Abstract

In this research, the Fokas method is adopted to examine the coupled Gerdjikov–Ivanov equation within the half line interval \((-\infty ,0]\). Meanwhile, the Riemann–Hilbert technique is engaged to work out the potential function associated with the equation. We initially partition the matrix into segments and identify the jump matrix linking each segment based on the positive feature of the segment. The jump matrix comes from the spectral matrix, the latter of which is decided by the initial value and the boundary value. The research indicates that these spectral functions display correlativity instead of being independently separated, and they abide by a global connection while being associated via a compatibility condition. Then, we explore the coupled Gerdjikov–Ivanov equation under the zero boundary condition at infinity. The initial value problem related to the equation is capable of being converted into a Riemann–Hilbert problem on the strength of the analytic and symmetric properties of the eigenfunctions. Ultimately, through the settlement of both the regular and non-regular Riemann–Hilbert problems, a general pattern of N-soliton solutions with respect to the coupled Gerdjikov–Ivanov equation is put forward.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The inverse scattering method1 is a mathematical tool employed in the examination of integrable partial differential equations, particularly addressing the initial boundary value problem associated with the Korteweg–de Vries (KdV) equation , which was introduced by Gautner2 in 1967. The core principle of the inverse scattering method lies in its ability to simplify a complex partial differential equation by transforming it into either a collection of ordinary differential equations or a single one. This is achieved through the application of an appropriate integral or differential transformation, which converts the initial equation into an equivalent one within a different coordinate system or involving a new unknown function. However, it should be acknowledged that while this approach demonstrates remarkable efficacy when applied to integrable equations, its suitability for addressing specific nonlinear equations3,4 with diverse initial and boundary conditions may be limited. In practice, the ascertainment of a solution to a nonlinear equation is predominantly affected by initial boundary value conditions instead of being exclusively dependent on initial value conditions. This limitation suggests that the inverse scattering method may not be suitable for addressing such scenarios, thus requiring a fresh approach to examine initial boundary value problems. The Fokas method, proposed by Fokas in 19975, utilizes complex analysis and spectral theory to convert an initial-boundary value problem into a Riemann–Hilbert problem within the complex plane of spectral parameters. This approach effectively incorporates boundary data into the solution process, allowing for the effective handling of problems with non-standard or intricate boundary conditions. The Fokas method is particularly adept at dealing with interconnected boundary values encountered during nonlinear PDE analysis. By adapting the Riemann-Hilbert problem to accommodate diverse boundary conditions, this approach ensures the precision of the solutions. Nonetheless, in the examination of initial boundary value problems within complex planar frameworks, we are likely to encounter mutually dependent boundaries, where any alteration would substantially impact the entire solution set. Consequently, the formulation of a pertinent Riemann-Hilbert problem involves exploring diverse initial boundary value scenarios and then choosing the most appropriate one. In the last twenty years, thorough investigations have been conducted by Fokas6,7, Deift8, Its9, Monvel10,11,12, Lenells13,14,15,16,17, Fan and Xu18,19,20,21,22,23, Zhu24, Zhang and Hu25,26,27,28,29,30, Wu and Huang31,32 et al to enhance and expand this approach, demonstrating its adaptability and effectiveness in addressing various challenges within mathematical physics and engineering.

The Coupled Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation is of great significance in examining integrable systems and nonlinear wave phenomena. It was initially proposed by V. S. Gerdjikov and M. I. Ivanov in 1983, expanding upon its predecessor to allow for interactions among multiple wave fields. This study primarily focuses on the coupled GI equation33,

where q and r function as complex-valued functions. Supposing \(r= -q^{*}\), Eq. (1)and Eq. (2) can be read as

where \(q^{*}\) denotes the complex conjugate of q. where and function as complex-valued functions It has been demonstrated that the integrability of both the GI equation Eq. (3) and the coupled GI equation Eqs. (1) and (2) can be established in the Liouville sense through utilization of the trace identity. Extensive discussions have taken place regarding the GI equation in the past few years. In contrast, limited research has been conducted on the coupled GI equation34,35,36,37, encompassing Dbar dressing method, Darboux transform, Rogue wave solutions. However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no utilization of the Fokas method in examining the coupled GI equation. Therefore, our intention is to employ the Fokas method in examining the initial boundary value problems of the coupled GI equation. The region of interest for our analysis is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The boundaries \(\{-\infty <z\le 0, y=L\}\), \(\{z=0, 0 \le y \le L\}\) and \(\{-\infty <z\le 0, y=0\}\) are referred to boundaries (I), (II), and (III) in sequence, as shown in Figure 1. Postulating the presence of solutions q(z, y) and r(z, y) with respect to the Coupled Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation, we then commence establishing the initial values

the Dirichlet boundary values regarded as

as well as the Neumann boundary values like

The interaction of multiple wave fields in nonlinear media can be effectively modeled by the Coupled Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation, making it highly relevant in various physical applications. In the field of nonlinear optics38,39,40,41, the coupled GI equation is of vital importance in explaining the propagation of polarized light within birefringent optical fibers. Within these fibers, the interaction between different polarization modes can give rise to complex wave structures such as solitons and rogue waves. The utilization of the coupled GI equation aids in comprehending and predicting these phenomena, which are of significant importance for optimizing and designing fiber optic communication systems. The application of the coupled GI equation is applicable in the field of fluid dynamics42, particularly when studying surface waves on liquids. It facilitates the depiction of the interaction between different wave modes occurring on the liquid’s surface, thereby improving understanding regarding wave breaking, turbulence, and other nonlinear wave phenomena. In the field of plasma physics43,44, the coupled GI equation is utilized to elucidate the transmission of nonlinear waves in magnetized plasmas. The interconnection among various wave modes within the plasma can lead to intricate phenomena that are crucial for comprehending plasma confinement and stability in fusion devices.

In the present research, the Fokas method is employed to augment Lenells’ examination of the initial boundary value matter within the bounded interval \((-\infty ,0]\). The layout of this research is delineated as presented beneath. In “Spectral examination”, we present Lax pairs associated with the equation. For the purpose of guaranteeing that the integration is not reliant on the integral path, we opt for three distinct integral paths. Subsequently, we divide the equation into different sections on the complex plane. For each section, we ascertain its sign and calculate the corresponding jump matrix. By utilizing these jump matrices, we establish the global relationship across the complex plane. In “Analysis of spectral functions and Riemann–Hilbert problem”, we investigate the spectral function \(\{f(\gamma ),g(\gamma )\}\) and \(\{F(\gamma ),G(\gamma )\}\) connected with the initial (4), (5) and boundary (6), (7) values of the equation. An analysis is conducted on the characteristics of the spectral function, including its residue conditions. Subsequently, we examine the transformation in the area by setting \(z=0\) and \(y=0\), and calculate the jump matrix for both scenarios. In “Riemann–Hilbert problem”, the correlation between the solutions of the Coupled Gerdjikov–Ivanov equation and the Riemann–Hilbert problem has been discussed by us. In “The solution of the Riemann–Hilbert problem”, the formal resolutions relevant to the regular and irregular Riemann-Hilbert problems are deduced, and the N-soliton solution of the equation is acquired. In “Conclusion”, provide a summary of the research presented in this research and highlight potential areas for future investigation that interest us.

Spectral examination

The expressions and notations employed within this research

-

The Pauli matrix is marked as \(\theta _{3}\), \(\theta _{3}=\left( \begin{array}{cc}1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \\ \end{array}\right)\), \(\theta _{-}=\left( \begin{array}{cc}0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \\ \end{array}\right)\), and \(\theta _{+}=\left( \begin{array}{cc}0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 \\ \end{array}\right)\).

-

Matrices F and G are matrices of type \(2\times 2\) and \([F,G]=FG-GF\);

-

The commutator of the matrix is denoted as \({\hat{\theta }}_{3}\), and the research presents the calculation \(e^{{\hat{\theta }}_{3}}\) as \(e^{{\hat{\theta }}_{3}}F=e^{\theta _{3}}Fe^{-\theta _{3}}\);

-

The representation of the function’s complex conjugation is denoted by an overline, like \(\overline{f(\bullet )}\).

Lax pair transformation equation

The Lax pairs associated with the coupled GI equation can be found in Luo32. The coupled GI equations ought to meet the stipulations of the Lax pair for any \(\gamma \in {\mathbb {C}}\) in the following manner :

where

Assuming

The associated Lax pair can be procured by us

where

The Lax pair is capable of being constituted as complete differentials denoted in the ensuing mode

where

In the pursuit of handling the inverse spectral problem by employing the Riemann-Hilbert technique, our goal lies in determining a solution to the spectral problem that asymptotically tends to an identity matrix as \(\gamma \rightarrow \infty\). To achieve this desired asymptotic behavior, we will employ Lenells’ method13,14,15,16,17, as the current outcome does not exhibit this characteristic.

Analysis of the equation in asymptotic terms

Suppose that the given expression represents a solution to Eq. (18)

where \(\upsilon _0,\upsilon _1,\upsilon _2,\upsilon _3\) are independent from \(\gamma\). Through integrating the aforementioned expansion into the original expression in Eq. (13), we can achieve

\(\upsilon _0\) is denoted through the employment of a matrix whose elements on the diagonal are present and let \(\upsilon _0=\left( \begin{array}{cc} \upsilon _0^{11} & 0 \\ 0 & \upsilon _0^{22} \\ \end{array} \right)\). The matrix is derived by employing \(O(\gamma )\),

where \(\upsilon _1^{(o)}\) serves as the off-diagonal segment of \(\upsilon _1\). In the process of employing O(1), we attain

The second equation in (13) is substituted with the previously mentioned expansion, leading to the result being reached by us

The relationship can be derived with \(O(\gamma ^1)\)

Through the application of Eq. (20) and the utilization of a computational complexity rated at O(1) , the sought-after result can be ascertained

Using (19) and (21), we are capable of providing a definition for them in the following manner

where \(\Delta (z,y)=\Delta _1(z,y)dz+\Delta _2(z,y) dy\), \(\Delta _1(z,y)=-qr\), \(\Delta _2(z,y)=0\), and \((z_0,y_0)\in \upsilon\), simultaneity, for the sake of simplifying calculations, we represent \((z_0,y_0)\) as (0, 0) for convenience.

