Abstract

Some spoken phrases, when heard repeatedly, seem to transform into music, in a classic finding known as the speech-to-song illusion. Repeated listening to musical phrases can also lead to changes in liking, attributed to learning-related reduction of prediction errors generated by the dopaminergic reward system. Does repeating spoken phrases also result in changes in liking? Here we tested whether repeated presentation of spoken phrases can lead to changes in liking as well as in musicality, and whether these changes might vary with musical reward sensitivity. We also asked whether perceptual biases towards low versus high frequencies, as assessed using the Laurel/Yanny illusion, are linked to changes in musicality and liking with repetition. Results show a general reduction in liking for spoken phrases with repetition, but less so for phrases that transition more readily into song. People who upweight low frequencies in speech perception (and so perceive Laurel rather than Yanny) are more susceptible to changes in musicality with phrase repetition and marginally less susceptible to changes in liking. Individuals with musical anhedonia still perceived the speech-to-song illusion, but liked all spoken phrases less; this did not interact with repetition. These results show a dissociation between perception and emotional sensitivity to music, and support a model of frequency-weighted internal predictions for acoustic signals that might drive the speech-to-song illusion. Rather than treating illusions as isolated curiosities, we can use them as a window into theoretical debates surrounding models of perception and emotion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Speech and song are traditionally considered acoustically distinct categories of human vocalization. Recent cross-cultural research supports this view by finding that on average, song has higher pitch, slower tempo, and more stable within-syllable fundamental frequency (F0) contours than speech, and differs from speech in its average spectro-temporal modulation profile1,2. Some spoken phrases, however, undergo a dramatic shift from sounding like speech to sounding like song when taken out of their original context and looped several times. This “speech-to-song illusion” was discovered by Diana Deutsch in 1995, and the first journal article reporting experiments on this illusion appeared in 20113. Since then a rapidly growing body of research has investigated the illusion, motivated by the many questions it raises about the boundaries between speech and music processing in the mind. One salient finding is that whether and how much the perception of a repeated spoken phrase changes from speech to song depends, at least in part, on the acoustic structure of the phrase. Empirical comparison of the acoustics of spoken phrases which do vs. do not tend to transform to song when looped, but which are matched in terms of speaker, syllable rate, and duration (“illusion” vs “control” stimuli), reveals that spoken phrases with less pitch change within each syllable are more susceptible to transformation than phrases with more within-syllable pitch change4,5. Thus certain types of pitch changes in speech can convey melodic structure and create a musical pattern after repeated presentation that continues to influence perception of the spoken phrase up to one week later6.

Repeated presentation of auditory stimuli can modulate preference as well as perception. The classic mere exposure effect is an increase in liking, or preference, with increasing familiarity7. This is well-replicated in the domain of musical sounds, e.g., in studies showing that repeated exposure to melodies in an unfamiliar musical scale enhances preferences for those melodies8,9. However, little is known about the relationship between the change in musicality with repetition demonstrated by the speech-to-song illusion (henceforth, “song illusion”) and the change in liking reported by previous research on repeated exposure to melodies. Here we ask, first, whether the perceptual transformation of a spoken phrase into song with repetition is accompanied by a change in liking. Second, we ask whether individual differences in how much people enjoy music might be associated with the vividness of the song illusion.

One way to conceptually relate these two questions is via Bayesian models of predictive coding for music10 and speech11. According to these models, a person’s prior knowledge about music and speech in their culture influences perception through predictions, with prediction errors leading to learning which updates internal models as the mind seeks to minimize prediction errors during sequence perception. Minimization of prediction errors with repeated exposure could explain why unfamiliar melodies show an increase in liking after repeated listening. However, the rate of change in liking with repetition depends on individual differences in musical reward sensitivity. Using melodies in an unfamiliar musical scale, Kathios et al. (2024) found that people with musical anhedonia, who have diminished sensitivity to the rewards of music listening, after a slight increase of liking with repetition showed decreased liking of novel melodies with further repetition. In contrast, people who were more music-reward-sensitive continued to increase their liking ratings for unfamiliar melodies with repeated exposure. If people with musical anhedonia cannot map their predictions to reward as strongly with repeated listening to music, then they may also be less disposed to extract latent underlying musical regularities from spoken phrases. In other words, individuals with musical anhedonia may not experience the speech-to-song illusion to the same extent as individuals with normal hedonic responses to music. Note that we are not claiming that mapping predictions to reward causes the extraction of musical regularities, only that the two constructs (i.e. prediction-reward mapping and musical perception) might be associated in a way that can be revealed by using musical anhedonia as a model system.

While musical anhedonia may be an effective window into this association, a relationship between enjoyment of music and perception of the song illusion may also extend throughout the general population. Past research has revealed striking and stable individual differences in how vividly people experience the song illusion, with formal musical training playing no significant role. While some individual variation in the vividness of song illusion perception is accounted for by differences in rhythmic and melodic perception abilities, the large majority of variance remains unexplained12. Indeed, we are not aware of any prior work examining how musical reward sensitivity impacts the perception of this (or any) auditory illusion13. If the speech-to-song illusion reflects extraction of musical regularities from speech, then individuals with a greater tendency to enjoy music may also be better tuned into to these musical regularities in speech, and may thus more readily use these regularities to form musical predictions to inform their liking of repeated speech. This predicts that a change in liking with repetition may correlate with the vividness of the speech-to-song illusion.

