Abstract

Sand flies are medically important insects with diverse distributions and roles in pathogen transmission. Globally, over a thousand species have been documented, with Indian sand fly fauna currently comprising 71 species. Traditional morphological identification faces challenges due to specimen damage and the presence of cryptic species. This study utilizes DNA barcoding of the mitochondrial marker, cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) to enhance accurate identification of Indian sand flies. A total of 10,456 sand flies, representing 31 species, were collected from 26 districts across six Indian states between 2018 and 2024. Legs from voucher specimens were used to generate ~ 720 bp COI sequences, which were analyzed phylogenetically. In total, 169 COI sequences were generated. A common 570 bp region was selected for final analysis. The gene showed an AT-rich composition with a GC content of 34.8%. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis, supported by ABGD and ASAP species delimitation methods, confirmed the majority of morphological identifications. Species delimitation analyses using ABGD, ASAP, and bPTP grouped the specimens into 32, 34, and 68 clusters, respectively, with bPTP showing evidence of over splitting. Despite this, COI-based classification proved effective in delineating species boundaries and serves as a reliable tool for the DNA barcoding of sand fly species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) are important vectors of protozoan parasites, particularly Leishmania spp. (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae), and are also known to transmit bacterial pathogens and arboviruses (Chandipura virus)1,2,3. Leishmaniasis presents in three primary clinical forms: visceral leishmaniasis (VL) also known as kala-azar, the potentially fatal if not treated; cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), the most prevalent form, manifests as skin ulcers and lesions; and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL), which affects the mucosa of the oral, nasal, and pharyngeal cavities4. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that leishmaniasis remains endemic in more than 98 countries, particularly across regions such as the Central Asia, Mediterranean, and East Africa. Globally, more than 300 million people remain at risk, with approximately 90,000 cases reported each year; however, less than half of these cases are officially documented. India, along with Sudan, Bangladesh, Brazil, and Ethiopia accounts for nearly 94% of the world’s kala-azar cases, with India itself contributing approximately 18% of the total cases4,5.

Globally, over 1,000 species of sand flies have been documented, with their habitats ranging across tropical, temperate, and arid environments. In the Old World, sand flies are classified into 17 genera, including fossil species, such as Phlebotomus, Sergentomyia, Grassomyia, Chinius, Idiophlebotomus, etc. Conversely, in the New World, they are categorized into 23 genera, including Lutzomyia, Brumptomyia, Warileya, Micropygomyia, etc6. Despite this diversity, only species from the genera Lutzomyia (New World) and Phlebotomus (Old World) have been confirmed as competent vectors of Leishmania7,8,9. Accurate species identification through entomological surveillance is crucial for assessing disease transmission risks and developing effective vector control strategies, particularly in these endemic regions. However, traditional species identification methods rely primarily on morphological characteristics and these methods face several challenges, such as phenotypic plasticity, the presence of cryptic species, and isomorphic females10. Additionally, specimens may sustain damage during collection, transport, dissection, or slide mounting, which can hinder accurate identification. Moreover, identifying closely related species requires specialized taxonomic expertise. These challenges underscore the need for an integrated taxonomic approach that consider morphological, ecological, behavioral, and molecular details, providing more accurate and comprehensive species identification11,12.

DNA barcoding, a molecular technique based on the mitochondrial marker cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene, has demonstrated as a reliable tool for identification of species across diverse taxa13,14,15,16. The COI gene is particularly suitable for this purpose due to its high genetic variability among species while exhibiting minimal variation within the same species. This characteristic makes it a suitable marker for identifying a diverse range of animal taxa, even when using small, degraded, or processed samples14,17. This technique has been successfully applied to various insect groups, including sand flies18. Notably, DNA barcoding has facilitated the identification of sibling species in the New World sand flies19. While some sand fly species already have COI barcode sequences dataset is available in genetic databases such as National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank, significant gaps persist, particularly for Old World sand fly species with special emphasis to Indian subcontinent20,21,22,23,24. The present study aims to bridge these gaps by amplifying the COI gene and generating DNA barcodes for sand fly species found in India. These molecular markers will not only improve the accuracy of species identification but also provide valuable insights into sand fly systematics, their ecological roles, and their involvement in disease transmission.

