Abstract

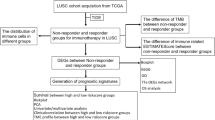

G-protein coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1) is involved in estrogen response and associated with tumorigenesis in several solid tumors, and we previously reported that its positive expression rate is more than 80% in lung cancer. However, GPER1 has been less studied during the tumorigenesis in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We used Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma (LUSC) data from the Cancer Genome Atlas and Gene Expression Omnibus databases, and self-sequencing data of whole transcriptome of A549 cells for research. Firstly, the expression of GPER1 in adjacent tissues and cancer tissues was compared. Then, according to the median of GPER1, LUAD and LUSC samples in the data set were assigned into GPER1 high and low expression group, respectively. The hub genes were enriched and analyzed. Additionally, the association between GPER1 expression and immune related responses were explored. We obtained GPER1-inhibited and -activated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from the self-sequencing data. Finally, the GPER1-related competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network was constructed and verified by experiments. The expression of GPER1 in cancer tissues was decreased when compared with that in healthy tissues. The GPER1 gene has good diagnostic value as a differentiator between cancer and normal samples in LUAD- and LUSC-related datasets. Fourteen and thirteen hub genes were identified in LUAD and LUSC, respectively. They were all enriched in the pathways of actin cytoskeleton regulation, extracellular matrix assembly, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. In addition, GPER1 was significantly associated with immune cells infiltration and expression of common immune checkpoints, and its low expression could predict benefit from immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) treatment in LUSC. The whole-transcriptome sequencing data of A549 cells were analyzed to obtain 132 GPER1 repression- and 39 GPER1 activation-related mRNA, and 13 hub genes were finally screened. Further, the GPER1-related transcription factor (TF)-miRNA–mRNA network and lncRNA/circRNA–miRNA–mRNA ceRNA networks were constructed. Finally, confirmatory studies demonstrated that the hub genes and MAPK signaling pathway were regulated by GPER1, and knockdown of GPER1 expression caused F-actin cytoskeleton rearrangement and promoted cell migration in A549 cells. The expression of GPER1 was decreased during the tumorigenesis in NSCLC. GPER1 was significantly associated with immune cells infiltration and immune checkpoints expression in both LUAD and LUSC, and its low expression could predict benefit from ICB treatment in LUSC. In addition, we report a ceRNA network that may provide new insight into the roles of GPER1 in NSCLC development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer is prevalent and has the highest cancer-related mortality worldwide1. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type and accounts for about 85% of this disease. It is increasingly accepted that NSCLC exhibits notably sexual dimorphism2 based on the following facts: an increasing incidence of NSCLC among young women than men was observed3, the driver mutations such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) alterations occur more frequently in females4, the expression level of programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) is higher in males5 and correspondingly, male patients can benefit more from anti-PD1/PD-L1 immunotherapy6,7. Thus, it is very urgent to identify the reasons underlying the sexual dimorphism of NSCLC to develop strategies preventing and curing this disease.

In the last 20 years, a large number of studies had been done to investigated whether estrogens or their cognate estrogen receptor (ER)-α and -β play roles during the pathogenesis and development of this disease; however, little progress has been made8. The G protein-coupled estrogen receptor1 (GPER1), formerly named GPR30, is the third and novel type of ER, which is different from ER-α and -β, due to its ability that yields a rapid non-genomic signaling upon binding with estrogen9. In the past two decades, GPER1 was found to play a broad range of biological roles under many physiological and pathological contexts, including regulation of metabolism10, inflammatory or immune response11; additionally, it was involved in the tumorigenesis and progression of several tumors, ranging from estrogen-related cancers such as breast12 and ovarian cancers13 to estrogen-unrelated cancers such as thyroid14, prostate15, liver16 and gastric cancers17. We and others had previously demonstrated that positive expression rate of GPER1 was more than 80% in NSCLC18,19; furthermore, our work showed that its subcellular localization was associated with EGFR mutation status, resistance to EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI) and patients’ outcomes18,20. However, the expression changes and roles of GPER1 during tumorigenesis of NSCLC remain unclear.

In this study, by using bioinformatic and self-sequencing data, we first performed a pan-cancer analysis to compare the expression levels of GPER1 between cancer and healthy tissue, and to analyze the correlation of GPER1 expression with patient prognosis. Furthermore, we conducted a comprehensive analysis regarding GPER1 functions in NSCLC, with a focus on the modulating tumor immune microenvironment (TIME). We found the expression of GPER1 was reduced in the tumorigenesis in most of the solid tumors, and it was broadly involved in TIME modulation and extracellular matrix (ECM) assembly in NSCLC. Indeed, our analysis provides new insights regarding GPER1 in tumorigenesis and cancer progression, therefore presenting a theoretical basis for subsequent studies aimed to developing new therapeutic targets and biomarkers for NSCLC.

Methods

Data collection

The expression data of 34 and 31 cancers such as LUAD, LUSC, GBM and OV were downloaded from TIMER database and GEPIA database, respectively. In addition, RNA-seq data for 21 cancers including LUAD, LUSC, ESCA, and BRCA were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) database. The TCGA-LUAD dataset included 526 LUAD samples and 59 normal samples. In addition, this study also downloaded LUAD-related expression data from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) database; 46 LUAD samples and 45 control samples were included in the GSE18842 dataset, and the sequencing data of 58 LUAD tumor samples and non-tumor samples were included in the GSE32863 dataset. The TCGA-LUSC dataset included 501 LUSC samples and 49 normal samples. Similarly, this study also downloaded LUSC-related expression data from the GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query) database; 48 LUSC samples and 30 control samples were included in the GSE2088 dataset, and 16 LUSC samples and 15 control samples were included in the GSE31446. Furthermore, mRNA sequencing was performed on cells in four subgroups. The four subgroups were human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells (A), A549 cells with activated GPER1 (A549 + G1, AG), A549 cells with knocked down GPER1 (Aal cells, AA), and Aal cells with GPER1 agonist added (Aal + G1, AAG), with three samples in each group.

Analysis of GPER1 in Pan-cancer

GPER1 plays an important role in cancer. First, this study verified the expression of GPER1 in 34 different cancers and 31 different cancers such as LUAD, GBM, OV and normal tissues in TIMER database and GEPIA database, respectively. In addition, cancers were classified into high and low expression groups based on the median GPER1 expression in the 21 cancers of TCGA datasets, and survival differences between high and low expression groups were compared. To determine whether GPER1 expression was associated with patient outcomes, cox regression analysis was further performed for 21 cancers.

Analysis of GPER1 in LUAD and LUSC

To analyze the role played by GPER1 in LUAD and LUSC, respectively, we compared the expression of GPER1 in cancer tissues with that in paracancer samples using log-rank sum test in TCGA database, GES32863, GSE18842, GSE2088 and GSE31446 datasets, and assessed the diagnostic ability of GPER1 plotting receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Identification of hub genes

In the TCGA dataset, LUAD and LUSC patients were divided into GPER1 high and low expression groups, respectively, based on the median value of GPER1, and then differential analysis was performed for GPER1 high and low expression groups using the “limma” package21. The screening conditions for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were P < 0.05, |log2FC| >0.5. To investigate the interactions between DEGs, we used the STRING (https://string-db.org) website to construct a protein-protein interactions (PPI) network based on DEGs. After that, we analyzed the DEGs in the PPI network by Degree, MCC, and MNC through cytoHubba plugin in Cytoscape, and selected the top 20 concurrent genes of the three algorithms as hub genes.

