Abstract

Laser-plasma accelerators emerge as ultra-compact and versatile sources for numerous applications. Although the acceleration length is short (a few millimeters), they typically require large-scale infrastructures including ultra-high-power lasers, vacuum chambers and strict stability for temperature and humidity. As a result, most experiments are conducted in laboratories in large areas with controlled environments. Here, we present a highly compact (footprint of ~ 9 m²) and transportable system capable of generating electrons and photons in the MeV range at high repetition rates (up to 10 Hz) with average charge levels of 0.5 nC and up to 1 nC. This achievement shows the feasibility of performing laser-plasma acceleration outside of laboratory environments with a transportable system, significantly expanding the potential for practical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The acceleration of relativistic electron beams by lasers has attracted broad scientific interest in the past decades1,2,3. Among different approaches, Laser-Plasmas Accelerators (LPAs)4 stand out for their ability to produce electron beams with energy reaching hundreds of MeV or even GeV energies within mm to cm distances5,6,7,8,9,10. In LPAs, an ultrahigh peak power laser is focused to intensities of a few 1019 W.cm− 2 in a gas medium, which is instantaneously ionized. The laser rapidly expels electrons from the high-intensity region within a few optical cycles, while the much heavier ions remain stationary over such short timescales. This process leads to the formation of a plasma cavity, a region devoid of electrons, in the wake of the laser. In the wakefield regime, a periodic structure with a longitudinal electric field reaching hundreds of GV/m is formed, enabling the trapping and acceleration of some plasma electrons to ultra-relativistic energies within a sub-millimeter distance. As the plasma density increases, the wakefield structure gradually degrades until it is destroyed, leaving behind a long ion channel with transverse electric fields. Electrons from the background plasma may still gain energy from the ponderomotive force11, but they will not be accelerated as strongly as in the case of a wakefield or by Direct Laser Acceleration (DLA)12,13. However, low energy high charge electron beams obtained by ponderomotive force acceleration represent a strong interest in a broad range of X-ray imaging applications, such as cargo scanning, where activation of certain materials implies low energy limits. In this context, the pulse duration does not impose strict constraints and remains within the sub-nanosecond range. Moreover, the transverse size and high transverse momentum of the accelerated electrons are well suited for large-area irradiation14,15. In particular, for food irradiation, electron energies must remain below 10 MeV, regardless of the energy spread to prevent undesired nuclear activation of treated materials16.

In addition to its compactness, LPA offer several other advantages that make them appealing for applications. The source size is typically on the micrometer scale or smaller, the beam duration is ultra-short, on the order of a few to few tens fs17,18, and the system is highly versatile. For example, LPAs can produce ultrafast X-rays in the keV to MeV range19,20,21, they are inherently synchronized with intense laser pulses and enable flexible beam transport of the electron beam by moving the laser and the target rather than the electron beam itself. In particular, their micrometric source size makes LPAs ideal for enhancing resolution in industrial radiography and non-destructive testing22,23.

To produce an X-ray beam, the electron beam undergoes the bremsstrahlung process24 while passing through a high-Z metal converter. Obtaining a high-resolution quality image requires an X-ray source with both a small source size and a high photon flux. The flux is directly related to the charge of the electron beam. Because the electron source size is nearly point-like, the electron beam divergence and the distance, L, from the accelerator exit to the converter primarily determines the X-ray source size. However, the exact source size also depends on factors such as the electron energy and the thickness of the converter, which influence the electron scattering and X-ray emission profile25. The optimal electron source characteristics depend on the imaging requirements. For large objects with no fine defects to detect, highly divergent beams are ideal. However, detecting very small defects (< 0.5 mm) demands an electron source with high charge and low divergence. The challenge is that charge and divergence tend to increase together. Still, minimizing L is critical for improving image quality.

While optimizing the electron source is key to meeting imaging requirements, another major challenge for practical industrial applications is ensuring the system’s transportability. The ability to bring the accelerator to the object for radiography, rather than requiring the object to be transported to a large, fixed accelerator, is a critical step forward. In many practical imaging scenarios, especially for industrial or cultural heritage applications, the object to be radiographed cannot be moved easily. While the electron beam transport requires complex magnetic installations, transportation of the laser beam can be simply organized by compact optical elements and thus sufficiently reduces its manipulation, price and space requirements. Therefore, having a compact, transportable LPA source that can be deployed directly on-site represents a significant advance. Despite the short acceleration length of only a few millimeters, laser plasma acceleration relies on bulky components such as high-power lasers and vacuum chambers to transport the laser and enable the laser-plasma interaction. Additionally, the laser operation generally requires stable environmental conditions, which questions the deployment of such systems outside controlled laboratory settings.

