Abstract

This study presents a novel methodology for estimating Suspended Sediment Concentration (SSC) in the Mula Dam reservoir, Maharashtra, by integrating in-situ hyperspectral reflectance with Sentinel-2 satellite imagery. While conventional remote sensing techniques or field-based spectroscopy have been employed independently for SSC monitoring, this research introduces a spectral integration framework that bridges these two data sources through a transitive relation model. Field data collection was conducted from October 2021 to February 2022, during which 121 surface water samples were obtained and their spectral signatures recorded using an SVC HR-1024i Spectroradiometer. Simultaneously, Sentinel-2 MSI Level 2A images were processed to extract spectral reflectance at corresponding sampling points. Strong correlations were observed between SSC and reflectance in the Green, Red, and Red Edge 1 bands. Multiple spectral indices and band ratios were evaluated to identify optimal SSC estimators, with the combination (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red demonstrating the highest predictive capability. A spectral integration function was developed using a two-stage regression approach: first, linking observed SSC to Spectroradiometer-derived indices; second, connecting these indices to Sentinel-2 reflectance data. The resulting models were validated using linear regression, Student’s t-test, residual analysis, and k-fold cross-validation. Among all models, the (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red function achieved superior performance with an R2 of 0.80, RMSE of 8.58 mg/L, and MAPE of 19.41%. The approach was further tested for temporal SSC mapping using past Sentinel-2 imagery, revealing seasonal sediment trends. The study concludes that the proposed spectral integration method provides a robust, scalable, and transferable framework for accurate SSC monitoring in large water bodies. This advancement holds significant implications for sediment management, water quality assessment, and hydrological research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suspended Sediment Concentration (SSC) denotes solid-phase materials such as clays, silts, and fine sands suspended in water1. In fluvial systems, sediments are transported as suspended or bed load, with suspended sediments contributing around 70% of the annual load to coastal areas2. Their accumulation upstream of reservoirs causes environmental and engineering issues, including reduced storage capacity, delta formation, impaired navigation, increased seismic risk, abrasion of structures, and intake clogging3. High SSC accelerates reservoir siltation, reducing lifespan and efficiency. Sediment trapping by dams also disrupts downstream sediment flow, altering river morphology and sediment transport3. Engineering systems like canals, turbines, and valves must consider suspended particles during design and operation4. Beyond physical effects, suspended sediments carry pollutants like nutrients, pesticides, and industrial chemicals (e.g., polychlorinated biphenyls), contributing significantly to freshwater pollution by mass and volume1.

The generation of SSC in water bodies is driven by several natural and anthropogenic factors, including soil erosion, land-use changes, deforestation, agriculture, construction, and mining. These factors contribute significantly to sediment loads that impair water quality and disrupt ecosystem balance. As a result, the monitoring and management of SSC is critical for sustainable water resource governance and ecological conservation. Variability in suspended sediment concentration (SSC) can significantly impact reservoir ecology by increasing turbidity, which reduces light penetration and affects photosynthetic aquatic life. Elevated SSC levels may smother benthic habitats, disrupt fish spawning grounds, and degrade overall water quality, ultimately threatening aquatic biodiversity and the ecological balance of the reservoir ecosystem. The study supports several UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) by enabling effective monitoring of water quality, SDG 13 (Climate Action) through climate-resilient monitoring methods, and SDG 15 (Life on Land) by informing erosion control and watershed management. The implications highlight the value of integrating remote sensing with in-situ data for scalable sediment assessment5,6.

Remote sensing has become a valuable tool for quantitatively retrieving SSC from water bodies by capturing spectral reflectance, offering a fast, synoptic, and cost-effective approach for large-scale monitoring. Suspended particles affect water’s spectral properties via light absorption and scattering, enabling SSC estimation through satellite imagery7,8. This supports environmental monitoring, watershed management, and sedimentation studies. Empirical relationships between satellite reflectance and near-surface SSC have been established using sensors like Landsat-MSS, NOAA AVHRR, MODIS, SeaWiFS, RapidEye, ALOS/AVNIR-2, and Oceansat-2 OCM3,9,10,11,12. Sentinel-2, with enhanced spectral and spatial resolution, has recently shown strong potential for SSC assessment, particularly via its Green and Red bands13,14,15,16,17. Remote sensing methods for water quality assessment fall into empirical, semi-empirical, and analytical categories18. Empirical models, commonly based on regression analysis, relate satellite reflectance to SSC and have been effectively applied using both satellite and in-situ Spectroradiometry data19,20.

Although remote sensing has advanced SSC estimation in water bodies, most studies rely on either in-situ spectroscopy or satellite imagery independently, lacking a unified approach that integrates both. This limits model accuracy and scalability, especially in inland waters with low to moderate turbidity. Additionally, spectral saturation at higher SSC levels and underutilization of red-edge bands reduce estimation reliability. Therefore, a gap remains for a robust, transferable methodology that links field and satellite data. This study addresses that gap through a novel spectral integration framework using transitive relations for improved SSC monitoring. The integration of field Spectroradiometer measurements with satellite remote sensing has proven especially effective in improving SSC estimations3,19,21,22,23,24. For example, in the Godavari River, a semi-empirical algorithm using red-edge wavelengths from Sentinel-2 yielded highly accurate turbidity estimates25. Such studies demonstrate the effectiveness of combining high-resolution field spectral data with multispectral satellite imagery from platforms like MODIS, Landsat-TM, SPOT-HRV, and Sentinel-2 MSI.

Given the significance of integrated Spectroradiometry and satellite-based approaches in SSC estimation, the present study focused on assessing SSC in the Mula Dam reservoir. The main objectives were to:

-

(a)

Acquire spectral reflectance data of suspended sediment concentration (SSC) in the Mula Dam reservoir using both field-based Spectroradiometer measurements and Sentinel-2 imagery;

-

(b)

Establish quantitative relationships between in-situ SSC and reflectance values across key spectral bands;

-

(c)

Develop an integrated spectral model linking ground-based and satellite-derived reflectance for accurate SSC estimation; and.

-

(d)

Validate the developed model for its reliability and applicability in monitoring SSC over large inland water bodies.

The study employed a two-stage spectral integration process. Satellite-derived indices were first transformed into Spectroradiometer-equivalent values. These were then used in calibrated regression models—linear, quadratic, logarithmic, power, and exponential—to identify the best-fitting SSC estimation function. To explore the utility of the developed methodology, historical Sentinel-2 imagery was analyzed to assess SSC in the Mula Dam prior to the study period. This integrated approach enhances our ability to monitor suspended sediments over time and space, thereby contributing to more effective sediment management strategies for sustainable inland water systems.

