Abstract

Exploring the characteristics of blasting crack propagation under the action of in-situ stress is of great significance for guiding the layout of blast holes on site. This paper proposed a modified calculation method for the range of crushed zone and cracked zone under the action of in-situ stress based on the coupled stress distribution characteristics of in-situ stress and blasting load. A numerical simulation model for single hole blasting was established based on the Holmquist-Johnson–Cook (HJC) model, and the modified method was validated. Meanwhile, the influence of burial depth and lateral pressure coefficient on crack propagation characteristics was analyzed, and the effects of axial loading coefficient, lateral pressure coefficient, dynamic compressive strength, and dynamic tensile strength on the range of crushed zone and cracked zone were studied. It is concluded that the modified theoretical calculation method predicts the crack extension length and direction with high accuracy, and the errors with the numerical simulation results are controlled at 5.5% and 4°, respectively. Under the action of coupled stress field, the crack length in various directions of the blasthole show non-uniform distribution, and the tangent value of the angle between the longest radial main crack and the vertical direction and the lateral pressure coefficient are basically the same. The research results can provide reference for the design of deep rock blasting parameters and the improvement of explosive utilization efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of the worldwide economy, underground space development continues to go deep, and there are more and more deep rock projects1,2,3. With regard to mining, shallow mineral resources are gradually being depleted and mining activities are increasingly taking place in deeper rock masses4,5. For tunnel construction, tunnels often need to pass through mountainous areas with large burial depths6,7,8. Therefore, the deep rock mass is already in a three-dimensional stress state prior to excavation.

Drilling and blasting method has the advantages of economic and efficient, is currently the most commonly used construction methods for highway and railroad tunnels, mine shafts, hard rock excavation in underground space9,10,11,12. In deep rock blasting, the rock mass is subjected to multi-field coupling of in-situ stress and blasting load. However, up to now, the crack extension law of deep rock blasting under the coupled effects of static in-situ stress and dynamic explosive loading has not been thoroughly studied. Modifying the range of crushed zone and crack zone under the coupled effect of multiple stress fields, and exploring the law of crack propagation, is of great significance for improving the energy utilization efficiency of explosives.

In the past decades, researchers have used theoretical analysis, blasting tests, and numerical simulations to study the crack extension law in rock blasting. Ge13 introduced strength discount factors λ1, λ2 in the formula for calculating the radius of the crushed and cracked zones in the no-initial stress state to characterize the effect of in-situ stress on the crushed and cracked zones. However, the values of λ1 and λ2 need to be determined experimentally. Yang et al.14,Wang et al.15,Zhang et al.16 derived computational expressions for the stress distribution under the coupling of in-situ stress and blasting loading and verified them by modeling tests. However, the above studies do not provide a detailed discussion on the method of calculating the range of the crushed and cracked zones under the action of the coupled stress field. In terms of blasting tests, the researchers carried out blasting model tests under different in-situ stress conditions and analyzed the changing law of crack expansion with in-situ stress17,18,19,20. However, these limited experimental studies have not yet explored in depth the crack extension law of rock blasting under the coupling of multiple stress fields due to the constraints of difficult processing and preparation of the blasting test system, high cost, and difficulty in observing the cracks formed after blasting. In numerical simulation, the researchers established numerical analysis models of single-hole and double-hole blasting under different in-situ stress conditions, indicated that the in-situ stress has a dual role of restricting and guiding the crack expansion21,22,23,24.

Based on the superposition principle, this paper analyzed the stress distribution characteristics around the blasthole under the coupled action of in-situ stress and blasting load, and amended the calculation method of the range of crushed zone and cracked zone under the action of coupled stress field. Combined with the numerical simulation method, the numerical analysis model of single-hole blasting was established by using the parameters of the HJC constitutive model, and the numerical analysis results were compared with the theoretical calculation results to verify the accuracy of the model and parameters. In addition, a series of numerical analysis models of single-hole blasting under different burial depths and lateral pressure coefficients were established to analyze the crack extension law of rock blasting under different stress conditions, and the influences of axial charging coefficient, lateral pressure coefficient, dynamic tensile strength, dynamic tensile strength, and reinforcement coefficient m on the pattern of crack extension were discussed. The results of the study can provide a reference for the design of blasting parameters for deep rock masses.

Modification of the calculating method for cracked zone range

Distribution of coupled stress field around the blasthole

Explosive load and in-situ stress coupling action calculation model can be simplified to an infinite flat plate calculation model under the action of two-way unequal pressure load, as shown in Fig. 1. Where σV is the vertical in-situ stress, σH is the horizontal in-situ stress, Pd is the homogeneous force acting on the wall of the hole, and r0 is the radius of the circular hole, which is much smaller than that of the flat plate. To solve this kind of problem, the superposition method of elastoplastic mechanics can be referred to, which is divided into three steps to solve the post-superposition. The first is to solve the stress distribution under unidirectional loading (σV = 0, Pd = 0, σH ≠ 0), the second is to solve the stress distribution under loading in the other direction (σH = 0, Pd = 0, σV ≠ 0), and the third is to solve the explosive load Pd acting at the wall of the blasthole under the condition of no perimeter pressure. By superimposing the above three stress distributions, the stress distribution under the coupled action of blast loading and in-situ stress can be derived.