Results

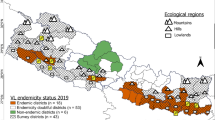

Altogether 10,456 sand flies were captured from 26 districts across multiple states in India during the period 2018–2024 (Fig. 1). The sand flies were morphologically identified into 31 distinct species using standard taxonomic keys25,26. These species belonged to four genera: Grassomyia, Idiophlebotomus, Sergentomyia, and Phlebotomus. Among the identified species, nine were classified under the genus Phlebotomus (Ph. ajithii [n = 54], Ph. argentipes [n = 3360], Ph. burneyi [n = 76], Ph. colabaensis [n = 1269], Ph. longiductus [n = 174], Ph. major [n = 17], Ph. papatasi [n = 108], Ph. sergenti [n = 199], and Ph. stantoni [n = 443]), 20 species under Sergentomyia (Se. africana [n = 20], Se. ashwanii [n = 39], Se. babu babu [n = 1980], Se. baghdadis [n = 599], Se. bailyi [n = 287], Se. christophersi [n = 208], Se. clydei [n = 58], Se. dhandai [n = 203], Se. eadithae [n = 3], Se. himalayensis [n = 211], Se. hospitii [n = 1], Se. insularis [n = 154], Se. jerighatiansis [n = 231], Se. kauli [n = 2], Se. linearis [n = 21], Se. modii [n = 2], Se. monticola [n = 143], Se. punjabensis [n = 133], Se. shorttii [n = 101], and Se. zeylanica [n = 177]), and one species each from the genera Grassomyia (Gr. indica [n = 179]) and Idiophlebotomus (Id. tubifer [n = 4]) (Figure S1-31). Sergentomyia africana, a new country record was made in the current study. These specimens were collected from Jhanwar village in Jodhpur district of Rajasthan in resting and light trap collection from cattle shed adjacent to human dwellings. Representative samples from each species were utilized for COI DNA barcoding. In total, 169 new COI barcode sequences were generated and analyzed from specimens collected across different regions of the country. While Se. hospitii was identified morphologically, its nucleotide sequence could not be generated due to poor chromatogram quality, which hindered contig assembly.

Map showing the study sites from different district, states in India. Kerala: 1- Thiruvananthapuram, 2- Kollam, 3- Pathanamthitta, 4- Kottayam, 5- Idukki, 6- Ernakulam, 7- Palakkad, 8- Thrissur, 9- Malappuram, 10- Wayanad, 11- Kozhikode, 12- Kannur, 13- Kasaragod; Madhya Pradesh: 14- Hoshangabad, 15- Sagar, 16- Bhopal; West Bengal: 17- Malda; Bihar: 18- Vaishali; Rajasthan: 19- Ajmer, 20- Nagaur, 21- Jodhpur, 22- Bikaner; Himachal Pradesh: 23- Shimla, 24- Mandi, 25- Kinnaur, 26- Kullu.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree generated from COI sequences of sand fly species from India. The clades showing genetic distance < 0.03% have been collapsed. Bootstrap values (frequency) above 0.8 are indicated at each node. The clades containing the sequences generated in this study are highlighted in red. The delimitation partitions identified by the ASAP, ABGD, and bPTP algorithms are shown as black bars corresponding to each clade. The species that were split into more than one groups based on bPTP analysis are indicated by the number of splits. The total number of groups identified by each analysis is shown below the respective bars.

A total of 169 COI sequences (ranging from 585 to 711 base pairs) were generated from 30 morphologically identified sandfly species in this study. These sequences were submitted to the NCBI GenBank repository, with accession numbers listed in Table 1. Each species was represented by a minimum of two and a maximum of eight individuals. Multiple sequence alignment revealed no stop codons, insertions, deletions, pseudogenes, or NUMTs, indicating good-quality mitochondrial sequences. For downstream analysis, a common 570 bp region (positions 70–639) was selected, and all sequences exhibited a typical AT-rich composition, with an average GC content of 34.8%.

