Abstract

Visible and infrared image fusion (VIF) aims to fuse the complementary features of the source images into one image with richer information. The fused image has both contour and texture detail information from the visible image and the thermal radiation information of the target or background from the infrared image. Meanwhile, the color visible image has color information that is more in harmony with human’s subjective visual perception. Most of the existing VIF methods focus on the processing of salient targets and texture details based on the grayscale channel, ignoring the fusion of the color information of the source images. This paper proposes a novel visible and infrared image fusion method Fusion with Preserved Hue, termed PHFuse, which can fuse and preserve abundant color information while fusing intensity and gradient information. Specifically, we design a new fusion process using the characteristics of the HSV color space, which performs more targeted fusion calculations on chromaticity and intensity information separately. In addition, we design a channel fusion branch, which can iterate the fusion strategy adaptively. We introduce the spectral angle mapping loss function in the fusion network, realize unsupervised training in fusing the color information. Subjective and objective evaluations on public datasets show that compared with current state-of-the-art methods, the PHFuse proposed in this paper can generate fused images with richer colors, and the intensity gradient information fusion performance is no less than that of the SOTA method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In engineering applications, it is common to use both visible and infrared image sensors simultaneously to capture more comprehensive information from the same scene. Visible images are typically in color and provide abundant contour and texture details, aligning with human visual perception. Infrared images are sensitive to temperature variations, enabling the detection of thermal objects even in environments with occlusions or low light. To integrate the information from both types of images into a single composite image, methods for fusing visible and infrared images have been developed. These methods enhance the image, facilitating interpretation and providing richer information for subsequent image processing tasks. Currently, visible and infrared image fusion is widely utilized in various fields, including target detection1,2, target tracking3, video surveillance4,5, remote sensing imagingtarget tracking6, autonomous driving7 and other fields.

Over the years, many VIF methods have been proposed. Commonly used VIF methods include multi-scale transformation methods8,9, sparse representation methods10,11, saliency-based methods12,13, deep learning-based methods14, and hybrid methods15,16. Among these, deep learning methods have gained considerable attention from researchers due to their powerful nonlinear feature extraction capabilities and excellent model flexibility. In VIF tasks based on deep learning, researchers develop sophisticated loss functions to enforce effective constraints, employ Encoder-Decoder structures to manage nonlinear features, and introduce attention and self-attention mechanisms to enhance network performance17,18,19,20,21. These advancements solve the problems such as the lack of reference for training, deficiencies in fused image details, and weak expression of complementary information, thereby significantly improve the quality of fused images in VIF tasks.

In early VIF tasks, visible images were typically grayscale images in the panchromatic band, containing only the scene’s intensity information22. With advancements in sensor and computing technologies, more recent VIF tasks use color images as source visible images, which are in three-channel RGB format and contain not only intensity information but also rich color information23,24. Meanwhile, infrared images are usually single-channel grayscale images, which convert infrared light into visible grayscale images that can be perceived by human eyes, representing the intensity of infrared light. Thus, the images to be fused are color images and grayscale images respectively. This inconsistency in source images leads to the problem with channel dimensions and color information mismatch.

In order to solve the issue above, numerous methods have been proposed. Currently, the commonly used method is to convert the visible image from RGB format to YCbCr format for processing25,26. In the YCbCr color space, Y refers to the luminance component channel, which represents intensity information. Cb and Cr represent the chrominance channels for blue-yellow and red-yellow color-difference, respectively27. After converting the color space, the obtained Y channel is fused with the infrared image, and the obtained single-channel fusion result is used as the Y channel of the fused image. This approach standardizes the source images to a single-channel format, solves the issue of channel dimension mismatch in fusion.

Figure 1 shows the results of fusing a pair of visible and infrared images shown in Figure 1(a) using several typical image fusion methods. For the chrominance channels Cb and Cr, there are two fusion processing methods: one is to perform weighted fusion of the Cb and Cr channels of the visible image and the infrared image separately25,28, the other is to directly use the Cb and Cr channels of the visible image as the Cb and Cr channels of the fused image17,26,29. The former weighted fusion method has limited interpretability and performs poorly in the VIF task, as it merges the chrominance of the infrared image into the fused image. Since the grayscale infrared image does not contain color information, such weighted fusion results in a fused image with an overall gray tone, which does not align with human visual perception. The method used in IFCNN25 as shown in Figure 1(b) is an example of this approach. Its fusion result shows that both the person and the background appear gray and lack color richness. The second method addresses this issue by directly copying the Cb and Cr channels from the visible image to the fused image, thereby inheriting all color information from the visible image. However, this method does not perform as perfectly as expected. The fusion result of TarDAL method26 that directly copies the chrominance channel is shown in Figure 1(c). Although the color richness is improved compared to Figure 1(b), it still fails to fully overcome the grayish tone issue. Particularly in areas where brightness is enhanced, such as the person’s clothing in Figure 1(c), the fusion of infrared image pixel intensity information overwhelms the original red color of the clothing in the visible image. Therefore, compared with the result obtained by our method as shown in Figure 1(d), these two processing methods for image chrominance have limitations in accurately expressing color information and do not effectively inherit the image colors from the visible image.

In addition, other color processing methods have been proposed for VIF tasks. For example, fusion methods using color spaces such as CIELab30, IHS31, and HSV32 have been explored. However, these methods still involve separating the luminance and chrominance of the visible image and then performing fusion on the luminance channel, which is essentially no different from YCbCr methods. Some have also proposed using color transfer methods to incorporate color information from the visible image into the fusion result33,34. This approach, however, adds an extra processing step after image fusion, thereby increasing the complexity of the image processing workflow.

