Abstract

Coyotes are expanding their range throughout North America and are typically managed as a “nuisance” species in the U.S.A., where take is legally permitted anywhere, anytime, and no limitations on the number of coyotes any individual can kill. Recent interest surfaced in Ohio around limitations on coyote hunting, and to better understand support and opposition to such limits, we surveyed the public, agricultural producers, hunters, and fur takers regarding several coyote-related variables. We found disparities between public support for limitations and organized stakeholder groups opposition to limitations, highlighting a misalignment, yet likewise found some disagreement within organized stakeholder groups in their opposition to limitations. To understand potential drivers of these preferences, we used regression analyses predicting preferences as a function of emotions, risk and benefit perceptions, symbolic beliefs, and gender. We found for fur takers and producers, beliefs about risks, benefits, and symbolic existence of coyotes predicted their opposition to limitations, while for the public, perceptions of risk and benefit were not predictive of support for limitations. Our results suggest some potential for conflict around coyote management both within organized stakeholder groups themselves, who represent a small proportion of the public, and between these groups and the public writ large.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historically, coyotes (along with other species across space and time) have been treated as a “nuisance” species with very few restrictions on their killing1. Indeed, both state and federal governments in the US spent decades in a failed effort to eradicate coyotes2. Despite this historical context, the species proliferated and expanded its range in recent decades, moving into areas with human populations unaccustomed to living with them. This expansion is taking place within the broader societal context of shifting attitudes and values among their human neighbors, challenging a system of management that has traditionally depended upon the use of killing as a means of controlling unwanted interactions with wildlife. Recent research shows that positive attitudes toward coyotes in the U.S. have increased more than 40% since the late 1970s3. Both lethal and nonlethal carnivore management practices, in contrast, are increasingly viewed as inhumane and unacceptable by the U.S. public4.

More recently, a 2018 nation-wide study found that values regarding wildlife are also shifting in a manner that challenges the use of lethal measures of predator control5. This suggests that changes related to societal modernization (e.g., increasing urbanization, education, income) are prompting new ways of thinking about human-wildlife interactions. In effect, modernization is changing our environment (socially and economically) in a manner that promotes greater compassion for wildlife. However, other research suggests modernization is also reshaping how we interact with wildlife, especially carnivores. This research suggests that urbanization, combined with a variety of technological and lifestyle changes, collectively removed most people from most risk posed by these species. The lack of risk, combined with more general changes in values, makes carnivores easier to tolerate and conserve6. However, higher tolerance may come at a cost: a recent report on coyotes in urban areas raises the possibility that this shift in public values may be a driver of coyote habituation to humans in densely populated areas, potentially leading to more conflict7. Despite increasing interactions and even habituation, conflicts are relatively rare. Indeed, a study in Madison, WI found that the vast majority (90%) of urban coyote encounters were rated as “benign”8.

The recognition that not just attitudes and values, but the nature of human interactions with what are sometimes perceived as “nuisance” animals are changing is prompting efforts to understand the conditions under which people will continue to accept typical lethal management for coyotes, as well as factors that might predispose one to support or oppose certain types of controls. Those studies suggest that while attitudes towards coyotes have gotten more positive over time3 remaining negative attitudes, negative affect, and negative discrete emotions toward predator species still correlate to more support for lethal control9,10,11. Other studies have found that agreement with the rights of coyotes to exist on the landscape correlates with lowered perceived risks12 and less dislike of coyotes13 while decreased perceived risk and increased perceived benefits were found to correlate to more positive attitudes14. From a demographic perspective, women generally worry more about environmental risks15 yet men tend to report more support for lethal control of coyotes10,11,16 suggesting some gendered differences in the perceptions of risks of coyotes and preferred mitigation practices. Few studies have examined attitudes toward generalized coyote harvest practices (i.e., hunting, trapping) that may mitigate conflict, though broadly, the public tends to disagree that predator control is unacceptable4,17 suggesting some nuance in the public’s relationship to nuisance carnivores.

