Abstract

Fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) are still in the early phases of development, largely influenced by policy measures. However, the current support policies have not effectively fostered the growth of the FCEV industry. Moreover, most existing research is based on qualitative analysis, which falls short in tackling this issue. This study developed a policy evaluation model that combines the analytic hierarchy process and content analysis (AHP-CA) to assess the differences between ideal and actual policy distributions, grounded in AHP and CA theories. Furthermore, CA-industry chain analysis model and CA-value chain analysis model were constructed. These models utilize a two-dimensional matrix to evaluate how policies are distributed across the industry chain and value chain. The results show that: In terms of policy types, preferential fiscal and tax policies exhibited a large negative deviation (-0.29), while comprehensive macro-policies policies exhibited a large positive deviation (0.17). In terms of policy instruments, demand-oriented policy instruments demonstrated a large negative deviation (-0.09), while environment-oriented ones demonstrated a large positive deviation (0.06). In terms of specific policy measures, a large negative deviation was observed in government procurement (-0.15), and a large positive deviation in policy strategies (0.13). From the perspective of the industrial chain and value chain, the supply side still needs to be further strengthened. It is proposed to enhance fiscal and tax preferential policies to further address the economic barriers in the early stages of FCEV industry development. Specifically, a demand-oriented approach should be adopted, with government procurement as the main measure. Additionally, efforts should be made to guide the improvement of supply-side capabilities and to enhance the demonstration and guidance for private consumption. Future research will focus on ways to classify policies and policy-making mechanisms that can adapt to changes over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major countries across the world have set the goal of achieving carbon neutrality around the 2050s1,2. In this context, China also proposed in September 2020 the goal to peak its carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 20603. Achieving this goal necessitates joint efforts of all high-carbon emission sectors such as transport, construction, industry and energy sectors as the automobile industry is highly associated with these sectors. According to a study by the International Energy Agency (IEA), for the transport sector alone, its petroleum consumption accounted for 61.2% of the total global petroleum consumption, and its carbon dioxide emissions represented 23% of the global’s total4. Under the pressure from energy crisis and the need for environmental protection, FCEVs have gradually attracted attention from China and abroad for their excellent features such as environmental friendliness, short refueling time and superior driving range. As a result, countries with well-developed auto industries have been introducing relevant policies to support the development of such vehicles5,6,7,8,9.

Literature review and motivation

Since 2009, China has issued a series of supporting policies. These policies mainly fall under four types: comprehensive macro-policies, industry management policies, preferential fiscal and tax policies, and scientific & technological (S&T) innovation policies. However, China’s supporting policies for FCEVs are mostly integrated into those for new energy vehicles. For this reason, scholars in China have studied supporting policies concerning new energy vehicles (NEVs) more frequently than those regarding FCEVs in a considerable period. Overall, studies have transitioned from qualitative research to semi-qualitative or quantitative analysis. Dai Yulong established an AHP-fuzzy comprehensive analysis model to study the impact of government policies on the NEV industry10. Huang Yadi, Liu Jiali, Luo Yihan et al. established a difference-in-differences model to analyze the impact of policies on the new energy vehicle industry11,12,13,14. More detailed research has gone deep into the policy text, and has been combined closely with the industry chain and value chain. Chen Yongguo et al., Yang Chengyuan, Yang Changjin et al., Zhou ying et al. studied the policy texts regarding China’s NEV industry in terms of policy instruments and made suggestions for policy adjustment15,16,17,18. Wang Jing et al. established a two-dimensional analysis framework for policy texts, analyzed 105 relevant policies, and concluded that current environment-oriented policy instruments were excessive19. Wang Zihan, Xu Junhan have both conducted research on the support policies for the NEV industry using the CA method, considering three dimensions: the industry chain, the value chain, and policy instruments20,21.

