Abstract

Emergency personnel operating in high-temperature environments while wearing protective equipment experience substantial thermophysiological strain, impairing performance and increasing the risk of heat-related illnesses. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the effects of cooling interventions on core temperature, skin temperature, heart rate, sweat rate and tolerance time in emergency personnel exposed to heat stress. A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed-MEDLINE, Web of Science and Cochrane Library databases up to March 2024. Controlled experimental studies published in English or Spanish were included if they assessed cooling interventions (pre-, per-, intermittent, or post-cooling; internal vs. external methods) in participants wearing protective clothing in heat stress conditions (> 28 °C), and included a non-cooling control group. Twenty studies met the inclusion criteria. Cooling interventions significantly reduced core temperature (ES = − 0.56, p < 0.001), heart rate (ES = − 0.42, p = 0.001), and sweat rate (ES = − 0.70, p < 0.001), while improving tolerance time (ES = 1.44, p = 0.003). Intermittent and per-cooling approaches, particularly those employing mixed-method strategies (e.g., cooling vests with immersion or ice slurry ingestion), yielded the greatest benefits. No significant changes were observed in skin temperature. Cooling interventions effectively mitigate physiological strain in emergency personnel exposed to heat stress. Intermittent and per-cooling using combined methods appear most effective. Nonetheless, logistical constraints may limit field implementation, highlighting the need for further research to optimize practical cooling protocols.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Certain occupations involve unavoidable exposure to both acute and chronic health risks, making full and efficient job performance inherently challenging1. Emergency service roles demand high levels of physical exertion2. Structural firefighters have been reported to reach ~ 95% of their maximum heart rate (HRmax) and 80% of their maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) during simulated rescues3. Wildland firefighters sustain workloads averaging 66% HRmax for over three hours4, while mountain rescue personnel operate at 80–90% VO2max and ~ 90% HRmax during simulated rescues5. These demands are further intensified under extreme environmental conditions, with operational temperatures reaching up to 200 °C for structural firefighters6 and ~ 80 °C for wildland firefighters7.

To mitigate occupational risks, personal protective equipment (PPE) is mandatory. However, PPE impairs thermoregulation8,9,10 by increasing metabolic heat production and limiting heat dissipation due to its insulation properties11,12. As a result, emergency workers experience elevated core (Tcore) and skin (Tskin) temperatures, increased heart rate, greater sweating rates, and heightened perceptions of exertion and thermal discomfort compared to neutral conditions13. Tcore levels often exceed 38.5 °C, and in prolonged operations surpass 39 °C, highlighting the substantial thermal strain on these workers3,4, which accelerates fatigue and elevates the risk of heat-related illnesses14.

Heat stress is a major occupational concern, affecting health, safety, and performance. Future climate projections indicate rising wet-bulb globe temperatures, exacerbating environmental heat stress15,16. This poses a dual threat, elevated Tcore for a given workload17 and reduced capacity for heat dissipation during rest periods18. Research on strategies to reduce physiological strain during exertion has increased19, with aerobic fitness and heat acclimation being the most effective long-term strategies20,21. However, these require weeks or months to yield benefits. In contrast, cooling strategies provide immediate reductions in thermophysiological strain22,23.

Cooling methods are broadly categorized as passive (e.g., resting or removing protective clothing) or active, including convective and conductive techniques24. Common active strategies used in occupational and sports contexts include external methods (e.g., cooling garments, cold-water immersion, fan use) and internal methods (e.g., ingestion of cold fluids or ice)25,26. Among emergency workers, studies have investigated hand and forearm immersion27, whole-body cold-water immersion28, ice-slurry ingestion28, cooling vests29,30,31,32, fan-assisted cooling33, and combined approaches25,34,35.

Cooling strategies can be implemented before activity (pre-cooling), such as through the use of ice vests or cold fluid ingestion22; during activity (per-cooling), to enhance feasibility under operational conditions36, or intermittently during rest breaks37. For example, structural firefighters commonly take breaks between work phases (such as when replacing self-contained breathing apparatus) during which they immerse their hands and forearms in cold water before resuming tasks11,38,39,40,41. Post-cooling techniques, including cold-water immersion and iced-slush ingestion, are also employed to accelerate recovery after exertion28,34,35,42.

The diversity of cooling modalities and application timings complicates the identification of the most effective strategies for reducing heat strain in emergency responders. Recent reviews have addressed specific elements of this issue. Li et al.43 focused on cooling garments used during post-activity recovery in firefighters, whereas Tetzlaff et al.44 examined personal cooling systems in broader occupational contexts involving standard workwear. However, no comprehensive synthesis has yet compared the effectiveness of various cooling interventions in emergency personnel operating under heat stress while wearing full-body PPE. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to examine, synthesize, and compare the effects of different cooling strategies on physiological strain and performance in emergency responders. The resulting evidence seeks to support evidence-based selection and implementation of effective, context-specific cooling protocols.

Methods

Study design

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines45. The study was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews under registration number CRD42020195613.

Databases and search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed-MEDLINE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library from database inception to March 2024 using the following search syntax: (“first responders” OR “firefight*” OR “fireman*” OR “responder*” OR “army” OR “police” OR “soldier*” OR “militar*” OR “fire-fight*”) AND (“protective clothing” OR “protective equipment” OR “protective suit” OR “CBRN” OR “HAZMAT” OR “cooling strategy” OR “cooling vest” OR “cooling device” OR “cooling garment” OR “fluid ingestion” OR “mitigation” OR “alleviation” OR “attenuation” OR “heat stress” OR “heat strain” OR “thermoregulation” OR “hyperthermia”) AND (“temperature” OR “RPE” OR “subjective perception” OR “work time” OR “tolerance time” OR “time to exhaustion” OR “productivity” OR “heart rate” OR “sweat*” OR “evaporat*”).