Above we suggest that musical reward sensitivity may modulate the extent to which individuals extract latent musical patterns from speech and use these to make musical predictions. Individual differences in the tendency to make musical predictions when perceiving speech may also concern the perceptual weighting of lower- vs. higher-frequency portions of the spectrum during auditory processing. That people may vary in such frequency weighting is suggested by the Laurel–Yanny illusion, first discovered in 201814. In this illusion, a single noisy recorded spoken word is confidently perceived by some people as the word “Laurel”, and by others as the word “Yanny”. Inspecting the time-frequency spectrogram of this stimulus shows that there is an ambiguous formant in the middle of the frequency spectrum, that could be interpreted as either the second formant of Laurel or the third formant of Yanny. Thus, listeners who give more perceptual emphasis to the lower-frequency part of the spectrum tend to perceive “Laurel”, whereas listeners who give more weight to higher frequencies tend to perceive “Yanny”. The Laurel–Yanny illusion, therefore, can be used to test the idea that frequency weighting helps drive individual differences in the vividness of the speech-to-song illusion. Specifically, Laurel perceivers might weight low-frequency spectral information more strongly, including the fundamental frequency (f0) contours and low-frequency harmonics that convey information about pitch. A stronger pitch percept could facilitate the extraction of musical melodic structure latent in some spoken phrases and thus lead them to transform into song when the phrases are repeated. By this logic, Laurel perceivers should be more susceptible to the speech-to-song illusion than people who hear Yanny.

Motivated by the above considerations, the current study tested three hypotheses. First (Hypothesis 1), we hypothesized a change in liking would accompany the change in musicality ratings with phrase repetition in the speech-to-song illusion, and that changes in degree of liking would differ for illusion stimuli and control stimuli. Second (Hypothesis 2), we hypothesized that individuals with musical anhedonia would experience the song illusion less strongly than people with normal levels of musical enjoyment, and would also show less liking change accompanying the musicality change with phrase repetition. Third (Hypothesis 3), we hypothesized that Laurel perceivers would experience the song illusion more strongly than Yanny perceivers and show different patterns of liking change across phrase repetitions. Hypotheses 1 and 2 were preregistered at https://osf.io/52hws. Hypothesis 3 was added after preregistration as an exploratory hypothesis.

Methods

Participants

Previous research has shown that the effect of repetition on the speech-to-song illusion shows a large effect size (d = 0.72)15. We used this estimate to power the current study. Using G*Power 316, this estimate revealed that 18 participants would have 80% power to detect an effect of repetition on musicality. Given that musical anhedonia is estimated to occur in about 5% of the general population, we aimed to recruit at least 360 participants with the goal of identifying 18 individuals with musical anhedonia. A total of 447 individuals participated in the study: all were Prolific workers recruited from the United States (n = 342) and United Kingdom (n = 105) between the ages of 18–65 (see Table 1 for demographic information).

Procedure

The present study was conducted remotely at both Northeastern University as a part of an undergraduate research course and at Birkbeck, University of London. US participants completed the study on Qualtrics and UK participants on Gorilla. All experimental protocols were approved by Northeastern University IBB. Informed consent for the US-based participants was obtained using Northeastern University IRB #18-12-13. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. After consenting, participants were redirected to their respective online platform to do the study.

Participants were first presented with the ambiguous Laurel/Yanny stimulus, and reported which percept they heard (i.e., “Laurel” or “Yanny”). Following this, participants completed the main tasks of the study, which involved making four ratings of each spoken phrase in three separate blocks. Participants pressed a button to hear each phrase and had as much time as they needed to respond. The order of stimulus presentation was randomized for each participant during each of the three rating blocks.

In the first block participants heard each of the 48 illusion and control stimuli once (see Materials) and provided a liking rating for each on a scale from 1 to 10 (1= “I don’t enjoy this sound at all”, 10= “I enjoy this sound very much”). In the second block the 48 stimuli were presented again for musicality ratings. For each phrase, participants heard an initial presentation and rated the degree to which it sounded like speech or music on a scale from 1 to 10 (1 = “completely speech-like”, 10 = “completely song-like”). After this first musicality rating, participants pressed a button to hear six more presentations of the same phrase played back-to-back with no pauses in between each repetition. Participants then pressed a button to go to a page to hear the phrase one more time and then gave it a second musicality rating. This process was repeated for all 48 stimuli. In the third block, participants were then presented with the 48 stimuli one at a time and provided a post-repetition liking rating for each, using the same liking scale as before.

The study concluded with the completion of a four survey batteries: the Barcelona Music Reward Questionnaire (BMRQ)17, the Physical Anhedonia Scale (PAS)18, the Absorption in Music Scale (AIMS)19, the Goldsmiths Musical Sophistication Index (Gold-MSI)20, and a brief demographic questionnaire (see Materials).

Materials

Speech-to-song stimuli

Song illusion stimuli were short phrases (mean 5.5 syllables) from audiobooks in British or American English read by native speakers, used in numerous previous studies of the song illusion5,6,12,15,21,22,23,24. Across the studies, 24 of these stimuli have been shown to reliably undergo the speech-to-song illusion after repetition (“illusion” stimuli) while the remaining 24 continue to be perceived as speech (“control” stimuli). Illusion and control stimuli did not differ significantly in duration (mean 1.29 and 1.42 s, respectively), syllable rate (mean 5.13 and 5.00 syll/s, respectively), as reported in5.

Laurel–Yanny stimulus

The Laurel–Yanny Illusion is an auditory phenomenon that went viral in May 2018. It involves a sound recording of 0.9 s containing a single word that some people hear as the word “Laurel” while others distinctly hear “Yanny” (see14 for a spectrogram and discussion). The sound recording is available at https://osf.io/b29qz.

Psychometric survey battery

The Barcelona Music Reward Questionnaire (BMRQ) is a 20-item questionnaire which measures individual differences in music reward sensitivity (e.g., “I get emotional listening to certain pieces of music”). This scale measures five facets of reward derived from music: emotion evocation, sensorimotor, mood regulation, social reward, and music seeking (Mas-Herrero et al., 2012). Recently, a sixth factor—absorption—has been added on the extended Barcelona Music Reward Questionnaire (eBMRQ)25 by adding four questions from the Absorption in Music Scale (AIMS, see below).

