Abstract

Graphene oxide is an ideal base for solid adsorbents to capture CO2. In this study, two materials, Clinoptilolite and Graphene oxide (GO), were used to prepare Clin@GO by autoclave at constant temperature and pressure. The response surface methodology based on the Box-Behnken design was applied to predict maximum adsorption capacity under optimum conditions. The highest adsorption capacity was 9 mmol/g achieved at 30 °C, 3.09 bar, and 0.25 g of adsorbent weight. The results of the isotherm study reveal that the Sips model has a high value of R2. The Elovich kinetic model can describe experimental data showing the adsorption process on heterogeneous surfaces. The thermodynamic study results proved that the CO2 adsorption process by Clin@GO is a physisorption and exothermic process. The mass transfer study disclosed that the mass transfer coefficient, diffusion coefficient, and mass flux values for CO2 molecules as a gas phase in the single-component system are 0.9249 m/s, 0.00082 m2/s, and 0.00042 mol/m s, respectively

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, burning fossil fuels in industry, electrical power, and transportation has increased toxic gas emissions. Toxic gas such as CO2, CO, NOx, and SOx creates many problems, including global warming, increasing sea levels, and destroying nature1,2. Among toxic gases, CO2 gas plays a significant role and has induced the main concern in the last century. In Fig. 1, the main sources of CO2 emission are presented. One of the main strategies for the elimination of CO2 is using solid adsorbents3. Selecting a suitable solid adsorbent is very important because an adsorbent should have high thermal stability, availability, high activity, high chemical stability, and low cost4.

Clinoptilolite is known as a natural zeolite5 with the general chemical formula Na6[(AlO2)6(SiO2)30]⋅24H2O with a ratio between Si/Al is varying between 4.0 and 5.36. Clinoptilolite has two advantages such as low price and availability. The mentioned advantages cause it to be used in different fields like catalyst7, agriculture8, and solid adsorbent9. Davarpanah and coworkers used low-cost clinoptilolite for CO2 capture from industrial processes. Arefi Pour et al.10 reported CO2 separation from the CO2/CH4 mixture by Clinoptilolite as an adsorbent. Armenta et al.11 reported the adsorption kinetics of CH4, CO2, N2, and O2 by clinoptilolite. However, the surface area of raw Clinoptilolite is very low, and this problem affects the efficiency of the solid adsorbent. To solve this problem, graphene oxide was used. Graphene oxide (GO) with a two-dimensional planar structure containing sp2 carbon atoms adequately has unique properties like thermal stability, electronic conductivity, and high specific surface area12,13. GO has oxygenated functional groups, hydroxyl and epoxide groups on their basal plants, and carboxyl and carbonyl groups in their edge14. Helmi et al.15 used KOH@GO-Fe3O4 as a magnetic solid adsorbent for CO2 capture with the highest capacity of 3.21 mmol at 25 °C and 9 bar. Zhou et al.16 prepared graphene oxide/methyl diethanolamine nano-fluids as solid adsorbents for the CO2 capture. The maximum adsorption capacity. Shang and coworkers17 designed CuBTC and its graphene oxide (CuBTC@GO) composites as adsorbents for CO2 capture. The highest CO2 adsorption capacity was 8.02 mml/g at 173 K and 1 bar. Chowdhury et al.18 prepared titanium dioxide/graphene oxide (TiO2/GO) as a mesoporous nano-composite for CO2 adsorption. The maximum CO2 at adsorption was obtained at 1.88 mmol/g at 25 °C and 1 bar. The CO2 adsorption process is affected by different independent variables, including pH, time, pressure, temperature, and adsorption dosage. The usual method for optimizing the process is the one-variable method; however, it overlooks the result of the interaction between two variables. The response surface methodology (RSM) is a mathematical/statistical technique first suggested by Box and Wilson to correct, analyze, optimize, and model several processes. This method aims to optimize the independent reaction variables by applying the statistical tool as RSM while the cost of the CO2 capture process decreases. As well as the use of statistical method-based experimental results could assist in studying the result of independent variables or the interaction of both dependent and independent variables on the response. The Clinoptilolite@Graphene oxide (Clin@GO) was synthesized and applied for CO2 capture in this research. The physical and chemical properties of adsorbents such as morphology, surface area, and thermal resistance were identified by FESEM, BET, TGA, FTIR, and XRD. The response surface methodology based on the Box-Behnken design (RSM-BBD) was used to optimize independent factors, including pressure, temperature, adsorbent weight, and composite type. The mass transfer coefficient, mass flux, and diffusion coefficient for CO2 were calculated by mass transfer equations. The type of adsorption process was determined using thermodynamic calculation.

Materials and methods

Materials

Clinoptilolite was purchased from Negin powder Semnan Company. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%), Nitric acid (HNO3, 65%), Sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%), Potassium chloride (KClO3, 90%), and graphite powder were purchased from Merck Company.

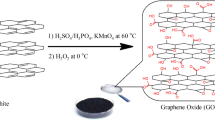

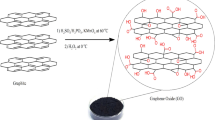

Synthesis of graphene oxide

This study prepared GO according to the modified Hummers and Offeman method19. At first, graphite powder (1 g) was added to a mixture of H2SO4 and HNO3 (2:1 in volume) and mixed for 1 h. Then, KClO3 (11 g) was added to the mixture for 2 h. The prepared mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 72 h. Next, the oxidation suspension was washed with HCl (5 wt%) to eliminate residual and washed with deionized water until pH reached 7. Finally, the prepared sample was dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C overnight.

