Abstract

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has gained significant attention in medical imaging for its ability to leverage large amounts of unlabeled data for effective model pretraining. Among SSL methods, the masked autoencoder (MAE) has proven robust in learning rich representations by reconstructing masked patches of input data. However, pretraining MAE models typically demands substantial computational resources, especially when multiple MAE models are independently trained for ensemble predictions. This study introduces the Snap-MAE model, which integrates snapshot ensemble learning into the MAE pretraining process to optimize computational efficiency and enhance performance. The Snap-MAE model employs a cyclic cosine scheduler to periodically adjust the learning rate, enabling the capture of diverse model representations within a single training cycle and systematic “snapshotting” of models at regular intervals. These snapshot models are then fine-tuned on labeled data and ensembled to generate final predictions. Extensive experiments on two medical imaging tasks, multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease classification and cardiovascular disease diagnosis, demonstrated that Snap-MAE consistently outperforms the vanilla MAE, ViT-S, and ResNet-34 models across all performance metrics. Moreover, by producing multiple pretrained models from a single pretraining phase, Snap-MAE reduces the computational burden typically associated with ensemble learning. Its straightforward implementation and effectiveness make Snap-MAE a practical solution for improving SSL-based pretraining in medical imaging, where labeled data and computational resources are often limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The scarcity of labeled data in the medical domain poses significant challenges for developing robust deep learning models. Limited labeled data often leads to overfitting, where models perform well on training data but fail to generalize to unseen data, resulting in poor predictive performance in real-world scenarios. This limitation also introduces biases, especially when the training data lacks diversity, as models may capture patterns specific to the training set that do not represent the broader population1. The high costs and time-consuming nature of medical data labeling, particularly due to the need for clinical expertise, further exacerbate this issue, thereby limiting the availability of large labeled datasets2. Insufficient labeled data impedes the development of accurate diagnostic models, especially for rare diseases that may not be adequately represented in the training data, leading to unreliable detection3. Additionally, class imbalance in medical datasets, where certain conditions are underrepresented, can skew model predictions, reducing their effectiveness in detecting rare but critical conditions.

To address these challenges, self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a promising solution by leveraging large amounts of unlabeled data. SSL employs pretext tasks, which are artificial tasks created from the data itself, to enable models to learn meaningful and transferable feature representations without external labels. These representations capture essential characteristics and patterns within the data, making the approach both scalable and cost-effective. Consequently, the model can be fine-tuned for downstream tasks such as classification, detection, and segmentation with a smaller amount of labeled data, thus reducing the dependency on expensive and time-consuming data annotation4,5,6. Common pretext tasks in SSL include contrastive learning, clustering, and masked image modeling (MIM), all of which contribute to the model’s ability to generalize and perform effectively on new data7,8,9,10,11.

As a contrastive learning method, SimCLR is a framework that emphasizes simplicity and efficiency in SSL. It operates through four primary steps: data augmentation, feature extraction using a base encoder such as a ResNet, projection to a latent space via a small neural network, and the application of a contrastive loss to maximize agreement between different augmented views of the same image. By learning to distinguish between similar and dissimilar images, SimCLR achieves impressive performance in various visual representation tasks without the need for labeled data. SimCLR has shown that a sufficiently large batch size and effective augmentation techniques are crucial for the success of contrastive learning7. MoCo, another contrastive learning method, introduces a mechanism to maintain a large and consistent dictionary of feature representations using a momentum update. This approach addresses the memory and computation limitations of SimCLR, enabling more scalable and efficient learning. MoCo builds a dynamic dictionary with a queue and a moving average of the encoder, thus allowing the model to perform contrastive learning effectively on larger datasets. The approach of MoCo to maintaining a large and dynamic dictionary of representations ensures efficient scaling to larger datasets and longer training periods, making it highly effective for SSL in visual tasks8.

DeepCluster is a prominent clustering-based approach that iteratively clusters the features extracted by a convolutional neural network (CNN) and uses these cluster assignments as pseudo-labels to retrain the network. The process consists of alternating between clustering the learned features and using these clusters to supervise the CNN. This approach enables the model to learn meaningful visual representations without requiring labeled data, thereby making it effective for unsupervised feature learning9. As another clustering based approach, SwAV integrates clustering with contrastive learning. It simultaneously clusters the data while maintaining consistency between multiple augmented views of the same image. SwAV utilizes a “swapped” prediction mechanism, in which the model predicts the cluster assignment of one view using the feature representation from another view. This approach aids in learning robust and invariant features that are well-suited for a range of downstream tasks in computer vision10.

A commonly employed method in MIM is the use of masked autoencoders (MAE). This technique involves randomly masking a portion of an input image and training an autoencoder to reconstruct the missing patches. By learning to predict the masked patches, MAE encourages the model to learn high-level semantic representations and understand the overall context within the image. This method is particularly effective in capturing the global structure and meaningful features of visual data, making it a powerful tool for pretraining models11.

As another solution to the scarcity of labeled data, ensemble learning offers a robust solution to these challenges. By combining the predictions of multiple models, this technique enhances overall performance, particularly in scenarios where data is limited. Leveraging the diversity of models, ensemble learning effectively addresses issues such as overfitting, bias, and class imbalance, which are common when working with limited labeled datasets12. A key advantage of ensemble learning is its ability to improve predictive performance and generalization. When individual models are trained on different subsets of data or employ various learning algorithms, they capture a broader range of patterns and nuances in the data. Aggregating the predictions from these diverse models reduces the variance and bias inherent in individual models, resulting in more reliable and robust predictions. This is especially crucial in medical applications, where diagnostic accuracy is paramount.

Methods such as bagging, boosting, and stacking ensemble are employed to combine the strengths of individual models while mitigating their weaknesses. Bagging involves training multiple instances of a model on different bootstrap samples of the training data, with the final prediction being the average of these models’ outputs. This approach helps reduce variance, making it particularly effective for models prone to overfitting. Boosting, on the other hand, builds models sequentially, with each new model aiming to correct the errors of its predecessor. This process reduces both bias and variance, producing a strong learner from a series of weak ones. Stacking ensemble involves training multiple models, often of different types, and using their predictions as inputs to a meta learner, which then makes the final prediction. This approach enhances overall performance by leveraging the strengths of the various models13.

Additionally, ensemble learning effectively addresses class imbalance, a common issue in medical datasets where certain conditions are underrepresented14. Techniques such as weighted voting within the ensemble can assign greater importance to models that perform well on minority classes, ensuring more accurate detection of rare but critical conditions15. Resampling methods can also be employed to create balanced training datasets for individual models within the ensemble, further improving their ability to detect underrepresented conditions16.

Despite the evident advantages of SSL and ensemble learning, their integration in the context of SSL pretraining with ensemble methods remains limited. This limitation is attributable to several factors. Firstly, training multiple models as part of an ensemble significantly increases computational demands. In ensemble learning, each model must independently learn from the self-supervised signal, adding complexity. Considering that SSL pretraining already requires substantial resources due to large datasets and complex architectures, the additional burden of training multiple models concurrently can be prohibitive. This increase in computational cost not only affects feasibility but also limits the accessibility of SSL techniques, particularly for researchers and practitioners with limited resources. Secondly, ensemble methods, a type of supervised learning, are effective because they reduce overfitting and enhance robustness by averaging out the biases of individual models. However, in the context of SSL, where the primary goal is to learn generalized representations rather than to minimize a specific loss function, the benefits of ensemble methods may be less significant. Thirdly, ensemble methods require the storage and management of multiple model instances. In large-scale SSL frameworks, which often involve deep neural networks with millions of parameters, this requirement can exceed available memory and storage capacities. Efficiently managing the memory usage and data pipeline for an ensemble of models presents significant engineering challenges, further discouraging the adoption of ensemble learning in SSL pretraining.

