Abstract

We utilized the forward transmission matrix method (FTMM) to theoretically examine the transmission and reflection characteristics of distributed feedback chirped grating structures based on graphene arrays. These chirped gratings are formed by embedding single-layer graphene sheets in a bulk substrate in a non-periodic arrangement, with a consistent difference in the spatial period between adjacent graphene sheets. The entire system exhibits central symmetry. When light is incident on this chirped system, it facilitates a multi-mode resonant output. One can control the bandwidth, transmittance and cutoff wavelength of the resonances by adjusting the chemical potential of graphene, the spatial period of the chirped gratings, and the number of spatial periods. This research may provide potential applications for the development of photonic low-pass multi-wavelength selectors and filters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bragg gratings, created through the periodic modulation of material refractive indices or system spatial structures, play a pivotal role in optical communication1,2, sensing3, and signal processing4,5. The periodic refractive index pattern in these gratings can be achieved using a photosensitive mask. This mask, with spatially distributed periodic transmittable fringes, covers the host material of the Bragg gratings, such as photosensitive glass. Upon exposure to ultraviolet light, the periodic refractive index is induced6.

Furthermore, by alternately arranging two materials with differing refractive indices along the horizontal coordinate, a periodic structure is formed, known as a general Bragg grating or a one-dimensional periodic photonic crystal7. These photonic crystals exhibit a photonic band structure analogous to the energy bands of electrons in semiconductors. Within wave-vector space, numerous discrete photonic bandgaps exist, each positioned between two contiguous transmission photonic bands8. Light waves whose wavelengths fall within these photonic bandgaps are unable to transmit through the photonic crystals and are instead completely reflected. Consequently, photonic bandgaps function as stopbands for light waves, making them ideal for photonic filter applications9,10. When two identical Bragg gratings are positioned on either side of a bulk dielectric, they form distributed feedback Bragg gratings, commonly used in wavelength selectors11. However, Bragg gratings exhibit a periodic distribution in space, which results in unitary transmission modes for wavelength selectors based on distributed feedback Bragg gratings.

A chirped grating is characterized by a spatially varying period, implying that its grating period is not constant but rather a function of position. Such gratings find extensive applications in optical filters12, fiber lasers13, and sensors14. Nevertheless, once these devices are fabricated, their stopband width and center frequency become fixed, limiting their adjustability in specific operational contexts. Graphene stands out as an exceptional two-dimensional material, boasting superior mechanical properties15 and superconducting capabilities16. Graphene-based photonic crystals have been extensively researched17, encompassing various phenomena such as solitons18,19, supermodes20,21, optical bistability22, and Rabi oscillations23,24. Notably, the optical properties of these crystals are dependent on the surface conductivity of graphene, which can be tuned by adjusting the chemical potential of the graphene. In practical applications, the graphene chemical potential can be altered through methods such as applying an external gate voltage to the graphene or through chemical doping25. Consequently, the characteristics exhibited by graphene-based photonic crystals can be flexibly controlled by manipulating the chemical potential of graphene.

Photonic crystals utilizing graphene arrays are constructed by periodically arranging a monolayer of graphene in the horizontal direction26. These crystals also exhibit a photonic bandgap structure within wave vector space. When compared to mono-layer graphene, photonic crystals composed of pairs of graphene layers demonstrate a more pronounced resonance of light waves27, leading to a more intense reflected light within the stopbands. Consequently, the bandgap edges become steeper, and the extinction effect at these edges is improved. Moreover, in graphene-based photonic crystals, the widths of the photonic stopbands can be adjusted flexibly by modifying the chemical potential of the graphene. Notably, the ability to regulate the photonic bandgap is further enhanced in the complex structure of graphene arrays, as compared to single-layer graphene photonic crystals28. Therefore, it is highly desirable to explore the photonic bandgap properties and their optical tunability in photonic crystals composed of graphene arrays.

We have investigated the optical behavior of a complex system composed of a dielectric and a graphene array in the communication wavelength band. In this system, graphene sheets are arranged in a non-periodic manner on the substrate material, forming a chirped grating structure. This unique design includes two chirped gratings, which are symmetrically deployed on either side of the defect layer. In the transmission spectrum of the system, a series of resonance peaks were observed. The bandwidth, transmittance, number, and cutoff wavelength of these peaks can be controlled by adjusting the chemical potential of graphene, the spatial period length of the chirped grating, and the number of periods. This work has potential applications in optical multi-wavelength selectors.

