Abstract

Across the United States, power grids are increasingly under strain from extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, high winds, and heavy precipitation, that result in frequent, long-duration and widespread power outages. The strain is intensified when these events are compounded, which amplifies their impact and exacerbates the risk of disruptions. To identify weather variables driving outages and cluster regions based on these variables, we employed a self-organizing map (SOM) approach using county-level outage data from 2015 to 2022, obtained using the U.S. Department of Energy’s EAGLE-I platform, and weather data from the ASOS weather station observations. The findings revealed substantial regional differences in outages resulting from variability in heat, wind, and precipitation. In California, for example, high heat coupled with strong wind gusts led to the most severe outages, while in Texas, the primary contributors were high heat followed by heavy precipitation. This research provides a nuanced understanding of weather-induced power outages, offering a data-driven approach for infrastructure planning and resilience efforts. This study underscores the crucial role of continental weather variability in shaping outage patterns and highlights the necessity for region-specific adaptation strategies to enhance grid resilience, considering the rise in heatwaves and compounding weather events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energy systems are significantly influenced by climate variability because both the demand for and supply of energy rely on atmospheric conditions occurring over various time scales, as well as on the effects of severe weather events1. In the United States alone, the annual cost of weather-related blackouts is estimated to range between $20 billion and $552,3,4. Previous research has indicated that these outages have become more frequent over time, and the increase is expected to continue because of extreme weather events2,5,6. Weather-driven outages have, thus, emerged as a critical issue, with cascading consequences for both human safety and economic stability7.

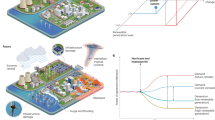

Extreme weather events frequently push natural and engineered systems to their limits. While devastating individually, their combined effects often act as critical tipping points, altering the stability and function of both natural and human systems8,9. Among the primary drivers of power outages, heatwaves, high winds, and heavy precipitation are particularly prominent, with their interaction presenting a compounded threat1,10,11,12. Extreme heat events alone can strain power grids by driving peak demand, reducing generation and transmission capacity, and lowering thermal tolerances in infrastructure, resulting in widespread energy deficits1,13,14. A power outage lasting eight hours or longer is nearly 52 times more likely to happen on a day with concurrent severe precipitation, unusual heat, and tropical storm winds than on days without such compounded weather events15. These events demonstrate how the interplay of temperature, wind, and precipitation magnifies risks to energy infrastructures, highlighting the complex challenges of ensuring grid resilience.

Despite significant progress in understanding individual weather phenomena, less attention has been paid to the ways in which the spatiotemporal interaction of these events influences outage risks. Current research often focuses on isolated case studies of outage events or limited regions, overlooking the broader geographical patterns of weather-driven outages across areas as large as the contiguous United States5. Furthermore, many studies were hindered by data limitations, such as low temporal and spatial resolution of weather and climate data, and the difficulty of obtaining detailed outage records from utility companies16. A unique opportunity to address these deficiencies is offered by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Environment for the Analysis of Geo Located Energy Information (EAGLE-I) platform, which collects outage data from utilities across the United States17,18.

Another key challenge to examining spatiotemporal variability of outage patterns is the difficulty in attributing outage events to specific weather drivers, particularly in the presence of multiple overlapping phenomena. Self-Organizing Maps (SOMs) provide a powerful tool for clustering and identifying patterns within complex, multidimensional datasets19. SOMs have been used extensively to analyze extreme climatic events, such as rainfall patterns and cloud categorization20,21,22. By condensing nonlinear interactions into actionable insights, this study employs SOMs to examine how compound weather phenomena, including heatwaves, winds, and heavy precipitation, induce critical customer outages across the contiguous United States.

The study leverages the EAGLE-I dataset, together with weather records from the National Weather Service, to identify the critical meteorological factors contributing to power disruptions through a two-tier approach: (1) devise an optimal methodology for identifying outages during concurrent heatwaves and extreme weather events; and (2) use these data to derive regional patterns in outage risks associated with concurrent heatwave/weather events-induced disruptions across the Energy Information Administration (EIA) balancing authority regions from 2015 to 2022.

Previous studies have largely focused on identifying outages occurring within specific utility regions. In contrast, this study takes a comprehensive approach, assessing the broader impact of heatwaves and their compounding effects across multiple regions to uncover national-scale patterns of grid vulnerability. Unlike prior research that focused on single-weather parameters within select areas, this study explores the interplay of diverse weather conditions that contribute to grid stress. With climate change driving shifts in regional susceptibility to extreme heat, certain areas that were previously not subjected to extreme heat are now experiencing heightened risks. By analyzing outage events at the county level, we highlight specific regions where the combination of heat and additional stressors, such as wind and precipitation, is increasingly compromising grid stability. This research enhances our understanding of how extreme weather impacts grid reliability, revealing critical vulnerabilities that could be tackled to improve the resilience of energy systems in a changing climate, emphasizing further the need for regional adaptive strategies tailored to emerging risks.

