Abstract

Due to growing demands for sustainable food production, controlled-environment vertical farms (CEVFs) have emerged as promising systems for cultivating vegetables and herbs in urban areas. However, these systems are often criticized for their high energy consumption, largely influenced by artificial lighting. This study aimed to optimize white LED-based lighting by supplementing it with additional deep red (DR, 660 nm) and far red (FR, 730 nm) light, evaluating effects on the growth of lettuce (Lactuca sativa cv. Batavia-Caipira) and basil (Ocimum basilicum cv. Emily). Five treatments were tested, all using a white LED base spectrum (with blue, green, and red components), with varying levels of DR and FR. In one treatment, light intensity (PPFD) was doubled to 244 µmol·m⁻2·s⁻1, while others were maintained at 122 µmol·m⁻2·s⁻1. The high-PPFD treatment resulted in the highest biomass, increasing fresh weight by 76% in lettuce and 79% in basil compared to white light alone. Among the treatments with equal PPFD, supplemental FR increased leaf number and canopy size, while DR enhanced biomass. Chlorophyll and nitrogen contents were highest under white-only light. Correlation analysis showed that the intensity of added DR and FR significantly influenced plant responses. These results suggest targeted DR and FR supplementation improves light-use efficiency in CEVFs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global demands for sustainable and healthy crop production, without reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides, have increased significantly in recent decades1,2. Controlled-environment vertical farms (CEVFs), which use hydroponic systems and light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as artificial light sources, have emerged as promising systems to meet these demands3. CEVFs allow high-density cultivation of a wide range of crops in compact urban spaces, independent of external environmental factors4. In addition to enabling all-season farming, LED-based lighting systems provide spectral control over plant growth. However, despite their advantages, CEVFs are often criticized for their high energy consumption, much of which is related to artificial lighting. The type and spectral composition of LED light significantly affect both the energy efficiency and productivity of CEVFs. Different LED wavelengths vary in their energy-to-photon conversion efficiency and optimizing light spectra can reduce electricity cost while maximizing biomass output5. LEDs also influence plant development both directly (e.g., altering morphology and physiology) and indirectly (e.g., enhancing photosynthesis)6,7,8. Therefore, adjusting the spectral quality and intensity of LED lighting is essential for both economic and biological optimization of vertical farming systems.

Although the advantages of LEDs in CEVFs are well documented, optimizing their efficiency for specific crops still required detailed investigation into how different spectral compositions and light intensities affect plant growth and development. Numerous studies have explored the influence of LED spectra on various crops9,10,11, with particular attention to the width or narrowness of the wavelength range, and whether single-color or multispectral combinations are more effective11,12.

The photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) spectrum, defined as 400–700 nm, includes blue (B, ~ 400–450 nm), green (G, ~ 500–600 nm), and red (R, ~ 600–700 nm) wavelengths, each playing distinct roles in plant development13. Red and blue light are particularly critical for photosynthesis and photomorphogenesis. Numerous studies have demonstrated that red:blue (R:B) ratio can significantly influence plant growth, although the optimal ratio is species-dependent14,15,16. For lettuce and basil an R:B ratio around 3:1 has been suggested to promote improved growth performance17.

Beyond blue and red, other spectral regions such as green and yellow light have been explored for their physiological effects18,19. Green light has the ability to penetrate deeper into the plant canopy than red or blue, potentially enhancing light distribution and supporting photosynthesis in lower leaves20,21. However, the role of green light remains debated. While some studies highlight its contributions to plant growth, others suggest it is less efficient and unnecessary in artificial lighting setups18,22. Similarly, the impact of yellow light (Y, ~ 550 nm) on plant growth is not well understood, with some evidence indicating a negative effect on development23. These mixed findings underscore the complexity of spectral responses and the importance of evaluating combinations of wavelengths rather than isolated colors.