Functional enrichment analysis

This study performed Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)22,23,24 and gene ontology (GO) enrichment analyses of hub genes using the “clusterProfiler” package25, and the enriched pathways were screened by P < 0.05. In order to analyze the effect of high and low expression groups on disease progression, this study also used the “clusterProfiler” package25 to perform enrichment analysis of high and low expression groups. First, the “limma” package21was used to analyze the differences between the high and low expression groups, and then the sorted gene sets were sorted according to FC in descending order and entered into “clusterProfiler” for enrichment analysis with a screening condition of P < 0.05.

Immune infiltration analysis

The activity of immune cells in each sample could be obtained by the Cell type Identification by Estimating Relative Subsets Of RNA Transcripts (CIBERSORT) algorithm. In this study, we calculated the proportion of immune cells by the CIBERSORT algorithm and compared immune cells between high and low expression groups by rank sum test. After that, we also calculated the relationship between differential immune cells between high and low expression groups and GPER1 using Pearson correlation analysis.

Cell culture and whole transcriptome sequencing

Human LUAD cell line A549 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C with 5% CO2, as described previously20. GPER agonist G1 was purchased from Tocris (Ellisville, USA), and GPER1 knockdown or overexpression and activation with G1 were done as described previously20. Whole transcriptome sequencing assay was conducted by an external service provider (LC Sciences, Houston, TX).

Identification and enrichment analysis of GPER1 repression-related genes of sequencing data

Firstly, Trimmomatic software was used to filter the low-quality data from the original data to remove contamination and splice sequences, and finally clean data was obtained. Then the quality of sequencing data was evaluated by FastQC26 (v0.11.9) software, and the Clean Data was compared with the reference genome (GRCh37). The comparison tool was hisat2 (v2.2.1). After obtaining the gene expression matrix for each sample, we used the “DESeq2” package26 to perform differential analysis between AA and control A. KEGG and GO enrichment analysis of DEGs were performed using the “clusterProfiler” package25 to filter the enriched pathways. Then we also performed differential analysis between AAG and AA and enrichment analysis for DEGs. The screening conditions for DEGs were P < 0.05 and |Log2FC|>1.The enriched pathways were screened with P < 0.05. Next, genes with opposite expression trends between DEGs in the AA and A groups and DEGs in the AAG and AA groups were crossed as GPER1 repression-related genes. And the “clusterProfiler” package25 was used to perform KEGG and GO enrichment analysis of GPER1 repression-related genes.

Identification of GPER1 activation-related genes

Differential analysis was performed between AG and A and between AAG and AG groups using the “DESeq2” package26 with the screening conditions of P < 0.05 and |Log2FC|>1. KEGG and GO enrichment analysis was performed on DEGs using the “clusterProfiler” package25. Next, DEGs with opposite expression trends between AG and A and between AAG and AG groups were crossed to obtain GPER1 activation-associated genes, and KEGG and GO enrichment analysis of GPER1 activation-associated genes were performed using the “clusterProfiler” package25.

Screening of GPER1 activation and repression-related hub genes

We used STRING (https://string-db.org) website to construct PPI networks for GPER1 activation and repression-related genes with a confidence level of 0.2 to help us identify the nodes that play key roles in the network. Then we analyzed the genes in the PPI network by using the cytoHubba plugin in Cytoscape for Degree, MCC, and MNC, respectively, taking the top 20 genes for each algorithm and selecting the genes that were present in all three metrics as hub genes for subsequent analysis.

Construction of upstream and downstream regulatory networks of hub genes

We used the “DESeq2” package26 to screen for differential miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs between AA and A at P < 0.05 and |Log2FC|>1. Similarly, we also screened for differential miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs between the AG and A groups. After that, the Hub gene was entered into the Starbase database for mRNA–miRNA regulatory relationship analysis to obtain the miRNAs that interacted with the Hub gene, and the predicted miRNAs were intersected with all the differential miRNAs between AA and A and between AG and A to obtain the intersecting miRNAs. Meanwhile, we input the hub gene into the network analyst online database for mRNA-TF interaction prediction, preserving the TF-mRNA–miRNA triplet regulatory interaction. In this way, we obtained a TF-mRNA–miRNA regulatory network. Next, the obtained intersecting miRNAs were entered into Starbase database to obtain miRNA–circRNA correlation and miRNA–lncRNA correlation, and again only all the differential lncRNAs and differential circRNAs obtained between AA and A, between AG and A, and the predicted lncRNAs and circRNAs were retained. Thus, we obtained an mRNA–miRNA–lncRNA regulatory network and an mRNA–miRNA–circRNA regulatory network.

Real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) experiment

TRlzol was used to extract RNA from the cells of A549 group, Aal group, Aal + G1 group and A549 + G1 group, respectively. The concentration of RNA was detected by NanoPhotometer N50. The mRNA was reverse transcribed using the SureScript-First-strand-cDNA-synthesis-kit kit from Saville, and then the reverse transcription product cDNA was subjected to qPCR reaction. GAPDH was the internal reference gene, and the primer sequences were shown in Table 1. Finally, the expression of hub gene in the four groups of cells was compared using F-test.

Western blot analysis

For this experiment, cells were treated using G1 at the concentrations of 0.1 µM for various times indicated in the figure legend. The Protein cell lysates and Western blotting procedures were performed as described previously20. Cellular proteins were firstly separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then, transferred to PVDF membranes by half wet transfer on the ice. The monoclonal rabbit antibody against ERK1/2 (ab184699) and ERK1/2 (pT202/T185) (ab201015) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK), and these specific primary antibodies were incubated with the membranes at 4 °C overnight, then the corresponding secondary antibody conjugated with HRP were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes incubated by ECL luminescent solution were then imaged through chemiluminescent HRP substrate. Images were analyzed using Image J software. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with representative gels shown.

F-actin cytoskeleton observation

Cells were grown on glass coverslips for 48 h, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.1% triton X-100 and blocked with 5% goat serum. Cells were then incubated with TRITC-conjugated phalloidin to label filamentous actin (F-actin). Coverslips were mounted on glass slides and subsequently imaged using a Nikon Eclipse 80i epifluorescence microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Transwell migration assay

Cells (5 × 104 in 100 µl) were seeded into the upper well of a transwell chamber, which contained 500 µl of medium in the lower well. Chambers were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Rho kinase inhibitor Y27632 (0.1 µM) was used in the experiments.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS System 17.0 was used for the statistical analysis of data sets. Student’s t-test or ANOVA were used to evaluate difference between subgroups. Two-tailed p-values of 0.05 or less were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The expression of GPER1 was significantly lower in most tumor tissues than in non-cancerous tissues

In the TIMER database, GPER1 expression was lower than normal tissue in 13 cancers, including BLCA, BRCA, CHOL, COAD, ESCA, KICH, LUAD, LUSC, PRAD, READ, STAD, THCA, and UCEC (Fig. 1A). Likewise, in the GEPIA database, GPER1 expression was lower in 13 cancers than their normal tissues, including ACC, BLCA, BRCA, CESC, CHOL, COAD, KICH, LUAD, LUSC, READ, STAD, UCEC and UCS (Fig. 1B). Overall, the expression of GPER1 was significantly lower in most tumor tissues than in non-cancerous tissues. Importantly, GPER1 was a protective factor in ESCA, KIRC and UCEC; however, there was only a marginally protective effect in BRCA and LUAD (Fig. 1C).