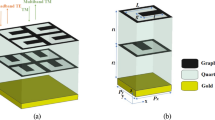

Distributed feedback chirped grating of graphene arrays

The structure of the distributed feedback chirped grating incorporating a graphene array is depicted in Fig. 1. A monolayer of graphene is embedded within dielectric material B, forming two symmetric chirped gratings, represented by M. These gratings are positioned at the ends of the defect layer C and are symmetrical with respect to the center of C. Dielectric material A is situated on the incident and exit sides. A chirped grating is characterized by its non-periodic nature. The spatial period between adjacent graphene layers varies by a constant increment. Within the chirped grating, the B-type dielectric layers interspersed between adjacent graphene arrays are sequentially labeled from the center outward as \(\:{B}_{1}\), \(\:{B}_{2}\), L, \(\:{B}_{\text{N}}\), where N denotes the spatial period number of the chirped grating, L represents \(\:{B}_{3}\), …, \(\:{B}_{\text{N}-1}\).

The materials for dielectrics A, B, and C are all silicon dioxide, with a refractive index of n = 1.449. The thicknesses of dielectrics A and C are denoted as \(\:{d}_{\text{A}}\) and \(\:{d}_{\text{C}}\), respectively, and the thickness of the ith B-type dielectric layer \(\:{B}_{\text{i}}\) is \(\:{d}_{\text{i}}\), representing the spatial period of the chirped grating, with the difference between two adjacent spatial periods being a constant di − di+1 = Δd. The entire structure is symbolized as AGBNGBN-1GLGB2GB1GCGB1GB2GLGBNGA。.

Graphene, as an ultrathin two-dimensional nanomaterial, is commonly regarded as an equivalent dielectric layer with a certain thickness \(\:{d}_{g}\). This equivalent approach is valid when \(\:{d}_{g}<1\:nm\), a condition that has been well-supported by extensive experimental and simulation studies. Its refractive index can be characterized by its conductivity:

Here, \(\:{k}_{0}=\frac{2{\uppi\:}}{{\uplambda\:}}\) denotes the wave vector in vacuum, \(\:{\eta\:}_{0}\) is the optical impedance in vacuum, \(\:i\), \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{g}\:\)and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{1}\) are the imaginary unit, the effective permittivity and the total surface conductivity, respectively.

Graphene is an ultra-thin two-dimensional material with unique conductivity. Its surface conductivity is determined by the Kubo formula29:

where \(\:{f}_{d}=1/\left(1+\text{exp}\left[\left(\epsilon\:-\mu\:\right)/{k}_{B}{T}_{g}\right]\right)\) is the Fermi-Dirac function, \(\:\epsilon\:\) is the particle energy, \(\:\mu\:\) is the chemical potential of graphene, \(\:{T}_{g}\) is the temperature, \(\:e\) is the electron element charge, and \(\:\tau\:\) is the relaxation time. \(\:\omega\:\), \(\:\hslash\:\) and \(\:{k}_{B}\) represents the angular frequency, the Plank’s constant and the Boltsmann’s constant respectively. The environment temperature is set as \(\:{T}_{g}\) = 300 K. The initial component of Eq. (2) signifies the intraband electron-photon scattering mechanism, derivable through integration

The subsequent term in Eq. (2) denotes the interband electron transition. Under the condition where \(\:\hslash\:\omega\:\) is significantly larger than \(\:{k}_{B}\), specifically when \(\:\left|\mu\:\right|\) ≫ \(\:{k}_{B}{T}_{g}\), this term can be approximated as follows

In the distributed feedback chirped grating structure incorporating graphene arrays, light typically enters from the left and transmits to the right. After disregarding the nonlinear effects of light, we employed the Forward Transfer Matrix Method (FTMM) to calculate the linear transmission and reflection spectra of the periodic system30.

The chemical potential of graphene corresponds to its Fermi level, which can be controlled through chemical doping or by applying an external gate voltage. When a positive voltage is applied to graphene, its chemical potential increases, whereas a negative voltage bias results in a decrease in the chemical potential. Consequently, the surface conductivity of graphene can be flexibly modulated using a bias voltage.

