Abstract

Building segmentation of high-resolution remote sensing images using deep learning effectively reduces labor costs, but still faces the key challenges of effectively modeling cross-scale contextual relationships and preserving fine spatial details. Current Transformer-based approaches demonstrate superior long-range dependency modeling, but still suffer from the problem of progressive information loss during hierarchical feature encoding. Therefore, this study proposed a new semantic segmentation network named SegTDformer to extract buildings in remote sensing images. We designed a Dynamic Atrous Attention (DAA) fusion module that integrated multi-scale features from Transformer, constructing an information exchange between global information and local representational information. Among them, we introduced the Shift Operation module and the Self-Attention module, which adopt a dual-branch structure to respectively capture local spatial dependencies and global correlations, and perform weight coupling to achieve highly complementary contextual information fusion. Furthermore, we fused triplet attention with depth-wise separable convolutions, reducing computational requirements and mitigating potential overfitting scenarios. We benchmarked the model on three different datasets, including Massachusetts, INRIA, and WHU, and the results show that the model consistently outperforms existing models. Notably, on the Massachusetts dataset, the SegTDformer model achieved benchmark in mIoU, F1-score, and Overall Accuracy of 75.47%, 84.7%, and 94.61%, respectively, superseding other deep learning models. The proposed SegTDformer model exhibits enhanced precision in the extraction of urban structures from intricate environments and manifests a diminished rate of both omission and internal misclassification errors, particularly within the context of diminutive and expansive edifices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid advancement of deep learning technologies and the continuous refinement of remote sensing techniques, the use of deep learning to extract building information from high-resolution remote sensing (HRS) imagery has become a highly efficient and accurate method1. This technology is applied in various fields including urban planning2urban dynamic monitoring3and disaster detection4. Although research on the extraction of buildings from HRS images using deep learning has achieved some results, there remain several challenges and issues to be addressed. For instance, the diversity and complex shapes of buildings in HRS images, coupled with the effects of occlusions and variations in illumination, can impact the accuracy and robustness of building extraction. Consequently, further optimization of deep learning algorithms to enhance the precision and efficiency of building extraction has become one of the significant research topics of the present.

In recent years, the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model, as a type of deep learning neural network, has achieved notable success, especially with the Fully Convolutional Network (FCN)5 model demonstrating exceptional performance. FCN is an end-to-end network model that exclusively utilizes convolutional layers, avoiding the fully connected layers typical of traditional CNN models. This adaptation allows for better accommodation of input images of various sizes. With ongoing innovation by researchers, many models with outstanding structures have emerged, such as UNet6 and DeeplabV3+7. UNet features a U-shaped structure, processing images through an encode-decode mechanism to output segmentation results. The DeeplabV3 + model incorporates the Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module, facilitating better integration of objects across different scales and enhancing segmentation accuracy.

HRS imagery presents unique challenges for building segmentation due to two inherent characteristics: small-scale building structures and complex environmental contexts8. Conventional convolutional neural networks often exhibit limited capacity in capturing fine-grained semantic information at smaller scales9particularly when vegetation occlusion introduces ambiguous spatial relationships. These challenges necessitate architectural designs that enhance contextual reasoning and local dependency modeling within segmentation frameworks10,11. Critically, the effective utilization of multi-scale information remains a fundamental yet under-addressed requirement in HRS building segmentation. Small-scale targets12 (e.g., compact residential buildings) suffer severe feature degradation in standard encoder-decoder architectures due to repeated downsampling13while complex scene compositions demand adaptive fusion of hierarchical semantic features14. Recent studies have demonstrated that static multi-scale fusion strategies in existing methods (e.g., ASPP, FPN) inadequately resolve the scale variance problem in HRS scenarios, where optimal receptive fields vary significantly across spatial locations. This limitation motivates our investigation into dynamic multi-scale feature interaction mechanisms tailored for HRS-specific challenges.

Attention mechanisms have emerged as pivotal solutions to address these challenges through learnable feature recalibration. The research evolution progresses along three technical pathways: (1) Channel-spatial recalibration: SENet15 pioneered channel attention through squeeze-excitation blocks, while GENet16 extended this to spatial dimensions. Subsequent innovations like SKNet17 introduced multi-branch architectures with adaptive kernel selection, and CBAM18 systematically combined channel and spatial attention through sequential modules. TLSTM networks19 based on spatial attention increase transduction of long and short-term memory for time series detection (2) Global context modeling: Non-local networks20 established global self-attention for long-range dependencies, inspiring GCNet’s21 efficient channel-wise attention and DANet’s22 dual attention mechanism for spatial-channel context fusion. Practical implementations like OCRNet23 demonstrated effective class-conditional attention for urban scene parsing. In addition, to reduce information redundancy, FDNet24 optimizes spectral feature learning by compressing redundant information while highlighting information-rich spectral bands. MCKTNet25 combines channel discrete loss and spatial discrete loss to facilitate cross-modal migration of geometrical and semantic features, and reduces redundancy by minimizing differences in feature distribution. (3) Computational efficiency optimization: Recent works address computational overhead through dimension-aware interactions (Triplet Attention26, energy-based importance weighting (SimAM27, and hybrid convolution-attention designs (ACmix28. Notably, while these advancements enhance feature discrimination, their capacity for multi-scale context integration remains constrained by fixed-scale attention computations, particularly ineffective for resolving the scale-confusion issues prevalent in HRS building segmentation tasks. LWGANet29 cleverly utilizes redundant features to extract a wide range of spatial information from local to global scales without introducing additional complexity or computational overhead. This facilitates accurate feature extraction across multiple scales within an efficient framework. Facing the small object problem in remote sensing tasks, DecoupleNet30 preserves small object features during downsampling and enhances small and multi-scale object feature representation through a novel decoupling approach.

