Abstract

The Anthriscus sylvestris complex (Apiaceae) exhibits a wide ecological and geographical diversity around the Mediterranean and in Central Europe. This study aims to explore its historical biogeography. Network and phylogenetic analyses were performed using the variation in two nuclear markers (nrDNA ITS and waxy intron) and three plastid markers (rpoB–trnC, trnS–trnG, and psbA–trnH intergenic spacers) assessed for 296 accessions. Nuclear and plastid markers disagreed with each other and with the current taxonomy of the complex. Two ribogroups, Nit and Syl, were apparent, with the former encompassing mountainous taxa from the Balkan Peninsula and Central Europe and the latter uniting remaining accessions. Plastid data suggested a Middle Eastern origin of the complex, with migration to Europe around the Mediterranean through the Iberian Peninsula, and a secondary contact with another migration wave in the Balkans. However, a scenario with two migration waves to Europe through the Balkans cannot be excluded. Waxy data distinguished a more detailed geographical and ecological pattern. The estimated age of the A. sylvestris complex based on the plastid data was 1.72 Ma, whereas the divergence within the European group began approximately 0.44 Ma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The aridification of the climate in the Miocene and the onset of the Pleistocene Ice Age almost completely wiped out the tropical forest flora of Europe1,2, whose remnants were confined to the Mediterranean region and supplemented with taxa adapted to temperate and arid climates, such as Arctotertiary floristic elements or xerophytes2. The Ice Age severely depleted the biodiversity of Europe and the Mediterranean but also increased diversification through allopatric speciation in glacial refugia and during the onset of the Mediterranean climate. Phylogenetic studies reveal some common cladogenetic and phylogeographic patterns in the Mediterranean plants3,4,5. The same events—namely, the periods of repetitive glaciations, the Messinian salinity crisis, and the onset of the Mediterranean climate—also affected the taxa inhabiting mountain ranges in Europe and around the Mediterranean region, contributing to their diversification and circum- or amphi-Mediterranean disjunctions6,7. These taxa are not Mediterranean in the strict sense, i.e., they are not adapted to the Mediterranean climate, but their biogeographic history is linked to the geoclimatic changes of the Mediterranean Basin. In contrast to the strictly Mediterranean plants, the mountainous taxa in the Mediterranean Europe do not seem to exhibit a common diversification pattern8, pointing out to the complex biogeographic history of the region.

Among the immigrant taxa adapted to temperate and arid climates of the Pleistocene Europe and the Mediterranean region were Apiaceae subfamily Apioideae. These are mostly plants of open, often dry habitats9, and biogeographic reconstructions suggest that the Mediterranean and western Asia played a significant role in their diversification10. An intriguing example of a non-Mediterranean taxon but with the center of diversity around the Mediterranean is Anthriscus sect. Cacosciadium (Apiaceae), also identified as A. sylvestris (L.) Hoffm. sensu lato (s.l.) or the Anthriscus sylvestris complex11,12,13. It includes A. nitida, A. lamprocarpa, A. schmalhausenii, and a polymorphic A. sylvestris encompassing at least four subspecies (Table 1). Anthriscus sylvestris subsp. sylvestris is widespread and occurs from temperate Europe through the mountains of Central Asia to the Far East, and in the mountains of North Africa and the tropical East Africa. In the mountains of Southeast Europe, the Middle East, and the Irano-Turanian floristic region, it is replaced by subsp. nemorosa, which differs from subsp. sylvestris in having tuberculate bristled fruits as opposed to glabrous fruits in the former. Interestingly, the populations inhabiting the mountains of tropical East Africa are mixed with respect to fruit indumentum: although most have smooth fruits, some plants with tuberculate fruits also occur.

In the eastern Mediterranean (SE Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel), subsp. nemorosa is replaced by Anthriscus lamprocarpa that has glabrous fruits. These two taxa are parapatric and may have evolved from a common ancestor through geographic isolation. Alternatively, A. lamprocarpa may have originated from North African populations of A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris (once placed in a separate subspecies mollis), as these show some similarity in habit11, However, at present there is a considerable geographical gap between these two taxa. In contrast, the European endemic taxa—A. nitida, A. sylvestris subsp. fumarioides, and A. sylvestris subsp. alpina—are sympatric with A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris, but they are ecologically differentiated. This suggests the importance of ecological rather than geographical barriers in their diversification. A molecular phylogenetic study based on nrDNA ITS sequence variation confirmed the monophyly of the A. sylvestris group but suggested that the widely distributed subsp. sylvestris is paraphyletic, albeit with a very low internal support14.

In Europe, A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris typically thrives in lowland habitats, primarily in riparian forest, but most frequently occupying anthropogenic environments such as wet meadows and roadsides. In contrast, A. nitida is primarily found within the beech-forest belt of the Central and Southeast European mountains, spanning from the Alps and Vosges to the Carpathians and Balkans. Within the Alps and Vosges, it coexists with A. sylvestris subsp. alpina, which occurs in open or partially shaded subalpine screes. Both taxa exhibit glabrous fruits, distinguishing them from A. sylvestris subsp. fumarioides, which possesses tuberculate fruits and is found in partially shaded subalpine screes within the western Balkan Peninsula mountains, akin to the habitats of subsp. alpina. This extensive ecological range of the A. sylvestris complex, encompassing lowland to subalpine locations and spanning open anthropogenic environments to mature shaded forests, is unparalleled among any other umbellifer species or species complexes found in Europe11,15. Questions arise about the origin of this diversity and the relationships among the taxa included, particularly of the narrow endemics in relation to the widely distributed subspecies sylvestris and nemorosa. Former biogeographic analyses suggested that the tribe Scandiceae and most of its genera, including Anthriscus, originated in the Middle East10, and spread from there to Europe and the rest of Asia. The currently recognized taxa may have therefore originated through geographic isolation (allopatric speciation), particularly in the glacial refugia in Europe and the Caucasus. However, an important question is whether these taxa—defined as morphotypes and ecotypes—are indeed genetically differentiated.

There is growing evidence for the role of a “combinatorial” mechanism of speciation: old genetic variation, previously tested by selection and occurring at higher allele frequency than new mutations, may speed up speciation and facilitate adaptive evolution16. These old genetic variants may be obtained from conspecific, formerly isolated populations or from closely related species due to hybridization and introgression. Therefore, an additional question is whether central and southeastern Europe, the area with the highest diversity of the A. sylvestris group, might have also been the place of secondary contact between two migration waves, spurring the ecological and morphological diversification.

