Abstract

Accurate determination of fluid saturation and organic matter content is essential for the characterization and assessment of organic-rich source rock reserves. However, few advanced techniques are available to precisely identify fluid-porous systems and define prospective deposits throughout various stages of field exploration. This paper explores the combined application of two widely utilized methods — low-field nuclear magnetic resonance relaxometry (NMR) and Rock-Eval pyrolysis — using an expanded suite of rock samples. The primary objective of this study is to establish optimized workflows that offer a more comprehensive quantification of liquid saturation with heavy to mobile hydrocarbons compared to standard industry practices and help to identify the fluid volumetric model of the target formation. Main findings demonstrate correlations between NMR-obtained data, mineral composition of the rock and organic matter components by Rock-Eval pyrolysis. The detailed analysis and comparison of experimental results is performed using the manual interpretation of NMR T1-T2 maps and Mutual Information regression approach that processed the NMR T2 spectrum. The research lays the groundwork for NMR-based Machine Learning-assisted in situ characterization of mineral components (quartz and clays), crude oil maturity and volume for shale deposits, along with determining the ratio between bound and mobile oil components.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Characterization of shale reservoirs requires a careful selection of special core analysis tests (SCAL) to cost-effectively derive a petrophysical model. Typically, shale petrophysical model comprises mineralogy, porosity, permeability, fluid types, saturation, and organic content. However, unlike conventional reservoirs that accumulate migrated hydrocarbons (HC), shale oil and gas are generated during kerogen maturation. Increased kerogen maturity leads to the development of organic porosity filled with saturated hydrocarbons and viscous resin-asphaltene components in free and adsorbed states1,2,3,4. Consequently, shales predominantly consist of nano- and micrometer-sized pores, including inorganic and organic pores within kerogen5 and can be treated both as reservoirs and organic-rich source rocks.

As such, fluid saturation typing via routine and SCAL experiments has been used with varying success, particularly when it comes to the characterization of saturation in organic pores by solvents, which are either partially or completely removed with lighter HC fractions, resulting in incorrect HC quantification and destruction of samples6,7. Rock-Eval pyrolysis (REP) provides far better volumetric estimates of HC components and organic matter (OM) maturity, but during the sample preparation, the rock sample is ground into powder, which affects the HC content: free light hydrocarbons evaporate through the newly opened porosity and result in S1 values decrease8.

To this end, low-field NMR relaxometry has been extensively used to study shale deposits, as a non-invasive alternative for fluid typing, pore size distribution (PSD) studies, wettability estimates and even for estimation of HC viscosity9,10,11. Despite successful applications, challenges persist in resolving overlapping NMR signals from heavy oils, nano porous organic matter (OM), and clay-bound water in shales. Partial separation of hydrogen signal in such systems has been achieved using 2D logging by combining T₂ measurements with T₁ and self-diffusion measurements, enabling differentiation in higher-dimensional space.

Reconstruction of complete signals from heavy, solid-like organic matter is hard to achieve with NMR logging tools as they are limited by their magnetic field strength (400–600 gauss) and corresponding Larmor frequency (~ 2 MHz)12,13,14. Although, benchtop NMR setups can operate at higher frequencies (10–23 MHz) and provide better hydrocarbon resolution, at this time such technology cannot be extended to well-logging applications. However, low-field NMR instruments operating at 2 MHz may have limitations in accurately characterizing all fluid components within complex shale matrices: hydrogen signal from heavy hydrocarbons and bound water can lead to overestimation of movable fluids if relying solely on T2 distribution analysis. Two-dimensional NMR methods, such as T1-T2 correlation or diffusion-relaxation experiments, resolve overlapping signals and improve the accuracy of fluid typing and mobility assessment in shale samples. Combination of NMR analysis with other techniques of geochemical and petrophysical analyses can provide valuable insights into quantification of fluids, especially when differentiating between bound water, movable water, and hydrocarbons, and correlate pore structure characteristics with oil mobility15.

Therefore, in SCAL for shale characterization, custom workflows combining NMR tests with other petrophysical tests are constantly being developed. For instance, Rylander et al.16 utilized mercury injection capillary pressure (MICP) method and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to relate HC saturations with pore and throat distributions of Eagle Ford shales to calibrate the T2 volumetric model and determine the cut-off values separating irreducible and movable fluids. Westphal et al.17 combined NMR and computed tomography to improve the estimate of free fluids, as well as to describe the pore connectivity in shale rocks. Unified schemes for classifying fluid types in oil shales constructing a void space model for low-porous and low-permeability sediments were proposed by Rylander et al.10 and Jian-Ping et al.18.

The Rock-Eval pyrolysis (REP) is also employed with NMR relaxometry to improve typing and quantification of organic matter and its maturity degree. Khatibi et al.19used customized 22 MHz benchtop NMR to complement Rock-Eval pyrolysis and vitrinite reflectance methods in characterizing the Bakken Formation samples with different OM maturity. Li et al.4 introduced a workflow combining 21.36 MHz-NMR and REP data for Shahejie Formation to successfully resolve signals of free oil, adsorbed oil, and heavy HC components derived from T1-T2 maps and corresponding geochemical parameters. Birdwell and Washburn20 and Romero-Sarmiento1 reported on successful application of 2 MHz NMR in the field of fluid typing in organic-rich source rocks.

Bazhenov shale formation has been a subject of intensive research for the past 20 years21,22,23. In our earlier works, we reported results on geochemical and petrophysical studies of the Bazhenov Formation obtained on limited core collections24,25. Here we continue the research and report on the findings of an extensive study on fluid saturation in clay-containing, organic-rich layers. The aims of the present study are threefold. First, we focus on optimizing the SCAL experimental pipeline for Bazhenov shale samples by designing two different workflows to compare how the order of sample desaturation, re-saturation, and drying impacts the estimation of hydrocarbon saturations or ‘cutoffs’ from NMR T2 and T1-T2 tests. Second, in addition to routine core analysis (RCA), supporting tests from X-ray diffractometry (XRD), and Rock-Eval pyrolysis measurements facilitated analysis of mineral species and OM properties correlation with HC content by T1-T2 maps, and NMR T2 distributions. Finally, from the obtained generalizations, we derive an improved fluid volumetric model using both manual interpretation and data-driven processing of experimental results. To this end, 20 shale samples (core plugs and duplicate core fragments) were tested in this work.