Here we present a transportable system, with a compact, 9 m² footprint capable of generating electrons with a wide divergence (> 300 mrad) and photons in the MeV range, at a repetition rate of up to 10 Hz, delivering charge levels of 0.5 nC, in a non-controlled environment. This achievement demonstrates the feasibility of performing laser-plasma acceleration outside the laboratory, paving the way for a broad range of practical applications.

Experimental setup

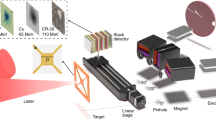

The experiments were performed using the 3 TW, 50 fs laser system “ENSTAmobile” (Amplitude Technologies) at the Laboratoire d’Optique Appliquée (LOA). Both the laser and the interaction chamber are independently transportable26. For this experiment, they were relocated to a radiation-protected room for safety purposes. The compact design of the accelerator results in a total footprint of less than 9 m² (see Fig. 1-(a)). The “ENSTAmobile” is a Ti: Sapphire Chirped Pulsed Amplification laser system with an optical compressor operating in air, most commonly used for studying laser filamentation27,28,29.

Compression in air rather than within a vacuum chamber, as is often the case for systems at this pulse energy and duration, reduces both the accelerator footprint and cost. However, to preserve the laser’s spatiotemporal properties, the distance between the compressor exit and the interaction chamber must be limited to approximately 2 m. Beyond this range, nonlinear propagation effects cause significant degradation.

The main laser beam delivers pulses with a maximum energy of 0.3 J, a pulse duration of 50 fs and a repetition rate of up to 10 Hz (see Methods). The beam enters the experimental chamber through a 4.5 mm thick borosilicate window. The dispersion introduced by this window is compensated by fine-tuning the compressor’s chirp. The beam is then focused on a nitrogen gas jet target by a 154 mm focal-length off-axis parabolic mirror (f/4). The focal spot, shown in Fig. 1-(b), was measured to be 5.5 μm Full-Width-at-Half-Maximum (FWHM) with 64% of laser energy contained in the first Airy disk. With a total pulse energy of up to 230 mJ, measured at the target, the estimated peak intensity in the focal plane in vacuum is 7.8 × \(\:{10}^{18}\:\text{W}.{\text{c}\text{m}}^{-2}\), corresponding to a normalized vector potential amplitude of \(\:{a}_{0}\approx\:1.9\). The supersonic gas jet, operated at the laser repetition rate, delivers pure Nitrogen through a 2 mm exit diameter nozzle (see Methods). The gas density profile was characterized offline, using a Mach-Zehnder-type interferometer30. During the interaction of the laser pulse with nitrogen gas, 5 electrons are ionized per atom, resulting in an electron density that is ten times the density of neutral atoms. This gives an electron density of the plateau on laser axis \(\:{n}_{e}\approx\:{1.96\times\:10}^{20}{\text{c}\text{m}}^{-3}\) for 70 bar backing pressure. The schematic of experimental setup and diagnostics is shown in Fig. 1-(b). A Beam Profile Monitor (BPM) and an electron spectrometer were used to characterize the electron beam’s charge and energy (see Methods). To generate an X-ray beam, a 0.7 mm-thick Tungsten (W) converter was inserted 5 mm after the gas jet exit. The converter is positioned with an angle of 45 °, giving an effective thickness of 1 mm. The generated photon beam was detected using an imaging plate placed on the laser axis after the vacuum chamber.

Results and discussions

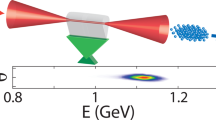

Typical results obtained with the electron diagnostics are shown in Fig. 2. The beam footprint measured on the BPM allows the determination of both the charge and divergence of the electron beam (Fig. 2-(a)). The average charge was 460 pC, with a Root-Mean-Square deviation (RMS) of 250 pC over 50 shots acquired at 1 Hz, as shown in Fig. 2-(c). Such strong fluctuations in charge most likely result from shot-to-shot variations in laser energy and wavefront distortions of the laser beam entering the plasma target, which affects the laser self-focusing and thus the peak intensity during the electron injection and acceleration process. The electron beam exhibits a high divergence, with a FWHM exceeding 300 mrad. The energy spectrum followed a Maxwellian distribution (Fig. 2-(b)) and demonstrated remarkable stability, with an average energy of 3.8 ± 0.3 MeV.