The Revised Physical Anhedonia Scale (PAS) is a 61-item measure of generalized anhedonia, or the lack of pleasure in response to typically pleasurable experiences18. It consists of true or false questions which index whether the respondent finds certain experiences to be pleasant (e.g., “After a busy day, a slow walk has often felt relaxing.”). The PAS is often administered in tandem with the BMRQ to identify individuals with music-specific anhedonia17.

The Absorption in Music Scale is a 34-item self-report measure of a listeners’ ability and willingness to allow music to draw them into an emotional experience (Sandstrom and Russo, 2013). Relevant to the current study, many of the statements in the AIMS differ from those in the BMRQ, e.g., by focusing on how music alters conscious experience (e.g., “When listening to music I can lose all sense of time”) or on how sound engages attention (e.g., “I like to find patterns in everyday sounds”). Because the absorption subscale of the eBMRQ was made using four questions of this scale, we calculated eBMRQ scores in our sample by combining BMRQ scores with scores on those four AIMS items (these items are the last four statements in25.

Finally, the Goldsmiths Musical Sophistication Index (Gold-MSI) is a 38-item self-report measure of musical experience characterizing an individual’s singing ability, music perception skills, musical training, engagement with music, and emotional responses to music (each scored on a scale of 1–7), from which a general “Musical Sophistical Index” is computed (also on a scale of 1–7).

Analysis plan

Classifying individuals with musical anhedonia and matched controls

We defined individuals with musical anhedonia as those who scored below the tenth percentile on eBMRQ scores (i.e., self-reported minimal enjoyment of music) while also scoring less than one standard deviation above the sample’s mean on PAS scores (i.e., did not self-report high levels of generalized anhedonia)26. Because we wanted PAS scores to index general (and not music-specific) anhedonia, PAS scores were calculated after removing the eleven auditory-related items from the PAS (see SI). This resulted in those scoring below 69.6 on the eBMRQ and below 16.99 on the PAS (as higher PAS scores represent higher levels of generalized anhedonia) as being identified as the group of individuals with specific musical anhedonia. In total, we identified 22 individuals in this group from our sample, hereafter identified as “Individuals with Musical Anhedonia”. We then drew our matched controls from individuals who scored above the tenth percentile on the eBMRQ and met the PAS threshold. Specifically, the 22 individuals identified with musical anhedonia were matched with individuals without musical anhedonia using similar PAS scores (without auditory items) and musical training (as assessed by the perceptual abilities and musical training scores on the Gold-MSI) using the R package MatchIt27. This resulted in a total of 22 individuals with musical anhedonia and 22 controls included in our matched control analyses (see Table 1). Because we were missing responses to one item (out of seven) on the musical training scale (“I have had __ years of formal training on a musical instrument including voice during my lifetime”), we calculated participants’ score on this scale without this item. Further, for one item on this scale (“I engaged in regular daily practice of a musical instrument including voice for __ years”), one response value was missing (“10 or more”) in the Birkbeck sample. To maintain consistency in scoring across samples, this item was re-scored in the Northeastern sample (i.e., individuals who responded “10 or more” were scored a value of 6, instead of 7, to match the range of possible responses in the Birkbeck sample).

Testing the effects of repetition on musicality and liking ratings

The first goal of our analyses was to replicate the effect of repetition on musicality ratings; namely that ratings of musicality would increase post-repetition for the illusion stimuli. To this end, we modeled musicality ratings as a function of repetition (pre or post) using a linear mixed effects model using the lme4 package28 in R. We included an interaction term to test for differences in the effect of repetition on stimulus type (i.e., illusion or control). To test our first hypothesis that a change in liking would accompany the change in musicality ratings post-repetition, we ran a similar linear mixed effects model. Specifically, this model treated liking ratings as a function of repetition with an interaction term for stimulus type. We ran two additional exploratory analyses testing the relationship between the change in liking and musicality ratings pre- and post-repetition. The first was a linear mixed effects model which treated the change in liking ratings (post-repetition liking rating - pre-repetition liking rating) as a function of the change in musicality ratings (post-repetition musicality rating - pre-repetition musicality rating) per participant per stimulus. This model also included an interaction term for stimulus type. The second tested a simple linear correlation between the average change in liking ratings and musicality ratings per stimulus. All participants were included in these models.

We tested our second hypothesis that individuals with musical anhedonia may experience the speech-to-song illusion differently than matched controls using similar models to those described above with an additional interaction term for group membership (individuals with musical anhedonia vs. matched controls). We also tested identical models which instead used liking ratings as the outcome variable. These models included only the 44 participants we identified as having musical anhedonia or as matched controls.

Finally, we tested our exploratory hypothesis that Laurel perceivers may experience the speech-to-song illusion more strongly than Yanny perceivers. The models used to test this hypothesis were identical to those used to test differences in musicality and liking ratings for our first hypothesis, with an additional interaction term to represent which percept the individual heard (i.e., Laurel or Yanny). All participants were included in these models.

All reported models were constructed with maximal random effects. We specified random by-participant and stimulus random intercepts. We also included the effect of repetition, stimulus type, and their interaction as random by-participant effects and the effect of repetition as a random by-stimulus random effect. For all models, significance of fixed effects were approximated using the Satterthwaite method using the R package lmerTest29. All continuous measures were standardized before being entered into their respective models. All interaction terms were effect coded, such that the main effect of repetition represents the average effect across both stimulus types and that of stimulus type represents the average effect across pre- and post-repetition. For models with a third interaction term (i.e., the matched controls and Laurel–Yanny percept analyses), these main effects are also the average across both groups (either individuals with musical anhedonia and matched controls or Laurel- and Yanny-perceivers).