Prior ensemble-based SSL approaches, such as deep ensembles where multiple models are pretrained independently, poses several challenges. First, these methods incur substantial computational overhead due to the need for repeated pretraining runs, which can be prohibitively expensive when using large architectures. Second, although model diversity is critical for ensemble effectiveness, simply training models with different seeds does not always guarantee sufficiently diverse representations, especially under identical learning conditions. Third, while performance improvements may be observed, they often come at a steep cost in terms of memory, GPU hours, and storage resources, leading to diminishing returns when balancing performance gains against resource usage. These limitations emphasize the need for a more efficient ensembling strategy that retains performance benefits without requiring multiple full pretraining cycles.

To address these challenges, this study proposes Snap-MAE, which utilizes the snapshot ensemble approach for pretraining MAEs. Snapshot ensembles, a type of ensemble method, provide a more efficient alternative to conventional ensemble techniques, which typically demand significant computational resources and storage capacity. Instead of training multiple models separately, snapshot ensembles generate an ensemble of models from different stages within a single training process, thereby reducing resource requirements while maintaining the benefits of ensemble learning. This method involves periodically saving, or “snapshotting”, the model parameters during a single training run, thereby creating a diverse set of models without the need for multiple independent training processes. This is typically achieved using a cyclical learning rate schedule, which encourages the model to explore various regions of the parameter space17. Consequently, this approach significantly reduces the computational and memory demands, making ensemble learning more feasible even when labeled data is limited.

The primary contributions of our study are as follows:

-

1.

We introduce Snap-MAE, which applies the snapshot ensemble strategy to the MAE framework, enabling multiple model variants to be obtained within a single pretraining run. This provides a more computationally efficient alternative to deep ensemble-based pretraining without sacrificing performance.

-

2.

Through experiments on multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease and cardiovascular disease tasks, we demonstrate that Snap-MAE achieves consistent performance improvements over vanilla MAE, ViT-S and other baselines. While the performance gains are sometimes modest, they are obtained without the substantial overhead of training multiple separate models.

-

3.

We demonstrate that the cyclic cosine scheduler used during pretraining enhances the diversity and effectiveness of the generated snapshots compared to the standard cosine scheduler and StepLR alternatives.

-

4.

Overall, our findings emphasize that Snap-MAE provides a practical balance between computational efficiency and performance, making it a promising choice for SSL in medical imaging applications, especially when labeled data and resources are limited.

Related works

Considering the aforementioned challenges, integrating ensemble learning with SSL presents significant difficulties. Consequently, there has been limited research dedicated to addressing these issues. However, a few studies that have explored the application of ensemble learning to SSL are highlighted below.

Ho and Wang introduced a novel approach for phase transition classification in many-body systems that leverages SSL to enhance the performance of traditional ensemble learning techniques18. Their approach involves training several SSL models independently on the same dataset and then combining their outputs to form a robust and comprehensive representation. By aggregating the representations learned by different models, the ensemble method improves both the performance and stability of the SSL system. However, this method has several potential drawbacks. Training multiple self-supervised models independently can be computationally demanding and resource-intensive, which may limit its scalability and applicability to very large datasets or complex systems. Additionally, the method heavily relies on the quality and diversity of the data subsets used for training each model, meaning that insufficient or biased data can lead to suboptimal performance.

Han and Lee proposed the EnSiam algorithm, which enhances the traditional SimSiam model for SSL by incorporating ensemble representations19. This approach is inspired by ensemble techniques used in knowledge distillation. Instead of depending on a single pair of augmented views, EnSiam generates multiple augmented samples from each instance and averages their representations to create a more stable pseudo-label and reduce the sensitivity to changes in training configurations. This use of ensemble representations leads to variance reduction, contributing to more robust training and improved model convergence. However, the EnSiam method increases computational complexity due to the need to generate and process multiple augmented samples, thereby raising overall resource demands. Moreover, the reliance on ensemble representations and the averaging of multiple views adds to the implementation complexity, potentially making integration into existing systems more challenging. Lastly, generating multiple augmentations may limit scalability, particularly when dealing with very large datasets or operating in resource-constrained environments.

Ruan et al. introduced a weighted ensemble SSL approach, offering an innovative ensemble method specifically designed for SSL20. This approach focuses on ensembling only the non-representation components of the model, such as projection heads. It involves creating an ensemble of teachers and students with different weights assigned to each, optimizing a weighted cross entropy loss during training. By restricting the ensemble to non-representation parts, the method avoids additional computational overhead during inference, making it efficient for real-world applications. This methodology has been tested with DINO and MSN models, demonstrating significant improvements in tasks such as few-shot learning on the ImageNet-1 K dataset21,22. However, the weighted ensemble method for SSL includes increased complexity in implementation, requiring careful tuning of ensemble weights and hyperparameters. The training phase is also more computationally demanding due to the need to manage multiple ensemble members and optimize their weights. Additionally, there is a potential risk of overfitting if the method is not properly regularized, particularly when the ensemble size is large.

Results

For the multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease and cardiovascular disease tasks, we conducted a comparative analysis to evaluate the performance of the proposed Snap-MAE model. The models compared with Snap-MAE include MAE, ViT-S and ResNet-34. ViT-S was selected because it shares the same framework as the encoder used in both MAE and Snap-MAE models, making it a relevant benchmark. ResNet-34 was included due to its status as a well-established CNN architecture with a parameter size (~ 22 M) comparable to that of ViT-S. MAE was also included to enable a direct comparison, as it shares the same model structure as Snap-MAE but does not utilize snapshot ensembling during pretraining.

The suffixes “random,” “IN,” “X-ray,” and “Scalo” refer to the initialization or pretraining strategy used. Specifically, “random” refers to models trained from scratch with random weights, “IN” indicates the use of weights pretrained on ImageNet dataset, and “X-ray” and “Scalo” denotes pretraining on X-ray or scalogram images, respectively.

Results for multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease task

Figures 1 and 2, along with Tables 1, S1, and S2 present the results of applying the Snap-MAE and various other models to the multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease task.

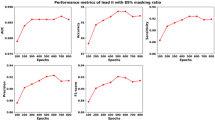

Comparison of performance metrics for MAE (X-ray) and Snap-MAE (X-ray) models across various masking ratio for multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease classification. Each subplot presents a different metric (AUC, AUPRC, sensitivity, precision, and F1-score) with error bars, illustrating performance trends as the masking ratio varies from 65 to 90%.

The performance of the MAE (X-ray) and Snap-MAE (X-ray) models varies based on the masking ratio used during pretraining, as this hyperparameter has a significant impact on performance. To investigate this, the models were evaluated across a range of masking ratios, increasing from 65 to 90% in 5% increments. Figure 1 and Table S1 compare the performance of the MAE (X-ray) and Snap-MAE (X-ray) models at these different masking ratios. As shown in Fig. 1, Snap-MAE (X-ray) model consistently demonstrates superior performance compared to MAE (X-ray) model across all masking ratios, with the exception of precision performance at a masking ratio of 85%. Furthermore, while the performance of the MAE (X-ray) model varies significantly with changes in the masking ratio, the Snap-MAE (X-ray) model exhibits relatively stable performance regardless of the masking ratio. According to Table S1, the MAE (X-ray) model achieves its best performance at a masking ratio of 85%, while the Snap-MAE (X-ray) model performs well overall but reaches its highest AUC at a masking ratio of 75%. Based on these findings, the subsequent analyses on pediatric thoracic disease task were conducted with the masking ratio set at 85% for the MAE (X-ray) model and 75% for the Snap-MAE model, and the results were compared accordingly.