Numerical results

In this structure, we set \(\:{d}_{\text{A}}\) = 2 nm, \(\:{d}_{\text{C}}\) = 16 nm, \(\:{d}_{1}\) = 300 nm, \(\:{d}_{2}\) = 290 nm, …, \(\:{d}_{\text{N}}\) = 100 nm, indicating that the thickness difference between adjacent layers of B-type dielectric is Δd = 10 nm. Assuming the input wave is a transverse electric wave and is incident vertically onto the multilayer structure. Nonlinear effects are neglected, and the chemical potential of graphene is set to µ = 0.2 eV (eV denotes electron volts). The red solid line in the figure represents the transmittance T, while the green dashed line represents the reflectance R. From Fig. 2, it is evident that as the wavelength changes, multiple resonance peaks emerge on the transmission curve, indicating multimodal resonance. The spacing between adjacent resonance peaks increases from left to right, and the peak values of these peaks gradually decrease. As the incident light wavelength continues to increase, the transmittance is cut off.

In Fig. 2a, when λ = 1.025 μm, there is an upward jump in the transmission curve, with the rate increasing from 0.47 to about 0.84. In the shorter wavelength region (0–20 μm), the transmittance exhibits significant fluctuations. At approximately 32 μm, a pronounced peak in transmittance is observed. Additionally, a secondary peak is discernible at around 62 μm, albeit with a smaller magnitude. In Fig. 2b, when the number of spatial periods of the chirped grating increases to N = 40, at λ = 1.025 μm, there is an upward jump in the transmission curve, with the rate increasing from 0.26 to about 0.88. As the wavelength increases, the transmittance of the resonance peaks decreases significantly, and the cutoff wavelength of the transmittance decreases. Compared to Fig. 2a, Fig. 2b exhibits increased fluctuation in the shorter wavelength region (0–20 μm). In Fig. 2c, when the number of spatial periods of the chirped grating increases to N = 60, at λ = 1.025 μm, there is an upward jump in the transmission curve, with the rate increasing from 0.14 to about 0.82. Within the wavelength range of 0 to 20 μm, the fluctuation of transmittance further increases, revealing a greater number of peaks. As the wavelength increases, the transmittance of the resonance peaks decreases more significantly compared to Fig. 2b, the transmission curve becomes steeper. This is attributed to the fact that, with the increase in the number of chirped grating periods, the resonance is enhanced while the loss in graphene also increases. When N increases from 20 to 60, the number of resonance peaks increases from 92 to 139. The green dashed line on the right side of Fig. 2 represents the reflectance curve, which forms a complementary relationship with the transmission curve on the left. Specifically, where the transmittance is high, the reflectance is low; where the transmittance peaks, the reflectance dips; as the wavelength changes, when the transmittance decreases, the reflectance increases; when the transmitted light is completely cut off, the reflected light intensity is at its maximum, and if the loss is not considered, the maximum reflectance is 1.

In the graphene array, numerous resonant cavities exist. Resonance occurs when the wavelength of the incident light wave precisely meets the resonance condition, indicating the presence of a resonant mode. As the incident light wavelength increases, the resonance conditions are no longer satisfied, and due to the surface current in graphene, the transmittance sharply decreases until it is cut off. This suppression of long wavelengths results in a cutoff wavelength. Consequently, the designed distributed feedback chirped grating is suitable for use as a low-pass multi-wavelength selector. By increasing the number of periods in the graphene grating, the number of resonance modes can be significantly increased, thereby enabling a more densely packed multi-wavelength channel layout.

In Fig. 3a, a mutation can be observed near λ = 1.025 μm. As the chemical potential of graphene increases, the corresponding incident wavelength at which the mutation occurs exhibits a blue shift (towards shorter wavelengths). With an increase in the chemical potential of graphene, the transmission peaks become sharper and narrower; concurrently, the transmittance of the resonance peaks decreases, and the cutoff wavelength is reduced, which means the bandwidth narrows. This is because the increase in the chemical potential of graphene leads to an increased loss of electric field energy, thereby reducing the transmission peaks. Consequently, when this structure is employed as a low-pass multi-wavelength selector, the wavelengths corresponding to each transmission mode can be flexibly adjusted by varying the chemical potential of graphene. Figure 3b presents the reflectance curves corresponding to various incident wavelengths and chemical potentials of graphene. It can be observed that the bottom of each curve’s depression coincides with the peak position of the reflectance curve. This further indicates that the center of the transmission curve correlates with the transmittance.

(a) Dependence of the transmission spectra on the chemical potentials of graphene for some given wavelength of incident light. The wavelengths of incident light are set as λ = 32.4125 μm, 30.5875 μm and 29.4625 μm, respectively. (b) The local transmission spectrum. (c) Maxima of transmittance varying with the wavelength of incident light. The chirped grating spatial period number and is set as N = 20, the thickness difference between adjacent layers of B-type dielectric is Δd = 10 nm and the relaxation time is set as τ = 0.5 ps.

