Abstract

Ophrys apifera, commonly known as the bee orchid, is a species of orchid that has expanded its range northwards in recent decades. The present study focuses on its occurrence in Poland and analyses possible causes of this expansion, including climate change, autogamy and genetic diversity of new populations. Genetic analyses using nuclear microsatellite markers and plastid DNA revealed low overall population variability in Poland and neighbouring countries (the Czech Republic, Germany), probably caused by the founder effect and bottleneck, as well as the autogamous reproductive strategy of this species. STRUCTURE analysis identified three genetic clusters, with western populations forming a distinct, homogeneous cluster, while southern populations show a greater degree of genetic mixing. Plastid haplotype diversity was limited, with most populations dominated by a single haplotype. This confirms the scenario of recent colonisation through long-distance seed dispersal. Ecological niche modelling indicates that although O. apifera will continue to spread in regions with a suitable climate in northern and central Europe, habitat loss due to rising temperatures is predicted in the southern and western parts of its range. The combination of genetic and ecological data suggests that several independent colonisation events contributed to the recent spread of O. apifera. These findings highlight the importance of monitoring genetic variation in newly established populations and further investigating the role of climate change in the range shift of orchids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate is a main factor shaping species distributions, and the global changes in temperature and precipitation currently observed are causing shifts in the geographical range of many organisms1. In general, the direction of these changes is polar or upward2. Various estimates of potential climate change have been presented in the form of global climate models (GCMs), which are complex mathematical representations of the main elements of the climate system (atmosphere, land surface, ocean and sea ice) and their interactions3. These projections are now widely used by biologists to estimate changes in the range of rare or endangered organisms4,5, as well as to manage the expansion of invasive species6,7.

Although orchids are generally considered to have low invasive potential due to their complex relationships with specific pollen vectors8 and their dependence on mycorrhizal fungi during seed germination9, there are species that are able to adapt to global warming and spread to new, climatically suitable areas. Global warming allows thermophilic species to expand their range into previously inaccessible regions. One such species is Ophrys apifera Huds., commonly known as the bee orchid, which has recently been recorded for the first time in several geographical areas outside its natural range.

Ophrys apifera is a species native to the Mediterranean region of Europe. Its range extends across southern and western Europe, North Africa and the Middle East10,11,12,13. In recent decades, the species appears to be expanding its range further north, particularly in Central Europe. For example, it has recently been discovered for the first time in Poland14,15, Denmark16 and Germany17. On the other hand, some of these new locations are reportedly of artificial origin, resulting from deliberate planting (e.g. near Brandenburg in Germany17,18,19) or accidental introduction of seeds (e.g. in Sweden16).

The bee orchid, like other species of the genus Ophrys, is well known for its unique flower, which mimics the appearance of a female bee to attract males for pollination (this type of pollination strategy is known as sexual deception). The orchid mimics a female insect by secreting pheromones to attract long-horned bees (Eucera spp. and Tetralonia lucasi, Apidae)20,21,22. Interestingly, the bee orchid is capable of spontaneous self-pollination in many regions, and the structure of its flowers facilitates this process23,24,25,26. At the northern limits of its range, the flowers of this species appear to be almost exclusively self-pollinating27,28. The ability of the bee orchid to autogamy seems to be a key adaptation that has enabled its expansion, providing the plant with the opportunity to reproduce in the absence of pollinators13.

Ophrys apifera occurs in various habitats, including meadows, pastures and open forests on calcareous or calcareous-clay soils. It prefers well-drained soils and often grows in sunny or partially shaded locations. It also occurs in disturbed and anthropogenic areas where competition from other plants is limited29,30,31. In addition, this species has been identified as a pioneer species that colonises bare soils during succession32. The bee orchids appear to be long-lived, with successive generations in the population having an average ‘half-life’ (a measure of life expectancy) of 6.6 years, ranging from 5.8 to 11.2 years33. In addition, the plants need about 10 years to reach full maturity, produce their first flowers and finally produce seeds34.

In Poland, O. apifera was not recorded until the twenty-first century. The first specimens were discovered near a quarry in Imielin (Upper Silesia) in 201014. In 2020, a second population was found in the western Sudetes (Kaczawskie Mountains), and another site was identified in Upper Silesia. Further sites were recorded in the West Pomeranian, Silesian, Lubusz, Świętokrzyskie, and Lesser Poland voivodeships in 2024 (pers. comm.). It is estimated that there are currently about 10–15 localities of this species in Poland. The origin of the Polish population is unknown, and two hypotheses have been put forward to explain this phenomenon. The first assumes that these populations are anthropogenic and that the plants were deliberately introduced/planted by humans. The second assumes that the populations developed naturally as a result of wind dispersal of seeds. However, the discovery of new populations of bee orchids in various parts of Poland over the last year seems to contradict the first hypothesis. We assume that the populations of O. apifera in Poland are the result of colonisation from southern and/or western Europe, and their current genetic structure reflects both recent migration routes and responses to changing climatic conditions.

The aim of this study was to analyse the possible causes of the expansion of O. apifera in Eastern Europe. To achieve this goal, we combined different data sets (plastid DNA markers and nuclear microsatellites) with ecological niche modelling to assess the origin of bee orchid populations in Poland, potential migration routes, the level of genetic variability, and the impact of climate change on the occurrence of O. apifera populations.

Material and methods

Sampling

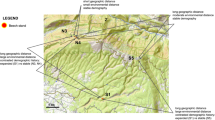

Plant material was collected from well-documented and publicly accessible populations in Poland, as well as from two populations in the Czech Republic and Germany, located near the Polish border. The selection of these neighbouring populations was based on our assumptions regarding the direction of migration from these source populations to Poland and their genetic similarity. The study included the following sites, with the number of populations studied in parentheses: Poland—POLI, POLD, POLP, POLM and POLK (5); Germany—GERF and GERB (2); and Czech Republic—CZS and CZVP (2) (Fig. 1). A total of 96 specimens were collected for molecular studies, and detailed information on the sampling sites and sample sizes is provided in Table S1. In addition, material from two herbarium sheets, i.e. UGDA.0009151 (Italy, Sicily) and UGDA.0018279 (Greece, Crete) from the Herbarium Universitatis Gedanensis UGDA, was used to examine microsatellite locus polymorphism and as a reference point and genetic background for further studies of genetic variation. The obtained DNA isolates were also deposited in the UGDA Herbarium (voucher numbers are given in Table S1).

Distribution map of surveyed populations of Ophrys apifera. The native range of this species is marked in green. The locations of the study populations are indicated by red dots. More detailed descriptions of the populations and their respective codes are provided in Table S1. Maps created in QGIS 3.34.12135 (https://qgis.org).

DNA isolation and plant identification

DNA was extracted from silica gel-dried leaf material using a modified version of the 2 × CTAB method35 for genotyping and using a DNA Mini Plant Kit (A&A Biotechnology, Poland) for plant identification.

The variability of the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2) region allows for the unambiguous identification of O. apifera among other species in the Ophrys genus36. The ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region was amplified using the primers 17SE and 26SE37. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications were performed in a total volume of 25 µl, containing 1 × buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.2 µM of each primer, 4% of DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide), 1.0 unit of Taq polymerase and DNA template (~ 30 ng). The thermal cycling protocol included an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 45 s of denaturation at 94 °C, 45 s of annealing at 59 °C, and 60 s of extension at 72 °C, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were purified using the High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Roche Diagnostic GmbH, Germany). Tubes containing purified PCR product (~ 80 ng) and 2.5 μM primer (the same one used for PCR amplification) were sent to Macrogen (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) for sequencing. Both DNA strands were sequenced to ensure accuracy in base calling. The sequences were edited using FinchTV v. 1.4.0 (Geospiza, Inc.), and the two complementary strands were assembled with AutoAssembler (ABI). The BLAST algorithm (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) was used to assess the similarity of the obtained sequences to the other sequences for O. apifera.

