Abstract

The rapid advancement of key technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and edge-cloud computing has significantly accelerated the transformation toward smart industries across various domains, including finance, manufacturing, and healthcare. Edge and cloud computing offer low-cost, scalable, and on-demand computational resources, enabling service providers to deliver intelligent data analytics and real-time insights to end-users. However, despite their potential, the practical adoption of these technologies faces critical challenges, particularly concerning data privacy and security. AI models, especially in distributed environments, may inadvertently retain and leak sensitive training data, exposing users to privacy risks in the event of malicious attacks. To address these challenges, this study proposes a privacy-preserving, service-oriented microservice architecture tailored for intelligent Industrial IoT (IIoT) applications. The architecture integrates Differential Privacy (DP) mechanisms into the machine learning pipeline to safeguard sensitive information. It supports both centralised and distributed deployments, promoting flexible, scalable, and secure analytics. We developed and evaluated differentially private models, including Radial Basis Function Networks (RBFNs), across a range of privacy budgets (\(\varepsilon\)), using both real-world and synthetic IoT datasets. Experimental evaluations using RBFNs demonstrate that the framework maintains high predictive accuracy (up to 96.72%) with acceptable privacy guarantees for budgets \(\varepsilon \ge 0.5\). Furthermore, the microservice-based deployment achieves an average latency reduction of 28.4% compared to monolithic baselines. These results confirm the effectiveness and practicality of the proposed architecture in delivering privacy-preserving, efficient, and scalable intelligence for IIoT environments. Additionally, the microservice-based design enhanced computational efficiency and reduced latency through dynamic service orchestration. This research demonstrates the feasibility of deploying robust, privacy-conscious AI services in IIoT environments, paving the way for secure, intelligent, and scalable industrial systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intelligent healthcare systems have been made possible by the rapid growth of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). These systems offer innovative functions in a variety of fields, including Ambient Assisted Living (AAL), the management of geriatric patients, and remote patient monitoring within hospitals. With the help of networked Internet of Things devices, it is possible to collect physiological data from patients in real time to develop intelligent healthcare applications that are powered by machine learning (ML)1. These applications seek to obtain significant information on patient health issues, facilitating prompt diagnosis, proactive intervention, and personalized care. However, the implementation of machine learning tasks requires considerable processing resources, frequently exceeding the limitations of resource-constrained Industrial Internet of Things devices. Consequently, cloud computing has historically functioned as the foundation for performing substantial machine learning workloads by abstracting intelligent services for healthcare providers and customers2. Cloud platforms offer essential scalability and processing capabilities; nevertheless, they present significant issues, especially concerning latency, bandwidth usage, and data protection3. Sending IIoT-generated health data to central cloud infrastructures increases connection overhead and latency, hindering real-time analytics for remote patient care4. Second, the centralized structure of cloud service providers (CSPs) increases the risk of illegal access to sensitive health data, causing privacy concerns to worsen5. Most cloud-based intelligent healthcare systems use monolithic designs that combine services. Scaling and administering this architecture is challenging, and even a single component failure can trigger systemic failures6.

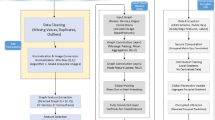

Conventional methodology for the training and deployment of machine learning models within a cloud infrastructure (the diagram was created using the Draw.io tool, available at https://www.drawio.com/).

A new paradigm is needed to overcome limitations, ensuring scalable, sustainable service deployment, patient privacy, bandwidth reduction, and real-time analytics with reduced latency7. Edge computing provides a viable solution for computation and execution of services near the data source, creating a continuum between the edge and the cloud8. Distributing machine learning workloads to edge servers improves service availability and reaction times for intelligent healthcare apps. Implementing intelligent ML-driven apps on edge infrastructures might increase complexity in service delivery and orchestration9. Microservice architectures have emerged as a management-friendly alternative to monolithic systems. Figure 1 describes the conventional methodology for the training and deployment of machine learning models within a cloud infrastructure. Microservices divide big programs into smaller, deployable services to promote scalability, fault isolation, and flexibility10. Due of these benefits, several leading firms have converted from monolithic to microservice designs. Includes Netflix, Facebook, Amazon, and Uber. Distributing machine learning services among edge nodes might enhance responsiveness and performance in smart healthcare11. However, precise analytics while securing patient data remain a major challenge. Existing privacy-preserving approaches like k-anonymity, Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMC), and Homomorphic Encryption (HE) have computational complexity, scalability, and attack vector vulnerabilities. SMC and HE are inappropriate for real-time IIoT applications because to high computational and communication costs, whereas k-anonymity is quickly undermined by homogeneity and background knowledge attacks12.

Differential Privacy (DP) is appealing. Since its 2006 start, the Microsoft Research-developed Differential Privacy (DP) standard for privacy-preserving data analytics has been widely used in academia and business13. DP hardware is in Google and Apple products. Differential privacy assures that record inclusion or deletion has little effect on the final outcome by adding controlled statistical noise to the data or model parameters. This allows deep data analysis while protecting privacy. Several DP-based methods, such as input, model, and output perturbations, have been developed14. Perturbations include adding noise to datasets, modifying objective functions or gradients, and adjusting ultimate results15. Research on balancing data usefulness and privacy protection remains difficult, especially in mission-critical, real-time situations like smart healthcare. The study presents a novel framework combining microservice-based architectures with differential privacy techniques for privacy-preserving machine learning in IIoT-driven healthcare systems16. The proposed solution is designed to provide real-time, distributed analytics at the network edge while safeguarding patient data with rigorous privacy measures17.

Motivation

The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) enables real-time data acquisition and intelligent decision making across domains such as healthcare, urban infrastructure, energy, and agriculture. In smart healthcare specifically, IIoT devices and machine learning (ML) models support disease detection and patient monitoring tasks that are highly sensitive and critical to human well-being. However, the deployment of ML in IIoT environments faces several fundamental challenges. First, edge devices although suitable for low-latency processing-often lack the computational power required for training complex ML models. While hybrid edge–cloud computing architectures offer a practical compromise, ensuring efficient and secure coordination between these layers remains non-trivial. Second, existing monolithic architectures hinder scalability and agility in ML workflows. Microservice-based approaches have been proposed to address this, but current implementations rarely integrate them with privacy-preserving mechanisms in a cohesive framework. Third, protecting sensitive healthcare data during transmission and computation is paramount, yet most existing solutions either rely on computationally expensive cryptographic protocols or lack formal privacy guarantees.

