Abstract

Hydrogen (\(\textrm{H}_2\)) is emerging as a key alternative to fossil fuels in the global energy transition. This study presents a comparative techno-economic analysis of \(\textrm{H}_2\) and natural gas (NG), focusing on safety hazards, energy output, \(\textrm{CO}_2\) emissions, and cost-effectiveness aspects. Our analysis showed that, compared to NG and other highly flammable gases like acetylene (\(\textrm{C}_2\,\textrm{H}_2\)) and propane (\(\textrm{C}_3\,\textrm{H}_8\)), \(\textrm{H}_2\) has a higher hazard potential due to factors such as its wide flammability range, low ignition energy, and high flame speed. In terms of energy output, 1 kg of NG produces 48.60 MJ, while conversion to liquefied natural gas (LNG), grey \(\textrm{H}_2\), and blue \(\textrm{H}_2\) reduces energy output to 45.96 MJ, 35.45 MJ, and 31.21 MJ, respectively. Similarly, while unconverted NG emits 2.72 kg of \(\textrm{CO}_2\) per kg, emissions increase to 3.12 kg for LNG and 3.32 kg for grey \(\textrm{H}_2\). However, blue \(\textrm{H}_2\) significantly reduces \(\textrm{CO}_2\) emissions to 1.05 kg per kg due to carbon capture and storage. From an economic perspective, producing 1 kg of NG yields a profit of $0.011. Converting NG to grey \(\textrm{H}_2\) is most profitable, yielding a net profit of $0.609 per kg of NG, while blue \(\textrm{H}_2\), despite higher production costs, remains viable with a profit of $0.390 per kg of NG. LNG conversion also shows profitability with $0.061 per kg of NG. This analysis highlights the trade-offs between energy efficiency, environmental impact, and economic viability, providing valuable insights for stakeholders formulating hydrogen and LNG implementation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, the global energy supply is primarily sourced from fossil fuels. In 2022, for instance, around 85% of this energy supply was derived from fossil fuels, as indicated in Fig. 1. However, despite their abundance, there is a growing need to reduce reliance on fossil fuels1. The extraction and processing of fossil fuels have significant adverse environmental effects, including water pollution from coal mine drainage and coal sludge2, wastewater from drilling and fracking operations3, oil and chemical spills4, and refinery effluents5. Additionally, during enhanced oil recovery (EOR) operations, chemicals such as surfactants and polymers are injected into subsurface formations. These chemicals can migrate from hydrocarbon reservoirs into adjacent groundwater and surface-water bodies, increasing the risk of aquatic contamination6. Furthermore, the continued use of fossil fuels has led to increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, such as \(\textrm{CO}_2\), which accelerate climate change7.

As the world searches for cleaner energy, renewable sources are continuously being pursued and developed. However, a complete and abrupt transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy is unfeasible. This is due to challenges associated with renewable energy, such as high initial costs, immature technology, intermittent supply, and energy conversion inefficiencies, to varying extents10,11. As a result, hydrogen and natural gas (methane) have emerged as critical components in this search due to their potential to offer significant reductions in carbon emissions, supporting the transition to a low-carbon energy future12,13.

Hydrogen can be used both as an energy carrier and fuel14. Hydrogen also has the potential to achieve zero or minimal \(\textrm{CO}_2\) emissions when produced using renewable energy sources, such as in the case of green hydrogen15. Alternatively, hydrogen can be derived from fossil fuels coupled with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, resulting also in low \(\textrm{CO}_2\) emissions. An example of this is blue hydrogen, which is produced from natural gas, using autothermal reforming (ATR) or steam methane reforming (SMR) with CCS implementation16. It is worth noting that hydrogen produced from natural gas without CCS implementation is referred to as grey hydrogen. The production of grey hydrogen is associated with relatively high \(\textrm{CO}_2\) emissions compared to blue and green hydrogen17.

Despite its advantages, hydrogen transport and storage pose significant safety risks stemming from its physicochemical properties, making it highly susceptible to leaks and accidental ignitions18. On the other hand, natural gas is a well-established energy source with extensive infrastructure already in place for its transport and storage19. Natural gas is considered cleaner than other fossil fuels, including coal and oil20. However, it still contributes to carbon emissions21, and it poses flammability risks during transport and storage22.

This study addresses a research gap involving the lack of a unified framework that systematically compares natural gas and its hydrogen derivatives across the critical domains of safety, energy efficiency, environmental impact, and economic profitability. The novelty of this study involves, first, a detailed fire and explosion hazard comparison using a binary pairwise scoring method across 14 distinct physicochemical factors. Second, it provides a techno-economic and environmental analysis where energy output, \(\textrm{CO}_2\) emissions, costs, and profits are all normalized per kilogram of natural gas feedstock, enabling a direct evaluation of various conversion pathways including LNG, grey hydrogen, and blue hydrogen. These assessments assist policymakers and industry professionals in evaluating the viability of hydrogen conversion technologies as sustainable and profitable investments. This allows stakeholders to precisely weigh the environmental gains against the economic and energetic costs.