Genotyping

Initially, we examined seven microsatellite loci that had been for O. araneola36 and three markers specific for O. fusca38. Cross-species amplification ultimately identified six microsatellite loci useful for O. apifera variation studies (OFCA36, OFCA101, OaCT1, OaCT2, OaCT6, OaCT7; Table S2). PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 10 μL, comprising 0.25 μM primer for each locus, and DNA template (2 ng/μL) in 2 × Multiplex PCR Master Mix (Qiagen). Forward primers used for amplification were dye-labelled at the 5'-end (6-FAM, HEX, or TAMRA; Genomed S.A.), to facilitate the visualization of the amplified fragments. The following touchdown protocol for PCR amplification consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 9 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C with a reduction of 0.5 °C per cycle for 1 min 30 s (except for the OaCT6 locus, which was set at 58 °C) and 72 °C for 1 min. The subsequent 24 cycles used 94 °C for 30 s, an annealing of 55 °C, and 72 °C for 1 min. The last round was carried out at 72 °C for 10 min to finalize the reaction.

Four size-variable plastid DNA loci (from three plastid regions trnS-trnG, trnL-trnF, and rps16) were amplified for the presence of microsatellite motifs. Detailed descriptions of these markers are reported in Cotrim et al.39. The four loci (Trn1, Trn2, Trn4, Rps1; Table S2) were amalgamated into patterns of variation across all marker sites and classified as haplotypes. PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 10 μL containing: 1.25 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, bovine serum albumin (BSA) (0.25 ng μL−1), 0.1 μM primer for each locus, 0.25 units of DNA polymerase (Taq PCR Core Kit; Qiagen) and template DNA (1 ng μL−1) in 1 × reaction buffer. Forward primers employed for amplification were dye-labelled (6-FAM, HEX, or TAMRA; Genomed S.A.). A touchdown protocol was used for PCR amplification: the initial denaturation step (94 °C for 2 min) was followed by nine cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C (-0.5 °C per cycle) for 1 min, and 72 °C for 30 s. The next 24 cycles used 94 °C for 45 s, an annealing of 53 °C and 72 °C for 1 min. The final round utilized 72 °C for a duration of 7 min.

PCR products from each reaction were mixed with ROX-500 as a size standard to determine their exact size (in bp). All samples for the length-variable fragment analysis were processed using an ABI Prism 310 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies). The size of each fragment was determined using PeakScanner 2.0 (Applied Biosystems).

Genetic analyses

Nuclear microsatellite analysis

The following genetic diversity parameters were calculated: the average number of alleles per locus (A), the effective number of alleles (Ae), and the expected heterozygosity (He). Since sample sizes varied between populations, the measure of allele richness (RA) was additionally calculated using the rarity method. Fixation indices, FIS (the inbreeding coefficient) were estimated based on the estimators proposed by Weir & Cockerham (1984). The statistical significance of FIS was determined by a permutation test across loci for each population (P = 0.05). The above statistics were also calculated at the species level, without subdividing into populations to gain a more general understanding of the variability in O. apifera. In addition, the theoretical number of migrants [(Nm = (1–FST)/4FST)] entering each population in each generation was estimated based on the method proposed by Barton and Slatkin40. These parameters were calculated using the GENEPOP 4.041 and FSTAT 2.9.3.242 software.

To analyse the genetic structure of the population and assign individual genotypes to gene pools, without taking into account information about sampling locations, the Bayesian clustering method was used, implemented in the STRUCTURE 2.3.443 programme. The data were analysed using a mixed model, assuming uncorrelated allele frequencies, in accordance with the findings of Falush et al.44. The number of clusters (K) was assumed to range from 1 to 9. Ten runs were performed for each K, with a burn-in length of 500,000 steps and 750,000 iterations. The results were then summarised on the StructureSelector online platform45, which implements Evanno’s method to estimate the most probable K value for the data46. Pairwise-FST was used to assess the differentiation between all pairs of populations, with calculations conducted for each pair of populations, as well as the entire sample. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) and the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) were performed on the resulting genetic distance matrix to illustrate the pattern of genetic differentiation among all analysed populations, using the PAST 4.03 program47.

The BOTTLENECK 1.2.02 programme48 was used to test the recent reduction of effective population size, as alleles are generally lost faster than heterozygosity. Consequently, populations that have recently experienced a bottleneck will show an excess of heterozygosity relative to the expected based on the number of alleles found in the sample, assuming that the population was in mutation-drift equilibrium. The significance of differences between excess and deficient genetic diversity was examined using the Wilcoxon test (1,000 permutations), in which the bottleneck intensity was assessed by ΔHe = He – Heq. It is noteworthy that following a significant bottleneck, ΔHe > 0.

The presence of potential genotyping errors due to stuttering, large allele dropouts, and null alleles was investigated using MICROCHECKER 2.2.349.

Historical migration inference

To estimate the long-term gene flow between populations, we used the MIGRATE-n 3.7.2 software50,51, which applies a coalescence-based Bayesian inference framework to estimate effective population sizes scaled by mutation (Θ = 4Neμ) and mutation-scaled migration rates (M = m/μ), where Ne is the effective population size, μ is the mutation rate, and m is the migration rate. The effective number of migrants per generation (Nm) was calculated as Nm = (Θ × M)/4. In our analyses, we adopted the Brownian motion model for microsatellite evolution. Initial a priori distributions were selected after exploratory analyses to ensure coverage of the parameter space. Uniform a priori distributions were used for both Θ (min = 0, max = 100, and delta = 10) and M (min = 0, max = 1000, delta = 100), with initial values based on FST estimates. We performed 10 replicates of MIGRATE-n using a Markov chain Monte Carlo search with 10,000 burn-in steps, followed by 20,000 steps in a single long MCMC chain, recording samples every 100 steps. In the first stage, we decided to analyse a scenario in which each population was compared with every other population in pairs. Ultimately, we decided to analyse populations divided into three groups, according to the clusters obtained in the STRUCTURE analysis.

Plastid haplotypes analysis

Diversity parameters were calculated based on the frequency of haplotypes obtained: the number of haplotypes encountered (A), gene diversity indices (H)52 and the average gene diversity over loci (π)53,54. In addition, haplotype richness (RH), which describes gene diversity, was calculated regardless of sample size. The statistics mentioned were computed at the species level without population breakdown to understand the overall variation in O. apifera. The above calculations were calculated using Haplotype Analysis 1.0555. The relationships between plastid haplotypes were illustrated using a median-joining network56, wherein variants recognized at the four loci examined were regarded as ordered characters according to fragment size and number of repeats. The network was performed in NETWORK 10.2 (Fluxus Technology Ltd.), with all default settings. Furthermore, a second network was constructed, integrating the haplotypes acquired in this study and two haplotypes obtained from herbarium material for O. apifera (from Italy and Greece), with those taxonomically unambiguously assigned to O. lutea or O. fusca39. This was done to get a broader geographical context for the identified haplotypes and to determine their potential origin and/or resemblance. To our knowledge, these are the only haplotypes of Ophrys representatives available for comparison with our own, due to the use of the same plastid primers in both Cotrim et al.39 and the present study.

To summarize the patterns of differentiation among the multilocus haplotypes identified, the average number of differences between haplotypes for each pair of populations was calculated. The genetic diversity between the populations studied and the haplotypes was assessed using genetic distance, utilizing the pairwise-FST57. The resulting distance matrix was employed to illustrate phenetic relationships between populations using principal coordinates analysis (PCoA). Data analysis was conducted using Arlequin 3.558 and PAST 4.0347 software.

AMOVAs and geographic patterns

The hierarchical partitioning of genetic variance within and between populations was described using analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA). Separate analyses were performed for plastid and nuclear data. Significance values for populations were determined using a permutation test (10,000 permutations), with calculations executed in Arlequin 3.558. The isolation-by-distance (IBD) model, representing the correlation between estimates of genetic diversity based on nuclear microsatellites and plastid haplotypes and geographical distances (in km) for each pair of populations (see Table S3 and Table S4), was evaluated using the Mantel test. The significance of the test was determined using a permutation test, using Mantel 2.0 programme59.

