Abstract

Large language models (LLMs) are the engines behind generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications, the most well-known being chatbots. As conversational agents, they—much like the humans on whose data they are trained—exhibit social bias. The nature of social bias is that it unfairly represents one group over another. Explicit bias has been observed in LLMs in the form of racial and gender bias, but we know little about less visible implicit forms of social bias. Highly prevalent in society, implicit human bias is hard to mitigate due to a well-replicated phenomenon known as introspection illusion. This describes a strong propensity to underestimate biases in oneself and overestimate them in others—a form of ‘bias blind spot’. In a series of studies with LLMs and humans, we measured variance in perception of others inherent in bias blind spot in order to determine if it was socially stratified, comparing ratings between LLMs and humans. We also assessed whether human bias blind spot extended to perceptions of LLMs. Results revealed perception of others to be socially stratified, such that those with lower educational, financial, and social status were perceived more negatively. This biased ‘perception’ was significantly more evident in the ratings of LLMs than of humans. Furthermore, we found evidence that humans were more blind to the likelihood of this bias in AI than in themselves. We discuss these findings in relation to AI, and how pursuing its responsible deployment requires contending with our own—as well as our technology’s—bias blind spots.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Western culture is trying hard to understand both itself and its technologies. Today, we are more psychologically aware than any generation before us1, with concepts such as neurodiversity, prejudice, and the nature of subjectivity a regular feature of many school curricula2,3,4. And yet, when it comes to our technology, we stand amidst the latest wave of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools and appear shocked when these applications provide incorrect and biased outcomes. A report published by UNESCO, for instance, ran with the headline ‘Generative AI: UNESCO study reveals alarming evidence of regressive gender stereotypes’5.

This blind spot is predictable. It represents a well-known human phenomenon called ‘introspection illusion’6,7. Studied for decades, introspection illusion—or Bias Blind Spot (BBS) as it is more commonly known—describes a propensity for individuals to believe they are correct, objective, and ‘clear-headed’, and that everyone else is (sadly) not. The surprise observed in media headlines when our AI technologies reveal their imperfections8,9 might suggest we categorise our technology as ‘like us’ and therefore immune to what we perceive to be the typical cognitive and motivational failings of others, a proposition aligned with existing knowledge of other cognitive heuristics such as the automation bias90,91.

As AI technologies permeate society more deeply, finding their way into our classrooms, offices, and courtrooms, we need to use what we already know about human bias to better assess, understand, and deal with the goal that we have set ourselves, which is to design and deploy fair, equitable, and responsible AI10,11,12,13,14,15. This is particularly necessary when considering the types of cognitive heuristics that we know exist, particularly those that include social bias. Hoping to contribute to the field of Responsible AI (RAI), we report on several studies aiming to shed light on this socio-technical form of BBS. Using a novel measure capturing variance in perception of others, we analysed data from both humans and some of today’s most widely disseminated and deployed Large Language Models (LLMs). In so doing, we were able to (1) assess whether the BBS phenomenon extends to technology, (2) quantify social stratifications in perception of others as a proxy for implicit social bias and in so doing compare levels of bias between humans and AI, and (3), by reverse-engineering variance in perception, shed light on the human dimensions most aligned with the bias profile of well-known generative AI applications.

Background

The rise of generative AI

LLMs are a type of machine learning model (a form of AI) that can perform Natural Language Processing (NLP)16. Through deep neural network training, they can process incoming information as well as generate outputs in the form of human-like dialogue, still or moving images, music, or other digital content17. LLMs are now widely used to power generative AI chatbots, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini. These tools are today available free of charge to anyone with a digital device and internet access. They currently function in the form of humanised ‘assistants’ with which you can chat, either though text or voice. Their ability to respond in a manner that is uncannily human has prompted impassioned debates on the nature of consciousness18,19. Wherever one’s stance on this debate lands, there is now ample evidence that at the very least, most currently available generative AI applications can surpass Turing-type tests of ‘humanness’20 as well as classic Theory of Mind tasks, including the successful interpretation of socially ambiguous situations21.

For this reason and more, the popularity and uptake of these AI tools is growing. 18% of adults in the US say they now use applications like ChatGPT22, and this figure jumps to 32% for people with a college degree23. Of the people using this technology, 20% say they use it for entertainment, 19% for learning, and 16% to assist them with organisational tasks such as summarising information. Another survey conducted with over 31,000 knowledge workers from 31 countries reported that 75% of people were using generative AI to help them with their jobs24. When it comes to the use of LLMs in student populations, these figures go even higher. A report from the Digital Education Council showed that 86% of tertiary students are using AI tools to assist them with their learning25, and in Australia, a Youth Insight analysis reported that 70% of 14 to 17-year-olds using generative AI for purposes such as information sourcing, assignment writing, and general learning26. These tools are also impacting health services. In a survey of 1,000 general medical practitioners in the UK, 20% reported using tools such as ChatGPT for notetaking and diagnostics27.

Given society’s voracious appetite for generative AI, its commercialisation is moving fast. In the last 12 months, optics have shifted towards talk of ‘pocket assistants’ and ‘personal intelligences’28, whilst transforming into ‘co-pilots’ or ‘autonomous agents’ once at the office. These models are also quickly being integrated into the Internet of Things (IoT), aiming to create helpful and fluid interactive experiences, such as talking fridges that update your shopping cart, or automated vehicles that pre-empt navigation needs29. As a result, Bloomberg report that generative AI will become a $1.3 trillion market by 203230.

Despite this wave of AI enthusiasm and investment, significant societal concerns have been raised. These range from practical issues of intellectual property rights, plagiarism, misinformation, and job loss, to more existential fears of humanity being usurped by forms of AI we can no longer control31,32. Underscoring these fears are pragmatic questions about the data used to train these AI systems—its sovereignty, ethical management, and quality control33,34,35. Interestingly, this issue of ‘garbage in garbage out’ is not new, reflected as it is in the words of Charles Babbage from the late 1800s; “On two occasions I have been asked, “Pray, Mr. Babbage, if you put into the machine wrong figures, will the right answers come out?”. I am not able rightly to apprehend the kind of confusion of ideas that could provoke such a question”36. Thanks to these ongoing debates, it is now more commonly known that decisions made regarding how the data is treated, trained, and tested have a direct impact on the quality of a LLM’s output.

The quality of generative AI’s outputs

The highly successful anthropomorphisation of generative AI tools comes about through an intense training process comprised of an initial stage of automated learning using hundreds of GBs of human-generated text (300 billion words)37. This is followed by a reinforcement training stage involving human-led corrections38. The result of this expensive and time-consuming process is that generative AI tools can respond to questions—or prompts as they are known—in an impressively comprehensive fashion, providing users with an array of useful and engaging material, from travel advice to educational support, communication assistance to companionship.

Despite the intensity of training, however, these tools can and do (at times) respond inappropriately, displaying anything from biased outputs to entirely fallacious information39. To date, the spotlight has been on headline-grabbing hallucinations, such as ChatGPT’s infamous line ‘the world record for crossing the English Channel entirely on foot is held by.’40, as well as on forms of racial, ethnic, religious, and gender bias. Evidence of racial bias in generative AI’s outputs has been demonstrated in various different guises, whether portraying Muslim people as violent, or Jewish people as overly concerned with money41. Studies looking into gender bias have demonstrated how generative AI applications ranked women as less intelligent42 and men as more ‘leaderful’43. Concerns over such gender stereotyping have prompted the assistant director-general at the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization to comment that “these systems replicate patterns of gender bias in ways that can exacerbate the current gender divide”44.

Acknowledging that bias is often inherent in the data itself (in other words the AI output may be ‘correct’ given the material it is trained on), technologists have lent on reinforcement training and algorithmic adjustments to recalibrate outputs. For instance, Google’s image generation LLM was algorithmically adjusted in an attempt to increase ethnic and gender diversity when responding to image prompts (this backfired however, when the tool presented historically inaccurate visual depictions of, for example, female popes or Black Vikings45. Further, processes such as ‘adversarial debiasing’—which involves two machine learning models working together to identify and eradicate bias—are also under development46,47. What this means, however, is that training requires on-going sources of end-user data, meaning that the models are permanently ‘under development’48,49,50.