Additionally, manual searches were conducted for technical reports from research agencies (e.g., governmental or administrative research centers). If a technical report contained the same data as a peer-reviewed publication, the latter was prioritized. Reviews, conference proceedings, editorials, and opinion articles were excluded, but their reference lists were screened for additional relevant studies.

Selection criteria

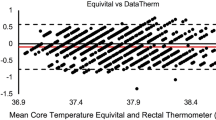

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (i) original quantitative research published in English or Spanish; (ii) controlled experimental design with a non-cooling control group to enable effect size calculation; (iii) no minimum sample size was required, but at least 50% of participants had to be emergency personnel, to enhance ecological validity and facilitate the applicability of findings46; (iv) implementation of a cooling intervention while participants were wearing PPE; (v) exposure to ambient temperatures exceeding 28 °C, to ensure sufficient thermal load for assessing heat mitigation strategies47; (vi) measurement of Tcore via gastrointestinal or rectal methods, considered valid indicators of internal thermal strain.

Studies were excluded if they: (i) did not clearly describe the work protocols; (ii) lacked valid or sufficiently detailed physiological data necessary for effect size calculations (i.e., values at baseline and post-exercise/rest, along with measures of variability such as standard deviation); or (iii) reported Tcore using methods considered unreliable for accurately assessing thermal strain under heat stress (e.g., tympanic or temporal thermometry). These techniques have been shown to significantly deviate from valid Tcore measures and are therefore inadequate for use in high-heat or exercise conditions18,48,49.

Outcome variables

The primary physiological outcome was Tcore, measured using gastrointestinal or rectal thermometry. Secondary outcomes included Tskin, heart rate (HR), total sweat loss (TS), and tolerance time (TT). The effect of cooling interventions was calculated as the difference in these physiological measurements between the cooling and control conditions.

Study selection and data extraction

Two independent reviewers conducted the literature search in duplicate. Search results were compiled using EndNote v9.1 (Thomson Reuters, NY, USA), and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, followed by full-text evaluation based on inclusion criteria. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion. If unresolved, a third reviewer provided a final decision. When relevant data were only available in graphical form, they were extracted using WebPlotDigitizer v4.5 (Automeris LLC, Pacifica, CA, USA) by a single experienced researcher26,50, and verified by another author. Authors were contacted for missing data, and studies were excluded from the meta-analysis if data could not be retrieved.

Data extraction followed the PRISMA four-stage process: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion51. For included studies, extracted data comprised: (i) study characteristics, including authors, year of publication, sample size, participant demographics (age, sex, body mass, height, VO2max, occupation); (ii) experimental conditions, such as environmental temperature, cooling method (e.g., fan use, limb immersion in cold water, cold fluid ingestion, localized cooling with towels/gels, cooling vests). Studies with multiple cooling methods (e.g., cooling vest + cold-water ingestion) were classified as mixed-method cooling26.

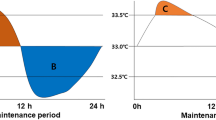

Studies were also categorized according to the timing of the cooling intervention, as follows26: (i) Pre-cooling: cooling applied prior to exercise or during an extended rest period (≥ 15 min) before the next work phase. This strategy aims to reduce Tcore and/or Tskin before physical exertion. In studies with multi-bout protocols, cooling between bouts was classified as pre-cooling only if the rest period met or exceeded 15 min and clearly preceded a new exercise phase. (ii) Per-cooling: cooling applied concurrently with exercise or during scheduled rest intervals within the same work bout. This refers to strategies intended to mitigate heat strain in real time during continuous or cyclic exertion. (iii) Intermittent cooling: cooling delivered during short rest breaks (< 15 min) between multiple work intervals37, typically within a continuous protocol. This differs from pre-cooling in that the cooling is integrated into a repeated work-rest cycle without a prolonged recovery period. In such cases, data were extracted at the beginning and end of the entire work session. (iv) Post-cooling: cooling applied after exercise, either as a recovery strategy or during prolonged rest between clearly delineated work phases (e.g., shift change, redeployment). In studies with mid-protocol cooling, it was classified as post-cooling only if it followed the completion of a work phase and aimed to lower physiological strain before the next work segment. Data were extracted from the end of the first phase and after recovery52.

In studies that compared multiple cooling strategies against a common control condition (e.g., same non-cooling condition used for all comparisons), each intervention was treated as a separate comparison, following established guidelines26.

Risk of bias assessment

Study quality was assessed using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale, a validated tool for evaluating clinical trial methodology53. The 11-item scale produced a maximum score of 10, as the first item was not scored47. Due to the nature of cooling interventions, blinding of participants and evaluators was not possible54. Since participants were aware of whether they used cooling gear and evaluators could not be blinded to interventions, the highest achievable PEDro score was 754. Studies scoring ≥ 6 were classified as high quality. Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias, with disagreements resolved in a group meeting.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

For the meta-analysis, outcome changes were calculated as the difference between baseline and post-intervention values. When not explicitly reported, these differences were computed as the post-intervention value minus the pre-intervention value55. To account for differences in sample size across studies, effect sizes (ES) were calculated using Hedges’ g, along with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Given the expected heterogeneity in populations and protocols, a random-effects model was used to compute the weighted mean ES, with weights assigned according to the inverse of the variance. A CI crossing zero was interpreted as a non-significant effect, whereas a CI not crossing zero indicated a statistically significant effect56. Effect sizes were classified as trivial (< 0.2), small (0.2–0.49), moderate (0.5–0.79), or large (≥ 0.80)57.