GPER1 had good diagnostic value as distinguishing cancer from normal samples

The expression of GPER1 in cancer tissues was significantly lower than that in normal tissues in the TCGA, GSE32863, and GSE18842 datasets of LUAD (Fig. 2A) as well as in TCGA, GSE2088, and GSE31446 datasets of LUSC (Fig. 2B). In addition, the area under the curve (AUC) values of GPER1 gene in these datasets were 0.92, 0.948, and 0.955 in LUAD (Fig. 2C) as well as 0.946, 0.912 and 0.792 in LUSC (Fig. 2D), respectively, indicating that this gene had good diagnostic value as distinguishing cancer from normal samples.

The expression and diagnosis of GPER1 in LUAD and LUSC. (A) The expression of GPER1 in LUAD tissues and normal tissues in TCGA, GES32863 and GSE18842 datasets. (B) The expression of GPER1 in LUSC tissues and normal tissues in TCGA, GSE2088 and GSE31446 datasets. (C) The ROC curve of GPER1 in TCGA, GES32863, and GSE18842 datasets, evaluating the diagnostic value of GPER1 in distinguishing LUAD samples from normal samples. (D) The ROC curve of GPER1 in TCGA, GSE2088 and GSE31446 datasets, evaluating the diagnostic value of GPER1 in distinguishing LUSC samples from normal samples.

The 14 and 13 hub genes were identified in LUAD and LUSC, respectively

In LUAD, the median value of GPER1 (0.736) divided TCGA-LUAD into 263 GPER1 high expression samples and 263 GPER1 low expression groups. There were 198 DEGs in high expression patients compared to low expression patients, with 142 upregulated genes and 56 downregulated genes (Fig. 3A). The heat map of the top 20 DEGs was shown in Fig. 3B. The confidence level in the PPI network was chosen to be 0.4, and the network contained 154 nodes and 466 edges (Fig. 3C), in which CAV1 and ITGAM were connected with most genes and they were key genes in the PPI network. 14 common mRNAs, which were hub genes, were analyzed in Degree, MCC, and MNC, namely ITGA2, ITGB4, VWF, ITGA3, ITGB6, ICAM1, FGA, A2M, ITGAM, PLAU, CAV1, PLAT, SERPINA1, KIT (Fig. 3D).

Identification of hub genes in LUAD and LUSC. (A) Volcano map of DEGs between GPER1 high expression group and GPER1 low expression group in LUAD. (B) The heat map of the top 20 DEGs between GPER1 high expression group and GPER1 low expression group in LUAD. (C) The PPI network of DEGs between GPER1 high expression group and GPER1 low expression group in LUAD. (D) The Venn diagram of 14 hub genes between GPER1 high expression group and GPER1 low expression group in LUAD. (E) Volcano map of DEGs between GPER1 high expression groups and GPER1 low expression groups in LUSC. (F) The heat map of the top 20 DEGs between GPER1 high expression group and GPER1 low expression group in LUSC. (G) The PPI network of DEGs between GPER1 high expression group and GPER1 low expression group in LUSC. (H) The Venn diagram of 13 hub genes between GPER1 high expression group and GPER1 low expression group in LUSC.

In LUSC, the median value of GPER1 (0.597) divided TCGA-LUSC into 250 GPER1 high expression samples and 251 GPER1 low expression groups. There were 432 DEGs in high expression patients compared to low expression patients, with 337 upregulated genes and 95 downregulated genes (Fig. 3E). The heat map of the top 20 DEGs was shown in Fig. 3F. The confidence level in the PPI network was chosen to be 0.7, and the network contained 225 nodes and 734 edges (Fig. 3G). 13 common mRNAs, which were hub genes, were analyzed in Degree, MCC, and MNC, namely COL1A1, COL1A2, COL3A1, COL5A1, COL5A2, MMP2, SPARC, BMP1, FN1, BGN, DCN, FBN1, ITGA3 (Fig. 3H).

The main enrichment pathways of GPER1 in LUAD and LUSC were similar

In LUAD, functional enrichment analysis of the Hub genes revealed that 14 hub genes were enriched for a total of 633 GO functions and 25 KEGG pathways. GO functions included wound healing, integrin binding, coagulation, cell-matrix adhesion, focal adhesion, integrin complex, collagen-containing extracellular matrix, regulation of fluid levels, protease binding, plasma membrane signaling receptor complex, and response to hypoxia (Fig. 4A). Figure 4B showed 25 KEGG pathways, such as complement and coagulation cascades, extracellular matrix (ECM)-receptor interactions, focal adhesion, regulation of actin cytoskeleton, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, hematopoietic cell lineage, human papillomavirus infection, platelet activation, etc. Importantly, GSVA functional enrichment analysis showed that the GPER1 high expression group was enriched to immune response, T cell response, angiogenesis and other pathways (Fig. 4C).

Enrichment analyses of hub genes in LUAD and LUSC. (A) GO enrichment map of hub genes in LUAD. (B) KEGG enrichment map of hub genes in LUAD. (C) GSVA functional enrichment analysis between GPER1 high expression group and GPER1 low expression group in LUAD. (D) GO enrichment map of hub genes in LUSC. (E) KEGG enrichment map of hub genes in LUSC. (F) GSVA functional enrichment analysis between GPER1 high expression group and GPER1 low expression group in LUSC.

In LUSC, functional enrichment analysis of the hub genes revealed that 13 hub genes were enriched for a total of 287 GO functions and 15 KEGG pathways. GO functions included collagen-containing ECM, ECM structural constituent, collagen fibril organization, platelet-derived growth factor binding, etc. (Fig. 4D). Figure 4E showed 15 KEGG pathways, such as AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, protein digestion and absorption, proteoglycans in cancer, ECM-receptor interactions, relaxin signaling pathway, amoebiasis, focal adhesion, diabetic cardiomyopathy, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, human papillomavirus infection, regulation of actin cytoskeleton, etc. In addition, GSVA functional enrichment analysis showed that the GPER1 high expression group was enriched to immune response, T cell response and other pathways (Fig. 4F), which was similar to that in LUAD.

Together, these results suggest that GPER1 signaling participated in cell-matrix adhesion, ECM assembly, regulation of actin cytoskeleton and immune response in NSCLC.