Materials and methods

Study area

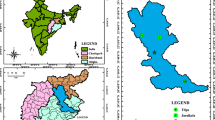

Mula Dam, also known as Dnyaneshwar Sagar Reservoir, is a dam constructed on the Mula River at Baragaon Nandur in the Rahuri tahsil of Ahmednagar district in Maharashtra State, India. The Mula River, which originates from the eastern slopes of the Sahyadri mountain range is a tributary of the Pravara River, which, in turn, is one of the tributaries of the Godavari River, a major east-flowing river in India. The Mula Dam is located at latitude 19º20’ to 19º35’ N and longitude 74º25’ to 74º36’ E, as shown in Fig. 1. The Mula Dam, with a capacity of 736.238 Mcum and a catchment area of 2,275 sq. km, serves a Cultivable Command Area of 808 sq. km through its canals, crucial for district’s domestic and irrigation needs. Its diverse fish population supports both economic and ornamental species. Assessing sediment levels ensures effective dam management, maintains water quality, supports efficient irrigation, and sustains the ecosystem, benefiting the community and environment alike.

Suspended sediment concentration data

Suspended Sediment Concentration (SSC) is the mass of fine particulate matter—such as silt, clay, and organic particles—suspended in water, typically expressed in mg/L. It is critical for assessing water quality, ecosystem health, and sediment transport. Between October 31, 2021, and February 18, 2022, five sampling campaigns at the Mula Dam reservoir yielded 121 surface water samples (0–20 cm), collected using Simple Random Sampling (SRS) in accordance with prior studies15,26. Surface reflectance, representing the upper water layer, is influenced by clarity, suspended sediments, and light characteristics. In clear water, this depth is about 0–10 cm, whereas in turbid water, it may extend up to 20 cm due to enhanced scattering and absorption by suspended sediments20,22. Highly turbid conditions can cause deeper layers (up to 20 cm) to affect surface reflectance15, though this influence decreases with higher sediment concentrations as light penetration diminishes10. Samples were GPS-tagged, treated with toluene to prevent microbial growth, and filtered for sediment separation. SSC was determined through gravimetric analysis and reported in mg/L (equivalent to ppm).

In-situ surface reflectance acquisition using spectroradiometer

The SVC HR-1024i Spectroradiometer (350–2500 nm) captured spectral responses at Mula Dam Reservoir sampling sites. Positioned 0.5 m above the water surface, it employed a 25° Field of View hyperspectral sensor connected via optical fiber. A Spectrolon panel (100% reflectance) served as a reference for incoming solar radiation. Spectral data were converted to reflectance values calibrated against the Spectrolon panel to reduce external noise. Spectral reflectance, defined as the ratio of reflected to received radiation at specific wavelengths, was measured 20 m from the shoreline between 11 am–3 pm to avoid bottom effects, shoreline vegetation, and variable solar angles. This setup minimized spectral mixing and atmospheric interference. GPS ensured accurate location tracking for visualization in Google Earth Pro. Spectral data (3 replications) were exported to SVC software for merging, overlapping, and resampling. Reflectance values (Eq. 1) were plotted against wavelength in MS Excel to generate spectral signatures, revealing reflectance characteristics of suspended sediment. Suitable wavelength ranges for SSC estimation were identified through spectral analysis.

Where, R = Spectral reflectance of target in per cent, SItarget = Spectral Irradiance of target and SIreference = Spectral Irradiance of reference panel.

Satellite data acquisition (Sentinel – 2 images)

This study employed Sentinel-2 Bottom-Of-Atmosphere (BOA) Level-2 A corrected reflectance images for retrieving suspended sediment concentration (SSC) in the Mula Dam reservoir. Sentinel-2 provides thirteen spectral bands covering the visible to shortwave infrared regions. Bands 2–4 (Blue: 458–523 nm, Green: 543–578 nm, Red: 650–680 nm) offer a spatial resolution of 10 m, while Band 1 (Coastal Aerosol: 443 nm) is available at 60 m resolution. The Red Edge bands (Bands 5–7) and Band 8 A (NIR: 785–900 nm) are provided at 20 m resolution. Level-2 A images corresponding to field sampling dates were downloaded and processed using SNAP software with the Sen2Cor plugin, which performs radiometric, geometric, and atmospheric corrections. A similar approach for SSC retrieval has been adopted in the Arabian Gulf region27. Further post-processing was conducted in ArcGIS, including conversion of reflectance values from fractional to a 10,000 scale. To minimize spectral contamination from adjacent land, reservoir boundary shapefiles were buffered to exclude edge pixels. In-situ SSC measurements were collected at least 20 m away from the shoreline, consistent with the coarsest spatial resolution of Sentinel-2, to avoid mixed-pixel effects. Sentinel-2 data have been extensively used in remote sensing applications14,28, and Level-2 A BOA reflectance products are recognized as reliable and readily available for water quality monitoring29. To ensure accurate SSC modeling, additional preprocessing steps included cloud and shadow masking using the Scene Classification Layer (SCL) from Sen2Cor, water masking using NDWI, exclusion of shoreline and mixed pixels, removal of outliers and spectrally noisy data, and band resampling to match in-situ observations. Only clean, homogeneous water pixels were utilized for model development.

Computation of spectral bands indices and band combinations for Estimation of SSC

The practice of using multiband combinations and spectral ratios or indices in empirical models through regression analyses has been well-established in the literature and demonstrated in various studies13,30. Utilizing band ratios offers a significant advantage by helping to mitigate the influence of atmospheric conditions and bidirectional reflectance distribution function effects, including Sun glint on the surface of water, as captured in the spectral response20,31. This approach effectively reduces the impact of data noise, enhancing the clarity and reliability of the spectral information related to water properties32. Table 1 shows various multiband spectral combinations and ratios/ indices along with reference/ inference, which were used to relate with suspended sediment concentration in Mula dam reservoir. Values of all given multiband spectral combinations and ratios/ indices were calculated from the spectral response received by Spectroradiometer and Sentinel – 2 MSI (BOA-L2A) satellite imagery. To obtain band values, values of band indices and band combinations calculated using ‘raster calculator’ at desired locations, recorded by GPS locations were superimposed on Sentinel 2’s band image and ‘extract values to table’ feature of Geostatistical tool of ArcMap was used.

Development of spectral integration function using validation data set

In this study, a spectral integration function was developed to estimate Suspended Sediment Concentration (SSC) by linking ground-based Spectroradiometer data with satellite-derived spectral information. Out of 121 water samples collected from the Mula Dam reservoir, 105 valid samples were used after excluding 16 due to manual errors. An 80:20 calibration-validation split was adopted, with 84 samples used for calibration and 21 for validation, selected using random number table to ensure unbiased representation. This partitioning strategy is a widely accepted practice in model development and has been employed in several SSC studies38,39,40 to ensure robust model training and evaluation.

The core of this methodology lies in the application of transitive relations41, enabling the development of two linked regression models: (a) relating observed SSC (x) to Spectroradiometer-derived spectral indices/combinations (y), and (b) linking Spectroradiometer indices (y) to Sentinel-2 BOA-derived indices/combinations (z). These models were integrated into a spectral integration function, facilitating SSC estimation from satellite data by first transforming satellite indices to their Spectroradiometer equivalents and then applying the SSC relationship. Multiple regression forms—linear, quadratic, logarithmic, power, and exponential—were tested to determine the best-fit models at both stages. The model was validated using the 21 reserved samples, demonstrating robust predictive capabilities. This approach effectively bridges satellite and ground observations, enhancing model transferability and performance for SSC monitoring in Mula Dam.