The expression for the stress distribution under the coupled effect of blast load and in-situ stress is given by:

where r, r0 are the distance from the calculation point to the center of the packet and the radius of the blasthole, respectively, m. θ is the angle between the line between any point in the rock and the center of the blasthole and the horizontal direction, °. Pd is the homogeneous force acting on the blasthole wall, MPa. α is the pressure attenuation coefficient, for the shock wave region α ≈ 3 or α = 2 + μ/(1-μ), the stress wave region β = 2-μ/(1-μ).

Modification of the calculating method for cracked zone range

Treating the blast of a blasthole as a plane strain problem, \(\sigma_{z} = \mu (\sigma_{r} + \sigma_{\theta } ) = \mu (1 - \lambda )\sigma_{r}\). Then the stress intensity at any point in the rock mass can be expressed as25:

where \(A = \left[ {(1 + \lambda )^{2} - 2\mu (1 - \lambda )^{2} (1 - \mu ) + (1 + \lambda^{2} )} \right]^{\frac{1}{2}}\).

According to the Mises criterion, the rock mass fails when σi satisfies Eq. (3).

where σcd and σtd are the dynamic compressive strength and tensile strength of the rock, respectively, MPa.

When α is set to 3, the crushed zone radius RC is calculated by Eq. (1), Eq. (2), and Eq. (3):

Let \(\frac{{r_{0} }}{{R_{C} }} = x\), then Eq. (4) becomes:

where:

Equation (5) can be solved by the MATLAB program, and excluding the limited understanding, the calculation expression of the crushed zone radius RC is obtained:

where:

The cracked zone is outside the crushed zone, and the explosion load continues to propagate outward in the form of stress waves within the cracked zone, and the attenuation coefficient β = 2-μ/(1-μ). According to Eq. (2), at the interface between the crushed zone and the cracked zone26:

Calculating the cracked zone radius RT by Eq. (3), Eq. (7), and Eq. (9)26:

From the above theoretical derivation, it can be found that the in-situ stress has little effect on the crushed zone, and has some inhibition effect on the cracked zone, and the inhibition effect is different in different directions. If the radius of the cracked zone is calculated according to Eq. (10), the radius of the cracked zone is the same in all directions. Therefore, a correction to Eq. (10) is required. The modified expression for the calculation of the radius RT of the cracked zone is:

where m is the coefficient of enhancement of the tensile strength of the rock caused by the in-situ stress27.

The cavity expansion process ends when the shock wave propagates to the crushed zone edge. From the law of mass conservation in the process of shock wave shock cavity expansion, it is concluded that the expansion law of cavity explosion under the action of the shock wave is26:

where r1 is the blast cavity radius corresponding to r, ρm is the original rock density, kg/m3. ρr is the rock density behind the shock wave front at the blast hole wall, \(\rho_{r} = \frac{{(a + bV_{0} )\rho_{m} }}{{a + (b - 1)V_{0} }}\), kg/m3. a and b are the rock test constants, and V0 is the initial velocity of the rock particle at the blast hole wall.

At the edge of the crushed zone (r = RC), the shock wave decays into a stress wave, and the cavity expansion process caused by the shock wave ends. At this time, the blast cavity radius R1 is:

After the end of the shock wave effect, the explosion gas continues to act in the form of quasi-static pressure on the cavity wall, so that the explosion cavity continues to expand. When the pressure P of the explosion gas in the blast cavity is balanced with the ultimate compressive capacity \(\sigma_{cd}\) of the rock mass around the blast cavity wall, the expansion process of the explosion gas ends. When the pressure P of the explosion gas reduced to the surrounding rock pressure equilibrium, the explosion gas thrown to break the rock. When the expansion gas expands the blast cavity, the expansion law in the blast cavity is26:

where r2 is the instantaneous blast cavity radius corresponding to P, mm. Pk is the critical pressure, MPa.

When \(\sigma_{cd} = P\), the calculation expression of the final radius R2 of the blast cavity can be obtained:

Determination of the enhancement factor m

To determine the value of the enhancement factor m, the infinite flat plate computational model under bi-directional unequal compressive loads of Fig. 1 is further simplified into an external load model and an internal load model as shown in Fig. 2. Due to the small effect of in-situ stress on the range of the crushed zone after blasting of the blastholes, the microelement points on the same radius of the middle zone of the blast are taken here for analysis. The exterior of the model is subjected to vertical stress σV and horizontal stress σH, and the interior microelement points of the model are subjected to radial stress P and circumferential stress Pt.

According to Dai et al.28, the initial static load on the rock mass actually increases the dynamic compressive or tensile strength of the rock mass indirectly. It is assumed that when the microelement point is compressed by a concentrated load (σVa) in the vertical direction, the dynamic tensile strength of the rock in that direction is enhanced by 100%, i.e., the dynamic tensile strength in that direction becomes 2σtd.