Given the penetration of LLMs into classrooms, homes, and workplaces, the need for reliable and trustworthy information is at odds with the in progress nature of these tools. Indeed, the requirement for reliable, validated and non-biased information becomes non-negotiable when they are used for tasks such as hiring recommendations or partnering advice on dating apps51,52,53. Whilst it is currently possible to successfully filter out overt forms of bias, the insidious nature of more implicit forms of social bias still urgently need attention. Building effective solutions requires not only an understanding of the skewed distribution of the training data54,55, but also insight into the existence and nature of implicit human social bias as well as reliable methods of detecting such biases once they are projected into LLMs.

Theoretical framework

Implicit social bias in humans

In order to quickly navigate our complex worlds, humans invariably rely on cognitive heuristics—a type of mental short-cut that allows people to form judgements and make decisions quickly56. Social biases are a form of cognitive heuristic, and the boundary between them is often blurred. For instance, when perceiving the world, familiarity or personal saliency of information will lend itself to unconscious ‘rule of thumb’ thinking. As most learned information comes tagged with social values, cognitive heuristics often incorporate, if not lean on, societal norms, and these are likely to include various forms of socially biased information57.

Implicit social biases describe patterns of unconscious automatic thinking that follow socially discriminatory lines58. Studied extensively in psychological research, implicit social biases were originally thought to be stable and representing a form of individual difference59. Theories of implicit bias acknowledge that situations could influence the accessibility of specific thinking patterns but largely state that bias is underwritten by an individual’s learning history. This has been challenged recently, with research looking more closely at the significant role of social context in bias perpetuation60. For instance, Payne and Hannay suggest that the accessibility of social cues can be a dominant driver of implicit bias and point to data demonstrating links between individual levels of implicit bias and systemic levels of societal racism61. Models of implicit bias expand on this62. They show the presence of two contextual factors influencing bias. The first represents accessibility, in other words, if the social situation presents cues that are aligned with a social bias then this will both activate and reinforce the existence of the bias. The second factor represents inhibition and involves conscious and socially triggered reminders of the unacceptable nature of bias and the need to suppress it.

Significant effort has been exerted on measuring implicit bias. The most well-used form of measurement has been the Implicit Association Test (IAT)63,64, used extensively in research from emotions to goal setting. However, despite the test’s popularity, its usefulness as a tool has come to be questioned, primarily because of poor test-retest reliability65, meaning that the same individual can show different results from one sitting to another. Further, a range of studies have demonstrated a lack of evidence of a relationship between IAT scores and behaviour66,67,68. This lack of measurement reliability and validity has meant that interventions to reduce implicit bias are challenged.

Whether for reasons of methodological complexity or the challenging nature of implicit bias itself, many interventions to reduce implicit social bias have been trialled, but few have shown success. For instance, Lai and colleagues tested nine undergraduate interventions designed to reduce racial bias, and with a total of over 6,000 participants. Although all nine interventions did succeed in immediately reducing bias, few were effective after a short delay, and after several days all evidence of reduced bias had disappeared69. Reasons for the tenacity of implicit bias is an ongoing subject of debate. Aside from difficulties in measurement, scholars point to the entrenched nature of social motives as well as to the accessibility of social cues59,70,71. However, an alternative hypothesis has been put forward. Scholars have noted the existence of a blind spot when it comes to an understanding of ourselves and our own biases.

Bias blind spot (BBS)

Bias Blind Spot describes the capacity for humans to believe they are not biased (or at least, not as biased as everyone else). This ‘meta-bias’ is thought to represent a form of naïve realism shaped by the egocentric nature of cognition. Considered from an evolutionary perspective, BBS describes a person’s “unwavering confidence that their perceptions directly reflect what is out there in ‘objective reality’” [p.404, 72], thus boosting both self and collective esteem. This well replicated psychological phenomenon is shown to be increased for social biases and is particularly activated in situations of social conflict73,74. It has been reliably demonstrated across the world, in populations from North America, China, Japan, the Middle East, and Europe72 and shown to have no association with cognitive ability, style, or deliberation75,76.

The cost of BBS for societal equity is high. A person’s inability to acknowledge their own biases likely stands in the way of interventions designed to reduce social prejudice77. Scholars studying BBS comment that its negative impact extends beyond merely hindering self-knowledge and fuelling conflict73, but has a measurable role to play when it comes to polarising societal outcomes, whether through financial inequities, medical error, or political division72. Furthermore, these biases underpin social discrimination, the systemic nature of which has been demonstrated in contexts as broad as clinical decision-making78, educational assessments79, and judicial process80. Monetising racial discrimination alone, data from Australia quantified the cost of contending with the health outcomes for victims of discrimination to be in the order of 3% of the annual domestic product (GDP)81.

As per models of implicit bias, in which learning history interact with cues embedded in our social contexts, there are two sides to understanding BBS. The first involves assessing whether there is variance in who is more susceptible to BBS and relates to a person’s learning history, and here data has shown only minor variance82,83. The second aspect of BBS relates to social context, and particularly to variance in an individual’s perception of the ‘other’ about which they are making a judgement. This dimension of BBS has to date received little attention. Traditionally, studies have been conducted in which people are asked to compare the level of bias exhibited by ‘an average citizen’ to the self. Within the complex world of social perception, however, there is no such thing as an average ‘other’ person, and so it is unlikely that perceived bias of different others would be consistent. Indeed, scholars of social perception comment “...people are likely to have multiple and conflicting motivations when processing information such that not all of them can be fully satisfied. Accuracy would then have to be sacrificed to some extent in order that other motivations (e.g. self-esteem maintenance; interpersonal goals) receive some satisfaction” [p.414, 84]. Some experimental research has shed light on this. Investigating differences in belief, one study manipulated congruency of opinion to reveal how BBS increased when the other was seen to hold an incongruent opinion85. Another related study used an experimental paradigm to produce the same effect when manipulating political partisanship. This study also demonstrated how this effect was mediated through feelings of affect—in other words people attributed more bias to out-group members who they did not like86.

Given that bias itself is largely perceived as a form of erroneous or lazy thinking—a type of cognitive deficit—variance in levels of BBS could therefore serve as a proxy for implicit social bias. Moreover, with evidence in place of the intransigence of learned biases but yet their reactivity to social cues, it would seem likely that perception of bias in others would fall into the category of social reactivity and thereby vary according to socially stratified perceptions84. Measuring such differences would therefore demonstrate not only a lack of self-awareness (potentially related to resistance to change) but also its own empirical quantification of implicit social bias. We note that using variance in BBS as a proxy for implicit social bias represents a novel approach but given that more traditional measures of implicit bias in humans have often failed to replicate or validate between constructs66,67,68 we consider its use justified, particularly when contending with the added difficulties of measuring ‘implicit bias’ in generative AI.

Implicit social bias in generative AI

Today, there is evidence that the LLMs driving generative AI chatbots have exhibited various forms of social bias41,42,87. For instance, data collected with a commonly used generative AI application demonstrated bias in occupational predictions along gender lines, with biases becoming more exaggerated for intersectional identities, such as for a person who was a Muslim and also a woman88. This particular research did, however, find evidence of the intended mitigation of such biases through algorithmic control mechanisms. These strategies to counter bias—often described as ‘guardrails’—were themselves studied in a more recent paper by Warr and colleagues. In this study, prompts were designed in a way to compare explicit social indicators to implicit social indicators, and in the context of assessing student assignments. Tested with a popular LLM, researchers found evidence of sustained prejudice when the social indicators were implicit, but not explicit, in other words, when the guardrails failed89. What these findings underscore is the need for more reliable measures of the potential presence of implicit processes—such as social bias—in generative AI.