As the selected path does not affect the value of integral (20). A new function \(\eta (z,y;\gamma )\) can be introduced through the ensuing approach.

After performing basic calculations, the Lax pair of (18) is identical to

where

By utilizing the definitions of \(V(z,y;\gamma )\) and \(\Delta\), it becomes feasible to deduce both \(H_1\) and \(H_2\).

The expression of \(\eta (z,y;\gamma )\) in (24) can be obtained as follows

where \(-\infty <z\le 0,\,\,\,\,\,\, 0\le y\le L,\,\,\,\,\gamma \in {\mathbb {C}}.\)

Characteristic Functions and Their Pertinent Connections

We propose the existence of q(z, y), r(z, y) and assume that \(\upsilon =\{-\infty <z\le 0, 0\le y\le L\}\) has sufficient smoothness. Based on Eq. (24), we present three eigenfunctions \(\eta _k(z,y,\gamma )\) as follows:

The integral symbolizes a continuous curve that establishes a connection between the points \((z_k,y_k)\) and (z, y), where \((z_1, y_1)=(0,0), (z_2, y_2) = (-\infty , y), (z_3, y_3) = (0, L)\). Please refer to Figure 2 for a visual representation.

The functions \(\eta _1\), \(\eta _2\), and \(\eta _3\) are defined within a specific region of the complex \(\gamma\)-plane. To ensure that the calculation of Eq. (19) keeps unaltered irrespective of the selected route, we designate a singular integral trajectory that is aligned with the coordinate axis in accordance with what Fig. 3 presents.

These routes indicate subsequent inequalities

By utilizing the pathway diagram and the above analysis, we can derive

Assuming \(\eta _k(z,y;\gamma )=I+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma })\) (for \(k=1,2,3\)) and taking into account the \(\gamma\)-dependency of \(H_{1}(z, y; \gamma )\) and \(H_{2}(z, y; \gamma )\). It is based on the aforementioned inequality that we are able to establish that they are limited. This authorizes the partitioning of the complex \(\gamma\)-plane into eight regions

The second column represents the reciprocal of the first column in Eq. (24). Therefore, the values in the second column exhibit an inverse relationship to those in the first column, with the former being bounded by

Subsequently, we acquire

The \(\eta _{k}\) act as the requisite eigenfunctions essential for the proper formulation of a Riemann-Hilbert problem within the complex \(\gamma\)-plane. Let \(\upsilon _i(i=1,2,3,4)\) in the complex \(\gamma\)-plane be given by \(\upsilon _i=\varepsilon _i\cup (-\varepsilon _i)\), where \(\varepsilon _i=\{\gamma \in {\mathbb {C}}|k\pi +\frac{i-1}{4}\pi<\textrm{Arg} \gamma <k\pi +\frac{i}{4}\pi \}, -\varepsilon _i=\{-\gamma \in {\mathbb {C}}|\gamma \in {\varepsilon _i}\}\), \(i=1,2,3,4,\,\,\ k=0,\pm 1,\pm 2,\cdots\), ( refer to Figure 4).

However, the domains in which \(\eta _1(0,y;\gamma )\), \(\eta _3(0,y;\gamma )\), \(\eta _1(z,0;\gamma )\), \(\eta _3(z,L;\gamma )\), \(\eta _1(0,L;\gamma )\), \(\eta _3(0,0;\gamma )\) are bounded extend beyond their current boundaries

The \(\eta _k\) holds that \(\eta _k(z,y;\gamma )=I+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma })\) as \(\gamma \rightarrow \infty\), \(k=1,2,3\).

Spectral functions and their underlying propositional structures

In the pursuit of resolving a Riemann-Hilbert problem, it is highly crucial to calculate the discontinuities that manifest at the boundaries of the regions denoted as \(\upsilon _i\) \((i=1,2,3,4)\). The results suggest that the correlation jump matrix can be defined using two spectral functions, denoted as \(a(\gamma )\) and \(A(\gamma )\). These functions are represented by \(2\times 2\) matrices. Their configuration is presented in the following manner.

Computing Eq. (30) at the point \((z,y)=(0,0)\) yields

Simultaneously, evaluate Eq. (31) when \((z,y)=(0,0)\).

When Eq. (31) is evaluated at \((z,y)=(0,L)\), it can be inferred

establishing the global relation.

Therefore, we assume that when \(z = 0\), we can determine the function \(\eta _1(z, 0,\gamma )\) and derive the function \(a(\gamma )\). Similarly, assuming that when \(y = L\), we can determine the function \(\eta _2(0,y,\gamma )\) and derive the function \(A(\gamma )\). Finally, by solving for \(a(\gamma )\) and \(A(\gamma )\) using these functions.

By evaluating the equations \(H_1\) at \(y=0\) and \(H_2\) at \(z=0\), and introducing \(q_0(z)=q(z,0)\), \(r_0(z)=r(z,0)\), \(g_0(y)=q(0,y)\), \(h_0(y)=r(0,y)\), \(g_1(y)=q_z(0,y)\) and \(h_1(y)=r_z(0,y)\); we can utilize the provided data to depict the initial and boundary values pertaining to the function q(z, y).

\(H_2^{11}=-i\gamma ^2h_0k_0+\frac{i}{4}h_0^{2}k_0^{2}+\frac{1}{2}(k_1h_0-k_0h_1)\),

\(H_2^{12}=(2\gamma ^3k_0+i\gamma k_1)e^{-2i\int _{0}^{y}\Delta _2(0,\tau )d\tau }\),

\(H_2^{21}=(2\gamma ^3h_0-i\gamma h_1)e^{2i\int _{0}^{y}\Delta _2(0,\tau )d\tau }\),

\(H_2^{22}=i\gamma ^2h_0k_0-\frac{i}{4}ih_0^{2}k_0^{2}-\frac{1}{2}(k_1h_0-k_0h_1)\),

and \(\Delta _2(0,\tau )=0\).

The calculations of \(H_1(z,0;\gamma )\) and \(H_2(0,y;\gamma )\) rely exclusively on the functions \(q_{0}(z)\), \(r_{0}(z)\), \(k_{0}(y)\), \(k_{1}(y)\), \(h_{0}(y)\), \(h_{1}(y)\). Subsequently, the initial data establish the integral (26) that dictates \(a(\gamma )\). In parallel, the boundary data are employed to delineate \(g_0(y)\), \(g_1(y)\), \(h_0(y)\), and \(h_1(y)\) via the integral (26), which governs \(A(\eta )\). The succeeding pronouncement sketches the analytic peculiarities of the matrices \(\eta _k(z,y;\gamma )\) \((j=1,2,3)\), which are acquired through Eq. (26).

Proposition 1

The symmetric relation is satisfied by the function \(\eta (z, y, \gamma )\), which is labeled as \(\eta _k(z, y, \gamma )\) for \(k \in \{1, 2, 3\}\).

as well as

Proof

There exists, in12, a confirmation of symmetry. \(\square\)

Proposition 2

The matrix function \(\eta _k(z,y;\gamma )\) exhibits the subsequent analytical characteristics. Setting

-

\(\eta _k(z,y;\gamma )=(\eta _k^{(1)}(z,y;\gamma ),\eta _k^{(2)}(z,y;\gamma ))=\left( \begin{array}{cc} \eta _k^{11} & \eta _k^{12} \\ \eta _k^{21} & \eta _k^{22} \\ \end{array} \right) ,k=1,2,3;\)

-

\(det\eta _k(z,y;\gamma )=1, k=1,2,3\);

-

The function \(\eta _1^{(1)}(z, y; \gamma )\) manifests evident analytic properties. Moreover, for \(\gamma\) belonging to the intersection of the set \(\{\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2 \le 0\}\) and the set \(\{\textrm{Im}\gamma ^4 \ge 0\}\), it holds that \(\lim \limits _ {\gamma \rightarrow \infty }\eta _1^{(1)}(z,y;\gamma )=(1,0)^T\).

-

The function \(\eta _1^{(2)}(z,y;\gamma )\) manifests evident analytic properties. Moreover, for \(\gamma\) belonging to the intersection of the set \(\{\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2 \ge 0\}\) and the set \(\{\textrm{Im}\gamma ^4 \le 0\}\), it holds that \(\lim \limits _ {\gamma \rightarrow \infty }\eta _1^{(2)}(z,y;\gamma )=(0,1)^T\).

-

The function \(\eta _2^{(1)}(z,y;\gamma )\) manifests evident analytic properties. Moreover, for \(\gamma\) belonging to the intersection of the set \(\{\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2 \ge 0\}\), it holds that \(\lim \limits _ {\gamma \rightarrow \infty }\eta _2^{(1)}(z,y;\gamma )=(1,0)^T\).

-

The function \(\eta _2^{(2)}(z,y;\gamma )\) manifests evident analytic properties. Moreover, for \(\gamma\) belonging to the intersection of the set \(\{\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2 \le 0\}\), it holds that \(\lim \limits _ {\gamma \rightarrow \infty }\eta _2^{(2)}(z,y;\gamma )=(0,1)^T\).

-

The function \(\eta _3^{(1)}(z,y;\gamma )\) manifests evident analytic properties. Moreover, for \(\gamma\) belonging to the intersection of the set \(\{\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2 \le 0\}\) and the set \(\{\textrm{Im}\gamma ^4 \le 0\}\), it holds that \(\lim \limits _ {\gamma \rightarrow \infty }\eta _3^{(1)}(z,y;\gamma )=(1,0)^T\).

-

The function \(\eta _3^{(2)}(z,y;\gamma )\) manifests evident analytic properties. Moreover, for \(\gamma\) belonging to the intersection of the set \(\{\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2 \ge 0\}\) and the set \(\{\textrm{Im}\gamma ^4 \ge 0\}\), it holds that \(\lim \limits _ {\gamma \rightarrow \infty }\eta _3^{(2)}(z,y;\gamma )=(0,1)^T\).