Materials

Geological settings: target oilfield

The Bazhenov Formation (BF) is one of the most prominent organic-rich source rock formations worldwide in terms of area and hydrocarbon reserves, which covers more than one million square kilometers area in the West Siberian Petroleum Basin, Russia21,22,23. Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous Bazhenov oil shale formation was formed mostly in marine anoxic conditions. BF occupies most of the West Siberian Petroleum Basin at the depth of 2000–3000 m with a thickness of 15–60 m and organic matter content up to 25 wt% 26. The main rock types are composed of silica, carbonates (calcite and dolomite), clay minerals (mostly kaolinite and illite), and organic matter27. Petrophysical properties of the rock complicate the standard core analysis due to extremely low permeability (< 1 mD) and low open porosity values (< 3%)28. One of the most general patterns for the Bazhenov Formation is a decreasing organic matter content from the center to the periphery of the basin. Heterogeneity along the section is reflected in the differentiation of the formation into the lower and upper parts according to lithological and geochemical properties. Thus, the Upper BF contains more carbonate and clay components, significantly higher organic matter content and characterized by an increased content of pyrite, while the Lower part is predominantly siliceous, with a reduced content of organic matter (5–10 wt%).

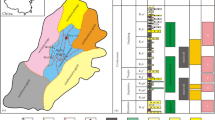

In the current study, the rock samples were probed from the SN3 well that is located in the Middle Ob region of Western Siberia (Fig. 1). Samples were selected throughout the section from the most representative intervals identified by logging data and core studies (XRF, XRD, Rock-Eval pyrolysis). The target well section was subdivided into 5 members: I and II members correspond to Lower BF, the Upper BF is subdivided into III, IV and V members (Fig. 1). The member V is characterized by high content of pyrite in organic-rich siliceous claystone. The member IV is distinguished by the presence of biogenic calcite and composed predominantly of carbonate, siliceous, and clayey components with high kerogen (up to 15–20 wt%) and pyrite content. Clayey-siliceous mudstones from the member III are the most organic-rich rocks in the selected interval with organic matter amount up to 20–30 wt%. The member II, the uppermost member of the Lower part of BF, is represented by siliceous and clayey-siliceous rocks with decreased organic matter content. The members I and II contain a significant amount of radiolarite interlayers. It is correlated with increased reservoir properties due to the low kerogen content (< 5 wt%) and mineral composition, making it the most interesting part of the BF in terms of mobile hydrocarbon production.

The studied well is characterized by early-mature organic matter. High content of organic matter with a fairly large amount of heavy hydrocarbons is typical for low-mature Bazhenov Formation interval24. With underdeveloped kerogen porosity at early maturity degree, the most potentially productive rocks are associated with the radiolarite intervals in the members I and II.

Core sample collection

The collection of rock samples consisted of 20 core plugs (Ø30 mm) (Table 1). Core fragments were used as substitutes for XRD and Rock-Eval analysis in intervals where insufficient core material was available to produce cylindrical plugs. All core samples were recovered from the same well (SN3). The core plugs were drilled using a proprietary diamond cutter equipped with an air-cooling system. Initial porosity and permeability measurements were conducted on core plugs using an automated gas porosimeter (PIK-PP) in as-is state.

Methods

Core analysis workflow

Due to the limited core material, all core plugs were divided and subjected to two different workflows: A and B; the core fragments were analyzed separately (Table 2). The primary difference between these workflows was the order of core saturation and handling procedure and NMR measurements as shown in Fig. 2. The FFI workflow (A) was designed to preserve initial saturation in shale samples using desaturation and re-saturation in a least destructive way, to minimize the fracturing of the rock matrix due to clay swelling. It involves three main steps: NMR measurement in the as-is state (Sas−is), the decane-saturated (Sdec), and the dried state (Sdry). Additionally, samples were centrifuged to remove mobile fluids and determine their residual saturation (Sirr).

Workflow B, in contrast, employs preliminary controlled vacuum-drying to remove free fluids (FFI) and partially the clay-bound (CBW) and capillary bound fluids (BVI) due to evaporation of light HCs, respectively, before the saturation stage. Workflow B is commonly used in petrophysical analysis of oil-bearing and source rocks. However, high temperature drying can deform clay minerals, compromising sample integrity when fluids are later introduced under high pressure. In our study, some samples in Workflow B were damaged. To ensure accuracy, we monitored sample volume at each stage and calculated porosity using the measured values.

Core fragments were tested by NMR, Rock-Eval pyrolysis, and XRF analysis to support the analysis of core plugs, particularly in as-is states.

Rock-Eval pyrolysis (REP)

The Rock-Eval pyrolysis was conducted using HAWK RW pyrolyzer (Wildcat Technologies) operating in the Bulk Rock temperature mode29,30. A rock sample of 30–50 mg mass (for rock enriched in organic matter) was crushed to 60 mesh. The analysis consisted of two stages: pyrolysis and oxidation. The pyrolysis stage began at room temperature and heated up to 650 °C at a rate of 25 °C per minute, with two temperature steps: at 90 °C (S0 peak, representing gaseous hydrocarbons) and at 350 °C (S1 peak, representing light hydrocarbons), all under a helium flow. After the furnace cooled, the oxidation stage started with heating in a pure air flow up to 750 °C at a rate of 25 °C per minute.

The interpretation of results was based on the principles of pyrolytic data analysis for shale rock31. The output pyrolysis parameters are S0 (gaseous HC), S1 (light HC), and S2 (products of kerogen treatment and heavy HC fractions) measured in mg HC/g-rock, as well as the amount of CO and CO2 released during pyrolysis and oxidation of organic matter (S3 and S4). The content of generative (GOC) and non-generative (NGOC) organic carbon, and the total amount of organic carbon content (TOC) are calculated based on these parameters (Eqs. 1–3). The temperature Tmax is determined at the maximum of S2 peak. The processing of the obtained data also includes calculation of hydrogen index (HI), productivity index (PI), oil saturation index (OSI) and coefficient of unconverted kerogen (Kgoc) as expressed in Eqs. 4–7, respectively.

To avoid influence of heavy hydrocarbons on Tmax and S2 parameters, the pyrolysis was conducted before and after the solvent extraction of powdered rock with chloroform in Soxhlet apparatus for 1 month. For selected sample, the extract (heavy HCs and bitumen) was collected during the solvent extraction and separated for further SARA analysis. The pyrolysis parameters measured on the rock after its extraction are labeled below with “ex”. This two-stage procedure of the pyrolysis enabled reliable evaluation of the heavy hydrocarbon content (∆S2) as follows:

For further comparison with NMR results, we defined the following categories of REP corresponding to fluid types in shale rocks32:

-

1.