Species distribution models

List of localities

Database of localities of O. apifera was compiled based on the Global Biodiversity Information Facility60, literature data12,14,61,62,63,64 and field works. Only records that could be georeferenced with the precision of 1 km were used in Ecological Niche Modelling (ENM) analyses and the duplicate presence records (records within the same grid cell) were removed using MaxEnt. To further reduce sampling bias the localities were rarified using five classes of topographic heterogeneity65. Species records were reduced using the minimum distance of 25 km in areas of low topographic heterogeneity and 5 km in highly heterogeneous areas. This spatial resolution was chosen to avoid disproportionate representation of certain areas, as species distribution models should generally be applied assuming that the study area is sampled randomly66. A complete list of localities used in this study is available as Table S5.

Ecological niche modelling

Modelling of the current and future distribution of the studied species was performed using the maximum entropy method implemented in MaxEnt version 3.3.267,68,69, which is based on presence-only observations. Bioclimatic variables in 30 arc-seconds of interpolated climate surface downloaded from WorldClim v. 2.1 were used for modelling70. The study area was reduced to (30.32–71.67°N, 11.29°W-29.92°E) to improve models71,72.

Pearsons’ correlation coefficient was calculated using SDMtoolbox 2.3 for ArcGIS73,74 (Table S6) and highly correlated (> 0.8) variables were removed from the ENM analyses to prevent autocorrelation problems. The final list of bioclimatic variables used in the analyses is provided in Table S7.

The future extent of orchid climatic niches for 2080- was predicted based on four projections for three Shared Socio-economic Pathways (SSPs): 1–2.6, 3–7.0 and 5–8.575,76,77 developed by the Meteorological Research Institute (MRI-ESM2)78 as this simulation performs well in the analysed geographical area79.

In all analyses the maximum number of iterations was set to 10,000 and convergence threshold to 0.00001. A neutral (= 1) regularization multiplier value and auto features were used. Other regularization multiplier values (0.5 and 2), which control how closely the model fits the training data, were also tested. However, they produced similar or lower area under the curve (AUC) values than the neutral set (0.866 and 0.855 respectively). The “random seed" option provided a random test partition and background subset for each run and 50% of the samples were used as test points. The run was performed as a bootstrap with 100 replicates. The output was set to logistic. We used the “fade by clamping” function in MaxEnt was used to prevent extrapolations outside the environmental range of the training data80. All analyses of GIS data were carried out using ArcGis 10.6 (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). The evaluation of the created models was made using the area under the curve (AUC)81 and the True Skill Statistic (TSS)82.

SDMtoolbox 2.3 for ArcGIS15,16 was used to visualise changes in the distribution of suitable niches for orchid. To compare the distribution model created for current climatic conditions with future predictions all species distribution models (SDMs) were converted into binary rasters and projected using the Goode homolosine as a projection83,84. The presence thresholds used in the analyses equaled the calculated max Kappa value26.

Finally, to estimate the effects of climate change on the genetic structure of the studied populations of O. apifera, the obtained genetic data (clusters and haplotypes) were overlaid on the predicted future areas of suitability for this species, in the SSP5-8.5 scenario in 2070 based on created models.

Bioclimatic preferences of O. apifera outside its native range

For the purposes of this study, we divided the bee orchid’s localities into two datasets: native and non-native. Although the concept of ‘native range’ has been debated in invasion biology85, and in the case of O. apifera, the 'non-native’ populations reflect the dynamic nature of species distribution rather than actual invasion, we use the terms ‘native’ and 'non-native’ to distinguish historical records from newly reported populations.

The database of O. apifera localities (see Table S5) was utilized to organise bioclimatic data. The niche variability of O. apifera was assessed based on 19 variables, both within and outside its native range. . In order to collect a dataset of variable values for native populations of O. apifera, we used historical data (1970–2000) available in WorldClim70. Bioclimatic data for non-native populations were obtained from MRI-ESM2 simulations carried out for the years 2020–2041 (SSP5-8.5 scenario). Before performing the ordination analysis, the data matrix was normalised. Multivariate analyses were conducted to extract relevant bioclimatic information for O. apifera. A preliminary Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA) showed a relatively low gradient length value (< 3 SD units). Therefore, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used as the most suitable method to investigate the variability of species in different climatic niches. A comparative analysis was then performed, based on arithmetic mean and standard deviations to describe the differences in values between bioclimatic variables for locations within and outside the native range. Finally, a Mann–Whitney U-test was calculated (P ≤ 0.05) to compare the means between the two groups of locations, after checking the required assumptions.

Results

Ophrys apifera identification

All analysed sequences were identical (GenBank accession numbers obtained by one of the co-authors are available under the following vouchers: PV290569-PV290577). We also did not observe any peak heterogeneity that could indicate a hybrid nature of the examined individuals. Each individual was homozygous in the studied fragment (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2). A comparative analysis using the BLAST algorithm showed 100% identity with other individuals of O. apifera (KY512506.1, AJ973253.1, AJ539529.1).

Nuclear and plastid diversity in populations of O. apifera

Null alleles were not detected in any of the loci that were analysed. In O. apifera populations, the mean number of alleles per locus was A = 1.5, while at the species level, it was A = 3.0 (Table 1). The effective number of alleles per locus in the population was Ae = 1.37. The POLD population showed the lowest degree of variation, while the POLI demonstrated a higher degree of variability. The average gene diversity (He) ranged from 0.138 to 0.298, with a mean of 0.193. The FIS statistic reached an average value of –0.462 and varied from 0.035 (POLI) to an extreme value of –1.000 (GERB, GERF, POLK, POLM). Inbreeding coefficient values were not positive, which rather indicates an excess of homozygotes. However, an excess of heterozygotes was observed in relation to the expected value in genetic equilibrium, which was evident in virtually all populations studied, with the exception of POLI. At the population level, a negative mean value of the inbreeding coefficient was also recorded (–0.545), associated with an excess of heterozygotes. In addition, analysis of the allele frequency distribution indicated that in the vast majority of O. apifera populations, there has been a recent decline in the number of individuals. Evidence of a genetic bottleneck was found (significant excess heterozygosity compared to equilibrium heterozygosity, He > Heq), where Wilcoxon one-tail tests were significant, except in the POLI population (Table 1).

It was observed that certain low-frequency alleles were exclusively recorded in single populations, indicating their status as private alleles. Several populations (POLI, POLM and CZVP) had at most one, two, or even three such alleles, as observed in the POLI population (data not shown). At the OFCA101 locus, the 166-bp allele, with a frequency of 0.089, was detected in the POLI population. This allele differed by three steps of two base pairs in the repeat motif from the 160-bp allele and one step from the 168-bp allele. At the OFCA36 locus, also in POLI, the 228-bp private allele was observed, which differs by one and two mutation steps from the other two alleles (i.e. 226-bp and 224-bp). At the OaCT6 locus, two private alleles were identified among the four alleles observed: the 156-bp allele for POLM and the 158-bp allele for CZVP, with frequencies of 1.000 and 0.083, respectively. At the last of the loci studied, at the OaCT7, two private alleles were also identified out of five obtained: the 178-bp allele for POLI and the 182-bp allele for POLM, with frequencies of 0.017 and 0.500, respectively. Considering the limited research area, it is possible that these private alleles may no longer be private on a wider scale or in other parts of their range. However, at this stage of the study, they may indicate a unique population as a result of the founder effect or migration direction.