In total, 170 sequences (569 bp), including the 169 newly generated and one reference sequence Brumptomyia guimaraesi (GenBank accession: KC921225), were used for Maximum Likelihood (ML) analysis using General Reversal Tree (GTR) model with G4. Additionally, 64 sequences retrieved from GenBank were incorporated into the dataset, resulting into total 233 sequences. The ML tree revealed clear separation of species into distinct clades. The clades were collapsed using a 0.03 genetic distance threshold, which provided a practical basis for visualizing interspecific divergence. Most species clustered into well-supported monophyletic groups with bootstrap values exceeding 80%, validating morphological identification (Fig. 2). Notably, species belonging to the Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia genera grouped distinctly, with strong bootstrap support indicating reliable resolution at the genus level.

Within the Phlebotomus clade, multiple individuals of the same species clustered tightly together, suggesting low intraspecific divergence and genetic homogeneity. Similarly, Sergentomyia species showed cohesive grouping, affirming their genetic distinction from Phlebotomus. Some species such as Ph. argentipes, and Ph. papatasi, showed minimal internal branching, implying a high degree of sequence similarity among the sampled individuals. However, a few discrepancies were also observed. Some individuals did not cluster within their expected species clades. These outlier sequences appeared as isolated branches or clustered with individuals from different species, suggesting possible misidentification, sequence contamination, or unresolved cryptic diversity. For example, Se. punjabensis did not form a single monophyletic clade; instead, its members split into two distinct groups. One group contained only Se. punjabensis sequences as expected, while the other was more distantly placed, and grouped with Se. indica, suggesting either cryptic diversity or misidentification. Similarly, Ph. papatasi displayed an anomaly where two GenBank sequences formed a separate basal clade. GenBank sequences of some species also showed unexpected diversity with more than > 0.03 genetic distance. For example, Ph. major formed three distinct clades, Ph. sergenti formed two, Ph. longiductus formed two, and Ph. stantoni also appeared to split into multiple lineages. Multiple binns have been identified among these species in BOLD database suggesting the existence of genetically distinct lineages.

BLAST analysis (NCBI GenBank tool) against the BOLD database showed high similarity between our sequences and the respective species sequences from the database. The only exception was Gr. indica, which showed unexpectedly high similarity with Se. punjabensis. In the BOLD database, sequences of Ph. major, Ph. stantoni, and Se. bailyi exhibited a lower similarity range, meaning that some of the sequences showed less than 97% similarity. This indicates either possible misidentification in the database, sequencing errors, or genetic divergence due to geographical variation.

Species delimitation analyses using ABGD further supported the presence of distinct species boundaries. ABGD identified a clear barcode gap separating intra- and inter-specific distances. This analysis identified 34 groups. Notably, three closely related species; Se. shorttii, Se. insularis, and Se. babu babu exhibited low interspecific distances (< 0.03), suggesting either recent divergence or ongoing gene flow. The average genetic distance between Se. shorttii and Se. insularis was 0.0346, however, the genetic distance between Se. babu babu and Se. shorttii was 0.0244, and between Se. babu babu and Se. insularis, it was 0.0235. High genetic similarity among these three species was also observed among the sequences available in BOLD database. Additionally, Ph. longiductus sequences from India and Bhutan formed separate clusters, while Ph. papatasi sequences from Serbia and Nepal also formed distinct cluster, suggesting possible geographical structuring or cryptic speciation.

Similarly, the ASAP analysis provided similar partitioning patterns to ABGD, supporting 32 candidate species depending on the threshold. Most morphospecies corresponded to single partitions as observed in ABGD analysis Ph. christophersi showed three groups (Fig. 2).

In contrast, bPTP analysis, based on the maximum likelihood tree, showed signs of oversplitting by delimiting 68 putative species from the dataset. However, only 22 clusters showed high posterior probability support (> 0.90), and overall data indicated low overall congruence. The method also proposed splits within morphologically identified species such as Ph. burneyi, Ph. bailyi, Ph. major and Ph. longiductus (Fig. 2), suggesting a potential overestimation of species boundaries.