The A. sylvestris complex occurs around the Mediterranean, raising the questions of what the migration routes were and whether the distribution ring closed. It has been suggested that A. lamprocarpa originated from North African populations of A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris11,12, implying that the ring closed in the Levant, with A. lamprocarpa and A. sylvestris subsp. nemorosa representing the most genetically distant populations. The drawback of this hypothesis is the significant distribution gap between A. lamprocarpa and the North African populations of A. sylvestris, as this taxon is absent from Libya and Egypt. However, these taxa may have been present in this region in the past, when the climate was cooler and more humid. An alternative hypothesis tested in this study is that the Balkans served as a secondary contact zone for divergent lineages within the Anthriscus sylvestris complex. The presence of morphologically and ecologically distinct forms in this region suggests that range overlap and lineage mixing may have driven the diversification of montane A. nitida and A. sylvestris subsp. fumarioides, alongside lowland or low-montane A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris and subsp. nemorosa. The coexistence of A. nitida and A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris in the Carpathians, the Balkans, and the Alps further raises questions about their genetic distinctiveness.

This study aims to explore the historical biogeography of the Anthriscus sylvestris complex in order to infer its origin and migration routes, and, in particular, to identify possible areas of secondary contact between migration waves that may have contributed to the diversification of this taxon.

Materials and methods

Molecular markers

Phylogenetic relationships were inferred from two nuclear markers—rDNA ITS and waxy—and three plastid (pDNA) intergenic spacers: rpoB–trnC, trnS–trnG and psbA–trnH. The nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer has previously been successfully used in phylogenetic analyses of umbellifers, both at the subfamily Apioideae level17 and at the infrageneric level18,19. The granule-bound starch synthase I gene—GBSSI or waxy—is a single-copy nuclear gene that appears to be more phylogenetically informative than ITS at the infrageneric level20. This marker has not yet been used in phylogenetic studies of apioid umbellifers. The intergenic spacers rpoB–trnC, trnS–trnG, and psbA–trnH are among the most variable and commonly used plastid markers21,22. They were also applied in phylogenetic studies of umbellifers at the infrageneric level23,24,25.

Taxon identification and sampling

We paid attention to two key morphological markers crucial for distinguishing sympatric taxa: fruit tuberculation and basal (or lower cauline) leaf size11. Small tubercles ending in short bristles that cover the entire fruit are distinguishing features of A. sylvestris subsp. nemorosa and subsp. fumarioides, setting them apart from sympatric or parapatric A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris, A. lamprocarpa, and A. schmalhausenii (Fig. 1a). These bristles are also visible on ovaries, enabling identification of these taxa during the flowering stage.

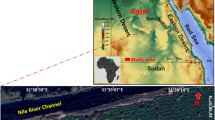

(a) Species and subspecies of Anthriscus sect. Cacosciadium considered in this study. (b) Location of plant samples. Shapes denote respective taxa (see the legend). Shapes with dots denote plants with bristled ovaries or fruits. Inset presents dense sampling of mountainous A. nitida and lowland A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris in their contact zone in southern Poland.

The size of the primary leaf division helps distinguish A. nitida from A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris. If it is similar to the rest of the blade (i.e., the leaf is tripartite rather than pinnatisect), then the specimen is likely to be A. nitida. In contrast, if the primary division is distinctly smaller than the rest of the blade (i.e., the leaf is distinctly pinnatisect rather than tripartite), then the plant may be identified as A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris.

Additionally, we considered the presence of short bristles or scales at the base of the fruit (present in A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris, absent in A. nitida) and the length of pedicels (pedicels longer than fruits in A. nitida, pedicels shorter than fruits in A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris). Specimens displaying intermediate characteristics collected in a potential suture zone in the Carpathians were identified as hybrids, A. sylvestris × A. nitida.

In total, 296 accessions were sampled from herbarium collections and from the wild (voucher specimens are listed in Table S1, the plant material was used in accordance with all relevant guidelines and legislation.). The outgroup to Anthriscus included three species of Kozlovia, a genus identified as its sister in previous molecular studies14. To provide proper rooting of sect. Cacosciadium, all species of the other sections of the genus were also considered, each represented by at least two accessions. The A. sylvestris complex included 273 samples representing all recognized taxa and covering its entire natural range in Eurasia, North Africa and mountains of tropical East Africa11 (Fig. 1b). Because our preliminary results indicated occurrence of different ribotypes (nrDNA ITS) in mountainous A. nitida and lowland A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris, we densely sampled these taxa from the wild in the Polish Carpathians and the Sudeten Mountains (inset in Fig. 1b). As the preliminary results indicated a low resolution of plastid data for the European taxa, these additional samples were examined only for ITS sequence variation.

Molecular analyses

Total genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 20 mg of plant tissue (leaves, flowers or immature fruits) using the DNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For amplification of ITS sequences, the external primers NnC18S10 and C26A were used26. However, due to DNA degradation in some herbarium specimens, amplifying the entire ITS region was challenging. In such cases, ITS1 and ITS2 were separately amplified using the primers 18S-ITS1-F and 5.8S-ITS1-R for ITS1 and ITS3-N and C26A for ITS227, then assembled based on overlapping conserved sequence of 5.8S rDNA. All 296 samples were successfully sequenced for the ITS region. Occasional polymorphic sites were marked using IUPAC codes.

Plastid rpoB–trnC, trnS–trnG, and psbA–trnH intergenic spacers were amplified using standard external primers21. However, for some samples it was impossible to obtain the entire rpoB–trnC spacer, so alternative external and internal primers were designed using PrimerSelect28: renF (ATTCTGCTACTTAGGCTTAC), renR (AAGGATACATAACMAATCAG), 1R (TTCATTTTTCTGGTATTC), 2R (AAAAATACAACCCCTCTT), 3F (GCATACGCTAAGGATTGTG), 3R (ATTTGAACCATTAACTATTGACTC), and 4R (TTTTTAGTTTCTTGTGTCATTAG). PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing protocols are given elsewhere24,27. All three plastid regions were successfully obtained for 101 samples.

Due to DNA degradation in herbarium samples, amplifying the entire granule-bound starch synthase I gene was impossible. Additionally, amplifying the gene in parts and reassembling was impractical due to the presence of two different alleles in several accessions as all species of Anthriscus sylvestris complex are diploid with 2n = 16. Therefore, we chose a region covering approximately 640 bp and spanning from exon 10 to exon 13. This region was amplified using primers 10F and 13R29. The amplification was successful for 40 samples, but direct sequencing of the PCR products for 11 samples revealed allele polymorphisms. To resolve the sequences of these alleles, PCR products were cloned using a PCR Cloning Kit (Qiagen) and JM109 Competent Cells (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA), and then sequenced. Effectively, 51 sequences were included in subsequent analyses.

Contig sequences were assembled and edited using SeqMan28. All sequences have been deposited in GenBank (see Table S1). For each marker, DNA sequences were aligned using mafft v. 7.27130, and the resulting matrix was manually corrected if necessary using Mesquite v. 3.631 or AliView v. 1.2832. In the psbA–trnH intergenic spacer, a highly homoplastic inversion of 12 base pairs occurred in several accessions. This inversion is common in many species of umbellifers at infraspecific level33. Therefore, it was excluded from phylogenetic analyses.

Voucher data and GenBank accession numbers are given in Table S1. Matrices and trees were deposited in the University of Warsaw repository danebadawcze.uw.pl, https://doi.org/10.58132/WACYXJ .