Subgroup analyses were conducted to compare the effects of different cooling timings (pre-, per-, intermittent, and post-cooling) and cooling methods (e.g., vests, immersion, fluid ingestion) on key physiological variables. The null hypothesis, that cooling timing or method had similar effects across variables, was tested using a Q-test based on analysis of variance. If the null hypothesis was rejected, pairwise comparisons were conducted using a Z-test56. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Heterogeneity was assessed using the Q-statistic (Mantel-Haenszel estimator), Tau2 58 and I2 statistic, with I2 values interpreted as low (< 25%), moderate (25–75%), or high (> 75%) 59. Publication bias was evaluated through visual inspection of funnel plots and Egger’s test, which was performed when at least 10 studies were available, a p-value < 0.05 was considered indicative of significant asymmetry60. All statistical analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA v3; Biostat; Englewood, USA).

Results

Search results and study selection

The initial search identified 3,915 studies. After removing duplicates and adding additional sources, 3,147 studies remained for title and abstract screening. A total of 176 articles were selected for full-text review. Of these, 149 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria or due to methodological limitation, and 7 were excluded because the full text could not be retrieved despite repeated attempts. Ultimately, 20 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Among these, 16 were randomized crossover trials, 3 were randomized controlled trials, and 1 was a non-randomized trial. The total sample comprised 327 participants. Eleven studies included structural firefighters (n = 234), four involved US Navy personnel (n = 39), two included military personnel (n = 43), one assessed police officers (n = 11).

General study characteristics

Of the 20 studies, four examined pre-cooling, eight investigated per-cooling, six focused on intermittent cooling, and seven evaluated post-cooling (Table 1). The duration of cooling application and total protocol time varied by strategy. Pre-cooling was applied for 15 ± 5 min within a 60-minute protocol, per-cooling for 73 ± 28 min within an 80-minute session, intermittent cooling for 50 ± 40 min across a 126-minute protocol, and post-cooling for 19 ± 5 min within a 60-minute session.

The total sample included327 participants (315 men, 12 women), and as shown in Table S1, the numbers in the original version were typographical errors, with an average value of 52 ml·kg−1·min−1 (Table S1). The studies were published between 1992 and 2022.

Study quality and publication bias

All studies met the inclusion criteria, scoring ≥ 6 on the PEDro scale (Table S2). Funnel plot analysis suggested moderate publication bias for Tcore, HR, and TS, while Tskin and TT exhibited a clear bias toward studies reporting larger effect sizes (Fig. S1). Egger’s test confirmed publication bias for all variables except TS (Appendix S1).

Meta-analysis

Effect on core temperature

Cooling strategies effectively limited the increase in Tcore, (ES = − 0.56, 95% CI [− 0.78, − 0.35], p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed between the different cooling timings (Q = 2.62, df = 3, p = 0.453) (Fig. 2, Table S3). Among the timing strategies, per-cooling (ES = − 0.94, 95% CI [− 1.52, − 0.36], p = 0.002) and post-cooling (ES = − 0.61, 95% CI [− 0.95, − 0.27], p < 0.001) showed the greatest impact. Regarding specific cooling methods, cooling vests (ES = − 0.91, 95% CI [− 1.41, − 0.41]) and mixed-method (ES = − 1.07, 95% CI [− 1.64, − 0.50]) strategies were the most effective, with significant (p < 0.001) reductions in Tcore (Fig. 2, Table S3).

Effect on skin temperature

Cooling had a moderate but non-significant effect on Tskin (ES = − 0.50, 95% CI [− 1.07, 0.06], p = 0.081), although its effectiveness varied significantly (p < 0.001) depending on the timing (Q = 43.87, df = 3, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3, Table S4). Intermittent cooling (ES=‒8.69, 95% CI [− 12.24, − 5.14], p < 0.001) and post-cooling (ES = − 3.71, 95% CI [− 5.93, − 1.49], p = 0.001) resulted in the largest (p ≤ 0.001) reductions, while among specific methods, fans (ES = − 7.51, 95% CI [− 11.31, − 3.71], p < 0.001) and cooling vests (ES = − 0.92, 95% CI [− 1.59, − 0.24], p = 0.008) were the most effective (Fig. 3, Table S4).

Effect on heart rate

Cooling interventions significantly (p = 0.001) reduced HR (ES = − 0.42, 95% CI [− 0.67, − 0.16], p = 0.001), with differences (p = 0.001) depending on timing (Q = 17.20, df = 3, p = 0.001) (Fig. 4, Table S5). Intermittent cooling (ES = − 1.44, 95% CI [− 2.22, − 0.66], p < 0.001) and per-cooling (ES = − 1.20, 95% CI [− 1.99, − 0.42], p = 0.003) showed the largest effects. Among cooling methods, cooling vests provided the greatest (p = 0.001) HR reduction (ES = − 1.21, 95% CI [− 1.89, − 0.53], p = 0.001), though differences among methods were not statistically significant (Q = 7.49, df = 5, p = 0.186) (Fig. 4, Table S5).