Light movable hydrocarbons: S0/S0 + S1, in mg HC/g-rock;

-

2.

Heavy hydrocarbons including asphaltenes: ∆S2/S1+∆S2, in mg HC/g-rock;

Nuclear magnetic resonance (low-field NMR relaxometry)

A low-field NMR unit, Oxford Instruments Geospec 2/53 (UK), was used to analyze the core samples at each step of the experimental workflows. The NMR relaxometer is a laboratory analyzer of core samples operating at the 2-MHz frequency with a magnetic field of 0.05 T. The core analysis is based on recording and measuring the polarization and relaxation of hydrogen atoms33,34,35. Analysis and interpretation of results employed principles of NMR application in petrophysics36. The instrument’s calibration used reference samples supplied by the manufacturer with known parameters, including NMR-registered liquid volume and 90° and 180° pulses duration. The T2 relaxation measurements resulted from the Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) pulse sequence with the time-echo TE = 2τ where TE was set to 0.1 ms. The utilized parameters of NMR testing are summarized in Table 3. Initial data processing and interpretation was performed using the Green Imaging Technologies (GIT) Systems Advanced v.7.5.1 software. In addition to the saturation measurements, the pore size distribution was estimated based on the obtained T2 distributions. The transverse relaxation time (T2) is sensitive to the surface-to-volume (S/V) ratio of pores. This relationship allows conversion of T2 values into pore size estimates, providing insights into pore structure and distribution. Attenuation of the T2 signal is inversely proportional to S/V. If pore geometry is considered, cylindrical and spherical pores will have different pore-to-throat ratios. Tight shale systems typically assume cylindrical pores where:

where T2 is the relaxation time (in ms), r – is the pore radius (in µm), and the ρ – is the surface relaxivity coefficient, which depends on the mineralogy. The pore size distribution was generated from the T2 distributions for investigated samples using a surface relaxivity coefficient of 10 μm/sec, which remains a widely accepted approximation for shale rocks37,38,39.

XRD/XRF analyses

Mineralogy analysis on core powder was performed using the benchtop Rigaku Smartlab X-Ray diffractometer unit. The elemental composition was analyzed using a portable X-Ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer – Vanta C manufactured by Olympus. The range of the elements determined is from Mg to U. The XRF data were converted to mineral composition using nondeterministic inversion approach.

Core preparation and porosity measurement

The rock samples were dried at a temperature of 100 °C in the Memmert VO400 vacuum oven until the constant weight (∆0.001 g). Core saturation procedure consisted of vacuuming the samples, capillary imbibition, and injection of a saturating fluid (Decane) during 72 h under a pressure of 15 MPa using an automated saturating unit PIK-SK (Geologika). The residual water saturation of the core plugs was determined by gas drainage in a Vinci Technologies RC‑4500 refrigerated centrifuge operated at a maximum speed of 4,500 rpm, spinning the samples in 24-, 48-, and 72-hour increments until water production ceased. The pressure drop across the sample was 1.4 MPa for the capillary pressure of ~ 4.3 MPa; the centrifugal force (g) equals 5100.

Gas porosity and permeability measurements were carried out at the PIK-PP automated permeameter-porosimeter (Geologika) using pressure pulse decay technique at confining pressure of 3.4 MPa; Helium was selected as a gas. The core plugs were tested in as-received state without prior solvent cleaning. Due to the low open porosity of the samples and the high amount of viscous components, the test was repeated at least three times, and the average value was selected. The measurement uncertainty in determining the permeability in the measuring range from 0.1 to 1 mD is ± 0.05 mD and in the range from 1 to 5000 mD, the total relative error is ± 8%.

The open (liquid) porosity of the core samples was determined using the standard liquid saturation or gravimetric method. The technique consists of saturating a rock sample with a liquid (Decane, density 0.7269 g/cc at T = 24.8 °C) and determining its mass/volume in the air and the saturating fluid utilizing high-precision laboratory scales A&D GH-202GH with AD1653 gravimetric console.

Results

All core plugs were provided by the oil company in as-is state, without a paraffin isolation. The initial selection of core samples from the core storage was based on available data for porosity and permeability (by gas), depth, and mineral composition. During core selection, at least one representative sample from each member of the Bazhenov Formation was included to the collection (Fig. 1).

Organic matter properties and mineral composition of the rock

The composition of core plugs includes a variety of rock-forming minerals (Fig. 3)40. For most samples, quartz minerals dominate with a content of up to 78 wt%. Samples #1103, #1097 and #1098 predominantly contain carbonate minerals. Kerogen content follows the typical pattern for the Bazhenov Formation, with higher TOC values (up to 15 wt%) in the Upper Bazhenov Formation. Other components are clay minerals (illite, kaolinite), pyrite, and N-feldspars. Based on obtained XRF results, we have divided the entire collection into six different lithological groups: carbonates, mixtites, clays, silicites, silicites with clays, and clays with silica that represent each member of the Formation (Fig. 4).

The pyrolysis was performed in a bulk-rock mode before and after the solvent extraction (Table A1 in Appendix A). The TOC content ranges from 2.3 to 14.6 wt%, with HC products of kerogen cracking content (S2ex) varying from 4.3 to 81.7 mg HC/g-rock. The sample maturity degree is confirmed by high hydrogen index (HIex) values corresponding to the early oil window, averaging around 500 mg HC/g TOC, with local minima corresponding to intervals of low organic matter content, and also by Tmaxex values ranging from 432 to 439 °C, and low productivity index (PI), averaging 0.14. These results indicate that the sample collection has excellent generation potential.

The Upper BF shows a higher heavy hydrocarbon content (∆S2), averaging 8 mg HC/g-rock, while the Lower BF has an average ∆S2 of 2.4 mg HC/g-rock. Light hydrocarbon content (S0 + S1) in the Upper BF reaches up to 12 mg HC/g-rock, with an average of 7.7 mg HC/g-rock, which is double that of the Lower BF, where the average S0 + S1 is 3.3 mg HC/g-rock. Sample #1105 can be identified as enhanced reservoir properties interval. This sample exhibit the highest productivity index PI 0.29 and high oil saturation index (OSI) 160 mg HC/g TOC, and relatively high light hydrocarbon saturation relative to organic matter content. Additionally, we analyzed the hydrocarbon extract (liquid sample) from the Upper Bazhenov Formation at an interval of XX45.08 m using REP and NMR measurements on the sample in heated (liquid) and solid states.