Differential Privacy (DP), particularly in its localised form, offers promising potential to perturb data before it leaves edge devices. Still, integrating local DP with decentralised microservices in an edge–cloud continuum remains underexplored. Moreover, many prior works fail to formalize threat models or demonstrate how their designs withstand real-world adversarial conditions. This research addresses these gaps by proposing a microservice-driven, privacy-preserving edge–cloud architecture for IIoT-based healthcare applications. The framework integrates local differential privacy at the edge, microservice-based orchestration for modular ML workflows, and hybrid computation to achieve scalability, low latency, and data confidentiality. By explicitly tackling limitations in computational distribution, workflow flexibility, and privacy enforcement, this work aims to establish a practical and secure paradigm for smart healthcare and, by extension, other IIoT domains.

Research contributions

A new privacy-preserving machine learning architecture for intelligent healthcare applications in IIoT frameworks is presented in this research. Using microservices in an edge-cloud architecture, the framework detects diseases in real time while protecting patient data. A modular machine learning architecture that distributes lightweight microservices across cloud and edge layers for efficient and privacy-aware data processing is a major addition.

-

To protect data during transmission, the Global Differential Privacy (GDP) Mechanism uses regulated noise in local outputs on private edge servers, eliminating the requirement for trusted third parties.

-

Integration of Radial Basis Function Networks (RBFNs) with Data Protection Policies (DP): GDPR-compliant adjustments for healthcare data classification to safeguard privacy.

-

An item that uses variation. Preprocessing reduces data sensitivity by reducing feature variation before differential privacy. This enhances model correctness.

Overall, these discoveries set the groundwork for a secure, accurate, and scalable IIoT-based machine learning framework for smart healthcare that might be used in other privacy-conscious real-time businesses.

Research background

To propose a privacy-preserving machine learning framework for IIoT-driven intelligent healthcare applications, this section summarises recent differential privacy and microservice-based architecture research.

Differential privacy in machine learning

A key privacy-preserving technique in ML applications is DP. Conventional centralised methods, exemplified by the DP-Naïve Bayes model presented in18, modify model parameters such as the mean and variance to uphold privacy assurances. Although efficient, centralised data collecting presents bandwidth constraints and renders datasets vulnerable to internal security risks in cloud-based systems. Furthermore, the noise generated by differential privacy frequently diminishes model accuracy and availability, requiring sophisticated trade-off procedures. In19, the authors introduced an enhanced version of classical DP by amalgamating it with ensemble models. Noise was systematically introduced according to feature significance determined by decision trees, while model training employed a mini-batch gradient descent method. This method improved privacy tracking via a moment accountant and attained satisfactory accuracy; nevertheless, it was constrained by limited dataset sizes and the necessity for moderate epsilon values

to ensure acceptable performance. Numerous distributed DP-based methodologies have been introduced to address the shortcomings of centralised infrastructures.

Table 1 summarizes recent approaches combining differential privacy with various architectures, highlighting their methods, application domains, and key limitations. In20, a DP logistic regression model was constructed using hybrid datasets, incorporating public data to improve availability while protecting the private dataset by gradient perturbation. Nonetheless, its efficacy is constrained in situations when public data distributions diverge from private ones. In24, the authors trained local classifiers with private data and subsequently moved their outputs to a public dataset for final model training under differential privacy; nonetheless, the model’s quality was significantly dependent on stable data distributions. Advanced methodologies integrating DP with Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMC) were examined in21, wherein entities executed local computations and disseminated encrypted, differentially private outputs inside a ring topology. Although this method ensures strong privacy in collaborative learning, its suitability for more complex tasks, such as non-linear classification and neural networks, is dubious because it is mainly applicable to linear regression models25. These studies demonstrate an increasing trend towards privacy-preserving approaches, including differential privacy, in decentralised machine learning training. New frameworks for IIoT contexts with limited resources are needed due to their scalability, model diversity, and edge architecture compatibility issues.

Microservices for scalable and secure smart applications

This method ensures anonymity in collaborative learning, but its applicability to complex tasks like non-linear classification and neural networks is limited to linear regression models26. All articles show a growing trend towards implementing privacy-preserving techniques, including differential privacy, in decentralised machine learning training operations27. New frameworks are needed for Internet of Things contexts with restricted resources due to limitations in scalability, model diversity, and compliance with edge architectures28. The methodology was implemented in smart city contexts, including tourism recommendations and predictive policing. Additional research, including29, illustrated the efficacy of microservices in environmental monitoring systems. The suggested air quality prediction system evaluated streaming data in real-time to alert users to potential health risks associated with pollutant levels. This further substantiates the function of microservices in managing changing data sources and time-critical tasks.

The incorporation of privacy within microservices has also been examined. The study in22 introduced a microservice-oriented paradigm for clinical data sharing that substitutes conventional de-identification methods with anonymised service interactions. This facilitates the secure management of sensitive healthcare information without revealing unprocessed characteristics. Likewise, Luo et al.30 incorporated privacy-preserving limitations into microservice-enabled systems by integrating traceable consent and data protection regulations within the architectural design. These initiatives seek to ensure adherence to data protection standards while facilitating modular service orchestration. The present literature demonstrates substantial advancements in the use of Differential Privacy and microservices to diverse smart applications31. Nonetheless, there is scant research that concurrently investigates the interplay between differential privacy and microservices within a distributed edge-cloud continuum, particularly in healthcare Industrial Internet of Things systems utilising neural network models such as Radial Basis Function Networks (RBFNs). This necessitates a cohesive framework that guarantees privacy, scalability, and low-latency intelligence for sensitive and resource-limited healthcare settings32.

Microservice-based machine learning frameworks

Microservice architectures have proven useful for decomposing complex machine learning (ML) pipelines. Works such as Goe et al.33 and Taherdoost et al.34 demonstrate benefits in scalability and maintainability. However, these efforts primarily address general ML lifecycle management and often overlook critical privacy requirements in IIoT contexts.

In contrast, our design unifies microservices with privacy-preserving techniques and edge–cloud orchestration. This hybrid approach enables secure, modular, and responsive healthcare analytics pipelines tailored to IIoT constraints. Table 2 summarizes and contrasts the key features of representative works in each theme against our proposed framework.

Preliminary considerations

This section presents the fundamental principles utilised in the creation of the proposed privacy-preserving machine learning system, with a focus on the integration of Differential Privacy (DP) mechanisms and Radial Basis Function Networks (RBFNs). The section has been restructured to clearly articulate the theoretical foundations, architectural motivations, and relevant prior research that shaped the design of our framework for secure, scalable IIoT applications.