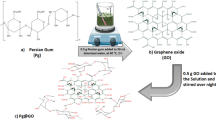

Prepared Clin@GO

Clinoptilolite and GO were sonicated in deionized water and methanol (100 mL) for 30 min. Then, they are mixed and sonicated for 1 h. The prepared mixture was put into the Autoclave (300 ml) and heated at 200 °C overnight. As GO has a sensitive structure due to oxygenated functional groups, the materials are heated in the Autoclave at constant pressure. Ultimately, the prepared sample was dried in an oven at 60 °C overnight. In Fig. 2, the procedure of Clin@GO synthesis is presented. The total amount of material produced in each batch was approximately 1.5 g, resulting in a final product yield of around 75% after the autoclaving process

Characterization of adsorbent

In this study, the characterization of raw Persian gum, GO, and Clin@GO as biodegradable solid adsorbents was studied by different analyses. X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD, Bruker, 2θ = 5–80°) as a non-destructive method provides details about chemical compositions, crystallographic structure, and physical characterization of materials20. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Thermo, Avatar) investigates the type of bond mechanism in materials and their surface. It also showed the molecular bonding on the surface or in the solid phase21. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Philips XL30 ESEM) was used to determine the surface morphology of the adsorbent. The thermal stability of compounds and their fraction of volatile were measured by thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA, TA, Q600, USA). In this technique, the weight change of the sample was observed when the sample was heated at a constant rate22.

CO2 capture process

Figure 3 shows the laboratory-scale reactor. It was used to carry out the CO2 adsorption process. It consisted of four main components: Gas injection, reactor system, CO2 pressure control instrument, and a thermocouple for heat monitoring. Each experiment involved using 0.1–0.5 g of solid adsorbent and injecting CO2 gas from a high-purity capsule into the chamber. As the adsorption process proceeded, the pressure in the chamber decreased due to CO2 adsorption, while the chamber and reactor volume remained unchanged. The amount of CO2 adsorbed was determined by measuring the reduction in pressure.

CO2 adsorption in laboratory-scale reactor15.

The value of adsorbed CO2 can be measured by eq.1, based on the value of pressure reduction via an equation related to the adoption equation. Equation (2) helped to measure the value of CO2 adsorbed23:

In above equations, pi, pf and are w initial, final pressure in reactor, and weight of adsorbent, respectively. Equation (3) assist to determine the adsorption capacity of Clin@GO:

where T is temperature, V is the volume of reactor, R is gas constant, and MCO2 is molecular weight of CO2. The compressibility factor was measured using the Virial equation of State, which is equal to the Cutoff coefficient: Eq. (4). The Tsonopoulos equations were able to achieve a virial coefficient as described in Eqs. (5–7).

where B, Pc, Tc and TR are the second coefficient of virial, critical pressure, critical temperature and reduced temperature, respectively.

Response surface methodology

To optimize the reaction condition of the CO2 adsorption process and achieve the highest CO2 adsorption capacity, response surface methodology based on Box-Behnken design (RSM-BBD) was used. Three independent reaction conditions including pressure (A), adsorbent weight (B), and temperature (C) were selected to optimize the CO2 capture process. CO2 capacity was chosen as the response (Y). Table 1 shows the lower and upper levels, coded and un-coded of each independent variable. Seventeen experiments were considered with four reflections performed at the center points to investigate the pure error24. The complete design matrix achieved from BBD for actual results was displayed in the Table 1. A second-order polynomial equation model was used to suggest optimal level of each independent variables and response (Eq. 8);

where Y and k are the response and the number of experimental data, respectively. The factors of α0 are constant coefficients, αi are linear coefficients and αij is the second-order interaction coefficient. Both signs Ki and kj illustrate the codded of independent factors, and ε is random error25. The adjusted R-squared and R squared are calculated by Eqs. (9) and (10), respectively26.

Mass transfer calculation

In the adsorption process, the moving of gal molecules both onto and into the solid absorption affects separation speed. Generally, four steps are conveyed for the adsorption process; (a) locomotion of gas molecules from the gas phase to the outer layer of adsorbent, (b) Shift of gas molecules across the outer layer of solid adsorbent, (c) shift of molecules into adsorbent pores, (d) penetration of gas molecules in the internal channels of solid adsorbent27,28. Universally, steps (2) and (3) are eliminated in the adsorption process because the rate of mass transfer is low. Commonly, to calculate numerical mass transfer coefficient, differential equations are used based on empirical results29. As mentioned above, mass transfer means moving from one point to another point or phase because different concentrations that are created between two points cause this phenomenon. The mass transfer continues until the system reaches equilibrium as well. If the mass transfer has high speed, the system will reach to equilibrium soon. In other words, the system has a high mass transfer coefficient, and contact time between two phases is low. The Clin@GO has meso-sized pores. The accessibility of nano-pores influences mass exchange and upgrades it. It implies that the participation of nanoparticles conduces to enhancement within the mass exchange coefficient. Moreover, in adsorbents with nano-sized pores, intermolecular powers have a better impact than hydrodynamic powers. Subsequently, it is attempted to apply the required equation around the presumptions for accomplishing the mass exchange coefficient and flux30. The essential assumptions for investigating the mass transfer towards Clin@GO are mentioned following; (1) Clin@GO has solid states (2) it has spherical cavities based on FESEM images, (c) the adsorption condition is non-uniform, (d) CO2 molecules transferred to pores, (e) the mechanism of transfer within the cavities of sphere will be molecular diffusion because rigidity of the sphere causes the internal movement of the sphere can be eliminated31. By considering all the said doubts, the mass trade insides state pores in a nun-uniform state got to be inspected. Mass trade interior circular solid materials having pores rises underneath non-uniform conditions. Routinely, catalytic solids are porous, and heterogeneous reactions happen interior them. The concentration of CO2 gas in each step is calculated by the ideal gas formula (Eq. 11). The mass flux and the mass transfer coefficient are calculated by Eqs. (12) and (13).

Making a precise prediction about the diffusion coefficient in solid adsorbents is a noteworthy accomplishment, requiring a comprehensive analysis of various factors, such as the structure of the solid, the interaction between the solid and solute, and the efficiency of the transfer element or solute penetration. CO2 molecules can penetrate through different mechanisms, including movement component penetration through interatomic spaces, atom shift, and atom leaping into empty spaces. Solid adsorbents like Clin@GO have pores that enable molecular diffusion based on concentration differences in gas. During the adsorption process, gas molecules are restricted by the solid, and mass transfer mechanisms occur through penetration from either gas to solid surface or solid surface to gas. Nevertheless, in certain cases, the actual penetration value may be less than the theoretical value, resulting in the use of an effective diffusion coefficient instead of the normal diffusion coefficient. The molecular structure and internal geometry of the solid directly impact this parameter. Figure 4 illustrated the main steps of the adsorption mechanism by each solid adsorbent including (1) inter-particle forwarding, (2) inter-phase mass transfer, (3) intra-phase particle distribution, (4) surface reaction and equilibria. Masoumi et al.32 showed the efficient diffusion coefficient is calculated as follows:

Common mechanism of adsorption33.

