Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic presents a spectrum of clinical outcomes ranging from respiratory conditions to cardiovascular complications that challenge management and resource allocation. Identification of early predictive biomarkers that are easy to detect is a priority to optimize medical care and resources. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 have received special attention due to their role in viral infectivity but also due to their physiological anti-inflammatory activities. CD15 and CD45 are key proteins in the immune response also associated with SARS-CoV-2 response. This study focused on analyzing the expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2, CD15, and CD45 in a cohort of 216 patients (111 mild and 105 severe disease) to ascertain their potential as biomarkers for predicting disease severity. We aimed to assess the correlation between these markers and the severity of symptoms, utilizing qPCR and flow cytometry. We used mixed-effects linear regression models and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves to test the performance of the biomarkers in the prediction of the severity of the disease. Significant lower surface expression of CD15 and ACE2 was observed in severe cases in addition to a strong association between aging and the severity of the disease. By integrating these findings, we developed a predictive model achieving 92.9% specificity and 79.3% sensitivity (AUC = 0.91; 95% CI: 0.87–0.96). The study concludes that our combined biomarker model could significantly enhance the management of COVID-19 by enabling early identification of patients at risk for severe outcomes, thus improving treatment strategies and resource distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 is an acute respiratory disease caused by an infection of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Frequently, the disease is asymptomatic, or patients manifest mild symptoms including cough, fever, muscle pain and shortness of breath. However, about 10 to 15% of patients develop severe symptoms which require intensive care due to respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological complications1. The sudden outbreak of COVID-19 cases challenged the healthcare systems worldwide in 2020 but still today COVID-19 is a threat to hospital capacity as manifested by the wave of 44 million new cases reported in a week by the end of 20232.

Despite extensive research efforts, early identification of individuals at risk of severe disease remains suboptimal, highlighting the urgent need for reliable, easily detectable biomarkers. Other studies have assessed the capacity of several biomarkers in the prognosis of COVID-19, with predictive models displaying good predictive performance3. However, these approaches have predominantly focused on circulating biomarkers or routine hematologic parameters, while largely overlooking membrane-bound markers on immune cells which may offer complementary insights into host–virus interactions and the regulation of immune responses4. Two key membrane proteins, Transmembrane Serine Protease 2 (TMPRSS2) and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2), which play crucial roles in viral entry, have primarily been studied in the context of the respiratory track and COVID-19 infectivity. TMPRSS2 primes the viral spike protein, facilitating fusion of the virus with host cell membranes, while ACE2 serves as the primary receptor for the virus5,6,7,8. The interaction between these proteins not only contributes to the virus’s infectivity but could also influence disease severity6. ACE2 is ubiquitously expressed in endothelial cells, especially in lung tissue9. It has been linked to an imbalance in the inflammatory response, particularly through the dysregulation of the ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis. This imbalance can lead to excessive cytokine release and a hyperinflammatory state, characteristic of severe COVID-19 cases9,10. Genetic polymorphisms and methylation patterns in TMPRSS2 and related genes, such as MX1, have been associated with more severe cases of the disease11,12. Given the importance of these proteins in viral entry and immune modulation, they have become primary targets for potential therapeutic intervention, highlighting the importance of understanding TMPRSS2 and ACE2 in shaping the immune response to SARS-CoV-213. However, the interplay between these proteins and immune cell dynamics in severe COVID-19 cases remains inadequately explored.

In terms of defense against the virus, neutrophil migration is critical in COVID-19 infections because these cells play a fundamental role in the innate immune response against pathogens. Neutrophils are among the first immune cells to arrive at infection sites, where they perform essential functions such as phagocytosis of pathogens, release of antimicrobial peptides, and production of reactive oxygen species to eliminate invaders. Efficient neutrophil recruitment to the lungs and other affected tissues is crucial for controlling and clearing SARS-CoV-2 infections14. However, in severe COVID-19 cases, impaired neutrophil migration can lead to inadequate viral clearance and excessive inflammation, contributing to the pathogenesis of acute respiratory distress syndrome and other severe complications. Understanding the mechanisms that enhance or inhibit neutrophil migration can help in developing strategies to modulate the immune response, potentially reducing the severity of COVID-19. Thus, studying CD15, an antigen involved in the migration of neutrophils to infection sites, alongside CD45, a pan-leukocyte marker expressed universally on leukocytes, can provide a broader understanding of immune cell dynamics and functions during SARS-CoV-2 infection15.