Far red (FR, 700–800 nm) light, although outside the traditional PAR range, has received growing attention for its ability to enhance plant growth by promoting shade avoidance response, increasing canopy expansion, and improving light absorption24. However, the optimal ratio of red to far-red (DR:FR) and its effect on plant physiology, including chlorophyll concentration, remains subjects of ongoing debate25,26. Recent studies have shown that FR supplementation can significantly enhance biomass production and canopy size in crops like lettuce and tomato, although in some cases this comes at the cost of reduced pigment or mineral content27,28. Yield improvements of up to 25% in tomato and 39% in lettuce have been reported when FR light was applied at specific durations during the photoperiod29,30. These findings highlight that both the intensity and timing of FR application are critical to achieving benefits without compromising crop quality.

In addition,31 broad-spectrum lighting, which more closely resembles natural sunlight, may outperform narrow-spectrum lighting in supporting plant growth and development31. Lu et al.31 demonstrated that broad-spectrum LEDs improved plant growth compared to single- or dual-band lighting. Studies have also shown that combining red and blue light with white LEDs can enhance plant morphology and visual quality, particularly in leafy crops such as lettuce32. Meng and Runkle24 reported that combining white, red, blue and far-red light lead to greater lettuce yield than narrower spectra.

Another key consideration in designing lighting strategies for vertical farms is photon flux density (PPFD), which determines the total light intensity received by the plants. Although optimal values vary across crops and setups, studies suggest that a PPFD of 250 μmol m−2 s−1, combined with an R:FR ratio 11:5, supports robust lettuce growth33, while spinach may perform better under lower intensities, such as 100 μmol m−2 s−1 with an R:B of 4:134. However, these findings are based on individual experiments and may not apply universally. Additionally, most do not consider the potential benefits of dynamic lighting, which adjusts light quality and intensity in response to crop development or energy costs, as discussed in recent literature35.

In this study, we tested the impact of adding supplemental deep red (660 nm) and far red (730 nm) LEDs to a fixed white LED background. The treatments created different spectral compositions, not isolated wavelengths, and were designed to reflect realistic conditions used in commercial CEVFs. We also evaluated the effect of increasing PPFD by doubling the total photon output in one treatment. The test crops, lettuce (Lactuca sativa cv. Batavia-Caipira) and basil (Ocimum basilicum cv. Emily), were selected because they represent widely cultivated leafy greens and herbs in vertical farms, with different light sensitivity profiles and growth habits (cool-season vs. warm-season).

We hypothesized that the addition of DR and FR light to a white LED base, and adjusting their relative intensities, would enhance growth parameters such as biomass accumulation, canopy development, and nutrient content. We further expected that increasing total PPFD would improve growth responses, but only when spectral quality was optimized.

Results

Lettuce growth and physiological responses under different light treatments

The effects of five LED treatments on the growth parameters of lettuce are illustrated in Fig. 1. Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) were observed among treatments for most measured variables (Supplementary Table S1).

Effects of five LED treatments (W, WDR61, WFR30, WDR61FR30, WDR122FR60) on the growth parameters, chlorophyll content, and nitrogen concentration in lettuce cultivar “Batavia- Caipira”. In each treatment, W refers to a broad-spectrum white LED, while DR and FR denote supplemental deep red and far-red light, respectively. The numbers indicate the photon flux densities (μmol·m−2·s−1) of the added DR or FR light.

The treatment with both deep red and far-red supplementation at increased photon flux density (WDR122FR60) resulted in the highest values across nearly all parameters, including leaf number, leaf area, fresh and dry weight of leaves and roots, as well as chlorophyll and nitrogen content. Lettuce grown under white LED only (W) exhibited the lowest growth parameters. When comparing white light supplemented with either deep red (WDR61) or far-red (WFR30), far-red led to a greater increase in leaf number and area, while deep red more effectively promoted biomass accumulation. The combination of deep red and far-red (WDR61FR30) further improved plant performance (Fig. 1).

WDR122FR60 also resulted in the highest chlorophyll and nitrogen contents overall. Among the treatments with equal PPFD, white light alone (W) showed relatively higher values for these two traits, although the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 1).

Basil growth and physiological responses under different light treatments

The impact of the same five light treatments on basil growth is presented in Fig. 2. All growth parameters showed significant differences between treatments (P ≤ 0.05), with WDR122FR60 consistently resulting in the highest values (Supplementary Table S2).