Immune infiltration analysis of LUAD and LUSC

Next, we performed immune infiltration analysis in view of GPER1 high expression being associated with immune response as showed by GSVA functional enrichment analysis. In LUAD, the proportions of 22 types of immune cells in the low and high GPER1 expression groups were shown in Fig. 5A, in which five immune cell scores, namely Plasma cells, gamma delta T cells, Monocytes, M1 Macrophages, and resting Mast cells, differed between the low and high GPER1 expression groups (Fig. 5B). Plasma cells, M1 Macrophages and gamma delta T cells were more concentrated in the low expression group, while Monocytes and resting Mast cells were more concentrated in the high expression group (Fig. 5C). In addition, GPER1 was positively correlated with resting Mast cells and Monocytes, while negatively with Plasma cells, gamma delta T cells and M1 Macrophages (Fig. 5D,E).

Immune infiltration analysis in LUAD and LUSC. (A) Column stacking diagram of immune cell abundance in high and low GRER1 expression groups in LUAD. (B) The expression of immune cells in the high and low GRER1 expression groups in LUAD. (C) Box plot reveals the expression of differential immune cells in high and low GRER1 expression groups in LUAD. (D,E) Correlation analysis between differential immune cells and GPER1 in LUAD. (F) Column stacking diagram of immune cell abundance in GRER1 high and low expression groups in LUSC. (G) The expression of immune cells in the high and low GRER1 expression groups in LUSC. (H) Box plot reveals the expression of differential immune cells in high and low GRER1 expression groups in LUSC. (I) Correlation analysis between differential immune cells and LUSC.

In LUSC, the proportions of 22 types of immune cells in the low and high GPER1 expression groups were shown in Fig. 5F, in which eight immune cell scores, namely naive B cells, memory B cells, memory CD8 T cells, resting memory CD4 T cells, activated memory CD4 T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), etc., differed between the low and high GPER1 expression groups (Fig. 5G). The naive B cells, gamma delta T cells, CD8 T cells and activated memory CD4 T cells were more abundant in the low expression group, while memory B cells, M0 Macrophages, resting memory CD4 T cells and Tregs were more concentrated in the high expression group (Fig. 5H). In addition, GPER1 was positively correlated with memory B cells, M0 Macrophages and Tregs, while negatively with naive B cells, gamma delta T cells, CD8 T cells and activated memory CD4 T cells (Fig. 5I).

GRER1 had strong correlation with common immune checkpoints in LUAD and LUSC

Next, the expression levels of 9 immune check point genes were compared between low and high GPER1 expression groups in LUAD and LUSC, respectively, including CD27, CD274, CD80, CTLA4, IDO1, LAG3, PDCD1, PDCD1LG2 and TIGIT. Strikingly, in LUAD, GPER1 expression is consistently positively correlated with CD274 (PD-L1), CD80, CTLA4, PDCD1, PDCD1LG2 and TIGIT (Fig. 6A); in LUSC, GPER1 expression is positively correlated with CD27, CD80, CTLA4, PDCD1and TIGIT, but negatively with CD274 (PD-L1) (Fig. 6B).

Analysis of difference of immune checkpoint and TIDE between high and low GPER1 groups. (A) Immune checkpoint gene expression patterns between high and low GPER1 groups in LUAD. (C) TIDE analysis between high and low GPER1 groups in LUAD. (B) Immune checkpoint gene expression patterns between high and low GPER1 groups in LUSC. (D) TIDE analysis between high and low GPER1 groups in LUSC.

GPER1 expression predict response to ICI

In view that GPER1 expression level was significantly associated with both immune cells infiltration and immune checkpoint genes expression in LUAD and LUSC, respectively, we further evaluated the predictive effect of GPER1 expression on response to PD1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) using TCGA NSCLC cohort by TIDE analysis. As shown in Fig. 6D, the low expression of GPER1 could predict benefit from ICIs treatment only in LUSC (P < 0.001), but did not in LUAD (Fig. 6C).

Identification and enrichment analysis of GPER1 repression-related genes of sequencing data

The matching rate was higher than 84.19% in all 12 sequenced samples, indicating that the matching rate was high and not interfered by exogenous RNA molecules, which could meet the need of subsequent data analysis. A total of 1520 DEGs were counted in AA compared with control A, including 801 up-regulated genes and 719 down-regulated genes (Fig. 7A,B). 1520 DEGs were enriched to a total of 1942 GO functions and 76 KEGG pathways. The main functions were collagen-containing ECM, axon development, epithelial cell proliferation, cell–cell junctions, membrane potential regulation, regulation of ion transport across membranes, synaptic organization, metal ion transport protein activity, response to allosteric stimuli, receptor ligand activity, and leukocyte migration (Fig. 7C). Figure 7D showed 25 KEGG entries, such as neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions, MAPK signaling pathway, cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, calcium signaling pathway, cell adhesion molecules, axon guidance, Rap1 signaling pathway, cAMP signaling pathway, proteoglycans in cancer, chemoattractant-receptor activation, Ras signaling pathway, regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, and other entries. AAG had 240 up-regulated genes and 439 down-regulated genes compared to the AA group (Fig. 7E,F), and they were enriched to 1208 GO functions and 46 KEGG pathways, mainly including collagen-containing ECM, regulation of epithelial cell proliferation, amoeboid migration, fatty acid metabolic processes, regulation of trans-synaptic signaling, extracellular matrix organization (Fig. 7G), and ECM-receptor interactions, protein digestion and uptake, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, Apelin signaling pathway, bile secretion and other pathways (Fig. 7H). The up-regulated genes between AA and A groups crossed with the down-regulated genes between AAG and AA groups to obtain 104 crossover genes, and the down-regulated genes between AA and A groups crossed with the up-regulated genes between AAG and AA groups to obtain 28 crossover genes, which 132 genes are GPER1 repression-related genes (Fig. 8A), and they were enriched to 244 GOs and 8 KEGG pathways. The main functions include regulation of chemical synaptic transmission, regulation of small molecule metabolic processes, response to peptide hormones, synaptic organization, phospholipid binding, fatty acid metabolic processes, response to insulin, and the main pathways include protein digestion and absorption, metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450, pentose and glucuronide interconversion, insulin resistance, and glutamatergic synapses (Fig. 8B, C).

Identification and enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes. (A,B) Volcano map and heat map of differentially expressed genes between AA and A groups. (C) GO enrichment map of differentially expressed genes between AA and A groups. (D) KEGG enrichment map of differentially expressed genes between AA and A groups. (E,F) Volcano map and heat map of differentially expressed genes between AAG and AA groups. (G) GO enrichment map of differentially expressed genes between AAG and AA groups. (H) KEGG enrichment map of differentially expressed genes between AAG and AA groups.