In recent years, China has adopted specific policies for FCEVs and yet limited studies focus on the supporting policies for FCEVs. The research on support policies for FCEVs is also gradually increasing, but most of it is from the broader perspective of hydrogen energy. Yu has studied the tax and fiscal policies for China’s hydrogen industry, suggesting that the formulation of fiscal policies should be closely integrated with the entire hydrogen industry chain22. Yao et al. focused on analyzing China’s hydrogen technology policies during the 14th Five-Year Plan period and put forward specific suggestions for future research and development23. Wang et al. conducted research on China’s hydrogen industry policies, arguing that there are still many policy bottlenecks in various links of China’s hydrogen industry24. Huang used natural language processing technology to mine and analyze China’s hydrogen policies, and proposed four suggestions: strengthening top-level design, enhancing technological innovation, clarifying development goals, and reinforcing government funding guidance25. There is relatively little research focusing specifically on support policies for FCEV, and most of it is qualitative analysis. Kong et al. studied the management policies for FCEVs and suggested adding requirements related to the unique attributes of FCEVs26. Li analyzed the policy status of FCEVs, believing that policies support the development of FCEVs27. It can be observed that research on support policies for FCEVs in China is still in its infancy, with only qualitative studies conducted on macro-comprehensive and industry management policies. Research on hydrogen policies indirectly reflects that the FCEV industry chain is longer and more complex than those of other NEVs. It is important to mention that this study focuses solely on national policies and does not take into account the relationship between national and local policies. Without quantitative and precise assessments, it is clearly impossible to identify the root causes of the existing policy system’s inability to effectively promote the development of the FCEV industry, thus providing limited support for policymakers.

From above, China has provided long-term support for developing the FCEV industry and established a relatively comprehensive policy support system that is synchronized to benefit other types of NEVs. However, the manufacturing and sales of FCEVs have remained at the thousand-unit level for an extended period, significantly lower than other categories of NEVs. The existing policy framework has failed to effectively promote the development of the FCEV industry, with evident policy failure issues. The existing preliminary qualitative analysis can no longer solve this problem. This study, based on the research on NEVs, has constructed a FCEV policy evaluation model with the AHP and CA as the theoretical basis. It takes China’s FCEV policy support system (hereinafter referred to as the Policy System) as the research object, and collects and classifies relevant policy documents under the guidance of experts. China’s FCEV support policies were also systematically evaluated in terms of policy types, policy instruments, specific policy measures, as well as the industry chain and value chain. The objective of this study is to conduct a systematic and quantitative investigation of support policies for FCEVs with the following aims.

1) To systematically review the various support policies for FCEVs in China, providing a foundational and reference policy framework for this study and future research.

2) To conduct a quantitative analysis of the gap between existing research policies and actual needs, providing precise support for policymakers.

3) To establish a methodological framework for dynamically tracking changes in policy systems and actual needs, thereby providing long-term support for policymakers.

Outline

The structure of this paper is as follows: In Sect. “Introduction”, the background and the aim of this study are described. Section “ Research methods” focuses on the research methods. The policy evaluation model is summarized in Sect.“Policy evaluation model”. Section “Evaluation of policy system” describes the evaluation process. The results of this evaluation are summarized in Sect. “Results and discussion”. Finally, the findings of this study are summarized in Sect. “Conclusion and policy implications”.

Research methods

While techniques like system dynamics and CGE modeling are commonly employed in policy research, they primarily focus on quantitatively assessing the impact of policies, making it challenging to directly measure the deficiencies within the policies themselves. The AHP-CA method introduced in this study addresses these limitations.

Analytic hierarchy process

The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) is a qualitative and quantitative multi-objective decision-making (MODM) analysis method proposed in the early 1970 s by Statty T, a U.S. operational researcher28,29,30. It is a key method in policy evaluation employed for qualitative and quantitative analysis based on decomposing decision-making elements into the levels of objectives, criteria, and schemes.

It consists of three main steps: (1) Establish a hierarchical structure model to determine the factors at the levels of objectives, criteria and schemes to achieve objectives by analyzing research problems; (2) Construct a pairwise comparison (judgment) matrix to analyze and calculate the importance of factors at the same level relative to objective constraints by using a 9-level scaling method, as shown in Table 1 to assign values to elements of the judgment matrix; (3) Check consistency by calculating the maximum eigenroot and corresponding eigenvector for each pairwise comparison matrix and using consistency index, random consistency index and consistency ratio.

Content analysis

Content Analysis (CA) is a specific method for objectively, systematically and quantitatively describing the content of literature, with the purpose of clarifying or measuring the essential facts and trends in literature. It has been widely used for detailed analysis of policy texts, mainly reflecting the dimension of policy instruments. It can also be expanded to the industry chain and value chain.

Policy instruments can be classified based on multiple standards and methods, including the widely-used theory of Rothwell and Zegveld31,32 which classifies policy instruments into supply-, environment- and demand-oriented ones depending on their nature at the impact level. Twelve types of specific policy measures are technical support, talent introduction, financial support, S&T facility, finance and taxation, publicity and science popularization, regulatory control, policy strategy, government procurement, demonstration and promotion, public service, and overseas institution.

The industry chain mainly encompasses parts, vehicles, infrastructure, sales and other links. The value chain mainly covers research and development (R&D), investment, production, consumption and use.