To investigate the regulatory impact of graphene chemical potential on parameters such as the transmission wavelength, transmittance, number of transmission modes, and cutoff wavelength of the wavelength selector, a specific area in Fig. 2a is selected for analysis, indicated by a pentagram. We selected three specific incident wavelengths λ = 32.4125 μm, 30.5875 μm, and 29.4625 μm for quantitative analysis. From Fig. 4a, it is evident that the transmittance varies with the chemical potential of graphene. At the input wavelength λ = 32.4125 μm, as the chemical potential of graphene increases, the transmittance of the resonance peak decreases, and the cutoff wave-length is reduced. When µ = 0.42 eV, the transmission curve is terminated. For λ = 30.5875 μm, the transmittance of the resonance peak initially decreases with the increase in the chemical potential of graphene, then increases, reaching a maximum at µ = 0.296 eV, and subsequently decreases. When µ = 0.49 eV, the transmission curve is terminated. At λ = 29.4625 μm, the transmittance of the resonance peak initially decreases gradually with the increase in the chemical potential of graphene, then increases, reaching a maximum at µ = 0.396 eV, and subsequently decreases. When µ = 0.54 eV, the transmission curve is terminated. It is evident that the magnitude of the chemical potential of graphene can modulate the transmittance and cutoff wavelength of the wavelength selector. In Fig. 4b, when the chemical potential of graphene is µ = 0.2 eV, 0.4 eV, and 0.6 eV, the incident wavelengths corresponding to the maximum transmittance are λ = 32.4125 μm, 30.5875 μm, and 29.4625 μm, respectively, with transmittances of 0.73, 0.55, and 0.37, respectively. For each increase of 1 eV in chemical potential, the wavelength will decrease by approximately 7.375 μm. For graphene with chemical potentials of 0.2 eV, 0.3 eV, and 0.4 eV, the corresponding full widths at half maximum (FWHM) were achieved as 0.7808 μm, 1.3964 μm, and 1.8318 μm, respectively. In Fig. 4c, when the incident wavelength λ ∈ [10 μm, 70 μm], the maximum number of transmission peaks is \(\:{T}_{m}=\:\)6, unaffected by the chemical potential of graphene, but the peak value of the transmission peak decreases with increasing incident wavelength.

(a,c). Re(σ) and Im(σ) varying with the incident wavelength for some given chemical potentials of graphene, respectively. (b,d) Re(σ) and Im(σ) changing with the chemical potential and incident wavelength, respectively. The chirped grating spatial period number is set as N = 20, the thickness difference between adjacent layers of B-type dielectric is Δd = 10 nm, and the relaxation time is set as τ = 0.5 ps.

To elucidate this phenomenon, we plotted the relationship between the surface conductivity of graphene and the chemical potential and incident wavelength, as depicted in Fig. 5. Figure 5a illustrates the relationship between the real part of the surface conductivity of graphene, Re(σ), and the chemical potential. It can be observed that for the three given values of µ = 0.2 eV, 0.3 eV, and 0.4 eV, there are three corresponding curves for Re(σ) as the incident wavelength varies. For a fixed chemical potential, near the parameter λ = 1.025 μm, Re(σ) undergoes a discontinuity, abruptly decreasing from a stable value close to zero. When λ > 1.025 μm, the real part of the surface conductivity of graphene increases with increasing incident wavelength. When the incident wavelength is fixed, Re(σ) increases with increasing chemical potential. Conductivity is proportional to the dielectric constant, which indicates the optical loss in graphene. Consequently, the larger Re(σ) is, the greater the corresponding optical loss in the system. As the incident wavelength increases, the loss also gradually increases, which corroborates the phenomenon observed in Fig. 2, where each transmittance decreases with increasing incident light wavelength.

Figure 5b illustrates the relationship between Re(σ) and the chemical potential and incident wave-length. It can be observed that the value of Re(σ) increases when the chemical potential of graphene is raised or when the incident wavelength is increased. As the wavelength and surface conductivity change, the left side of Re(σ) exhibits a waterfall-like appearance, while the right side resembles an up-hill slope. At the jump point for µ = 0.2 eV, the incident wavelength is λ = 3.4375 μm; at the jump point for µ = 0.4 eV, the wavelength is λ = 1.6625 μm; at the jump point for µ = 0.6 eV, the wavelength is λ = 1.3875 μm. This is due to the transition of electrons in graphene from intraband to interband transitions. As the chemical potential increases, the incident wavelengths at which the surface conductivity changes sharply exhibit a blue shift, this explains the phenomenon marked with a circle in Fig. 5a. On the one hand, the external voltage on graphene can modulate the chemical potential. On the other hand, the transmission phase of the wave in the graphene sheet array influences the light transmittance, which is a function of the surface conductivity. Consequently, the light transmittance can be flexibly modulated by the external voltage.