The recent paradigm shift towards Vision Transformers (ViT)31 has further expanded architectural possibilities. Initial adaptations like DETR32 introduced end-to-end detection through transformer encoders-decoders, while ViT established patch-based sequence processing for classification. Subsequent architectural innovations addressed computational scalability: Swin Transformer33 employed hierarchical feature learning with shifted windows, and SegFormer34 introduced an efficient pyramid transformer for semantic segmentation. However, current transformer-based approaches primarily focus on modeling long-range dependencies, often resulting in a loss of fine-grained spatial details of small-scale structures during patch embedding operations. Additionally, these methods exhibit limited dynamic adaptability to scale variations in complex urban landscapes. To accurately capture semantic information in remote sensing images, FTransDeepLab35 extends the encoder by stacking multi-scale Segformers to encode the input images into highly representative spatial features. DSymFuser36 fully exploits and exploits remote sensing images by adaptively aggregating local and global features extracted with CNN-Transformer network depth information. The above articles have made significant contributions to information mining. However, due to the richness of information in remote sensing images, redundancy and conflicting information are easily generated in the process of multi-scale fusion.

To improve the efficiency of multi-scale information utilization, we designed a building extraction network named SegTDformer. Dynamic Atrous Attention (DAA) designed to focus on increasing the fusion weight of key information by considering the information distribution, thereby strengthening the relevance of the information context in the multi-scale fusion process in depth. To verify the validity of the model, we conducted comparative experiments with PSPNet37DeepLabV3 + , HRNet38B-FGC-Net39Segformer34TDNet40DSymFuser36GDGNet41 and SparseFormer42 on the three datasets Massachusetts, INRIA, and WHU.

The main contributions of this article are given as follows.

(1) This study designed a DAA feature fusion module. The module filters each feature source during the fusion process, suppressing erroneous information while enhancing the weight of critical information, thereby improving the utilization efficiency of feature information.

(2) By introducing the Shift operation model to dynamically obtain the distribution of feature fusion information, it can be combined with the Self attention model to improve the dependency between information.

(3) Before features are extracted at each layer and fed into the main trunk, a Triplet Attention (TA) mechanism is introduced, and a residual link structure is used to connect them. This approach not only enhances the backbone network’s ability to identify and capture target points but also effectively accelerates the convergence speed of the network.

(4) To enhance the applicability of the model to remote sensing image tasks, we maintain the computational load and the number of parameters within a controllable range, achieving a balance between accuracy and computational cost.

Related work

Remote sensing semantic segmentation based on CNN

The FCN is a classic model of CNN, which replaces the fully connected layers of the VGG configuration with convolutional layers. This adaptation permits the size of image input to be selected flexibly, giving CNN models an advantageous position for application in HRS imagery43,44. Based on the FCN, Pan et al. devised a universal automated method for road network extraction from HRS45. The success of the FCN-based deep learning model in the extraction of HRS imagery has gradually led to a recognition of the convenience of AI. Consequently, an increasing number of more advanced deep learning models are being applied in the field of HRS imagery. ResNet46 is a network structure with a residual connection, which lessens the negative impact of additional modules in experiments on the experimental results while mitigating the gradient explosion problem. This permits the model to have a deeper network structure and improves segmentation accuracy. ResNeXt47 replaced the residual module with separable convolutions, reducing the model parameters effectively and preventing overfitting in the model. Liu et al. proposed ARC-Net48 containing residual blocks with asymmetric convolution, which utilizes dilated convolution and multi-scale pyramid pooling modules to expand the perceptual field and improve accuracy at a small computational cost. Sun et al. proposed HRNet49 which integrates multiple branches of different resolutions in parallel, accompanied by continuous information exchange between the different branches. This approach achieves the simultaneous targeting of strong semantic information and precise positional information. The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)38 presented by Maggiori et al. offers a fresh connection form for the CNN models.

However, CNNs still possess shortcomings, such as the inability to capture global dependencies and a limited receptive field. Many researchers have attempted to integrate attention mechanisms into CNN models to address these issues. Chen et al. developed a change detection model based on a Dual Attention Fully Convolutional Siamese Network, DASNet50which addresses the lack of robustness to pseudo-information changes (such as noise) and the problem of class imbalance in samples. Zhou et al. proposed EDSANet51 to aggregate multilevel semantics and enhance the accuracy of building extraction. Li et al. proposed A2-FPN52which improves multi-scale feature learning and mitigates the loss of semantic information caused by the drastic reduction of channels through attention-guided feature fusion. Iqbal et al. introduced MSANet53utilizing multiple feature maps from a support image and a query image to accurately estimate semantic relationships. Chen et al. developed a HRS image change detection model based on spatiotemporal self-attention, STANet54which designed a CD self-attention mechanism to model spatiotemporal relations, enabling the model to capture spatiotemporal dependencies at different scales. Zhao et al.‘s SSAtNet utilizes a pyramid attention pooling module, incorporating the attention mechanism into multiscale modules for adaptive feature refinement55. Li et al.‘s MAResUNet introduced a Linear Attention Mechanism (LAM), enabling a more flexible and diverse integration of the attention mechanism with deep networks56.