Identification of GPER1 activation-related genes

There were 271 DEGs in AG compared with control A, including 110 up-regulated genes and 161 down-regulated genes (Fig. 9A,B). 271 DEGs were enriched for 1942 GOs, including muscle system processes, T cell activation, positive regulation of cytokine production, regulation of ion transport across the membrane, response to nutrient levels, receptor ligand activity, signal receptor activator activity, muscle contraction, lipid transport, lipid localization, and signal release (Fig. 9C). 271 DEGs were also enriched for 2 KEGG pathways, tryptophan metabolism and renin secretion (Fig. 9D). The AAG had 744 up-regulated genes and 971 down-regulated genes compared to the AG group (Fig. 9E,F), and they enriched 2057 GOs and 73 KEGG pathways, including collagen-containing ECM, passive transmembrane transporter protein activity, metal ion transmembrane transporter protein activity, regulation of ion transmembrane transport, epithelial cell proliferation, actin binding, positive regulation of cell adhesion, receptor ligand activity, axonogenesis, and other functions as well as receptor interactions, cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, calcium signaling pathway, and natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity pathways (Fig. 9G,H). In addition, 39 GPER1 activation-associated genes were obtained and they were enriched to 275 GOs and 7 KEGG pathways (Fig. 10A). GPER1 activation-associated genes were mainly associated with positive regulation of cell secretion, positive regulation of hormone secretion, hormone metabolic processes, multicellular biological processes, positive regulation of protein transport, steroid metabolic processes, cortisol synthesis and secretion, neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions, complement and coagulation cascades, IL-17 signaling pathway, and aldosterone synthesis and secretion pathways (Fig. 10B,C).

Identification and enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes. (A,B) Volcano map and heat map of differentially expressed genes between AG and A groups. (C) GO enrichment map of differentially expressed genes between AG and A groups. (D) KEGG enrichment map of differentially expressed genes between AG and A groups. (E,F) Volcano map and heat map of differentially expressed genes between AAG and AG groups. (G) GO enrichment map of differentially expressed genes between AAG and AG groups. (H) KEGG enrichment map of differentially expressed genes between AAG and AG groups.

Identification of 13 GPER1 activation and repression-related hub genes

The PPI network contains 147 nodes and 582 edges (Fig. 11A). The ENO2, LEP, ADM were related to many genes such as KLKB1, LEP, and KIF1A. In addition, the network diagram of the top 20 genes in each algorithm of Degree, MCC and MNC analysis was shown in Fig. 11B. A total of 13 GPER1 activation and repression-related hub genes were present in the three analyses, namely SPP1, KIF1A, SNCA, GRM4, SNAP91, TLR2, AMPH, LEP, MME, PGR, MUC5AC, ADM and ENO2 (Fig. 11C).

Identification of GPER1 activation and repression-related hub genes. (A) PPI interaction network of GPER1 activation and repression-related genes. (B) The network diagram of the top 20 genes in each algorithm of Degree, MCC and MNC analysis. (C) Venn diagram of GPER1 activation and repression-related hub genes.

Construction of upstream and downstream regulatory networks of hub genes

The volcano plots of differential miRNAs, differential lncRNAs, and differential circRNAs between AA and A groups were shown in Fig. 12A–C. A total of 66 differential miRNAs (66 down-regulated differential miRNAs), 316 differential lncRNAs (177 up-regulated differential lncRNAs and 139 down-regulated differential lncRNAs), and 3 differential circRNAs (1 up-regulated differential circRNA, 2 down-regulated differential circRNAs) between AG and A were obtained (Fig. 12D–F). The TF-miRNA–mRNA network contains 26 nodes with 36 edges (4 mRNAs, 8 TFs, 14 miRNAs). Both UBTF and hsa-miR-31-5P can regulate ENO2 and KIF1A, and both hsa-miR-23b-3p and ETS1 can regulate ENO2 (Fig. 12G). In addition, the lncRNA-miRNA–mRNA network contains 32 nodes with 48 edges (5 mRNAs, 15 miRNAs, 12 lncRNAs). LUCAT1 can regulated ADM by hsa-miR-182(1)a-5p, and TEX41 can regulated KIF1A by hsa-miR-107 (Fig. 12H). Moreover, the circRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network analysis contained 4 nodes with 3 edges (2 mRNAs, 1 circRNA, 1 miRNA), hsa-circ-0001460 regulated ADM and SNAP91 by hsa-miR-137 (Fig. 12I).

Construction of upstream and downstream regulatory networks of GPER1 activation and repression-related hub genes. (A–C) The volcano plots of differential miRNAs, differential lncRNAs and differential circRNAs between AA and A groups. (D–F) The volcano plots of differential miRNAs, differential lncRNAs and differential circRNAs between AG and A groups. (G) The TF-mRNA–miRNA network. (H) The mRNA–miRNA–lncRNA network. (I) The mRNA–miRNA–circRNA regulatory network.

The expression of hub genes was verified by qRT-PCR

FGFR3, CFS1 were lowly expressed in Aal and highly expressed in Aal + G1, A549 + G1 compared to A549 and were lower in Aal than in Aal + G1 and A549 + G1 groups. LEP, FGF5, TGFβ2, TLR2 had the highest expression in Aal group and the lowest expression in A549 group. In addition, the expression of LAMB3, ADM was progressively higher in Aal, Aal + G1, and A549 + G1 compared with A549 cells. The expression of HSPG2 was high in Aal, A549 + G1 and low in Aal + G1 compared to A549, and the expression of CHRM3 was lowest in A549 and highest in Aal + G1 (Fig. 13).

Enhanced response of A549 cells to G1 stimulation after overexpression of GPER1

Since sequencing data of A549 cells showed both GPER1 repression- and activation-related genes were involved in MAPK signaling, we assayed the effects of GPER1 expression on the phosphorylation of erk1/2, a downstream effector of MAPK, and on the response of A549 cells to G1, a specific agonist of GPER1. A549 cells with GPER1 knockdown responded with reduced sensitivity to G1 while cells with GPER1 overexpression with enhanced sensitivity when compared with control cells. After treatment with G1 for the indicated time, A549 cells with GPER1 overexpression showed a robust and durable phosphorylation of erk1/2 while cells with GPER1 knockdown presented a delayed phosphorylation of erk1/2 when compared with the control cells (Fig. 14).

Decreased expression of GPER1 promoted actin cytoskeleton rearrangement

Considering that bioinformatic analysis suggested GPER1 involving in cytoskeleton rearrangement, cell–cell junctions and cellular interaction with extracellular matrix, and it is well known that cytoskeleton rearrangement can exert significant influence on the latter two biological processes, we interrogated whether expression alteration of GPER1 affected cytoskeleton rearrangement. As expected, knocking down expression of GPER1 resulted in dramatic actin fibers (F-actin) polymerization, including the formation of actin stress fiber and lamellipodia (GPER1-sh vs. control for actin stress fiber, 42.0 ± 3.1% cells/view vs. 1.2 ± 0.3 cells/view, P < 0.0001), while GPER1 overexpression had little effect on the actin cytoskeleton rearrangements (GPER1-oe vs. control for actin stress fiber, 0.7 ± 0.3% cells/view vs. 1.2 ± 0.3% cells/view, P > 0.05) (Fig. 15).