Policy evaluation model

The policy evaluation model for FCEVs is primarily based on the AHP and the CA methods, both of which can delve into the analysis of specific policy measures. Within the same framework, the support policies for FCEVs are categorized into three layers: the objective layer, the criteria layer, and the scheme layer. The specific policy measures form the scheme layer, different types of policy documents constitute the criteria layer, and the objective layer represents the entire policy system for supporting FCEVs. Based on this framework, separate AHP and CA policy evaluation models for FCEVs are established to obtain the ideal and actual matrices of the support policies. The difference between these two matrices can quantify the deviation of the policies.

AHP analysis

Based on the AHP, national policies were designated as the level of objectives. National policies in the database were classified based on their characteristics into four types: comprehensive macro-policies, industry management policies, S&T innovation policies, and preferential fiscal and tax policies. These four types constitute the level of criteria Based on the CA, these four types of national policies can be summarized based on their roles into three types of policy instruments: supply-oriented, environment-oriented and demand-oriented. These three types of policy instruments can be subdivided into 12 specific policy measures that constitute the level of schemes. The hierarchy of indexes is shown in Fig. 1.

A judgment matrix between evaluation indexes at P and T levels was designed to calculate the weight coefficients of different indexes for a further consistency check, as shown in Formula (1).

Where, P represents national policies; \({T_h}{T_s}\)represents the judgment matrix for relative importance of different policy types.

A judgment matrix between evaluation indexes at T and Y levels was designed to calculate the weight coefficients of different indexes for a further consistency check, as shown in Formula (2).

\({T_{u=1,2,3,4}}\)represents four policy types (comprehensive macro-policies, industry management policies, S&T innovation policies, and preferential fiscal and tax policies); \({Y_h}{Y_s}^{u}\)represents the judgment matrix for relative importance of different policy instruments.

A judgment matrix between evaluation indexes at Y and Z levels was designed to calculate the weight coefficients of different indexes for a further consistency check, as shown in Formulas (3)–(5).

Where, \({Y_1}\)represents the supply-oriented policy instruments; \({Y_2}\)the environment-oriented policy instruments; \({Y_3}\)the demand-oriented policy instruments; \({Z_h}{Z_s}\)(h = 1,2,3,4 s = 1,2,3,4), \({Z_h}{Z_s}\)(h = 5,6,7,8 s = 5,6,7,8), and \({Z_h}{Z_s}\)(h = 9,10,11,12 s = 9,10,11,12) represent judgment matrices for relative importance of different measures of the supply- oriented, environment- oriented, and demand-oriented policy instruments, respectively.

Content analysis

Based on the relative importance weights determined for policy instruments and their 12 specific measures by using the AHP, the CA was used to analyze the actual situation of the research object. Specific models are shown in Formulas (6)–(9).

Where, \({D_{ijklo}}\) represents policy documents; i the type of a policy document; j Chapter j; k Section k; l the type of a policy instrument; s the supply-oriented policy instrument, e the environment-oriented policy instrument, and r the demand-oriented policy instrument; o the name of 12 policy instruments;\({d_{ijklo}}\) the policy analysis unit; \({S_{ijklo}}\)the number of supply-oriented policies in all current analysis units; \({E_{ijklo}}\)the number of environment-oriented policies in all current analysis units;\({R_{ijklo}}\)the number of demand-oriented policies in all current analysis units.

As an emerging sector of strategic importance, the FCEV industry shows distinctive inherent development laws and characteristics which should be taken into full consideration in formulation of national policies. Based on its inherent activity patterns and characteristics, policy instruments were further analyzed from the perspectives of both the industry chain and value chain as its typical characteristics cannot be fully revealed from the dimension of policy instruments alone.

CA-industry chain analysis

The industry chain analysis is shown in Formulas (13)–(14).

Where, C denotes all elements of the industry chain; \({C_1}\) the parts; \({C_2}\) the vehicles; \({C_3}\) the infrastructure; \({C_4}\) the sales and other links; \({C_c}\) the sum of the roles of all current policy instruments in a link of the industry chain.

CA-value chain analysis

The value chain analysis is shown in Formulas (15)–(16).

Where, V denotes all elements of the value chain; \({V_1}\) the R&D; \({V_2}\) the investment; \({V_3}\) the production; \({V_4}\) the consumption; \({V_5}\) the use; \({V_v}\) the sum of the roles of all current policy instruments in a link of the value chain.

Evaluation of policy system

Evaluation based on AHP

Index evaluation system

In the evaluation model, national policies regarding FCEVs are classified into four types: comprehensive macro-policies, industry management policies, S&T innovation policies, and preferential fiscal and tax policies33. At different element levels, specific indexes selected in this study are shown in Table 2.