A deeper understanding of the previously mentioned markers is necessary to improve risk stratification and guide future research on immune response mechanisms in severe COVID-19 cases. This study focuses on a follow-up cohort of patients with varying COVID-19 severity to investigate the population of CD15+ and CD45+ cells in their blood, alongside the leukocytic expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2. By employing flow cytometry and quantitative PCR (qPCR), we aim to identify biomarkers that can predict disease progression. Understanding the roles of these markers in immune regulation and their potential as therapeutic targets could improve strategies for managing severe COVID-19 cases.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between 2020 and 2021, a total of 216 patients from Iberian populations in Spain who tested positive for COVID-19 were recruited to participate in this study at Hospital Virgen de las Nieves (Granada, Spain). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by positive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or by positive IgM antibody test and at the same timeline after COVID-19 recovery. Data collected included clinical variables (ferritin, D-dimer, CRP, troponin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)), symptoms (fever, anosmia, asthenia, dyspnea, long COVID, etc.), and intensive care unit (ICU) clinical follow-up (need for assisted ventilation, pneumonia, etc.). Patients were classified according to their symptoms in either severe disease group or mild disease group. Inclusion criteria for the severe disease group includes: (i) hypoxia with peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≤ 93% or partial pressure of oxygen/inspired oxygen fraction (PaO2/FiO2) < 300 mmHg; (ii) respiratory rate (RR) ≥ 30 breaths/min; or (iii) ICU admission. The inclusion criteria for the mild group were (i) SpO2 > 93%; (ii) the presence of nonspecific symptoms such as fever, fatigue, cough, or muscle pain, without hospitalization; or (iii) imperceptible symptoms during infection. Treatment varied due to the emerging evidence at the time and included medications such as glucocorticoids, antiretrovirals, antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and antipyretics. The absence of standardized treatment protocols led to high variability in management, which was not accounted for in the inclusion/exclusion criteria or further analyses.

Sample collection

Peripheral blood tubes collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and Tempus™ RNA tubes were obtained from each patient. Samples were processed in the subsequent 4–6 h after collection. 700 µl of blood collected in EDTA tubes was fixed with 1 ml of Proteomic Stabilizer PROT1 (Smart Tube Inc., San Carlos, CA, USA). The mixture was incubated for 10 min at room temperature (RT) and then frozen at −80 °C until used. Tempus RNA tubes were frozen at −80 °C until used.

RNA extraction

Total RNA from Tempus™ Blood RNA tubes were extracted using Tempus™ Spin RNA Isolation Kit protocol (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration was measured using the Nanodrop 2000 system (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Sample quality was assessed ensuring a A280/A260 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0. Extracted RNA was frozen at −80 °C until further analysis.

Reverse transcription PCR and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

RNA reverse transcription was performed using PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara Bio, JP) following manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed with TaqMan™ gene expression assays (Thermofisher, USA) for: ACE2 (Assay ID: Hs01085333_m1) and TMPRSS2 (Assay ID: Hs01122322_m1) on a 96-wells plate with QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). qPCR reactions were performed as follows: 95 °C during 10 min for enzyme activation; followed by 45 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C for denaturing and annealing/extension. All samples were run in triplicates, with a non-template control in each plate. Threshold cycles (Ct) ≥ 35 were considered undetermined values. mRNAs expression levels were quantified using the comparative threshold cycle method (2 − ΔΔCt) relative to HPRT1 (hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1) expression as an endogenous control. Relative quantification parameter (RQ or 2 − ΔΔCt) was estimated for each case and used in statistical analysis.

Flow cytometry sample processing and data acquisition

Thawing of the samples was performed at 4 °C on a roller at 40 rpm for 1 h. Red blood cells were lysed by adding 13 ml of Thaw-Lysis Buffer 1X (Smart Tube Inc., San Carlos, CA, USA) and incubating the samples for 20 min at RT on a roller. Then, samples were filtered through a 100 μm pluriStrainer (pluriSelect Life Science, Leipzig, DE) and pelleted for 10 min at 800 g and 4 °C. White blood cells were washed in 2 ml of Maxpar® Cell Staining Buffer (CST) (Fluidigm, San Francisco, CA, USA), centrifuged 5 min at 800 g and 4 °C and resuspended in 2 ml of CST. 250,000 cells were transferred onto a new tube, pelleted and resuspended in 30 µl of CST. Fc receptors were blocked by incubating the samples with 1 µl of Fc blocking agent (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for 30 min at 4 °C. Next, 2 ml of CST was added, and the blocking agent was washed out. Cells were resuspended in 100 µl and stained with conjugated primary mouse antibodies against anti-human CD15, CD45, ACE2 and TMPRSS2 at a 1:50 dilution (for antibodies details see Supplementary Material Table 1) for 30 min at RT. Fluorescence minus one control were also prepared for each marker. Then, the antibody cocktail was washed with 2 ml CST and resuspended the stained cells in 200 µl of CST. Data was acquired using FACSCanto II cytometer (BD biosciences) equipped with violet, blue and red lasers emitting at 405 nm, 488 nm and 633 nm respectively. Fluorescence minus one control samples were introduced in every batch.