Effect on sweat rate and tolerance time

Cooling strategies significantly reduced sweat rate (ES = − 0.70, 95% CI [− 0.99, − 0.41], p < 0.001) and increased TT (ES = 1.44, 95% CI [0.50, 2.39], p = 0.003). While there were significant effects on sweat reduction (Q = 7.04, df = 2, p = 0.030) (Fig. 5, Table S6), no differences were observed for TT (Q = 3.07, df = 1, p = 0.080) (Fig. 5, Table S7). Intermittent cooling was the most effective for both outcomes (ES = − 1.16, 95% CI [− 1.61, − 0.71], p < 0.001 and ES = 2.68, 95% CI [1.01, 4.36], p = 0.002 for sweat rate and TT, respectively), whereas cold fluid ingestion had the greatest (p < 0.001) impact on sweat rate (ES = − 1.63, 95% CI [− 2.43, − 0.82], p < 0.001) (Fig. 5, Table S6), and immersion (ES = − 7.16, 95% CI [4.99, 9.33], p < 0.001) and fan (ES = − 4.71, 95% CI [3.17, 6.24], p < 0.001) use showed the highest (p < 0.001) increases in TT (Fig. 5, Table S7).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the effects of different cooling strategies applied to emergency personnel wearing PPE while working in hot environments (> 28 °C), focusing on thermophysiological responses and TT. The main finding was that cooling interventions, regardless of timing or method, significantly reduced Tcore, HR, and TS, while increasing TT. No significant effects were observed on Tskin. While cooling strategies effectively mitigated thermophysiological strain, the considerable heterogeneity in study designs and cooling techniques underscores the need for more standardized and controlled studies. These findings are primarily applicable to emergency responders engaged in strenuous physical activity while wearing thermally restrictive PPE (e.g., firefighters, military personnel, and police officers). Caution is warranted when extrapolating results to medical emergency workers, as their PPE characteristics and physical demands may differ substantially.

Cooling timing

Findings indicate that intermittent cooling (applied during rest intervals between successive work bouts) and per-cooling (implemented during work activity) were the most effective strategies for reducing Tskin, HR, TS, as well as for increasing TT. These results are consistent with previous studies in sports settings, which suggest that cooling during exercise enhances performance and delays thermal fatigue36,52,67,68. The efficacy of these strategies likely stems from improved heat dissipation via the skin, reduced peripheral blood flow, and enhanced cardiovascular stability, ultimately resulting in lower HR responses69. However, the effectiveness of cooling interventions is influenced by factors such as cooling capacity, application site, and the magnitude of thermophysiological strain experienced by the individuals36,67.

The moderate and non-significant effect of intermittent cooling on Tcore (ES = − 0.44, p = 0.143), despite its large effects on Tskin and HR (ES = − 8.69 and − 1.44, respectively; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2), may be attributed to methodological variability within this subgroup. For instance, three studies employing external cooling methods (i.e., vests, forearm immersion, or mixed approaches) showed large effects on Tcore(ES > − 1.00)25,37,42. In contrast, three studies using fluid ingestion (15 °C) or fan-based cooling reported no meaningful effect (ES < 0.00)33,41,65.

These discrepancies contrast with findings from the sports science literature, where cooling strategies have consistently demonstrated positive effects on thermophysiological parameters36,52,70. One key distinction lies in environmental and clothing conditions. Athletes typically wear minimal clothing in environments conducive to heat dissipation, while emergency personnel operate under greater thermal strain due to the use of encapsulating PPE12. This gear (including protective clothing, helmets, gloves, and boots) effectively shields against external hazards but creates a microenvironment that impairs radiative and convective heat loss, and significantly restricts sweat evaporation71. This may explain the attenuated effectiveness of certain strategies in emergency contexts. For example, while pre-cooling or fluid ingestion may reduce Tcore and improve endurance performance in athletes36,52,72, their impact appears limited in emergency responders, where PPE reduces evaporative efficiency and promotes heat retention23,28.

Pre-cooling, has been extensively studied in sports settings, where it reduces thermophysiological strain by increasing the body’s heat storage capacity before exercise22,26,36,52,70. Its effectiveness appears more pronounced at environmental temperatures above 26 °C70. In the present study, pre-cooling produced a small but significant reduction in Tcore (ES = − 0.40), a paradoxical increase in Tskin (ES = 1.14), and no meaningful effect on HR (ES = 0.05). Several factors may explain these findings. First, the average protocol duration in the included studies was 60 min, whereas previous literature suggests that the pre-cooling is most effective for shorter exercise bots (< 40 min)26,70,72. Second, the intensity and duration of the cooling interventions may have been insufficient to counteract the high metabolic heat production during exercise, especially under PPE, which impairs heat dissipation and promotes heat retention12. Although pre-cooling can transiently reduce Tskin, this effect may reverse once exercise begins, particularly when PPE is worn. The rapid accumulation of metabolic heat, combined with restricted evaporative cooling, can lead to a rebound increase in Tskin73. Therefore, the elevated Tskin observed in some studies may reflect a delayed but pronounced thermal rebound. This opposing effect across studies likely contributed to the non-significant pooled result for Tskin, as divergent subgroup trends diluted the overall effect and increased heterogeneity.

Post-cooling is applied after exercise in hot conditions to promote recovery, reduce muscle soreness, and accelerate body cooling52. This strategy is particularly relevant for emergency personnel, who experience high metabolic loads and PPE-induced heat retention, leading to continued heat accumulation even 10–15 min after activity cessation18,24. Passive recovery alone is often insufficient to return Tcore to pre-exposure levels. A recent review on post-exercise cooling in PPE-wearing workers18 reported Tcore change rates ranging from − 0.018 and + 0.010 °C/min following passive recovery (e.g., resting, removing protective clothing, seeking shade). Notably, some of these values indicate passive warming rather than cooling. These rates imply that reducing Tcore by 1.0 °C could require at least 56 min, and in some hot and humid environments, body temperature may even continue to rise18. Given that emergency workers often undergo multiple deployments within a single shift, implementing active post-cooling strategies becomes essential to mitigate residual thermophysiological strain and support recovery23,28. Our analysis confirms that post-cooling had a moderate and significant effect on reducing Tcore (ES = − 0.61), Tskin (ES = − 3.71), and HR (ES = − 0.55), reinforcing its role as an effective recovery modality in high-risk occupational settings.