Based on these problems, this paper proposes a new VIF method. We name this fusion method as Fusion with Preserved Hue, abbreviated as PHFuse. PHFuse is based on the HSV color space and retains the hue channel while fusing the saturation and value or luminance channels. It combines the loss function with image color space transformations, allowing the network to process both color and intensity information from the source images. Additionally, PHFuse features a branch network structure for fusion, which integrates seamlessly with deep learning networks and improves the method’s capability to handle nonlinear structures.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows,

1. A novel VIF process is proposed which performs fusion calculations using color space transformations and the preservation and processing of image channels, along with a deep learning based branch structure. This process not only fuses the intensity information of the source images but also efficiently fuses the color information in a more targeted manner.

2. A fusion branch suitable for PHFuse is designed, which employs an encoder-decoder network combined with dense blocks and attention modules. This architecture can implicitly obtain the optimal solution for color information fusion through iteration, effectively enhancing the overall efficiency and performance of the fusion process.

3. A loss function for color information, Spectral Angle Mapping Loss, is introduced for fusion training. It adds constraints on spectral angle similarity in VIF unsupervised training, so that the branch network can process color information.

Experimental result shows that compared with the SOTA fusion method, our proposed PHFuse achieves better results in preserving and highlighting image color information, providing a new path for color VIF tasks.

Related works

HSV color space introduction and color conversion

HSV is a color image format or a color space that describes colors using three dimensions: Hue, Saturation, and Value. Hue determines the color’s attribute or type, representing the dominant color perceived by human. Saturation refers to the purity of the color; the less white light a color contains, the closer it is to the pure hue, resulting in higher saturation. Value represents the brightness or lightness of the color, related to the perceived intensity of light. Higher value means the color appears brighter. Colors defined by these three dimensions are known as HSV colors, and the collection of these colors is referred to as the HSV color space.

According to the definition of Alvy et.35, the conversion from RGB to HSV is as Algorithm 1.

The conversion from HSV to RGB is as Algorithm 2.

Attention module and triplet attention

In image processing tasks related to deep learning, attention modules imitate human visual and focus on salient areas by dynamically adjusting the weights of input image features36. Common attention modules such as SEblock37 and CBAM38 can calculate spatial and channel attention for images. They have plug-and-play advantages are widely used in VIF tasks.

Triplet Attention39 is an attention module that utilizes residual connections to calculate attention weights for input feature blocks. Different from other modules, Triplet Attention rotating the input feature block of size C\(\times\)H\(\times\)W to calculate three pairs of different channel relationship: HW, CW and HC, and then averages the results to produce the output feature block. This method also has the plug-and-play advantage, allowing it to be easily inserted as an additional module into a network. The efficient and convenient Triplet Attention enhances the network’s focus on salient feature areas, thereby improves network performance.

The proposed method

Fusion process of PHFuse

We propose the PHFuse fusion method using the HSV color space. In contrast to the chroma channels (Cb and Cr) in YCbCr color space, hue and saturation channels are more relatively independent in terms of their color properties, facilitating more effective color manipulation. Although the HSV color space differs biologically from the way that human visual system processes color, it provides a more intuitive framework for color adjustment, enhancing the perceptual recognition of color variations. This is particularly advantageous in VIF tasks, where decomposing color information into saturation and hue enables more targeted and precise processing of the source image. Consequently, this paper employs the HSV color space for image fusion.

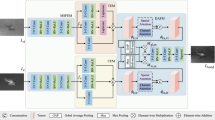

The overall process of PHFuse is illustrated in Fig. 2. Firstly, the visible image \(I_{vis}\) and the infrared image \(I_{ir}\) are converted from RGB to HSV format to obtain the HSV channels of the visible and infrared images, respectively. For the infrared image, we first copy and extend it from a grayscale image to an RGB image, denoted as \(I_R, I_G, I_B=I_{grey}\) , to obtain the RGB format of the infrared image. Then, the hue channel of the visible image \(I^H_{vis}\) is directly used as the fused image’s hue channel \(I^H_{F}\). The visible image and the infrared image are concatenated across all channels to form a 6-channel input block as the input for network branches. PHFuse has two fusion branches: branch_S and branch_V, which have the same structure and input. Branch_S and branch_V calculate the input and generate the saturation channel \(I^S_{F}\) and brightness channel \(I^V_{F}\) of the fused image in HSV color space, respectively. This HSV image is then converted to the RGB color space and obtain the fused image \(I_{F}\) in RGB format.

Unlike methods that only fuse the brightness channel, PHFuse retains the hue channel of the visible image while fusing saturation and value channels. Since black-and-white infrared images don’t contain any hue information, the hue information of the fused image is entirely inherited from the visible image.

For saturation and brightness channels, merely increasing the pixel brightness while keeping the saturation constant might cause the enhanced pixels contain too much white light and descent color vividness. Figure 3 illustrates the color distribution in the HSV color space where \(\hbox {H}=180^{\circ }\). Suppose we have a color with a saturation of 0.2 and value of 0.2, located at point (0.2, 0.2). After image fusion, if the saturation remains unchanged but the value is increased to around 0.9, the color will move to point (0.2, 0.9). Clearly, colors near point (0.2, 0.9) in Fig. 3 appear relatively gray. In the fused image, this results in the parts enhanced by the infrared image appearing gray and less colorfully rich. If we can maintain a value of 0.9 while increasing the saturation to 0.5 or higher, the point will move to a region with more vibrant color. This approach will better preserves color information while fusing and enhancing the image.

Therefore, to obtain a fused image with richer colors, it is necessary to adjust the saturation along with the brightness, which involves increasing or decreasing the target’s saturation based on the actual situation. In the following chapter, we demonstrate that PHFuse can achieve this goal through constraints and training.