Flow cytometry data analysis

Data were analyzed using FloJo version 10. Compensations were calculated using fluorescence minus one control. Live cells were gated on the FCS-A, SSC-A plot, singlets were selected based on the FSC-A, FSC-H plot. CD15 + and CD45 + gates were set using their respective FMOs as negative control. Expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 was assessed separately on the live/singlet/CD15+/CD45 + populations (for gating details see Supplementary Material Fig. 1). Median Fluorescence Intensity (MedFI) was then calculated and the difference between each sample divided by the MedFI of the FMO was used for further analysis.

Statistical analyses

We first examined the differences in ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression between the disease groups measured by qPCR and the surface expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in CD15+ and CD45+ cells measured by flow cytometry. Samples with non-detectable expression were excluded from these analyses. Outliers were removed using the ROUT method (Q = 1%). Comparison between the disease groups were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed Welch’s t-test, since the variants of the two groups were different. p values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Next, the whole dataset was used to assess the correlation between qPCR and flow cytometry data of ACE2 and TMPRSS2. Correlation between the two continuous variables was assessed using generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood accounting for the variability due to the batch effect. We then used this method to build univariable models to test the association between disease severity and the different variables. Finally, we built a multivariable model following this procedure: disease was treated as the dependent variable, while all other variables (age, MedFI CD15, MedFI ACE2, MedFI TMPRSS2, sex, and MedFI CD45) were considered independent variables. These independent variables were included in nested models as fixed factors, while batch was included as a random factor. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves (ROC curves) were generated to test the performance of the different models. Statistical analyses were performed with the software GraphPad Prism 8 and R version 4.3.3; using lme4, GGally, pROC, performance and ggplot2 packages.

Results

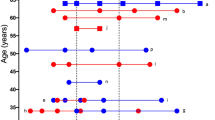

A total of 216 patients were recruited to participate in this study, 111 were classified in the group of mild disease (51.4%) and 105 as severe disease (48.6%). Descriptive information about the population can be found in Table 1. While there was no statistical difference in the number of females and males in each group, we observed a significant increase in age in the severe group in comparison to the mild group.

ACE2 and TMPRSS2 show low expression in blood of COVID-19 patients

The expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in blood of COVID-19 patients was studied in our population by qPCR. ACE2 was detected in 99 samples, 78 in the mild group and 21 in the severe disease group. TMPRSS2 was detected in 37 samples, 29 in the mild group and 8 in the severe group. Both markers show low blood expression. Statistical analysis revealed no significant difference in the expression of these markers in patients with different COVID-19 severity (ACE2: difference between means ± SEM = −0.081 ± 0.116, 95% CI [−0.316, 0.155], p = 0.4911; TMPRSS2: 0.235 ± 0.157, 95% CI [−0.114, 0.584], p = 0.1653) (Fig. 1).

Expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in COVID-19 patients. ACE2 n = 99 (mild: 0.694 ± 0.468; severe: 0.614 ± 0.470), TMPRSS2 n = 37 (mild: 0.649 ± 0.353; severe: 0.884 ± 0.404). Data is reported as mean ± SD. Data in the graphs is shown as 2 -ΔΔCt mean. Each dot represents the average expression in a sample run in triplicates. ns = not significant.