Due to the symmetry of the model, half of the rock force model in Fig. 2 was taken for analysis. Taking the parameters of the study section of the right width of the Gonghe Village Tunnel on the Ludian-Qiaojia Expressway in Yunnan Province as an example, the lithology of the study section is dominated by gray sandstone. The density of gray sandstone was measured to be 2560 kg/m3 by test, and the static Poisson’s ratio was 0.37. The dynamic Poisson’s ratio and lateral pressure coefficient were calculated to be 0.296 and 0.42, respectively. At a burial depth of 600 m, σV = 15.36 MPa = 2.38 σ and σH = 6.45 MPa = σ. Assuming that the model side length is a, the rock force model of Fig. 2 can be further simplified to the force analysis model of Fig. 3(a). For the force analysis of the microelement points (A1 ~ A7), the translational concentrated load with additional bending moment can be used, as shown in Fig. 3(b) to Fig. 3(h). Since the initial in-situ stresses σV and σH are much smaller than the dynamic compressive strength of the rock, the additional bending moment generated by the translational concentrated load, although it will produce shear stress, is not enough to produce destructive effect on the rock mass, so the shear effect brought about by the additional bending moment on the interior of the rock mass is not considered here.

From Fig. 3(b) to Fig. 3(h), it can be seen that the microelement points A1 ~ A7 are subjected to external loads in both vertical and horizontal directions, with the magnitudes of 2.38 σa and σa, respectively, which shows that the dynamic tensile strengths of the rock mass are strengthened accordingly, but the degree of enhancement is not the same. The force analysis of the rock microelement points under blast loading is shown in Fig. 427.

Outside the crushing zone, the blast shock wave decays into a blast stress wave, which is no longer sufficient to crush the rock. Therefore, only the tensile stress breaking law is discussed. Let θ1 be the angle between the radial crack and the vertical direction, and the angles θ1 between the microelement points A1 ~ A7 and the line connecting point O and the vertical direction are 0°, 15°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 75°, and 90°, respectively. Regarding θ1 and θ, their relationship is θ1 = 90°—θ. From the force analysis of the microelement points in Fig. 4, it can be seen that the tensile stress suffered by each microelement point is (σVsinθ1-σHcosθ1). Cracks are most likely to expand when the dynamic tensile strength of the rock is not enhanced, i.e., the crack length is longest when θ1 = arctan(σH/σV) = arctanλ. At a burial depth of 600 m, σV = 15.36 MPa = 2.38 σ and σH = 6.45 MPa = σ, then the crack length is the longest when θ1 = 23°. The detailed force analysis of each micrometric point is given below: When θ1 = 23°, the dynamic tensile strength of the microelement point in the tangential direction of the blasthole is σtd, and tensile damage of the rock mass occurs when the circumferential stress is greater than σtd. The microelement point A1 is subjected to an external load σa in the horizontal direction, so its dynamic tensile strength in the horizontal direction becomes 2 σtd, and when \(P_{t}^{A1}> 2\sigma_{td}\), the rock body produces tensile damage. The microelement point A2 is subjected to an external load of 0.35 σa in the tangential direction of the blasthole, so its dynamic tensile strength in the tangential direction of the blasthole becomes 1.35 σtd, and the rock mass produces tensile damage when \(P_{t}^{A2}> 1.35\sigma_{td}\). The microelement point A3 is subjected to an external load of 0.32 σa in the tangential direction of the blasthole, so its dynamic tensile strength in the tangential direction of the blasthole becomes 1.32 σtd, and the rock mass produces tensile damage when \(P_{t}^{A3}> 1.32\sigma_{td}\). The microelement point A4 is subjected to an external load of 0.98 σa in the tangential direction of the blasthole, so its dynamic tensile strength in the tangential direction of the blasthole becomes 1.98 σtd, and the rock body produces tensile damage when \(P_{t}^{A4}> 1.98\sigma_{td}\). The microelement point A5 is subjected to an external load of 1.56 σa in the tangential direction of the blasthole, so its dynamic tensile strength in the tangential direction of the blasthole becomes 2.56 σtd, and the rock mass produces tensile damage when \(P_{t}^{A5}> 2.56\sigma_{td}\). The microelement point A is subjected to an external load of 2.04 σa in the tangential direction of the blasthole, so its dynamic tensile strength in the tangential direction of the blasthole becomes 3.04 σtd, and the rock mass produces tensile damage when \(P_{t}^{A6}> 3.04\sigma_{td}\). The microelement point A7 is subjected to an external load of 2.38 σa in the vertical direction, so its dynamic tensile strength in the vertical direction becomes 3.38 σtd, and the rock body produces tensile damage when \(P_{t}^{A7}> 3.38\sigma_{td}\).

As a result, the crack length in each direction has the following pattern: the crack length in the θ1 = 23° direction is the longest, OA3 > OA2 > OA4 > OA1 > OA5 > OA6 > OA7. Because of the symmetry of the model, the crack extension in every other direction has a similar pattern. From the above analysis, it can be seen that although the in-situ stress has a small effect on the range of the crushed zone after the blast of the blasthole, it has a large effect on the crack extension pattern in different orientations within the cracked zone. As a result, the range of the cracked zone varies in different orientations of the blasthole, i.e., the cracked zones are not circularly distributed.