Methodology overview

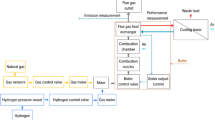

The methodology employed in this study is presented in Fig. 2, outlining two primary assessments conducted. In Assessment 1, a comparative analysis of fire and explosion hazards was performed. Selected gases were evaluated using a binary pairwise scoring method based on 14 physicochemical factors that determine hazard probability and consequence. The final hazard score for each gas was calculated by summing these individual scores. Assessment 2, on the other hand, involves techno-economic and environmental analyses of natural gas utilization pathways, with all metrics normalized. This assessment determines natural gas-to-fuel conversion ratios, calculates energy output, \(\textrm{CO}_2\) emissions, production costs, and net profit based on market prices, followed by a sensitivity analysis with ±20% cost/price variations to assess economic stability. Details of these assessments are presented in the following sections.

Comparative analysis of the hazards of hydrogen and natural gas

The use of hydrogen and natural gas (mainly methane) as fuels and industrial feedstocks necessitates their storage in large quantities, often in specialized tanks or containers to maintain safety and prevent leakage. However, large-scale storage introduces significant hazards due to the flammable and explosive nature of both gases23,24. Hydrogen, due to its small molecular size and high diffusivity, is prone to leakage, forming highly combustible mixtures with air in confined spaces. The wide flammability range and low ignition energy of hydrogen make it highly susceptible to accidental ignition25,26. On the other hand, methane is less prone to leakage than hydrogen; however, it remains highly flammable and can potentially form explosive mixtures in air27,28.

This section presents an analysis focused on identifying the fire and explosion hazards associated with hydrogen and methane. To achieve this, a comparative study was conducted where hydrogen (\(\textrm{H}_2\)) was analyzed alongside methane (\(\textrm{CH}_4\)), propane (\(\textrm{C}_3\,\textrm{H}_8\)), and acetylene (\(\textrm{C}_2\,\textrm{H}_2\)). In this analysis, propane was selected because it represents a commonly used fuel gas that is widely utilized in domestic29 and industrial applications30. On the other hand, acetylene was selected because it has one of the widest flammability ranges among hydrocarbon gases, making it highly prone to forming flammable mixtures with air31. Additionally, acetylene has very low ignition energy32 and a high flame speed33, presenting significant safety challenges. By comparing these gases, we aim to establish benchmarks that will enhance our understanding of the potential risks associated with hydrogen and methane. In this analysis, we followed the methodology developed by Crowl and Jo34, incorporating additional important factors that were not considered in their study.

Physicochemical properties related to the hazards and risks of fuels

The flammability of different fuels under similar pressure and temperature conditions depends primarily on their physicochemical properties. Table 1 presents the main factors influencing fire and explosion hazards associated with flammable fluids in storage facilities. It also details how changes in these factors can affect the probability or consequence of fire incidents by indicating the direction of increased hazard.

As seen in Table 1, a lower LFL means that less vapor is needed to form a flammable mixture, while a higher UFL indicates a wider flammable range. A lower MOC, lower autoignition temperature, and lower minimum spark ignition energy all increase fire probability. Higher density increases gas accumulation, thereby increasing the probability of reaching flammable levels. Smaller molecular sizes increase the likelihood of gas leakage through cracked or damaged containers, thus elevating the probability of ignition. Additionally, a smaller quenching distance and lower boiling point increase the probability of fire.

In terms of fire consequence, a higher flame speed leads to faster spread of fires, increasing the rate of damage. A higher LHV, higher adiabatic flame temperature, and higher thermal conductivity all increase the consequence of fire incidents. A higher deflagration index indicates a more robust explosion, resulting in greater physical consequences. The deflagration index (\(K_G\)) is often utilized to eliminate the effect of the volume of the combustion vessel35. It is calculated using the following equation (Eq. (1)):

where V is the volume of the vessel, P is the pressure, t is the time, and \((dP/dt)_{\text {max}}\) is the maximum rate of pressure rise measured. The deflagration index depends mainly on the properties of the fuel mixture, such as composition, initial pressure, and temperature, and it can be effectively used to indicate the explosion severity in practical applications35.

The physical properties of hydrogen, methane, propane, and acetylene at atmospheric conditions (\(\sim\)1 atm and \(\sim\)298 K) are shown in Table 2. Hydrogen has a low LFL (4.2%) and a high UFL (74%), indicating a broad flammable range. It also has a low MOC (4%) and very low spark ignition energy (0.02 mJ), making it highly reactive and easily ignitable. The high flame speed (207 cm/s) and high deflagration index (638 bar\(\cdot\)m/s) of hydrogen indicate rapid fire spread and significant explosion potential. Methane, with an LFL of 5% and UFL of 14.9% has a narrower flammable range compared to hydrogen. Compared to other gases, propane has a relatively higher density (1.832 kg/\({\textrm{m}}^{3}\)), increasing accumulation risk. Acetylene has a very low LFL (2.6%), a very high UFL (80%) and the lowest autoignition temperature (578.15 K), therefore it is extremely combustible. Overall, hydrogen, methane, propane, and acetylene show varying hazard levels based on these parameters, which will be evaluated in the next subsection.