Actin cytoskeleton rearrangement observation. GPER1 knockdown induced actin fibers (F-actin) polymerization in A549 cells, including the formation of actin stress fiber (thin arrows) and lamellipodia (thick arrows). F-actin were stained with TRITC-conjugated phalloidin (red labeling). knockdown of GPER1 by short hairpin RNA (GPER1-sh), GPER1 overexpression (GPER1-oe).

Knocking down GPER1 promoted the migration of A549 cells

It is well known that cytoskeletal rearrangement is a prerequisite for cell migration. We therefore investigated whether F-actin cytoskeleton rearrangement caused by GPER1 knockdown enhanced the migratory ability of A549 cells using transwell assays. As expect, the migration of A549 cells with GPER1 knockdown (102.0 ± 8.2 cells/view) was significantly enhanced, while cells with GPER1 overexpression (20.3 ± 3.5 cells/view) was significantly decreased when compared with controls (55.7 ± 2.3 cells/view; P < 0.001, P = 0.0042, respectively). Furthermore, Y27632, a pharmacological inhibitor of Rho kinase commonly playing a critical role in F-actin polymerization, notably inhibited migratory ability of A549 cells with GPER1 knockdown (67.0 ± 3.5 cells/view, P = 0.0045). These results revealed that decreased expression of GPER1 could promote the migration of A549 cells, and Rho kinase activity was required for this process (Fig. 16).

Discussion

Lung cancer has the first highest mortality and second highest incidence among all malignances globally, thus understanding its pathogenesis is very essential to develop strategies preventing and curing this disease. In this study, we systematically demonstrated that the expression of GPER1 at the mRNA level was significantly and consistently decreased during tumorigenesis in 22 solid tumors, including NSCLC, which was in line with previous findings in other cancer types, such as breast cancer27, thyroid cancer14,28, gastric cancer17, ovarian cancer13 and hepatocellular carcinoma16. Our results further indicated GPER1 acted as a protective factor in ESCA, KIRC, UCEC, BRCA and LUAD, but was only marginally statistically significant in BRCA and LUAD; in addition, GPER1 was involved in the modulation of immune microenvironment in NSCLC and its low expression could predict the likelihood that LUSC patients will benefit from treatment with ICIs.

By constructing the PPI network, we identified 14 hub genes in LUAD, namely ITGA2, ITGB4, VWF, ITGA3, ITGB6, ICAM1, FGA, A2M, ITGAM, PLAU, CAV1, PLAT, SERPINA1 and KIT. ITGA2, ITGB4, ITGA3, ITGB6 and ITGAM all belong to the integrin family, which mainly mediate the cellular adhesion and interaction with ECM, being associated with drug resistance and worse prognosis in LUAD29,30. Up-regulation of ICAM131 and loss of FGA32 could facilitate tumor metastasis, respectively; the expression of VWF was reported to be decreased during pathogenesis and be related to favorable overall survival in LUAD33; A2M was associated with tumorigenesis and modulation of TIME in LUAD34,35; PLAU was identified as a upregulated gene in early-stage NSCLC36; caveolin-1(CAV1) and PLAT were involved in radio-resistance37 and gefitinib resistance in LUAD38, respectively; SERPINA1 promoted the occurrence of lung cancer in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease39,40; KIT, a proto-oncogene, was upregulated in small cell lung cancer41.

In LUSC, data analysis identified 13 hub genes, including MMP2, SPARC, BMP1, COL1A1, COL1A2, COL3A1, COL5A1, COL5A2, FN1, BGN, DCN, FBN1 and ITGA3. Strikingly, all of these genes were also predominantly involved in ECM assembly and cellular interactions with ECM42. Functional enrichment analysis of hub genes further suggested that GPER1 signaling was mainly involved in cellular adhesion, ECM assembly, regulation of energy, metabolism and cytoskeleton both in LUAD and LUSC. These biological processes were tightly associated with tumor initiation, development and resistance to multiple drugs; furthermore, ECM was demonstrated to can protect tumor cells against attacks from immune cells43,44. Additionally, our data suggested that the expression of GPER1 was concordantly and positively correlated with the expression of six immune checkpoints in LUAD, and positively with five but negatively with only one in LUSC. Beyond these, GPER1 expression tended to be negatively associated with anti-tumor immune cells infiltration, such as Plasma cells, gamma delta T cells and M1 Macrophages in LUAD as well as naive B cells, gamma delta T cells, activated memory CD4 and CD8 T cells in LUSC. However, the TIDE analysis identified that only LUSC with low expression of GPER1 could response well to PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors. We speculated such different functions of GPER1 between LUAD and LUSC may be in that GPER1 can displays different dominant molecular subtypes and subcellular localization according to driver mutation or histology types, as reported in our previous work18,20. Therefore, further research is very needed to investigate whether GPER1 protein undergo posttranslational modification in the future.

In addition, our sequencing data analysis from A549 cell identified 13 hub genes associated with GPER1 activation and repression, including SPP1, KIF1A, SNCA, GRM4, SNAP91, TLR2, AMPH, LEP, MME, PGR, MUC5AC, ADM and ENO2. Among them, LEP45, ADM46 and ENO247 were reported to be elevated in NSCLC and were linked to the diagnosis or prognosis of NSCLC; particularly, ENO2 is being widely utilized as a predictive biomarker in lung cancer in clinical practice. Both SNAP9148 and MUC5AC49 were upregulated and associated with poor prognosis in NSCLC, while the AMPH is a suppressor of lung cancer50; the expression level of PGR could predict better overall survival in LUAD51. Both SPP151,52 and SNCA52 could facilitate immune cells infiltration and are correlated with NSCLC progression. Besides, TLR2 can connect the innate to the adaptive immune system and modulate lung cancer tumorigenesis and metastases52,53. Importantly, KIF1A, GRM4 and MME were firstly reported by us to be related to LUAD; the promoter hypermethylation of KIF1A is associated with tumorigenesis in primary head and neck squamous carcinoma53, and GRM4 was recently found to play an important role in suppressing antitumor immunity in melanoma54.

We conducted whole-transcriptome sequencing and identified GPER1-related differential miRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs and mRNAs for the first time in LUAD cell line; meanwhile, comprehensive regulatory networks among them were built, including TF-miRNA–mRNA, lncRNA–miRNA–mRNA, and circRNA–miRNA–mRNA regulatory networks. A study showed that hsa-miR-31-5P played an important role in the pathogenesis of NSCLC55; Chen et al. reported hsa-miR-23b-3p was involved in mTOR signaling pathway and acted as an oncogenic miRNA in cancer stem cells derived from A549 cells56. The hsa-miR-181a-5p was linked to tumor immune infiltration and cancer progression in NSCLC. The hsa-miR-107 could promote NSCLC cell proliferation by up-regulating FGFRL157. Moreover, the hsa-circ-0001460, also named circNEIL3, was related to radiotherapy resistance in lung cancer58 and was linked to poor prognosis of patients with glioma59, and the hsa-miR-137 was involved in cisplatin resistance in NSCLC60. Besides, the lncRNA LUCAT1 was first discovered in smoking-related lung cancer61 and further demonstrated to be associated with cisplatin resistance in NSCLC62; the lncRNA TEX41 was reported to play an important role in LUAD bone metastasis by promoting autophagy63. These data provide valuable information for further investigating GPER1-related regulatory networks in the future.