Validation and performance evaluation

The methodology for validating and evaluating the performance of the developed equations involved comparing observed SSC with estimated SSC through various methods given below.

Graphical method or visual interpretation

A simple line graph was plotted to compare observed Suspended Sediment Concentration (SSC) with estimated SSC, in alignment with established recommendations and previous studies42,43. This graphical method, also used in analogous research, assists in assessing the performance and validation of the model44.

Linear regression analysis for testing the coefficients of linear equation

Linear regression analysis45 was carried out to study the relationship between a dependent variable and an independent variable. The analysis aimed to estimate and evaluate key regression parameters, namely the intercept, slope, t-value, p-value, and the coefficient of determination (R2). Linear regression analysis was employed to examine the relationship between the dependent variable Y (Observed SSC, Mg/L) and the independent variable X (Estimated SSC, mg/L).

The regression model (Eq. 2) used is expressed as:

Where:

β0 = Intercept of the regression line.

β1 = Slope or regression coefficient of the independent variable.

ε = Random error term.

The model was developed using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method, which minimizes the sum of the squared differences between the observed and predicted values. The intercept represents the expected value of the dependent variable when the independent variable is zero, while the slope indicates the rate of change in the dependent variable for a unit change in the independent variable. Once the parameters were estimated, hypothesis testing was conducted to assess their statistical significance. The t-value was calculated for each parameter to test whether it significantly differs from zero, and the corresponding p-value was used to determine significance at a 5% level of confidence. A parameter was considered statistically significant if the p-value was less than 0.05. To assess the goodness-of-fit of the model, the coefficient of determination (R2) was computed. This value indicates the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that can be explained by the independent variable. Higher R2 values indicate a better fit of the model to the observed data. All computations were performed using Microsoft Office Excel. Different Formulae (Eqs. 3,4,5,6) involved in Linear Regression Analysis for calculation of Slope (β1), Intercept (β0), t-value for coefficients, Coefficient of determination (R2) respectively are given below:

Where,

\(SS_{res}\) = Sum of squares of residuals, \(SS_{reg}\) = Regression sum of squares, \(SS_{total}\) = Total sum of squares

Student’s t-test for testing the difference of mean of observed and estimated SSC

The mean of observed and estimated SSC values were compared using student’s t-test i.e. using the Eq. (7) given below46, for (n-2) degrees of freedom at 5% level of significance. If the tcal is less than t-table value for 19 degrees of freedom at 5% level of significance indicates the difference between means of observed and estimated is insignificant.

Performance evaluation using statistical indicators

The process of performance evaluation using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) – to quantify prediction error in original units (mg/L)47, Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) – to assess relative prediction accuracy48, and Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency Coefficient (NSE) – to evaluate how well the observed versus predicted values fit along the 1:1 line49, allowed for a comprehensive assessment of how well the equations performed in estimating SSC in the Mula Dam reservoir. Additionally, model selection criteria such as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) – used for model parsimony and penalization of over fitting – were applied to support the identification of the most appropriate and generalizable models. Universally accepted formulae for RMSE, MAPE, NSE, AIC, and BIC were used for this purpose.

Cross validation using k-fold cross-validation

To evaluate the performance and reliability of SSC prediction models, a 5-fold cross-validation approach was employed50. The dataset was randomly divided into five equal folds; in each iteration, four folds were used for training and one for validation. This process was repeated five times, ensuring each fold served once as the validation set. Performance metrics—RMSE, MAPE, and R2—were computed for each iteration, and their averages provided a comprehensive estimate of model performance on unseen data, minimizing bias from random data splitting.

Residual analysis

To further assess the predictive performance and consistency of SSC estimation models, residual analysis was performed51. Residuals, calculated as the difference between observed and predicted SSC, were evaluated using their mean and standard deviation. A mean near zero indicates balanced predictions, while a lower standard deviation suggests higher consistency and reliability. Residuals were analyzed for three models: R-NDSSI, the average spectral model [(Red + Green + Red Edge1)/3], and the ratio model [(Green × Red Edge 1)/Red]. This analysis provided deeper insights into model bias and error variability, complementing standard metrics like RMSE and R2.

Results

Distribution of sampling locations and observed SSC

Suspended sediment sampling in Mula Dam reservoir, conducted between October 31, 2021, and February 18, 2022, showed significant spatial variation in SSC, ranging from 15.62 to 137.65 mg/L. Higher concentrations were noted near river inflow zones, indicating sediment input. Figure 2 illustrates the spatial distribution of the sampling locations and the corresponding observed SSC across the reservoir during the study period. The sampling strategy ensured reasonable spatial coverage and captured sediment dynamics effectively. The analysis of the 105 valid water samples showed an average SSC of 61.43 mg/L, with a standard deviation (SD) of 32.59 mg/L and a coefficient of variation (CV) of 53.05%, indicating a moderate level of variability in suspended sediment concentrations throughout the reservoir. Both calibration and validation dataset displayed similar statistical characteristics to the overall dataset, validating their representativeness for model training and testing.

Spectral signature analysis using spectroradiometer SVC-1024i

The in-situ surface reflectance spectra captured using the SVC-1024i Spectroradiometer showed consistent shapes and amplitudes across all sampling points. As SSC increased, surface reflectance also increased, particularly in the red (650–680 nm) and red edge 1 (698–713 nm) regions, with a flat peak observed in the green region (543–578 nm), as shown in Fig. 3. These spectral traits are typical of low SSC levels. A strong positive correlation was found between SSC and reflectance in several Sentinel-2 bands, highest in the green band (R2 = 0.76), followed by red edge 1 (R2 = 0.71), red (R2 = 0.68), and moderate in the blue band (R2 = 0.50). Weaker correlations appeared in red edge 2, 3, and 4 bands (R2 = 0.39, 0.36, and 0.26) and NIR (R2 = 0.32). Figure 4 illustrates the spectral reflectance profiles for varying SSC levels. Additionally, multiple band ratios and indices were derived from Spectroradiometer data and evaluated for their statistical relationship with SSC to identify the most responsive indices for estimation.

Relationship between SSC and band indices and band ratios/ combinations derived from spectroradiometer SVC – 1024i

Several spectral indices and band combinations derived from the SVC HR–1024i Spectroradiometer were evaluated for their correlation with observed SSC in the Mula Dam reservoir.

Spectral indices

NDSSI showed weak correlation (R2 = 0.07) due to low NIR reflectance (Fig. 5a), while NSMI showed moderate correlation (R2 ≈ 0.5) (Fig. 5b). Modified indices M-NDSSI and R-NDSSI displayed strong negative correlations, with R-NDSSI achieving R2 > 0.7, making it suitable for SSC estimation (Fig. 5c, d).

Band ratios and combinations

The average of Red and Green bands (Red + Green)/2 correlated positively with SSC (R2 = 0.5–0.7) (Fig. 5e). Including Red Edge 1 in the average (Red + Red Edge 1 + Green)/3 improved correlation, yielding the highest R2 = 0.82 using a second-order polynomial fit (Fig. 5f). The Green–Red Edge 1 difference also correlated well (R2 = 0.71) with SSC under a quadratic model (Fig. 5g). The band ratio (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red was the best predictor, with R2 = 0.86 (Fig. 5h). These results highlight the potential of hyperspectral indices and band combinations for SSC estimation. Figure 5 illustrates these relationships, and Table 2 summarizes the most effective ones.