Branch structure of PHFuse

PHFuse uses branch_S and branch_V to obtain the fused result for saturation and brightness. The network structures of these two branches are identical, both employing an Encoder-Decoder network, as shown in Fig. 4(a).

The encoder consists of a DenseNet containing five Dense Blocks, as shown in Fig. 4(b). Each Dense Block consists of a 3\(\times\)3 convolutional layer, a Batch Normalization layer, the activation function LeakyReLU, and a Triplet Attention Block, as depicted in Fig. 4(c). The output of each Dense Block has 24 channels, resulting in a total of 120 channels from the five Dense Blocks. Combined with the 4 input channels, the total number of output channels of the encoder is 124. The Triplet Attention Block is attached to the output of each Dense Block in order to more efficiently extract nonlinear features and enhance the stability of network training.

The decoder is composed of an attention module and 4 convolutional layers, as illustrated in Fig. 4(d). The attention module is added at the beginning of the decoder to perform attention-based selection of the features extracted by the encoder, thereby improving the performance of subsequent convolutions. The kernel size, activation function, and output channels for the four convolutional layers are annotated in Fig. 4(d). The decoder produces a single-channel output image of size 1\(\times\)h\(\times\)w.

In branches, PHFuse does not design a specific network structure for fusion strategy, but based on the constraints and iterations of network training, the branches autonomously iterate and learn to fuse image through nonlinear operations. Therefore, compared with manually designed fusion layers, PHFuse can implicitly select a nonlinear fusion strategy with better performance.

Loss functions

To constrain the network’s unsupervised training and achieve efficient fusion of information, we design a two-step training process for PHFuse. The first step trains the network to fuse grayscale information, while the second step trains the network to learn the fusion of color information. The main purpose of this two step training approach is to reduce the discrepancy of the constraint functions in each step, thereby enhancing the stability of the training process.

For the first step of training, we design a grayscale loss function \(L_{gray}\) as follows,

the loss function \(L_{grad}\) consists of thwo parts: intensity loss function \(L_{int}\) , gradient loss function \(L_{grad}\). \(\beta _1\) is the weight value.

The intensity loss function \(L_{int}\) is as follows,

where \(L_{max}\) is the maximum intensity loss function, which is used to compute the difference between the most prominent intensity information from both the fused image and the source image. Its form is as follows:

where max(a, b) is the maximum value between a and b, h and w are the height and width of the image respectively, \(I_{\text {vis}}^{ij}\), \(I_{\text {ir}}^{ij}\) and \(I_F^{ij}\) are the pixel values of the grayscale visible, infrared and fused images at point (i, j) in each image, that is:

In addition, we incorporate a visible image loss function \(L_{vis}\) to compensate for the intensity loss. \(\gamma\) is the weight value used to balance the influence of the visible image loss function on the network training. Without this compensation, the intensity distribution of the fused image would deviate from subjective visual perception, especially under the condition of color information fusion discussed in this paper. Therefore, adding this loss function helps to mitigate the distortion caused by a single reference image on the fusion result. The form of \(L_{vis}\) is as follows:

the meanings of terms in this equation are the same as in equation (3).

The gradient loss function \(L_{grad}\) is as follows,

where \(\nabla \cdot\) is the gradient of the image at point (i, j).We use the Sobel operator to calculate image gradient on the grayscale image.

It is worth noting that both the intensity loss function and the gradient loss function are calculated and backpropagated on grayscale images, as illustrated in Figure2. The RGB to grayscale image conversion in this paper is done as follows:

For the fused image, PHFuse converts it from RGB to grayscale before calculating the intensity and gradient loss functions, as shown in Fig. 2. The reason for not directly calculating the loss function from the V channel of the HSV image, but instead calculating after performing two additional conversions, is that if the loss is calculated directly from the V channel, the optimized weights can’t be backpropagated to branch_S. This would prevent the network from accurately reflecting the desired results, thereby reducing the quality of training. The saturation channel also affects the intensity and gradient results of the fused image, so it is necessary to calculate the loss functions on the grayscale image which allows the intensity and gradient losses to update the weights of branch_S.

In the second step of training, we introduce a color loss function. The form of the loss function at this stage is as follows:

where \(L_{color}\) is the color loss function, which is used to constrain the fusion of color information in the network. We add the loss function \(L_{1}\) in the second step of training to prevent the degradation of already trained parameters. \(\alpha\) is the weight value, which is used to balance the contribution of \(L_{1}\) during the second step of training.

The color loss function \(L_{color}\) is as follows:

where \(L_{sam}\) is the spectral angle mapping loss function, \(L_{S\_SSIM}\) is the saturation structural similarity loss function.

The spectral angle mapping40 can measure the vector direction similarity of pixels between two RGB images. Similar vector directions of pixels at the same position mean that the two pixels have similar colors. To provide reasonable unsupervised constraints during the training process and preserve color information in the fused image, we are inspired by the spectral angle mapping and introduce the spectral angle mapping loss function \(L_{sam}\) in the following form:

where \(\langle \vec {a}, \vec {b} \rangle\) is the angle between two vectors \(\vec {a}\) and \(\vec {b}\) , \(\vec {I}_F^{ij}\) and \(\vec {I}_{vis}^{ij}\) are the vectors composed of the R, G, and B channel pixel values of the fusion image of RGB and the visible image at pixel (i, j) , that is,

Therefore \(L_{sam}\) can also be written as the following form,

To ensure that the saturation of the fused image closely matches that of the visible image, we incorporate a saturation structural similarity loss function \(L_{S\_SSIM}\) into the loss function. Its form is as follows:

where \(\mu _{vis}^{S\_ij}\) and \(\mu _{F}^{S\_ij}\) represent the mean values in the saturation channels of the visible image and the fused image, respectively, near point (i, j). Similarly, \(sigma_{vis}^{S\_ij}\) and \(sigma_{F}^{S\_ij}\) represent the standard deviations, and \(sigma_{vis,F}^{S\_ij}\) represents the covariance. We use an 11\(\times\)11 window to calculate the mean, variance, and covariance around each pixel points. \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) are constants used to provide stability against small denominators41.