-

Differential privacy guarantees: Differential Privacy (DP) offers a mathematically sound approach to protecting individual data points within a dataset by introducing carefully calibrated random noise. This mechanism ensures that the removal or inclusion of a single data instance does not significantly affect the output of a computation. The core parameter \(\varepsilon\) (epsilon) quantifies the privacy guarantee, with smaller values indicating stronger privacy. In our framework, we implement DP through output perturbation within the machine learning pipeline. This allows us to prevent the reconstruction or inference of sensitive user data, even in the presence of adversaries with background knowledge. The integration of DP is particularly relevant in IIoT environments, where data sources such as medical sensors, industrial controllers, and smart devices generate highly sensitive and often identifiable information. By adopting DP, we align with emerging data protection regulations while preserving a balance between privacy and model performance.

-

Microservice isolation: To support modularity, maintainability, and security, the proposed system is built upon a microservice-based architecture. Each functional module-such as data ingestion, preprocessing, privacy enforcement, and model inference is implemented as a lightweight, self-contained service. These services communicate over secure and efficient protocols (e.g., gRPC) and are orchestrated dynamically using containerised environments such as Docker. This microservice isolation ensures that failures or vulnerabilities in one component do not compromise the entire system. Furthermore, it enables the independent scaling and updating of services, which is essential in IIoT environments characterised by resource constraints and dynamic workloads. The ability to isolate and orchestrate services across both edge and cloud nodes provides significant advantages in terms of latency reduction, fault tolerance, and deployment flexibility.

-

Distributed machine learning inference: Traditional centralized learning architectures are often unsuitable for IIoT applications due to constraints on bandwidth, latency, and data locality. To address these challenges, our system is designed to support both centralized and distributed inference modes. At the edge, localized inference is performed to ensure low-latency decision-making and real-time responsiveness. For more complex analytical tasks, intermediate results or feature embeddings can be securely aggregated in the cloud. The system is also capable of injecting differential privacy noise in a distributed manner, with each edge node applying a perturbation to its partition of the dataset. This distributed DP strategy maintains end-to-end privacy guarantees without the need for raw data sharing, thereby enabling scalable and secure federated analytics.

-

Integration of prior work and design rationale The architectural decisions in our system are grounded in insights derived from existing literature. Previous centralized DP models have demonstrated susceptibility to internal threats and often fail to scale effectively in edge-centric deployments. Other works on microservices have achieved success in modularising cloud-native applications, but typically lack built-in mechanisms for privacy preservation or machine learning integration. Our design bridges these gaps by combining differential privacy guarantees with microservice-based isolation in a distributed ML framework tailored for IIoT applications. By doing so, we address the limitations of monolithic ML pipelines and provide a cohesive architecture capable of secure data handling, flexible deployment, and low-latency inference across heterogeneous computing environments.

Radial basis function network (RBFN)

Radial Basis Function Networks (RBFNs) are a class of feedforward artificial neural networks that consist of three sequential layers: an input layer, a hidden layer with radial basis activation functions, and a linear output layer37. As shown in Fig. 2, this architecture is particularly well-suited for modelling complex, non-linear relationships in data. It has been widely applied in various domains such as function approximation, pattern recognition, time-series prediction, and classification due to its interpretability and fast convergence during training15.

Input layer: The input layer serves as the entry point for the feature vectors extracted from the dataset. Each neuron in this layer corresponds to one dimension of the input space. This layer does not perform any transformation or computation it simply transmits the input data to the subsequent hidden layer10.

Hidden layer: The hidden layer is the core computational component of the RBFN. Each neurone in this layer is associated with a centre vector, and it computes its activation using a radial basis function-most commonly the Gaussian function8. The response of a hidden neuron is determined by the Euclidean distance between the input vector and its associated centre. Formally, the activation \(\phi (x)\) of a hidden neuron for input x and center c is computed as:

where \(\sigma\) is the spread (or width) of the Gaussian kernel. The Gaussian activation ensures that the neuron is highly responsive to inputs that are close to its center and less responsive to distant inputs, allowing the network to learn localized representations of the input space.

Output Layer: The output layer linearly combines the responses of all hidden neurons to produce the final output. This can be expressed mathematically as:

where M is the number of hidden neurons, \(w_j\) are the weights connecting the hidden layer to the output neuron, and \(\phi _j(x)\) is the activation of the \(j^{th}\) hidden neuron for input x. The weights are typically learned using a closed-form solution such as Least Squares Linear Regression (LSLR), which minimizes the mean squared error between the predicted and actual output values6.

The RBFN’s ability to localize learning through its Gaussian basis functions gives it an advantage in capturing non-linear patterns efficiently with fewer parameters than fully connected deep networks. Moreover, its structure supports modular design and fast training, which makes it highly suitable for edge-based deployment scenarios in resource-constrained environments4.

Training involves two phases: (i) center selection via K-means++ and spread computation (Eq. (1)); and (ii) weight estimation using Least Squares Linear Regression (Eq. (3)). During the first phase, the spread parameter \(\sigma\) is computed to control the width of each radial basis function, enabling localized response behavior in the hidden layer. Gaussian activation, which transforms the input feature space into a non-linear manifold, is defined in Eq. (2). Once the RBF activations are computed, the second phase involves solving a convex optimization problem to estimate output weights that minimize the mean squared prediction error. The final network prediction is obtained using Eq. (4). This fast, modular approach offers closed-form solutions, making it computationally efficient and well-suited to edge-based, privacy-aware applications33. Moreover, it supports seamless integration with differentially private mechanisms, enabling robust inference without sacrificing individual data confidentiality.

Differentially private RBFN training and deployment

Figure 3 illustrates the training pipeline of the proposed RBFN framework, which integrates differential privacy mechanisms at multiple stages. Privacy is enforced by injecting calibrated Laplace noise into both the RBF activations and the output weight matrix, thereby protecting sensitive features and labels during model training34. The framework supports distributed execution across edge and cloud components using lightweight, containerized microservices. The end-to-end pipeline, shown in Fig. 4, enables secure, scalable, and low-latency inference in Industrial IoT (IIoT) environments. It includes key stages such as data standardization, differentially private perturbation, microservice communication via gRPC, and dynamic deployment to heterogeneous computing nodes. This modular architecture ensures compliance with privacy constraints while maintaining accuracy and robustness, making it suitable for real-time analytics in domains like smart manufacturing and remote health monitoring35.

Step 1: Center and spread computation

Equation (1) computes the spread \(\sigma\) of Gaussian RBFs based on the maximum pairwise distance among cluster centers36.

Equation (2) defines the Gaussian radial basis function used in the hidden layer neurons.

Step 2: Weight estimation

Equation (3) provides the least squares solution to compute output weights from RBF activations and true labels.

Equation (4) defines how predictions are generated from learned weights and Gaussian activations23.

Differential privacy mechanism

Differential Privacy (DP) ensures that a model’s output does not change significantly with the addition or removal of a single datapoint. The formal definition is provided below:

Equation (5) defines \(\varepsilon\)-differential privacy for any two neighboring datasets.