NMR core analysis

The obtained T2 distributions were separated into groups in accordance with the presence of a free fluid signal, the relaxation time at peak’s maximum, as well as the number, magnitude, and width of peaks. These groups can be associated with their mineral composition and reservoir properties (Fig. 5). The results show that large proportion of pores are concentrated in the 0.001 to 0.1 μm range (Fig. 5); the differentiation between micropores (< 2 nm), mesopores (2–50 nm) and macropores (> 50 nm) is demonstrated based on the IUPAC classification of pore sizes in porous media. Most samples show zero free fluid fraction, with signal the most recorded signals located in the low relaxation times of up to 10 ms. However, samples #1103, #1104, and #1105 have a significant amount of free fluids within the relaxation time range of 10 to 100 ms and categorized as a separate groups. The total fluid saturation of as-is samples varies from 0.8 to 2.2 ml while the registered ‘porosity’ ranges from 3.3 to 9.1% (Fig. 6). This porosity is primarily attributed to the partial registration of high-viscosity fluids by NMR, as well as the presence of a certain amount of closed pores remaining in the rock; empty open pores are not included.

The NMR total porosity of decane-saturated samples in FFI workflow (A) ranges from 4.2 to 15.8% (Table A2); the open porosity (differential signal Sdec-Sdry) varies from 0.6 to 7.71%, whereas the gravimetric method indicates a maximum porosity of 5.8% (Table A3). The observed discrepancy between total and open porosity measured by NMR arises because the total porosity measurement captures signals from clays and organic matter41,42. This occurs because the core samples were not cleaned prior to the saturation stage, leaving the heavy hydrocarbons in the rock. According to the BVI workflow (B), the NMR measurements were repeated for dried samples, and amount of removed fluids (differential signal Sdry-Sas−is), including clay-bound water, were determined: the amount varied from 0.14 to 0.88 ml, averaging 0.54 ml (2.46% in absolute values). After the saturation of samples (B) with Decane, the total porosity by NMR ranged from 6.5 to 11.9%, with an average value of 8.7%. (Fig. 6). Although some of the mobile fluid was removed during the drying process, the samples in workflow B were also not cleaned of heavy hydrocarbon components, which contributed to the high total porosity values. The open porosity varied from 1.7 to 8.3%, average value was 4.1% (Table A4). The NMR porosity plots show that a significant portion of the NMR-registered fluid (Decane and residual fluids) was removed during the drying process (Fig. 6) with an average sample weight reduction of 0.66 g.

The goal of FFI workflow (A) was to preserve the initial saturation of shale samples and, at the same time, to characterize the maximum of the occupied porous space in the rock by high-pressure saturation without preliminary cleaning or drying the samples. In turn, in the BVI workflow, samples were first dried and then saturated. Comparison of workflows on two sets of duplicate samples was used to identify the advantages and limitations of each schemes. From practical point of view, within workflow A, the lower number of samples was destroyed, which proves an accurate determination of the total porosity on non-destructed samples. Similar to their initial pore size distributions (Fig. 5), the porosity values of duplicate samples in as-is state vary slightly and show the maximal difference of 0.8 abs.%. However, in Decane-saturated state, the three samples with high clay content (pairs of 1095, 1104 1108) exhibit the increased values of porosity when saturation step followed the as-is step without preliminary drying (Table 4). In this case, the total porosity values included the signal both from bound and mobile fluids. In contrary, for the sample with 59.6 wt% clay content (1106) the porosity obtained in BVI workflow (B) is higher than that in workflow FFI (A): it can be explained by damaged clay minerals when drying and clay swelling during the high-pressure saturation. The ‘porosity’ of dried samples (i.e. remaining fluid volume) is same for samples of both workflows that confirms that the mass-controlled vacuum drying at 70 °C entirely removed the Decane from samples that underwent the workflow A. The open porosity values are calculated based on the NMR differential signal between saturated and previous stages of core analysis (Sdec-Sas−is for workflow A and Sdec-Sdry for workflow B), and therefore these results demonstrate how the order of core analysis can impact the overall values.

The size of the pores occupied by Decane for duplicate samples with high clay content varies from 0.1 μm to 1 μm with a minimal amount of fluid present in the pores with a radii up to 10 μm (Fig. 7). The primary difference in saturation between the samples from workflows A and B is the increased level of fluid in pores of the mesopores region for samples of FFI workflow (A), possibly due to the remaining light HCs and bound fluid that was not removed before saturation. Additionally, it should be noted that the presence of microcracks in the saturated samples contributes to an increased NMR signal in larger pores, resulting in high relaxation times (T2) within the 300–1000 ms range that corresponds to macropores region in the pore size distribution.

1D T2 analysis: bound and mobile fluids, T2 cut-off determination, porosity

To model the residual saturation and determine T2 cut-off, several fluid displacement methods, including constant temperature drying (at 70 °C under vacuum) and high-speed centrifugation were applied. First, samples #1103 and 1104 (workflow A) were centrifuged in the as-is state (Fig. 8a, b). The negligible saturation change from centrifuge confirms the limited application of centrifuging technique to removing the HCs from tight rocks given the maximal rotation speeds and achieved pressure (1.5 MPa). Next, selected Decane-saturated samples (#1098 and 1104) were centrifuged to obtain the residual saturation state and determine the T2 cut-off values (Fig. 8c, d). Although the calculated cut-off values (4.6 ms and 8.2 ms) are close to the common range for shales (8–10 ms), the saturation change before and after centrifugation indicate that the centrifuging method cannot be applied for reliable determination of the T2 cut-off value due to low permeability of samples. Therefore, the conventional 1D T2 analysis with fluid separation into the CBW, BVI and FFI categories can provide incorrect estimates due to few reasons, First, as described here, is the absence of quick experimental techniques to define the cut-off values for separation of bound and mobile fluids. Second, in shale rock samples, the major part of NMR signal registered in CBW and BVI regions includes the signal from heavy and adsorbed HCs. To accurately quantify these regions, the detailed T1-T2 analysis was conducted on entire collection in Sas-is, Sdry and Sdec saturation states.

For the entire sample collection, the open porosity values by NMR were compared with the gravimetric and gas volumetric porosity measurements (Fig. 9). The slight discrepancy between NMR-derived and gas porosity values can be attributed to the different physical principles underlying each measurement technique, as well as technical limitations of the pressure decay method when applied to low-permeability samples. In addition, the gas porosity tests were conducted on samples in as-is state without prior solvent cleaning, and the obtained porosity values do not register the pores occupied by residual fluids. The comparison of open porosity values obtained from NMR and the gravimetric method showed good agreement, confirming the reliability of both methods for measuring open porosity.

