Abstract

Fatty acids (FAs) are the building block of fats or lipids and the key indicator for rancidity during grain storage. The pearl millet grains were subjected to lactobacillus (LAB) fermentation and changes in their fatty acid profile with respect to different storage conditions were analysed. This study scrutinized the effect of storage period and temperature (5, 25, and 45 °C) on the fatty acid profile of raw and fermented pearl millet grains stored for 120 days through the FA analysis. A total of 23 FA compounds were identified in raw and fermented grains during storage. The predominant FAs identified in both the control and fermented pearl millet grains are linoleic, oleic, palmitic, alpha-linolenic, and stearic acids. Multivariate data analysis shows that the oPLS-DA and sPLS-DA could distinctly classify the fatty acid data as compared to PLS-DA with respect to various storage conditions. A high value of the variable importance in projection score (VIP > 1) indicates a significant contribution of the FAs to cluster separation. The idea of the FA analysis at a particular time period will be helpful for the endorsement of applicable remedial measures so as to minimize grain quality loss and recommend a use-by-date.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) is a staple food of the majority of the poor and small landholders in Africa and Asia, as it is endowed with energy, carbohydrate, protein, fat, vitamins, phenolic compounds, and minerals. Pearl millet is high in fat content (5–7 g/100 g) with better fat digestibility than other grains1. Pearl millet lipids are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) such as linoleic (ω-6) and α-linolenic (ω-3) acids. They are essential fatty acids (FAs), since humans cannot produce them due to the lack of desaturase enzymes. PUFAs are the principal lipid groups in pearl millet and contribute 50% of the total FAs2. Additionally, cereal lipids are the major source of unsaturated fatty acids (USFAs), which are known to offer several health benefits, such as reducing cardiovascular risk, improving cognitive functions, and lowering glycemic index3.

In spite of having nutritional punch, the full potential of pearl millet is restrained due to its low shelf life, owing to the generation of rancidity and odor during storage that hinders wider consumer acceptability4. While most millets have a tough exterior and a good shelf life in the unhusked form, pearl millet grains, on the other hand, turn rancid even in the whole form. The shelf life of whole pearl millet grain in fresh state is 3–4 months, whereas the flour has a shelf life of 7–8 days4. High-fat content coupled with high lipase activity leads to the hydrolysis of pearl millet fat into FAs, leading to rancidity evolution during storage5. Several processing methods, such as addition of antioxidants, dry heating, parboiling, microwave and IR heating treatment, malting, and fermentation, have been used to enhance the shelf life of pearl millet flours with regards to rancidity6,7,8,9.

The deterioration in pearl millet flavor and odor during storage is typically due to lipid oxidation, which primarily affects the unsaturated fatty acids, such as linoleic acid (ω-6) and linolenic acid (ω-3), producing off-flavors and reducing nutritional value4. Lipid oxidation initially converts a non-reactive fatty acid into reactive lipid peroxide, via an intermediate lipid radical, and is governed by either auto-oxidation or enzymatic oxidation. Further, the lipid peroxide with another lipid, producing a lipid-hydroperoxide and a lipid radical10. Finally, the decomposition of an alkoxyl radical produced via hydroperoxide breakdown, or the hydrolysis of the hydroperoxide via the enzyme hydro-peroxidelyase, eventually generates carbonyl compounds, such as aldehydes and ketones during storage11.

Fermentation is an age-old practice for cereals and legumes to enhance the nutritive value and shelf life12. In the metabolic process of fermentation, organic materials are entirely broken down by enzymes13. Nevertheless, during lactobacillus fermentation, the beneficial microbes convert complex molecules into smaller ones, easing digestion14. The process of fermentation results changes in starch granules by the action of enzymes and organic acids, affecting the gelatinization, and textural characteristics15,16. These actions bring about changes in the chain of amylopectin due to the variation in ratio of amylose to amylopectin and amorphous-region hydrolysis17. It has been observed that fermentation improves the amino acid profile and protein efficiency ratio, enhances the mineral bioavailability, vitamin B, and FAs profile of sorghum and millets, reduces anti-nutritional factors, such as tannin, phytic acid, trypsin inhibitors, and lipase activity12,18. Thus, it can have a better taste profile and acceptability by consumers.

The practice of airtight storage is not new; this technique has been used since ancient times19. Airtight storage structures are an effective method for preserving the quality and shelf life of grains by minimizing exposure to oxygen, moisture, and pests20. By limiting oxygen availability, airtight storage slows the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids, such as oleic and linolenic acids, which are prone to spoilage. Additionally, it inhibits the activity of lipase enzymes that break down triglycerides into free fatty acids, reducing the risk of rancidity. Proper airtight storage also prevents insect infestations and fungal growth, provided the grains are dried to a safe moisture level before sealing21,22. This method is particularly beneficial for high-fat grains like pearl millet, helping to maintain their nutritional value and sensory qualities over extended periods.

Currently, there is limited research work and literature available on the fatty acid profile of cereal grains during different storage conditions. At the same time, no research work is available to showcase the effect of submerged lactobacillus fermentation on the fatty acid profiling of pearl millet grains under different storage temperatures and periods. Hence, in the present work, the fatty acid characteristics of raw and fermented pearl millet grains were evaluated concerning various storage durations and temperatures.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Chemicals used in this study were analytical grade. They were procured from Sigma Aldrich Co and utilized without any further purification.