Calculation and consistency check

According to AHP evaluation model, this study invited 5 experts who engaged in policy research of FCEVs and directly or indirectly participated in policy formulation. They carried out pairwise comparisons of the relative importance of all indexes based on their expertise and the current status of the FCEV industry with reference to 9-level scaling method shown in Table 1. It should be noted that these experts conducted surveys on typical stakeholders involved in the research process, including 7 vehicle manufacturers and 15 key component suppliers. According to the comparison results obtained, the judgment matrix was designed for each index at each level. To obtain the weight of each factor, it is necessary to solve the eigenroot of the judgment matrix to obtain the eigenvector and then normalize the eigenvector. Typically, the eigenvalue and eigenvector of the judgment matrix are approximated due to the difficulty of exact calculation. Based on a prior study34the summation method was applied for approximate calculations in this study.

The arithmetic mean of all column vectors was used to estimate the weight vector, as shown in Formula (17).

Where, \({W_i}\) is the eigenvector; \({b_i}_{j}\) is the value of each factor in the judgment matrix.

To check the consistency, it is required to calculate the maximum eigenroot, as shown in Formula (18).

Where,\({\lambda _{\hbox{max} }}\) denotes the maximum eigenroot; B the judgment matrix.

Each element in the judgment matrix is obtained by pairwise comparison with the scaling method, so errors are inevitable. To make the matrix more practical, a consistency check is required. The consistency index is calculated as shown in Formula (19).

Where, \(CI\) is the consistency index; n denotes the order of the judgment matrix.

The value of the mean random consistency index (RI) is given in reference35.

The random consistency ratio (CR) is calculated as shown in Formula (20).

If CR < 0.10, the judgment matrix meets the consistency requirements. Otherwise, the elements in the matrix must be adjusted until requirements are met.

Evaluation based on CA

Sample selection

This paper studied the supporting policies issued by the government and competent ministries and commissions regarding FCEVs. To evaluate these policies in a scientific and systematic manner, a database regarding national FCEV industry policies was created based on available policy documents and associated principles by collecting data till December 2022. As of now, 56 main national incentive policies have been collected in this database that will be further enriched and updated as new policies are introduced.

Definition and coding of analysis unit

With reference to the research results of other scholars on different industrial policy texts and in combination with the characteristics of national FCEV industry policy texts, relevant clauses in a policy text are defined as the analysis unit. In this study, 94 analysis units were selected from 56 policy texts.

For clear classification, these analysis units were coded. In this paper, 56 national FCEV industry policy texts were coded in the form of policy serial number - chapter number - clause number. Specific codes are shown in Table 3.

To ensure the reliability and validity of coding analysis, well-established research findings were fully drawn on for constructing the analysis framework of policy texts, and 5 experts in this field were invited to review the framework. It should be emphasized that these experts are entirely distinct from the five experts mentioned in Sect. “Calculation and consistency check”. Additionally, the definitions and classifications of policy instruments, industry chain and value chain were refined under the guidance of these experts. The coding was carried out by 3 engineers of our research team respectively. The coding analysis results of 20 policies were randomly selected and checked for consistency by using SPSS 26.0 software36. The Kappa coefficient reached 0.837, indicating high coding reliability.

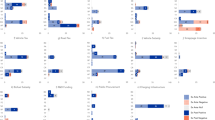

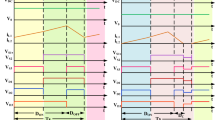

CA - industry chain evaluation

A two-dimensional analysis framework of policy instruments - industry chain was established with the former as the x axis and the latter as the y axis to analyze policy texts, as shown in Fig. 2.

CA - value chain evaluation

A two-dimensional analysis framework of policy instruments - value chain was established with the former as the x axis and the latter as the y axis to analyze policy texts, as shown in Fig. 3.

Results and discussion

Results of AHP analysis

Based on Formulas (1)–(5) and (17)–(20) and expert questionnaire results, the weight was obtained for each factor in national policies, comprehensive macro-policies, industry management policies, S&T innovation policies, preferential fiscal and tax policies, as well as supply-, environment-, and demand-oriented policy instruments, as shown in Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

Based on the calculated weight at each index level, the final weight of each factor in national policies was obtained, as shown in Table 12.