Effects of five LED treatments (W, WDR61, WFR30, WDR61FR30, WDR122FR60) on the growth parameters, chlorophyll content, and nitrogen concentration of basil cultivar “Emily”. In each treatment, W refers to a broad-spectrum white LED, while DR and FR denote supplemental deep red and far-red light, respectively. The numbers indicate the photon flux densities (μmol·m−2·s−1) of the added DR or FR light.

Basil plants under white light only (W) had the lowest values for biomass, leaf number, and area. The combination of deep red and far-red (WDR61FR30) significantly improved growth metrics, and further increases were observed under the higher intensity treatment (WDR122FR60). No significant differences were detected between WDR61 and WFR30, although WDR61 yielded greater fresh and dry weights, whereas WFR30 produced larger leaves and a greater number of leaves. As with lettuce, chlorophyll and nitrogen contents peaked under WDR122FR60, with no significant variation among the other treatments (Fig. 2).

Relationships between DR:B and DR:FR ratios and plant responses

The relationships between spectral ratios, deep red to blue (DR:B) and deep red to far-red (DR:FR), and plant growth parameters were evaluated for both crops (Figs. 3 and 4, Supplementary Table S3). These plots offer a clear visual representation of how variations in spectral quality influence morphological and physiological traits in lettuce and basil under different lighting treatments.

Three-dimensional (3D) scatter plot showing relationships between spectral ratios, and key growth parameters in lettuce cultivar “Batavia-Caipira”. Each subplot represents one measured trait (Z-axis) in relation to spectral values. The X-axis (blue numbers) corresponds to deep red to blue (DR:B) ratio, and the Y-axis (red numbers) to the deep red to far-red (DR:FR) ratio. The color gradient indicates the magnitude of each trait value (visualizations generated using the scatter3D function from the plot3D package in R).

Three-dimensional (3D) scatter plot showing relationships between spectral ratios, and key growth parameters in basil cultivar “Emily”. Each subplot represents one measured trait (Z-axis) in relation to spectral values. The X-axis (blue numbers) corresponds to the deep red to blue (DR:B) ratio, and the Y-axis (red numbers) to the deep red to far-red (DR:FR) ratio. The color gradient indicates the magnitude of each trait value (visualizations generated using the scatter3D function from the plot3D package in R).

In lettuce (Fig. 3), all growth parameters except root dry weight were significantly correlated with both DR:B and DR:DR. Leaf number, leaf area, and leaf biomass (fresh and dry weight) increased with higher values of both spectral ratios, indicating a shared contribution of DR and FR in enhancing above-ground growth. Root dry weight, however, showed stronger responsiveness to DR:B ratio, suggesting a higher sensitivity to deep red relative to blue light. Chlorophyll and nitrogen content remained relatively unchanged across the spectral ratios.

In basil (Fig. 4), leaf number and area were more influenced by DR:FR, while leaf biomass showed a clearer positive correlation with DR:B. Similar to lettuce, root biomass and physiological traits such as chlorophyll and nitrogen content exhibited less variation in response to the spectral ratios.

Discussion and conclusion

Artificial lighting is fundamental for enabling plant production in CEVFs. Among the various artificial lighting options, LEDs are preferred due to their energy efficiency, spectral controllability, longevity, and ability to emit narrow or broad spectra. Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR, 400–700 nm) is critical for driving photosynthesis, with red and blue wavelengths being most effective in exciting chlorophylls15,16. However, broadband white light, which includes parts of the green spectrum, also enhances canopy penetration and supports whole plant development36,37. Recent studies have shown that W LEDs can support plant growth effectively31, particularly when used in combination with other spectral wavelengths as supplemental light sources22.

In this study, we analyzed how varying the spectral ratios of supplemental deep red and far-red light added to W LED background influenced plant development in lettuce (cv. Batavia-Caipira) and basil (cv. Emily). By adjusting the DR:B and DR:FR ratios and altering PPFD levels, we aimed to identify the most effective light receipts for optimizing both yield and quality-related traits including biomass production, chlorophyll and nitrogen content, and root development. While our work tests a selected range of realistic spectra rather than all possible combinations, it provides insight into how precise spectral adjustment within a W background can influence growth dynamics in commonly cultivated leafy crops.