Sample preparation

The pearl millet grain (c.v. MPMH17) sourced from the local market of Bhopal (Dist.), Madhya Pradesh, India, harvested during the Kharif season (October 2021) was used for the analysis. The whole pearl millet grains were cleaned and subjected to the selected treatment process as per the designed experimental conditions. For the process of fermentation, a mixed LAB culture prepared from bovine milk using back slopping method, was grown on tofu whey-based media (1:2) for 16 h18. The culture was then utilized to inoculate the whole cleaned pearl millet grains, in a tofu whey-based media under submerged conditions in an incubator (JEQ-4(C), Micro Teknik, India) for 24 h at 37 °C. The grain samples were taken out from media after 24 h and dried initially through air ventilation followed by drying at 50 ± 5 °C in a laboratory hot air oven (Jyoti, JSI-520, India) for 20 h, till they attained a safe storage moisture level of 11–12% w.b.

Storage of whole grain samples

The raw and fermented whole grains as described above (400 g, 11.3% w.b.) were stored in individual airtight glass bottles having a capacity of 0.5 L. Three BOD Refrigerated Incubators (JEQ-4(C), Micro Teknik) were used to store the bottles for a period of 120 days under dark conditions. By considering the diversity of the temperature distribution in India, the grains were stored at different temperatures (5 ± 1, 25 ± 1, and 45 ± 2 ℃). Since the grains were stored in an airtight glass container, the relative humidity was not considered in this study.

Extraction of lipids

The total lipid content of flour was determined by Soxhlet extraction according to AOAC23 method. About 100 g of raw and fermented grains were grounded into fine powder. Samples with three replicates of 3 g each were used for the extraction of lipids in a Soxhlet apparatus (Sox 8, SOXTRON, Tulin, India) by using petroleum ether (Solid: liquid; 1:30) as a solvent for 6 h. The experimental studies were replicated for three times for all the analysis. The raw and fermented pearl millet grains were grounded into fine flour using the ICAR-CIAE multi-purpose grain mill and sieved through mesh 60 to get uniform particle size prior to the analysis. The fatty acid (FA) analysis of raw and fermented pearl millet grains was accomplished at 0 (T0), 60 (T60), and 120 (T120) days of storage time24.

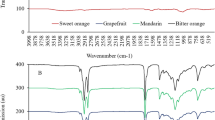

Fatty acid profiling

The profiling of FA was carried out through gas chromatography-flame ionization detection (GC-FID) with AOC-20i + s auto-sampler and interfaced with a Mass Spectrometer (QP 2010 Ultra, Shimadzu, Japan) system2. The samples were derivatized to fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) according to AOAC25 method prior to the analysis. An aliquot of 100 µL of extracted lipids for each sample was converted to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) using a methanolic sodium hydroxide solution. Heptane (2 mL) was added to 100 µL of the sample in a test tube and vortexed. Then, 0.2 mL of 0.5 M methanolic sodium hydroxide solution was added to it. The solution was shaken vigorously. After being allowed to stand, two phases had separated in the test tube, and 2 µL of the upper portion was injected into the fatty acid column for further analysis. The components of fatty acids were examined using GC with a column (ELITE 2560) of 100 m in length, 0.25 mm internal diameter (i.d.), and 0.2 μm film thickness. Helium was used as the carrier gas. The temperature of the oven was programmed after 2 min to rise from 140 °C to a final temperature of 240 °C at 3 °C /min for 15 min and then held at 240 °C for the rest of the running period (33 min). The entire program duration was 50 min. The injector temperature was set at 225 °C and the detector temperature was maintained at 250 °C. To find out the peaks of FAs, a standard of C4 to C24 FA methyl ester mixture was used (Supelco, USA) (Table S1). All the FAs were identified with respect to the retention times that of pure standards. Each FA was expressed as a percentage of the peak area by referring to the internal standards.

Multivariate statistical analysis

The data were analyzed statistically by ANOVA using SPSS (version 26.0) software and Tukey’s test (P < 0.05) was performed to determine the significant differences among the mean values. The acquired lipid profile data were analyzed with principal component analysis (PCA), sparse partial least squares discriminant analysis (sPLS-DA), orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (oPLS-DA), and the correlation analyses were executed using the web-based tool MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca) to study the clusters and correlation among the raw and fermented samples. The VIP score of a variable was calculated as a weighted sum of the squared correlations between the PLS-DA components and that of the original variables. The quantitative estimation of the discriminatory power of each individual feature was scrutinized based on variable importance score (VIP) > 1 in the PLS-DA model and the comparisons were performed via an average linkage method based on Euclidean distance.

The clustered heat map is a graphical representation of data with cluster trees appended to its margins. It compacts large amounts of data matrix into a small space to bring out coherent patterns in the data. The foremost accrual of FA compounds shows a thick brown color, whereas it gradually reduces from dark blue to light blue as the relative area percentage shifts to a minimum. These procedures were analyzed without further filtering or normalization of the obtained data using MetaboAnalyst, and a 95% confidence region was selected for representation.