Using what we know about BBS in humans can help with this. First, BBS can be used to assess where technologies such as generative AI sit in our overall perception of bias. To put more exactingly, does our blind spot—in which we overestimate the presence of bias in others and underestimate it in ourselves—include perceptions of our chatbot, and if so, do we perceive this technology to be more like ourselves (i.e., mostly free of bias), or more like ‘others’ (i.e., highly susceptible to bias)? Existing evidence from the domain of cognitive heuristics might foreshadow the answer to this question. Automation bias is a well-known cognitive heuristic showing how humans over-rely on automated information (i.e., information from machines), which they tend to rate more positively—and trust more—than information from a human source90,91.

Second, the protocols to measure BBS provide us with a novel way to operationalise the quantification of implicit bias, and of particular use when measuring LLMs. Given that the presence of bias in a person is negatively perceived—representing a type of deficient thinking—measuring differences in perceived levels of bias according to which ‘other’ is being judged provides a way to capture and quantify implicit social bias. Importantly, this protocol allows us to bypass the guardrails built into generative AI applications. For instance, if we were to ask a chatbot whether women make better childcare workers than men, AI guardrails would likely construct a response such as ‘There is no inherent reason why women make better childcare workers than men’. If we asked it to rate a man and a woman on their ability to perform well in such a role, it would likely provide the same rating for each, and with the added note ‘The same rating could apply to any man or woman who is similarly trained, compassionate, patient, and committed to childcare work’. Despite such intensive training and extensive guardrails, however, research continues to show that when using AI algorithms to support decision-making, forms of implicit gender biases are alive and well92,93.

Given the pervasive integration of generative AI within our homes, offices, and classrooms94, there is a need to empirically assess the nature of these technologies in order to ensure they are socially fit for purpose. Identifying the presence of implicit bias in these technologies is a good—and responsible—place to start. Indeed, this requirement underpins any possibility of removing such forms of social prejudice from our technologies. The urgent need to eradicate social bias in generative AI was underscored by recent research demonstrating not only the presence of social bias in our technologies, but more concerningly the cycle of bias propagation brought about by the use of these everyday tools and technologies95.

Tackling bias in AI responsibly

Responsible AI (RAI) is a term used globally to signal both the need and motivation to ensure AI is developed and deployed in ways that are inclusive, transparent, and accountable. Its foundational premise is that technology should be aligned with societal values. Given that societal norms of fairness—prescribed at levels of legal requirement, regulatory stipulation, or codes of ethical conduct96,97,98—are applicable at all levels of human experience, an ability to identify (and mitigate) implicit social bias in our AI technologies represents a foundational step in ensuring its responsible deployment99,100.

However, as much as RAI is replete with guidelines and frameworks that describe how this technology should contribute positively to all members of society101,102, when it comes to translating the principles of RAI into a measurable practice, less is known11,103. Applying research gained from studying human bias, this paper aims to find ways to assess the presence of implicit social bias in generative AI. The goal of this endeavour was both to build an evidence base to support RAI as well as to contribute meaningfully to the eradication of social bias within society. In the face of research demonstrating how hard it is to reduce implicit bias104, scholars have underscored the need to address the social environment as a means of tackling this manifestation of inequity. Generative AI technologies can—if developed and evaluated effectively—play a crucial role in achieving that goal by not only reducing the human user’s exposure to socially biased content105, but potentially also serving as an intervention by actively heightening awareness in its users of the existence of prejudicial thinking in everyday life. To do this successfully, however, we need a reliable and validated measure of social bias in LLMs, and one able to penetrate deeper than the LLM’s guardrails. It is for this reason that we chose to interrogate both humans and generative AI using a measure of BBS able to assess variance in the perception of different types of ‘others’.

The present study

In this study we set out to measure implicit social bias in LLMs, and to compare this level of bias to that of human respondents. We first evaluated evidence of bias in humans. To do this, we used an experimental protocol designed to measure BBS75 and which we adapted to assess socially stratified levels of implicit bias, specifically stratifications related to gender, age, level of education, income, country of origin, and social status. Using this same protocol, we then assessed implicit social bias in OpenAI’s ChatGPT. This allowed us both to compare levels between humans and AI, but also, by collecting the equivalent data from both we were able to analyse the profile of bias present in the LLM according to the socio-contextual differences of our human sample. In other words, to assess whether the bias present in LLMs was more aligned with the bias evident in men or women, younger or older people, or those with a higher or lower income. Finally, using the original BBS paradigm, we wanted to assess people’s perception of implicit bias in themselves, in other people, and also in generative AI tools such as ChatGPT. To help structure our exploratory analysis, we investigated the following research questions:

-

1.

Is there evidence of socially stratified BBS in humans?

-

2.

Is there evidence of socially stratified BBS in LLMs?

-

3.

How does the level of socially stratified BBS compare between humans and LLMs?

-

4.

What do the socio-contextual characteristics of human levels of BBS tell us about those of LLMs?

-

5.

Do generic (non-stratified) levels of human BBS extend to generative AI technologies?

Methods

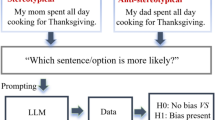

Three studies were conducted for the purposes of this research. To respond to research questions one to four, we designed two identical studies to be run with both a generative AI chatbot and human respondents. The data collection protocol for Study 1 and 2 used an adapted version of a validated measure of BBS75, in which we asked for ratings of perceived bias present in other people. In these two studies we expanded the category of ‘other person’ to include typologies of people who varied systematically on gender, age, level of education, salary, country of origin, and social status. This allowed us to investigate whether implicit bias varied according to who was being judged, and also by whom—human or AI—the judgement was being made (refer to Fig. 1 for a visual representation of this protocol). Study 3 was designed to respond to the fifth research question and involved us collecting human survey data in which we asked respondents to rate the likelihood of implicit bias being present in themselves, the ‘average person,’ and a generative AI application such as ChatGPT. In other words, we used the established BBS paradigm75 but extended it to include ratings of bias in LLMs.

To collect our human respondent data, we worked with the online crowd sourcing platform Prolific (Prolific.com). This platform advocates for participant rights—ensuring ethically sourced and human-centred data curation106. This mantra is delivered first by insisting all researchers pay their participants at least the minimum wage (and stringently monitoring and penalising researchers who underestimate participant time required) and second, by collecting comprehensive levels of socio-demographic information with which to provide reliably representative community samples.

Study 1

Participants

In Study 1 we collected data with an online sample of human respondents resident in the UK, using Prolific (N = 206). Ethical approval (#089 − 23) for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee that forms part of the Commonwealth Scientific Industrial Research Organisation (Australia’s national science agency, also known as CSIRO). All data collection was carried out in full accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This included collecting informed consent from our participants before data collection took place, as well as paying our participants for their time at a rate higher than the minimum average wage. Data was representative of a general community population. 47% of the sample were women, the average age was 42.01 (range 19 to 80). For full socio-demographic results, see Appendix 1 in Supplementary Materials.

Measures and procedure

Respondents were presented with a selection of socio-demographic questions, after which they were asked to think about and rate the presence of bias in a variety of different people. For this study, we presented seven different biases to respondents in a randomised order (see Appendix 2 in Supplementary Materials). The seven biases were: myside bias; outcome bias; diffusion of responsibility bias; framing effect bias; fundamental attribution error; ingroup bias; and self-serving bias. These biases were selected from previous research measuring BBS75,76 and were chosen to represent a range of biases implicating different aspects of human thinking: social group dynamics (myside and self-serving bias); cognitive deficits (outcome bias and framing effect bias); morality (diffusion of responsibility bias); and self-esteem (fundamental attribution effect and self-serving bias). Respondents were asked to read about the bias and to then rate the likelihood of a particular person exhibiting such a bias. To systematically assess level of BBS across different social typologies, we developed a set of social identities \(\:j=1,\:\dots\:,\:100\).

Social identities

Each identity comprised six elements: gender, age, country, education status, financial status, and social status, and from these elements we generated a sentence summarising each social identity (e.g., ‘A 23-year-old man from Belarus, with a PhD, and has no money, and who lives with their partner’). Each of the social identity elements were designed to provide an output to be used for analysis. See Appendix 3 (Table A3.1 in Supplementary Materials) for a full list of identities.