Table 1 provides a comparative analysis of the AUC performance across different methods for multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease classification. Specifically, Snap-MAE (X-ray) model achieved the highest AUC in the following categories: “no finding” (0.767), “bronchitis” (0.726), “broncho-pneumonia” (0.820), “bronchiolitis” (0.724), “pneumonia” (0.843), and “other disease” (0.668), with a weighted mean AUC of 0.761. In comparison, the MAE (X-ray) model achieved mean AUC values of 0.747, 0.710, 0.805, 0.692, 0.812, and 0.643 for the same categories, respectively, with a weighted mean AUC of 0.740. The ResNet-34 (random), ViT-S (random), ResNet-34 (IN), ViT-S (IN), ResNet-34 (X-ray), and ViT-S (X-ray) models consistently exhibit lower performance across all disease classes compared to the Snap-MAE (X-ray) and MAE (X-ray) models. Overall, in terms of AUC, the Snap-MAE (X-ray) model consistently outperforms the MAE (X-ray), ViT-S, and ResNet-34 models across all categories.

Figure 2 and Table S2 present a comparison of performance measures across different methods for multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease classification. When comparing the ResNet-34 models to the ViT-S models, it is evident that the ViT-S models generally exhibit lower performance. Even the best-performing ViT-S model, ViT-S (X-ray), only achieves a performance level comparable to the ResNet-34 (random) model, which is the lowest-performing among the ResNet-34 models. When these models are compared to the MAE (X-ray) and Snap-MAE (X-ray) models, it becomes clear that the latter two models significantly outperform both ResNet-34 and ViT-S models. However, in terms of sensitivity, the ResNet-34 (X-ray) model exhibits slightly better results than the Snap-MAE (X-ray) model, achieving a sensitivity of 0.746 compared to Snap-MAE’s 0.742. When comparing MAE (X-ray) to Snap-MAE (X-ray) models, Snap-MAE model consistently demonstrates outstanding performance. Notably, Snap-MAE (X-ray) achieves an AUC of 0.761, which is higher than the 0.740 achieved by MAE (X-ray) model. Additionally, the Snap-MAE (X-ray) model shows better AUPRC (0.623 compared to 0.603 for the MAE (X-ray) model), precision (0.558 versus 0.550 for the MAE (X-ray) model) and F1-score (0.615 versus 0.602 for the MAE (X-ray) model).

These results suggest that integrating snapshot ensembling during MAE pretraining contributes to enhanced performance stability and generalization, particularly in the context of multi-labeled disease classification, where label overlap and inter-class ambiguity are common.

Results for cardiovascular disease task

Figures 3 and 4, along with Tables 2, 3, and S3 through S9, show the results of employing the Snap-MAE and various other models, in the cardiovascular disease task.

Comparison of AUC, AUPRC, accuracy, sensitivity, precision, and F1-score for MAE (Scalo) and Snap-MAE (Scalo) models across different masking ratios on Lead II ECG signal. Each subplot shows a different metric (AUC, AUPRC, sensitivity, precision, and F1-score) with performance trends from 65 to 90% masking ratio, representing the consistent improvement of Snap-MAE over MAE across most settings.

Comparison of performance metrics across models for cardiovascular disease classification using ECG Lead II. Bar plots display the performance of six models (ResNet-34, ViT-S, MAE, and Snap-MAE) across six evaluation metrics: AUC, AUPRC, accuracy, sensitivity, precision, and F1-score. The proposed Snap-MAE (Scalo) consistently achieves high scores, demonstrating superior performance compared to other baselines.

Table S3 presents the AUC and accuracy of the Snap-MAE (Scalo) model evaluated across 12 ECG leads with varying masking ratios ranging from 65 to 90%. When examining the 12 leads and masking ratios, Lead II and V1 consistently exhibit better performance. Among these, Lead II was chosen as the reference lead for performance comparison in this study. This decision was based on the fact that Lead II typically provides a clear view of the P wave and is frequently used for recording the rhythm strip, which is essential for accurately assessing cardiac rhythm23. Across masking ratio, Snap-MAE (Scalo) demonstrates robust performance across all ECG leads, with the best results generally occurring at masking ratios of 70% and 80%. Although the model maintains high AUC values across all ratios, accuracy tends to slightly decrease as the masking ratio increases beyond 85%. Since Lead II, the reference lead, showed the best performance at a 70% masking ratio, subsequent results for the Snap-MAE (Scalo) model are based on Lead II with a 70% masking ratio.

Figure 3 and Table S4 compare the performance of MAE (Scalo) and Snap-MAE (Scalo) across different masking ratios using Lead II. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the Snap-MAE (Scalo) model consistently outperforms MAE (Scalo) across all masking ratios. According to Table S4, the MAE (Scalo) model achieves its optimal performance at a masking ratio of 85%. Therefore, subsequent analyses of the MAE (Scalo) model will be based on a masking ratio of 85%, while the Snap-MAE (Scalo) model will continue to use a masking ratio of 70% as previously mentioned.

Table 2 presents the performance of Snap-MAE (Scalo) across 12 ECG leads at a 70% masking ratio. Among the leads, Lead II exhibits the highest performance, with an AUC of 0.994, an AUPRC of 0.964, an accuracy of 93.49%, a sensitivity of 0.935, a precision of 0.934, and an F1-score of 0.930. V1 follows closely with an AUC of 0.993, AUPRC of 0.958, accuracy of 93.01%, sensitivity of 0.930, precision of 0.925, and an F1-score of 0.923. Other leads demonstrated robust performance, with AUC values ranging from 0.986 to 0.994, AUPRC from 0.928 to 0.962, accuracy between 90.61% and 92.82%, sensitivity from 0.906 to 0.928, precision between 0.896 and 0.924, and F1-scores from 0.896 to 0.921.

Figure 4 and Table 3 provide a comparison of performance metrics for different models applied to Lead II in cardiovascular disease classification. Among the models evaluated, the Snap-MAE (Scalo) model achieves the highest performance across all metrics. The MAE (Scalo) model closely follows the Snap-MAE (Scalo) model, with an AUC of 0.992, au AUPRC of 0.954, an accuracy of 91.86%, a sensitivity of 0.919, a precision of 0.914, and an F1-score of 0.914. The ResNet-34 (IN) and ResNet-34 (FS) models also perform well, with AUC values of 0.991 and 0.990, respectively, but they do not reach the performance levels of Snap-MAE (Scalo) model. Both ViT-S (FS) and ViT-S (IN) models exhibit comparatively lower performance metrics, with AUC values of 0.975 and 0.982, respectively. Tables S4 through S8 provide the performance metrics for ResNet-34 (FS), ViT-S (FS), ResNet-34 (IN), ViT-S (IN), and MAE (Scalo) models across 12 different ECG leads. Overall, among these models, Lead II and V1 demonstrate slightly better performance compared to the other leads.

Comparison of learning rate schedulers in Snap-MAE: cyclic cosine vs. cosine vs. step decay

The proposed Snap-MAE model adopts a snapshot ensemble strategy during the MAE pretraining phase. Specifically, a cyclic cosine scheduler is used, which periodically increases and decreases the learning rate every 200 epochs.

To assess the impact of different learning rate schedulers, we compared the cyclic cosine scheduler with two alternative strategies: a conventional cosine scheduler and a StepLR scheduler. The cosine scheduler decays the learning rate monotonically following a cosine function without restarts, while StepLR reduces the learning rate by a fixed factor (gamma = 0.1) every 200 epochs. All other conditions, including snapshot intervals and downstream fine-tuning setup, were kept identical to those used in the cardiovascular disease task.

Figure 5 and Table S10 present the performance of Snap-MAE (Scalo) models across 12 ECG leads under the three learning rate schedules. Overall, the cyclic cosine scheduler consistently outperforms both cosine and StepLR schedulers across all metrics. These improvements are evident across all leads, with significant enhancements observed in all performance metrics. The reason for this is that the cyclic cosine scheduler helps in escaping local minima due to its cyclical training approach. The cyclic cosine scheduler facilitates a more comprehensive exploration of the loss landscape, allowing the model to move beyond suboptimal local minima and achieve better overall performance. This suggests that the cyclic cosine scheduler offers a more effective optimization strategy for the Snap-MAE model.