The imaginary part of the surface conductivity, Im(σ), corresponds to the real part of the refractive index of graphene. For three given chemical potential values, Fig. 5c illustrates how Im(σ) varies with the incident wavelength. At shorter incident wavelengths, each curve exhibits a depression that blue-shifts as µ increases, indicated by the circle. However, due to the ultra-thin nature of graphene, this distinct feature has a minimal impact on the transmittance. At larger incident wavelengths, Im(σ) increases with increasing incident wavelength. Similarly, for a fixed incident wavelength, Im(σ) increases with increasing chemical potential. The imaginary part of the surface conductivity, Im(σ), determines the real part of εg, which is a function of µ. Consequently, the bandwidth of the filter can be modulated by adjusting the structural parameters, as depicted in Fig. 4b.

(a) Influence of chirped grating spatial period on the transmission spectrum. (b) Number of transmission peaks changing for different chirped grating spatial periods. The chirped grating spatial period number is set as N = 20, the graphene chemical potential is µ = 0.2 eV, and the relaxation time is set as τ = 0.5 ps.

Figure 5d depicts the relationship between the imaginary part of the surface conductivity and the incident wavelength and chemical potential. At smaller incident wavelengths, a trough is observed on the far left of the Im(σ) schematic. This indicates that the incident wavelength at the valley of Im(σ) red-shifts (moves towards longer wavelengths) as the chemical potential decreases. The parameter Im(σ) determines the real part of the equivalent dielectric constant of graphene; hence, the transmittance of the filter can be modulated by adjusting the chemical potential.

Maintaining the number of spatial periods of the chirped grating N = 20 unchanged, the spatial period of the chirped grating is altered, for example, by taking \(\:{d}_{1}\) = 500 nm, \(\:{d}_{2}\) = 480 nm, …, \(\:{d}_{\text{N}}\) = 100 nm, with the thickness difference between adjacent layers of B-type dielectric becoming Δd = 20 nm, while other parameters remain unchanged. As demonstrated in Fig. 6a, the transmission spectra corresponding to different chirped grating spatial periods are shown. When light hits the array from the left, the incident wavelength is red-shifted with an increase in Δd.

The wavelength stability ratio S can be defined as the ratio of the original wavelength to the amount of wavelength change. As shown by the dashed box, when the change in Δd is 10 nm, the wavelength \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\) = 32.2125 μm, and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\) is selected as the reference wavelength. Then, the amount of wavelength change for each variation in Δd is approximately 10.39, 12.39, and 14.61, respectively. The stability ratio S gradually increases from 10.39 to 14.61, indicating that the sensitivity of wavelength variation to thickness decreases. When the thickness is greater, the wavelength shift caused by a unit change in thickness is smaller, and the system tends to be more stable.

Figure 6b illustrates the relationship between the number of transmission peaks and the spatial period Δd of the chirped grating. It can be observed that as the spatial period Δd increases, the number of resonance peaks increases, that is, the wavelengths satisfying the resonance condition are increased; the bandwidth also increases. Consequently, the number of transmission modes can be modulated by adjusting the value of Δd.

(a) Transmission spectra versus different relaxation time τ. (b,c) Imaginary part and Real part of graphene surface conductivity varying with the incident wavelength for some given τ, respectively. The chirped grating spatial period number is set as N = 20, and the graphene chemical potential is µ = 0.2 eV.

As described in Eq. (1), the surface conductivity of graphene is a function of the parameter τ, which is defined as the phenomenological relaxation time of electrons in graphene. Figure 7a presents the transmission spectra for different values of τ. It can be observed that when τ changes, the positions of all band gaps in the spectrum remain un-changed. However, the photonic passbands in the transmission spectrum increase in width with the increase of τ, because the optical loss of graphene decreases with the increase of τ. The relaxation time affects only the surface conductivity of graphene and does not influence the geometric parameters of the distributed feedback chirped grating structure composed of the graphene array. Consequently, the positions of the band gaps in the transmission spectrum are unaffected by τ.