Equation (6) quantifies the maximum output difference (sensitivity) for neighbouring datasets.

Equation (7) applies the Laplace mechanism to preserve privacy by adding calibrated noise.

Equation (8) represents the probability density function of the Laplace distribution.

This property guarantees that post-processing of a differentially private output still satisfies \(\varepsilon\)-DP.

Glossary of symbols and notations

An RBFN framework enabled by microservices that preserves user privacy

This section describes our microservice-supported privacy-preserving Radial Basis Function Network (RBFN) framework (Fig. 5). The framework uses microservices and Differential Privacy (DP) to address healthcare data privacy problems. After describing the framework’s layout, we evaluate its mathematical ideas and computational complexity.

Summary of the framework

The proposed privacy-preserving Radial Basis Function Network (RBFN) architecture is shown in Fig. 5, with four layers: IoT, Data Aggregation, Application, and Privacy Preservation. These layers collaborate to securely process vast amounts of sensitive healthcare data. The main functions of layers are:

IoT layer

The IoT Layer is the system’s basis and comprises all IoT devices that create healthcare data, such as wearable tech sensors or medical equipment. The data is partitioned into smaller pieces before being sent to the second layer for further processing. The primary goal of the IoT layer is to collect and organise healthcare data in real-time for additional analytics that prioritise patient privacy.

Privacy-preservation (PP) layer

The responsibility for safeguarding privacy lies with the PP layer. This second layer ensures the confidentiality of IoT data collected through edge computing. It is composed of numerous private edge servers. The set \(\mathcal {E} = \{E_1, E_2, \ldots , E_m\}\) represents the edge servers, which are located close to the IoT data sources. Every edge server \(E_i\) runs a Randomised Training Microservice (RTMS) that applies Differential Privacy (DP) techniques to the local Internet of Things (IoT) data. Before sending the data to the next layer, the RTMS makes adjustments to ensure its privacy. As shown in Algorithm 1, this is the RTMS pseudocode. Every edge server calculates the perturbed outputs, which comprise noisy centre points (\(C^*_L\)) and noisy weights (\(W^*_L\)), after getting a data segment \(X_i\) from the IoT layer. The RTMS uses a supervised learning method to find the middle points of data segments by utilising the Laplace mechanism, which ensures differential privacy.

1. The Centres’ Sensitivity:

2. How the Sigma Equation Influenced the equation

is used. The variables represent key components involved in dataset processing and analysis. Center sensitivity, denoted as \(\Delta C\) in Eq. (10), quantifies how much the central points of the dataset vary in response to specific changes. The symbol \(\Delta \sigma\) in Eq. (11) represents the sensitivity of the standard deviation (sigma), which is related to data variability or dispersion. The data point \(x_i\) refers to the i-th observation in the dataset, where n denotes the total number of data points.

In Fig. 6, the dataset includes two segments with distinct centres, \(\text {cent}_i\) and \(\text {cent}_j\), and a total count of centres, CentresNum. The distance between two centres is measured using the notation \(\Vert \text {cent}_i - \text {cent}_j\Vert\). The sum operation (represented by \(\Sigma\)) combines values in a dataset, while \(\max\) represents the highest value within or between two values. These variables together give a rich framework for studying the dataset’s structure, dynamics, and linkages. These computations properly account for data sensitivity, which determines noise inclusion. After data disruption, the Knowledge Aggregation layer processes distorted centres and weights.

Aggregating knowledge (KA) layer

The KA layer must combine the changed privacy-preservation layer data. Public edge servers combine differentially private outputs from private edge servers. This layer creates a comprehensive model with updated centres and weights for analysis and decision-making. After aggregation, the application layer processes the data.

Applications layer

Applications Layer Data from the App layer is used to train the final RBFN model. This layer performs health monitoring and disease prediction for the machine learning model. The cloud architecture’s microservices analyse data and predict using the trained model. With this layer, healthcare apps may trust the global model for real-time predictions. The framework’s edge-cloud connection offers efficient edge data processing while protecting privacy with differential privacy. For healthcare privacy-sensitive applications, the suggested approach carefully processes sensitive data at every level and never exposes it in its raw form.

To enhance the mathematical clarity of Algorithm 1 (Randomised Training Microservice – RTMS), we reformulated it as a structured step-by-step procedure. This includes initialization, class-wise centre computation, sensitivity estimation, Laplace noise generation, and perturbation of both centres and weights. Variables such as \(\mathcal {X}_i\) (features), \(\mathcal {Y}_i\) (labels), \(\Delta _C\) (sensitivity), \(\varepsilon\) (privacy budget), \(\sigma\) (noise scale), \(W^*_L\) (perturbed weights), and \(C^*_L\) (perturbed centres) are explicitly defined and consistently applied. The algorithm assumes (i) edge nodes hold labelled, independent data; (ii) local differential privacy is enforced using the Laplace mechanism; and (iii) sensitivity is bounded as discussed in “Radial basis function network (RBFN)” section. The computational complexity is \(\mathcal {O}(n \cdot d)\), accounting for centre computation and perturbation, where n is the sample size and d is the feature dimension. These refinements improve the reproducibility and transparency of the proposed microservice-based framework.

Knowledge aggregation (KA) layer

The Knowledge Aggregation (KA) layer, forming the third tier of the architecture, is responsible for synthesizing data from the Privacy-Preservation (PP) layer, selecting the optimal Radial Basis Function (RBF) model, and finalizing the trained model. This layer operates via a cloud server and a distributed set of Privacy-Enhancing Servers (PES), denoted as \(E^{p} = \{ E^{p}_1, E^{p}_2, \ldots , E^{p}_s \}\). It incorporates three core microservices. The Data Aggregation Microservice (DAMS) collects perturbed centers C and noisy weights W from PP-layer edge servers. Each DAMS at a PES computes intermediate aggregates (\(C^*\) and \(W^*\)), which are then forwarded to the cloud. The cloud-based DAMS finalizes the aggregation to produce \(C_F^*\) and \(W_F^*\), and stores subsequent analytics. The Building Microservice (BMS) uses these aggregated values to construct the trained RBF model, also stored in the cloud. Finally, the Service Selection Microservice (SELMS) evaluates all candidate RBF models and selects the most accurate one for deployment, ensuring optimal performance in real-world applications.

