Abstract

The glacial record of gLGM and T1 millennial-scale ice readvances is not continuous across the Patagonian Icefields. Whether missing records indicate that some ice lobes did not readvance during this time, or whether they are the result of burial or erosion of the record, remains to be investigated. We use high-resolution seismic reflection data to probe the glaciolacustrine sediments of Lago Argentino for subaqueous evidence of glacier readvances during the gLGM and T1. The data image a \(\sim\)150 m tall, >5.5 km wide double crested moraine and an overlying erosional landform preserved beneath >115 m of glaciolacustrine sediments, interpreted to mark the frontal positions of the ice during the gLGM and of subsequent grounding line oscillations during the early phase of T1. In addition, the data image the 5 km-wide, \(\sim\)120 m tall frontal, submerged counterpart of a moraine system previously mapped and dated on land associated with the ice readvance during the Antarctic Cold Reversal (ACR). By imaging submerged and buried glacial landforms on the eastern margin of the Southern Patagonian icefield, this study contributes first-order constraints on the extent of glacial conditions during the gLGM and T1 in Patagonia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The last glacial termination (T1; \(\sim\)18–11.7 ka1) was arguably the most profound climate and environmental change of the last 100-kyr cycle, and involved rapid climate warming punctuated by minor cold reversals, drastic collapse of ice sheets and the reorganization of the ocean-atmospheric circulation following the global Last Glacial Maximum (gLGM; 26.5-19 ka1). The deglaciation was part of a cyclic pattern shown to represent the non-linear responses of global climate system to the combined effect of astronomical forcings and of the feedback between the cryosphere, biosphere and the ocean-atmosphere coupled systems2,3. In first approximation, Milankovich orbital parameters control the dominant 100-kyr cycle periodicity of the late Pleistocene glaciation in the Northern Hemisphere1,4. Different and potentially complementary mechanisms have been proposed to explain how the astronomical forcing are transmitted in climate systems around the globe5, invoking hemispheric coupling via the oceans (i.e., the bipolar ocean seesaw6), or bipolar hemispheric teleconnections via the atmosphere7,8. These mechanisms predict different timing of north-south climate variations during the deglaciation, with climate shifts occurring synchronously but out-of-phase between hemispheres according to the bipolar seesaw, or in phase, through a strengthening and southward displacement of the southern westerly wind (SWW) belt1. A consistent in-phase signal is starting to emerge from recent compilations of mapping and dating of mid-latitude mountain-glacier moraines on both hemispheres9,10,11, challenging the bipolar seesaw paradigm, and supporting the critical role played by latitudinal changes of SWW in driving global ocean circulation through connection with the Southern Ocean and regulating atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases and high-latitude ocean productivity12. Accurate reconstruction of the location, timing and extent of the ice fluctuations during the T1 in the Southern Hemisphere is paramount to test the validity of proposed mechanisms for global climate change.

Patagonia offers the unique opportunity to reconstruct the timing, structure and magnitude of the last glacial maximum and its termination, thanks to well-preserved nested sequences of moraines deposited by outlet lobes that flowed onto the Andean foreland basins east of the Andes (e.g., ref.13). Detailed mapping and dating of these deposits has laid the foundation of climate and glacier chronology in the region (e.g., ref.14), and provided insights into glacier dynamics (e.g., ref.15). Some glacial records in southern Patagonia16,17,18 and Antarctica19 indicate that maximum ice expansion took place during Marine Isotope Stage 3 (MIS 3, \(\sim\)59,400 to 27,800 years ago) or earlier, preceding the gLGM, with less extensive glacial conditions during MIS 2 (\(\sim\)27,800 to 14,700 years ago). Detailed geochronology of moraines west of MIS 3-age moraines reveals that while many outlet lobes of the former Patagonian Ice Sheet advanced in broad synchronicity with the gLGM, during MIS 2, (e.g.4,20,21), a gLGM response is not observed ubiquitously across the icefield. For example, episodes of readvance or stillstand coeval with the gLGM have been documented in Torres del Paine (21.5±1.8 ka17), Lago San Martin (22.4±2.3 ka13), Río Blanco (26.0±0.9 ka, 22.8±1.0 ka, and 19.1±0.7 ka22,23), Strait of Magellan (24.6±0.9 ka16), and Rio Guanaco Valley (19.7 ka±1.124), as well as further north in Lago Palena/General Vintter basin (19.7±0.7 ka25 and in Rio Corcovado (lasting between 22.5-19.5 ka26). Many of these former outlet lobes also deposited moraines west of \(\sim\)20 ka moraines that have been broadly dated between \(\sim\)18-17 ka (e.g.,4,16,23,24), but evidence of MIS 2 moraines appears to be missing at Lago Argentino, despite extensive work in the area (e.g., refs.27,28,29).

The majority of existing geomorphic and geochronologic reconstructions in Patagonia are based on glacial landforms preserved on land, which, albeit extensive, are prone to erosion and/or burial by subsequent glacial and non-glacial events30,31, such as glacier readvances overriding evidence of older advances32, paraglacial slope processes33,34, and fluvial dissection35. Incomplete preservation of glacial landform is common in areas where the ice lobes retreated over higher topographic gradients and overdeepened valleys36, characteristic of proglacial lakes. In such areas, glacial sediment and structures can instead be buried under glaciolacustrine deposits and sheltered from erosion, preserving the frontal portions of moraine systems that may not be exposed on land.