Effect of learning rate schedulers on Snap-MAE (Scalo) performance across 12 ECG leads. Performance of the Snap-MAE (Scalo) model is evaluated using three different learning rate schedulers: cyclic cosine, cosine, and StepLR (with gamma = 0.1 every 200 epochs). The cyclic cosine scheduler consistently outperforms the others across six metrics—AUC, AUPRC, accuracy, sensitivity, precision, and F1-score.

Effect of ensemble diversity generated by the cyclic cosine scheduler

To investigate the effect of ensemble diversity generated by the cyclic cosine scheduler, we analyzed the performance metrics of multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease task across individual snapshots taken at different epochs (200, 400, 600, and 800) for three random seeds. Table 4 summarizes the results for individual snapshots and their corresponding ensemble outputs.

For seed 42, the AUC ranged from 0.750 to 0.759, AUPRC from 0.614 to 0.622, sensitivity from 0.726 to 0.745, precision from 0.541 to 0.572, and F1-score from 0.605 to 0.614. After ensembling, these metrics showed an AUC of 0.759, AUPRC of 0.623, sensitivity of 0.736, precision of 0.552, and F1-score of 0.610, demonstrating consistent gains across all metrics. For seed 1004, the individual snapshots showed AUC values ranging from 0.747 to 0.761, AUPRC from 0.610 to 0.625, sensitivity from 0.708 to 0.764, precision from 0.541 to 0.573, and F1-score from 0.594 to 0.617. The ensemble improved these results to an AUC of 0.765, AUPRC of 0.627, sensitivity of 0.739, precision of 0.572, and F1-score of 0.616. Similarly, for seed 2023, AUC values ranged from 0.751 to 0.758, AUPRC from 0.613 to 0.617, sensitivity from 0.747 to 0.756, precision from 0.544 to 0.552, and F1-score from 0.615 to 0.618. The ensemble yielded an AUC of 0.760, AUPRC of 0.618, sensitivity of 0.751, precision of 0.549, and F1-score of 0.619. The mean AUC across the three ensembles was 0.761 (± 0.003), with corresponding AUPRC, sensitivity, precision, and F1-scores of 0.623 (± 0.005), 0.742 (± 0.008), 0.558 (± 0.013), and 0.615 (± 0.005), respectively. These results emphasize the robustness and generalization capability of the ensemble approach.

The improvement in performance metrics demonstrates how the cyclic cosine scheduler facilitates diversity among snapshots, which is effectively leveraged by ensemble methods. Unlike vanilla MAE, Snap-MAE uses the cyclic cosine scheduler to generate diverse snapshot models within a single pretraining phase. This approach avoids the computational overhead of training multiple independent models while achieving superior generalization. Although the performance improvements over the best individual models are not large, they are consistent across performance metrics and validate the utility of snapshot ensembles within the MAE frameworks.

Performance analysis of alternative ensemble methods

To evaluate the effectiveness of the ensemble strategy employed in Snap-MAE, we conducted additional analyses using the multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease classification task. Specifically, we compared snapshot-based ensembles with commonly used deep ensemble methods. For the snapshot ensemble, we tested several ensemble strategies including simple averaging, weighted averaging, and greedy ensemble (with 2-set and 3-set combinations), all derived from a single training run. For the deep ensemble, we pretrained three independent MAE models using different random seeds and applied the same ensemble strategies.

For the snapshot ensemble, four checkpoints from a single training run (epochs 200, 400, 600, and 800) were used. Simple averaging computes the average of the predicted probabilities from all snapshots and selects the class with the highest mean probability as the final prediction. This method assumes that all snapshots contribute equally to the ensemble. Weighted averaging assigns weights to the predicted probabilities of each snapshot based on their individual performance, allowing snapshots with higher predictive performance to contribute more to the final prediction. Greedy ensemble is a method that iteratively selects subsets of snapshots to maximize the ensemble performance24. For this study, we evaluated 2-set and 3-set combinations for greedy ensemble, where the subsets of snapshots (from 200, 400, 600, and 800 epochs) were combined to identify the most effective ensemble configuration. For the 2-set combination, the best performance was achieved with the combination of snapshots from 200 and 400 epochs. Similarly, for the 3-set combination, the optimal performance was observed with snapshots from 200, 400, and 800 epochs. The performance metrics reported for the greedy ensemble in Table 5 correspond to these optimal combinations.

In the deep ensemble experiments, three distinct MAE models were pretrained using different random seeds. Each of these pretrained models was then fine-tuned independently under varying seed conditions. Ensemble predictions were constructed by aggregating the results from these independently trained and fine-tuned models. As shown in Table 5, the snapshot ensemble consistently outperformed the deep ensemble across AUC, AUPRC and precision. The snapshot ensemble achieved a higher AUC (ranging from 0.761 to 0.762) compared to deep ensemble (0.752 to 0.755). Similarly, its AUPRC was substantially higher (0.618–0.623 vs. 0.525), which is particularly meaningful under class-imbalanced conditions, where AUPRC provides a more informative measure than AUC. The F1-scores of the two approaches were similar, but snapshot ensemble exhibited slightly lower sensitivity.

Among the ensemble methods evaluated, weighted averaging consistently represented slightly lower performance in the snapshot ensemble setting, whereas simple averaging and greedy ensembles delivered comparable results across both ensemble types. These results suggest that snapshot ensemble, despite its lower computational burden, is not only competitive but also highly practical for ensembling in self-supervised pretraining frameworks like MAE.

It is also notable that the snapshot ensemble exhibited higher AUC and AUPRC than the deep ensemble, despite having slightly lower sensitivity. This observation indicates that snapshot ensemble produced better calibrated probability estimates and more reliable ranking of predictions across samples. Since AUC and AUPRC are threshold-independent metrics, they reflect the quality of the predicted probability distribution rather than performance at a fixed classification threshold (e.g., 0.5). Therefore, even when sensitivity is modestly reduced, the model can still achieve superior overall ranking and precision-recall tradeoffs. This explains why the snapshot ensemble yielded higher AUC and AUPRC values in this task.

Computational efficiency and resource usage of Snap-MAE

To assess computational efficiency, we provide a detailed comparison of resource usage between MAE, Snap-MAE, and deep ensemble approaches. Table 6 summarizes core computational metrics, including the number of pretraining and fine-tuning runs, total pretraining cost, number of parameters, model size, GPU memory usage, and training time per epoch.

Importantly, Snap-MAE shares the same pretraining configuration as vanilla MAE since both use the same architecture and masking-based training objective. The only difference is the learning rate scheduler: Snap-MAE uses cycle cosine, while vanilla MAE uses standard cosine. Thus, Snap-MAE does not incur any additional overhead during the pretraining phase. However, Snap-MAE does involve additional fine-tuning for each selected snapshot, typically four in our experiments. In contrast, deep ensembles require multiple independent pretraining and fine-tuning runs, multiplying both compute time and GPU resources.

As shown in Table 6, deep ensemble incur triple the compute and memory resources relative to Snap-MAE, due to the need for three full pretraining runs. All methods use the same backbone architecture (ViT-S) with approximately 22 million parameters. The GPU memory usage and FLOPs per sample are also equivalent per model. These comparisons confirm that Snap-MAE offers a computationally scalable solution for ensemble-based SSL, making it more practical for deployment in real-world applications.

Sensitivity analysis on the number of snapshots

To further understand the effect of snapshot configuration, we analyzed performance as a function of the number of snapshots used during pretraining. We evaluated three configurations: 2 snapshots (every 400 epochs), 4 snapshots (every 200 epochs), and 8 snapshots (every 100 epochs). All configurations were tested on the multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease classification task, and the corresponding results are summarized in Table 7.