Analysis of fuel hazards

To assess the fire and explosion hazards, hydrogen, methane, propane, and acetylene were compared to each other, as shown in Table 3. Each gas was assessed for various physicochemical properties to determine which gas poses the greatest hazard, following the methodology developed by Crowl and Jo34. A value of “1” was assigned to the gas with the highest hazard for each property. The totals were then summed at the bottom of Table 3 to provide a comparative hazard score, indicating the totals for probability factors and consequence factors.

As shown in Table 3, hydrogen scores 12 out of 14 compared to methane, which scores 2. This indicates that hydrogen exhibits a significantly higher hazard potential than methane. When comparing hydrogen and propane, hydrogen ranks higher in 11 out of 14 factors. This also suggests a greater fire risk associated with hydrogen. In the assessment of hydrogen against acetylene, both gases exhibit a comparable hazard profile, each scoring 7 out of 14. However, hydrogen scores 3 in probability factors while acetylene scores 6. This means that acetylene has a higher probability of ignition and fire under typical atmospheric conditions. This is due to factors such as the wider flammability range, lower autoignition temperature, lower minimum spark ignition energy, higher gas density, and smaller quenching distance of acetylene compared to hydrogen. On the other hand, hydrogen scores 4 in consequence factors compared to acetylene, which scores 1, suggesting that the consequences of hydrogen fires are expected to be more severe. According to Table 3, acetylene is significantly more hazardous than methane and propane, scoring 10 out of 14 compared to methane and 11 out of 14 compared to propane. Meanwhile, propane and methane exhibit similar hazard levels, with both scoring 7 out of 14. Figure 3 summarizes the total hazards associated with hydrogen, methane, propane, and acetylene from all comparison cases. Hydrogen has the highest total hazard score of 30. Acetylene follows with a total of 28. Both methane and propane have equal total hazard scores of 13. This means that hydrogen and acetylene pose the greatest overall fire risk.

Evaluation of energy output, \(\textrm{CO}_2\) emissions, and cost-effectiveness of converting natural gas into hydrogen

In the previous section, we examined the safety hazards associated with hydrogen and natural gas. In this section, we will analyze the main environmental, energy, and economic implications of converting one kilogram of natural gas (NG) into various fuel forms, including liquefied natural gas (LNG), grey hydrogen gas (grey \(\textrm{H}_2\)), grey liquid hydrogen (grey \(\textrm{LH}_2\)), blue hydrogen gas (blue \(\textrm{H}_2\)), and blue liquid hydrogen (blue \(\textrm{LH}_2\)). Our analysis will focus on comparing the energy output, \(\textrm{CO}_2\) emissions, and cost-profit factors associated with each conversion process. This analysis builds on findings from our previous publication (Massarweh et al.62), with detailed calculations provided in spreadsheet format in Appendix A (supplementary data).

As a sample calculation, we consider the case of grey \(\textrm{H}_2\). The energy embodied in producing 1 kg of grey \(\textrm{H}_2\), taken from Massarweh et al.62, is 164.42 MJ. This amount includes both the energy stored within the material and the energy consumed during its different production stages. To calculate the NG-to-fuel conversion ratio, we divide the embodied energy in the fuel by the LHV of NG, as shown in Eq. (2). For grey \(\textrm{H}_2\), this ratio is 164.42 MJ/kg / 48.6 MJ/kg = 3.38. This indicates that 3.38 kg of NG are required to produce 1 kg of grey \(\textrm{H}_2\). For other fuels, the mass of NG needed to produce 1 kg of fuel, calculated similarly, is as follows: LNG requires 1.06 kg of NG, grey \(\textrm{LH}_2\) requires 4.12 kg, blue \(\textrm{H}_2\) requires 3.84 kg, and blue \(\textrm{LH}_2\) requires 4.58 kg.

To calculate the final energy output per 1 kg of NG converted to fuel, we divide the LHV of the fuel by the NG-to-fuel conversion ratio, as demonstrated in Eq. (3). The LHV of \(\textrm{H}_2\) is 119.94 MJ/kg. Thus, for grey \(\textrm{H}_2\), the energy output is 119.94 MJ/kg / 3.38, which equals 35.45 MJ (0.03545 GJ). This means, as expected, that the energy output from the converted fuel is less than the energy content of the original NG (approximately 48.6 MJ/kg) due to conversion inefficiencies.

To calculate the profit per 1 kg of NG converted to fuel, we need the market price of 1 kg of fuel, the total production cost of 1 kg of fuel, and the NG-to-fuel conversion ratio (3.38 as shown above). In our calculations, we used a market price for \(\textrm{H}_2\) of $3/kg. The total production cost of grey \(\textrm{H}_2\), taken from Massarweh et al.62, is $0.94/kg fuel. Based on this, the cost of converting 1 kg of NG to grey \(\textrm{H}_2\) is $0.94 / 3.38, which equals $0.278 per 1 kg NG. The profit per 1 kg of grey \(\textrm{H}_2\) is then calculated as $3.00/kg - $0.940/kg = $2.060/kg. Finally, the net profit from converting 1 kg of NG to grey \(\textrm{H}_2\) is $2.06 / 3.38, which equals $0.609 per 1 kg of NG. The cost per 1 kg NG, the profit per 1 kg fuel, and the net profit per 1 kg NG are calculated as shown in Eqs. (4), (5), and (6), respectively:

To determine the \(\textrm{CO}_2\) emissions resulting from 1 kg of NG converted to fuel, we first need the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emissions resulting from fuel production and utilization. As given by Massarweh et al.62, the emission value for grey \(\hbox {H}_2\) is 93.67 kg \(\hbox {CO}_2\)/GJ of fuel. Based on this, the amount of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emissions resulting from 1 kg of NG converted to grey \(\hbox {H}_2\) is calculated as 93.67 kg \(\hbox {CO}_2\)/GJ \(\times\) 0.03545 GJ = 3.32 kg \(\hbox {CO}_2\) per 1 kg of NG. As indicated above, Appendix A (supplementary data) provides a detailed breakdown of all calculations. The \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emissions per 1 kg NG are calculated using the following equation (Eq. (7)):

Cost-profit evaluation

The cost and profit per 1 kg of NG converted to various fuel forms are presented in Fig. 4, considering the production costs and market prices given in Table 4. The cost of producing 1 kg of NG without any conversion is $0.120, yielding a net profit of $0.011. When NG is converted to LNG, the cost increases to $0.435 per kg of NG but results in a profit of $0.061 per kg of NG.

Converting NG to grey \(\hbox {H}_2\) is highly profitable, with a production cost of $0.278 per kg of NG and a net profit of $0.609 per kg of NG. When NG is converted to grey \(\hbox {LH}_2\), the cost increases to $0.713 per kg of NG. However, grey \(\hbox {LH}_2\) remains highly profitable, leading to a net profit of $0.500 per kg of NG. In the case of blue \(\hbox {H}_2\), the conversion results in a net profit of $0.390 per kg of NG. Lastly, converting NG to blue \(\hbox {LH}_2\) involves the highest production cost, which is $0.851 per kg of NG, but still yields a net profit of $0.240 per kg of NG. Overall, given the market prices of hydrogen, converting NG to grey \(\hbox {H}_2\) delivers the highest net profit. Furthermore, although blue \(\hbox {LH}_2\) production entails the highest costs, it remains a profitable investment.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate how uncertainties in production costs and market prices affect the profitability of converting NG into various fuel forms, as shown in Fig. 5 (a through f). The baseline prices and costs used in this analysis are given in Table 4, with a sensitivity range of -20% to 20% applied to both parameters. Detailed calculations for the sensitivity analysis are included in Appendix A (supplementary data), based on Eq. (8). NG exhibits high sensitivity to increases in production costs and reductions in market prices, which may render it unprofitable if production costs increase by 10% or 20%, or if market prices drop by similar margins. NG remains profitable when both production costs and market prices experience concurrent increases. LNG shows even greater sensitivity to production cost variations, particularly with a 20% increase in costs. LNG profitability is also compromised if market prices decrease by 20%. However, when both production costs and market prices rise, the positive effects of the price increase can offset the negative impact of higher production costs, resulting in a net positive profit for LNG. Grey \(\hbox {H}_2\) consistently maintains high net profits across all scenarios, demonstrating resilience to both cost and price fluctuations, while grey \(\hbox {LH}_2\) exhibits a similar trend but with slightly lower profit margins. Blue \(\hbox {H}_2\) and blue \(\hbox {LH}_2\) show decreasing profitability as production costs rise, yet they remain profitable under various market conditions. Overall, the conversion of NG into various hydrogen forms remains economically viable, whether production costs or market prices increase or decrease by 20%.

where P is the market price per 1 kg fuel, C is the production cost per 1 kg fuel, R is the NG-to-fuel conversion ratio, \(\delta _p\) is the fractional change in price, and \(\delta _c\) is the fractional change in cost (each can be 0, \(-0.2\), \(+0.2\), etc., depending on the scenario).

Final energy output

Figure 6 presents the final energy output per 1 kg of NG converted to various fuel forms. Initially, 1 kg of NG exhibits the highest energy output, which is 48.60 MJ. Upon conversion to LNG, the energy output decreases to 45.96 MJ per kg of NG. The liquefaction of NG, which requires 2.9 MJ/kg63, contributes to this reduction in energy output for all fuels.

When NG is converted to grey \(\hbox {H}_2\), the energy output decreases significantly to 35.45 MJ per kg of NG, indicating a substantial energy loss during the conversion process. This reduction becomes more pronounced when NG is converted to grey \(\hbox {LH}_2\), resulting in an energy output of 29.08 MJ per kg of NG. This reduction is attributed to the energy-intensive liquefaction process. On average, liquefying 1 kg of \(\hbox {H}_2\) requires 36 MJ64.

Blue hydrogen forms also show lower energy outputs compared to NG and LNG. Upon conversion to blue \(\hbox {H}_2\) and blue \(\hbox {LH}_2\), the energy outputs are 31.21 MJ and 26.17 MJ per kg of NG, respectively. The additional energy requirements for CCS technologies and the liquefaction process contribute to the lower energy outputs observed in blue hydrogen forms.

