Abstract

This study aimed to assess the prognostic value of the log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS) in resectable nonmetastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and its potential role in informing postoperative treatment decisions. A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from the SEER 17 registries, including patients aged 20–79 diagnosed with TNBC. The association between LODDS and cancer-specific survival (CSS) was analyzed using the restrictive cubic splines (RCS) method. Propensity score matching (PSM) and survival analysis were employed to evaluate the effect of LODDS on treatment outcomes. Between 2010 and 2021, breast-conserving surgery (BCS) emerged as the predominant surgical approach for resectable nonmetastatic TNBC, with its proportion increasing from 49.3 to 52.1%, while mastectomy rates declined from 46.5 to 38.9%. RCS analysis identified a significant nonlinear association (p < 0.001) between LODDS and CSS, with a threshold value of -1.6 effectively categorizing patients into low-risk (LODDS < -1.6) and high-risk (LODDS > -1.6) groups. Patients in the low-risk group exhibited superior survival, with 5-year and 10-year CSS rates improving by 7.3% and 8.4%, respectively, following PSM. Notably, BCS was associated with better survival outcomes compared to mastectomy, particularly in high-risk LODDS patients. Stratified analysis by LODDS and age revealed that BCS followed by radiotherapy conferred the most substantial survival benefit. LODDS is a reliable prognostic marker for survival outcomes in resectable nonmetastatic TNBC. Incorporating LODDS into age-based risk stratification can facilitate more personalized postoperative management following BCS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), characterized by the lack of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression, accounts for approximately 15–20% of all breast cancer cases1. Despite its lower incidence, TNBC is associated with aggressive tumor biology, high recurrence rates, and limited therapeutic options, leading to poorer survival outcomes compared to other breast cancer subtypes2. Surgical intervention remains the primary curative treatment for resectable nonmetastatic TNBC, with breast-conserving surgery (BCS) and mastectomy as the main surgical approaches3. While randomized trials and large observational studies have demonstrated the non-inferiority of breast-conserving therapy with radiotherapy versus mastectomy in early-stage breast cancer4,5,6,7, comparative studies specifically assessing these surgical methods in TNBC remain scarce, given its aggressive biology and higher recurrence risk8.

Lymph node status is a well-established prognostic factor in breast cancer, significantly influencing treatment decisions and survival outcomes. Traditional nodal staging markers, such as the number of positive lymph node (PLN) and the lymph node ratio (LNR), have been widely used for prognosis assessment9. However, these markers may fail to provide an accurate risk stratification, particularly in cases with limited lymph node yield or varying numbers of negative lymph nodes10. Recently, the log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS), which combines both positive and negative lymph node counts into a continuous variable, has emerged as a promising alternative prognostic marker. Several studies have shown the prognostic superiority of LODDS across various malignancies. Two studies demonstrated that LODDS was an independent predictor of survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer, outperforming PLN and LNR in survival prediction, based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data11,12. A single-center analysis of 323 patients with rectal cancer found that LODDS provided better risk stratification than N stage and LNR, particularly when nodal harvest was suboptimal13.

In breast cancer, the evidence supporting LODDS as a prognostic tool remains limited. While a few studies have suggested that LODDS offers improved prognostic accuracy compared to traditional PLN or LNR10,14, these findings predominantly derive from research on hormone receptor-positive or HER2-positive breast cancer subtypes. To date, specific data on the prognostic value of LODDS in TNBC are scarce, and no large-scale, population-based studies have systematically examined its relationship with cancer-specific survival (CSS) in this aggressive subtype.

Adjuvant treatment for TNBC remains a subject of debate, with ongoing controversies surrounding optimal chemotherapy regimens, the role of radiotherapy, and the incorporation of novel therapeutic agents15,16. To address these gaps in knowledge, this study explored the prognostic role of LODDS in patients with resectable nonmetastatic TNBC using a population-based dataset. Through a comprehensive analysis, this study offers novel insights that could improve risk stratification and optimize treatment strategies for patients with TNBC.

Methods

Study population

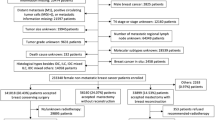

This retrospective, population-based cohort study utilized data from the SEER 17 registries to identify eligible patients: those aged 20–79 years diagnosed with microscopically confirmed TNBC (HR−/HER2−) between 2010 and 2021. Patients with multiple primary malignancies, metastatic disease (M1 stage), diagnosis via autopsy only, or a surgery history of local tumor destruction or unknown procedures were excluded.