Results

The song illusion influences the effect of phrase repetition on liking

Figure 1 shows the overall average musicality and liking ratings before and after repetition separately for control and illusion stimuli. Across our entire sample (n = 447), we replicated the previous research on the song illusion using these stimuli: musicality ratings were significantly higher after compared to before repetition (β = 0.38, t(151) = 13.76, ηp² = 0.56, p < 0.001), illusion stimuli were rated as more musical (β = 0.41, t(51) = 5.39, ηp² = 0.36, p < 0.001), and there was a significant interaction between repetition and stimulus type (β = 0.33, t(54) = 7.93, ηp² = 0.54, p < 0.001), such that the effect of repetition on musicality ratings was stronger for the illusion stimuli (see Fig. 1A and B, and supplemental results).

The analogous mixed effects model for liking ratings revealed a significant main effect of repetition (β = − 0.08, t(243) = -3.56, ηp² = 0.05, p < 0.001), such that liking ratings showed a decrease after repetition. There was no significant main effect of stimulus type (β = 0.01, t(48) = 0.27, ηp² = 0.002, p = 0.79); however, there was a significant stimulus type by repetition interaction (β = 0.6, t(52) = 2.26, ηp² = 0.09, p = 0.03). Specifically, liking decreased less with repetition for illusion vs. control stimuli (see Fig. 1C, and supplemental results).

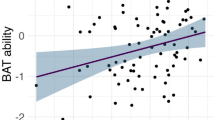

Finally, changes in liking ratings from pre- to post-repetition were associated with changes in musicality ratings from pre- to post-repetition within individuals (β = 0.03, t(350) = 3.1, ηp² = 0.03, p = 0.002). There was also no significant main effect of stimulus type (β = 0.05, t(63) = 1.68, ηp² = 0.04, p = 0.1), and this association between changes in ratings did not differ across stimulus types (interaction β = − 0.02, t(260) = 1.4, ηp² = 0.007, p = 0.16). Similarly, the mean change in liking ratings per stimulus was significantly positively correlated with the mean change in musicality ratings per stimulus (r(46) = 0.51, p < 0.001; see Fig. 1D).

Musicality (A) and liking (C) ratings before and after repetition for song illusion and control stimuli for the full participant sample (n = 447). Points show mean values and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Panel (B) shows a box-and-whisker plot of the change in musicality ratings (post- minus pre-repetition ratings) per stimulus for each participant. The solid line represents the median, with the box extending over the interquartile range. Points are slightly jittered along the x-axis for visualization. Panel (D) depicts the simple linear correlation between changes in musicality ratings and liking ratings (post- minus pre-repetition ratings) for each stimulus.

The speech-to-song illusion is preserved in musical anhedonia

We identified 22 individuals with musical anhedonia in our sample (4.9%) along with 22 matched controls. For musicality ratings (Fig. 2A), there was a significant stimulus type by repetition interaction (β = 0.38, t(56) = 4.98, ηp² = 0.31, p < 0.001), such that the effect of repetition was stronger for illusion compared to control stimuli. We also again identified main effects of both repetition (β = 0.38, t(48) = 5.12, ηp² = 0.35, p < 0.001) and stimulus type (β = 0.38, t(60) = 4.18, ηp² = 0.23, p < 0.001). Importantly, neither of these main effects nor the interaction between stimulus type and repetition differed between groups (group by repetition interaction: β = 0.17, t(42) = 1.18, ηp² = 0.03, p = 0.25; group by stimulus type interaction: β = − 0.07, t(43) = -0.82, ηp² = 0.02, p = 0.42; group by stimulus type by repetition interaction: β = − 0.1, t(47) = -0.81, ηp² = 0.01, p = 0.42). There was no significant between-group difference in the size of the change in ratings with repetition. The main effect of group membership on musicality ratings was marginal (β = 0.32, t(60) = 1.9, ηp² = 0.08, p = 0.06). (For numerical mean musicality values plotted in Fig. 2A, see Table S1.)

Motivated by this marginal effect, we examined a measure called the “musical prior” recently introduced into song illusion research12, meant to represent a participant’s overall tendency to perceive the musical qualities of speech. The musical prior is computed as each participant’s average musicality rating of all illusion and control stimuli across all repetitions. In the current study, each stimulus was given a first musicality rating before repetition and a second rating after repetition, so each participant’s musical prior was computed from 48 stimuli x 2 ratings = 96 values. Individuals with musical anhedonia had a significantly lower musical prior than matched controls (median (IQR) of 2.11 (2.24) and 2.66 (2.49), respectively; z = 1.77, p = 0.038, one-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test, Figure S1). This confirms that the individuals with musical anhedonia showed a lower baseline musicality rating than controls, but this did not interact with repetition. In other words, individuals with musical anhedonia perceived the illusion as vividly as matched controls.

Broadening the analysis to include our full sample of 447 participants, we computed a measure of “illusion vividness” motivated by the stronger effect of repetition on musicality ratings for illusion vs. control stimuli (cf. the stimulus by repetition interactions reported above). Specifically, for each participant we computed their average increase in musicality rating with repetition for illusion stimuli minus their average increase in musicality with repetition for control stimuli. We found that across our entire sample this measure of illusion vividness did not show a significant relationship to BMRQ score (Figure S2). Surprisingly, however, illusion vividness had a small but significant negative association with AIMS score (Figure S3).