In total, eight fragment size variants were recorded at four plastid loci (Table S8). For a single locus, the number of alleles ranged from one (locus Trn1) to three (locus Rps1). For the other two loci (i.e. Trn2 and Trn4), two alleles each were recorded. Furthermore, analysis of variation across all marker sites revealed the occurrence of seven different haplotypes in the Polish, Czech, and German populations studied here (annotated as HPL1–7). Two of these haplotypes were characterised by widespread occurrence, and their presence was noted in almost 75% of the individuals studied (HPL2 and HPL5). It is noteworthy that certain private haplotypes appear to have originated from the region in which they were identified. For instance, HPL4 was exclusively observed in the POLD population, while HPL7 was present only in the POLI population. The number of haplotypes ranged from one (CZS, CZVP, GERB, GERF and POLM) to 4 (POLI) (Table 1). However, the haplotype richness index exhibited slightly lower values, ranging from 0 to 1.0, with an average RH = 0.31. Nevertheless, at the species level, the haplotype richness was recorded as RH = 6.0. The haplotype diversity ranged from 0.000 to 0.618, with the latter value observed in the POLP population and comparable to that at the species level. The average differentiation between haplotypes was equal to π = 0.076.

Population differentiation and structure

The genetic differentiation for O. apifera was FST = 0.424 (Table S9), and ranged from 0.000 (GERB–GERF) to 0.635 (POLD–POLM) between individual population pairs (Table S3). PCoA analysis and UPGMA clustering were used to summarize the differentiation between populations, and the results of both analyses indicated a clear grouping of the populations (Fig. S1). In the PCO analysis, the percentage of total variation corresponding to the first two components was high (94%), and three distinct groups were observed. The two German populations (GERB and GERF) and the POLM population, located near the western border of Poland, were placed in the right part of the plot. The POLI and CZS populations were positioned in the lower part of the plot on the left side, while the POLD, POLK, POLP and CZVP populations were situated above them, but on the same side, forming a relatively compact group (Fig. S1A). The UPGMA analysis yielded the same clustering of populations (Fig. S1B). Furthermore, the STRUCTURE analysis of the dataset including all individuals indicated a clear mode for K. The most likely number of clusters was determined as K = 3 (Fig. 2A). The first cluster (designated here as Cluster1 – CZS and POL) exhibited the highest degree of admixture and had genotypic combinations with the other two gene pools. The second cluster (Cluster2 – CZVP, POLK, POLP, POLD) displayed a notable degree of consistency, except for the POLD population, which demonstrated a slight genetic affinity to the first cluster. In turn, the third cluster (Cluster3 – POLM, GERB, GERF) was the most coherent and genetically homogeneous, characterised mainly by a single gene pool.

Genetic structure (clusters and haplotypes) integrated with the predicted future areas suitable for O. apifera, in the RCP 8.5 scenario in 2070, based on SDMs. (a) The three clusters obtained by STRUCTURE are presented in pie charts, with proportional membership for K = 3 in each population. (b) The bars reflect the frequency of each plastid haplotype in each population. Maps generated in ArcMap 10.8.2136 (https://www.arcgis.com) and limited to the study area located outside the native range in Central Europe.

The median-joining network illustrating the relationships between the recorded haplotypes for the O. apifera populations that were studied in this research is presented in Fig. 3. All seven recorded haplotypes were linked to each other by single mutational steps, with HPL2 and HPL5 located centrally. A slightly broader picture was obtained when we combined our O. apifera haplotypes with two additional ones for the same species obtained from herbarium materials, together with the Portuguese haplotypes of O. fusca and O. lutea, from Cotrim et al.39. The haplotypes assigned to assigned to bee orchid remained separate in the lower right corner of the network (Fig. S2). HPL8, obtained from an individual from Greece (Crete), was separated by only one mutational step from the rest of our haplotypes. In contrast, HPL9, obtained from Italy (Sicily), was separated by three mutational steps from the rest of our haplotypes, and four from the rest of the network with haplotypes for O. fusca and O. lutea. Although these two species were studied from the same area and only taxonomically assigned haplotypes were selected, they remained widely dispersed and did not form defined haplogroups.

Median-joining network of the plastid haplotypes encountered in the analysed populations of O. apifera. The size of each symbol is proportional to the number of individuals with a particular haplotype, and the sectors are proportional to the number of different populations in which the haplotype was recorded. Mutational steps separating haplotypes are indicated, and branch lengths are approximately proportional to the number of mutational steps.

The two Czech populations were dominated by a single haplotype (CZS by HPL6 and CZVP by HPL5, respectively) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the two German populations were characterised by the presence of only one haplotype, which was fairly widespread in the study material (i.e. HPL2 for GERB and GERF). The same haplotype was also the only one in the POLM population, which is in close geographical proximity. In contrast, the remaining Polish populations showed greater diversity in terms of haplotype composition, with the number of haplotypes ranging from two to four. For instance, the POLD population exhibited HPL2, HPL4 and HPL5, POLI – HPL1, HPL2, HPL3 and HPL7, POLK – HPL5 and HPL6, and POLP – HPL1, HPL2, HPL3, with varying frequencies, respectively. Population differentiation in plastid haplotypes was also revealed by pairwise-FST (Table S4) and subsequently summarised by PCoA analysis and UPGMA clustering (Fig. S3). The resulting plot demonstrated that the percentage of total variation corresponding to the first two components was quite high (86%). Three distinct population groups were observed, with the CZS population remaining separate. On the left side of the graph, a compact grouping of three populations was observed (GERB, GERF, POLM), while the POLI and POLP populations remained in close proximity but formed a separate group (Fig. S3A). In the upper part of the graph, the CZVP, POLK and POLD populations were grouped together but dispersed. The UPGMA analysis gave the same clustering of populations (Fig. S3B). The FST fixation index revealed a high degree of differentiation among O. apifera populations (FST = 0.641) (Table S9).

The hierarchical structure of genetic diversity was calculated for all O. apifera populations and for the population groups obtained in the STRUCTURE analysis. The results of the AMOVA analyses are summarised in Table S9. For nuclear microsatellites, AMOVA analysis showed that 42% of the variation was attributed to inter-population variation, with 58% being attributed to intra-population variation. When the data was divided into three groups (i.e. three clusters in STRUCTURE), similar values for within-population variation were obtained, with population differentiation within groups amounting to 15%. In this case, the differentiation between groups was 32% and 53% was due to within-population variation. For plastid haplotypes, the highest percentage of genetic variation was found between populations (64%). In further analysis by group, the low percentage of genetic variation was attributed to differentiation among them. In this case, the differentiation between populations within groups was 63%, and 36% was due to within-population variation. All estimates were significantly higher than zero (P < 0.001). A significant correlation was found between genetic distances based on both nuclear and plastid data correlated and geographical distances (r = 0.654 and 0.307, respectively; P < 0.05).

Gene flow

The observed population differentiation corresponded to a relatively low level of gene flow (Nm = 0.143) between populations, resulting in a single migrant approximately every seventh generation. In turn, historical gene flow based on estimated Θ values differed among the studied clusters, indicating significant differences in long-term effective population size. Cluster1 showed the highest mean value of Θ (16.75) and median (5.43), suggesting historically large population sizes or high variation in reproductive success. For the remaining populations, Θ values were considerably lower, with mean values ranging from 0.77 (Cluster3) to 0.63 (Cluster2) (Table 2). Low Θ values may reflect recent bottlenecks or high self-pollination rates in some populations.

Migration rates (M) between clusters were variable and asymmetric. The strongest and predominantly unidirectional gene flow was inferred from Cluster2 to Cluster1 (M = 34.33), suggesting potential source–sink dynamics. The remaining cluster pairs revealed moderate bidirectional migration (Table 2). The asymmetric gene flow between the examined populations is also reflected in the values of the effective number of migrants per generation (Nm). The highest Nm values are observed for the directions: Cluster1 → Cluster2 (14.04) and Cluster1 → Cluster3 (12.22), while the lowest Nm value (2.66) occurs between Cluster2 and Cluster3. According to Nm, Cluster1 should be considered as the main historical source of migrants (Table 2).

Current and future potential distribution of O. apifera

Model evaluation and limiting factors

Created models received a high score of AUC (0.866, standard deviation = 0.004), which indicates good reliability of the modelling results presented. The TSS value of 0.54 was acceptable86. According to the results of the jackknife test of variable importance, the environmental variable with the highest gain when used in isolation was bio1, which therefore appears to have the most useful information by itself. The environmental variable that decreased the gain the most when it was omitted was also bio1, which therefore appears to have the most information that isn’t present in the other variables.