Development of relationships between different band indices/ combinations/ ratios derived from Sentinel – 2 satellite imagery and spectroradiometer SVC – 1024i

This study established strong relationships between spectral indices, combinations, and ratios from Sentinel-2 BOA imagery and Spectroradiometer SVC–1024i data for estimating SSC. Three combinations with R2 > 0.75 were selected: R-NDSSI showed a strong correlation (R2 = 0.80) using a second-order polynomial (Fig. 6a); the averaged combination (Red + Green + Red Edge 1)/3 yielded the highest R2 of 0.87 (Fig. 6b); and the ratio (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red achieved R2 values between 0.7 and 0.75, with a power function providing the best fit (Fig. 6c).

SSC estimation involved integrating (1) the relationship between spectral indices and observed SSC, and (2) the relationship between Sentinel-2- and Spectroradiometer-derived values. Validation was conducted on 21 samples (20% of the dataset), and Table 3 presents the integrated functions used.

The model achieved high predictive accuracy, with R2 > 0.80 and RMSE < 9 mg/L, consistent with previous studies. Sravanthi et al. (2013) reported an R2 of 0.84 in coastal waters, while Hossain et al. (2010) achieved 0.88 in riverine environments. Pham et al. (2018) and Pitchaikani et al. (2019) reported R2 values of 0.75 and 0.74, respectively. These findings confirm that strong SSC–spectral index correlations are possible with appropriate band combinations and regional calibration. Unlike earlier works that mainly relied on R2 and RMSE, this study adopted a more comprehensive validation approach, improving the robustness and transferability of the spectral integration method for SSC estimation in inland water bodies.

Validation and performance evaluation

To identify the most suitable band index, ratio, or combination among the three considered, the observed (determined traditionally using Gravimetric method) and estimated SSC values were evaluated through a comprehensive approach including visual interpretation, linear regression analysis for coefficient testing, Student’s t-test, performance assessment using statistical indicators, k-fold cross-validation, and residual analysis, as detailed in this section.

Visual interpretation

Visual interpretation using line graphs revealed clear differences in the performance of spectral indices for SSC estimation. R-NDSSI-based estimates (Fig. 7a (i)) showed irregular patterns and poor alignment with observed SSC, supported by low R2 values of 0.48 (with intercept) and 0.21 (without intercept) [Fig. 7a (ii)], indicating low reliability. In contrast, (Red + Green + Red Edge 1)/3 [Fig. 7b (i)] and (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red [Fig. 7c (i)] closely matched observed trends with parallel line patterns, supported by strong R2 values > 0.75 [Fig. 7b (ii), (ii)], confirming their accuracy and consistency.

Linear regression analysis for testing the coefficients of linear equation

The statistical analysis of the spectral integration functions for predicting Suspended Sediment Concentration (SSC) highlights notable differences in performance. The R-NDSSI index exhibited the weakest predictive capability, indicated by a poor fit and comparatively lower statistical significance, despite being statistically valid. In contrast, the combination (Red + Green + Red Edge 1)/3 showed a strong linear relationship with SSC, supported by a slope close to unity, a low intercept, and high significance levels. Similarly, the ratio (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red demonstrated strong predictive power with the highest statistical significance among the three. As shown in Table 4, both (Red + Green + Red Edge 1)/3 and (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red significantly outperformed R-NDSSI in SSC prediction.

The error distribution histograms (Fig. 7) show varying prediction accuracies for the spectral integration functions. R-NDSSI exhibits high variability with a wide spread of errors, indicating poor consistency in SSC estimation. The (Red + Green + Red Edge 1)/3 function has a more centred distribution with errors mostly around zero, suggesting better accuracy. The (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red function shows a relatively uniform error spread with some Skewness, indicating moderate reliability. Overall, the averaged spectral function (Red + Green + Red Edge 1)/3 demonstrates the most stable and accurate SSC predictions (Fig. 8).

Student’s t-test

Student’s t-test assessing the difference between the mean values of observed and estimated SSC found all three spectral functions to be statistically insignificant at 5% level of significance for 19 degrees of freedom. The mean SSC values estimated using Spectral Integration Function of R-NDSSI, (Red + Green + Red Edge 1)/3, and (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red were 52.53 mg/L, 62.17 mg/L, and 50.40 mg/L, respectively, compared to the observed mean SSC of 54.10 mg/L.

Performance evaluation using statistical indicators

The statistical evaluation (Table 5) of spectral integration functions for SSC estimation indicates varying performance levels. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values were lowest for the (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red function (AIC: 152.77, BIC: 154.86), suggesting it has the best model fit among the three functions. The coefficient of determination (R2) was highest for (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red (0.809), followed by (Red + Green + Red Edge 1)/3 (0.778), while R-NDSSI had the lowest R2 (0.475), indicating weaker explanatory power. The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) was lowest for (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red (8.58 mg/L), meaning it had the most accurate SSC predictions, while R-NDSSI had the highest RMSE (12.30 mg/L). The Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) was lowest for (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red (19.41%), demonstrating its higher predictive accuracy, whereas (Red + Green + Red Edge 1)/3 had the highest MAPE (26.93%), suggesting more relative errors in predictions. The Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) values were similar for all functions, with (Red + Green + Red Edge 1)/3 achieving the highest (0.80), indicating strong predictive skill.

k-Fold cross-validation

The 5-fold cross-validation results reveal that among the three spectral integration methods evaluated for estimating Suspended Sediment Concentration (SSC), the spectral integration function (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red consistently outperforms the others. It achieved the highest average R2 value of 0.62, indicating stronger predictive power, and the lowest average values for MAPE (0.24) and RMSE (12.73 mg/L), suggesting higher accuracy and lower prediction error. The method based on (Red + Green + Red Edge 1)/3 also demonstrated good performance, with an average R2 of 0.57 and reasonably low error metrics. In contrast, the R-NDSSI method showed the weakest performance, with a negative average R2 value (-0.05), implying poor correlation with observed SSC and higher prediction errors. These results (Table 6) suggest that incorporating interaction between bands, as seen in the (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red approach, enhances the model’s ability to capture the spectral characteristics associated with sediment concentration in water bodies.

Residual analysis

The residual analysis (Fig. 9) shows that the R-NDSSI model has a near-zero mean residual (0.01 mg/L), indicating an overall balance between over- and under-predictions, but its high standard deviation (19.89 mg/L) suggests significant variability in accuracy. The (Red + Green + RedEdge1)/3 model tends to under predict SSC, as indicated by its negative mean residual (-4.58 mg/L), and it also exhibits high variability (19.6 mg/L). In contrast, the (Green × RedEdge1)/Red model demonstrates the most stable performance, with a lower mean residual (2.53 mg/L) and the smallest standard deviation (13.78 mg/L), suggesting it provides the most consistent and reliable SSC predictions among the three models.

