Abstract

With the advancement of industrial aquaculture, intelligent fish feeding has become pivotal in reducing feed and labor costs while enhancing fish welfare. Computer vision, as a non-invasive and efficient approach, has made significant strides in this domain. However, current research still faces three major issues: qualitative labels lead to models that produce only qualitative outputs; redundant information in images causes interference; and the high complexity of models hinders real-time application. To address these challenges, this study innovatively proposes the quantification of fish feeding behaviors through satiety experiments, enabling the generation of quantitative data labels. A two-stage recognition network is then designed to eliminate redundant information and enhance model performance. This network utilizes pose detection to extract key features, while a graph convolutional network (GCN) effectively models the topological relationships between fish posture and distribution, achieving a satiety classification accuracy of 98.1%. Furthermore, to reduce model complexity, lightweight RepSELAN and SPPSF modules were developed, resulting in a 31.4% reduction in parameters and a 26.2% decrease in computational load, with only a 0.11% decrease in mAP(B) and a 0.95% increase in mAP(P). Compared with existing methods, this approach outperforms conventional models in both accuracy and efficiency, providing a novel and efficient model foundation for developing intelligent feeding strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In aquaculture, feed and labor expenses represent a substantial portion of production costs, accounting for approximately 40–60%1, and present significant challenges to operational efficiency, particularly in large-scale systems. Conventional feeding practices predominantly rely on manual methods, guided by the subjective judgment and experience of personnel2,3, which inherently lack the capability for real-time adaptation to fish feeding behavior. This limitation not only escalates labor costs but also increases the risks of overfeeding—resulting in feed wastage and water pollution—or underfeeding, which impairs growth and elevates susceptibility to disease4,5. Fish feeding behavior serves as a critical indicator of hunger levels and appetite fluctuations, enabling precise feed allocation to enhance feed utilization efficiency while concurrently reducing labor requirements6. The development of a feeding intensity classification algorithm, informed by behavioral analysis, provides a robust and scientifically grounded framework for optimizing aquaculture practices, thereby supporting the sustainable development of large-scale industrial operations7.

Computer vision provides an automated, non-invasive, and highly efficient methodology that has significantly advanced research on fish feeding behavior8,9,10,11. The advent of deep learning has further enabled the development of feeding behavior datasets and the application of advanced algorithms for fish feeding classification, delivering notable achievements. For instance, Ubina et al.12 employed aerial unmanned drones to capture RGB surface videos exhibiting pronounced optical flow during fish feeding events. These videos were manually categorized into four levels of feeding intensity—strong, medium, weak, and none—and analyzed using a three-dimensional convolutional neural network (3D CNN), achieving an impressive classification accuracy of 95%. Similarly, Du et al.13 constructed an audio dataset for Oplegnathus punctatus. Audio feature maps were manually labeled into three classes—strong, medium, and none—and subsequently processed by the LC-GhostNet network for feature extraction, attaining a classification accuracy of 85.9%. Despite their high accuracy, these methods exhibit two critical limitations. First, the network models rely on visual or audio inputs, such as images or videos, which, while rich in positional and semantic information, also introduce substantial redundant data, including background, lighting variations, and noise. This redundancy increases the complexity of training, adds computational overhead, and complicates model design. Second, these models generate predominantly qualitative outputs. Although these networks are computationally intensive, their qualitative classification of datasets leads to qualitative outputs. Consequently, these outcomes are suboptimal for determining accurate feed quantities required in real-world production processes.

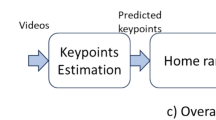

Pose-based action recognition can effectively eliminate redundant information while preserving essential action features, yielding superior recognition results on smaller datasets and demonstrating robust generalization capability14. Sohaib et al.15 and Sun et al.16 both employed pose estimation techniques for action recognition. Sohaib et al. used the YOLOv8 algorithm to predict human body key points and applied LSTM for action classification in aerial videos, while Sun et al. integrated the SSD detector with convolutional pose machines (CPM) to extract skeletal data and generate pose heatmaps for action recognition. Meanwhile, Fu et al.17 enhanced the YOLOv7-Pose algorithm to capture fitness action poses in various scenarios, directly applying these poses for action recognition. Hua et al.18 employed YOLOX-pose19 to capture key points of cows, generating key point heatmaps and using an effective PoseC3D model for cow action recognition, achieving 92.6% accuracy. Building upon this, in order to minimize redundant information, the present study leverages YOLOv8-pose to capture both individual fish pose data and the spatial distribution patterns of fish schools. Moreover, to alleviate the computational demands during both training and inference, the SPPFS and RepSELAN structures, designed specifically for this study, were integrated, significantly enhancing the efficiency of YOLOv8-pose and ultimately resulting in the development of the TinyYOLO-Pose network.

