Abstract

Early detection plays a critical role in reducing lung cancer mortality. DNA methylation biomarker assay based on cell-free DNA (cfDNA) is a promising method for early detection of lung cancer. In this study, we aimed to develop a prediction model based on cfDNA methylation biomarkers and cfDNA concentration for early detection of lung cancer. We recruited 179 lung cancer patients and 82 healthy controls, and assessed the methylation level of four DNA methylation biomarkers (PTGER4, RASSF1A, SHOX2, and H4C6) and cfDNA concentration. The LASSO and Boruta algorithms were then used to select the best performing variables, and a lung cancer prediction model was constructed using the generalized linear models (GLMs) algorithm. The model was then validated in an independent set. Finally, the AUC for this model in the training and validation cohorts was 0.8012 and 0.8436, respectively. The accuracy of the model was significantly higher than the individual biomarkers. These results demonstrated that this panel based on four methylation markers and cfDNA concentration was effective in lung cancer detection, and may provide clinical utility in combination with current lung cancer detection techniques to improve the diagnosis of lung cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with 1.8 million deaths caused by lung cancer in 2022, accounting for 18.1% of all cancer-related deaths1. The five-year survival rate for lung cancer patients is only 20%, and the exceptionally high mortality of lung cancer can be attributed to late diagnosis2. In contrast, the five-year survival rate for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with early detected can reach 70%~90%3. Nevertheless, approximately 75% of NSCLC cases are diagnosed at advanced stages2. So, early detection plays a critical role in reducing lung cancer mortality.

Current diagnostic methods for lung cancer include serum biomarkers, sputum cytology, X-rays, and computed tomography (CT) scans4. Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) is a reliable tool for early lung cancer screening, which decreased the mortality rate by 20% in high-risk populations5,6. However, the high false-positive rate and overdiagnosis associated with LDCT limit its diagnostic accuracy, and 96.4% of these pulmonary nodules were ultimately confirmed to be false positives7. Serum biomarkers for lung cancer diagnosis, such as CEA, are extensively applied in clinical, however, the specificity of CEA is low, with only 61.9% of NSCLC patients detected with abnormal CEA serum levels8. Consequently, there is an urgent demand for accurate and non-invasive diagnostic tools to improve the detection of early lung cancer.

Non-invasive detection of genomic and epigenomic alterations in circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) offers promising avenues for early lung cancer detection9,10,11. cfDNA is free DNA in the blood originating from normal or tumor cells, and the concentration of cfDNA is significantly elevated in tumor patients12,13,14. cfDNA encapsulates the genetic and epigenetic variations specific to tumors, such as nucleic acid mutations and methylation variations. Notably, these alterations can be detected in cfDNA even during precancerous stages and early stages of tumor, particularly DNA methylation variations15,16. DNA methylation is an important epigenetic modification that plays a key role in cell development, gene expression, and genome stability17. DNA methylation variations are present in almost all tumors, with global hypomethylation and promoter hypermethylation being widely recognized as hallmarks of various tumors18,19. cfDNA methylation is a potential biomarker for early cancer screening, with several diagnostic assays based on DNA methylation biomarkers already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration20.

The cfDNA concentration, and DNA methylation status of prostaglandin E receptor 4 gene (PTGER4), ras-associated structural domain family 1 A (RASSF1A), short stature homology cassette gene 2 (SHOX2), and H4 clustered histone 6 (H4C6) have been identified as valuable biomarkers for lung cancer diagnosis in several studies21,22,23,24. However, the combined detection of these five biomarkers in lung cancer diagnosis has hardly been reported. Considering the complex tumor microenvironment and heterogeneity during lung cancer development, single circulating biomarker may lack sufficient diagnostic accuracy. In this study, we employed qPCR to examine the promoter methylation of SHOX2, RASSF1A, PTGER4, and H4C6, along with cfDNA concentrations, in a total of 261 plasma samples from lung cancer patients and healthy controls. This approach aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the combined use of these five biomarkers in lung cancer.

