hypertension, and to instead conduct a holistic workup with a particular emphasis on patients’ mental and psychiatric health as well as new-onset comorbidities. This study also highlights the need for close long-term follow-up and blood pressure monitoring in COVID-19 patients. Implementing post-COVID blood pressure screening programs may be beneficial, especially in populations/communities with predisposing risk factors.

There are a few limitations to this study. First, this is a single center study, although there were 1.7 million patients within the Stony Brook Healthcare System. Our cohort was predominantly White, relatively young, with low rate of comorbidities, and a high median income which may reduce the generalizability of our results. Furthermore, our analysis was limited to patients who were tested for COVID-19 exclusively within the Stony Brook Healthcare System and returned. Consequently, it does not encompass patients who tested positive at other healthcare systems, with at-home COVID-19 test kits, or experienced mild symptoms and were not tested. We did not study outcomes concerning COVID-19 vaccination status because many patients may have received the vaccine elsewhere. Moreover, there may be patients in either cohort with white coat hypertension or, conversely, those with masked hypertension. Hospitalized patients may be screened sooner and more frequently after COVID-19, possibly contributing to an earlier and higher incidence of outcomes. As is the case with any retrospective cohort study, the outcomes of this study may be affected by confounders that were not accounted for.

Analysis with respect to hypertension severity is important. However, our study is limited to the use of ICD 10 codes available on the TriNetX platform which does not include grades of hypertension, isolated systolic hypertension, isolated diastolic hypertension, or masked hypertension. We explored the possibility of using blood pressure readings to define the severity of hypertension, but this proved to have many confounders (concurrent use of blood pressure medications, blood pressure readings during hospitalizations, white coat hypertension) making the data difficult to interpret.

In conclusion, this study reports an increased incidence of new-onset hypertension in both hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients compared to propensity-matched COVID-negative contemporary controls up to 3 years post-index date. COVID-19 was found to be a major independent risk factor for the development of new-onset hypertension, comparable to other known risk factors for hypertension. These findings highlight the need for close long-term follow-up, holistic workups, and vigilant blood pressure screening and/or monitoring for at-risk COVID-19 patients.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study was conducted on the TriNetX42 research platform using de-identified Electronic Medical Record data from over 1.7 million patients from January 2020 to October 2024 in the Stony Brook University Healthcare Network. TriNetX is a global web-based platform that allows researchers to identify and characterize patient cohorts and analyze outcomes. Broadly, the data includes demographics, diagnoses (based on International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification codes), procedures (based primarily on International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Procedure Coding System, Current Procedural Terminology, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, and Systemized Nomenclature of Medicine codes), medications (based on Veteran Affairs and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical codes), laboratory values (based on Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes or curated separately by TriNetX), and genomics data.

With one of the largest global COVID-19 datasets, multiple studies have used TriNetX to study the outcomes of COVID-1943,44,45. Details regarding the data extraction, transformation, and validation performed by TriNetX have been published46. Other external validation studies have also confirmed the reliability of TriNetX in analyzing large-scale data47.

Due to the study’s retrospective nature, the Stony Brook University Institutional Review Board waived the need to obtain informed consent. The data reviewed is a secondary analysis of existing data, does not involve intervention or interaction with human subjects, and is de-identified per the de-identification standard defined in Section § 164.514(a) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. The process of de-identifying data is attested to through a formal determination by a qualified expert as defined in Section § 164.514(b)(1) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. This formal determination by a qualified expert was updated in December 2020. All methods were conducted in accordance with TriNetX guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols received approval from Stony Brook University.

We queried the Stony Brook TriNetX database from January 2020 to October 2024 for patients with COVID-19 and without COVID-19 who did not have a pre-existing diagnosis of hypertension (assessed on October 10, 2024). Details regarding the search query, identification codes, and inclusion/exclusion criteria can be found in the supplemental materials (Supplemental Tables 1 and Supplemental Table 2). Briefly, COVID-19 was defined as a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. COVID-negative patients were defined as those with a negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR test who never had a subsequent positive SARS-COV-2 PCR test. Essential hypertension was defined using the ICD code I10. The COVID-positive cohort was then subdivided into those who were hospitalized during the time of their COVID infection and those who were not. These cohorts were then 1:1 propensity-matched with the COVID-negative cohort before analyzing outcomes.

The follow-up period for this study was between 1 month and 3 years after COVID-19. The primary outcome was a new diagnosis of hypertension based on the ICD-10 code. Cumulative incidence was obtained by assessing the number of outcomes monthly. All outcomes in this study were categorical.