While these methods leverage keypoints and pose information for action recognition with high accuracy, directly feeding poses or keypoint heatmaps into classification networks can lead to the loss of critical spatial or contextual information, which may negatively impact performance. Fish schools exhibit social attributes, forming an invisible connection that is crucial for understanding group interactions20. This can be likened to real-world graph structures, such as social networks, information networks, and chemical molecular structures21,22,23. Inspired by this, our approach abstracts individual fish as nodes, encoding both their swimming poses and the distribution patterns within the fish school as node features. The relationships between the fish are represented as edges, with the distances between them encoded as edge features, thereby establishing a graph-based representation of fish school behavior. Graph convolutional networks (GCNs) are particularly well-suited for modeling this dynamic, as they aggregate features from neighboring nodes to learn node state embeddings, making them ideal for representing fish school behavior24. Based on this, we designed a graph classification network with just three layers of graph convolution, enabling the effective classification of the graph data.

Ultimately, to ensure quantitative results from the model output, we conducted satiety experiments, differentiating fish school feeding behaviors based on varying satiety levels under optimal feeding strategies, creating a dataset that quantifies fish feeding behavior with satiety levels.

In summary, this study presents a novel and practical approach to quantifying fish feeding behavior, with several key contributions. First, we construct a unique satiety dataset derived from rigorously designed feeding experiments, which serves as a valuable benchmark for behavior analysis under varying satiation levels. Second, we propose a lightweight two-stage classification framework: the first stage employs TinyYOLO-pose to efficiently extract individual fish poses and their spatial distribution within the school, generating a graph-based representation that captures both individual and group-level behavior. This explicitly preserves the social structure of the fish school—an important but often neglected aspect in previous research. Third, a graph convolutional network (GCN) is utilized in the second stage to process the graph data and accurately classify feeding behaviors across different satiation levels. Compared to previous approaches, our method offers enhanced interpretability, better efficiency, and improved classification performance. Ultimately, this work contributes not only a new technical pathway for fish behavior monitoring but also a deployable solution that supports intelligent aquaculture management by enabling optimized feeding strategies and cost reduction.

Marterial and methods

Dataset

The data collection process was conducted at the Key Laboratory of Environment Controlled Aquaculture (Dalian Ocean University), Ministry of Education. The experimental subjects were 25 hybrid groupers (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus♂), with an average weight of 65 g. An additional control group, also consisting of 25 hybrid groupers, was included to supplement the experimental group. The aquaculture system consisted of polypropylene plastic cylindrical tanks with a diameter of 0.93 m and a height of 1 m, along with HW-303B water purifiers. The camera system was computer-controlled and positioned overhead for fixed-point shooting, with the cameras placed 1.0 m above the water surface to capture clear and complete images of the water surface.

To simulate the characteristics of batch feeding by automated feeders and to generate a quantitative dataset of fish feeding behavior, a satiation experiment was conducted in an aquaculture scenario. Initially, Pearl Gentian groupers were acclimated to polypropylene plastic round tanks for a period of 15 days. The feeding schedule was set to twice daily at 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., with each session consisting of 1.5% (24 g) of the total body weight of the fish. In the formal experiment, the 24 g of feed was subdivided into varying batch quantities. During each feeding batch, the disappearance of the feed was documented, and the feeding behavior of the fish was observed, as detailed in Table 1. The results indicated that when the feed was divided into 3 or 4 batches, some feed sank to the bottom of the tank, leading to waste. When the feed was divided into 6 or 7 batches, although all feed was consumed, some fish were unable to access the feed, preventing the entire fish group from reaching satiation. In contrast, when the feed was divided into 5 batches, nearly all feed was consumed, and all fish had access to the feed, allowing the group to reach satiation. Based on these findings, the optimal feeding strategy was determined to be 4.8 g per batch across 5 batches, which effectively ensured satiation without feed wastage. This optimal 5-batch strategy is grounded in the physiological needs of fish during feeding. Fish exhibit a limited rate of food intake, and when feed is provided in fewer batches, the fish tend to overconsume in the initial feeding phases, leading to feed wastage or inefficient satiation. Conversely, when feed is provided in excessive batches, the rate of food intake per batch is too low, preventing some fish from reaching satiation due to competition and feeding behavior dynamics. A 5-batch division allows for an optimal distribution of feed that matches the fish’s natural feeding patterns, where they can consume an appropriate amount per batch without overwhelming the digestive system or leaving feed uneaten. This ensures that all fish in the group have access to sufficient food, leading to uniform satiation without waste. The feeding times were consistently maintained at 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. daily. Fixed cameras recorded video footage beginning 30 s prior to each feeding session and ending 30 s after the last batch was consumed. Data collection continued for 8 days, resulting in 15 complete feeding videos with a resolution of 2010 × 2010. In this study, the fish feeding behavior videos were categorized based on satiation levels as the quantitative standard, as outlined in Table 2.The categorized videos were used to construct a fish satiation dataset by extracting 10 keyframes per second. To ensure reproducibility and avoid bias in the data splitting, the dataset was randomly divided into training and validation sets, with the division being performed at an 8/2 ratio. The randomization process was conducted using a fixed random seed to ensure consistency across multiple trials. This procedure is illustrated in Table 3. The data distribution across different satiation levels is illustrated in Fig. 1.

