Abstract

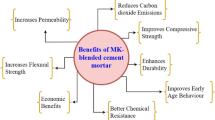

The growing demand for sustainable construction materials has driven interest in reusing industrial waste. This study explores the feasibility of incorporating shredded composite (SC) recycled from end-of-life (EoL) wind turbine blades (WTBs) into a cement-based mortar. Two SC fractions were tested: 0–2 mm as a partial cement replacement (10%, 15%, 20% by volume) and 0–32 mm as a partial aggregate replacement (20%, 30%, 40% by volume). Mechanical testing, digital image correlation (DIC), and microstructural analysis were used to assess performance. The 0–32 mm SC fraction significantly enhanced mortar properties when used as aggregate replacement, reducing porosity by up to 23.22%, increasing flexural strength by 36.51%, and improving the toughness index by 248.11%. In contrast, the 0–2 mm SC fraction, used as a cement substitute, led to a 27.55% increase in porosity, a 6.60% reduction in density, a 44.64% decrease in toughness, and a 45.12% decrease in compressive strength, indicating the need for further optimization of this approach. These findings demonstrate the potential of SC from EoL WTBs as a sustainable additive in cementitious composites, particularly when used as aggregate replacement. The study supports circular economy practices by reducing construction waste and valorising materials from decommissioned renewable infrastructure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global shift towards renewable energy sources has led to the rapid growth of the wind energy sector, which is a key element in mitigating climate change and reducing dependence on fossil fuels. Wind turbines offer many benefits including being environmentally friendly and cost-effective over their life cycle1. However, wind turbine blades (WTBs) have a limited lifespan, typically ranging from 20 to 25 years2,3, after which they reach end-of-life (EoL). Over time, their structural integrity can deteriorate, reducing their efficiency and reliability, due to exposure to environmental conditions such as wind loads, ultraviolet (UV) radiation and temperature changes. As a result, these blades must be decommissioned at the end of their service life, which, due to their large size and complex composite materials, presents significant challenges in terms of their disposal and resource recovery. Addressing these challenges is essential to ensure the sustainability of the wind energy industry and to minimise its impact it has on the environment.

Wind turbine blades are typically made from fibre reinforced polymers (FRP), which consist of fibres (glass or carbon) and polymer resin. The fibre reinforced polymer composite makes the majority of the blade, with approximately 60–70% of reinforcing fibres and 30–40% of resin as polymer matrix4. In addition, a blade contains materials such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) foam, polyurethane (PUR) foam, balsa wood, epoxy gelcoat, metals and others, depending on the manufacturer5. Wind turbine blades are designed to be durable, efficient and reliable throughout their lifetime. At the same time, they are non-biodegradable and very difficult to recycle using conventional methods6. Landfilling and incineration remain the most common disposal practices for wind turbine blades. Despite their prevalence, they are considered unsustainable and lead to a loss of valuable materials. Such solutions, are at the bottom of the waste management hierarchy7. Therefore, various strategies have been developed in recent years to avoid wasting valuable material and promote circular economy solutions (e.g8,9,10,11), including repurposing and recycling.

Repurposing involves re-use of WTBs for a different applications and transforming old blades into including products, such as architectural and structural components12,13,14,15 which is often preceded by checking the actual stiffness of the composite elements of WTBs at their EoL stage15,16 or their connections17. Recycling of WTBs means transforming a material into a new substance of product. The recycling methods can be broadly categorized into thermal, chemical and mechanical4,18,19,20. Research is mainly being conducted to develop improved methods of separating fibres from resin or reusing shredded WTBs21,22. Thermal recycling consists of the heating the composite in processes such as pyrolysis, microwave pyrolysis or fluidized bed process23, to decompose the resin to recover fibres. Chemical recycling, e.g., solvolysis24, hydrolysis or supercritical fluid processes25 involves using solvents or chemical reagents to dissolve the resin matrix, recover the fibres. Mechanical recycling involves breaking down the composite material into smaller parts by shredding, grinding, cutting or milling. The material obtained is a composition of fibre products and powdered filles that can be further sieved. Recycled component materials can be reused in various construction applications, which is in line with the idea of a circular economy and sustainable development.

Reusing of waste fibre reinforced polymer materials in concrete is gaining popularity and is being intensively developed in industries and research institutions worldwide26,27,28,29. This focus is driven by the growing demand for cement binders caused by infrastructure development. Since cement consumption and concrete production have been found to impact sustainability the most30, the use of recycled waste presents a promising approach to reducing the environmental footprint of the construction industry. With the increasing number of wind turbine blades being decommissioned, the need of research on new materials incorporating WTBs as constructional materials is increasingly important. Example applications of WTBs in composite building materials include mortars, concrete, asphalt and geopolymers14. The potential of various forms of recyclate from wind turbine blades has been investigated in a number of studies. In general, recyclates from end-of-life wind turbine blades includes recycled chunks (WTB cut into larger pieces) used as aggregates, recycled fibres as reinforcement fibres for concrete and recycled powder supplementary cementitious materials10. The feasibility of using raw-crushed wind-turbine blades in concrete have been demonstrated by many papers (e.g31,32,33,34,35. Much research has also been devoted to the incorporation discrete slender elements into concrete, such as macro fibres36,37 or needles38,39,40. Work has also been carried out on the addition of finer fractions of shredded wind turbine blades to concrete mixtures41,42,43,44,45. However, most of the aforementioned work has focused on mechanical parameters, without an in-depth examining the influence of the fibrous material on fracture evolution.