Application lyer

The cloud-hosted app layer is the fourth and final tier. This tier hosts the cloud-hosted machine learning microservice MLaMS, which interacts with users. MLaMS evaluates sensor readings and medical data to provide predictions at a user’s request using the trained RBF model. MLaMS can forecast an illness’s likelihood and provide the user with the outcome using user input. The proposed method uses layers to improve privacy and speed data processing. The framework’s four layers-IoT, PP, KA, and App-protect privacy and process data efficiently. The inability to send data to third parties or public edge servers defines this system. Transmitting only altered outputs through layers protects privacy from external attacks. The use of \(\varepsilon\)-differential privacy (DP) achieves this goal by balancing privacy with accuracy using a low epsilon number. An improvement in privacy protection is achieved by including randomised outputs at each level. Even if attackers gain access to the outputs, they will still be unable to infer the actual data due to the randomisation of the outputs generated by the previous layer. Additionally, overall efficiency is improved since future layers process significantly less data when only a piece of the dataset is transmitted instead of the whole dataset.

Consider the PP layer; it contains d pieces of data. The data points must be processed by private edge servers (E) that use the Randomised Training Microservice (RTMS). Once the PP layer generates m local outputs, it transfers them to the KA layer. Data is further consolidated in the KA layer by use of PES. With \(A = \frac{m}{\text {numPES}}\) We can represent the set of inputs received by the PES. After handling its assigned inputs, each PES generates several outputs that are sent to the server in the cloud for further processing. Without this design, transferring the whole dataset (d) to the cloud would be required, which would entail sending every single data point. Not only would this put privacy at risk, but it would also increase communication overhead. The system ensures that only necessary information is delivered by limiting the data conveyed at each layer and using randomised outputs, which improves performance and privacy.

To improve the clarity and reproducibility of Algorithm 2 (Data Aggregation Microservice – DAMS), we have revised its structure with formal mathematical notation and step-wise descriptions. The algorithm handles two aggregation scenarios: (i) local aggregation at edge nodes using \(W^*_L\) and \(C^*_L\), and (ii) global aggregation at the cloud using \(W^*_{Ij}\) and \(C^*_{Ij}\). Final outputs are denoted as \(W^*_F\) and \(C^*_F\). Assumptions include (a) inputs are perturbed via a trusted microservice, (b) aggregation functions are deterministic and privacy-preserving, and (c) secure communication is ensured by microservice orchestration. The computational complexity is \(\mathcal {O}(m \cdot d)\) at the edge and \(\mathcal {O}(m' \cdot d)\) at the cloud, yielding a total of \(\mathcal {O}((m + m') \cdot d)\). These refinements enhance algorithm precision, completeness, and applicability.

Framework analysis

The privacy guarantees and computing cost of the proposed privacy-preserving RBFN paradigm are evaluated here. Table 3 shows the framework’s mathematical notations for clarity. We evaluate how well the system preserves user privacy while retaining computer efficiency at all levels.

Differential privacy analysis

The proposed model achieves Differential Privacy (DP) by injecting Laplace noise into the RBFN parameters, particularly the centres (C) and standard deviation (\(\sigma\)), preventing data reconstruction. For two adjacent datasets \(D_1\) and \(D_2\), differing by one element, the model satisfies \(\epsilon\)-DP if:

To achieve this, Laplace noise is applied as:

where \(\Delta C\) is the sensitivity of f(D). For the mean of n samples, \(\Delta C\) becomes:

From this, the output probability ratio becomes:

ensuring \(\epsilon\)-DP. Since RBFN parameters (C, \(\sigma\)) are privatised, and due to the post-processing property, downstream outputs like \((C^*, W^*)\) also satisfy \(\epsilon\)-DP. Finally, the sensitivity of the standard deviation \(\sigma\) is:

This ensures appropriate noise calibration for robust privacy protection in RBFN-based IIoT systems.

Evaluation of computing difficulty

To assess system efficiency, we analyze the computational complexity of the proposed model using Big O notation. For variables I, K, S, and F, the baseline K-means clustering algorithm without privacy mechanisms exhibits a temporal complexity of \(O(I \cdot K \cdot S \cdot F)\). In contrast, a supervised method has complexity O(L), where L denotes the number of class labels. The proposed private decentralized framework incorporates multiple components: the IoT and Privacy-Preservation (PP) layer has a complexity of \(O(D + L + K^2)\) based on the number of data points (D), labels (L), and centers (K); the Public Edge Servers (PES) in the Knowledge Aggregation (KA) layer contribute a complexity of O(A) for segment analysis; and the cloud layer, receiving inputs from the PES nodes, adds a complexity of O(N). Thus, the overall computational complexity of the private model becomes \(O(D + L + K^2 + A + N)\).

Appropriateness for resource-limited devices

The system is designed for deployment in resource-constrained environments, with microservices serving as lightweight components that can efficiently operate on edge devices. By delegating privacy-preserving functions-such as real-time monitoring and sanitization (RTMS)-to the local device, the architecture minimizes computational overhead and network latency, making it well-suited for real-time analytics on constrained hardware.

Enhancing attack resistance through microservices

The proposed architecture emphasizes data privacy in the presence of both internal and external threats. Privacy-preserving mechanisms are embedded within the RTMS running on private edge servers, where differential privacy (DP) is applied locally to input data. Sensitive raw data is never transmitted beyond the private domain; only perturbed outputs, such as sanitized cluster centers and weights, are sent to the Data Aggregation Microservice (DAMS) within the Knowledge Aggregation (KA) layer. The cloud component then aggregates these noisy values to build the final model. This design ensures that even if an attacker compromises a public edge server or intercepts data transmissions, only obfuscated information is exposed-thus maintaining robust privacy guarantees across all system layers.

Adversary and threat model in privacy-preserving IIoT framework

In the context of our proposed differential privacy-enabled microservice architecture for Industrial IoT (IIoT) applications, we define a realistic adversary model that includes both honest-but-curious entities and malicious edge nodes. This dual-layered threat model captures the practical risks faced in distributed, cloud-edge environments handling sensitive data such as medical records or industrial telemetry. An honest-but-curious adversary is assumed to behave correctly according to the system protocol but attempts to extract sensitive information from observed data flows, model outputs, or shared gradients. For example, a cloud-based analytics service or an internal processing module might legally access DP-noised data but still try to perform statistical inference or membership attacks to learn individual records. This attacker may leverage auxiliary knowledge such as partial datasets or known distributions to increase inference accuracy, which poses a privacy risk even when differential privacy mechanisms are in place.

We also consider the presence of malicious edge nodes, which may actively deviate from expected behaviour. These nodes can inject poisoned data, manipulate local model updates, suppress legitimate inputs, or collude with other compromised components to reverse-engineer private information. Such adversaries pose a significant threat in decentralized networks, particularly where edge devices have direct access to raw sensor streams. In federated or collaborative learning setups, these nodes could compromise the integrity of the global model or reduce the effectiveness of DP by tampering with local computations. Our architecture mitigates these threats by employing strong differential privacy guarantees during both training and inference phases, ensuring that no single data point has a disproportionate influence on the model output. All communications between services and edge devices are secured using encrypted gRPC channels with mutual TLS, which prevents eavesdropping and tampering in transit. Microservice-based deployment ensures process isolation and modular trust boundaries, reducing the impact of a potential compromise. Furthermore, raw data never leaves the local edge environment; only privatized, differentially noisy representations or encoded gradients are communicated. This adversarial model reflects the practical concerns of IIoT deployments and underpins the design of our privacy-preserving framework, ensuring robustness against both passive and active privacy threats.