Among the tested configurations, 4-snapshots achieved the highest AUC (0.761) and AUPRC (0.623), indicating a good balance between model diversity and ensemble stability. Using only 2 snapshots led to a noticeable decline in AUPRC (0.526), suggesting insufficient diversity among the ensemble members. Conversely, increasing the number of snapshots to 8 improved sensitivity (0.757) and F1-score (0.623), but resulted in a lower AUPRC (0.525), potentially due to noise or redundancy introduced by including too many snapshots.

These findings indicate the Snap-MAE is moderately sensitive to the number and interval of snapshots, particularly under class-imbalanced conditions where AUPRC is a more indicative metric.

Discussion

In this study, we propose the Snap-MAE model algorithm, which applies a snapshot ensemble technique during the pretraining of the MAE model. The proposed algorithm replaces the commonly used cosine scheduler with a cyclic cosine scheduler during pretraining and periodically snapshots the model. These snapshot-pretrained models are then fine-tuned individually, and their results are ensembled in a straightforward yet effective manner. Through experiments on multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease and cardiovascular disease tasks, we observed that Snap-MAE consistently strong results compared to baseline models, including vanilla MAE, ResNet-34, and ViT-S. Additionally, Snap-MAE outperformed the variants that used cosine or StepLR schedulers with fixed-interval snapshotting, emphasizing the importance of the scheduler selection.

This snapshot ensemble approach can be utilized for pretraining various SSL methods. However, we specifically applied it to the MAE model for the following reasons. First, the MAE model is specifically designed to learn robust representations by masking a substantial portion of the input data and reconstructing the missing elements. This approach compels the model to focus on the most informative features within the data, which is crucial in medical imaging where subtle details can be vital for accurate diagnosis. Furthermore, in the field of computer vision, contrastive learning-based pretraining methods such as MOCO, SimCLR, and BYOL have achieved state-of-the-art performance, even surpassing supervised ImageNet pretraining in some tasks7,8,25. However, in medical imaging, MIM-based pretraining approaches have recently set new performance benchmarks26,27,28. These points can be attributed to the significant differences between natural and medical images. Medical imaging protocols typically assess patients in a consistent orientation, resulting in images with high similarity across different patients29,30,31. This consistency simplifies the analysis of many critical issues but also poses a significant challenge for contrastive learning-based pretraining. Contrastive learning treats each image as a distinct class, minimizing the similarity of representations derived from different images. This approach may not work effectively for medical images because the negative pairs often appear too similar. In contrast, MIM-based pretraining excels at preserving the fine-grained textures embedded in image contexts, making it particularly suitable for pretraining in the medical domain29,32,33.

The effectiveness of Snap-MAE is closely tied to the properties of the pretraining datasets, such as diversity, size, and domain relevance. In this study, Snap-MAE was pretrained on the ChestX-ray1434, CheXpert35 and Chapman36 datasets, which are large-scale and diverse, and fine-tuned on the PediCXR37 and Chapman datasets. The large-scale and diverse nature of the ChestX-ray14 and CheXpert datasets likely contributed to Snap-MAE’s ability to learn generalized and robust feature representations. This diversity allowed the model to handle downstream tasks, such as the pediatric thoracic disease classification (PediCXR dataset) and cardiovascular disease diagnosis (Chapman dataset), with greater resilience to noise and variability. However, the limited diversity in pretraining datasets may restrict the robustness of Snap-MAE in settings with significant domain shifts or rare pathologies not well-represented in the pretraining data. The structural similarities between adult chest X-rays (used for pretraining) and pediatric chest X-rays (used for fine-tuning) likely facilitated effective transfer learning. This suggests that pretraining on datasets with domain similarity improves Snap-MAE’s robustness in downstream tasks. For the cardiovascular task, the homogeneous nature of the Chapman dataset may have posed fewer challenges, but further testing with more heterogeneous datasets would help assess robustness in varied clinical settings. The robustness of Snap-MAE, as evidenced by its consistent performance across masking ratios and ensemble configurations, can be attributed to the diversity and scale of the pretraining datasets. However, the model’s performance may vary depending on the degree of class imbalance or noise in the pretraining data. For instance, imbalanced datasets could bias the representations learned by Snap-MAE, potentially impacting its downstream performance. While Snap-MAE has shown strong robustness in the current study, testing its pretraining on smaller, less diverse datasets or datasets with significant domain shifts (e.g., cross-modality data like CT or MRI) would further elucidate the influence of dataset properties on robustness. This could provide deeper insights into the model’s adaptability and limitations.

The primary advantage of Snap-MAE is that it requires only a single pretraining run. Typically, when pretraining an SSL model, a large amount of unlabeled data is utilized to perform pretext tasks over many epochs. If multiple self-supervised models were trained independently, as suggested by Ho and Wang18, it would be computationally demanding, resource-intensive, and time-consuming. However, the Snap-MAE model allows for the acquisition of numerous pretrained backbone models from a single pretraining run, with the added benefit of potentially achieving better performance. Additionally, the implementation is straightforward, and the performance improvement is significant. By simply replacing the cosine scheduler with a cyclic cosine scheduler and snapshotting the model at predetermined intervals, the Snap-MAE model demonstrated notable performance enhancements across both tasks addressed in this study.

Nevertheless, the proposed Snap-MAE algorithm has its limitations. Although only one pretraining run is required, fine-tuning must be performed as many times as there are snapshot models. While it is true that the number of epochs required for fine-tuning is typically much smaller than those required for pretraining (in this study, both tasks involved 800 epochs of pretraining with a large amount of data and only 75 or 100 epochs of fine-tuning with a smaller dataset), the necessity of repeating fine-tuning multiple times remains a drawback. The second limitation pertains to an inherent issue with the MAE model itself. The MAE model masks patches of the input image based on the masking ratio, and the model’s performance varies accordingly. For the multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease classification task conducted in this study, the Snap-MAE model used a pretrained model with a 75% masking ratio, while the MAE model used a ratio of 85%. For the cardiovascular disease task, the Snap-MAE model employed a 70% masking ratio, whereas the MAE model used 85%. In other words, to identify the model that performs optimally, pretraining must be conducted with different masking ratios, and for the Snap-MAE model, each pretrained model must be fine-tuned according to the number of snapshots. Thus, the masking ratio becomes a new hyperparameter, requiring multiple experiments to determine the optimal value.

While these limitations present practical challenges, they also underscore the trade-offs involved in designing scalable and efficient ensemble SSL frameworks. In this context, it is important to assess how Snap-MAE balances model diversity, fine-tuning overhead, and real-world usability. Compared to deep ensembles, which require multiple independent and costly pretraining runs, Snap-MAE achieves model diversity through a single pretraining trajectory using a cyclic learning rate schedule. This reduces computational overhead without sacrificing performance. Although the diversity of snapshots may be lower than that of independently trained models, our results suggest that the induced diversity is sufficient to achieve strong ensemble performance in medical imaging tasks. Fine-tuning overhead remains a consideration, as each snapshot must be fine-tuned separately. However, because fine-tuning is relatively lightweight compared to SSL pretraining, this overhead is manageable in most practical settings. Moreover, in deployment scenarios, only a subset of snapshots—or even a single high-performing one—can be used, enabling flexible trade-offs between inference speed and accuracy.