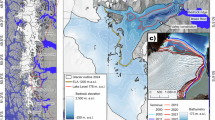

We investigate the subaqueous record for evidence of MIS 2 readvances at Lago Argentino, an ice-contact lake located directly east of the modern Southern Patagonian Icefield (SPI) at 50\(^{\circ }\)S, 73\(^{\circ }\)W. Lago Argentino has one of the best-preserved glacial moraine records on land documenting the Late Pleistocene ice evolution in the southern middle latitudes. The latest terrestrial advances east of the modern lake have been found to be coeval with MIS 3 (El Tranquilo moraines, 44.5±8.0 and 36.6±1.0 ka, based on 10Be cosmogenic nuclide surface exposure dating on moraine boulders)27,29 (Fig. 1). Three distinct moraine belts west of the MIS 3 margin, (Puerto Bandera 1-3 moraines, the oldest dated to \(\sim\)12,990 cal yr BP, determined using the IntCal09 curve and not re-calculated using the latest calibration curve for the Southern Hemisphere27,37) signal the advance during the Antarctic Cold Reversal (ACR). In the neighboring Rio Guanaco Valley north of the lake, multiple MIS 2-age moraines record ice stability at 19.7 ±1.1 ka and significant retreat starting at 18.9 ±0.4 ka24, but despite numerous investigations, evidence of a glacial readvance during MIS 2 around Lago Argentino is missing.

Topographic and satellite (inset) map of the study area showing the location of the seismic reflection data used for this study (all, solid gray lines; shown, solid black lines). Solid, colored lines: mapped and dated moraines with ages taken from original studies27,29. Dashed, colored lines: subaqueous moraines and glacial landforms mapped by this study. Lake bathymetry modeled from seismic data from this study, displayed with 100 m contours. White circles and black labels along the seismic profiles indicate distance in km. The hillshade basemap was generated using Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data67,68 (Void Filled, 3-arc second global) in ESRI ArcGIS Pro available from https://www.esri.com and used herein under license. The satellite map was generated using Maxar, Earthstar Geographics imagery in ESRI ArcGIS Pro available from https://www.esri.com and used herein under license.

Using high resolution marine seismic reflection data, we image the glacial and glaciolacustrine deposits preserved in the lake to identify and map the position of the MIS 2 ice front in Lago Argentino and the morphology of the subaqueous moraines. Integrating existing land glacial chronology with newly discovered evidence, we provide first-order constraints on the extent of glacial conditions during the gLGM and T1 in this region of Patagonia.

Results

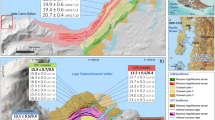

Four seismic facies, or groups of distinct acoustic properties and reflective character, are identified in the data, similar to those recognized in other alpine lacustrine environments38,39,40,41 . The facies are interpreted consistently with analogous seismic signatures observed in other proglacial settings in Patagonia42,43,44 (Fig. 2). Facies M contains high amplitude hummocky, mounded, discontinuous to chaotic reflections and acoustically transparent reflectivity, interpreted as subglacial ice-marginal till forming recessional moraine banks built during glacial stillstands45. The medium to high amplitude, coarsely layered to chaotic reflections of Facies P suggest increased sediment sorting and a water settling depositional environment, interpreted as subaqueous outwash delivered in the ice-proximal setting46,47. This facies often transitions laterally and vertically into facies D, which contains finely layered, well-stratified, continuous, draping reflections, indicative of a low-energy environment. We interpret facies D as ice-distal glaciolacustrine sediment deposited during interglacial or retreating events, similarly to refs.42,44,46,47. Facies F contains variable amplitude, folded and pervasively truncated reflections, and may represent glaciotectonically deformed stratified sediment.

Five major unconformities (D0-D4) are identified representing erosional truncations and prominent changes in deposition that mark past retreat and advances of ice across the lake. These unconformities bound five separate seismic units (SU1-5), which are interpreted using the seismic facies elements that compose them (Figs. 3, 4). The basal unconformity D0 follows a ubiquitous reflection beneath which seldom discontinuous reflections are imaged (Figs. 3, 4). The unconformity shallows toward the lake shores, where it can be correlated with outcropping bedrock. Above D0 lies seismic unit 1 (SU1), almost everywhere characterized by facies M (Figs. 3, 4) and marked at the top by the highly reflective erosional contact D1. This unit thickens at the center of the basin (\(\sim\)35 km distance, Fig. 3a, b) where its top (D1) forms a \(\le\)150 m- thick double crested structure, and dramatically thins westward (Fig. 3). Both overlying units SU2 and SU3 onlap on D1 (Figs. 3, 4), suggesting that this unconformity marks a prominent change in depositional conditions. Similarly to SU1, SU2 consists only of facies M, and is bounded by highly reflective erosional unconformities (D1 and D2 at the bottom and top respectively). This unit has a flat top of high amplitude reflections that are smooth in the W-E direction (Fig. 3a, b) and rugged in the N-S direction with troughs as deep as \(\sim\)30 m and <400 m wide (Fig. 4a, b). SU2 appears to be profoundly eroded along a \(\sim\)100 m-tall concave scarp surface (\(\sim\)20-25 km distance, Fig. 3a, b). Above, SU3 drapes over and infills the underlying D2 rugged topography, dominated by facies M and P (Fig. 4a, b). Unit SU4 onlaps onto SU3 along D3, showing elements of facies D. The unit thickens dramatically to the west, where it forms a 4 km-long, 30-140 m-thick eastward-thinning wedge characterized by facies M and F (\(\sim\)15 km distance3c, d), and a \(\sim\) 5 km-wide crested mound rising \(\sim\)120 and 50 m above the surrounding lakefloor to the east and west, respectively, and characterized by facies M (\(\sim\)9-14 km distance, Fig. 3a, b). SU5, the shallowest unit, is ubiquitously imaged across the lake and is characterized by facies D (Figs. 3, 4).