These results were obtained for a near-critical plasma density, \(\:{n}_{e}>{10}^{20}{cm}^{-3}\), which is higher than the typical value used in laser wakefield acceleration. This regime was intentionally chosen to obtain high charge beams with a wide divergence and < 10 MeV energy, tailored for radiography applications where imaging large objects with a millimetric resolution is required.

The charge is relatively low, compared to recent experiments conducted with similar laser energies11,31, due to lack of control over the laser beam profile in such a compact setup. Nevertheless, the average current can be increased by operating at a higher repetition rate of 10 Hz. As shown in Fig. 2-(c) the average charge per shot remains consistent at around 450 pC regardless of the repetition rate. Stability is comparable across both cases, as seen in Fig. 2-(c, d) with a RMS of 210 pC and approximately two-thirds of shots producing charges between 300 and 700 pC. The relatively low charge can thus be offset by higher repetition rates. Moreover, in both cases, the best shots yield charges exceeding 1 nC, indicating that average currents on the order of 10 nA could be achieved by an improved laser pulse profile. The laser energy jitter was measured to be 2.2% RMS over 100 shots at 10 Hz. The large shot-to-shot charge fluctuations are attributed to the specific acceleration mechanism at play, which relies on the continuous acceleration of electrons along the entire laser propagation path in the plasma11. This differs from the ideal laser wakefield acceleration scenario, where electrons are injected at a well-defined point near the plasma entrance. This continuous injection process makes the accelerated charge highly sensitive to nonlinear laser propagation effects. As a result, even small fluctuations in gas density, laser focus positioning, or pulse shape (including pedestal structure) can lead to large shot-to-shot variations in the injected charge. Improving the wavefront quality and overall spatio-temporal stability of the laser would thus enhance charge stability. Possible improvements include reducing propagation in air or using vacuum beam transport to preserve pulse quality, and applying adaptive optics (e.g., deformable mirrors) to correct wavefront distortions and pointing drift. These solutions could enhance charge stability, but at the cost of increased experimental complexity.

Following the optimization of the electron beam, the W plate was placed in the beam path to convert a portion of the electron beam energy into X-rays. A dipole magnet was used to deflect the electrons after passing through the converter (see Fig. 1-(b)). The resulting X-ray beam was directed toward two stainless-steel objects, a used tensile sample cylinder with a default and a plate with thickness incrementing in steps of 3 mm positioned outside the vacuum chamber, directly after the exit window (Fig. 3-(a)). The image was captured with an imaging plate by accumulating over 500 laser shots; the resulting radiograph is presented in Fig. 3-(b) (see Methods).

The cylinder and three steps corresponding to thicknesses of 18, 21 and 24 mm are clearly identifiable. Black regions represent high X-rays intensity, while gray areas represent low intensity. Additionally, a millimetric defect in the cylinder is discernible in the image. By analyzing the image and the varying thicknesses of the steps, it is possible to estimate the average energy range of the emitted photons.

To determine photon energies, the linear attenuation coefficient µ(E) was calculated using the NIST XCOM Database32 for a stainless-steel 316 L material without coherent scattering Fig. 3-(c). Incoherent attenuation, primarily dominated by Compton scattering, is used because it is significant at medium to high energy (10 keV to several MeV), which is more relevant for our study. This measurement provides only an approximate order of magnitude for the photon energy. To obtain more precise energy distribution, Monte Carlo simulations would be required33. Using the radiograph in Fig. 3-(b), we calculated the effective linear attenuation coefficient for the three thicknesses \(\:{\mu\:\left(E\right)}_{18mm}\), \(\:{\mu\:\left(E\right)}_{21mm}\) and \(\:{\mu\:\left(E\right)}_{24mm}\)(see Methods), and plotted these values in Fig. 3-(c) (orange, yellow and green lines). These lines intersect the attenuation curves in two energy ranges; the first between 1 and 10 MeV and the next between 20 and 100 MeV. The second energy range is excluded given the average electron energy of 3.8 MeV (Fig. 2-(b)), and that photons above this energy cannot result from the bremsstrahlung process. Focusing on the range between 1 and 10 MeV (zoomed region in Fig. 3-(c)), we estimate the average photon energies to lie between 1.2 and 2.5 MeV, which is consistent with the measured electron energies.