CD15, CD45 and ACE2 are differentially expressed in blood of COVID-19 patients

Out of the 216 samples, 166 successfully overcame flow cytometry sample processing while 50 samples showed a high degree of coagulation and degradation. CD15 expression was significantly reduced in patients experiencing severe disease (mean MedFI ± SD: 9.216 ± 6.130 vs. 5.233 ± 2.168; 95% CI [−5.302, −2.664]; p < 0.0001). We found low expression of CD45 (mean MedFI ± SD: 1.358 ± 0.418), ACE2 (mean MedFI ± SD: 1.171 ± 0.367) and TMPRSS2 (mean MedFI ± SD: 1.292 ± 0.181), in line with our previous qPCR observations. CD45 was slightly overexpressed in severe patients (mean MedFI ± SD: 1.289 ± 0.399 vs. 1.442 ± 0.367; 95% CI [0.032, 0.273]; p = 0.0137) while ACE2 expression was significantly reduced in blood of severe COVID-19 patients (mean MedFI ± SD: 1.289 ± 0.350 vs. 0.854 ± 0.138; 95% CI [−0.435, 0.039]; p < 0.0001). There was no statistically significant difference in the expression of TMPRSS2 between these groups (mean MedFI ± SD: 1.280 ± 0.186 vs. 1.309 ± 0.131; 95% CI [−0.020, 0.078]; p = 0.2402) (Fig. 2).

Expression of CD15, CD45, ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in blood of patients with COVID-19. Data is represented as normalized values using their respective FMOs. CD15 expression is significantly reduced in severe patients (9.216 ± 6.130 vs. 5.233 ± 2.168), as well as ACE2 (1.289 ± 0.350 vs. 0.854 ± 0.138). CD45 is slightly increased in severe patients (1.289 ± 0.399 vs. 1.442 ± 0.367). There is no difference in the expression of TMPRSS2 (1.280 ± 0.186 vs. 1.309 ± 0.131). Each dot represents a sample. Welch’s t-test, ns = not significant.

ACE2 mRNA levels and protein expression show a positive correlation in blood of COVID-19 patients

We next studied the association between mRNA levels and protein expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2. TMPRSS2 was only detected in 37 samples by qPCR which prevented performing a reliable statistical test and motivated the omission of this variable from further analyses. The results of the mixed effects linear regression model (Table 2) show a positive correlation between the expression of ACE2 measured by the two methods. An increase of one unit in ACE2 MedFI led to an average increase of 0.47 in qPCR values (t value = 3.046).

Adding the sex variable to the model (Table 3) changes the ACE2 MedFI estimate by less than 10% but significantly increases the statistical significance of the association (t-value = 4.603). Interestingly, this model shows a statistically significant lower correlation of ACE2 values detected in men compared to women.

Reduced expression of CD15 and ACE2 in blood is associated with severe disease

To identify potential biomarkers for predicting COVID-19 severity, we performed univariate analyses on surface markers and clinical parameters. The analysis utilized a generalized linear mixed-effects model, with the outcome variable being disease severity (severe vs. mild). The results obtained for each marker are shown in Table 4. The univariate analysis identified CD15 and ACE2 as significant predictors of severe COVID-19, both showing an inverse relationship with disease severity (p < 0.05). TMPRSS2 displays an estimate of considerable effect, however, it shows high variability (Std. Error: 1.3510), limiting its statistical significance in the current study. As expected, age was a highly significant predictor, positively associated with severe disease (p < 0.001).

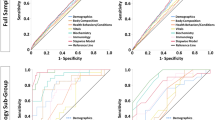

A model including age, CD15 and ACE2 expression effectively identifies severe patients

We then aimed to develop a model that could help us discern between mild and severe disease combining the information of the potential biomarkers. Since the variables CD15, ACE2, and age were found to be significant in the univariate analyses, we used the model incorporating these three markers as the starting point for model development. All variables were considered independent, and nested models were built and tested for their performance. The nested models generated by adding the remaining variables did not show a significant improvement over the initial model (Table 5), with chi-squared values greater than 0.05 in all cases. Details on diagnostic testing can be found in Supplementary Material Figure S2.

To assess the discriminatory ability of the model, a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was generated (Fig. 3). This curve demonstrates excellent predictive performance, with an AUC of 0.91, indicating that the model can effectively distinguish between positive and negative cases. Additionally, it shows very good sensitivity (0.793) and excellent specificity (0.929).

Discussion

The variability in COVID-19 progression, from asymptomatic to critical, makes early detection of severe cases essential for improving clinical outcomes and resource allocation. Identifying biomarkers that can predict disease severity would allow for tailored treatments, timely intervention, and a more effective use of healthcare resource16. In this work, we assessed the expression of CD15, CD45, ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in the blood of patients with COVID-19 as candidate biomarkers to discriminate mild from severe cases. Combining age, CD15 and ACE2 expression, we have built a model capable of discerning mild from severe phenotypes with a 92.9% specificity and 79.3% sensibility.