Network, phylogenetic and phylogeographic analyses

The congruence of molecular markers was assessed in two datasets: a 101-accession dataset (pDNA + ITS), and a 51-accession dataset (pDNA + ITS + partial waxy gene). This evaluation was conducted using a hierarchical likelihood ratio test, as implemented in Concaterpillar v. 1.7.234. To accommodate the heterozygosity observed in 11 samples for the waxy gene, the pDNA and ITS data were duplicated for each respective sample. Characteristics of the datasets are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Haplotype networks were constructed using TCS method35, as implemented in POPART v. 1.736. For these analyses, polymorphic sites were resolved to minimize branch lengths, whereas sites with indels were excluded. As the outgroup, we only used the species of Anthriscus, because the inclusion of Kozlovia did not impact the relationships within A. sylvestris s.l. while, due to the long branches, made it challenging to visualize the networks.

Phylogenetic trees were inferred using both maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods. Each group of identical sequences was represented by a single terminal in the analyses. ML analyses were conducted using RAxML v. 8.2.437, utilizing the GTR + G nucleotide substitution model, the only model available in this program. Tree internal support was estimated through 1000 rapid bootstrap replicates.

The optimal nucleotide substitution models for BI analyses were determined for each dataset using PartitionFinder238 utilizing BIC criterion. BI trees were generated using a parallel version of MrBayes v. 3.2.639 with default priors. The analyses involved two independent runs of four Monte Carlo Markov chains for a total of 10 million generations, with samples taken every 1000 generations. A burn-in of 25% was applied. The convergence of runs and the effective sample size were assessed using Tracer v. 1.7.140. The resulting trees were summarized into a 50% majority rule consensus tree.

Divergence times were estimated using BEAST v. 1.10.441, separately for the ITS and pDNA data. To calibrate the trees, we utilized the divergence between Kozlovia and Anthriscus, previously estimated from the ITS analyses of Apioideae10. To implement this calibration, we assumed a normal prior distribution with a mean of 8.792265616 and a standard deviation of 1.158792094 as inferred based on the analysis of posterior sample from the previous study. This prior distribution was applied to the root of the tree.

We estimated divergence times with topological constrains enforcing Kozlovia and Anthriscus to be monophyletic taxa. In these analyses, the tree topology was estimated concurrently with the divergence times. The chain length, sampling frequency, and DNA substitution models were consistent with the parameters used in the previous MrBayes analyses.

The results of the network and phylogenetic analyses were also considered in a geographic context. All samples were georeferenced using point-radius method implemented in Georeferencing Calculator42. Geographic patterns were visualized with ArcGIS 10.8.2.43.

Results

Molecular markers’ congruence

Hierarchical clustering of the markers in the 101-terminal dataset concatenated rpoB–trnC and trnS–trnG spacers with P = 1.0, and these two with psbA–trnH spacer with P = 0.21. However, it rejected joining pDNA data and ITS data with P = 0.006. In the 51-terminal dataset encompassing all markers, waxy data were not incongruent with ITS data, but with a rather low P = 0.076. Therefore, in subsequent network and phylogenetic analyses, ITS, pDNA, and partial waxy datasets were analyzed separately.

Haplotype network analyses

For haplotype network analyses, we used full matrices containing 296 (ITS), 101 (pDNA), and 51 (waxy) sequences, respectively.

Among the 296 ITS haplotypes (ribotypes), two ribotypes—denoted thereafter as Syl and Nit ribotypes—were most common (Fig. 2a). Ribotype Nit differs from ribotype Syl in two substitutions and one deletion (that was omitted in the network analyses), a possibly synapomorphic combination. The Syl ribotype and derived ribotypes form the Syl ribogroup, which is geographically and taxonomically widespread. In Europe, it is characteristic for lowland A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris and mountainous subsp. alpina as well as for the representatives of A. nitida from western Europe; it also encompasses A. lamprocarpa, A. schmalhausenii, and non-European representatives of A. sylvestris subsp. nemorosa (Fig. 2b).

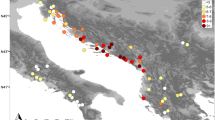

Sequence variation and geographical distribution of nrDNA ITS haplotypes of the A. sylvestris complex. (a) TCS haplotype network; pie-chart colors correspond to taxa, whereas Syl and Nit ribotype groups are indicated with tint. (b) Geographical distribution of Syl and Nit ribotype groups; the groups are marked with color while shapes denote taxa. The sample of A. nitida that provided the ribotype intermediate between both ribogroups is marked with white square.

In the broadly defined Syl ribogroup, there are ribotypes that differ from the Syl ribotype in up to four substitutions, which is greater than the difference between the Syl and Nit ribotypes. Some of these variations are found in accessions from outside of Europe, areas that have not been studied as thoroughly as Europe. With more extensive sampling, it is possible that some of these accessions will form distinct ribogroups.

In contrast to Syl, the ribogroup Nit is geographically constrained and occurs in A. nitida, A. s. subsp. nemorosa, and A. s. subsp. fumarioides from the Carpathians and the Balkan Peninsula (Fig. 2b). In Poland, ribotype Nit is restricted to the Carpathian representatives of A. nitida, while ribotype Syl occurs in A. s. subsp. sylvestris and A. nitida specimens from the Sudeten Mountains (see the inset in Fig. 2b). Specimens of A. s. subsp. sylvestris with Nit ribotype and those of A. nitida with Syl ribotype, as well as plants with intermediate features were also sporadically found, indicating possible hybridization in the contact zone. It is noteworthy that the rooting of the network is ambiguous as the outgroups representing other species of Anthriscus did not form a group.

A strong geographical structure, rather than a taxonomical one, is evident in plastid sequence variation (Fig. 3). In the haplotype network (Fig. 3a), the central haplogroup, henceforth referred to as L, comprises representatives of A. lamprocarpa and A. s. subsp. nemorosa from the eastern Mediterranean, specifically the Levant and Asia Minor (Fig. 3b). Nearly all European samples, regardless of their taxonomical origin, fall into haplogroup E, which is connected to haplogroup L by the North African haplogroup F. The majority of western and central Asiatic accessions of A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris and subsp. nemorosa belong to haplogroup A, with one accession from central Asia positioned closer to the eastern Asiatic C haplogroup, which unites specimens from China, the Russian Far East, and Japan. Haplogroup A also includes Afromontane samples, i.e., from tropical East Africa. The rooting of the A. sylvestris s.l. tree is, however, ambiguous: it could either indicate that haplogroup L was ancestral to the others, or that the primary split occurred between the western (L + F + E) and eastern (A + C) groups.

Plastid haplotype variation and geographical distribution of the A. sylvestris complex. (a) TCS haplotype network; pie-chart colors refer to taxa, whereas plastid haplotype groups are indicated with tint. (b) Geographical distribution of haplotype groups; the groups are marked with color and shapes identify taxa.