Results and discussions

Characterization of Clin@GO

FTIR spectrum of raw clinoptilolite, pure GO, and Clin@GO as adsorbent are shown in Figure 5. Raw Clinoptilolite has a board characterization peak at 3464 cm−1 which is related to –OH stretching vibration. The peak at 1637 cm−1 is corresponding to the binding vibration of hydroxyl groups on the Clinoptilolite surface. Both generic asymmetric vibration of Si–O–Si and stretching vibration of Si–O groups have peaks at 1064 cm−1 and 792 cm−1, respectively. The binding vibration of Si–O–Si and Si–O–Al have peaks at 605 cm−1 and 473 cm−1, respectively. These peaks are pieces of evidence that prove silicon and aluminum are available in the Clinoptilolite surface. Similar results are reported in other references34,35,36. According to the FTIR spectrum of Pure GO, the board peak appeared at 3427 cm−1 which showed stretching vibration of –OH groups. The two peaks at 1620 cm−1 and 1715 cm−1 related to the skeleton vibration of C=C and C=O stretching vibration, respectively. The peak at 1300 cm−1 is corresponding to the C–O–C groups. The epoxy groups (C–O) have a peak at 1055 cm−137,38. The Clin@GO has similar characterization peaks with both raw Clinoptilolite and GO which proves synthesis of Clin@GO was successful without destruction in the structure them.

The crystal structure of pure GO, Clinoptilolite, and Clin@GO were determined and evaluated by XRD analysis. As can be observed in Fig. 6, Clinoptilolite had main peaks at 2θ = 10.01, 11.28, 17.48, 21.87, 22.54, 26.99, 30.29, 32.18, and 37.11°. These peaks confirmed the crystalline structure of Clinoptilolite, these peaks have good agreement with the XRD pattern of JCDBS 38–023739. The crystal phase of GO has a sharp peak at 2θ = 11.39° with a d-spacing of 2.15 Ă40. After synthesis of Clin@GO, the characterization peaks were observed at 2θ = 9.82, 11.12, 17.03, 22.34, 30.03, and 31.92, 32.03, and 36.54°. These peaks are similar to both GO and Clinoptilolite peaks. Nonetheless, the Clinoptilolite structure was changed after the synthesis of the composite and their peaks became weaker or removed. The peak at 2θ = 9.82° confirmed the presence of GO in Clin@GO while the intensity of this peak is lower than raw GO.

The morphology structure of raw clinoptilolite, raw GO, and Clin@GO were studied by FESEM analysis. Figure 7a shows the morphology of raw clinoptilolite. The spherical and agglomerate structures of Clinoptilolite were observed clearly. It has a layered structure as well41,42. The smooth and wrinkled surface of GO was observed in Fig. 7b. The oxygenated functional groups of GO cause a tulle-like structure43. After the synthesis of Clin@GO, the structure of GO was rougher and the agglomerate particles of clinoptilolite were observed on the GO surface (Fig. 7c).

TGA analysis is an inexpensive, fast, and easy method to determine the composition of materials44. The Clin@GO was heated from 25 to 700 °C at a scan rate of 5 °C. Based on Figure 8, the sample had 5 wt% weight loss due to weight loss at 100–140 °C. The second step begins at about 200 °C of 27 wt% and is related to structural water because of hydration complexes formed with exchangeable cations45. By increasing the temperature above 300 °C dihydroxylation process was observed. In this process, the water molecules that are polarized in zeolite cavities are released45. TGA results have a good agreement with another report45.

The surface area (SBET), pore volume (Vp) and average pore diameter (nm) of Clin@GO were calculated by BET analysis. The BET results showed in Fig. 9. The average pore diameter of Clin@GO has been 0.354 nm. According to the BET results, SBET and Vp of adsorbent were 2.18 m2/g and 0.501 cm3/g, respectively. Based on the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) classification, macro-porous materials have pore diameter with 50–1000 nm, micro-porous materials have pore diameter with 2–50 nm, and nano-porous material possess pore diameter with 0.2–2 nm. Therefore, Clin@GO has micro structure. The surfaces area of an adsorbent is a critical factor influencing its adsorption capacity.

It is very important to know higher surface areas typically provide more active sites for CO2 molecules to interact with the adsorbent. If different synthesis batches result in varying surface areas, this could lead to inconsistent performance in terms of CO2 capture efficiency. Not only is the total surface area important, but the pore size distribution and connectivity also play significant roles in adsorption performance. Variations in these parameters across different synthesis batches can affect how easily CO2 molecules can access the active sites within the Clin@GO composite. In addition, Variations in the chemical composition of the clinoptilolite or the degree of functionalization with graphene oxide could also affect performance. Functional groups introduced during synthesis can enhance CO2 adsorption through specific interactions, and inconsistencies in their presence or distribution may lead to variability in performance.

Mechanism of adsorption

The type of mechanism for CO2 adsorption via Cli@GO is physisorption at 30 °C (Figure 10). in the first step, CO2 molecules adsorbed on primary adsorption alkali sites like Mg2+, Ca2+, and Na+ sites of Clinoptilolite and the cage windows sites. As in the latter sites, the weak interaction including van der Waals forces between CO2 molecules and active sites has happened, CO2 molecules are preferentially adsorbed in O=C=O…Clin@GO configuration46. The weak van der Waals interaction causes a good reversibility sorption mechanism. The interaction between open metal ions and CO2 molecules is electrostatic and is stronger than van der Waals47. Both two interactions are affected by temperature and they showed good performance at low temperatures. Sudeep et al.48 reported that the slight chemical interaction between carbonyl functional groups of Clin@GO and CO2 molecules was observed. For Clinoptilolite, the cation distribution and coordination of adsorbent has a significant effect on CO2 adsorption and diffusion because of its extra framework cations49.