In summary, this study introduces the Snap-MAE algorithm, a novel approach that integrates snapshot ensembles into the pretraining process of MAEs to address the challenges of computational demands and limited labeled data in the medical domain. By leveraging snapshot ensembles, Snap-MAE efficiently generates diverse model snapshots within a single pretraining run, reducing resource requirements while enhancing model generalization. Our experiments on multi-labeled pediatric thoracic diseases and cardiovascular diseases demonstrate the effectiveness of Snap-MAE algorithm in improving diagnostic accuracy and robustness, even with limited labeled data. The proposed method not only outperforms vanilla MAE pretraining but also offers a scalable solution for medical image analysis. Future work will focus on addressing the two limitations of the Snap-MAE identified in this study: the need for repeated fine-tuning per snapshot and the sensitivity to masking ratio. Additionally, extending the approach to other types of medical data and further refining the snapshot strategy may offer broader applicability and even stronger performance across diverse clinical tasks.

Methods

This study is a retrospective observational analysis utilizing publicly available datasets. To ensure transparency in the development of the predictive model, the study adheres to the guidelines outlined in the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis + Artificial Intelligence (TRIPOD-AI) statement38.

Datasets

In this study, we applied the proposed Snap-MAE to the medical domain, specifically for the classification of multi-labeled pediatric thoracic diseases and cardiovascular diseases. All data used in this research is publicly accessible. For the multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease task, we utilized the ChestX-ray14 dataset from34 and the CheXpert dataset from35 for pretraining Snap-MAE, MAE, ViT-S, and ResNet-34 models, while the PediCXR dataset from37 was used for fine-tuning the pretrained backbone models. For the classification of cardiovascular diseases, the Chapman dataset from36, comprising data from Chapman University and Shaoxing People’s Hospital in China, was employed for both pretraining and fine-tuning Snap-MAE, MAE, ViT-S, and ResNet-34 models. Ethical review and approval were waived by the Inje University Institutional Review Board for this study as it involved the analysis of anonymous clinical open data.

Multi-labeled pediatric thoracic disease dataset

For the classification of multi-labeled pediatric thoracic diseases, we employed the publicly accessible PediCXR dataset37. This dataset comprises 9,125 pediatric chest X-ray images, officially divided into training and test sets. The training set contains 7,728 images, each annotated for fifteen diseases, while the test set includes 1,397 images annotated for eleven diseases. Due to the small sample size (five or fewer samples) for six of these diseases in the test set, they were aggregated into a single category labeled “other diseases.” Additionally, four diseases present in the training set but absent in the test set were also grouped into this “other diseases” category. Consequently, the PediCXR dataset was categorized into six classes: no finding, bronchitis, broncho-pneumonia, bronchiolitis, pneumonia, and other diseases, as detailed in Table 8. We allocated 80% of the PediCXR training data for fine-tuning the pretrained networks or training new networks from scratch for comparison, with the remaining 20% used as validation data. Chest X-rays often lead to multi-labeled images because medical conditions can overlap or coexist within a single image. Therefore, in this study, predicting pediatric thoracic diseases from chest X-rays was approached as a multi-labeled classification problem. The input examples used in the experiments are illustrated in Figure S1, where each image may be associated with multiple disease labels.

Given that the PediCXR dataset is not sufficiently large for training deep learning models, we leveraged publicly available adult chest X-ray datasets, ChestX-ray14 and CheXpert, to pretrain the Snap-MAE, MAE, ViT-S, and ResNet-34 models34,35. This choice was motivated by the significant structural and textural similarities between adult and pediatric chest X-rays, resulting in minimal domain discrepancies4,39. The ChestX-ray14 dataset contains 112,120 frontal view chest X-ray images. Of these, 51,708 exhibit one or more pathologies across fourteen classes, whereas the remaining 60,412 images indicate no signs of disease. The CheXpert dataset consists of 224,316 chest X-rays with both frontal and lateral views, annotated for fourteen classes, including twelve pathologies, support devices, and no findings. We used only the frontal view images from this dataset, totaling 191,229 images. Although both datasets include labels, we did not utilize this label information during pretraining Snap-MAE and MAE models. The combined total of images for pretraining the Snap-MAE and MAE models is 303,349, as shown in Table 8.

Cardiovascular disease dataset & preprocessing

The ECG dataset utilized in this study, referred to as the Chapman dataset, was obtained from Chapman University and Shaoxing People’s Hospital in China. The dataset comprises 12-lead ECG data sampled at 500 Hz from 10,646 subjects, with each recording lasting 10 s. Professional physicians categorized these ECG signals into eleven distinct classes.

To minimize noise in raw ECG signals, a three-step preprocessing method was implemented: Butterworth low-pass filtering up to 50 Hz, baseline correction using local polynomial regression, and noise reduction via non-local means. Out of the initial 10,646 recordings, 58 were excluded from the study due to either containing only zero values or having incomplete channel data. Furthermore, among the remaining 10,588 data points, categories with a small number of recordings, a total of 152 data points, including atrial tachycardia, atrioventricular node reentry tachycardia, atrioventricular reentry tachycardia, and sinus atrial-to-atrial wander rhythm, were removed from the dataset. As a result, a total of 10,436 ECG recordings, categorized into seven distinct classes, were used in this study. During the pretraining phase, 80% of the entire dataset was used as training data, while the remaining 20% was designated as test data. For the fine-tuning phase, we allocated 80% of the training data for fine-tuning the pretrained networks or training new networks from scratch for comparison, with the remaining 20% used as validation data. Detailed information on these seven distinct ECG rhythms and their corresponding subject counts is provided in Table 8.

After preprocessing the raw ECG signals, they were converted into 2D images using the scalogram transformation method. This method was chosen over others because it effectively removes baseline wandering, power line interference, EMG noise, and artifacts. Additionally, scalograms offer joint time–frequency analysis across multiple resolutions, which enhances the interpretability of the results. To generate scalogram images, continuous wavelet transform (CWT) was applied to the ECG recordings. Specifically, the CWT utilized a Morse wavelet with a symmetry parameter of 3 (\(\upgamma =3\)) and a time-bandwidth product of 60 (\({P}^{2}=60\))40. This transformation was performed using the cwt.m function from the Wavelet Toolbox in Matlab 2020a (https://www.mathworks.com/help/wavelet/ref/cwt.html, accessed on 27 August 2024). The resulting scalogram images were saved as 300 × 300 pixel RGB images. Figure S2 illustrates examples of preprocessed ECG recordings alongside their corresponding scalogram images across the seven categories: AFIB, AF, ST, SVT, SB, SR, and SI.

Pretraining Snap-MAE model

This study proposes the Snap-MAE model, which combines snapshot ensemble techniques with the MAE model, providing a more efficient and effective approach to pretraining. This approach is straightforward, efficient, and capable of yielding significant performance improvements.

Figure 6 demonstrates the Snap-MAE process, which includes pretraining the MAE model with a snapshot ensemble using unlabeled data, followed by fine-tuning the pretrained encoder of Snap-MAE model, specifically the ViT-S model in this study, using labeled data. Figure 6 illustrates the training process for the pediatric disease task, but the same approach can be applied to the cardiovascular disease task as well. Figure 6a shows the pretraining process for MAE model with snapshot ensembles. To begin with an overview of the MAE model’s pretraining process, input images are first divided into non-overlapping 16 × 16 patches. Each patch is flattened and then transformed into a low dimensional token through linear projection, with a positional embedding added. A subset of these tokens is randomly selected based on a masking ratio between 65 and 90%, with the chosen tokens being masked. The remaining unmasked tokens are fed into a standard Transformer encoder, which consists of multiple layers of multi-head self-attention and feed-forward neural networks, along with layer normalization and residual connections to ensure stable training. The encoder tries to extract a global representation from these partially observable tokens. The encoder’s output tokens are then used to reconstruct the masked tokens in the decoder. The decoder processes the complete set of tokens by combining the encoder’s output tokens with the learnable masked tokens, applying positional embeddings to all input tokens. It then reconstructs patches at the masked positions, reshaping the output into a reconstructed image, reshaping the output into a reconstructed image, effectively creating a full image from the randomly selected unmasked tokens and the learnable masked tokens.