In the haplotype network for the waxy gene (Fig. 4a), similar to the ITS network, eastern and south-eastern European accessions of A. sylvestris subsp. nemorosa and subsp. fumarioides, along with A. nitida – all characterized by the Nit ribotype – were grouped together. However, in contrast to the ITS network, this group, hereafter designated as the Euromontane group, also included accessions of A. nitida and A. sylvestris subsp. alpina from the Alps, all of which had the Syl ribotype. The remaining European accessions, primarily consisting of plants from lower elevations, formed the European lowland group. Asiatic and mountainous accessions from the tropical East Africa constituted another haplogroup, hereafter referred to as the Afroasiatic group. North African accessions formed a branch that was equidistant from the European lowland group and from the Afroasiatic group. Therefore, the pattern of variation in the partial sequence of the waxy gene appears to reflect both the geography and ecology of the included accessions (Fig. 4b). The rooting of the network remains ambiguous, as the outgroup is connected either to the Afroasiatic group or the European lowland group.

Partial waxy allele variation and geographical distribution of the A. sylvestris complex. (a) TCS haplotype network; pie-chart colors refer to taxa, whereas allele groups are indicated with tint. (b) Geographical distribution of allele groups; the groups are marked with color and shapes identify taxa. White shapes indicate intermediate haplotypes.

Phylogenetic analyses

Because the plastid DNA, rDNA ITS, and partial waxy sequences displayed incongruence in hierarchical likelihood tests as well as somewhat different geographical and ecological patterns in the network analyses, the respective datasets were subject to separate phylogenetic analyses. Additionally, each group of identical sequences was represented by a single terminal. This resulted in 58 terminals for the ITS dataset, 63 terminals for the pDNA dataset, and 32 terminals for the waxy dataset. PartitionFinder returned SYM + G, GTR + G and HKY + G models of nucleotide substitution for ITS, pDNA and waxy datasets, respectively.

The ITS trees (Fig. S1) obtained using maximum likelihood and Bayesian methods showed poor resolution. The monophyly of the A. sylvestris complex was strongly supported (BS = 100%; PP = 1.0) with the most of Nit ribotype group practically forming a basal polytomy, due to very short internal branches. Similarly to the network analyses, the relationships within the Syl ribotype group remained unresolved. This group, in addition to A. s. subsp. sylvestris and subsp. nemorosa, also included A. s. subsp. alpina, A. nitida from France, A. lamprocarpa, and A. schmalhausenii. Section Cacosciadium was identified as the sister group to the section Anthriscus, comprising A. caucalis and A. tenerrima (BS = 77%, PP = 0.99).

Analogously to the network analyses, plastid DNA trees exhibited a clear phylogeographic pattern. The root of the sect. Cacosciadium was different in ML and BI trees (although consistent with the network analysis: cf. Figure 3). In ML tree (Fig. 5), an accession of A. s. subsp. nemorosa from Turkey (#1276) was placed sister to the remaining representatives of the A. sylvestris complex, followed by A. lamprocarpa. In BI trees (Fig. S3), A .s. nemorosa #1276 was embedded, with A. lamprocarpa, in a trichotomy with a clade comprising the North African (F) and European accessions (E), whereas the main split was between western (L + F + E) and eastern (A + C) groups (cf. Figure 3a).

Maximum likelihood tree obtained from concatenated plastid rpoB–trnC, trnS–trnG, and psbA–trnH spacers. Pie-chart colors correspond to taxa, and plastid haplotype groups are indicated with tints, as in Fig. 3. Two common haplotypes in haplogroups E and A are denoted by the letters of their respective haplogroup, with the number of samples in parentheses. Bootstrap support values (> 50%) and posterior probabilities (when available, > 0.5) from additional Bayesian analyses are indicated along the branches. For simplicity, Kozlovia was omitted.

In the waxy ML trees (Fig. S2A), the North African, Euromontane, and Afroasiatic groups from the network analysis formed clades nested within the paraphyletic European lowland group. Interestingly, the Euromontane clade included all examined samples of A. nitida, both those carrying the Nit ribotype and Syl ribotype, thereby highlighting an ecological component of sequence variation within this molecular marker. However, in the Bayesian analyses (Fig. S2B), only the Euromontane and North African clades were retained.

It is noteworthy that various markers indicated different sister taxa to sect. Cacosciadium: ITS data supported its affinity to sect. Anthriscus, encompassing A. caucalis and A. tenerrima, whereas plastid sequences pointed to sect. Caroides, consisting of A. kotschyi and A. ruprechtii, albeit with a moderate internal support (BS = 72%; PP = 0.85).

In all trees except for the ML plastid tree, A. caucalis and A. tenerrima were identified as sister taxa, whereas the accessions of A. kotschyi and A. ruprechtii were always intermingled.

Estimating divergence times

In BEAST analyses using the ITS data, the most recent common ancestor of the A. sylvestris complex was estimated to live 1.13 million years ago (Ma), with a 95% highest posterior density (HPD) interval ranging from 1.86 to 0.56 Ma (Fig. 6). It is noteworthy that the ribotype groups Nit and Syl were sisters, rather than the latter being nested within the former (compare with Fig. S1). However, both clades received a very low PP support: 0.36 and 0.72 for monophyly of Syl and Nit, respectively. The Nit group began to diversify approximately 0.40 Ma, whereas the initial split in the Syl group occurred at 0.89 Ma.

Chronogram obtained with BEAST from ITS data constraining the root of the tree, i.e. specifying Kozlovia and Anthriscus to be each monophyletic. The root was assumed to have a normal distribution with a mean of 8.792265616 and a standard deviation of 1.158792094, based on the analyses of Banasiak, et al. 10. For simplicity, Kozlovia was omitted. Horizontal bars denote 95% HPD intervals; PP values (> 0.5) are provided along branches. Ribogroups are the same as in Fig. 2.

The estimated crown age of the A. sylvestris complex, based on the plastid data (Fig. 7), was 1.72 Ma (95% HPD: 2.58–0.93 Ma), which is earlier than the estimate based on ITS data, but the 95% HPD intervals obtained for both datasets largely overlapped. The topology of the tree was also distinct: all plastid haplogroups were identified as clades (compare with Figs. 5 and S3). The L haplogroup was determined to be sister to the F + E clades. The divergence within the European group began approximately 0.44 Ma (95% HPD: 0.72–0.20 Ma).

Chronogram obtained with BEAST from concatenated plastid rpoB–trnC, trnS–trnG, and these psbA–trnH spacers with the constraint on the root of the tree, i.e. specifying Kozlovia and Anthriscus to be each monophyletic. The root was assumed to have a normal distribution with a mean of 8.792265616 and a standard deviation of 1.158792094, based on the analyses of Banasiak, et al. 10. For simplicity, Kozlovia was omitted. Horizontal bars denote 95% HPD intervals; PP values (> 0.5) are provided along branches. Plastid haplogroups are the same as in Figs. 3 and 5.