Conclusion and outlook

This study demonstrates the feasibility of a compact and transportable high-energy electron and photon source operating in the MeV range. A key advantage of this approach is its small footprint, which makes it particularly suitable for deployment outside traditional laboratory environments. The acceleration regime employed here is highly relevant for applications, offering a simple and robust method for generating high-energy electrons. Unlike other laser-plasma acceleration schemes, it does not require complex plasma sources, precise density tailoring, or sophisticated injection techniques, making it easier to implement and more scalable.

It is worth noting that bremsstrahlung emission inherently leads to X-ray beams with significant angular divergence due to multiple scattering in the converter34,35. In our configuration, the large divergence of the electron beam (~ 300 mrad) further increases the X-ray angular spread. While this may reduce the intensity per unit area, it can be advantageous for certain applications—such as radiography of large objects—where a wide field of view is required and high-sensitivity detectors can compensate for lower flux. For example, a highly divergent source can illuminate meter-scale objects at short distances, enabling compact and transportable system geometries. Conversely, for applications requiring high spatial resolution and less sensitive detectors, alternative acceleration schemes providing more collimated beams may be preferable.

While further improvements in charge and stability are necessary to meet industrial standards, these results open the door to practical implementations. The next step will be the deployment of this system in an industrial setting to perform high-resolution 3D tomography of relevant components36. Future developments may involve higher repetition rates (e.g., 100 Hz or more), which may require differential pumping to ensure proper vacuum levels37. In the longer term, optimizing laser parameters, improving beam transport, and integrating advanced detection methods could further enhance performance and broaden the range of potential applications, positioning laser-plasma accelerators as a compelling alternative to conventional sources.

Methods

Laser system

The commercial high-power Ti: Sa CPA laser system “ENSTAMobile” from Amplitude Technologies delivers 50 fs laser pulses with an energy of up to 300 mJ at a central wavelength of 800 nm and a repetition rate of 10 Hz. The system is installed on a movable enclosed platform with integrated climate control, regenerative cavity, two amplification stages and optical compressor operating in air. The size of the platform is 3.3 m x 1.4 m x 1.8 m (L x W x H), with a total weight of 1.3 T, allowing for easy transportation using a commercial forklift. The laser beam at the exit exhibits a top-hat spatial profile with a 40 mm diameter. It can propagate up to 2 m in air without significant degradation of its spatial and spectral properties.

Gas target

A 3D-printed plastic conical nozzle with a 1 mm throat diameter and a 2 mm exit diameter was attached to a Parker Series 9 pneumatic solenoid valve with a 0.79 mm orifice, achieving a Mach number > 3. The valve was operating with a 10 ms opening time. Pure Nitrogen gas at a backing pressure of up to 70 bar was used. The divergent part of the nozzle was shaped to generate supersonic circular symmetry shocks at the edges of the gas plume38.The electron density value at the plateau is \(\:{\varvec{n}}_{\varvec{e}}\approx\:{1.96\times\:10}^{20}{{cm}}^{-3}\) to reach \(\:{\varvec{n}}_{\varvec{e}}\approx\:{2.75\times\:10}^{20}{{cm}}^{-3}\) at the shocks.

Laser plasma accelerator (LPA)

The laser pulse, after travelling 1.8 m in air, enters the interaction vacuum chamber through a 4.5 mm thick borosilicate window. The interaction chamber is 610 mm x 750 mm x 600 mm large (L x W x H) and during the experiment was pumped using only a primary dry pump (Alcatel / Adixen ADS 602P) for 1 and 10 Hz. Reaching a maximum pressure of 10− 1 mbar (for 10 Hz) was sufficiently low to maintain proper laser propagation to the target and avoid unwanted effects of the residual gas on LPA.

A portion of the laser, leaking through the dielectric mirror, was used to provide a transverse optical probe for shadowgraph diagnostic of the plasma channel. The laser was focused on the gas target using an F/4 Off-Axis Parabolic mirror (OAP) with a 152 mm focal length. The average laser energy on target was 220–230 mJ on a daily base. The laser focal spot has 5.5 μm FWHM diameter and contains 64% of laser energy within the first Airy disk.

Electron beam diagnostics

The generated electron beam was characterised using a Beam Profile Monitor (BPM) and an electron spectrometer. The BPM consisted of an 80 mm diameter Carestream Lanex Regular scintillating screen, shielded on the front side with a 40 μm–thick aluminium foil to prevent damage from the laser beam. The acceptance angle of the BPM was 400 mrad. A calibrated photon source was attached to the BPM to provide precise charge calibration39. Sensitive side of the BPM, along with the calibration light source were imaged onto a 16-bit Hamamatsu CMOS camera.