Gender was a 0–1 variable representing ‘man’ or ‘woman’. Age was a numeric variable, with a range from 18 to 86. For level of education, we constructed a 6-point scale from 0 (no education) to 5 (a PhD). For financial status, we used an 8-point scale from 0 (no money) to 7 (a very large income). And finally, for social status we used a 5-point scale from 0 (involved in illegal activities) to 4 (volunteering to help others).

For country, we used the individualism-collectivism score from the Culture Factor Country Comparison tool107. This tool is based on the Six Dimensions of National Culture, a model designed to identify ‘overarching cultural patterns’. Countries scoring high on individualism represent cultures in which social structures are loose, and people are expected to look after themselves. Countries low on individualism (high on collectivism) represent cultures with more cohesive social structures in which groups and extended families play a more dominant role108. Generally speaking, countries high on individualism are European countries, the UK, the US, and Australia, and countries low on individualism are situated in Africa, Asia, the Middle Eastern, and South America109,110,111. Higher numbers on this scale represent higher levels of individualism.

We asked respondents to provide a score ranging from 1 to 10 indicating the likelihood that each identity (as described by the summary sentence) would exhibit biased thinking. An example of the presentation of a bias and its associated question is “Imagine we are playing a game about cognitive heuristics. The rules of the game are that you have to respond with a number from 1 to 10 where 1 means barely impacted at all and 10 means extremely impacted. Let’s start with a heuristic called ‘myside bias’ which describes a tendency for people to not evaluate the evidence fairly when they already have an opinion on the issue. That is, they tend to evaluate the evidence as being more favourable to their own opinion than it actually is. When people do this, it is called ‘myside bias’. Remember, for this game, the question is how much would a person be impacted by this bias, and you have to respond with ONLY a number from 1 to 10 where 1 is barely impacted at all and 10 is extremely impacted. I will now present different people and you have to respond with a number”. For a full representation of all identities used, including their scale descriptions, associated numeric scores, and distributions, refer to Appendix 3 (Tables A3.1 and A3.2 in Supplementary Materials). In summary, we surveyed 195 human respondents, asking each respondent to provide scores for 70 identities (ten identities per bias across seven biases).

Analysis strategy

To estimate the respondents’ level of implicit bias in relation to each social identity element (age, education status etc.), we fitted a linear mixed effects model to predict the \(\:i\)th respondent’s perceived likelihood of the \(\:j\)th social identity exhibiting the \(\:h\)th bias (\(\:{S}_{ijh}\)) as a function of the social identity elements. Since each respondent provided ratings across multiple bias types, we included random intercept terms in the model for respondent ID \(\:{\mu\:}_{0j}^{\left(pid\right)}\) and bias type \(\:{\mu\:}_{0h}^{\left(bias\right)}\) to capture variation in scores across respondents and biases. This model is given by:

where \(\:I{D}_{jk}\) is the \(\:j\)th identity’s \(\:k\)th social identity variable (see Fig. 2 for these variables), \(\:{\epsilon }_{ijh}\) is the error term, \(\:{\sigma\:}_{pid}^{2}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{bias}^{2}\) are the variances of the random intercept terms for respondent ID and bias type, and \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{k}\) are regression weights to be estimated. The estimated regression weight for each social identity element \(\:{\widehat{\beta\:}}_{k}\) indicates the average effect of the element on the respondents’ perceived likelihood of the social identity exhibiting bias, controlling for the other predictors. We standardised the scores \(\:{S}_{ijh}\) before fitting this model to create a common scoring scale across the human respondents and ChatGPT, enabling comparisons of estimates from the two sources. Therefore, below we report differences in scores in terms of standard deviations (SDs).

We conducted a power analysis to determine, for each social identity predictor, the probability of our method correctly rejecting the null hypothesis that \(\:{\beta\:}_{k}=0\) when it is false. This analysis indicated that our method had high statistical power across each of these tests for moderately sized true \(\:{\beta\:}_{k}\). Further details and results are provided in Appendix 5 in Supplementary Materials.

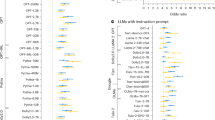

Results

Research question 1

Human respondents manifested significant levels of implicit social bias. They rated identities with lower social, financial, and education status as significantly more likely to exhibit biased thinking (see Fig. 2). Social status had the strongest effect on respondent ratings, with respondents rating individuals of low and medium social status respectively as 0.92 SDs (95% CI 0.87–0.96) and 0.20 SDs (95% CI 0.15–0.24) more likely to exhibit biased thinking than individuals of high social status. Respondents also rated individuals whose highest educational attainment was high school incompletion and completion respectively as 0.16 SDs (95% CI 0.11–0.20) and 0.11 SDs (95% CI (0.06–0.16) more likely to exhibit bias than degree-holding individuals. In terms of financial status, respondents rated individuals who had no money or received social benefits as 0.14 SDs (95% CI 0.10–0.18) more likely to exhibit bias than high income or wealthy individuals.

We found limited or no evidence of the identities’ gender, country status, and age influencing human respondents’ ratings. Respondents rated women as 0.05 SDs (95% CI 0.02–0.08) less likely to exhibit bias than men. Respondents also rated identities from more individualistic countries as marginally more likely to exhibit bias than identities from more collectivist countries, with a two-standard deviation (46 points on a 100-point scale) increase in the country’s individualism score corresponding to an 0.03 SD (95% CI 0.00-0.06) increase in respondents’ perceived likelihood of the individual exhibiting bias. There was no evidence of an association between individuals’ ages and respondents’ scores.

Study 2

Measures and procedure

We ran the above data collection protocol with Open AI’s ChatGPT, asking it to provide a score ranging from 1 to 10 indicating the likelihood that each identity would exhibit biased thinking. We ran individual data collection sessions with ChatGPT, and in each we asked it to provide scores for 70 randomly selected identities (ten identities per bias across seven biases). We ran 200 survey sessions using GPT-3.5 turbo to obtain a comparable number of responses to the survey of human respondents. We also ran 20 survey sessions using GPT-4, with the significantly higher cost of generating responses from GPT-4 preventing further data collection. The survey sessions were run between 30 May and 2 June 2025, with the models’ temperature parameter set at the (OpenAI API) default value of 1. In each session, we made a new API call to the model and provided a contextual prompt explaining the task before presenting the social identities for the model to rate (see Appendix 2 in Supplementary Materials for the prompts used to elicit responses from ChatGPT).

To test the robustness of our results, we ran additional survey sessions using ChatGPT-3.5 turbo with the temperature set to 0.5 for more deterministic responses and 1.5 for more random/creative responses. Here, we ran 200 survey sessions per temperature. Below we report the results for GPT-3.5 at a temperature of 1 (see Appendix 5 in Supplementary Material for further results across the three temperatures).

We conducted power analyses to determine, for each social identity predictor, the probability of our method correctly rejecting the null hypothesis that \(\:{\beta\:}_{k}=0\) when it is false. These analyses indicated that at a significance level of \(\:\alpha\:=0.05\), our method had high statistical power (over 80%) across each of these tests for moderately sized true \(\:{\beta\:}_{k}\) for both the data from GPT-3.5 and the smaller sample from GPT-4. Further details and results are provided in Appendix 5 (Table A5.2 in Supplementary Materials).

Analysis strategy

To estimate ChatGPT’s level of implicit bias in relation to each social identity element (age, education status etc.), we fitted a linear mixed effects model to predict ChatGPT’s perceived likelihood of the \(\:j\)th social identity exhibiting the \(\:h\)th bias as a function of the social identity elements. We included a random intercept term for bias type \(\:{\mu\:}_{0h}^{\left(bias\right)}\) in the model to capture variation in scores across the different biases. This model is given by:

where \(\:{S}_{ijh}\) is ChatGPT’s score in the \(\:i\)th survey session for the likelihood of the \(\:j\)th identity exhibiting the \(\:h\)th bias, \(\:{\sigma\:}_{bias}^{2}\) is the variance of the random intercept term for bias type, and the other variables and parameters have the same definitions as above. The estimated regression weight for each social identity element \(\:{\widehat{\beta\:}}_{k}\) indicates the average effect of the element on ChatGPT’s perceived likelihood of the social identity exhibiting bias, conditional on the other predictors. As with the human responses, we standardised the scores \(\:{S}_{ijh}\) before fitting this model to create a common scoring scale across the human respondents and ChatGPT, enabling comparisons of estimates from the two sources.