Current potential range

The model created for a period close to the present day, showing the current potential range of O. apifera is generally consistent with the known distribution of the orchid, except for the localities in the eastern part of the range (Fig. S4). This is probably the result of the relatively recent expansion of the orchid towards the east and the fact that the bioclimatic layers for the “present” time are based on temperature and precipitation data from 1970 to 2000. Apparently, until 2000, climatic conditions in Eastern Europe were not suitable for the occurrence of O. apifera. However, global warming over the last 25 years has changed the climate in this region, making it suitable for the species under study. To verify this assumption, additional modelling was carried out based solely on data on the occurrence of the species in the wild and MRI-ESM2 projections for 2020–2041. The potential range maps created indicated only some of the regions where O. apifera populations have recently been considered suitable for the occurrence of this species (Figure S5). This result suggests that non-native populations differ in their bioclimatic tolerance from plants occurring in western Europe.

Impact of global warming

Predicted climate change will have a detrimental impact on the ecological niches of O. apifera. Models predict that the total geographical range of this orchid will be 5–19% smaller than currently observed (Table 3, Fig. 4). According to simulations, this species will suffer the greatest habitat losses in the southern and western parts of its range. It is worth noting that the range of O. apifera is predicted to shift north-eastwards, with new ecological niches for this species appearing in the Alps, in many German mountain ranges, in the Carpathians and along the Baltic Sea coast (Fig. 4).

Changes in the distribution of O. apifera suitable niches in various climate change scenarios. Maps generated in ArcMap 10.8.2136 (https://www.arcgis.com) based on MaxENT results.

After taking into account the impact of climate change on the genetic structure of the studied populations of O. apifera, the obtained genetic data (clusters and haplotypes) were superimposed on the predicted future areas suitable for this species in the RCP 8.5 scenario in 2070, based on SDM models (Fig. 2). New Polish populations occurring outside the native range of O. apifera, as well as the studied populations from the Czech Republic and Germany, are located in areas predicted by the above models. For example, these populations were found in the vicinity of the Baltic Sea, in the Carpathians and the Sudetes, which seem to be suitable for further range expansion.

Bioclimatic preferences of O. apifera outside its native range

The PCA biplot illustrates the overall variability of the bioclimatic niche for the bee orchid sites (Fig. 5). The analysis showed that the first two main components explained 90% of the total variance. The variables that had the greatest impact on the overall analysis were: temperature seasonality (bio4); annual precipitation (bio12); precipitation in the driest month (bio14); precipitation seasonality (bio15); precipitation in the wettest quarter (bio16); precipitation in the driest quarter (bio17); precipitation in the warmest quarter (bio18); and precipitation in the coldest quarter (bio19). Individuals occurring outside their native range were grouped in the upper left part of the graph, and this group was determined primarily on the basis of bio4 and bio18. The first principal component (PC1) showed a negative correlation with bio4 and a positive correlation with bio12, while the second (PC2) showed a positive correlation with bio14, bio16, bio17, bio18 and bio19. Statistical analysis showed significant differences between the two location groups, i.e. within and outside the range, for most of the bioclimatic variables studied, with the exception of bio1, bio2, bio5, bio13 and bio16 (P > 0.05; Table S10). Individuals from locations outside the native range appear to be adapted to slightly lower temperatures compared to locations within the native range: the isothermality (bio3) ranged from 23 to 32 °C compared to 19 to 47 °C, the annual temperature range (bio7) ranged from 23–32 °C to 14–34 °C, and they have so far shown tolerance to lower temperatures, with the minimum temperature of the coldest month (bio6) ranging from –6 to 0 °C compared to –7 to 9 °C. The lack of significant differences in the average annual temperature (bio1) and average daily temperature range (bio2) between locations within and outside the native range indicates some similarities in terms of temperatures associated with global warming. Furthermore, O. apifera appears to tolerate slightly lower levels of annual precipitation outside its native range, where the annual precipitation (bio12) ranged from 535 to 967 mm compared to 219–1643 mm in the native range, and the seasonality of precipitation (bio15) ranged from 19 to 50 mm compared to 7 to 88 mm.

Discussion

Reproductive system and genetic structure of populations

In plant biology, the adaptive significance of reproductive and dispersal systems is a key aspect influencing the demographic and genetic structure of populations87,88,89. The evolution of plant reproductive systems is particularly evident at the individual level as a response to changing environmental conditions, including both biotic and abiotic factors90,91,92. Permanent or temporary absence of pollinators can lead to a transition to autonomous self-fertilization, thus providing a mechanism for “reproductive assurance”23,93. It has been shown that the complete absence of pollinators exerts significant selective pressure on flower traits, leading to a transition from allogamous to autogamous flowers94,95,96. The infrequent presence of pollinators can also induce facultative autogamy, usually in the final phase of anthesis90,97. Small population size, low density, increasing fragmentation and isolation of populations, and a limited number of potential mates, pollinators or pollen sources favour self-pollination. There is some evidence that orchids occurring at high latitudes, on islands and at the margins of their geographical or altitudinal range are more prone to self-pollination than orchids occurring at lower latitudes or on the continent28,98,99,100. Consequently, the evolutionary path of a population is determined by the interaction between the benefits of self-pollination for short-term reproductive success and the disadvantages resulting from increased inbreeding. This dynamic interaction has a profound influence on both flower characteristics and the genetic structure of populations101,102,103.

Despite the widespread assumption that obligate cross-pollination occurs in the genus Ophrys, studies have revealed cases of spontaneous self-pollination104. Ophrys apifera is an example of a self-pollinating species, first documented by Darwin in 1862, and later confirmed by Claessens and Kleynen24. It has been observed that the labellum of this species mimics the female insect as a sexual lure, emitting pheromones to attract male long-horned bees. It is noteworthy that in many regions, the bee orchid has the ability to self-pollinate, a phenomenon facilitated by the morphology of its flowers. Although cases of cross-pollination have been reported in the Mediterranean region22, the flowers of this species appear to be mainly self-pollinating in the northern periphery of its geographical range27,28. However, Kullenberg & Bergström21 suggest that O. apifera may have a mixed pollination system. These exceptions challenge the accepted understanding of reproductive strategies within the genus Ophrys and highlight the complexity of their pollination dynamics.

Self-pollination events at the end of the life cycle of some inflorescences may offer a last chance for reproduction in the absence of pollinators. These phenomena, combined with the large number of seeds produced by false orchids, may compensate for the reduced fruit content. However, data on three species of the genus Ophrys (i.e. O. kotschyi, O. aesculapii and O. ferrum-equinum), indicate that despite self-compatibility, they are also susceptible to inbreeding depression, as evidenced by reduced viability and a high percentage of empty seeds produced during self-pollination105. In the case of O. apifera, whose slender caudicles allow for facultative autogamy, exceptionally high average fruit yields of 78 ± 18% have been recorded27. The number of flowers per inflorescence is low throughout the genus, and the fruit set averages < 25%, and often even < 10%27. It has been demonstrated that single pollination event can generate thousands of seeds in orchids106. In the case of Ophrys species, a larger number of seeds are produced per capsule compared to most European orchids, with estimates ranging from 3,000 in O. apifera to 60,000 in O. sphegodes107. However, detailed studies analysing the contents of capsules of various Ophrys species have shown that individual capsules rarely contain more than 1,000 fertile seeds108.

In this study, the inbreeding coefficient was –0.462, and at the species level it was even higher (FIS = –0.545). This result did not clearly indicate autogamy, provided that FIS > 0, although it cannot be completely ruled out for this species, which is considered facultatively autogamous. On the other hand, FIS < 0 indicated an excess of heterozygotes in the population, which may be the result of heterozygote selection, a bottleneck effect or the small size of the studied populations. Negative inbreeding may also indicate assortative mating (i.e. assortative mating occurs when the mating plants are more similar to each other in terms of a certain trait than would be the case for a pair of random plants; this means a positive phenotypic correlation for a given trait between the mating plants109. The only exception was the POLI population, for which the inbreeding coefficient was close to zero. This population also exhibited a higher degree of variation among the populations studied. Furthermore, analysis of the distribution of allele frequencies indicated that the vast majority of the O. apifera populations had experienced a recent decline in the number of individuals, likely due to the colonization of new areas further north. Evidence of a genetic bottleneck was found, with the exception of the POLI population. Furthermore, populations that arose as a result of colonising a new area may possess private alleles resulting from a limited founder gene pool (i.e. the founder effect), which was also observed in this case. Clonality cannot be ruled out, despite the lack of observations and data in the literature.