For liking ratings (Fig. 2B), our model did not detect a significant main effect of stimulus type (β = − 0.0008, t(52) = -0.01, ηp² = 0.000002, p = 0.99), repetition ( = -0.04, t(42) = − 0.63, ηp² = 0.009, p = 0.53), or a stimulus type by repetition interaction (β = −0.01, t(821) = − 0.27, ηp² = 0.00009, p = 0.79). Further, group membership did not interact with repetition (β = − 0.04, t(42) = -0.3, ηp² = 0.002, p = 0.76) or stimulus type (β = − 0.06, t(42) = -0.93, ηp² = 0.02, p = 0.36), and there was no significant three-way interaction (β = 0.05, t(908) = 0.58, ηp² = 0.0004, p = 0.56). There was, however, a main effect of group membership (β = − 0.45, t(42) = 2.54, ηp² = 0.13, p = 0.01): overall, individuals with musical anhedonia liked the stimuli less than matched controls.

Musicality (A) and liking (B) ratings before and after repetition for song illusion and control stimuli for individuals with musical anhedonia and matched controls. Points show mean values and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. (For Liking ratings, note the different y-axis scale compared to Fig. 1C due to low ratings given by individuals with musical anhedonia.)

Laurel-perceivers experience a stronger speech-to-song illusion than Yanny-perceivers

In our sample, 179 participants perceived Laurel and 268 perceived Yanny. For musicality ratings (Fig. 3A), there was no significant main effect of percept (β = 0.08, t(445) = 1.55, ηp² = 0.005, p = 0.12). As before, there were significant main effects on musicality ratings of both repetition (β = 0.4, t(152) = 14.3, ηp² = 0.57, p < 0.001) and stimulus type (β = 0.42, t(52) = 5.44, ηp² = 0.36, p < 0.001). In line with our predictions, the effect of repetition was stronger for Laurel-perceivers (percept by repetition interaction: β = 0.16, t(445) = 3.9, ηp² = 0.03, p < 0.001). The effect of stimulus type, however, was similar across groups (percept by stimulus type interaction: β = 0.04, t(445) = 1.1, ηp² = 0.003, p = 0.27). This model again revealed a significant stimulus type by repetition interaction (β = 0.34, t(55) = 7.98, ηp² = 0.54, p < 0.001) as discussed above. There was no significant three-way interaction between percept, stimulus type, and repetition (β = 0.04, t(445) = 0.97, ηp² = 0.002, p = 0.33).

Figure 3A shows that on average, Laurel and Yanny perceivers showed similar initial musicality ratings for both illusion and control stimuli but Laurel perceivers showed a larger increase in musicality rating with repetition than Yanny perceivers. (For illusion and control stimuli, Laurel listeners’ mean post-repetition ratings were 55% and 33% greater than their mean pre-repetition ratings respectively, vs. 41% and 17% for Yanny listeners, see Table S2.) When individual illusion and control stimuli were examined for their average increase in musicality rating with repetition, Laurel perceivers showed a numerically larger increase than Yanny perceivers across all 48 illusion and control stimuli (Figure S4), a pattern extremely unlikely to happen by chance (sign test, p < 10–14). These song illusion differences between Laurel and Yanny perceivers stand in contrast to their similar musical reward sensitivity (mean (SD) BMRQ scores: 76.27 (13.47) and 77.93 (12.72) respectively, t(367) = -1.3, p = 0.19),tendency for absorption in music (mean (SD) AIMS scores 110.15 (29.59) and 109.36 (29.4) respectively, t(380) = 0.28, p = 0.78), musical training (mean (SD) Gold-MSI musical training scores 2.41 (1.33) and 2.5 (1.41), t(396 − 0.69, p = 0.49), and musical priors (Laurel median (IQR) = 2.97 (1.93), Yanny = 2.89 (2.08), Wilcoxon rank sum: z = 0.45, p = 0.65).

Turning to liking ratings (Fig. 3B), there was no main effect of percept (Laurel vs. Yanny) (β = 0.07, t(445) = 1.18, ηp² = 0.003, p = 0.24). Again, there was a significant effect of repetition on liking ratings (β = − 0.07, t(251) = -3.18, ηp² = 0.04, p = 0.002), and no effect of stimulus type (β = 0.02, t(48) = 0.3, ηp² = 0.002, p = 0.76). While there was no stimulus type by percept interaction (β = 0.01, t(455) = 0.72, ηp² = 0.001, p = 0.47), the interaction between percept heard and repetition on liking ratings was marginal (β = 0.07, t(445) = 1.92, ηp² = 0.008, p = 0.06). Again, this model revealed a significant stimulus type by repetition interaction (β = 0.06, t(53) = 2.3, ηp² = 0.09, p = 0.03), as described above. Finally, there was no significant three-way interaction between percept, stimulus type, and repetition (β = 0.01, t(902) = 0.45, ηp² = 0.0002, p = 0.65).

Musicality (A) and liking (B) ratings before and after repetition for song illusion and control stimuli for Laurel and Yanny perceivers. Points show mean values and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. (For Liking ratings, note the different y-axis scale compared to Figs. 1C and 2B due to the different ranges of values.)

Discussion

The speech-to-song illusion is much stronger for some listeners than others, and much remains to be understood about the factors underlying this variance. Here we combine liking and musicality ratings with a test of internal weighting of high vs. low frequency cues as assessed by the Laurel–Yanny illusion. We find that the intensity of the speech-to-song transformation and (marginally) changes in liking with repetition are, in part, explained by variability in the perceptual weighting of low frequencies in speech. We found support for Hypothesis 1, in that a change in liking accompanied the change in musicality ratings in the speech-to-song illusion. Hypothesis 2 was partly confirmed and partly refuted, in the sense that individuals with musical anhedonia did show less liking overall, but this was not accompanied by change in musicality ratings with speech repetition. We found partial support for Hypothesis 3: Laurel perceivers showed a significantly larger increase in musicality rating with repetition than Yanny perceivers, but the interaction between percept heard and repetition on liking ratings was marginal and had a very small effect size.