Study design

A descriptive analysis was performed to evaluate the trends in surgical approaches for patients with nonmetastatic TNBC over the study period (2010–2021) and across different age groups (20–39, 40–64, and 65–79 years). The restrictive cubic spline (RCS) method was then applied to investigate the prognostic significance of the LODDS in resectable nonmetastatic TNBC. LODDS was calculated using the formula:

Propensity score matching (PSM) and survival analysis were conducted to assess survival disparities between patients with low-risk and high-risk LODDS. To ensure a minimum four-year follow-up, only patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2017 were included in the analysis. Additional exclusions were made for patients with unknown or no surgery or lymph node dissection (LND) history, unknown number of PLN, prior neoadjuvant treatment, unknown adjuvant treatment history, or survival times shorter than three months. The effect of postoperative treatments on survival was analyzed, with a focus on patients stratified by LODDS risk groups.

Primary study endpoint and variables

The primary study endpoint was the CSS, defined as the time from TNBC diagnosis to death attributed specifically to TNBC. Patients who were alive at the final follow-up date (December 31, 2021) or who died from causes unrelated to TNBC were considered censored cases.

Key variables and subgroups included age (20–39, 40–64, 65–79 years), race (White, Black, Other), tumor size (0–20 mm, 21–50 mm, > 50 mm, unknown), tumor grade (low-grade, high-grade, unknown), surgery type (BCS or mastectomy), and adjuvant treatment (none, chemotherapy, radiotherapy [RT], chemoradiotherapy [CRT]).

Statistical analyses

Clinical characteristics were presented as counts and percentages, with comparisons made using Pearson’s Chi-squared test. Survival analysis, and 5-year and 10-year survival rates were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived using univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models.

The RCS method was used to identify critical inflection points in LODDS for survival risk stratification. Based on a multivariable Cox model, three knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of LODDS were applied to explore the nonlinear prognostic relationship between LODDS and CSS.

PSM was performed with 1:1 or 1:5 matching ratios to balance baseline clinical characteristics between patient subgroups. Extreme outliers were excluded from both groups in the PSM analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.0). A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Trends in surgical methods for resectable nonmetastatic TNBC

Overall, BCS emerged as the most frequently performed surgical method for resectable nonmetastatic TNBC, with its proportion increasing from 49.3% in 2010 to 52.1% in 2021, while mastectomy rates declined from 46.5 to 38.9%. Concurrently, the proportion of patients who did not undergo surgery rose from 4.2 to 9.1% (Fig. 1A). Age-stratified analyses revealed trends in the 40–64 and 65–79 age groups that closely mirrored the overall population, with the most significant changes observed in patients aged 65–79 years. Conversely, no significant shifts in surgical methods were observed among patients aged 20–39 years (Fig. 1B–D).

Prognostic role of LODDS in resectable nonmetastatic TNBC

A total of 19,075 patients who underwent both surgery and LND—defined as having at least one lymph node dissected—were included, alongside 489 patients who underwent surgery only, with no LND. Notably, only 4787 of the 19,075 patients (25.1%) had pathologically confirmed PLN.

Comparisons of clinical characteristics between patients who underwent both surgery and LND and those who underwent surgery only were made before and after PSM with a 1:5 matching ratio, as presented in Table S1. Figure S2 illustrates the absolute standardized mean differences (SMDs) for baseline characteristics before and after matching. The plot demonstrates a substantial reduction in SMDs post-matching, indicating improved covariate balance between the comparison groups. Survival outcomes consistently favored patients who underwent both surgery and LND, both before and after PSM (Fig. 2A, B).

To assess the nonlinear prognostic relationship between LODDS and the HR for CSS in patients with resectable nonmetastatic TNBC (those who underwent both surgery and LND), the RCS method was applied, with adjustments for all included variables. As shown in Fig. 3A, a significant nonlinear relationship (nonlinearity, p < 0.001) was observed when LODDS was used to predict cancer-specific mortality. The optimal cutoff for LODDS was −1.6, where the risk for death equaled 1. The risk of cancer-specific mortality increased markedly in patients with LODDS >-1.6 (high-risk) when compared to those with LODDS <-1.6 (low-risk). This finding was consistent across age subgroups and surgery type subgroups, with the exception of patients aged 20–39 years (Fig. 3B–F).