To ensure data stability and enhance reproducibility25, this study strictly controlled the following environmental variables during data collection:

Illumination control: The target environment of this study is recirculating aquaculture system, which typically operates under stable lighting conditions. Furthermore, the fish species commonly cultured in such systems, including Epinephelus fuscoguttatus, Acrossochilus yunnanensis Regan, Micropterus salmoides, and Oncorhynchus mykiss, predominantly feed during daylight. Therefore, the data collection process in this study was conducted under the standard lighting conditions of the system.

Organic matter control: The algorithm proposed in this study requires certain water clarity standards. Therefore, during data collection, it was necessary to control the organic matter content, which includes feces, uneaten feed, and other organic residues. In the recirculating aquaculture system (RAS), organic matter is removed through processes such as microfiltration and nitrification, effectively controlling the organic matter content and maintaining water clarity.

Fish body: The algorithm introduced in this study focuses on the identification of keypoints on the fish body, and explores behavioral analysis based on the geometric relationships between these keypoints. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the algorithm, it is recommended to use fish of the same species and at the same growth stage.

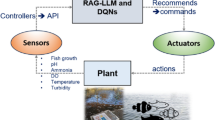

The proposed two-stage fish satiety discrimination model

In this study, a novel two-stage network architecture was designed to classify the satiation levels of fish, as shown in Fig. 2. The first stage involved the development of a lightweight pose detection network, TinyYOLO-pose, which was designed to capture individual fish pose data and the spatial distribution of the fish school. This pose data and the spatial distribution data were then used to construct a graph dataset to better represent fish behavior, and the dataset was subsequently input into a custom-designed Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) for the classification of satiation levels.

TinyYolo-Pose

YOLOv8 enhances the network’s learning capability by increasing both the network depth and feature dimensions26,27,28. While significant progress has been made in balancing detection speed and accuracy, challenges still exist in terms of practical deployment and inference speed, particularly in the context of aquaculture. This study aims to reduce the model’s parameters and computational burden while maintaining stable performance. To address these challenges, we designed two lightweight structures, RepSELAN and SPPFS, to enhance network performance.

In our methodology, we employ RepSELAN to supplant the original C2f module in YOLOv8, addressing the pivotal challenges of effectively extracting features29 and integrating features from different layers to create an efficient and expressive network architecture. Inspired by CSPNet30 and ELAN31, Our RepSELAN network structure integrates the strengths of both cross-stage links and transformation layers, while leveraging the concept of stacking RepNCSP computational modules. This design effectively maintains gradient propagation efficiency and optimizes feature integration. The structure of RepSELAN is shown in Fig. 3. Specifically, the computational module in RepSELAN is RepNCSP (Fig. 4), which is composed of RepSConv and RepBottleneck, as depicted in Fig. 5. In RepNCSP, a 1 × 1 convolution operation is used to halve the input feature dimensions, yielding an n-dimensional feature map. This n-dimensional feature map is then utilized as the input for two distinct branches, [n1, n2]. The former is directly linked to the end of the module, while the latter traverses two computational modules, RepNCSP, to extract features. Following each RepNCSP, there is a CBS transition layer designed to maximize the difference in gradient information. The transition layer serves as a hierarchical feature fusion mechanism that truncates the gradient flow to prevent different layers from learning redundant gradient information. At the conclusion of the module, the outputs of the two RepNCSP computational modules are concatenated with the feature map from the first branch and merged using a 1 × 1 convolution to fuse features of different scales. Traditional single-branch architecture models often struggle to match the performance of multi-branch architecture models, such as ResNet. The multi-branch topology transforms the model into an implicit ensemble of numerous shallow models, thereby circumventing the vanishing gradient problem. Therefore, in the RepNCSP computational module, we adopt a multi-branch structure to bolster the stability of the model. When the input feature map is fed into RepNCSP, it is directed into two branches for gradient information diversion and multi-scale feature extraction.Each branch contains a CBS convolution, performing feature extraction on the input information, which can be denoted as f(x) and g(x) The function f(x) is then passed into a RepBottleneck for deeper feature extraction. The RepBottleneck employs the residual structure from ResNet to deepen the network and uses RepConv structures to broaden the branches, reducing training difficulty. The transformation of f(x) within the RepBottleneck can be expressed as h(f(x)). Finally, the output of RepNCSP is obtained by concatenating the results, yielding g(x) + h(f(x)). To conclude, the RepNCSP module’s multi-branch design and hierarchical feature fusion mechanism enable efficient gradient propagation, effective feature extraction, and optimal integration of multi-scale features, thus enhancing the overall performance and stability of the network.