Resulting \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emissions

Figure 7 presents the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emissions per 1 kg of NG converted to various fuel forms. Initially, the production and utilization of 1 kg of NG result in \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emissions of 2.72 kg. When NG is converted to LNG, the emissions slightly increase to 3.12 kg \(\hbox {CO}_2\) per kg of NG. This increase reflects the emissions associated with the liquefaction process.

Figure 7 also shows that when NG is converted to grey \(\hbox {H}_2\), the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emissions increase to 3.32 kg \(\hbox {CO}_2\) per kg of NG. This increase is expected due to the lack of CCS during grey \(\hbox {H}_2\) production. The emissions further increase to 3.50 kg \(\hbox {CO}_2\) per kg of NG when converting NG to grey \(\hbox {LH}_2\), mainly because of the liquefaction process involved. It is important to highlight that if the energy used for the liquefaction process is sourced from renewables rather than fossil fuels, the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emissions could be reduced, making hydrogen production a less carbon-intensive process. Compared to other fuels, blue hydrogen forms exhibit significantly lower \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emissions. Blue \(\hbox {H}_2\) has emissions of 1.05 kg \(\hbox {CO}_2\) per kg of NG, while blue \(\hbox {LH}_2\) has emissions of 1.84 kg \(\hbox {CO}_2\) per kg of NG. The reduced emissions for blue hydrogen forms are primarily attributed to the implementation of CCS technologies, which capture a substantial portion of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) produced during hydrogen production.

Discussion on Hydrogen and natural gas liquefaction processes

The high costs associated with liquefying natural gas (NG) and hydrogen (\(\hbox {H}_2\)) primarily stem from the energy-intensive nature of the liquefaction processes. Although both gases undergo cooling and compression, specific technological demands differ significantly. NG liquefaction involves cooling to approximately \(-160^{\circ }{\textrm{C}}\), with prior removal of impurities such as carbon dioxide, hydrocarbons, sulfur compounds, and water vapor, thus increasing operational complexity and expenses65,66. One widely utilized NG liquefaction method is the cascade process, employing three refrigeration cycles with propane, ethylene, and methane refrigerants, each operating at distinct temperature ranges. Propane initiates cooling down to about \(-30^{\circ }{\textrm{C}}\), ethylene further reduces temperatures to around \(-90^{\circ }{\textrm{C}}\), and methane achieves the final liquefaction to \(-160^{\circ }{\textrm{C}}\). Despite that cascade liquefaction offers high thermal efficiency, the extensive equipment requirements associated with this process result in significantly elevated capital investment costs65.

Hydrogen liquefaction requires significantly lower temperatures, often below \(-203^{\circ }{\textrm{C}}\), necessitating specialized, costly cryogenic refrigerants such as neon and helium. Safety considerations due to hydrogen’s broader flammability range and lower ignition energy compared to NG further augment costs67,68. Common \(\hbox {H}_2\) liquefaction cycles include the simple Claude cycle, the Kapitza cycle, and the liquid nitrogen (\(\hbox {LN}_2\)) pre-cooled Linde-Hampson cycle. The simple Claude cycle recovers expansion work by replacing the throttle valve with an expander, benefiting from pre-cooling with \(\hbox {LN}_2\) for enhanced efficiency. Conversely, the Kapitza cycle simplifies equipment by reducing heat exchangers and operating at lower pressures, while the Linde-Hampson cycle mandates \(\hbox {LN}_2\) pre-cooling due to \(\hbox {H}_2\)’s lower maximum conversion temperature69. In hydrogen liquefaction, helium and neon serve as alternative refrigerants alongside nitrogen, with helium is mainly used because of its excellent refrigerant properties, allowing for highly efficient cooling cycles70,71.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that hydrogen poses significantly higher safety risks than NG. This necessitates the implementation of rigorous safety protocols and advanced storage technologies to mitigate potential hazards associated with hydrogen leakage and accidental ignition. Based on the hazard analysis, hydrogen scored 12 out of 14 in hazard factors compared to methane’s score of 2. From an energy perspective, converting NG to blue and grey hydrogen results in substantial energy losses. While 1 kg of NG yields 48.6 MJ, conversion to grey hydrogen and blue hydrogen results in energy outputs of 35.45 MJ and 31.21 MJ, respectively. This indicates a need for more efficient production processes.

Environmentally, blue hydrogen offers a substantial reduction in emissions compared to NG, LNG, and grey hydrogen. Converting 1 kg of NG to blue hydrogen results in only 1.05 kg of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emissions, compared to 2.72 kg for NG, 3.12 kg for LNG, and 3.32 kg for grey hydrogen. This highlights the potential role of blue hydrogen in achieving low-carbon energy goals through CCS implementation. From an economic perspective, our study found that converting NG to hydrogen, particularly grey hydrogen, is highly profitable under current market conditions. Grey hydrogen conversion yields a net profit of $0.609 per kg of NG. Blue hydrogen, while less profitable due to CCS costs, remains viable with a profit of $0.390 per kg of NG.