Materials and methods

Patients recruited

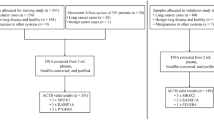

This study recruited 179 lung cancer patients and 82 healthy controls from the First Affiliated Hospital of USTC. All lung cancer patients were histologically confirmed, and peripheral blood samples were collected before treatment. Control samples were recruited during routine physical examinations, excluding participants with a history of cancer. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The First Affiliated Hospital of USTC by relevant ethical guidelines, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sample collection and storage

Peripheral blood was collected using EDTA anticoagulant tubes, stored at 4 °C after collection, and processed within 4 h. Whole blood was centrifuged at 1,600 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was then centrifuged again at 16,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was aspirated into a 2 mL EP tube and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction.

DNA isolation and bisulfite conversion

Cell-free DNA was extracted using the Magnetic Serum/Plasma DNA Maxi Kit (Cat# DP710, TIANGEN Biotechnology, Beijing, China) from 4 mL plasma according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and the final elution volume was 55 µL. cfDNA concentrations were detected using the Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay Kit (Cat# Q33231, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). cfDNA bisulfite conversion using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Cat#D5005, ZYMO, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cfDNA was isolated and purified from 4mL of plasma using magnetic beads, and converted the unmethylated cytosine residue to uracil residue in DNA by a bisulfite reaction. Finally, the purified bisulfite-modified DNA was eluted in 10.5 µL with M-Elution Buffer.

DNA methylation analysis

DNA methylation was analysed using the Quantitative PCR (qPCR). The total reaction volume of each PCR reaction mixture was 15 µL, including 7.5 µL of reaction buffer, 2.5 µL of primer mixture, and 5 µL of bisulfite-modified eluted DNA. qPCR was performed on a 96-well plate using the Applied Biosystems 7500 (ABI-7500) platform (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). β-Actin (ACTB) was used as a standardized endogenous control. Amplifications were carried out using the following profile: 98 °C for 5 min, followed by 50 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 58 °C for 35 s, and 40 °C for 5 s. The primers used for qPCR are shown in Table 1. All samples were within the range of the cycle threshold (Ct) values for ACTB. For each gene, a relative methylation value was modified as follows:

Methylationgene =\(\:\frac{1}{{2}^{{\Delta\:}\text{C}\text{T}}}\),

where ΔCTgene = CTgene – CTACTB.

Machine learning algorithm for feature selection

LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) is a variable selection method proposed in 1996, which can remove unimportant variables by penalizing the magnitude of the coefficients. The Boruta algorithm is another method used to identify the most important features. Compared to traditional regression methods, LASSO and Boruta can better select the features that are most closely related to the disease. In this study, we performed LASSO and Boruta feature selection using the glmnet package25 and Boruta package26 to filter and identify the most relevant features, respectively. LASSO analysis was performed using the glmnet package with parameters set as family = “binomial”, nfolds = 3, type.measure = “class”. Boruta analysis was performed using the Boruta package with parameters configured as doTrace = 2, maxRuns = 500, getImp = getImpRfZ.

Minimizing confounding bias

To minimize the impact of confounding factors, we employed the hold-out method to randomly select 80% of the samples from the experimental group as the training set. This process was repeated 100 times to mitigate the influence of outlier samples. Propensity Score Matching (PSM) is a technique designed to alleviate the interference caused by extraneous biases and irrelevant variables by matching treated subjects with one or more control subjects based on similar propensity scores. To further reduce the influence of age and other irrelevant variables, we implemented a 1:2 PSM using the R MatchIt package between the lung cancer and non-cancer groups. The propensity scores were generated using a logistic regression model to identify matched samples.

Lung cancer detection model development

Generalized linear models (GLMs) extend traditional linear models by accommodating response variables with error distribution models beyond the normal distribution. We developed the GLM using the train function from the caret package, with the following parameters: method = “repeatedcv”, number = 10, repeats = 5, summaryFunction = twoClassSummary, classProbs = TRUE.