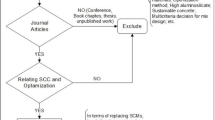

In this study, an experimental approach was used to investigate the effect of incorporation of shredded composite material obtained from EoL WTBs on the mechanical properties of cement-based mortars. Although the reuse of wind turbine blade waste in cementitious materials has been explored in previous studies, the present work introduces several novel aspects. First, it evaluates the effect of two distinct shredded composite (SC) fractions, 0–2 mm and 0–32 mm, used respectively to replace cement and aggregate at relatively high volumetric levels (up to 20% and 40%). Second, the study applies digital image correlation (DIC) to monitor crack development and fracture behaviour during bending tests, providing a more detailed and quantitative analysis of damage mechanisms than typically found in the literature. In addition, toughness indices were evaluated to characterize post-cracking performance. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to integrate mechanical testing with full-field strain measurements via DIC in the context of mortars incorporating SC from EoL WTBs. This comprehensive approach contributes valuable insight into the role of recycled fibrous materials in enhancing the mechanical performance and durability of cement-based composites.

Materials and methods

Raw materials

The materials used to produce the environmentally friendly cementitious composites were: cement, water, sand and shredded composite (SC) recycled from wind turbine blades. The cement used was reduced emission cement containing 35% fly ash, type CEM II/B-V 42.5R Lafarge Portland cement (The Kujawy Cement Plant, Poland). The physical and chemical properties of the cement are given in Table 1. Sand from an open pit mine (Polgravel, Borowiec mine, Poland) was used as fine aggregate. The sand was washed and sieved to obtain grain sizes up to 4 mm (sand 0–4). The grain distribution of the sand is shown in Fig. 1. Tap water was used to the mixture. No modifiers or chemical admixtures were used in the preparation of the cement composites. Densities of all material used in the mixture are given in Table 2.

As an additional ingredient in the cement mortar, shredded composite material from the end of life of wind turbine blades was used. Since entire wind turbine blades were shredded without separation of components, hence the shredded material included glass fibres, epoxy resin and other materials comprising blades. The percentage of materials was not standardised, as the material came from ground blades of different types. However, based on the typical product disposal specifications, it can be assumed that mass percentage was: glass fibres ~ 60%, epoxy resin ~ 20%, other materials (PVC foam, PUR foam, balsa wood, gelcoat, etc.) ~ 20%.

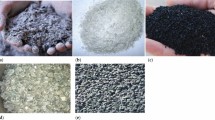

In the study, two different fractions of waste composite material were investigated. Fraction I (shredded composite 0–2 mm), shown in Fig. 2a, is grey-white in colour and contains small particles that are typically between 0.063 mm and 2 mm in size. These are particles of epoxy resin and micro glass fibres. Fraction II (shredded composite 0–32 mm) is a mixture of resin particles and glass fibres (Fig. 2b). These are elongated pieces of shredded material ranging from 0.125 mm to 32 mm in length. The particle size distribution of the SC of the fraction I and the fraction II are shown in Fig. 1. Figure 3 presents a scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the shredded composite material used in the study, along with its chemical composition. The microstructure reveals the rough, fibrous surface characteristic of shredded composite materials. The observed texture indicates mechanical degradation, with features such as surface fractures, fibre pull-outs, and irregularly shaped particles, typical of materials subjected to shredding processes. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) spectrum revealed the presence of several elements, including silicon (Si), aluminum (Al), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), calcium (Ca), and chlorine (Cl). The detected silicon originates from glass fibres or silica-based fillers, while aluminum may indicate the presence of alumina fillers or additives. Magnesium and calcium are commonly associated with mineral fillers present within the glass fibre matrix. Sodium and chlorine are likely related to processing agents and residual flame retardant compounds, respectively, introduced during the original manufacturing process.

Mix design

Seven concrete mixes were produced: one control mix without SC and six mixes with varying waste material content from end-of-life wind turbine blades. It was assumed that the fibre content in the shredded composite was 60%. The density of the SC ranged from 2020 kg/m3 to 2100 kg/m3, and the density of the fibres contained within the SC ranged from 1080 kg/m3 to 1120 kg/m3, depending on the fraction of SC (see Table 2). Table 3 presents details of the composite mixes. The composition of the mixtures was determined using an iterative method at laboratory scale. No modifiers or chemical admixtures were used to make the cementitious composites in order to reduce the number of variables and accurately determine the influence of the waste material on the properties of the cement mortar. A cement composite without additives consisting of cement, aggregate and water with a water to cement ratio (w/c) of 0.5 was used as a reference mix (M.0). Then, two sustainable groups of mixes were design.