Fruit indumentum, geography and molecular phylogeny

A major morphological character used in the taxonomy of Anthriscus sylvestris s.l. is fruit indumentum. Fruits are devoid of hairs in A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris and subsp. alpina, A. nitida, A. schmalhausenii, and A. lamprocarpa. Conversely, they are adorned with tuberculate bristles in A. sylvestris subsp. nemorosa and subsp. fumarioides (Fig. 1). This distinction displays a marked geographical pattern: tuberculate/bristled fruits are predominantly found in the Balkans, the southern region of the Apennine Peninsula, Asia Minor, and the Himalayas. They are sporadically encountered in eastern Asia and tropical East Africa along with the glabrous-fruited morphotype. Glabrous fruits are present in all accessions from North Africa as well as central and western Europe. This distribution pattern does not align with any of the molecular markers investigated. Notably, both glabrous and tuberculate-fruited specimens exist within the E, A, and L plastid haplogroups (e.g., Figs. 5 and 7). Similarly, the Nit and Syl ribotype groups each encompass both morphotypes. To illustrate, the representatives of tuberculate-fruited A. s. subsp. nemorosa from the Peloponnese possess the Nit ribotype, whereas their morphologically identical counterparts from southern Italy bear the Syl ribotype.

Discussion

Taxonomy versus molecular trees

While each molecular marker analyzed in this study displays specific biogeographical or ecological patterns, these patterns do not align with morphological markers such as leaf architecture and fruit indumentum. As a result, they also diverge from the current taxonomy of the genus.

Plastid data suggest a western Asian origin for Anthriscus and its sect. Cacosciadium. This agrees with previous results10 reconstructing Mediterranean or Irano-Turanian ancestral areas for most core apioid clades (or tribes). Interestingly, pollen microfossils that may be attributed to the euapioid clade (including subtribe Scandicinae that encompasses Anthriscus) were recovered from Oligo-Miocene sediments of eastern Anatolia44 thus supporting the aforementioned scenario. The split between Central Asian Kozlovia and western Eurasian Anthriscus, taken in this study as secondary calibration point, was estimated to have occurred in the upper Miocene, c. 9 Ma 10, an epoch characterized by a slowly drying climate that might have spurred vicariance events3. However, the major diversification trigger was most probably the onset of the Pleistocene glaciations. An exemplary pair of sister species originating during the Ice Age is Anthriscus tenerrima and A. caucalis. The former is restricted to the eastern Mediterranean (Greece and western Turkey), while the latter is now a common weed spreading due to its small fruits covered by tuberculate bristles11. In Spain and south-western France, A. caucalis is also represented by a glabrous-fruited variety. Interestingly, a similar polymorphism—the presence of plants with glabrous fruits and with tuberculate fruits within the same population—is characteristic of A. tenerrima.

Such polymorphism in annual umbellifers, often expressed within a single plant as heterocarpy, likely reflects alternative dispersal strategies: glabrous fruits are dispersed by gravity, facilitating local population renewal, while bristled fruits are dispersed on animal fur over greater distances45. The ancestor of A. caucalis and A. tenerrima might have been polymorphic with respect to fruit indumentum12. This polymorphism was inherited by the descendant species, which originated due to a vicariance event, surviving the Ice Age in two major refugia: the Pyrenean Peninsula and the Balkan Peninsula/Asia Minor. The bristled-fruited variety of A. caucalis spread with human activity and has become a noxious weed, while its glabrous-fruited variety remained in the refugial area.

Molecular data included in this study do not support the present taxonomic treatment of the sect. Cacosciadium, as all taxa, regardless of their rank, are nested within the geographically widespread A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris. However, it is important to remember that gene trees do not always reflect species trees, particularly in cases of recent speciation with incomplete lineage sorting46. Peripatric and sympatric speciation events practically always result in one species being nested within another in a phylogenetic tree. Interspecific phylogenies, geographical ranges, and adaptive shifts are often used to infer geographical modes of speciation albeit there are some caveats of such inferences46. In the revision of Anthriscus based on morphological data only, A. nemorosa and A. fumarioides were reduced to the rank of subspecies of A. sylvestris, while A. nitida, A. lamprocarpa, and A. schmalhausenii were maintained as distinct species due to their morphological and ecological disparity with A. sylvestris11,12.

Anthriscus nitida is sympatric with A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris throughout its range, but these two taxa significantly differ in habitat preferences. The former occurs in the mountainous beech-fir forest belt, while the latter inhabits rich and moist anthropogenic habitats such as road verges, meadows, and forest margins11. Substantial range overlap and adaptive shifts are often regarded as hallmarks of sympatric speciation, but such an interpretation may be overreaching because range overlap may be secondary while adaptive shifts often accompany ‘standard’ vicariant speciation46. Although lowland riparian forests were hypothesized to be the primary habitats of A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris11,12, this taxon occurs almost exclusively in secondary anthropogenic habitats in Central Europe, hence its wide geographical range may be quite recent and related to human activities. In contrast, the range of A. nitida is similar to that of other species inhabiting mountainous beech-fir forests, particularly Abies alba7. It is possible that A. nitida originated in the late Pleistocene in one of the southern refugia of beech-fir forests, particularly in the Balkans. Its speciation would be, therefore, allopatric rather than sympatric. However, the delimitation of A. nitida is contentious as discussed later in this paper.

Anthriscus lamprocarpa differs from its parapatric cousin A. sylvestris subsp. nemorosa in having a biennial habit and straw-yellow glabrous fruits, in contrast to the perennial lifespan and brown/black tuberculate fruits of the latter11. However, two intermediate populations from southern Turkey have been identified and described as A. lamprocarpa subsp. chelikii47. This taxon might be of hybrid origin; alternatively, A. sylvestris subsp. nemorosa, A. lamprocarpa subsp. cheliki, and A. lamprocarpa subsp. lamprocarpa could represent clinal variation since fruit indumentum, color, and cuticle are under strong selection pressure, particularly related to fruit dispersal48,49 and avoidance of seed predation50. Hairy, bristled, or spiny versus glabrous fruits are known in many species of umbellifers and usually regarded as adaptations to dispersal on animal fur or by gravity45,51. However, the narrow, beaked mericarps of A. sylvestris, even without any specialized appendages, have quite good attachment potential to animal fur, for example of wild boar and sheep52.

Seed color may represent an adaptive response to fruit predation. In the legume species Acmispon wrangelianus, which is polymorphic with respect to seed color, the latter appears to match the soil color53. Anthriscus lamprocarpa inhabits warmer and dryer habitats than A. sylvestris subsp. nemorosa, so its straw-colored fruits may better camouflage among dried remnants of plants, whereas the brownish fruits of the latter may be less visible on more moist, brownish soil. Interestingly, A. lamprocarpa is morphologically similar to North African populations of A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris, sometimes recognized as A. sylvestris subsp. mollis (Boiss. & Reut.) Maire, with the former suggested to descend from the latter through peripatric speciation12. However, our results indicate that A. lamprocarpa is of Anatolian rather than North African origin, while African ‘subsp. mollis’ may be its descendant rather than the ancestor.