RSM analysis

In this study, the relation between independent parameters and response (adsorption capacity) was determined. The empirical results of each run are shown in Table 2. The empirical sequence was randomized to decrease the impacts of the uncontrolled parameters24. RSM-BBD suggests a mathematical equation (eq.19) where response (Y) is adsorption capacity. The negative and positive sign of each parameter illustrates the increasing and decreasing impacts of the response factor. Coded equation was used to determine the relative impact of factors by comparing the coefficient of the parameters50. Independent parameters including pressure (A), temperature (b), and adsorbent weight (C)

All experimental results were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) to estimate goodness fit. Each corresponding significant model term and significant quadratic model are illustrated in Table 3. The coefficient of determination (R2) is used to study the accuracy of the quadratic polynomial model and the F-test is applied to check the statistical significance of the model51. The values of R2 adjusted determination coefficient (adj-R2) were 0.9949 and 0.9883, respectively. The quadratic polynomial model had acceptable results when ANOVA analysis supplies a 95% confidence level with considering P value lower than 0.05. Therefore, the P value of A, B, C, AB, AC, BC, A2, B2, and C2 is less than 0.05 to show the significance of these terms on the model. If a term has a larger F-value and lower P value, it has a significant effect on the model52. Based on the largest F-value, temperature (F = 494.77), the interaction between temperature and catalyst weight (F = 297.89), adsorbent weight-square (F = 177.90), and pressure (F = 119.24) have priority among independent factors. In the mathematical model lack of fit is not-significant which means the interaction between response and parameters is covered and the model is fit for empirical results53. The ability of the model to predict the values of responses is measured by predicted R-square (pre-R2) and it should have good agreement with adjusted-R2. In this model, Pre-R2 is 0.9729. Therefore, the difference between pre-R2 and adj-R2 is less than 0.2. The signal-to-noise ratio is determined by adequate precision. If the ratio of adequate precision is more than four, the model is desirable. In this mathematical model, the ratio of 43.011 shows the sufficient fit of the model. The value of the coefficient of the variation (CV%) is 2.13 showing a high degree of precision and a good deal of reliability of the empirical data54.

Figure 11a shows predicted values against actual values. The predicted values are distributed normally in a straight line near to actual values. Therefore, it has proven that the produced regression model can show the relationship between adsorption capacity as a response and independent parameters55. The normal plot of residuals is shown in Fig. 11b. In the first step, the residuals are normalized by considering their studentized (standard deviation), next normal distribution function with studentized. Then, the studentized residual foresaw via the best-fit normal distribution and finally was schemed versus the empirically achieved studentized residual. As the straight line observed in Fig. 11b, the studentized residuals follow a normal distribution56. On the other hand, In this plot, if residuals do not have a normal distribution, or have an S-shape curve, it will show that the model was incorrect57.

The outlier t plot for all runs of CO2 adsorption is illustrated in Fig. 11c. This plot depicts the distinction of the residuals for each run to determine the runs that had individually mighty residuals2. Generally, to illustrate the positional and operational error for the model and actual data, most of the residuals should be in the interval between ± 4.81. In this model, all data is put in the interval.

Figure 11d shows residuals vs. predicted plots. This plot should display a random distribution for each run that proves the change in observation is not related to the values of responses25. The natural log of the sum of squares vs. lambda is shown in Fig. 11e. Using this plot assists in finding the correct value of lambda. The power transformation means that lambda displays the increased power via the response to do the transformation. The current transformation of − 1.31 is chosen as the best possible transformation58.

The effect of independent parameters on CO 2 adsorption

The contour plots of interaction parameters versus CO2 adsorption as a response that shown in Figure 12. In each plot, two remaining parameters are set fixed at their center. Figure 12a, c show the effect of pressure on the CO2 capture process. Based on the plot results, by increasing pressure to 3.09 bar the adsorption capacity raised to 9 mmol/g because CO2 molecules penetrate pores of Clin@GO as a solid adsorbent due to increasing CO2 adsorption50. The effect of temperature as an independent parameter is shown in Fig. 12a, b. In both plots, increasing temperature hurts CO2 adsorption. Taheri et al reported59,60 that as the physical adsorption process is exothermic, therefore, in high temperatures, the interaction between CO2 molecules in the gas phase and solid surface increases. Based on the Boltzmann equation, increasing the kinetic energy of molecules in both solid and gas phases induces increasing molecule interaction and decreases the accessible surface of adsorbents for CO2 capture. Consequently, the highest adsorption capacity is achieved at the lowest temperature. Therefore, 30 °C was selected as an optimum temperature. The results of isotherm models shown in Fig. 13 confirm this reason.

Figure 12b, c illustrate the effect of adsorbent weight on CO2 capture. By increasing adsorbent weight to 0.25 g to highest adsorption capacity is 9.00 mmol/g. That is because the positive interaction between active sites of Clin@GO and CO2 molecules enhanced and CO2 capacity significantly increased23. On the other hand, increasing adsorbent weight by more than 0.25 g caused the adsorption capacity to decrease because when active sites increase more than the optimum situation, the adequate space for interaction between CO2 molecules and active sites of adsorbents is not available59. Therefore, the CO2 adsorption capacity significantly decreases. Hence, the optimum adsorption weight was chosen 0.25 g.

Optimization reaction

One of the main goals of using RSM-BBD is the optimization of reaction conditions while the highest adsorption capacity is achieved according to the combination of parameters23. The favorable values of each parameter and response are able to be selected based on the RSM numerical optimization. In this modeling method, six various options such as target, range, minimum, maximum, and none only for response) put a final response is available. In this study, the response was set to maximum while input parameters were proposed to calculate in-range values. According to the procedure, the optimal conditions for independent parameters are a pressure of 3.00 bar, a temperature of 30 °C, 0.25 wt% of adsorbent weight, and the maximum adsorption capacity of solid adsorbent was 9.00 mmol/g.

GaO et al.61 used Zn/Mg-MOF-74 as a solid adsorbent for CO2 capture. They achieved highest adsorption capacity of 2.9 mmol/g at 273 K and 1 bar. Esfehani et al used MOF-NH2/GO for CO2 capture. They obtained the highest adsorption capacity of 6.9 mmol/g at 25 °C and 9 bar. Khoshraftar et al62 reported using monoethanolamine (MEA)-carbon active for CO2 adsorption. The maximum adsorption capacity was achieved 0.609 mol/L at 30 °C, pressure of 5.19 bar. Ghaemi et al50 used Carbon molecular sieves (CMS) for CO2 adsorption. The highest adsorption capacity was 1.29 mmol/g at 20 °C and 10.011 bar.