Our results highlight age as the variable with the highest influence in determining disease severity. As reported by other authors, age is a significant risk factor for severe COVID-19 due to several biological and immunological reasons17,18. As people age, their immune system typically undergoes a decline, a process known as immunosenescence, which reduces the body’s ability to respond to infections effectively19. Previous work in our group demonstrates that patients younger than 55 years old with poor disease outcome display a compromised immune system, in terms of reduced TCR repertoire, which is similar to older patients regardless of their COVID-19 prognosis20. Moreover, the higher prevalence of chronic diseases in the elderly further compromises the immune system response against the virus21.

In this work, two key markers of blood cells are proposed as candidate biomarkers of the severity of COVID-19. On the one hand, CD15 is a vital marker in COVID-19 research due to its role in directing neutrophils to infection sites, a critical aspect of the body’s initial immune response. Our research has demonstrated a significant reduction of CD15 in patients with severe COVID-19, suggesting a compromise in this essential immune function. Reduced CD15 expression may impair neutrophil migration to infected tissues, possibly resulting in an insufficient immune response and unchecked viral proliferation. This dysfunction could exacerbate disease severity and worsen outcomes, as previous studies have demonstrated22. Our findings align with other studies which also observed low CD15 levels in acute COVID-19 cases1,23. Additionally, our results indicate that CD15 expression levels in blood may serve as a valuable indicator of disease severity, highlighting the importance of immune cell dynamics in managing severe COVID-19. On the other hand, CD45 expression appeared elevated in severe COVID-19 patients in both our study and previous findings in Indian cohorts; however, after batch correction, the differences in our data were not statistically significant24. Thus, further studies will be needed to strengthen current evidence.

ACE2 has been extensively studied in its relationship to COVID-19 susceptibility; particularly in nasal epithelium and lung tissue25. This protein shows lower expression levels in blood than other tissues such as those of the respiratory tract or the cardiovascular system. We show that ACE2 is detectable in blood cells both by qPCR and flow cytometry. Despite its low expression level, our data show that ACE2 expression is significantly higher in patients with mild disease than in those with severe disease. Similar results have been reported by Goonewardena et al., who recently found differential expression of ACE2 in blood of mild and severe COVID-19 patient26. Moreover, a study on the susceptibility of highly exposed individuals indicated that subjects with lower ACE2 expression were more likely to get infected than those with higher ACE2 levels27,28. Indeed, previous studies have reported significantly lower levels of ACE2 expression in monocytes, suggesting that higher levels of ACE2 expression are associated with a certain innate resistance to infection29,30. These results align with the findings presented in this study. The correlated decrease in both qPCR and flow cytometry ACE2 levels in severe patients suggests that the downregulation of ACE2 at the RNA level is effectively translated to the protein level on the cell surface. Such a decrease could directly impact on the inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2. ACE2 counteracts the proinflammatory effect of the renin-angiotensin system by converting Ang I in Ang 1–9 and Ang II in Ang 1–7. The lower expression of ACE2 in severe patients could restrict the anti-inflammatory effects of the ACE2/Ang 1–7 thus promoting the pathophysiological effects of COVID-199,31,32. Therefore, inhibition of the protective effect of ACE2 could promote the proinflammatory and thrombotic scenario observed in severe patients.

Another key protein in viral infectivity is TMPRSS2. This protein has been widely studied in cells of the respiratory tract due to its key role in viral infection6. However, scRNA-seq studies in multiple tissues suggest that TMPRSS2 exhibits a broad gene expression, even more than ACE2, indicating that ACE2, rather than TMPRSS2, may be a limiting factor for viral entry in the initial stages of infection33. The negligible expression of TMPRSS2 and ACE2 in blood cells even arose a debate on the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs). Interestingly, a study by Yao et al. showed that circulating blood cells can express both proteins upon activation, that TMPRSS2 is only observed in monocytes and that cells co-expressing ACE2 and TMPRSS2 were infected by SARS-CoV-234. Other authors have also reported an increased expression of TMPRSS2 in PBMCS from patients with severe COVID-1935. In this work, we could detect the expression of surface TMPRSS2 in CD15+ circulating blood cells, however, despite TMPRSS2 showing similar trends to previous work by other authors this marker failed to discern between the two different severity groups, which precluded its inclusion in the final model. This could be explained by the variability observed in the data and the reduced sample size of the severe cohort. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of this molecule as a biomarker.