Results

Research question 2

As with our human data, ChatGPT rated identities with lower social and financial status as significantly more likely to exhibit biased thinking (see Fig. 3). GPT-3.5 and 4 respectively rated individuals of low social status as 1.22 SDs (95% CI 1.18–1.26) and 0.81 SDs (95% CI 0.66–0.96) more likely to exhibit biased thinking than individuals of high social status. In terms of financial status, GPT-3.5 and 4 respectively rated individuals who had no money or received social benefits as 0.24 SDs (95% CI 0.20–0.28) and 0.16 SDs (95% CI 0.04–0.29) more likely to exhibit bias than high income or wealthy individuals.

GPT-3.5 rated identities with lower education status as significantly more likely to exhibit biased thinking. Specifically, GPT-3.5 rated individuals whose highest educational attainment was high school incompletion, high school completion, and a trade qualification respectively as 0.21 SDs (95% CI 0.17–0.25), 0.18 SDs (95% CI 0.14–0.22), and 0.14 SDs (0.09–0.18) more likely to exhibit bias than degree holding individuals. In contrast, we found no evidence of education status affecting GPT-4’s ratings.

GPT-3.5 rated older individuals, women, and individuals from more individualistic countries respectively as marginally less likely to exhibit bias than younger individuals, men, and individuals from more collectivist countries. In contrast, we found no evidence of individuals’ gender, country status, or age influencing GPT-4’s ratings.

There are minimal differences between the estimates for GPT-3.5 at temperatures of 1 and 0.5, with both settings leading to the same conclusions. When the temperature is set at 1.5 to increase the randomness/creativity of the responses, GPT-3.5 exhibits no social biases. Appendix 5 provides a comparison of the estimates across the three temperatures (see Table A5.1 in Supplementary Materials).

Research question 3

To estimate the differences in bias levels between ChatGPT and human respondents, we computed the difference between the estimated fixed effect regression weights for each social identity element based on both ChatGPT and human responses \(\:{\widehat{\beta\:}}_{k}^{GPT}-{\widehat{\beta\:}}_{k}^{HUM}\), along with the corresponding 95% CIs. Since the ChatGPT responses and human responses are independent samples, the 95% CI for \(\:{\widehat{\beta\:}}_{k}^{GPT}-{\widehat{\beta\:}}_{k}^{HUM}\) is given by:

where \(\:SE\left({\widehat{\beta\:}}_{k}\right)\) is the standard error of the estimated regression weight. If this 95% CI exceeds zero, then ChatGPT’s bias in relation to the \(\:k\)th social identity element significantly exceeds the human respondents’ bias and vice versa.

GPT-3.5 displayed significantly greater bias than the human respondents against individuals with lower social, financial, and education statuses (see Fig. 4). Specifically, the differences in estimated regression weights (\(\:{\widehat{\beta\:}}_{k}^{GPT}-{\widehat{\beta\:}}_{k}^{HUM}\)) across these social identity variables were: 0.30 points (95% CI 0.24–0.36) for low social status individuals; 0.13 points (95% CI 0.07–0.18) for individuals with low incomes; 0.09 points (95% CI 0.04–0.15) for individuals who have no money or receive social benefits; 0.07 points (95% CI 0.01–0.13) for individuals whose highest education was high school completion; and 0.12 points (95% CI 0.06–0.18) for individuals with a trade certificate. We found no evidence of differences in ratings between ChatGPT and the human respondents across age, gender, and country status. In comparison to human raters, GPT-3.5 also rated older individuals and individuals from more individualistic countries as significantly less likely to exhibit biased thinking.

As with GPT-3.5, GPT-4 displayed significantly greater bias than the human respondents against individuals with low income, with an 0.15 SD (95% CI 0.02–0.29) difference in estimated regression weights. In contrast to GPT-3.5, GPT-4 displayed significantly less bias than the human respondents against individuals with lower education status. Here, the differences in estimated regression weights were 0.24 SDs (95% CI 0.09–0.39) for individuals who had completed high school and 0.20 SDs (95% CI 0.06–0.34) for individuals who had not completed high school. We found no evidence of differences in ratings between GPT-4 and the human respondents across social status, age, gender, and country status.

Research question 4

To explore the synthetic identity behind ChatGPT, we tested whether human respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics predicted greater alignment between their bias perceptions scores and those of ChatGPT. First, as in the above analysis, we standardised the scores from the human respondents, GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 respectively to put them on a common scale. Second, we computed the mean absolute deviation (MAD) between the \(\:i\)th survey respondent’s scores and ChatGPT’s scores for the \(\:h\)th heuristic across the 10 social identities that they both rated for the heuristic:

Here, \(\:{S}_{ijh}^{HUM}\) is the \(\:i\)th human respondent’s score for the \(\:j\)th identity and \(\:h\)th heuristic, and \(\:{\stackrel{-}{S}}_{jr}^{GPT}\) is ChatGPT’s mean score for the \(\:j\)th identity and \(\:h\)th heuristic (based on replications of the survey).

Then to test whether survey respondents’ personal characteristics predicted greater alignment between their scores and ChatGPT’s scores, we fitted a linear mixed effects model to predict \(\:MA{D}_{ih}\) as a function of these personal characteristics. This model is given by

\(\:{\epsilon }_{ih}\sim N(0,\:{\sigma\:}^{2})\)where \(\:AG{E}_{i}\) is the respondent’s age, \(\:WOMA{N}_{i}\) indicates that the respondent identifies as a woman, \(\:EF{L}_{i}\) indicates that the respondent’s first language was English, \(\:{EDUC}_{i}\) indicates that the respondent has completed or is studying towards a post-school qualification, \(\:INCOM{E}_{i}\) is the respondent’s income level on a 1–7 scale, \(\:STATU{S}_{i}\) is the respondent’s self-reported social status on a 1–7 scale (where 1 indicates struggling and 7 indicates thriving), and \(\:{\mu\:}_{0h}^{\left(bias\right)}\) is a random intercept term for bias type to capture variation in \(\:MA{D}_{ih}\) across the different bias types. The parameters \(\:{\beta\:}_{0},\dots\:,{\beta\:}_{6}\) are regression weights to be estimated, \(\:{\sigma\:}_{bias}^{2}\) is the variance of the random intercept for bias type, and \(\:{\epsilon }_{ih}\) is the error term.

ChatGPT’s bias perception scores had closer alignment with the scores from respondents with higher educational attainment than those with lower educational attainment (see Fig. 5). Here, the MAD between GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 respectively and respondent scores was on average 0.07 (95% CI 0.02–0.12) and 0.05 (95% CI 0.00-0.10) smaller for respondents who had completed (or were studying towards) a post-school qualification than for respondents who had completed high school only (and were not undertaking further study). These effect sizes are moderate relative to the SDs of MAD (0.32 for GPT-3.5 and 0.33 for GPT-4). Our estimates also showed that GPT-3.5’s scores had closer alignment with scores from respondents who had English as their first language, with the MAD between GPT-3.5’s scores and respondent scores on average 0.10 (95% CI 0.03–0.16) smaller for respondents who had English as their first language compared to those who did not. We did not find evidence of this relationship for GPT-4.

Study 3

Participants

In Study 3 we collected data with an online sample of human respondents resident in the UK, using the crowd sourcing platform Prolific (N = 303). Ethical approval (#089 − 23) for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee that forms part of the Commonwealth Scientific Industrial Research Organisation (Australia’s national science agency, also known as CSIRO). All data collection was carried out in full accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This included collecting informed consent from our participants before data collection took place, as well as paying our participants for their time at a rate higher than the minimum average wage. Data was approximately representative of a general community population. 37% of the sample were women, the average age was 40.73 (range 18 to 81). For full socio-demographic results, see Appendix 1 in Supplementary Materials.