Proof

Based on the fact that \(\eta (z,y;\gamma ) = 1 + {\mathcal {O}}\left( \frac{1}{\gamma }\right)\) as \(\gamma \rightarrow \infty\), it can be inferred that \(\eta (z,y;\gamma )\) converges to the identity matrix as \(\gamma \rightarrow \infty\). Consequently, the first row of the matrix converges to (1, 0) and the second row converges to (0, 1). \(\square\)

Proposition 3

Matrix functions \(a(\gamma )\) and \(A(\gamma )\) are capable of being constructed by us

Based on formulas (30)–(31), it can be inferred that the functions \(f(\gamma )\) and \(F(\gamma )\) exhibit even symmetry, while the functions \(g(\gamma )\) and \(G(\gamma )\) display odd symmetry,

The definitions of \(\eta _1\) and \(\eta _3\) have implications for both \(a(\gamma )\) and \(A(\gamma )\)

By utilizing Eqs. (30), (31), and (35), we can derive

-

(1)

\(\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{cc} \left( \begin{array}{c} \overline{f({\bar{\gamma }})} \\ \overline{g({\bar{\gamma }})} \\ \end{array} \right) =\eta _2^{(1)}(0,0;\gamma )=\left( \begin{array}{c} \eta _2^{11}(0,0;\gamma ) \\ \eta _2^{21}(0,0;\gamma ) \\ \end{array} \right) \\ \left( \begin{array}{c} g(\gamma ) \\ f(\gamma ) \\ \end{array} \right) =\eta _2^{(2)}(0,0;\gamma )=\left( \begin{array}{c} \eta _2^{12}(0,0;\gamma ) \\ \eta _2^{22}(0,0;\gamma ) \\ \end{array} \right) \\ \left( \begin{array}{c} F(\gamma ) \\ -\overline{G({\bar{\gamma }})}e^{4i\gamma ^4L} \\ \end{array} \right) =\eta _2^{(1)}(0,L;\gamma )=\left( \begin{array}{c} \eta _2^{11}(0,L;\gamma ) \\ \eta _2^{21}(0,L;\gamma ) \\ \end{array} \right) \\ \left( \begin{array}{c} -e^{-4i\gamma ^4L}G(\gamma ) \\ \overline{F({\bar{\gamma }})} \\ \end{array} \right) =\eta _2^{(2)}(0,L;\gamma )=\left( \begin{array}{c} \eta _2^{12}(0,L;\gamma ) \\ \eta _2^{22}(0,L;\gamma ) \\ \end{array} \right) . \end{array} \end{aligned}\)

-

(2)

\(\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{cc} \partial _z\eta _2^{(2)}(z,0;\gamma )+2i\gamma ^2\theta \eta _2^{(2)}(z,0;\gamma )=H_1(z,0;\gamma )\eta _2^{(2)}(z,0;\gamma ),\,\,\,\\ \gamma \in \upsilon _3\bigcup \upsilon _4,-\infty<z<0.\\ \partial _y\eta _2^{(2)}(0,y;\gamma )+4i\gamma ^4\theta \eta _2^{(2)}(0,y;\gamma )=H_2(0,y;\gamma )\eta _2^{(2)}(z,0;\gamma ),\,\,\,\\ \gamma \in \upsilon _2\bigcup \upsilon _4,0<y<L. \end{array} \end{aligned}\) where \(\theta =\left( \begin{array}{cc} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \\ \end{array} \right)\).

-

(3)

\(\begin{aligned} \textrm{det} a(\gamma )=\textrm{det} A(\gamma )=1 \end{aligned}\)

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{cc} f(-\gamma )=f(\gamma ),\,\,\,g(-\gamma )=-g(\gamma ),\\ F(-\gamma )=F(\gamma ),\,\,\,G(-\gamma )=-G(\gamma ),\\ f(\gamma )\overline{f({\bar{\gamma }})}-g(\gamma )\overline{g({\bar{\gamma }})}=1,\\ F(\gamma )\overline{F({\bar{\gamma }})}-G(\gamma )\overline{G({\bar{\gamma }})}=1,\\ f(\gamma )=1+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }),\,\,\,g(\gamma )={\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }),\,\,\,\gamma \rightarrow \infty , Im\gamma ^2\ge 0,\\ F(\gamma )=1+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }),\,\,\,G(\gamma )={\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }),\,\,\,\gamma \rightarrow \infty , Im\gamma ^4\ge 0. \end{array} \end{aligned}$$

Proof

Due to the analytic and bounded characteristics of \(\eta _1(z, 0; \gamma )\) and \(\eta _2(0, y; \gamma )\), and the demand for a unit determinant and the asymptotic behavior of these eigenfunctions at \(\gamma\), all these properties can be derived. \(\square\)

Jump matrix

We establish that the spectral functions reveal a global connection rather than being non-independent of each other. The Eqs. (30) and (31) are to be formulated in terms of jump matrices.

Following notation is introduced

\(\Omega (z,y;\gamma )\) is defined in a manner that can be delineated as follows

These definitions show that

Theorem 1

Assume that \(q(z,y;\gamma )\) and \(r(z,y;\gamma )\) are functions exhibiting smooth characteristics and \(\Omega (z,y;\gamma )\) is given by the formula (40), which adheres to the jump environment.

where

and

Proof

We construct (30), (31), and (35) in the following manner with \(\Lambda (\gamma )=\gamma ^2z+2\gamma ^4y\) for the jump condition.

The jump matrices \(S_i(z,y;\gamma )(i=1,2,3,4)\) could be inferred by utilizing Eqs. (37), (38), and (39) in combination with the interdependence among various boundaries.

\(\square\)

Proof

The proof is finished with this. \(\square\)

Assumption 1

Functions \(\varphi (\eta )\) and \(s(\eta )\) are hypothesized in the manner below

-

\(f(\gamma )\) contains \(2\Gamma\) simple zeros \(\{\varkappa _j\}_{j=1}^{2\Gamma }\), \(2\Gamma =2\Gamma _1+2\Gamma _2\). We assume that \(\varkappa _j\)( \(j=1,2,\cdots ,2\Gamma _1\)) pertains to \(\upsilon _1\bigcup \upsilon _2\), and \({\bar{\varkappa }}_j\)(\(j=2\Gamma _1+1,2\Gamma _1+2,\cdots ,2\Gamma\)) pertains to \(\upsilon _3\bigcup \upsilon _4\).

-

\(\rho (\gamma )\) contains \(2\iota\) simple zeros \(\{\xi _j\}_{j=1}^{2\iota }\)(\(2\iota =2\iota _1+2\iota _2\)). We assume that \(\xi _j\)(\(j=1,2,\cdots ,2\iota _1\)) pertains to \(\upsilon _1\bigcup \upsilon _2\), and \({\bar{\xi }}_j\)(\(j=2\iota _1+1,2\iota _1+2,\cdots ,2\iota\)) pertains to \(\upsilon _3\bigcup \upsilon _4\).

-

There are distinctions between simple zeros of \(f(\gamma )\) and \(\rho (\gamma )\).

In the context of addressing the Riemann-Hilbert problem, \([\Omega (z,y;\gamma )]_1\) is employed for the first column, and \([\Omega (z,y;\gamma )]_2\) for the second column. These solutions serve as the foundation for the succeeding assumptions. At the point relevant to \(\Omega (z,y;\gamma )\), Eqs. (30), (31) and (35) are employed to compute the residue. We are able to write \({\dot{f}}(\gamma )=\frac{df}{d\gamma }\) and \({\dot{\rho }}(\eta )=\frac{d\rho }{d\gamma }\).

Proposition 4

-

(1)

Res \(\{[\Omega (z,y;\gamma )]_{1}, \xi _j \}\)=\(\frac{e^{2i\theta (\xi _j)}}{{\dot{\rho }}(\xi _j)\kappa (\xi _j)}[\Omega (z,y;\xi _j)]_{2}\), \(j=1,2,\cdots ,2\iota _1\).

-

(2)

Res \(\{[\Omega (z,y;\gamma )]_{2}, {\bar{\xi }}_j \}\)=\(\frac{e^{-2i\theta ({\bar{\xi }}_j)}}{\overline{{\dot{\rho }}({\bar{\xi }}_j)}\overline{\kappa (\bar{\xi _j})}}[\Omega (z,y;\bar{\xi _i})]_{1}\), \(j=2\iota _1+1,2\iota _1+2,\cdots ,2\iota\).

-

(3)

Res \(\{[\Omega (z,y;\gamma )]_{1}, \varkappa _j \}\)=\(\frac{e^{2i\theta ({\varkappa _j})}\overline{g({\bar{\varkappa }}_j)}}{{{\dot{f}}({\varkappa }_j)}}[\Omega (z,y;{\varkappa }_j)]_{2}\), \(j=1,2,\cdots ,2\Gamma _1\).

-

(4)

Res \(\{[\Omega (z,y;\gamma )]_{2}, {\bar{\varkappa }}_j \}\)=\(\frac{e^{-2i\theta (\bar{\varkappa _j)}}g(\varkappa _j)}{\overline{{\dot{f}}({\bar{\varkappa }}_j)}}[\Omega (z,y;\bar{\varkappa _j})]_{1}\), \(j=2\Gamma _1+1,2\Gamma _1+2,\cdots ,2\Gamma\).

Proof

Think about \((\frac{\eta _2^{\upsilon _1\cup \upsilon _2}(z,y;\gamma )}{\rho (\gamma )}, \eta _3^{\upsilon _1}(z,y;\gamma ))\). For \(\rho (\gamma )\), its zeros \({\xi }_j\) (\(j=1,2,\cdots ,2\iota _1\)) serve as the poles of \(\frac{\eta _2^{\upsilon _1\cup \upsilon _2}(z,y;\gamma )}{\rho (\gamma )}\). After that, we will discuss

Inputting \(\gamma ={\xi }_j\) into the first part of formula (41) generates

Furthermore,

It is identical to (1).