Results

Frequency and impact of weather-driven outages across CONUS

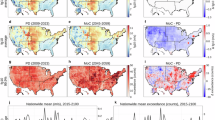

Figure 1 illustrates the number of unique outage events per county driven by heatwave events, including both standalone heatwaves and those compounded with other weather events, highlighting regions where outages were more frequent. The analysis identifies regions such as Southern California, Arizona, central Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, and parts of Colorado as significant hotspots, with disproportionately high occurrences of outages. Coastal regions, particularly vulnerable to tropical storms, also exhibit heightened susceptibility to frequent disruptions. Several areas, including the Southeast (Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas), the Northwest (Oregon and Idaho), the Mountain West, and the Mid-Atlantic, exhibit minimal recorded outages during heatwave events.

Table 1 summarizes the customer outage statistics per heatwave/weather event. The data revealed that while the median number of customers affected was low, certain extreme events significantly increased the maximum number of customers impacted. For example, the median number of customers affected by power outages during heatwaves compounded by other weather conditions such as tropical storms, heavy precipitation was relatively low, at just 16. However, during Hurricane Laura in Kent County, Louisiana, 62,374 customers were affected during a multi-day heatwave, illustrating the potential severity of compounding weather events. Figure 2 (panel a and b) depicts the distribution of the number of customers experiencing outages for different unique outage events where heatwave or compound effect of other weather events along with heatwave is observed. The majority of events have low outages, while a few extreme cases affect tens of thousands of customers. The reduced view (panel b) highlights that smaller outages are more frequent, whereas large-scale outages are rare but significant.

Outage duration and distribution

Table 2 reports on the variability of duration of power outages. A pattern emerges where most outages are relatively short, as highlighted by the left tail of the distribution (Fig. 2, panel (c) and (d)) with a median duration of 5 hours (Table 2). The full distribution (panel c) shows a heavy skew, with a few events lasting hundreds of hours, while the reduced view (panel d) focuses on the most common short-duration outages. This emphasizes that while prolonged outages occur, the majority of events are brief, reflecting quicker restoration times in most cases. Longer-duration outages are mostly caused by natural disasters such as the Carr Fire in California (2018), which led to outages lasting over 14 days, with a maximum recorded duration of approximately 358 hours. Additionally, cascading power disruptions from hurricanes, such as Hurricane Laura in Louisiana, contributed to prolonged outages that were reported to be a result of a single event, as these extended incidents could not be easily separated using the outage data; this further contributed to the long tail of outage durations.

Regional analysis of heat and compounding weather effects on power outages

Figure 3 reports on the quality of the SOM training for each region. The Adjusted Rand Index (ARI, Fig. 3 (A-H)) is used to assess the clustering performance of the model, with values closer to 1 indicating a high degree of agreement between the SOM-derived clusters and the reference classification23. A median ARI value above 0.8 in most regions suggests that the model produces highly consistent and reliable cluster assignments.

The highest ARI values are obtained for the Southeast region (0.98, Fig. 4h), PJM (0.97, Fig. 4c), and ISO-NE (0.92, Fig. 4b), indicating near-perfect alignment with the reference classification. Conversely, the lowest ARI value is reported for ERCOT (0.73, Fig. 4f), which, while lower than other regions, still reflects a strong clustering performance, suggesting that the model successfully captures the underlying patterns in the data. An ARI value of 0.73 indicates moderate to high agreement, though with some degree of misclassification compared to regions with ARI > 0.9. Overall, these results demonstrate the robustness of the model across different regions.

Each SOM configuration is shown for each study area by points indicating the ARI of the training dataset (x-axis) and the complete dataset (training plus validation) (y-axis) in relation to the original SOM throughout all 100 trials. All axes extend from zero to one; each graph features a one-to-one line.

Supplementary Table 2 presents the key weather variables influencing power outages across each EIA region which includes Total precipitation, Maximum wind speed, Maximum wind gust, Maximum heat index, Feel above 32.2 °C (90 °F) (h), and Feel above 39.4 °C (103 °F) (h) [According to the National Weather Service (NWS), the impact of heat index (also known as “feel value”) on human health is categorized into specific ranges, as shown in Supplementary Table 1. We used the NWS guidelines to identify 32.2 °C (90 °F) and 39.4 °C (103 °F) as key threshold values, defining them as Feel above 32.2 °C (90 °F) (h) and Feel above 39.4 °C (103 °F) (h) to represent the duration of exposure within these heat index ranges]. For the study region, the most significant factor appears to be the duration of the heatwave (with temperature exceeding 32.2 °C (90 °F)), which impacts nearly all regions. This is followed by the higher threshold (temperatures above 39.4 °C (103 °F)) and the heat index. Wind gusts seem to have the least impact when considering compound heatwave and weather events, affecting only three out of the eight regions. Among the regions, MISO exhibited the largest number of compound weather variables, followed by CALISO, while the Southeast region shows the fewest variables contributing to power outages.

Figure 4(A-H) shows the clusters contributing to the most frequent outages and Fig. 5(A-H) shows the clusters contributing to the most damaging outages across EIA regions. To facilitate understanding, Table 3 summarizes the statistics of the variables identified as main drivers in each cluster. Weather and heat effects on power outages are described in detail in the following sections for each EIA.