Mapping of suspended sediment concentration in Mula dam reservoir

Using the spectral integration of (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red as the most accurate estimator, spatio-temporal SSC maps of Mula Dam were generated from Sentinel-2 imagery for October 2019, February 2020, and October 2020 to February 2021 (Fig. 10). The maps revealed seasonal trends, with higher SSC in October (post-monsoon) due to increased runoff, and lower SSC in February, likely from reduced sediment transport. Elevated SSC was noted near river inflows and dendritic zones, driven by flow-induced turbulence. A limitation of the study is the potential underestimation at high SSC levels (> 100 mg/L) due to reflectance saturation in green and red bands. Long-term validation is needed to assess model reliability across seasons, and further testing is required to confirm its applicability to other water bodies with varying conditions.

Discussion

Considering methodological assumptions in alignment with previous literature has made the basis for interpretation of results. It is assumed and evidently seen that SSC significantly affects spectral reflectance, especially in red and red edge 1 bands, while the influence of other constituents like chlorophyll and organic matter is minimal. EC and pH values remained within potable limits. The water is optically deep, with negligible bottom and atmospheric effects. Spatial and temporal consistency between satellite data and field measurements is ensured. Spectral indices and cross-validation were used to enhance SSC detection and ensure model reliability without data leakage. These assumptions underpin the robustness of the spectral analysis and model development.

Spatial and Temporal variability of SSC in Mula dam

The spatial and temporal analysis of SSC in Mula Dam reservoir showed significant variability influenced by inflow dynamics and reservoir morphology. SSC ranged from 15.62 to 137.65 mg/L, with higher concentrations near river inflows due to turbulence and erosion, and lower values in central areas due to sediment settling. The average SSC was 61.43 mg/L, with calibration and validation subsets averaging 62.65 mg/L and 57.04 mg/L, respectively, consistent with inland water body patterns40. In the absence of a standard threshold, a 100 mg/L benchmark was adopted, based on prior studies reporting thresholds from 50 mg/L16 to 360 mg/L21. About 85% of SSC values fell below this limit, indicating generally low to moderate sediment levels. The 80:20 calibration-validation split supported robust model development38,39. Despite logistical constraints in large-scale sampling, the study ensured sufficient spatial coverage, highlighting the need for localized sediment monitoring strategies based on specific hydrological and morphological features.

Spectral characteristics and SSC correlation

In-situ surface reflectance spectra (Fig. 11) showed consistent trends across sampling sites, with reflectance increasing with SSC levels. Key spectral features included a peak in the red region (650–680 nm), a secondary peak in the red edge 1 region (698–713 nm), and a flat peak in the green region (543–578 nm), consistent with characteristics of suspended sediments reported in earlier studies52,53,54. For example, reflectance near 550 nm was linked to SSC levels of 5.4–29.5 mg/L52, while similar signatures at 560 and 650 nm were associated with ~ 45 mg/L SSC in the Tamar Estuary53.

Strong correlations were found between SSC and reflectance in the green (R2 = 0.76), red edge 1 (R2 = 0.71), and red (R2 = 0.68) bands, confirming their predictive relevance in low to moderate sediment conditions16,30,55. NIR and higher-order red edge bands showed weaker correlations, likely due to limited light penetration and interference from chlorophyll or organic matter56,57. Supporting studies include Salami et al. (2024), who found an R2 of 0.74 for the Red/Green (B4/B3) ratio in Iran’s Sefidroud River using Landsat 858, and Mahdawi et al. (2025), who used Sentinel-2 to estimate SSC in Afghanistan’s Laghman River with an R2 of 0.62 based on the Band 5/Band 1 ratio during flood events59.

Spectral indices and band combinations

The performance of spectral indices and band combinations provided valuable insights. NDSSI showed low correlation due to weak NIR reflectance response, making it less effective for low SSC detection. In contrast, NSMI, M-NDSSI, and especially R-NDSSI performed better, with R-NDSSI’s strong negative correlation highlighting the effectiveness of visible and red-edge bands for SSC estimation. Among band combinations, (Red + Red Edge 1 + Green)/3 achieved an R2 of 0.82, demonstrating the utility of averaging to integrate scattering and absorption effects and reduce spectral noise and complexity60,61. This approach has been successfully applied in vegetation and water quality studies62,63. The ratio (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red yielded the highest R2 (0.86), benefiting from the green band’s scattering sensitivity, red band’s absorption, and red edge’s transition features63,64,65. Sentinel-2’s red edge bands (e.g., Band 5 at 705 nm) support such ratios in sediment monitoring. These findings are consistent with prior research linking similar combinations to high correlations with in-situ TSS22,56.

Non-linear modelling and spectral saturation

Estimating SSC often requires non-linear modeling due to the curvilinear nature of spectral reflectance, especially at higher concentrations (> 100 mg/L). While reflectance increases linearly at low to moderate SSC levels due to scattering, it saturates at higher levels because of multiple scattering and absorption, reducing water-leaving radiance and resulting in a non-linear or quadratic relationship20,22,66. The red band is particularly prone to saturation—initially increasing in reflectance before plateauing—whereas the red-edge band maintains better sensitivity across wider SSC ranges, though it also shows non-linear behavior7,15. Consequently, quadratic models are often used in turbid waters where linear models are inadequate57,58. Recent studies58,59 combining satellite imagery with field sampling have reinforced this approach. Salami et al. used Landsat 8’s Red/Green ratio to predict SSC in Iran’s Sefidroud River, and Mahdawi et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of Sentinel-2’s Red Edge 1/Coastal Aerosol ratio during floods in Afghanistan’s Laghman River. These findings emphasize the need for appropriate spectral band selection and integrated approaches to improve SSC estimation, particularly in capturing the non-linear responses in green, red, and red-edge bands67,68.

Spectral integration and model validation

The integration of hyperspectral field data and Sentinel-2 imagery enabled the development of a spectral transfer function to estimate SSC using calibrated Spectroradiometer indices. Based on the concept of transitive relations41, this two-tiered approach bridges satellite and field data, enhancing methodological rigor and confirming their compatibility, as supported by previous studies3,21,22. The integration improved spatial and temporal sediment monitoring while maintaining in-situ sensitivity. Validation with 20% of the dataset showed strong agreement between predicted and observed SSC, confirming model reliability and unbiased performance66. Remote sensing models for SSC estimation are commonly validated by comparing satellite-derived values with in-situ measurements, such as those obtained via the gravimetric method. For example, in-situ data validated Landsat 8-derived SSC estimates in Vietnam’s Red River69, and a similar cost-effective approach was used for the Middle Mississippi River64. Foundational studies have also confirmed the reliability of empirical SSC–reflectance relationships validated with ground data20.