Experiments and findings

This section presents the evaluation of the proposed differentially private RBFN framework across centralized and distributed environments. We describe the experimental setup, datasets used, empirical results, and comparative benchmarking.

Experimental setup

Experiments were conducted on an Ubuntu 20.04.2-LTS machine (Intel i7-10750H, 16GB RAM, 150GB SSD) using Python 3.8 and PyCharm Pro 2020.3. The system leveraged Docker (v20.10.3), gRPC (v1.35.0), and gRPC tools (v1.16.1) to deploy a microservice-based inference pipeline. SMOTE was used to address class imbalance in the UCI Heart Disease and Heart Failure datasets. Datasets were split into 80% training and 20% testing. A distributed setup with one cloud server, three edge nodes, and an emulated private server enabled decentralized learning with differentially private mechanisms.

Datasets and evaluation protocol

We used a mix of real-world (UCI Heart Disease, Heart Failure, WISDM) and synthetic datasets (Synthetic-1, Synthetic-2) with varying sizes, features, and complexity. The WISDM dataset, with temporal sensor readings, added diversity and realism, while synthetic datasets helped simulate heterogeneous edge environments. Performance was measured using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and execution time.

Results and aalysis

Centralized centre selection impact

Figure 7 shows that K-means++ clustering achieved higher accuracy than supervised selection across datasets. For example, Heart Disease data achieved 96.72% accuracy with \(K=13\) using K-means++.

Analysis of accuracy of RBFN model versus privacy (centralized approach)

Figure 8 demonstrates the impact of varying the privacy budget (\(\epsilon\)) on model accuracy in a centralized setting. As expected, a lower \(\epsilon\)-indicating stronger privacy guarantees-resulted in greater noise addition and corresponding performance degradation. At \(\epsilon = 10^{-4}\), the model exhibited a substantial drop in accuracy across all datasets. However, as \(\epsilon\) increased to \(10^{-3}\) and above, the accuracy gradually improved and closely approached that of the non-private baseline. This trend highlights the inherent trade-off between privacy and utility in differential privacy mechanisms.

Analysis of accuracy of RBFN model versus privacy (distributed methodology)

Distributed RBFN testing with \(\epsilon \in \{0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7\}\) showed expected trade-offs: lower \(\epsilon\) values reduced accuracy. Results are shown in Figs. 9, 10, 11.

Impact of partitioning and ensemble methods

Table 4 shows how varying the number of data partitions and \(\epsilon\) impacts accuracy. For instance, Synthetic-1 with 21 partitions achieved 93.73% accuracy at \(\epsilon = 0.5\).

Framework efficiency

As illustrated in Fig. 12, the microservice-based deployment of the DP-RBFN model demonstrated superior efficiency compared to the monolithic approach. Specifically, the distributed architecture significantly reduced average inference latency and enhanced system scalability. This performance gain is attributed to containerized service orchestration, parallel processing across edge nodes, and efficient load balancing. The modular design also facilitated faster deployment and better fault isolation, making it more suitable for real-time IIoT applications.

Distributed scalability and latency

As shown in Table 5, increasing the number of edge nodes leads to improved model accuracy and reduced inference latency, demonstrating the scalability of the proposed framework. Additionally, the performance scales consistently across different privacy budgets (\(\epsilon\) values), confirming that the system maintains efficiency even under stricter privacy constraints. These results highlight the practicality of our microservice-based architecture for real-time, privacy-preserving IIoT deployments.

Statistical validation

As shown in Table 6, DP-RBFN consistently outperformed DP-MLP with lower standard deviation and tighter confidence intervals across 10 trials.

Deployment and comparative benchmarking

To evaluate the practical efficiency of the proposed DP-RBFN framework, we conducted a comparative analysis between monolithic and microservice-based deployments. The microservice architecture was implemented using Docker containers and gRPC interfaces, enabling modular, scalable, and distributed execution across edge and cloud nodes. In contrast, the monolithic version encapsulated all components within a single deployment unit.

As shown in Table 7, the microservice-based deployment achieved significant performance gains. Specifically, it reduced average inference latency by 23.5% compared to the monolithic approach (58.3 ms vs. 76.2 ms). Additionally, system throughput improved by 32.6% (17.1 vs. 12.9 requests per second), indicating better concurrency handling and scalability. This performance boost is primarily attributed to the parallelism, load balancing, and container level orchestration enabled by the microservice design. Furthermore, microservice deployment also yielded a 17.8% reduction in CPU utilization, demonstrating improved resource efficiency critical for edge-deployed systems. These results validate the architectural advantage of microservices in privacy-preserving IIoT applications, especially where responsiveness, modularity, and dynamic scaling are required.

Comparison with DP-enabled MLP baseline

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed DP-RBFN model, we compared its performance against a Differential Privacy-enabled Multilayer Perceptron (DP-MLP) using an identical privacy budget of \(\varepsilon = 5\). As summarized in Table 8, DP-RBFN achieved higher accuracy (92.6%) and lower inference latency (38 ms) compared to DP-MLP (90.2%, 52 ms). Both models experienced an equal accuracy degradation of 1.8% due to the privacy mechanism, but DP-RBFN demonstrated superior computational efficiency.

Comparative performance analysis

We further benchmarked DP-RBFN against DP-MLP under a stricter privacy budget (\(\varepsilon = 0.5\)), evaluating classification accuracy, standard deviation, latency, throughput, and accuracy loss. Table 9 illustrates that DP-RBFN achieved higher accuracy (93.21%), lower latency (58.3 ms), and better throughput (17.1 inf/sec) than DP-MLP. Moreover, DP-RBFN showed reduced accuracy loss (2.8%) compared to DP-MLP (4.1%), confirming its robustness to DP-induced noise and suitability for IIoT deployments.

To evaluate the individual impact of core framework modules RTMS, DAMS, and SELMS an ablation study was conducted. We selectively disabled each component and measured its effect on latency, accuracy, and CPU usage. The results, summarized in Table 10, reveal that all three modules contribute significantly to system performance and privacy preservation, with SELMS showing the highest impact on accuracy. Furthermore, to address concerns regarding system scalability and real-time performance, we analyzed how increasing the number of deployed microservices affects latency and throughput. Table 10 provides a detailed breakdown, including standard deviation to reflect runtime variability. The results demonstrate improved performance and stability with increased microservice parallelism.