Results and discussions

Total lipids and fatty acids in fermented and non-fermented grains during storage

The crude fat content of raw millet samples reduced from 5.18 to 4.34% during fermentation, showing a significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) among the treatments (Table S2). The results are also in agreement with the findings of Sade (2009)26 who had perceived that the fat content of pearl millet reduced from 5.7 to 2.4% during fermentation for 72 h. The low-fat content attributed to the fermentation increases the shelf life of pearl millet grains by reducing the chances of rancidity2.

The percentage of various FA fractions of raw and fermented pearl millet grains under different storage conditions is summarized in Table 1. The chromatogram of raw and fermented pearl millet grains under different storage conditions is presented in Fig. S1 (As supplementary file). A total of 23 FA compounds were identified in the raw and fermented grains during storage. A significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) was observed in all the fractions of FAs under various storage conditions. Pearl millet grains contain a high level of unsaturation (including monounsaturated and PUFAs), which varies from 77.27 to 78.40% among the total FA content with an excellent source of essential FAs (Table 2). The unsaturated to saturated FA ratio for the grains at all storage temperatures varied from 3.40 to 3.57. A value greater than 2.5 for the ratio of unsaturated to saturated FAs is considered a nutrient-rich product2.

According to Table 1, during the commencement of storage days, the lipids from the raw pearl millet were composed mainly of 44.04% linoleic acid (C18:2n6c), 28.9% oleic acid (C18:1n9c), 18.48% palmitic acid (C16:0), 2.8% stearic acid (C18:0), and 2.36% alpha-linolenic acid (C18:3n3), at 5, 25 and 45 °C. Slama et al.2 concluded that the linoleic acid (47.5%) was the major FA and the total unsaturated FAs in pearl millet fraction contribute about 77.2% of the total oil content. Previous studies also verify that linoleic, oleic, and palmitic acids are the major pearl millet FAs, in both free and bound forms27. In our case, fermented pearl millet grain showed predominantly linoleic acid (45.1%) followed by oleic (29.91%), palmitic (18.38%), stearic (0.78%), and alpha-linolenic acid (2.45%). It was observed that the tofu-whey-based microbial fermentation for 16 h caused a significant increase in the linoleic, oleic, and alpha-linolenic acid contents and a significant reduction of palmitic and stearic acid as compared to raw pearl millet grains. These phenomena can be explained by the fact that during fermentation, the lactic acid bacteria utilize the sugars by breaking down the cellular structure. The lipid molecules’ oxidation is inhibited by the reduction of the complex carbohydrates into simple chain components. Besides, due to cellular disruption, the trapped lipid molecules are released, thereby improving the fatty acid content. At the same time, some of the higher chain fatty acids are also broken down into smaller chain compounds, resulting in their depletion, which is reflected in our result.

In the present study, the tofu whey-based lactobacillus fermented grains imparted only a minor variation in the concentration of FAs as compared to the raw grains. Whereas the raw grain displayed a slight increment and decrement in the FA profiling during storage at different conditions. It may be due to the temperature and period of storage adopted for the study impacting the variation in the FA concentration. In the present investigation, the relative fraction of α-linolenic acid (C18:3n3), a PUFA ω-3 FA in raw and fermented grains was less as compared to other PUFAs. Regardless of the very low content of ω-3 FAs, pearl millet grains are suitable for direct use as foodstuff produced from seeds or edible oil and are a rich source of linoleic acid (18:2 ω-6). A diet rich in MUFAs (oleic acid, palmitoleic acid, etc.) can be a choice for a low-fat diet (LFD), which has the potential for reducing the blood cholesterol level, heart diseases, helps to develop, and maintain the body cells2. As compared to MUFAs, the presence of PUFAs in our diet helps to reduce cardiovascular diseases and bad cholesterol levels and thereby reduces the liability of oxidation of low-density lipoprotein, nerve function, muscle strength, blood clotting, and enhances the high-density lipoprotein fluidity level, etc28.

It was observed that > 45% of the FA is contributed by linoleic acid (polyunsaturated ω-6 FA), followed by oleic acid (> 29%), monounsaturated ω-9 FA, followed by palmitic acid (> 18%), a saturated FA in both raw and fermented grains (Table 1). Atmospheric oxygen oxidizes oleic acid, a monounsaturated FA, at the level of the double bond to form peroxides, which are vulnerable to oxidation, and create the breakage of double bond and carbon chain into short-chain monocarboxylic and dicarboxylic acids and aldehydes29which are responsible for the development of foul odor and taste, during storage. The pearl millet germ consists of many triglycerides, composed of unsaturated FAs. Lipase and lipoxygenase (LOX) are site-specific enzymes that cleave the 1, 3-site of triglycerides liberating free fatty acids (FFA), and the UFAs undergo oxidation leading to flavor instability. It increases acidity and imparts soapy off-flavor to the grains during storage9,30.

It may be noted that in our case, the fermented and normal pearl millet samples have 4 to 5% fat content. Oxidation of lipids leads to the generation of carboxylic groups, for example, aldehydes and ketones. Hydrolysis of lipids by lipase generates FAs and glycerol, which are the major changes during storage. The starch lipids are less likely to oxidize than unsaturated FAs as they maintain a steady amount of FA content during storage. Non-starch lipids involved during hydrolysis and oxidation of lipids contribute to the rancidity of the grains31. In our study, we observed that the absolute content of oleic and linoleic acid increased during storage, giving an indication of the rancidity of pearl millet grains.