Experiments and results

Dataset selection and parameter settings

In network training, the LLVIP dataset 42 is used for network training. LLVIP dataset consists of registered pairs of visible and infrared images, with each image having a resolution of 1280\(\times\)1024 pixels. In LLVIP, the visible images are RGB color images, and the infrared images are grayscale images expanded into three RGB channels, visually appearing as grayscale images. All 12,025 pairs of visible-infrared images from the training set of LLVIP are used for training. Due to the large image size, we resized them to a resolution of 640\(\times\)512 for training. For the relevant parameters of loss functions, set \(\alpha =0.1\), \(\beta _1=0.2\), \(\beta _2=0.2\), \(\gamma =0.5\). For the relevant parameters of the training process, we set batch size=3, epoch=25, and learning rate=\(10^{-4}\).

For testing, since the LLVIP test set is large and contains duplicate images, we selected 200 pairs of images from the LLVIP test set as testing images. These images have various scenes, including both daytime and nighttime scenarios, and contain a rich variety of color information to validate the effectiveness of the proposed method. These images are also well-registered in spatial position.

Fusion results comparison and analysis

We compare and evaluate the obtained fused images to validate the effectiveness of the proposed PHFuse. We selected seven fusion algorithms for comparison with our method, including IFCNN25, DSFusion43, DATFuse44, TarDAL26, SemLA45and DIVFusion29. These algorithms based on deep learning methods and represent state-of-the-art techniques for visible and infrared image fusion. Regarding color processing, these methods handle color visible images in the YCbCr color space, separating image intensity from color and performing intensity information fusion. For the chrominance channels (CbCr), IFCNN use the color weighted fusion approach to obtain the CbCr channels of the fused image. Other methods directly copy the CbCr channels from the visible image as the CbCr channels of the fused image.

In image evaluation tasks, researchers typically evaluate images through a combination of qualitative and quantitative analyses to verify the effectiveness of the proposed methods46,47. We conduct qualitative analysis through subjective visual comparisons and quantitative analysis through objective metric evaluations. These assessments allow us to analyze and compare the fusion results of the PHFusion method and the aforementioned approaches from the perspectives of perceptual quality and mathematical measurement.

Qualitative comparison analysis

In terms of qualitative comparison, we selected three different scenes of daytime, bright night, and dark night from the LLVIP dataset for display, and zoomed in on specific regions to highlight the detailed fusion results.

Figure 5 shows the fusion results of the selected methods in the daytime scene with sufficient lighting scene. In this scene, the visible image displays objects and people on the street, containing rich intensity, texture, and color information, while the infrared image highlights thermal targets such as people, cars in sunlight, and running equipment cabinets. We have zoomed in on specific regions of the image to show the details, indicated by the red boxed areas. As observed, the green leaves on the left side of the red box maintain a similar level of color vividness to the visible image in DATFuse, TarDAL, SemLA, DSFusion and PHFuse, while DIVFusion fails to preserve the clear edges of the target. IFCNN is influenced by the infrared image, causing the leaf color to appear dark and grayish. On the right side of the zoomed-in region, there is a person riding a bicycle under the shade. In the visible image, this target appears darker, while the infrared image highlights it. It can be seen that in the fusion results, PHFuse not only maintains the brightness of the target but also enhances the color richness, making the target’s colors more vivid and improving the differentiation of image information.

Figure 6 shows the fusion results of the selected methods in the bright night scene. This scene depicts vehicles and pedestrians at an intersection, with the visible image providing most of the target information in the scene, while the infrared image highlights the person in image’s lower-left corner. In the fusion results of Fig. 6, all seven methods enhance the person, making it more prominent compared to the visible image. Additionally, observing the vehicle at the bottom of the frame, it appears light-colored in the visible image, but the fusion results of IFCNN, DSFusion, and SemLA show the vehicle in a grayish color. The other methods preserve the light color of the vehicle well. The red box shows a zoomed-in region of the sidewalk. It can be seen that the fusion results of DATFuse and TarDAL lose some edge information, while the other methods preserve the edges. These results demonstrate that in bright night scene, PHFuse can effectively fuse color information while also maintaining complementary details such as contours and textures. Its fusion results subjectively match or outperform the selected comparison methods.

Figure 7 shows the fusion results of the selected methods in the low-light night scene. In source images, the infrared image effectively highlights targets that are almost invisible in the visible image, such as people and trash cans on the street, indicating that the multi-modal source images contain a large amount of complementary information in this scene. In this context, most of the scene’s contours and texture information are contained in the infrared image, with a small portion present in the visible image. In the fusion results above, all seven methods manage to fuse the contour and texture information well, with the shapes of the street, vehicles, and the edges of the people and trash cans clearly visible, significantly improving the image quality compared to the visible image. Among these methods, only PHFuse provides rich color information after fusion, while the results of the other six methods are close to grayscale. Specifically, for the person in the red box, PHFuse preserves the red and blue colors of the clothing, while the other methods perform poorly in terms of color fidelity, which does not align with subjective visual perception. This indicates that existing fusion methods fail to effectively utilize the color information in the visible image, either not expressing it or expressing it weakly, resulting in a loss of fused information. This result shows that PHFuse is better at inheriting and expressing color information in low-light night scenes, offering a greater advantage in color fusion.