The proof of residue conditions for the remaining three is the same as (1). \(\square\)

The inverse problem

Equation (37) for the jump relation is congruent with

where \({\hat{S}}(z,y;\gamma )=S(z,y;\gamma )-I\). The function’s asymptotic expansion is determined through the use of Proposition 2 and the asymptotic conditions specified in Eq. (24)

where \(\beta =\{\gamma ^4={\mathbb {R}}\}\). By applying formulas (43) and (44), one could achieve the later outcomes

then

It is the spectral functions \(\eta _k\), \(k=1,2,3\),that are are employed to discover the potential function. Reconstructing the potential function is what we shall do. Presented as in Section 2.2 is evidence that

As \(\gamma\) approaches \(\infty\), \(\phi (z,y;\gamma )\) is approximated by \(\upsilon _0+\frac{\upsilon _1}{\gamma }+\frac{\upsilon _2}{\gamma ^2}+\frac{\upsilon _3}{\gamma ^3}+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma ^4})\), satisfying Eq. (24). Consequently,

Compute \(u_{12}(z,y)\) and \(u_{21}(z,y)\) utilizing the spectral functions \(\eta _k(k=1,2,3.)\) in compliance with the relevant equations

Thus, we arrive at the following conclusions:

where \(\Omega (z, y, \gamma )\) satisfies the \(2 \times 2\) matrix Riemann–Hilbert problem.

Analysis of spectral functions and Riemann–Hilbert problem

Spectral functions properties

Definition 1

(With respect to \(f(\gamma )\) and \(g(\gamma )\)) Assuming that \(q_{0}(z)\) is equivalent to q(z, 0), we establish a mapping

where \(f(\gamma )\) and \(g(\gamma )\) are spectral functions.

and

The expression for \(H_1(z, 0; \gamma )\) is formulated in terms of \(q(z, 0; \gamma )\).

Proposition 5

\(f(\gamma )\) and \(g(\gamma )\) exhibit significant characteristics, as listed below

-

(i)

For \(\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2\le 0\), \(f(\gamma )\) and \(g(\gamma )\) are all analytical;

-

(ii)

\(f(\gamma )=1+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }),g(\gamma )={\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma })\) as \(\gamma \rightarrow \infty\), \(\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2\le 0\);

-

(iii)

As \({\mathbb {Q}}\) maps from \(\{f(\eta ),g(\eta )\}\) to \(\{q_0(z)\}\) and since \({\mathbb {S}}^{-1}={\mathbb {Q}}\), the inverse mapping definition of \({\mathbb {S}}\) for \({\mathbb {Q}}\) can be stated as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} q_0(z)= & 2i\lim _{\gamma \rightarrow \infty }(\gamma \Omega ^{(z)}(z,\gamma ))_{12},\\ r_0(z)= & -2i\lim _{\gamma \rightarrow \infty }(\gamma \Omega ^{(z)}(z,\gamma ))_{21}. \end{aligned}$$As \(\Omega ^{(z)}(z,\gamma )\) satisfies the consequent Riemann–Hilbert problem (refer to Theorem 2)

Proof

The demonstration for (i) to (iii) is provided based on Proposition 3. \(\square\)

Theorem 2

Let

\(\Omega ^{(z)}(z,\gamma )\) acknowledges the subsequent Riemann–Hilbert problem.

-

\(\Omega ^{(z)}(z,\gamma )=\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \Omega _{-}^{(z)} (z,\gamma ), & Im \gamma ^2 \le 0 \\ \Omega _{+}^{(z)} (z,\gamma ), & Im \gamma ^2 \ge 0 \end{array} \right.\) is a piecewise analytic function.

-

The jump condition \(\Omega _{+}^{(z)} (z,\gamma )=\Omega _{-}^{(z)} (z,\gamma )S^{(z)} (z,\gamma )\), \(\gamma ^2\in {\mathbb {R}}\) is fulfilled by \(\Omega ^{(z)} (z,\gamma )\),

$$\begin{aligned} S^{(z)} (z,\gamma )=\left( \begin{array}{cc} \frac{1}{f(\gamma )\overline{f({\bar{\gamma }})}} & -\frac{g(\gamma )}{f(\gamma )}e^{-2i\gamma ^2z} \\ \frac{\overline{g({\bar{\gamma }})f({\bar{\gamma }})}}{{f({\gamma })f({\gamma })}}e^{2i\gamma ^2z} & \frac{\overline{f({\bar{\gamma }})}}{{f({\gamma })}} \\ \end{array} \right) ,\,\,\,\gamma ^2\in {\mathbb {R}}. \end{aligned}$$(52) -

\(\Omega ^{(z)} (z,\gamma )=I+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }),\,\,\,\,\gamma \rightarrow \infty .\)

-

\(f(\gamma )\) possesses \(2\Gamma\) simple zeros, denoted as \(\{\varkappa _j\}_{j=1}^{2\Gamma }\), amounting to a total of \(2\Gamma =2\Gamma _1+2\Gamma _2\). It is preferable to assign that \(\varkappa _j\)( \(j=1,2,\cdots ,2\Gamma _1\)) should be allotted to \(\upsilon _1\bigcup \upsilon _2\), and \({\bar{\varkappa }}_j\)(\(j=2\Gamma _1+1,2\Gamma _1+2,\cdots ,2\Gamma\)) should be allotted to \(\upsilon _3\bigcup \upsilon _4\).

-

In the set \([\Omega _{-}^{(z)}(z,\gamma )]_{2}\), there are simple poles located at \(\gamma ={\bar{\varkappa }}_j\), which correspond to values of j ranging from \(2\Gamma _1+1\) to \(2\Gamma\). At \(\gamma ={\varkappa }_j\), one can determine the simple poles in \([\Omega _{+}^{(z)}(z,\gamma )]_{1}\), where \(j=1,2,\cdots ,2\Gamma _1\). As a result, drawing from the above analysis, the residual conditions are as listed below

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned} Res \{[\Omega (z,\gamma )]_{2}, {\bar{\varkappa }}_j \}&=\frac{e^{-2i\bar{\varkappa _j}^2z}{{g({\bar{\varkappa }}_j)}}}{\overline{{\dot{f}}({\varkappa }_j)}}[\Omega ^{(z)}(z,{\bar{\varkappa }}_j)]_{1}, j=2\Gamma _1+1,2\Gamma _1+2,\cdots ,2\Gamma . \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(53)$$\begin{aligned} Res \{[\Omega (z,\gamma )]_{1}, \varkappa _j \}&=\frac{e^{2i{\varkappa _j}^2z}{\overline{g({\bar{\varkappa }}_j)}}}{{\dot{f}}(\varkappa _j)}[\Omega ^{(z)}(z,\varkappa _j)]_{2}, j=1,2,\cdots ,2\Gamma _1. \end{aligned}$$(54)

Proof

Putting \(y=0\) in Eq. (39) allows for the derivation of the later formula

It is through computation that the jump matrix \(S^{(z)} (z,\gamma )\) accords with the jump condition.

We investigate \([\Omega _{+}^{(z)}(z,\gamma )]_{1}\)

By replacing \(\gamma ={\varkappa _j}\) with the first equation of Eq.(53) we deduce

Furthermore,

It could be deemed equivalent to Eq. (54). If the same technique is applied, Eq. (53) can be verified. \(\square\)

Definition 2

(With respect to \(F(\gamma )\) and \(G(\gamma )\)) Assuming that \(h_{0}(y)\), \(h_{1}(y) \in \mathbb {{\hat{S}}}\) , we establish a mapping

where \(F(\gamma )\) and \(G(\gamma )\) are spectral functions.

and

\(H_2(0, L;\gamma )\) is given by

\(H_2^{11}(0,y;\gamma )=-i\gamma ^2k_0h_0+\frac{1}{4}ik_0^{2}h_0^{2}+\frac{1}{2}(k_1h_0-k_0h_1)\);

\(H_2^{12}(0,y;\gamma )=(2\gamma ^3k_0+i\gamma k_1)e^{-2i\int _{0}^{y}\Delta _2(0,\tau )d\tau }\);

\(H_2^{21}(0,y;\gamma )=(2\gamma ^3h_0-i\gamma h_1)e^{2i\int _{0}^{y}\Delta _2(0,\tau )d\tau }\);

\(H_2^{22}(0,y;\gamma )=i\gamma ^2k_0h_0-\frac{1}{4}ik_0^{2}h_0^{2}-\frac{1}{2}(k_1h_0-k_0h_1)\),

where \(\Delta _2(0,\tau )=0\).

Proposition 6

\(F(\gamma )\) and \(G(\gamma )\) exhibit significant characteristics, as listed below

-

(i)

For \(Im\gamma ^4\ge 0\), \(F(\gamma )\) and \(G(\gamma )\) are all analytical;

-

(ii)

\(F(\gamma )=1+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }),G(\gamma )={\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma })\) as \(\gamma \rightarrow \infty\), \(Im\gamma ^4\ge 0\);

-

(iii)

As \(\mathbb {{\hat{Q}}}\) maps from \(\{F(\gamma ),G(\gamma ) \}\) to \(\{h_0(y),h_1(y)\}\) and since \(\mathbb {{\hat{S}}}^{-1}=\mathbb {{\hat{Q}}}\), the inverse mapping definition of \(\mathbb {{\hat{S}}}\) for \(\mathbb {{\hat{Q}}}\) can be stated as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} h_0(y)=2i\lim _{\gamma \rightarrow \infty }(\gamma \Omega ^{(y)}(y,\gamma ))_{12}\end{aligned}$$(56)$$\begin{aligned} g_0(y)=-2i\lim _{\gamma \rightarrow \infty }(\gamma \Omega ^{(y)}(y,\gamma ))_{21}\end{aligned}$$(57)As \(\Omega ^{(y)}(y,\gamma )\) satisfies the consequent Riemann–Hilbert problem (refer to Theorem 3).

Proof

The demonstration for (i) to (iii) is provided based on Proposition 3. \(\square\)

Theorem 3

Let

\(\Omega ^{(y)}(y,\gamma )\) acknowledges the subsequent Riemann–Hilbert problem.