Remote sensing semantic segmentation based on transformer

In recent years, CNN models have been increasingly replaced by Transformers, a trend evident in the field of semantic segmentation of HRS imagery as well. Transformers can effectively model the global context of an image, which is crucial for understanding the comprehensive scene depicted in HRS images. Zhang et al. designed a U-structured Transformer network, SwinSUNet57inspired by the UNet network architecture. Similarly, He et al. combined Swin Transformer with UNet, proposing a dual encoder network: ST-UNet8. This setup reduces the loss of information and thereby increases the segmentation accuracy of small-scale ground objects. Xu et al., proposed a lightweight Transformer model that accelerates training times on small size datasets and reduces computational consumption. Wu et al., introduced a novel encoder-decoder structured Transformer fused network, CMTFNet58aimed at improving the efficiency of extracting and fusing local information and multi-scale global context information from HRS images. Zhou et al., designed a dual-branch convolutional Transformer method with an Efficient Interactive Self-Attention (EISA), which enables a full convergence of local and global spatial spectral features59. Sun et al. suggested a Spectral–Spatial Feature Tokenization Transformer, introducing a Gaussian-weighted feature tokenizer to capture spectral spatial features and high-level semantic features60. Because of the bird’s-eye view perspective of HRS images, scenes can be complex with densely distributed targets. To address these challenges, Li et al. designed a pyramid-structured Transformer61leveraging the pyramid structure to facilitate context information interaction and enhancing the capacity to handle multi-scale information.

Methodology

The proposed SegTDformer architecture employs ViT backbone to capture low-level feature representations, followed by multi-dimensional feature enhancement through residual pathways in the TA module. Subsequently, the DAA dynamically integrates these refined features across scales, establishing a hierarchical information refinement pipeline that progressively resolves spatial-semantic ambiguities in complex environments.

Backbone overview

Our model employs a Transformer as the Backbone for extracting features from images, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The Transformer architecture is composed of multiple identical layers in both its encoder and decoder. Each encoder layer consists of two sub-layers: a self-attention mechanism and a feed-forward neural network. The self-attention layer enables the model to focus on other positions within the sequence when processing each position in the sequence. This is achieved through three vectors: Query, Key, and Value. These vectors are low-dimensional representations of the input data. the self-attention is estimated as:

where \(\:Q,\:K,V\) are the Query, Key, and Value matrices, respectively, and \(\:{d}_{k}\) is the dimension of the key vectors, introduced to scale the dot products for more stable gradients. The dot product shows the similarity between the queries and the keys; the softmax function is then applied to obtain the weights.

The model computes the correlation of each pixel with all others, a process that will significantly increase the computational load. To address this, our model employs a multi-head attention mechanism. Where traditional attention mechanisms use only one set of Query, Key, Value weights, multi-head attention uses multiple sets, each learning different parts of the sequence. Each “head” operates independently, capturing information in different subspaces, and then the outputs are concatenated. This enables the model to capture a more diverse range of information from the input data. Multi-head attention projects \(\:Q,K,V\) into \(\:h\) different sets of weight matrices \(\:{W}_{i}^{Q},{W}_{i}^{K},{W}_{i}^{V}\) and performs parallel attention calculations:

where \(\:{W}^{0}\) is another weight matrix used to combine the information from the different heads.

In order to better adapt to the task of building extraction in HRS images, considering both accuracy and training cost, we ultimately selected MiT-B0 as the backbone of our model. The specific parameters and other main components are detailed in Table 1. Many researchers have demonstrated that the features extracted by Transformers are insufficient for effectively segmenting buildings. We introduce the TA module to perform residual connections after each Transformer block to enhance the correlation of information at different scales. Subsequently, the output features at different scales are input into the DAA module for the fusion and coupling of feature information, thereby effectively capturing detailed information for efficient segmentation of target contours.

Framework overview of SegTDformer model. The images used in this figure are sourced from the Massachusetts dataset, and the dataset can be accessed at: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~vmnih/data/. Images were generated by Python software [version number 3.10, URL: https://www.python.org/downloads/].

DAA module

Similarly, Segformer also utilizes a Transformer to extract semantic information for performing semantic segmentation tasks. However, the multi-scale semantic information generated by the Transformer is not fully integrated, which limits its effectiveness in complex HRS imagery environments. To address this issue, we developed a DAA feature fusion module. This module integrates multi-level semantic information, establishing an interaction between representational information and global spatial information. Additionally, it employs two branches—the Shift Operation and the Self-Attention—to evaluate the cross-scale weight relationships and to construct dependencies across multiple spatial hierarchies. This design can compensate for the problem that the multi-scale feature information output by Transformer is not well correlated and the detail information is not efficiently learnt during training. In consideration of the increased computational demand introduced by the attention mechanism, we replaced standard convolutions with Depthwise Separable Convolution (DSC)62 to enhance operational efficiency. This is demonstrated in Fig. 2.

First, perform Depthwise Dilated Convolutions (DDC) for each input channel and then apply pointwise convolutions (1 × 1) to combine the features across channels. Given \(\:{I}_{c}\) as the input feature map channel c, and \(\:{D}_{c}\) as the result of the DDC with kernel \(\:{K}_{dc}\) and dilation rate \(\:r\):

where \(\:(p,\:q)\) represent convolution kernel offset indices, denoting spatial offsets within the kernel relative to the output feature map location \(\:(i,\:j)\). r represents the dilation rate.

Then, the pointwise convolution \(\:P\) is computed using 1 × 1 convolution kernel \(\:{K}_{1\times\:1}\):

In addition, the module employs a global average pooling (GAP) branch to extract global contextual information, which compresses the spatial dimensions of the input feature map to a single vector \(\:{G}_{c}\):

This vector is subsequently subjected to a channel-wise expansion via an upscaling 1 × 1 convolution to attain a feature map \(\:U\left(p,q\right)\):

The culmination of this approach is the concatenation of the multi-dilated convolutional features with the upscaled global features, yielding a multidimensional feature representation:

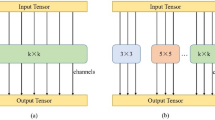

The feature fusion information \(\:F\) is imported into the attention module for information significance assessment. Fig. 3 shows the two main stages of information processing, the first stage shares the same 1 × 1 convolution operations between self-attention and convolution, with the output from this stage being a set of intermediate features obtained through 1 × 1 convolutions applied to the input features. The second stage then aggregates these intermediate features according to the respective mechanisms of shift operation and convolution. The equations of attention module are roughly as follows:

Shared by self-attention and convolution in Stage I:

where \(\:F\) is the input feature, and \(\:Q\), \(\:K\), and \(\:V\) are the queries, keys, and values matrices in the self-attention mechanism. \(\:{W}^{Q}\), \(\:{W}^{K}\), and \(\:{W}^{V}\) are the corresponding weight matrices.