Statistical analysis

R (version 4.1.1) and RStudio were used for statistical analysis. The Mann–Whitney U–test was used to compare the differences between lung cancer samples and control samples, and the Kruskal-Wallis test for multiple groups of continuous variables. p < 0.05 was considered significant. The receiver operating characteristic curves, AUC value, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were calculated using the pROC package27. The cut-off values were determined using the Youden index. The DeLong test was used to compare the AUCs of different models, p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient information and cfDNA concentration distribution

In this study, we collected plasma samples from 82 non-cancer controls and 179 lung cancer patients. The samples were divided into two cohorts: 184 samples for the training set and 77 samples for the validation set. Detailed characteristics are presented in Table 2. Previous studies have shown that cfDNA concentrations were higher in cancer patients and tend to increase with disease progression. In this study, cfDNA concentration was significantly higher in the lung cancer group (Fig. 1A), and stage Tis (Tumor in situ) was lower than the other stages with a tendency to increase with disease progression, although no significant difference was observed between stages I, II and higher stages (Fig. 1B). We then classified the lung cancer samples into lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous carcinoma (LUSC), and no significant difference in cfDNA concentration was observed between the two subtypes (Fig. 1C). Age is a known risk factor for lung cancers, patients were divided by median age to analyze the association between cfDNA concentrations and age. However, there was no significant variation in cfDNA concentrations between different age groups (Fig. 1D). There was also no significant difference in cfDNA concentration between women and men (Fig. 1E). These findings indicate that cfDNA concentration in lung cancer is associated with disease progression, but is independent of age, gender, and lung cancer subtype.

Distribution of cfDNA concentration among different groups. (A) The distribution of cfDNA concentration in lung cancer and non-cancer controls. (B) The distribution of cfDNA concentration in different stages. (C) The distribution of cfDNA concentration in different subtype. (D) The distribution of cfDNA concentration in different age subgroups. (E) The distribution of cfDNA concentration in different gender patients.

Diagnostic accuracy of the four methylation biomarkers for lung cancer detection

To analyze the methylation variations of the four methylated biomarkers in lung cancer, we examined the methylation levels of these four methylated biomarkers using the qPCR method. The results showed that the methylation levels of two markers were significantly different between the lung cancer group and the control group, with SHOX2 being hypermethylated and PTGER4 being hypomethylated in the lung cancer group (Fig. 2A and B), but RASSF1A and H4C6 showed no significant differences between the lung cancer group and the control group (Fig. 2C and D). To determine the diagnostic values of the four methylation biomarkers, we performed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to evaluate the capability for the distinguishment between the lung cancer group and the control group. The area under the curve (AUC) values for distinguishing lung cancer from non-cancer controls for SHOX2, PTGER4, RASSF1A, and H4C6 were 0.7462, 0.5967, 0.5506, and 0.5094, respectively (Fig. 3A and D). Additionally, cfDNA concentration was significantly elevated in lung cancer, we also calculated the AUC value of cfDNA concentration in lung cancer diagnosis. The results showed that the AUC value was 0.6017, indicating that cfDNA concentration also has the potential for lung cancer detection (Fig. 3E).

The methylation levels distribution between lung cancer and non-cancer group. (A) The methylation levels of SHOX2 between lung cancer and non-cancer group. (B) The methylation levels of PTGER4 between lung cancer and non-cancer group. (C) The methylation levels of RASSF1A between lung cancer and non-cancer group. (D) The methylation levels of H4C6 between lung cancer and non-cancer group.

Diagnostic accuracy of the cfDNA concentration and four gene methylation in training set. (A) ROC curves of SHOX2 methylation in lung cancer detection. (B) ROC curves of PTGER4 methylation in lung cancer detection. (C) ROC curves of RASSF1A methylation in lung cancer detection. (D) ROC curves of H4C6 methylation in lung cancer detection. (E) ROC curves of cfDNA concentration in lung cancer detection.

Development of a prediction model based on the methylation biomarkers and cfDNA concentration for lung cancer diagnosis

To improve the accuracy of lung cancer diagnosis, we employed machine learning methods to evaluate the performance of the four methylated biomarkers and cfDNA concentration panels in lung cancer diagnosis. First, we employed the Boruta and LASSO algorithms to assess the importance value of cfDNA concentration and the four methylation biomarkers in the training set. The results indicated that all five biomarkers showed good diagnostic potential for lung cancer (Fig. 4A and B). Next, we developed a lung cancer risk model using the generalized linear models algorithm, with the following equation:

Models developed for lung cancer detection. (A) The importance scores of the cfDNA concentration and four gene methylation based on the Boruta algorithm. The importance score reflects the relative contribution of each feature to the model’s predictive performance, with higher values indicating greater significance. (B) Non-zero coefficient were screened using ten-fold cross-validation via minimum λ value in LASSO algorithm. The binomial deviance serves as the cross-validation error metric, where smaller values indicate better model performance. λ directly controls the penalty strength, as λ increases, shrinking more coefficients to zero. (C) ROC curves of the lung cancer detection models in training set. (D) ROC curves of the 3-feature model and 5-feature model.