Restricted cubic spline curves illustrating the association between LODDS and cancer-specific death. (A) All patient, (B) Age 20–39 years, (C) Age 40–64 years, (D) Age 65–79 years, (E) Patients who underwent BCS, (F) Patients who underwent mastectomy. The blue curves represent the hazard ratio, and the shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence interval. The vertical gray dashed line marks the optimal cutoff value. LODDS log odds of positive lymph nodes, BCS breast-conserving surgery.

Based on the established LODDS cutoff of −1.6, 12,273 patients were assigned to the low-risk group, while 6802 patients were categorized into the high-risk group. The low-risk group generally comprised younger patients, had smaller tumor sizes, and was less likely to receive intensive adjuvant treatment (with adjuvant CRT administered to 39.9% vs. 49.4% of patients, p < 0.001) (Table 1). Survival analysis revealed a marked prognostic difference between the two groups. In the high-risk group, the 5-year CSS rate was 82.1%, compared to 91.1% in the low-risk group, while the 10-year CSS rate was 78.1% versus 88.5%, respectively (Fig. 4A). The corresponding HR for CSS was 2.07 (95% CI: 1.92–2.24, p < 0.001). After PSM to account for baseline characteristics imbalances (Table 1 & Figure S3), survival differences remained significant. The 5-year (83.0% vs. 90.2%) and 10-year (79.1% vs. 87.5%) CSS rates remained lower in the high-risk group (Fig. 4B), with a significant higher risk of death (HR 1.79, 95%CI 1.63–1.97, p < 0.001). Subgroup analysis indicated that all subgroups in the low-risk group had a lower risk of death (Figure S1).

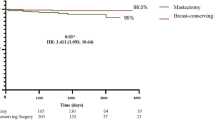

Survival disparities between BCS and mastectomy stratified by LODDS

Survival disparities were further examined according to surgical method (BCS vs. mastectomy), stratified by LODDS. Among patients with low-risk LODDS, those who underwent BCS demonstrated superior CSS compared to those who underwent mastectomy, with this trend persisting after PSM (Fig. 5A,B and Table S2 and Figure S4), although the difference in 5-year and 10-year CSS rates were modest. Subgroup analysis revealed that survival benefits were most pronounced in patients aged 40–64 years and those with high-grade tumors (Fig. 6A). Among patients with high-risk LODDS, BCS was also associated with superior CSS, both before and after PSM (Fig. 5C,D & Table S3 and Figure S5). In this group, the 5-year and 10-year CSS rates decreased by 8.7% and 11.1%, respectively, for those who underwent mastectomy, with the HR for death increasing by 66% (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.45–1.91, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5D). Subgroup analysis showed that only patients aged 20–39 years and those from the Black population did not benefit from BCS (Fig. 6B).

Impact of post-BCS adjuvant treatments on survival outcomes

Given the superior survival of patients who underwent BCS compared to those who had mastectomy, the impact of postoperative treatments on survival was further explored in BCS patients. Survival analysis revealed that, among low-risk patients undergoing BCS, those who received adjuvant RT and adjuvant CRT exhibited similar survival benefits to those treated with adjuvant chemotherapy or no adjuvant treatment (Fig. 7A, log-rank p < 0.001). In high-risk patients undergoing BCS, survival analysis showed that the greatest benefit was observed with adjuvant RT, followed by CRT, chemotherapy, and no treatment (Fig. 7B, log-rank p < 0.001). HRs for death were calculated and adjusted using both univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models. For low-risk patients undergoing BCS, adjuvant RT was associated with a relatively lower HR compared to adjuvant CRT when compared to no treatment. Notably, the reduction in HR was significant only in the 40–64 years age subgroup (Fig. 7C). Adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a similar risk of death compared to no treatment. In high-risk BCS patients, the most significant reduction in the risk of death was also seen with adjuvant RT, followed by CRT. No difference in the risk of death was observed between adjuvant chemotherapy and no treatment. The HR reduction was observed in patients aged 40–64 years and 65–79 years, but not in those aged 20–39 years (Fig. 7D).