Anthriscus schmalhausenii was initially described in the genus Chaerophyllum based on its sparsely divided leaves with broad lobes resembling those of C. aromaticum. Subsequently, it was reclassified into Anthriscus based on flower and fruit characteristics. Within Anthriscus, it was assigned to sect. Caroides, alongside other Caucasian species, A. kotschyi and A. ruprechtii54. In the most recent treatment of the genus11,12, its similarity to A. nitida in terms of leaf shape and division was noted but interpreted as a case of parallel evolution adapting to shady deciduous forests. Our research situates this taxon within the western and central Asiatic plastid clade (A) and within the Syl ribotype group (we failed to amplify waxy for this taxon). This species is found in Georgia and adjacent regions of Russia (Adygea, Krasnodar Krai), which constituted the Colchis Glacial Refugium – an important sanctuary for forest species.

In conclusion, there is no evidence supporting sympatric speciation in Anthriscus sylvestris s.l. Instead, geographical distance and isolation within glacial refugia appear to have played significant roles as drivers of local differentiation and speciation in this group.

Migration routes around the Mediterranean

The circum-Mediterranean distribution of Anthriscus sylvestris complex raises questions about the migration routes and whether different migration waves have met closing the distribution ring.

Levantine A. lamprocarpa has been speculated to descend from the North African populations of A. sylvestris, the latter originating from the Iberian populations, which would imply that two migration waves met in southern Turkey12, along the Anatolian diagonal55. However, our analyses of plastid data allow to refute this hypothesis and suggest two alternative scenarios. In maximum likelihood plastid DNA tree, the European accessions (E) form a clade nested in North African polytomy (F), which is nested in Middle Eastern L grade. Such a topology suggests that the migration of the A. sylvestris complex from Middle East to Europe did not occur across the Turkish Straits, but around the Mediterranean: through northern Africa to the Iberian Peninsula and then eastwards to the Balkans, the area of possible secondary contact with the L lineage. The presence of tuberculate fruits in the Balkans and southern Italy—a character that is common in Asiatic populations while being absent in western Europe—suggests subsequent gene flow from Asia to the Balkans. We are not aware of any other plant taxon with such a dispersal pattern around the Mediterranean, although floristic links between SW Asia and NW Africa have already been postulated56. Moreover, such a scenario has interesting implications for the biogeography of the Mediterranean, because it entails the existence of a barrier between Asia Minor and the Balkans, whereas, throughout the Pleistocene, these areas were connected by land bridges57.

However, the biogeographic scenario suggesting migration around the Mediterranean does not receive strong support. According to BEAST analyses, the Levantine (L) and North African (F) groups form clades rather than grades. Such a topology indicates an alternative scenario involving a series of vicariance events, with a common ancestor initially widespread across Asia Minor, North Africa, and Europe. Subsequently, this ancestor became fragmented into three distinct groups—L, F, and E—due to the geographic barriers of the Turkish Straits and the Strait of Gibraltar. The western L + F + E group was isolated from the eastern group, which combined Western and Central Asia (A) and the Far Eastern (C) clades, by the Anatolian diagonal58.

Reticulate evolution in the Anthriscus sylvestris complex

There are three primary sources of genetic variation that underlie adaptive ecological niche shifts: pre-existing diversity, the accumulation of new mutations, and the acquisition of beneficial alleles from other lineages. Studies that quantify the relative importance of these sources are scarce. While some studies point to one major source of variation, namely standing variation59, others demonstrate the input of all three sources60. It has been argued that the advantage of introgression or reticulate evolution is not merely the admixture of beneficial alleles but most of all the reassembly of old genetic variants into novel combinations16. This “combinatorial” mechanism might not only facilitate rapid speciation but also adaptive radiation and sympatric speciation, and it might contribute to variation in speciation rates among lineages. Among angiosperms, events of reticulation in the evolution and speciation of many taxa have been ascertained; however, the contribution of admixture variation has rarely been evaluated60,61. We hypothesize that this mechanism was involved in the ecological diversification of Anthriscus sylvestris complex in Europe.

The incongruence between plastid and nuclear markers, as well as morphological traits such as fruit indumentum, particularly in the Balkans and Central Europe, suggests significant gene flow of possibly adaptive character. The most striking discovery is that, based on ITS variation, Dalmatian mountainous A. sylvestris subsp. fumarioides and Balkan representatives of subsp. nemorosa, both having tuberculate fruits, are not related to the specimens of subsp. nemorosa from Turkey, but rather to the glabrous-fruited A. nitida from the Balkans and the Carpathians (ribotype Nit). Surprisingly, mountainous A. sylvestris subsp. alpina and A. nitida from France have ribotype Syl, which is characteristic of lowland A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris. The border between these ribotypes seems to align with the border between the Carpathians and the Sudeten Mountains, with Carpathian specimens of A. nitida having type Nit, whereas nitida-like plants from the Sudeten Mountains have type Syl.

The difference in leaf form between A. sylvestris and A. nitida follows a well-established pattern: leaves of plants of shady and moist habitats tend to be broader and less divided than those of plants inhabiting dryer and more open habitats62,63. It is therefore possible that “true” A. nitida comprises only plants from the Carpathians and the Balkans, while nitida-like forms from the Sudeten and the Alps evolved from A. sylvestris with the influx of adaptive genes from A. nitida. This influx is also suggested by the distribution pattern of waxy alleles: representatives of western A. nitida and A. sylvestris subsp. alpina have waxy alleles closely related to those in eastern A. nitida and A. sylvestris subsp. fumarioides while maintaining the Syl ribotype of lowland A. sylvestris subsp. sylvestris.

Our data suggest that the ecological diversity in the A. sylvestris complex is relatively recent. The ancestor of the European lineage likely immigrated to Europe approximately 0.44 Mya, prior to the Elster glaciation. Its history in Europe may have been similar to that of other European taxa, involving successive retreats to glacial refugia, divergent evolution in these refugia, followed by re-colonization and secondary contacts among previously isolated populations. For example, intensive reticulate evolution in glacial refugia has been documented for European oaks 64, while the Alpine lake whitefish species complex likely arose from a hybrid swarm of at least two glacial refugial lineages65.

A comprehensive evaluation of the reticulate evolution hypothesis in the A. sylvestris complex requires genome-wide study, which is currently underway.

Conclusions

The current study offers significant insights into the taxonomy, speciation, and biogeography of Anthriscus sylvestris complex. Contrary to the notion of sympatric speciation in Central Europe, our findings do not reject the hypothesis that geographical isolation within glacial refugia was the dominant driver for differentiation within this group.

Plastid data corroborate previous suggestions of a western Asiatic origin for Anthriscus and its section Cacosciadium. Within the latter, the plastid data challenge the present taxonomic treatment as plastid haplotypes align with the geographic distribution of the samples rather than their taxonomy. Plastid trees suggest two alternative biogeographic scenarios. The first, and better supported, implies a migration around the Mediterranean. The second postulates a series of vicariance events resulting from geographical barriers that arose during the Ice Age. Both scenarios suggest that the Balkans were the place of secondary contact between long-isolated lineages. In contrast, nuclear data appear to divide into lowland and montane alleles, but the support for this pattern is not particularly strong.