Effect of fermentation on lipid profile

The process of fermentation had a significant effect on the fatty acid profiling of pearl millet grains. Changes in FAs of the total lipids, non-polar, and polar lipid fractions were perceived during the fermentation process. The abundant FA in the polar lipid fraction was linoleic acid (C18:2n6c), and the major portion of the non-polar fraction accounted for oleic acid (C18:1n9c). In subsequent stages of fermentation, the non-polar fractions of FA contents were increased. It may be due to the formation of oleic acid, vaccenic, and di-hydrosterculic acids by the lactobacillus species during fermentation in the tofu whey media32. The fermentation results depicted that the lactobacilli do incorporate exogenous free PUFAs into their cell lipids, as they grow rapidly in the tofu whey media, which is enriched with sugars, disaccharides and oligo saccharides, protein factions and a small amount of fat fractions33. This might have affected the proportions of PUFAs with 20 to 22 carbons and 18 carbons with conjugated double bonds, as well as the degree of FA unsaturation and cyclization observed for the growth medium of lactobacilli34. It was also observed that the fermentation process improved the unsaturated to saturated FA ratio from 3.43 to 3.57 as compared to the raw sample (3.41 to 3.52). It may be due to the enhancement of unsaturated FAs during the fermentation with the degradation of starch and sugars by the enzymes present in the grain and fermentation media6.

In our case, in comparison with the raw grains, the fermented pearl millet grains showed a slightly higher FA content at the end of storage (120 days). The slight increment in the FA content for the fermented sample can be linked to the enhanced activity of lipolytic enzymes that can generate more FAs during the fermentation and the extensive breakdown of large molecules of fat globules into simple FA compounds, by the action of beneficial microbes35. Given that the concentration of linoleic acid (C18:2n6c), oleic acid (C18:1n9c), and α-linolenic acid (C18:3n3) during the storage were high in raw grains, one explanation might be that the raw grains are more likely to go rancid at a faster rate than fermented grains. The lipoxygenase present in the pearl millet grain catalyzes the oxidation of these unsaturated FAs and esters into hydroperoxides. Further, it was converted into secondary oxidation products such as aldehydes and ketones, leading to the development of bitterness or rancidity in the grains4. During fermentation lactobacillus utilizes the carbohydrates as their energy source and encases the lipids. Therefore, it prevents the oxidation of starch-lipids. Besides, the release of antioxidants from the cell also binds the active sites of lipids, preventing them from deterioration. A parallel study conducted to determine the free fatty acids, peroxide value, acid value and lipase activity have seen a surge in those parameters of raw and fermented grains, during 120 days of storage from 0.85 to 6.23%, 5 to 88.33 mEq. kg− 1, 1.2 to 8.84 mg NaOH 100 g− 1, and 4.29 to 23.27 mg KOH g− 1, respectively we stored under the same temperature regime (5–45 °C), which validates our current observation in the FA profile36.

In general, lipids are broken down through the action of amylolytic enzymes present in pearl millet grains and produced by LAB during fermentation37. Glucose is the end-product of starch degradation and is utilized immediately; the simple carbohydrates are metabolized directly and are primarily organic acid precursors. Lactic acid bacteria exhibit moderate proteolytic activity in fermented grains38. During the metabolism of lipids, the lipoxygenases oxidize the PUFAs like linoleic acid into hydroxyl peroxy acids39. Further, the hydroperoxy linoleic acid is alternatively reduced to hydroxy-linoleic acid with concomitant oxidation of grain constituents. The formation of hydroxy FAs during the growth of LAB culture significantly extended the shelf life of fermented grains as compared to the raw grains40. The stable composition of FAs in saturated (stearic and palmitic) and changes in the unsaturated FAs like oleic and linoleic acid indicate that the non-starch lipids are more prone to lipid oxidation is more prone as compared to the starch lipids41.

Effect of temperature and storage period on fatty acid profile during storage

Temperature and time are the most important environmental factors that affect the storage of pearl millet grains. It majorly affects the composition and integrity of the cell and wall structure membrane, including variations in the FA profile of cellular lipids. Temperature regulation of the cellular FA content is regarded to occur at the level of FA biosynthesis as well as after the transacylation of acids to phospholipids42. In the present study, the grain stored at 25 and 45 °C showed a more relative percentage area of linoleic acid (18:2 ω-6) as compared to 5 °C (Table 1). It may be because of the higher temperature on the unsaturation percentage of FAs. It has been also reported that during FA biosynthesis, environmental temperature affects the degree of FA unsaturation, chain length, and branching in the methyl end43. On the other hand, the concentration of oleic, palmitic, and stearic acids increased slightly with temperature and duration as compared to the initial stage of storage or low temperature (5 °C) in raw and fermented grains.