We replicated the speech-to-song illusion in that musicality ratings of spoken phrases increased after repetition, with a much stronger increase for illusion than for control stimuli. In contrast to musicality ratings, however, liking ratings generally decreased with repetition. Thus, an increase in musicality is not coupled with an increase in liking overall. However, illusion stimuli show less reduction in liking ratings than control stimuli. This may be explained by a switch in covert attention towards the more melodic properties of speech following repetition, especially for the illusion stimuli. Since unfamiliar melodies lead to increased liking with exposure8,30, and the illusion stimuli feature melodic structure to a greater extent than the control stimuli5, the illusion stimuli may have been more conducive to melodic listening via greater perceptual weighting of –– and/or predictions for –– patterns in lower frequencies, thus leading to higher liking after repetition.

Another explanation for why illusion stimuli show less decrease in liking with repetition is that the perceptual transformation decreases habituation. Prior research suggests that although exposure can enhance liking in complex stimuli8, exposure can also lead to decreases in liking due to habituation31. The speech-to-song illusion could decrease habituation by bringing to light musical characteristics of the stimuli which were not previously evident. These decreased habituation and increased musical prediction explanations are not mutually exclusive, and both could be contributing to the lessened drop in liking with repetition for speech stimuli which transform into song. Acoustic cues for musicality, e.g. within-syllable pitch slope, may also drive habituation or satiation across repetitions. It is possible that stimuli not perceived as musical are quicker to induce boredom with repetition (i.e., reward habituation). Future studies could evaluate this proposed mechanism using neural markers of habituation. Previous work on the mere exposure effect / reward habituation has shown an inverted U-curve (quadratic effect) over time with more simple melodies32, and found that individuals with musical anhedonia showed an apex in liking at around 8 repetitions (for Bohlen-Pierce scale melodies)8. It is thus possible that we are only capturing the latter half of the mere-exposure inverted-U curve. In other words, because participants provided liking ratings only after the entire repetition block, the present results do not capture the trajectory of liking across different amounts of exposure. To our knowledge, only one study has evaluated the mere-exposure effect on speech excerpts33. Future studies could evaluate such trajectories by having participants provide liking ratings after each presentation of the stimuli. Participants also heard a total of 384 stimuli during the study and such extensive exposure to relatively simple speech stimuli may help to explain the overall decrease in liking ratings.

At present, our data are unable to disentangle whether the changes in liking ratings actually represent a perceptual shift, or effects of habituation and or saturation. The correlation between musicality change and liking change suggests an actual perceptual shift. Perceptual differences could also explain some of the liking or musicality rating differences between individuals with musical anhedonia and controls, since these groups were only matched on self-reported measures of musical training and perceptual abilities (Gold-MSI) and not on objective measures of music perception abilities (e.g. using the Musical Ear Test or the Montreal Battery for Evaluation of Amusia). Future studies could also manipulate the actual speech-to-song stimuli over time, such as by changing the within-syllable pitch slope across repetitions to see whether this influences the speech-to-song transition or changes in liking with repetition.

One observation is that non-illusion stimuli are, after repetition, judged as musical as the illusion stimuli are before repetition. This supports a more general implication: that the tendency of phrases to start sounding like song after repetition lies along a continuum, rather than being dichotomous (illusion “vs.” control phrases). One hypothesis that could explain how non-illusion stimuli, after repetition, can become as musical-sounding as illusion stimuli before repetition is that by hearing so many examples of phrases that do transform in a single experiment session, participants start to hear all phrases differently. While we cannot directly test this hypothesis in the present study, previous work has shown that, upon returning for a second session, participants reported a stronger illusion after repetitions of novel stimuli than they did during the first session6. Though the effect was small, the finding suggests that task-related knowledge, e.g. the perceptual weighting bias of Laurel perceivers observed in the present study, can be learned and transferred to novel phrases (as in the case of the present control stimuli).

Individuals with musical anhedonia showed a robust speech-to-song illusion as evidenced by increased musicality ratings following repetition, especially for illusion stimuli. They showed a lower musicality rating over all stimuli (illusion and control) than matched controls, as reflected by their lower musical prior–a participant-level measure of a perceptual bias towards the musical qualities of speech. They also showed lower liking for all stimuli; however this did not interact with repetition or stimulus type. The relatively large effect size of the between-group difference in liking ratings (Fig. 2B) is interesting especially when considered alongside the relatively small effect size of the musical prior. Other work has shown that patterns of liking rating become more distinct between individuals with musical anhedonia and controls with repeated exposure8, such that while controls increase their liking ratings for unfamiliar music with repeated exposure, individuals with musical anhedonia show less of an increase; in fact their liking ratings decrease after only very little exposure (resulting in an inverse U-shaped relationship between exposure and liking even for very unfamiliar music). In the present context, we see for the first time that participants with musical anhedonia have less of a perceptual bias to hear musical qualities in speech overall before any repetition within our experiment. Since they also have a lower reward sensitivity to musical sounds (by definition)26, their continued low liking rating persists and is less influenced by repetition, resulting in much lower liking ratings than controls. This could explain the relatively large size of the effect of musical anhedonia on liking.

While the overall lower liking and musicality ratings of illusion and control phrases showed effects of musical anhedonia, illusion vividness did not differ between individuals with musical anhedonia and matched controls. Presumably individuals with musical anhedonia have no reason to intentionally seek out musical patterns in non-musical stimuli, suggesting that increases in musicality perception with repetition in song illusion stimuli are involuntary rather than being under conscious control. More generally, the current results show a dissociation between musical perception and emotional sensitivity to music. The perceptual continuum between speech and music, as probed by the speech-to-song illusion, seems to be independent from emotional evaluation or appraisal as captured by the continuum of musical reward sensitivity (cf. Fig S2). In this regard our findings align with case studies dissociating music perception abilities from emotional responses to music, as described in research studies34, and in more informal case descriptions in Oliver Sacks’ chapter “Seduction and Indifference” from Musicophilia35.