Finally, a total of 10 hub genes (CSF1, TLR2, LEP, ADM, HSPG2, LAMB3, CHRM3, FGFR3, FGF5 and TGFB2) were verified to be regulated by GPER1 using qRT-PCR, and Phalloidin-staining showed knocking down expression of GPER1 caused F-actin cytoskeleton rearrangement, being known to function in the initiation and development of tumors64,65. In addition, cytoskeleton rearrangement is essential for cellular interaction with ECM, ECM remolding, cell-cell adhesion and junction as well as malignant progression of tumor cells66,67.

In conclusion, our results showed that the expressions of GPER1 in mRNA level were significantly decreased during the course of tumorigenesis and it appeared to be a protective factor in many types of solid tumor. GPER1 widely participated in various biological functions in NSCLC, including cytoskeleton rearrangement, ECM assembly, regulation of energy and metabolism, and modulation of TIME. Moreover, its low expression could predict benefit from PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors in LUSC patients. However, several limitations should be considered in interpreting our findings. Firstly, these results mainly acquired based on the mRNA expression levels of GPER1. Therefore, in vitro and in vivo experiments are warranted to investigate how GPER1 protein participates in tumorigenesis and immune regulation. Secondly, although our results revealed GPER1 expression is decreased in cancer tissues than their counterpart healthy tissues, its roles in health lung tissue remain less known. Thus, elucidating its functions and relevant mechanisms in both healthy and tumor tissues can provide promising strategies for preventing and curing lung cancer in the future.

Data availability

RNA and small-RNA Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the SRA database with the primary accession code PRJNA1132928 and PRJNA1133192, respectively. TCGA pan-cancer data can be found in TIMER database (http://timer.cistrome.org/) and GEPIA database (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/). RNA-seq data for 21 cancers including LUAD, LUSC, ESCA, and BRCA were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) database. The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) database and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) database.

Change history

25 September 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article the Equal Contribution statement was incorrect. The statement has been updated and now reads: “Zhenhua Li and Chao Xie contributed equally to this work.” The original Article has been corrected.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

Adrenocortical carcinoma

- BLCA:

-

Bladder urothelial carcinoma

- BRCA:

-

Breast invasive carcinoma

- CESC:

-

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma

- CHOL:

-

Cholangiocarcinoma

- COAD:

-

Colon adenocarcinoma

- DLBC:

-

Lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- ESCA:

-

Esophageal carcinoma

- GBM:

-

Glioblastoma multiforme

- HNSC:

-

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- KICH:

-

Kidney chromophobe

- KIRC:

-

Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma

- KIRP:

-

Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma

- LAML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- LGG:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- LIHC:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- LUAD:

-

Lung adenocarcinoma

- LUSC:

-

Lung squamous cell carcinoma

- MESO:

-

Mesothelioma

- OV:

-

Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma

- PAAD:

-

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- PCPG:

-

Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma

- PRAD:

-

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- READ:

-

Rectum adenocarcinoma

- SARC:

-

Sarcoma

- SKCM:

-

Skin cutaneous melanoma

- STAD:

-

Stomach adenocarcinoma

- TGCT:

-

Testicular germ cell tumors

- THYM:

-

Thymoma

- THCA:

-

Thyroid carcinoma

- UCEC:

-

Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma

- ESCA:

-

Esophageal carcinoma

- UCS:

-

Uterine carcinosarcoma

- UVM:

-

Uveal melanoma

References

H, S. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3). https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

T, V. et al. Gender differences and immunotherapy outcome in advanced lung cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (21). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111942 (2021).

A, J. et al. Higher lung cancer incidence in young women than young men in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 378 (21). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1715907 (2018).

Yj, C. et al. Proteogenomics of non-smoking lung cancer in East Asia delineates molecular signatures of pathogenesis and progression. Cell 182 (1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.012 (2020).

H, L. et al. The clinicopathological and prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression assessed by immunohistochemistry in lung cancer: A meta-analysis of 50 studies with 11,383 patients. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 8 (4). https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr.2019.08.04 (2019).

F, C. et al. Cancer immunotherapy efficacy and patients’ sex: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Oncol. 19 (6). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30261-4 (2018).

F, C. et al. Sex-Based differences in response to Anti-PD-1 or PD-L1 treatment in patients with Non-Small-Cell lung cancer expressing high PD-L1 levels. A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of randomized clinical trials. ESMO Open. 6 (5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100251 (2021).

J, D. K. et al. Lung cancer in women in 21th century. J. Thorac. Dis. 12 (8). https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-287 (2020).

M, B. et al. Twenty years of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER: Historical and personal perspectives. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.03.021 (2018).

S., G. et al. Roles of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER in metabolic regulation. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 176 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.02.012 (2018).

G, N. et al. G Protein-coupled estrogen receptor in immune cells and its role in immune-related diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.579420 (2020).

Na, M. et al. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor regulates mammary tumorigenesis and metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR. 12 (11). https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0128-T (2014).

T, I. et al. GPER-1 acts as a tumor suppressor in ovarian cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 6 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-2215-6-51 (2013).

Ck, C. et al. Decreased expression of estrogen receptors is associated with tumorigenesis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (3). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031015 (2022).

V, R. et al. Identification of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) in human prostate: expression site of the estrogen receptor in the benign and neoplastic gland. Andrology. 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.12131 (2016).

T, W. et al. G Protein-coupled estrogen receptor deficiency accelerates liver tumorigenesis by enhancing inflammation and fibrosis. Cancer Lett. 382 (2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2016.08.012 (2016).

S, T. et al. Downregulation of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) is associated with reduced prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 25 https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.913634 (2019).

Zh, L. et al. Cytoplasmic expression of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 correlates with poor postoperative prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 14 (5). https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-22-29 (2022).

Vr, J. et al. Enhanced expression of G-protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPER/GPR30) in lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 12 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-624 (2012).

Z, L. et al. Role of GPER1 in the mechanism of EGFR-TKIs resistance in lung adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.869113 (2022).

Me, R. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (7). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv007 (2015).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28 (11), 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1), D587–D592. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2023).

G, Y. et al. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics J. Integr. Biol. 16 (5). https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2011.0118 (2012).

Mi, L. et al. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-Seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15 (12). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

T, I. et al. GPER-1 expression decreases during breast cancer tumorigenesis. Cancer Investig. 31 (5). https://doi.org/10.3109/07357907.2013.789901 (2013).

Aps, B. et al. The gene expression of GPER1 is low in fresh samples of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), and in silico analysis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 535 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2021.111397 (2021).

P, K. et al. Organization, dynamics and mechanoregulation of Integrin-Mediated Cell-ECM adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24 (2). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-022-00531-5 (2023).

X, P. et al. Targeting integrin pathways: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 8 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01259-6 (2023).