Practical deployment and integration considerations

To validate the feasibility of our proposed framework in real-world IIoT environments, we developed and documented a detailed deployment walkthrough. A functional prototype was implemented using Raspberry Pi 4 devices as edge nodes, paired with a cloud-based AWS EC2 instance acting as the central aggregator and analytics hub. This hybrid edge-cloud configuration reflects realistic deployment scenarios in smart healthcare and industrial IoT ecosystems. The entire system was containerized using Docker, with each service (e.g., data ingestion, privacy enforcement, model inference) running in its own isolated microservice container. These components communicate securely using gRPC, which supports efficient, lightweight data transmission between the edge and cloud layers. The simulated data flow involved both real-world and synthetic healthcare sensor streams, demonstrating the architecture’s ability to handle high-frequency, privacy-sensitive data at scale.

To ensure robustness, several key integration aspects were addressed. These include container-level security to prevent unauthorized access and execution, synchronization mechanisms between distributed nodes to maintain model consistency and privacy budget alignment, and system resilience in the face of edge node failures or network variability. The results indicate that our microservice-based design facilitates scalable, low-latency inference while preserving user privacy across distributed IIoT infrastructures. In addition to implementation details, we also discuss broader integration challenges that may arise during real-world deployments. These include regulatory compliance for medical data handling, hardware heterogeneity among edge devices, and ensuring maintainability and adaptability in dynamic production environments. This section not only reinforces the architectural soundness of our solution but also highlights its readiness for practical, secure, and intelligent IIoT adoption.

Conclusion

This study introduces a thorough, service-oriented microservice framework for the implementation of differential privacy in Industrial IoT (IIoT) systems, specifically targeting smart and healthcare applications inside edge-cloud contexts. This paper demonstrates a viable approach to safe, privacy-conscious data processing in real-world IIoT implementations by incorporating differential privacy (DP) into centralised and distributed machine learning processes via scalable microservices. The suggested multi-tiered design enables microservices to manage machine learning and privacy protection functions at both edge and cloud layers, hence improving modularity and scalability. Experimental assessments utilising both real-world and synthetic datasets in centralised and decentralised settings demonstrate significant trade-offs among privacy, accuracy, and system performance.

Lower privacy budgets (\(\epsilon < 0.5\)) resulted in diminished accuracy, whereas the framework consistently attained satisfactory performance with moderate privacy settings (\(\epsilon \ge 0.5\)), preserving accuracy akin to non-private baseline models. The decentralised microservice architecture enhanced execution speed and computational efficiency, especially as the number of microservice instances increased, while also facilitating localised data processing, which is essential for latency-sensitive and privacy-restricted IIoT settings. Nevertheless, distributed models exhibited heightened sensitivity to noise as a result of partitioning, highlighting the necessity for meticulous system design. The findings confirm the efficacy of the suggested microservice-oriented paradigm in achieving a balance among privacy, accuracy, and efficiency for privacy-preserving collaborative learning in IIoT. Future research may investigate dynamic privacy adaptation, optimised model partitioning, and real-time orchestration to enhance the trade-offs in large-scale, data-intensive industrial settings (Supplementary Information).

Data availability

The datasets used in this study comprise both real-world and synthetic sources. The real-world datasets are publicly accessible and include the UCI Heart Disease Dataset, available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/redwankarimsony/heart-disease-data?resource=download; the Heart Failure Clinical Records Dataset, available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/rithikkotha/heart-failure-clinical-records-dataset; and the WISDM (Wireless Sensor Data Mining) Dataset, available at https://www.cis.fordham.edu/wisdm/dataset.php. In addition to these, two synthetic datasets, Synthetic-1 and Synthetic-2, were generated to simulate heterogeneous and privacy-sensitive edge environments. These synthetic datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All datasets were utilized to evaluate the proposed framework’s performance across metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and execution time.

References

Gad, A. G., Houssein, E. H., Zhou, M., Suganthan, P. N., & Wazery, Y. M. Damping-assisted evolutionary swarm intelligence for industrial IoT task scheduling in cloud computing. IEEE Internet Things J.. 11(1), 1698–1710 https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2023.3291367 (2024).

Kaur, A. Intrusion detection approach for industrial internet of things traffic using deep recurrent reinforcement learning assisted federated learning. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 6(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAI.2024.3443787 (2025).

Samanta, A. & Nguyen, T. G. Trust-based distributed resource allocation in edge-enabled IIoT networks. IEEE Access 13, 79694–79704. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3567068 (2025).

Sun, Zongkun, Wang, Yinglong, Shu, Minglei, Liu, Ruixia & Zhao, Huiqi. Differential privacy for data and model publishing of medical data. IEEE Access 7, 152103–152114 (2019).

Acar, A., Celik, Z. B., Aksu, H., Uluagac, A. S. & McDaniel, P. Achieving secure and differentially private computations in multiparty settings. In 2017 IEEE Symposium on Privacy-Aware Computing (PAC), 49–59 (IEEE, 2017).

Sun, Z.-H., Chen, Z., Cao, S. & Ming, X. Potential requirements and opportunities of blockchain-based industrial IoT in supply chain: A survey. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 9(5), 1469–1483. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSS.2021.3129259 (2022).

Xenofontos, C. et al. Consumer, commercial, and Industrial IoT (in)security: Attack taxonomy and case studies. IEEE Internet Things J. 9(1), 199–221 (2022).

Yang, Yilong, Quan, Zu., Liu, Peng, Ouyang, Defang & Li, Xiaoshan. Microshare: Privacypreserved medical resource sharing through microservice architecture. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 14(8), 907–919 (2018).

Yan, C., Xia, Y., Yang, H. & Zhan, Y. Cloud control for IIoT in a cloud-edge environment. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 35(4), 1013–1027. https://doi.org/10.23919/JSEE.2024.000074 (2024).

Laili, Y. et al. Parallel scheduling of large-scale tasks for industrial cloud-edge collaboration. IEEE Internet Things J. 10(4), 3231–3242. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2021.3139689 (2023).

Zanasi, C., Russo, S. & Colajanni, M. Flexible zero trust architecture for the cybersecurity of industrial IoT infrastructures. Ad Hoc Netw. 156, 103414 (2024).

Hästbacka, D. et al. Dynamic edge and cloud service integration for industrial IoT and production monitoring applications of industrial cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 18(1), 498–508. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2021.3071509 (2022).

Abbas, G., Ali, M., Ahmad, M. & Khan, A. CIRA-cyber intelligent risk assessment methodology for industrial internet of things based on machine learning. IEEE Access 13, 77001–77016. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3559617 (2025).