The results of the qualitative comparative analysis show that compared to the selected methods, the proposed method in this paper better preserves the color information from the visible light image, while also retaining the rich complementary brightness information and texture details from the two source images. Particularly in low light scenes, the fusion results that preserve hue channel enhance the vividness of the colors in the boosted areas, making the fusion outcome more aligned with human subjective visual perception.

Quantitative comparison analysis

In terms of quantitative comparative analysis, we selected five evaluation metrics to assess the fusion results: Entropy (EN)48, Average Gradient (AG)49, Visual Information Fidelity for Fusion (VIFF)50, Natural Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE)51, Blind Multiple Pseudo Reference Images measure (BMPRI)52 and Spectral Angle Mapping (SAM)40. EN evaluates the amount of information contained in the fused image, AG evaluates the richness of edge information in the fused image, and VIFF evaluates the information fidelity between the fused image and the source images. NIQE measures the naturalness of the image, where a smaller value indicates a more natural image, with less distortion introduced by fusion and a more reasonable color distribution. BMPRI evaluates the similarity between an image and its distorted reference image from four aspects: blocking, ringing, blurring, and noise artifacts. A lower BMPRI value indicates lower similarity to the distorted reference image and therefore a lower degree of image distortion. SAM evaluates the angular difference between the RGB vectors of corresponding pixels in the fused image and the visible image, where a smaller angle indicates greater color similarity between the two images. To make the presentation more intuitive, the SAM values are measured in degrees. Among these evaluation metrics, NIQE, BMPRI and SAM take color information into consideration during their evaluations. The performance of these three metrics provides insight into the effectiveness of the fusion method in handling color information.

The results of the quantitative comparative analysis are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 8. Table 1 presents the average values of the six evaluation metrics for the selected methods on the test set used in this paper. Figure 8 displays the cumulative probability distribution of the five evaluation metrics for PHFuse and the six selected methods. It can be observed that the proposed method achieves the best or second-best evaluation results in five of the six metrics, with a fourth-place ranking in the EN metric. The EN, AG, and VIFF evaluation metrics indicate that PHFuse, compared to the other methods, can effectively fuse the overall information of the image while preserving rich texture features. Furthermore, in the evaluation metrics related to color performance, PHFuse performs excellently in the NIQE, BMPRI and SAM metrics. In particular, in the SAM metric, PHFuse exhibits a smaller spectral angle, indicating a higher degree of color alignment in the fused image, which significantly outperforms the other methods. These three evaluation metrics show that PHFuse is far superior to the selected fusion methods in terms of color preservation.

The quantitative evaluation results above indicate that PHFuse retains a substantial amount of intensity gradient information from the source images and effectively aligns the image colors, which is also consistent with the results of the qualitative comparative analysis.

Generalization study

To verify the generalization performance of PHFuse, we selects 80 image pairs from the MSRS dataset53 and the aligned FLIR dataset23 for testing, respectively. Since MSRS and FLIR were not used as training sets for PHFuse, images from the test sets of these two datasets are chosen for evaluation to validate the method’s generalizability.

MSRS dataset

We perform qualitative and quantitative comparative analyses on fusion results based on the MSRS dataset. The following are the detailed results.

In the scene shown in Figure 9, despite it being daytime, the weak illumination makes it difficult to distinguish the person under the tree from the background in the visible image. However, the infrared image clearly highlights the person as a thermal target. For the background part in the fusion results, IFCNN, DSFusion, and SemLA are influenced by the infrared image, causing the overall brightness of the scene to be lower than that of the visible image, which degrades the quality of the fusion. When focusing on the tree trunk and leaves in the center of the scene, the edges of these background elements appear blurred in the fusion results of TarDAL and DIVFusion, while the other methods preserve clearer edge information. For the fused pedestrian targets, all methods are able to inherit the intensity information from the infrared image, for all seven methods highlight the two pedestrians in the fused image, which is shown in the red box with a zoomed-in view. Additionally, PHFuse stands out in terms of color preservation, making the pedestrian’s clothing more vibrant, with the red shirt and dark blue pants easily distinguishable. These observations confirm PHFuse’s ability to effectively fuse complementary information in low-light environments, as well as its superior performance in retaining color information.

Figure 10 shows the low-light night scene from the MSRS dataset. In this scene, the truck on the left is illuminated by the headlights of the vehicle behind it, and its overall outline is clearer compared to other targets. The person in the green box blends with the dark background in the visible image, making it difficult to distinguish, but the infrared image clearly reveals this target. In this scene, when performing image fusion, we expect the fused image to not only highlight the complementary information from the two modalities but also preserve rich texture features and color details. From the fusion results, it can be seen that all methods preserve the complementary information of the original images. However, in terms of detail, for example, the yellow and blue logos on the truck within the red box, the fusion results of IFCNN and DSFusion are darker, which blurs the texture details of these logos. Additionally, the excessive enhancement of image brightness by DIVFusion makes the logos blend more with the background, reducing the clarity of the image details. The remaining methods are able to express the truck logos effectively in the fusion results. For the pedestrian in the green box, replacedall the methods clearly highlight the target, achieving successful fusion of complementary information. This observation indicates that PHFuse, like the best-performing methods, can fuse complementary information while preserving the visible image’s brightness, texture, and color details.

We also conducted a quantitative comparative analysis of the results on the MSRS dataset. The analysis used the same evaluation metrics as in the previous section, with the average values and cumulative distribution results shown in Table 2 and Fig. 11, respectively. It can be observed that PHFuse ranks second in the EN, AG, and VIFF metrics, only trailing behind the DIVFusion method. This indicates that, for the MSRS dataset, DIVFusion generally captures more fusion information, while PHFuse outperforms the other five methods. Additionally, in the NIQE, BMPRI and SAM evaluation metrics, PHFuse demonstrates a significant lead, with values significantly lower than those of the six selected fusion methods. These results confirm PHFuse’s superior ability to preserve color information, making better use of the color information in the visible image and reducing color distortion in the fused image on the MSRS dataset.