Discussion

Sand fly diversity and its spatial distribution in the Oriental region were first documented by Lewis (1978)26 and later expanded by Kalra and Bang (1988)25. Subsequently, several new species were reported from India, with the most recent comprehensive checklist by Shah et al., (2023)27 documenting a total of 69 species. Additionally, two new species were recently described from the Western Ghats region of Kerala, increasing the total number of recorded Indian sand fly species to 7123,24,27.

However, discussions in recent publications by Renaux et al., (2023)28 have raised uncertainties regarding the validity of certain species, such as Phlebotomus chiyankiensis (Singh, Phillips Singh, and Ipe, 2009) and Ph. palamauensis (Phillips Singh and Ipe, 2007). The species descriptions provided by the authors were primarily based on illustrations and morphological characteristics, which may not be sufficient for definitive taxonomic classification. Furthermore, following a systematic revision of the subgenus Anaphlebotomus, Ph. maynei was reinstated as a valid species based on holotype examination by Renaux et al., (2023)28. Given these taxonomic uncertainties, it is evident that morphological identification alone is insufficient for reliable species characterization. Integrating molecular techniques is essential to strengthen taxonomic accuracy. Recently, several studies have emphasized the significance of COI-based sand fly classification in both the Old and New World countries10,18,20,21,29,30. However, research on DNA barcoding of sand flies remains limited in the Indian subcontinent, with only a few studies contributing genetic data alongside taxonomic records21,23,24. To address this gap, the present study aims to generate and correlate morphological identifications of sand fly species with molecular genetic data through DNA barcoding.

In the current study, COI barcodes were developed for several Indian sand fly species for the first time, corresponding to morphologically identified specimens. These species include Sergentomyia dhandai, Se. jerighatiansis, Se. kauli, Se. linearis, Se. modii, and Idiophlebotomus tubifer. Additionally, this study recorded Se. africana in India for the first time, collected from cattle sheds in Jhanwar village, Jodhpur, Rajasthan. Originally described by Newstead in 1912 from Nigeria, Se. africana has since been reported in South Africa, Sudan, Uganda, and Ghana6.

Genetic divergence analysis and the clustering pattern of the maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree confirmed that most of the morphologically identified species analyzed in this study could be accurately identified using COI- based DNA barcode. The intraspecific genetic distances (Jukes Cantor) ranged from 0.00 to 0.092, while interspecific genetic distances among the 30 species analyzed in this study ranged between 0.024 and 0.252 (Figure S32) (Table 2). Species delimitation using ASAP and ABGD showed similar patterns of clustering, while bPTP showed over-splitting, probably due to the differences in algorithmic assumptions. As ABGD and ASAP are based on distance-based method, while bPTP depends on the branching patterns of the tree31, this discrepancy can be attributed to their underlying methodologies.

Moreover, some of the species based on the BOLD database showed lower genetic diversity, while the GenBank sequences were found to be more diverse for some species, such as Ph. sergenti, Se. africana, and Se. christophersi. This might be due to misidentification, sequencing errors (which are possible in GenBank database), or the fact that the sequences are from diverse geographical locations, and the geographical variation among them might have led to this divergence.

Closely related species, such as Se. shorttii, Se. insularis, and Se. babu babu25,26, which exhibit morphological similarities and differ primarily in the number of cibarial teeth, formed separate clades in the phylogenetic tree, supported by bootstrap values greater than 99%. However, the interspecific genetic distances between these three species were lower than 0.03, indicating limited genetic divergence among them. Even the already available sequences of these three species in BOLD and GenBank showed high genetic similarity within these three species. Similar patterns of low divergence among closely related sand fly species based on COI have also been observed in previous studies21,32, suggesting that mitochondrial COI may lack the resolution to differentiate such taxa.