Cooling methods

To optimize heat dissipation and performance, cooling techniques are typically classified as either internal (e.g., cold fluid ingestion, ice slurry, menthol beverages) or external (e.g., cooling vests, ice packs, cold-water immersion, fan)67. In this meta-analysis, mixed-method cooling emerged as the most effective approach for reducing Tcore (ES = − 1.07), Tskin (ES = − 1.69), HR (ES = − 0.70), and TS (ES = − 0.94). These findings align with previous research showing that combining cooling techniques provides greater physiological and perceptual benefits compared to single-method approaches49,69,74.

Despite its efficacy in reducing thermophysiological strain, the effect of mixed-method cooling on TT could not be assessed, as none of the included studies evaluated TT as an outcome. However, evidence from sports science suggests that mixed-method cooling can significantly enhance performance under heat stress26,52. For example, studies conducted in high-temperature environments (35 °C, 50% RH) have shown that using ice vests (− 20 °C), phase-change cooling vests (14 °C), or combining ice vests and ice slurry ingestion can significantly reduce HR, Tskin, and rectal temperature, while increasing TT by ~ 20 min compared to control conditions75. Given this demonstrated effectiveness in athletic populations, it is plausible that mixed-method cooling may also improve TT in emergency personnel. However, further research is required to confirm this effect in occupational settings where environmental temperatures exceed 28 °C.

Among the individual cooling methods, cooling vests demonstrated the most substantial effects, significantly reducing Tcore (ES = − 0.91), Tskin (ES = − 0.92), and HR (ES = − 1.21), while increasing TT (ES = 0.87). External cooling methods that cover large body surface areas appear particularly effective for thermoregulation and performance enhancement52. Their efficiency depends on several factors, including cooling capacity, coverage, garment fit (to optimize heat conduction), and duration of application (ideally > 20 min)69. Studies have shown that ice vests outperform phase-change gel vests due to their higher heat absorption capacity and more effective heat exchange via the blood pool beneath the skin surface36,68,69.

Another widely used external method is forearm and hand immersion in cold water, a strategy commonly employed for recovery by structural firefighters24. This technique promotes heat dissipation through superficial blood vessels, effectively reducing Tcore and cardiovascular strain23. Despite the limited surface area involved, the high vascularization of the hands and forearms allows efficient cooling23. In this review, forearm/hand immersion produced moderate-to-large effects in reducing Tcore (ES = − 0.75), Tskin (ES = − 4.52), and HR (ES = − 1.03), and increased TT (ES = 7.16). However, generalizability is limited, as only one study assessed its impact on TT40.

Fan cooling (i.e., forced convection) yielded a very large effect on Tskin (ES = − 7.51, p < 0.001), and a large but non-significant effect on HR (ES = − 1.17), while having minimal influence on Tcore (ES = 0.13). This discrepancy may reflect the small number of studies included (n = 2 for Tcore and n = 3 for HR) or the limited applicability of fan-based strategies in emergency scenarios. Fans enhance evaporative and convective heat loss, which explains their localized effect on Tskin76. However, unlike in athletic contexts, fan cooling did not significantly influence deeper thermophysiological parameters in emergency personnel. This may be due to reduced efficacy in humid or extremely hot environments, where ambient temperatures can exceed Tskin and limit convective cooling efficiency24.

Among internal cooling methods, ice slurry ingestion (or crushed ice beverages) is considered a practical and accessible strategy due to its minimal setup time, ease of use, and high heat absorption capacity67,77,78. In theory, ingesting cold fluids reduces Tcore, by requiring energy expenditure to warm the liquid to body temperature79. However, in this meta-analysis, no significant effect on Tcore was observed (ES = − 0.05), and none of the included studies reported effects on Tskin. This may be attributed to heterogeneity in protocols. Of the three studies included, one used cold water (15 °C)64, while only two applied true ice slurry (− 1 °C), likely reducing the average effectiveness of this method28,65. Nonetheless, ice ingestion significantly reduced TS (ES = − 1.63) and increased TT (ES = 0.93), consistent with prior findings in emergency personnel80,81.

Jay & Morris71 suggested that ingesting cold fluids or ice slurries may suppress sweat rate and cutaneous vasodilation, thereby limiting evaporative, radiative, and convective heat loss. While this may reduce cooling efficiency in athletes, such limitations may be less relevant for emergency personnel operating within the insulated microclimate created by PPE75. This could explain the absence of effects on Tcore, despite the observed performance improvements. Further research is warranted to clarify the specific conditions under which fluid ingestion strategies may be most effective in occupational settings.

This study has several limitations. First, the potential publication bias and the limited number of high-quality, adequately powered studies with rigorous randomization may affect the generalizability of the findings. Second, heterogeneity in methodologies, cooling intensities, and application timing likely contributed to inconsistent outcomes across studies. Third, practical challenges in blinding participants to cooling interventions may have introduced placebo effects that could not be fully controlled. Finally, expanding future reviews to include all relevant studies, regardless of participant occupation, may provide broader insight into the general efficacy of cooling strategies.

Practical considerations

The findings of this meta-analysis highlight the efficacy of mixed-method cooling strategies in reducing heat stress among emergency personnel. Combining ice vests with forearm and hand immersion or ice slurry ingestion appears particularly effective when applied intermittently during deployment breaks. Ice slurry ingestion also contributes to hydration and energy maintenance, especially when supplemented with electrolytes and carbohydrates. Similarly, wearing an ice vest during activity (per-cooling) is highly effective in attenuating thermophysiological strain.

Despite these physiological benefits, cooling vests and cold-water immersion may present logistical challenges that limit their widespread implementation in operational settings. However, with appropriate planning and support, such methods could be integrated as post-cooling strategies to accelerate recovery after deployments. While re-cooling is often less feasible due to the unpredictability nature of emergency work, during standby periods, personnel may benefit from ingesting ice slurry to lower body temperature and maintain hydration. This approach is especially relevant for wildland firefighters, who frequently operate in successive shifts and may have opportunities to implement pre-cooling protocols such as ice slurry ingestion or ice vest use prior to deployment81.