(a) Uninterpreted and (b) interpreted composite W-E multi-channel seismic reflection profile LINE1, showing seismic facies (M-F), reflection truncations (blue arrows), seismo-stratigraphic units SU1-SU5 separated by regional unconformities D1-D4 above the acoustic basement (D0). LF: Lakefloor; multiple: water-bottom reverberation (noise). The data image the position of the subaqueous ACR-age Puerto Bandera 2 moraines that correlate with their mapped locations on land27. To the east, the glaciolacustrine deposits preserve a buried erosional structure (scarp) and a double crested moraine that predate s the ACR within SU2 and SU1, respectively (b); (c) Glaciotectonic thrust complex uninterpreted, and (d) interpreted. The complex contains imbricate thrusts extending east of the Puerto Bandera 2 moraine for 4 km length and up to 140 m in height, an aspect ratio of 1:28 that is typical of wide push moraines48. Decollement surfaces separate the glaciotectonically disturbed material above from undisturbed material below. These structures are likely to form within weak layers49 and in settings where substratum loading rates greatly outpace pressure dissipation rates, resulting in a rapid increase of pore fluid pressure and reduction of the effective and shear stress, which facilitate brittle failure that can propagate far from the glacial front (e.g., refs.49,50). The presence of a thrust complex here suggests rapid advance of the glacier front during the ACR advance.

(a) Uninterpreted and (b) interpreted N-S multi-channel seismic reflection profile LINE3 showing seismic facies (M-F), reflection truncations (blue arrows), seismo-stratigraphic units SU1-SU5 separated by regional unconformities D1-D4 above the acoustic basement (D0). Inset shows scour features at the top of SU2 filled by layered, onlapping reflections. LF: Lakefloor; multiple: water bottom reverberation (noise).

Interpretation of seismic reflection data

The positions of facies in the stratigraphy and seismic units are analyzed within the context of the existing glacial chronology of Lago Argentino27,28,51. The terrestrial glacial landforms preserved in the area indicate that the basin experienced at least two major MIS 3 glacial advances and a readvance during the ACR, while record of MIS 2 readvances is missing on land. The lake bathymetry reveals a longitudinal ridge across the center of Lago Argentino rising \(\sim\)120 m above the surrounding lakefloor (Fig. 1). The morphology and location of the ridge, which corresponds to the crested mound formed by SU4 (Fig. 3), correlates with the position of the ACR moraines on land27,28 (Fig. 1). This crested landform is interpreted as the subaqueous counterpart of the frontal Puerto Bandera 2 moraine (Fig. 1), anchoring the chronology of the seismic stratigraphy.

Because the lake basin opened to sedimentation following the formation of the El Tranquilo II moraines52 (MIS 3; 36.6±1ka29), we suggest that SU1 was largely deposited during post-MIS 3 ice retreat (Fig. 3). The two crests imaged at \(\sim\)35 km distance at the top of SU1 (Fig. 3) are consistent with the typical morphology of push moraines48, and are interpreted as part of a \(\sim\)150 m-tall, >5.5 km-wide double-crested moraine complex that has been subsequently buried. We interpret the westward-dipping reflection marked by D1 that floors SU2 (Fig. 3) as a former ice-contact surface that may indicate a past grounding line position, consistent with previous interpretations53,54.

The truncation of layered reflections against the scarp surface bounding SU2 to the west (Fig. 3) indicates erosion of previously deposited material by an agent from the west. We interpret the scour surface as a former glacier grounding line position, and the morphology of SU2 as a record of ice stability that was not long-lived enough to form a crested moraine. Undulations formed by the D2 unconformity in the N-S direction (Fig. 4) are similar in size to giant ploughmarks documented along the south Patagonia continental margin produced by Antarctic icebergs55, which leads us to interpret them as scours carved by the keels of grounded icebergs, or as channels eroded by subglacial meltwater, or ice-proximal underflows at the base of a thinning glacier. Overall, we suggest that SU2 is indicative of an erosional event formed by a thinning glacier flowing over D2 and marks an interval of ice stability. The presence of facies P and stratigraphic position of SU3 (Figs. 3, 4) suggests that SU3 was delivered by an progressively retreating glacier, prior to the ACR readvance. Because SU4 contains the Puerto Bandera 2 moraine ridge (Fig. 3), we interpret this unit as having been delivered during the Puerto Bandera moraine-forming readvances, coeval with the ACR event27. The morphology of the thrust material imaged on the ice-distal flank of the Puerto Bandera 2 moraine (Fig. 3c, d) is consistent with large-scale glaciotectonic thrust complexes described in other offshore and onshore locations48,49,56,57.