The imaginary part of the surface conductivity, Im(σ), is unaffected by relaxation time, as depicted in Fig. 7b. For different values of τ, Im(σ) increases with increasing incident wavelength, but when τ is 0.3 ps, 0.4 ps, and 0.5 ps, the three surface conductivity curves are nearly identical. Im(σ) controls the actual equivalent permittivity of graphene; hence it is not possible to modulate the stopband in the transmission spectrum by adjusting τ.

As illustrated in Fig. 7c, the real surface conductivity, Re(σ), is shown for varying values of τ. For three specific values of τ = 0.3, 0.4 and 0.5 ps, Re(σ) in each respective curve is delineated as previously described. The real part, Re(σ), is a determining factor in the optical loss in graphene. It is evident from the figure that Re(σ) increases with increasing incident wavelength for a given value of τ, and conversely, the transmittance decreases with decreasing incident wavelength, as shown in Fig. 7a. Furthermore, when the incident wavelength is fixed, the smaller the value of τ, the larger the Re(σ) is, implying greater optical loss.

Figure 8 shows the transmission spectra at different temperatures. As the temperature increases, the bandgap positions and transmission characteristics, including bandwidth and peak intensity, remain stable.

This study proposes a resonator structure based on two symmetrically distributed chirped graphene gratings. The structure achieves distributed feedback through aperiodic spatial periods, thereby overcoming the bandwidth limitations of traditional uniform-period gratings. The chirped gratings’ gradient periods allow multiple resonance conditions to be met simultaneously, with the spacing between transmission peaks increasing with wavelength, thereby supporting dense multi-wavelength channel layouts. By combining the multidimensional modulation of chirped grating periods, cavity length, and chemical potential, independent optimization of wavelength and bandwidth is achieved. Table 1 shows the comparative advantages over existing wavelength selectors. In contrast, traditional uniform-period graphene gratings typically support only single or a few wavelength channels31,32,33. Specifically, for every 1 eV change in chemical potential, the wavelength shifts by approximately 7.375 μm, without the need for any physical structural changes. Moreover, by adjusting the chemical potential of graphene within the range of 0.2 to 0.4 eV, we can expand the FWHM from 0.78 μm to 1.83 μm to meet different spectral resolution requirements. When the chirped period number N is 60, the mode density increases by approximately 2 times. The transmission characteristics remain stable with temperature changes, outperforming the environmental dependence of traditional chirped fiber gratings11,14. By changing the chemical potential of graphene, the transmission wavelength and bandwidth can be dynamically adjusted. Although this electro-tuning characteristic also exists in existing graphene gratings17,34,35, the chirped gradient design adopted in this study further enhances the tuning range and precision. By optimizing the chirped period number and chemical potential, resonance enhancement and loss can be balanced, and its comprehensive performance is superior31,32,33,34,35.

In the fabrication process, we will employ chemical vapor deposition (CVD) to fabricate dielectric layers of varying thicknesses. CVD is a well-established and extensively employed technique in micro- and nanofabrication, enabling precise control of the thickness and uniformity of dielectric layers36. These layers are meticulously designed in accordance with the chirped grating’s arrangement principles to achieve the required optical characteristics. Furthermore, pre-fabricated monolayer graphene, a commercially available product, can be transferred onto the surface of the gold grating superstructure37. Employing this transfer technique, alternating stacks of monolayer graphene and dielectric layers can be assembled to construct the proposed chirped grating structure. Additionally, graphene can be directly deposited onto the surface of dielectric layers using CVD38. By integrating CVD and graphene transfer methodologies, the proposed structure becomes highly feasible for laboratory implementation. Otherwise, in practice, the following steps can be adopted: First, the sample is mounted on a transparent substrate, ensuring that its surface is flat and free of contamination. The operation is performed in a dry environment to avoid water vapor adsorption. Second, the light source, sample, and detector are aligned to ensure that the incident light is perpendicular to the sample surface. An infrared laser pointer is used to assist in the alignment of the optical path. Then, the background spectrum (the light intensity distribution \(\:{I}_{0}\left(\lambda\:\right)\) without the sample) is calibrated. Finally, the spectrum is scanned in bands (0–30 μm using FTIR, and 30–80 μm using a terahertz time-domain spectroscopy system), with a focus on the long-wavelength cutoff characteristics (such as the sharp drop in transmittance in the 20–80 μm region). The transmittance is calculated using \(\:T=I\left(\lambda\:\right)/{I}_{0}\left(\lambda\:\right)\). The measured spectral data are normalized with respect to the baseline signal to identify the cutoff characteristics and transmission peaks of the grating, and a transmission spectrum plot is then drawn. Although our research is primarily theoretical, we have proposed several experimental approaches. However, significant challenges persist in manufacturing and practical application. Achieving large-area uniformity and high precision remains challenging39,40. Environmental factors (such as humidity and oxidation) affect its structural stability41.