Although advanced cooling strategies offer clear physiological advantages, their adoption in the field remains limited. Surveys indicate that emergency personnel primarily rely on basic heat mitigation practices (~ 90%), such as resting in shaded areas, drinking cold water, and removing PPE, while fewer than 15% report using advanced cooling strategies82,83. This discrepancy may be attributed not only to logistical and resource constraints but also to organizational inertia and limited awareness of available options84.

Cooling interventions should be tailored to operational contexts, accounting for factors such as deployment duration, environmental heat stress, and individual worker characteristics. Ultimately, a cultural shift within emergency organizations is needed to promote the integration of active cooling strategies, particularly in light of rising global temperatures. Facilitating the practical implementation of these evidence-based interventions is essential to enhance heat stress management and protect the health and performance of emergency personnel.

Conclusion

Cooling strategies are effective in modulating core temperature, skin temperature, heart rate, sweat loss, and tolerance time in emergency personnel exposed to high heat stress while wearing PPE. Intermittent and per-cooling strategies, especially when implemented through mixed-method approaches such as ice vests combined with forearm immersion or ice slurry ingestion, demonstrated the greatest efficacy. However, the most effective interventions often require time, equipment, and logistical planning, which may not always be feasible during emergency operations. In this context, the application of cooling strategies before or after deployments may offer practical alternatives for mitigating thermal strain. These findings provide a foundation for the development of optimized cooling protocols that enhance safety, sustain performance, and improve heat stress resilience in high-exertion occupational environments.

Data availability

The datasets gathered in the present study are considered for sharing upon reasonable requests to the corresponding authors.

References

Plat, M. J., Frings-Dresen, M. H. W. & Sluiter, J. K. A systematic review of job-specific workers’ health surveillance activities for fire-fighting, ambulance, Police and military personnel. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 84 (8), 839–857 (2011).

Nevola, V. R., Lowe, M. D. & Marston, C. A. Review of methods to identify the critical job-tasks undertaken by the emergency services. Work 63, 521–536 (2019).

Horn, G. P., Blevins, S., Fernhall, B. & Smith, D. L. Core temperature and heart rate response to repeated bouts of firefighting activities. Ergonomics 56 (9), 1465–1473 (2013).

Rodríguez-Marroyo, J. A. et al. Physiological work demands of Spanish wildland firefighters during wildfire suppression. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 85 (2), 221–228 (2012).

Callender, N., Ellerton, J. & Macdonald, J. H. Physiological demands of mountain rescue work. Emerg. Med. J. 29 (9), 753–757 (2012).

Willi, J. M., Horn, G. P. & Madrzykowski, D. Characterizing a firefighter’s immediate thermal environment in live-fire training scenarios. Fire Technol. 52 (6), 1667–1696 (2016).

Carballo-Leyenda, B. et al. Characterizing wildland firefighters’ thermal environment during live-fire suppression. Front. Physiol. 10, 1–8 (2019).

Cheung, S. S., McLellan, T. M. & Tenaglia, S. The thermophysiology of uncompensable heat stress physiological manipulations and individual characteristics. Sports Med. 29 (5), 329–359 (2000).

Stewart, I. B., Rojek, A. M. & Hunt, A. P. Heat strain during explosive ordnance disposal. Mil Med. 176, 959–963 (2011).

Maley, M. J. et al. Extending work tolerance time in the heat in protective ensembles with pre- and per-cooling methods. Appl. Ergon. 85, 103064 (2020).

Barr, D., Gregson, W. & Reilly, T. The thermal ergonomics of firefighting reviewed. Appl. Ergon. 41 (1), 161–172 (2010).

Carballo-Leyenda, B. et al. Fractional contribution of wildland firefighters’ personal protective equipment on physiological strain. Front. Physiol. 9, 1–10 (2018).

Petruzzello, S. J. et al. Perceptual and physiological heat strain: examination in firefighters in laboratory- and field-based studies. Ergonomics 52 (6), 747–754 (2009).

Butts, C. L. et al. Physiological and perceptual effects of a cooling garment during simulated industrial work in the heat. Appl. Ergon. 59, 442–448 (2017).

Hall, A. et al. Spatial analysis of outdoor wet bulb Globe temperature under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios for 2041–2080 across a range of temperate to hot climates. Weather Clim. Extrem. 35, 100420 (2022).

Newth, D. & Gunasekera, D. Projected changes in wet-bulb Globe temperature under alternative climate scenarios. Atmosphere 9 (5), 187 (2018).

Hunt, A. P. et al. Climate change effects on the predicted heat strain and labour capacity of outdoor workers in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20 (9), 5675 (2023).

Brearley, M. et al. A systematic review of post-work core temperature cooling rates conferred by passive rest. Biology 12 (5), 1–16 (2023).

Hadid, A. et al. Effect of a personal ambient ventilation system on physiological strain during heat stress wearing a ballistic vest. Eur J. Appl. Physiol 311–319 (2008).

Alhadad, S. B., Tan, P. M. S. & Lee, J. K. W. Efficacy of heat mitigation strategies on core temperature and endurance exercise: a meta-analysis. Front Physiol 10 (2019).

Aoyagi, Y., McLellan, T. M. & Shephard, R. J. Effects of endurance training and heat acclimation on psychological strain in exercising men wearing protective clothing. Ergonomics 41 (3), 328–357 (1998).

Bongers, C. C. W. G. et al. Precooling and percooling (cooling during exercise) both improve performance in the heat: a meta-analytical review. Br. J. Sports Med. 49 (6), 377–384 (2015).