FLIR dataset

As in the previous section, we conduct both qualitative and quantitative comparative analyses of the fusion results based on the FLIR dataset.

Figure 12 shows the scene of a nighttime intersection from the FLIR test set. The lighting conditions in this scene are adequate, with most of the contour and texture information concentrated in the visible image. At the same time, the pedestrian across the road blends into the background and is difficult to distinguish, complementing the pedestrian target in the infrared image. In the fusion results, it can be observed that, except for IFCNN, the remaining six methods are able to preserve most of the intensity, edge, and color information from the visible image, whereas the fusion result of IFCNN is darker, causing noticeable color distortion. The red box highlights the fusion of the pedestrian in the infrared image, reflecting how the fusion methods handle complementary information. It can be seen that DIVFusion produces a blurred edge around the person, while all other methods effectively highlight this target. Additionally, it is evident that, except for IFCNN, the methods in this dataset perform better at retaining color information. Besides, PHFuse preserves the most vibrant and rich colors in the fusion image.

Table 3 and Fig. 13 present the results of the quantitative comparative analysis of the fusion images on the FLIR dataset. PHFuse ranked in the middle in the EN , VIFF NIQE and BMPRI metrics but achieves the best or second-best evaluation results in AGdeleted, VIFF, and SAM. The EN results indicate that, for this dataset, PHFuse’s ability to fuse overall information is not as strong as that of other methods. At the same time, the relatively high AG value suggests that the gradient information in the fused image is prominent. While this highlights edge information, it also introduces some negative effects, such as making the image appear less natural, thus lowering the NIQE and BMPRI score. However, despite improvements in SAM values for the other methods, PHFuse still performs best in the SAM metric. Therefore, for the FLIR dataset, the strong response to edge information in PHFuse leads to some information distortion, but it still preserves the best color information.

The fusion results on both the MSRS and FLIR datasets show that PHFuse performs similarly to existing methods in terms of fusing intensity and texture information, while excelling in color information processing. This is consistent with the results from the LLVIP dataset, where PHFuse was trained, demonstrating its good generalization ability.

Ablation study

Ablation of loss functions

In the training process of PHFuse, we introduced the saturation structural similarity loss function and spectral angle mapping loss function to enable the fusion network to better calculate color information. This section verifies the effectiveness of these loss functions through ablation experiments.

a) Saturation structural similarity loss function

To verify the effectiveness of the introduced saturation structural similarity loss function, we removed the saturation structural similarity loss function from PHFuse and created a new comparative model, P_woSSSIM, for training and testing.

Figure 14(d) shows the qualitative comparison results of this model. It can be observed that the overall image is quite similar to PHFuse, but the color of the person in the magnified red box is slightly less vivid than in PHFuse. The quantitative analysis in Table 4 also demonstrates that all metrics for P_woSSSIM are inferior to PHFuse. From the above analysis, it can be concluded that, although the improvement is modest, the saturation structure similarity loss function enhances the overall quality of the fusion results and improves the representation of image information.

b) Spectral angle mapping loss function

Similarly, we removed the spectral angle mapping loss function from PHFuse to form a new comparison model, P_woSAM, for training and testing to verify the effectiveness of the spectral angle mapping loss function.

The qualitative and quantitative comparisons of the fusion results for this model are shown in Fig. 14(e) and Table 4, respectively. Clearly, after removing the spectral angle mapping loss function, the colors of both the target and background in Figure 14 become more muted, and the color richness of the fusion results is significantly reduced. In Table 4, the performance of AG, VIFF, NIQE and BMPRI improves, while the SAM metric value increases sharply. This indicates that during training, the network shifts weight updates more towards non-color information, such as intensity and gradient, resulting in a significant decline in color information in the fusion results. This analysis demonstrates that the spectral angle mapping loss function plays a critical role in preserving color information and effectively enhances the color alignment between the fused image and the visible light image.

Ablation of input channels

Regarding the network input, we concatenated all HSV channels of visible and infrared images into six channels as the input for each branch. To verify the effectiveness of this input configuration, we designed P_in4 and P_in2 ablation models with two different inputs for testing.

a) 4-Channel input

In this setting, the saturation and brightness channels of the visible and infrared images are concatenated into four channels, forming the input for each branch, creating the P_in4 model. The rest of the network structure and parameter settings remained unchanged. The results of training and testing are shown in Figure 14(f) and Table 4.

In Figure 14(f), although the fused image retains most of the contours and edges, its color vibrancy is significantly reduced compared to PHFuse, highlighting its deficiency in integrating color information. Table 4 shows that while P_in4 exhibits improvements in AG, NIQE and BMPRI, it shows declines in EN, VIFF, and SAM metrics. The large increase in the SAM value indicates insufficient color information in the fused image after removing hue inputs. Additionally, the changes in other metrics suggest that removing hue inputs does not enhance the network’s performance in fusing intensity and gradient information. This demonstrates that although hue is not directly computed by the fusion network, it serves as an important reference in color information fusing procedure.

b) 2-Channel input

For this setting, the saturation channels of the visible and infrared images are concatenated into two channels as input for the saturation branch, and the brightness channels are similarly concatenated for the brightness branch, forming the P_in2 model. The training and testing results of this model are presented in Figure 14(g) and Table 4.