Our findings showed that supplementing W light with DR and FR slightly improved both fresh and dry biomass. This agrees with prior studies highlighting the role of spectral optimization, especially the synergistic use of red and far-red light, in enhancing biomass accumulation and morphogenesis32,38,39. We found that the DR:B ratio had a marked influence on morphological traits and biomass. This supports earlier findings that the balance between blue and red light strongly affects physiological responses depending on species8,15,40,41. In our experiments, lower blue treatments promoted greater biomass accumulation in lettuce, consistent with previous findings in lettuce, rice and grape and strawberry17,42,43,44. This aligns with findings by Son et al., who found that while red light primarily enhances growth and structure, blue light boosts nutritional compounds, suggesting a trade-off between yield and quality depending on spectrum45.

In addition to DR:B, our results revealed that the DR:FR ratio significantly influenced leaf architecture and biomass weight. Adding FR light increases canopy size and the number of leaves, while DR light more directly contributed to biomass accumulation. These effects can be attributed to shade avoidance responses mediated by FR, such as stem and leaf expansion via phytochrome inactivation46. Increased projected canopy size (PCS) under FR likely resulted from more absorbed light and improved dry mass production47. Our observations are in agreement with studies showing that FR triggers structural expansion and biomass gain, while DR contributed to biomass build-up48. Jishi et al. showed that similar findings where alternating red and blue light cycles boosted dry weight and structural traits like leaf elongation, potentially enhancing light absorption49.

However, not all spectral adjustments were beneficial. We found that supplemental FR reduced chlorophyll and nitrogen content in leaves, confirming earlier findings by Li and Kubota50, who attributed this to chlorophyll saturation or downregulation under high FR exposure50. This aligns with Vastakaite et al., who observed that excessive blue light at the end of the day reduced photosynthetic efficiency in mature lettuce. These results highlight the importance of timing and plant developmental stage when applying dynamic spectral treatments51.

Increasingly, our highest-yielding treatment coincide with the highest PPFD, reinforcing the central role of light intensity in biomass production. While Kelly et al. found no significant yield differences within a limited PPFD range (215–265 μmol·m−2·s−1)52, our data, in line with Jin et al.33 indicate that increased PPFD boosts pigmentation, structural robustness, and yield, likely due to increased photosynthetic rate and light absorption33. In support, Jin et al. showed that a gradually increasing PPFD during cultivation improved by up to 18%, driven by more effective light absorption during peak growth stages53.

Our results also support the emerging interest in dynamic lighting strategies in vertical farming. For example, van Brenk et al.27 demonstrated that short-duration blue light during only part of the photoperiod maintained nutritional quality while preserving energy. This is in line with our findings that limited B supplementation can support chlorophyll levels without compromising biomass. Similarly, cultivar-specific responses to dynamic light profiles were reported by Versile et al., which may explain differences between basil and lettuce in our treatments54.

In terms of application, dynamic environmental controls, adjusting light spectrum, intensity, and duration based on crop feedback and electricity pricing, are increasingly recommended. Kaiser et al.35 emphasized this approach, showing how real-time plant sensing and automated lighting management can lower costs while maintaining productivity. Our results reinforce the need for future lighting strategies in vertical farming to move beyond fixed receipts toward adaptable, species- and stage-specific light management systems.

In summary, this study demonstrates that supplementing W LEDs with selected ratios of DR and FR light can significantly enhance growth and quality traits in lettuce and basil. The DR:B and DR:FR ratios each influence specific physiological responses, underscoring the importance of spectral precision. Increasing PPFD further improved growth, confirming the dual importance of spectral quality and light quantity. These findings contribute to the development of efficient, adaptive lighting recipes for vertical farming. Future studies should explore dynamic light regimes in alongside responsive environmental controls to maximize energy efficiency, crop quality, and yield in CEVFs.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and cultivation conditions

In this study, Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. cv. Batavia-Caipira) and basil (Ocimum basilicum L. cv. Emily), were selected as model species. The seeds were supplied by Enza Zaden (the Netherlands). These crops are widely used in vertical farming due to their fast growth cycles, high market demand, and responsiveness to light treatments. The experiments were conducted at Vegger B.V., a vertical farming technology developer located at the World Food Center in Ede, the Netherlands. A standardized protocol for cultivation, sampling, and analyses was followed for both species.