The ice retreat following the ACR maximum expansion is recorded by the glaciolacustrine deposit of SU5 (Figs. 3, 4). In front of the Puerto Bandera 2 moraine, facies D reflections of SU5 onlap onto the underlying irregular D4 surface of the glaciotectonic thrust complex, sealing the deformation of the SU4 structure and marking the termination of the compressive regime (Fig. 3c, d). The persistence of facies D through the thickness of SU5 up to the lake floor indicates the establishment of ice-distal settings that continue to present day.

Discussion

The new reflection data reveal the subaqueous evolution of the ice following the abandonment of the El Tranquilo II (MIS 3) moraines (Fig. 5), and complement the existing terrestrial glacial record27,29. Evidence of a former ice margin position previously undocumented in the area is supported by the presence of a \(\sim\)150 m-tall, >5.5 km-wide, subaqueous, buried, double crested moraine complex within SU1, positioned west of the MIS 3 moraines (36.6±1.0 ka)29, and east of and stratigraphically below the ACR moraines27 (Figs. 1, 3). Radiocarbon ages from peat bog samples from the Lago Argentino glacial valleys show that the ice had abandoned the main lake and retreated into the valleys by 16,440 cal yrs BP, prior to the ACR27. This constrains the timing of the imaged moraine complex between \(\sim\)36-16 ka, likely during MIS 2, consistent with moraine ages of other glacial records in Patagonia (e.g., ref.4). We interpret the buried moraine imaged by the reflection data as evidence of the local expression of the gLGM ice front position (during MIS 2), missing from the land record in the area (Fig. 5). Based on this interpretation, we estimate a conservative retreat distance of \(\sim\)35 km from the youngest MIS 3 moraine to the gLGM ice front, corresponding to a 28\(\%\) decrease in glacier length as measured from the glacier drainage divide to the west. This decrease is consistent with the observation of the MIS 2 ice extent being up to half of the MIS 3 extent in other parts of Patagonia (e.g., refs.17,18).

Deposits above SU1 represent material delivered to the lake after the gLGM readvance (Fig. 5). Geochronological records from Patagonia indicate that multiple glaciers experienced minor readvances and/or stillstands between \(\sim\)19-17 ka, before the ACR23,37,58,59, including immediately north of Lago Argentino24, supported by palynological evidence that suggests cold and hyperhumid conditions likely due to a stronger influence of the SWWs between \(\sim\)17,900 and 19,300 cal yrs BP59. Consistent with these records, the ice front at Lago Argentino may have also experienced an episode of oscillation or stability during this time, recorded by the erosional surface (scarp) of deposited material (SU2) at the front of the standing ice (Fig. 3, 5).

The ice maximum frontal position during the ACR is constrained by the Puerto Bandera 2 moraine ridge across the lake and onshore (Fig. 3, 5). The new data show that the subaqueous expression of this ice expansion preserved in the lake sediment differs substantially from that of the land record. The ACR episode is expressed onshore as three belt systems of moraines (Puerto Bandera 1-3, from outermost to innermost27), each measuring \(\le\) 20 m in height above the surrounding terrain27,60. In contrast, the subaqueous landform preserves the frontal portion of the moraine system as one major, \(\sim\)120 m-tall single-crested ridge in the center of the lake, associated with the Puerto Bandera 2 belt. The lack of a subaqueous record of the Puerto Bandera 1 moraine and the featureless internal structure of the Puerto Bandera 2 moraine suggests that the Puerto Bandera 2-forming readvance overrode and reworked the Puerto Bandera 1 moraine material, while preserving, for the most part, the subaerial Puerto Bandera 1 moraine east of and at higher elevation (by 125 m ASL) than subaerial Puerto Bandera 227. This implies that between the Puerto Bandera 1 and 2 advances, the ice was laterally thinning, and yet its front was advancing rapidly enough to generate a large-scale glaciotectonic thrust system in the till and proglacial sediments, with deformation extending for \(\sim\)4 km beyond the glacier front (Fig. 3c, d). The initial development of a decollement at the base of a glacial thrust complex as observed here is favored in settings where substratum loading rates greatly outpace pressure dissipation rates, resulting in a rapid increase of pore fluid pressure and reduction of the effective and shear stress and facilitating brittle failure that can propagate far from the glacial front (e.g., refs.49,50). The presence of these structures east of the ACR ice maximum frontal position suggests that the local expression of this ice expansion was characterized by rapid advance of the glacier front. The diverse response of different portions of the glacier terminus to the same climate signal at this time may be explained by the presence of an overdeepened proglacial lake bathymetry, affecting the ice geometry and behavior. Bedrock topography has been shown to affect the dynamics of lake terminating glaciers like the Patagonian glaciers in competing ways, by affecting subglacial water circulation and subaqueous melting, thereby promoting thinning, by assisting ice front buoyancy, thereby promoting calving, and by providing stability for the grounding line61.