One type of individual difference that does seem to influence the song illusion is the perceptual weighting of high vs. low frequency information in speech: Listeners who perceived “Laurel” in the ambiguous Laurel/Yanny stimulus perceived the speech-to-song illusion more vividly than those who perceived “Yanny”. This interaction effect between percept (“Laurel” vs. “Yanny” perceivers) and repetition (pre vs. post repetition) on musicality ratings is subtle, but highly significant given our adequate sample size. Initially added as an exploratory third hypothesis in our current study, we now believe that the Laurel/Yanny stimulus may offer significant insights into Bayesian models of predictive coding, which have been implicated in music perception10 as well as in speech perception11. In the context of speech perception, Laurel perceivers may have an attentional bias favoring low-frequency information. Low-frequency information includes the fundamental frequency, whose patterning over time helps distinguish spoken stimuli that do and do not transform into song after repetition5. Thus “Laurel” perceivers may be better able to detect and predict musical melodic structure latent within certain spoken phrases. In addition, research has consistently singled out low-frequency sounds as having a disproportionate influence on rhythmic timing information important for music perception. Compared to high-frequency sounds (e.g., greater than 466.2 Hz ), low-frequency sounds (e.g., 130–196.0 Hz) more readily entrain motor and neural activity to the musical beat36,37 and support increased sensitivity to temporal deviations in sequences of tones36. Prior work finds that illusion phrases have more temporally regular syllabic rhythms than control phrases5, and thus attention to low frequencies may enhance the detection of latent musical rhythmic structure in spoken phrases. Marginally higher post-repetition liking ratings for “Laurel” compared to “Yanny” perceivers may suggest that the greater perceived musicality of these stimuli of this group attenuates the negative effects of repetition on preference, potentially through orienting attention to these latent musical qualities. If high salience of low frequencies helps drive the vividness of the speech-to-song illusion, then priming attention towards low frequencies and away from high frequencies could facilitate the speech-to-song illusion. This could be tested in future research by investigating whether presenting stimuli in the frequency range of the F0 of the speech-to-song illusion stimuli prior to each stimulus enhances the speed or extent of the speech-to-song transition.

The present study shows that individual differences in speech perception, as tested using the Laurel–Yanny illusion, influence the vividness of the speech-to-song illusion while musical anhedonia does not. Rather than treating different illusions as separate curiosities, we have studied their relations as a window into theoretical debates surrounding models of speech perception. Future work should check that a person’s initial perception of the original Laurel vs. Yanny stimulus does in fact relate to how they weight different frequencies in speech, using tasks that aim to measure the perceptual weights assigned to different frequency bands during speech perception38,39,40,41. If the relationship is confirmed, our findings suggest that future studies could use the Laurel–Yanny illusion as an efficient way to further explore the consequences of different frequency weighting for the perception of speech and music.

Data availability

Anonymized data are available on https://www.doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/7DGB2.

References

Albouy, P. et al. Spectro-temporal acoustical markers differentiate speech from song across cultures. Nat. Commun. 15(1), 4835. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49040-3 (2024).

Ozaki, Y., Tierney, A., Pfordresher, P.Q., et al. Globally, songs and instrumental melodies are slower and higher and use more stable pitches than speech: A registered report. Sci. Adv. 10(20), eadm9797 (2024).

Deutsch, D., Henthorn, T. & Lapidis, R. Illusory transformation from speech to song. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 129(4), 2245–2252. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3562174 (2011).

Falk, S., Rathcke, T. & Dalla Bella, S. When speech sounds like music. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 40(4), 1491–1506. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036858 (2014).

Tierney, A., Patel, A. D. & Breen, M. Acoustic foundations of the speech-to-song illusion. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 147(6), 888–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000455 (2018a).

Kubit, B. M., Deng, C., Tierney, A. & Margulis, E. H. Rapid learning and long-term memory in the speech-to-song illusion. Music Perception: Interdiscip. J. 41 (5), 348–359. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2024.41.5.348 (2024).

Zajonc, R. B. Attitudinal effects of Mere exposure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 9 (2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025848 (1968).

Kathios, N., Sachs, M. E., Zhang, E., Ou, Y. & Loui, P. Generating new musical preferences from multilevel mapping of predictions to reward. Psychol. Sci. 35(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976231214185 (2024).

Loui, P., Wessel, D. L. & Kam, C. L. H. Humans rapidly learn grammatical structure in a new musical scale. Music Percept. 27 (5), 377–388. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2010.27.5.377 (2010).

Vuust, P., Heggli, O. A., Friston, K. J. & Kringelbach, M. L. Music in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 23(5), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-022-00578-5 (2022).

Davis, M. H. & Sohoglu, E. Three functions of prediction error for bayesian inference in speech perception. In D. Poeppel, G. R. Mangun, & M. S. Gazzaniga (Eds.), The Cognitive Neurosciences (pp. 177–189). MIT Press (2020).

Tierney, A., Patel, A. D., Jasmin, K. & Breen, M. Individual differences in perception of the speech-to-song illusion are linked to musical aptitude but not musical training. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 47 (12), 1681–1697. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000968 (2021).

Deutsch, D. Musical Illusions and Phantom Words: How Music and Speech Unlock Mysteries of the Brain (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Pressnitzer, D., Graves, J., Chambers, C., De Gardelle, V. & Egré, P. Auditory perception: Laurel and Yanny together at last. Curr. Biol. 28(13), R739–R741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.06.002 (2018).