The cellular FA content usually varies with temperature, and the accumulation of lipids may also be induced by lowering or increasing the temperature. It can also be noted that the raw grain stored on the initial day lacks the presence of palmitoleic acid (C16:1) and is generated at the end of the storage period at a temperature of 25 and 45 °C. It may be due to the conversion of palmitic acid to palmitoleic acid by an oxygen-dependent desaturase, which may be possible at higher storage temperatures43. The total percentage of unsaturated FAs in raw grains (77.5%) was more initially, and it was reduced slightly at storage temperature of 45 °C (77.41%); whereas a similar trend was observed for fermented grains also. It may be because of unsaturated FAs are highly susceptible to thermo-oxidation during high temperatures due to the presence of pibonds with high reactivity24 and this decrease was accompanied by an increase in linoleic acid and oleic acid during the period of storage. On the subsequent days of storage, it was observed that the percentage area of unsaturated FA was more compared to saturated one. It is known that unsaturated FAs are formed from saturated FAs with the help of enzymes desaturases and the activity of all enzymes, as protein molecules, depends on temperature44.

Classification and discrimination of fatty acid profile of millet grains

To perform the classification of the pearl millet grains with respect to different storage temperatures, different supervised and unsupervised techniques like PCA, PLS-DA, sPLS-DA, and oPLS-DA were used. The classification of FAs through PCA with respect to different storage conditions was shown in Fig. 1(a) and have revealed around 73.1% of the total variance of the data on the score plot. The biplot of PCA and PLS-DA analysis of fatty acid profile obtained from the raw and fermented grains is depicted in Fig. S2 (As supplementary file). The cross-overlapping of clusters was observed at 25 and 45 °C on the 60th and 120th day of raw grains with the clusters of fermented grains on the score plot. The fermented FA clusters at 45 °C on the 120th day of storage are placed on the opposite side of raw and fermented pearl millet grains stored on the 0th day at 5 °C. It implies the significant changes in the lipid profile of pearl millet grains during storage.

The classification of the fatty acid profile has further been extended based on the discriminating features of the two samples through PLS-DA (Fig. 1b). The discriminant components explained about 58.2% variance of the fatty acid data on the score plot. The PLS-DA model adopted for the analysis best fits the fatty acid data with an R2 value of 93.72% and Q2 value of 50.0%. There was an overlapping of clusters among the raw and fermented grains, especially after the 60th day of the storage period, which might be due to the similar type of discriminant features of the FAs obtained from the samples during storage. The relative contribution of FAs to the variance among raw and fermented grain samples was explained by the VIP score plot (Fig. 2). Based on the VIP score cut-off of around 1.0, the maximum contributing FAs for discrimination features based classification includes Stearic, Erucic, and Linoleic acids, Oleic, cis-11-Eicosenoic, and Palmitic acids. It was also observed that the Stearic acid appeared to contribute to the separation with the highest VIP score (2.90) and the total relative concentration in raw grain (19.36%) was more as compared to fermented grains (17.25%). Followed by erucic acid (MUFA ω-9 FAs), linoleic, and oleic acid also have a good VIP score among the stored pearl millet grains indicating the presence of unsaturated FAs, and oxidation of these compounds leads to the rancidity of stored grains. The VIP scores can help to identify which fatty acids contribute most to changes in lipid profile due to oxidation or rancidity. High VIP scores for linoleic and oleic acids directly align with their oxidation susceptibility, reinforcing their role as key markers in monitoring lipid degradation and rancidity in stored pearl millet45. Apart from the discrimination of raw grains FAs from the fermented ones, the VIP plot gives an idea about the extent of spoilage through these rancidity biomarkers.

The clusters formed for the separation of raw and fermented samples during PCA and PLS-DA showed a complete overlapping among the data set at all selected storage conditions displaying a lack of categorization based on the difference in lipid characteristics of stored grains. Hence, for better separation and interpretation of the same fatty acid data based on the discriminant features has been carried out using oPLS-DA and sPLS-DA analysis. The corresponding oPLS-DA (Fig. 3a) and sPLS-DA (Fig. 3b) score plots show a clear separation, quite pronounced in sPLS-DA results. The score plot obtained after oPLS-DA represents the 50.4% variance of the data. The orthogonal T score 1 and 2 contribute 31.3% and 19.1% of the total variance, respectively. It was observed that the score plot of oPLS-DA shows a distinct separation among the clusters of raw and fermented pearl millet samples based on their FA composition with respect to the storage conditions. In comparison with the previous classifying methods such as PCA and PLS-DA, the orthogonal plot showed a positive correlation among the groups of FAs except for the raw and fermented grains at 45 °C on the initial day of storage.

The sPLS-DA score plot constituted 47.2% of the total variance of the data. The raw grains on the initial day and stored on the 120th day at 45 °C found on the opposite sides of the score plot indicated the difference in FA groups from the commencement of the storage to the end period. This difference might be favored by the oxidation of lipids, which subsequently turned into the formation of hydroperoxides. The change in FA composition at the end of storage might also be due to the presence of secondary oxidation products such as ketones and aldehydes46. On a similar note, it showed the influence of temperature and storage period on the FA concentration. It might be due to the elongation of FA compounds during the period of storage. The superior data fitting ability with the computational efficiency of the results via valuable graphical outcomes of the sPLS-DA method might be a reason for the better distinction of the data47. Hence, this method is proved to be best among others to clearly separate and classify the fatty acid data obtained during storage. The oPLS-DA and sPLS-DA outperformed the PCA and PLS-DA may be due to the better separation, robustness, and biological relevance in complex datasets, especially in omics or lipidomics studies where dimensionality is high and variable selection is crucial.