In the first group, fraction I of shredded composite (0–2 mm) was used at 10%, 15%, 20% of the cement volume with a simultaneous reduction of the cement binder. The mixes were designated as M.I.10, M.I.15 and M.I.20, respectively. In these three mixes, M.I.10, M.I.15 and M.I.20, the water-cement ratio increased as the cement content of the mixture volume decreased and at the same time as the recycled material content of the wind turbine blades increased. In the second group of cement composites, fraction II of shredded composite (0–32 mm) was used to replace part of the aggregate (sand 0–4 mm) in amounts of 20%, 30% and 40% of the aggregate volume. The mixtures in the second group were designated as M.II.20, M.II.30 and M.II.40, respectively. In the second group of mixtures, the water-cement ratio was constant at 0.5. The “volume of fibre (%)” listed in Table 3 refers to the volumetric proportion of fibres present within the shredded composite (SC), either 0–2 mm or 0–32 mm fraction, used to replace a part of the cement or aggregate in the mortar mix.

Specimens preparation

The concrete components were mixed in a mechanical mixer with a ratio-planetary mixing blade system UEZ Labor-Zwangsmischer LZ 75/100 (Mischtechnik, Germany). First, sand with 0–2 mm (or 0–32 mm) shredded composite additive was dosed into the mixer, mixing for 2 min. Cement was then added, mixing the ingredients dry for a further 2 min ensuring even dispersion of the fibre additive. After this time, water was added. The mixing time for all components was 5 min. No agglomerate formation or other adverse phenomena were observed. The consistency of the mixtures was then measured using the flow test in accordance with EN 1015-3 Methods of test for mortar for masonry – Part 3: Determination of consistence of fresh mortar (by flow table). After the determination of the consistency, the mixture was placed in two layers in three-part mortar moulds. From each of the mixture, three beams with dimensions of 40 × 40 × 160 mm3 were manufactured. To remove air bubbles, each layer of the mixture laid in the mould was compacted on a special mortar shaking table, compacting each layer 60 times/min. The mixture moulds were protected from drying out by covering with foil and storing for 24 h indoors at 20 °C. The samples in the moulds were stored for 1 day in a room with a humidity of approximately 45%±5 at 20 ± 2 °C. After that, the samples were then unmoulded and were cured in water at 20 ± 2 °C for 28 days prior to testing.

Instrumentation and test procedures

Microstructural analysis

Microstructural analysis of fibres obtained from ground wind turbine blade was performed using scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging technique (JSM-7800 F, JEOL, Japan) and digital microscope (VHX-7000, Keyence, Belgium). In addition, the observation of the structure along with the determination of the porosity of the produced cementitious composites using a Keyence VHX-7000 digital optical microscope. Samples measuring 40 × 40 × 10 mm3 were cut from the 40 × 40 × 160 mm3 beams, perpendicular to its length. The samples were then ground and polished before being tested. The porosity tests were carried out on the basis of a detailed analysis of the cross-sectional image of the composite specimen with 20x magnification using high resolution lens VHX-E20.

Density

The density of the cementitious composites was determined using the volumetric method. The weight of the samples was measured using a RADWAG PS 200/2000.R2 laboratory analytical balance. The density tests were carried out on 40 × 40 × 160 mm3 beams conditioned in water at 20 °C ± 2 for 28 days. Prior to testing, the samples were removed from the water and left for 1 day under laboratory conditions at 22 °C ± 2 and approximately 35% humidity. The exact dimensions of each sample (height, width, depth) were then determined using a calliper and the volume of each sample was determined. Each sample was weighed using a RADWAG PS 200/2000.R2 laboratory analytical balance. The density of the samples was then calculated by dividing the weight of the sample by its volume in kg/m³.

Bending and DIC tests

The beams made of different mixtures were subjected to the 3-point bending test (Fig. 4a) in accordance with EN 196-1:2016 Methods of testing cement Part 1: Determination of strength. During the fracture process, the fracture process was monitored using the digital image correlation (DIC) technique. The bending experiments were performed in a Zwick/Roell Z10 universal testing machine (UTM). The beam was placed in a flexural kit with a distance between supports equal to 100 mm. Bending process was performed at a constant mid-span displacement of 0.1 mm/min with a preload of 50 N. The images of the front surface of the beams were acquired every 2 s with the ARAMIS MC 3D 12 M system.

Compression test

Compressive strength tests were carried out in accordance with EN 196-1:2016 Methods of testing cement Part 1: Determination of strength, using a Controls Advantest 9 testing machine with a maximum load of 3000 kN (Fig. 4b). The test rate was set at 0.5 MPa/s and the compression area was 40 × 40 mm2.

Results

Microstructure and porosity analysis

Figure 5 presents the microstructural images of the fracture surfaces of the selected beams after the bending process. The reference sample (M.0) is shown in Fig. 5a. Figure 5b illustrates sample M.I.20, in which 20% of cement was replaced with shredded composite fraction 0–2 mm. It can be observed that short, single glass fibres were evenly distributed and maintained good contact with the concrete matrix, with no evidence of fibre agglomeration. Since the fibres were short, no bridging effect was observed. Figure 5c shows an example of microscopic imaging of sample M.II.40, in which 40% of aggregate were replaced with shredded composite fraction 0–32 mm. One can see both single short fibres and larger parts of shredded material included larger parts of glass reinforced composites. It can be seen that these larger parts of fibres were incorporated to transfer stresses across cracks by bridging and stopping cracks forming during bending.