Comparative evaluation of spectral integration functions

Statistical comparison of tested indices confirmed the superior performance of the (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red ratio. It achieved the highest R2 (0.809), and the lowest AIC (152.77), BIC (154.86), RMSE (8.58 mg/L), and MAPE (19.41%), with strong linear regression results and consistent k-fold cross-validation performance (average RMSE: 13.21; R2: 0.68). Residual analysis showed low standard deviation (13.78 mg/L) and mean residual (2.53 mg/L), indicating high accuracy and reliability. In contrast, R-NDSSI had a lower slope and R2, and higher intercept and error values, suggesting weaker performance. The model met optimization criteria based on R2, RMSE, MAPE, NSE, and AIC/BIC, consistent with standards in earlier studies16,18,49,72. These findings align with previous results showing high R2 using NSMI in the Arabian Gulf70 and effective SSC estimation in the Barito Delta33. The role of indices like RI and NDWI in aquatic monitoring further supports the need for tailored spectral indices71.

The spatio-temporal maps (Fig. 10) of Suspended Sediment Concentration (SSC) in Mula Dam reservoir, developed using Sentinel-2 imagery and the spectral ratio (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red, revealed distinct seasonal and spatial trends. Higher SSC levels were observed in October, post-monsoon, indicating increased runoff and sediment inflow, while lower values in February reflected reduced sediment transport during the dry season. Spatially, inflow zones and dendritic arms exhibited higher SSC due to turbulence from incoming water.

Effective SSC monitoring through integrated spectroscopy and remote sensing methods provides actionable data for policymakers and environmental managers to implement targeted interventions, contributing to the achievement of SDGs related to water quality, ecosystem sustainability, and climate resilience. These efforts are crucial for protecting freshwater ecosystems, ensuring safe domestic and agricultural water supplies, and advancing the global sustainable development agenda as promoted by the United Nations 2030 Agenda6. To support sustainable reservoir management, the study recommends implementing periodic remote sensing-based monitoring of suspended sediment concentration (SSC) to detect sedimentation trends early. Authorities should promote catchment-level soil conservation practices to reduce sediment inflow and develop sediment management plans, including desiltation schedules. Integration of geospatial tools into decision-making can enhance planning efficiency and long-term water resource sustainability.

Limitations

This study is confined to the Mula Dam reservoir, a single site characterized by consistently low suspended sediment concentration (SSC), which limits the generalizability of the findings to other reservoirs with different sediment dynamics. The developed models exhibited reduced accuracy at SSC levels exceeding 100 mg/L due to spectral reflectance saturation, particularly in the green and red bands, indicating the need for validation in more turbid water bodies. The relatively short data collection period and limited sample size restricted the ability to capture seasonal and interannual variability, which is crucial for understanding dynamic sedimentation processes. Furthermore, the influence of other optically active water constituents—such as chlorophyll-a, coloured dissolved organic matter (CDOM), and turbidity—was not explicitly disentangled from SSC, introducing potential uncertainty in spectral responses. Anthropogenic influences, such as agricultural runoff and land use changes in the catchment, as well as the ecological implications of elevated sediment levels, were beyond the scope of this study and thus not explored in depth. Additionally, while the study referenced alternative SSC estimation techniques, a direct quantitative comparison with in-situ or turbidity-based methods was not performed. Future research should incorporate multi-site and multi-temporal datasets, consider a broader range of water quality parameters, and employ uncertainty quantification methods to enhance model robustness and practical applicability.

Suggestions for future work

Future research should focus on expanding the spatial and temporal scope by including multiple reservoirs across diverse geographical regions and incorporating multi-seasonal or multi-year datasets to capture temporal variability in SSC. Integration of land use dynamics, hydrological modelling, and ecological impact assessments would provide a more holistic understanding of sediment processes. Comparative analysis with additional sediment quantification techniques and refinement of spectral models under varying water quality conditions are also recommended. Such efforts would enhance model generalizability and support the development of effective sediment management strategies.

Conclusions

This study developed and validated a spectral integration framework for estimating Suspended Sediment Concentration (SSC) in the Mula Dam reservoir by linking in-situ Spectroradiometer measurements with Sentinel-2 MSI satellite imagery. Among the evaluated spectral indices and combinations, the ratio (Green × Red Edge 1)/Red demonstrated the highest predictive accuracy, with R2 = 0.809, RMSE = 8.58 mg/L, and MAPE = 19.41%, making it most suitable for low-turbidity water conditions. The spectral integration function was constructed using a two-stage regression approach and rigorously validated through statistical methods including regression analysis, residual diagnostics, and k-fold cross-validation. This robust validation confirmed its effectiveness in estimating SSC across spatial and temporal domains. The research effectively addresses a methodological gap in sediment monitoring by integrating ground-based hyperspectral data with satellite imagery, offering an approach that leverages the strengths of both data sources. Unlike previous studies that relied on either in-situ or satellite-based models in isolation, this study combines them to enhance model reliability and expand temporal applicability, including the potential to estimate past SSC values using archived satellite data. This is particularly valuable for long-term monitoring and sediment trend analysis in inland water bodies. Although the methodology was applied specifically to the Mula Dam reservoir, its design is scalable and transferable to other aquatic systems with appropriate local calibration. The study also acknowledges its limitations, such as the absence of ecological impact assessment and the focus on a single site and season. As a result, it proposes future research directions that include testing the model across multiple reservoirs, incorporating multi-seasonal datasets, and analyzing the influence of land use and ecological variables on sediment dynamics. The findings support global sustainability goals by contributing to SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 15 (Life on Land). The proposed methodology offers a practical tool for sediment management, water quality monitoring, and evidence-based policymaking in support of sustainable watershed and reservoir management.

Data availability

This research article is based on the Doctoral research of corresponding author J. K. Joshi, MPKV, Rahuri. Data supporting this study’s results is provided is the thesis available at ‘Krishikosh’ (An Institutional repository for Indian National Agricultural Research System) in the form of thesis. https://krishikosh.egranth.ac.in/assets/pdfjs/web/viewer.html? file=https%3 A%2 F%2Fkrishikosh.egranth.ac.in%2Fserver%2Fapi%2Fcore%2Fbitstreams%2Ff1b4afd6-643b-4ff3-891e-cc72db002ec9%2Fcontent.

References

Que, L. Transport and deposition of suspended sediment. Water Encyclopedia: Surf. Agricultural Water. 6, 661–665 (2014).

Vercruysse, K., Wei, Y. & Meire, P. Sediment and nutrient budgets for the entire Seine estuary: Considering the sediment bed as an integral part of the budget. Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci. 188, 137–147 (2017).

Lodhi, M. A. K., Simonovic, S. P. & Adamowski, J. Environmental impacts of reservoir sedimentation and sediment management strategies. Environ. Manage. 22(2), 259–269 (1998).

Bejestan, M. S. & Rezania, S. An assessment of suspended sediment distribution in riverine systems. Environ. Geol. 60(6), 1305–1311 (2010).

Vanoni, V. A. Sedimentation Engineering. ASCE Manuals and Reports on Engineering Practice No. 54. (2006).

United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations, 2015). https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

Wang, J. J. & Lu, X. X. Estimation of suspended sediment concentrations using Terra MODIS: an example from the lower Yangtze river, China. Sci. Total Environ. 408, 1131–1138 (2010).

Margareta, N. & Ulf, H. Sediment delivery from forested and Non-Forested catchments in central Sweden during the 20th century. Hydrol. Process. 14(16–17), 3033–3047 (2000).