Chen, Y., Tierney, A. & Pfordresher, P. Q. Speech-to-song transformation in perception and production. Cognition 254, 105933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2024.105933 (2025).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146 (2007).

Mas-Herrero, E., Marco-Pallares, J., Lorenzo-Seva, U., Zatorre, R. J. & Rodriguez-Fornells, A. Individual differences in music reward experiences. Music Percept. 31(2), 118–138. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2013.31.2.118 (2013).

Chapman, L. J. & Raulin, M. L. Scales for physical and social anhedonia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 85(4), 374–382 (1976).

Sandstrom, G. M. & Russo, F. A. Absorption in music: development of a scale to identify individuals with strong emotional responses to music. Psychol. Music 41(2) (2011).

Müllensiefen, D., Gingras, B., Musil, J. & Stewart, L. The musicality of non-musicians: An index for assessing musical sophistication in the general population. PLoS ONE 9(2), e89642. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089642 (2014).

Graber, E., Simchy-Gross, R. & Margulis, E. H. Musical and linguistic listening modes in the speech-to-song illusion bias timing perception and absolute pitch memory. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 142(6), 3593–3602. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.5016806 (2017).

Tierney, A., Dick, F., Deutsch, D. & Sereno, M. Speech versus song: Multiple Pitch-Sensitive areas revealed by a naturally occurring musical illusion. Cereb. Cortex 23(2), 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhs003 (2013).

Tierney, A., Patel, A. D. & Breen, M. Repetition enhances the musicality of speech and tone stimuli to similar degrees. Music Percept. 35(5), 573–578. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2018.35.5.573 (2018b).

Nederlanden, V. B. D., Hannon, C. M., Snyder, J. S. & E. E., & Finding the music of speech: Musical knowledge influences pitch processing in speech. Cognition 143, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2015.06.015 (2015).

Cardona, G., Ferreri, L., Lorenzo-Seva, U., Russo, F. A. & Rodriguez-Fornells, A. The forgotten role of absorption in music reward. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14790 (2022).

Kathios, N., Patel, A. D. & Loui, P. Musical anhedonia, timbre, and the rewards of music listening. Cognition 243, 105672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2023.105672 (2024).

Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G. & Stuart, E. A. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J. Stat. Softw. 42(8) (2011).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear Mixed-Effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67(1). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. Tests in linear mixed effects models [R package lmerTest version 2.0–36]. Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) (2017).

Mungan, E., Akan, M. & Bilge, M. T. Tracking familiarity, recognition, and liking increases with repeated exposures to nontonal music: Revisiting MEE-Revisited. New Ideas Psychol. 54, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2019.02.002 (2019).

Ueda, K., Sekoguchi, T. & Yanagisawa, H. How predictability affects habituation to novelty. PLOS ONE. 16 (6), e0237278. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237278 (2021).

Tan, S. L., Spackman, M. P. & Peaslee, C. L. The effects of repeated exposure on liking and judgment of intact and patchwork compositions. Music Percept. 23 (5), 407–421 (2006).

Williams, S. M. Repeated exposure and the attractiveness of synthetic speech: an inverted-U relationship. Curr. Psychol. 6(2), 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02686619 (1987).

Peretz, I., Gagnon, L. & Bouchard, B. Music and emotion: Perceptual determinants, immediacy, and isolation after brain damage. Cognition 68(2), 111–141 (1998).

Sacks, O. Musicophilia: Tales of music and the brain (Vintage, 2008).

Hove, M. J., Marie, C., Bruce, I. C. & Trainor, L. J. Superior time perception for lower musical pitch explains why bass-ranged instruments lay down musical rhythms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111(28), 10383–10388. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1402039111 (2014).

Lenc, T., Keller, P. E., Varlet, M. & Nozaradan, S. Neural tracking of the musical beat is enhanced by low-frequency sounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1801421115 (2018).

Bernstein, J. G. W., Venezia, J. H. & Grant, K. W. Auditory and auditory-visual frequency-band importance functions for consonant recognition. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 147(5), 3712–3727. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0001301 (2020).

Gilbert, G. & Micheyl, C. Influence of competing multi-talker babble on frequency-importance functions for speech measured using a correlational approach. Acta Acustica. 91, 145–154 (2005).

Coffey, E. B. J., Colagrosso, E. M. G., Lehmann, A., Schönwiesner, M. & Zatorre, R. J. Individual differences in the frequency-following response: Relation to pitch perception. PLOS ONE 11(3), e0152374. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152374 (2016).

Sladen, D. P. & Ricketts, T. A. Frequency importance functions in quiet and noise for adults with cochlear implants. Am. J. Audiol. 24(4), 477–486. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_AJA-15-0023 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank the students of the Spring 2024 Music and the Brain course at Northeastern University for piloting the study. Supported by NIH R01AG078376, NIH R21AG075232, NSF-BCS 2240330 and NSF-CAREER 1945436 to PL. We also thank Andrew Oxenham for discussions of the Laurel Yanny illusion and perceptual weighting of higher vs. lower frequencies in speech.

Funding

Supported by NIH R01AG078376, NIH R21AG075232, NSF-BCS 2240330 and NSF-CAREER 1945436 to PL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in the design and execution of the study. NK, BK, AT, AP, and PL wrote the main manuscript text. NG, JE, EZ, and AS collected the data. NK prepared the main figures and tables with input from BK, AT, AP, and PL. AT and AP prepared the supplementary figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kathios, N., Kubit, B.M., Grout, N. et al. Laurel–Yanny percept affects the speech-to-song illusion, but musical anhedonia does not. Sci Rep 15, 30325 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15592-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15592-7