Meanwhile, the SPPFS is designed to replace the original SPPF module, reducing the model’s parameters while improving the network’s ability to handle features of varying sizes and scales. As shown in Fig. 6, the SPPFS structure performs spatial pooling on the input feature map, capturing contextual information across different receptive field sizes. Specifically, when the feature maps from the preceding level are fed into the SPPFS structure, a 1 × 1 convolution module is first applied to extract features and reduce dimensionality. This process compresses the feature information of the model and minimizes the parameter size. The resulting feature maps are then used as inputs for two branches, with the former directly linked to the end of the module. For the latter branch, drawing inspiration from the ELAN structure, feature maps undergo multi-scale pooling by leveraging three consecutive pooling layers, each with a kernel size of 5 × 5. Through this design, the three pooling layers can integrate features of receptive field sizes of 5 × 5, 9 × 9, and 13 × 13, respectively. At the conclusion of the module, the output of the first branch is concatenated with the feature maps outputted by the three pooling layers of the second branch to fuse features from different receptive fields. Finally, a 1 × 1 convolution module is utilized as a transition layer to infuse non-linear information into the feature maps and augment their dimensionality, enabling the model to obtain richer gradient information during backpropagation.

Graph convolutional network

Based on the output of TinyYOLO-Pose, a graph dataset was constructed to better represent fish behavior, and a carefully designed Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) was employed for the classification of satiation levels.

Specifically, this study defines a graph data representation as \(\:G=(gN,gE)\), where \(\:gN\) is the set of vertices and \(\:gE\) is the set of edges, with each edge \(\:ge\) has two endpoints \(\:gn1\) and \(\:gn2\). Based on this definition, we further define \(\:gN\) to represent individual fish, where each node is described by a vector containing posture features, including the distance from head to tail \(\:l\), the bending angle \(\:\theta\:\), and the coordinates of the bounding box center\(\:\:x\) and \(\:y\). Meanwhile, \(\:gE\) abstractly represents the fully connected edges between fish, and the distance between fish is used as the edge weight. The adjacency matrix \(\:A\) of the graph \(\:G\) is represented as \(\:Aij\), where each \(\:aij\) indicates the weight of the edge between two nodes, and \(\:E\) represents the connection relationships between nodes. We represent the adjacency matrix as Eq. (1):

Given an input feature matrix \(\:X\) and an adjacency matrix \(\:A\), GCN is able to propagate layer by layer in the hidden layers according to Eq. (2). In this equation, \(\:{X}^{k}\)represents the node embeddings at the \(\:k\) layer, \(\:D\) denotes the degree matrix, and \(\:{W}^{k}\) is the learnable parameter of the graph convolution at the \(\:k\) layer.

Based on the constructed fish behavior graph data, this study ultimately designs a GCN network with only three layers of graph convolution to classify fish satiety levels, as shown in Fig. 7. The proposed Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) architecture utilizes graph-based data to effectively capture the complex relationships between individual fish and their behavior in the feeding environment. Specifically, each fish is represented as a node, and the edges between nodes reflect the spatial distances between fish. The adjacency matrix \(\:A\) encodes these relationships, which are essential for understanding the dynamic interactions in a fish school. The GCN model consists of several key components, including three graph convolution layers (G1, G2, and G3) and a final fully connected layer (G4). G1 and G2 perform graph convolutions followed by ReLU activations, which allow the model to extract and refine local fish behavior features by aggregating information from neighboring nodes. The graph convolution process updates each node’s feature representation by considering its own features and those of its neighbors, applying a non-linear transformation to capture the underlying patterns. G3 applies a global pooling layer, which consolidates the information from all nodes, enabling the network to capture global behavior patterns of the fish school. Finally, G4 performs classification by mapping the aggregated node features to the 5 distinct satiation levels. The use of graph convolutions allows the model to not only focus on individual fish behavior but also to understand the spatial and temporal relationships between different fish, which is crucial for accurately classifying fish satiation levels. The architecture effectively reduces redundancy in the input data, enabling the network to learn more meaningful features and achieve high classification accuracy32.

Experimental environment

The experiment was conducted on a computer equipped with an Nvidia RTX4090 graphics processor (24 GB memory). The deep learning framework used was PyTorch 12.1, with PyCharm as the programming platform and Python 3.9 as the programming language. All comparison algorithms were run in the same environment.

Parameter settings

In this study, the training parameter settings for the pose detection network and the graph convolutional classification network are provided separately, as shown in Table 4.

Evaluation metrics

This study propose a two-stage recognition model, consisting of a pose detection network and an action classification network. To assess the complexity of the model, we employ Floating Point Operations (Flops) and Parameters (Params) as evaluation metrics. For the pose detection network and the action classification network, we use Mean Average Precision (mAP) and Accuracy, respectively, as evaluation metrics. The computation formulas for AP are detailed in Eqs. (3–5), while the formula for Accuracy is outlined in Eq. (6).

The parameters in these formulas are defined as follows:

TP: The number of true positive samples, which are actual positive samples correctly classified by the model as positive.

FP: The number of false positive samples, which are actual negative samples incorrectly classified by the model as positive.

TN: The number of true negative samples, which are actual negative samples correctly classified by the model as negative.

FN: The number of false negative samples, which are actual positive samples incorrectly classified by the model as negative.