(a) Shift Operation model. Each feature value is composed of a 3 × 3 convolutional sliding window. Each feature map is obtained by performing a 1 × 1 convolution on the convolutional kernel weights from a certain location. (b) Self-Attention model. The feature information is divided into three parts: Q, K, and V, to compute self-correlation information.

Convolution in Stage II:

where \(\:{K}_{c}\) is the convolutional kernel, \(\:\varDelta\:x\) and \(\:\varDelta\:y\) are the displacements in the horizontal and vertical directions, the operator \(\:*\) represents the convolution operation, and Sum and Shift represent the summation and shifting operations, respectively.

Self-attention in Stage II:

The final output is a linear combination of the aggregated features from these two paths:

where \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) are learned parameters used to balance the relative contributions of self-attention and convolution output feature maps.

Reduced parameter method

The number of parameters is also a standard by which the excellence of a model is judged. Usually, the effect is obvious when further processing feature information by adding modules. However, the computational overhead introduced by supplementary modules must be mitigated. Consequently, low-parameter modules are prioritized to achieve significant performance gains without inflating computational burden. One such module is the TA. As shown in Fig. 4, The depicted triplet attention mechanism comprises three distinct branches. The uppermost branch calculates attention across the channel dimension C and the spatial width dimension W. The central branch likewise attends to channel dimension C and spatial height dimension H. The concluding branch at the base captures spatial interdependencies between height H and width W. For the initial two branches, a rotation operation is employed to forge links between channel dimension and a single spatial dimension. Subsequently, these attention weights are consolidated by means of a straightforward averaging process. We use this module residual to connect two adjacent transformer blocks, making the output strongly correlated.

Experimental datasets and evaluation

Datasets

The Massachusetts dataset, proposed by Mnih63comprises 151 aerial images of the Boston area. Each image covers approximately 2.25 square kilometers and has a resolution of 1500 × 1500 with a spatial resolution of one meter. The dataset is divided into 137 training images, 4 validation images, and 10 test images. Every image is composed of three RGB channels, and it includes original images along with their respective labels, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Image and label example from the Massachusetts dataset. (a) Aerial image; (b) Label image; red for buildings and black for the background. The images used in this figure are sourced from the Massachusetts dataset, and the dataset can be accessed at: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~vmnih/data/.

The INRIA dataset, proposed by Maggiori64includes building data from various cities worldwide. Each image in this dataset has a resolution of 5000 × 5000 and a spatial resolution of 0.3 m. For this study, the dataset is split into three segments: training set and validation set, with a division ratio of 7:3 The aerial images and labels of the INRIA dataset can be observed in Fig. 6.

Image and label example selected from the INRIA dataset: (a) Aerial Image; (b) Label Image. Black and red pixels mark non-building and building, respectively. The images used in this figure are sourced from the INRIA dataset, and the dataset can be accessed at: https://project.inria.fr/aerialimagelabeling/.

The WHU Building Dataset, developed by Wuhan University5consists of building samples extracted manually from aerial and satellite images. It encompasses a land area of about 450 square kilometers in Christchurch, New Zealand. This dataset comprises 8189 images sized at 512 × 512 pixels with a spatial resolution of 0.3 m. It is partitioned into training, validation, and test sets, with 4736, 1036, and 2416 images, respectively. Fig. 7 displays the original images alongside their associated labels.

Image and label example selected from the WHU dataset: (a) Aerial Image; (b) Label Image. Black and red pixels mark non-building and building, respectively. The images used in this figure are sourced from the WHU dataset, and the dataset can be accessed at: http://gpcv.whu.edu.cn/data/building_dataset.html.

Data processing

To improve the model’s performance, this study requires a larger dataset to help it recognize a wider range of features for better decision-making. Data augmentation, which creates new data from existing samples, is an effective method for enhancing model accuracy and reducing overfitting.

In this experiment, each HRS image in the dataset is divided into multiple 512 × 512 segments due to the high resolution of the images. These segmented images are then randomly horizontally flipped with a 50% probability when loaded into the Dataloader. It’s important to note that the SegTDformer model needs single-channel labels, while the dataset labels are in the form of RGB three-channel images. In this study, each pixel’s gray value of 255 is assigned a value of 1, and any other gray value is assigned a value of 0. As a result, pixels with a mask value of 1 in the dataset represent buildings, while pixels with a mask value of 0 indicate background areas.

Experimental settings

The building segmentation experiments were conducted using the PyTorch deep learning framework, Version 1.9.0. The experiments ran on a computer server equipped with two NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 (12GB) GPUs to accelerate computation.

The training used the AdamW optimization function with an initial learning rate of 0.00006, and weight decay was employed to aid convergence and prevent overfitting. Each dataset underwent 40,000 iterations of training due to the significant computational load associated with segmented images based on transformers. A batch size of 2 was set to accommodate the GPU configuration. Analysis of the training progress over 40,000 iterations for the three datasets revealed a gradual increase in overall accuracy and a progressive decrease in loss, with localized fluctuations observed within a small range.