The probability of lung cancer = \(\:\frac{{e}^{x}}{1+{e}^{x}}\),

where e is the base of the natural logarithm, x = 6.4667 + 0.0493 × cfDNA concentration − 0.1516 × MethylationPTGER4 − 0.2220 × MethylationSHOX2 − 0.0381 × MethylationH4C6 − 0.0155 × MethylationRASSF1A. We then evaluated the performance of the model in the training set, which had an AUC of 0.8012 in lung cancer diagnosis, demonstrating a good potential for lung cancer detection (Fig. 4C). Since RASSF1A and H4C6 methylation showed no statistically significant differences between non-cancer and lung cancer samples, we excluded these two genes and constructed a 3-feature model using the same methodology. The results showed that the 3-feature model achieved an AUC of 0.7875, which was lower than that of the original 5-feature model (Fig. 4D). These findings suggest that RASSF1A and H4C6 methylation can enhance the diagnostic accuracy of the model for lung cancer detection.

Validation of the prediction model in an independent cohort

To evaluate the effectiveness of our models, we tested these models in the independent validation set. We calculated the lung cancer risk of each sample and evaluated the performance of the model in the validation set. The results were consistent with the training set, with an AUC of 0.8436 (95% CI: 0.7565–0.9306), and the sensitivity and specificity were 77.36% and 91.67%, respectively (Fig. 5A). To further assess the robustness of the model and to ensure its independence from clinical variables, we undertook clinical subgroup analyses on the training and validation sets. We analyzed the distribution of risk scores across different subgroups based on age, gender, stage, and histological subtype, and the results showed a significant association with age in the lung cancer group, with the older group exhibiting higher tumor risk compared to younger patients (Fig. 5B). No significant differences in risk scores were observed between different gender groups (Fig. 5C). However, notable variations emerged when analyzing different subtypes and stages: the risk scores of the LUAD group were significantly lower than the LUSC group (Fig. 5D), while early-stage patients had markedly lower scores than advanced-stage patients (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, a progressive increase in risk scores was observed with ascending tumor stages. In summary, these results demonstrate that the model has strong potential for lung cancer detection.

Evaluate of the lung cancer detection model in an independent validation set. (A) ROC curves of the lung cancer detection models in validation set. (B) The distribution of model prediction scores in different age groups. (C) The distribution of model prediction scores in different gender. (D) The distribution of model prediction scores in different subtype. (E) The distribution of model prediction scores in different stages.

Discussion

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, which is mainly attributed to the lack of obvious clinical symptoms and effective screening methods in the early stages of lung cancer, leading to advanced diagnosis. Early diagnosis is the key to reducing lung cancer mortality and underscoring the clinical significance of the development of accurate non-invasive diagnostic methods. In this study, we detected four methylation biomarkers and cfDNA concentrations in plasma and constructed a diagnostic model for lung cancer. The AUC for this model in the training and validation cohorts was 0.8012 and 0.8436, respectively, which showed high sensitivity and specificity for lung cancer diagnosis.

Plasma cfDNA mainly originates from the hematopoietic system, but the proportion of cellular sources varies considerably in various pathological conditions and body fluids28. In healthy individuals, 55% of plasma cfDNA comes from leukocytes, 30% from erythroid progenitor cells, and 10% from vascular endothelial cells29. In cancer patients, tumor-derived cfDNA ranges from 0.01 to 90% of total cfDNA, with the proportion increasing with tumor progression30,31. Previous studies have shown that cfDNA concentration is a potential early screening marker for lung cancer. Qi et al. achieved an AUC of 0.8777 for gastric cancer detection using cfDNA concentration32and Mirtavoos-Mahyari et al. achieved an AUC of 0.98 for differentiating the recurrence probability of lung cancers33. In this study, although the diagnostic performance of cfDNA concentration was better than most of the methylation markers with an AUC of 0.6467, the accuracy was lower than the previous study, probably because the pathological stage of most patients was stage I, and the proportion of tumor-derived cfDNA in early-stage patients was low.