As shown in Figure 14(g), the P_in2 results exhibit weaker color preservation compared to PHFuse, such as the muted red color of the person in the red box. Table 4 also reveals that, apart from a slight improvement in the BMPRI score, P_in2 underperforms PHFuse across all metrics. Particularly, the SAM value for P_in2 not only lags far behind PHFuse but is also inferior to P_in4, indicating further degradation in the color information of the fused image. This suggests that when fusing saturation and brightness, the results are influenced not only by hue but also by the interdependence of saturation and brightness, where the fusion of brightness is related to saturation, and vice versa.

The ablation experiments on network input demonstrate that the color information of an image is closely related to all source image components, including hue, saturation, and brightness. When computing contrast information during fusion, it is essential to incorporate not only the contrast data from the source images but also hue and intensity information. Similarly, intensity computation follows this pattern. Therefore, the input configuration used in this study is rational and effective.

Conclusions

In the visible and infrared image fusion task, color information is a crucial component of visible images. However, most of the existing methods focus on the fusion of single-channel grayscale information and do not specifically handle color information. Therefore, this paper proposes a novel fusion network PHFuse, which has a new designed dual-branch structure to compute the fusion of saturation and luminance. The design of network structure and are combined with new loss function to impose constraints on color information, enabling unsupervised training for color VIF image fusion. Additionally, we introduce new evaluation metrics, NIQE and SAM, to assess color information in the fusion results of visible and infrared images. Experimental results on public datasets show that the proposed fusion network preserves color information better than existing fusion methods, making the fused images more consistent with human subjective perception while retaining rich contour and texture information.

Although PHFuse can significantly improves color fusion, its loss functions are relatively simple. Especially for the processing of brightness information, directly using intensity and gradient loss functions may not handle texture details delicately in some special scenarios. Moreover, constraining grayscale and color information simultaneously can occasionally cause gradient vanishing problem during training, requiring a reduced learning rate or other strategies to mitigate this effect. In this regard, more advanced loss functions could be considered to solve the problem of relatively poor texture detail representation. Furthermore, Visual attention mechanisms can guide the fusion process to focus on important regions in visible and infrared images, improving the preservation of key details and semantic information. Integrating such attention-based models into VIF tasks is a promising direction that could enhance fusion performance, especially in challenging scenes. Future research could explore the deeper integration of self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms with color feature learning. Such exploration may help enhance network performance while reducing computational resource requirements.

Data availability

The data of this article will be made available by the corresponding author on request(kuanghp@163.com).

References

Chen, Y., Wang, Z.-M. & Bao, H. Multi-phase fusion of visible-infrared information for motion detection. In Multimedia and Signal Processing: Second International Conference, CMSP 2012, Shanghai, China, December 7-9, 2012. Proceedings, 325–333 (Springer, 2012).

Li, M. et al. Multisensor image fusion for automated detection of defects in printed circuit boards. IEEE Sensors Journal 21, 23390–23399 (2021).

Zhang, X., Ye, P., Leung, H., Gong, K. & Xiao, G. Object fusion tracking based on visible and infrared images: A comprehensive review. Information Fusion 63, 166–187 (2020).

Li, J., Peng, Y. & Jiang, T. Embedded real-time infrared and visible image fusion for uav surveillance. Journal of Real-Time Image Processing 18, 2331–2345 (2021).

Nercessian, S., Panetta, K. & Agaian, S. Human visual system-based image fusion for surveillance applications. In 2011 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 2687–2691 (IEEE, 2011).

He, G., Ji, J., Dong, D., Wang, J. & Fan, J. Infrared and visible image fusion method by using hybrid representation learning. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 16, 1796–1800 (2019).

Gu, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, C. & Li, B. Advanced driving assistance based on the fusion of infrared and visible images. Entropy 23, 239 (2021).

Burt, P. J. & Adelson, E. H. A multiresolution spline with application to image mosaics. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 2, 217–236 (1983).

Guo, K. & Labate, D. Optimally sparse multidimensional representation using shearlets. SIAM journal on mathematical analysis 39, 298–318 (2007).

Yang, B. & Li, S. Multifocus image fusion and restoration with sparse representation. IEEE transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 59, 884–892 (2009).

Li, X., Tan, H., Zhou, F., Wang, G. & Li, X. Infrared and visible image fusion based on domain transform filtering and sparse representation. Infrared Physics & Technology 131, 104701 (2023).

Meng, F., Guo, B., Song, M. & Zhang, X. Image fusion with saliency map and interest points. Neurocomputing 177, 1–8 (2016).

Chen, J., Wu, K., Cheng, Z. & Luo, L. A saliency-based multiscale approach for infrared and visible image fusion. Signal Processing 182, 107936 (2021).

Zhang, X. & Demiris, Y. Visible and infrared image fusion using deep learning. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 45, 10535–10554 (2023).

Ding, Z., Zhou, D., Nie, R., Hou, R. & Liu, Y. Infrared and visible image fusion using modified pcnn and visual saliency detection. In 2018 International Conference on Image and Video Processing, and Artificial Intelligence, vol. 10836, 66–72 (SPIE, 2018).

Lu, R., Gao, F., Yang, X., Fan, J. & Li, D. A novel infrared and visible image fusion method based on multi-level saliency integration. The Visual Computer 39, 2321–2335 (2023).

Li, H. & Wu, X.-J. Densefuse: A fusion approach to infrared and visible images. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 28, 2614–2623 (2018).

Ma, J., Yu, W., Liang, P., Li, C. & Jiang, J. Fusiongan: A generative adversarial network for infrared and visible image fusion. Information fusion 48, 11–26 (2019).

Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Wang, J., Xi, X., Li, D. & Li, F. Fusiongram: An infrared and visible image fusion framework based on gradient residual and attention mechanism. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 72, 1–12 (2023).