The dynamic tensile strength of the rock mass in the 0°, 15°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 67°, 75°, and 90° directions of the blasthole is 3.38, 3.04, 2.56, 1.98, 1.32, 1, 1.35, and 2.00 times σtd, respectively, as shown by the force analysis of the microelement points. Therefore, the values of enhancement factor m in Eq. (11) in the directions of 0°, 15°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 67°, 75°, and 90° of the blasthole are 3.38, 3.04, 2.56, 1.98, 1.32, 1, 1.35, and 2.00, respectively.

It can be seen that the in-situ stress has a certain inhibitory effect on the crushed zone and cracked zone. The larger the in-situ stress, the more significant the inhibitory effect is, and the inhibitory effect in different directions is different. Figure 5(a) shows the distribution map of the crushed zone and the cracked zone ignoring the influence of in-situ stress, and Fig. 5(b) shows the distribution of the crushed zone and the cracked zone under the coupling action of in-situ stress and explosion load. The basic mechanical parameters of gray sandstone are shown in Table 1.

Material models for numerical simulations

Rock material model and parameter

The rock material model is based on the HJC (Holmquist-Johnson–Cook) eigenstructure model. The HJC constitutive model is a rate-dependent constitutive model proposed by Holmquist, Johnson, and Cook to solve the problem of the large deformation of concrete under a high strain rate and a high pressure load29, and is widely used in the dynamic analysis of rock materials. The basic mechanical parameters R0 is taken as 2560 kg/m3, fc takes 109.33 MPa, \(G = E/2\left( {1 + \mu } \right) = 2.53GPa\), \(K = E/3\left( {1 - 2\mu } \right) = 5.36GPa\), and T takes 2.18 MPa. Starting from the characterized tensile strength \(T^{*} = T/f_{c}\), make a straight line passing through the data points of equivalent strengths under different strain rates, respectively, and make a straight line perpendicular to the transverse axis at the constant characterized hydrostatic pressure P* = 1/3, and the intersections with the straight lines with different slopes indicate the characterized equivalent stresses of gray sandstone under different strain rates. Fitting the data points from the linear equation to characterize the equivalent stresses at different strain rates resulted in a strain rate influence coefficient C = 0.0046, as shown in Fig. 6.

Based on the results of triaxial compression test of gray sandstone, the cohesive force c is 30.08 MPa. Characterizing the cohesive strength A = c/(1 + Cln10–4)fc and substituting the value of the strain rate influence coefficient C gives A = 0.287. According to \(\sigma^{*} = {{\left( {\sigma_{1} - \sigma_{3} } \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {\sigma_{1} - \sigma_{3} } \right)} {f_{c} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {f_{c} }}\) and \(p^{*} = {{\left( {2\sigma_{1} + \sigma_{3} } \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {2\sigma_{1} + \sigma_{3} } \right)} {3f_{c} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {3f_{c} }}\), \(\sigma^{*} - P^{*}\) curves are drawn, and the fitting can be obtained such that the values of parameters B and N are 0.843 and 0.398, respectively. SFMAX and EPSO are 20.0 and 1.0e-11 according to the literature30. For the damage parameters, \(D_{1} = 0.01/(1/6 + T^{*} ) = 0.05\) and D2 takes a constant value of 1.0. EFMIN and FS are taken as 0.01 and 0.035, respectively. The pressure parameter Pc = fc/3 = 109.33/3 = 36.44 MPa, μc = Pc/K = 6.79 × 10–3, \(\mu_{l}\) is taken as 0.1328. The parameters Pl, K1, K2, and K3 are non-sensitive parameters, and the research results of this paper refer to the literature30 for their values. The parameters of the HJC constitutive model for gray sandstone are shown in Table 2.

Other material models and parameters

The explosive material model uses material model 008 *MAT_HIGH_EXPLOSIVE_BURN, the air material model uses material model 009 *MAT_NULL, and the gun clay material model uses material model 005 *MAT_SOIL_AND_FOAM. The parameters of each model are shown in Table 3,4,5.

Model and parameter validation

In order to verify the reasonableness of the model and material parameter values, a single-hole blasting model without the effect of in-situ stress is established. The radius of the blasthole was 25 mm, and the radius of the medicine roll was 16 mm. The blasting model test results of Ge13 show that under the action of bidirectional unequal pressure load, the longest main crack length is about 25.6 times the radius of the blasthole. This paper set the size of the numerical simulation model to 2 m × 2 m × 1 cm (X × Y × Z), the range of extension of the longest main crack is about 40 times the radius of the blasthole in the X and Y directions, which meets the requirements. After the model calculation, the pressure time profile of the blasthole wall is shown in Fig. 7(a) (Since the keyword *MAT_ADD_EROSION removes the grid, the blasthole wall pressure cannot be measured. Therefore, the keyword *MAT_ADD_EROSION needs to be removed from the model that monitors the time course of the blasthole wall pressure, and the HJC model parameter FS needs to be set to 0). The total number of meshs is 122,880, and the mesh size near the blast hole is 0.8 mm.

When the uncoupled continuous charge is used, the impact stress Pd of the blasthole wall after blasting is :

where \(\rho_{0}\) is the density of the explosive, kg/m3; D is the detonation velocity of the explosive, m/s; γ is the expansion adiabatic exponent of the detonation product, generally taking 3; dc is the diameter of the cartridge, m; db is the diameter of the blasthole, m; lc is the charge length, and lb is the length of the blasthole, m; n is the pressure increase coefficient of the detonation gas impacting the hole wall, generally taking 10.