Classification of lipids using clustered heat map analysis

Figure 4 represents the clustered heatmap of the fatty acid profile of raw and fermented pearl millet grains stored under different storage conditions. The heat map confirmed the presence of gamma-linolenic acid (C18:3n6), butyric acid (C4:0), and elaidic acid (C18:1n9t) as dominant FAs in raw pearl millet grains on the 120th day of storage at 45 °C. Whereas, the fermented grains at a similar storage condition as that of raw grains displayed the accumulation of cis-11-eicosenoic acid (C20:1) and cis-10-heptadecanoic acid (C17:1), as dominant FAs. The dominance of gamma-linolenic acid (0.02%) at 45 °C on the 120th day of storage indicated the signs of rancidity in raw grains. It may be due to the number of double bonds in gamma-linolenic acid (ω-6) being more than those in linoleic acid (18:2, ω-6) and oleic acid (18:1, ω-9), which can be more readily oxidized to ketone or aldehyde causing rancidity during storage48.

Previous research showed that the higher number of double bonds in the FAs increased their vulnerability to oxidation due to the addition of more methylene-interrupted carbon reaction sites49. On the 60th day of storage at ambient conditions (25 °C), exhibited the presence of Tricosanoic acid (C23:0) and cis-11,14,17-Eicosatrienoic acid (C20:3n3), as the dominant FAs. The incidence of Tricosanoic acid as the dominant FA was also observed at 45 °C on the 60th day in raw grains and on the 120th day in fermented grains. Tricosanoic acid is a long chain of saturated FA, in which one of the methyl groups has been oxidized to the corresponding carboxylic acid50. The dominance of Nervonic acid (C24:1) was reported at 5 °C on the 60th day of storage in raw grains and this compound was absent in other storage periods and temperatures. It is a ω-9 monounsaturated long-chain FA present in minute quantities in grains51. Changes in dark blue to very light brownish tile in the heat map analysis implied the presence of α-linolenic acid (short chain ω-3 essential FA) at 5 °C stored raw grains on 60th day.

The heat map showed a large amount of occurrence of linoleic acid (C18:2n6c) and oleic acid (C18:1n9c) as dominant FAs in raw and fermented grains, irrespective of the storage conditions. It might be due to the fact that the major portion of the cereal lipids constituted of unsaturated FAs often PUFAs. The higher storage period and longer duration changed the concentration of these acids in the raw and fermented pearl millet grains. During the initial days of storage, the Lignoceric (C24:0), Erucic (C22:1n9), and Behenic acids (C22:0) were found dominant in raw grains than in fermented grains. On the other hand, in our study, Myristoleic acid (C14:1), a monounsaturated (ω-5) FA was present in the raw pearl millet grain during the initial period of storage and was absent in the succeeding period of study. It may be due to the uncommon nature of the compound in cereal grains.

Conclusion

The fatty acid profile of raw and fermented pearl millet grains is significantly affected by the temperature and period of storage. The major FA compounds identified from the raw and fermented pearl millet oil are Linoleic acid (C18:2n6c), Oleic acid (C18:1n9c), Palmitic acid (C16:0), Stearic acid (C18:0), and alpha-linolenic acid (C18:3n3). The higher storage temperature and longer duration change the concentration of these acids among the raw and fermented pearl millet grains. The oPLS-DA and sPLS-DA could distinctly classify the fatty acid data as compared to PLS-DA with respect to various storage conditions. FAs with high VIP scores are more important in cluster separation, while small VIP scores contribute less to the data. A higher VIP score among the stored pearl millet grains indicates the presence of unsaturated FAs like linoleic, oleic, and Erucic acids, which are the biomarker for rancidity. The idea of FA analysis at a particular period will be helpful for the endorsement of applicable remedial measures at the right time to avoid the rancidity of grains or recommending a use by date for pearl millet. At the same time, the utilization of pearl millet fractions in foods is strongly recommended as it is a good source of FAs. This study helps in developing fermentation-based food products/ functional foods from pearl millet grains with improved fatty acid composition, enhancing nutritional value. Also, it can provide insights into the optimal storage methods to maintain the nutritional profile of pearl millet, especially in hot and humid environments. In general, this work enables authentication of fermented and non-fermented pearl millet through fatty acid markers, preventing food adulteration and ensuring product integrity thereby improving the quality, storage, and health benefits of pearl millet products.

Data availability

The corresponding author can provide the datasets created and analyzed during the current investigation upon reasonable request.

References

Nibhoria, A., Kumar, M., Arya, R. K. & Siroha, A. K. Pearl millet for good health and nutrition-An overview. CABI Rev. 19 (1). https://doi.org/10.1079/cabireviews.2024.004 (2024).

Slama, A., Cherif, A., Sakouhi, F., Boukhchina, S. & Radhouane, L. Fatty acids, phytochemical composition, and antioxidant potential of Pearl millet oil. J. Consum. Prote Food S. 15 (2), 145–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00003-019-01250-4 (2020).

Bora, P., Ragaee, S. & Marcone, M. Characterization of several types of millets as functional food ingredients. Int. J. Food Sc Nutr. 70 (6), 714–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2019.1570086 (2019).