The porosity was determined on a 40 × 40 × 10 mm3 slices cut from the beams. An optical method based on the microscopic images was applied. Before capturing the images, the pores were filled with a white plaster compound to enhance contrast. The images were then acquired using a Keyence VHX-7000 digital optical microscope and subsequently processed to measure the pore areas. Figure 6 presents example images with identified pores on both the outer surface and the internal cross-section. Using the method, the air content was determined in the rage of 2.48–4.12%. The results of porosity for all concrete mixes, together with densities are given in Table 4.

Figure 7 shows bar graphs of the porosity and density of the analysed mortars for mixtures containing different fractions and amounts of recycled wind turbine material. The results obtained for the M.I mixes show that the porosity of the mortar increases as the amount of composite material increases, which is associated with a decrease in density. The reference mortar (M.0) had the highest density (2305.7 kg/m³) and relatively low porosity (3.23%), due to the lack of recycled additive. In the case of the M.I. mixes, in which the cement was partially replaced by the 0–2 mm fraction recycled additive, a systematic increase in porosity from 3.41 to 4.12% and a concomitant decrease in density from 2255.1 kg/m³ to 2153.5 kg/m³ was observed as the content of waste material increased. Analysing the percentage changes, porosity increased by 5.57%, 15.79%, and 27.55%, while density decreased by 2.19%, 4.14%, and 6.60% relative to the reference mixture, for specimens M.I.10, M.I.15, and M.I.20, respectively.

Similarly, a reduction in density from 2199.8 kg/m³ to 2155.7 kg/m³ was observed in the M.II group, in which fine aggregate (0–4 mm sand) was replaced with the addition of recycled fraction 0–32 mm. The results correlate with the porosity results, which decrease from 3.07 to 2.48%, indicating different mechanisms of influence of the recycled waste on the microstructure. Mixtures containing 0–32 mm fraction waste had lower porosity than those containing 0–2 mm fraction waste, which may be due to better filling of intergranular spaces by the larger component particles. An analysis of the percentage changes shows that porosity decreased by 4.95%, 17.34%, and 23.22%, while density decreased by 4.59%, 5.46%, and 6.51% compared to the reference mixture, for specimens M.II.20, M.II.30, and M.II.40, respectively.

Bending and compression test results

The results of measuring the flexural and compressive strength are presented in Table 5 and plotted in Fig. 8. Adding shredded composite 0–2 mm as a replacement of a part of cement resulted in decrease of both compressive and flexural strength. Replacing 10%, 15% and 20% of cement volume with SC resulted in 28.26%, 36.58% and 45.12% reduction of compressive strength, respectively, with respect to the reference mixture M.0. The decrease of flexural strength was smaller and amounted 12.24%, 22.49% and 31.48% for the mixes with 10%, 15% and 20% replacement of cement, respectively. A different behaviour was observed when replacing part of the aggregate with recycled material 0–32 mm. Both compressive and flexural strengths have been improved compared to the reference cementitious composite (M.0). The compressive strength of M.II.20, M.II.30 and M.II.40 specimens was 14.19%, 18.09% and 2.28% higher, respectively, than that of control sample M.0. The increase of flexural strength was more significant and amounted 23.61%, 29.17% and 36.51% for the specimens M.II.20, M.II.30 and M.II.40, respectively.

Fracture evolution results

During the 3-point bending tests, the influence of waste material on flexural performance of concrete specimens and fracture behaviour was characterized using DIC technique. Figure 9 illustrates the stress-deflection curves of all the tested specimens. It can be observed, that the stress-deflection curves of the beams made of the control mixture (M.0) and the beams from the first group (0–2 mm shredded composite, mixtures M.I.10, M.I.15, M.I.20) have a similar shape in a region before the peak, with an almost linear trend. After reaching the maximum bending strength, they decreased sharply and exhibited a brittle failure. The addition of 0–32 mm waste material changed the character of the curves significantly, improving the ductility and the bending load capacity. The stress-deflection curves of the beams from the first group (0–32 mm shredded composite, mixtures M.II.10, M.II.20, M.II.40) dropped after the maximum stress but continued to soften towards the end of the test.

The fracture evolution of all beams tested was examined using the DIC technique. In order to follow the cracks development, the major strain fields of the front surface were calculated. In Fig. 10, one selected beam from each group of three beams examined is shown. The strains at three selected stress levels were presented: 90% of the Fmax before peak (90% pre-Fmax), the peak value (Fmax), and the post-peak stage (90% post-Fmax).

In the case of beam M.0, no microcracks were observed until the peak force value, followed by a sudden fracture that resulted in the beam falling from the supports and splitting into two parts (Fig. 9a). The addition of a shredded composite with a 0–2 mm fraction resulted in a slight improvement in the fracture behaviour of M.I.10, M.I.15 and M.I.20 beams. It can be observed (Fig. 9b, c and d) that in the first crack developed at approximately 90% of the pre-peak load value. The final crack appeared abruptly and the crack developed over the entire height of the beam, but the presence of the fibrous material prevented the sample from completely damaging and breaking into two separate pieces.

The incorporation of waste material with the fibre lengths of up to 32 mm, resulted in a significantly improved fracture performance of M.II.10, M.II.20 and M.II.40 beams. For the force value 90% pre-Fmax cracks were already developed up to about 25–50% of the beam height as the formation of micro-cracking zones occurred much earlier. This indicates on an effective crack-arresting mechanism. The concrete matrix cracked first, and the combined bridging behaviour of the matrix surrounding the fibres limited the crack growth. At the peak value (Fmax) the cracks developed up to about 70% of the beam height. In the post-peak softening phase, the crack length gradually increased. This was due to the debonding of the fibre pull-out responses at the matrix interface.