Cultivation of basil

Basil seeds (Enza Zaden, the Netherlands) were sown in plantation pots (9 cm H × 9 cm W × 9 cm L) filled with vermiculite. During germination, pots were sprayed daily with distilled water and placed in dark, closed, heated plastic boxes at 24 ± 2 °C, 50–60% relative humidity and 450 ppm CO2.

Cultivation of lettuce

Lettuce seeds (Enza Zaden, the Netherlands) were initially placed in a rockwool plugs, irrigated daily with distilled water, and maintained at 22 ± 2 °C, 50–60% relative humidity and 450 ppm CO2.

Controlled-environment vertical farm (CEVF)

The vertical farming systems used were equipped with hydroponics using ebb-flow method and controlled by monitoring and dosing system to regulate environmental parameters (EC, pH, CO2, humidity, and temperature) and LED lighting. All systems were remotely traceable and programmable via a mobile application, enabling consistent growth condition for all treatments.

Transferring to hydroponic system

Seven days after sowing, once the first true leaves appeared, seedlings were transplanted. Lettuce plugs were transferred to a rockwool blocks, and basil seedlings were moved from germination pots to hydroponic units. All plants were then placed in the CEVFs.

Nutrient solution

The nutrient solution was prepared based on the Hoagland and Arnon (1950) formulation with the following concentrations per liter of tap water: 136 g KH2PO4, 101 g KNO3, 236.15 g Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, 246.48 g MgSO4·7H2O, 2.86 g H3BO3, 1.86 g MnCl2·4H2O, 0.22 g ZnSO4·5H2O, 0.08 g CuSO4·5H2O, 0.02 g H2MoO4·H2O, and 10 g Fe-EDDHA, resulting in an electrical conductivity (EC) of 1.2 dS/m and a pH of 6.5.

Experimental design

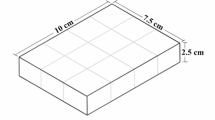

The study tested five LED light treatments using combinations of white (W), deep red (DR), far-red (FR) LEDs (Greenpower LED Production Module 3, Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Each treatment was delivered using separate LED modules for each spectral component, allowing independent control of light quality and intensity. The LEDs were dynamic, and both light density and spectral composition were adjustable. Light intensity at the top of the plant canopy was measures using quantum sensor (Apogee MQ-500, Apogee Instruments, Logan, UT, USA). All treatments were applied under controlled conditions (20 ± 1 °C, 50–60% relative humidity, and 450 ppm CO2), with four biological replicates per treatment. The photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) on the top of the plant canopy was on average 122 μmol m − 2 s − 1 in the first four treatments (W, WDR61, WDR30 and WDR61FR30), while in the final treatment (WDR122FR60), the PPFD was doubled to 244 μmol m − 2 s − 1 (Table 1 and Fig. 5). The photoperiod was maintained at 16 h light and 8 h dark.

Spectral composition of the five lighting treatments used in the study. The bars show the photon flux density (µmol·m⁻2·s⁻1) contributed by each LED wavelength: blue (B, 450 nm), green (G, 530 nm), deep red (DR, 660 nm), and far red (FR, 730 nm). Treatment W included only white light, while other treatments received various combinations of supplemental DR and FR light. The final treatment (WDR122FR60) had the highest total photon flux density, with both DR and FR doubled.

Data collection

Lettuce and basil were harvested 45 and 30 days after transfer, respectively. Growth parameters included leaf number, leaf area, fresh and dry weights of leaves and roots. Dry matter was determined after oven-drying samples at 72 °C for 72 h55.

The total chlorophyll content was measured from the third grown leaf following the method of Wellburn56. A 100 mg fresh leaf sample was extracted in 5 ml of 80% acetone, and mixture and centrifuged at 3800 rpm for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured using a spectrophotometer (Rayleigh VIS-7220G) at 663, and 649 nm, and total chlorophyll was calculated using Wellburn’s formula56.