Impact of adjuvant treatments on survival in patients who underwent breast-conserving surgery. (A) Survival analysis in patients with low-risk LODDS stratified by adjuvant treatments; (B) Survival analysis in patients with high-risk LODDS stratified by adjuvant treatments; (C) HR of different adjuvant treatments in patients with low-risk LODDS; (D) HR of different adjuvant treatments in patients with high-risk LODDS. LODDS log odds of positive lymph nodes, HR hazard ratio.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first large-scale population-based analysis to systematically evaluate the prognostic role of LODDS in patients with resectable nonmetastatic TNBC. Additionally, it assesses the comparative effectiveness of BCS versus mastectomy and the impact of postoperative treatments on survival, based on LODDS stratification.

TNBC is characterized by an aggressive nature, limited therapeutic options, and a high propensity for recurrence and metastasis, making it one of the most challenging breast cancer subtypes to manage17. Accurate prognostic stratification is essential for guiding individualized treatment strategies aimed at optimizing patient outcomes. In this study, a nonlinear relationship between LODDS and CSS was identified. Specifically, an optimal LODDS cutoff value of -1.6 effectively stratified patients into low-risk and high-risk groups, suggesting a threshold beyond which the risk of cancer-specific mortality sharply increased. Patients with LODDS < -1.6 demonstrated more than an 8% improvement in long-term survival (10-year CSS). These findings are consistent with prior research, which has established LODDS as a robust prognostic marker in breast cancer, surpassing traditional markers such as the PLN and LNR in predictive accuracy10,14. Therefore, integrating LODDS into clinical practice is commended as a valuable tool for risk stratification and for guiding postoperative treatment strategies in resectable nonmetastatic TNBC.

Beyond lymph node involvement, the selection of surgical method played a pivotal role in determining long-term survival outcomes for patients with TNBC. Previous studies have increasingly recognized BCS followed by RT as an effective treatment modality, yielding locoregional recurrence rates comparable to mastectomy18,19. Furthermore, BCS combined with RT was associated with superior long-term survival outcomes20,21. In line with these findings, our study revealed that, regardless of LODDS status, BCS was associated with better survival outcomes compared to mastectomy. Notably, the survival benefit of BCS was more pronounced in patients with higher LODDS levels, with a 5-year survival advantage of 8.7% and a 10-year survival advantage of 11.1%. In contrast, for patients with low LODDS, the survival differences between the two surgical methods were relatively small, particularly among subgroups of patients aged 40–64 years and those with high-grade tumor. This could be explained by lower LODDS values typically reflecting less aggressive tumor biology and a lower burden of lymphatic spread, resulting in inherently better survival outcomes. Thus, the choice of surgical method may have had a lesser impact on long-term survival in the low-risk LODDS group. Interestingly, our study also showed that among both low-risk and high-risk LODDS subgroups, patients with tumors larger than 50 mm who underwent BCS exhibited better CSS outcomes compared to those who underwent mastectomy (Fig. 6). However, this finding should be interpreted with caution, as the number of patients with tumors larger than 50 mm was relatively small. A potential explanation could involve differences in adjuvant therapy administration, such as a lower likelihood of receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy in the mastectomy group. These treatment disparities could confound survival comparisons and warrant further investigation in future large-scale studies.

Our findings are partially supported by previous retrospective studies. Two large-scale analyses demonstrated that, in patients with T1-2N0M0 TNBC, BCS followed by RT was associated with superior survival outcomes compared to mastectomy, regardless of whether RT was administered22,23. Additionally, another study reported that among patients with small, aggressive subtypes—such as triple-negative or HER2-enriched ipsilateral breast cancer recurrence—those who underwent a second BCS exhibited significantly improved survival compared to those who received mastectomy, with the most pronounced benefit observed in tumors less than 16 mm in size24. These findings further emphasize the importance of considering both biological tumor characteristics and lymphatic involvement when making surgical decisions.

The selection of postoperative treatment strategies plays a pivotal role in improving outcomes in TNBC. Historically, chemotherapy has been the cornerstone of adjuvant treatment for TNBC, particularly in high-risk cases, and is associated with improved survival outcomes25. However, the role of adjuvant RT remains debated. A meta-analysis of 5507 patients found that while adjuvant RT reduced the risk of locoregional recurrence in patients with TNBC, irrespective of surgical method, it did not provide a survival benefit26. Furthermore, another study indicated that only women under 40 years of age benefited from BCS followed by RT compared to mastectomy, with or without RT27. In contrast to these studies, our findings suggest that although CRT was the most frequently used postoperative treatment, RT alone provided a more significant survival benefit across both LODDS subgroups. Notably, the benefit of adjuvant RT varied across LODDS and age subgroups. A review examining the role of RT in managing locoregional TNBC highlighted that despite concerns about potential radioresistance, TNBC still benefited from RT in reducing locoregional recurrence28. Consistent with this, this study observed that patients with high-risk LODDS, despite having poorer survival outcomes, derived comparable survival benefits from BCS followed by RT, similar to those in the low-risk LODDS group who underwent the same treatment. This finding supports the efficacy of BCS combined with RT in managing TNBC, particularly for patients with high-risk LODDS.