Our findings, interpreted in the context of existing glacial chronologies around Patagonia, corroborate the growing evidence that Southern Patagonia glaciers responded in broad synchronicity to deglacial climate forcings, supporting models that favor propagation of climate oscillations through the Southern Ocean-SWWs coupled system at the millennial scale25,62.

Our data also confirm the higher potential for preservation of the subaqueous sediment record compared with the subaerial record. However, even the subaqueous record remains prone to significant erosional and depositional censoring, especially through bulldozing by subsequent readvances30,31. Therefore, we do not exclude the possibility of additional pre-ACR grounding line oscillations that reached some position in the western half of the lake and that could have been bulldozed by the subsequent ACR readvance, despite a lack of evidence in the reflection data and on land. Nevertheless, our results indicate that the most complete reconstruction of ice mass fluctuations by lake-terminating alpine glaciers can be obtained by comparing the moraine record preserved in both subaerial and subaqueous environments.

Cartoon illustrating the interpreted subaqueous evolution of Lago Argentino within the constraints of the existing glacier chronology of the area (e.g.27,29,37). Ice thickness not to scale. Reconstruction does account for changes in elevation associated with glacial isostatic adjustment. Dashed blue glacier outline represents estimated glacier front position and geometry. Dashed black lines represent the estimated top of material that was modified by subsequent readvance. (a) During MIS 3, ice filled the Argentino basin and deposited the El Tranquilo II (ETII) moraines29. By 36.6 ka29, the ice began retreating from the El Tranquilo II moraines, forming the proglacial lake52 and depositing SU1. (b) Possibly during the gLGM (26.5-19 ka), the ice readvanced, forming a \(\sim\)150 m tall, >5.5 km wide buried, double-crested moraine complex within SU1. (c) Between \(\sim\)19-16.4 ka, the glacier thinned and retreated, depositing SU2 prior to (d) an episode of grounding line oscillation/advance that scoured the proglacial sediment. (e) By 16.4 ka, the ice retreated into the glacial valleys of Lago Argentino27 and deposited SU3. (f) During the ACR, the ice readvanced, forming the \(\sim\)12,990 cal yr BP Puerto Bandera 1 moraines on land27 and subaqueously. (g) During the formation of the Puerto Bandera 2 moraines on land <12,990 cal yrs BP27, the ice front readvanced in the lake, bulldozing the subaqueous Puerto Bandera 1 moraines and forming the subaqueous frontal Puerto Bandera 2 moraine. This advance is associated with 4 km of horizontal glaciotectonic deformation through till and proglacial sediment. (h) By 12,350±120 cal yrs BP27, the ice abandoned the Puerto Bandera 2 moraines and retreated to the west into the cordillera.

Conclusions

Lacustrine high resolution seismic reflection imaging of Lago Argentino, Patagonia (50\(^{\circ }\)S), integrated with existing terrestrial glacial records, shows the ice front position during the gLGM and the subsequent deglaciation (T1). Two discrete glacial landforms, constrained in age as post-MIS 3 and pre-ACR by the stratigraphy, are imaged buried in the glaciolacustrine sediment. A \(\sim\)150 m-tall, >5.5 km-wide double-crested moraine complex is interpreted to represent the gLGM ice front, undocumented on land in the area but recorded across Patagonia13,16,17,24. An overlying wedge of material riddled with W-E trending \(\sim\)30 m-deep incisions and a 100 m-tall westward dipping scour surface is interpreted as an erosional structure formed by a thinning glacier following the gLGM, possibly between 19-16.4 ka, in line with other records in Patagonia. These results show that during MIS 2, the ice at Lago Argentino was not steadily retreating, but rather underwent at least two episodes of grounding line fluctuations or stability.

In addition, the data reveal a \(\sim\)120 m-tall bathymetric high that correlates with the mapped position of the Puerto Bandera 2 moraine on land, interpreted as its subaqueous counterpart, providing new constraints for the frontal extent of ice readvance during the ACR. The data suggest that in the subaqueous environment, the Puerto Bandera 2 moraine-forming readvance bulldozed the older Puerto Bandera 1 moraine, generating a combined subaqueous moraine with a large-scale (4 km long) glaciotectonic thrust complex on its eastern (ice-distal) flank. This expression largely differs from the land record, where the Puerto Bandera 1 and 2 moraines form discrete outer and inner belts, respectively. The presence of a large-scale glaciotectonic thrust complex is indicative of a rapid grounding line advance during the ACR.

This study demonstrates that subaqueous proglacial basins preserve rich sediment archives with the potential to offer new perspectives to existing ice reconstructions that are based on land records. The application of multidisciplinary approaches to the same glacial system may facilitate the unraveling of detailed glacial histories that might not be gleaned from one method alone.