As shown in Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12, the combination of the policy type - policy instrument - specific policy measure forms the policy transmission path from macro to micro. A total of 48 policy paths were covered in this study. According to the current stage of industrial development, the ideal policy system structure has the highest proportion of T4-Y2-Z5 policy paths, which should reach 21.83%, followed by T4-Y3-Z9 policy paths, which should reach 9.16%, followed by T4-Y2-Z8, T4-Y2-Z7, and T3-Y1-Z1, which should reach 8.08%, 6.74%, and 5.89%, respectively. Further analysis shows that preferential fiscal and tax policies and S&T innovation policies are urgently needed by the industry; the environment-oriented and demand-oriented policy instruments are the most important in preferential fiscal and tax policies; the supply-oriented policy instruments are the most important in S&T innovation policies; the fiscal and financial measures are the most urgent in the environment-oriented policy instruments of preferential fiscal and tax policies. The results align with current challenges faced by FCEVs, which involve high costs, immature technology, and application scenarios to be explored. If relevant policies can be adopted to reduce FCEVs’ operating costs and initiate their use in appropriate application scenarios, effective policy support will be formed for their rapid development by continuously advancing the technology of FCEVs through actual verification.

Results of CA

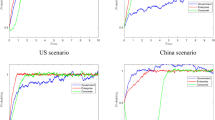

Based on the database created in the early stage, the selected policies were sorted in chronological order and counted according to the phases of the “three-step” strategy for electric vehicles in China, as shown in Fig. 4.

As shown in Fig. 4, the number of incentive policies for FCEVs in China increased significantly from 4 in Phase I to 20 in the Phase II, and even to 32 in Phase III by 2020. Driven by policies, the FCEV industry has developed from the scratch to the current level.

Based on Formulas (6)–(12) and the database created, the actual proportion of current national policies for FCEVs was obtained, as shown in Table 13.

As shown in Table 13, in the current policy system structure, the T3-Y1-Z1 policy path accounts for the highest proportion, reaching 19.15%, followed by T4-Y2-Z5, reaching 17.03%, and followed by T2-Y2-Z7, T1-Y2-Z8, T4-Y2-Z8, reaching 9.57%, 8.51% and 7.45%, respectively. Further analysis shows that the current preferential fiscal and tax policies and S&T innovation policies account for a large proportion in the FCEV industry, and the gap between the two is not large. A high proportion was observed in environment-oriented policy instruments of preferential fiscal and tax policies and supply- oriented policy instruments of S&T innovation policies. Technical support measures are used most in supply-oriented policy instruments of S&T innovation policies. Practically, China’s current supporting policies for FCEVs primarily focus on the R&D stage, which can solve some technical problems, but cannot effectively support the commercialization of FCEVs.

Results of AHP-CA analysis

Based on the analysis results of AHP (ideal distribution) and CA (actual distribution), the deviations in 4 different types of national policies were analyzed, as shown in Fig. 5.

As shown in Fig. 5, preferential fiscal and tax policies exhibited the largest deviation, with a weaker actual distribution than the ideal distribution. It is mainly caused by the high cost of FCEVs, necessitating more preferential fiscal and tax policies to offset the disadvantage in economy. In contrast, comprehensive macro-policies come next, with a stronger actual distribution than the ideal distribution. The research findings further indicate that the FCEV industry has already been recognized at the strategic level, and its development still requires more policy support in terms of finance and taxation.

Based on the analysis results of AHP (ideal distribution) and CA (actual distribution), the deviations in 3 different types of policy instruments were analyzed, as shown in Fig. 6.

As shown in Fig. 6, demand-oriented policy instruments exhibited the largest deviation, with a weaker actual distribution than the ideal distribution. It is mainly because the applicable scenarios of FCEVs are yet to be explored, necessitating being guided by demand-oriented policy instruments. In contrast, environment-oriented ones come next, with a stronger actual distribution than the ideal distribution. The research findings further demonstrate that the key to the development of the FCEV industry is to identify suitable application scenarios, thereby driving large-scale development and technology validation through greater demand.

Based on the analysis results of AHP (ideal distribution) and CA (actual distribution), the deviations in 12 specific policy measures were analyzed, as shown in Fig. 7.

As shown in Figs. 4 and 7 of these 12 measures exhibit a stronger actual distribution than the ideal distribution. Among them, the policy strategy shows the highest deviation, indicating a significant excess of policy strategies. The remaining 8 measures have a weaker actual distribution than the ideal distribution, including the government procurement which shows the highest deviation (that is, a significant shortfall in government procurement), followed by the finance and taxation. The research findings further indicate that the public sector is a crucial breakthrough point for the development of the fuel cell vehicle industry.