California ISO (CALISO)

The California Independent System Operator (CALISO) region exhibits a strong linkage between power outages and compounding meteorological extremes, particularly maximum heat index (“feel value”), heat index values exceeding 32.2 °C, maximum wind gust, total precipitation, and maximum wind speed. These factors underpin the formation of four distinct weather clusters (Fig. 4A, 5 A), which were categorized based on their meteorological characteristics (Table 3). Clusters 1 and 2 exhibit similar maximum heat index, wind speed, and gust values, yet differ significantly in total precipitation and the duration of extreme heat exceeding the 32.2 °C threshold. These differences suggest that while high heat and wind conditions contribute to outages in both clusters, precipitation levels and the duration of extreme heat play a critical role in shaping the severity and extent of these events. By contrast, Clusters 1 and 3 share comparable precipitation levels but diverge in their exposure to extreme heat and wind.

Cluster 3, characterized by the absence of high gusts and prolonged extreme heat, is associated with frequent outage events across many counties in the CALISO region (Fig. 4(A)). Rather, these frequent outage events are primarily driven by high wind speeds and elevated heat index values. However, the most severe and impactful outages are linked to Cluster 1, where extreme heat and strong winds occur together.

Spatial distribution of clusters associated with the most frequent customer outages across different EIA regions, based on compound weather events. Counties are grouped into five clusters (1 to 5) within each region, ranked by the median number of customers affected during events—Cluster 1 having the highest median impact and Cluster 5 the lowest. Colors denote the ranked clusters, while counties with no recorded events are shown in gray. Percentages in parentheses indicate the proportion of counties in each cluster (excluding non-event counties).

Spatial distribution of clusters associated with the most damaging customer outages across different EIA regions, based on compound heatwave-storm events. Clusters are ranked from 1 (highest) to 5 (lowest) by the maximum number of customers affected during events, with 1 representing the most severe outages. Colored clusters reflect these rankings, while gray indicates counties with no recorded events. Percentages in parentheses indicate the proportion of counties in each cluster (excluding non-event counties).

wind gusts, and sustained temperatures above 32.2 °C are markedly pronounced. Figure 5(A) highlights the significant contribution of Cluster 1 to the most disruptive outages in the region.

Northwest region

Northwest region power outages are primarily influenced by maximum heat index, total precipitation, and maximum wind speed. Figure 4(G) illustrates that heat-induced outages are predominantly concentrated in the mid and northern parts of the Northwest region. In most counties, power outages are typically caused by weather conditions classified under Cluster 4, which include a combination of high heat index, precipitation, and strong winds. Conversely, the most damaging outages are associated with Cluster 2, distinguished by elevated heat index values paired with moderate precipitation (Fig. 5(G)).

The characteristics of each cluster are detailed in Table 3. Clusters 1, 2, 3, and 4 exhibit similar mean customer outage values but distinct variations in the associated weather conditions. Cluster 1 is predominantly characterized by high rainfall coupled with moderate heat index values, whereas Cluster 2 experiences higher heat levels and reduced precipitation compared to Cluster 1. Cluster 3 stands out with a higher heat index than Cluster 2 but is marked by the absence of precipitation. Clusters 4 and 5 represent a mix of all-weather variables, albeit at lower levels across the board.

Southwest region

For the Southwest region, the analysis revealed limited variability in the weather factors contributing to power outages. Among the meteorological variables assessed, the maximum heat index emerged as the sole significant driver of outages, with other factors such as precipitation and wind speed showing minimal to no impact. Hence, the Self-Organizing Maps (SOM) model was not evaluated for this region.

Southwest power pool (SWPP ISO)

In the Southwest Power Pool (SWPP ISO) region, power outages are influenced by maximum heat index, total precipitation, and the duration of heat above 32.2 °C and 39.4 °C (Supplementary Table 2). Clusters 1, 2, and 3 exhibit similar mean outage values and maximum heat indices yet differ significantly in their weather characteristics (Table 3). Cluster 1, characterized by the highest maximum heat index and prolonged heat durations (above both 32.2 °C and 39.4 °C), experiences negligible rainfall. In contrast, Cluster 2 has slightly lower heat index values but higher precipitation, while still exhibiting a moderate duration of heat. Cluster 3 lacks both precipitation and prolonged heat exposure but shows a higher mean heat index (32.2 °C) than Cluster 2, with no recorded durations above 32.2–39.4 °C.

Figure 4(E) highlights a clear regional difference within the SWPP ISO area. In the northern portion, above 40°N latitude, outages during heat events are less severe. In this area, typical and impactful outages are linked to Cluster 2, where high heat coincides with some precipitation. In contrast, the southern part of the SWPP region is more vulnerable to severe outages, primarily driven by Cluster 1 (Fig. 5(E)). Here, prolonged extreme heat, coupled with minimal rainfall, substantially contributes to power disruptions. While Cluster 2 remains associated with more typical outages in this area, the most damaging events are caused by the intense and sustained heat conditions, characteristics of Cluster 1, leading to longer and more severe outages.

For SWPP ISO, the latitudinal variability of climate makes a difference on the compounded events. In the northern portion, outages happen at lower heat levels when compounded with precipitation. The southern areas, on the contrary, emerge as hotspots for outages when heatwaves are both more intense and longer, exacerbating the severity of disruptions.