This study presents several limitations. First, the limited sample size constrained our ability to generate a separate validation cohort without compromising the statistical power of our results, thus further studies in independent and larger cohorts are needed to improve the robustness of our findings. Second, our cohort primarily comprised individuals from Iberian populations in Spain. COVID-19 susceptibility has been shown to present disparities between ethnic groups, with polygenic risk scores showing association with higher infection risk and severity in White cohorts than Black or Asian groups36. Thus, the lack of ethnic variability might limit the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic groups. Given that diverse ethnic backgrounds can influence treatment response and disease outcomes, a more diverse cohort is necessary to extend the impact of our findings. Another important limitation is the variability in treatment regimes. The challenge posed by the sudden outburst of COVID-19 entailed a lack of standardized treatment and mostly a treatment regime shaped by the developing evidence at the time. The situation required repurposing a high variety of drugs used for other diseases especially antiviral agents, antimalarials, antiparasitic drugs and other immunomodulatory therapies37. In our cohort, treatment included glucocorticoids, antiretrovirals, antibiotics, immunosuppressants, antipyretics, and often combinations thereof. This heterogeneity may influence the expression of certain biomarkers; however, inconsistency and extent of variability precluded its inclusion as a controlled variable in this study.

The identification of CD15 and ACE2 as potential biomarkers for COVID-19 severity offers valuable clinical implications. CD15 levels in circulating blood cells provide insight into neutrophil functionality and immune response efficiency, which could aid in predicting disease progression and guiding therapeutic interventions. Similarly, the differential expression of ACE2 between mild and severe cases highlights its potential role not only in viral entry but also in modulating the inflammatory response and disease pathophysiology. Given their specificity and reliability, these biomarkers could serve as early indicators of disease severity, allowing for better patient stratification, risk assessment, and timely medical intervention. Similar reports highlighting the effectiveness of using molecular markers in COVID-19 management has been proven. For example, the use of molecular biomarkers (like complement 5a and ADAMTS13) for optimizing the success of treatment response in COVID-19 has been proven38. Or the use of radiotranscriptomic signature C19-RS, a marker of cytokine-driven inflammation driving systemic activation of coagulation and responsible for adverse clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients39. Combined with age, these markers form a predictive model with excellent accuracy. Specifically, this model can distinguish between disease severities with excellent specificity and high sensitivity, which may greatly enhance clinical decision-making. The potential societal impact of such a model is profound, as it could enable more personalized treatment plans, improve patient outcomes, reduce healthcare burdens by efficiently allocating resources, and potentially lowering transmission rates by timely identification and management of severe cases. This approach represents a significant step forward in the management and understanding of COVID-19 through biomarker research.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Shambat, S. M. et al. Hyperinflammatory environment drives dysfunctional myeloid cell effector response to bacterial challenge in COVID-19. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1010176. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PPAT.1010176 (2022).

COVID-19. Cases | WHO COVID-19 Dashboard.

Hernández-Monsalves, A. H. et al. A machine learning model for predicting intensive care unit admission in inpatients with COVID-19 using clinical data and laboratory biomarkers. Biomedicines 13, 1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13051025 (2025).

Gorgojo-Galindo, Ó. et al. Predictive modeling of poor outcome in severe COVID-19: A Single-Center observational study based on clinical, cytokine and laboratory profiles. J. Clin. Med. 10, 5431. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10225431 (2021).

Li, W. et al. Angiotensin-Converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426, 450–454. https://doi.org/10.1038/NATURE02145 (2003).

Matsuyama, S. et al. Enhanced isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by TMPRSS2-Expressing cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 7001–7003. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.2002589117 (2020).

Saengsiwaritt, W., Jittikoon, J., Chaikledkaew, U. & Udomsinprasert, W. Genetic polymorphisms of ACE1, ACE2, and TMPRSS2 associated with COVID-19 severity: A systematic review with Meta-Analysis. Rev. Med. Virol. 32 https://doi.org/10.1002/RMV.2323 (2022).

Zhou, P. et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable Bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41586-020-2012-7 (2020).

Zipeto, D., Palmeira, J. F., Argañaraz, G. A. & Argañaraz, E. R. ACE2/ADAM17/TMPRSS2 interplay May be the main risk factor for COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 11 https://doi.org/10.3389/FIMMU.2020.576745 (2020).

Bourgonje, A. R. et al. Angiotensin-Converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), SARS-CoV-2 and the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Pathol. 251, 228–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/PATH.5471 (2020).