Based on the analysis results of AHP (ideal distribution) and CA (actual distribution), the deviations in 48 policy paths were analyzed, as shown in Fig. 8.

As shown in Figs. 8 and 14 policy paths exhibit a stronger actual distribution than the ideal distribution, among which T3-Y1-Z1 has the largest deviation, indicating that the technical support measures in the supply-oriented policy instrument of S&T innovation policies are explicitly excessive. The remaining 34 policy paths exhibit a weaker actual distribution than the ideal distribution, among which T4-Y3-Z9 has the largest deviation, suggesting that the government procurement measures in the demand-oriented policy instrument of preferential fiscal and tax policies are obviously insufficient. Overall, the existing policy framework for FCEVs still shows significant deviation from the actual needs of industrial development. The low cost-effectiveness and lack of application scenarios for FCEVs are the main barriers. Fiscal and tax incentives, as well as applications in the public sector, are important pathways to address these issues.

Results of CA-industry chain analysis

Based on Formulas (13)–(14) and unit codes of national policies regarding FCEVs, a basic two-dimensional analysis framework of specific policy measures - industry chain was obtained through analysis, as shown in Fig. 9.

As shown in Fig. 9, specific policy measures for sales and other links account for the highest proportion (70.97%). This is in line with the focus of existing supporting policies that are mostly devoted to the purchase and use of vehicles. There were almost no national policies solely for the parts. This will be detrimental to the strengthening of the fuel cell vehicle industry chain.

Results of CA-value chain analysis

Based on Formulas (15)–(16) and unit codes of national policies regarding FCEVs, a basic two-dimensional analysis framework of specific policy measures -value chain was obtained through analysis, as shown in Fig. 10.

As shown in Fig. 10, the specific policy measures for consumption account for the highest proportion (61.29%). This is in line with the feature of China’s supporting policies. The specific policy measures for R&D come next (12.90%). The proportion of those for the investment, production, and use is relatively low. The emphasis on consumption over production in the value chain will be detrimental to the sustainable development of the fuel cell vehicle industry.

The results of this paper are substantially consistent with the trend of existing studies33,37,38,39. At the current stage, demand-oriented fiscal and tax preferential policies play the most important role in promoting the development of China’s FCEV industry, and the public sector is an important breakthrough point for the promotion of FCEVs. According to Buchanan’s research, quantitative assessment models have their limitations40. Although this study has fully incorporated expert experience in the process of policy quantification, it also acknowledges several limitations that require further investigation. It focuses on the research of FCEV policies and may overlook the impact of a broader range of hydrogen energy policies. According to the research by Huang et al., there are already over 100 national-level hydrogen energy policies25which may also have an impact on FCEVs. We did not take into account the regulatory documents of some policies. Moreover, the research methodology, particularly the policy categorization, needs to be validated for its applicability to other fields. In the future, research should be expanded to the hydrogen energy sector, focusing on establishing unified policy classification rules and investigating the impact of hydrogen energy policies on FCEV policies.

Conclusion and policy implications

This study sifted through China’s FCEV industry policies, and categorized them into four policy types, three policy instruments and 12 specific policy measures. Through policy modeling, a systematic and in-depth analysis was conducted on the typical national HFCEV industry policies, and the conclusions are given below.

(1) The important policies for China’s FCEV industry development were systematically sifted through, and divided into four categories based on the policy issuing departments, policy action links, policy impact mechanisms, namely comprehensive macro-policies, industry management policies, scientific and technological innovation policies and preferential fiscal and tax policies. In addition, based on CA, these four types of policies were further divided into three policy instruments and twelve specific policy measures. This lays the foundation for policy quantitative research, provides references for other scholars and facilitates comparisons across various studies.

(2) The policy quantitative analysis model established in this study can address previous challenges in multi-dimensional and quantitative evaluation of policies, and quickly identify problems of existing supporting policies based on actual industry development. It enables dynamic tracking of the actual distribution of policy types, policy instruments, and specific policy measures, allowing for comparisons with ideal distribution to offer insights for policy optimization. Furthermore, it can achieve real-time quantitative analysis of the industry chain and value chain.

(3) In terms of policy types, comprehensive macro-policies and scientific and technological innovation policies were introduced more frequently, while targeted preferential fiscal and tax policies were obviously insufficient (with a deviation of 0.29). In terms of policy instruments, supply-oriented and environment-oriented policy instrument were employed more frequently, while demand-oriented ones were obviously insufficient (with a deviation of 0.09). In terms of specific policy measures, policy strategies, technical support, public services, and regulatory control were used more frequently, while government procurement, finance and taxation, demonstration and promotion, publicity and science popularization, financial support, and S&T facilities were obviously insufficient. The talent introduction and overseas institutions were implemented relatively well. Analysis results show that focus is required for specific policy measures such as government procurement and finance and taxation, and that preferential fiscal and tax policies for demand-oriented policy instruments still need to be strengthened. This can solve the outstanding problems faced by China’s FCEV industry, such as high cost and unexplored applicable scenarios.