The MAE model is trained to minimize the mean squared errors (MSE) between the original unlabeled images (\(X\)) and their reconstructed images (\(Y\)). For an input image \(X\), it is divided into non-overlapping 16 × 16 image patches \({X}_{i}\), with some blocks \(B\) masked. \({Y}_{i}\) represents the reconstructed image patches. As shown in Eq. (1), the MSE loss is computed only for the masked patches, focusing exclusively on predicting their pixel values:

We employed the AdamW optimizer to minimize the MSE loss during pretraining phase. For a stable and faster convergence of the model, and to enhance performance, we utilized a learning rate scheduler. However, instead of conventional learning rate schedulers such as step decay or exponential decay, which monotonically decrease the learning rate for stable convergence, Snap-MAE model employed a cyclic cosine scheduler for the snapshot ensemble. The cyclic cosine scheduler oscillates the learning rate between a minimum and maximum value, following a cosine function over a fixed number of iterations. This approach encourages the model to explore different regions of the parameter space more effectively, potentially avoiding local minima and discovering better solutions. The cyclic nature also periodically increases the learning rate, providing opportunities for the model to escape shallow local minima and explore new paths.

The first step in Snap-MAE is to apply a cyclical cosine learning rate, which periodically increases and decreases, as described in Eq. (2):

where \({\alpha }_{0}\) is the initial learning rate, \(t\) is the iteration number, \(T\) is the total number of training iterations, and \(M\) is the number of cycles. In this study, for both tasks, \({\alpha }_{0}\) was set to 0.001, \(M\) to 4, and the total number of epochs to 800. The next step involves saving the model parameters at predefined intervals during the pretraining process. In this study, the encoder’s parameters were saved every 200 epochs. Each saved model represents a snapshot. After completing the pretraining process, the saved snapshots are aggregated to form an ensemble, and the final prediction is typically obtained by averaging the outputs of the individual snapshots during fine-tuning phase.

The same hyperparameters were used for pretraining both the adult chest X-rays and the scalogram images. Initially, the input images were resized to 256 × 256 pixels and standardized using the mean and standard deviation of the ImageNet dataset. We then performed random resizing and cropping (scale range: 0.5–1.0) to 224 × 224 pixels and applied horizontal flipping for data augmentation. To minimize risks such as cropping or introducing bias to informative lesions or organs, we only applied weak augmentations. The Snap-MAE model was optimized using the AdamW optimizer with parameters \({\beta }_{1}=0.9\), \({\beta }_{2}=0.99\), and a weight decay of 0.05. The Transformer blocks in the Snap-MAE model were initialized using Xavier uniform initialization. The initial learning rate was set to 1.5e-4, and the batch size was 256. The pretraining process for the Snap-MAE model was carried out over 800 epochs. The cyclic cosine learning rate and the training loss across 800 pretraining epochs are shown in Figure S3.

Fine-tuning ViT-S network

In this study, the pretrained encoder of the Snap-MAE model is based on the ViT-S network. Consequently, we fine-tune the ViT-S network. Upon completion of the pretraining process, each saved snapshot undergoes fine-tuning. In this study, the Snap-MAE model was pretrained for 800 epochs, with the learning rate cycling every 200 epochs. This resulted in four encoder snapshots being saved during the pretraining phase. Each of these snapshots was then fine-tuned individually.

Fine-tuning was performed using an end-to-end approach with labeled data as depicted in Fig. 6b. The model used for fine-tuning is the pretrained encoder of the Snap-MAE model, based on the ViT-S network. Similar to the pretraining phase, the input image is divided into 16 × 16 non-overlapping patches. However, instead of randomly masking patches, all patches are used as input. Each patch is then flattened and projected into a low-dimensional embedding space through linear projection, with positional embeddings added to retain spatial information. These embeddings are then fed into a standard Transformer encoder. Following the approach in41, a linear classifier is appended after the class token output from each ViT-S network.

For the task of predicting pediatric thoracic diseases from chest X-rays, the classification is treated as a multi-label problem since each input example can be associated with multiple disease labels, as shown in Figure S1. To address this, the final fully connected layer in the ViT-S network was replaced with a fully connected layer that generates a 6-dimensional output. An elementwise sigmoid nonlinearity was then applied to this output, representing the predicted probability of each thoracic disease39. The loss function was modified to optimize the mean of binary cross-entropy (BCE) losses, and the ViT-S network was optimized to minimize the BCE loss42.

For the task of classifying cardiovascular diseases from scalogram images, fine-tuning was performed on labeled scalogram images for each lead. The scalogram image patches were input into the Transformer encoder. The processed output tokens were then passed through a fully connected layer that produced seven output units, corresponding to the number of classes in the multiclass classification task. The output was a vector of scores, which are converted into probabilities using a softmax function. The softmax function normalizes these scores so that they summed to one, providing the predicted probability distribution over all the classes.

After classifying pediatric thoracic or cardiovascular diseases, the probabilities for each class were obtained using either sigmoid or softmax functions. The predicted probabilities from each model were aggregated for each test sample, and the average probability for each class was calculated by averaging the probabilities predicted by all snapshot models, as shown in Eq. (3):

where \(x\) is a test sample and \({h}_{j}\left(x\right)\) represents the sigmoid or softmax score from snapshot model \(j\). The final prediction was made based on these averaged probabilities. For multi-label classification, sigmoid activation was applied, and a threshold was used to determine the presence or absence of each class. For multiclass classification, softmax activation was used, and the class with the highest averaged probability was selected as the predicted class. This approach leverages the strengths of each individual model, often resulting in improved overall performance.

For both pediatric thoracic and cardiovascular disease tasks, the ViT-S network was optimized using the AdamW optimizer with parameters \({\beta }_{1}=0.9\), \({\beta }_{2}=0.99\), and a weight decay of 0.05. In the pediatric thoracic disease task, the initial learning rate was set to 2.5e-3 with a cosine scheduler, and the batch size was 128. Fine-tuning was performed for 75 epochs, including a warm-up period of 5 epochs, with each experiment repeated three times using different random seeds for weight initialization. For the cardiovascular disease task, the initial learning rate was fixed at 1e-3, and the batch size was 32. Fine-tuning was conducted for 100 epochs in a single experiment. Both tasks utilized a layer-wise learning rate decay of 0.55, a RandAug magnitude of 6, and a DropPath rate of 0.2, as recommended in29. The code for Snap-MAE is available at: https://github.com/xodud5654/SnapMAE. The learning rate, as well as the training and validation losses over 75 epochs during the fine-tuning process, are presented in Figure S4

Performance measures

To evaluate the performance of our diagnostic models, we calculated AUC, AUPRC, accuracy, sensitivity, precision, and F1-score43,44. For the pediatric thoracic disease task, the “no finding” class constituted approximately 65% of the entire dataset, making the dataset highly imbalanced. As a result, accuracy was not computed for this task. Although the cardiovascular disease task also involved an imbalanced dataset, the imbalance was less severe, so accuracy was included in the evaluation.

Both the pediatric thoracic disease and cardiovascular disease tasks are multiclass problems. Therefore, we calculated the AUC for each disease class. The weighted averaging technique was applied to compute the average AUC, AUPRC, sensitivity, precision, and F1-score for both tasks. This approach is commonly employed in multi-label or multiclass classification tasks, as it provides a more balanced and representative performance metric when class imbalance is present. The weighted averaging technique combines performance metrics across different classes by assigning each class a weight proportional to its size in the dataset, as shown in Eq. (4):

where \(N\) is the total number of classes. \({w}_{i}\) is the weight for class \(i\), typically the number of instances in that class. \({m}_{i}\) is the performance metric such as sensitivity, precision, and F1-score for class \(i\).