-

\(\Omega ^{(y)}(y,\gamma )=\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \Omega _{+}^{(y)} (y,\gamma ), & Im \gamma ^4 \ge 0 \\ \Omega _{-}^{(y)} (y,\gamma ), & Im \gamma ^4 \le 0 \end{array} \right.\) is a piecewise analytic function.

-

The jump condition \(\Omega _{+}^{(y)} (y,\gamma )=\Omega _{-}^{(y)} (y,\gamma )S^{(y)} (y,\gamma )\), \(\gamma ^4\in {\mathbb {R}}\) is fulfilled by \(\Omega _{+}^{(y)} (y,\gamma )\),

$$\begin{aligned} S^{(y)} (y,\gamma )=\left( \begin{array}{cc} 1 & -\frac{\overline{G({\bar{\gamma }})}}{F(\gamma )}e^{4i\gamma ^4y} \\ \frac{G(\gamma )}{\overline{F({\bar{\gamma }})}}e^{-4i\gamma ^4y} & \frac{1}{F(\gamma )\overline{F({\bar{\gamma }})}} \\ \end{array} \right) ,\,\,\,\gamma ^4\in {\mathbb {R}}. \end{aligned}$$(59) -

\(\Omega ^{(y)} (y,\gamma )=I+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }),\,\,\,\,\gamma \rightarrow \infty .\)

-

\(F(\gamma )\) possesses 2N simple zeros, denoted as \(\{\digamma _j\}_{1}^{2N}\), amounting a total of \(2N=2N_1+2N_2\). It is preferable to assign that\(\digamma _j\)(\(j=1,2,\cdots ,2N_1\)) should be allotted to \(\upsilon _1\bigcup \upsilon _3\), and \({\bar{\digamma }}_j\)(\(j=2N_1+1,2N_1+2,\cdots ,2N\)) should be alloted to \(\upsilon _2\bigcup \upsilon _4\).

-

In the set \([\Omega _{+}^{(y)}(y,\gamma )]_{2}\), there are simple poles located at \(\gamma =\digamma _j\), which correspond to values of j ranging from 1 to \(2N_1\). At \(\gamma ={\bar{\digamma }}_j\), one can determine the simple poles in \([\Omega _{-}^{(y)}(y,\gamma )]_{1}\), where \(j=2N_1+1,2N_1+2,\cdots ,2N\). As a result, drawing from the above analysis, the residual conditions are as listed below

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned}Res \{[\Omega ^{(y)}(y,\gamma )]_{2}, \digamma _j \}=\frac{e^{4i\digamma _j^4y}}{{\dot{F}}(\digamma _j)G(\digamma _j)}[\Omega ^{(y)}(y,\digamma _j)]_{1}, j=1,2,\cdots ,2N_1,\end{aligned}\end{aligned}$$(60)$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned}Res \{[\Omega ^{(y)}(y,\gamma )]_{1}, {\bar{\digamma }}_j \}=\frac{e^{-4i\bar{\digamma _j}^4y}}{\overline{{\dot{F}}({\digamma }_j)}\overline{G({\bar{\digamma }}_j)}}[\gamma ^{(y)}(y,\bar{\digamma _j})]_{2}, j=2N_1+1,2N_1+2,\cdots ,2N.\end{aligned}\end{aligned}$$(61)

Proof

Putting \(z=0\) in Eq. (40) allows for the derivation of the later formula

It is through computation that the jump matrix \(S^{(y)} (y,\gamma )\) accords with the jump condition.

We investigate \([\Omega ^{(y)}(y,\gamma )]_{2}\)

By replacing \(\gamma ={\digamma _j}\) as per the second equation of Eq.(60), we derive

Furthermore,

It could be deemed equivalent to Eq. (60). If the same technique is applied, Eq. (61) can be verified. \(\square\)

Definition 3

(With respect to \(\rho (\gamma )\) and \(\kappa (\gamma )\)) Assuming that \(q_L(z)\) is equivalent to q(z, L) and \(r_L(z)\) is equivalent to r(z, L). In addition, the spectral functions are taken into account

We establish a mapping

where

and

\(H_1(z, L;\gamma )\) is expressed as a function of by \(q(z,L;\gamma )\)

Proposition 7

\(\rho (\gamma )\) and \(\kappa (\gamma )\) exhibit significant characteristics, as listed below

-

(i)

For \(\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2\le 0\), \(\rho (\gamma )\) and \(\kappa (\gamma )\) are all analytical;

-

(ii)

\(\rho (\gamma )=1+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }), \kappa (\gamma )={\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma })\) as \(\gamma \rightarrow \infty\), \(\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2\le 0\);

-

(iii)

\(\rho (\gamma )\overline{\rho ({\bar{\gamma }})}-\kappa (\gamma )\overline{\kappa ({\bar{\gamma }})}=1\), \(\gamma ^2\in {\mathbb {R}}\);

-

(iv)

\(\rho (-\gamma )=\rho (\gamma ),\kappa (-\gamma )=-\kappa (\gamma )\), \(\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2\le 0\);

-

(v)

As \(\mathbb {\hat{{\hat{Q}}}}\) maps from \(\{\rho (\gamma ),\kappa (\gamma ) \}\) to \(\{q_L(z)\}\) and since \(\mathbb {\hat{{\hat{S}}}}^{-1}=\mathbb {\hat{{\hat{Q}}}}\), the inverse mapping definition of \(\mathbb {\hat{{\hat{S}}}}\) for \(\mathbb {\hat{{\hat{Q}}}}\) can be stated as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} q_L(z)=2i\lim _{\gamma \rightarrow \infty }(\gamma \Omega ^{(L)}(z,\gamma ))_{12},\\ r_L(z)=-2i\lim _{\gamma \rightarrow \infty }(\gamma \Omega ^{(L)}(z,\gamma ))_{21}. \end{aligned}$$As \(\Omega ^{(L)}(z,\gamma )\) satisfies the consequent Riemann–Hilbert problem (Refer to Theorem 4).

Proof

The demonstration for (i) to (iii) is provided based on Proposition 3. \(\square\)

Theorem 4

Let

\(\Omega ^{(L)}(z,\gamma )\) acknowledges the subsequent Riemann–Hillbert problem.

-

\(\Omega ^{(L)}(z,\gamma )=\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \Omega _{-}^{(L)} (z,\gamma ), & Im \gamma ^2 \le 0 \\ \Omega _{+}^{(L)} (z,\gamma ), & Im \gamma ^2 \ge 0 \end{array} \right.\) is a piecewise analytic function.

-

\(\Omega ^{(L)}(z,\gamma )\) meets the jump condition \(\Omega _{+}^{(L)} (z,\gamma )=\Omega _{-}^{(L)} (z,\gamma )S^{(L)} (z,\gamma )\), \(\gamma ^2\in {\mathbb {R}}\),

$$\begin{aligned} S^{(L)} (z,\gamma )=\left( \begin{array}{cc} \frac{1}{\rho (\gamma )\overline{\rho ({\bar{\gamma }})}} & -\frac{\rho ({\gamma })}{\kappa (\gamma )}e^{2i(\gamma ^2z+2\gamma ^4L)} \\ \frac{\kappa (\gamma )}{\rho ({\gamma })}e^{-2i(\gamma ^2z+2\gamma ^4L)} & -\frac{\overline{\rho ({\bar{\gamma }})}}{\kappa (\gamma )}e^{2i(\gamma ^2z+2\gamma ^4L)} \\ \end{array} \right) ,\,\,\,\gamma ^2\in {\mathbb {R}}. \end{aligned}$$(64) -

\(\Omega ^{(L)} (z,\gamma )=I+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }),\,\,\,\,\gamma \rightarrow \infty .\)

-

\(\rho (\gamma )\) possess \(2\iota\) simple zeros, denoted as \(\{\xi _j\}_{j=1}^{2\iota }\), amounting to a total of \(2\iota =2\iota _1+2\iota _2\). It is preferable to assign that \(\xi _j\)(\(j=1,2,\cdots ,2\iota _1\)) should be alloted to \(\upsilon _1\bigcup \upsilon _2\), and \({\bar{\xi }}_j\)(\(j=2\iota _1+1,2\iota _1+2,\cdots ,2\iota\)) should be alloted to \(\upsilon _3\bigcup \upsilon _4\).

-

In the set \([\Omega _{+}^{(L)}(z,\gamma )]_{1}\), there are simple poles located at \(\gamma =\xi _j\), which correspond to values of j ranging from \(j=1\) to \(2\iota _1\). At \(\gamma ={\bar{\xi }}_j\), one can determine the simple poles in \([\Omega _{-}^{(L)}(z,\gamma )]_{2}\), where \(j=2\iota _1+1,2\iota _1+2,\cdots ,2\iota\). As a result, drawing from the above analysis, the residual conditions are as listed below

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned} Res \{[\Omega ^{(L)}(z,\gamma )]_{1}, \xi _j \}=\frac{e^{-2i(\xi _j^2z+2\xi _j^4y)}\kappa (\xi _j)}{{\dot{\rho }}(\xi _j)}[\Omega ^{(L)}(z,\xi _j)]_{2}, \\j=1,2,\cdots ,2\iota _1, \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(65)$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned} Res \{[\Omega ^{(L)}(z,\gamma )]_{2}, {\bar{\xi }}_j \}=\frac{e^{2i({\bar{\xi }}_j^2z+2{\bar{\xi }}_j^4y)}\overline{\kappa \bar{(\xi _j)}}}{\overline{{\dot{\rho }}(\xi _j)}}[\Omega ^{(L)}(z,{\bar{\xi }}_j)]_{1}, \\j=2\iota _1+1,2\iota _1+2,\cdots ,2\iota . \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(66)

Proof

Putting \(y=L\) in Eq. (39) allows for the derivation of the later formula

It is through computation that the jump matrix \(S^{(y)} (y,\gamma )\) accords with the jump condition.