This study did not observe a survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy compared to no adjuvant treatment. However, prior studies have demonstrated the significant efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in early-stage TNBC. For example, recent population-based analyses showed improved survival in patients with early-stage TNBC who received adjuvant chemotherapy29,30. This discrepancy may be due to limitations of the SEER database, which lacks detailed information on chemotherapy regimens, such as dosage, duration, and completion status. The absence of these critical treatment details may have confounded the accurate assessment of chemotherapy’s effect on survival. Therefore, the observed lack of survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in this study should be interpreted with caution and further validated in cohorts with more comprehensive data on systemic therapy.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, the retrospective design introduced potential biases, including selection and information bias. However, efforts were made to minimize the impact of these biases on survival analysis through PSM. Second, while the study focused on the relationship between LODDS and CSS, detailed treatment regimens and response data were not available. The absence of information on adjuvant chemotherapy regimens, RT, and treatment response limited the ability to fully assess how LODDS interacted with these treatment modalities, potentially underestimating its role in guiding treatment decisions. Third, molecular and genetic data, such as BRCA1/2 mutation status, were not included in the SEER database and, therefore, were not incorporated into this study. This represents a notable limitation, as BRCA1/2 mutations are relatively common in TNBC and significantly influence tumor biology, treatment responses, and survival outcomes. The lack of such molecular information may have hindered the comprehensive evaluation of LODDS’s prognostic performance across genetically distinct TNBC subgroups. Future studies integrating molecular features with lymph node metrics like LODDS are warranted to enable more precise risk stratification and treatment optimization. Fourth, detailed information on RT parameters, including dose, laterality, specific target fields (e.g., whole breast, chest wall, or regional nodal irradiation), and treatment completion, was not available in the SEER database. These unmeasured variables could differ significantly between patients undergoing BCS and mastectomy, potentially confounding the observed survival outcomes related to RT.

Conclusion

In conclusion, LODDS emerges as a robust prognostic marker for predicting survival outcomes in patients with resectable nonmetastatic TNBC. Integrating LODDS into clinical practice can guide surgical decision-making, favoring BCS over mastectomy in high-risk patients, and optimize postoperative management through personalized treatment strategies. These results have significant clinical implications, offering a practical approach to risk stratification and treatment optimization in TNBC.

Data availability

All datasets in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon any reasonable request.

References

Giaquinto, A. N. et al. Breast cancer statistics 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 477 (2024).

Kim, J. E. et al. Impact of triple-negative breast cancer phenotype on prognosis in patients with stage I breast cancer. J. Breast Cancer. 15, 197 (2012).

Fancellu, A. et al. Outcomes after breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy in patients with triple-negative breast cancer: meta-analysis. Br. J. Surg. 108, 760 (2021).

Poggi, M. M. et al. Eighteen-year results in the treatment of early breast carcinoma with mastectomy versus breast conservation therapy: the National cancer Institute randomized trial. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 98, 697 (2003).

Fisher, B. et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 347, 1233 (2002).

van Maaren, M. C. et al. 10 year survival after breast-conserving surgery plus radiotherapy compared with mastectomy in early breast cancer in the netherlands: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 17, 1158 (2016).

Clarke, M. et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 366 (2005). (2087).

Hu, J. et al. Triple-negative metaplastic breast cancer: treatment and prognosis by type of surgery. Am. J. Transl Res. 13, 11689 (2021).

Urakci, Z. et al. Superiority of pathologic lymph node ratio over positive lymph node count in operated Early-Stage breast cancer. Ann. Ital. Chir. 95, 1170 (2024).

Wen, J. et al. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram based on the log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS) for breast cancer. Oncotarget 7, 21046 (2016).

Jin, X. et al. Log odds of positive lymph nodes is a robust predictor of survival and benefits from postoperative radiotherapy in stage IIIA-N2 resected non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer. 13, 2767 (2022).