Electric reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT)

In the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) region, power outages are influenced by maximum wind speed, total precipitation, and the duration of heat exceeding 32.2 °C and 39.4 °C. Evidently Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 share similarities with respect to mean customer outage values and maximum wind speed (Table 3). Cluster 1, however, exhibits slightly higher total rainfall and maximum heat index, along with significantly longer durations of extreme heat, with more hours above both the 32.2 °C and 39.4 °C thresholds than Cluster 2. Clusters 2 and 3 show comparable values for rainfall and maximum heat index but differ in other attributes (Table 3). Cluster 3 experiences lower wind speeds and a reduced duration of heat above 39.4 °C, while exhibiting a longer duration above 32.2 °C. Clusters 3, 4, and 5 exhibit relatively similar mean outage values; however, Cluster 4 is driven by higher rainfall and wind speeds, whereas outages in Cluster 3 are predominantly influenced by extended periods of extreme heat. Cluster 5, with slightly lower mean outage values, is characterized by a reduced maximum heat index but still experiences prolonged heat durations above both 32.2 °C and 39.4 °C thresholds (Table 3).

There is a clear regionalization effect within ERCOT, with distinct patterns observed between the western and eastern parts of the region (Fig. 5(H)). The western areas, largely dominated by Cluster 3, experience outages primarily driven by prolonged heat exposure. In contrast, the eastern areas, influenced by Clusters 1 and 5, face outages caused by a combination of extreme heat and precipitation.

The most severe outages across the ERCOT region are predominantly associated with Cluster 1, as shown in Fig. 5(F). These events, marked by high heat index values and extended heat durations, place substantial strain on the energy grid, resulting in more significant and widespread disruptions. Although typical outages vary regionally, across ERCOT the most impactful disruptions are consistently linked to the intense and sustained conditions of higher rainfall and maximum heat index, as well as significantly longer durations of extreme heat.

Midcontinent ISO (MISO)

In the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) region, power outages are influenced by heat index exceeding 32.2 °C and 39.4 °C, maximum heat index (“feel value”), maximum wind gust, total precipitation, and maximum wind speed. These variables contributed to the formation of five major clusters depending on their meteorological similarities and differences (Table 3).

Clusters 1 and 2 exhibit similar outage patterns, although Cluster 1 is associated with lower precipitation, lower maximum wind gusts, and a lower maximum heat index, but a significantly longer duration of heat above 39.4 °C. In contrast Cluster 2 has a lower mean customer outage, despite its higher precipitation and wind gusts. Clusters 3, 4, and 5 present closely related mean outage values. Clusters 1 and 4 share similar wind and gust characteristics, along with similar maximum heat index values (approximately 45.5 °C); the key difference lies in the duration, which is considerably shorter in Cluster 4. Cluster 3, on the other hand, is entirely driven by heat, with no contributions from precipitation or wind, despite having a lower maximum heat index value (35.1 °C) than Cluster 4 (45.8 °C). The mean heat index value in Cluster 3 (31.7 °C) is higher, contributing to a slightly elevated maximum customer outage than cluster 4 (28.7 °C). Cluster 5 demonstrates higher maximum and mean heat index values, along with longer durations above both 32.2 °C and 39.4 °C. The total number of outages is reduced, however, because of higher rainfall levels. Similarly, while Cluster 4 shares similar maximum heat index, wind speed, and durations above 32.2 °C with Cluster 5, it has higher gusts and longer durations above 39.4 °C, which ultimately leads to a slightly higher mean outage.

A clear regionalization effect is evident within MISO, similar to patterns observed in the Southwest Power Pool (Fig. 4 (D)). In the northern part of the MISO (40°N and above), the outage variability during heat events is less pronounced, with typical outages primarily linked to Cluster 4 and Cluster 5. The outages with the most impact, however, are associated with Cluster 1(Fig. 5(D)).

In the southern part of the region (below 40°N), typical outage events also originate from Cluster 5, while the most significant outages (based on customers impacted) are driven by Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 (Fig. 5(D)). These findings highlight the variation in outage dynamics across latitudes while underscoring the critical role of extreme heat and its interaction with other meteorological factors in driving significant outages across both northern and southern MISO regions.

Southeast region

Across the Southeast, prolonged periods of elevated heat index—particularly above critical thresholds exceeding 32.2 °C and 39.4 °C constitute the primary meteorological driver of power outages, especially in the western counties. The identified variables contributed to the formation of three major weather clusters, based on their meteorological similarities and differences (Table 3). The clusters exhibit a clear trend: as the duration of extreme heat increases, so does the mean customer outages. The increase in the duration of the heat index above 32.2 °C in Cluster 2, for instance—double that of Cluster 3—correlates with a significant increase in mean customer outages, reflecting an amplitude on the order of 10³ scale. This correlation highlights the critical role of prolonged heat exposure in amplifying customers being affected.

Geographically, only the western counties of the Southeast region are significantly affected by heat-induced outages (Fig. 5(H) 6(H)). Typical outage events (Figs. 5(H)) are primarily associated with Cluster 3, while the most significant outages (based on customers impacted) (Figs. 6(H)) are linked to Cluster 2, which experiences longer durations of heat index values above 39.4 °C than the other clusters.