Statistical analyses were performed directly on the TriNetX platform, which, for this study, used R 4.0.2 software. All variables in this study were categorical and expressed a frequency or percentage of the total cohort, except age, which was expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were 1:1 propensity matched with controls for age, race, sex, ethnicity, and comorbidities including congestive heart failure (CHF), coronary artery disease (CAD), diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obesity, and tobacco use before analyzing outcomes. Propensity score—representing the probability of the experimental group—was estimated for each subject using logistic regression based on the observed covariates. Individuals in the experimental group were 1:1 matched with those in the control group who had similar propensity scores, creating comparable groups for outcome analysis. Matching was done between any two cohorts that were being directly compared. Hazard ratios (HR) and confidence intervals (CI) were generated by the TriNetX platform for all outcomes. Multivariate odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated using Microsoft Excel.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Davis, H. E., McCorkell, L., Vogel, J. M. & Topol, E. J. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2 (2023).

Psaty, B. M. et al. Association between blood pressure level and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and total mortality: the cardiovascular health study. Arch. Intern. Med. 161, 1183–1192. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.161.9.1183 (2001).

Akpek, M. Does COVID-19 cause hypertension?? Angiology 73, 682–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/00033197211053903 (2022).

Azami, P. et al. Evaluation of blood pressure variation in recovered COVID-19 patients at one-year follow-up: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 24, 240. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-024-03916-w (2024).

Cohen, K. et al. Risk of persistent and new clinical sequelae among adults aged 65 years and older during the post-acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: retrospective cohort study. Bmj 376, e068414. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-068414 (2022).

Delalić, Đ., Jug, J. & Prkačin, I. Arterial hypertension following & COVID-19: a retrospective study of patients in a central European Tertiary Care Center. Acta Clin. Croat. 61, 23–27. https://doi.org/10.20471/acc.2022.61.s1.03 (2022).

Mizrahi, B. et al. Long Covid outcomes at one year after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: nationwide cohort study. Bmj 380, e072529. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-072529 (2023).

Vyas, P. et al. Incidence and predictors of development of new onset hypertension post COVID-19 disease. Indian Heart J. 75, 347–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2023.06.002 (2023).

Zhang, V., Fisher, M., Hou, W., Zhang, L. & Duong, T. Q. Incidence of new-onset hypertension post-COVID-19: comparison with influenza. Hypertension 80, 2135–2148. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.123.21174 (2023).

Stein, C. et al. Past SARS-CoV-2 infection protection against re-infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 401, 833–842. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02465-5 (2023).

Tenforde, M. W. et al. Association between mRNA vaccination and COVID-19 hospitalization and disease severity. Jama 326, 2043–2054. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.19499 (2021).

Cezard, G. I. et al. Impact of vaccination on the association of COVID-19 with cardiovascular diseases: an opensafely cohort study. Nat. Commun. 15, 2173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46497-0 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Cardiovascular events following coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination in adults: a nationwide Swedish study. Eur. Heart J. 46, 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae639 (2025).

Suffolk County Department of Health Services. COVID-19 CASE UPDATE (2022).

CUNY School of Public Health. COVID-19 Survey (2022).

Buford, T. W. Hypertension and aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 26, 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2016.01.007 (2016).

Romero Starke, K. et al. The isolated effect of age on the risk of COVID-19 severe outcomes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health. 6 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006434 (2021).

Connelly, P. J., Currie, G. & Delles, C. Sex differences in the prevalence, outcomes and management of hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 24, 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-022-01183-8 (2022).

Monteonofrio, L., Florio, M. C., AlGhatrif, M., Lakatta, E. G. & Capogrossi, M. C. Aging- and gender-related modulation of RAAS: potential implications in COVID-19 disease. Vasc Biol. 3, R1–r14. https://doi.org/10.1530/vb-20-0014 (2021).

Hall, J. E., Carmo, da Silva, J. M., Wang, A. A., Hall, M. E. & Z. & Obesity-induced hypertension: interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ. Res. 116, 991–1006. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.116.305697 (2015).

Arulanandam, B., Beladi, H. & Chakrabarti, A. Obesity: COVID-19 mortality are correlated. Sci. Rep. 13, 5895. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33093-3 (2023).

Sawadogo, W., Tsegaye, M., Gizaw, A. & Adera, T. Overweight and obesity as risk factors for COVID-19-associated hospitalisations and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health. 5, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjnph-2021-000375 (2022).

Singh, R. et al. Association of obesity with COVID-19 severity and mortality: an updated systemic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 780872. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.780872 (2022).

Aggarwal, R. et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in the united states, 2013 to 2018. Hypertension 78, 1719–1726. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.121.17570 (2021).