Although numerous studies have examined support for lethal control of predators in various conflict scenarios, far more coyotes are killed each year in sport hunting, and yet we could only find one study that dealt specifically with public support for coyote hunting. In that case, a survey of residents in Cape Cod, Massachusetts concerning the acceptability of coyote hunting practices found low levels of support for both baiting and policy that would allow unlimited harvest (i.e., no “bag” limits)18. Here, we consider a suite of variables typically found to influence preferences for carnivore management, but unlike previous work, we focus on predicting preferences for a reduction of coyote killing via more restrictive hunting and trapping regulations. Further, this research is unique in terms of its scope: we consider preferences among three organized stakeholder groups with direct interests in coyote management (i.e., hunters, fur takers, and producers), and compare their responses to the preferences of the general public to determine the potential for conflict over coyote management policies.

Methods

Study context: proposed regulatory changes to coyote management in Ohio

In January of 2020 the Ohio Wildlife Council (the state’s regulatory decision-making body for wildlife matters) considered a proposal to revise coyote trapping regulations as part of its annual regulatory review. That proposal would have required coyote trappers to possess a furbearer’s permit and put some modest restrictions on the harvest of coyotes. Currently coyotes can be taken without a furbearer license at any time of the year by means of trap or firearm; one need only possess an Ohio hunting license. Based on input received through the regulatory process, the Wildlife Council chose to ‘table’ the proposed regulatory changes to collect and consider more information. Shortly thereafter, legislators in the Ohio Assembly introduced House Bill 553 (HB 553), which would have reduced the state Division of Wildlife’s authority over coyotes by amending existing statutory law to explicitly state that (a) a fur taker’s (i.e., trapping) permit would not be required to trap coyotes, and (b) there could be no closed season on coyotes. These efforts prompted us to conduct a survey to determine public support and opposition to restrictions on coyote harvest in Ohio to quantify (1) support/opposition for limits to hunting and trapping coyotes in Ohio among portions of the public and the public as a whole, and (2) assess associations of factors previously found in the literature to impact support/opposition to this method of lethal management.

Sampling

We sampled four populations important to coyote management in Ohio: adult residents of Ohio (hereafter, public sample; The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board approval #2021E1084), Ohio hunters and fur takers (#2021E1132), and Ohio residents involved in agricultural production (including livestock and grain producers, hereafter, producer sample; #2021E0041). The public sample was drawn from Qualtrics panels of survey takers residing in Ohio, surveyed from November 19–23, 2021, and were weighted post hoc to reflect the statewide distribution of gender. We did not remove respondents from the Qualtrics sample who indicated hunting or farming but rather left them in the sample for subsequent analyses to provide an appropriate reflection of the public overall. Separately, hunters and fur takers were randomly drawn from the Ohio Division of Wildlife’s database of license and permit holders with email addresses on file and surveyed via the Qualtrics platform from December 13–23, 2021. License and permit holders were only included in the final sample if they indicated ever hunting in the past. Finally, producers were sampled via convenience samples gathered from readers of four rural- and production-focused publications: Buckeye Farm e-News, Ohio Ag News, and readers of the Ohio State Sheep and the Beef Teams Extension Newsletters. Ads and notifications for the survey hosted on the Qualtrics platform ran from January 18, 2022 to February 18, 2022. Respondents from the rural convenience sample were only included in the final sample if they responded that they operated a farm (defined as >$1000 in revenue per year) or owned land in Ohio that is used for production agriculture. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations per institutional approvals, and as such, all respondents received informed consent information at the survey start. Any respondents who answered the embedded attention check question incorrectly were removed from analyses.

Analysis

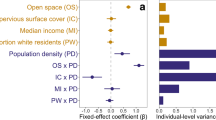

We assessed many variables of interest in the survey19 but limit our analyses here to assessing support for and opposition to hunting and trapping of coyotes among the public and three groups of interest. We used the updated version (PCI2) of the potential for conflict index (PCI)20 —an analysis that allows for the graphical representation of the potential for conflict both within and between groups— to visually assess the dispersion around support for and opposition to specific limitations on hunting and trapping of coyotes. The PCI221 can indicate the amount of within-group variation for a given policy, and place it in relation to the preferred response of other groups. Larger circles in these graphs indicate greater variation within a group, while the placement of the circle on the y-axis of the graph indicates the average level of support or opposition for a given group. (Additionally, we chose to turn these typically single-color circles into pie charts indicating the distribution of responses for each group included in the PCI2 analyses, providing a snapshot of comparisons across the samples and items of interest.)