cfDNA methylation plays a critical role in early tumorigenesis and is a promising biomarker for cancer early detection. In this study, we analyzed the methylation level of SHOX2, RASSF1A, PTGER4, and H4C6 genes, which have shown significant diagnostic potential for lung cancer in previous studies. SHOX2 has shown excellent results in the screening and diagnosis of lung cancer patients and has been approved by the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA)22,34. Christoph Kneip et al. demonstrated that plasma-based SHOX2 DNA methylation could be used as a biomarker to distinguish between malignant lung disease and controls at a sensitivity of 60% and a specificity of 90%. Cancer in patients with stages II (72%), III (55%), and IV (83%) was detected at a higher sensitivity when compared with stage I patients. Small cell lung cancer (80%) and squamous cell carcinoma (63%) were detected at the highest sensitivity when compared with adenocarcinomas34. RASSF1A is a tumor suppressor gene whose was hypermethylated in 63% of NSCLC patients, and it’s one of the common epigenetic inactivation events in human cancers35. PTGER4 belongs to the G-protein-coupled receptor family that influences cellular physiological and pathological processes by activating endogenous G proteins to transmit downstream signals36. The H4C6 gene encodes a replication-dependent histone and is hypermethylated in various cancers, including lung cancer. Dong et al. demonstrated that H4C6 methylation accurately distinguished lung cancer patients from those with benign pulmonary diseases, with an AUC of 0.98, specificity of 96.7% and sensitivity of 87.0%21. In our study, the AUCs for SHOX2, PTGER4, RASSF1A, and H4C6 methylation in lung cancer diagnosis were 0.7462, 0.5967, 0.5506, and 0.5094, respectively. Among these, only SHOX2 exhibited satisfactory diagnostic accuracy, which might be related to the sample type and pathological stage. 84.9% of the collected 179 lung cancer samples we collected were stage Tis and stage I, and early-stage patients had lower cfDNA levels. Additionally, the detection performance of DNA methylation markers varied significantly across the sources of samples. For example, the AUC of SHOX2 methylation for diagnosing lung cancer in serum, pleural fluid, and bronchial lavage fluid was 0.62, 0.70, and 0.94, respectively37. The performance in serum was lower than that in pleural fluid and bronchial lavage fluid, but pleural fluid and bronchial lavage fluid were unavailable in most of the patients, while serum was available in all patients.

To address the suboptimal performance of single biomarkers, multi-biomarker panels may offer a viable solution. Previous studies have demonstrated that multi-marker panels significantly improve the efficiency of cancer diagnosis. Weiss et al. achieved an AUC of 0.88 for lung cancer diagnosis using SHOX2 and PTGER4 methylation38. Similarly, Wei et al. reported an AUC of 0.938 when combining PTGER4, RASSF1A, and SHOX2 methylation, which is better than the single-marker assay39. In the study by Jiaping Zhao et al., the AUC values for distinguishing lung adenocarcinoma from healthy controls for SHOX2 and RASSF1A methylation were 0.751 and 0.747, respectively. Notably, the combined methylation panel of both biomarkers yielded an AUC of 0.81440. In the study by Wenhai Huang et al.41 the AUC values for distinguishing lung cancer from benign lung diseases for SHOX2 and PTGER4 methylation were 0.8514 and 0.8466, respectively, and the combined methylation panel of both biomarkers yielded an AUC of 0.921. In this study, the combined analysis of SHOX2, PTGER4, RASSF1A, and H4C6 methylation significantly enhanced diagnostic accuracy compared to individual markers (0.8012 VS 0.7462, 0.5967, 0.5506, and 0.5094).

Limitations existed in this study. First, the sample size was small, a large sample size is needed in further studies to confirm the results. Second, samples were limited to healthy individuals and patients diagnosed with lung cancer, the absence of non-tumor cancer pulmonary disease samples, combined with incomplete data on lifestyle factors and comorbidities, limits our ability to evaluate the model’s performance in non-malignant pulmonary conditions or high-risk populations. Finally, since RASSF1A and H4C6 methylation levels are elevated in multiple cancer types, our model may lack specificity for tumor localization and could potentially yield false-positive results for other cancers.