Experiments

Model efficiency analysis in aquaculture scenarios

In specific aquaculture scenarios, the environmental complexity is relatively low, and the data volume typically remains within a manageable range. Consequently, utilizing models with a high parameter count may lead to neuron inactivity, resulting in ineffective gradient flow and inefficient utilization of computational resources. To validate this hypothesis and determine an optimal model for object detection, we conducted a series of experiments on the advanced YOLOv8 series and our modified TinyYOLO-Pose network. Comparative analyses were performed using YOLOv8n-pose as the baseline, with evaluation metrics including mAP(B) and mAP(P), both assessed at an IOU threshold of 0.5.

As depicted in Table 5, apart from our proposed method, both the parameter count and computational complexity of the YOLOv8 series networks increase dramatically with the model’s scale. In terms of mAP for detection boxes, we noticed varied decreases in accuracy among different scale variants of the YOLO series networks. Interestingly, while YOLOV8s-pose only saw a marginal 0.22% increase in accuracy, the rest experienced declines in accuracy. For example, YOLOv8m-pose saw a substantial 756.9% increase in parameters, an 866.7% increase in computational complexity, and a 0.89% decrease in mAP. Similarly, YOLOv8l-pose experienced a 1342.8% increase in parameters, a 1913.1% increase in computational complexity, and a 0.44% decrease in mAP. Surprisingly, despite a significant 2154.0% increase in parameters and a 3042% increase in computational complexity, the largest scale YOLOv8x-pose network saw a 2.1% decrease in mAP, indicating subpar detection performance on a small-scale fish satiation dataset despite considerable resource consumption. In contrast, our proposed TinyYOLO-pose, despite a minor 0.11% decrease in mAP, saw reductions of 31.4% and 26.2% in parameter count and computational complexity, respectively. In terms of the mAP for poses, YOLOv8s-pose and YOLOv8l-pose saw decreases of 0.12% and 0.36%, respectively. Although YOLOv8m-pose and YOLOv8x-pose saw improvements of 1.3% and 0.71% in mAP, respectively, they incurred significant resource costs. Conversely, our proposed TinyYOLO-pose achieved a 0.95% increase in mAP, while reducing the parameter count and computational complexity by 31.4% and 26.2%, respectively, with its detection results shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 9a presents the detection box mAP training curves, where YOLOv8s-pose, YOLOv8m-pose, and YOLOv8l-pose demonstrate substantial fluctuations during the initial 150 epochs. In contrast, our proposed TinyYOLO-pose exhibits only minor fluctuations. As the number of training epochs increases, all network models achieve convergence by the 250th epoch. Notably, despite operating under lightweight constraints, our proposed network model attains a level of convergence comparable to YOLOv8n-pose and YOLOv8s-pose. On the other hand, YOLOv8m-pose, YOLOv8l-pose, and YOLOv8x-pose, despite their higher resource consumption, show less convergence compared to the smaller-scale models. This underscores the unsuitability of large-scale models for our fish satiety dataset, thereby validating our selection of YOLOv8n as the baseline network for enhancement.

The pose mAP training curves in Fig. 9b continue to show significant fluctuations for YOLOv8s-pose, YOLOv8m-pose, and YOLOv8l-pose, with all models achieving convergence by the 250th epoch. Importantly, our network model reaches optimal convergence with the least resource consumption. This observation is further corroborated by Fig. 10’s pose mAP training curves, which depict similar trends.

Alabation experiments

To further substantiate the efficacy of the lightweight improvement modules, RepSELAN and SPPELAN, in the pose detection network model, we performed ablation experiments. These experiments evaluated the lightweight metrics using parameters, computational complexity, mAP(B), and mAP(P), with an IOU threshold of 0.5.

As delineated in Table 6, YOLOv8n-pose served as the baseline network for comparison to validate the effectiveness of the lightweight model enhancements. The baseline network, YOLOv8n-pose, comprised 3,083,118 parameters, 8.4G computational complexity, an mAP(B) of 0.903, and an mAP(P) of 0.843. In YOLOv8n-pose-SPPELAN, we substituted the SPPF module in the baseline network with SPPELAN, resulting in a 5.11% reduction in parameters, a 1.2% decrease in computational complexity, a 0.22% drop in mAP(B), and a 1.5% improvement in mAP(P). In YOLOv8n-pose-RepSELAN, we replaced the C2f module in the baseline network with RepSELAN, leading to a 26.3% reduction in parameters, a 25% decrease in computational complexity, a 0.11% drop in mAP(B), and a 1.3% improvement in mAP(P). In our proposed TinyYOLO-pose network, we employed both SPPELAN and RepELAN to substitute the SPPF and C2f modules in the baseline network, respectively. The results indicated that the improved network, under a 31.4% reduction in parameters and a 26.2% decrease in computational complexity, experienced a slight decrease of 0.11% in mAP(B) but saw an increase of 0.95% in mAP(P).