Considering the molecular, ecological, and biogeographic data, it is evident that the diversification of A. sylvestris s.l. is a complex interplay of geographical, climatic, and ecological factors, as well as shaped by gene flow between previously isolated lineages. Future studies may benefit from expanded molecular datasets, coupled with detailed ecological and morphological analyses, to provide a clearer understanding of the evolutionary history of this taxon.

Data availability

All sequences are deposited in GenBank: voucher data and accession numbers are given in Table S1. Sequence matrices and trees are deposited in the University of Warsaw repository danebadawcze.uw.edu.pl. DOI: 10.58132/WACYXJ.

References

Prista, G. A., Agostinho, R. J. & Cachão, M. A. Observing the past to better understand the future: a synthesis of the Neogene climate in Europe and its perspectives on present climate change. Open Geosci. 7, 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1515/geo-2015-0007 (2015).

Barrón, E. et al. The Cenozoic vegetation of the Iberian Peninsula: a synthesis. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 162, 382–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2009.11.007 (2010).

Vargas, P., Fernández-Mazuecos, M. & Heleno, R. Phylogenetic evidence for a Miocene origin of Mediterranean lineages: species diversity, reproductive traits and geographical isolation. Plant Biol. 20, 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.12626 (2018).

Fiz-Palacios, O. & Valcárcel, V. From Messinian crisis to Mediterranean climate: a temporal gap of diversification recovered from multiple plant phylogenies. Perspect. Pl. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 15, 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2013.02.002 (2013).

Nieto Feliner, G. Patterns and processes in plant phylogeography in the Mediterranean Basin. A review. Perspect. Pl. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 16, 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2014.07.002 (2014).

Surina, B., Pfanzelt, S., Einzmann, H. J. R. & Albach, D. C. Bridging the Alps and the Middle East: evolution, phylogeny and systematics of the genus Wulfenia (Plantaginaceae). Taxon 63, 843–858. https://doi.org/10.12705/634.18 (2014).

Linares, J. C. Biogeography and evolution of Abies (Pinaceae) in the Mediterranean Basin: the roles of long-term climatic change and glacial refugia. J. Biogeogr. 38, 619–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02458.x (2011).

Vargas, P. Molecular evidence for multiple diversification patterns of alpine plants in Mediterranean Europe. Taxon 52, 463–476. https://doi.org/10.2307/3647383 (2003).

Plunkett, G. M. et al. Flowering plants Eudicots. In The families and genera of vascular plants (eds Kadereit, J. W. & Bittrich, V.) (Springer, 2018).

Banasiak, Ł et al. Dispersal patterns in space and time: a case study of Apiaceae subfamily Apioideae. J. Biogeogr. 40, 1324–1335. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12071 (2013).

Spalik, K. Revision of Anthriscus (Apiaceae). Polish Bot. Stud. 13, 1–69 (1997).

Spalik, K. Species boundaries, phylogenetic relationships, and ecological differentiation in Anthriscus (Apiaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 199, 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00985915 (1996).

Tekin, M. & Civelek, Ş. A taxonomic revision of the genus Anthriscus (Apiaceae) in Turkey. Phytotaxa 302, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.302.1.1 (2017).

Downie, S. R., Katz-Downie, D. S. & Spalik, K. A phylogeny of Apiaceae tribe Scandiceae: evidence from nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer sequences. Amer. J. Bot. 87, 76–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/2656687 (2000).

Hruška, K. Considerazioni ecologiche, fitosociologiche e morfologiche sul genere Anthriscus Pers. G. Bot. Ital. 116, 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/11263508209428063 (1982).

Marques, D. A., Meier, J. I. & Seehausen, O. A combinatorial view on speciation and adaptive radiation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 34, 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.02.008 (2019).

Downie, S. R., Spalik, K., Katz-Downie, D. S. & Reduron, J.-P. Major clades within Apiaceae subfamily Apioideae as inferred by phylogenetic analysis of nrDNA ITS sequences. Plant Div. Evol. 128, 111–136. https://doi.org/10.1127/1869-6155/2010/0128-0005 (2010).

Chung, K.-F., Peng, C.-I., Downie, S. R., Spalik, K. & Schaal, B. A. Molecular systematics of the trans-pacific alpine genus Oreomyrrhis (Apiaceae)–phylogenetic affinities and biogeographic implications. Amer. J. Bot. 92, 2054–2071. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.92.12.2054 (2005).

Piwczyński, M., Puchałka, R. & Spalik, K. The infrageneric taxonomy of Chaerophyllum (Apiaceae) revisited: new evidence from nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS sequences and fruit anatomy. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 178, 298–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/boj.12282 (2015).

Levin, R. A., Blanton, J. & Miller, J. S. Phylogenetic utility of nuclear nitrate reductase: a multi-locus comparison of nuclear and chloroplast sequence data for inference of relationships among American Lycieae (Solanaceae). Molec. Phylogen. Evol. 50, 608–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2008.12.005 (2009).

Shaw, J. et al. The tortoise and the hare II: relative utility of 21 noncoding chloroplast DNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Amer. J. Bot. 92, 142–166. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.92.1.142 (2005).

Shaw, J. et al. Chloroplast DNA sequence utility for the lowest phylogenetic and phylogeographic inferences in angiosperms: The tortoise and the hare IV. Amer. J. Bot. 101, 1987–2004. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1400398 (2014).

Chung, K.-F. Inclusion of the South Pacific alpine genus Oreomyrrhis (Apiaceae) in Chaerophyllum based on nuclear and chloroplast DNA sequences. Syst. Bot. 32, 671–681. https://doi.org/10.1600/036364407782250517 (2007).

Panahi, M. et al. Taxonomy of the traditional medicinal plant genus Ferula (Apiaceae) is confounded by incongruence between nuclear rDNA and plastid DNA. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 188, 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1093/botlinnean/boy055 (2018).

Degtjareva, G. V., Logacheva, M. D., Samigullin, T. H., Terentieva, E. I. & Valiejo-Roman, C. M. Organization of chloroplast psbA-trnH intergenic spacer in dicotyledonous angiosperms of the family Umbelliferae. Biochem. Mosc. 77, 1056–1064. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0006297912090131 (2012).

inferences from ITS sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Wen, J. & Zimmer, E. A. Phylogeny and biogeography of Panax L. (the ginseng genus, Araliaceae). Molec. Phylogen. Evol. 6, 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1006/mpev.1996.0069 (1996).

Spalik, K. & Downie, S. R. The evolutionary history of Sium sensu lato (Apiaceae): dispersal, vicariance, and domestication as inferred from ITS rDNA phylogeny. Amer. J. Bot. 93, 747–761. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.93.5.747 (2006).

Lasergene v. 8 (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison (WI), USA, 2009). https://www.dnastar.com

Tank, D. C. & Olmstead, R. G. The evolutionary origin of a second radiation of annual Castilleja (Orobanchaceae) species in South America: the role of long distance dispersal and allopolyploidy. Amer. J. Bot. 96, 1907–1921. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.0800416 (2009).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst010 (2013).