To understand the potential correlates of support and opposition to limitations to these practices for each group sampled, we assessed positive and negative emotions related to coyote presence, perceptions of risks and benefits of coyote presence, and agreement with symbolic existence beliefs (items, means, and standard deviations can be found in Tables 1 and 2). Individual items were averaged for each variable to create composite scores for negative and positive emotions, perceptions of risks and perceptions of benefits, symbolic existence beliefs, and general support/opposition to limitations on coyote hunting and trapping. Given the differing sampling techniques, we used a MANOVA to probe the potential for differences between samples on the variables of interest, and given a finding of significant differences in the MANOVA, we maintained separate samples and ran separate linear regression analyses for each group. To better understand results from the regression analyses and probe explanations for differences due to rural perspectives, we ran post hoc analyses of the public data separately, dividing public respondents into urban and rural segments based on their responses to the question: How would you describe the community in which you live? Respondents could select urban, suburban, small town/village, rural (non-agricultural), or rural (farming/agricultural). We lumped respondents in the public sample who selected “urban” or “suburban” together under an “urban” category, and the remaining three responses under a “rural” category. We then conducted t-tests to probe potential differences in preferences for limitations between the groups. Analyses creating the PCI2 were conducted in Microsoft Excel using a standardized worksheet (https://sites.warnercnr.colostate.edu/jerryv/potential-conflict-index/), while all other analyses were performed in IBM SPSS v.28.

Results

The public was generally split in their support for government-regulated hunting and trapping of coyotes, while all organized stakeholder groups (i.e., hunters, fur takers and producers) were supportive of both activities (Fig. 1). With regards to potential changes to government regulations on hunting and trapping, majorities of the public supported limitations on these activities, while majorities of organized stakeholder groups opposed these limitations (Fig. 2). Moreover, PCI2 values indicate the public was more cohesive in their support (PCI2 = 0.17–0.25) than other groups were in their opposition (PCI2 = 0.25–0.50). All three organized stakeholder groups exhibited moderate opposition to season limitations, with higher levels of dispersion (within-group disagreement) indicating greater potential for conflict within the groups themselves. Conversely, the public was neutral to opposing of eliminating all hunting restrictions for coyotes (Fig. 2), while organized stakeholder groups were neutral to supportive. Again, the PCI2 values, which indicate levels of disagreement within groups, show that fur takers (PCI2 = 0.40), hunters (PCI2 = 0.38), and producers (PCI2 = 0.46) exhibit greater disagreement within their groups in supporting elimination of hunting restrictions than the public (PCI2 = 0.23). Finally, post hoc t-tests assessing differences in support for limitations between rural and urban respondents within the public sample yielded no significant differences.

Potential for Conflict Index (PCI2) for limiting seasons or number of coyotes that can be hunted or trapped, and for eliminating all hunting restrictions by sample. Each bubble represents a pie chart of responses for each sample where the light green portion includes both “support” and “strongly support” responses, the medium gray portion represents “neither support nor oppose” responses, and the dark red portion includes both “oppose” and “strongly oppose” responses. Numbers under each bubble indicate the mean for each sample (responses were on a 5-point scale of −2 to 2) and the PCI2 value (higher numbers indicate higher dispersion around the mean and greater disagreement within the group).