Schiebe, F. R., Harrington, J. A. Jr. & Ritchie, J. C. Remote sensing of suspended sediments: the lake chicot, Arkansas project. Int. J. Remote Sens. 13(8), 1487–1509 (1992).

Reddy, M. A. Remote sensing for mapping of suspended sediments in Krishna Bay estuary, Andhra pradesh, India. Int. J. Remote Sens. 14(11), 2215–2221 (1993).

Myint, S. W. & Walker, N. D. Quantification of surface suspended sediments along a river-dominated Coast with NOAA AVHRR and SeaWiFS measurements: louisiana, USA. Int. J. Remote Sens. 23(16), 3229–3249 (2002).

Liew, M. W., Veith, T. L. & Bosch, D. D. Design, evaluation, and application of a database for model parameter Estimation. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 39(5), 1209–1223 (2003).

Wang, X., Xu, J., Wang, S. & Zhang, M. Temporal-Spatial variation of suspended sediment in the Yarlung Zangbo river basin based on Landsat data (1987–2016). Remote Sens. 10(2), 311 (2018).

Garg, V., Aggarwal, S. P. & Chauhan, P. Changes in turbidity along Ganga river using Sentinel-2 satellite data during lockdown associated with COVID-19. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk. 11(1), 1175–1195 (2020).

Womber, Z. R. et al. Estimation of Suspended Sediment Concentration from Remote Sensing and In Situ Measurement over Lake Tana, Ethiopia. Advances in Civil Engineering, Volume 2021. (2021).

Zhang, C., Liu, Y., Chen, X. & Gao, Y. Estimation of suspended sediment concentration in the Yangtze main stream based on Sentinel-2 MSI data. Remote Sens. 14, 4446 (2022).

Joshi, J. et al. Estimation of suspended sediment concentration using Sentinel-2 band functions in Mula reservoir, rahuri, india. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 22(2), 375–387 (2023).

Giardino, C., Brescianini, M., Romani, M. & Melchiondo, S. Remote sensing of water quality parameters from sub-tropical lakes using hyperspectral airborne imagery. Remote Sens. 6(11), 9954–9972 (2014).

Marinho, M. M. R. et al. Remote sensing for monitoring the water quality of a tropical reservoir. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 667146 (2021).

Santos, L. N. F., Marinho, M. M. R. & Novo, E. M. L. M. Evaluation of empirical models using reflectance data from Sentinel-2 and MODIS for estimating water turbidity in the Amazon floodplain lakes. Remote Sens. 10(7), 1040 (2018).

Doxaran, D., Froidefond, J. M., Lavender, S. & Castaing, P. Spectral signature of highly turbid waters: application with SPOT data to quantify suspended particulate matter concentrations. Remote Sens. Environ. 81, 149–161 (2002).

Robert, E. et al. Monitoring water turbidity and surface suspended sediment concentration of the Bagre reservoir (Burkina Faso) using MODIS and field reflectance data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 52, 243–251 (2016).

Liu, H. et al. Application of Sentinel 2 MSI images to retrieve suspended particulate matter concentrations in Poyang lake. Remote Sens. 9, 761 (2017).

Kwon, S., Shin, J., Seo, I. W. & Noh, H. Measurement of suspended sediment concentration in open channel flows based on hyperspectral imagery from UAVs. Adv. Water Resour. 159, 104076 (2021).

Kolli, R. & Chinnasamy, P. Estimating turbidity concentrations in the Godavari river using Sentinel-2 red-edge bands. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196(1), 1–17 (2024).

Pitchaikani, J., Natesan, U. & Nallathambi, T. Application of satellite remote sensing in Estimation of suspended sediment concentration in Coastal waters: A case study along Tamil Nadu Coast. India Mar. Georesources Geotechnology. 38(7), 764–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/1064119X.2019.1611421 (2020).

Rajendran, S., Prabhakaran, D. & Marimuthu, R. Estimation of suspended sediment concentration using Sentinel-2 MSI and Landsat-8 OLI data in Arabian Gulf. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 41(3), 334–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/1064119X.2023.2179023 (2023).

Li, Y., Chen, J., Ma, Q. & Zhang, H. K. Evaluation of Sentinel-2A surface reflectance derived using Sen2Cor in North America. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 99, 1–25 (2018).

Gare, A., Wondwosen, S., William, P. & Catherine, O. Spatiotemporal analysis of water quality indicators in small lakes using Sentinel-2 satellite data: lake Bloomington and evergreen lake, central illinois, USA. Environ. Processes. 8, 637–660 (2021).

Pereira, L. F., Cox, L. C., Ghulam, A. & A. L., and Measuring Suspended-Sediment concentration and turbidity in the middle Mississippi and lower Missouri rivers using land sat data. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 54(2), 440–450 (2018).

Sokoletsky, L., Shen, F., Xianping, Y. & Wei, X. Evaluation of empirical and semi analytical spectral reflectance models for surface suspended sediment concentration in the highly variable estuarine and coastal waters of East China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 9(11), 1–11 (2016).

Larson, M. D., Anita, M., Vincent, S., Evans, J. & R. K., and Multi-depth suspended sediment Estimation using high-resolution remote-sensing UAV in Maumee river, Ohio. Int. J. Remote Sens. 39(3), 1–18 (2018).

Hossain, A. A., Jia, Y. & Chao, X. Development of remote sensing based index for estimating/mapping suspended sediment concentration in river and lake environments. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on ECOHYDRAULICS, Paper No. 0435 578–585 (2010).

Arisanty, D. & Saputra, A. N. Remote sensing studies of suspended sediment concentration variation in Barito Delta. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 98 (2017).

Khaire, P. B. Estimation of Suspended Sediment Concentration in Small Reservoir using Drone Survey. An M.Tech Thesis submitted to Department of Soil and Water Conservation Engineering, Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth Rahuri 28 (2019).

Sutari, A., Putra, D. & Hasanah, U. Estimating suspended sediment concentration in waters using Landsat 8 imagery. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 599, 012016. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/599/1/012016

Kazemzadeh, M. B., Ayyoubzadeh, S. A. & Moridnezhad, A. Remote sensing of Temporal and Spatial variations of suspended sediment concentration in Bahmanshir estuary, Iran. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 6(8), 1–10 (2013).

Zhan, C. et al. Remote sensing retrieval of surface suspended sediment concentration in the yellow river estuary. Chin. Geogra. Sci. 27, 934–947 (2017).

Essam, S., Smith, M. & Ali, R. Evaluating the effectiveness of training-validation splits in machine learning-based land cover classification. Remote Sens. Applications: Soc. Environ. 25, 100679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsase.2021.100679 (2022).

Fang, K., Yang, L. & Liu, X. Monitoring sediment dynamics in inland reservoirs using satellite remote sensing and hydrological modeling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Dis. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-2024-123 (2024).

Arstila, V. Why the transitivity of perceptual simultaneity should be taken seriously. Frontiers Integr. Neuroscience, 6(3). (2012).

ASCE. Criteria for evaluation of watershed models. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 119(3), 429–442 (1993).