Goswami, S., Kumar, R. R. & Praveen, S. Hydrolytic and Oxidative Decay of Lipids: Biochemical Markers for Rancidity Measurement in Pearl Millet Flour. In Omics meet Plant Biochemistry: Applications in nutritional enhancement with one health perspective. 221 (2019).

Kumar, R. R. et al. Lipase-The fascinating dynamics of enzymes in seed storage and germination-A real challenge to Pearl millet. Food Chem. 361, 130031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130031 (2021).

Pawase, P. A., Chavan, U. D. & Lande, S. B. Pearl millet processing and its effect on antinational factors: review paper. Int. J. Food Sc Nutr. 4 (6), 10–18 (2019).

Adebiyi, J. A., Obadina, A. O., Adebo, O. A. & Kayitesi, E. Comparison of nutritional quality and sensory acceptability of biscuits obtained from native, fermented, and malted Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) flour. Food Chem. 232, 210–217 (2016).

Sangma, S. J. et al. Hydrothermal treatment: A critical research on improving milling efficiency using the parboiling process for Pearl millet. Int. J. Plant. Sci. 36 (6), 140–147 (2024).

Sruthi, N. U. & Rao, P. S. Effect of processing on storage stability of millet flour: a review. Trends Food Sci. 112, 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.03.043 (2021).

Urban-Alandete, L. Lipid degradation during grain storage: markers, mechanisms, and shelf-life extension treatments (Doctoral dissertation, School of Agriculture and Food Science, University of Queensland). (2018).

Gomes, M. H. G. & Kurozawa, L. E. Improvement of the functional and antioxidant properties of rice protein by enzymatic hydrolysis for the microencapsulation of linseed oil. J. Food Eng. 267, 109761 (2020).

Nkhata, S. G., Ayua, E., Kamau, E. H. & Shingiro, J. B. Fermentation and germination improve nutritional value of cereals and legumes through activation of endogenous enzymes. Food Sci. Nutr. 6 (8), 2446–2458. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.846 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. Untargeted mass spectrometry-based metabolomics approach unveils biochemical changes in compound probiotic fermented milk during fermentation. Npj Sci. Food. 7 (1), 21 (2023).

Balcázar-Zumaeta, C. R., Castro-Alayo, E. M., Cayo-Colca, I. S. & Idrogo-Vásquez, G. Muñoz-Astecker, L. D. Metabolomics during the spontaneous fermentation in cocoa (Theobroma Cacao L.): an exploraty review. Food Res. Int. 163, 112190 (2023).

Adebo, J. A., Chinma, C. E., Omoyajowo, A. O. & Njobeh, P. B. Metabolomics and its application in fermented foods referencing. In Indigenous Fermented Foods for the Tropics. 361–376 (2023).

Park, J., Sung, J. M., Choi, Y. S. & Park, J. D. Effect of natural fermentation on milled rice grains: physicochemical and functional properties of rice flour. Food Hydrocoll. 108, 106005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106005 (2020).

Lu, Z. H., Yuan, M. L., Sasaki, T., Li, T., Kohyama, K. & L. T. & Rheological properties of fermented rice flour gel. Cereal Chem. 84 (6), 620–625. https://doi.org/10.1094/CCHEM-84-6-0620 (2007).

Mohapatra, D. et al. Impact of LAB fermentation on the nutrient content, amino acid profile, and estimated glycemic index of sorghum, Pearl millet, and Kodo millet. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed). 16 (2), 18 (2024).

De Lima, C. P. F. Airtight storage: principle and practice. Food preservation by modified atmospheres (ed. Calderon, M. & Barkai Golan, R.) 9–19 (1990).

Okparavero, N. F. et al. Effective storage structures for preservation of stored grains in nigeria: A review. Ceylon J. Sci 53(1) (2024).

Pasqualone, A. Addressing shortages with storage: from old grain pits to new solutions for underground storage systems. Agriculture 15 (3), 289 (2025).

Binga, E., Mashavakure, N., Makaranga, J. & Musundire, R. Pit silos require hermeticity to serve as an alternative low-cost storage facility for maize grain by smallholder farmers. J. Technol. Sci. 1(1), (2022).

AOAC. Official methods of analysis of the AOAC, 15th ed. Methods 932.06, 925.09, 985.29, 923.03. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Arlington, VA, USA. (1990).

Wang, L., Wang, L., Qiu, J. & Li, Z. Effects of superheated steam processing on common buckwheat grains: lipase inactivation and its association with lipidomics profile during storage. J. Cereal Sci. 95, 103057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2020.103057 (2020).

AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the AOAC 969.33. Fatty acids in oils and fats. 17th Ed. Arlington, Virginia, USA. (2005).

Sade, F. O. & Proximate anti-nutritional factors, and functional properties of processed Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum). J. Food Technol. 7 (3), 92–97 (2009).

Pei, J. et al. A review of the potential consequences of Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) for diabetes mellitus and other biomedical applications. Nutr 14 (14), 2932. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142932 (2022).

da Almeida, R. Bioactive compounds from brewer’s spent grain: phenolic compounds, fatty acids, and in vitro antioxidant capacity. Acta Sci. Technol. 39 (3), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.4025/actascitechnol.v39i3.28435 (2017).

Concepcion, J. C. T. et al. Quality evaluation, fatty acid analysis, and untargeted profiling of volatiles in Cambodian rice. Food Chem. 240, 1014–1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.019 (2018).