Raw Clinoptilolite was applied as a solid adsorbent for CO2 capture Davarpanah et al 49. They achieved the maximum adsorption capacity of 06 mmol/g at 338 K due to availability of Ca2+ and Na+ in raw clinoptilolite structure. Arango Hoyos et al.49 used raw graphene oxide for CO2 capture process. They reported that raw GO has low capacity for CO2 capture. Hence, Synthesizing GO@Clino caused solid adsorbent has both oxygenated groups from GO and alkali cationic groups like Ca2+ and Na+ in CO2 capture process due to the positive effect on this process.

Mass transfer results

To degree mass exchange parameters, the vital constants for calculating the mass exchange coefficient are recorded within the Table 4. Within the single framework, the sing “A” outlined CO2 particles with a starting concentration of 0.015 mg/L, after 20 min, the framework came to balance circumstance and the concentration of CO2 was 0.0143 mg/L. Based on the Wagered investigation comes about, the cruel pore distance across Clin@GO was 0.177 nm which put the strong adsorbent within the micro-category. Conditions (2) to (4) were utilized to calculate mass flux. Moving CO2 molecules from a gas state to a solid state alters the concentration at the boundary and leads to changes in pressure between the two states, resulting in changes in mass transfer. As time passed, the solid adsorbent’s spheres and pores became filled with CO2 molecules, causing a decrease in the available spaces for gas molecules to gather. Consequently, the effective diffusion coefficient decreased over time, but the flux increased as the surface area needed for CO2 adsorption decreased, enhancing the mass transfer flux. The mass transfer calculations for CO2 capture by Clin@GO was presented in Table 5.

Isotherm modeling

To determine the adsorption mechanism and detect the role of each adsorbate and adsorbent, an isotherm study was performed63. Adsorption performance will be predicted and compared using modeling of adsorption data. Isotherm models assist in optimizing the adsorption mechanism pathways as well. To design of sorption system, investigating equilibrium sorption is necessary. While the equilibrium is required between sorbent and sorbet, sorption isotherm should be evaluated at a constant temperature at different pressures64. Two important parameters to predict CO2 adsorption are the isotherm constant and the corresponding R2-value achieved from non-linear regression65. In this project, the results of the isotherm study are shown in the Table 6 and Fig. 13. According to Table 6, the Sips model had a higher R2 value and a good fit with empirical data. Sips isotherm model is formed due to a combination of both Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models. It can predict the heterogeneity of the adsorption systems in high-concentration66.

Kinetic modeling

The adsorption rate and mechanism are determined by kinetic models. They calculate the potential rate of controlling steps as well67. In this study, four kinetic models are listed in the Table 7 and Fig. 14 including first order, second order, Ritchie Second, and Elovich models at 25 °C, 45 °C, and 65 °C at 5 bar. The first-order kinetic model is observed when CO2 adsorption happens within a layer by diffusion. When chemical adsorption controls reaction with a slow rate, the second-order kinetic model is seen68. If the kinetic study follows Ritchie’s second-order model, CO2 molecules adsorb on two sites69. The Elovich kinetic model appears in two situations. First, in the chemical adsorption of CO2 molecules in the gas phase on the solid phase. Second, adsorb of materials on the liquid phase70,71. If the model has a high correlation coefficient (R2), it will be well-fitted with empirical results. Therefore, based on the R2, the Elovich model is able to explain empirical data better than other kinetic models. The R2 of this model is 0.9892. The factor α or initial adsorption rate strongly depends on temperature and it explains the adsorption process on active sites of heterogeneous surface72. As Clin@GO as a solid adsorbent doesn’t uniform surface, and the active sites of the adsorbent are not uniform during the adsorption process, the CO2 adsorption mechanism is heterogeneous adsorption.

Thermodynamic modeling

The nature of the interaction between adsorbent and adsorbate, either physical or chemical, is determined by thermodynamic parameters. The key parameter for evaluating spontaneous adsorption is the standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG0). Other thermodynamic parameters are enthalpy (ΔH0) and entropy (ΔS0) that are achieved from the slope (ΔH0/R) and intercept (ΔS0/R) elevation of the Ln (Kd) against inverse temperature (1/T)73 or Eq. (21). The value of ΔG0 is determined by Eq. (22) as well. The Kd is thermodynamic equilibrium constant that achieved from Eq. (20):

where initial and final conditions are defined by f and i. volume of reactor, pressure, and the adsorbent weight are shown with V, W, and P. When the transfer of electrons is observed between adsorbent and adsorbate, the chemisorption with strong chemical bonding has happened. In contrast, the weak bonds such as van der Waals causes physisorption arises74. Regarding the sign of ΔS0, if ΔS0 has a negative sign (ΔS0<0), the adsorption process is less random. Controversy, if ΔS0 has a positive sign, the CO2 capture process is more random. The exothermic and endothermic CO2 adsorption process is measured by the negative or positive signs of ΔH0, respectively. When the reaction is exothermic, the adsorbed energy causes bonds to be broken and energy in the form of heat released to its surroundings because the value of the total energy released in bond-making between CO2 molecules and the surface of the sorbent is more than the total energy absorbed in bond breaking. In contrast, the positive value of ΔH0 illustrates CO2 adsorption process adsorbs energy in the form of heat from its surrounding75. Besides the negative or positive signs of ΔH0, for physisorption, absolute ΔH0 is less than 20 kJ/mol−1. However, for chemisorption absolute ΔH0 is more than 40 kJ/mol−1. Based on Fig. 15 and Table 8, the value of ΔG0 was negative which indicated the CO2 adsorption process by Clin@GO was favorable and spontaneous at 25 °C, 45 °C, and 65 °C. Besides that, by investigating the van’t Hoff plot, decreasing temperatures causes ΔG0 becomes more negative. That is because, as the value of ΔH0 was − 11.441 kJ/mol−1, the CO2 adsorption process by Clin@GO was physisorption and exothermic. In other words, since new physical bonds are formed, energy is seen as heat produced into its surroundings during adsorption. Therefore, with increasing temperatures, physical bonds between adsorbate and adsorbent are weak, and a reversed reaction happens.