We conducted a MANOVA to assess differences between samples on the composite variables prior to running regression analyses. Box’s test was significant, suggesting unequal covariance matrices, so we used Pillai’s trace to assess significant differences22. Pillai’s trace results suggest significant differences between the samples for perceptions of risk, perceptions of benefit, symbolic beliefs, and support for limitations on coyote hunting and trapping (V = 0.40, F(18, 4146) = 35.53, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.13; Table 3). Given the differences found in the MANOVA, we ran separate linear regression analyses using the same model for each sample predicting overall support for limitations on coyote hunting and trapping. The model was significant for each sample, and explained the least variation within the public sample (R2 = 0.11) and the most variation within the producer sample (R2 = 0.44; Table 4). Significant independent variables varied by group; however, disagreement with items indicating that coyotes can be beneficial significantly explained opposition to limitations among fur takers, hunters, and producers (though not the public). The perceived benefits of coyotes were especially important in explaining support for harvest limitations among hunters (β = 0.34). Similar to previous research, reporting one’s gender as male significantly explained opposition to limitations among producers (β= −0.28), but was only weakly (non-significantly) related to opposition for other groups.

Discussion

Social scientists have long recognized that the forces of modernization are reshaping social values in a manner that emphasizes self-expression and egalitarianism23,24. Likewise, increasing evidence suggests these forces are also reshaping how we value wildlife and perceive (as appropriate or not) their treatment5. In particular, studies suggest that as values change, people are more likely to moralize wildlife25 and less likely to support lethal means of controlling wildlife populations4. These conditions challenge agencies long accustomed to relying primarily on lethal tools to control wildlife and their deleterious effects.

Our research sought to compare attitudes toward restricting coyote harvest across various interested groups. We found hunters, fur takers and producers expressed similar attitudes toward these restrictions, with roughly three in five hunters and producers opposing restrictions, while more than four in five fur takers opposed these restrictions. In contrast, only about one in four of the public sample opposed these restrictions. And as reflected in Fig. 2, while there was greater support than opposition in the public sample, more than one in three expressed neutrality toward restricting either hunting or trapping. Neutrality may reflect either apathy (a lack of care) or ambivalence (conflicting feelings of positive and negative that get reported as neutral), but in either case, there is the possibility that this portion of the public is most open to arguments for or against such restrictions. The importance of these differences is underscored by the fact that our public sample did not exclude hunters, trappers or producers.

Interestingly, we found no differences between the public and specific stakeholder groups’ positive and negative emotions toward coyotes; however, the public held lower risk perceptions, higher perceptions of benefit, and more agreement with existence beliefs than the groups surveyed here. Notably, hunters reported similar agreement with existence beliefs as the public, potentially resulting from a conservation ethic that may be prevalent among some groups of hunters26.

Our regression analyses suggest that psychological factors influencing attitudes towards limiting harvest of coyotes differed between groups, but like previous research9,13 symbolic existence beliefs played an important role for the public’s attitudes towards limitations on the lethal management of coyotes. While previous research found perceptions of benefits are associated with more positive attitudes towards coyotes and lower perceptions of risks of coyotes among public samples12,14 we found these factors were associated with support for limitations only among organized stakeholder groups–not the public. Perceptions of benefits of coyotes played a consistent role in predicting support for (or conversely, opposition to) limitations among organized stakeholder groups, such that reduced perceptions of benefits led to increased opposition to limitations. Similar to Nardi et al.14 and Frank et al.13 gender (when included with other variables in the regression model) did not correlate with public support for limitations here; however, gender significantly impacted producer perceptions of limitations in a predictable pattern—males were less supportive of limitations than any other gender10,11,16 (i.e. females, non-binary or prefer not to say). Finally, risk perceptions significantly impacted fur taker and producer attitudes toward limitations, such that increased risk perceptions related to greater opposition to limitations on coyote hunting and trapping. Frank et al.13 and Nardi et al.14 found that increased risk perceptions explained more negative attitudes toward coyotes among their public samples, however we found no relationship for our public sample.