To quantitatively evaluate the energy absorption capacity of the composites under flexural loading, the toughness index (IG) was calculated. The toughness index (IG) was defined as the area under the stress-displacement curves given in Fig. 9, from zero stress up to a specified post-peak stress level, taken as 40% of the maximum stress46. Table 6 and Fig. 11 present the toughness index of the samples tested in 3-point bending test. For the M.I beams (cement partially replaced with 0–2 mm SC), the toughness index decreased with increasing SC content, from 1.25 kJ/m² (M.I.10) to 0.88 kJ/m² (M.I.20), compared to the reference mix M.0 (1.59 kJ/m²). This reduction is attributed to the limited crack-bridging ability of the short fibres and the increased porosity of the matrix. The decrease of toughness index amounted 21.42%, 27.26% and 44.64% for the mixes with 10%, 15% and 20% replacement of cement, respectively.

In contrast, the M.II beams (with aggregate partially replaced by 0–32 mm shredded composite) demonstrated a significant improvement in toughness. The toughness index increased from 3.63 kJ/m² for M.II.20 to 5.53 kJ/m² for M.II.40, representing more than a threefold increase in energy absorption capacity compared to the control mix (1.25 kJ/m²). This enhancement is attributed to the effective fibre bridging and crack-arresting mechanisms provided by the longer and more heterogeneous fibres in the 0–32 mm fraction. The increase in toughness index corresponded to 128.14%, 197.13%, and 248.11% for specimens M.II.20, M.II.30, and M.II.40, respectively.

Discussion

Discussion of results

The results of the study confirmed a significant potential for the use of recycled wind turbine blades as an additive in cement mortars. The research revealed the complex effects of particle size and recyclate dosage on the microstructure and mechanical properties of the cementitious composites. The differences in the results for M.I and M.II mixes indicated that the role of the shredded composite, whether as a cement or aggregate replacement, was pivotal in influencing the physical and mechanical properties of the composites and their fracture mechanisms.

Mixtures of the M.I group, in which the 0–2 mm fraction of SC partially replaced cement, showed a systematic increase in porosity with increasing amounts of waste material. This increase, combined with a reduction in the density of the mortars, indicated the limited ability of the recyclate in this fraction to form strong bonds in the cementitious structure. This is consistent with findings by Revilla-Cuesta et al.32 who reported that the incorporation of finely crushed WTBs in concrete led to increased water absorption and porosity, particularly when used as a cementitious filler without additional treatment. Similarly, Kaboré et al.47 demonstrated that incorporating fine rGFRP particles (≤ 2 mm) in cement mortars increases water demand and porosity, which aligns with the trends observed in this study.

The failure of samples from M.I group in bending was sudden, without prior formation of noticeable microcrack zones, however the presence of the fibrous material had a beneficial effect on the material, preventing the specimen from completely breaking into two separate parts. Microstructural analyses revealed a uniform dispersion of fibres in the cement matrix, but the lack of fibre bridging effect suggests that the short fibre length in this fraction is not conducive to effective stress transfer. The decrease in the toughness index observed in the M.I series further supports the limited energy absorption capacity of short fibres. Similar reductions in toughness due to insufficient fibre length and ineffective crack-bridging have been reported by Sadrolodabaee et al.46, who studied micro-fibre reinforced cement composites and highlighted the importance of fibre-matrix interaction in enhancing post-peak behaviour. Nevertheless, our study demonstrates that the fibres exhibit good bonding with the cement matrix, as confirmed by microscopic observations. This suggests that the mechanical performance of the composite could be further improved through appropriate surface modification of the fibres or by optimizing their length to enhance stress transfer and crack-bridging efficiency.

In contrast, the mixtures of group M.II, in which the 0–32 mm fraction of SC partially replaced the aggregate, demonstrated improved mechanical performance and reduced porosity. The reduction in porosity in this group was primarily attributed to the effective filling of inter-grain spaces by the larger recyclate particles. This observations align with the findings of Revilla-Cuesta et al.31,35, who demonstrated that raw-crushed WTBs can effectively fill intergranular voids and increased concrete porosity. The results of the present study also showed that enhanced particle bonding contributed to improved mechanical integrity. These effects were particularly evident in the M.II mixtures, which exhibited both lower porosity and higher mechanical strength, confirming the beneficial role of coarse SC particles in optimizing the microstructure and mechanical behaviour of cementitious composites. Based on microstructural observations, this enhancement in both compressive and flexural strength is likely due to a combination of improved particle packing, matrix densification, and potential crack-bridging effects introduced by the presence of larger, elongated fibres, which was confirmed in both microstructural analyses and bending tests using the digital image correlation technique. These mechanisms may have contributed to a more efficient stress transfer and delayed crack propagation. In addition, the presence of larger, elongated fibres in this fraction allowed a bridging effect to occur, which was confirmed in both microstructural analyses and bending tests using the digital image correlation technique. This observation is consistent with findings by Yazdanbakhsh et al.38, who emphasized that fibre geometry, particularly length and aspect ratio, plays a critical role in post-cracking ductility and energy dissipation in fibre-reinforced composites. These findings are supported by Fu et al.36,37, who showed that macrofibres from recycled GFRP significantly enhance flexural strength and toughness by arresting crack propagation.