Under the premise of lightweight constraints, our proposed SPPELAN and RepSELAN modules resulted in a slight decrease of 0.22% and 0.11% in mAP(B), respectively, but led to an increase of 1.5% and 1.3% in mAP(P), respectively.

The mAP training curves in Figs. 10a,b reveal that our proposed RepSELAN module incurs slight fluctuations during the early training epochs, but eventually converges by the 200th epoch. Under the premise of lightweight constraints, the mAP(B) training curve shows that YOLOv8n-pose-SPPFS, YOLOv8n-pose-RepSELAN, and TinyYOLO-pose all achieve convergence comparable to YOLOv8n-pose. Furthermore, the mAP(P) curve demonstrates that the convergence performance of the three improved networks surpasses that of YOLOV8n-pose.

These ablation experiments further highlight the effectiveness of the proposed lightweight enhancements in the pose detection network. Reducing the model’s parameter count and computational complexity significantly lowers hardware resource requirements, which is particularly important for resource-constrained devices, such as those used in edge computing platforms. Additionally, lightweight models improve real-time processing capabilities and reduce computational latency, enhancing the model’s responsiveness. These advancements enable the model to maintain high efficiency while addressing computational limitations, facilitating more scalable deployment in real-world applications, such as intelligent fish feeding systems or other industrial scenarios requiring rapid decision-making.

Visualization of model attention

Class Activation Mapping (CAM) is a widely used technique for visualizing the significant regions of interest that a model targets, often referred to as attention mapping. In our research, we utilize Grad-CAM++33 for receptive field visualization experiments to verify if the network’s attention is genuinely focused on the activities of the fish group. We conduct comparative visualization experiments using YOLOv8n-pose, YOLOv8n-pose-SPPELAN, YOLOv8n-pose-RepSELAN, and TinyYOLO-pose. Figure 11a–e display the original image and the visualization results under each of these models, respectively.

Figure 11b reveals that the visualization effect of the YOLOv8n-pose model is less than ideal, with the model’s attention scattered across the entire image rather than being concentrated on the fish group. As shown in Fig. 11c, YOLOv8n-pose-SPPELAN, when compared to YOLOv8-pose, focuses on fewer irrelevant details but still fails to concentrate on the fish bodies. Some images only focus on individual fish, resulting in a significant number of fish being overlooked. As depicted in Fig. 11d, after replacing the original C2f structure with the RepSELAN structure, YOLOv8n-pose-RepSELAN accurately focuses on most fish bodies, truly centering its attention on the fish group. In Fig. 11e, our proposed TinyYOLO-pose demonstrates significant advantages. Compared to YOLOv8n-pose-RepSELAN, the fish bodies are darker, indicating that attention is further concentrated on individual fish and the fish group. This suggests that our network is more effective at capturing meaningful semantic information and exhibits robust feature extraction capabilities.

However, as shown in Fig. 11e, even though our proposed TinyYOLO-pose network model accurately learns about individual fish and the fish group, it can still be observed that our network model pays some attention to the background information of the breeding bucket and water splashes. This highlights the importance of using the pose detection network to obtain individual fish information and group information, thereby filtering out redundant background information.

Comparison of different action recognition algorithms

The second stage of our network incorporates the GCN classification network. The confusion matrix of the GCN classification network, presented in Fig. 12, demonstrates that our network attains 100% accuracy for classifying satiety levels of 20% and 100%. For the 40% satiety level, the classification accuracy is 86.21%, with 13.79% of the satiety levels misclassified as 80% satiety. The classification accuracy for the 60% satiety level stands at 96.57%, with 3.43% of the samples misclassified as 80% satiety. For the 80% satiety level, the classification accuracy is 93.1%, with 6.9% of the samples misclassified as 40% satiety. This suggests a degree of similarity between the characteristics of fish groups at 40% and 80% satiety levels, leading to some instances of cross-category misclassification.

To further substantiate the superior performance of our proposed two-stage network in satiety classification tasks, we conducted a comparison with a series of classic network models renowned for their efficacy in image and video classification domains, using our satiety dataset.

Our proposed method achieves a final classification accuracy of 98.1% on the satiety dataset. Given our model’s objective of facilitating real-time determination of fish satiety in industrial aquaculture and its requirement for easy deployment on hardware devices, we also prioritize the model’s size while maintaining accuracy. As indicated in Table 7, although ShuffleNetv234 and DenseNet35 have relatively small parameter counts, their accuracies are only 53.7% and 91.0%, respectively. GoogleNet36 and MobileVitv337 achieve slightly higher accuracies compared to our method, by 1% and 0.5% respectively, but necessitate significantly larger computational resources, with parameter counts 1.6 times and 17.5 times that of our method, respectively. Conversely, C2D38, ResNet3439, and EfficientNetv240 not only possess higher parameter counts than our network but also exhibit lower accuracy.

The comparative experiments unequivocally demonstrate that our network model, while having a lower parameter count, achieves higher accuracy, thereby enabling precise recognition while consuming minimal hardware resources.