This comparative study will evaluate the accuracy of the models using five assessment criteria: Overall Accuracy (OA), Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Intersection over Union (IoU). OA measures the ratio of correctly classified pixels to the total number of tested pixels. Precision is the percentage of correctly predicted positive samples out of all samples predicted as positive by the model. Recall is the percentage of all samples with positive true labels that were correctly predicted. F1-score is a metric that balances the Precision and Recall. IoU measures the ratio of the intersection and union of the true and predicted values. Typically, IoU is calculated for individual classes, and the IoU for each class is aggregated and then averaged to provide an overall assessment.

where TP is the number of true positives, TN is the number of true negatives, FP is the number of false positives, and FN is the number of false negatives.

Results

In order to thoroughly evaluate the performance of the model proposed in this study, we will conduct experiments on multiple datasets. These datasets are of various learning difficulty levels, ensuring the broad applicability of the results. Simultaneously, we have selected several currently leading models as benchmarks for comparison, including both some classic models and some of the latest models. The experiment design aims to comprehensively measure the accuracy and robustness of the model through multiple metrics.

Experimental results on the Massachusetts dataset

The extraction results of various models on the Massachusetts dataset are illustrated in Fig. 8. The dataset features densely packed and irregular buildings, with numerous obstructions around them, posing substantial challenges to model learning and making extraction particularly difficult. As shown in Fig. 8, classical models (e.g., DeepLabV3 + and HRNet) perform poorly on this challenging dataset, with uneven segmentation and large misclassification at the building edges, whereas the newly proposed models show a significant improvement compared to them. Due to the presence of attention fusion mechanisms, SegTDformer demonstrates better discrimination capability, especially in complex environments with occluded buildings. When compared to other models, SegTDformer provides more complete extraction of buildings. TDNet, DSymFuser, Sparsefoemer and Segforemer all exhibit varying degrees of missed detection within the interior areas of the buildings extracted.

Building extraction results of each method in Massachusetts dataset: The green, red, blue, and black pixels of the maps represent the predictions of true positive, false positive, false negative, and true negative, respectively. The images used in this figure are sourced from the Massachusetts dataset, and the dataset can be accessed at: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~vmnih/data/. Images were generated by Python software [version number 3.10, URL: https://www.python.org/downloads/].

The performance metrics for each model are presented in Table 2. The SegTDformer model shows comprehensive and balanced performance advantages. Its overall accuracy (OA) reaches 94.61%, which ranks first among the compared models, and improves 0.13% points over the next best SparseFormer (94.48%), the effectiveness of DAA module in multi-scale feature fusion. The module significantly improves the semantic understanding of the model by enhancing the weights of key information and suppressing misinformation. Particularly outstanding is the model’s Recall metric, which breaks the highest record of the compared models with 83.63%, an improvement of 0.74% over SparseFormer (82.89%), reducing the leakage rate of buildings, which is crucial for the complete extraction of complex targets in remote sensing scenes. In terms of comprehensive performance indicators, SegTDformer’s F1-score (84.74%) and mIoU (75.47%) are firmly at the top of the list. Among them, mIoU is improved by 0.43% compared to SparseFormer (75.04%), and compared to the benchmark model TDNet, SegTDformer surpasses comprehensively in OA, F1 and mIoU. Meanwhile, its significant improvement in OA and mIoU compared to the Transformer class model Segformer highlights the advantages of the dynamic feature screening mechanism over traditional self-attention. Although SparseFormer maintains a slight lead in Precision, SegTDformer achieves better overall performance with higher Recall and mIoU. SegTDformer achieves the current state-of-the-art building extraction accuracy at a controllable computational cost through its original attention mechanism and feature fusion strategy.

Experimental results on the INRIA dataset

Compared to the Massachusetts dataset, training on the INRIA dataset presents a slightly reduced difficulty; however, the presence of buildings with non-uniform contour shapes still affects the model’s segmentation precision. Figure 9 displays the segmentation results of various models on the INRIA dataset. The results show that DeepLabV3 + and HRNet perform moderately, experiencing instances of missed classification within large buildings. More complex CNN models (HRNet, TDNet) and Transformer models (Segformer, SparseFormer, SegTDformer) tend to produce more complete segmentation of large buildings, likely due to both types of models considering the association between local appearances and global information. The model we propose not only excels in the integrity of building interiors but also provides a better match to the actual contours in the segmentation of buildings with complex shapes compared to other models.

Building extraction results of each method in INRIA dataset. The images used in this figure are sourced from the INRIA dataset, and the dataset can be accessed at: https://project.inria.fr/aerialimagelabeling/. Images were generated by Python software [version number 3.10, URL: https://www.python.org/downloads/].

As shown in Table 3, the OA of SegTDformer ranks first with 95.39%, an improvement of 0.27% over the best-in-class SparseFormer (95.12%), which verifies the robustness of the model architecture. On mIoU, the core metric of segmentation quality, SegTDformer sets a new record with 82.54%, a 0.45% improvement over the next best DSymFuser (82.09%). Although its Precision (91.54%) is slightly lower than that of Segformer (91.89%) and TDNet (91.62%), it is still better than SparseFormer (91.35%) and on par with GDGNet (91.56%), reflecting the precise control of Precision-Recall balance in the design. This balance is even more pronounced in the comparison of HRNet: although HRNet has the highest Precision (89.62%), it lags behind F1-score (88.83%) and mIoU (80.85%) due to low Recall. In addition, compared to the Transformer benchmark Segformer, SegTDformer has an F1 advantage of 0.6% and an mIoU advantage of 1.1%, confirming that the dynamic feature screening mechanism outperforms the standard self-attentive structure. Reflecting the coordinated reliability of the SegTDformer metrics.