Nitrogen concentration (%) was determined using a modified Kjeldahl method55 and expressed as both percentage of dry matter and mg kg-1 dry weight (DW).

Statistical analysis

Two-way ANOVA was performed to analyze the effects of lighting treatment on growth variables using a randomized complete block design in R v.4.0.2 via Rstudio (RStudio Team (2020), Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA). The least significant difference (LSD) test was applied at p < 0.05 to compare treatment means. DR:B and DR:FR ratios were further analyzed against measured traits using two-way ANOVA. Visualizations were created using the “scatter3D” function in the “Plot3D” package in R.

Data availability

All analyses are summarized in the manuscript and in the supplementary file.

References

Martin, M. & Molin, E. Environmental assessment of an urban vertical hydroponic farming system in Sweden. Sustainability 11(15), 4124 (2019).

Romeo, D., Vea, E. B. & Thomsen, M. Environmental impacts of urban hydroponics in Europe: A case study in Lyon. Procedia Cirp 69, 540–545 (2018).

Promratrak, L. The effect of using LED lighting in the growth of crops hydroponics. Int. J. Smart Grid Clean Energy 6(2), 133–140 (2017).

Sambo, P. et al. Hydroponic solutions for soilless production systems: Issues and opportunities in a smart agriculture perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 10(923), 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00923 (2019).

Olvera-González, E. et al. Chlorophyll fluorescence emission of tomato plants as a response to pulsed light based LEDs. Plant Growth Regul. 69(2), 117–123 (2013).

Goto, E. Plant production in a closed plant factory with artificial lighting. Acta Hortic. 956, 37–49 (2012).

Kobayashi, K., Amore, T. & Lazaro, M. Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) for miniature hydroponic lettuce. Optics Photonics J. 3(1), 74–77 (2013).

Johkan, M., Shoji, K., Goto, F., Hashida, S. N. & Yoshihara, T. Blue light-emitting diode light irradiation of seedlings improves seedling quality and growth after transplanting in red leaf lettuce. Hort Sci. 45(12), 1809–1814 (2010).

Anindito, B. et al. Indoor agriculture: Measurement of the intensity of LED for optimum photosynthetic recovery. in International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Informatics (EECSI) vols 2018-October (2018).

Yeh, N. & Chung, J. P. High-brightness LEDs—Energy efficient lighting sources and their potential in indoor plant cultivation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 13(8), 2175–2180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2009.01.027 (2009).

Wang, Z., Tian, J., Yu, B., Yang, L. & Sun, Y. LED light spectrum affects the photosynthetic performance of Houttuynia cordata seedlings. Am. J. Opt. Photonics 3(3), 38–42 (2015).

Rabara, R. C., Behrman, G., Timbol, T. & Rushton, P. J. Effect of spectral quality of monochromatic LED lights on the growth of artichoke seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 190 (2017).

Gfeller, A., Herrera, J. M., Tschuy, F. & Wirth, J. Explanations for Amaranthus retroflexus growth suppression by cover crops. Crop Prot. 104, 11–20 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Carbohydrate accumulation and sucrose metabolism responses in tomato seedling leaves when subjected to different light qualities. Sci. Hortic. 225, 490–497 (2017).

Naznin, M. T., Lefsrud, M., Gravel, V. & Azad, M. O. K. Blue light added with red LEDs enhance growth characteristics, pigments content, and antioxidant capacity in lettuce, spinach, kale, basil, and sweet pepper in a controlled environment. Plants 8(4), 93 (2019).

Zhou, Z. et al. Improved luminescence and energy-transfer properties of Ca 14 Al 10 Zn 6 O 35: Ti 4+, Mn 4+ deep-red-emitting phosphors with high brightness for light-emitting diode (LED) plant-growth lighting. Dalton Trans. 47(38), 13713–13721 (2018).

Pennisi, G. et al. Resource use efficiency of indoor lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) cultivation as affected by red: Blue ratio provided by LED lighting. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 14127 (2019).