We investigate \([\Omega ^{(L)}(z,\gamma )]_{1}\)

By replacing \(\gamma ={\xi _j}\) with the second equation of Eq. (65) we deduce

Furthermore,

It could be deemed equivalent to Eq.(62). If the same technique is applied, Eq.(63) can be verified. \(\square\)

Riemann–Hilbert problem

Theorem 5

\(f(\gamma )\), \(G(\gamma )\), \(F(\gamma )\), and \(G(\gamma )\) define the matrix functions \(a(\gamma )\) and \(A(\gamma )\), respectively (see Eq. (34)) The definitions of \(q_0(x)\), \(h_0(y)\), and \(h_1(y)\) in Definitions 1 and 2correspond to \(f(\gamma )\), \(g(\gamma )\), \(F(\gamma )\), and \(G(\gamma )\) as indicated by the spectral functions. Assume that \(f(\gamma )\), \(g(\gamma )\), \(F(\gamma )\), and \(G(\gamma )\) meet the global relation.

where \(s^{+}(\gamma )\) is an entire function. \(a(\gamma )=\eta _2(0,0;\gamma )\), \(A(\gamma )=A(L,\gamma )=(e^{2i\gamma ^4L}\eta _1(0,L;\gamma ))^{-1}\). Viewed as the answer to the \(2 \times 2\) Riemann–Hilbert problem, \(\Omega (z, y, \gamma )\) is defined.

-

The slice analytic function \(\Omega (z, y, \gamma )\) exhibits jumps at the locations \(\upsilon _1\), \(\upsilon _2\), \(\upsilon _3\), and \(\upsilon _4\).

-

\(\Omega (z, y, \gamma )\) meets the jump condition

$$\begin{aligned} \Omega _{+}(z, y, \gamma )=\Omega _{-}(z, y, \gamma )S(z, y, \gamma ),\,\,\,\gamma ^{4} \in {\mathbb {R}}. \end{aligned}$$(68) -

Simple poles are present at \(\gamma ={\bar{\varkappa }}_j\), \(j=2\Gamma _1+1, 2\Gamma _1+2\cdots ,2\Gamma\), and \(\gamma ={\bar{\xi }}_j\), \(j=2\iota _1+1,2\iota _2+1\cdots ,2\iota\) within \([\Omega (z,y;\gamma )]_{2}\). Furthermore, there are simple poles at \(\gamma ={\varkappa }_j\), \(j=1,2,\cdots ,2\Gamma _1\), and \(\gamma ={\xi }_j\), \(j=1,2,\cdots ,2\iota _1\) within \([\Omega (z,y;\gamma )]_{1}\).

-

\(\Omega (z,y;\gamma )=I+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }),\,\,\,\gamma \rightarrow \infty\).

-

It is the case that \(\Omega (z,y;\gamma )\) achieves the residue relationship referred to in Hypothesis 1.

Thus, both existent and distinctive is the function \(\Omega (z,y;\gamma )\).

In addition, the equations Eqs. (1) and (2) yield solutions termed asq(z, y) and r(z, y), correspondingly.

Theorem 6

Only when the boundary condition \(\Omega (z,y;\gamma )\rightarrow 0\) (\(\gamma \rightarrow \infty )\) is imposed does the Riemann–Hilbert problem possess merely zero solutions, in accordance with Theorem 5.

Proof

Define

where the z and y are dependence. Through the utilization of symmetry relations, we can deduce that

Then

For \(Im\gamma ^4\in {\mathbb {R}}\), \(\vartheta _{+}(\gamma )=\vartheta _{-}(\gamma )\), in accordance with Eqs. (70) and (71). As a result, the functions \(\vartheta _{+}(\eta )\) and \(\vartheta _{-}(\eta )\) form a complete function that is zero throughout infinity. Experiments have led to the finding that the matrix \(G_1(i\beta )\) with \(\beta \in {\mathbb {R}}\) is of positive definiteness. Considering that \(\vartheta _{-}(\beta )\) completely disappears for \(\beta \in i{\mathbb {R}}\), i.e.

Considering that \(\beta \in {\mathbb {R}}\), it can be inferred that \(\Omega _+(i\beta )=0\). Consequently, the vanishing of both \(\Omega _{+}(\gamma )\) and \(\Omega _{-}(\gamma )\) takes place in a same manner. \(\square\)

Proposition 8

The coupled GI equation is satisfied by both q(z, y) and r(z, y).

Proof

By utilizing the arguments presented in the dressing method, it could be immediately corroborated that, in the case where we stipulate \(\Omega (z,y;\gamma )\) as the resolution of the Riemann–Hilbert problem, and formulate q(z, y) and r(z, y) with respect to \(\Omega (z,y;\gamma )\) by means of Eqs. (49) and (50). Moreover, it is worth mentioning that q(z, y) and r(z, y) meet the Lax pair for this equation. As a consequence, the coupled GI equation can be efficiently solved for q(z, y) and r(z, y).

In the situation that \(y = 0\), \(q(z, 0) = q_0(z)\) is likewise valid. \(\square\)

Proof

By observing Eq. (42) at time \(y = 0\), it is possible to decompose the jump matrix into a multiplication of matrices with dimensions (\(2\times 2\)).

After performing the necessary calculations, we find that when \(y=0\), the derived result is matched against Eq. (38). It can be observed that \(\Omega _{-}\) in \(\upsilon _2\) transforms into \(\Omega _{+}\), and similarly, \(\Omega _{+}\) in \(\upsilon _3\) transforms into \(\Omega _{-}\). Primal relation \(\Omega ^{2}_{+}(z,0,\gamma )=\Omega ^{2}_{-}(z,0,\gamma )S_4(x,0,\eta )\), present relation \(\Omega ^{(z)}(z,0,\gamma )=\Omega (z,0,\gamma )S_4(z,0,\gamma )\). Primal relation \(\Omega ^{1}_{+}(z,0,\gamma )=\Omega ^{2}_{-}(z,0,\gamma )S_2(z,0,\gamma )\) and \(\Omega ^{2}_{-}(z,0,\gamma )=\Omega ^{1}_{+}(z,0,\gamma ) S_2^{-1}(z,0,\gamma )\), present relation \(\Omega ^{(z)}(z,0,\gamma )=\Omega (z,0,\gamma )S_2^{-1}(z,0,\gamma )\). The remaining regions maintain their original state, thereby ensuring the invariability of the subsequent specification.

Define

then we set

where \(\Omega ^{(z)}(z,0,\gamma )\) satisfies

-

$$\begin{aligned} \Omega _{+}^{(z)}(z,0,\gamma )=\Omega _{-}^{(z)}(z,\gamma )G_1^{(x)}(z,0,\gamma ),\,\,\,\,\gamma \in {\mathbb {R}}; \end{aligned}$$(77)$$\begin{aligned} \Omega _{+}^{(z)}(z,0,\gamma )=\Omega _{-}^{(z)}(z,\gamma )(G_3^{(x)}(z,0,\gamma ))^{-1},\,\,\,\,\gamma ^2\in {\mathbb {R}}. \end{aligned}$$(78)

-

\(\Omega ^{(z)}(z,0,\gamma )=I+{\mathcal {O}}(\frac{1}{\gamma }),\,\,\,\,\gamma \rightarrow \infty .\)

According to Eq. (49)

Let

we can figure it out

It can be considered the same as Eq.(75). We can verify the validity of Eq.(76) by employing the same approach. Based on the above results, we can get \(q_0=q(z,0)\).

For the condition that \(z = 0\), \(q(0, y)=h_0(y)\) and \(q_z(0, y)=h_1(y)\) are likewise valid. \(\square\)

Proof

Denote \(\Omega ^{(0,y)}(0,y,\gamma )\) as being defined via

For the given situation, \(K(y, \gamma )\) is determined by \(K^{(1)}(y, \gamma )\) when \(\gamma \in v_1\), by \(K^{(2)}(y, \gamma )\) for \(\gamma \in v_2\), via \(K^{(3)}(y, \gamma )\) in the case of \(\gamma \in v_3\), and through \(K^{(4)}(y, \gamma )\) if \(\gamma \in v_4\).

When \(y=0\), a comparison between Eqs. (83) and (34) reveals that there is no change in the region.

Let

We can deduce the subsequent associations.

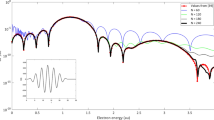

It is observed that Eq. (42) are still meets the boundary requirements \(\Omega (0,y;\gamma )\) (see Fig. 5).

\(\square\)

Assuming we can find matrices \(K^{(1)}\) and \(K^{(2)}\) exhibit continuity for \(\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2 >0\), as well as the matrices \(K^{(3)}\) and \(K^{(4)}\) that are continuous for \(\textrm{Im}\gamma ^2 <0\). As \(\gamma \rightarrow \infty\), the matrix K tends towards the identity matrix. As a consequence, K fulfills the following relation.

Proof

By substituting \(\Omega _{+}^{1}(0,y,\gamma )=\Omega _{-}^{1}(0,y,\gamma )S_{2}(y,\gamma )\) into the equations given above, we obtain the following

It is the same as the formula Eq. (88).

In the same manner, we can demonstrate Eqs. (89), (90), and (91).

\(\square\)

Riemann–Hilbert problem

It is possible to establish a setting based on Eqs. (10)–(12)

which implies that

where H represents the Hermitian matrix and \(r=-{\bar{q}}\).

Based on the Lax pair Eq. (10), one can infer that

In the context of a scattering phenomenon, the asymptotic behavior of \(\Phi _{\pm }\) can be termed as

where I represents the \(2\times 2\) unit matrix and the subscript of \(\Phi _{\pm }\) evinces the positive and negative sides of the z-axis. By employing Eq. (96) in conjunction with Abel’s formula, we derive

Assuming

as stated in Eq. (99), satisfy Eq. (10), it can be inferred that there is a linear relationship between G and H.

Denote

and we have

which implies that

where

is the scattering matrix. Through the application of Eqs. (98) and (102), we infer

In light of the preceding discourse, our attention is directed towards (G, H) that satisfy the following equation

Given that Eq. (15) is in the form of a total differential, and its integral is path-independent, we can select two specific paths: one from the point \((-\infty ,y)\) to the point (z, y), and the other from the point (z, y) to the point \((\infty ,y)\).