The general public may indeed be shifting toward more mutualist orientations to wildlife, and likewise have preferences for on the ground management that bring those orientations to the forefront of how we interact with “nuisance” species like coyotes. However, groups who claim to be directly impacted by or who themselves directly impact coyotes (i.e. producers, fur takers, and hunters) do not support curtailed hunting and trapping practices, and in our regression analyses, these preferences were related to the risks and benefits perceived by these groups. These findings echo previous work on wolves, where a public physically distanced from the risks of wolves typically thought of the animals in an abstract, positive light, but respondents from areas closer to wolf territory relayed more concrete, negative perspectives27. For individuals more directly impacted by wildlife and wildlife-related policies, it seems that the contextual details are driving their preferences for management; when considering which social science theories to employ in future work with similar communities, models incorporating strongly context-dependent variables28,29,30,31 may be most appropriate. Conversely, when considering broad public perspectives on wildlife management, hazard models may be less appropriate or predictive32 and a focus on more abstract values may prove more useful for explaining preferences at a broader, societal scale5. That said, we would be remiss to ignore the portions of the broader public who are not directly negatively impacted by wildlife but who care passionately about the conservation of certain species, for whom hazard models seem to predict sizeable variation in their intentions to conserve wildlife33. Certainly, researchers could attempt to craft or assess a one-size-fits-all approach, but survey length and respondent attention limitations may limit the practicability of such an approach.

Our results suggest there is substantial potential for social conflict over the coyote issue, however, it is possible that existing management practices, which are greatly constrained in urban areas by ordinances, may already meet public needs to some extent. High population and road densities limit coyote hunting in cities where most of the public lives (and prefer limitations on hunting and trapping), while largely unlimited hunting practices are both permitted and practiced in areas with lower human and road densities, where agricultural production, hunting and trapping are more prevalent. This idea—that is, the idea that coyote management policies reflect ‘local preferences’—implies a rural-urban split in preferences, whereby rural preferences align with those of largely rural stakeholder groups. However, we found rural and urban residents in our public sample did not differ when it comes to preferred coyote policy. Thus, in contrast to literature suggesting that social conflicts over wildlife originate from rural-urban differences, our data suggests the conflict lies between the public at large and vested interest groups –i.e., hunters, fur takers and farmers.

A broader issue arises from the current governance of wildlife, which has long favored hunting, and to a lesser extent, agricultural interests. The favoritism is built into political decision-making bodies (i.e., wildlife commissions, boards) which tend to be comprised of hunters34. Unfortunately, the method of funding state wildlife agencies in the U.S. effectively promotes game favoritism. That is, by tying funding for wildlife conservation to sport hunting through excise taxes on firearms and hunting-related equipment, the U.S. system appears designed to favor these interests35 (see Bruskotter et al. 2025). Whether such favoritism is so egregious as to qualify as “agency capture” -- whereby agencies abandon portions of their mission to meet the demands of favored interest groups (Fortman 1990) – is open to debate. The issue arises when one considers the relatively small proportion of the population that engages in these activities. The USDA estimates that in 2023, the state of Ohio had some 75,800 farms35. Even if there were 5 farmers for every farm, the proportion of Ohio’s population comprised of farmers would be just 3.2%. The proportion of the population that hunts is similarly small. According to the Ohio Division of Wildlife38 there were 321,385 residents licensed to hunt in Ohio in the 2022/2023 season, representing 2.7% of the population, and just 11,789 purchased fur-taker permits for trapping (less than 1/100th of a percent of Ohio’s population). Given that our data show that the public favors limitations on coyote harvest—limitations the agency has yet to adopt—it seems fair to conclude that the interests of a small minority are driving coyote management policy in Ohio.

Nevertheless, the lack of action concerning coyote harvest policy since these data were collected could be taken to imply a general lack of public interest in the issue. That lack of interest may stem from the existing policies that effectively give both sets of interested groups what they desire, at least where they primarily reside. That is, local ordinances in urban and suburban areas that prohibit the use of traps and discharge of firearms prevent coyote harvest as well as lethal control across portions of the state where the vast majority of residents live. While in contrast, the virtual lack of regulation on coyote harvest and control apply in the rural areas where people tend to hunt, trap and raise livestock. Yet, the long-term declines in hunting and agriculture witnessed in the state over past decades raise questions about the capacity of organized interest groups to continue to exert their will on wildlife policy, and as highlighted elsewhere39 wildlife management agencies can expect continued pressure to shift management approaches in light of wider societal changes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15496548.