Regeneration of adsorbent

The regenerability and chemical stability of Clin@GO as a solid adsorbent were a key factor in the efficacy and capacity of the CO2 adsorption process. Changing temperatures and pressures can be induced on the regeneration of solid adsorbents. Three main methods are used for recycling Clin@GO. If the regeneration process happens by changing temperatures, temperature swing adsorption (TSA) methods are applied. By changing pressure, pressure/vacuum swing adsorption (PSA/VSA) is used. By combining two methods or changing both temperatures and pressures, a hybrid regeneration mode (VTSA/PTSA) is performed76. In this study, the TSA method was used for the regeneration of Clin@GO. Figure 16 shows the regeneration cycles of solid adsorbent. According to Fig. 16, Clin@GO was recycled eight times at 30 °C, 3 bar, and 0.25 wt% of solid adsorbent. After each cycle, to remove CO2, Clin@GO was heated at 100 °C. The thermal stability of solid adsorbent and its gradual degradation caused the chemical structure of the adsorbent not to destroy during the TSA method, therefore, CO2 adsorption capacity decreased from 9.00 mmol/g in the initial cycle to 7.5 mmol/g in the last cycle. All in all, Clin@GO is able to use in industrial applications because of its high adsorption capacity, low cost, and regenerability.

Conclusion

In this study, Clin@GO has been prepared as a novel solid adsorbent for CO2 capture. Crystalline structure, surface area, morphology, there stability of the adsorbent was characterized by different instrumental techniques. Based on the analysis results, Clin@GO was successfully synthesized without destroying the GO structure. According to the BET analysis results, as the solid adsorbent has a pore diameter of 0.354 nm, it is classified in the nanopores category. The optimization of the CO2 capture process via Clin@GO was performed by RSM-BBD. The highest CO2 capture capacity was 9.00 mmol/g under optimum conditions of pressure 3 bar, temperature 30 °C, and 0.25 wt% of adsorbent. High values of R2, pre-R2, and adj-R2 demonstrated that the suggested mathematical model by RSM has enough accuracy to estimate the model response. The solid adsorbent regenerated 8 times under optimum conditions and the lowest CO2 adsorption capacity was 7.5 mmol/g. Based on the isotherm and kinetic studies, Sips and Elovich models were well-fitted with empirical data, respectively. The thermodynamic study revealed that the values of ΔH0, ΔS0, and ΔG0 were − 11.441, 0.011, and − 8.1687, respectively. The negative value of ΔG0 illustrated the CO2 capture process by Clin@GO was exothermic and spontaneous. In the single-component system, the mass transfer coefficient, diffusion coefficient, and mass flux values for CO2 molecules in the single-component system are 0.9249 m/s, 0.00082 m2/s, and 0.00042 mol/m s, respectively.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Helmi, M. et al. Synthesis, characterization and performance evaluation of NaOH@Chitosan-Fe3O4 as an adsorbent for CO2 capture. Fuel 338, 127300 (2023).

Helmi, M. et al. Phosphomolybdic acid/graphene oxide as novel green catalyst using for biodiesel production from waste cooking oil via electrolysis method: Optimization using with response surface methodology (RSM). Fuel 287, 119528 (2020).

Ghanbari, T., Abnisa, F. & Daud, W. M. A review on production of metal organic frameworks (MOF) for CO2 adsorption. Sci. Total Environ. 707, 135090 (2020).

Yu, C.-H., Huang, C.-H. & Tan, C.-S. A review of CO2 capture by absorption and adsorption. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 12(5), 745–769 (2012).

Helmi, M. et al. Biodiesel synthesis using clinoptilolite-Fe3O4-based phosphomolybdic acid as a novel magnetic green catalyst from salvia mirzayanii oil via electrolysis method: Optimization study by Taguchi method. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9(5), 105988 (2021).

Helmi, M., Hemmati, A. & Tahvildari, K. Production of biodiesel from Salvia mirzayanii oil via electrolysis using KOH/Clinoptilolite as catalyst. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 20, 187–204 (2022).

Helmi, M. et al. Converting waste cooking oil into biodiesel using phosphomolybdic acid/clinoptilolite as an innovative green catalyst via electrolysis procedure; optimization by response surface methodology (RSM). Fuel Process. Technol. 225, 107062 (2022).

Polat, E. et al. Use of natural zeolite (clinoptilolite) in agriculture. J. Fruit Ornam. Plant Res. 12(1), 183–189 (2004).

Hedström, A. & Rastas Amofah, L. Adsorption and desorption of ammonium by clinoptilolite adsorbent in municipal wastewater treatment systems. J. Environ. Eng. Sci. 7(1), 53–61 (2008).

Arefi Pour, A. et al. Performance evaluation of clinoptilolite and 13X zeolites in CO2 separation from CO2/CH4 mixture. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 26, 1246–1253 (2015).

Aguilar-Armenta, G. et al. Adsorption Kinetics of CO2, O2, N2, and CH4 in cation-exchanged clinoptilolite. J. Phys. Chem. B 105(7), 1313–1319 (2001).

Dizaji, A. K., Mokhtarani, B. & Mortaheb, H. R. Deep and fast oxidative desulfurization of fuels using graphene oxide-based phosphotungstic acid catalysts. Fuel 236, 717–729 (2019).

Dizaji, A. K., Mortaheb, H. R. & Mokhtarani, B. Complete oxidative desulfurization using graphene oxide-based phosphomolybdic acid catalyst: Process optimization by two phase mass balance approach. Chem. Eng. J. 335, 362–372 (2018).

Cheraghi, S. et al. Novel enzymatic graphene oxide based biosensor for the detection of glutathione in biological body fluids. Chemosphere 287, 132187 (2022).

Helmi, M. et al. Synthesis and characterization of KOH@Graphene oxide-Fe3O4 as a magnetic composite adsorbent for CO2 capture. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 178, 111338 (2023).

Zhou, Z., Davoudi, E. & Vaferi, B. Monitoring the effect of surface functionalization on the CO2 capture by graphene oxide/methyl diethanolamine nanofluids. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9(5), 106202 (2021).

Shang, S. et al. Facile synthesis of CuBTC and its graphene oxide composites as efficient adsorbents for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. J. 393, 124666 (2020).