Experimental results on the WHU dataset

The WHU dataset features buildings that are more scattered in distribution, with uniform shapes and no large structures, and is devoid of obstructions, providing a rather simplistic environment. Hence, this dataset presents a relatively low training difficulty. As illustrated in Fig. 10, classic CNN models such as DeepLabV3+, TDNet, and HRNet all exhibit commendable performance, while emerging models like Segformer, TDNet, and SegTDformer demonstrate more precise edge detail processing. Notably, SegTDformer performs well in detecting small buildings, a task where other models tend to exhibit missed classifications.

Building extraction results of each method in WHU dataset. The images used in this figure are sourced from the WHU dataset, and the dataset can be accessed at: http://gpcv.whu.edu.cn/data/building_dataset.html. Images were generated by Python software [version number 3.10, URL: https://www.python.org/downloads/].

As demonstrated in Table 4, under the high-precision benchmark of WHU dataset, SegTDformer still shows significant advantages, with its OA (98.51%), F1 (96.21%) and mIoU (92.85%) at the top of the list: the OA improves by 0.12% compared with that of TDNet (98.39%), and the mIoU surpasses that of SparseFormer (92.27%) by 0.58%, for the first time, the core metrics achieved the overall lead. The model verifies the ability of dynamic void attention to capture complex building edges with Recall of 95.9% (0.58% improvement over TDNet), and at the same time sets a new record with Precision of 96.52% (better than SparseFormer’s 96.11%), reaching a Precision-Recall double breakthrough on high-end datasets for the first time. Especially critical is that SegTDformer becomes the only model whose F1 breaks through 96%, and the mIoU increase highlights the optimization effect of the triple-attention mechanism on boundary details, confirming its robustness and generalization ability in ultra-high precision scenarios.

Discussion

Ablation study

To systematically validate the contribution of each proposed module, we conducted an in-depth ablation study on the Massachusetts dataset with comprehensive quantitative and qualitative analyses. As quantitatively demonstrated in Table 5, the progressive integration of our novel components reveals their synergistic effects: the DAA module alone contributes a 0.8% mIoU improvement by establishing adaptive feature fusion pathways between global contexts and local details. This enhancement stems from its dual-branch architecture: the Shift Operation branch preserves fine-grained spatial patterns through controlled feature shifting, while the parallel Self-Attention branch captures long-range dependencies, with their dynamic weight coupling mechanism enabling context-aware feature recombination. Further analysis shows that the TA augmentation brings an additional 0.5% performance gain by implementing cross-dimensional interaction gates. Through its lightweight channel-spatial co-attention mechanism combined with depth-wise separable convolutions, TA effectively suppresses feature conflicts between scales while maintaining computational efficiency.

As shown in Fig. 11, qualitative comparisons further reveal that the baseline model tends to produce fragmented predictions around building boundaries, whereas our full model demonstrates remarkable improvements in capturing structural details and maintaining topological consistency, particularly for large-area buildings with complex shapes. These visual evidences align with our quantitative metrics, jointly validating that the proposed modules effectively address the information degradation problem in hierarchical feature encoding through their collaborative multi-scale modeling framework.

Visualization and analysis of ablation experiments. The images used in this figure are sourced from the Massachusetts dataset, and the dataset can be accessed at: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~vmnih/data/. Images were generated by Python software [version number 3.10, URL: https://www.python.org/downloads/].

Total parameters of different networks

The applicability of a model is not solely reflected in the enhancement of its precision. Parameters and computational cost are equally crucial metrics for evaluating a model. Nowadays, the trend towards lightweight models is also a significant aspect of model improvement. Table 6 presents the complexity of various models when training images of 512 × 512 resolution. Both TDNet and SegTDformer lead in terms of precision, yet the parameters and calculations of SegTDformer are substantially lower than those of TDNet. SegTDformer achieves the highest segmentation precision with relatively fewer parameters and computational requirements, primarily due to the integration of the parameter-free TA attention mechanism and DSC, effectively fulfilling critical functions with a minimal number of parameters.

Generalization ability of SegTDformer

The generalization ability of the model indicates whether a well-trained model is effective only on specific types of images on which it was trained. An experiment was conducted to test the segmentation precision of models trained on the Massachusetts dataset applied to the test set of the INRIA dataset. According to Table 7, the precision of SegTDformer on the INRIA test set reached 72.4%, which is 8.14% and 7.27% higher in mIoU compared to the TDNet, Segformer, and other models, respectively. Given that the two datasets differ in shape characteristics and building density, the experimental data demonstrate that SegTDformer’s generalization ability is significantly superior to other models.

Conclusion

In this study, we proposed a novel model named SegTDformer, which leveraged an attention mechanism and atrous convolution to construct DAA feature fusion module, enhancing the model’s ability to interact with multi-level information. The integration of the Shift Operation and the Self-Attention has effectively improved the model’s capability to capture information and the correlation of edge information in HRS images. In addition, the SegTDformer model integrated the TA attention mechanism with DSC, highlighting the key information of low-level features while achieving the goal of optimizing computational efficiency. The SegTDformer model’s performance was evaluated across three different datasets: Massachusetts, INRIA, and WHU. In these evaluations, it consistently outperformed existing models. Remarkably, within the Massachusetts dataset, the SegTDformer model secured superior metrics, achieving an mIoU of 75.47%, an F1-score of 84.7%, and an OA of 94.61%, eclipsing the benchmarks set by its counterparts. These outcomes attest to the efficacy of the SegTDformer model.

This study demonstrates the great potential of deep learning techniques in analyzing HRS images and extracting architectural information. Although the SegTDformer model has achieved remarkable results, future work can explore more feature fusion methods and attention mechanisms to further improve the performance and adaptability of the model. In addition, we also plan to use multiple modal features to jointly express building information and realize to achieve complementary information.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the [WHU building datasets] repository, [http://gpcv.whu.edu.cn/data/building_dataset.html]; [Massachusetts Buildings Dataset], [https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~vmnih/data/] and [INRIA Buildings Dataset], [https://project.inria.fr/aerialimagelabeling/].