Moreover, the toughness index values for M.II mixes (up to 5.53 kJ/m²) are comparable to or exceed those reported by Sadrolodabaee et al.46, who used waste micro-fibre material in concrete and observed substantial improvements in energy absorption capacity. These findings of our study confirm that the incorporation of larger shredded composite (SC) particles not only improves flexural strength but also significantly enhances the ductility and energy dissipation capacity of the mortar, making it more suitable for applications requiring resistance to dynamic or impact loads.

A comparison of the two groups indicates that the use of recyclate as an aggregate replacement can result in more favourable microstructural and mechanical properties than its use as a cement replacement. This is mainly due to differences in the ability of the different recyclate fractions to interact with the cement matrix. These observations emphasise the need to match the recyclate fraction to the function it is to perform in the cementitious structure.

Study limitations

Although the results of this study are promising, certain limitations have been identified that may affect their interpretation and limit the generalizability of the findings. The following limitations can be highlighted:

Preparation process limitations

One of the primary challenges was the material heterogeneity of the shredded composite (SC), which was derived from entire wind turbine blades without prior separation of their constituent materials. As a result, the SC comprised a mixture of glass fibres, epoxy resin, PVC foam, balsa wood, and other components. This variability introduced inconsistencies in the composition, making it difficult to standardize the mixture. In addition, the non-uniform geometry of the SC particles, particularly within the 0–32 mm fraction, may have caused inconsistencies. This may have impacted the dispersion of the particles within the cement matrix and the overall mechanical response. Furthermore, no chemical additives, such as plasticisers or modifiers were used, as the primary objective of the study was to isolate and highlight the effect of incorporating SC. Although this approach improves transparency when assessing the impact of the recyclate, it probably limits the potential for optimising workability and mechanical properties.

Measurement limitations

The digital image correlation (DIC) technique, which was used to analyse the crack pattern, was only applied to the front surface of the beam specimens. Consequently, it was not possible to fully capture the internal or three-dimensional fracture mechanisms. In addition, porosity measurements were performed using 2D optical microscopy on cross-sectional slices. Although this method provides valuable information, it does not fully capture the three-dimensional pore structure or pore interconnectivity.

Testing limitations

Only three beams per mix were tested, which may limit statistical robustness and generalizability of the results. Increasing SC content reduced the flowability of the mortar (e.g., from 11.75 cm in M.0 to 8.5 cm in M.II.40), potentially affecting compaction and homogeneity. Moreover, the study focused on flexural and compressive strength. Other relevant properties like shrinkage, modulus of elasticity, or impact resistance were not evaluated.

Conclusions

The research carried out provides important insights that can form the basis for further work on the use of shredded composite recycled form wind turbine blades in building materials. The main conclusions can be summarised as follows:

-

1.

Wind turbine blade recyclate can perform a variety of functions in cement mortars, depending on the fraction and method of application.

-

2.

The 0–32 mm fraction of the shredded composite exhibited better properties as an aggregate replacement due to its ability to fill intergranular spaces and create a fibre bridging effect. This resulted in a 23.22% reduction in porosity and a 6.51% decrease in density. Mechanically, it led to an increase in flexural strength of up to 36.51% and a compressive strength gain of 18.09% in the M.II.30 mixture. Moreover, the toughness index improved by 248.11%, reaching 5.53 kJ/m² in M.II.40, compared to 1.59 kJ/m² in the control mix, confirming the enhanced energy absorption and crack-bridging capacity provided by the longer fibres.

-

3.

The use of the 0–2 mm fraction of the shredded composite as a cement substitute led to a progressive increase in porosity and a reduction in density, indicating the need for further optimisation of this solution. Specifically, porosity rose from 3.23% in the control mix to 4.12% in M.I.20, representing a 27.55% increase, while density decreased from 2305.7 kg/m³ to 2153.5 kg/m³, a 6.60% reduction. These changes were accompanied by up to 45.12% drop in compressive strength (M.I.20) and a 31.48% decrease in flexural strength (M.I.20) and a 44.64% reduction in toughness index, highlighting the limited structural contribution of the fine SC particles in their current form.

-

4.

Fibres recovered from shredded WTBs showed good bonding to the cement matrix, confirming their potential as micro- and macro-structural reinforcements. However, the effective use of these fibres requires further research into their length, geometry and possible mechanical modification or chemical activation of the surface.

-

5.

Overall, the results of this study reinforce the conclusions of earlier works while providing novel insights through the application of digital image correlation for fracture monitoring. The incorporation of longer fibres from shredded composite not only enhances mechanical performance but also improves ductility and energy dissipation, making these composites particularly well-suited for dynamic load-bearing applications such as pavements and prefabricated infrastructure components.