Martinez-Diz, S. et al. Analyzing the role of ACE2, AR, MX1 and TMPRSS2 genetic markers for COVID-19 severity. Hum. Genomics. 17 https://doi.org/10.1186/S40246-023-00496-2 (2023).

Martínez-Gómez, L. E. et al. The fatal contribution of Serine Protease-Related genetic variants to COVID-19 outcomes. Front. Immunol. 15 https://doi.org/10.3389/FIMMU.2024.1335963 (2024).

Nejat, R., Torshizi, M. F., Najafi, D. J. S. & Protein ACE2 and host cell proteases in SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity; is soluble ACE2 a two blade sword?? A narrative review. Vaccines 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/VACCINES11020204 (2023).

Effah, C. Y. et al. Neutrophil-Dependent immunity during pulmonary infections and inflammations. Front. Immunol. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/FIMMU.2021.689866 (2021).

Rawat, S., Vrati, S. & Banerjee, A. Neutrophils at the crossroads of acute viral infections and severity. Mol. Aspects Med. 81 https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MAM.2021.100996 (2021).

Noviello, M. et al. The longitudinal characterization of immune responses in COVID-19 patients reveals novel prognostic signatures for disease severity, patients’ survival and long COVID. Front. Immunol. 15 https://doi.org/10.3389/FIMMU.2024.1381091 (2024).

Wanhella, K. J. & Fernandez-Patron, C. Biomarkers of ageing and frailty May predict COVID-19 severity. Ageing Res. Rev. 73, 101513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101513 (2022).

Cunha, L. L., Perazzio, S. F., Azzi, J., Cravedi, P. & Riella, L. V. Remodeling of the immune response with aging: Immunosenescence and its potential impact on COVID-19 immune response. Front. Immunol. 11, 1748. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01748 (2020).

Zinatizadeh, M. R. et al. Immunosenescence and Inflamm-Ageing in COVID-19. Ageing Res. Rev. 84, 101818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2022.101818 (2023).

Marín-Benesiu, F. et al. The T-Cell repertoire of Spanish patients with COVID-19 as a strategy to link T-Cell characteristics to the severity of the disease. Hum. Genomics. 18, 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-024-00654-0 (2024).

Moderbacher, C. R. et al. Antigen-Specific adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in acute COVID-19 and associations with age and disease severity. Cell 183, 996–1012e19. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CELL.2020.09.038 (2020).

Karawajczyk, M. et al. High expression of neutrophil and monocyte CD64 with simultaneous lack of upregulation of adhesion receptors CD11b, CD162, CD15, CD65 on neutrophils in severe COVID-19. Therapeutic Adv. Infect. Disease. 8 https://doi.org/10.1177/20499361211034065 (2021).

Hoffmann, J., Etati, R., Brendel, C., Neubauer, A. & Mack, E. The low expression of Fc-Gamma receptor III (CD16) and high expression of Fc-Gamma receptor I (CD64) on neutrophil granulocytes mark severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Diagnostics (Basel Switzerland). 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS12082010 (2022).

Chattopadhyay, P. et al. Single-Cell multiomics revealed the dynamics of antigen presentation, immune response and T cell activation in the COVID-19 positive and recovered individuals. Front. Immunol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/FIMMU.2022.1034159 (2022).

Patel, A. B. & Verma, A. Nasal ACE2 levels and COVID-19 in children. JAMA 323, 2386–2387. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.2020.8946 (2020).

Goonewardena, S. N. et al. Monocyte-Mediated thrombosis linked to Circulating tissue factor and immune paralysis in COVID-19. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 44, 1124–1134. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.122.318721 (2024).

Maza, M. et al. ACE2 serum levels as predictor of infectability and outcome in COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/FIMMU.2022.836516 (2022).

Shevchuk, O. et al. Blood ACE2 protein level correlates with COVID-19 severity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/IJMS241813957 (2023).

Osman, I. O. et al. Expression of ACE2, soluble ACE2, angiotensin I, angiotensin II and angiotensin-(1–7) is modulated in COVID-19 patients. Front. Immunol. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/FIMMU.2021.625732 (2021).

Zhang, D. et al. Frontline science: COVID-19 infection induces readily detectable morphologic and Inflammation-Related phenotypic changes in peripheral blood monocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 109, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/JLB.4HI0720-470R (2021).