Li, H. & Wu, X.-J. Crossfuse: A novel cross attention mechanism based infrared and visible image fusion approach. Information Fusion 103, 102147 (2024).

Toet, A. The tno multiband image data collection. Data in brief 15, 249 (2017).

Zhang, H., Fromont, E., Lefevre, S. & Avignon, B. Multispectral fusion for object detection with cyclic fuse-and-refine blocks. In 2020 IEEE International conference on image processing (ICIP), 276–280 (IEEE, 2020).

Hwang, S., Park, J., Kim, N., Choi, Y. & So Kweon, I. Multispectral pedestrian detection: Benchmark dataset and baseline. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 1037–1045 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ifcnn: A general image fusion framework based on convolutional neural network. Information Fusion 54, 99–118 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Target-aware dual adversarial learning and a multi-scenario multi-modality benchmark to fuse infrared and visible for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 5802–5811 (2022).

Union, I. T. Recommendation itu-r bt.601-7: Studio encoding parameters of digital television for standard 4:3 and wide-screen 16:9 aspect ratios. Tech. Rep. BT.601-7, International Telecommunication Union, Geneva, Switzerland (2011).

Xu, H., Ma, J., Jiang, J., Guo, X. & Ling, H. U2fusion: A unified unsupervised image fusion network. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 44, 502–518 (2020).

Tang, L., Xiang, X., Zhang, H., Gong, M. & Ma, J. Divfusion: Darkness-free infrared and visible image fusion. Information Fusion 91, 477–493 (2023).

Herrera-Arellano, M., Peregrina-Barreto, H. & Terol-Villalobos, I. Visible-nir image fusion based on top-hat transform. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 30, 4962–4972 (2021).

Misra, I., Rohil, M. K., Moorthi, S. M. & Dhar, D. Clim: Co-occurrence with laplacian intensity modulation and enhanced color space transform for infrared-visible image fusion. Infrared Physics & Technology 135, 104951 (2023).

Manchanda, M. & Sharma, R. Fusion of visible and infrared images in hsv color space. In 2017 3rd International Conference on Computational Intelligence & Communication Technology (CICT), 1–6 (IEEE, 2017).

Tsagaris, V. & Anastassopoulos, V. Fusion of visible and infrared imagery for night color vision. Displays 26, 191–196 (2005).

Ding, Z., Li, H., Zhou, D., Liu, Y. & Hou, R. A robust infrared and visible image fusion framework via multi-receptive-field attention and color visual perception. Applied Intelligence 53, 8114–8132 (2023).

Smith, A. R. Color gamut transform pairs. ACM Siggraph Computer Graphics 12, 12–19 (1978).

Guo, M.-H. et al. Attention mechanisms in computer vision: A survey. Computational visual media 8, 331–368 (2022).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 7132–7141 (2018).

Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J.-Y. & Kweon, I. S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 3–19 (2018).

Misra, D., Nalamada, T., Arasanipalai, A. U. & Hou, Q. Rotate to attend: Convolutional triplet attention module. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision, 3139–3148 (2021).

Kruse, F. A. et al. The spectral image processing system (sips)-interactive visualization and analysis of imaging spectrometer data. Remote sensing of environment 44, 145–163 (1993).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE transactions on image processing 13, 600–612 (2004).

Jia, X., Zhu, C., Li, M., Tang, W. & Zhou, W. Llvip: A visible-infrared paired dataset for low-light vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 3496–3504 (2021).

Liu, K. et al. Dsfusion: infrared and visible image fusion method combining detail and scene information. Pattern Recognition 154, 110633 (2024).

Tang, W., He, F., Liu, Y., Duan, Y. & Si, T. Datfuse: Infrared and visible image fusion via dual attention transformer. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 33, 3159–3172 (2023).

Xie, H. et al. Semantics lead all: Towards unified image registration and fusion from a semantic perspective. Information Fusion 98, 101835 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Infrared and visible image fusion: From data compatibility to task adaption. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (2024).

Min, X., Duan, H., Sun, W., Zhu, Y. & Zhai, G. Perceptual video quality assessment: A survey. Science China Information Sciences 67, 211301 (2024).

Roberts, J. W., Van Aardt, J. A. & Ahmed, F. B. Assessment of image fusion procedures using entropy, image quality, and multispectral classification. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing 2, 023522 (2008).

Dong, L., Yang, Q., Wu, H., Xiao, H. & Xu, M. High quality multi-spectral and panchromatic image fusion technologies based on curvelet transform. Neurocomputing 159, 268–274 (2015).

Han, Y., Cai, Y., Cao, Y. & Xu, X. A new image fusion performance metric based on visual information fidelity. Information fusion 14, 127–135 (2013).

Mittal, A., Soundararajan, R. & Bovik, A. C. Making a “completely blind’’ image quality analyzer. IEEE Signal processing letters 20, 209–212 (2012).

Min, X., Zhai, G., Gu, K., Liu, Y. & Yang, X. Blind image quality estimation via distortion aggravation. IEEE Transactions on Broadcasting 64, 508–517 (2018).

Tang, L., Yuan, J., Zhang, H., Jiang, X. & Ma, J. Piafusion: A progressive infrared and visible image fusion network based on illumination aware. Information Fusion 83, 79–92 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Department of Science and Technology of Jilin Province (No.Y4U011302701).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z.; methodology, C.Z., H.W. and C.W.; hardware and software, C.Z., H.K., G.Y. and C.W.; experiments and evaluation, C.Z.; writing C.Z.; Revising and editing, H.K., H.W. and C.L.; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuang, C., Kuang, H., Wang, H. et al. PHFuse: Unsupervised color visible and infrared image fusion with preserved hue. Sci Rep 15, 31458 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15158-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15158-7