2D T1–T2 analysis: identification of fluid clusters

Additionally, two-dimensional T1-T2 maps were employed for qualitative and quantitative fluid saturation assessments across all samples (Table A5). Distinct zones on the T1-T2 maps were identified, and the proportion of each fluid type was calculated in both percentage (%) and absolute volume (ml) (Fig. 10). The maps revealed residual (initial) oil and water saturation for samples in the as-is state, including clay-bound water. The maps quantified the mobile oil saturation for Decane-saturated samples according to the simplified schemes proposed for similar object earlier42. Fluids were classified into the following categories: (1) heavy and adsorbed hydrocarbons (HCheavy), (2) bound fluids (WCBW), and (3) mobile fluids such as mobile oil in as-is samples, and residual mobile oil and Decane in saturated samples (HCmobile).

The data obtained from T1-T2 maps was further used for comparison of NMR-based HC fluid composition (HCheavy, WCBW, HCmobile) vs. the mineral composition of the rock (quartz and clays) and OM components quantified by Rock-Eval pyrolysis on duplicate core fragments.

Discussion

Correlation of NMR results (fractions from T1–T2) with mineral composition and REP analysis

Integrated analysis of NMR results and mineral composition of the rock shows that the highest residual HC (Total HC) saturation in as-is state is noted for silicites and silicites with clays (types 4, 5) (Fig. 11a). However, only samples of lithotype 5 contain a significantly large amount of mobile HCs (Free HC) in macropores, which is explained by high content of quartz in those layers. Carbonates, mixtites and argillites do not demonstrate pronounced correlations with residual mobile oil saturation. The most interesting results belong to the intervals represented by silicites, silicites with clays, and clays with silica rock types (Fig. 11b). The mobile fluid volume (Total HC for Sdec-Sdry) is gradually increasing for lithotypes with codes from 1 to 6; for mobile HCs the same positive trend remains in less pronounced way.

The relation between the content of clay minerals in the rock and NMR-derived clay-bound water content (WCBW) can be observed in Fig. 12a. While conventional understanding states that NMR measurements are matrix-independent, prior studies suggest certain mineral groups—particularly clays and silica—may influence NMR responses42,43. In the analyzed rocks, quartz and clays are main rock-forming minerals. The quartz content is directly related to the pore structure geometry and connectivity in larger pores, while clays retain substantial bound water registered in WCBW cluster of T1-T2 maps. Therefore, there is also a positive relationship between rock silica content and NMR mobile porosity, showing that rocks with higher silica content have higher mobile porosity (Fig. 12b). Samples with a different mineral composition (carbonates, clays) in some cases deviate from the general trend (showing increased mobile porosity), which does not contradict the positive correlation between silica content and mobile porosity. These correlation validates the accuracy of our T1-T2 maps interpretation approach, confirming that applied fluid typing reliably distinguishes different HC populations for target samples and linking mineralogy to NMR fingerprints. Moreover, these results align with dependencies identified by Kazak et al.44 on determining water content in shale rocks.

Relation between HCs volume by NMR and mineral composition of the samples (clays and silica content); samples are color coded by lithotype according to Fig. 4.

The integration of NMR and REP results and incorporating fluid identification data obtained from pyrolysis and T1-T2 maps for shale rocks was first demonstrated for the similar geological object in our previous research on limited core collection25,42. Earlier19 identified a linear correlation (R2 = 0.9) between the NMR signal intensity of heavy oil/solid organic matter from T1-T2 maps (obtained at 20-MHz NMR setup) and Rock-Eval S2 values, reflecting hydrocarbon generation potential. Similarly3 showed that the combined NMR signals from kerogen, adsorbed oil, and free oil (at 20 MHz) exhibit a direct proportionality to total organic carbon (TOC) content and the Rock-Eval S1 + S2 index, which quantifies both free and thermally generated hydrocarbons. However, due to physical reasons, 2 MHz NMR analyzer are not able to register the part of HC clusters captured by 20 MHz units.

Therefore, in this study, we used a simplified fluid model from T1-T2 dataset as depicted in Fig. 13. The fluid composition of the target shale formation is heterogeneous in terms of the presence of bitumen & kerogen, structural & adsorbed oil, and formation water including clay-bound water. Here, we use simplified model of the rock porous space and fluid saturation that can be characterized by 1D T2 NMR analysis (CBW incl. clay-bound water and heavy HCs, BVI, FFI incl. HCs and free water, and Technical liquids (if any) and 2D T1-T2 analysis (WCBW, HCheavy incl. heavy and adsorbed HCs, HCmobile, Free Water and Technical liquids (if any). In both scenarios, we assume the absence of technical liquids and free water in large pores by results of preliminary T2 analysis of samples in Sas−is state.

First, a strong positive linear relationship is observed between light oil (S1), and the combined content variations of light and heavy oils (S1 + ΔS2 and S0 + S1 + ΔS2) (Fig. 14). This correlation also extends to NMR measurements of heavy and bound hydrocarbons, highlighting the consistency in HC content across different analytical methods. The most pronounced correlation by R2 criteria (0.89) is demonstrated for S1 + ΔS2 fraction: values of both NMR and REP-derived volumes are unified to mg/g units. Following previously published understanding of NMR and REP joint application, we attempted to identify the correlation between S0 parameter (light HCs) and free/mobile HCs by NMR: the linear positive dependance (R2 = 0.89) was revealed only for siliceous-clay and clay-siliceous samples that constitute 7 out of 15 samples in the collection, which can be explained by low values of S0 in other lithotypes. Although, the more accurate correlation is observed for the volumes of heavy and bound HC by NMR and combined components S0 + S1 + ΔS2 that provide a close quantitative agreement. The slight discrepancy observed between the pyrolysis results (S1 + ΔS2) and NMR measurements can be attributed to two factors:

-

High viscosity of heavy HCs: the significant amount of asphaltenes, which have extremely high viscosities, have short T2 relaxation times. Consequently, 2 MHz-operating NMR unit registers only part of their total signal.

-

Shale sample destruction during the pyrolysis: the evaporation of light HCs results in saturation change by REP leading to underscored S0 and S1 values. In contrast, non-destructive NMR measurements characterize these mobile HCs more precisely.