Brearley, M. & Walker, A. Water immersion for post incident cooling of firefighters; a review of practical fire ground cooling modalities. Extrem Physiol. Med. 4 (1), 1–13 (2015).

McEntire, S. J., Suyama, J. & Hostler, D. Mitigation and prevention of exertional heat stress in firefighters: a review of cooling strategies for structural firefighting and hazardous materials responders. Prehosp Emerg. Care. 17 (2), 241–260 (2013).

Fullagar, H. H. K. et al. Cooling strategies for firefighters: effects on physiological, physical, and visuo-motor outcomes following fire-fighting tasks in the heat. J. Therm. Biol. 106, 103236 (2022).

van de Kerkhof, T. M. et al. Performance benefits of pre- and per-cooling on self-paced versus constant workload exercise: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 54 (2), 447–471 (2024).

Barr, D., Gregson, W., Sutton, L. & Reilly, T. A practical cooling strategy for reducing the physiological strain associated with firefighting activity in the heat. Ergonomics 52 (4), 413–420 (2009).

Walker, A. et al. Cold-water immersion and iced-slush ingestion are effective at cooling firefighters following a simulated search and rescue task in a hot environment. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 39 (10), 1159–1166 (2014).

Bennett, B. L., Hagan, R. D., Huey, K. A. & Williams, F. Use of a cool vest to reduce heat strain during shipboard firefighting. Naval Health Res. Cent. (1994).

Frim, J. & Morris, A. Evaluation of personal cooling systems in conjunction with explosive ordnance disposal suits. Def. Civ. Inst. Environ. Med. 1–64 (1992).

Gao, C., Kuklane, K. & Holmér, I. Cooling vests with phase change materials: the effects of melting temperature on heat strain alleviation in an extremely hot environment. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 111, 1207–1216 (2011).

Hagan, R. D., Huey, K. A. & Bennett, B. L. Cool vests work under firefighting ensemble. Def. Tech. Inf. Cent. (1994).

Carter, J. B. Effectiveness of rest pauses and cooling in alleviation of heat stress during simulated fire-fighting activity. Ergonomics 42 (2), 299–213 (1999).

Carter, J. M. et al. Strategies to combat heat strain during and after firefighting. J. Therm. Biol. 32 (2), 109–116 (2007).

Colburn, D. et al. A comparison of cooling techniques in firefighters after a live burn evolution. Prehosp Emerg. Care. 15 (2), 226–232 (2011).

Tyler, C. J., Sunderland, C. & Cheung, S. S. The effect of cooling prior to and during exercise on exercise performance and capacity in the heat: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 49 (1), 7–13 (2015).

Constable, S. H. et al. Intermittent microclimate cooling during rest increases work capacity and reduces heat stress. Ergonomics 37 (2), 277–285 (1994).

Barr, D., Reilly, T. & Gregson, W. The impact of different cooling modalities on the physiological responses in firefighters during strenuous work performed in high environmental temperatures. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 111 (6), 959–967 (2011).

Hostler, D. et al. Comparison of active cooling devices with passive cooling for rehabilitation of firefighters performing exercise in thermal protective clothing: a report from the fireground rehab evaluation (FIRE) trial. Prehosp Emerg. Care. 14 (3), 300–309 (2010).

Selkirk, G. A., McLellan, T. M. & Wong, J. Active versus passive cooling during work in warm environments while wearing firefighting protective clothing. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 1 (8), 521–531 (2004).

Yeargin, S. et al. Physiological and perceived effects of forearm or head cooling during simulated firefighting activity and rehabilitation. J. Athl Train. 51 (11), 927–935 (2016).

Hemmatjo, R. et al. The effect of practical cooling strategies on physiological response and cognitive function during simulated firefighting tasks. Health Promot Perspect. 7 (2), 66–73 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Efficacy of cooling garments on exertional heat strain recovery in firefighters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Text. Res. J. 92, 4521–4535 (2021).

Tetzlaff, E. J. et al. Practical considerations for using personal cooling garments for heat stress management in physically demanding occupations: a systematic review and meta-analysis using realist evaluation. Am. J. Ind. Med. 68, 3–25 (2025).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71 (2021).

Son, S. Y. et al. Comparison of firefighters and non-firefighters and the test methods used regarding the effects of personal protective equipment on individual mobility. Appl. Ergon. 45, 1019–1027 (2014).

Chan, A. P. C., Song, W. & Yang, Y. Meta-analysis of the effects of microclimate cooling systems on human performance under thermal stressful environments: potential applications to occupational workers. J. Therm. Biol. 49–50, 16–32 (2015).

Keene, T. et al. Accuracy of tympanic temperature measurement in firefighters completing a simulated structural firefighting task. Prehosp Disaster Med. 30 (5), 461–465 (2015).

Casa, D. J. et al. Validity of devices that assess body temperature during outdoor exercise in the heat. J. Athl Train. 42 (3), 333 (2007).

Drevon, D., Fursa, S. R. & Malcolm, A. L. Intercoder reliability and validity of webplotdigitizer in extracting graphed data. Behav. Modif. 41 (2), 323–339 (2017).

Liberati, A. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6(7) (2009).

Bongers, C. C. W. G., Hopman, M. T. E. & Eijsvogels, T. M. H. Cooling interventions for athletes: an overview of effectiveness, physiological mechanisms, and practical considerations. Temperature 4 (1), 60–78 (2017).

Bhogal, S. K. et al. The PEDro scale provides a more comprehensive measure of methodological quality than the Jadad scale in stroke rehabilitation literature. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 58 (7), 668–673 (2005).

Ranalli, G. F. et al. Effect of body cooling on subsequent aerobic and anaerobic exercise performance: a systematic review. Strength. Cond. 24 (12), 3488–3496 (2010).