The observed pattern of variation in the STRUCTURE analysis and the distribution of cpDNA haplotypes may reflect the colonisation history of O. apifera populations in the study area. PCoA and STRUCTURE analyses showed that the populations studied could be categorized into three distinct groups (i.e. the most probable number of clusters was determined as K = 3) (Figs. 2, 3, 4). The first cluster, comprising the CZS and POLI populations, exhibited the highest degree of admixture and had genotypic combinations with the other two gene pools. The second cluster included the CZVP, POLK, POLP and POLD populations, and exhibited a notable degree of consistency, except for the POLD population, which demonstrated a slight genetic affinity to the first cluster. The third cluster, which included the western populations (POLM, GERB, GERF), was the most coherent and genetically homogeneous, characterised mainly by a single genetic pool. With regard to the analysis of plastid haplotypes, it was observed that individual populations were frequently distinguished by a single founding haplotype. Two Czech populations were dominated by a single haplotype (CZS by HPL6 and CZVP by HPL5, respectively) (Fig. 2). A similar observation was made in the two German populations, which were characterised by the presence of only one haplotype, which was quite widely distributed in the material examined (i.e. HPL2 for GERB and GERF). The same haplotype was also the only one in the POLM population, which is in close geographical proximity. In contrast, the Polish populations exhibited greater diversity in terms of haplotype composition, with the number of haplotypes ranging from two to four, with HPL4 occurring exclusively in the POLD populations and HPL7 was only present in the POLI population. . It seems highly likely that there was a long-distance dispersal of seeds from different ancestral populations, and the resulting pattern is caused by a combination of relatively strong, opposing prevailing winds carrying seeds from different directions to Poland (e.g., Föhn and Sirocco are strong winds blowing from south to north across the Alps to Central Europe)110. In the case of orchids, the possibility of long-distance seed dispersal by wind, even up to 2000 km, has been reported repeatedly106,111,112.

The level of genetic variation in O. apifera populations is relatively low, compared to that obtained for other Ophrys species based on a similar set of microsatellite loci39,113,114. On the other hand, these species are distributed in the southern part of Europe and are known for their allogamy through sexual deception, while O. apifera characterised by limited variability resulting primarily from a self-pollination strategy that limits cross-pollination and leads to the formation of genetically homogeneous populations. However, sporadic cross-pollination may still introduce genetic diversity into the population, especially since potential pollinators of the bee orchid are present in Poland, i.e. representatives of the genus Eucera, including E. longicornis115. The estimated level of gene flow was Nm = 0.143, indicating that only one migrant occurs approximately every seventh generation. When gene flow is limited or absent, populations become genetically differentiated, either through natural selection or genetic drift. Forrest et al.116 and Phillips et al. (2012) compiled available data on population differentiation among some orchid taxa and calculated an average FST/GST = 0.187/0.146. The FST value obtained in this study was much higher in nuclear data (FST = 0.424) and even higher for plastid haplotypes (FST = 0.641). Therefore, O. apifera populations show high genetic diversity, probably due to spatial isolation. A positive and significant correlation was observed between genetic and geographical distance for both nuclear and plastid data (r = 0.331 and 0.307 at P < 0.05, respectively). This correlation was entirely caused by differentiation among populations separated by large geographical distances. Furthermore, geographical isolation and restricted seed dispersal contributed to the limited gene flow between populations of O. apifera, as confirmed by our Bayesian cluster analysis and AMOVAs. In turn, the historical gene flow indicated by Migrate-n suggests that Cluster1 was the main source of migrants and had the largest effective population size in the past. Furthermore, asymmetric migration patterns were observed, indicating source-sink dynamics between the studied populations, with a dominant direction of gene flow from Cluster1 to other clusters. However, populations from Cluster 3 appear to originate from a different migration source, as indicated by STRUCTURE analysis and haplotype frequency.

The POLI population in southern Poland stands out from the other populations studied. POLI is probably the first documented population of bee orchid in Poland14 and also appears to be the most ancient. It is suspected that O. apifera entered Poland through the Moravian Gate (a geographical region in the Czech Republic and Poland, a narrow valley between the Sudeten and Carpathian Mountain ranges), where the nearest sites of this taxon are located in Slovakia and the Czech Republic. In 2010, only one individual was recorded14, whereas during the present study in 2024, the estimated population size was 35 individuals (see Table S1). This suggests that a single maternity plant, with one founding haplotype can initiate the development of a new and stable population as a result of the founder effect, provided that environmental conditions are conducive. In addition, favourable southerly winds and the predominant autogamy in the reproductive system of this species at the northern limit of its range may further contribute to the maintenance of the population. Considering that the first green leaves appear two years after seed germination and the plant begins to flower at the age of 9–11 years34,117, further reports of new sites of this species in Poland can be expected, especially as the number of such reports is increasing every year. Accurate determination of the current range and population size of O. apifera in Poland is essential for effective prediction of its future changes under changing environmental and climatic conditions, as well as for its proper protection.

Since “near present” distribution models are based on climate data from 1970–2000, some of the currently known localities of O. apifera are outside the predicted geographical range and were discovered and described largely after these years. Recently reported observations of the bee orchid (outside its native range) are likely the result of a range shift of this species due to global warming. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that both the SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios indicate numerous areas in the eastern part of the “near present” geographical range of O. apifera as suitable for its occurrence. Considering the impact of climate change on the genetic structure of the examined populations of O. apifera, the obtained genetic data (clusters and haplotypes) were superimposed on the predicted future areas suitable for this species under the SSP5-8.5 scenario for 2070, as projected by SDM models. New Polish populations located outside the native range of O. apifera, as well as the studied populations from the Czech Republic and Germany, are located in the regions predicted by the above model. Populations that appear suitable for further range expansion have been identified near the Baltic Sea, in the Carpathians and the Sudetes, which seem to be suitable for further range expansion. The indicated areas may provide a stable environment for the development and maintenance of the identified genetic resources and populations in the near future, but this requires further observation. This scenario is quite optimistic, given the continued protection of O. apifera in Poland and Central Europe. On the other hand, a comparison of the bioclimatic conditions preferred by bee orchid populations showed that populations outside the “native” range differ slightly in terms of habitat preferences. This result suggests that the shift in the range of O. apifera is also related to adaptation to new bioclimatic conditions, however, further research is needed to understand the nature of the morphological, physiological and biochemical response of the bee orchid to global warming118.

According to the simulations carried out in our analyses, it is predicted that most of the southern ecological niches of O. apifera will become unsuitable for the occurrence of this species in the future as a result of global warming. Changes in the range of plant occurrence in response to changes in temperature and precipitation have been reported for many terrestrial119 and marine120 organisms. It is worth noting that although it is generally expected that terrestrial species will move towards the poles or to higher altitudes121, a review of empirical data has shown that, in fact, different species respond differently to global warming122. Recent studies indicate that European forest plants will shift their range westward123. It has been hypothesised that this unusual pattern is related to nitrogen deposition123. According to our research on O. apifera, a general shift in range towards the north-east is predicted, with simultaneous migration to higher altitudes in mountainous regions. A similar pattern of change in the distribution of relevant ecological niches has been described for O. insectifera L.124, which is a non-autogamous species dependent on insect pollination.