This pattern was further confirmed by species delimitation analyses using ASAP, and ABGD, which grouped these three species together in one cluster. While bPTP separated Se. shortii from other two species, however the posterior support was very low (0.244). This suggests that COI alone may not be sufficient to distinguish such closely related species. Therefore, the incorporation of additional molecular markers or a combination of markers may be necessary for more accurate species delimitation in these groups. Similarly, Se. eadithae and Id. tubifer clustered with Phlebotomus spp. in the phylogenetic analysis, showing an interspecific genetic distance of 0.055 between them. Idiophlebotomus tubifer was previously classified under the subgenus Idiophlebotomus of the genus Phlebotomus. However, this subgenus was later elevated to genus level33, resulting in the current nomenclature Id. tubifer. This taxonomic revision could explain the phylogenetic grouping of Id. tubifer with Phlebotomus spp. In contrast, the grouping of Se. eadithae with Phlebotomus spp. in the phylogenetic analysis warrants further investigation, potentially involving a larger sample size and the inclusion of additional molecular markers, such as cytb (cytochrome b) and EF1α (elongation factor 1-alpha). These markers could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the genetic relationships of this species and help clarify its taxonomic status10,32.

Another major discrepancy observed was the clustering of Gr. indica with Se. punjabensis sequences retrieved from GenBank, which were deposited from Sri Lanka and Nepal. Grassomyia indica was previously classified under the subgenus Grassomyia of the genus Sergentomyia. However, this subgenus was later elevated to genus level34, resulting in the current nomenclature Gr. indica. It is the only species under this genus reported from India27, and is morphologically distinct, characterized by a combination of a convex cibarial tooth-row and rounded spermatheca in females, and filaments with dilated tips in males, distinguishing it from all other species reported from the Oriental region25,26 (Figure S1-31). In contrast, Se. punjabensis is classified under the subgenus Sergentomyia of the genus Sergentomyia. This species can be clearly distinguished based on key morphological features such as the pharynx is very wide posteriorly, and its armature possesses a deep, acute hind notch with much smaller hind teeth compared to the fore teeth in females and the paramere is thick and hooked in males25,26 (Figure S1-31). Further, in the present study, the molecular data for each species were well supported by morphological identification. Therefore, the unexpectedly high similarity between Gr. indica and Se. punjabensis may be attributed to a possible misidentification of the Se. punjabensis sequences retrieved from the GenBank database.

In conclusion, this study presents, for the first time, COI barcode sequences for several Indian sand fly species, along with the first recorded occurrence of Se. africana in the country. The newly generated sequences for species that had not previously been analyzed using this molecular marker enhance DNA repositories, improving the accuracy of sand fly identification through integrative DNA barcoding. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that all phlebotomine sand flies clustered with high confidence, aligning with their morphological classification. Future studies should focus on resolving the presence of sibling species within certain groups, which may require a reassessment of morphology-based taxonomy. This is particularly crucial for widely distributed and epidemiologically significant species involved in pathogen transmission to humans and other vertebrates. Overall, this study underscores the importance of molecular tools in sand fly taxonomy and signifies the need for continued research to refine species classification and better understand their role in disease transmission.

Limitation

Previously, species identification relied solely on morphological characteristics, without molecular validation. As a result, molecular analyses, such as COI DNA barcoding, may cluster morphologically similar species into different genera or subgenera. This limitation can be mitigated by increasing the sample size for each species and employing a multi-marker approach for molecular characterization, thereby enhancing taxonomic resolution.

Materials and methods

Study area and sample collection

Sand flies were captured over a period from 2018 to 2024 from diverse indoor and outdoor habitats, including human lodgings, goat and cattle sheds, dog kennels, tree hole and buttresses, animal burrows, termite mounds, and chicken coops across tribal hamlets and villages in various regions of India. Standard collection methods (mechanical aspirator, light trap) were utilized for collection of samples35. The collection sites spanned multiple states: southern India (Kerala—Thiruvananthapuram, Kollam, Malappuram, Pathanamthitta, Kottayam, Ernakulam, Thrissur, Palakkad, Idukki, Wayanad, Kozhikode, and Kasaragod), western India (Rajasthan—Ajmer, Bikaner, Nagaur, and Jodhpur), northern India (Himachal Pradesh—Shimla, Kinnaur, Mandi, and Kullu), eastern India (Bihar—Vaishali; West Bengal—Malda), and central India (Madhya Pradesh—Sagar, Bhopal, and Hoshangabad) (Fig. 1).