K, W. et al. Vertebral-Specific activation of the CX3CL1/ICAM-1 signaling network mediates non-small-cell lung cancer spinal metastasis by engaging tumor cell-vertebral bone marrow endothelial cell interactions. Theranostics. 11 (10). https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.54235 (2021).

M, W. et al. Fibrinogen alpha chain knockout promotes tumor growth and metastasis through Integrin-AKT signaling pathway in lung cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR. 18 (7). https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-1033 (2020).

Y, H. et al. Identification of VWF as a novel biomarker in lung adenocarcinoma by comprehensive analysis. Front. Oncol. 11 https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.639600 (2021).

J, M. et al. Reconstruction and analysis of the immune-related LINC00987/A2M axis in lung adenocarcinoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2021.644557 (2021).

Hc, L. et al. Downregulated ADAMTS1 incorporating A2M contributes to tumorigenesis and alters tumor immune microenvironment in lung adenocarcinoma. Biology. 11 (5). https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11050760 (2022).

Metodieva, S. N. et al. Expression analysis of angiogenesis-related genes in bulgarian patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Tumori. 97 (1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/030089161109700116 (2011).

D, L. et al. Role of Caveolin-1 as a biomarker for radiation resistance and tumor aggression in lung cancer. PLoS One. 16 (11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258951 (2021).

M, Y. et al. Knockdown of PLAT enhances the anticancer effect of gefitinib in Non-Small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 12 (3). https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.12.106 (2020).

Ly, Z. et al. SERPINA1 methylation levels are associated with lung cancer development in male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 17 https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S368543 (2022).

E, E. et al. Clinical significance of SERPINA1 gene and its encoded Alpha1-antitrypsin protein in NSCLC. Cancers . https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11091306 (2019).

Kh, K. et al. Antibody-Drug conjugate targeting c-Kit for the treatment of small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23042264 (2022).

Ad, D. et al. Cell-extracellular matrix dynamics. Phys. Biol. 19 (2). https://doi.org/10.1088/1478-3975/ac4390 (2022).

Dh, P. et al. ZEB1 induces LOXL2-mediated collagen stabilization and deposition in the extracellular matrix to drive lung cancer invasion and metastasis. Oncogene. 36 (14). https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2016.358 (2017).

Ja, G. et al. Spatial positioning and matrix programs of cancer-associated fibroblasts promote T-cell exclusion in human lung tumors. Cancer Discov. 12 (11). https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1714 (2022).

J, W. et al. Autocrined leptin promotes proliferation of Non-Small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) via PI3K/AKT and P53 pathways. Ann. Transl. Med. 9 (7). https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-7482 (2021).

S, B. et al. Adrenomedullin expression does not correlate with survival in lung cancer. Med. Oncol. (Northwood, London, England) 24(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02698047 (2007).

D, L. et al. Expression patterns and clinical significances of ENO2 in lung cancer: an analysis based on oncomine database. Ann. Transl. Med. 8 (10). https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3354 (2020).

Yf, G. et al. COL3A1 and SNAP91: novel glioblastoma markers with diagnostic and prognostic value. Oncotarget. 7 (43). https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12038 (2016).

Y, D. et al. MUC5AC enhances tumor heterogeneity in lung adenocarcinoma with mucin production and is associated with poor prognosis. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 50 (6). https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyaa016 (2020).

H, Y. et al. AMPH-1 is a tumor suppressor of lung cancer by inhibiting Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK signal pathway. Lasers Med. Sci. 34 (3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-018-2616-4 (2019).

R, B. et al. Hormonal receptors in lung adenocarcinoma: expression and difference in outcome by sex. Oncotarget. 7 (50). https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12244 (2016).

X, Z. et al. SNCA correlates with immune infiltration and serves as a prognostic biomarker in lung adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09289-7 (2022).

S, D. et al. KIF1A and EDNRB are differentially methylated in primary HNSCC and salivary rinses. Int. J. Cancer. 127 (10). https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.25248 (2010).

Z, W. et al. Targeting metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 for cancer immunotherapy. Sci. Adv. 7 (50). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj4226 (2021).

Jin, X. et al. Microarray data analysis on gene and MiRNA expression to identify biomarkers in Non-Small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 20 (1), 329. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-06829-x (2020).

Chen, Q. Y. et al. Identification of carcinogenic Potential-Associated molecular mechanisms in CD133(+) A549 cells based on MicroRNA profiles. Tumour Biol. 37 (1), 521–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-015-3675-9 (2016).

Fan, Y. et al. Long Non-Coding RNA FGD5-AS1 promotes Non-Small cell lung cancer cell proliferation through sponging Hsa-miR-107 to up-Regulate FGFRL1. Biosci. Rep. 40 (1), BSR20193309. https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20193309 (2020).

Zhang, T. et al. CircNEIL3 mediates pyroptosis to influence lung adenocarcinoma radiotherapy by upregulating PIF1 through miR-1184 Inhibition. Cell. Death Dis. 13 (2), 167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-04561-x (2022).

Pan, Z. et al. EWSR1-Induced circNEIL3 promotes glioma progression and Exosome-Mediated macrophage immunosuppressive polarization via stabilizing IGF2BP3. Mol. Cancer. 21 (1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-021-01485-6 (2022).

Zhu, K. et al. circSNX6 (Hsa_circ_0031608) enhances drug resistance of Non-Small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) via miR-137. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 567, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.06.032 (2021).

Xing, C. et al. Role of LncRNA LUCAT1 in cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 134, 111158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111158 (2021).

Shen, Q. et al. Long non-coding RNA LUCAT1 contributes to cisplatin resistance by regulating the miR–514a–3p/ULK1 axis in human non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 57 (4), 967–979. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2020.5106 (2020).

Han, L. et al. Transcriptome sequencing reveals the expressed profiles of mRNA and NcRNAs and regulate network via CeRNA mediated molecular mechanism of lung adenocarcinoma bone metastasis in Xuanwei. Transl. Cancer Res. 10 (1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.21037/tcr-20-2376 (2021).

A, H. The cytoskeleton and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28 (1–2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-008-9166-3 (2009).

X, L. et al. Mechanical tumor microenvironment and transduction: cytoskeleton mediates cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16 (12). https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.44943 (2020).

Ai, B. et al. Actin-Based adhesion modules mediate cell interactions with the extracellular matrix and neighboring cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 9 (7). https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a023234 (2017).

Ja, E. et al. From the ECM to the cytoskeleton and back: how integrins orchestrate T cell action. Dev. Immunol. 7, 2–4. https://doi.org/10.1155/2000/86281 (2000).

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82460698), the Yunnan Provincial Department of Science and Technology-Kunming Medical University Applied Basic Research Project (No. 202301AY070001-173), and the Key Laboratory of Tumor Immunological Prevention and Treatment of Yunnan Province (No. 2017DG004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the project conception and design. Z.L. and C.X. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12. J.C. prepared Figs. 13 and 14. H.X. and D.L. conducted the experiments and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

All authors agree to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Xie, C., Cui, J. et al. GPER1 is involved in shaping tumor immune microenvironment and its expression is decreased in NSCLC tumorigenesis. Sci Rep 15, 29488 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15405-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15405-x