In conclusion, adopting hydrogen as an alternative energy carrier or fuel requires careful consideration of trade-offs between safety, energy efficiency, environmental sustainability, and economic viability. While this study provides a systematic and standardized comparison, it remains limited by three main factors. First, the economic analysis is constrained by specific geographic and temporal conditions. Second, the safety assessment methodology relies primarily on comparisons of physicochemical properties under standard conditions. Third, the study does not consider other colors of hydrogen, such as green, turquoise, or brown. Therefore, future research should conduct economic analyses that account more comprehensively for price volatility, for example, by using probabilistic or stochastic approaches. Moreover, researchers should explore safety analyses across a broader range of storage and transportation conditions and operational scenarios. Finally, future studies should investigate methods for improving hydrogen production and liquefaction technologies, enhancing CCS efficiency, and developing comprehensive safety measures to unlock the full potential of hydrogen in the clean energy transition.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Keith, D. W. Dangerous Abundance. New York 1–20 (2009).

Haibin, L. & Zhenling, L. Recycling utilization patterns of coal mining waste in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 54, 1331–1340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.05.005 (2010).

Allen, L., Cohen, M. J., Abelson, D. & Miller, B. Fossil Fuels and Water Quality. In Gleick, P. H. (ed.) The World’s Water, 73–96, https://doi.org/10.5822/978-1-59726-228-6_4 (Island Press/Center for Resource Economics, Washington, DC, 2012).

Chittick, E. A. & Srebotnjak, T. An analysis of chemicals and other constituents found in produced water from hydraulically fractured wells in California and the challenges for wastewater management. J. Environ. Manag. 204, 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.09.002 (2017).

Radelyuk, I., Tussupova, K., Klemeš, J. J. & Persson, K. M. Oil refinery and water pollution in the context of sustainable development: Developing and developed countries. J. Clean. Prod. 302, 126987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126987 (2021).

Massarweh, O. & Abushaikha, A. S. Towards environmentally sustainable oil recovery: The role of sustainable materials. Energy Rep. 12, 95–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2024.06.013 (2024).

Yoro, K. O. & Daramola, M. O. CO2 emission sources, greenhouse gases, and the global warming effect. In Rahimpour, M. R., Farsi, M. & Makarem, M. A. B. T. A. i. C. C. (eds.) Advances in Carbon Capture, 3–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819657-1.00001-3 (Elsevier, 2020).

Energy Institute. Statistical Review of World Energy (2023).

Our World in Data. Global Primary Energy Share Including Biomass (2023).

Massarweh, O. & Abushaikha, A. S. CO2 sequestration in subsurface geological formations: A review of trapping mechanisms and monitoring techniques. Earth-Sci. Rev. 253, 104793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2024.104793 (2024).

Ndwali, K., Njiri, J. G. & Wanjiru, E. M. Multi-objective optimal sizing of grid connected photovoltaic batteryless system minimizing the total life cycle cost and the grid energy. Nat. Energy 148, 1256–1265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.10.065 (2020).

Safari, A., Das, N., Langhelle, O., Roy, J. & Assadi, M. Natural gas: A transition fuel for sustainable energy system transformation?. Energy Sci. Eng. 7, 1075–1094. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.380 (2019).

Timmerberg, S., Kaltschmitt, M. & Finkbeiner, M. Hydrogen and hydrogen-derived fuels through methane decomposition of natural gas – GHG emissions and costs. Energy Convers. Manag.: X 7, 100043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecmx.2020.100043 (2020).

McCay, M. H. & Shafiee, S. Hydrogen. In Letcher, T. M. B. T. F. E. T. E. (ed.) Future Energy, 475–493, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102886-5.00022-0 (Elsevier, 2020).

Saha, P. et al. Grey, blue, and green hydrogen: A comprehensive review of production methods and prospects for zero-emission energy. Int. J. Green Energy 21, 1383–1397. https://doi.org/10.1080/15435075.2023.2244583 (2024).

Udemu, C. & Font-Palma, C. Potential cost savings of large-scale blue hydrogen production via sorption-enhanced steam reforming process. Energy Convers. Manag. 302, 118132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118132 (2024).

Hermesmann, M. & Müller, T. Green, Turquoise, Blue, or Grey? Environmentally friendly Hydrogen Production in Transforming Energy Systems. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 90, 100996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2022.100996 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Safety of hydrogen storage and transportation: An overview on mechanisms, techniques, and challenges. Energy Rep. 8, 6258–6269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.04.067 (2022).

Gharehghani, A. & Fakhari, A. H. Natural Gas as a Clean Fuel for Mobility. 215–241, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8747-1_11 (Springer Singapore, Singapore, 2022).

Hisschemöller, M. & Bode, R. Institutionalized knowledge conflict in assessing the possible contributions of H2 to a sustainable energy system for the Netherlands. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 36, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.09.024 (2011).

Crane, J. & Dinh, C.-T. Strategies for decarbonizing natural gas with electrosynthesized methane. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 101027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrp.2022.101027 (2022).

Tamburini, F., Bonvicini, S. & Cozzani, V. Consequences of subsea CO2 blowouts in shallow water. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 183, 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2024.01.008 (2024).

Nasr, G. G. & Connor, N. E. Natural Gas Engineering and Safety Challenges. London 418, 418. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08948-5 (2014).

Qureshi, F. et al. A State-of-The-Art Review on the Latest trends in Hydrogen production, storage, and transportation techniques. Fuel 340, 127574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.127574 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Analysis of the ignition of hydrogen/air mixtures induced by a hot particle. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 21188–21197. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2CP02409H (2022).