Methods

We use 250 km of high vertical resolution (\(\sim\)1-8 m) seismic reflection data collected in May and June of 2019 using a 150J boomer source and a 50 m-long, 24 channel streamer recording at a 4 ms rate (Fig. 1). The data penetrated to a depth of \(\sim\)1 km, and profiles ranged from 5-55 km in length. Data processing was performed in Halliburton Seis-Space/ProMAX® software and included bandpass filtering, muting, predictive deconvolution, normal moveout correction, stacking, and time migration (see63). Data were converted to depth using a velocity of 1650 m/s, appropriate for unconsolidated, water saturated glaciolacustrine and deeper glacial sediment (i.e.,64,65). Data were interpreted in IHS/S & P Kingdom Suite. Seismic units were defined in the imaged stratigraphy by mapping reflection truncations and considering the distribution of seismic facies and regional unconformities , following the methods of other subaqueous seismic reflection studies across glaciated landscapes (e.g.,42,44,46,47). The largest uncertainty in the interpretation of our data is the lack of a direct tie with the glacial landforms exposed on land, and that the interpretation is based on spatial correlation with the onshore landforms.

Data availibility

The seismic reflection data used in this study are available through the EarthScope Data Management System at https://ds.iris.edu/mda/23-044/ via DOI: 10.7914/qwde-1m4766. Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data (Void Filled, 3-arc second global) used to generate the Hillshade basemap displayed in Fig. 1 are openly available via DOI: /10.5066/F7F76B1X67,68. Version 5000.11.0.1 of Halliburton Seis-Space/ProMAX\(\textcircled {\hbox {R}}\) used for processing the seismic reflection data is available via academic license. IHS Markit Kingdom 2021 Seismic and Geological Interpretation Software used for interpreting the seismic reflection data is available via academic license. Esri ArcGIS Pro v3.3.0 was used for generating maps. ArcGIS\(\textcircled {\hbox {R}}\) is the intellectual property of Esri and is used herein under license.

References

Denton, G. H. et al. The last glacial termination. Science 328, 1652–1656 (2010).

Denton, G. H., Broecker, W. S. & Alley, R. B. The mystery interval 17.5 to 14.5 kyrs ago. PAGES News 14, 14–16 (2006).

Toggweiler, J. Shifting westerlies. Science 323, 1434–1435 (2009).

Denton, G. H. et al. Geomorphology, stratigraphy, and radiocarbon chronology of LlanquihueDrift in the area of the Southern Lake District, Seno Reloncaví, and Isla Grande de Chiloé, Chile. Geog. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 81, 167–229 (1999).

Pedro, J. et al. The last deglaciation: Timing the bipolar seesaw. Clim. Past 7, 671–683 (2011).

Broecker, W. S. Paleocean circulation during the last deglaciation: A bipolar seesaw?. Paleoceanography 13, 119–121 (1998).

Anderson, R. et al. Wind-driven upwelling in the Southern Ocean and the deglacial rise in atmospheric CO2. Science 323, 1443–1448 (2009).

Denton, G. H. et al. Interhemispheric linkage of paleoclimate during the last glaciation. Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 81, 107–153 (1999).

Shakun, J. D. et al. Regional and global forcing of glacier retreat during the last deglaciation. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–7 (2015).

Wittmeier, H. E. et al. Late Glacial mountain glacier culmination in Arctic Norway prior to the Younger Dryas. Quat. Sci. Rev. 245, 106461 (2020).

Young, N. E., Briner, J. P., Schaefer, J., Zimmerman, S. & Finkel, R. C. Early Younger Dryas glacier culmination in southern Alaska: Implications for North Atlantic climate change during the last deglaciation. Geology 47, 550–554 (2019).

Denton, G. H. et al. The Zealandia Switch: Ice age climate shifts viewed from Southern Hemisphere moraines. Quat. Sci. Rev. 257, 106771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106771 (2021).

Glasser, N. F. et al. Cosmogenic nuclide exposure ages for moraines in the Lago San Martin Valley, Argentina. Quat. Res. 75, 636–646 (2011).

Davies, B. J. et al. The evolution of the Patagonian Ice Sheet from 35 ka to the present day (PATICE). Earth-Sci. Rev. 204, 103152 (2020).

Glasser, N. F. & Jansson, K. N. Fast-flowing outlet glaciers of the last glacial maximum Patagonian Icefield. Quat. Res. 63, 206–211 (2005).

Kaplan, M. et al. Southern Patagonian glacial chronology for the Last Glacial period and implications for Southern Ocean climate. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.09.013 (2008).

García, J.-L. et al. The MIS 3 maximum of the Torres del Paine and Última Esperanza ice lobes in Patagonia and the pacing of southern mountain glaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 185, 9–26 (2018).

Çiner, A. et al. Terrestrial cosmogenic 10Be dating of the Última Esperanza ice lobe moraines (52\(^{\circ }\)S, Patagonia) indicates the global Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) extent was half of the local LGM. Geomorphology 414, 108381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2022.108381 (2022).

Rudolph, E. M. et al. Early glacial maximum and deglaciation at sub-Antarctic Marion Island from cosmogenic 36Cl exposure dating. Quat. Sci. Rev. 231, 106208 (2020).

Mendelova, M., Hein, A. S., McCulloch, R. & Davies, B. The last glacial maximum and deglaciation in central Patagonia, 44\(^{\circ }\) S-49\(^{\circ }\) S. Cuadernos de Investigación Geográfica 43, 719–750 (2017).

Huynh, C., Hein, A. S., McCulloch, R. D. & Bingham, R. G. The last glacial cycle in southernmost Patagonia: A review. Quat. Sci. Rev. 344, 108972 (2024).