References

Brookshire, B. Pests: How Humans Create Animal Villains (HarperCollins, 2022).

deCalesta, D. Predator control: history and policies. Or. State Univ. Ext. Service Ext. Circular. 710-B, 2 (1976).

George, K. A., Slagle, K. M., Wilson, R. S., Moeller, S. J. & Bruskotter, J. T. Changes in attitudes toward animals in the united States from 1978 to 2014. Biol. Conserv. 201, 237–242 (2016).

Slagle, K., Bruskotter, J. T., Singh, A. & Schmidt, R. H. Attitudes toward predator control in the united states: 1995 and 2014. Journal Mammalogy 98, (2017).

Manfredo, M. J. et al. The changing Sociocultural context of wildlife conservation. Conserv. Biol. 34, 1549–1559 (2020).

Bruskotter, J. T. et al. Modernization, risk, and conservation of the world’s largest carnivores. BioScience 67, 646–655 (2017).

Curtis, P. D. et al. Urban Coyotes as a source of conflict with humans: an evaluation of common management practices. Human–Wildlife Interact. Monogr. 5, 1–54. https://doi.org/10.15142/XP62-S095 (2025).

Drake, D., Dubay, S. & Allen, M. L. Evaluating human–coyote encounters in an urban landscape using citizen science. J. Urban Ecol. 7, juaa032 (2021).

Sponarski, C. C., Vaske, J. J. & Bath, A. J. The role of cognitions and emotions in human–coyote interactions. Hum. Dimensions Wildl. 20, 238–254 (2015).

Drake, M. D. et al. How urban identity, affect, and knowledge predict perceptions about Coyotes and their management. Anthrozoös 33, 5–19 (2020).

Draheim, M. M., Parsons, E. C. M. & Crate, S. A. & Rockwood, L. L. Public perspectives on the management of urban Coyotes. Journal Urban Ecology 5, (2019).

Sponarski, C. C., Miller, C. A., Vaske, J. J. & Spacapan, M. R. Modeling perceived risk from Coyotes among Chicago residents. Hum. Dimensions Wildl. 21, 491–505 (2016).

Frank, B., Glikman, J. A., Sutherland, M. & Bath, A. J. Predictors of extreme negative feelings toward Coyote in Newfoundland. Hum. Dimensions Wildl. 21, 297–310 (2016).

Nardi, A., Shaw, B., Brossard, D. & Drake, D. Public attitudes toward urban foxes and coyotes: the roles of perceived risks and benefits, political ideology, ecological worldview, and attention to local news about urban wildlife. Hum. Dimensions Wildl. 25, 405–420 (2020).

Gustafsod, P. E. Gender differences in risk perception: theoretical and methodological perspectives. Risk Anal. 18, 805–811 (1998).

Martinez-Espineira, R. Public attitudes toward lethal Coyote control. Hum. Dimensions Wildl. 11, 89–100 (2006).

Reiter, D., Brunson, M. & Schmidt, R. H. Public attitudes toward wildlife damage management and policy. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 27, 746–758 (1999).

Jackman, J. L. & Way, J. G. Once I found out: awareness of and attitudes toward Coyote hunting policies in Massachusetts. Hum. Dimensions Wildl. 23, 187–195 (2018).

Slagle, K. & Bruskotter, J. T. Coyotes in Ohio: A Survey of Residents, Hunters, Fur Takers, and Agricultural Producers. (2023). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.28929.12643/1

Manfredo, M. J., Vaske, J. J. & Teel, T. L. The potential for conflict index: A graphic approach to practical significance of human dimensions research. Hum. Dimensions Wildl. 8, 219–228 (2003).

Vaske, J. J., Beaman, J., Barreto, H. & Shelby, L. B. An extension and further validation of the potential for conflict index. Leisure Sci. 32, 240–254 (2010).

Tabachnick, B. & Fidell, L. Using Multivariate Statistics (Pearson, 2013).

Inglehart, R. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton University Press, 1997).

Inglehart, R. & Welzel, C. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: the Human Development Sequence (Cambridge University Press, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790881

Bruskotter, J. T. et al. Support for the U.S. Endangered species act over time and space: controversial species do not weaken public support for protective legislation. Conserv. Lett. 11, e12595 (2018).