Dissussion

As industrial aquaculture evolves, the development of an accurate and efficient method for intelligent fish feeding becomes critical for reducing feed and labor costs, and enhancing fish welfare. In this study, we have assembled a dataset that quantifies fish feeding behavior and proposed a two-stage fish satiety discrimination model. Notably, existing studies often rely on qualitatively determined dataset labels, which, despite the significant cost of training and inference, only yield qualitative outcomes. To address this, we conducted a satiety analysis by observing fish behavior and feed consumption, thereby identifying the optimal feeding strategies. Satiety levels were quantified based on the feed amount per feeding session, resulting in a dataset with satiety as a quantitative label. Further, current computer vision-based methods typically adhere to a paradigm that takes images or videos as input, directly outputting classification results through deep learning networks. However, these approaches often overlook the intrinsic feeding behaviors of fish, with the abundant redundant information in images potentially leading to the learning of incorrect causal relationships, thereby limiting model accuracy. To address this challenge, a two-stage network is proposed. In the first stage, object detection and pose estimation are employed to extract individual fish pose information and the distribution of the fish school, effectively eliminating redundant image data. Given the robust capability of graph data to learn feature embeddings from neighboring nodes and accurately represent fish feeding behaviors, pose and distribution information were utilized to construct graph data. Subsequently, a graph convolutional classification network was designed, achieving an accuracy of 98.1%, thus validating the feasibility of the proposed approach. In addition, considering the importance of real-time discrimination and reducing hardware resource consumption, lightweight RepSELAN and SPPFS modules were developed, leading to the TinyYOLO-pose model.

Despite the high recognition accuracy achieved by our proposed two-stage fish satiety classification network, some samples of 40% satiety and 80% satiety were mistakenly identified as each other. This could be attributed to the high similarity of their sample features in spatial dimensions, suggesting the need to consider temporal features in the future to further enhance the model’s classification accuracy. Meanwhile, our graph data used a fully connected method to characterize the overall distribution and spatial relationships of fish groups. While this method accurately describes the information of fish groups, it results in all graph data having similar topological structures. Therefore, future work will focus on optimizing graph data construction methods to increase the irregularity of graph data and fully harness the powerful representation capabilities of graph data in describing fish behavior.

Conclusion

This study divided the dataset based on the differences in fish feeding behavior under varying satiation states, resulting in a fish feeding behavior dataset quantified by satiation levels. Building on this, we introduced a novel two-stage approach for fish satiety classification. Our primary contributions include the development of the lightweight TinyYOLO-pose network, which efficiently captures fish spatial and pose information while reducing computational complexity. Additionally, we constructed graph data using pose and distribution information, accurately representing intrinsic feeding behaviors. Furthermore, we designed a graph convolutional classification network that achieved an impressive accuracy of 98.1%, demonstrating the effectiveness of our approach. These innovations provide a robust framework for intelligent fish feeding systems, balancing accuracy and resource efficiency.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Atoum, Y. & Srivastava, S. Automatic feeding control for dense aquaculture fish tanks. IEEE. Signal. Process. Lett. 22 (8), 1089–1093. https://doi.org/10.1109/lsp.2014.2385794 (2015).

Adimulam, R. P., Kokkiligadda, V. & Polagani, A. Automatic feed dispenser for aquaculture using arduino technology. In 2024 3rd International Conference for Advancement in Technology (ICONAT), 1–5 (2024).

Morilla, N. B., Olsem, A. A. & Vergara, E. M. Study of cloud-based monitoring and feeding system for smart aquaculture farming in infanta, Quezon. In 2023 IEEE 5th Eurasia Conference on IOT, Communication and Engineering (ECICE), 259–264 (2023).

Ragab, S. et al. Overview of aquaculture artificial intelligence (AAI) applications: enhance sustainability and productivity, reduce labor costs, and increase the quality of aquatic products. Ann. Anim. Sci. (2024).

Roh, H. et al. Overfeeding-induced obesity could cause potential immuno-physiological disorders in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Anim. Open Access J. MDPI. 10 (2020).

Hancz, C. Feed efficiency, nutrient sensing and feeding stimulation in aquaculture: A review. (2020).

Cui, M., Liu, X., Zhao, J., Sun, J., Lian, G., Chen, T., Plumbley, M et al. Fish feeding intensity assessment in aquaculture: A new audio dataset AFFIA3K and a deep learning algorithm. In 2022 IEEE 32nd International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing (MLSP), 1–6 (2022).

Ye, Z. et al. Behavioral characteristics and statistics-based imaging techniques in the assessment and optimization of tilapia feeding in a recirculating aquaculture system. Trans. ASABE. 59, 345–355 (2016).

Zhou, C. et al. Near-infrared imaging to quantify the feeding behavior of fish in aquaculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 135, 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2017.02.013 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Measuring feeding activity of fish in RAS using computer vision. Aquac. Eng. 60, 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2014.03.005 (2014).

Borchers, M. R. et al. Machine-learning-based calving prediction from activity, lying, and ruminating behaviors in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 100 (7), 5664–5674. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-11526 (2017).