Linear correlation between T1-T2 determined HCheavy and pyrolysis fractions for Sas-is saturation state (a) S1 light HCs, (b), light and heavy S1 + ΔS2 and (c) gas, light and heavy HCs S0 + S1 + ΔS2; samples are color coded by lithotype according to Fig. 4.

Dependency of T2 spectrum intervals and REP fractions

As demonstrated earlier, typing and quantifying HC saturation is not feasible by T2 distribution manual analysis due to the interfering signals from bound fluids and heavy HCs in the CBW cluster. In general, characterization of unconventional rocks is challenging, particularly when modeling general dependencies between PSD, pore geometry, and fluid types. To this end, this gave a rise to application of new mathematical tools, grounded on information entropy, fractal theory, wavelet analysis in attempt to resolve hidden dependencies in pore-fluid interactions45,46. We utilized mutual information (MI) regression to map T2 signal to different HC types and resolve their signal interference and estimate the influence of mineral composition to HC volume. This non-parametric statistical method is used in signal processing and analysis of information-dense experimental data such as time series and spectrometry47,48,49. We used it to quantify information gain between different T2 distribution intervals vs. Rock-Eval parameters and vs. XRD-determined rock composition by estimating their probability distributions. While this method cannot be used for direct typing of fluids or mineral matrix of the sample, nor indicate the direction of the correlation between variables, it can be used to identify T2 distribution intervals for which the T2 signal amplitudes contribute information to the sample property, such as volume and type of HC fractions and mineral composition.

Figure 15a, b shows the average information gain for each of 83 discrete T2 bins with hydrocarbon fractions detected by Rock Eval pyrolysis. Light HCs (S0 + S1) content has been found to be dependent on T2 amplitudes at relaxation times associated with adsorbed HCs in nano and micropores (0.01–0.15 ms) and movable HCs in macropores and cracks (80–110 ms). Heavy HCs (∆S2) content exhibits high dependency on the variation of T2 amplitudes around 1 ms, reflecting their primary presence in micro and mesopores, while dependence on T2 signals below 0.2 ms may be related to the presence of asphaltenes and bitumen. Productivity index and oil saturation index describe HC maturity, production potential and free oil content are primarily associated with longer T2 times, corresponding to meso- and macropores with movable fluids, and their information gain is lower, as the T2 signal originates from HC fluids in the pore space, and the samples tested here is in as-is state therefore free HCmobile are underrepresented, also observable in Fig. 15c.

T2 spectra analysis by MI regression for 14 core plugs in Sas−is state: (a) T2 spectrum sensitivity to different HC types; (b) Information gain about HC types relative to cumulative sum of T2 amplitudes; (c) T2 spectrum sensitivity to different mineral types; (d) Information gain about mineral types relative to cumulative sum of T2 amplitudes.

Figure 15c and d illustrate the information gain of T2 bins as function of rock composition, where relative volume fraction of quartz and clay minerals demonstrate highest MI score. The concentration of these minerals affects the matrix and pore geometry and the wettability of the pores – the properties tightly related to distribution of capillary and clay-bound fluids. Since quartz and clay minerals content is predominant in the studied samples, their relative proportions influence the distribution of HCs and pore sizes (T2 distribution). For quartz content, two intervals in T2 distribution have significant gain of information – from 0.07 to 0.2 ms where information gain for T2 signals is above 0.4 nats, and at 0.8–5 ms where information gain is 0.3–0.4 nats. For clay content, the T2 intervals with high information gain are almost identical, however the score magnitudes are reversed.

Effect of clay and quartz content to the T2 distribution properties can be further studied in Fig. 16. First, samples containing high volume clays tend to have narrow unimodal distribution with high peaks, while quartz-rich samples tend to have broader distributions. This confirms the relative content of quartz and clay minerals is reflected in pore size distribution, where quartz-rich samples in this study have more heterogeneous pore size distribution. Furthermore, Fig. 17 illustrates the T2 distributions color coded by the sample’s oil saturation index (OSI) and productivity index (PI). It can be observed that samples with broad, bi-modal T2 spectrum and smaller amplitudes exhibit positive relationship with producible light HCs and with the quartz content in samples (Fig. 16a).

Conclusions

Based on the presented characterization of fluid saturation by NMR and REP in organic-rich source rocks the following conclusions can be made:

1. Total fluid saturation of ‘as-is’ samples within both FFI and BVI workflows ranges from 0.8 to 2.2 ml, while total porosity varies between 3.3% and 9.1%, primarily attributed to presence of high-viscosity asphaltenes and bitumen. This makes conventional T₂ analysis inefficient in estimating the CBW, BVI, and FFI regions due to heavy HCs dominating the signal and complications and in defining the cut-off values. The comparison of duplicate samples show variation in Decane saturation, total and open NMR porosity (0.6–7.7% for A and 1.7–8.3% for B workflow) and pore size distribution for samples under different designs of core analyses demonstrating the advantages and limitations for each workflow. Considering the comparison of porosity results across workflows A and B, as well as the integrity of core due to lower risks of damage, the workflow A is recommended for rapid analysis of shale rock saturation.

2. Correlation analysis revealed a positive relationship between pyrolytical parameters by Rock-Eval pyrolysis and saturation by NMR: comparison of the S1+∆S2 fraction and the cluster adsorbed and heavy HCs by T1-T2 NMR shows good qualitative convergence while the correlation with S0 + S1+∆S2 has a good prediction range with R2 = 0.87 on a limited core collection. In summary, NMR and Rock-Eval pyrolysis complement each other by providing detailed insights into hydrocarbon composition of shales, and their combined use in NMR log data analysis can enhance the prediction of fluid mobility and identification of high oil-in-place zones.

3. The influence of mineral composition and lithotype on the fluid saturation of rocks was demonstrated: a relationship between the content of clay minerals and NMR-derived volume of bound water is observed. A positive but less pronounced correlation was revealed between the silica content and the mobile porosity of the samples: rocks with an increased content of silica are characterized by higher mobile (open) porosity.

4. Mutual Information regression-assisted analysis revealed the information gain between corresponding T2 distribution intervals vs. Rock-Eval parameters (S0 + S1 and +∆S2) and vs. XRD-determined clay and quartz content by estimating their probability distributions and their effect on MI score. In addition, the correlation between PI and OSI parameters and T2 distributions was demonstrated. Further application of ML-based algorithms can be helpful in further development and training the model that can predict and characterize the OM maturity, fluid composition and clays content based on the T2 spectrum obtained by nuclear magnetic resonance logging.