The electron spectrometer consisted of two dipole magnets, each measuring 70 mm in length and 30 mm in width, combined to produce a uniform 0.3 T magnetic field, as measured by a Hall probe. A Lanex Regular scintillating screen was positioned within the gap between the two dipoles to capture the deflected electron beam and measure its energy distribution. The scintillating screen was imaged onto an 8-bit Basler CCD camera for energy spectrum analysis.

Both the BPM and the electron spectrometer were motorized, allowing for independent operation and precise positioning. During X-ray beam characterization, the dipole magnets were used to deflect the electron beam off-axis, preventing interference with image plate measurements.

X-ray beam diagnostic

To characterize the X-ray beam, a Fujifilm imaging plate (IP ST-VI) was installed on-axis, 10 cm downstream of the vacuum chamber window, see Fig. 3-(b). An image obtained by accumulating 500 shots was then read using a Typhoon FLA 7000 scanner at 25 μm resolution.

The energy of the photons was estimated using Eq. 140,41, with \(\:I\) and \(\:{I}_{0}\) extracted from the image in Fig. 3-(b) for 3 different thicknesses of the stainless steel sample (18, 21 and 24 mm). The linear attenuation coefficient \(\:\mu\:\left(E\right)\) was then calculated using the NIST XCOM Database32 for a stainless-steel 316 L material (Fe: 68.98%, Cr: 17%,Ni:12%,Mo: 2%,C: 0.02%) to estimate the photon energy (Fig. 3-(c)).

where \(\:\mu\:\left(E\right)\) is the linear attenuation, \(\:I\) is the intensity attenuated by the object, \(\:{I}_{0}\) is the initial intensity without attenuation and x is the material thickness.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Esarey, E., Sprangle, P. & Krall, J. Laser acceleration of electrons in vacuum. Phys. Rev. E 52, 5443–5453. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.52.5443 (1995).

Esarey, E., Schroeder, C. B. & Leemans, W. P. Physics of laser-driven plasma-based electron accelerators, Rev. Mod. Phys. 81 (3), 1229–1285. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.81.1229 (2009).

England, R. J. et al. Dielectric laser accelerators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86 (4), 1337–1389 (2014).

Tajima, T. & Dawson, J. M. Laser electron accelerator, Phys. Rev. Lett. 43 (4), 267–270. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.43.267 (1979).

Faure, J. et al. A laser-plasma accelerator producing monoenergetic electron beams. Nature 431 (7008), 541–544 (2004).

Geddes, C. G. R. et al. High-quality electron beams from a laser Wakefield accelerator using plasma-channel guiding. Nature 431 (7008), 538–541 (2004).

Mangles, S. P. D. et al. Monoenergetic beams of relativistic electrons from intense laser-plasma interactions. Nature 431 (7008), 535–538 (2004).

Leemans, W. P. et al. GeV electron beams from a centimetre-scale accelerator, Nat. Phys. 2 (10), 696–699. https://www.nature.com/articles/nphys418 (2006).

Oubrerie, K. et al. Controlled acceleration of GeV electron beams in an all-optical plasma waveguide. Light: Sci. Appl. 11 (1), 180 (2022).

Gonsalves, A. J. et al. Petawatt laser guiding and electron beam acceleration to 8 GeV in a laser-heated capillary discharge waveguide, Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 084801. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.084801 (2019).

Martelli, L. et al. Physics of high-charge laser-plasma accelerators for few-mev applications. Phys. Rev. Appl. 23 (3), 034033 (2025).

Pukhov, A., Sheng, Z. M. & Meyer-ter Vehn, J. Particle acceleration in relativistic laser channels. Phys. Plasmas. 6 (7), 2847–2854 (1999).

Shaw, J. et al. Role of direct laser acceleration in energy gained by electrons in a laser Wakefield accelerator with ionization injection. Plasma Phys. Controlled Fusion. 56 (8), 084006 (2014).

Sheng, Z. M. et al. Stochastic heating and acceleration of electrons in colliding laser fields in plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88 (5), 055004 (2002).

Malka, V. et al. Principles and applications of compact laser–plasma accelerators. Nat. Phys. 4 (6), 447–453 (2008).