Cuervo, N. Z. & Grandvaux, N. ACE2: evidence of role as entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2 and implications in comorbidities. eLife 9, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.7554/ELIFE.61390 (2020).

Swärd, P. et al. Age and sex differences in soluble ACE2 May give insights for COVID-19. Crit. Care. (London, England). 24 https://doi.org/10.1186/S13054-020-02942-2 (2020).

Sungnak, W., Huang, N., Bécavin, C., Berg, M. & Network, H.L.B. SARS-CoV-2 entry genes are most highly expressed in nasal goblet and ciliated cells within human airways. ArXiv 26, 681–687. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0868-6 (2020).

Yao, Y. et al. Surface translocation of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 upon TLR4/7/8 activation is required for SARS-CoV-2 infection in Circulating monocytes. Cell. Discovery. 8 https://doi.org/10.1038/S41421-022-00453-8 (2022).

Ghezelbash, B. et al. Correlation of expression of MMP-2, ACE2, and TMPRSS2 genes with lymphopenia for mild and severity of COVID-19. Iran. J. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 22, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijaai.v22i1.12011 (2023).

Farooqi, R., Kooner, J. S. & Zhang, W. Associations between polygenic risk score and Covid-19 susceptibility and severity across ethnic groups: UK biobank analysis. BMC Med. Genom. 16, 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-023-01584-x (2023).

Focosi, D., Franchini, M., Maggi, F. & Shoham, S. COVID-19 therapeutics. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 37, e00119–e00123. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00119-23 (2024).

Lim, E. H. T. et al. Anti-C5a antibody vilobelimab treatment and the effect on biomarkers of inflammation and coagulation in patients with severe COVID-19: A substudy of the phase 2 PANAMO trial. Respir Res. 23, 375. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02278-1 (2022).

Kotanidis, C. P. et al. Constructing Custom-Made radiotranscriptomic signatures of vascular inflammation from routine CT angiograms: A prospective outcomes validation study in COVID-19. Lancet Digit. Health. 4, e705–e716. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00132-7 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all donors, nurses and clinicians for making this study possible. We also want to thank the service of Statistics and Methodology Consulting of Fundación para la Investigación Biosanitaria de Andalucía Oriental (FIBAO), primarily Antonio Jesús Galvez Muñoz, for statistical counseling and performance of the statistical analyses. This article is part of the PhD project of Ana Pozo Agundo. This project is funded by "Desarrollo e Innovación (I+D+i) en Biomedicina y en Ciencias de la Salud en Andalucía, FEDER", internal code PECOVID-0006-2020; Secretaría General de Universidades, Investigación y Tecnología, Consejería de Salud, Junta de Andalucía, internal code CV20-36740; and by Secretaría General de Salud Pública e I+D+i en salud, Junta de Andalucía, internal code PIP-0043-2022.

Funding

This project is funded by "Desarrollo e Innovación (I+D+i) en Biomedicina y en Ciencias de la Salud en Andalucía, FEDER", internal code PECOVID-0006-2020; Secretaría General de Universidades, Investigación y Tecnología, Consejería de Salud, Junta de Andalucía, internal code CV20-36740; and by Secretaría General de Salud Pública e I+D+i en salud, Junta de Andalucía, internal code PIP-0043-2022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was initiated and designed by M.J.A-C. and L.J.M.-G. Patient recruitment and database curation was performed by V.A-R., S.M-D and C.M.M-A. Laboratory analyses were performed by S.C-L., A.P-A. and C.M.M-A. Data analysis was done by A.P-A and S.C-L. The first and following drafts were written by S.C-L and A.P-A and revised by S.M-D, M.J.A-C., L.J.M.-G and C.L.D-F; all authors revised and approved the final draft of the manuscript. A.P-A and S.C-L contributed equally to this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Author Sergio Cuenca-López is employed by LORGEN G.P. Ana Pozo-Agundo, Carmen María Morales-Álvarez, Verónica Arenas-Rodríguez, Silvia Martínez-Diz, Cristina Lucía Dávila-Fajardo, María Jesús Álvarez-Cubero and Luis Javier Martínez-González declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Granada Research Ethics Committee (REC)/REC on Medicinal Products (CEI-Granada) with internal code 1329-N-21. Patients and/or their relatives were informed about the aims and purpose of the project, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cuenca-López, S., Pozo-Agundo, A., Morales-Álvarez, C.M. et al. A model including CD15, ACE2 and age efficiently predicts COVID-19 severity. Sci Rep 15, 34163 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15033-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15033-5