If the integrals on the right sides of Eqs. (106)–(107) are convergent, it can be observed that \(\Phi _{\pm }(z,\gamma )\) are analytical continuations beyond the real axis where \(\gamma \in {\mathbb {R}}\). Furthermore, it can be deduced that the first column of \(\Phi _{+}(z,\gamma )\) and the second column of \(\Phi _{-}(z,\gamma )\) can be analytically extended to the lower half-plane where \(\gamma \in C_{-}\). Likewise, the second column of \(\Phi _{+}(z,\gamma )\) and the first column of \(\Phi _{-}(z,\gamma )\) can be analytically extended to the upper half-plane where \(\gamma \in C_{+}\).

We construct RH problems and introduce tokens \(\theta _{1}=\left( \begin{array}{cc}1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \\ \end{array}\right)\), and \(\theta _{2}=\left( \begin{array}{cc}0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \\ \end{array}\right)\). The following notation is defined:

Then the Jost solutions

are analytic in \(\gamma \in {\mathbb {C}}_{+}\) and

are analytic in \(\gamma \in {\mathbb {C}}_{-}\).

It can be readily found that

and

by virtue of Eqs. (106) and (107). With the assistance of the adjoint scattering equation, we are able to obtain the analytic counterpart of \(T^{+}\) within \({\mathbb {C}}_{-}\). It is straightforward to verify that \(\Phi _{+}^{-1}\) satisfies Eq. (102).

In the subsequent discussion, we will represent \(G^{-1}\) and \(H^{-1}\) as follows:

Similarly, it is readily observable that the adjoint Jost solutions

are analytic in \(\gamma \in {\mathbb {C}}_{-}\) and

are analytic in \(\gamma \in {\mathbb {C}}_{+}\). Furthermore,

and

Based on the equations presented above, we arrive at

where the superscripts ± are used to signify the half-plane of analyticity. Indeed, these analytic characteristics of the Jost solutions exert a direct effect on the scattering matrix \(J(\gamma )\).

It is evident that the analytic properties of J and \(J^{-1}\) can be interpreted as

where the superscripts ± specify in which half of the \(\gamma\) plane the corresponding scattering elements are analytic. Moreover, we observe that

and the analytic properties of \(J^{-1}\) can be derived from those of J.

Theorem 7

The functions \(\Phi _l(\gamma ), (l = 1,2)\), as well as \(J(\gamma )\), exhibit symmetry properties

where the superscript H, which stands for the conjugate mapping of a matrix.

Proof

Substituting \({\overline{\gamma }}\) for \(\gamma\) in Eq. (13),

Given that \(W_2(\gamma )=-W_2^{H}(\gamma )\), we can conclude that

We note that

and it exhibits the asymptotic behavior where \(\Phi _{l}^{-1}(\gamma ),\Phi _{l}^{H}({\overline{\gamma }})\rightarrow I\) as\(\quad |z|\rightarrow \infty\). Thereafter, we possess the symmetry property as described in Eq. (122). Upon expanding Eq. (122), we get

Likewise, by substituting \({\overline{\gamma }}\) for \(\gamma\) in Eq. (101), we derive

When substituting Eq. (119) into Eq. (122), we derive the symmetry property shown in Eq. (120). Moreover, we find that

\(\square\)

Theorem 8

\(T_{\pm }(\gamma )\) possess the following properties

Proof

Based on the properties given in Eqs. (122) and (109), we derive

Moreover, we can derive the following equations:

Likewise, we can deduce \(\det \left( T_{-}\right) =j_{22}(z)\).

To sum up the aforementioned results, we reach that

where jump matrix is

\(\square\)

Proof

As the initial value \(q_0(z)\) is in the Schwartz space, it is recognized that the Lax pair Eq. (10) admits a Jost solution with the subsequent asymptotic manifestation

where \(\alpha (z)=\eta ^2z + 2\eta ^4y\).

We aim to demonstrate the jump relationship by utilizing both both \(e^{\pm i\alpha (z)\theta _{3}}\theta _{1}=\theta _{1}\) and \(e^{\pm i\alpha (z)\theta _{3}}\theta _{2}=\theta _{2}\), which will allow us to derive

We will concentrate on solving the Riemann–Hilbert problem and gaining a solution for the Lax pair. When expanding \(T_{\pm }\) and \(\Phi\) at large \(\gamma\) as shown below,

and utilizing Eqs. (67), (109), (114), (130), and (131), we discover that

\(\square\)

The solution of the Riemann–Hilbert problem

The regular Riemann–Hilbert problem

The regularity implies that both \(\det T_{\pm }\ne 0\) within their respective analytic regions. When the canonical normalization condition is applied, the solution to this regular Riemann–Hilbert problem is unique. Nevertheless, the solution is not given in an explicit form, but rather in a formal one.

Theorem 9

Let L be a simple, smooth curve or line that divides the complex \(\gamma\) plane into two regions, \(\upsilon _+\) and \(\upsilon _-\). Assume that \(f(\tau )\) is a continuous function defined on the contour L. Consider a function \(\phi (\gamma )\) that is sectionally analytic in \(\Omega _+\) and \(\Omega _-\), and tends to zero at infinity. On the contour L, the relationship \(\phi _+(\gamma ) - \phi _-(\gamma ) = f(\gamma )\) holds for \(\gamma \in L\), where \(\phi _{\pm }(\gamma )\) represents the limit of \(\phi (\gamma )\) as \(\gamma\) approaches \(\tau \in L\) from within \(\Gamma ^{\pm }\). Then we possess

To apply the Plemelj formula to the regular Riemann–Hilbert problem, it is necessary to reformulate the equation

where \({\hat{G}}=I-G=-E\begin{pmatrix}0 & -j_{12}\\ j_{21} & 0\end{pmatrix}E^{-1}.\)

By utilizing the Plemelj formula and incorporating the boundary conditions, the distinctive solution of the regular Riemann–Hilbert problem is capable of being formulated by means of the subsequent equation

The non-regular Riemann–Hilbert problem

The irregularity connotes that \(\det T_{\pm }\) encompasses certain zeros within its analytic domain. Thereafter

this equation demonstrates that the number of zeros of \(\det T_+(\gamma )\) is identical to that of \(\det T_-(\gamma )\). We postulate that \(\det T_+\) and \(\det T_-\) possess N zeros \(\gamma _h\) residing in \({\mathbb {D}}_{+}\) and \({\mathbb {D}}_{-}\), respectively, for \(1 \le h \le N\), where N represents the cardinality of the set of zeros. In addition, we obtain the subsequent relationship

\({\bar{\gamma }}_h\) signifies the complex conjugate of \(\gamma _h\). Under the premise of streamlining the analysis, we postulate that each zero pertaining to \(\det T_{\pm }\) is characterized as a simple zero. At this stage, the kernels of \(T_{+}(\gamma _h)\) and \(T_{-}(\gamma _h)\) merely comprise a sole column vector \(\omega _h\) and a lone row vector \(\hat{\omega _h}\), i.e.,

By leveraging property Eq.(129), we determine that \(\omega _{h}(\gamma _{h})=\omega _{h}^{H}(\gamma _{h})\).

Theorem 10

The resolution for the non-regular Riemann–Hilbert problem, given by Eq. (129), featuring zeros as described in Eq. (136), under the canonical normalization conditions outlined in Eq. (111) and Eq. (116) is constituted as follows

where

W denotes an \(N\times N\) matrix, where the element in the (l, k)-th position is defined as follows:

and \({\hat{T}}_{\pm }(\gamma )\) represents the sole solution to the succeeding regular Riemann–Hilbert problem

where \(T_{\pm }(\gamma )\) are analytic functions in \({\mathbb {D}}_{\pm }\), respectively, and \(T_{\pm }\rightarrow I\) as \(\gamma \rightarrow \infty\).

The resolution of the non-regular Riemann–Hilbert problem presented in Eq. (129), as stated in Theorem 7, and the scattering data requisite for resolving this non-regular Riemann–Hilbert problem are constituted by \(\{j_{21}, j_{12}, \gamma _h, {\overline{\gamma }}_h, \omega _h, {\overline{\omega }}_h, 1 \le h \le N\}\).

By computing the z-derivative and y-derivative with respect to the equation \(T_ + (\gamma _h)\omega _h(\gamma _h) = 0\), we derive

Plug Eq. (109) into Eq. (142) and Eq. (143), thereby obtaining

from which we derive that

where \(\omega _{h,0}\) represents a constant column vector.

Observing that both \(\Phi _1 E\) and \(\Phi _2 E\) fulfill the Eq. (13), through the application of the relation (102), we derive

Moreover, we procure

Subsequently,

where \(j_{12}(0,0)\) and \(j_{21}(0,0)\) are chosen as arbitrary constants.

In accordance with the formal resolution of the regular Riemann-Hilbert problem, the formal solution Eq. (141) can be formulated as

Hence, when \(\gamma \rightarrow \infty\),

and

Moreover as \(\gamma \rightarrow \infty\),

By inserting the asymptotic expansions denoted as Eqs. (130), (148) and (149) into Eq. (137) and then equating the coefficients of \(\gamma ^{-1}\) on both sides, we arrive at

We resolve the Riemann–Hilbert problem (129) within the reflectionless scenario where \(j_{21}(0,0) = j_{12}(0,0) = 0\), thereby resulting in \({\hat{G}} = 0\). Subsequently, (150) gets simplified as

and

where \({\hat{\omega }}_k\) is defined by (145), and M is provided in accordance with (139).

Moreover, we bring in the notation

Thereafter, the solutions for q and r can be explicitly expressed as

where the constituents of the \(N \times N\) matrix W are provided in accordance with

and \(\omega _{k0}=(c_{k},1)^{T}\), assuming generality is not lost.

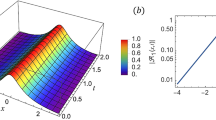

Subsequently, by assuming \(N = 1\) in Eq. (154), we derive the single-soliton solution

Let

with a denoting the real part and b representing the imaginary part of \(\gamma\). We gain

Hence, the single-soliton solutions can be rephrased as

which are depicted in Fig. 6. a represents the speed, and b represents the amplitude factor.