The impact stress Pd acting on the wall of the blasthole after the explosion of the explosive is calculated as 1878.4 MPa by Eq. (16), and the average peak pressure of the four measurement points on the wall of the blasthole can be seen as 1925.505 MPa by Fig. 7, and the error between the simulation results and the theoretical calculations is controlled at 2.5%. The range of the cracked zone after the model calculations are completed is shown in Fig. 7(b). From Fig. 7(b), it can be seen that under the condition of not applying in-situ stress, the crushed zone and cracked zone after the explosion of explosives are distributed in a circular shape. Measurement of the length of the radial cracks shows that the average radius of the cracked zone is 861.8 mm, and the theoretically calculated radius of the cracked zone is 814.05 mm, and the error between the two is controlled at 5.9%. The results of the above analyses indicate that the present model with the material parameter values are feasible34.

Numerical simulation

Model building

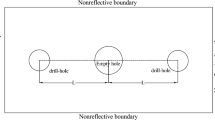

To study the single-hole blasting crack extension law and the range of crushed zone and cracked zone under different burial depths and lateral pressure coefficients, LS-DYNA software was used to establish a numerical analysis model. Assuming that the rock material is homogeneous, the column charge packages are detonated simultaneously. The model size was set to 2 m × 2 m × 1 cm (X × Y × Z), the radius of the blasthole was 25 mm, and the radius of the medicine roll was 16 mm. The in-situ stress σV is applied to the top and bottom faces of the model, and the in-situ stress σH is applied to the left and right faces. Rock materials are defined as solids and explosives and air materials are defined as fluids. The fluid is meshed in a co-nodal fashion and the solid is connected to the fluid by fluid–solid coupling. All faces except the free surface are set as non-reflective boundary conditions. To simulate the process of crack initiation and development, unit failure is controlled by adding the keyword *MAT_ADD_EROSION, setting tensile stress failure and shear strain failure. The simulated working conditions are shown in Table 6.

Analysis of results

After the model calculation is completed, the crack extension of working conditions 2 to 5 is shown in Fig. 8. As can be seen from Fig. 8, with the increase of in-situ stress, the number of radial cracks decreases significantly, and the length of radial cracks decreases gradually, indicating that there is an inhibition effect of in-situ stress on the explosion load, which is consistent with the results of the current study. Comparing the calculation results in Fig. 7(b) and Fig. 8, it can be seen that the crack extension law under the action of coupled stress field is completely different from that without the action of in-situ stress, and there is a guiding effect of in-situ stress on the crack extension after the explosion of explosives.

To characterize the change rule of crack extension with the coupling stress, the length and direction of the longest radial main crack after the completion of the model calculation under different working conditions are measured, and the results are listed in Table 7. From Table 7, it can be seen that the cracks around the blasthole are approximately uniformly distributed when there is no in-situ stress. With the addition of in-situ stress, the cracks around the blasthole were approximately"X-shaped". When the lateral pressure coefficient λ is 0.42, the longest radial main crack extension direction is approximately 23° from the vertical direction, which is basically the same as the arctanλ result. Take working condition 3 as an example, the average value of the angle between the longest radial main crack and the vertical direction is 21.5°, and the theoretical calculation result is 23°, and the error of the two is controlled at 6.5%. The average length of the longest radial main crack is 75.91 cm, and the theoretical calculation result is 80.329 cm, and the error of the two is controlled at 5.5%, which verifies the correctness of the theoretical formula. The results of the above analysis show that the in-situ stress has a guiding effect on the crack extension after the explosion of explosives, and the range of the cracked zone under the action of the coupled stress field is not uniformly distributed. When the lateral pressure coefficient is known, the direction of extension of the longest radial main crack can be determined.

The crack extension after the completion of model calculation for working conditions 6 to 10 is shown in Fig. 9. As can be seen in Fig. 9, the length of the longest radial main crack gradually decreases with the increase of the lateral pressure coefficient λ. The length and direction of the longest main crack after the model calculations were completed were measured for different operating conditions and the results are listed in Table 8. As can be seen from Table 8, the longest radial main crack is at an angle of 11.7°, 19.5°, 27.6°, 35.3°, and 45.3° to the vertical direction after the model calculations for working conditions 6 to 10 are completed, respectively. The errors between the simulation results and the theoretical calculations are 0.7°, 2.3°, 3.3°, 3.4°, and 0.3°, respectively, and the errors are controlled within 4°, which verifies the correctness of the theoretical formulas. The above analysis results show that the range of cracked zones after the action of coupled stress field is not uniformly distributed under the condition of different lateral pressure coefficients of the same in-situ stress. When the lateral pressure coefficient is known, the direction of extension of the longest radial main crack can be determined.

Discussion

From Eqs. (1) to (11), it can be seen that the axial charging coefficient le (le = lc/lb), lateral pressure coefficient λ, dynamic compressive strength σcd and dynamic tensile strength σtd will have an important effect on the range of crushed zone and cracked zone under the action of the in-situ stress, and the influence law is analyzed in detail in this section.