PJM ISO (PJM ISO)

In the PJM ISO region, power outages are predominantly governed by sustained high heat index values exceeding 32.2 °C and 39.4 °C, as well as the maximum heat index (“feel value”), underscoring the vulnerability of infrastructure to prolonged thermal extremes. The findings indicate that higher maximum heat index values and prolonged durations above 32.2 °C are significant contributors to the elevated outage occurrences observed in Cluster 1 compared to Cluster 2. This suggests extreme heat plays a crucial role in driving power outages in this region (Table 3).

Geographically, Figs. 5(C) 6(C)) illustrate that only certain northeastern and western counties exhibit heightened vulnerability to heat-induced outages. The most typical and damaging outages are associated with Cluster 1, primarily due to the elevated maximum heat index values and prolonged heat durations experienced in this cluster. The PJM ISO region would require, therefore, targeted strategies to address the vulnerabilities associated with extreme heat as an independent driver.

New York ISO (NYISO) and new England ISO (ISO-NE)

Given their operational and meteorological similarities, New York ISO (NYISO) and New England ISO (ISO-NE) regions are jointly assessed, with findings indicating that high heat index values exceeding 32.2 °C and 39.4 °C, maximum heat index (“feel value”), and maximum wind speed are central to outage occurrences. The findings indicate that higher maximum heat index values, elevated wind speeds, and extended durations of heat above 32.2 °C are significant contributors to the increased outage occurrences observed in Cluster 1 compared to Cluster 2 (Table 3). Geographically, Fig. 4(B) and Fig. 5(B) attribute the most typical and damaging outages primarily to Cluster 1, largely due to the elevated temperatures. This region exhibits behavior that is strikingly similar to the PJM ISO region, highlighting the common challenges faced by both regions in managing the impacts of severe weather on power infrastructure.

Discussion

Figure 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of heatwave-induced power outages, revealing notable regional disparities. Specifically, in some regions extreme heat is not sufficient to disrupt the power system; rather, it is the compounding effect of multiple weather events that leads to severe power disruptions across different counties. Several areas, including the Southeast, the Northwest, the Mountain West, and the Mid-Atlantic, exhibit minimal recorded outages during heatwave events. In the Northwest, reliance on hydropower24 and low population density contribute to fewer reported heatwave-caused outages15. Mountain West’s dry climate and cooler nocturnal temperatures further mitigate grid stress from heatwaves25. The Mid-Atlantic benefits from a milder climate, which produces fewer extreme daytime temperatures and allows some nighttime cooling and a resilient PJM-operated grid with significant modernization investments26. In the Southeast, Florida exemplifies proactive energy system hardening, with storm protection measures, mandatory Ten-Year Site Plans, and rapid restoration efforts enhancing reliability.

This study revealed significant insights into the spatiotemporal patterns of power disruptions driven by compounding heatwave/weather events across the ISO service territories of the contiguous United States. Key hotspots, including those in Southern California, Arizona, central Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, and parts of Colorado, experienced a disproportionately high frequency of outages during periods of extreme heat. Although the median number of customers affected per incident was relatively low, the maximum number of customers experiencing outages during extreme events, such as Hurricane Laura and the Carr Fire, highlights the critical need to address the “long tail” of outage occurrences. For instance, while the median outage duration was approximately five hours, extreme heatwave compounding events like the Carr Fire in 2018 resulted in outages that persisted for up to 358 hours. This underscores the disproportionate impact of rare, severe events on overall outage metrics.

Regional analyses revealed that heatwaves, compounded by other severe weather phenomena such as winds, wind gusts, and heavy rainfall significantly amplify the extent and duration of outages. This is aligned with prior research suggesting that grid stress from extreme heat, combined with physical damage from storms, can result in cascading failures and prolonged recovery times. For instance, Kenward and Raja27 found that excessive heat presents at least double the risk of power disruptions compared to tornadoes alone. Our examination of outage events alongside the key weather variables made clear that certain regions such as CALISO and ERCOT share similar extreme heat conditions but diverge in the additional meteorological factors that contribute to outage severity.

In CALISO, the interplay of high heat index values and strong wind gusts emerge as a primary driver of severe power outages, particularly in coastal regions susceptible to prolonged heat and wind extremes. This dynamic is exacerbated by low precipitation, reducing both infrastructure cooling capacity and environmental resilience. Weather conditions, characterized by sustained temperatures exceeding 32.2 °C and wind gusts over 18 m/s, consistently lead to high outage severity, highlighting the compounded effects of heat and wind. In contrast, Cluster 3, dominated by elevated heat without significant wind stress, results in lower outage impacts, suggesting that heat alone is insufficient to drive the most severe events. The North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) has warned that excessive heat may “present operational risks,” particularly later in the summer, when hydroelectric generation diminishes, and solar PV output is near zero during peak hours28.