Hein, A. S. et al. Middle Pleistocene glaciation in Patagonia dated by cosmogenic-nuclide measurements on outwash gravels. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 286, 184–197 (2009).

Hein, A. S. et al. The chronology of the Last Glacial Maximum and deglacial events in central Argentine Patagonia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1212–1227 (2010).

Murray, D. S. et al. Northern Hemisphere forcing of the last deglaciation in southern Patagonia. Geology 40, 631–634 (2012).

Soteres, R. L. et al. Glacier fluctuations in the northern Patagonian Andes (44\(^{\circ }\)S) imply wind-modulated interhemispheric in-phase climate shifts during Termination 1. Sci. Rep. 12, 10842. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14921-4 (2022).

Leger, T. P. et al. Geomorphology and 10Be chronology of the Last Glacial Maximum and deglaciation in northeastern Patagonia, 43\(^{\circ }\)S-71\(^{\circ }\)W. Quat. Sci. Rev. 272, 107194 (2021).

Strelin, J. A., Denton, G., Vandergoes, M., Ninnemann, U. & Putnam, A. Radiocarbon chronology of the late-glacial Puerto Bandera moraines, Southern Patagonian Icefield, Argentina. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 2551–2569 (2011).

Ackert, R. P. et al. Patagonian glacier response during the Late Glacial-Holocene transition. Science 321, 392–395 (2008).

Romero, M. et al. Late Quaternary glacial maxima in southern Patagonia: Insights from the Lago Argentino glacier lobe. Clim. Past 20, 1861–1883 (2024).

Kirkbride, M. & Winkler, S. Correlation of Late Quaternary moraines: Impact of climate variability, glacier response, and chronological resolution. Quat. Sci. Rev. 46, 1–29 (2012).

Barr, I. D. & Lovell, H. A review of topographic controls on moraine distribution. Geomorphology 226, 44–64 (2014).

Gibbons, A. B., Megeath, J. D. & Pierce, K. L. Probability of moraine survival in a succession of glacial advances. Geology 12, 327–330 (1984).

Ballantyne, C. K. & Benn, D. I. Paraglacial slope adjustment and resedimentation following Rrcent glacier retreat, Fåbergstølsdalen, Norway. Arct. Alp. Res. 26, 255–269 (1994).

Curry, A., Cleasby, V. & Zukowskyj, P. Paraglacial response of steep, sediment-mantled slopes to post-‘Little Ice Age’glacier recession in the central Swiss Alps. J. Quat. Sci. Publ. Quat. Res. Assoc. 21, 211–225 (2006).

Darvill, C. M., Stokes, C. R., Bentley, M. J. & Lovell, H. A glacial geomorphological map of the southernmost ice lobes of Patagonia: The Bahía Inútil-San Sebastián, Magellan, Otway, Skyring and Río Gallegos lobes. J. Maps 10, 500–520 (2014).

Owen, L. A. Mass movement deposits in the Karakoram Mountains: Their sedimentary characteristics, recognition and role in Karakoram landform evolution. Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie 35, 401–424 (1991).

Kaplan, M. R. et al. In-situ cosmogenic 10Be production rate at Lago Argentino, Patagonia: Implications for late-glacial climate chronology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 309, 21–32 (2011).

Hicks, D. M., McSaveney, M. & Chinn, T. Sedimentation in proglacial Ivory Lake, Southern Alps, New Zealand. Arct. Alp. Res. 22, 26–42 (1990).

Eyles, N., Mullins, H. T. & Hine, A. C. The seismic stratigraphy of Okanagan Lake, British Columbia; a record of rapid deglaciation in a deep ‘fiord-lake’ basin. Sediment. Geol. 73, 13–41 (1991).

Van Rensbergen, P., De Batist, M., Beck, C. & Manalt, F. High-resolution seismic stratigraphy of late Quaternary fill of Lake Annecy (northwestern Alps): Evolution from glacial to interglacial sedimentary processes. Sediment. Geol. 117, 71–96 (1998).

Van Rensbergen, P., De Batist, M., Beck, C. & Chapron, E. High-resolution seismic stratigraphy of glacial to interglacial fill of a deep glacigenic lake: Lake Le Bourget, Northwestern Alps, France. Sediment. Geol. 128, 99–129 (1999).

Waldmann, N., Ariztegui, D., Anselmetti, F. S., Coronato, A. & Austin, J. A. Jr. Geophysical evidence of multiple glacier advances in Lago Fagnano (54 S), southernmost Patagonia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1188–1200 (2010).

Waldmann, N. et al. Holocene climatic fluctuations and positioning of the Southern Hemisphere westerlies in Tierra del Fuego (54 S), Patagonia. J. Quat. Sci. 25, 1063–1075 (2010).

Lozano, J. G., Bran, D. M., Lodolo, E., Tassone, A. & Vilas, J. F. Holocene seismic stratigraphy of the southern arms of Lago Argentino. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 111, 103495 (2021).

Powell, R. D. & Cooper, J. M. A glacial sequence stratigraphic model for temperate, glaciated continental shelves. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 203, 215–244 (2002).