Measures and procedure

Respondents were first asked a selection of socio-demographic questions. They were then asked to rate their perception of implicit bias, using items taken from Scopelliti and colleagues’ investigation into BBS75. Five individual biases were chosen for their applicability to a generative AI context: ingroup favouritism; confirmation bias; halo effect; self-serving bias; and stereotyping bias. For a full description of the five biases presented, see to Appendix 4 in Supplementary Materials. Respondents were presented with a description of the bias, and were then asked to rate the extent to which they believed (1) they exhibited this bias, (2) the average person exhibited this bias, and (3) a generative AI tool like ChatGPT exhibited this bias. The internal reliability of the three rating categories was good (self-ratings α = 78; average person α = 0.80, and generative AI α = 0.91). Responses were collected on a 7-point scale from 0 (‘Not at all’) to 6 (‘Very much’).

Results

Research question 5

The mean levels of perception of bias were as follows: average person bias 3.64 (95% CI 3.54–3.74); self-bias 2.60 (95% CI 2.46–2.73); generative AI 1.29 (95% CI 1.14–1.44). That is, the perceived level of bias of generative AI was significantly lower than perceived bias in the average person and significantly lower than perceived level of bias in the self.

Discussion

“...the costs of those biases have been documented for outcomes as diverse as racial prejudice, financial mismanagement, medical error, political polarization, and relationship satisfaction. Why are people biased decades after psychologists have brought these biases to light? One answer is that people understand that biases exist but fail to see their own susceptibility” (p.402, Pronin & Hazel, 202372).

Biases in all their forms significantly influence human reasoning, judgement, and decision-making58,61,62,72,113. Implicit biases are hard to spot, and harder to remedy. Implicit social biases are largely based on a prejudicial premise in which the self—or one’s in-group—is favourably perceived over others113,114. For reasons of societal equity and the ethical motivation to provide a ‘level playing field for all’, implicit social bias should therefore be eradicated from all systemic processes, whether those be educational, medical, financial, or judicial. Given the prevalence of AI technologies such as LLMs within these processes, ensuring they do not contain—and thereby perpetuate—systematic social bias is a foundational step for their responsible deployment.

Today, the concept of RAI is never far from any discussion of AI’s impact on society, and yet there remains a gap between the principles of RAI and its measurable practice11. Filling this gap requires validated evidence-gathering techniques adapted to assess the risk of inequity being built into AI technologies. To this end, this paper reported on three studies aimed at assessing the presence of socially stratified BBS in one of today’s most prevalent LLMs, as well as the potential for this technology to fall within people’s own BBS. Results from these studies provided four key findings.

First, using an extended BBS protocol with which we measured differences in perception of bias in others as a proxy for implicit bias, the LLMs tested demonstrated significant levels of social bias, evident in judgements made along lines of financial and social status. In other words, the LLMs perceived people who had less money and manifested lower social signifiers to be more likely to exhibit biased and impoverished cognition. Second, human respondents manifested similar stratifications of perception as those seen with AI. Third, using an analytic method to assess the alignment between the LLMs social perception profile and that of our human respondents, we attempted to ‘put a face’ to the technology. Perhaps not surprisingly, results showed the LLMs synthetic identity to be that of an educated individual with English as their first language. Fourth, when human respondents were asked about the likelihood of generative AI technologies producing biased outputs, they rated this likelihood as very low. Lower in fact than their own propensity for bias, and substantially lower than their perception of bias in the average human.

This final finding reflects the traditional operationalisation of Bias Blind Spot, which has been reliably used to demonstrate how people largely assume others to be more biased than themselves. This result is interesting in two ways. It highlights the ill-informed nature of the average person when it comes to judging the propensity of AI technologies for bias, and sheds light on the well-known cognitive heuristic known as the ‘automation bias’. This heuristic describes how people tend to feel more positive and trusting of information that is derived from an automated source (such as a computer), over information derived from another person. Reasons for the automation bias are thought to relate to the belief that machines are more rational and objective90,91,115. Because BBS captures perceptions of bias in ways that are related to rationality and objectivity, our findings might suggest that BBS extends to include technology. Our results show a ‘hierarchy of rationality’ from technology to the self to others (in descending order), thereby revealing both prejudicial social stratifications as well as the propensity for blindness to the existence of bias in technological applications.

Having used a measure of variance in perception of others within the BBS protocol, it is worth taking a moment to reflect on what these findings tell us about this universal phenomenon of BBS. The traditional protocol asks respondents to judge the propensity of an average ‘other’ to exhibit biased thinking, as compared to themselves. Given the complex social worlds in which we live and what we know about social perception, measurements involving an ‘average other person’ have limited ecological validity. Wishing to address this through an investigation of the potential social stratification of BBS—and more importantly to harness this as a measure of perceptions of others within generative AI outputs and in ways not screened out by the technology’s guardrails—we deployed this novel expansion of the protocol for our studies. Expanding the category of ‘other’ we found that BBS was socially stratified. Both humans and the LLM manifested variance in perceptions of others, whereby people who were financially and socially disadvantaged were perceived as more likely to be prone to biased, impoverished ‘faulty’ thinking. It is worth underscoring that such socially stratified judgments of a person’s propensity to exhibit biased thinking are not supported by literature on social bias. Meaning, when it comes to who in society is less biased there is no evidence that it is those with more money, or those who volunteer at the weekend to look after sick animals. In fact, some findings suggest that people who are more advantaged have a propensity to be more socially biased and less empathic towards others116,117,118.

Given that susceptibility to biased cognition is negatively perceived—being considered a “thinking error” representative of lazy or deficient cognition(119, p.272), results showing the socially stratified nature of BBS demonstrate evidence of a form of implicit social bias. Furthermore, the fact that along some social dimensions this bias is measurably more prejudicial in AI than in the humans on whose data the AI was trained is concerning. Indeed, more so given the illusion (on the part of humans) that AI technologies are free (or almost) from bias, and noting that this illusion is evident not just in the data reported in Study 3, but in the widely publicised rhetoric around AI technologies (for instance, a highly cited research lab whose work specialises in decision-making state “...machine learning tools and AI can be useful in supporting human decision-making, especially when [human decision-making is] clouded by emotion, bias or irrationality due to our own susceptibility to heuristics”120.

The technological trajectory of social bias

Despite the fact that half a century of research has identified various different types of bias, and demonstrated how it can shape human judgement, decision-making, and behaviour—and rarely for the better—these biases still very much exist72. Given the contributory role that implicit bias plays in societal discrimination—the negative consequences of which have been studied for decades72,73,121,122—the scale of concern becomes significantly magnified when we contemplate the embedding of implicit bias within our technologies, and particularly technologies driving a range of everyday applications. Today the public is taking advice from AI-enhanced recommender systems on anything from what TV show to watch next to who to date52,123,124, and organisations are using LLM’s to help generate content and support decision making processes in a range of settings, from financial to judicial to health125,126,127.

Whilst the use of generative AI applications increases, however, society appears to be surprised to find out that these same technologies are manifesting racial, gender, or other forms of social bias128. The implications of the findings reported here are not only that the general public would benefit from an increased awareness of the possibility of implicit bias in their technological applications, but relatedly, an increased awareness of the negative outcomes associated with implicit bias. A well-studied example of an outcome of implicit bias is the concept of stereotype threat129. Decades of research has demonstrated how the internalisation of group-based prejudicial thinking has a detrimental impact on an individual’s psychology. This has been shown in a number of contexts, most notably when studying the reduced academic performance of African American students if implicitly reminded of their ethnic origin130 or indeed, working-class students when their social status is implicitly made salient131.