Effect of axial charging coefficient l e

The axial charging coefficient le, i.e., the amount of charge, has a large effect on the impact stress Pd on the wall of the blasthole after the explosion of the explosives, and therefore affects the range of the crushed zone and cracked zone under the action of the in-situ stress. The axial charging coefficient le on the range of crushed zone and cracked zone under in-situ stress is shown in Fig. 10. As can be seen from Fig. 10, the radius of the crushed zone RC, the radius of the cracked zone RT and the radius of the shock wave expanded blast cavity R1 increase with the increase of the charge. The charge has no effect on the final radius R2 of the blast chamber. The charge had the greatest effect on the radius of the cracked zone RT and the least effect on the radius of the blast cavity R2 where the shockwave expanded, As shown in Fig. 10 (c).

Effect of lateral pressure coefficient λ

The lateral pressure coefficient λ has a large influence on the distribution of the in-situ stresses σv and σh and thus on the coupling forces. Here we discuss the influence law of the range of crushed zone and cracked zone under the action of in-situ stress when the lateral pressure coefficient λ is 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, and 0.6 respectively, as shown in Fig. 11. As can be seen from Fig. 11, with the increase of the lateral pressure coefficient λ, the radius of the crushed zone RC and the radius of the shockwave expanded bursting cavity R1 increase, and the radius of the cracked zone RT decreases. The lateral pressure coefficient λ has the largest effect on the radius of the cracked zone RT and the smallest effect on the radius of the blast cavity R2 where the shock wave expands. The sudden increase in the radius of the cracked zone RT at a lateral pressure coefficient λ of 0.3 is due to a decrease in the enhancement factor m.

Based on the analysis of the influence of lateral pressure coefficient λ on the range of each part, it is possible to predict the crack propagation under different in-situ stress conditions. According to the trend of crack propagation, guiding the layout of blast holes can effectively improve the energy utilization efficiency of explosives and enhance the quality of blasting.

Effect of dynamic compressive strength σ cd

The greater the dynamic compressive strength σcd of the rock, the more energy is consumed to form the crushed and cracked zones by blasting in the blasthole. Therefore, the dynamic compressive strength σcd will have a large impact on the range of the crushed and cracked zones formed by the blast from the blasthole. Here we discuss the influence law of the range of crushed zone and cracked zone under the action of in-situ stress when the dynamic compressive strength σcd of the rock is 109.6 MPa, 119.0 MPa, 124.9 MPa, and 128.9 MPa, respectively, as shown in Fig. 12. As can be seen from Fig. 12, the radius of the crushed zone RC, the radius of the cracked zone RT, the radius of the shockwave expanded bursting cavity R1 and the final radius of the bursting cavity R2 decrease gradually with the increase of the dynamic compressive strength σcd. The dynamic compressive strength σcd has the largest effect on the radius of the cracked zone RT, the second largest effect on the radius of the crushed zone RC, and the smallest effect on the radius of the shockwave expanded bursting chamber R1 and the final radius of the bursting chamber R2. The radius of the three zones at the same dynamic compressive strength σcd has the following relationship: RT > RC > R2 > R1.

Effect of dynamic tensile strength σ td

From Eq. (3), when the coupled tangential stress exceeds the dynamic tensile strength σtd of the rock, radial cracks are generated in the rock mass, resulting in the formation of cracked zone. Therefore, the dynamic tensile strength σtd of the rock will have an impact on the range of the cracked zone. The dynamic tensile strength σtd of the rock varies very little with the loading strain rate, and the dynamic tensile strength σtd of the rock is approximately equal to the static tensile strength within the range of loading strain rates for geotechnical blasting. Here we discuss the influence law of the range of crushed zone and cracked zone under the action of in-situ stress when the dynamic tensile strength σtd of the rock mass is 1.6 MPa, 1.78 MPa, and 3.15 MPa, respectively, as shown in Fig. 13. As can be seen in Fig. 13, the radius of the cracked zone RT decreases with the increase of the dynamic tensile strength of the rock σtd. The dynamic tensile strength σtd has essentially no effect on the radius of the crushing zone RC, the radius of the shockwave expanded bursting chamber R1 and the final radius of the bursting chamber R2.

Based on theoretical analysis and analysis of influencing factors, blasting tests were conducted on site. The results of the blasting test were statistically analyzed and averaged, and the test effects of each cycle of blasting are shown in Table 9. According to Table 9, using the guiding effect of in-situ stress to guide the layout of blastholes can reduce the number of blastholes by 15.15%, save drilling time by 14 min, reduce explosive consumption by 0.16 kg·m−3, and save costs by ¥ 622.4. The on-site application of research results can significantly improve the energy utilization efficiency of explosives and reduce the cost of blasting operations.

Conclusions

-

(1)

The modified theoretical calculation method predicts the crack extension length and direction with high accuracy, and the errors with the numerical simulation results are controlled at 5.5% and 4°, respectively.

-

(2)

When there is no in-situ stress, the cracks around the blasthole are approximately uniformly distributed, and after the addition of in-situ stress, the cracks around the blasthole are approximately distributed in an"X-shape". With the increase of lateral pressure coefficient λ, the extension direction of the longest radial main crack extension direction changes significantly, and its angle with the vertical direction and arctanλ results are basically the same. When the lateral pressure coefficient λ is known, the direction of extension of the longest radial main crack can be determined.