Ortiz, G., Caravaca, J. A., García-de-Prado, A., de la Chavez, O. F. & Boubeta-Puig, J. Real-time context-aware microservice architecture for predictive analytics and smart decision-making. IEEE Access 7, 183177–183194 (2019).

Kayode Saheed, Y. & Ebere Chukwuere, J. CPS-IIoT-P2Attention: Explainable privacy-preserving with scaled dot-product attention in cyber-physical system-industrial IoT network. IEEE Access 13, 81118–81142. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3566980 (2025).

Giaretta, N., Dragoni, J., & Massacci, F. Protecting the Internet of Things with security-by-contract and Fog computing. In Proc. IEEE World Forum Internet Things, 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1109/WF-IoT.2019.8767243 (2019).

Vistbakka, I. & Troubitsyna, E. Formalising privacy-preserving constraints in microservices architecture. In Formal Methods and Software Engineering (eds Lin, S.-W. et al.), 308–317 (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Li, K., Zhang, Y., Huang, Y., Tian, Z. & Sang, Z. Framework and capability of industrial IoT infrastructure for smart manufacturing. Standards 3(1), 1–18 (2023).

Awaisi, K. S., Ye, Q. & Sampalli, S. A survey of industrial AIoT: opportunities, challenges, and directions. IEEE Access 12, 96946–96996. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3426279 (2024).

Jarwar, M. A., Watson, J. & Ali, S. Modeling industrial IoT security using ontologies: a systematic review. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 6, 2792–2821. https://doi.org/10.1109/OJCOMS.2025.3532224 (2025).

Kumar, P., Mullick, S., Das, R., Nandi, A. & Banerjee, I. IoTForge pro: A security testbed for generating intrusion dataset for industrial IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 12(7), 8453–8460. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2024.3501017 (2025).

Ismail, S., Dandan, S., Dawoud, D. W. & Reza, H. A comparative study of lightweight machine learning techniques for cyber-attacks detection in blockchain-enabled industrial supply chain. IEEE Access 12, 102481–102491. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3432454 (2024).

Gupta, A. & Chaturvedi, Y. Cloud-Native ML: Architecting AI Solutions for Cloud-First Infrastructures. Vol. 20, 930–939. https://doi.org/10.62441/nano-ntp.v20i7.4004 (2024). .

Krishnan, P., Jain, K., Achuthan, K. & Buyya, R. Software-defined security-by-contract for blockchain-enabled MUD-aware industrial IoT edge networks. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 18(10), 7068–7076. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2021.3084341 (2022).

Yao, P. et al. Security-enhanced operational architecture for decentralized industrial internet of things: a blockchain-based approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(6), 11073–11086. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2023.3329352 (2024).

Lai, Q. H., Lai, C. S. & Lai, L. L. Smart Health Based on Internet of Things (IoT) and Smart Devices 425–462 (Wiley, XXX, 2023).

Elouardi, S., Motii, A., Jouhari, M., Amadou, A. N. & Hedabou, M. A survey on hybrid-CNN and LLMs for intrusion detection systems: recent IoT datasets. IEEE Access 12, 180009–180033. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3506604 (2024).

Ghosh, S., Islam, S. H. & Vasilakos, A. V. Private blockchain-assisted certificateless public key encryption with multikeyword search for fog-based IIoT environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(19), 30847–30863. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2024.3415676 (2024).

Ismail, S., Dandan, S. & Qushou, A. Intrusion detection in IoT and IIoT: Comparing lightweight machine learning techniques using TON_IoT, WUSTL-IIOT-2021, and EdgeIIoTset datasets. IEEE Access 13, 73468–73485. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3554083 (2025).

Luo, S., Zeng, P., Ma, C. & Wei, Y. Anomaly detection for industrial Internet of Things devices based on self-adaptive blockchain sharding and federated learning. J. Commun. Netw. 27(2), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.23919/JCN.2025.000019 (2025).

Shah, S., Madni, S. H. H., Hashim, S. Z. B. M., Ali, J. & Faheem, M. Factors influencing the adoption of Industrial Internet of Things for the manufacturing and production small and medium enterprises in developing countries. IET Collab. Intell. Manuf. 6(1), e12093 (2024).

Sun, J. F., Yuan, Y. & Tang, M. J. Privacy-preserving bilateral finegrained access control for cloud-enabled IIOT healthcare. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 18(9), 6483–6493 (2022).

Goel, P., Khatri, D. K., Gangu,K., Ayyagiri, A., Mokkapati, C., & Hussien, R. R. Secure edge IoT intrusion detection framework for industrial IoT via blockchain integration. In 2024 4th International Conference on Blockchain Technology and Information Security (ICBCTIS), Wuhan, China, 307–313 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICBCTIS64495.2024.00055 (2024).

Taherdoost, H. The role of blockchain in medical data sharing. Cryptography 7(3), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryptography7030036 (2023).

Dwork, C., McSherry, F., Nissim, K., & Smith, A. Calibrating noise to sensitivity in private data analysis. In Theory of Cryptography. TCC 2006. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, (eds Halevi, S. & Rabin, T.) vol 3876. https://doi.org/10.1007/11681878_14 (Springer, 2006).

Sabuhi, M., Musilek, P. & Bezemer, C.-P. Micro-FL: A fault-tolerant scalable microservice-based platform for federated learning. Future Internet 16(3), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi16030070 (2024).

Cao, X., Wang, J., Cheng, Y. & Jin, J. Optimal sleep scheduling for energy-efficient AoI optimization in industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 10(11), 9662–9674 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Vara Prasada Rao K: Software, Validation, Data Curation Vara Prasada Rao K implemented the system components, conducted experimental evaluations using real and synthetic datasets, and was responsible for data preprocessing and validation of the results. Veera Ankalu Vuyyuru: Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing-Review & Editing Veera Ankalu Vuyyuru contributed to the formal analysis of privacy metrics and model performance. They created the visualizations and contributed significantly to manuscript revisions and refinement. Beakal Gizachew Assefa: Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition Beakal Gizachew Assefa supervised the overall project execution, provided critical feedback throughout all phases of the research, managed the project timeline, and secured funding for the research activities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murala, D.K., Prasada Rao, K.V., Vuyyuru, V.A. et al. A service-oriented microservice framework for differential privacy-based protection in industrial IoT smart applications. Sci Rep 15, 29230 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15077-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15077-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

MedShieldFL-a privacy-preserving hybrid federated learning framework for intelligent healthcare systems

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Intelligent cybersecurity management in industrial IoT system using attribute reduction with collaborative deep learning enabled false data injection attack detection approach

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

ChainShieldML an intelligent decentralized security framework for next generation wireless sensor networks

Scientific Reports (2025)