Ravindran, R. & Jaiswal, A. K. Wholesomeness and safety aspects of irradiated foods. Food Chem. 285, 363–368 (2019).

Faure, J. et al. Controlled injection and acceleration of electrons in plasma Wakefields by colliding laser pulses. Nature 444 (7120), 737–739 (2006).

Lundh, O. et al. Few femtosecond, few Kiloampere electron bunch produced by a laser-plasma accelerator. Nat. Phys. 7 (3), 219–222 (2011).

Rousse, A. et al. Production of a KeV x-ray beam from synchrotron radiation in relativistic laser-plasma interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93 (13), 135005 (2004).

Ta Phuoc, K. et al. All-optical Compton gamma-ray source. Nat. Photonics. 6 (5), 308–311 (2012).

Powers, N. D. et al. Quasi-monoenergetic and tunable X-rays from a laser-driven Compton light source. Nat. Photonics. 8, 28–31 (2014).

Glinec, Y. et al. High-resolution γ-ray radiography produced by a laser-plasma driven electron source, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 025003. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.025003 (2005).

Ben-Ismaïl, A. et al. Compact and high-quality gamma-ray source applied to 10 micrometer-range resolution radiography, Appl. Phys. Lett. 98 (26), 264101. http://link.aip.org/link/?APL/98/264101/1 (2011).

Nakel, W. The elementary process of Bremsstrahlung. Phys. Rep. 243 (6), 317–353 (1994).

Khan, F. M. & Gibbons, J. P. Khan’s the Physics of Radiation Therapy (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014).

Sourcelab https://www.sourcelab-plasma.com

Houard, A., Pellet, M., André, Y. B. & Mysyrowicz, A. Décharge Électrique À Fort Courant Induite Dans L’air Par Filamentation Laser (Ed. Techniques Ingénieur, 2008).

Arantchouk, L. et al. A simple high-voltage high current spark gap with subnanosecond jitter triggered by femtosecond laser filamentation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 16 (2013).

Brelet, Y. et al. Underwater acoustic signals induced by intense ultrashort laser pulse. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 137 (4), EL288–EL292 (2015).

Zetie, K., Adams, S. & Tocknell, R. How does a Mach-Zehnder interferometer work? Phys. Educ. 35 (1), 46 (2000).

Feng, J. et al. Laser plasma-accelerated ultra-intense electron beam for efficiently exciting nuclear isomers. Laser Photonics Rev. 17 (12), 2300514 (2023).

Nist xcom database. Photon cross section database (version 1.2). http://physics.nist.gov/xcom

Tavana, P. et al. Ultra-high efficiency Bremsstrahlung production in the interaction of direct laser-accelerated electrons with high-z material. Front. Phys. 11, 1178967 (2023).

Sawkey, D. & Faddegon, B. Determination of electron energy, spectral width, and beam divergence at the exit window for clinical megavoltage x-ray beams. Med. Phys. 36 (3), 698–707 (2009).

Lemos, N. et al. Bremsstrahlung hard x-ray source driven by an electron beam from a self-modulated laser Wakefield accelerator. Plasma Phys. Controlled Fusion. 60 (5), 054008 (2018).

Withers, P. J. et al. X-ray computed tomography. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 1 (1), 18 (2021).

Monzac, J. et al. Differential pumping for khz operation of a laser Wakefield accelerator based on a continuously flowing hydrogen gas jet. Review Sci. Instrum. 96, 4 (2025).

Rovige, L. et al. Symmetric and asymmetric shocked gas jets for laser-plasma experiments. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 92, 8 (2021).

Kurz, T. et al. Calibration and cross-laboratory implementation of scintillating screens for electron bunch charge determination. Review Sci. Instrum. 89, 9 (2018).

McAlister, D. R. Gamma ray Attenuation properties of common shielding materials. University Lane Lisle USA (2012).

Grodstein, G. W. X-ray attenuation coefficients from 10 keV to 100 MeV (US Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards, 1957).

Acknowledgements

The work was partially supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement n°101020100 (Multiscan 3D) and by Agence de l’Innovation de Défense – AID - via Centre Interdisciplinaire d’Etudes pour la Défense et la Sécurité – CIEDS - (project 2021 – TECHLPX).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.M. ,O.K. and C.T. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morel, E., Kononenko, O., Wheeler, J. et al. A transportable laser-plasma accelerator in the MeV range. Sci Rep 15, 29008 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14967-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14967-0