Dutta Gupta, S. & Jatothu, B. Fundamentals and applications of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) in in vitro plant growth and morphogenesis. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 7(3), 211–220 (2013).

Wu, T. et al. Analyses of multi-color plant-growth light sources in achieving maximum photosynthesis efficiencies with enhanced color qualities. Opt. Express 26(4), 4135–4147 (2018).

Massa, G. D., Emmerich, J. C., Morrow, R. C., Bourget, C. M. & Mitchell, C. A. Plant-growth lighting for space life support: A review. Gravitat. Space Biol. 19(2), 19–30 (2006).

Brodersen, C. R. & Vogelmann, T. C. Do changes in light direction affect absorption profiles in leaves?. Funct. Plant Biol. 37(5), 403–412 (2010).

Han, T. et al. Improving “color rendering” of LED lighting for the growth of lettuce. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 45944 (2017).

Folta, K. M. & Maruhnich, S. A. Green light: A signal to slow down or stop. J. Exp. Bot. 58(12), 3099–3111. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erm130 (2007).

Meng, Q. & Runkle, E. S. Growth responses of red-leaf lettuce to temporal spectral changes. Front Plant Sci 11, 571788 (2020).

Paz, M., Fisher, P. R. & Gómez, C. Minimum light requirements for indoor gardening of lettuce. Urban Agric. Reg. Food Syst. 4, 1–10 (2019).

Namgyel, T. et al. Effects of supplementary LED light on the growth of lettuce in a smart hydroponic system. in 2018 10th International Conference on Knowledge and Smart Technology: Cybernetics in the Next Decades, KST 2018 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/KST.2018.8426202.

Van Brenk, J. B., Courbier, S., Kleijweg, C. L., Verdonk, J. C. & Marcelis, L. F. M. Paradise by the far-red light: Far-red and red:blue ratios independently affect yield, pigments, and carbohydrate production in lettuce. Lactuca Sativa. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1383100 (2024).

Kelly, N. & Runkle, E. S. Dependence of far-red light on red and green light at increasing growth of lettuce. PLoS ONE 19, e0313084 (2024).

Vincenzi, E. et al. Duration, not timing during the photoperiod, of far-red application determines the yield increase in tomato. Sci. Hortic. 338, 113553 (2024).

Liu, J. & van Iersel, M. W. Far-red light effects on lettuce growth and morphology in indoor production are cultivar specific. Plants 11, 55 (2022).

Lu, N., Saengtharatip, S., Takagaki, M., Maruyama, A. & Kikuchi, M. How do white LEDs’ spectra affect the fresh weight of lettuce grown under artificial lighting in a plant factory?—a statistical approach. Agric. Sci. 10, 957–974 (2019).

Lin, K. H. et al. The effects of red, blue, and white light-emitting diodes on the growth, development, and edible quality of hydroponically grown lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var. capitata). Sci. Hortic. 150, 86–91 (2013).

Zhang, X., He, D., Niu, G., Yan, Z. & Song, J. Effects of environment lighting on the growth, photosynthesis, and quality of hydroponic lettuce in a plant factory. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 11, 33–40 (2018).

Zou, T., Huang, C., Wu, P., Ge, L. & Xu, Y. Optimization of artificial light for spinach growth in plant factory based on orthogonal test. Plants 9, 490 (2020).

Kaiser, E. et al. Vertical farming goes dynamic: Optimizing resource use efficiency, product quality, and energy costs. Front. Sci. 2, 1411259 (2024).

Massa, G. D., Emmerich, J. C., Morrow, R. C., Bourget, C. M. & Mitchell, C. A. Plant growth lighting for space life support: A review. Gravit. Space Biol. 19, 19–30 (2006).

Brodersen, C. R. & Vogelmann, T. C. Do changes in light direction affect absorption profiles in leaves?. Funct. Plant Biol. 37, 403–412 (2010).

Metallo, R. M., Kopsell, D. A., Sams, C. E. & Bumgarner, N. R. Influence of blue/red vs. white LED light treatments on biomass, shoot morphology, and quality parameters of hydroponically grown kale. Sci. Hortic. 235, 189–197 (2018).