Maddison, W. P. & Maddison, D. R. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 3.70., http://www.mesquiteproject.org (2021).

Larsson, A. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large data sets. Bioinformatics 30, 3276–3278. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu531 (2014).

Degtjareva, G. V., Kljuykov, E. V., Samigulin, T. H., Valiejo-Roman, C. M. & Pimenov, M. G. ITS phylogeny of Middle Asian geophilic Umbelliferae-Apioideae genera with comments on their morphology and utility of psbA-trnH sequences. Plant Syst. Evol. 299, 985–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00606-013-0779-9 (2013).

Leigh, J. W., Susko, E., Baumgartner, M. & Roger, A. J. Testing congruence in phylogenomic analysis. Syst. Biol. 57, 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150801910436 (2008).

Templeton, A. R., Crandall, K. A. & Sing, C. F. A cladistic analysis of phenotypic associations with haplotypes inferred from restriction endonuclease mapping and DNA sequence data. III. Cladogram Estimation. Genetics 132, 619–633. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/132.2.619 (1992).

Leigh, J. W. & Bryant, D. POPART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6, 1110–1116. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.12410 (2015).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 (2014).

Lanfear, R., Frandsen, P. B., Wright, A. M., Senfeld, T. & Calcott, B. PartitionFinder 2: new methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 772–773. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw260 (2017).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/sys02 (2012).

Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J., Xie, D., Baele, G. & Suchard, M. A. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 67, 901–904. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syy032 (2018).

Suchard, M. A. et al. Bayesian phylogenetic and phylodynamic data integration using BEAST 1.10. Virus Evolution https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vey016 (2018).

Wieczorek, C. & Wieczorek, J. Georeferencing Calculator, http://georeferencing.org/georefcalculator/gc.html (2021).

ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10 v. 10.8.2 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands (CA), USA, 1995–2021). www.esri.com

Sancay, R. H. N., Bati, Z., Işik, U., Kirici, S. & Akça, N. Palynomorph, Foraminifera, and calcareous nannoplankton biostratigraphy of Oligo-Miocene sediments in the Muş basin, eastern Anatolia. Turkey. Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences 15, 259–319 (2006).

Wojewódzka, A. et al. Evolutionary shifts in fruit dispersal syndromes in Apiaceae tribe Scandiceae. Plant Syst. Evol. 305, 401–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00606-019-01579-1 (2019).

Losos, J. B. & Glor, R. E. Phylogenetic comparative methods and the geography of speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(03)00037-5 (2003).

Tekin, M. & Civelek, Ş. Anthriscus lamprocarpa subsp. chelikii (Apiaceae), a new subspecies from southern Turkey. Phytotaxa 253, 275–284. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.253.4.3 (2016).

Tackenberg, O., Poschlod, P. & Bonn, S. Assessment of wind dispersal potential in plant species. Ecol. Monogr. 73, 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9615(2003)073[0191:AOWDPI]2.0.CO;2 (2003).

Tackenberg, O., Römermann, C., Thompson, K. & Poschlod, P. What does diaspore morphology tell us about external animal dispersal? Evidence from standardized experiments measuring seed retention on animal-coats. Basic Appl. Ecol. 7, 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2005.05.001 (2006).

Niu, Y., Sun, H. & Stevens, M. Plant camouflage: ecology, evolution, and implications. Trends Ecol. Evol. 33, 608–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2018.05.010 (2018).

Spalik, K., Wojewódzka, A. & Downie, S. R. The evolution of fruit in Scandiceae subtribe Scandicinae (Apiaceae). Canad. J. Bot. 79, 1358–1374. https://doi.org/10.1139/b01-116 (2001).

Couvreur, M., Vandenberghe, B., Verheyen, K. & Hermy, M. An experimental assessment of seed adhesivity on animal furs. Seed Sci. Res. 14, 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1079/SSR2004164 (2004).

Porter, S. S. Adaptive divergence in seed color camouflage in contrasting soil environments. New Phytol. 197, 1311–1320. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12110 (2013).

Schischkin, B. K. Flora SSSR (Izdatelstvo Akademii Nauk, 1950).

Sancar, P. Y., Civelek, Ş, Tekin, M. & Daştan, S. D. Investigation of the genetic structures and phylogenetic relationships for the species of the genus Anthriscus Pers (Apiaceae) distributed in Turkey, by use of the non-coding “trn” regions of the chloroplast genome. Pak. J. Bot. 51, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.30848/pjb2019-3(37) (2019).

Davis, P. H. & Hedge, I. C. Floristic links between NW Africa and SW Asia. Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien 75, 43–57 (1971).

Sakellariou, D. & Galanidou, N. Pleistocene submerged landscapes and Palaeolithic archaeology in the tectonically active Aegean region. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 411, 145–178. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP411.9 (2016).

Ekim, T. & Güner, A. The anatolian diagonal: fact or fiction?. Proc. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh, B Biol. Sci. 89, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0269727000008915 (2011).

Lai, Y.-T. et al. Standing genetic variation as the predominant source for adaptation of a songbird. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 2152–2157. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813597116 (2019).

Pease, J. B., Haak, D. C., Hahn, M. W. & Moyle, L. C. Phylogenomics reveals three sources of adaptive variation during a rapid radiation. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002379. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002379 (2016).

Wright, K. M., Lloyd, D., Lowry, D. B., Macnair, M. R. & Willis, J. H. Indirect evolution of hybrid lethality due to linkage with selected locus in Mimulus guttatus. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001497. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001497 (2013).

Givnish, T. Topics in Plant Population Biology (Macmillan Education, 1979).

Nicotra, A. B. et al. The evolution and functional significance of leaf shape in the angiosperms. Funct. Plant Biol. 38, 535–552. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP11057 (2011).

Petit, R. J. et al. Identification of refugia and post-glacial colonisation routes of European white oaks based on chloroplast DNA and fossil pollen evidence. Forest Ecol. Managem. 156, 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00634-X (2002).

Hudson, A. G., Vonlanthen, P. & Seehausen, O. Rapid parallel adaptive radiations from a single hybridogenic ancestral population. Proc. R. Soc. Ser. B 278, 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.0925 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank the curators of the herbaria listed in Table S1 for allowing sampling for molecular studies.

Funding

Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, 6PO4C 03921, National Science Centre Poland, 2021/43/B/NZ8/02120

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.K.-M. and K.S. conceived the ideas of the research, all authors collected the plant material, R.K.-M., P.T., M.D.D., M.P, and Ł.B. did the laboratory work, prepared the matrices and did preliminary analyses, Ł.B. and K.S. double-checked the data, M.P. and Ł.B. did the final analyses, K.S. wrote the manuscript, all authors checked the paper and approved it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kurzyna-Młynik, R., Banasiak, Ł., Piwczyński, M. et al. Phylogeographic evidence reveals multiple colonization events and a secondary contact zone in the Balkans for the Anthriscus sylvestris complex (Apiaceae). Sci Rep 15, 31497 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15409-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15409-7