Data availability

Data is available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AR:

-

As-received (as-is)

- BF:

-

Bazhenov Formation

- BVI:

-

Bound Volume Irreducible

- CBW:

-

Clay-Bound Water

- CPMG:

-

Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill sequence

- FFI:

-

Free Fluid Index

- GIT:

-

Green Imaging Technologies (Software)

- GOC:

-

Generative Organic Carbon

- HC:

-

Hydrocarbon(s)

- HI:

-

Hydrogen Index (in REP)

- ILT:

-

Inverse Laplace Transform

- IR:

-

Inversion Recovery

- MI:

-

Mutual Information

- MICP:

-

Mercury Injection Capillary Pressure (Porosimetry)

- ML:

-

Machine Learning

- LF-NMR:

-

Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

- NGOC:

-

Non-Generative Organic Carbon

- NSA:

-

Number of Scans Aquired

- OH:

-

Hydroxyl Group

- OM:

-

Organic Matter

- OSI:

-

Oil Saturation Index

- PD:

-

Pressure Decay

- PI:

-

Productivity Index

- PSD Pore:

-

Size Distribution

- RD:

-

Recycle Delay

- REP:

-

Rock-Eval Pyrolysis

- SARA:

-

Saturates, Asphaltenes, Resins, Aromatics (Analysis)

- SCAL:

-

Special Core Analysis

- SEM:

-

Scanning Electron Microscopy

- SNR:

-

Signal-to-Noise Ratio

- TE:

-

Time-Echo

- TOC:

-

Total Organic Carbon (content)

- XRD:

-

X-ray Diffractometry

- XRF:

-

X-ray Fluorescence

References

Romero-Sarmiento, M. F., Ramiro-Ramirez, S., Berthe, G., Fleury, M. & Littke, R. Geochemical and petrophysical source rock characterization of the Vaca muerta formation, argentina: implications for unconventional petroleum resource estimations. Int. J. Coal Geol. 184, 27–41 (2017).

Curtis, M. E., Sondergeld, C. H., Ambrose, R. J. & Rai, C. S. Microstructural investigation of gas shales in two and three dimensions using nanometer-scale resolution imaging. AAPG Bulletin 96 (2012).

Li, J. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance T1- T2 map division method for Hydrogen-Bearing components in continental shale. Energy Fuels. 32, 9043–9054 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Adsorbed and free hydrocarbons in unconventional shale reservoir: A new insight from NMR T1-T2 maps. Mar. Pet. Geol. 116, 104311 (2020).

Jarvie, D. M., Jarvie, B. M., Weldon, W. D. & Maende, A. Geochemical Assessment of Petroleum in Unconventional Resource Systems. SPE/AAPG/SEG Unconventional Resources Technology Conference URTEC-2173379-MS (2015). https://doi.org/10.15530/URTEC-2015-2173379

Loucks, R. G., Reed, R. M., Ruppel, S. C. & Jarvie, D. M. Morphology, genesis, and distribution of nanometer-scale pores in siliceous mudstones of the Mississippian barnett shale. J. Sediment. Res. 79, 848–861 (2009).

McPhee, C., Reed, J. & Zubizarreta, I. Core Analysis: A Best Practice Guide. Developments in Petroleum Science (Elsevier, 2015).

Michael, G. E., Packwood, J. & Holba, A. Determination of In-Situ Hydrocarbon Volumes in Liquid Rich Shale Plays. Unconventional Resources Technology Conference (2013).

Odusina, E. O., Sondergeld, C. H. & Rai, C. S. NMR Study of Shale Wettability. SPE Unconventional Resources Conference (2011). https://doi.org/10.2118/147371-MS

Rylander et al. E. NMR 2D Distributions in the Eagle Ford Shale: Reflections on Pore Size. (2013).

Tinni, A., Odusina, E., Sulucarnain, I., Sondergeld, C. & Rai, C. S. Nuclear-Magnetic-Resonance response of brine, oil, and methane in Organic-Rich shales. (2015). https://doi.org/10.2118/168971-PA

Veselinovic, D., Dick, M. J., Kenney, T. & Green, D. Multi field evaluation of T2 distributions and T1-T2 2D maps. in Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, 20–22 June 1–7 (Unconventional Resources Technology Conference (URTeC), 2022). doi: 1–7 (Unconventional Resources Technology Conference (URTeC), 2022). doi: (2022). https://doi.org/10.15530/urtec-2022-3723406

Dick, M. J., Veselinovic, D. & Green, D. Review of recent developments in NMR core analysis. Petrophysics - SPWLA J. Form. Eval Reserv. Descr. 63, 454–484 (2022).

Dang, S. T. et al. Understanding NMR responses of different rock-fluid components within organic-rich argillaceous rocks: Comparison study Across 2, 12, and 23 MHz spectroscopy. in Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, 13–15 June 2142–2153 (Unconventional Resources Technology Conference (URTeC), 2023). doi: 2142–2153 (Unconventional Resources Technology Conference (URTeC), 2023). doi: (2023). https://doi.org/10.15530/urtec-2023-3863533

Bai, L. et al. A new method for evaluating the oil mobility based on the relationship between pore structure and state of oil. Geosci. Front. 14, 101684 (2023).

Rylander, E. et al. NMR T2 distributions in the Eagle Ford shale: Reflections on pore size. Society of Petroleum Engineers - SPE USA Unconventional Resources Conference 2013 426–440 (2013). https://doi.org/10.2118/164554-MS

Westphal, H., Surholt, I., Kiesl, C., Thern, H. F. & Kruspe, T. NMR measurements in carbonate rocks: problems and an approach to a solution. Pure Appl. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-004-2621-3 (2005).

Jian-Ping, Y. A. N. et al. A quantitative evaluation method of low permeable sandstone pore structure based on nuclear magnetic resonance (Nmr) logging: A case study of Es4 formation in the South slope of Dongying Sag. Chin. J. Geophys. 59, 313–322 (2016).

Khatibi, S. et al. NMR relaxometry a new approach to detect geochemical properties of organic matter in tight shales. Fuel 235, 167–177 (2019).

Birdwell, J. E. & Washburn, K. E. Multivariate analysis relating oil shale geochemical properties to NMR relaxometry. Energy Fuels. 29, 2234–2243 (2015).

Kontorovich, A. E. et al. Main oil source formations of the West Siberian basin. Pet. Geosci. 3, 343–358 (1997).

Lopatin, N. V. et al. Unconventional oil accumulations in the upper jurassic Bazhenov black shale formation, West Siberian basin: A Self-Sourced reservoir system. J. Pet. Geol. 26, 225–244 (2003).