Montelli, A. et al. Late Quaternary glacial dynamics and sedimentation variability in the Bering Trough, Gulf of Alaska. Geology 45, 251–254 (2017).

Hogan, K. A. et al. Glacial sedimentation, fluxes and erosion rates associated with ice retreat in petermann fjord and nares strait, north-west greenland. The Cryosphere 14, 261–286 (2020).

Bennett, M. R. The morphology, structural evolution and significance of push moraines. Earth-Sci. Rev. 53, 197–236 (2001).

Vaughan-Hirsch, D. P. & Phillips, E. R. Mid-Pleistocene thin-skinned glaciotectonic thrusting of the Aberdeen Ground Formation, Central Graben region, central North Sea. J. Quat. Sci. 32, 196–212 (2017).

Benn, D. & Evans, D. J. Glaciers and Glaciation (Routledge, 2010).

Kaplan, M. R. et al. Patagonian and southern South Atlantic view of Holocene climate. Quat. Sci. Rev. 141, 112–125 (2016).

Strelin, J. A. & Malagnino, E. C. Glaciaciones pleistocenas del Lago Argentino y alto valle del Río Santa Cruz. In XIII Congreso Geológico Argentino, vol. 4, 311–325 (1996).

Lønne, I. & Syvitski, J. Effects of the readvance of an ice margin on the seismic character of the underlying sediment. Mar. Geol. 143, 81–102 (1997).

Lønne, I. & Nemec, W. The kinematics of ancient tidewater ice margins: Criteria for recognition from grounding-line moraines. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 354, 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP354.4 (2011).

López-Martínez, J., Rivera, J., Dowdeswell, J. & Acosta, J. Giant ploughmarks on the South Patagonian continental margin produced by Antarctic icebergs. Geol. Soc. Lond. Mem. 46, 273–274 (2016).

Pedersen, S. A. S. Superimposed deformation in glaciotectonics. Bull. Geol. Soc. Den. 46, 125–144 (2000).

Boulton, G. et al. Till and moraine emplacement in a deforming bed surge–an example from a marine environment.. In Developments in Quaternary Sciences, vol. 4, 122–148 (Elsevier, 2004).

Boex, J. et al. Rapid thinning of the late Pleistocene Patagonian Ice Sheet followed migration of the Southern Westerlies. Sci. Rep. 3, 2118 (2013).

Moreno, P. I. et al. Radiocarbon chronology of the last glacial maximum and its termination in northwestern Patagonia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 122, 233–249 (2015).

Strelin, J. A. & Malagnino, E. C. Late-glacial history of Lago Argentino, Argentina, and age of the Puerto Bandera moraines. Quat. Res. 54, 339–347 (2000).

Minowa, M., Schaefer, M. & Skvarca, P. Effects of topography on dynamics and mass loss of lake-terminating glaciers in southern patagonia. J. Glaciol. 1–18 (2023).

Denton, G. H., Toucanne, S., Putnam, A. E., Barrell, D. J. & Russell, J. L. Heinrich summers. Quat. Sci. Rev. 295, 107750 (2022).

Fedotova, A. & Magnani, M. Glacial erosion rates since the last glacial maximum for the former argentino glacier and present-day upsala glacier, patagonia. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 129, e2024JF007960 (2024).

Cowan, E. A. et al. Fjords as temporary sediment traps: history of glacial erosion and deposition in Muir Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park, southeastern Alaska. Bulletin 122, 1067–1080 (2010).

Lozano, J. et al. Depositional setting of the southern arms of Lago Argentino (southern Patagonia). J. Maps 16, 324–334 (2020).

Magnani, M. B. Patagonia_GIA. https://doi.org/10.7914/qwde-1m47 (2019).

NASA & JPL. NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Global 3 arc second. Distributed by OpenTopography. Accessed: 2024-05-09 from https://doi.org/10.5067/MEaSUREs/SRTM/SRTMGL3.003 (2013).

Farr, T. G. & Kobrick, M. Shuttle Radar Topography Mission produces a wealth of data. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 81, 583–585 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our colleagues who made the acquisition of the data possible, including Pedro Skvarca, Luis Lenzano, the owner, the captain and the crew of the M/V Leal, Dana Peterson, Mason McPhail, Cesar Distante, Alejandro Tassone, Jorge Gabriel Lozano, and Donaldo Mauricio Bran. Discussions with colleagues of the GUANACO project (Emi Ito, Mark Shapley, Maximillian Van Wyk De Vries, and Matias Romero) and with Julia Smith Wellner improved the interpretation of the data. We acknowledge Halliburton and IHS/S&P Global for access to Seis-Space/ProMAX\(\textcircled {\hbox {R}}\) and Kingdom Software, respectively, used to process and interpret the data. Funding for this research was provided by NSF EAR award n.1714662 to M.B. Magnani.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by NSF EAR award n.1714662 to M.B. Magnani.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B.M. conceived the experiment, with conceptual contribution by A.F. Fieldwork was conducted by both authors. A.F. performed data analysis and interpretation under the supervision of M.B.M. A.F. wrote the initial draft and prepared figures. Both co-authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fedotova, A., Magnani, M.B. Subaqueous evidence of the last glacial maximum and its termination in southern Patagonia. Sci Rep 15, 30274 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14922-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14922-z