Leng, B., Jin, Y., Li, G., Chen, L. & Jin, N. Socioeconomic status and hypertension: a meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 33, 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1097/hjh.0000000000000428 (2015).

HDPulse : An Ecosystem of Minority Health and Health Disparities Resources. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. https://hdpulse.nimhd.nih.gov.

Ku, E., Lee, B. J., Wei, J. & Weir, M. R. Hypertension in CKD: core curriculum 2019. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 74, 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.12.044 (2019).

Lago, R. M., Singh, P. P. & Nesto, R. W. Diabetes and hypertension. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 3, 667. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpendmet0638 (2007).

Wang, Y., Su, B., Xie, J., Garcia-Rizo, C. & Prieto-Alhambra, D. Long-term risk of psychiatric disorder and psychotropic prescription after SARS-CoV-2 infection among UK general population. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 1076–1087. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01853-4 (2024).

Stein, D. J. et al. Associations between mental disorders and subsequent onset of hypertension. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 36, 142–149 (2014).

Gotanda, H. et al. Changes in blood pressure outcomes among hypertensive individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A time series analysis in three US healthcare organizations. Hypertension 79, 2733–2742. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.122.19861 (2022).

Nolde, J. M. et al. Trends in blood pressure changes and hypertension prevalence in Australian adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich). 26, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.14761 (2024).

Trimarco, V. et al. Incidence of new-onset hypertension before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic: a 7-year longitudinal cohort study in a large population. BMC Med. 22, 127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03328-9 (2024).

Al Zaman, K. et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on weight change among adults in the UAE. Int. J. Gen. Med. 16, 1661–1670. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.S407934 (2023).

Argabright, S. T. et al. COVID-19-related financial strain and adolescent mental health. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 16, 100391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100391 (2022).

Khubchandani, J., Price, J. H., Sharma, S., Wiblishauser, M. J. & Webb, F. J. COVID-19 pandemic and weight gain in American adults: A nationwide population-based study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 16, 102392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2022.102392 (2022).

Pujolar, G., Oliver-Anglès, A., Vargas, I. & Vázquez, M. L. Changes in access to health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031749 (2022).

Rodrigues, M., Silva, R. & Franco, M. COVID-19: financial stress and well-being in families. J. Fam Issues. 44, 1254–1275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x211057009 (2023).

Bowe, B., Xie, Y. & Al-Aly, Z. Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Nat. Med. 28, 2398–2405. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02051-3 (2022).

Babalola, T. K. et al. SARS-COV-2 re-infection and incidence of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) among essential workers in new york: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 42, 100984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2024.100984 (2025).

Hadley, E. et al. Insights from an N3C RECOVER EHR-based cohort study characterizing SARS-CoV-2 reinfections and long COVID. Commun. Med. (Lond). 4, 129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-024-00539-2 (2024).

TriNetX, L. L. M. October. Stony Brook Healthcare Network. https://trinetx.com. (2024).

Harrison, S. L., Fazio-Eynullayeva, E., Lane, D. A., Underhill, P. & Lip, G. Y. H. Comorbidities associated with mortality in 31,461 adults with COVID-19 in the united states: A federated electronic medical record analysis. PLoS Med. 17, e1003321. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003321 (2020).

Jorge, A. et al. Temporal trends in severe COVID-19 outcomes in patients with rheumatic disease: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 3, e131–e137. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2665-9913(20)30422-7 (2021).

Wang, W., Wang, C. Y., Wang, S. I. & Wei, J. C. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in COVID-19 survivors among non-vaccinated population: A retrospective cohort study from the TriNetX US collaborative networks. EClinicalMedicine 53, 101619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101619 (2022).

Topaloglu, U. & Palchuk, M. B. Using a federated network of real-world data to optimize clinical trials operations. JCO Clin. Cancer Inf. 2, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1200/cci.17.00067 (2018).

Evans, L., London, J. W. & Palchuk, M. B. Assessing real-world medication data completeness. J. Biomed. Inf. 119, 103847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2021.103847 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MB contributed to the study conceptualization, study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript drafting and editing. JG, SB, TA, and RL contributed to data analysis, manuscript drafting and editing. TD contributed to study conceptualization, study design, manuscript drafting and editing, and supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics declaration

The TriNetX Network is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), a federal law protecting the confidentiality of health information. All data acquired from TriNetX was de-identified and displayed as an aggregate and/or average rather than an individual patient basis.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boparai, M.S., Gordon, J., Bajrami, S. et al. Incidence and risk factors of new-onset hypertension up to 3 years post SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Rep 15, 28728 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14617-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14617-5