Conversely, in ERCOT, wind speed and precipitation deficits play a more dominant role. Prolonged heat exposure, coupled with minimal rainfall, weakens grid resilience, making the system highly vulnerable during extended heatwaves, especially when heat index values exceed 32.2 °C and rainfall is negligible. Unlike CALISO, where wind gusts are critical, ERCOT’s outages are more closely tied to precipitation deficits.

Further distinctions arise in regions like the Midcontinent ISO (MISO) and the Southwest Power Pool (SWPP). In MISO, northern areas exhibit greater sensitivity to high wind speeds combined with moderate heat, whereas southern regions are more affected by prolonged heatwaves with lower wind speeds. These intra-regional variations necessitate tailored grid resilience strategies. NERC projections highlight capacity deficits in MISO’s Northern and Central regions, increasing risks of energy crises during peak heat conditions. In the Northwest, precipitation plays a more critical role than heat alone in influencing outage severity. The highest outages in this region depend on moderate heat index values but high rainfall, contrasting with the Southwest, where heat is the overwhelming factor. This inter-regional difference highlights the meteorological diversity in the drivers of outages across the U.S., with water-related phenomena like rainfall intensity in the Northwest acting as a major contributor to power disruptions. This differs from the Southwest, where prolonged drought and extreme heat without wind or precipitation create conditions for extended outages29. Furthermore, the interplay of moderate temperatures and significant rainfall intensity in the Northwest underscores the unique challenges faced by this region, where infrastructure must contend with prolonged wet conditions and their impacts on system stability.

The Southwest Power Pool also experiences outages primarily driven by extreme heat and low rainfall, but unlike CALISO and ERCOT, these outages are less influenced by wind gusts. In contrast, PJM, New York ISO (NYISO), and New England ISO (ISO-NE) face outages driven by a mix of moderate heat and severe weather events, such as winter storms. ISO-NE is distinct from its cold-weather outages caused by high winds and heavy snowfall.

Overall, across all the regions, our analysis highlighted the importance of extreme heat in driving outages but underscored the variability introduced by the compounding effect of wind and precipitation. Regions where multiple meteorological stressors coincide, such as CALISO, ERCOT, and the Southeast exhibited the most severe outages. These findings emphasize the need for region-specific grid resilience strategies, as the compound effects of weather conditions demand localized adaptations.

While weather-related events are primary drivers, the state of energy infrastructures, operational decisions, and regional energy demand also play critical roles. Future research should integrate these factors to provide a comprehensive assessment of outage dynamics and inform strategies for enhanced resilience. The outage data from EAGLE-I, derived via web-scraping utility sites, inherently contains inconsistencies and gaps both in terms of customer coverage and customers without power during an outage event. Variations in data availability across utilities, regions, and time periods introduce challenges in completeness and granularity, despite extensive preprocessing. As noted in the Methods, inconsistencies in early EAGLE-I reporting driven by phased utility participation necessitate caution in interpreting localized results, especially in regions with delayed data integration. Our event identification framework was designed to account for this variability and to emphasize robust, consistently reported outage patterns. Although continued improvements in reporting will be critical for improving the accuracy of future analyses, our analyses capture the underlying weather variables contributing to outage risks across different ISOs that should be accounted for by utilities to not only improve reliability of the energy infrastructures, but also to meet load growth within specific territories during extreme events and otherwise.

Methods

Study sites

The analysis was conducted across multiple EIA balancing authorities to capture regional variations in outage dynamics. These regions included California ISO (CALISO), Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), Midcontinent ISO (MISO), PJM Interconnection (PJM), New York ISO (NYISO), ISO New England (ISO-NE), Northwest, Southwest, and Southwest Power Pool (SWPP). Due to their similar behavior, ISO New England and New York ISO were consolidated into a single region for analysis. Regions without an Independent System Operator (ISO), such as the Northwest and Southwest, were analyzed separately to account for their distinct infrastructure and operational characteristics.

Data collection and preprocessing

Community outage data

The outage dataset was sourced from the U.S. Department of Energy’s EAGLE-I platform, which records utility reported number of customers experiencing outages at 15-minute intervals from November 2014 to December 2022. This dataset provides county-level estimates of outages using Federal Information Processing Standard Publication (FIPS) codes for accurate geographic mapping. Special attention was given to addressing inconsistencies, such as multi-county utility coverage and gaps due to missing values. Data were aggregated into hourly intervals by computing the maximum outage count per utility within a county. Missing intervals were filled with zero values, ensuring temporal consistency.

The weather events data

Weather data were obtained from the National Weather Service (NWS) Valid Time Extent Code (VTEC)30and archived and processed by the Iowa Environmental Mesonet (IEM), Iowa State University (https://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/request/gis/watchwarn.phtml). The dataset included detailed records of weather warnings, watches, and advisories, filtered to focus on extreme heat-related events (e.g., excessive heat warnings and heat advisories, identified by codes HT and EH). To complement this, meteorological variables were sourced from the Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS)31which provided hourly measurements of temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, wind gusts, and precipitation. These variables were aligned with the timing of outage events to explore the influence of weather conditions during both the onset and peak of outages. Heat index values, which quantify thermal stress, were calculated using Rothfusz’s regression equations documented in the NWS Technical Attachments (1990) (Visit http://www.wpc.ncep.noaa.gov/html/heatindex_equation.shtml to see the original instruction).