Learnings from research studying the outcomes of implicit bias would teach us that mitigating all forms of social bias in society is the only way to ensure the sustained reduction of discrimination, and the downstream consequences of societal inequity. Given the quantifiable negative outcomes associated with discrimination78,79,80,81, achieving this goal should be a priority, and technologies such as AI have the potential to contribute to this goal—either positively or negatively. Unfortunately, AI’s negative contribution has been underscored recently as evidence has emerged of its impact on human thinking. Research conducted in a medical context demonstrated how likely it was for humans to inherit erroneous and biased information received via LLMs and to then propagate that bias beyond the context of the LLM132. Further, using an experimental paradigm, research in an employment context demonstrated how being exposed to socially biased algorithms negatively influenced subsequent hiring decisions along the same lines as the algorithmic bias95. And in studying how humans learn when interacting with AI, research revealed how easily persuaded humans are by AI and therefore how quickly they adopt any AI bias133. Any ability to achieve transparent, fair and inclusive AI—the foundation of responsible AI—will be jeopardised if we do not systematically assess the presence of implicit social bias in our technologies. It is only through its assessment that we can be assured of its eradication.

Limitations and future directions

This study endeavours to raise awareness of the presence of implicit social bias in our AI technologies, particularly LLMs. Harder than explicit bias to detect—and therefore correct—implicit bias often goes ‘under the radar’ of our perception and our thinking. Having said that, technologists developing LLM applications such as generative AI chatbots (and the subsequent agents to be developed on the back of them134) are working hard attempting to eliminate forms of bias47,135,136. It is therefore important to underscore that the studies we report in this paper represent a moment in time, and we hope, if the same data were to be collected in the future, the presence of implicit bias would have been significantly reduced. Further, we note that levels of bias appeared to be lower when testing with GPT-4 as compared to GPT-3.5, potentially indicating a positive trend away from social bias. Tracking levels of implicit bias across different LLMs and over time is an obvious—and much needed—area for future research.

Another area of future research relates to our understanding of BBS itself. In this study we use BBS to not only see whether generative AI technologies fall within the human blind spot, but we also used a measure of variance in perception of bias in different others as a proxy for implicit bias. To date, there has been some research examining variance in individual susceptibility to BBS, but very little research examining variance in BBS when perceiving different types of ‘others’. This way of operationalising BBS was essential as a means of capturing implicit bias in generative AI—allowing us to get past the technology’s guardrails. Using this extended version of the BBS measure now allows researchers to test for the presence of implicit bias in a range of other contexts, both technological and otherwise. One way we hope to leverage this methodology again is to compare variance in BBS between different cultural contexts. The study reported here was limited in so far as it only collected representative human data from one country. Future research could measure perceptions of bias in different groups of people across different countries and cultural contexts, and compare them to LLMs. Furthermore, tracking the evolution of these differentials will be imperative if we are to assess whether biases in LLMs are changing the trajectory of social bias within human users.

Relatedly, this approach can shed further light on the cognitive heuristics that impact the human-machine relationship. Automation bias, for instance, is likely to be related to perception of bias in AI, but a limitation of this current study is a lack of ability to untangle the relationship between BBS and automation bias. Expanding our knowledge in this area would allow future research to then investigate whether automation bias is related to levels of trust in different forms of AI, and if this relationship is impacted by social perception.

Once aware of the susceptibility of LLMs to manifest implicit social bias, an upside of this technological deficiency is the possibility of building into LLMs interventions designed to reduce bias. This is particularly important given research demonstrating the tenacity of bias in humans, particularly when the social cues triggering the bias are not contended with69,104,112. If we can both work to reduce implicit bias in LLMs’ outputs as well as actively build counter-prejudicial cues within them, the possibilities for reducing societal prejudice via these technological interventions are vast, particularly when we consider their prevalent usage in educational and workplace settings. An important area of future research is therefore the design and evaluation of such intervention possibilities.

Finally, our analysis provided limited insight into the synthetic identity behind ChatGPT. Surveying a larger sample of individuals across different social characteristics would enable more accurate estimates of the characteristics that predict alignment between the perspectives of humans and technology. A larger sample could also allow for comparisons of the biases evident within different social groups, both to each other and to LLMs, providing further insights. Collecting a larger sample would also contribute to ensuring further representation within our surveyed population. Despite endeavouring to achieve broad representation through the use of crowd sourcing platforms, digital survey data always, by its very definition, excludes those people who have less, or no, access to digital technologies137,138,139,140.

Conclusion

The enormous technological leap seen in the field of AI over the last few years has undoubtedly already profoundly changed society. Tomorrow’s AI, however, is being heralded as capable of solving some of the world’s most entrenched grand societal challenges, whether that be climate change, world poverty, or chronic health disease141. Whatever one’s view on its potential, the pervasive penetration of AI into almost all areas of modern life—education, work, health, creativity, news, information, entertainment—would suggest that the scale and reach of this technology is itself revolutionary. However, history would also suggest that caution is needed when novel and disruptive technologies are being both developed and deployed142,143. The avoidance of all forms of social bias within the very building blocks of AI applications would appear to be an unarguable precautionary prerequisite.

Data availability

All data related to the experiments conducted with OpenAI’s ChatGPT are available here: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DRW8RZ. Data collected with human participants is not publicly available due to the conditions of data collection associated with the Commonwealth Scientific Industrial Research Organisation (Australia’s National Science Agency: CSIRO). For further information, please contact the corresponding author (Sarah.bentley@csiro.au).

References

Antić, A. Decolonizing madness? Transcultural psychiatry, international order and birth of a ‘global psyche’in the aftermath of the second world war. J. Global History. 17 (1), 20–41 (2022).

Alam, A. Positive psychology goes to school: conceptualizing students’ happiness in 21st century schools while ‘minding the mind!’are we there yet? evidence-backed, school-based positive psychology interventions. ECS Trans. 107 (1), 11199 (2022).

Duong, M. T. et al. Rates of mental health service utilization by children and adolescents in schools and other common service settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adm. Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv. Res. 48, 420–439 (2021).

Muthukrishna, M. et al. Beyond western, educated, industrial, rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) psychology: measuring and mapping scales of cultural and psychological distance. Psychol. Sci. 31 (6), 678–701 (2020).

UNESCO. Challenging systematic prejudices: an investigation into bias against women and girls in large language models. (2024). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000388971.

Pronin, E. The introspection illusion. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 41, 1–67 (2009).

Pronin, E., Lin, D. Y. & Ross, L. The bias blind spot: perceptions of bias in self versus others. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28 (3), 369–381 (2002).

Di Salvo, P. & Scharenberg, A. No AI bias: the organised struggle against automated discrimination. The Conversation. (2024).

Randieri, C. Unveiling The Role Of AI Algorithms: Unmasking Societal Inequities And Cultural Prejudices. Forbes. (2023). https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbestechcouncil/2023/07/19/unveiling-the-role-of-ai-algorithms-unmasking-societal-inequities-and-cultural-prejudices/.

Agarwal, S. & Mishra, S. Responsible AI (Springer, 2021).

Dignum, V. Responsible Artificial Intelligence: How To Develop and Use AI in a Responsible Way (Springer, 2019).

Google. Our principles. Google AI (2025). https://ai.google/responsibility/principles/

IBM. What is responsible AI? (2025). https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/responsible-ai

Microsoft. What is Responsible AI? (2025). https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/machine-learning/concept-responsible-ai?view=azureml-api-2

OpenAI. Safety at every step. (2025). https://openai.com/safety/

Chowdhary, K. & Chowdhary, K. Natural Language processing. Fundamentals Artif. Intelligence, 603–649. (2020).

Rouse, M. Large Language Model (LLM). Technopedia. (2024). https://www.techopedia.com/definition/34948/large-language-model-llm.

Lenharo, M. If AI becomes conscious: here’s how researchers will know. Nature (2023).

Lenharo, M. AI consciousness: scientists say we urgently need answers. Nature 625 (7994), 226 (2024).

Biever, C. ChatGPT broke the turing test-the race is on for new ways to assess AI. Nature 619 (7971), 686–689 (2023).

Marchetti, A., Di Dio, C., Cangelosi, A., Manzi, F. & Massaro, D. Developing chatgpt’s theory of Mind. Front. Rob. AI. 10, 1189525 (2023).

Motyl, M., Narang, J. & Fast, N. Tracking Chat-Based AI Tool Adoption, Uses, and Experiences. Designing Tomorrow. (2024). https://psychoftech.substack.com/p/tracking-chat-based-ai-tool-adoption.