The specimens were subjected for dissection under a stereo-microscope (Zeiss Stemi 305, Frankfurt, Germany) using sterile entomological needles on pre-sterilized microscopic slides. The head and posterior three abdominal segments were mounted in Hoyer’s medium. Simultaneously, two legs from one side of each specimen were transferred to sterile 1.5-mL microtubes (Axygen, India) and stored at -40 °C for subsequent molecular analysis. To prevent cross-contamination, stringent sterilization protocols were followed, including disinfecting the dissecting needles between specimens.

Species identification was carried out using established taxonomic keys25,26. The diagnostic morphological characteristics examined included the cibarial arch and teeth in the cibarium, the pharynx in both the sexes, and structural variations in male terminalia, such as the style, paramere, spines, and aedeagus, along with the spermathecae in females. Voucher specimens were consigned in the ICMR- Vector Control Research Centre (VCRC) institute museum in Pondicherry, India, with unique access code. Legs from representative number of preserved specimens from each species were subsequently utilized for DNA barcoding and molecular analyses.

DNA barcoding

The genomic DNA was isolated from legs samples using DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hannover, Germany) following the product manual. Aseptic conditions were ensured during DNA extraction procedure to reduce the chances of contamination. The DNA was finally eluted in nuclease free molecular grade water and stowed in deep freezer (-40°C) which was further utilized for COI gene amplification following the PCR protocol described by Kumar et al., 201221. The PCR gene amplification was carried out using the Taq PCR Core Kit (QIAGEN GMBH, Germany) and primers: forward primer- LCO 1490 (5’-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3’); reverse primer- HCO 2198 (5’-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3’)15,16. PCR was followed by gel electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel, and the results were visualized with a UV transilluminator. Subsequently, the ~ 720 bp amplicon was purified using a gel extraction kit (QIAGEN GMBH, Germany) and custom sequenced (Sanger sequencing) using the same set of primers.

Phylogenetic analysis

The raw chromatogram data from sequencing were edited and assembled into contigs using Chromas software (version 2.6.6) for each sand fly specimen. The resulting DNA sequences were then aligned in MEGA 11.1 software with a reference COI sequence of Brumptomyia guimaraesi (GenBank accession: KC921225). The sequences were analyzed using BLAST (NCBI GenBank tool) against the BOLD database, and the range of similarity percentages was recorded for each species (Table 3). The sequences were also BLAST-analyzed against the GenBank database, and all the sequences of the respective species available in GenBank were retrieved. However, only one representative sequence from different countries for each species (Table S1), was included for further analysis to cover geographical diversity. Sequences with ambiguous bases and lengths < 500 bp were excluded.

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method in MEGA 7.0 software. The best model fitting the dataset was identified using the best model selection algorithm, and the tree was constructed applying 500 bootstraps for branch support. Brumptomyia guimaraesi (GenBank accession: KC921225) was used as an outgroup for rooting the tree.

Additionally, species delimitation was assessed using the Bayesian Poisson Tree Processes (bPTP) method36, Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning (ASAP)37, and the Automatic Barcode Gap Discovery (ABGD) method38. These analyses were carried out using web servers39,40. ABGD analysis was conducted using the Jukes-Cantor model with prior maximal distance values ranging from 0.05 to 0.1. For ASAP, the first 10 best scoring partitions were obtained using split groups with a probability threshold below 0.005. Similarly, bPTP analysis was carried out using the rooted ML tree generated in this study, with 1,00,000 MCMC generations and a 0.1 burn-in. The final COI sequences were submitted to the NCBI GenBank database for future reference.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author (Prasanta Saini) upon request. Additionally, the sequences generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database and can be accessed using the accession numbers provided in Table 1.

References

Cecílio, P., Cordeiro-da-Silva, A. & Oliveira, F. Sand flies: basic information on the vectors of leishmaniasis and their interactions with leishmania parasites. Commun. Biol. 5, 305 (2022).

Tom, A., Kumar, N. P., Kumar, A. & Saini, P. Interactions between leishmania parasite and sandfly: a review. Parasitol. Res. 123, 6 (2024).