Higgins, J. P. T. et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4. Cochrane; (2023). www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Borenstein, M. et al. Introduction To meta-analysis (Wiley, 2021).

Cohen, J. S. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences 2nd edn (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988).

DerSimonian, R. & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials. 7 (3), 177–188 (1986).

Higgins, J. P. T. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327 (7414), 557–560 (2003).

Egger, M. et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315 (7109), 629–634 (1997).

Bennett, B. L. et al. Comparison of two cool vests on heat-strain reduction while wearing a firefighting ensemble. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 70, 322–328 (1995).

Ramírez, L. R. et al. Cool Vest Worn Under Firefighting Ensemble Reduces Heat Strain during Exercise and Recovery (Naval Health Research Center, 1994).

Sefton, J. M. et al. Evaluation of 2 heat-mitigation methods in army trainees. J. Athl Train. 51 (11), 936–945 (2016).

Selkirk, G. A., McLellan, T. M. & Wong, J. The impact of various rehydration volumes for firefighters wearing protective clothing in warm environments. Ergonomics 49 (4), 418–433 (2006).

Tabuchi, S. et al. Efficacy of ice slurry and carbohydrate–electrolyte solutions for firefighters. J. Occup. Health. 63 (1), 1–11 (2021).

Wallace, P. J. et al. The effects of cranial cooling during recovery on subsequent uncompensable heat stress tolerance. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 40 (8), 811–816 (2015).

Douzi, W. et al. Cooling during exercise enhances performances, but the cooled body areas matter: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 29 (11), 1660–1676 (2019).

Douzi, W. et al. Per-cooling (using cooling systems during physical exercise) enhances physical and cognitive performances in hot environments. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17(3) (2020).

Périard, J. D., Eijsvogels, T. M. H. & Daanen, H. A. M. Exercise under heat stress: thermoregulation, hydration, performance implications, and mitigation strategies. Physiol. Rev. 101 (4), 1873–1879 (2021).

Wegmann, M. et al. Pre-cooling and sports performance: a meta-analytical review. Sports Med. 42 (7), 545–564 (2012).

Jay, O. & Morris, N. B. Does cold water or ice slurry ingestion during exercise elicit a net body cooling effect in the heat? Sports Med. 48 (S1), 17–29 (2018).

Drust, B., Cable, N. T. & Reilly, T. Investigation of the effects of the pre-cooling on the physiological responses to soccer-specific intermittent exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 81 (1–2), 11–17 (2000).

Sawka, M. N. et al. Integrated physiological mechanisms of exercise performance, adaptation, and maladaptation to heat stress. Compr. Physiol. 1, 1883–1928 (2011).

Ross, M. L. R. et al. Novel precooling strategy enhances time trial cycling in the heat. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43 (1), 123–133 (2011).

Bach, A. J. E. et al. An evaluation of personal cooling systems for reducing thermal strain whilst working in chemical/biological protective clothing. Front Physiol 10 (2019).

McLellan, T., Frim, J. & Bell, D. G. Efficacy of air and liquid cooling during light and heavy exercise while wearing NBC clothing. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 70 (8), 802–811 (1999).

Brearley, M. Crushed ice ingestion-A practical strategy for Lowering core body temperature. J. Mil Veterans Health. 20 (2), 25–30 (2012).

Siegel, R. et al. Ice slurry ingestion increases core temperature capacity and running time in the heat. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 42 (4), 717–725 (2010).

Tan, P. M. S. & Lee, J. K. W. The role of fluid temperature and form on endurance performance in the heat. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 25 (S1), 39–51 (2015).

Pryor, R. R. et al. The effects of ice slurry ingestion before exertion in wildland firefighting gear. Prehosp Emerg. Care. 19 (2), 241–246 (2015).

Watkins, E. R. et al. Practical pre-cooling methods for occupational heat exposure. Appl. Ergon. 70, 26–33 (2018).

Carballo-Leyenda, B. et al. Perceptions of heat stress, heat strain and mitigation practices in wildfire suppression across Southern Europe and Latin America. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19(19) (2022).

Fullagar, H. H. K. et al. Australian firefighters perceptions of heat stress, fatigue and recovery practices during fire-fighting tasks in extreme environments. Appl. Ergon. 95, 103449 (2021).

Bach, A. J. E. et al. Occupational cooling practices of emergency first responders in the united states: a survey. Temperature 5 (4), 348–358 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors dedicate this paper to the memory of Dr. Gerardo Villa, whose contribution was fundamental not only to this research but also profoundly influenced our professional careers and personal lives. His kindness, generosity, and dedication will always remain in our memories. Additionally, the authors would like to acknowledge the support of the European Social Fund, the Operative Program of Castilla y León, and the Junta de Castilla y León through the Regional Ministry of Education for the predoctoral fellowship awarded to JG-A.

Funding

This study was funded by the IN-VESTUN/22/LE/0001 project on occupational risk prevention supported by the Consejería de Industria, Comercio y Empleo, Junta de Castilla y León (Spain). Additionally, the authors would like to acknowledge the support of the European Social Fund, the Operative Program of Castilla y León, and the Junta de Castilla y León through the Regional Ministry of Education for the predoctoral fellowship awarded to JG-A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G.-A. and B.C.-L. conceptualized the study and designed the methodology. J.G.-A. and F.G.-H. conducted the systematic review and extracted the data. B.C.-L. and J.R.-M. performed statistical analyses and data visualization. J.G.-A., J.R.-M., and B.C.-L. drafted the manuscript. G.G.-V. and J.A.R.-M. provided critical feedback, supervision, and final manuscript revision. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gutiérrez-Arroyo, J., Rodríguez-Marroyo, J.A., García-Heras, F. et al. Effectiveness of cooling strategies for emergency personnel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 15, 29492 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15636-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15636-y