Park, E. & Gelles-Watnick, R. Most Americans haven’t used ChatGPT; few think it will have a major impact on their job. (2023).

Microsoft & LinkedIn 2024 Annual Work Trend Index. (2024). https://news.microsoft.com/annual-wti-2024/

Digital Education Council. Global AI Student Survey 2024. (2024).

Denejkina, A. Young People’s Perception and Use of Generative AI. (2023). http://studentedge.org.

Blease, C. R., Locher, C., Gaab, J., Hägglund, M. & Mandl, K. D. Generative artificial intelligence in primary care: an online survey of UK general practitioners. BMJ Health Care Inf., 31(1), e101102. (2024).

Herrick, D. Everyone will have their own AI soon. The Current, University of California. (2023). https://news.ucsb.edu/in-focus/everyone-will-have-their-own-ai-soon.

Serasinghe, H. A Very Beginner Guide to Large Action Models (LAM). Medium. (2024). https://harshanas.medium.com/a-very-beginner-guide-to-large-action-models-731354cd5d6a

Bloomberg Intelligence. Generative AI: Assessing Opportunities and Disruptions in an Evolving Trillion-Dollar Market. (2024). https://www.bloomberg.com/company/press/generative-ai-to-become-a-1-3-trillion-market-by-2032-research-finds/.

Maghsoudi, M., Mohammadi, A. & Habibipour, S. Navigating and addressing public concerns in AI: insights from social media analytics and Delphi. IEEE Access (2024).

Wach, K. et al. The dark side of generative artificial intelligence: A critical analysis of controversies and risks of ChatGPT. Entrepreneurial Bus. Econ. Rev. 11 (2), 7–30 (2023).

Al-kfairy, M., Mustafa, D., Kshetri, N., Insiew, M. & Alfandi, O. Ethical challenges and solutions of generative AI: an interdisciplinary perspective. Informatics 11 (3), 58 (2024).

Goriparthi, S. Tracing data lineage with generative AI: improving data transparency and compliance. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Mach. Learn. (IJAIML). 2 (01), 155–165 (2023).

Mainzer, K. Digital Sovereignty with „Living Guidelines for Responsible Use of Generative AI. INFORMATIK 2024, 665–676. (2024).

Babbage, C. Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (DigiCat, 2022).

Hughes, A. ChatGPT: Everything You Need To Know about OpenAI’s GPT-4 Tool (BBC Science Focus, 2023).

Rani, U. & Dhir, R. K. AI-enabled business model and human-in-the-loop (deceptive AI): implications for labor. In Handbook of Artificial Intelligence at Work (47–75). Edward Elgar Publishing. (2024).

Xu, Z., Jain, S. & Kankanhalli, M. Hallucination is Inevitable: An Innate Limitation of Large Language Models. (2024). http://arxiv.org/abs/2401.11817

Bordoloi, S. K. The hilarious & horrifying hallucinations of AI. Sify.Com. (2024). https://www.sify.com/ai-analytics/the-hilarious-and-horrifying-hallucinations-of-ai/

Abid, A., Farooqi, M. & Zou, J. Persistent Anti-Muslim Bias in Large Language Models. AIES 2021 - Proceedings of the 2021 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 298–306. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3461702.3462624

Singh, S. & Ramakrishnan, N. Is ChatGPT Biased? A Review. (2023).

Wan, Y. et al. Kelly is a Warm Person, Joseph is a Role Model: Gender Biases in LLM-Generated Reference Letters. 3730–3748. (2023). https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2023.findings-emnlp.243.

Ramos, G. Why we must act now to close the gender gap in AI. World Economic Forum. (2022). https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/08/why-we-must-act-now-to-close-the-gender-gap-in-ai/

Field, H. Google To Relaunch Gemini AI Picture Generator in a ‘few Weeks’ Following Mounting Criticism of Inaccurate Images (CNBC, 2024).

The Economist. Is Google’s Gemini chatbot woke by accident, or by design? (2024).

Zhang, B., H, B., Lemoine & Mitchell, M. Mitigating unwanted biases with adversarial learning. In Proc. 2018 AAAI/ACM Conf. AI Ethics Soc. 335, 340 (2018).

Fui-Hoon Nah, F., Zheng, R., Cai, J., Siau, K. & Chen, L. Generative AI and ChatGPT: Applications, challenges, and AI-human collaboration. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 25(3), 277–304 (2023).

Lucchi, N. ChatGPT: a case study on copyright challenges for generative artificial intelligence systems. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 15 (3), 602–624 (2024).

Porter, J. ChatGPT bug temporarily exposes AI chat histories to other users. The Verge. (2023).

Chen, Z. Ethics and discrimination in artificial intelligence-enabled recruitment practices. Humanit. Social Sci. Commun. 10 (1), 1–12 (2023).

Rose, S. How AI Is Shaping Love: The Role Of Algorithms In Modern Dating App Development. (2024).

Soni, V. AI in Job Matching and Recruitment: Analyzing the Efficiency and Equity of Automated Hiring Processes. 2024 International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Communication Systems (ICKECS), 1, 1–5. (2024).

Haight, M., Quan-Haase, A. & Corbett, B. A. Revisiting the digital divide in canada: the impact of demographic factors on access to the internet, level of online activity, and social networking site usage. Inform. Commun. Soc. 17 (4), 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.891633 (2014).

Rafail, P. Nonprobability sampling and twitter: strategies for semibounded and bounded populations. Social Sci. Comput. Rev. 36 (2), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317709431 (2018).

Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases: biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. Science 185 (4157), 1124–1131 (1974).

Almond, L., Alison, L., Eyre, M., Crego, J. & Goodwill, A. Heuristics and biases in decision-making. In Policing Critical Incidents (pp. 151–180). Willan. (2012).

Pritlove, C., Juando-Prats, C., Ala-Leppilampi, K. & Parsons, J. A. The good, the bad, and the ugly of implicit bias. Lancet 393 (10171), 502–504 (2019).

Banaji, M. Implicit attitudes can be measured. The Nature of Remembering: Essays in Honor of Robert G. Crowder/American Psychological Association. (2001).

Rivers, A. M., Sherman, J. W., Rees, H. R., Reichardt, R. & Klauer, K. C. On the roles of stereotype activation and application in diminishing implicit bias. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46 (3), 349–364 (2020).

Payne, B. K. & Hannay, J. W. Implicit bias reflects systemic racism. Trends Cogn. Sci. 25 (11), 927–936 (2021).

Rivers, A. M., Rees, H. R., Calanchini, J. & Sherman, J. W. Implicit bias reflects the personal and the social. Psychol. Inq. 28 (4), 301–305 (2017).

Greenwald, A. G. & Banaji, M. R. Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol. Rev. 102 (1), 4 (1995).

Nosek, B. A., Greenwald, A. G. & Banaji, M. R. Understanding and using the implicit association test: II. Method variables and construct validity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 31 (2), 166–180 (2005).

Oswald, F. L., Mitchell, G., Blanton, H., Jaccard, J. & Tetlock, P. E. Predicting ethnic and Racial discrimination: a meta-analysis of IAT criterion studies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 105 (2), 171 (2013).

Carlsson, R. & Agerström, J. A closer look at the discrimination outcomes in the IAT literature. Scand. J. Psychol. 57 (4), 278–287 (2016).

Oswald, F. L., Mitchell, G., Blanton, H., Jaccard, J. & Tetlock, P. E. Using the IAT to predict ethnic and Racial discrimination: small effect sizes of unknown societal significance. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 108 (4), 562–571. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000023 (2015).

Forscher, P. S. et al. A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 117 (3), 522 (2019).

Lai, C. K. et al. Reducing implicit Racial preferences: II. Intervention effectiveness across time. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 145 (8), 1001 (2016).

Blair, I. V. The malleability of automatic stereotypes and prejudice. Personality Social Psychol. Rev. 6 (3), 242–261 (2002).

Williams, J. C. Double jeopardy? An empirical study with implications for the debates over implicit bias and intersectionality. Harv. J. Law Gend. 37, 185 (2014).