Wilkening, H. & Baraldi, D. CFD modelling of accidental hydrogen release from pipelines. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 32, 2206–2215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2007.04.022 (2007).

Cristello, J. B., Yang, J. M., Hugo, R., Lee, Y. & Park, S. S. Feasibility analysis of blending hydrogen into natural gas networks. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 17605–17629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.01.156 (2023).

Sun, X. & Lu, S. On the mechanisms of flame propagation in methane-air mixtures with concentration gradient. Energy 202, 117782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.117782 (2020).

Murr, L., Bang, J., Esquivel, E., Guerrero, P. & Lopez, D. Carbon Nanotubes, Nanocrystal Forms, and Complex Nanoparticle Aggregates in common fuel-gas combustion sources and the ambient air. J. Nanoparticle Res. 6, 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:NANO.0000034651.91325.40 (2004).

Chen, S. et al. Propane dehydrogenation: catalyst development, new chemistry, and emerging technologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 3315–3354. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0CS00814A (2021).

Mashuga, C. V. & Crowl, D. A. Application of the flammability diagram for evaluation of fire and explosion hazards of flammable vapors. Process Saf. Prog. 17, 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/prs.680170305 (1998).

Anand, M., Devi, G., Raghavendra, S. G., Prakasha, G. S. & Lakshmanan, T. A critical study on acetylene as an alternative fuel for transportation. In AIP Conference Proceedings 2396, 020005. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0066773 (2021).

Ravi, S., Sikes, T., Morones, A., Keesee, C. & Petersen, E. Comparative study on the laminar flame speed enhancement of methane with ethane and ethylene addition. Proc. Combust. Inst. 35, 679–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proci.2014.05.130 (2015).

Crowl, D. A. & Jo, Y.-D. The hazards and risks of hydrogen. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 20, 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2007.02.002 (2007).

Zhou, Q., Cheung, C., Leung, C., Li, X. & Huang, Z. Explosion characteristics of bio-syngas at various fuel compositions and dilutions in a confined vessel. Fuel 259, 116254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116254 (2020).

Medisetty, V. M. et al. Overview on the Current Status of Hydrogen Energy Research and Development in India. Chem. Eng. Technol. 43, 613–624. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceat.201900496 (2020).

Dimitriou, P. & Javaid, R. A review of ammonia as a compression ignition engine fuel. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45, 7098–7118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.12.209 (2020).

Griffiths, J., Coppersthwaite, D., Phillips, C., Westbrook, C. & Pitz, W. Auto-ignition temperatures of binary mixtures of alkanes in a closed vessel: Comparisons between experimental measurements and numerical predictions. Symposium (International) on Combustion 23, 1745–1752, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0082-0784(06)80452-2 (1991).

Masuk, N. I., Mostakim, K. & Kanka, S. D. Performance and Emission Characteristic Analysis of a Gasoline Engine Utilizing Different Types of Alternative Fuels: A Comprehensive Review. Energy & Fuels 35, 4644–4669. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c04112 (2021).

Aleiferis, P. G. & Rosati, M. F. Controlled autoignition of hydrogen in a direct-injection optical engine. Combust. Flame 159, 2500–2515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2012.02.021 (2012).

Eckhoff, R., Ngo, M. & Olsen, W. On the minimum ignition energy (MIE) for propane/air. J. Hazard. Mater. 175, 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.09.162 (2010).

Escamilla, A., Sánchez, D. & García-Rodríguez, L. Assessment of power-to-power renewable energy storage based on the smart integration of hydrogen and micro gas turbine technologies. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 17505–17525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.03.238 (2022).

Wilson, M., Worrall, F., Davies, R. & Hart, A. A dynamic baseline for dissolved methane in English groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 711, 134854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134854 (2020).

Barclay, J. et al. Propane liquefaction with an active magnetic regenerative liquefier. Cryogenics 100, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cryogenics.2019.01.009 (2019).

Abid, H. R., Yekeen, N., Al-Yaseri, A., Keshavarz, A. & Iglauer, S. The impact of humic acid on hydrogen adsorptive capacity of eagle ford shale: Implications for underground hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 55, 105615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2022.105615 (2022).

Dehghan, F., Rashidi, A., Parvizian, F. & Moghadassi, A. Pore size engineering of cost-effective all-nanoporous multilayer membranes for propane/propylene separation. Sci. Rep. 13, 21419. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48841-8 (2023).

Li, J.-R., Kuppler, R. J. & Zhou, H.-C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1477. https://doi.org/10.1039/b802426j (2009).

Thawko, A. & Tartakovsky, L. The Mechanism of Particle Formation in Non-Premixed Hydrogen Combustion in a Direct-Injection Internal Combustion Engine. Fuel 327, 125187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125187 (2022).

Crittenden, T., Glezer, A., Funk, R. & Parekh, D. Combustion-driven jet actuators for flow control. In 15th AIAA Computational Fluid Dynamics Conference, Fluid Dynamics and Co-located Conferences, https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2001-2768 (American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Reston, Virigina, 2001).