To deepen the understanding of the impact of shredded fibres from wind turbine blades on the properties of cement mortars and concrete, further investigations should focus on chemical or physical surface modifications of the fibres. Such treatments could enhance the interfacial bonding between the recycled fibres and the cement matrix, potentially improving mechanical performance and durability. Additionally, comprehensive long-term durability studies are recommended. These should include assessments of resistance to cyclic freezing and thawing, chloride penetration or carbonation, which are critical factors influencing the lifespan and serviceability of cementitious composites in harsh environmental conditions. Exploring these areas will provide valuable insights into optimizing the use of wind turbine blade recyclate in sustainable construction materials.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hu, Y. et al. Wind turbine blade recycling: A review of the recovery and high-value utilization of decommissioned wind turbine blades. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 210, 107813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2024.107813 (2024).

Gennitsaris, S. & Sofianopoulou, S. Wind turbine end-of-life options based on the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs). Green. Technol. Sustain. 2, 100108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.grets.2024.100108 (2024).

Majewski, P., Florin, N., Jit, J. & Stewart, R. A. End-of-life policy considerations for wind turbine blades. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 164, 112538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112538 (2022).

Spini, F. & Bettini, P. End-of-Life wind turbine blades: review on recycling strategies. Compos. Part. B Eng. 275, 111290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2024.111290 (2024).

Fonte, R. & Xydis, G. Wind turbine blade recycling: an evaluation of the European market potential for recycled composite materials. J. Environ. Manage. 287, 112269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112269 (2021).

Lund, K. W. & Madsen, E. S. State-of-the-art value chain roadmap for sustainable end-of-life wind turbine blades. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 192, 114234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.114234 (2024).

Nagle, A. J., Delaney, E. L., Bank, L. C. & Leahy, P. G. A comparative life cycle assessment between landfilling and Co-Processing of waste from decommissioned Irish wind turbine blades. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 123321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123321 (2020).

Beauson, J., Laurent, A., Rudolph, D. P. & Pagh Jensen, J. The complex end-of-life of wind turbine blades: A review of the European context. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 155, 111847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111847 (2022).

Tyurkay, A., Kirkelund, G. M. & Lima, A. T. M. State-of-the-art circular economy practices for end-of-life wind turbine blades for use in the construction industry. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 47, 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2024.03.018 (2024).

Zhang, W., Yu, H., Yin, B., Akbar, A. & Liew, K. M. Sustainable transformation of end-of-life wind turbine blades: Advancing clean energy solutions in civil engineering through recycling and upcycling. J. Clean. Prod. 426, 139184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139184 (2023).

Delaney, E. L. et al. Sustainability implications of current approaches to end-of-life of wind turbine blades—A. Rev. Sustain. 15, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612557 (2023).

Joustra, J., Flipsen, B. & Balkenende, R. Structural reuse of wind turbine blades through segmentation. Compos. Part. C Open. Access. 5, 100137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomc.2021.100137 (2021).

Nagle, A. J., Mullally, G., Leahy, P. G. & Dunphy, N. P. Life cycle assessment of the use of decommissioned wind blades in second life applications. J. Environ. Manage. 302, 113994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113994 (2022).

Hasheminezhad, A., Nazari, Z., Yang, B., Ceylan, H. & Kim, S. A comprehensive review of sustainable solutions for reusing wind turbine blade waste materials. J. Environ. Manage. 366, 121735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121735 (2024).

Ruane, K. et al. Construction and cost analysis of bladebridges made from decommissioned FRP wind turbine blades. Sustain https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043366 (2023).

Pyrzowski, S. A., Kluska, J. & Zembrzuski, J. Stiffness assessment of the laminate recovered from end-of-life wind turbine blade. Compos. Struct. 348, 118439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2024.118439 (2024).

Alshannaq, A. A., Respert, J. A., Bank, L. C., Scott, D. W. & Gentry, T. R. Mechanical testing of connections blind bolted to the thick glass-fiber-reinforced polymer spar cap of a decommissioned GE37 wind turbine blade. J. Compos. Constr. 27, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1061/jccof2.cceng-4101 (2023).

Khalid, M. Y., Arif, Z. U., Hossain, M. & Umer, R. Recycling of wind turbine blades through modern recycling technologies: A road to zero waste. Renew. Energy Focus. 44, 373–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ref.2023.02.001 (2023).

Xu, Y., Wang, F., Liang, D., Lv, G. & Chen, C. A comprehensive review of waste wind turbine blades in china: Current status and resource utilization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 113077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.113077 (2024).

Jani, H. K., Singh Kachhwaha, S., Nagababu, G. & Das, A. A brief review on recycling and reuse of wind turbine blade materials. Mater. Today Proc. 62, 7124–7130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.02.049 (2022).

Xu, M. et al. Recovering glass fibers from waste wind turbine blades: Recycling methods, fiber properties, and potential utilization.. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2024.114690 (2024).

Liu, S., Guo, J. & Wu, C. Improving the pozzolanic reactivity of recycled powders from retired wind turbine blades by removing the polymer phase through thermal treatment. J. Build. Eng. 96, 110387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110387 (2024).

Yang, W., Kim, K. H. & Lee, J. Upcycling of decommissioned wind turbine blades through pyrolysis. J. Clean. Prod. 376, 134292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134292 (2022).

Muzyka, R., Sobek, S., Korytkowska-Wałach, A., Drewniak, Ł. & Sajdak, M. Recycling of both resin and fibre from wind turbine blade waste via small molecule-assisted dissolution. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36183-4 (2023).