One-soliton solution of (159) under the conditions of \(a=0.05\),\(b=0.8\),\(\delta =0\),\(\kappa =0\).

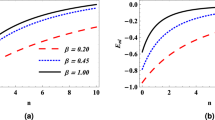

By setting \(N = 2\) in (154), we derive the two-soliton solution

where

Conclusion

This research adopts the Fokas method to explore the coupled Gerdjikov–Ivanov equation regarding a half-line. Moreover, we examined the zero boundary condition at infinity for the Coupled Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation via the Riemann-Hilbert methodology. We introduce eigenfunctions for spectral analysis and establish an inverse problem and a basic Riemann–Hilbert problem. Additionally, we provide insights into the global relationship among spectral functions. The Fokas method, being broader in scope compared to the inverse scattering method, offers a useful means for dissecting the initial boundary value problems associated with both linear and nonlinear PDEs. In contrast to the inverse scattering method, it holds a distinct advantage when it comes to probing the long-term asymptotic behavior of solutions. Accordingly, by exploiting this advantage, future work will seek to employ the Deift–Zhou nonlinear steepest descent method to investigate the long-time asymptotic behavior of solutions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Fokas, A. Inverse scattering of first-order systems in the plane related to nonlinear multidimensional equations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 51, 3. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.51.3 (1974).

Gardner, C., Clifford, S. & Kruskal, M. The Korteweg-de Vries equation and generalizations. vi. method for exact solutions. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 27, 97–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpa.3160270108 (1974).

Dong, H., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, X. The new integrable symplectic map and the symmetry of integrable nonlinear lattice equation. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 36, 354–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnsns.2015.12.015 (2016).

Fang, Y., Dong, H., Hou, Y. & Kong, Y. Frobenius integrable decompositions of nonlinear evolution equations with modified term. Appl. Math. Comput. 226, 435–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2013.10.047 (2014).

Fokas, A. A unified transform method for solving linear and certain nonlinear pdes. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 453, 1411–1443. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1997.0077 (1997).

Fokas, A. Integrable nonlinear evolution equations on a finite interval. Commun. Math. Phys. 263, 133–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00220-005-1495-2 (2006).

Fokas, A. A unified transform method for solving linear and certain nonlinear pdes. J. Appl. Phys. 453, 1411–1443. https://doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/37/23/009 (2004).

Deift, P. & Zhou, X. A steepest descent method for oscillatory Riemann-Hilbert problems. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 26, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1090/S0273-0979-1992-00253-7 (1992).

Fokas, A., Its, A. & Sung, L. The nonlinear Schrödinger equation on the half-line. Nonlinearity 18, 1771–1822. https://doi.org/10.1090/tran/6734 (2005).

Boutet, D., Monvel, A. & Fokas, A. The mkdv equation on the half-line. J. Inst. Math. Jussieu 3, 139–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474748004000052 (2004).

Boutet, D., Monvel, A. & Shepelsky, D. Initial boundary value problem for the mkdv equation on a finite interval. Aann. L Inst. Fourier 54, 1477–1495. https://doi.org/10.5802/aif.2056 (2004).

Monvel, A. & Shepelsky, D. Long time asymptotics of the Camassa-Holm equation on the half-line. Aann. L Inst. Fourier 7, 59. https://doi.org/10.5802/aif.2514 (2009).

Lenells, J. & Fokas, A. On a novel integrable generalization of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Nonlinearity 22, 709–722. https://doi.org/10.1088/0951-7715/24/1/009 (2009).

Lenells, J. & Fokas, A. A. An integrable generalization of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation on the half-line and solitons. Inverse Prob. 25, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00220-011-1243-8 (2009).

Lenells, J. An integrable generalization of the sine-Gordon equation on the half-line. IMA J. Appl. Math. 76, 554–572. https://doi.org/10.1093/imamat/hxq049 (2011).

Lenells, J. Boundary value problems for the stationary axisymmetric Einstein equations: A disk rotating around a black hole. Commun. Math. Phys. 304, 585–635. https://doi.org/10.1088/0951-7715/22/1/002 (2011).

Lenells, J. & Fokas, A. Boundary-value problems for the stationary axisymmetric Einstein equations: A rotating disc. Nonlinearity 24, 177–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physd.2008.07.005 (2011).

Xu, J. & Fan, E. A Riemann-Hilbert approach to the initial-boundary problem for derivative nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Acta Math. Sci. 34, 973–994. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0252-9602(14)60063-1 (2014).

Xu, J. & Fan, E. Initial-boundary value problem for integrable nonlinear evolution equation with \(3\times 3\) lax pairs on the interval. Stud. Appl. Math. 136, 321–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/sapm.12108 (2016).

Chen, M., Chen, Y. & Fan, E. The Riemann-Hilbert analysis to the Pollaczek-Jacobi type orthogonal polynomials. Stud. Appl. Math. 143, 42–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/sapm.12259 (2019).

Chen, M., Fan, E. & He, J. Riemann-Hilbert approach and the soliton solutions of the discrete mkdv equations. Chaos Solit. Fract. 168, 113209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2023.113209 (2023).

Zhao, P. & Fan, E. A Riemann-Hilbert method to algebro-geometric solutions of the Korteweg-de Vries equation. Physica D 454, 133879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physd.2023.133879 (2023).

Wen, L., Zhang, N. & Fan, E. N-soliton solution of the Kundu-type equation via Riemann-Hilbert approach. Acta Math. Sci. 40, 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10473-020-0108-x (2020).

Zhu, Q., Xu, J. & Fan, E. Initial-boundary value problem for two-component Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation with 3 \(\times\) 3 lax pair on half-line. Commun. Theor. Phys. 68, 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1088/0253-6102/68/4/425 (2017).

Zhang, N., Xia, T. & Hu, B. A Riemann-Hilbert approach to the complex Sharma-Tasso-Olver equation on the half line. Commun. Theor. Phys. 68, 580. https://doi.org/10.1088/0253-6102/68/5/580 (2017).

Zhang, N., Xia, T. & Fan, E. A Riemann-Hilbert approach to the Chen-Lee-Liu equation on the half line. Acta Math. Sci. 34, 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10255-018-0765-7 (2018).

Hu, B., Zhang, L., Xia, T. & Zhang, N. On the Riemann-Hilbert problem of the Kundu equation. Complex Var Elliptic 381, 125262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2020.125262 (2020).

Hu, B., Zhang, L. & Xia, T. On the Riemann-Hilbert problem of a generalized derivative nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Commun. Theor. Phys. 73, 015002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1572-9494/abc3ac (2021).

Hu, B., Zhang, L., Lin, J. & Wei, H. Riemann-Hilbert problem for the fifth-order modified Korteweg-de Vries equation with the prescribed initial and boundary values. Commun. Theor. Phys. 75, 065004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1572-9494/acce97 (2023).

Hu, J. & Zhang, N. Initial boundary value problem for the coupled Kundu equations on the half-line. Axioms. 13, 2075–2680. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms13090579 (2024).

Wu, F. & Huang, L. N-soliton solutions for the coupled extended modified kdv equations via Riemann-Hilbert approach. Appl. Math. Lett. 134, 108390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aml.2022.108390 (2022).

Wu, F. & Huang, L. Riemann-Hilbert approach and n-soliton solutions of the coupled generalized Sasa-Satsuma equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 110, 3617–3627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-022-07774-z (2022).

Luo, J. & Fan, E. Dbar dressing method for the coupled Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation. Appl. Math. Lett. 110, 106589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aml.2021.107297 (2020).

Zhu, J. & Chen, Y. High-order soliton matrix for the third-order flow equation of the Gerdjikov-Ivanov hierarchy through the Riemann-Hilbert method. Acta Math. Appl. Sin.-Engl. Ser. 40, 358–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10255-024-1109-4 (2024).

Zou, Z. & Guo, R. The Riemann-Hilbert approach for the higher-order Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation, soliton interactions and position shift. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 124, 107316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnsns.2023.107316 (2023).

Liu, J., Dong, H., Fang, Y. & Zhang, Y. The Riemann-Hilbert approach for the higher-order Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation, soliton interactions and position shift. Fract. Fract. 8, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract8030177 (2024).

Guo, L., Zhang, Y., Xu, S., Wu, Z. & He, J. The higher order rogue wave solutions of the Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation. Phys. Scr. 89, 035501. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-8949/89/03/035501 (2014).

Kodama, Y. Optical solitons in a monomode fiber. J. Stat. Phys. 35, 597–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01008354 (1985).

Pinar, A., Muslum, O., Aydin, S., Mustafa, B. & Sebahat, E. Optical solitons in a monomode fiber. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 38, 2450122. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217984924501227 (2024).

Monika, N., Shubham, K. & Sachin, K. Optical solitons in a monomode fiber. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 38, 2450087. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217984924500878 (2024).

Aydemir, T. New exact optical soliton solutions of the derivative nonlinear Schrödinger equation family. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56, 1018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-024-06822-9 (2024).

Mjolhus, E. On the modulational instability of hydromagnetic waves parallel to the magnetic field. J. Plasma Phys. 16, 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022377800020249 (1976).

Han, M., Garlow, J., Du, K., Cheong, S. & Zhu, Y. Chirality reversal of magnetic solitons in chiral \(cr_\frac{1}{3}tas_2\). Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 022405. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0163385 (2023).

Rehman, H. et al. Dynamical behavior of perturbed Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation through different techniques. Bound. Value Probl. 2023, 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-023-01792-5 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and H.D.; Methodology, J.H.; Formal analysis, H.D.; Writing—Original draft preparation, J.H.; Writing—Review and Editing, H.D. and N.Z.; Funding acquisition, H.D. and N.Z. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, J., Dong, H. & Zhang, N. Solving the coupled Gerdjikov–Ivanov equation via Riemann–Hilbert approach on the half line. Sci Rep 15, 30735 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15735-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15735-w