Predictive models of niches distribution can be used to increase the effectiveness of conservation measures for rare species125,126. Effective protection of orchids must focus primarily on the conservation of their natural habitats, as ex-situ conservation methods, such as cultivation in botanical gardens, are unable to ensure the continued existence of these plants due to their usually specific habitat requirements and complex ecological interactions with pollinators, mycorrhizal fungi and other endophytes. The narrow ecological tolerance of orchids also poses an obstacle to the reintroduction of Orchidaceae into areas outside their natural habitat after the preservation of their seeds in specialised facilities127,128. It is worth noting that our research was based solely on bioclimatic data, and the ecological relationships crucial for the long-term survival of the bee orchid were not assessed in this study.

Although O. apifera is autogamous, and it does not require pollen vector for fruit production (at least in the northern parts of the range), there are other ecological factors which can prevent its survival under climate change. As with all plants in the Orchidaceae family, the presence of mycorrhizal fungi is crucial for obtaining exogenous nutrients necessary for germination129, but very few previous models have taken this factor into account130. Mycological studies on Ophrys have been limited131 and have shown at best weak mycorrhizal specificity, as described by Liebel et al.132 on representatives of three phylogenetically distinct groups (O. fusca, O. apifera, and O. fuciflora groups). Ophrys apifera, was found to be associated with rather low fungal richness interacting on average with only one to four Tulasnellaceae operational taxonomic units (OTUs) per site, with always one OTU being highly dominant133. Unfortunately, most mycorrhizal fungi of orchids remain unnamed, and data on their distribution are limited, making it impossible to assess the future impact of climate change on their availability in new, altered geographical ranges of Orchidaceae representatives. On the other hand, the significant invasive capacity shown by some Ophrys lin in rapidly colonising anthropogenically disturbed areas (for example, such as areas in quarries—POLI and POLP populations or a mine heap in POLD population) suggests a lack of specialisation or reduced dependence on mycorrhiza compared to many other European orchid taxa131. Undoubtedly, the inclusion of fungal partners in modelling would improve the reliability of the predictions130,134.

Our analyses allowed us to identify areas that will be climatically suitable for the occurrence of O. apifera in the future and that can be considered climate refugia for this species. However, due to the lack of data on the availability of mycorrhizal fungi and/or confirmed pollinators for bee orchid populations in the new geographical range, their long-term survival may be threatened.

Conclusions

It has been shown that rising average temperatures and climate change have a direct impact on the geographical distribution of O. apifera, and that this species is appearing in new areas, such as Poland. The small, light seeds of this orchid can be carried over long distances by the wind, which facilitates its natural spread. The occurrence and proportions of individual haplotypes and alleles in the studied populations of O. apifera suggest long-distance dispersal, and it can be hypothesised that genetic diversity has been reduced as a result of a bottleneck associated with the colonisation of new areas in the north. Our research has indicated which areas within the current geographical range of the orchid will become unsuitable for the occurrence of this species as a result of global warming. Finally, the maps developed in our analyses should be taken into account when planning conservation measures, as these graphs show the location of climate refuges for O. apifera.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available as supplementary information. Any additional requests for materials should be addressed to A.M.N and M.K. The DNA sequences obtained by Marcin Górniak (M.G.) have been deposited in the NCBI database (voucher numbers: PV290569-PV290577) but will be made publicly available on March 20, 2025. The genotype data obtained for nuclear microsatellites and plastid haplotypes by Aleksandra M. Naczk (A.M.N.). All raw data used to perform the ENM analyses are provided as supplementary files.

References

Abbass, K. et al. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 42539–42559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-19718-6 (2022).

Chen, I.-C., Hill, J. K., Ohlemüller, R., Roy, D. B. & Thomas, C. D. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 333, 1024–1026. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1206432 (2011).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-1937-2016 (2016).

Wei, L. et al. Predicting suitable habitat for the endangered tree Ormosia microphylla in China. Sci. Rep. 14, 10330. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61200-5 (2024).

Adedoja, O. A., Dormann, C. F., Coetzee, A. & Geerts, S. Moving with your mutualist: Predicted climate-induced mismatch between Proteaceae species and their avian pollinators. J. Biogeogr. 51, 992–1003. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14804 (2024).

Cho, K. H., Park, J.-S., Kim, J. H., Kwon, Y. S. & Lee, D.-H. Modeling the distribution of invasive species (Ambrosia spp) using regression kriging and Maxent. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 4523. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.1036816 (2022).

Di Febbraro, M. et al. Different facets of the same niche: Integrating citizen science and scientific survey data to predict biological invasion risk under multiple global change drivers. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 5509–5523. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16901 (2023).

van der Pijl, L. & Dodson, C. An atlas of orchid pollination. America, Africa, Asia and Australia 308 (A.A. Balkema Publishers, 1966).

Dearnaley, J. D. W. Further advances in orchid mycorrhizal research. Mycorrhiza 17, 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-007-0138-1 (2007).

Meusel, H., Jäger, E. & Weinert, E. Vergleichende Chorologie der Zentraleuropäischen Flora (VEB Verlag von Gustav Fischer,, 1965).

Kühn, R., Cribb, P. & Pedersen, H. Æ. Field guide to the orchids of Europe and the Mediterranean (Kew Publishing, 2019).

Kaplan, Z. et al. Distributions of vascular plants in the Czech Republic Part 11. Preslia 94, 335–427 (2022).

Bateman, R. M. Systematics and conservation of British and Irish orchids: a “state of the union” assessment to accompany Atlas 2020. Kew. Bull. 77, 355–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-022-10016-5 (2022).

Osiadacz, B. & Kręciała, M. Ophrys apifera Huds (Orchidaceae), a new orchid species to the flora of Poland. Biodiv. Res. Conserv. 36, 11–16 (2014).

Wójcicka-Rosińska, A., Rosiński, D. & Szczęśniak, E. Ophrys apifera Huds (Orchidaceae) on a heap of limestone mine waste – the first population found in the Sudetes and the second in Poland. Biodiversity Research and Conservation 59, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.2478/biorc-2020-0007 (2020).

Mattiasson, G. Om fyra nya Skånearter. Sven. Bot. Tidskr. 109, 340–345 (2015).

Zimmermann, F. Verbreitung und gefährdungssituation der heimischen orchideen (orchidaceae) in Brandenburg Teil 3: Stark gefährdete, gefährdete und ungefährdete Arten sowie Arten mit unzureichender Datenlage. Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege in Brandenburg 20, 80–96 (2011).

Lüdicke, T. Erstnachweis für Ophrys apifera Hudson in Brandenburg. Natursch. Landschaftspfl. Brbg. 16, 57–58 (2007).

Zimmermann, F. Die Orchideen Brandenburgs – Verbreitung, Gefährdung. Schutz. Ber. Arbeitskrs. Heim. Orchid. 35, 4–147 (2018).

Kullenberg, B. Studies in Ophrys pollination. Zool. Bidrag Fran Uppsala 34, 1–340 (1961).

Kullenberg, B. & Bergström, G. Hymenoptera Aculeata males as pollinators of Ophrys orchids. Zoolog. Scr. 5, 13–23 (1976).

Fenster, C. B. & Martén-Rodríguez, S. Reproductive assurance and the evolution of pollination specialization. Int. J. Plant Sci. 168, 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1086/509647 (2007).

Darwin, C. Various Contrivances by Which Orchids Are Fertilized by Insects. (John Murray, 1877).

Claessens, J. & Kleynen, J. Investigations on the autogamy in Ophrys apifera Hudson. Jahresbericht des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins Wuppertal 55, 62–77 (2002).

Mossberg, B. & Æ., P. H. Orkideer i Europa. (Gyldendal, 2017).

Kullenberg, B. Hymenoptera aculeata males as pollinators of Ophrys orchids. Zool. Scr. 5, 13–23 (1976).

Claessens, J. & Kleynen, J. The Flower of the European Orchid: Form and Function (Self Published, 2011).

Ackerman, J. D. et al. Beyond the various contrivances by which orchids are pollinated: global patterns in orchid pollination biology. Bot. J. Linnean Soc. 2023, boac082. https://doi.org/10.1093/botlinnean/boac082 (2023).