References

Liu, Y. et al. Automatic Building extraction on High-Resolution remote sensing imagery using deep convolutional Encoder-Decoder with Spatial pyramid pooling. IEEE Access. 7, 128774–128786 (2019).

Rathore, M. M., Ahmad, A., Paul, A. & Rho, S. Urban planning and Building smart cities based on the internet of things using big data analytics. Comput. Netw. 101, 63–80 (2016).

Xu, S. et al. Automatic Building rooftop extraction from aerial images via hierarchical RGB-D priors. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 56, 7369–7387 (2018).

Zheng, Z., Zhong, Y., Wang, J., Ma, A. & Zhang, L. Building damage assessment for rapid disaster response with a deep object-based semantic change detection framework: from natural disasters to man-made disasters. Remote Sens. Environ. 265, 112636 (2021).

Ji, S., Wei, S. & Lu, M. Fully convolutional networks for multisource Building extraction from an open aerial and satellite imagery data set. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 57, 574–586 (2019).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. Preprint at (2015). http://arxiv.org/abs/1505.04597.

Chen, L. C. et al. Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs. Preprint at (2017). http://arxiv.org/abs/1606.00915.

He, X. et al. Swin transformer embedding UNet for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–15 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Adaptive effective receptive field Convolution for semantic segmentation of VHR remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 59, 3532–3546 (2021).

Zhao, W., Zhao, Z., Xu, M., Ding, Y. & Gong, J. Differential multimodal fusion algorithm for remote sensing object detection through multi-branch feature extraction. Expert Syst. Appl. 265, 125826 (2025).

Zheng, K. et al. Enhancing remote sensing semantic segmentation accuracy and efficiency through transformer and knowledge distillation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ Remote Sens. 18, 4074–4092 (2025).

Lu, W., Chen, S. B., Tang, J., Ding, C. H. Q. & Luo, B. A robust feature downsampling module for Remote-Sensing visual tasks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–12 (2023).

He, X., Zhou, Y., Liu, B., Zhao, J. & Yao, R. Remote sensing image semantic segmentation via class-guided structural interaction and boundary perception. Expert Syst. Appl. 252, 124019 (2024).

Tang, K. et al. The ClearSCD model: comprehensively leveraging semantics and change relationships for semantic change detection in high Spatial resolution remote sensing imagery. ISPRS J. Photogrammetry Remote Sens. 211, 299–317 (2024).

Hu, J., Shen, L., Albanie, S., Sun, G. & Wu, E. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. Preprint at (2019). http://arxiv.org/abs/1709.01507.

Hu, J., Shen, L., Albanie, S., Sun, G. & Vedaldi, A. Gather-Excite: Exploiting Feature Context in Convolutional Neural Networks.

Li, X., Wang, W., Hu, X. & Yang, J. Selective Kernel Networks. in IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 510–519 (IEEE, Long Beach, CA, USA, 2019). 510–519 (IEEE, Long Beach, CA, USA, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2019.00060 (2019).

Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J. Y. & Kweon, I. S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. Preprint at (2018). http://arxiv.org/abs/1807.06521.

Merikhipour, M., Khanmohammadidoustani, S. & Abbasi, M. Transportation mode detection through Spatial attention-based transductive long short-term memory and off-policy feature selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 267, 126196 (2025).

Wang, X., Girshick, R., Gupta, A. & He, K. Non-local Neural Networks. in IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 7794–7803 (IEEE, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018). 7794–7803 (IEEE, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018). (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00813.

Cao, Y. et al. Non-Local Networks Meet Squeeze-Excitation Networks and Beyond. In IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW) 1971–1980 (IEEE, Seoul, Korea (South), 2019). 1971–1980 (IEEE, Seoul, Korea (South), 2019). (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCVW.2019.00246.

Fu, J. et al. Dual Attention Network for Scene Segmentation. Preprint at (2019). http://arxiv.org/abs/1809.02983.

Yuan, Y., Chen, X., Chen, X. & Wang, J. Segmentation Transformer: Object-Contextual Representations for Semantic Segmentation. Preprint at (2021). http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11065.

Li, X. et al. A frequency decoupling network for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 63, 1–21 (2025).

Cui, J. et al. Multiscale Cross-Modal knowledge transfer network for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 63, 1–15 (2025).

Misra, D., Nalamada, T., Arasanipalai, A. U. & Hou, Q. Rotate to Attend: Convolutional Triplet Attention Module. Preprint at (2020). http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.03045.

Yang, L., Zhang, R. Y., Li, L. & Xie, X. SimAM: A Simple, Parameter-Free Attention Module for Convolutional Neural Networks.

Pan, X. et al. On the Integration of Self-Attention and Convolution.

Lu, W., Chen, S. B., Ding, C. H. Q., Tang, J. & Luo, B. LWGANet: A Lightweight Group Attention Backbone for Remote Sensing Visual Tasks. Preprint at (2025). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.10040.

Lu, W., Chen, S. B., Shu, Q. L., Tang, J. & Luo, B. DecoupleNet: A lightweight backbone network with efficient feature decoupling for remote sensing visual tasks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–13 (2024).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. Preprint at (2021). http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.11929.

Carion, N. et al. End-to-End object detection with Transformers. in Computer Vision – ECCV 2020 (eds Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T. & Frahm, J. M.) vol. 12346 213–229 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. Preprint at (2021). http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.14030.

Xie, E. et al. SegFormer: Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. Preprint at (2021). http://arxiv.org/abs/2105.15203.

Feng, H. et al. FTransDeepLab: multimodal fusion Transformer-Based DeepLabv3 + for remote sensing semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 63, 1–18 (2025).