(4) In terms of the industry chain, sales and other links were supported by a high proportion of specific policy measures (up to 70.97%), while support for upstream links (such as parts, vehicles, and infrastructure) and service environment still needs to be strengthened. In terms of the value chain, national policies generally covered all links, with a variety of specific policy measures applied to the consumption link (accounting for 61.29%). However, the standards for R&D, production and use links still need further enhancement.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Huovila, A. et al. Carbon-neutral cities: critical review of theory and practice. J. Clean. Prod. 341, 1–18 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Carbon peak and carbon neutrality in china: goals, implementation path and prospects. CHINA Geol. 4, 720–746 (2021).

Zhang, H., Shen, R., Zhang, X., Kang, J. & Yuan, J. Implications and pathways of china’s carbon neutrality: a review. Progress Inquisitiones Mutat. Clim. 18, 240–252 (2022).

Ganiev, R. F., Ipatov, A. A., Romanov, A. N., Petrushov, V. A. & Moskvitin, G. V. Automobile and global warming. Automobile transport warms the planet more intensively than industry. J. Mach. Manuf. Reliab. 40, 303–312 (2011).

Ambrose, A. F., Al-Amin, A. Q., Rasiah, R. & Saidur, R. Amin, N. Prospects for introducing hydrogen fuel cell vehicles in Malaysia. Int. J. Hydrog Energy. 42, 9125–9134 (2017).

Kang, M. J. & Park, H. Impact of experience on government policy toward acceptance of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles in Korea. Energy Policy. 39, 3465–3475 (2011).

Nakui, K. An overview of the fuel cell and hydrogen technology development policies in Japan. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 39, 489–502 (2006).

Wang, J. Review of domestic and foreign fuel cell vehicle development policies. Sol. Energy 3, 8–10 (2013).

Zubaryeva, A. & Thiel, C. Analyzing potential lead markets for hydrogen fuel cell vehicles in europe: expert views and Spatial perspective. Int. J. Hydrog Energy. 38, 15878–15886 (2013).

Dai Yulong. Research on the Impact of Government Policy on New Energy Automobile Industry Based on AHP-Fuzzy Evaluation. (Beijing Univ. Posts Telecommunications, doi:https://doi.org/10.26969/d.cnki.gbydu.2023.002702. (2024).

Luo Yihan. The Incentive Effect of China’s New Energy Vehicle Industry Policy (Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, 2024).

Yadi, H. Research on the impact of new energy vehicles promotion policies on enterprise technological innovation:an empirical analysis based on the Difference-in-Differences method. Contemp. Econ. 42, 95–102 (2025).

AND ECONOMICS. Research on the Incentive Effect of Financial and Tax Preferential Policies on Innovation in the New Energy Vehicle Industry (YUNNAN UNIVERSITY OF FINANCE, 2025). https://doi.org/10.27455/d.cnki.gycmc.2024.000958

Xue, X., Fang, H. & Yang, Z. Research on the impact of new energy vehicle promotion policy on enterprise technological innovation:based on PSM-DID method. Sci. Sci. Manag. T. 42, 63–84 (2021).

Chen Yongguo, W. & Tianzun, H. Li guo. Quantitative evaluation of new energy vehicle policy text in Hebei Province based on PMC index model. Shanghai Energy Sav. 937–946. https://doi.org/10.13770/j.cnki.issn2095-705x.2023.07.009 (2023).

Yang Chengyuan. Research on Fiscal Subsidies and Tax Incentives New EnergyVehicles (Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, 2024).

Yang, C., Luo, R., Huang, J., Qi, H. & Tang, H. The impact of industrial policies on the technological innovation of new energy vehicle enterprises: an analysis of the LDA model based on policy texts. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 42, 114–126 (2025).

Zhou, Y. Yan linzhi. Quantitative evaluation of china’s new energy vehicle policy texts under the carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals. Soft Sci. 127–134 https://doi.org/10.13956/j.ss.1001-8409.2024.07.18 (2024).

Wang, J., Wang, X. & Chen, X. Research on the science technology resource management policy based on textual analysis: A case study of Hubei Province. Inf. Stud. Appl. 42, 82–86 (2019).