Conclusions

In summary, we have examined the optical response of a complex system composed of dielectrics and graphene arrays in the communication band. The graphene sheets are arranged in a non-periodic manner within the substrate material to form chirped gratings, with two chirped gratings positioned at the ends of the defect layer and symmetric about the center of the defect layer. A series of resonance peaks emerge in the transmission spectrum, and their bandwidth, transmittance, and cutoff wavelength can be controlled by adjusting the chemical potential of graphene, the spatial period of the chirped gratings, and the number of spatial periods. The number of resonance peaks is directly proportional to the spatial period of the chirped gratings. This study offers a viable solution for the design of optical low-pass multi-wavelength selectors and filters.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Change history

30 October 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the Funding section, the grant number for the Hubei Provincial Department of Education Scientific Research Plan Directed Project was incorrectly given as ‘B2024150’. The correct grant number is ‘B2024156’.

References

Moczała-Dusanowska, M. et al. Strain-tunable single-photon source based on a circular Bragg grating cavity with embedded quantum Dots. ACS Photon. 7, 3474–3480 (2020).

Resen, D. A. & Altemimi, M. F. Terahertz frequency generation using fiber Bragg gratings: a cost-effective and simplified approach. J. Opt. 53, 2020–2026 (2023).

Abeywardena, C. et al. Highly sensitive optical fiber Bragg grating contact pressure sensor embedded in a polymer layer: modelling and experimental validation. Results Opt. 14, 100604 (2024).

Lin, J. et al. Fiber Bragg grating sensing system for temperature measurements based on optically injected DFB-LD with an OEO loop. Opt. Express. 32, 19388–19396 (2024).

Liang, X. et al. Spectral-distortionless, flat-top, drop filter based on complementarily-misaligned multimode-waveguide Bragg gratings. J. Lightwave Technol. 38, 6600–6604 (2020).

Miller, G. A., Askins, C. G., Cranch, G. A. & Friebele, E. J. Early index growth in germanosilicate fiber upon exposure to continuous-wave ultraviolet light. J. Lightwave Technol. 25, 1034–1044 (2007).

Xiang, Y. T., Peng, H. M., Wan, B. F. & Zhang, H. F. A novel comb-like nonreciprocal evanescent wave filter based on the 1-D ternary magnetized plasma photonic crystals. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 49, 1826–1833 (2021).

Singh, B. K. et al. Photonic band gap consequences in one-dimensional exponential graded index photonic crystals. Optik 240, 166854 (2021).

Jiang, Y. et al. A selectable multiband bandpass microwave photonic filter. IEEE Photon J. 5, 5500509 (2013).

Ren, H., Jiang, C., Hu, W., Gao, M. & Wang, J. Photonic crystal channel drop filter with a wavelength-selective reflection micro-cavity. Opt. Express. 14, 2446–2458 (2006).

Sun, J. et al. All-polarization maintaining mode-locked Yb-doped fiber laser with chirped fiber Bragg grating. APS 47, 114001 (2018).

Ma, Y. et al. High-power tapered two-section distributed feedback laser based on a chirped sampled grating. Appl. Opt. 62, 2661–2668 (2023).

Cao, X. et al. All-fiber low-noise 1.06µm optical frequency comb generated by a figure-9 laser with chirped fiber Bragg grating. Opt. Fiber Technol. 86, 103853 (2024).

Liu, C., Qiu, S. & Wang, J. Simultaneous distributed acoustic and temperature sensing system based on ultra-weak chirped fiber Bragg grating array. Opt. Express. 31, 18516–18524 (2023).

Nagpal, A., Zhou, M., Ilic, O., Yu, Z. & Atwater, H. A. Thermal metasurface with tunable narrowband absorption from a hybrid graphene/silicon photonic crystal resonance. Opt. Express. 31, 11227–11238 (2023).

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191 (2007).

Zhao, D., Wang, L., Liu, F., Zhong, D. & Wu, M. Photonic stopband filters based on graphene-pair arrays. Appl. Sci. 11, 11557 (2021).

George, J. K. & Sorger, V. J. Graphene-based solitons for spatial division multiplexed switching. Opt. Lett. 42, 787–790 (2017).