Legates, D. R. & McCabe, G. J. Evaluating the use of ‘goodness-of-fit’ measures in hydrologic and hydro Climatic model validation. Water Resour. Res. 35(1), 233–241 (1999).

Pitchaikani, J. S., Ramakrishnan, R., Bhaskaran, P. K., Ilangovan, D. & Rajawat, A. S. Development of regional algorithm to estimate suspended sediment concentration (SSC) based on the remotely sensed reflectance and field observations for the Hooghly estuary and West Bengal coastal waters. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 47(1), 177–183 (2019).

Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., Neter, J. & Li, W. Applied Linear Statistical Models 5th edn (McGraw-Hill Education, 2005).

Chunale, G. L. Validity testing of SCS Curve Number technique for sub-humid region of Maharashtra (Unpublished M.Tech thesis). Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, Rahuri. (1999).

Singh, R., Mujumdar, P. & Kumar, D. N. Regional flood frequency analysis using L-moments. J. Hydrol. 285(1–4), 96–113 (2004).

Khair, A. W., Salim, N., Rahman, N. S. A., Alias, N. A. & Shabri, A. Application of fuzzy time series and neural network model for time series forecasting. Applied Mathematical Sciences, 11(43):2141–2156. (2017).

Nash, J. E. & Sutcliffe, J. V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I - A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 10(3), 282–290 (1970).

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. An Introduction To Statistical Learning: with Applications in R 1st edn (Springer, 2013).

Montgomery, D. C., Peck, E. A. & Vining, G. G. Introduction To Linear Regression Analysis 5th edn (Wiley, 2012).

Sravanthi, N. et al. An algorithm for estimating suspended sediment concentrations in the coastal waters of India using remotely sensed reflectance and its application to coastal environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. 7(4), 841–850 (2013).

Doxaran, D., Cherukuru, R. C. N. & Lavender, S. J. Use of reflectance band ratios to estimate suspended and dissolved matter concentrations in estuarine waters. Int. J. Remote Sens. 26(8), 1763–1769 (2005).

Wright, D. Sentinel-2 as a tool for quantifying suspended particulate matter in the Tamar estuary, UK. Plymouth Student Sci. 11(2), 3–33 (2018).

Gholizadeh, A., Keesstra, S., Ghodousi, J. & Ahmadi, H. Water quality and quantity monitoring in large river basins with limited data availability: review of current and future satellite and UAV-Based sensors for monitoring nutrients and sediments. International J. Appl. Earth Observation Geoinformation. 47, 48–64 (2016).

Mishra, S. & Mishra, D. R. Normalized difference chlorophyll index: A novel model for remote Estimation of chlorophyll-a concentration in turbid productive waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 117, 394–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2011.10.016 (2012).

Li, Y., Duan, H. & Ma, R. Influence of CDOM and chlorophyll-a on the accuracy of TSM remote sensing algorithms in eutrophic lakes. Remote Sens. 12(14), 2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12142224 (2020).

Salami, M. R., Fataei, E., Nasehi, F., Khanizadeh, B. & Saadati, H. Water quality monitoring using modeling of suspended sediment Estimation (A case study: sefidroud river in Northern Iran). Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 4(17), 101–111 (2024).

Mahdawi, Q., Shanehsazzadeh, A. & Fatemi, S. B. Application of Sentinel-2 multispectral images for estimating the suspended sediment source and concentration in flood events: Case study of Laghman Basin, Afghanistan. University of Isfahan, Iran. [Preprint]. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5213050 (2025).

Govender, M., Chetty, K. & Bulcock, H. A review of hyperspectral remote sensing and its application in vegetation and water resource studies. Water SA. 33(2), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.4314/wsa.v33i2.49048 (2007).

Manolakis, D., Lockwood, R. & Cooley, T. Hyperspectral Imaging Remote Sensing: Physics, Sensors, and Algorithms (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Thenkabail, P. S., Lyon, J. G. & Huete, A. (eds) Hyperspectral Remote Sensing of Vegetation (CRC, 2012).

Dekker, A. G., Vos, R. J. & Peters, S. W. M. Analytical algorithms for lake water TSM Estimation validated with independent data. Remote Sens. Environ. 82(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(02)00025-9 (2002).

Martinez, J. M. & Cox, M. Remote sensing-based sediment monitoring in the middle Mississippi river: A cost-effective approach. J. Hydrol. 615, 128689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128689 (2023).

Nechad, B., Ruddick, K. & Neukermans, G. Calibration and validation of a generic multisensor algorithm for mapping of turbidity in coastal waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 114(4), 854–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2009.11.022 (2010).

Han, L. & Jordan, K. J. Estimating suspended sediment concentration in estuarine and coastal waters using hyperspectral and multispectral remote sensing. Int. J. Remote Sens. 37(3), 566–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2015.1134954 (2016).

Knaeps, E., Ruddick, K. & Park, Y. Using Sentinel-2 data for mapping suspended particulate matter concentrations in turbid waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 166, 22–32 (2015).

Feng, Y., Jiang, L. & Li, X. Estimation of suspended sediment concentration in coastal waters using a quadratic regression model based on Sentinel-2 data. Remote Sens. 12(6), 961 (2020).

Pham, Q. V. et al. Using Landsat-8 images for quantifying suspended sediment concentration in red river (Northern Vietnam). Remote Sens. 10(11), 1841. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10111841 (2018).

Sankaran, S., Al-Barakati, A. & Greminger, M. A multitemporal analysis of suspended sediment using Sentinel-2 data and NSMI in the Arabian Gulf. Remote Sens. 15(3), 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15030621 (2023).

Gover, M., Chetty, K. & Bulcock, H. A review of hyperspectral remote sensing and its application in vegetation and water resource studies. Water SA. 33(2), 145–151 (2007).

Motulsky, H. J. & Ransnas, L. A. Fitting curves to data using nonlinear regression: A practical and nonmathematical review. FASEB J. 1(5), 365–374 (1987).

Acknowledgements

We express sincere gratitude to the Department of Soil and Water Conservation, Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, Rahuri, for their technical assistance, and to the CAAST-CSAWM Project for financial support to conduct the experimental work. Their contributions were vital to the completion of this research.

Funding

The CAAST-CSAWM Project, MPKV Rahuri, provided financial support to conduct the experimental work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. K. Joshi, A. A. Atre, S. D. Gorantiwar, and M. G. Shinde contributed to the study’s concept and design. J. K. Joshi conducted the literature research. Methodology development was done by (A) A. Atre , S. (B) Nandgude and S. D. Gorantiwar, while J. K. Joshi and M. R. Patil performed the statistical analysis. The manuscript was prepared by J. K. Joshi, and S. B. Nandgude and A. G. Durgude were responsible for manuscript editing. All authors have reviewed the manuscript and guarantee the integrity of the entire study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Joshi, J.K., Atre, A.A., Nandgude, S.B. et al. Empirical modelling of suspended sediments using spectral data from spectroradiometer and sentinel-2 in Mula Dam Reservoir, Maharashtra, India. Sci Rep 15, 34205 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15719-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15719-w