Outage event identification

Over the study period, utility participation in the EAGLE-I platform increased substantially, with customer coverage improving from around 75% in 2015 to over 90% by 2022. This evolving coverage introduces temporal variability in data density, particularly in earlier years when fewer utilities reported outages. As a result, regions with delayed adoption may exhibit lower event counts or incomplete records. To address this, we focused our analysis on spatial and temporal segments with consistent reporting and referenced the data quality index developed by Brelsford et al. (2023)17 to support data integrity screening and trend robustness. Outage events were defined at the county level as periods when the number of customers without power exceeded the 75th percentile of that county’s historical outage distribution. To determine the most appropriate threshold, we conducted a sensitivity analysis comparing the performance of multiple percentile-based cutoffs including the median (50th), 75th, 80th, and 90th percentiles against known major outage events reported in other literatures and media sources. Higher thresholds, such as the 90th percentile, failed to capture smaller yet consequential outage events, particularly those relevant for identifying regional vulnerability patterns. Conversely, lower thresholds (e.g., 50th percentile) tended to over-flag minor or routine disruptions that lacked operational or societal relevance. The 75th percentile offered an optimal balance: it successfully captured both moderate and high-impact events while filtering out background noise from minor disruptions. This threshold demonstrated the strongest agreement with verified outage timelines and was thus selected for defining outage events in a robust and reproducible manner.

Event initiation occurred when this threshold was first breached, while termination criteria included: (i) a gap exceeding one hour between outage observations, (ii) a drop below the 75th percentile, or (iii) a reduction of 50% or more in customer impacts within a single timestep. This rigorous approach minimized noise and ensured that only significant outage events were considered. An example of outage event selection is demonstrated in supplementary Fig. 1.

Variable selection using Stepwise regression

To refine the input variables for the SOM clustering and identify the most significant meteorological predictors of outages, a stepwise regression approach was employed. Weather variables from the ASOS dataset including temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, wind gusts, precipitation, and Heat index values were also included to capture the intensity and duration of extreme heat conditions, with thresholds set at 32.2 °C and 39.4 °C to distinguish periods of “extreme caution” and “danger,” respectively.

The regression process combined forward selection and backward elimination, guided by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), to balance model complexity and explanatory power. Separate regressions were performed for each EIA region to account for regional differences in weather-outage relationships.

Self-organizing maps (SOM) for clustering

The Self-Organizing Maps (SOM) algorithm32 was employed to identify patterns between weather variables and outage events. SOM is an unsupervised machine learning technique that projects high-dimensional data onto a two-dimensional grid while preserving topological relationships. To ensure optimal clustering performance, the SOM configuration was determined using Kohonen’s heuristic33 and initialized using Fusco and Perez34’s automated procedure. Stability of the clustering results was assessed using the Fowlkes-Mallows similarity index35and watershed segmentation36was applied to partition the grid into distinct clusters.

Key weather variables identified through stepwise regression were used as inputs for the SOM. These variables were analyzed during the onset and peak of each outage event to identify critical periods of meteorological influence. Figure 6 demonstrates an example of how different nodes of weather parameters are combined into four different cluster patterns for California ISO.

To ensure robustness, the clustering model was validated through cross-validation using 100 randomized trials. The Adjusted Rand Index (ARI)¹⁵ was calculated to assess the consistency of clustering outcomes across training and validation datasets. Sensitivity analyses included variations in SOM parameters and input variables to evaluate the stability of the results across different EIA regions.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study including Eagle-I data, NWS VTEC data, and ASOS weather station data are publicly available and are detailed in the Methods section. The code, required shapefiles, weather data, and outage data in CSV format are also publicly accessible at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15466662. Additional data or analytical code supporting the findings, but not included in the published article, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gonçalves, A. C. R., Costoya, X., Nieto, R. & Liberato, M. L. R. Extreme weather events on energy systems: a comprehensive review on impacts, mitigation, and adaptation measures. Sustainable Energy Res. 11, 4 (2024).

Schaeffer, R. et al. Energy sector vulnerability to climate change: A review. Energy 38, 1–12 (2012).

Udeh, K. et al. Autoregressive modeling of utility customer outages with deep neural networks. In 2022 IEEE 12th Annual Computing and Communication and Conference (CCWC) 0406–0414 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/CCWC54503.2022.9720799

Yang, F., Koukoula, M., Emmanouil, S., Cerrai, D. & Anagnostou, E. N. Assessing the power grid vulnerability to extreme weather events based on long-term atmospheric reanalysis. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 37, 4291–4306 (2023).

Gernaat, D. E. H. J. et al. Climate change impacts on renewable energy supply. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 119–125 (2021).

Xu, L. et al. Resilience of renewable power systems under climate risks. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 1, 53–66 (2024).

Hasenbein, J. J., Kutanoglu, E. & Toplu-Tutay, G. Impact of Power Outages Depends on Who Loses It: Equity-Informed Grid Resilience Planning. (2023).

Dzwonkowski, B. et al. Compounding impact of severe weather events fuels marine heatwave in the coastal ocean. Nat. Commun. 11, 4623 (2020).