Park, Y. & Runkle, E. S. Spectral effects of light-emitting diodes on plant growth, visual color quality, and photosynthetic photon efficacy: White versus blue plus red radiation. PLoS ONE 13, e0202386 (2018).

Yorio, N. C., Goins, G. D., Kagie, H. R., Wheeler, R. M. & Sager, J. C. Improving spinach, radish, and lettuce growth under red light-emitting diodes (LEDs) with blue light supplementation. HortScience 36, 380–383 (2001).

Son, K. H. & Oh, M. M. Leaf shape, growth, and antioxidant phenolic compounds of two lettuce cultivars grown under various combinations of blue and red light-emitting diodes. HortScience 48, 988–995 (2013).

Poudel, P. R., Kataoka, I. & Mochioka, R. Effect of red- and blue-light-emitting diodes on growth and morphogenesis of grapes. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 92, 147–153 (2008).

Nhut, D. T., Takamura, T., Watanabe, H., Okamoto, K. & Tanaka, M. Responses of strawberry plantlets cultured in vitro under superbright red and blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 73, 43–52 (2003).

Litvin, A. G., Currey, C. J. & Wilson, L. A. Effects of supplemental light source on basil, dill, and parsley growth, morphology, aroma, and flavor. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 145, 18–29 (2020).

Son, K. H. et al. Growth and bioactive compound synthesis in cultivated lettuce subject to light-quality changes. HortScience 52, 584–591 (2017).

Ramalho, J. C., Marques, N. C., Semedo, J. N., Matos, M. C. & Quartin, V. L. Photosynthetic performance and pigment composition of leaves from two tropical species is determined by light quality. Plant Biol 4, 112–120 (2002).

Legendre, R. & van Iersel, M. W. Supplemental far-red light stimulates lettuce growth: Disentangling morphological and physiological effects. Plants 10, 166 (2021).

Mickens, M. A. et al. A strategic approach for investigating light recipes for ‘Outredgeous’ red romaine lettuce using white and monochromatic LEDs. Life Sci Space Res (Amst) 19, 53–62 (2018).

Jishi, T., Matsuda, R. & Fujiwara, K. Blue light monochromatic irradiation for 12 hours in lighting pattern with combinations of blue and red light elongates young cos lettuce leaves and promotes growth under high daily light integral. HortScience 56, 940–945 (2021).

Li, Q. & Kubota, C. Effects of supplemental light quality on growth and phytochemicals of baby leaf lettuce. Environ Exp Bot 67, 59–64 (2009).

Vaštakaitė-Kairienė, V., Samuolienė, G., Šveikauskas, V., Laužikė, K. & Jurkonienė, S. The influence of end-of-day blue light on the growth, photosynthetic, and metabolic parameters of lettuce at different development stages. Plants 11, 2798 (2022).

Kelly, N., Choe, D., Meng, Q. & Runkle, E. S. Promotion of lettuce growth under an increasing daily light integral depends on the combination of the photosynthetic photon flux density and photoperiod. Sci Hortic 272, 109565 (2020).

Jin, W. et al. Gradually increasing light intensity during the growth period increases dry weight production compared to constant or gradually decreasing light intensity in lettuce. Sci. Hortic. 311, 111807 (2023).

Viršilė, A., Miliauskienė, J., Haimi, P. J., Laužikė, K. & Samuolienė, G. The comparison of constant and dynamic red and blue light irradiation effects on red and green leaf lettuce. Agronomy 10, 1802 (2020).

Walinga, I., van der Lee, J. J., Huba, V. J. G., van Vark, W., Novozamsky, I. Plant analysis manual (2013).

Wellburn, A. R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 144, 307–313 (1994).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HF performed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the main manuscript, and contributed to the experimental design. VM supervised the study and revised the manuscript. HR and HS were involved in designing the experiments and revising the manuscript. SF and MF supervised the study, contributed to the design of the experiments, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Farhangi, H., Mozafari, V., Roosta, H.R. et al. Optimizing LED lighting spectra for enhanced growth in controlled-environment vertical farms. Sci Rep 15, 30152 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15352-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15352-7