Conclusions

In summary, plasma cfDNA concentration and methylation level of SHOX2, RASSF1A, PTGER4, and H4C6 demonstrated high diagnostic efficacy for lung cancer. This non-invasive assay based on the four methylation markers and cfDNA concentration has potential clinical applications and can be used alone or in combination with current diagnostic methods to improve the overall efficiency of lung cancer diagnosis.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin. 74 (3), 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Walters, S. et al. Lung cancer survival and stage at diagnosis in australia, canada, denmark, norway, Sweden and the UK: a population-based study, 2004–2007. Thorax 68 (6), 551–564. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202297 (2013).

Nesbitt, J. C., Putnam, J. B., Walsh, G. L., Roth, J. A. & Mountain, C. F. Survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 60 (2), 466–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4975(95)00169-L (1995).

Wolf, A. M. D. et al. Screening for lung cancer: 2023 guideline update from the American cancer society. Cancer J. Clin. 74 (1), 50–81. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21811 (2024).

Lancaster, H. L., Heuvelmans, M. A. & Oudkerk, M. Low-dose computed tomography lung cancer screening: clinical evidence and implementation research. J. Intern. Med. 292 (1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13480 (2022).

Wood, D. E. et al. Lung cancer screening, version 3.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 16 (4), 412–441. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2018.0020 (2018).

null null. Reduced Lung-Cancer mortality with Low-Dose computed tomographic screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 365 (5), 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 (2011).

Niu, L. et al. Tumor-derived Exosomal proteins as diagnostic biomarkers in non‐small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 110 (1), 433–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13862 (2019).

Li, P. et al. Liquid biopsies based on DNA methylation as biomarkers for the detection and prognosis of lung cancer. Clin. Epigenet. 14 (1), 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-022-01337-0 (2022).

Fernandez-Cuesta, L. et al. Identification of Circulating tumor DNA for the early detection of Small-cell lung cancer. eBioMedicine 10, 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.06.032 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. Multidimensional Cell-Free DNA fragmentomic assay for detection of Early-Stage lung cancer. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 207 (9), 1203–1213. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202109-2019OC (2023).

Thierry, A. R., El Messaoudi, S., Gahan, P. B., Anker, P. & Stroun, M. Origins, structures, and functions of Circulating DNA in oncology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 35 (3), 347–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-016-9629-x (2016).

Schwarzenbach, H., Stoehlmacher, J., Pantel, K. & Goekkurt, E. Detection and monitoring of Cell-Free DNA in blood of patients with colorectal cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1137 (1), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1448.025 (2008).

Tivey, A., Church, M., Rothwell, D., Dive, C. & Cook, N. Circulating tumour DNA — looking beyond the blood. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19 (9), 600–612. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-022-00660-y (2022).

Van Der Pol, Y. & Mouliere, F. Toward the early detection of cancer by decoding the epigenetic and environmental fingerprints of Cell-Free DNA. Cancer Cell. 36 (4), 350–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2019.09.003 (2019).

Keller, L., Belloum, Y., Wikman, H. & Pantel, K. Clinical relevance of blood-based ctdna analysis: mutation detection and beyond. Br. J. Cancer. 124 (2), 345–358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01047-5 (2021).

Jones, P. A. & Baylin, S. B. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3 (6), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg816 (2002).

Roy, D. & Tiirikainen, M. Diagnostic power of DNA methylation classifiers for early detection of cancer. Trends Cancer. 6 (2), 78–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2019.12.006 (2020).

Laird, P. W. The power and the promise of DNA methylation markers. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 3 (4), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1045 (2003).

Locke, W. J. et al. DNA methylation cancer biomarkers: translation to the clinic. Front. Genet. 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.01150 (2019).

Dong, S. et al. Histone-Related genes are hypermethylated in lung cancer and hypermethylated HIST1H4F could serve as a Pan-Cancer biomarker. Cancer Res. 79 (24), 6101–6112. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-1019 (2019).