Wells, T. C. E. & Cox, R. in Population ecology of terrestrial orchids (eds T. C. E. Wells & J. H. Willems) 47–61 (Academic Publishing, 1991).

Heinrich, W. & Dietrich, H. Heimische Orchideen in urbanen Biotopen. Feddes Repertorium 119, 388–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/fedr.200811172 (2008).

La Croix, I. The new encyclopedia of orchids : 1500 species in cultivation (Timber Press, 2008).

Pedersen, H. A. & Faurholdt, N. Ophrys: a guide to the bee orchids of Europe (Kew Publishing, 2007).

Harrap, A. & Harrap, S. Orchids of Britain and Ireland. 2nd ed. (A and C Black Publ. Ltd., 2009).

Summerhayes, V. S. Wild Orchids of Britain (Collins, 1951).

Doyle, J. J. & Doyle, J. L. A Rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19, 11–15 (1987).

Soliva, M., Kocyan, A. & Widmer, A. Molecular phylogenetics of the sexually deceptive orchid genus Ophrys (Orchidaceae) based on nuclear and chloroplast DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 20, 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1006/mpev.2001.0953 (2001).

Sun, Y., Skinner, D. Z., Liang, G. H. & Hulbert, S. H. Phylogenetic analysis of Sorghum and related taxa using internal transcribed spacers of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Theor. Appl. Genet. 89, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00226978 (1994).

Cotrim, H. et al. Isolation and characterization of novel polymorphic nuclear microsatellite markers from Ophrys fusca (Orchidaceae) and cross-species amplification. Conserv. Genet. 10, 739–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-008-9634-x (2009).

Cotrim, H., Monteiro, F., Sousa, E., Pinto, M. J. & Fay, M. F. Marked hybridization and introgression in Ophrys sect Pseudophrys in the western Iberian Peninsula. Am. J. Bot. 103, 677–691. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1500252 (2016).

Barton, N. H. & Slatkin, M. A Quasi-equilibrium theory of the distribution of rare alleles in a subdivided population. Heredity 56, 409–415. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.1986.63 (1986).

Rousset, F. genepop’007: a complete re-implementation of the genepop software for Windows and Linux. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 8, 103–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01931.x (2008).

Goudet, J. http://www2.unil.ch/popgen/softwares/fstat.htm (2001).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/155.2.945 (2000).

Falush, D., Stephens, M. & Pritchard, J. K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 164, 1567–1587. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567 (2003).

Li, Y.-L. & Liu, J.-X. StructureSelector: a web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 18, 176–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12719 (2018).

Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x (2005).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4, 1–9 (2001).

Cornuet, J. M. & Luikart, G. Description and power analysis of two tests for detecting recent population bottlenecks from allele frequency data. Genetics 144, 2001–2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/144.4.2001 (1996).

Van Oosterhout, C., Hutchinson, W. F., Wills, D. P. M. & Shipley, P. micro-checker: software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol. Ecol. Notes 4, 535–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8286.2004.00684.x (2004).

Beerli, P. & Felsenstein, J. Maximum likelihood estimation of a migration matrix and effective population sizes in n subpopulations by using a coalescent approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 4563–4568. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.081068098 (2001).

Beerli, P. & Palczewski, M. Unified framework to evaluate panmixia and migration direction among multiple sampling locations. Genetics 185, 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.109.112532 (2010).

Nei, M. & Li, W. H. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76, 5269–5273. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269 (1979).

Tajima, F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123, 585–595. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/123.3.585 (1989).

Nei, M. Molecular evolutionary genetics (Columbia Univ, 1987).

Eliades, N. G. & Eliades, D. G. Haplotype Analysis: Software for Analysis of Haplotypes Data. (Forest Genetics and Forest Tree Breeding, Georg-Augst University Goettingen, 2009).

Bandelt, H.-J., Forster, P. & Röhl, A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16(1), 37–48 (1999).

Slatkin, M. Inbreeding coefficients and coalescence times. Genet. Res. 58, 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0016672300029827 (1991).

Excoffier, L. & Lischer, H. E. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 564–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x (2010).

Liedloff A. C. Mantel Nonparametric Test Calculator. Version 2.0 (School of Natural Resource Sciences. Brisbane, QueenslandUniversity of Technology, 1999).

GBIF.org. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (2023).

Tashev, A., Vitkova, A. & Russakova, V. Distribution of Ophrys apifera Huds (Orchidaceae) in Bulgaria. Flora Mediterranea 16, 247–252 (2006).

Szatmari, P.-P. Ophrys apifera (Orchidaceae) in Transylvanian Flora, Romania. Acta Horti Bot. Bucurest. 43, 31–40 (2016).

Anastasiu, P. New chorological data for rare vascular plants from Romania. Acta Horti Bot. Bucurest. 42, 57–62 (2015).

Djordjević, V., Lakušić, D., Jovanović, S. & Stevanović, V. Distribution and conservation status of some rare and threatened orchid taxa in the central Balkans and the southern part of the Pannonian Plain. Wulfenia 24, 143–162 (2017).

Luoto, M. & Heikkinen, R. K. Disregarding topographical heterogeneity biases species turnover assessments based on bioclimatic models. Glob. Change Biol. 14, 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01527.x (2008).

Sorbe, F., Gränzig, T. & Förster, M. Evaluating sampling bias correction methods for invasive species distribution modeling in Maxent. Eco. Inform. 76, 102124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102124 (2023).

Elith, J. et al. A statistical explanation of MaxEnt for ecologists. Divers. Distrib. 17, 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2010.00725.x (2011).

Phillips, S., Anderson, R. & Schapire, R. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 190, 231–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026 (2006).

Phillips, S. & Dudik, M. Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 31, 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0906-7590.2008.5203.x (2008).

Fick, S. & Hijmans, R. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086 (2017).

Anderson, R. & Raza, A. The effect of the extent of the study region on GIS models of species geographic distributions and estimates of niche evolution: preliminary tests with montane rodents (genus Nephelomys) in Venezuela. J. Biogeogr. 37, 1378–1393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02290.x (2010).

Barve, N. et al. The crucial role of the accessible area in ecological niche modeling and species distribution modeling. Ecol. Model. 222, 1810–1819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2011.02.011 (2011).

Brown, J. SDMtoolbox: a python-based GIS toolkit for landscape genetic, biogeographic and species distribution model analyses. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5, 694–700. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12200 (2014).

Brown, J. L., Bennett, J. R. & French, C. M. SDMtoolbox 2.0: the next generation Python-based GIS toolkit for landscape genetic, biogeographic and species distribution model analyses. PeerJ 5, e4095. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4095 (2017).

McGee, R., Williams, S., Poulton, R. & Moffitt, T. A longitudinal study of cannabis use and mental health from adolescence to early adulthood. Addiction 95, 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9544912.x (2000).

Meinshausen, M. et al. The shared socio-economic pathway (SSP) greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions to 2500. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 3571–3605. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-3571-2020 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Coupled SSPs-RCPs scenarios to project the future dynamic variations of water-soil-carbon-biodiversity services in Central Asia. Ecol. Indic. 129, 1452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107936 (2021).

Yukimoto, S. et al. The meteorological research institute earth system model version 2.0, MRI-ESM2.0: description and basic evaluation of the physical component. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II 97, 931–965. https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2019-051 (2019).

Parding, K. M. et al. GCMeval – an interactive tool for evaluation and selection of climate model ensembles. Clim. Serv. 18, 100167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2020.100167 (2020).

Owens, H. et al. Constraints on interpretation of ecological niche models by limited environmental ranges on calibration areas. Ecol. Model. 263, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2013.04.011 (2013).

Mason, S. & Graham, N. Areas beneath the relative operating characteristics (ROC) and relative operating levels (ROL) curves: Statistical significance and interpretation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 128, 2145–2166. https://doi.org/10.1256/003590002320603584 (2002).

Allouche, O., Tsoar, A. & Kadmon, R. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J. Appl. Ecol. 43, 1223–1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01214.x (2006).