Sobek, S. et al. A life cycle assessment of the laboratory—scale oxidative liquefaction as the chemical recycling method of the end-of-life wind turbine blades. J. Environ. Manage. 361, 121241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121241 (2024).

Correia, J. R., Almeida, N. M. & Figueira, J. R. Recycling of FRP composites: reusing fine GFRP waste in concrete mixtures. J. Clean. Prod. 19, 1745–1753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.05.018 (2011).

Li, X. et al. A systematic review of waste materials in cement-based composites for construction applications. J. Build. Eng. 45, 103447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103447 (2022).

Tao, Y. & Hadigheh, S. A. Enhancing the strength, microstructural integrity, and shrinkage performance of cement-based mortar using pulverised carbon and glass FRP composite waste. J. Build. Eng. 94, 110053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110053 (2024).

Priyan, M. V. et al. A study on waste PCB fibres reinforced concrete with and without silica fume made from electronic waste. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50312-z (2023).

Kanagaraj, B., Anand, N., Samuvel Raj, R. & Lubloy, E. Techno-socio-economic aspects of Portland cement, geopolymer, and limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) composite systems: A-State-of-Art-Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 398, 132484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132484 (2023).

Revilla-Cuesta, V., Skaf, M., Ortega-López, V. & Manso, J. M. Raw-crushed wind-turbine blade: Waste characterization and suitability for use in concrete production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.107160 (2023).

Revilla-Cuesta, V., Faleschini, F., Pellegrino, C., Skaf, M. & Ortega-López, V. Water transport and porosity trends of concrete containing integral additions of raw-crushed wind-turbine blade. Dev. Built Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dibe.2024.100374 (2024).

Ortega-López, V., Faleschini, F., Hurtado-Alonso, N., Manso-Morato, J. & Revilla-Cuesta, V. Analysis of raw-crushed wind-turbine blade as an overall concrete addition: Stress–strain and deflection performance effects. Compos. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2024.118170 (2024).

Trento, D., Faleschini, F., Revilla-Cuesta, V. & Ortega-López, V. Improving the early-age behavior of concrete containing coarse recycled aggregate with raw-crushed wind-turbine blade. J. Build. Eng. 92, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.109815 (2024).

Revilla-Cuesta, V., Manso-Morato, J., Hurtado-Alonso, N., Skaf, M. & Ortega-López, V. Mechanical and environmental advantages of the revaluation of raw-crushed wind-turbine blades as a concrete component. J. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.108383 (2024).

Fu, B. et al. Performance enhancement of recycled coarse aggregate concrete by incorporating with macro fibers processed from waste GFRP. Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134166 (2024).

Fu, B., Liu, K. C., Chen, J. F. & Teng, J. G. Concrete reinforced with macro fibres recycled from waste GFRP. Constr. Build. Mater. 310, 125063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125063 (2021).

Yazdanbakhsh, A., Bank, L. C., Rieder, K. A., Tian, Y. & Chen, C. Concrete with discrete slender elements from mechanically recycled wind turbine blades. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 128, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.08.005 (2018).

Nie, X. F., Fu, B., Teng, J. G., Bank, L. C. & Tian, Y. Shear behavior of reinforced concrete beams with GFRP needles. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119430 (2020).

Yazdanbakhsh, A., Bank, L. C. & Tian, Y. Mechanical processing of GFRP waste into large-sized pieces for use in concrete. Recycling https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling3010008 (2018).

Sorte, S. et al. Evaluating the feasibility of shredded wind turbine blades for sustainable Building components. J. Clean. Prod. 434, 139867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139867 (2024).

Baturkin, D., Hisseine, O. A., Masmoudi, R., Tagnit-Hamou, A. & Massicotte, L. Valorization of recycled FRP materials from wind turbine blades in concrete. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 174, 105807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105807 (2021).

Zhou, B., Zhang, M. & Ma, G. An experimental study on 3D printed concrete reinforced with fibers recycled from wind turbine blades. J. Build. Eng. 91, 109578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.109578 (2024).

Pławecka, K. et al. Recycling of mechanically ground wind turbine blades as filler in geopolymer composite. Mater. (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14216539 (2021).

Novais, R. M. et al. Incorporation of glass fibre fabrics waste into geopolymer matrices: an eco-friendly solution for off-cuts coming from wind turbine blade production. Constr. Build. Mater. 187, 876–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.08.004 (2018).

Sadrolodabaee, P., Claramunt, J., Ardanuy, M. & de la Fuente, A. Mechanical and durability characterization of a new textile waste micro-fiber reinforced cement composite for building applications. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 14, e00492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00492 (2021).

Kaboré, M. W. et al. Insights into the effect of recycled glass fiber reinforced polymer on the mechanical strengths of cement mortar. Eng 5, 2966–2977. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng5040154 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Financial support of these studies from Gdańsk University of Technology by the DEC-8/2022/IDUB/VHR grant under the VENTUS-HYDROGENII-REDIVIVUS - ‘Excellence Initiative - Research University’ program is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R. – Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigations, Formal analysis, Visualisation, Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.M.K. – Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources; Investigations, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rucka, M., Kurpińska, M. Sustainable cement-based mortar with shredded material recycled from end-of-life wind turbine blades. Sci Rep 15, 30685 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15364-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15364-3