Chowdhury, S., Parshetti, G. K. & Balasubramanian, R. Post-combustion CO2 capture using mesoporous TiO2/graphene oxide nanocomposites. Chem. Eng. J. 263, 374–384 (2015).

Wang, H. et al. Facile synthesis of polypyrrole decorated reduced graphene oxide–Fe3O4 magnetic composites and its application for the Cr(VI) removal. Chem. Eng. J. 262, 597–606 (2015).

Raja, P. B. et al. 5—Characterization of nanomaterial used in nanobioremediation. In Nano-Bioremediation: Fundamentals and Applications (eds Iqbal, H. M. N. et al.) 57–83 (Elsevier, 2022).

Peak, D. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. In Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment (ed. Hillel, D.) 80–85 (Elsevier, 2005).

Rajisha, K. R. et al. 9—Thermomechanical and spectroscopic characterization of natural fibre composites. In Interface Engineering of Natural Fibre Composites for Maximum Performance (ed. Zafeiropoulos, N. E.) 241–274 (Woodhead Publishing, 2011).

Behroozi, A. H. et al. Electrolyte solution of MDEA–PZ–TMS for CO2 absorption; response surface methodology and equilibrium modeling. Environ. Technol. Innov. 23, 101619 (2021).

Halim, S. F. A., Kamaruddin, A. H. & Fernando, W. J. N. Continuous biosynthesis of biodiesel from waste cooking palm oil in a packed bed reactor: Optimization using response surface methodology (RSM) and mass transfer studies. Biores. Technol. 100(2), 710–716 (2009).

Helmi, M., Tahvildari, K. & Hemmati, A. Parametric optimization of biodiesel synthesis from Capparis spinosa oil using NaOH/NaX as nanoheterogeneous catalyst by response surface methodology. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 38(1), 61–75 (2020).

Talebian-Kiakalaieh, A. et al. Transesterification of waste cooking oil by heteropoly acid (HPA) catalyst: Optimization and kinetic model. Appl. Energy 102, 283–292 (2013).

Ma, Y.-X. et al. Preparation of polyamidoamine dendrimers functionalized magnetic graphene oxide for the adsorption of Hg(II) in aqueous solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 505, 352–363 (2017).

Zhou, Z. et al. Preparation and adsorption characteristics of an ion-imprinted polymer for fast removal of Ni(II) ions from aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 341, 355–364 (2018).

Chatterjee, A. & Schiewer, S. Multi-resistance kinetic models for biosorption of Cd by raw and immobilized citrus peels in batch and packed-bed columns. Chem. Eng. J. 244, 105–116 (2014).

Pashaei, H. & Ghaemi, A. CO2 absorption into aqueous diethanolamine solution with nano heavy metal oxide particles using stirrer bubble column: Hydrodynamics and mass transfer. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8(5), 104110 (2020).

Yao, C. & Chen, T. A weighted average kinetic equation and its application in estimating mass transfer coefficients in liquid phase adsorption. Biophys. Chem. 241, 50–54 (2018).

Masoumi, H., Ghaemi, A. & Gannadzadeh Gilani, H. Synthesis of polystyrene-based hyper-cross-linked polymers for Cd(II) ions removal from aqueous solutions: Experimental and RSM modeling. J. Hazard. Mater. 416, 125923 (2021).

Helmi, M. et al. Synthesis, characterization and performance evaluation of NaOH@ Chitosan-Fe3O4 as an adsorbent for CO2 capture. Fuel 338, 127300 (2023).

Al-Jammal, N., Al-Hamamre, Z. & Alnaief, M. Manufacturing of zeolite based catalyst from zeolite tuft for biodiesel production from waste sunflower oil. Renew. Energy 93, 449–459 (2016).

Amiri-Yazani, T. et al. Highly efficient ultrasonic-assisted pre-concentration and simultaneous determination of trace amounts of Pb(II) and Cd(II) ions using modified magnetic natural clinoptilolite zeolite: Response surface methodology. Microchem. J. 146, 498–508 (2019).

Mahmoudi, J. & Rahimi, M. Studies on optimization of efficient parameters for removal of lead from aqueous solutions by natural zeolite as a low-cost adsorbent using response surface methodology. Adv. Environ. Technol. 3(2), 99–108 (2017).

Ain, Q.-U., Farooq, M. U. & Jalees, M. I. Application of magnetic graphene oxide for water purification: Heavy metals removal and disinfection. J. Water Process Eng. 33, 101044 (2020).

Masteri-Farahani, M. & Modarres, M. Clicked graphene oxide as new support for the immobilization of peroxophosphotungstate: Efficient catalysts for the epoxidation of olefins. Colloids Surf. A 529, 886–892 (2017).

Kubelková, L. et al. Zeolite Chemistry and Catalysis (Elsevier, 1991).

Sadighian, S. et al. Preparation of graphene oxide/Fe3O4 nanocomposite as a potential magnetic nanocarrier and MRI contrast agent. ChemistrySelect 6(12), 2862–2868 (2021).

Bahrami, M. & Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. Effect of the supported ZnO on clinoptilolite nano-particles in the photodecolorization of semi-real sample bromothymol blue aqueous solution. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 30, 275–284 (2015).

Fitriana, N. et al. Synthesis of K2O/Zeolite catalysts by KOH impregnation for biodiesel production from waste frying oil. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 1–7 (2018).

Sheshmani, S. & Fashapoyeh, M. A. Suitable chemical methods for preparation of graphene oxide, graphene and surface functionalized graphene nanosheets. Acta Chim. Slov. 60(4), 813–825 (2013).

Gomes, J. et al. Chapter 25—Monitoring and control of bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass. In Waste Biorefinery (eds Bhaskar, T. et al.) 727–749 (Elsevier, 2018).

Musyoka, N. M. et al. Thermal stability studies of zeolites A and X synthesized from South African coal fly ash. Res. Chem. Intermed. 41(2), 575–582 (2015).

Zhou, C. et al. A first principles study of gas adsorption on charged CuBTC. Comput. Theor. Chem. 976(1), 153–160 (2011).

Zhao, Y. et al. Insight into the mechanism of CO2 adsorption on Cu–BTC and its composites with graphite oxide or aminated graphite oxide. Chem. Eng. J. 239, 399–407 (2014).