Damle, R. G. et al. Molecular evidence of Chandipura virus from Sergentomyia species of sandflies in gujarat, India. Jpn J. Infect. Dis. 71, 247–249 (2018).

WHO & Leishmaniasis (2025). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

WHO. Leishmaniasis - India. (2025). https://www.who.int/india/health-topics/leishmaniasis

Galati, E. A. B. et al. Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae) of the world. FIOCRUZ https://doi.org/10.15468/54HQX7 (2024). FIOCRUZ - Oswaldo Cruz Foundation.

Bates, P. A. Transmission of leishmania metacyclic promastigotes by phlebotomine sand flies. Int. J. Parasitol. 37, 1097–1106 (2007).

Kato, H. et al. Molecular epidemiology for vector research on leishmaniasis. IJERPH 7, 814–826 (2010).

Shah, H. K. et al. Nationwide cross-sectional surveillance of Leishmania donovani in phlebotomine sand flies and its impact on National kala-azar elimination in India. Sci. Rep. 14, 28455 (2024).

Contreras Gutiérrez, M. A., Vivero, R. J., Vélez, I. D., Porter, C. H. & Uribe, S. DNA barcoding for the identification of sand fly species (Diptera, psychodidae, Phlebotominae) in Colombia. PLoS ONE. 9, e85496 (2014).

Padial, J. M., Miralles, A., De La Riva, I. & Vences, M. The integrative future of taxonomy. Front. Zool. 7, 16 (2010).

Caterino, M. S., Cho, S. & Sperling, F. A. H. The current state of insect molecular systematics: A thriving tower of babel. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 45, 1–54 (2000).

Rodrigues, B. L. & Galati, E. A. B. Molecular taxonomy of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae) with emphasis on DNA barcoding: A review. Acta Trop. 238, 106778 (2023).

Antil, S. et al. DNA barcoding, an effective tool for species identification: a review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50, 761–775 (2023).

Hebert P.D.N., Cywinska, A., Ball, S. L. & deWaardJ.R. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc. R Soc. Lond. B. 270, 313–321 (2003).

Hebert, P. D. N., Ratnasingham, S. & De Waard, J. R. Barcoding animal life: cytochrome c oxidase subunit I divergences among closely related species. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, (2003).

Andújar, C., Arribas, P., Yu, D. W., Vogler, A. P. & Emerson, B. C. Why the COI barcode should be the community DNA metabarcode for the metazoa. Mol. Ecol. 27, 3968–3975 (2018).

Shashank, P. R. et al. DNA barcoding of insects from india: current status and future perspectives. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49, 10617–10626 (2022).

Sousa-Paula, L. C. D., Pessoa, F. A. C., Otranto, D. & Dantas‐Torres, F. Beyond taxonomy: species complexes in new world phlebotomine sand flies. Med. Vet. Entomol. 35, 267–283 (2021).

Gajapathy, K. et al. DNA barcoding of Sri Lankan phlebotomine sand flies using cytochrome c oxidase subunit I reveals the presence of cryptic species. Acta Trop. 161, 1–7 (2016).

Kumar, N. P., Srinivasan, R. & Jambulingam, P. DNA barcoding for identification of sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in India. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 12, 414–420 (2012).

Wijerathna, T., Gunathilaka, N. & Rodrigo, W. Genetic variation of sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Gampaha and Kurunegala districts of Sri Lanka complementing the morphological identification. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 15, 322–331 (2022).

Shah, H. K., Fathima, P. A., Jicksy, J. & Saini, P. Report of a new species of sand fly, Phlebotomus (Anaphlebotomus) ajithii n. Sp. (Diptera: Psychodidae), from Western Ghats, India. Parasites Vectors. 17, 388 (2024).

Saini, P. et al. Morphological and molecular description of a new species of sandfly, Sergentomyia (Neophlebotomus) ashwanii sp. Nov. (Diptera: Psychodidae) from Western ghats, India. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 17, 226–234 (2024).

Kalra, N. & Bang, Y. Manual on Entomology in Visceral Leishmaniasis (World Health Organization, 1988).