F. Ulmishek, G. Petroleum geology and resources of the West Siberian basin, Russia. Bulletin https://doi.org/10.3133/b2201G (2003). https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/b2201G

Spasennykh, M. et al. Geochemical Trends Reflecting Hydrocarbon Generation, Migration and Accumulation in Unconventional Reservoirs Based on Pyrolysis Data (on the Example of the Bazhenov Formation). Geosciences vol. 11 (2021).

Mukhametdinova, A. et al. Characterization of pore structure and fluid saturation of Organic-Rich rocks using the set of advanced laboratory methods. ADIPEC D011S019R002 https://doi.org/10.2118/216438-MS (2023).

Ryzhkova, S. V. et al. The Bazhenov horizon of West siberia: structure, correlation, and thickness. Russ Geol. Geophys. 59, 846–863 (2018).

Balushkina, N. S. et al. Complex Lithophysical Typization of Bazhenov Formation Rocks from Core Analysis and Well Logging. SPE Russian Oil and Gas Exploration & Production Technical Conference and Exhibition SPE-171168-MS (2014). https://doi.org/10.2118/171168-MS

Khamidulin, R. A., Kalmykov, G. A., Korost, D. V., Balushkina, N. S. & Bakay A. I. Reservoir properties of the Bazhenov formation. in (2012).

Espitalie, J., Deroo, G. & Marquis, F. La pyrolyse Rock-Eval et Ses applications. Premiére partie. Rev. L’Institut Fr. Du Pétrole. 40, 563–579 (1985).

Peters, K. E. Guidelines for evaluating petroleum source rock using programmed pyrolysis. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 70, 318–329 (1986).

Espitalie, J., Bordenave, M. L. & Bordenave, M. L. Rock-Eval pyrolysis. Applied Petroleum GeochemistryTechnip ed., (1993).

Kozlova, E. V. et al. Geochemical technique of organic matter research in deposits enrich in kerogene (the Bazhenov formation, West Siberia). Mosc. Univ. Geol. Bull. 70, 409–418 (2015).

Bloembergen, N., Purcell, E. M. & Pound, R. V. Relaxation effects in nuclear magnetic resonance absorption. Phys Rev 73, (1948).

Abragam, A. The Principles of Nuclear Magnetism (Clarendon, 1961).

Callaghan, P. Principles of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Microscopy (Clarendon, 1991).

Straley, C., Rossini, D., Vinegar, H. J., Tutunjan, P. & Morriss, C. E. Core analysis by Low-Field NMR. Log. Anal. 38, 84–94 (1997).

Sigal, R. F. Pore-Size distributions for Organic-Shale-Reservoir rocks from Nuclear-Magnetic-Resonance spectra combined with adsorption measurements. SPE J. 20, 824–830 (2015).

Lyu, C., Ning, Z., Wang, Q. & Chen, M. Application of NMR T2 to pore size distribution and movable fluid distribution in tight sandstones. Energy Fuels. 32, 1395–1405 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Characterization of shale pore size distribution by NMR considering the influence of shale skeleton signals. Energy Fuels. 33, 6361–6372 (2019).

Leushina, E. et al. Upper Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous Source Rocks in the North of Western Siberia: Comprehensive Geochemical Characterization and Reconstruction of Paleo-Sedimentation Conditions. Geosciences vol. 11 (2021).

Li, J. et al. A new method for measuring shale porosity with low-field nuclear magnetic resonance considering non-fluid signals. Mar. Pet. Geol. 102, 535–543 (2019).

Mukhametdinova, A., Habina-Skrzyniarz, I., Kazak, A. & Krzyżak, A. NMR relaxometry interpretation of source rock liquid saturation — A holistic approach. Mar. Pet. Geol. 132, 105165 (2021).

Saidian, M. & Prasad, M. Effect of mineralogy on nuclear magnetic resonance surface relaxivity: A case study of middle Bakken and three forks formations. Fuel 161, 197–206 (2015).

Kazak, E. S., Kazak, A. V. & Bilek, F. An integrated experimental workflow for formation water characterization in shale reservoirs: A case study of the Bazhenov formation. SPE J. 26, 812–827 (2021).

Jouini, M. S. et al. Experimental and digital investigations of heterogeneity in lower cretaceous carbonate reservoir using fractal and multifractal concepts. Sci. Rep. 13, 20306 (2023).

Kalule, R. et al. Quantifying Inter-Well connectivity and Sweet-Spot identification through wavelet analysis and machine learning techniques. ADIPEC D011S003R004 https://doi.org/10.2118/221817-MS (2024).

Ghazi, A. R. et al. High-sensitivity pattern discovery in large, paired multiomic datasets. Bioinformatics 38, i378–i385 (2022).

Li, Y., Guo, W., Xie, W., Jiang, T. & Du, Q. M. M. I. F. Interpretable hyperspectral and multispectral image fusion via maximum mutual information. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–13 (2024).

Markovic, S., Mukhametdinova, A., Cheremisin, A., Kantzas, A. & Rezaee, R. Matrix decomposition methods for accurate water saturation prediction in Canadian oil-sands by LF-NMR T2 measurements. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 233, 212438 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to their colleagues from Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology: Pavel Grishin and Natalia Bogdanovich for discussion and insightful comments on core analysis design, Timur Bulatov for assistance with the experimental pyrolysis data, and Philip Denisenko and Alexander Borisov for their help with routine core measurements. Emad W. Al-Shalabi would also like to acknowledge the financial support provided by Khalifa University of Science and Technology through the RICH center (project RC2-2019-007). The authors thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback, which helped improve the quality of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation under agreement No. 075-10-2022-011 within the framework of the development program for a world-class Research Center. Emad W. Al-Shalabi would also like to acknowledge the financial support provided by Khalifa University of Science and Technology through the RICH center (project RC2-2019-007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M., A.K., E.W.A. and M.S. conceived and planned the experiments, P.M., A.M. and E.K. conducted the experiments, A.M., P.M. and S.M. processed the data and performed the analysis, E.K., A.C., E.W.A., A.K. and M.S. data curation, P.M., A.M. and S.M. drafted the manuscript and designed the figures. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mukhametdinova, A., Markovic, S., Maglevannaia, P. et al. Characterizing low-permeable shales using Rock-Eval pyrolysis and nuclear magnetic resonance for reconstruction of fluid saturation model. Sci Rep 15, 34198 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15619-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15619-z