Schmidt, B. et al. SHOX2 DNA methylation is a biomarker for the diagnosis of lung cancer based on bronchial aspirates. BMC Cancer. 10 (1), 600. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-600 (2010).

Hu, H., Zhou, Y., Zhang, M. & Ding, R. Prognostic value of RASSF1A methylation status in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Biomarkers 24 (3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354750x.2019.1583771 (2019).

Schotten, L. M. et al. DNA methylation of PTGER4 in peripheral blood plasma helps to distinguish between lung cancer, benign pulmonary nodules and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Eur. J. Cancer. 147, 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2021.01.032 (2021).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Soft. 33 (1). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v033.i01 (2010).

Kursa, M. B. & Rudnicki, W. R. Feature selection with the Boruta package. J. Stat. Soft. 36 (11). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i11 (2010).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-77 (2011).

Khier, S. & Lohan, L. Kinetics of Circulating cell-free DNA for biomedical applications: critical appraisal of the literature. Future Sci. OA. 4 (4), FSO295. https://doi.org/10.4155/fsoa-2017-0140 (2018).

Moss, J. et al. Comprehensive human cell-type methylation atlas reveals origins of Circulating cell-free DNA in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 5068. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07466-6 (2018).

Bettegowda, C. et al. Detection of Circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl Med. 6 (224), 224ra24. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094 (2014).

Ignatiadis, M., Sledge, G. W. & Jeffrey, S. S. Liquid biopsy enters the clinic — implementation issues and future challenges. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18 (5), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-00457-x (2021).

Qi, J. et al. Plasma cell-free DNA methylome-based liquid biopsy for accurate gastric cancer detection. Cancer Science https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.16284

Mirtavoos-Mahyari, H. et al. Circulating free DNA concentration as a marker of disease recurrence and metastatic potential in lung cancer. Clin. Transl Med. 8, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40169-019-0229-6 (2019).

Kneip, C. et al. SHOX2 DNA methylation is a biomarker for the diagnosis of lung cancer in plasma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 6 (10), 1632–1638. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e318220ef9a (2011).

Burbee, D. G. et al. Epigenetic inactivation of RASSF1A in lung and breast cancers and malignant phenotype suppression. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 93 (9), 691–699. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/93.9.691 (2001).

Yu, S. et al. Association of PTGER4 and PRKAA1 genetic polymorphisms with gastric cancer. BMC Med. Genomics. 16 (1), 209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-023-01645-1 (2023).

Liu, Q., Wang, S., Pei, G., Yang, Y. & Huang, Y. [Diagnostic efficacy of SHOX2 gene hypermethylation for lung cancer: A Meta-Analysis]. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 24 (7), 490–496. https://doi.org/10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2021.101.27 (2021).

Weiss, G., Schlegel, A., Kottwitz, D., König, T. & Tetzner, R. Validation of the SHOX2/PTGER4 DNA methylation marker panel for Plasma-Based discrimination between patients with malignant and nonmalignant lung disease. J. Thorac. Oncol. 12 (1), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2016.08.123 (2017).

Wei, B. et al. A panel of DNA methylation biomarkers for detection and improving diagnostic efficiency of lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96242-6 (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. Association of the SHOX2 and RASSF1A methylation levels with the pathological evolution of early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 24 (1), 687. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12452-x (2024).

Huang, W. et al. A novel diagnosis method based on methylation analysis of SHOX2 and serum biomarker for early stage lung cancer. Cancer Control. 27 (1), 1073274820969703. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073274820969703 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the subjects who participated in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21876176) and the President Foundation of Hefei Institute of Physical Sciences (YZJJZX202009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.H., H.Z.W., and Y.N.C. conceived and designed the study. L.K. and J.Q. wrote the manuscript. L.K. collected and processed subject samples. X.H., W.T.L., and J.Q. performed data analysis and experiments performed. B.H., H.Z.W., and Y.N.C. reviewed, edited, and revised the data and manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China. Each study participant provided informed consent.

Consent for publication

All authors have consented to the publication of this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ke, L., Huang, X., Liu, W. et al. A prediction model based on cfDNA concentration and cfDNA methylation biomarkers for lung cancer detection. Sci Rep 15, 30969 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15273-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15273-5