Bruskotter, J. T. et al. Conservationists’ moral obligations toward wildlife: values and identity promote conservation conflict. Biol. Conserv. 240, 108296 (2019).

Slagle, K. M., Wilson, R. S., Bruskotter, J. T. & Toman, E. The symbolic wolf: A construal level theory analysis of the perceptions of wolves in the united States. Soc. Nat. Resour. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2018.1501525 (2018).

Bruskotter, J. T. & Wilson, R. S. Determining where the wild things will be: using psychological theory to find tolerance for large carnivores. Conserv. Lett. 7, 158–165 (2014).

Kansky, R., Kidd, M. & Knight, A. T. A wildlife tolerance model and case study for Understanding human wildlife conflicts. Biol. Conserv. 201, 137–145 (2016).

Lischka, S. A. et al. Psychological drivers of risk-reducing behaviors to limit human–wildlife conflict. Conserv. Biol. 34, 1383–1392 (2020).

Ceauşu, S., Graves, R. A., Killion, A. K., Svenning, J. & Carter, N. H. Governing trade-offs in ecosystem services and disservices to achieve human–wildlife coexistence. Conserv. Biol. 33, 543–553 (2019).

Slagle, K. M., Wilson, R. S. & Bruskotter, J. T. Tolerance for wolves in the united States. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 817809 (2022).

Slagle, K. M., Bruskotter, J. T. & Wilson, R. S. The role of affect in public support and opposition to Wolf management. Hum. Dimensions Wildl. 17, 44–57 (2012).

Metcalf, J. D., Karns, G. R., Gade, M. R., Gould, P. R. & Bruskotter, J. T. Agency mission statements provide insight into the purpose and practice of conservation. Hum. Dimensions Wildl. 26, 262–274 (2021).

Bruskotter, J. T., Elbroch, L. M. & Vucetich, J. A. Government agencies in the united States are obstructing native species restoration, creating regulatory pits for wildlife. BioScience, biaf116 (2025).

Fortmann, L. The role of professional norms and beliefs in the agency-client relations of natural resource bureaucracies. Natural Resour. Journal, 361–380 (1990).

United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service. Ohio Farm Numbers. (2024). https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Ohio/Publications/Current_News_Releases/2024/nr2410oh.pdf

Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Wildlife. License Year Sales Comparison. through 2022. (2013). https://dam.assets.ohio.gov/image/upload/ohiodnr.gov/documents/wildlife/historic-licenses/Pub%205063%20(2013-2022).pdf (2023).

Decker, D. J. et al. Moving the paradigm from stakeholders to beneficiaries in wildlife management. J. Wildl. Manag. 83, 513–518 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the Lukuru Wildlife Research Foundation. We wish to acknowledge the assistance of Thomas P. Butler IV, CWB® of USDA APHIS Wildlife Services, Braden J. Campbell, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, State Small Ruminant Extension Specialist, and Jo Thompson, Ph.D., President and Executive Director, Lukuru Wildlife Research Project for their help in conceiving the study and drafting the survey.

Funding

for this research was provided by the Lukuru Wildlife Research Foundation. We wish to acknowledge the assistance of Thomas P. Butler IV, CWB® of USDA APHIS Wildlife Services, Braden J. Campbell, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, State Small Ruminant Extension Specialist, and Jo Thompson, Ph.D., President and Executive Director, Lukuru Wildlife Research Project for their help in conceiving the study and drafting the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.B. conceived the study, K.S. and J.B. designed the surveys, K.S. conducted the surveys, K.S. analyzed the results. K.S. and J.B. wrote the main manuscript text, J.B. prepared figure 2, and K.S. prepared figure 1 and all tables. Both authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.S. and J.B. have previously received support for their research from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Wildlife, and received support for the current study from the Lukuru Wildlife Research Foundation. J.B. has also provided scientific advice to Project Coyote.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Slagle, K., Bruskotter, J. Public support for restrictions on the killing of coyotes at odds with organized stakeholder group preferences for management. Sci Rep 15, 29684 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15378-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15378-x