-

(3)

With increasing axial loading coefficient, RC, RT, and R1 increase. With increasing lateral pressure coefficient, RC and R1 increase and RT decreases. With the increase of dynamic compressive strength σcd, RC, RT, R1, and R2 decrease gradually. RT decreases with increasing dynamic tensile strength σtd.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- σV :

-

The vertical in-situ stress (MPa)

- σH :

-

The horizontal in-situ stress (MPa)

- Pd :

-

The homogeneous force acting on the wall of the blasthole (MPa)

- σcd :

-

Dynamic compressive strength (MPa)

- σtd :

-

Dynamic tensile strength (MPa)

- r0 :

-

The radius of the blasthole

- r:

-

The distance from the calculation point to the center of the packet

- RC :

-

The crushed zone radius (mm)

- RT :

-

The cracked zone radius (mm)

- r1 :

-

The blast cavity radius corresponding to r (m)

- R1 :

-

The blast cavity radius (mm)

- r2 :

-

The instantaneous blast cavity radius corresponding to P (mm)

- R2 :

-

The final radius of the blast cavity (mm)

- ρm :

-

The original rock density (kg/m3)

- ρr :

-

The rock density behind the shock wave front at the blast hole wall (kg/m3)

- ρ0 :

-

The density of the explosive (kg/m3)

- dc :

-

The diameter of the cartridge (m)

- db :

-

The diameter of the blasthole (m)

- lc :

-

The charge length (m)

- lb :

-

The length of the blasthole (m)

- le :

-

The axial charging coefficient

- P:

-

The pressure of the explosion gas (MPa)

- P0 :

-

The explosive gas pressure at the beginning of expansion (MPa)

- Pk :

-

The critical pressure (MPa)

- θ:

-

The angle between the line between any point in the rock and the center of the blasthole and the horizontal direction (°)

- α,β:

-

The pressure attenuation coefficient

- μ:

-

Poisson’s ratio

- λ:

-

Coefficient of lateral pressure

- m:

-

The coefficient of enhancement of the tensile strength of the rock

- a, b :

-

The rock test constants

- V0 :

-

The initial velocity of the rock particle at the blast hole wall

- D:

-

The detonation velocity of the explosive (m/s)

- γ:

-

The expansion adiabatic exponent of the detonation product

- n:

-

The pressure increase coefficient of the detonation gas impacting the hole wall

References

Tan, N. G., Yang, R. S. & Tan, Z. Y. Influence of complicated faults on the differentiation and accumulation of in-situ stress in deep rock mass. Int. J. Mineral. Metall. Mater. 30(5), 791–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12613-022-2528-y (2023).

Li, X. H. et al. Numerical study on the behavior of blasting in deep rock masses. Tunn. Undergr. Space. Technol. 113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.103968 (2023).

Xie, H. P. Research progress in deep rock mechanics and mining theory. J. Coal Sci. 44(05), 1283–1305. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2019.6038 (2019).

Zhou, J., Li, X. B. & Mitri, H. S. Evaluation method of rockburst: State-of-the-art literature review. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 81, 632–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2018.08.029 (2018).

Dou, S. Q., Liu, J. Y., Xiao, J. Z. & Pan, W. Economic feasibility valuing of deep mineral resources based on risk analysis: Songtao manganese ore - China case study. Res. Policy 66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101612 (2020).

Tian, Q. F. et al. Study on the mechanism of rock burst in high in-situ stress horizontal rock strata tunnels: Taking the grand canyon tunnel as an example. Tunn. Constr. (Chin. Engl.) 41(S1), 223–231 (2021).

Jiang, Q., Feng, R. T., Xiang, R. B. & Su, G. S. Rockburst characteristics and numerical simulation based on a new energy index: A case study of a tunnel at 2,500m depth. Bull. Eng. Geol. Env. 69(3), 381–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-010-0275-1 (2010).

Liu, D. Q. et al. Experimental simulation study of rockburst characteristics of Sichuan – Tibet granite: A case study of the Zheduoshan tunnel. Eng. Geol. 305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106701 (2022).

Kumar, P., Mohammadi, H., Chopra, R., Tyagi, S. K. & Pandey, S. K. A newly developed blasting cut in tunnels; application of “combined method” in small to medium-sized tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2023.105426 (2023).

Shi, H. X. et al. Safety assessment of ancient buddhist pagoda induced by underpass metro tunnel blasting vibration. Eng. Fail. Anal. 145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2023.107051 (2023).

Gou, Y. G. et al. Attenuation assessment of blast-induced vibrations derived from an underground mine. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2020, 127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104220 (2020).

Tian, E., Zhang, J. W., Tehrani, M. S., Surendar, A. & Ibatova, A. Z. Development of GA-based models for simulating the ground vibration in mine blasting. Eng. Comput. 35(3), 849–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-018-0635-1 (2019).

Ge, J. J. Model experimental study on crack propagation in rock blasting under initial stress state. Anhui Univ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.26918/dcnki.ghngc.2020.000423 (2020).