Yu, Y. et al. Prognostic value of log odds of positive lymph nodes in node-positive lung squamous cell carcinoma patients after surgery: a SEER population-based study. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 9, 1285 (2020).

Scarinci, A. et al. The impact of log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS) in colon and rectal cancer patient stratification: a single-center analysis of 323 patients. Updates Surg. 70, 23 (2018).

Chen, L. J., Chung, K. P., Chang, Y. J. & Chang, Y. J. Ratio and log odds of positive lymph nodes in breast cancer patients with mastectomy. Surg. Oncol. 24, 239 (2015).

Guven, D. C. et al. Optimal adjuvant treatment strategies for TNBC patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant treatment. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 23, 1049 (2023).

Obidiro, O., Battogtokh, G. & Akala, E. O. Triple negative breast cancer treatment options and limitations: future outlook. Pharmaceutics 15 (2023).

Yin, L., Duan, J. J., Bian, X. W. & Yu, S. C. Triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtyping and treatment progress. Breast Cancer Res. 22, 61 (2020).

Krug, D. et al. Breast-conserving surgery is not associated with increased local recurrence in patients with early-stage node-negative triple-negative breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast 74, 103701 (2024).

Macfie, R., Aks, C., Panwala, K., Johnson, N. & Jennifer, G. Breast conservation therapy confers survival and distant recurrence advantage over mastectomy for stage II triple negative breast cancer. Am. J. Surg. 221, 809 (2021).

Wang, S. E., Sun, Y. D., Zhao, S. J., Wei, F. & Yang, G. Breast conserving surgery (BCS) with adjuvant radiation therapy showed improved prognosis compared with mastectomy for early staged triple negative breast cancer patients running title: BCS had better prognosis than mastectomy for early TNBC patients. Math. Biosci. Eng. 17, 92 (2019).

Pan, X. B., Qu, S., Jiang, Y. M. & Zhu, X. D. Triple negative breast cancer versus Non-Triple negative breast cancer treated with breast conservation surgery followed by radiotherapy: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Breast Care (Basel). 10, 413 (2015).

Li, H., Chen, Y., Wang, X., Tang, L. & Guan, X. T1-2N0M0 Triple-Negative breast cancer treated with breast-Conserving therapy has better survival compared to mastectomy: A SEER Population-Based retrospective analysis. Clin. Breast Cancer. 19, e669 (2019).

Saifi, O. et al. Is breast conservation superior to mastectomy in early stage triple negative breast cancer? Breast 62, 144 (2022).

Gentile, D. et al. Salvage mastectomy is not the treatment of choice for aggressive subtypes of ipsilateral breast cancer recurrence: A Single-Institution retrospective study. Eur. J. Breast Health. 18, 315 (2022).

Marra, A. & Curigliano, G. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment of Triple-Negative breast cancer with chemotherapy. Cancer J. 27, 41 (2021).

O’Rorke, M. A., Murray, L. J., Brand, J. S. & Bhoo-Pathy, N. The value of adjuvant radiotherapy on survival and recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 5507 patients. Cancer Treat. Rev. 47, 12 (2016).

Bhoo-Pathy, N. et al. Prognostic role of adjuvant radiotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer: A historical cohort study. Int. J. Cancer. 137, 2504 (2015).

Moran, M. S. Radiation therapy in the locoregional treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 16, e113 (2015).

Lo, C. et al. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for T1cN0M0 and selected T1bN0M0 triple-negative breast cancer: a nationwide cancer registry-based study. Oncologist 30 (2025).

Steenbruggen, T. G. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in small node-negative triple-negative breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 135, 66 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ contributions: (I) Conception and design: Jie Jian. (II) Administrative support: Xumei Li. (III) Provision of study materials or patients: Chenchen Zheng, Jingjing Huang, Jiangming Xiang. (IV) Collection and assembly of data: Shengping Zhao, Yuxi Peng, Qian Xiong. (V) Data analysis and interpretation: Chenchen Zheng, Jingjing Huang, Jie Jian. (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors. (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The ethical approval for this study was not required because it is a retrospective analysis of public dataset.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, C., Huang, J., Zhao, S. et al. Log odds of positive lymph nodes as a prognostic marker in resectable triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep 15, 30348 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15209-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15209-z