Parmesan, C., Root, T. L. & Willig, M. R. Impacts of Extreme Weather and Climate on Terrestrial Biota. (2000).

Feng, K., Ouyang, M. & Lin, N. Tropical cyclone-blackout-heatwave compound hazard resilience in a changing climate. Nat. Commun. 13, 4421 (2022).

Mazza, A. et al. Evaluation of the Impact of Heat-Wave on Distribution System Resilience. Preprint http://arxiv.org/abs/2104.09308 (2021).

Mukherjee, S., Nateghi, R. & Hastak, M. A multi-hazard approach to assess severe weather-induced major power outage risks in the U.S. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 175, 283–305 (2018).

Ke, X., Wu, D., Rice, J., Kintner-Meyer, M. & Lu, N. Quantifying impacts of heat waves on power grid operation. Appl. Energy. 183, 504–512 (2016).

Panteli, M. & Mancarella, P. Influence of extreme weather and climate change on the resilience of power systems: impacts and possible mitigation strategies. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 127, 259–270 (2015).

Do, V. et al. Spatiotemporal distribution of power outages with climate events and social vulnerability in the USA. Nat. Commun. 14, 2470 (2023).

Stevens, K. A. & Belligoni, S. Policymaking in the dark: the impact of power outage information asymmetry on local government resilience efforts in Florida. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 105, 104381 (2024).

Brelsford, C. et al. A dataset of recorded electricity outages by united States County 2014–2022. Sci. Data. 11, 271 (2024).

Watson, P. L., Pasqualini, D., Anagnostou, E. A. & Data-Driven Decision support tool for anticipating tropical storm impacts to the united States power grid. IEEE Access. 12, 112905–112923 (2024).

Tran Thi Tuyet, M., Van Vo, H. & Le Danh, T. Application of self-organizing maps and K–Means methods to classify summer heat wave weather patterns in Viet Nam. VNJHM 11, 15–25 (2022).

Chang, F. J., Chang, L. C., Kao, H. S. & Wu, G. R. Assessing the effort of meteorological variables for evaporation Estimation by self-organizing map neural network. J. Hydrol. 384, 118–129 (2010).

Fassnacht, S. R. & Derry, J. E. Defining similar regions of snow in the Colorado River Basin using self-organizing maps. Water Resour. Res. 46, W04507 (2010).

Hsu, K. C. & Li, S. T. Clustering spatial–temporal precipitation data using wavelet transform and self-organizing map neural network. Adv. Water Resour. 33, 190–200 (2010).

Hubert, L. & Arabie, P. Comparing partitions. J. Classif. 2, 193–218 (1985).

Pacific Northwest Hydropower for the 21st Century Power Grid | Northwest Power and Conservation Council. https://www.nwcouncil.org/energy/energy-topics/hydropower/. Accessed 4 Nov 2024 (2019).

Narayanan, A., Rezaali, M., Bunting, E. L. & Keellings, D. It’s getting hot in here: Spatial impact of humidity on heat wave severity in the U.S. Sci. Total Environ. 963, 178397 (2025).

National Transmission Needs Study. Accessed 4 November 2024; (2023). https://www.energy.gov/gdo/national-transmission-needs-study

Kenward, A. & Raja, U. Blackout: Extreme Weather, Climate Change and Power Outages. (2014).

NERC (North American Electric Reliability Corporation). Long-Term Reliability Assessment. https://www.nerc.com/pa/RAPA/ra/Pages/default.aspx (2023).

Harto, C. B. et al. Analysis of drought impacts on electricity production in the Western and Texas interconnections of the United States. ANL/EVS/R-11/14, 1035461. http://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1035461/ (2012). https://doi.org/10.2172/1035461

US Department of Commerce, N. VTEC. https://www.weather.gov/vtec/. Accessed 4 Nov 2024 (2024).

Powell, M. D. Wind Measurement and Archival under the Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS): User Concerns and Opportunity for Improvement. (1993).

Kohonen, T. The self-organizing map. Proc. IEEE. 78, 1464–1480 (1990).

Fytilis, N. & Rizzo, D. M. Coupling self-organizing maps with a Naïve bayesian classifier: stream classification studies using multiple assessment data. Water Resour. Res. 49, 7747–7762 (2013).

Fusco, G. & Perez, J. Bayesian network clustering and Self-Organizing maps under the test of Indian districts. A comparison. Cybergeo https://doi.org/10.4000/Cybergeo.31909 (2019).

Fowlkes, E. B. & Mallows, C. L. A method for comparing two hierarchical clusterings. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 78, 553–569 (1983).

Vincent, L. & Soille, P. Watersheds in digital spaces: an efficient algorithm based on immersion simulations. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 13, 583–598 (1991).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S.: conceptualization, methodology, data collection, analysis and development, writing—original draft, visualization, script writing; G.S.: methodology, analysis and development, visualization, writing—review and editing; B.K.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing; E.A.: conceptualization, methodology, analysis and development, writing—review and editing, supervision, funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saki, S., Sofia, G., Kar, B. et al. A multi-year analysis of the impact of heatwaves and compound weather events on power outages. Sci Rep 15, 30846 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15065-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15065-x