Xu, J. Evaluation on the Policy of New Energy Vehicle Industry from the Perspectives of Innovative Value Chain and Policy Tools (Zhejiang University of Finance & Economics, 2023). https://doi.org/10.27766/d.cnki.gzjcj.2022.000271

Wang, Z. Study on the tax policies to promote the development of china’s new energy vehicles Industry - Based on the perspective of industrial chain. (Central Univ. Finance Econ. https://doi.org/10.27665/d.cnki.gzcju.2022.001637 (2024).

Yu Hua. Research on fiscal policies to promote the development of china’s hydrogen energy industry. (Chinese Acad. Fiscal Sci. https://doi.org/10.26975/d.cnki.gccks.2023.000066 (2024).

Yao et al. Analysis on hot spots of hydrogen fuel cell policy,industry and technology development in China during the 14th Five-Year plan period. Shandong Chem. Ind 71–74 https://doi.org/10.19319/j.cnki.issn.1008-021x.2023.13.035

Wang Yidong, X., Suyu, H., Rui, T. H. & Weicheng, Y. Research and implication of china’s hydrogen energy and fuel cell industrial policies. Nat. Gas Ind. 44, 136–145 (2024).

Huang et al. Study on data mining of hydrogen energy policy in China based on natural Language processing technology. Bull Chin. Acad. Sci 1032–1046 https://doi.org/10.16418/j.issn.1000-3045.20230314001

Kong, C., Ma, N., Xing, X. & Han, M. Practical research on access management of hydrogen fuel cell vehicle manufacturing enterprises. Auto Ind. Res. 1–12 (2024).

Li, W. Analysis on the policy status of hydrogen fuel cell vehicle. China Storage Transp 149 https://doi.org/10.16301/j.cnki.cn12-1204/f.2023.10.111

Vargas, L. G. An overview of the analytic hierarchy process and its applications. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 48, 2–8 (1990).

Lipovetsky, S., Taylor & Francis Group. erstanding the Analytic Hierarchy Process: by Konrad Kulakowski, Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC, &, 262 pp., $130.00 (Hardback), ISBN 978-1-1380-3232-3. Technometrics 63, 278–279 (2021). (2021).

Ishizaka, A. & Labib, A. Review of the main developments in the analytic hierarchy process. Expert Syst. Appl. S0957417411006701 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2011.04.143 (2011).

Kleinheksel, A. J., Rockich-Winston, N., Tawfik, H. & Wyatt, T. R. Demystifying content analysis. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 84, 7113 (2020).

Lindgren, B. M., Lundman, B. & Graneheim, U. H. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 108, 103632 (2020).

Wang, J., Yao, Z., Fang, H. & Liu, B. Research on fuel cell vehicle policy system of China in Post-Subsidy era. Automot. Dig. 52–57 (2019).

Azizkhani, M., Vakili, A., Noorollahi, Y. & Naseri, F. Potential survey of photovoltaic power plants using analytical hierarchy process (AHP) method in Iran. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 75, 1198–1206 (2017).

Wu, X., Wang, Fan, S., Pu, X. & Jiao, Z. Comparative study on policies for promoting new energy automobiles in beijing, shanghai, and Guangzhou based on analysis hierarchy process. J. Shanghai Univ. 23, 973 (2017).

IBM & Downloading IBM SPSS statistics 26 (end of support 30-sep-2025). (2024). https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-26-end-support-30-sep-2025

Li, Y. & Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. The economic feasibility of green hydrogen and fuel cell electric vehicles for road transport in China. Energy Policy. 160, 112703 (2022).

Wang, M. The Study of the Fuel Cell Vehicle Industrv Policies in China (Zhejiang University, 2012).

Wu, Y., Liu, F., He, J., Wu, M. & Ke, Y. Obstacle identification, analysis and solutions of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles for application in China under the carbon neutrality target. Energy Policy. 159, 112643 (2021).

Buchanan, M. The limits of a model. Nat. Phys. 16, 605–605 (2020).

Funding

National Key Research and Development Program of China (Project No. 2023YFE0109300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All stated authors made significant contributions to this article. Z.D. designed the study, processed the data, performed statistical analysis and interpreted data as well as wrote the first draft. H.F. and L.S. processed the data, preformed statistical analysis and critically reviewed the manuscript. Z.Y. and J.W. designed the study, analyzed the data and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, reviewed and accepted the final version before publishing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, Z., Song, L., Fang, H. et al. A quantitative analysis on policies of China’s fuel cell electric vehicle industry. Sci Rep 15, 29713 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15196-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15196-1