Sudeep, P. M. et al. Covalently interconnected three-dimensional graphene oxide solids. ACS Nano 7(8), 7034–7040 (2013).

Davarpanah, E. et al. CO2 capture on natural zeolite clinoptilolite: Effect of temperature and role of the adsorption sites. J. Environ. Manag. 275, 111229 (2020).

Ghaemi, A., Karimi Dehnavi, M. & Khoshraftar, Z. Exploring artificial neural network approach and RSM modeling in the prediction of CO2 capture using carbon molecular sieves. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 7, 100310 (2023).

Tan, Y. H. et al. Application of RSM and Taguchi methods for optimizing the transesterification of waste cooking oil catalyzed by solid ostrich and chicken-eggshell derived CaO. Renew. Energy 114, 437–447 (2017).

Tan, Y. H. et al. Biodiesel production from used cooking oil using green solid catalyst derived from calcined fusion waste chicken and fish bones. Renew. Energy 139, 696–706 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Catalytic performance of NaAlO2/γ-Al2O3 as heterogeneous nanocatalyst for biodiesel production: Optimization using response surface methodology. Energy Convers. Manag. 203, 112263 (2020).

Sulaiman, N. F. et al. In depth investigation of bi-functional, Cu/Zn/γ-Al2O3 catalyst in biodiesel production from low-grade cooking oil: Optimization using response surface methodology. Renew. Energy 135, 408–416 (2019).

Yellapu, S. K. et al. Detergent assisted lipid extraction from wet yeast biomass for biodiesel: A response surface methodology approach. Biores. Technol. 218, 667–673 (2016).

Noshadi, I., Amin, N. A. S. & Parnas, R. S. Continuous production of biodiesel from waste cooking oil in a reactive distillation column catalyzed by solid heteropolyacid: Optimization using response surface methodology (RSM). Fuel 94, 156–164 (2012).

Körbahti, B. K. & Rauf, M. A. Response surface methodology (RSM) analysis of photoinduced decoloration of toludine blue. Chem. Eng. J. 136(1), 25–30 (2008).

Jeirani, Z. et al. The optimal mixture design of experiments: Alternative method in optimizing the aqueous phase composition of a microemulsion. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 112, 1–7 (2012).

Taheri, F. S., Ghaemi, A. & Maleki, A. High efficiency and eco-friendly TEPA-functionalized adsorbent with enhanced porosity for CO2 capture. Energy Fuels 33(11), 11465–11476 (2019).

Taheri, F. S. et al. High CO2 adsorption on amine-functionalized improved mesoporous silica nanotube as an eco-friendly nanocomposite. Energy Fuels 33(6), 5384–5397 (2019).

Gao, Z. et al. Facile one-pot synthesis of Zn/Mg-MOF-74 with unsaturated coordination metal centers for efficient co2 adsorption and conversion to cyclic carbonates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13(51), 61334–61345 (2021).

Khoshraftar, Z. & Ghaemi, A. Presence of activated carbon particles from waste walnut shell as a biosorbent in monoethanolamine (MEA) solution to enhance carbon dioxide absorption. Heliyon 8(1) (2022).

Kumar Jha, R., Bhunia, H. & Basu, S. UV activated monolithic graphene oxide-based adsorbents for dynamic CO2 capture: Kinetic, isotherm and thermodynamic studies. Chem. Eng. Sci. 285, 119572 (2024).

Ramezanipour Penchah, H., Ghaemi, A. & Ganadzadeh Gilani, H. Benzene-based hyper-cross-linked polymer with enhanced adsorption capacity for CO2 capture. Energy Fuels 33(12), 12578–12586 (2019).

Ramezanipour Penchah, H., Ghaemi, A. & Godarziani, H. Eco-friendly CO2 adsorbent by impregnation of diethanolamine in nanoclay montmorillonite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28(39), 55754–55770 (2021).

Al-Ghouti, M. A. & Da’ana, D. A. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of adsorption isotherm models: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 393, 122383 (2020).

Fashi, F., Ghaemi, A. & Moradi, P. Piperazine-modified activated alumina as a novel promising candidate for CO2 capture: Experimental and modeling. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 9(1), 37–51 (2019).

Weber, W. J. Jr. & Morris, J. C. Kinetics of adsorption on carbon from solution. J. Sanit. Eng. division 89(2), 31–59 (1963).

Subha, R. & Namasivayam, C. Modeling of adsorption isotherms and kinetics of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol onto microporous ZnCl2 activated coir pith carbon. J. Environ. Eng. Manag 18(4), 275–280 (2008).

Bulut, E., Özacar, M. & Şengil, İA. Adsorption of malachite green onto bentonite: Equilibrium and kinetic studies and process design. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 115(3), 234–246 (2008).

Özacar, M. & Şengil, İA. A kinetic study of metal complex dye sorption onto pine sawdust. Process Biochem. 40(2), 565–572 (2005).

Andreoli, E., Cullum, L. & Barron, A. R. Carbon dioxide absorption by polyethylenimine-functionalized nanocarbons: A Kinetic Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54(3), 878–889 (2015).

Raganati, F. et al. Isotherms and thermodynamics of CO2 adsorption on a novel carbon-magnetite composite sorbent. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 134, 540–552 (2018).

Tran, H. N., You, S.-J. & Chao, H.-P. Thermodynamic parameters of cadmium adsorption onto orange peel calculated from various methods: A comparison study. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 4(3), 2671–2682 (2016).

Adelodun, A. A. et al. Isotherm, thermodynamic and kinetic studies of selective CO2 adsorption on chemically modified carbon surfaces. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 16(12), 3312–3329 (2016).

Raganati, F., Miccio, F. & Ammendola, P. Adsorption of carbon dioxide for post-combustion capture: A review. Energy Fuels 35(16), 12845–12868 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Maryam Helmi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Conceived and designed the experiments, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Ahad Ghaemi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Conceived and designed the experiments, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision Visualization, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Mohammad Amin Sobati: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Conceived and designed the experiments, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Helmi, M., Ghaemi, A. & Sobati, M.A. Exploring behavior of Clinoptilolite@Graphene oxide compositeas a novel adsorbent for CO2 capture. Sci Rep 15, 30135 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15204-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15204-4