Data availability

The data used in this study is publicly accessible. The ChestX-ray14 dataset can be accessed at https://nihcc.app.box.com/v/ChestXray-NIHCC, the CheXpert dataset is available at https://stanfordmlgroup.github.io/competitions/chexpert/, and the PediCXR data can be found at https://physionet.org/content/vindr-pcxr/1.0.0/. The Chapman dataset is available at https://figshare.com/collections/ChapmanECG/4560497/2. All links were verified as accessible on August 27, 2024.

References

Alzubaidi, L. et al. A survey on deep learning tools dealing with data scarcity: Definitions, challenges, solutions, tips, and applications. J. Big Data 10(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-023-00727-2 (2023).

Humbert-Droz, M., Mukherjee, P. & Gevaert, O. Strategies to address the lack of labeled data for supervised machine learning training with electronic health records: Case study for the extraction of symptoms from clinical notes. JMIR Med. Inf. 10(3), e32903. https://doi.org/10.2196/32903 (2022).

Lee, J. et al. Deep learning for rare disease: A scoping review. J. Biomed. Inform. 135, 104227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2022.104227 (2022).

Yoon, T. & Kang, D. Enhancing pediatric pneumonia diagnosis through masked autoencoders. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 6150. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56819-3 (2024).

Benčević, M., Habijan, M., Galić, I. & Pizurica, A. Self-supervised learning as a means to reduce the need for labeled data in medical image analysis. In 2022 30th European Signal Processing Conference, 1328–1332 (2022).

Qi, L. et al. Intra-modality masked image modeling: A self-supervised pre-training method for brain tumor segmentation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 95, 106343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2024.106343 (2024).

Chen, T., Kornblith, S., Norouzi, M. & Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, 1597–1607 (2020).

He, K., Fan, H., Wu, Y., Xie, S. & Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 9729–9738 (2020).

Caron, M., Bojanowski, P., Joulin, A. & Douze, M. Deep clustering for unsupervised learning of visual features. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision 132–149 (2018).

Caron, M. et al. Unsupervised learning of visual features by contrasting cluster assignments. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 9912–9924 (2020).

He, K., Chen, X., Xie, S., Li, Y., Dollár, P. & Girshick, R. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 16000–16009 (2022).

Khan, A. A., Chaudhari, O. & Chandra, R. A review of ensemble learning and data augmentation models for class imbalanced problems: combination, implementation and evaluation. Expert Syst. Appl. 122778 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122778

Zhou, Z. H. Ensemble methods: Foundations and algorithms. CRC Press (2012).

Khan, A. A., Chaudhari, O. & Chandra, R. A review of ensemble learning and data augmentation models for class imbalanced problems: Combination, implementation and evaluation. Expert Syst. Appl. 122778 (2024).

Ennaji, A., Sabri, M. A. & Aarab, A. Ensemble learning with weighted voting classifier for melanoma diagnosis. Multimed. Tools Appl. 1–17 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-024-19143-6

Wang, S., Minku, L. L. & Yao, X. Resampling-based ensemble methods for online class imbalance learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 27(5), 1356–1368. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2014.2345380 (2014).

Huang, G., Li, Y., Pleiss, G., Liu, Z., Hopcroft, J. E. & Weinberger, K. Q. Snapshot Ensembles: Train 1, Get M for Free. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2022).

Ho, C. T. & Wang, D. W. Self-supervised ensemble learning: A universal method for phase transition classification of many-body systems. Phys. Rev. Res. 5(4), 043090. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.5.043090 (2023).

Han, K., & Lee, M. EnSiam: Self-Supervised Learning with Ensemble Representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.13391 (2023).

Ruan, Y., Singh, S., Morningstar, W. R., Alemi, A. A., Ioffe, S., Fischer, I. & Dillon, J. V. Weighted Ensemble Self-Supervised Learning. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2023).

Caron, M., Touvron, H., Misra, I., Jégou, H., Mairal, J., Bojanowski, P. & Joulin, A. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 9650–9660 (2021).

Assran, M. et al. Masked siamese networks for label-efficient learning. In European Conference on Computer Vision, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 456–473 (2022).

Meek, S. & Morris, F. ABC of clinical electrocardiography. Introduction. I-Leads, rate, rhythm, and cardiac axis. Br. Med. J. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7334.415 (2002).

Caruana, R., Niculescu-Mizil, A., Crew, G. & Ksikes, A. Ensemble selection from libraries of models. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 137–144, ACM Press (2004).

Grill, J. B. et al. Bootstrap your own latent-a new approach to self-supervised learning. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 21271–21284 (2020).

Feng, R., Zhou, Z., Gotway, M. B. & Liang, J. Parts2whole: Self-supervised contrastive learning via reconstruction. In MICCAI Workshop on Domain Adaptation and Representation Transfer, 85–95 (2020).

Tang, Y. et al. Self-supervised pre-training of swin transformers for 3d medical image analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 20730–20740 (2022).

Zhou, Z., Sodha, V., Pang, J., Gotway, M. B. & Liang, J. Models genesis. Med. Image Anal. 67, 101840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2020.101840 (2021).

Xiao, J., Bai, Y., Yuille, A. & Zhou, Z. Delving into masked autoencoders for multi-label thorax disease classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 3588–3600 (2023).

Haghighi, F., Taher, M. R. H., Gotway, M. B. & Liang, J. Dira: Discriminative, restorative, and adversarial learning for self-supervised medical image analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 20824–20834 (2022).

Xiang, T., Liu, Y., Yuille, A. L., Zhang, C., Cai, W. & Zhou, Z. In-painting radiography images for unsupervised anomaly detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.13495 2(7) (2021).

Zhou, L., Liu, H., Bae, J., He, J., Samaras, D. & Prasanna, P. Self pre-training with masked autoencoders for medical image classification and segmentation. In 2023 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging, 1–6 (2023).

Chen, Z., Agarwal, D., Aggarwal, K., Safta, W., Balan, M. M. & Brown, K. Masked image modeling advances 3d medical image analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 1970–1980 (2023).

Wang, X., Peng, Y., Lu, L., Lu, Z., Bagheri, M. & Summers, R. M. Chestx-ray8: Hospital-scale chest x-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2097–2106 (2017).

Irvin, J. et al. Chexpert: A large chest radiograph dataset with uncertainty labels and expert comparison. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 33(01), 590–597 (2019).

Zheng, J. et al. A 12-lead electrocardiogram database for arrhythmia research covering more than 10,000 patients. Sci. Data 7(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0386-x (2020).

Pham, H. H., Nguyen, N. H., Tran, T. T., Nguyen, T. N. & Nguyen, H. Q. PediCXR: an open, large-scale chest radiograph dataset for interpretation of common thoracic diseases in children. Sci. Data 10(1), 240. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02102-5 (2023).

Collins, G. S. et al. TRIPOD+ AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-078378 (2024).

Yoon, T. & Kang, D. Dual-masked autoencoders: Application to multi-labeled pediatric thoracic diseases. IEEE Access 12, 87981–87990. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3418985 (2024).

Lilly, J. M. & Olhede, S. C. Generalized morse wavelets as a superfamily of analytic wavelets. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 60, 6036–6041 (2012).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2020).

Zhang, M. L. & Zhou, Z. H. A review on multi-label learning algorithms. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 26(8), 1819–1837. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2013.39 (2013).

Pan, Y. et al. A mutual inclusion mechanism for precise boundary segmentation in medical images. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 12, 1504249 (2024).

Saito, T. & Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PLoS ONE 10(3), e0118432 (2015).

Funding

This article was funded by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (Grant no. RS-2023-00249104).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Y. and D.K. conceived the main ideas, designed the study and implemented deep learning models. T.Y. and D.K. prepared all the figures and tables. D.K. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoon, T., Kang, D. Integrating snapshot ensemble learning into masked autoencoders for efficient self-supervised pretraining in medical imaging. Sci Rep 15, 31232 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15704-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15704-3