Ubiña, N., Cheng, S., Chang, C. & Chen, H. Evaluating fish feeding intensity in aquaculture with convolutional neural networks. Aquac. Eng. (2021).

Du, Z. et al. Feeding intensity assessment of aquaculture fish using Mel Spectrogram and deep learning algorithms. Aquac. Eng. (2023).

Qin, Y., Mo, L., Li, C. & Luo, J. Skeleton-based action recognition by part-aware graph convolutional networks. Visual Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00371-019-01644-3 (2019).

Sohaib, M. S., Akbar, H., Nawaz, T. & Elahi, H. Body-Pose-Guided action recognition with convolutional long short-term memory (LSTM) in aerial videos. Appl. Sci. 13 (16), 9384–9384. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13169384 (2023).

Sun, R., Zhang, Q., Luo, C., Guo, J. & Chai, H. Human action recognition using a convolutional neural network based on skeleton heatmaps from two-stage pose estimation. Biomim. Intell. Rob. 2 (3), 100062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.birob.2022.100062 (2022).

Fu, H., Gao, J. & Liu, H. Human pose estimation and action recognition for fitness movements. Comput. Graph. 116, 418–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2023.09.008 (2023).

Hua, Z., Wang, Z., Xu, X., Kong, X. & Song, H. An effective PoseC3D model for typical action recognition of dairy cows based on skeleton features. Comput. Electron. Agric. 212, 108152–108152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2023.108152 (2023).

Ge, Z., Liu, S., Wang, F., Li, Z. & Sun, J. Y. O. L. O. X. Exceeding YOLO series in 2021. arXiv:2107.08430 [cs] 2021.

Phillips, M. J. Behaviour of rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri richardson, in marine cages. Aquac. Res. 16 (3), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.1985.tb00311.x (1985).

Taheri, A., Gimpel, K. & Berger-Wolf, T. Y. Learning to represent the evolution of dynamic graphs with recurrent models. https://doi.org/10.1145/3308560.3316581 (2019).

Rossi, E. et al. Temporal Graph Networks for Deep Learning on Dynamic Graphs (Cornell University, 2020).

Zeng, D., Zhao, C. & Quan, Z. CID-GCN: an effective graph convolutional networks for Chemical-Induced disease relation extraction. Front. Genet. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.624307 (2021).

Huang, J. et al. Recognizing fish behavior in aquaculture with graph convolutional network. Aquac. Eng. 98, 102246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2022.102246 (2022).

Khan, H. et al. Visionary vigilance: optimized YOLOV8 for fallen person detection with large-scale benchmark dataset. Image Vis. Comput. 149, 105195 (2024).

Xie, S., Girshick, R., Dollár, P., Tu, Z. & He, K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. IEEE Xplore https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.634

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.1556

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 37 (9), 1904–1916. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpami.2015.2389824 (2015).

Khan, H., Usman, M. T., Rida, I. & Koo, J. Attention enhanced machine instinctive vision with human-inspired saliency detection. Image Vis. Comput. 152, 105308 (2024).

Wang, C. Y. et al. CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW). https://doi.org/10.1109/cvprw50498.2020.00203 (2020).

Wang, C. Y., Liao, H. Y. M. & Yeh, I-H. Designing network design strategies through gradient path analysis. arXiv (Cornell University) (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2211.04800

Khan, H. et al. A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring. Nanotechnol. Rev. (2024).

Chattopadhay, A., Sarkar, A., Howlader, P., Balasubramanian, V. N. & Grad -CAM++: Generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. In IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV) 2018. https://doi.org/10.1109/wacv.2018.00097 (2018).

Ma, N., Zhang, X., Zheng, H. T. & Sun, J. ShuffleNet V2: Practical guidelines for efficient CNN architecture design. arXiv:1807.11164 [cs] 2018.

Huang, G., Liu, Z. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/1608.06993.

Szegedy, C. et al. Going Deeper with Convolutions. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.4842.

Wadekar, S. N. & Chaurasia, A. MobileViTv3: Mobile-Friendly vision transformer with simple and effective fusion of local, global and input features. arXiv.org. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2209.15159.

Wang, X., Girshick, R., Gupta, A. & He, K. Non-Local neural networks. 2018 IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2018.00813 (2018).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/1512.03385

Tan, M. & Le, Q. V. EfficientNetV2: smaller models and faster training. arXiv:2104.00298 [cs] 2021.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFD2400100), the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-49), and the Dalian Key Laboratory of Intelligent Detection and Diagnostic Technology for Equipment [grant number DLKL-201904].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization. K.C.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing. Y.D.: Data curation, writing—review and editing. G.F.: Conceptualization, formal analysis. Y.W.: Investigation, formal analysis. H.P.: Investigation, resources. Y.L.: Supervision, resources. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, S., Cai, K., Dong, Y. et al. Fish feeding behavior recognition via lightweight two stage network and satiety experiments. Sci Rep 15, 30025 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15241-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15241-z