Aher, R. R. et al. Loss-of-function of triacylglycerol lipases are associated with low flour rancidity in Pearl millet [Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.]. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 962667 (2022).

Zhang, D. et al. Lipidomics reveals the changes in non-starch and starch lipids of rice (Oryza sativa L.) during storage. J. Food Compost Anal. 105, 104205 (2022).

Murga, M. F., Cabrera, G. M., De Valdez, G. F., Disalvo, A. & Seldes, A. M. Influence of growth temperature on cryotolerance and lipid composition of Lactobacillus acidophilus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88 (2), 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00967.x (2000).

Besediuk, V., Yatskov, M., Korchyk, N., Kucherova, A. & Maletskyi, Z. Whey-From waste to a valuable resource. J Agric. Food Res 101280 (2024).

Kankaanpaa, P., Yang, B., Kallio, H., Isolauri, E. & Salminen, S. Effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids in growth medium on lipid composition and on physicochemical surface properties of lactobacilli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 (1), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.1.129-136.2004 (2004).

Adebo, J. A. et al. Fermentation of cereals and legumes: impact on nutritional constituents and nutrient bioavailability. Ferment 8 (2), 63 (2022).

Selvan, S. S. et al. Development of machine Learning-based Shelf-Life prediction models for Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) grains using oxidation kinetics data. Journal Agricultural Engineering (India). 61 (6), 847–861 (2024).

Igbabul, B., Hiikyaa, O. & Amove, J. Effect of fermentation on the proximate composition and functional properties of Mahogany bean (Afzelia africana) flour. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.12944/CRNFSJ.2.1.01 (2014).

Marko, A., Rakická, M., Mikušová, L., Valík, L. & Šturdík, E. Lactic acid fermentation of cereal substrates in nutritional perspective. Int. J. Res. Chem. Env. 4 (4), 80–92 (2014).

Gänzle, M. G. Enzymatic and bacterial conversions during sourdough fermentation. Food Microbiol. 37, 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2013.04.007 (2014).

Wang, Z. & Wang, L. Impact of sourdough fermentation on nutrient transformations in cereal-based foods: mechanisms, practical applications, and health implications. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 7, 124–132 (2024).

Peng, B. et al. Effects of rice aging on its main nutrients and quality characters. J. Agric. Sci. 11 (17). https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v11n17p44 (2019).

Wang, F., Xiao, X., Ou, H. Y., Gai, Y. & Wang, F. Role and regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in the response of Shewanella piezotolerans WP3 to different temperatures and pressures. J. Bacteriol. 191 (8), 2574–2584. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00498-08 (2009).

Suutari, M. & Laakso, S. Microbial fatty acids and thermal adaptation. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 20 (4), 285–328. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408419409113560 (2008).

Voronkov, A. & Ivanova, T. Significance of lipid fatty acid composition for resistance to winter conditions in asplenium scolopendrium. Biolo 11 (4), 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11040507 (2022).

Yogendra, K. et al. Comparative metabolomics to unravel the biochemical mechanism associated with rancidity in Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (21), 11583 (2024).

Liu, K., Liu, Y. & Chen, F. Effect of storage temperature on lipid oxidation and changes in nutrient contents in peanuts. Food Sci. Nutr. 7 (7), 2280–2290. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1069 (2019).

Lê Cao, K. A., Boitard, S. & Besse, P. Sparse PLS discriminant analysis: biologically relevant feature selection and graphical displays for multiclass problems. BMC Bioinform. 12 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-253 (2011).

Manosroi, A., Ruksiriwanich, W., Abe, M., Manosroi, W. & Manosroi, J. Transfollicular enhancement of gel containing cationic niosomes loaded with unsaturated fatty acids in rice (Oryza sativa) Bran semi-purified fraction. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 81 (2), 303–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.03.014 (2012).

Barden, L. & Decker, E. A. Lipid oxidation in low-moisture food: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 56 (15), 2467–2482. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2013.848833 (2016).

Kyselová, L., Vítová, M. & Řezanka, T. Very long chain fatty acids. Prog Lipid Res. 87, 101180 (2022).

Tu, X. et al. Lipid analysis of three special nervonic acid resources in China. Oil Crop Sci. 5 (4), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocsci.2020.12.004 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The first author wishes to acknowledge the scholarship granted by ICAR-IARI for carrying out Ph.D. research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SSS: PhD scholar conceptualized, carried out the experiment, analyzed data & prepared the manuscript DM: Chairperson, advisory committee, conceptualized, methodology, resources, reviewed and edited the manuscript AK, MKT, AKar: member advisory committee, extended laboratory facilities, reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material. The supplementary material 3 have a correction regarding the order of Table S1 and Table S2. In the Text, first I have mention about the standards of Fatty acids (Table S1) used for the study and the crude fat content data as Table S2. But in the Supplementary Material 3 the first table shown was crude fat content data and second is standard of fatty acids. So I again uploaded the corrected version of the file by interchanging the position. Kindly consider the new file instead of the previous one for further process. Thank you.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Selvan, S.S., Mohapatra, D., Kate, A. et al. Fatty acid profiling for discriminating fermented and non-fermented pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) grains under different storage temperatures. Sci Rep 15, 34210 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15785-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15785-0