Liu, H., Geng, C., Yang, Z., Cui, Y. & Yao, M. Effect of Wall Temperature on Acetylene Diffusion Flame-Wall Interaction Based on Optical Diagnostics and CFD Simulation. Energies 11, 1264. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11051264 (2018).

Jerzembeck, S., Peters, N., Pepiotdesjardins, P. & Pitsch, H. Laminar burning velocities at high pressure for primary reference fuels and gasoline: Experimental and numerical investigation. Combust. Flame 156, 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2008.11.009 (2009).

Kovač, A., Paranos, M. & Marciuš, D. Hydrogen in energy transition: A review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 10016–10035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.11.256 (2021).

Al-Breiki, M. & Bicer, Y. Comparative cost assessment of sustainable energy carriers produced from natural gas accounting for boil-off gas and social cost of carbon. Energy Rep. 6, 1897–1909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2020.07.013 (2020).

Hodges, K. A., Aniello, A., Krishnan, S. R. & Srinivasan, K. K. Impact of propane energy fraction on diesel-ignited propane dual fuel low temperature combustion. Fuel 209, 769–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2017.07.096 (2017).

Wang, Z., Zheng, D. & Jin, H. A novel polygeneration system integrating the acetylene production process and fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 32, 4030–4039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2007.03.018 (2007).

Beita, J., Talibi, M., Sadasivuni, S. & Balachandran, R. Thermoacoustic Instability Considerations for High Hydrogen Combustion in Lean Premixed Gas Turbine Combustors: A Review. Hydrogen 2, 33–57. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen2010003 (2021).

Babushok, V., Linteris, G., Katta, V. & Takahashi, F. Influence of hydrocarbon moiety of DMMP on flame propagation in lean mixtures. Combust. Flame 171, 168–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2016.06.019 (2016).

Raman, R. & Kumar, N. The utilization of n-butanol/diesel blends in Acetylene Dual Fuel Engine. Energy Rep. 5, 1030–1040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2019.08.005 (2019).

Senecal, J. A. & Beaulieu, P. A. K G : New data and analysis. Process Saf. Prog. 17, 9–15, https://doi.org/10.1002/prs.680170104 (1998).

Schildberg, H.-P. Experimental determination of the static equivalent pressures of detonative decompositions of acetylene in long pipes and chapman-jouguet pressure ratio. In Volume 5: High-Pressure Technology; ASME NDE Division; 22nd Scavuzzo Student Paper Symposium and Competition, vol. Volume 5: High-Pressure Technology; ASME NDE Division; 22nd Scavuzzo Student Paper Symposium and Competition of Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference, V005T05A018, https://doi.org/10.1115/PVP2014-28197 (2014).

Huber, M. L. & Harvey, A. H. Thermal conductivity of gases. In CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2011), 92nd edn. Tables of thermal conductivity of common gases as a function of temperature.

Massarweh, O., Al-khuzaei, M., Al-Shafi, M., Bicer, Y. & Abushaikha, A. S. Blue hydrogen production from natural gas reservoirs: A review of application and feasibility. Journal of CO2 Utilization 70, 102438, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2023.102438 (2023).

Le, S., Lee, J.-Y. & Chen, C.-L. Waste cold energy recovery from liquefied natural gas (LNG) regasification including pressure and thermal energy. Energy 152, 770–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.03.076 (2018).

Trevisani, L., Fabbri, M., Negrini, F. & Ribani, P. Advanced energy recovery systems from liquid hydrogen. Energy Convers. Manag. 48, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2006.05.002 (2007).

He, T., Karimi, I. A. & Ju, Y. Review on the design and optimization of natural gas liquefaction processes for onshore and offshore applications. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 132, 89–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2018.01.002 (2018).

Choi, M. S. LNG for Petroleum Engineers. SPE Projects, Facilities & Construction 6, 255–263. https://doi.org/10.2118/133722-PA (2011).

Aasadnia, M. & Mehrpooya, M. Large-scale liquid hydrogen production methods and approaches: A review. Appl. Energy 212, 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.12.033 (2018).

Dawood, F., Anda, M. & Shafiullah, G. Hydrogen production for energy: An overview. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45, 3847–3869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.12.059 (2020).

Yin, L. & Ju, Y. Review on the design and optimization of hydrogen liquefaction processes. Front. Energy 14, 530–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11708-019-0657-4 (2020).

Shimko, M. A. & Gardiner, M. R. Iii. 7 innovative hydrogen liquefaction cycle. FY 2008 Annual Progress Report, DOE Hydrogen Program (2008).

Staats, W. L. Analysis of a supercritical hydrogen liquefaction cycle (2008).

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by Qatar National Research Fund under the Academic Research Grant, project number ARG01-0502-230056.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.M., Y.B., and A.A. developed the methodology. O.M. conducted the analysis, verification, visualization, writing, and contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript. A.A. provided supervision, project administration, verification, funding acquisition, writing, and reviewing. All authors contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Massarweh, O., Bicer, Y. & Abushaikha, A. Technoeconomic analysis of hydrogen versus natural gas considering safety hazards and energy efficiency indicators. Sci Rep 15, 29601 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14686-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14686-6