Lewis, D. The Phlebotomine Sand Flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) of the Oriental Region, Entomologyvol. 37 (Natural History), 1978). (Bulletin of the British Museum.

Shah, H. K., Fathima, P. A., Kumar, N. P., Kumar, A. & Saini, P. Faunal richness and checklist of sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in India. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 16, 193–203 (2023).

Renaux Torres, M. C. et al. Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae) from pha Tong cave, Northern Thailand with a description of two new species and taxonomical thoughts about phlebotomus stantoni. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17, e0011565 (2023).

Posada-López, L., Rodrigues, B. L., Velez, I. D. & Uribe, S. Improving the COI DNA barcoding library for Neotropical phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae). Parasites Vectors. 16, 198 (2023).

Lozano-Sardaneta, Y. N. et al. DNA barcoding and fauna of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: psychodidae: Phlebotominae) from Los tuxtlas, veracruz, Mexico. Acta Trop. 201, 105220 (2020).

Stasiukynas, L. et al. COI insights into diversity and species delimitation of immature stages of Non-Biting midges (Diptera: Chironomidae). Insects 16, 174 (2025).

Rodrigues, B. L., Baton, L. A. & Shimabukuro, P. H. F. Single-locus DNA barcoding and species delimitation of the sandfly subgenus Evandromyia (Aldamyia). Med. Vet. Entomol. 34, 420–431 (2020).

Léger, N., Depaquit, J. & Gay, F. Idiophlebotomus padillarum n. Sp. (Diptera Psychodidae) a new sand fly species from Palawan (Philippines). Acta Trop. 132, 51–56 (2014).

Blavier, A. et al. Phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera, Psychodidae) from the Ankarana Tsingy of Northern madagascar: inventory and description of new taxa. Parasite 26, 38 (2019).

Alexander, B. Sampling methods for phlebotomine sandflies. Med. Vet. Entomol. 14, 109–122 (2000).

Zhang, J., Kapli, P., Pavlidis, P. & Stamatakis, A. A general species delimitation method with applications to phylogenetic placements. Bioinformatics 29, 2869–2876 (2013).

Puillandre, N., Brouillet, S. & Achaz, G. ASAP: assemble species by automatic partitioning. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 609–620 (2021).

Puillandre, N., Lambert, A., Brouillet, S. & Achaz, G. ABGD, automatic barcode gap discovery for primary species delimitation. Mol. Ecol. 21, 1864–1877 (2012).

Zhang, J., Kapli, P., Pavlidis, P. & Stamatakis, A. A. General Species Delimitation Method with Applications to Phylogenetic Placements. (2013). https://species.h-its.org/ptp/

ABGD web. SpartExplorer: A tool for taxonomists. Spart explorer A taxonomic web platform to infer, compare and visualize species partitions https://spartexplorer.mnhn.fr/

Acknowledgements

We would also like to acknowledge Mr. Ajithlal PM (Rtd. ICMR-VCRC) Mr. Krishna Prasad (ICMR-VCRC), Ms. Lanza Achu Thomas (ICMR-VCRC), Dr. Mahender Singh Thakur (HP University), Dr. Suman Sundar Mohanty (ICMR- NIIRNCD, Jodhpur), Dr. Ashish Kumar (ICMR- RMRIMS, Patna), Dr. Devojit Kumar Sarma (ICMR- NIREH, Bhopal), Dr. Anjali Rawani (University of Gour Banga, West Bengal) for their support and coordination in collection of sand fly samples during the study.

Funding

This study is funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi (Grant no. 6/9 − 7(331)/2020/ECD-II).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PS contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resource management, supervision, validation, visualization, and the review and editing of the manuscript. HSK contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software application, and both the original drafting and review/editing of the manuscript. FPA contributed to data curation, investigation, methodology, and manuscript review and editing. BG contributed to data analysis and manuscript review and editing. MR contributed to project administration and manuscript review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

All authors have approved and gave their consent to publish the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, H.K., Fathima, P.A., Gupta, B. et al. Molecular identification of wild caught phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae) by mitochondrial DNA barcoding in India. Sci Rep 15, 31950 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15506-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15506-7