Wang, Z., Wang, B., Hua, L., Kai, W. & Lu, P. Surface vector plasmonic lattice solitons in semi-infinite graphene-pair arrays. Opt. Express. 25, 20708–20717 (2017).

Qin, C. et al. Low-loss plasmonic supermodes in graphene multilayers. Opt. Express. 22, 25324–25332 (2024).

Wang, F. et al. Asymmetric plasmonic supermodes in nonlinear graphene multilayers. Opt. Express. 25, 1234–1241 (2017).

Zhao, X. et al. Tunable optical bistability, tristability and multistability in arrays of graphene. Appl. Sci. 10, 5766 (2020).

Romanets, P. N. & Vasko, F. T. Rabi oscillations under ultrafast excitation of graphene. Phys. Rev. B. 81, 241411 (2010).

Wang, F. et al. Rabi oscillations of plasmonic supermodes in graphene multilayer arrays. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 23, 125–129 (2017).

You, S., An, J. & Qiao, Z. Spin resolved zero-line modes in minimally twisted bilayer graphene from exchange field and gate voltage. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 077301 (2024).

Lamayny, K. et al. Surface states in one-dimensional graphene-dielectric photonic crystal. Interactions. 245, 356 (2024).

Fernandes, J. et al. Graphene-embedded planar and cylindrical Oldenburger–Kolakoski aperiodic photonic crystals. Opt. Mater. 148, 114832 (2024).

Gronkiewicz, K. et al. Expanding the range of graphene energy transfer with multilayer graphene. Nanoscale. 16, 13464–13470 (2024).

Ni, H. et al. Goos-Hänchen shifts around Fano resonances in superconducting photonic crystals embedded with graphene. Opt. Laser Technol. 182, 112186 (2024).

Wen, C., Liu, W. & Wu, J. Tunable Terahertz optical bistability and multistability in photonic metamaterial multilayers containing nonlinear dielectric slab and graphene sheet. Appl. Phys. A. 126, 426 (2020).

Guo, C., Wang, D. & Mu, C. Progress on optical fiber sensors based on graphene/graphene oxide. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 57, 150003 (2020).

Hill, K. O. & Meltz, G. Fiber Bragg grating technology: fundamentals and overview. J. Lightwave Technol. 15, 1263–1276 (1997).

Tao, Y. et al. Numerical investigation of the linearity of graphene-based silicon waveguide modulator. Opt. Express. 27, 9013–9031 (2019).

Ma, Y. et al. All optical control of long period fiber grating based on graphene oxide. High. Power Laser Part. Beams. 32, 011015 (2020).

Xing, P., Ooi, K. J. A. & Tan, D. T. H. Ultra-broadband and compact graphene-on-silicon integrated waveguide mode filters. Sci. Rep. 8, 9874 (2018).

Mao, D., Tan, M. & Chen, L. Applications of dielectric thin film by electron cyclotron resonance plasma chemical vapor deposition for semiconductor photoelectronic devices. Proc. SPIE. 3547, 315–321 (1998).

Liu, J. et al. Near-field characterization of graphene plasmons by photo-induced force microscopy. Laser Photon. Rev. 12, 1800040 (2018).

Ismach, A. et al. Direct chemical vapor deposition of graphene on dielectric surfaces. Nano Lett. 10, 1542–1548 (2010).

Guo, S. et al. Enhanced infrared photoresponse induced by symmetry breaking in a hybrid structure of graphene and plasmonic nanocavities. Carbon 170, 49–58 (2020).

Peng, W. Y., Yan, S. Q. & Tang, M. Graphene/silicon heterogeneous integrated optoelectronic devices. Semicond. Optoelectron. 43, 1020–1028 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Mid infrared er3+∶ ZBLAN mode-locked laser and wavelength tunable performance based on graphene/ws2 saturated absorber. Chin. J. Lumin. 45, 1354–1363 (2024).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (12274157); Hubei Higher Education Association Project (2023XD110); the Hubei Provincial Department of Education Scientific Research Plan Directed Project (B2024156); the Scientific Research Project of Hubei University of Science and Technology (2024-25 × 06).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L., D.Z., J.D., M.Z., D.Z., H.N., F.L.: Conceptualization, article drafting, methodology; software development. X.C.: Result analysis, article proofreading.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, A., Zhao, D., Dong, J. et al. Optical multi-wavelength selectors based on distributed feedback chirped grating in arrays of graphene. Sci Rep 15, 29258 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15395-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15395-w