Chang, H. et al. Deep symmetric fusion transformer for multimodal remote sensing data classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–15 (2024).

Zhao, H., Shi, J., Qi, X., Wang, X. & Jia, J. Pyramid Scene Parsing Network. Preprint at (2016). https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1612.01105.

Maggiori, E., Tarabalka, Y., Charpiat, G. & Alliez, P. High-Resolution semantic labeling with convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 55, 7092–7103 (2017).

Wang, Y., Zeng, X., Liao, X. & Zhuang, D. B-FGC-Net: A Building extraction network from high resolution remote sensing imagery. Remote Sens. 14, 269 (2022).

Zhang, F., Yang, G., Sun, J., Wan, W. & Zhang, K. Triple disentangled network with dual attention for remote sensing image fusion. Expert Syst. Appl. 245, 123093 (2024).

Wang, K., Zhang, X., Wang, X. & Yu, L. Gradient decoupling guided network for High-Resolution remote sensing segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 63, 1–18 (2025).

Chen, Y. et al. SparseFormer: A credible Dual-CNN Expert-Guided transformer for remote sensing image segmentation with sparse point annotation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 63, 1–16 (2025).

Wang, Z., Wang, B., Zhang, C., Liu, Y. & Guo, J. Defending against poisoning attacks in aerial image semantic segmentation with robust invariant feature enhancement. Remote Sens. 15, 3157 (2023).

Wang, Z., Wang, B., Zhang, C. & Liu, Y. Defense against adversarial patch attacks for aerial image semantic segmentation by robust feature extraction. Remote Sens. 15, 1690 (2023).

Pan, D., Zhang, M., Zhang, B. A. & Generic FCN-Based approach for the Road-Network extraction from VHR remote sensing Images – Using openstreetmap as benchmarks. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 14, 2662–2673 (2021).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778 (IEEE, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016). 770–778 (IEEE, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 (2016).

Xie, S., Girshick, R., Dollár, P., Tu, Z. & He, K. Aggregated Residual Transformations for Deep Neural Networks. Preprint at (2017). http://arxiv.org/abs/1611.05431.

Liu, Y. et al. ARC-Net: an efficient network for Building extraction from High-Resolution aerial images. IEEE Access. 8, 154997–155010 (2020).

Sun, K., Xiao, B., Liu, D. & Wang, J. Deep High-Resolution Representation Learning for Human Pose Estimation. Preprint at (2019). http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.09212.

Chen, J. et al. DASNet: dual attentive fully convolutional Siamese networks for change detection in High-Resolution satellite images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 14, 1194–1206 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Building extraction and floor area Estimation at the village level in rural China via a comprehensive method integrating UAV photogrammetry and the novel EDSANet. Remote Sens. 14, 5175 (2022).

Li, R., Zheng, S., Zhang, C., Duan, C. & Wang, L. A2-FPN for semantic segmentation of Fine-Resolution remotely sensed images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–13 (2022).

Iqbal, E., Safarov, S., Bang, S. & MSANet Multi-Similarity and Attention Guidance for Boosting Few-Shot Segmentation. Preprint at (2022). http://arxiv.org/abs/2206.09667.

Chen, H., Shi, Z. A. & Spatial-Temporal Attention-Based method and a new dataset for remote sensing image change detection. Remote Sens. 12, 1662 (2020).

Zhao, Q., Liu, J., Li, Y. & Zhang, H. Semantic segmentation with attention mechanism for remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–13 (2022).

Li, R., Zheng, S., Duan, C., Su, J. & Zhang, C. Multistage attention ResU-Net for semantic segmentation of Fine-Resolution remote sensing images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 19, 1–5 (2022).

Zhang, C., Wang, L., Cheng, S., Li, Y. & SwinSUNet Pure transformer network for remote sensing image change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–13 (2022).

Wu, H., Huang, P., Zhang, M., Tang, W. & Yu, X. CMTFNet: CNN and multiscale transformer fusion network for Remote-Sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–12 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Huang, X., Yang, X., Peng, J. & Ban, Y. D. C. T. N. Dual-Branch convolutional transformer network with efficient interactive Self-Attention for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–16 (2024).

Sun, L., Zhao, G., Zheng, Y. & Wu, Z. Spectral–Spatial feature tokenization transformer for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–14 (2022).

Li, J. et al. PCViT: A pyramid convolutional vision transformer detector for object detection in Remote-Sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–15 (2024).

Dang, L., Pang, P. & Lee, J. Depth-Wise separable Convolution neural network with residual connection for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 12, 3408 (2020).

Mnih, V. Machine Learning for Aerial Image Labeling.

Maggiori, E., Tarabalka, Y., Charpiat, G. & Alliez, P. Can semantic labeling methods generalize to any city? the inria aerial image labeling benchmark. In IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS) 3226–3229 (IEEE, Fort Worth, TX, 2017). 3226–3229 (IEEE, Fort Worth, TX, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS.2017.8127684 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 42201077]; the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation [grant number ZR2024QD279 and ZR2021QD074]; the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [grant number 2023M732105]; the Youth Innovation Team Project of Higher School in Shandong Province, China [grant number 2024KJH087]; the State Key Laboratory of Precision Geodesy, Innovation Academy for Precision Measurement Science and Technology, CAS [grant number SKLGED2024-3-4].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L.; Conceptualization, Methodology, Software; S.Z.: Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft; X.W.: Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft; R.Z.: Visualization, Investigation; J.H.: Resources; L.K.: Supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Zhang, S., Wang, X. et al. Dynamic atrous attention and dual branch context fusion for cross scale Building segmentation in high resolution remote sensing imagery. Sci Rep 15, 30800 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14751-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14751-0