Yang, J. H., Peng, C., Ye, Z. W., Leng, Z. D. & Wei, B. Research on energy distribution of shock wave in deep rock mass blasting. J. Ordn. Ind. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.12382/bgxb.2023.0254 (2023).

Wang, M. X. Experimental study on explosion stress field and rock damage and failure mechanism under confining pressure. Anhui Univ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.26918/dcnki.ghngc.2019.000170 (2019).

Zhang Y.F. Experimental study on the confining pressure effect model of excavation blasting in high stress rock tunnels. China Univ. Min. Technol. (Beijing) (2018).

Yang, L. Y., Huang, C., Bao, S. J. & Zhang, L. Y. Model experimental study on controlled blasting of slit charge in deep rock mass. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 138, 106318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2020.106318 (2020).

Ding, C. X., Yang, R. S. & Yang, L. Y. Experimental results of blast-induced cracking fractal characteristics and propagation behavior in deep rock mass. Int. J.Rock Mech.Min. Sci. 142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2021.104772 (2021).

Zhu, F. H., Liu, Z. G. & Huang, A. C. The shaped blasting experimental study on damage and crack evolution of high stress coal seam. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2023.105030 (2023).

Yang, R. S., Ding, C. X., Li, Y. L., Yang, L. Y. & Zhao, Y. Crack propagation behavior in slit charge blasting under high static stress conditions. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 119, 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.05.002 (2019).

Li, X. D., Liu, K. W., Yang, J. C. & Song, R. T. Numerical study on blast-induced fragmentation in deep rock mass. Int. J. Impact eng. 170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2022.104367 (2022).

Zhang, F., Yang, L. Y., Hu, H. N., Huang, C. & Chen, S. Y. Study on the crack propagation behaviour of eccentric uncoupled blasting in a deep-level rock mass. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 419–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/17480930.2023.2213546 (2023).

Li, X., Pan, C., Li, X. F., Shao, C. M. & Li, H. B. Application of a synthetic rock mass approach to the simulation of blasting-induced crack propagation and coalescence in deep fractured rock. Geomech. Geophy. Geo-Energy Geo-Res. 8(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-022-00376-4 (2022).

Jiang, X. D. et al. Dynamic responses and damage mechanism of rock with discontinuity subjected to confining stresses and blasting loads. Int. j. Impact eng. 172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2022.104404 (2023).

Dai, J. Rock dynamic characteristics and blasting theory. Beijing: Metallurgical Industry Press, 147–159 (2002).

Zhang, F.T. Explosion energy distribution of rocks under the action of columnar coupled charges. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. (2007).

Tian, X. C., Tao, T. J. & Xie, C. J. Research on the theory and method of reduced-hole blasting for large cross-section tunnel based on explosive energy dissipation. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Res. 10 (2024), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-024-00816-3 (2024).

Dai, J. & Qian, Q. H. Tunnel collapse blasting parameters under high in-situ stress conditions. Explos. Shock 03, 272–277 (2007).

Holmquist T.J., Johnson G.R.& Cook W.H. A computational constitutive model for concrete subjective to large strain, high strain rates, and high pressure. In 1th International Symposium on Ballistic 591–600 (Quebec City, Canada 1993).

Fang, Q., Kong, X. Z., Wu, H. & Gong, Z. M. A method for determining the parameters of the Holmquist Johnson Cook model for rocks. Eng. Mech. 31(03), 197–204 (2014).

Liu, J. C. et al. Numerical analysis and application of optimized charging structure for water sealed blasting. Vib. Shock. 39 (09), 57–62+96. https://doi.org/10.13465/j.cnki.jvs.2020.09.008 (2020).

Wang, P. Optimization of parameters for wedge cut blasting in large cross-section tunnels. Guangxi Univ. https://doi.org/10.27034/dcnki.ggxiu.2020.001794 (2020).

Li, F. Q. Numerical simulation study on hollow hole wedge cut blasting. J. Beijing Inst. Tech. https://doi.org/10.26948/dcnki.gbjlu.2018.000315 (2018).

Yang Y.M., Jiang N., Yao Y.K., Zhou C.B., Meng X.Z.& Zhao .X. Characteristics of stress concentration distribution in layered surrounding rock tunnels under dynamic and static loads. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Edit.). 1–4 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported the Young Researcher Program of the Science and Technology Foundation of Guizhou Province (Qiankehe Jichu QN [2025]223), Science and Technology Program of Guizhou Province (Qiankehe Platform KXJZ [2024]020), and Guizhou Province Science and Technology Plan Innovative Talents Team Project (Qiankehe Platform Talents-CXTD [2022] 010).

Funding

The Young Researcher Program of the Science and Technology Foundation of Guizhou Province (Qiankehe Jichu QN [2025]223), Science and Technology Program of Guizhou Province (Qiankehe Platform KXJZ [2024]020), and Guizhou Province Science and Technology Plan Innovative Talents Team Project (Qiankehe Platform Talents-CXTD [2022] 010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.-C.T.: Software, Validation, Data curation, Writing—original draft. T.-J.T.: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. L.H.: Organizing and analyzing on-site experimental data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

TIAN, X., TAO, T. & HUANG, L. Modification and validation of cracked zone range under coupled in-situ stress and blasting load. Sci Rep 15, 29516 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15453-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15453-3